Type IX Collagen Turnover Is Altered in Patients with Solid Tumors

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

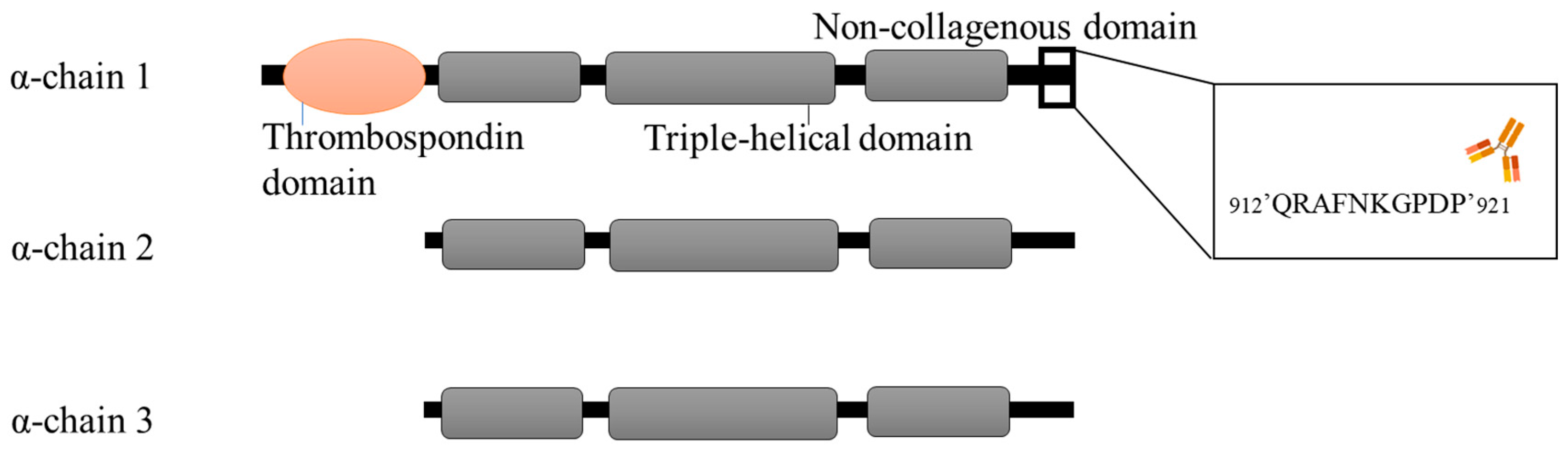

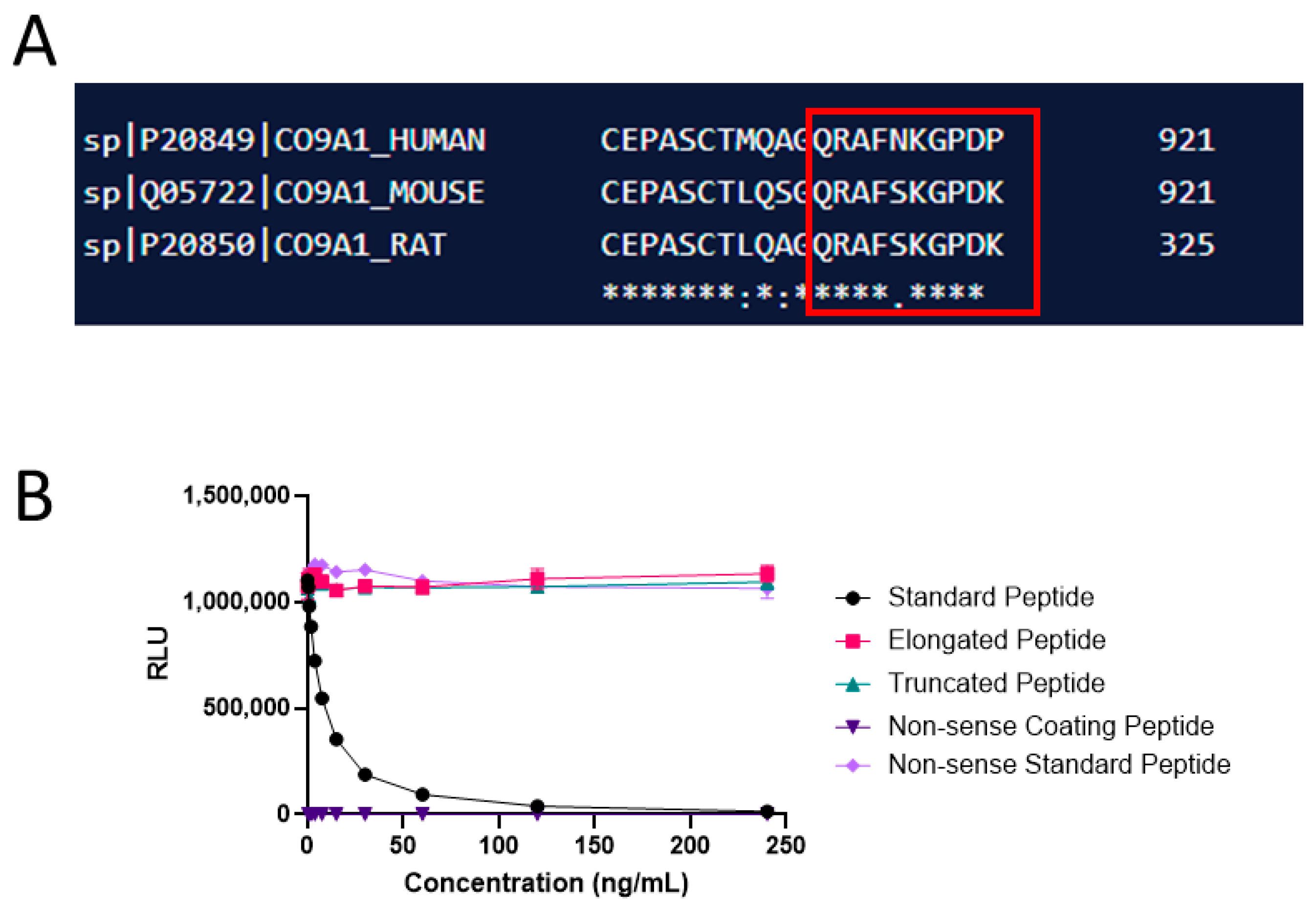

2.1. Monoclonal Antibody Development, Production, and Characterization

2.2. PRO-C9 Assay Development

2.3. Technical Evaluation

2.4. Biological Evaluation of PRO-C9

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Technical Evaluation and Characterization of PRO-C9

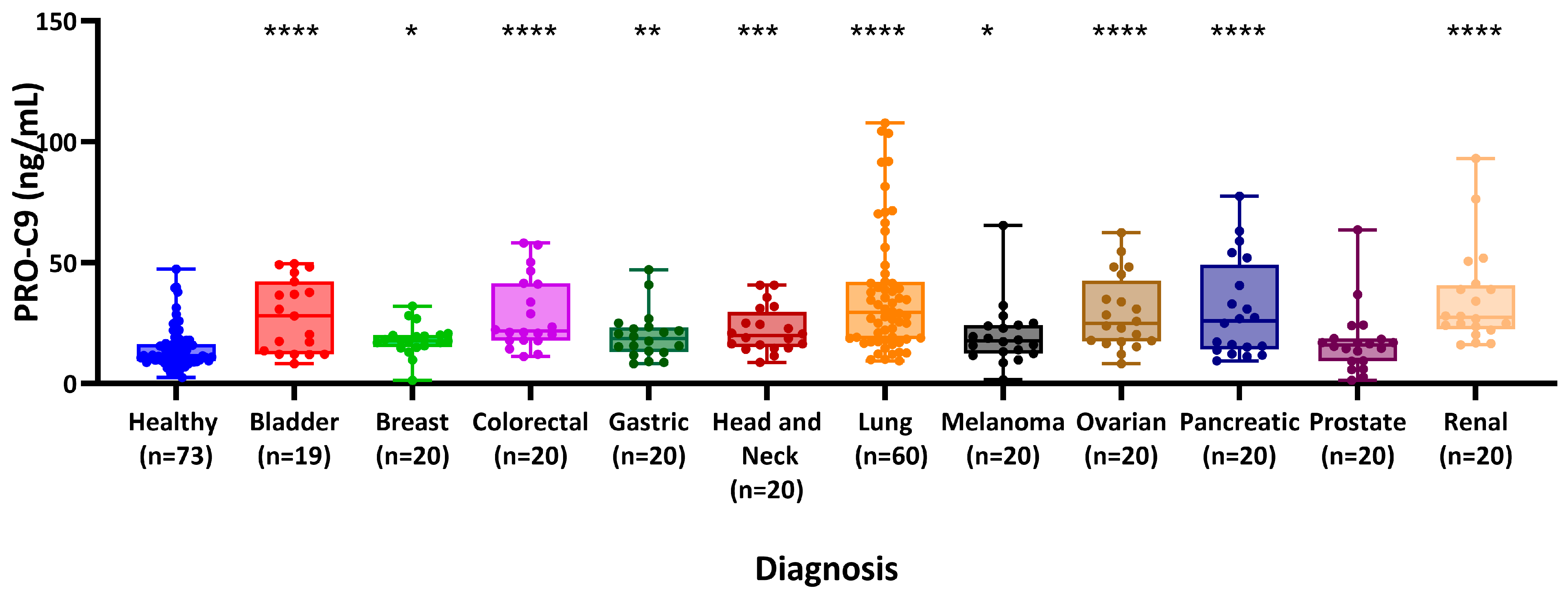

3.2. PRO-C9 Is Elevated in Patients with Various Types of Cancers Compared to Healthy Controls

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frantz, C.; Stewart, K.M.; Weaver, V.M. The extracellular matrix at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 4195–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsdal, M.A.; Nielsen, M.J.; Sand, J.M.; Henriksen, K.; Genovese, F.; Bay-Jensen, A.C.; Smith, V.; Adamkewicz, J.I.; Christiansen, C.; Leeming, D.J. Extracellular matrix remodeling: The common denominator in connective tissue diseases possibilities for evaluation and current understanding of the matrix as more than a passive architecture, but a key player in tissue failure. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2013, 11, 70–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, T.R.; Erler, J.T. Remodeling and homeostasis of the extracellular matrix: Implications for fibrotic diseases and cancer. Dis. Model. Mech. 2011, 4, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickup, M.W.; Mouw, J.K.; Weaver, V.M. The extracellular matrix modulates the hallmarks of cancer. EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnans, C.; Chou, J.; Werb, Z. Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 786–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricard-Blum, S. The Collagen Family. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanjore, H.; Kalluri, R. The Role of Type IV Collagen and Basement Membranes in Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 168, 715–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissen, N.I.; Karsdal, M.; Willumsen, N. Collagens and Cancer associated fibroblasts in the reactive stroma and its relation to Cancer biology. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.; Abisoye-Ogunniyan, A.; Metcalf, K.J.; Werb, Z. Concepts of extracellular matrix remodelling in tumour progression and metastasis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.D.; Jensen, C.; Larsen, O.; Leerhøy, B.; Hansen, C.P.; Madsen, K.; Høgdall, D.; Karsdal, M.A.; Chen, I.M.; Nielsen, D.; et al. Blood-based tumor fibrosis markers as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in patients with biliary tract cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 152, 1036–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willumsen, N.; Jensen, C.; Green, G.; Nissen, N.I.; Neely, J.; Nelson, D.M.; Pedersen, R.S.; Frederiksen, P.; Chen, I.M.; Boisen, M.K.; et al. Fibrotic activity quantified in serum by measurements of type III collagen pro-peptides can be used for prognosis across different solid tumor types. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissen, N.I.; Johansen, A.Z.; Chen, I.; Johansen, J.S.; Pedersen, R.S.; Hansen, C.P.; Karsdal, M.A.; Willumsen, N. Collagen Biomarkers Quantify Fibroblast Activity In Vitro and Predict Survival in Patients with Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.L.; Bager, C.L.; Willumsen, N.; Ramchandani, D.; Kornhauser, N.; Ling, L.; Cobham, M.; Andreopoulou, E.; Cigler, T.; Moore, A.; et al. Tetrathiomolybdate (TM)-associated copper depletion influences collagen remodeling and immune response in the pre-metastatic niche of breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2021, 7, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissen, N.I.; Kehlet, S.; Boisen, M.K.; Liljefors, M.; Jensen, C.; Johansen, A.Z.; Johansen, J.S.; Erler, J.T.; Karsdal, M.; Mortensen, J.H.; et al. Prognostic value of blood-based fibrosis biomarkers in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving chemotherapy and bevacizumab. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.; Holm Nielsen, S.; Eslam, M.; Genovese, F.; Nielsen, M.J.; Vongsuvanh, R.; Uchila, R.; van der Poorten, D.; George, J.; Karsdal, M.A.; et al. Cross-Linked Multimeric Pro-Peptides of Type III Collagen (PC3X) in Hepatocellular Carcinoma—A Biomarker That Provides Additional Prognostic Value in AFP Positive Patients. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 2020, 7, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurkmans, D.P.; Jensen, C.; Koolen, S.L.W.; Aerts, J.; Karsdal, M.A.; Mathijssen, R.H.J.; Willumsen, N. Blood-based extracellular matrix biomarkers are correlated with clinical outcome after PD-1 inhibition in patients with metastatic melanoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e001193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, A.; Leitzel, K.; Ali, S.M.; Polimera, H.V.; Nagabhairu, V.; Marks, E.; Richardson, A.E.; Krecko, L.; Ali, A.; Koestler, W.; et al. High turnover of extracellular matrix reflected by specific protein fragments measured in serum is associated with poor outcomes in two metastatic breast cancer cohorts. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 3027–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, E.A.; Thorlacius-Ussing, J.; Nissen, N.I.; Jensen, C.; Chen, I.M.; Johansen, J.S.; Diab, H.M.H.; Jørgensen, L.N.; Hansen, C.P.; Karsdal, M.A.; et al. Type XXII Collagen Complements Fibrillar Collagens in the Serological Assessment of Tumor Fibrosis and the Outcome in Pancreatic Cancer. Cells 2022, 11, 3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorlacius-Ussing, J.; Manon-Jensen, T.; Sun, S.; Leeming, D.J.; Sand, J.M.; Karsdal, M.; Willumsen, N. Serum Type XIX Collagen is Significantly Elevated in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Preliminary Study on Biomarker Potential. Cancers 2020, 12, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorlacius-Ussing, J.; Jensen, C.; Madsen, E.A.; Nissen, N.I.; Manon-Jensen, T.; Chen, I.M.; Johansen, J.S.; Diab, H.M.H.; Jørgensen, L.N.; Karsdal, M.A.; et al. Type XX Collagen Is Elevated in Circulation of Patients with Solid Tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.; Nielsen, S.H.; Mortensen, J.H.; Kjeldsen, J.; Klinge, L.G.; Krag, A.; Harling, H.; Jørgensen, L.N.; Karsdal, M.A.; Willumsen, N. Serum type XVI collagen is associated with colorectal cancer and ulcerative colitis indicating a pathological role in gastrointestinal disorders. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 4619–4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Rest, M.; Mayne, R.; Ninomiya, Y.; Seidah, N.G.; Chretien, M.; Olsen, B.R. The structure of type IX collagen. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1985, 460, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naba, A.; Clauser, K.R.; Whittaker, C.A.; Carr, S.A.; Tanabe, K.K.; Hynes, R.O. Extracellular matrix signatures of human primary metastatic colon cancers and their metastases to liver. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amenta, P.S.; Hadad, S.; Lee, M.T.; Barnard, N.; Li, D.; Myers, J.C. Loss of types XV and XIX collagen precedes basement membrane invasion in ductal carcinoma of the female breast. J. Pathol. 2003, 199, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramont, L.; Brassart-Pasco, S.; Thevenard, J.; Deshorgue, A.; Venteo, L.; Laronze, J.Y.; Pluot, M.; Monboisse, J.-C.; Maquart, F.-X. The NC1 domain of type XIX collagen inhibits in vivo melanoma growth. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007, 6, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B. The mechanics of fibrillar collagen extracellular matrix. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsdal, M. Biochemistry of Collagens, Laminins and Elastin; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gefter, M.L.; Margulies, D.H.; Scharff, M.D. A simple method for polyethylene glycol-promoted hybridization of mouse myeloma cells. Somat. Cell Mol. Genet. 1977, 3, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C.-M.; Lee, C.-H.; Chen, M.-K.; Lee, K.-W.; Lan, C.-C.E.; Kwan, A.-L.; Tsai, M.-H.; Ko, Y.-C. Combined Genetic Biomarkers and Betel Quid Chewing for Identifying High-Risk Group for Oral Cancer Occurrence. Cancer Prev. Res. 2017, 10, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotrowski, A.; Benetkiewicz, M.; Menzel, U.; de Ståhl, T.D.; Mantripragada, K.; Grigelionis, G.; Buckley, P.G.; Jankowski, M.; Hoffman, J.; Bała, D.; et al. Microarray-based survey of CpG islands identifies concurrent hyper- and hypomethylation patterns in tissues derived from patients with breast cancer. Genes Chromosom. Cancer 2006, 45, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Foley, J.E.; Hahn, R.; Zhou, P.; Burgeson, R.E.; Gerecke, D.R.; Gordon, M.K. α1(XX) Collagen, a New Member of the Collagen Subfamily, Fibril-associated Collagens with Interrupted Triple Helices. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 23120–23126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanicolaou, M.; Parker, A.L.; Yam, M.; Filipe, E.C.; Wu, S.Z.; Chitty, J.L.; Wyllie, K.; Tran, E.; Mok, E.; Nadalini, A.; et al. Temporal profiling of the breast tumour microenvi-ronment reveals collagen XII as a driver of metastasis. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaide-Ruggiero, L.; Molina-Hernández, V.; Granados, M.M.; Domínguez, J.M. Main and Minor Types of Collagens in the Artic-ular Cartilage: The Role of Collagens in Repair Tissue Evaluation in Chondral Defects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, Y. Integrated bioinformatics analysis of expression and gene regulation network of COL12A1 in colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 4743–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misawa, K.; Kanazawa, T.; Imai, A.; Endo, S.; Mochizuki, D.; Fukushima, H.; Misawa, Y.; Mineta, H. Prognostic value of type XXII and XXIV collagen mRNA expression in head and neck cancer patients. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 2, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Peptide Type | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Immunogenic peptide | KLH *-CGG-QRAFNKGPDP |

| Selection peptide | QRAFNKGPDP |

| Elongated selection peptide | QRAFNKGPDPG |

| Truncated selection peptide | QRAFNKGPD |

| Non-sense coating and standard peptide | DQAAGGLRQH |

| Assay Parameter | Result |

|---|---|

| ELISA format | Competitive CLIA |

| Curve fit model | 4-point logistic curve fit |

| Detection range: LLOQ-ULOQ | 0.65–120.00 (ng/mL) |

| LLOB | 0.41 ng/mL |

| Mean Slope | 1.022 |

| Mean IC25 | 1.20 ng/mL |

| Mean IC50 | 3.62 ng/mL |

| Mean IC75 | 10.61 ng/mL |

| Inter-assay CV% (Range) | 5.23–26.01 |

| Intra-assay CV% (Range) | 2.35–5.93 |

| Dilution recovery (1 + 1, Range) | 94.6–100.8% |

| Accepted maximum freeze–thaw cycles | Five freeze–thaw cycles (92–113%) |

| Interference hemoglobin, low/high | 94%/102% |

| Interference lipid, low/high | 103%/102% |

| Interference biotin | >100 ng/mL |

| Cancer (n = 259) | Healthy (n = 73) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, male, n (%) | 152 (58.7%) | 32 (43.8%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| - Missing | 29 | |

| - Black | 6 (13.6%) | |

| - Caucasian | 259 (100.0%) | 28 (63.6%) |

| - Hispanic | 10 (22.7%) | |

| Age, Mean (SD) | 59.4 (10.7) | 48.2 (9.3) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| - bladder cancer | 19 (7.3%) | |

| - breast cancer | 20 (7.7%) | |

| - colorectal cancer | 20 (7.7%) | |

| - head and neck cancer | 20 (7.7%) | |

| - kidney cancer | 20 (7.7%) | |

| - lung cancer | 60 (23.2%) | |

| - melanoma | 20 (7.7%) | |

| - ovarian cancer | 20 (7.7%) | |

| - pancreatic cancer | 20 (7.7%) | |

| - prostate cancer | 20 (7.7%) | |

| - renal cancer | 20 (7.7%) | |

| Diagnosis | AUC | Threshold | Sensitivity | Specificity | ppv | npv | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder | 0.79 [0.67–0.90] | 11.9 | 0.95 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 0.97 | 0.0001 |

| Breast | 0.73 [0.61–0.85] | 14.7 | 0.85 | 0.63 | 0.39 | 0.94 | 0.002 |

| Colorectal | 0.84 [0.76–0.93] | 17.1 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.5 | 0.95 | <0.0001 |

| Gastric | 0.70 [0.57–0.83] | 11.8 | 0.85 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.93 | 0.006 |

| Head and neck | 0.78 [0.67–0.88] | 14.2 | 0.90 | 0.62 | 0.39 | 0.96 | 0.0002 |

| Kidney | 0.90 [0.85–0.96] | 16.0 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 0.53 | 1.00 | <0.0001 |

| Lung | 0.86 [0.80–0.92] | 16.1 | 0.87 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.87 | 0. 0001 |

| Melanoma | 0.69 [0.56–0.82] | 15.7 | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.38 | 0.88 | 0.008 |

| Ovarian | 0.83 [0.73–0.93] | 16.6 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.5 | 0.95 | <0.0001 |

| Pancreatic | 0.79 [0.68–0.90] | 24.9 | 0.55 | 0.89 | 0.58 | 0.88 | <0.0001 |

| Prostate | 0.58 [0.42–0.74] | 13.1 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.31 | 0.88 | 0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Port, H.; He, Y.; Karsdal, M.A.; Madsen, E.A.; Bay-Jensen, A.-C.; Willumsen, N.; Holm Nielsen, S. Type IX Collagen Turnover Is Altered in Patients with Solid Tumors. Cancers 2024, 16, 2035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112035

Port H, He Y, Karsdal MA, Madsen EA, Bay-Jensen A-C, Willumsen N, Holm Nielsen S. Type IX Collagen Turnover Is Altered in Patients with Solid Tumors. Cancers. 2024; 16(11):2035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112035

Chicago/Turabian StylePort, Helena, Yi He, Morten A. Karsdal, Emilie A. Madsen, Anne-Christine Bay-Jensen, Nicholas Willumsen, and Signe Holm Nielsen. 2024. "Type IX Collagen Turnover Is Altered in Patients with Solid Tumors" Cancers 16, no. 11: 2035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112035

APA StylePort, H., He, Y., Karsdal, M. A., Madsen, E. A., Bay-Jensen, A.-C., Willumsen, N., & Holm Nielsen, S. (2024). Type IX Collagen Turnover Is Altered in Patients with Solid Tumors. Cancers, 16(11), 2035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16112035