Extended Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Early Breast Cancer Patients—Review and Perspectives

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Relevant Section

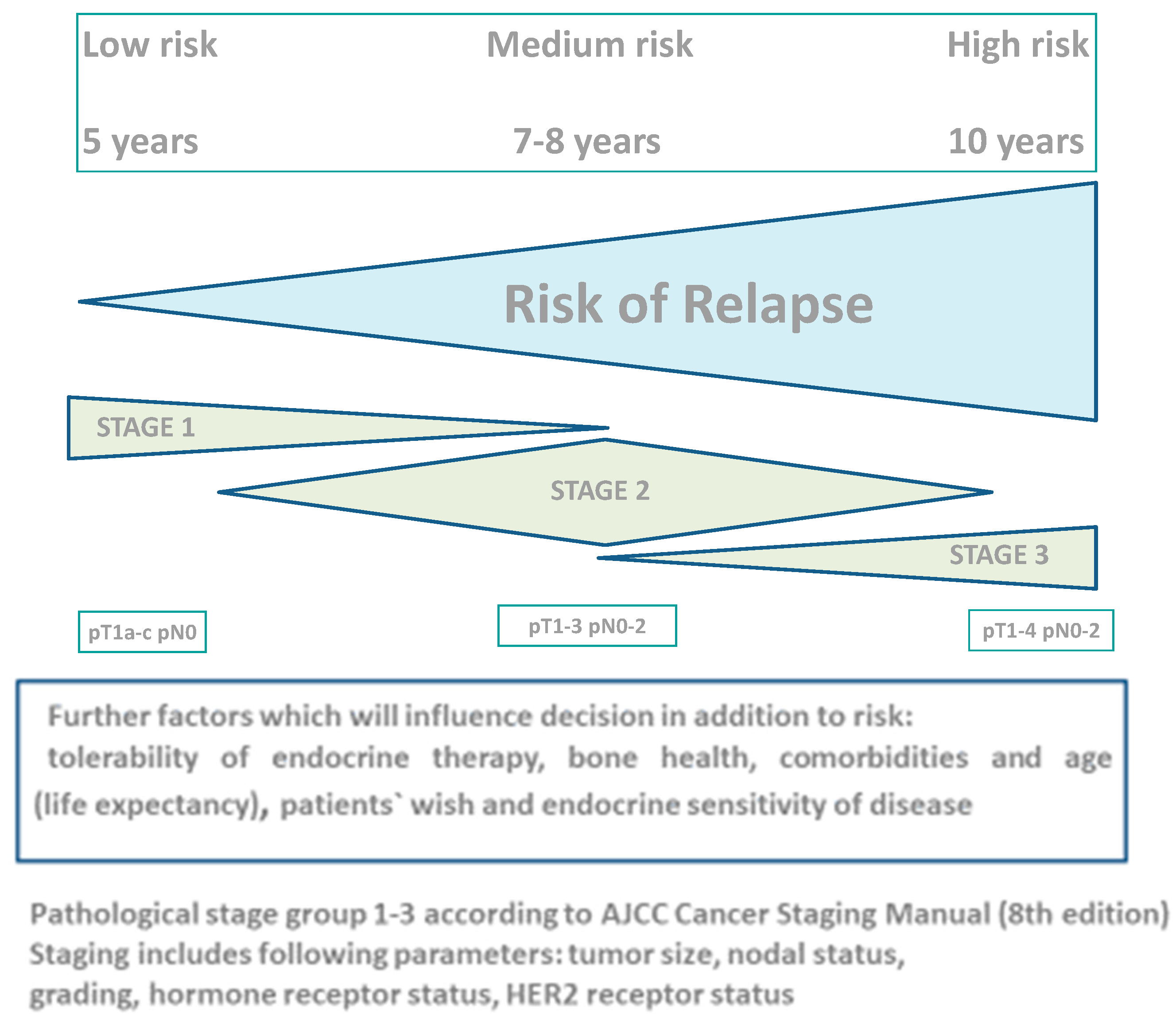

2.1. Risk of Relapse after 5 Years of Endocrine Therapy

2.2. Five-Year Duration of Endocrine Therapy—Current Data

2.3. Optimal Duration of Extended Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy: 5, 7 to 8, or 10 Years?

2.4. Ten Years versus Five Years of Endocrine Therapy

2.5. Seven to Eight Years versus Five Years of Endocrine Therapy

2.6. Ten Years of Endocrine Therapy versus Seven to Eight Years

2.7. Intermittent versus Continuous Extended Therapy

2.8. Side Effects

2.9. Optimal Duration of Extended Endocrine Therapy

2.10. Individualization of Extended Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy

3. Role of Other Receptor-Targeting Agents—Current and Future Aspects

4. Conclusions and Further Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miller, K.D.; Nogueira, L.; Mariotto, A.B.; Rowland, J.H.; Yabroff, K.R.; Alfano, C.M.; Jemal, A.; Kramer, J.L.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waks, A.G.; Winer, E.P. Breast Cancer Treatment: A Review. JAMA 2019, 321, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, O.; Abe, R.; Enomoto, K.; Kikuchi, K.; Koyama, H.; Masuda, H.; Nomura, Y.; Ohashi, Y.; Sakai, K.; Sugimachi, K.; et al. Relevance of Breast Cancer Hormone Receptors and Other Factors to the Efficacy of Adjuvant Tamoxifen: Patient-Level Meta-Analysis of Randomised Trials. Lancet 2011, 378, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.; Burrett, J.; Clarke, M.; Davies, C.; Duane, F.; Evans, V.; Gettins, L.; Godwin, J.; Gray, R.; Liu, H.; et al. Aromatase Inhibitors versus Tamoxifen in Early Breast Cancer: Patient-Level Meta-Analysis of the Randomised Trials. Lancet 2015, 386, 1341–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, E.; Seruga, B.; Niraula, S.; Carlsson, L.; Ocaña, A. Toxicity of Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Postmenopausal Breast Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011, 103, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard-Anderson, J.; Ganz, P.A.; Bower, J.E.; Stanton, A.L. Quality of Life, Fertility Concerns, and Behavioral Health Outcomes in Younger Breast Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012, 104, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, P.E.; Ingle, J.N.; Pritchard, K.I.; Robert, N.J.; Muss, H.; Gralow, J.; Gelmon, K.; Whelan, T.; Strasser-Weippl, K.; Rubin, S.; et al. Extending Aromatase-Inhibitor Adjuvant Therapy to 10 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B.; Dignam, J.; Bryant, J.; DeCillis, A.; Wickerham, D.L.; Wolmark, N.; Costantino, J.; Redmond, C.; Fisher, E.R.; Bowman, D.M.; et al. Five versus More than Five Years of Tamoxifen Therapy for Breast Cancer Patients with Negative Lymph Nodes and Estrogen Receptor-Positive Tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1996, 88, 1529–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, P.E.; Ingle, J.N.; Martino, S.; Robert, N.J.; Muss, H.B.; Piccart, M.J.; Castiglione, M.; Tu, D.; Shepherd, L.E.; Pritchard, K.I.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Letrozole in Postmenopausal Women after Five Years of Tamoxifen Therapy for Early-Stage Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 1793–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, N.L.; Azzouz, F.; Desta, Z.; Li, L.; Nguyen, A.T.; Lemler, S.; Hayden, J.; Tarpinian, K.; Yakim, E.; Flockhart, D.A.; et al. Predictors of Aromatase Inhibitor Discontinuation as a Result of Treatment-Emergent Symptoms in Early-Stage Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Gray, R.; Braybrooke, J.; Davies, C.; Taylor, C.; McGale, P.; Peto, R.; Pritchard, K.I.; Bergh, J.; Dowsett, M.; et al. 20-Year Risks of Breast-Cancer Recurrence after Stopping Endocrine Therapy at 5 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1836–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutqvist, L.E.; Hatschek, T.; Rydén, S.; Bergh, J.; Bengtsson, N.O.; Carstenssen, J.; Nordenskjöld, B.; Wallgren, A. Randomized Trial of Two versus Five Years of Adjuvant Tamoxifen for Postmenopausal Early Stage Breast Cancer. Swedish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1996, 88, 1543–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Placido, S.; Gallo, C.; De Laurentiis, M.; Bisagni, G.; Arpino, G.; Sarobba, M.G.; Riccardi, F.; Russo, A.; Del Mastro, L.; Cogoni, A.A.; et al. Adjuvant Anastrozole versus Exemestane versus Letrozole, Upfront or after 2 Years of Tamoxifen, in Endocrine-Sensitive Breast Cancer (FATA-GIM3): A Randomised, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Pan, H.; Godwin, J.; Gray, R.; Arriagada, R.; Raina, V.; Abraham, M.; Medeiros Alencar, V.H.; Badran, A.; Bonfill, X.; et al. Long-Term Effects of Continuing Adjuvant Tamoxifen to 10 Years versus Stopping at 5 Years after Diagnosis of Oestrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: ATLAS, a Randomised Trial. Lancet 2013, 381, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.G.; Rea, D.; Handley, K.; Bowden, S.J.; Perry, P.; Earl, H.M.; Poole, C.J.; Bates, T.; Chetiyawardana, S.; Dewar, J.A.; et al. aTTom: Long-term effects of continuing adjuvant tamoxifen to 10 years versus stopping at 5 years in 6953 women with early breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, P.E.; Ingle, J.N.; Martino, S.; Robert, N.J.; Muss, H.B.; Piccart, M.J.; Castiglione, M.; Tu, D.; Shepherd, L.E.; Pritchard, K.I.; et al. Randomized Trial of Letrozole Following Tamoxifen as Extended Adjuvant Therapy in Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: Updated Findings from NCIC CTG MA.17. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 1262–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamounas, E.P.; Bandos, H.; Lembersky, B.C.; Jeong, J.H.; Geyer, C.E.; Rastogi, P.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Graham, M.L.; Chia, S.K.; Brufsky, A.M.; et al. Use of Letrozole after Aromatase Inhibitor-Based Therapy in Postmenopausal Breast Cancer (NRG Oncology/NSABP B-42): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjan-Heijnen, V.C.G.; van Hellemond, I.E.G.; Peer, P.G.M.; Swinkels, A.C.P.; Smorenburg, C.H.; van der Sangen, M.J.C.; Kroep, J.R.; De Graaf, H.; Honkoop, A.H.; Erdkamp, F.L.G.; et al. Extended Adjuvant Aromatase Inhibition after Sequential Endocrine Therapy (DATA): A Randomised, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1502–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Mastro, L.; Mansutti, M.; Bisagni, G.; Ponzone, R.; Durando, A.; Amaducci, L.; Campadelli, E.; Cognetti, F.; Frassoldati, A.; Michelotti, A.; et al. Extended Therapy with Letrozole as Adjuvant Treatment of Postmenopausal Patients with Early-Stage Breast Cancer: A Multicentre, Open-Label, Randomised, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1458–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, E.J.; Kroep, J.R.; Kranenbarg, E.M.K.; Duijm-De Carpentier, M.; Putter, H.; Van Den Bosch, J.; Maartense, E.; Van Leeuwen-Stok, A.E.; Liefers, G.J.; Nortier, J.W.R.; et al. Optimal Duration of Extended Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Early Breast Cancer; Results of the IDEAL Trial (BOOG 2006-05). J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnant, M.; Fitzal, F.; Rinnerthaler, G.; Steger, G.G.; Greil-Ressler, S.; Balic, M.; Heck, D.; Jakesz, R.; Thaler, J.; Egle, D.; et al. Duration of Adjuvant Aromatase-Inhibitor Therapy in Postmenopausal Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colleoni, M.; Luo, W.; Karlsson, P.; Chirgwin, J.; Aebi, S.; Jerusalem, G.; Neven, P.; Hitre, E.; Graas, M.P.; Simoncini, E.; et al. Extended Adjuvant Intermittent Letrozole versus Continuous Letrozole in Postmenopausal Women with Breast Cancer (SOLE): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Randomised, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabnis, G.J.; Macedo, L.F.; Goloubeva, O.; Schayowitz, A.; Brodie, A.M.H. Stopping Treatment Can Reverse Acquired Resistance to Letrozole. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 4518–4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerusalem, G.; Farah, S.; Courtois, A.; Chirgwin, J.; Aebi, S.; Karlsson, P.; Neven, P.; Hitre, E.; Graas, M.P.; Simoncini, E.; et al. Continuous versus Intermittent Extended Adjuvant Letrozole for Breast Cancer: Final Results of Randomized Phase III SOLE (Study of Letrozole Extension) and SOLE Estrogen Substudy. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1256–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, A.H.; Niman, S.M.; Ruggeri, M.; Peccatori, F.A.; Azim, H.A., Jr.; Colleoni, M.; Saura, C.; Shimizu, C.; Sætersdal, A.B.; Kroep, J.R.; et al. POSITIVE Trial Collaborators. Interrupting Endocrine Therapy to Attempt Pregnancy after Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1645–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Ren, D.; Shen, G.; Ahmad, R.; Dong, L.; Du, F.; Zhao, J. Toxicity of Extended Adjuvant Endocrine with Aromatase Inhibitors in Patients with Postmenopausal Breast Cancer: A Systemtic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2020, 156, 103114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamounas, E.P.; Jeong, J.H.; Lawrence Wickerham, D.; Smith, R.E.; Ganz, P.A.; Land, S.R.; Eisen, A.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Farrar, W.B.; Atkins, J.N.; et al. Benefit from Exemestane as Extended Adjuvant Therapy after 5 Years of Adjuvant Tamoxifen: Intention-to-Treat Analysis of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast And Bowel Project B-33 Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 1965–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B.; Costantino, J.P.; Wickerham, D.L.; Redmond, C.K.; Kavanah, M.; Cronin, W.M.; Vogel, V.; Robidoux, A.; Dimitrov, N.; Atkins, J.; et al. Tamoxifen for Prevention of Breast Cancer: Report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1998, 90, 1371–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, P.E.; Ingle, J.N.; Alés-Martínez, J.E.; Cheung, A.M.; Chlebowski, R.T.; Wactawski-Wende, J.; McTiernan, A.; Robbins, J.; Johnson, K.C.; Martin, L.W.; et al. Exemestane for Breast-Cancer Prevention in Postmenopausal Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2381–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sestak, I.; Harvie, M.; Howell, A.; Forbes, J.F.; Dowsett, M.; Cuzick, J. Weight Change Associated with Anastrozole and Tamoxifen Treatment in Postmenopausal Women with or at High Risk of Developing Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 134, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershman, D.L.; Shao, T.; Kushi, L.H.; Buono, D.; Tsai, W.Y.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Kwan, M.; Gomez, S.L.; Neugut, A.I. Early Discontinuation and Non-Adherence to Adjuvant Hormonal Therapy Are Associated with Increased Mortality in Women with Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 126, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loprinzi, C.L.; Barton, D.L.; Rhodes, D. Management of Hot Flashes in Breast-Cancer Survivors. Lancet Oncol. 2001, 2, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, V.; Ullmer, L.; Lopez, J.F.; Smith, Y.; Isaacs, C.; Hayes, D.F. Hot Flushes. Lancet 2002, 360, 1851–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, N.L.; Banerjee, M.; Wicha, M.; Van Poznak, C.; Smerage, J.B.; Schott, A.F.; Griggs, J.J.; Hayes, D.F. Pilot Study of Duloxetine for Treatment of Aromatase Inhibitor-Associated Musculoskeletal Symptoms. Cancer 2011, 117, 5469–5475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loprinzi, C.L.; Abu-Ghazaleh, S.; Sloan, J.A.; vanHaelst-Pisani, C.; Hammer, A.M.; Rowland, K.M.; Law, M.; Windschitl, H.E.; Kaur, J.S.; Ellison, N. Phase III Randomized Double-Blind Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of a Polycarbophil-Based Vaginal Moisturizer in Women with Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15, 969–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetsch, M.F.; Lim, J.Y.; Caughey, A.B. A Practical Solution for Dyspareunia in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3394–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brufsky, A.; Harker, W.G.; Beck, J.T.; Carroll, R.; Tan-Chiu, E.; Seidler, C.; Hohneker, J.; Lacerna, L.; Petrone, S.; Perez, E.A. Zoledronic Acid Inhibits Adjuvant Letrozole-Induced Bone Loss in Postmenopausal Women with Early Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, H.J.; Lacchetti, C.; Anderson, H.; Buchholz, T.A.; Davidson, N.E.; Gelmon, K.A.; Giordano, S.H.; Hudis, C.A.; Solky, A.J.; Stearns, V.; et al. Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy for Women With Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Focused Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, F.; Ismaila, N.; Allison, K.H.; Barlow, W.E.; Collyar, D.E.; Damodaran, S.; Henry, N.L.; Jhaveri, K.; Kalinsky, K.; Kuderer, N.M.; et al. Biomarkers for Adjuvant Endocrine and Chemotherapy in Early-Stage Breast Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 1816–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.M.S.; Sgroi, D.C.; Treuner, K.; Zhang, Y.; Ahmed, I.; Piper, T.; Salunga, R.; Brachtel, E.F.; Pirrie, S.J.; Schnabel, C.A.; et al. Breast Cancer Index and Prediction of Benefit from Extended Endocrine Therapy in Breast Cancer Patients Treated in the Adjuvant Tamoxifen-To Offer More? (ATTom) Trial. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1776–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordhoek, I.; Treuner, K.; Putter, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wong, J.; Kranenbarg, E.M.K.; De Carpentier, M.D.; van de Velde, C.J.H.; Schnabel, C.A.; Liefers, G.J. Breast Cancer Index Predicts Extended Endocrine Benefit to Individualize Selection of Patients with HR+ Early-Stage Breast Cancer for 10 Years of Endocrine Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, D.C.; Carney, E.; Zarrella, E.; Steffel, L.; Binns, S.N.; Finkelstein, D.M.; Szymonifka, J.; Bhan, A.K.; Shepherd, L.E.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Prediction of Late Disease Recurrence and Extended Adjuvant Letrozole Benefit by the HOXB13/IL17BR Biomarker. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, J.O.; Spring, L.M.; Bardia, A.; Wander, S.A. ESR1 mutation as an emerging clinical biomarker in metastatic hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2021, 23, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidard, F.C.; Kaklamani, V.G.; Neven, P.; Streich, G.; Montero, A.J.; Forget, F.; Mouret-Reynier, M.A.; Sohn, J.H.; Taylor, D.; Harnden, K.K.; et al. Elacestrant (oral selective estrogen receptor degrader) Versus Standard Endocrine Therapy for Estrogen Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Advanced Breast Cancer: Results From the Randomized Phase III EMERALD Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 3246–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Hegg, R.; Kim, S.B.; Schenker, M.; Grecea, D.; Garcia-Saenz, J.A.; Papazisis, K.; Ouyang, Q.; Lacko, A.; Oksuzoglu, B.; et al. Treatment With Adjuvant Abemaciclib Plus Endocrine Therapy in Patients With High-risk Early Breast Cancer Who Received Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy: A Prespecified Analysis of the monarchE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 1190–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slamon, D.J.; Fasching, P.A.; Hurvitz, S.; Chia, S.; Crown, J.; Martín, M.; Barrios, C.H.; Bardia, A.; Im, S.A.; Yardley, D.A.; et al. Rationale and trial design of NATALEE: A Phase III trial of adjuvant ribociclib + endocrine therapy versus endocrine therapy alone in patients with HR+/HER2- early breast cancer. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2023, 15, 17588359231178125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Studies | Treated Patients 1 | Follow-Up (months) | Disease-Free Survival | Overall Survival | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 versus 10 years (tamoxifen) | ATTOM/ATLAS (pre-and postmenopausal) MA-17 1 | 13,799 5187 | 108/120 80 | sig sig | sig sig (only N+) |

| 5 versus 10 years (aromatase inhibitor) | NSABP B-42 1 MA-17R 1 | 3923 1918 | 82.8 75.6 | not sig sig (DRFS) 2 sig | not sig not sig |

| 5–6 versus 7–8 years | DATA 1 GIM-4 1 | 1860 2056 | 49.2 140.4 | not sig (+) 3 sig | not sig sig |

| 7–8 versus 10 years | IDEAL 1 ABCSG 16 1 | 1824 3484 | 79.2 118 | not sig not sig | not sig not sig |

| Studies | Side Effects (Toxicities) | |

|---|---|---|

| 5 versus 10 years (tamoxifen) 5 years AI vs. placebo after 5 years tamoxifen | ATTOM/ATLAS MA-17 | More endometrial cancer, thromboembolic events with longer therapy (ischemic cardiac events reduced) More hormonally related side effects with AI |

| 5 versus 10 years (aromatase inhibitor) | NSABP B-42 MA-17R | More arterial thromboembolic events with longer therapy More bone-related toxic events with longer therapy |

| 7–8 versus 10 years | IDEAL ABCSG 16 | No difference in side effects More bone fractures with longer therapy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bekes, I.; Huober, J. Extended Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Early Breast Cancer Patients—Review and Perspectives. Cancers 2023, 15, 4190. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15164190

Bekes I, Huober J. Extended Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Early Breast Cancer Patients—Review and Perspectives. Cancers. 2023; 15(16):4190. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15164190

Chicago/Turabian StyleBekes, Inga, and Jens Huober. 2023. "Extended Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Early Breast Cancer Patients—Review and Perspectives" Cancers 15, no. 16: 4190. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15164190

APA StyleBekes, I., & Huober, J. (2023). Extended Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy in Early Breast Cancer Patients—Review and Perspectives. Cancers, 15(16), 4190. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15164190