Household Income Is Associated with Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain among Cancer Survivors: A Cross-Sectional Study Using NHIS Data

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

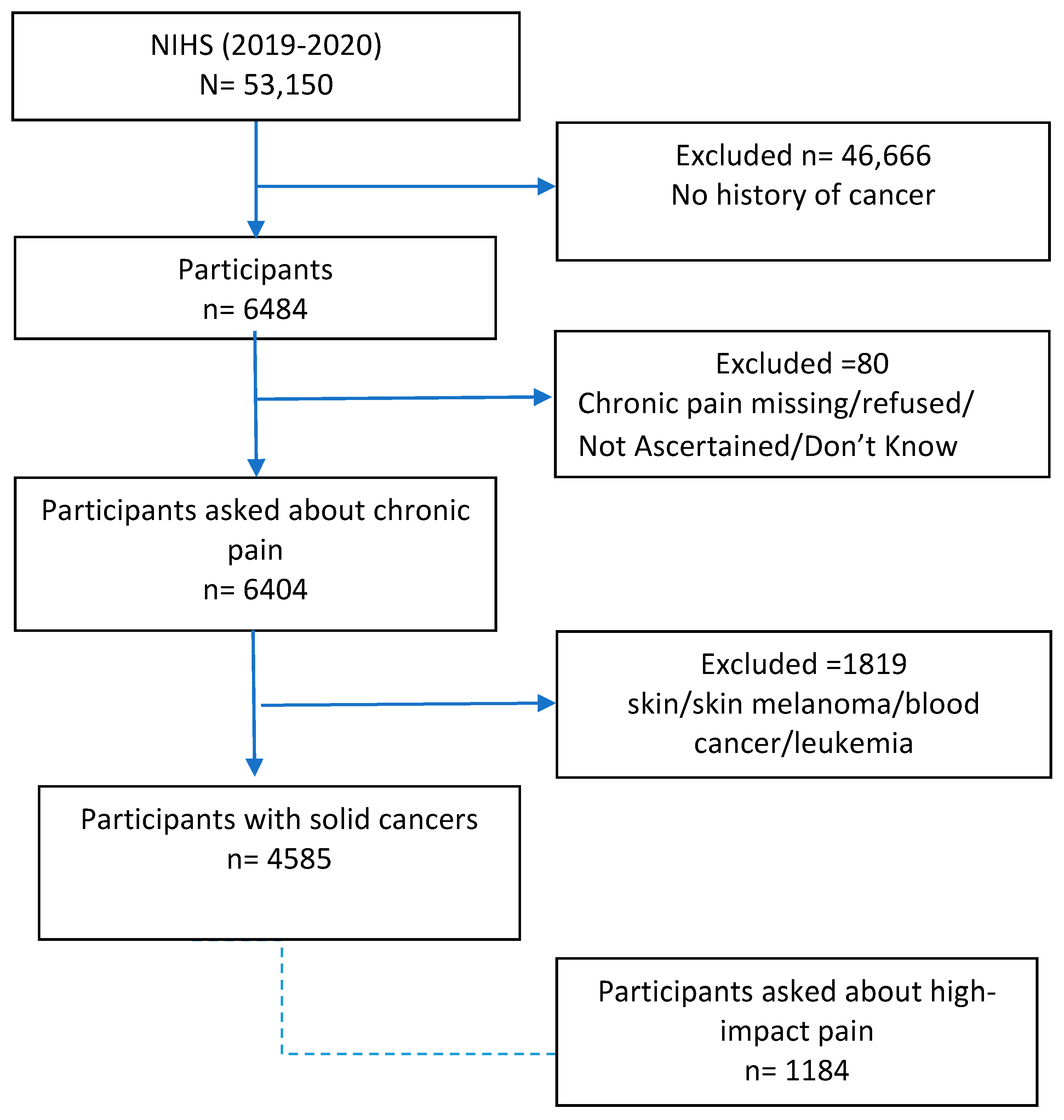

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Diagnoses of Solid Cancers

2.3. Ratio of Household Income to Federal Poverty Level

2.4. Outcomes

2.4.1. Chronic Pain

2.4.2. Pain Management Techniques Other than Over-the-Counter Medications

Opioids

Alternative Pain Management Methods

2.5. Covariates

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Participants and Design

3.2. Household Income and Chronic Pain

3.3. Opioid Use

3.4. Non-Opioid Pain Management

4. Discussion

4.1. Disparity in Cancer Pain

4.2. Socioeconomic Disparities in Cancer Pain Management

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.M.; Arora, N.K.; Bradley, C.J.; Brauer, E.R.; Graves, D.L.; Lunsford, N.B.; McCabe, M.S.; Nasso, S.F.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Rowland, J.H. Long-term survivorship care after cancer treatment-summary of a 2017 National Cancer Policy Forum Workshop. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 1300–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champion, V.L.; Wagner, L.I.; Monahan, P.O.; Daggy, J.; Smith, L.; Cohee, A.; Ziner, K.W.; Haase, J.E.; Miller, K.D.; Pradhan, K. Comparison of younger and older breast cancer survivors and age-matched controls on specific and overall quality of life domains. Cancer 2014, 120, 2237–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Theobald, D.; Wu, J.; Loza, J.K.; Carpenter, J.S.; Tu, W. The association of depression and pain with health-related quality of life, disability, and health care use in cancer patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2010, 40, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, C.R.; Hart-Johnson, T.; Loeffler, D.R. Cancer-related chronic pain: Examining quality of life in diverse cancer survivors. Cancer 2011, 117, 1994–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rikard, S.M.; Strahan, A.E.; Schmit, K.M.; Guy, G.P., Jr. Chronic Pain Among Adults—United States, 2019–2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, O.-K.; Chee, W.; Im, E.-O. The influence of social structure on cancer pain and quality of life. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2017, 39, 1547–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestvina, C.M.; Zullig, L.L.; Rushing, C.; Chino, F.; Samsa, G.P.; Altomare, I.; Tulsky, J.; Ubel, P.; Schrag, D.; Nicolla, J. Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J. Oncol. Pract. 2014, 10, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, K.M.; Evans, S.B.; McCorkle, R.; DiGiovanna, M.P.; Pusztai, L.; Sanft, T.; Hofstatter, E.W.; Killelea, B.K.; Knobf, M.T.; Lannin, D.R. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J. Oncol. Pract. 2014, 10, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, S.; Blough, D.; Kirchhoff, A.; Kreizenbeck, K.; Fedorenko, C.; Snell, K.; Newcomb, P.; Hollingworth, W.; Overstreet, K. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grol-Prokopczyk, H. Use and opinions of prescription opioids among older American adults: Sociodemographic predictors. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2019, 74, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation; Centers for Disease Control & Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017.

- Duca, L.M.; Helmick, C.G.; Barbour, K.E.; Nahin, R.L.; Von Korff, M.; Murphy, L.B.; Theis, K.; Guglielmo, D.; Dahlhamer, J.; Porter, L.; et al. A Review of Potential National Chronic Pain Surveillance Systems in the United States. J. Pain 2022, 23, 1492–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeffermann, D. The use of sampling weights for survey data analysis. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 1996, 5, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.F.; Osazuwa-Peters, O.L.; Des Marais, A.; Merlin, J.S.; Check, D.K. Substance Use Disorders Among US Adult Cancer Survivors. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haenen, V.; Evenepoel, M.; De Baerdemaecker, T.; Meeus, M.; Devoogdt, N.; Morlion, B.; Dams, L.; Van Dijck, S.; Van der Gucht, E.; De Vrieze, T.; et al. Pain prevalence and characteristics in survivors of solid cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 31, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prior HHS Poverty Guidelines and Federal Register References; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. Available online: http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/figures-fed-reg.shtml (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Prior HHS Poverty Guidelines and Federal Register References. Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines/prior-hhs-poverty-guidelines-federal-register-references (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Cox-Martin, E.; Anderson-Mellies, A.; Borges, V.; Bradley, C. Chronic pain, health-related quality of life, and employment in working-age cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 14, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Sidlow, R.; Han, X. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain in cancer survivors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1224–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, N.N.; Sher, D.J.; Butler, S.S.; Xu, X.; Ahn, C.; Aizer, A.A.; Mahal, B.A. Prevalence of chronic pain among cancer survivors in the United States, 2010–2017. Cancer 2019, 125, 4310–4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fillingim, R.B. Individual differences in pain: Understanding the mosaic that makes pain personal. Pain 2017, 158 (Suppl. S1), S11–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.; Paice, J.A.; Wallace, M. Pain and opioids in cancer care: Benefits, risks, and alternatives. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2017, 37, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, S.H.; Throckmorton, D.C. US Food and Drug Administration Efforts to Support Pain Management and Opioid Access to Patients with Cancer. J. Oncol. Prat. 2019, 15, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fereydooni, S.; Lorenz, K.; Azarfar, A.; Luckett, T.; Phillips, J.L.; Becker, W.; Giannitrapani, K. Identifying provider, patient and practice factors that shape long-term opioid prescribing for cancer pain: A qualitative study of American and Australian providers. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e082033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, E.-O.; Chee, W.; Guevara, E.; Liu, Y.; Lim, H.-J.; Tsai, H.-M.; Clark, M.; Bender, M.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, Y.H. Gender and ethnic differences in cancer pain experience: A multiethnic survey in the United States. Nurs. Res. 2007, 56, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitzthum, L.K.; Nalawade, V.; Riviere, P.; Sumner, W.; Nelson, T.; Mell, L.K.; Furnish, T.; Rose, B.; Martínez, M.E.; Murphy, J.D. Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic discrepancies in opioid prescriptions among older patients with cancer. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2021, 17, e703–e713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheetham, A.; Picco, L.; Barnett, A.; Lubman, D.I.; Nielsen, S. The Impact of Stigma on People with Opioid Use Disorder, Opioid Treatment, and Policy. Subst. Abus. Rehabil. 2022, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowell, D.; Haegerich, T.M.; Chou, R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA 2016, 315, 1624–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häuser, W.; Schug, S.; Furlan, A.D. The opioid epidemic and national guidelines for opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain: A perspective from different continents. Pain Rep. 2017, 2, e599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallon, M.; Dierberger, K.; Leng, M.; Hall, P.S.; Allende, S.; Sabar, R.; Verastegui, E.; Gordon, D.; Grant, L.; Lee, R.; et al. An international, open-label, randomised trial comparing a two-step approach versus the standard three-step approach of the WHO analgesic ladder in patients with cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 1296–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltoni, M.; Scarpi, E.; Modonesi, C.; Passardi, A.; Calpona, S.; Turriziani, A.; Speranza, R.; Tassinari, D.; Magnani, P.; Saccani, D. A validation study of the WHO analgesic ladder: A two-step vs three-step strategy. Support. Care Cancer 2005, 13, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zech, D.F.; Grond, S.; Lynch, J.; Hertel, D.; Lehmann, K.A. Validation of World Health Organization Guidelines for cancer pain relief: A 10-year prospective study. Pain 1995, 63, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghabeesh, S.H.; Bashayreh, I.H.; Saifan, A.R.; Rayan, A.; Alshraifeen, A.A. Barriers to effective pain management in cancer patients from the perspective of patients and family caregivers: A qualitative study. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2020, 21, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, M.T.; de Moor, J.S.; Yabroff, K.R. Impact of pain on employment and financial outcomes among cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, C.; Harding, R.; Teo, I.; Ozdemir, S.; Koh, G.C.; Neo, P.; Lee, L.H.; Kanesvaran, R.; Finkelstein, E.; COMPASS Study team. Financial difficulties are associated with greater total pain and suffering among patients with advanced cancer: Results from the COMPASS study. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 3781–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, P.; Patel, N.; Lu, Y.C.; Walker, R.; Younis, M. The Financial Burden of Cancer on Families in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, M.T.; Roberto, A.; Corli, O.; Deandrea, S.; Bandieri, E.; Cavuto, S.; Apolone, G. Quality of cancer pain management: An update of a systematic review of undertreatment of patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 4149–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poço Gonçalves, J.; Veiga, D.; Araújo, A. Chronic pain, functionality and quality of life in cancer survivors. Br. J. Pain 2021, 15, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, L.M.; Rachet, B.; Coleman, M. Origins of socio-economic inequalities in cancer survival: A review. Ann. Oncol. 2006, 17, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Overall | <200% FPL | 200–399% FPL | ≥400% FPL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted n, weighted % | n = 4585 (%) | n = 1333 (%) | n = 1372 (%) | n = 1880 (%) | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 18–44 | 320 | 9.5 | 121 | 13.4 | 87 | 8.0 | 112 | 7.6 |

| 45–64 | 1285 | 32.7 | 362 | 30.2 | 317 | 27.6 | 606 | 38.2 |

| ≥65 | 2976 | 57.7 | 850 | 556.3 | 966 | 64.2 | 1160 | 54.1 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 2762 | 58.9 | 908 | 66.1 | 816 | 57.3 | 1038 | 54.9 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 280 | 7.0 | 141 | 14.9 | 76 | 8.0 | 63 | 4.3 |

| NH White | 3777 | 82.9 | 949 | 65.4 | 1157 | 80.8 | 1671 | 86.1 |

| NH Black | 354 | 6.4 | 167 | 13.4 | 98 | 8.5 | 89 | 5.1 |

| NH Asian | 76 | 1.8 | 17 | 1.9 | 21 | 1.4 | 38 | 3.4 |

| Other | 98 | 1.9 | 59 | 4.5 | 20 | 1.3 | 19 | 1.1 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Not married | 2212 | 33.8 | 899 | 53.2 | 688 | 36.3 | 625 | 22.6 |

| Married/living with partner | 2321 | 65.2 | 413 | 45.1 | 668 | 62.5 | 1240 | 76.5 |

| Education | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 354 | 9.5 | 243 | 23.8 | 86 | 9.7 | 25 | 1.9 |

| High school or GED | 1241 | 28.4 | 493 | 38.6 | 457 | 36.4 | 291 | 18.5 |

| Some college or more | 2963 | 61.7 | 583 | 36.5 | 825 | 53.6 | 1555 | 79.2 |

| Insurance | ||||||||

| Covered | 4449 | 96.0 | 1260 | 90.7 | 1334 | 96.4 | 1855 | 98.4 |

| Not covered | 132 | 3.9 | 72 | 9.2 | 36 | 3.4 | 24 | 1.5 |

| BMI | ||||||||

| Underweight | 66 | 1.4 | 21 | 1.5 | 27 | 2.3 | 18 | 1.0 |

| Healthy weight | 1390 | 29.0 | 346 | 24.3 | 409 | 29.0 | 635 | 31.8 |

| Overweight | 1613 | 35.7 | 452 | 33.2 | 471 | 34.5 | 690 | 35.9 |

| Obese | 1412 | 31.6 | 489 | 39.1 | 420 | 31.0 | 503 | 29.2 |

| Urbanicity | ||||||||

| Large central metro | 1089 | 23.8 | 305 | 24.9 | 284 | 27.5 | 500 | 27.5 |

| Large fringe metro | 1126 | 25.4 | 229 | 18.0 | 334 | 30.2 | 563 | 30.2 |

| Medium and small metro | 1515 | 32.3 | 461 | 31.4 | 476 | 30.4 | 578 | 30.4 |

| Non-metropolitan | 855 | 18.5 | 338 | 25.7 | 278 | 11.9 | 239 | 11.9 |

| Smoking history | ||||||||

| Never | 2287 | 51.6 | 573 | 45.7 | 662 | 46.4 | 1052 | 57.1 |

| Current | 524 | 11.8 | 267 | 21.0 | 158 | 14.0 | 99 | 6.2 |

| Former | 1736 | 35.9 | 475 | 31.7 | 540 | 38.8 | 721 | 36.3 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Diabetes (Yes) | 787 | 17.8 | 311 | 23.1 | 258 | 20.7 | 218 | 11.9 |

| Hypertension (Yes) | 2586 | 54.9 | 876 | 63.6 | 814 | 58.3 | 896 | 46.2 |

| Arthritis (Yes) | 2136 | 44.0 | 725 | 51.4 | 675 | 46.7 | 736 | 36.6 |

| Depression (Yes) | 987 | 21.4 | 425 | 29.4 | 275 | 20.6 | 287 | 16.4 |

| Anxiety (Yes) | 805 | 17.6 | 344 | 24.9 | 219 | 16.5 | 242 | 13.2 |

| Number of cancers (>1) | 1028 | 20.8 | 287 | 19.7 | 301 | 20.9 | 440 | 21.4 |

| Cancer type # | ||||||||

| Colorectal | 364 | 7.6 | 133 | 10.3 | 116 | 7.4 | 115 | 5.7 |

| Breast (females) | 1236 | 42.0 | 369 | 37.6 | 367 | 42.9 | 500 | 45.2 |

| Lung | 188 | 4.0 | 85 | 6.0 | 54 | 3.9 | 49 | 2.7 |

| Prostate (males) | 806 | 43.0 | 153 | 34.5 | 243 | 42.9 | 410 | 45.5 |

| Head and neck | 89 | 1.9 | 27 | 1.9 | 28 | 2.3 | 34 | 1.6 |

| Melanoma | 365 | 7.7 | 68 | 4.8 | 113 | 8.1 | 184 | 9.6 |

| Bladder | 177 | 3.5 | 42 | 2.6 | 65 | 4.5 | 70 | 3.5 |

| Gynecologic (females) | 646 | 26.1 | 276 | 33.7 | 180 | 24.4 | 190 | 20.7 |

| Hepatobiliary | 80 | 1.7 | 23 | 1.6 | 27 | 2.1 | 30 | 1.6 |

| Digestive | 60 | 1.4 | 25 | 2.0 | 14 | 1.1 | 21 | 1.2 |

| n/N | Weighted % | aOR and 95% CI * | aOR and 95% CI † | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic pain (n = 4585) | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

| <200% FPL | 650/1333 | 47.3 | 2.00 (1.59–2.52) | 1.60 (1.25–2.05) |

| 200–399% FPL | 481/1372 | 36.6 | 1.38 (1.13–1.69) | 1.18 (0.96–1.46) |

| ≥400% FPL | 518/1880 | 28.1 | REF | REF |

| p-trend < 0.0028 | p-trend < 0.0005 | |||

| High-impact chronic pain interferes with life and work; physical limitations (n = 1184) | ||||

| <200% FPL | 256/476 | 54.3 | 1.86 (1.17–2.94) | 1.73 (1.09–2.74) |

| 200–399% FPL | 129/338 | 39.9 | 1.34 (0.88–2.04) | 1.24 (0.80–1.90) |

| ≥400% FPL | 117/370 | 33.5 | REF | REF |

| p-trend = 0.0082 | p-trend = 0.0203 | |||

| Variables | Overall n = 4585 | <200% FPL n = 1333 (%) | 200–399% FPL n = 1372 (%) | ≥400% FPL n = 1880 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioid use | ||||

| Opioid use in the past 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 1002 (22.4) | 383 (28.3) | 271 (21.3) | 348 (19.0) |

| No | 3183 (67.0) | 862 (62.6) | 987 (69.0) | 1334 (68.7) |

| Not asked/refused/missing | 400 (10.6) | 88 (9.1) | 114 (9.7) | 198 (12.3) |

| Opioid use in the past 3 months | ||||

| Yes | 620 (13.7) | 260 (18.9) | 175 (13.8) | 185 (9.8) |

| No | 380 (8.7) | 123 (9.4) | 95 (7.3) | 162 (9.1) |

| Not asked/refused/missing | 3585 (77.6) | 950 (71.7) | 1102 (78.8) | 1533 (81.1) |

| Acute opioid use in the past 3 months | ||||

| Yes | 383 (8.2) | 155 (10.4) | 108 (8.5) | 120 (6.5) |

| No | 237 (5.4) | 105 (8.5) | 17 (5.3) | 15 (3.4) |

| Not asked/refused/missing | 3965 (86.3) | 1073 (81.1) | 1197 (86.2) | 1695 (90.2) |

| Non-opioid methods | ||||

| Physical therapy | ||||

| Yes | 557 (11.6) | 164 (11.5) | 160 (10.5) | 233 (12.5) |

| No | 2902 (64.1) | 943 (70.4) | 864 (65.3) | 1095 (58.5) |

| Not asked/refused/missing | 1126 (24.3) | 226 (18.1) | 348 (24.1) | 552 (29.0) |

| Chiropractic care | ||||

| Yes | 289 (6.2) | 70 (5.4) | 89 (6.3) | 130 (6.8) |

| No | 3168 (69.4) | 1035 (76.3) | 936 (69.6) | 1197 (64.2) |

| Not asked/refused/missing | 1128 (24.4) | 228 (18.3) | 347 (24.1) | 553 (29.0) |

| Talk, cognitive–behavioral therapy | ||||

| Yes | 81 (1.7) | 31 (2.1) | 25 (2.0) | 25 (1.3) |

| No | 3375 (73.9) | 1074 (79.6) | 998 (73.8) | 1303 (69.8) |

| Not asked/refused/missing | 1129 (24.4) | 228 (18.3) | 349 (24.2) | 552 (30.0) |

| Yoga, tai chi, or qi gong | ||||

| Yes | 279 (5.5) | 72 (5.1) | 64 (4.1) | 143 (6.8) |

| No | 3179 (70.1) | 1034 (76.6) | 960 (71.8) | 1185 (64.3) |

| Not asked/refused/missing | 1127 (24.4) | 227 (18.2) | 348 (24.1) | 552 (30.0) |

| Massage | ||||

| Yes | 446 (9.9) | 99 (7.6) | 127 (9.3) | 220 (11.9) |

| No | 3011 (65.7) | 1006 (74.1) | 897 (66.6) | 1108 (59.1) |

| Not asked/refused/missing | 1128 (24.4) | 228 (18.3) | 348 (24.1) | 552 (29.0) |

| Meditation | ||||

| Yes | 483 (10.0) | 162 (11.9) | 140 (9.6) | 181 (9.1) |

| No | 2973 (65.5) | 943 (69.8) | 883 (66.2) | 1147 (61.9) |

| Not asked/refused/missing | 1129 (24.4) | 228 (18.3) | 349 (24.2) | 552 (29.0) |

| Other | ||||

| Yes | 961 (19.7) | 311 (20.7) | 271 (19.5) | 379 (19.2) |

| No | 2496 (55.9) | 794 (61.1) | 753 (56.4) | 949 (51.9) |

| Not asked/refused/missing | 1128 (24.4) | 228 (18.2) | 348 (24.1) | 552 (29.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valvi, N.; Tamargo, J.A.; Braithwaite, D.; Fillingim, R.B.; Karanth, S.D. Household Income Is Associated with Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain among Cancer Survivors: A Cross-Sectional Study Using NHIS Data. Cancers 2024, 16, 2847. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16162847

Valvi N, Tamargo JA, Braithwaite D, Fillingim RB, Karanth SD. Household Income Is Associated with Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain among Cancer Survivors: A Cross-Sectional Study Using NHIS Data. Cancers. 2024; 16(16):2847. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16162847

Chicago/Turabian StyleValvi, Nimish, Javier A. Tamargo, Dejana Braithwaite, Roger B. Fillingim, and Shama D. Karanth. 2024. "Household Income Is Associated with Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain among Cancer Survivors: A Cross-Sectional Study Using NHIS Data" Cancers 16, no. 16: 2847. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16162847

APA StyleValvi, N., Tamargo, J. A., Braithwaite, D., Fillingim, R. B., & Karanth, S. D. (2024). Household Income Is Associated with Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain among Cancer Survivors: A Cross-Sectional Study Using NHIS Data. Cancers, 16(16), 2847. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16162847