Barriers and Facilitators to Healthy Eating for Shift-Work-Registered Nurses in Hong Kong Public Hospitals: An Exploratory Multi-Method Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Settings and Participants

2.3. Data Collection Methods

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Data

2.3.2. Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ)

2.3.3. Three-Day Dietary Record

2.3.4. Photovoice

2.3.5. Semi-Constructed Interview

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

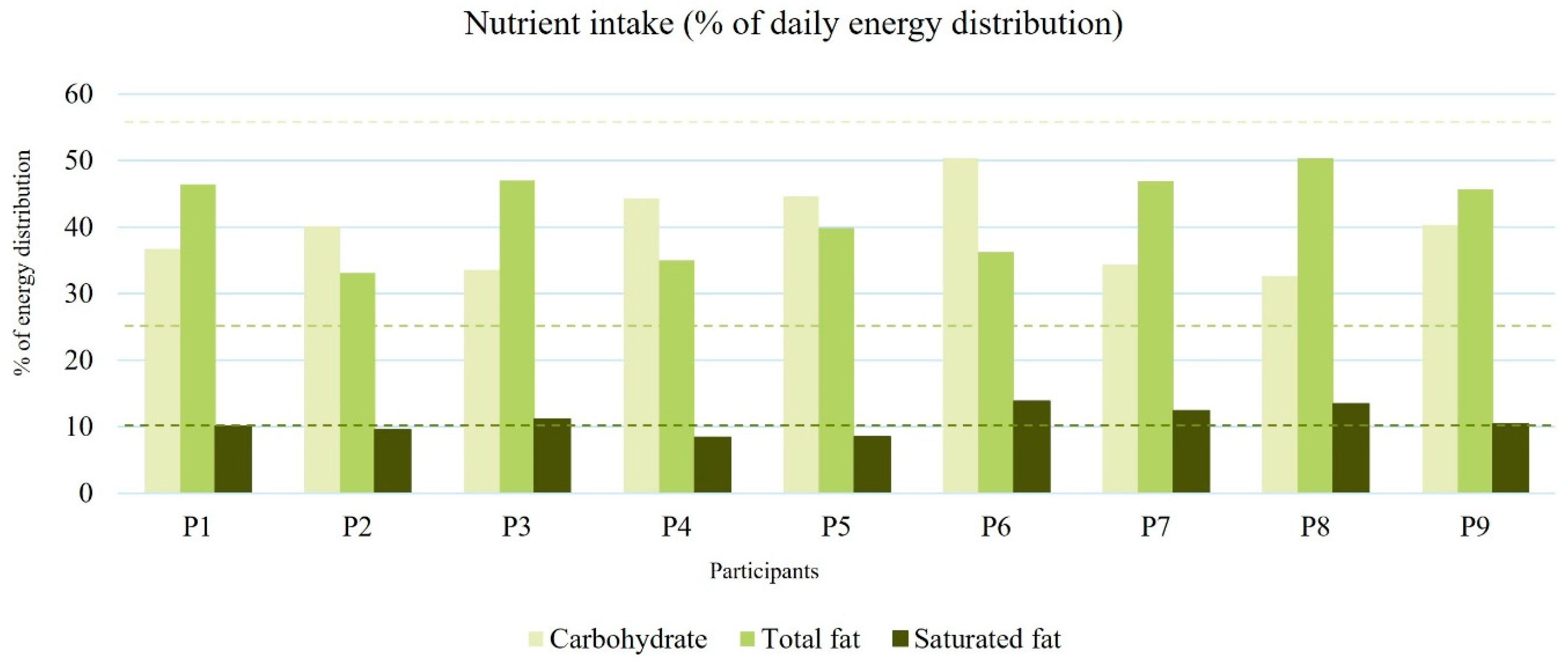

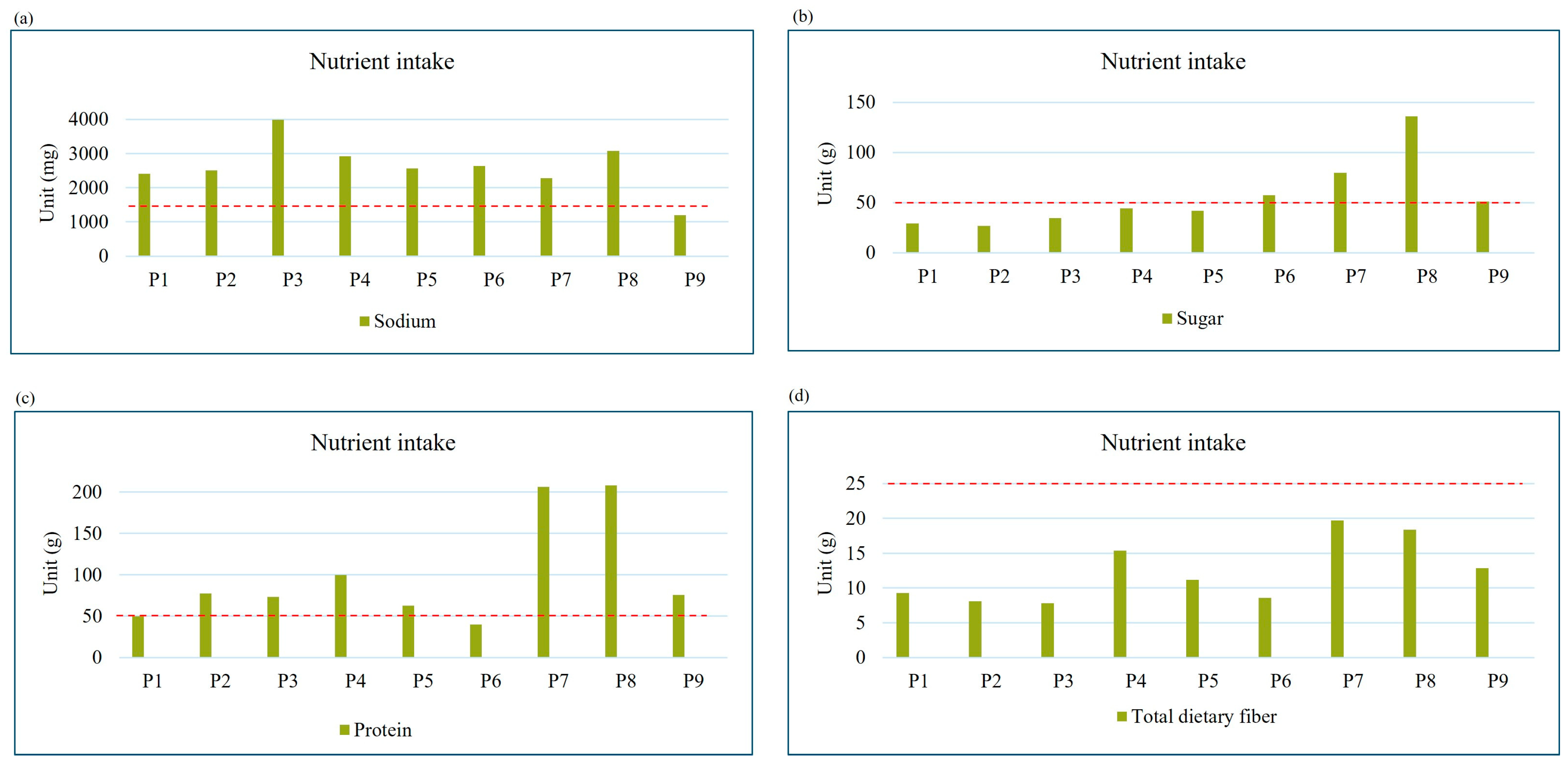

3.2. Prevalence of Excessive or Deficient Dietary Intake

3.3. Barriers and Facilitators to Healthy Eating During Work

3.3.1. Barriers to Healthy Eating

Individual Factors

- Comfort food and emotional eating

“It was a stressed and busy day to me. Why would I still need to eat badly in a worse day? It’s not the time to mention eating healthy, I would rather go for the food I love.”(P5, operating theater, normal BMI)

“I love eating Siu Mai. Especially when it was on promotion, I can eat 20 Siu Mai at once after work! Sometimes I would also drink cola as well, make it a full meal!”(P3, OBS, obese) (Figure S2a)

“I felt so stressed and nervous during work, which made me double the eating portion after work when I needed to be the nurse in-charge.”(P7, medical, overweight)

“That night shift was incredibly busy, and the cases were really complicated…I went to 7–11 and bought the (12 bottles) Coca-Cola. The soda pop and carbonated gas kind of giving me a sense of relief after drinking and belched it out. Also, cola is sweet enough to replenish sugar level and energy. Drinking water could not achieve this effect at all. This (the photo) is only for 4 persons to consume, each of us need to relax in the long night shift…”(P8, ICU, overweight) (Figure S2b)

- b.

- Palatability

“Healthy food are never tasty, Tasty food are never healthy. No one will eat healthy food at all! At least I am one of them.”(P7, medical, overweight)

- c.

- Personal perception, attitudes, and health issues

Social Factors

- Colleagues’ influence/appreciations from patients

“…whatever they (colleagues) ordered, I would just follow and share the food, regardless its nutritional value. Share dishes is happier compared to eating alone…during night shift, we would brought back many night-food with high carbohydrates such as dim-sums, fried food, or other sweet soups as we knew that we had to stay up all night. Therefore, we brought back a lot of food to share.”(P4, pediatric ICU, normal BMI)

“Colleagues would usually bring souvenirs back when they ended their annual leaves. Usually on each Mondays the table will be full of snacks, such as potato chips, chocolate. You cannot escape or avoid it even you just ate one or two bites whenever you enter the pantry to have a rest.”(P1, medical, normal BMI)

“It’s usually 5–6 times a month (patients bringing gifts to the ward) … Once have a time that two patients bringing assorted cakes at the same time, making everyone getting a cake as meals!”(P9, surgical, normal BMI) (Figure S2g)

- b.

- Family influence

“My parents usually off work late, sometimes we did not cook at home and dine out in late night, like 9 or 10 p.m. I often having some snacks to resolve my hunger while waiting them back home. Sometimes I might just bring the left-over when we dine out, which was oily and high salt level.”(P8, ICU, overweight)

Organizational Factors

- Shift work nature

“The rotating shift really kills me with 6 working days and one day off per week. I worked 6 night shifts last month, not to mention the long working hour of 10–12 h per day. The workload is really heavy, I am really ready to submit the resignation form if the situation continues…”(P1, medical, normal BMI)

“A shift usually works at 7 a.m., and lunch at 1:30 p.m. I can only have my so-called full meal at 2 p.m. until I finished my handover. It is very hungry for me and I usually grab any food from the pantry whatever is it, until getting full.”(P6, surgical, normal BMI)

- b.

- Sudden change of work schedule

“There was no use to prepare meals or snacks for the next day, as you will never know if you need to work or not. (The ward manager) giving you an off suddenly, begging you to work tomorrow…we (the colleagues) were all used to it.”(P7, medical, overweight) (Figure S2d)

- c.

- Meal break availability

“The “beep beep” sound from the medical devices scared me. Whenever it was ringing, every nurse would get full attention to the patient and stop doing anything, not to mention finishing the whole meal. By the time I back to the pantry, I did not have the appetite to eat the “leftover” food anymore.”(P4, pediatric ICU, normal BMI) (Figure S2c)

Environmental Factors

- Cost and affordability of fast food

- b.

- Availability and accessibility of healthy food during work

“The dishes (from the cafeteria) were always added with MSG…a free soft drink would be included when you order meals. It certainly encouraged nurses to have the unhealthy drink per day.”(P2, A&E, underweight)

3.3.2. Facilitators to Healthy Eating

Individual Factors

- Palatability/perceived healthiness in food choice

“I do like having healthy food, it can make the condition of my skin better as well. Fruits after meal is a must to keep me healthy.”(P4, pediatric ICU, normal BMI)

“…I usually eat fruits with high vitamin C which helps to enhance immunity, such as orange, golden kiwi. Especially when I was moved out from my family, I paid more attention to the food I eat and consider to eat healthier”(P6, surgical, normal BMI)

- b.

- Personal knowledge

“…If I really want to eat starch, I will choose to eat buckwheat noodles. Sometimes I would choose to eat macaroni, which is the lower Glycemic Index food.”(P1, medical, normal BMI)

Social Factors

- Colleagues’ influence

- b.

- Family influence

“I would tell her (maid) that every meal must include meat and vegetables, sometimes fish, and more protein. As I have 2 kids, they need to have a balanced diet and the food choices of the children must be prioritized, especially they are in a developmental period. We did not let them consume fried food or ice cream, so as to us, we have to be a good role models for the children.”(P4, pediatric ICU, normal BMI)

Organizational Factors

- Workplace support

“(talking about her colleagues were united in eating healthy at work)… Even my senior colleagues have begun to eat healthily, but I am not sure if it was because they saw all the young nurses eating healthily, so they would like to join us during meal time. My boss even supported us by adding on some cooking utensils such as microwave oven in the pantry and encourages staff to make their own food during work.”(P1, medical, normal BMI)

““Fruit day” is held every year in my hospital, which aims to encourage staff to maintain healthy diet. Each of the staff will be given a kind of free fruit, such as banana, orange, apple during meal time. However, we might not always have time to enjoy the fruit during the day, so sometimes I will bring the fruits back home and take it afterwards. I do agree holding this kind of activity could help staff to maintain healthy eating during work, however, the frequency should be increased, maybe holding quarterly to maintain the sustainability.”(P2, A&E, underweight)

Environmental Factors

- Cost and affordability of healthy food

- b.

- Availability and accessibility of healthy food during work

“I am not a vegan but sometimes I still wanted to have some meat-free meals… It tasted so-so, but that was also a choice for us.”(P4, pediatric ICU, normal) (Figure S2h)

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Deficiencies in Dietary Fiber and Excessive Sodium Levels

4.2. Emotional Eating and Overweight/Obesity

4.3. Social Influence as an Enabler or Impediment Towards Healthy Eating

4.4. Workplace Support as the Key to Healthy Eating

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

4.6. Further Implications of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Word Health Organization. Nursing and Midwifery. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/nursing-and-midwifery (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Statistics of Registered Nurses. Available online: https://www.nchk.org.hk/en/statistics_and_lists_of_nurses/statistics/index.html (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, Department of Health. 2019 Health Manpower Survey on Registered Nurses. Available online: https://www.dh.gov.hk/english/statistics/statistics_hms/files/keyfinding_2019/keyfinding_rn19e.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Wong, H.; Wong, M.C.; Wong, S.Y.; Lee, A. The Association between Shift Duty and Abnormal Eating Behavior among Nurses Working in a Major Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Marko, S.; Wylie, S.; Utter, J. Enablers and Barriers to Healthy Eating among Hospital Nurses: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 138, 104412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gifkins, J.; Johnston, A.; Loudoun, R. The Impact of Shift Work on Eating Patterns and Self-Care Strategies Utilised by Experienced and Inexperienced Nurses. Chronobiol. Int. 2018, 35, 811–820. [Google Scholar]

- Books, C.; Coody, L.C.; Kauffman, R.; Abraham, S. Night Shift Work and Its Health Effects on Nurses. Health Care Manag. 2020, 39, 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Horton Dias, C.; Dawson, R.M. Hospital and Shift Work Influences on Nurses’ Dietary Behaviors: A Qualitative Study. Workplace Health Saf. 2020, 68, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cena, H.; Calder, P.C. Defining a Healthy Diet: Evidence for the Role of Contemporary Dietary Patterns in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowden, A.; Moreno, C.; Holmbäck, U.; Lennernäs, M.; Tucker, P. Eating and Shift Work—Effects on Habits, Metabolism, and Performance. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2010, 36, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Diet Suggestions for Night-Shift Nurses. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/work-hour-training-for-nurses/longhours/mod9/08.html (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Hong Kong Dietitians Association. Guide for Healthy Eating. Available online: https://www.hkda.com.hk/post/20 (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Han, K.; Choi-Kwon, S.; Kim, K.S. Poor Dietary Behaviors among Hospital Nurses in Seoul, South Korea. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2016, 30, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, M.S.; Lam, S.K. Antecedents and Contextual Factors Affecting Occupational Turnover among Registered Nurses in Public Hospitals in Hong Kong: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.; Garcia, A.C.; Leipert, B. Photovoice and Its Potential Use in Nutrition and Dietetic Research. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2010, 71, 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterbroek, T.; Yonge, O.; Myrick, F. Participatory Action Research and Photovoice: Applicability, Relevance, and Process in Nursing Education Research. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2021, 42, E114–E116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ. Behav. Off. Publ. Soc. Public Health Educ. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health, the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Body Mass Index Chart. Available online: https://www.chp.gov.hk/en/resources/e_health_topics/pdfwav_11012.html (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Chan, V.W.-K.; Zhou, J.H.-S.; Li, L.; Tse, M.T.-H.; You, J.J.; Wong, M.-S.; Liu, J.Y.-W.; Lo, K.K.-H. Reproducibility and Relative Validity of a Short Food Frequency Questionnaire for Chinese Older Adults in Hong Kong. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinese Nutrition Society. Dietary Reference Intakes for China; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, R.M.; Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; López-Sobaler, A.M. Dietary Assessment Methods: Dietary Records. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 31, 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka, K.; Deguchi, K.; Ushiroda, C.; Yanagi, K.; Seino, Y.; Suzuki, A.; Yabe, D.; Sasaki, H.; Sasaki, S.; Saitoh, E. A Study on the Compatibility of a Food-Recording Application with Questionnaire-Based Methods in Healthy Japanese Individuals. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar]

- Törnbom, K.; Lundälv, J.; Palstam, A.; Sunnerhagen, K.S. “My Life after Stroke through a Camera Lens”—A Photovoice Study on Participation in Sweden. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trübswasser, U.; Baye, K.; Holdsworth, M.; Loeffen, M.; Feskens, E.J.; Talsma, E.F. Assessing Factors Influencing Adolescents’ Dietary Behaviours in Urban Ethiopia Using Participatory Photography. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 3615–3623. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, G.K.; Huggins, K.E.; Bonham, M.P.; Kleve, S. Exploring Australian Night Shift Workers’ Food Experiences within and Outside of the Workplace: A Qualitative Photovoice Study. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 2276–2287. [Google Scholar]

- Kaliyadan, F.; Kulkarni, V. Types of Variables, Descriptive Statistics, and Sample Size. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2019, 10, 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saunders, B.; Kitzinger, J.; Kitzinger, C. Anonymising Interview Data: Challenges and Compromise in Practice. Qual. Res. 2015, 15, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nicholls, R.; Perry, L.; Duffield, C.; Gallagher, R.; Pierce, H. Barriers and Facilitators to Healthy Eating for Nurses in the Workplace: An Integrative Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 1051–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Report of Population Health Survey 2020–22 (Part I). Available online: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/dh_phs_2020-22_part_1_report_eng_rectified.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Report of Population Health Survey 2020–22 (Part II). Available online: https://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/dh_phs_2020-22_part_2_report_eng.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- de Barcellos, M.D.; Perin, M.G.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Grunert, K.G. Cooking Readiness in Stressful Times: Navigating Food Choices for a Healthier Future. Appetite 2024, 203, 107652. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ma, G. Food, Eating Behavior, and Culture in Chinese Society. J. Ethn. Foods 2015, 2, 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Chair, S.Y.; Lo, S.H.S.; Chau, J.P.-C.; Schwade, M.; Zhao, X. Association between Shift Work and Obesity among Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 112, 103757. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, T.; Yip, P.S. Depression, Anxiety and Symptoms of Stress among Hong Kong Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 11072–11100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandhu, D.; Mohan, M.M.; Nittala, N.A.P.; Jadhav, P.; Bhadauria, A.; Saxena, K.K. Theories of Motivation: A Comprehensive Analysis of Human Behavior Drivers. Acta Psychol. 2024, 244, 104177. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, C.T.; Pronovost, P.J.; Marsteller, J.A. Harnessing the Power of Peer Influence to Improve Quality. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2018, 33, 549–551. [Google Scholar]

- Sajwani, A.I.; Hashi, F.; Abdelghany, E.; Alomari, A.; Alananzeh, I. Workplace Barriers and Facilitators to Nurses’ Healthy Eating Behaviours: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Contemp. Nurse 2024, 60, 270–299. [Google Scholar]

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors Influencing Children’s Eating Behaviours. Nutrients 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glanz, K.; Metcalfe, J.J.; Folta, S.C.; Brown, A.; Fiese, B. Diet and Health Benefits Associated with in-Home Eating and Sharing Meals at Home: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foncubierta-Rodríguez, M.-J.; Poza-Méndez, M.; Holgado-Herrero, M. Workplace Health Promotion Programs: The Role of Compliance with Workers’ Expectations, the Reputation and the Productivity of the Company. J. Saf. Res. 2024, 89, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Amiri, M.; Li, J.; Hasan, W. Personalized Flexible Meal Planning for Individuals with Diet-Related Health Concerns: System Design and Feasibility Validation Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e46434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Elder-Robinson, E.; Howard, K.; Garvey, G. A Systematic Methods Review of Photovoice Research with Indigenous Young People. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231172076. [Google Scholar]

| Participant | Working Department | Sex (Age) | Marital Status | Years of Experience | No. of Night Shift per Month | BMI | BMl Classification * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Medical | F (28) | Single (Live with family) | 5 | 5-6 | 21.9 (160/56) | Normal |

| 2 | A&E | F (27) | Single (Live with family) | 4 | 4 | 18.3 (155/44) | Underweight |

| 3 | OBS (midwife) | F (30) | Single (Live with family) | 3 | 5 | 25.7 (165/70) | Obese |

| 4 | Pediatric ICU | F (37) | Married (2 children: 4 and 6 yo) | 10 | 4 | 21.3 (162/56) | Normal |

| 5 | Operating Theater | F (32) | Single (Live with boyfriend) | 6 | 4 | 20 (155/48) | Normal |

| 6 | Surgical | M (42) | Married (No children) | 8 | 5 | 22.2 (175/68) | Normal |

| 7 | Medical | M (50) | Single (Live alone) | 25 | 5 | 23.9 (177/75) | Overweight |

| 8 | ICU | M (29) | Single (Live with family) | 6 | 5 | 23.8 (169/68) | Overweight |

| 9 | Surgical | M (45) | Married (1 child: 15 yo) | 18 | 5 | 22.2 (18072) | Normal |

| Barriers | Facilitators | |

|---|---|---|

| Main Category | Sub-Category | Sub-Category |

| Individual | Comfort food and emotional eating | Palatability |

| Palatability | Personal knowledge | |

| Personal perception, attitude, and health issues | Perceived healthiness in food choice | |

| Social | Colleagues’ influence/appreciations from patients | Colleagues’ influence |

| Family influence | Family influence | |

| Organizational | Shift work nature | Workplace support |

| Sudden change of work schedule | ||

| Meal break availability | ||

| Environmental | Cost and affordability of fast food | Cost and affordability of healthy food |

| Availability and accessibility of healthy food during work | Availability and accessibility of healthy food during work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ling, P.-L.; Lai, Z.-Y.; Cheng, H.-L.; Lo, K.-H. Barriers and Facilitators to Healthy Eating for Shift-Work-Registered Nurses in Hong Kong Public Hospitals: An Exploratory Multi-Method Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071162

Ling P-L, Lai Z-Y, Cheng H-L, Lo K-H. Barriers and Facilitators to Healthy Eating for Shift-Work-Registered Nurses in Hong Kong Public Hospitals: An Exploratory Multi-Method Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(7):1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071162

Chicago/Turabian StyleLing, Pui-Lam, Zhi-Yang Lai, Hui-Lin Cheng, and Ka-Hei Lo. 2025. "Barriers and Facilitators to Healthy Eating for Shift-Work-Registered Nurses in Hong Kong Public Hospitals: An Exploratory Multi-Method Study" Nutrients 17, no. 7: 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071162

APA StyleLing, P.-L., Lai, Z.-Y., Cheng, H.-L., & Lo, K.-H. (2025). Barriers and Facilitators to Healthy Eating for Shift-Work-Registered Nurses in Hong Kong Public Hospitals: An Exploratory Multi-Method Study. Nutrients, 17(7), 1162. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17071162