An Evaluation of Serum miRNA in Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

- Population: Adult (≥18 years old) patients with RCC.

- Intervention: Measurement of circulating or cell-free miRNA in blood samples of patients with RCC (exclusion: snRNA, ccRNA, exosomal RNA, lncRNA).

- Comparator/Control: Healthy subjects or patients with RCC after surgery.

- Outcome (main): Different expression of miRNA in blood samples between patients with RCC and healthy subjects through diagnostic accuracy measurements.

- Pediatric patients and adult patients with benign renal tumors.

- Measurement of RNA other than circulating or cell-free miRNA in blood samples of patients with RCC (snRNA, ccRNA, exosomal RNA, lncRNA…).

- Reviews and meta-analyses, abstracts, letters and meeting reports.

3. Results

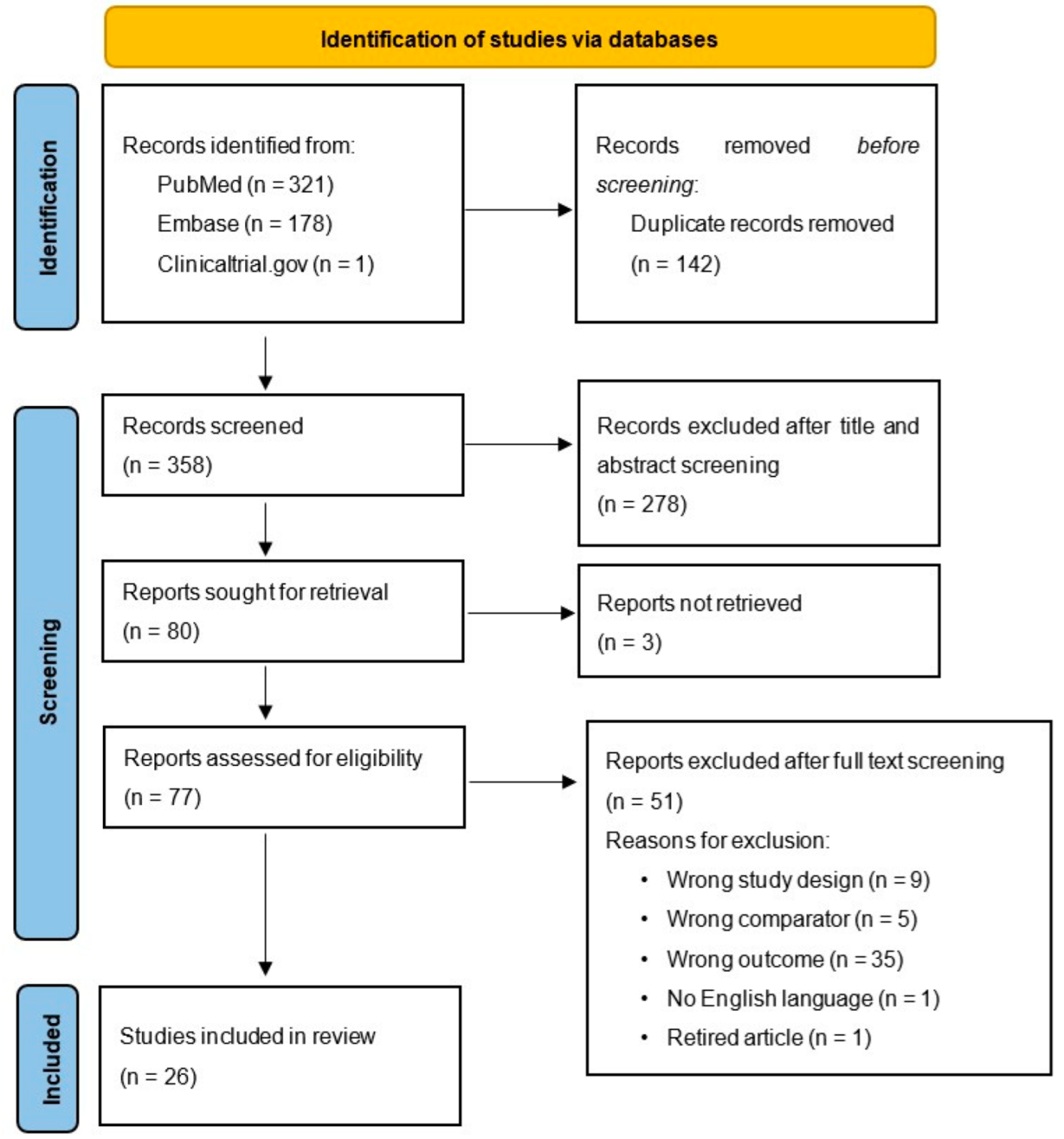

3.1. Study Selection

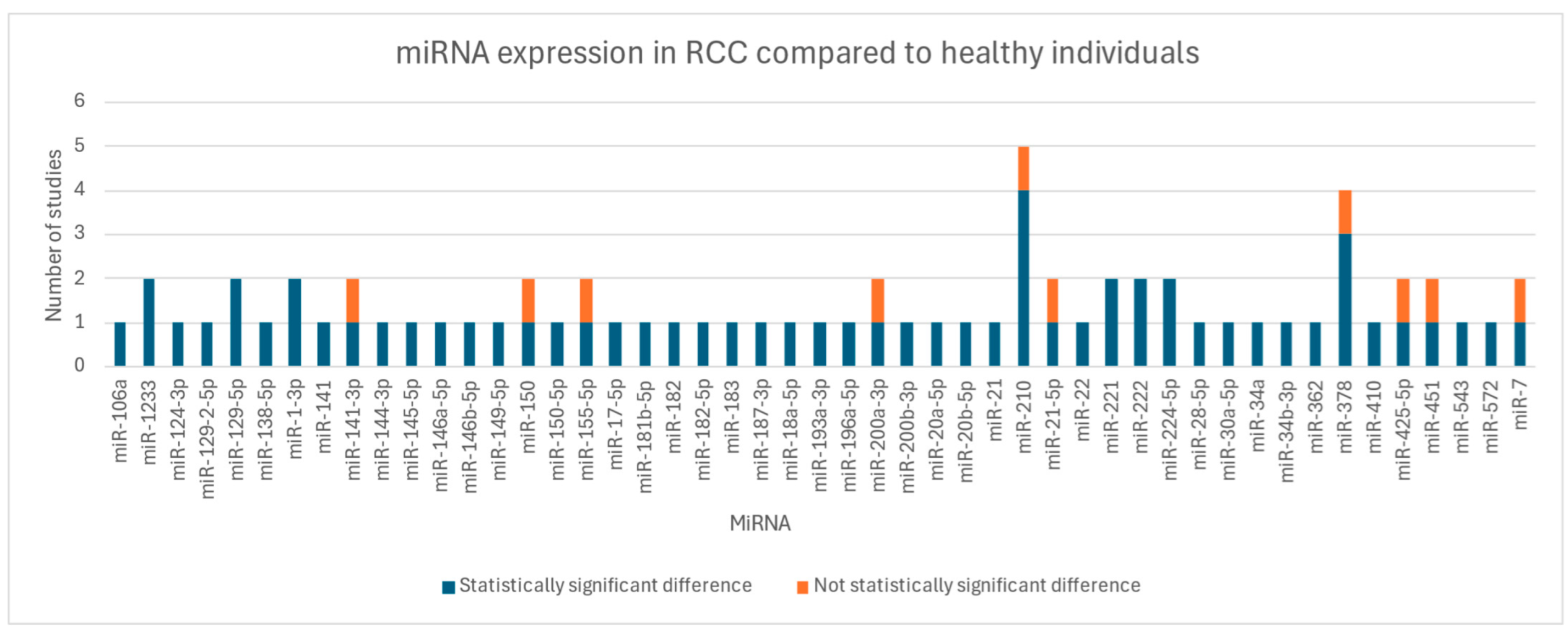

3.2. Key Findings

3.3. Risk of Bias and Certainty Assessment for Included Studies

4. Discussion

- Validation in larger cohorts: The diagnostic utility of promising miRNAs and multi-miRNA panels must be validated in larger, independent cohorts to ensure their generalizability and clinical applicability.

- Standardization of methods: It is essential to develop standardized protocols for sample collection and data reporting to improve comparability between studies and increase the reliability of results.

- An international consensus on laboratory investigations for miRNA extraction, profiling, stabilization and quantitative analysis could provide a clearer interpretation of results.

- The institution of a global updated library of miRNA could help researchers explore not-yet-investigated miRNAs and consolidate international findings.

- Exploration of prognostic and therapeutic value: Further studies are needed to clarify the role of miRNAs in predicting disease progression, therapeutic response and patient outcomes.

- Integration of multi-miRNA panels: Combining multiple miRNAs into diagnostic panels may enhance accuracy and reliability, particularly for early detection and differentiation of RCC subtypes.

- Integration with other biomarkers: Integration of miRNAs with other biomarkers, such as protein or genetic biomarkers, could improve diagnostic precision.

- Assessment of confounding factors: Identifying and controlling for potential confounding factors is essential to minimize bias risk.

- Technological advances: Innovations in miRNA detection, including next-generation sequencing and machine learning-based analysis, could improve sensitivity and specificity, making miRNA-based diagnostics more viable in routine clinical settings.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferlay, J.; Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Rosso, S.; Coebergh, J.W.W.; Comber, H.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur. J. Cancer 2013, 49, 1374–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Poma, J.; Trilla-Fuertes, L.; López-Camacho, E.; Zapater-Moros, A.; López-Vacas, R.; Lumbreras-Herrera, M.I.; Pertejo-Fernandez, A.; Fresno-Vara, J.Á.; Espinosa-Arranz, E.; Gámez-Pozo, A.; et al. MiRNAs in renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 24, 2055–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, R.; Ding, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.Y.; Zhang, C.; Gu, W.J.; et al. Urinary-derived extracellular vesicle microRNAs as non-invasive diagnostic biomarkers for early-stage renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Chim. Acta 2024, 552, 117672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Supplementary Material to: PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, M.; McKenzie, J.E.; Sowden, A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Brennan, S.E.; Ellis, S.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Ryan, R.; Shepperd, S.; Thomas, J.; et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. BMJ 2020, 368, l6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guadagni, L.; Cochetti, G.; Paladini, A.; Russo, M.; Pastore, F.; Saqer, E.; Vitale, A.; La Mura, R.; Mangione, P.; Gioè, M.; et al. Evaluation of Serum miRNA in Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42024550709 (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Mendeley Ltd. Mendeley Desktop. 2021. Available online: https://www.mendeley.com/ (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel. 2019. Available online: https://office.microsoft.com/excel (accessed on 24 September 2018).

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Morgan, R.L.; Rooney, A.A.; Taylor, K.W.; Thayer, K.A.; Silva, R.A.; Lemeris, C.; Akl, E.A.; Bateson, T.F.; Berkman, N.D.; et al. A tool to assess risk of bias in non-randomized follow-up studies of exposure effects (ROBINS-E). Environ. Int. 2024, 186, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schünemann, H.; Brożek, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A. GRADE Handbook for Grading Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group. 2013. Available online: https://guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook (accessed on 1 October 2013).

- Chanudet, E.; Wozniak, M.B.; Bouaoun, L.; Byrnes, G.; Mukeriya, A.; Zaridze, D.; Brennan, P.; Muller, D.C.; Scelo, G. Large-scale genome-wide screening of circulating microRNAs in clear cell renal cell carcinoma reveals specific signatures in late-stage disease. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 1730–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Peng, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, K.; Huang, G.; Lai, Y. Identification of a four-microRNA panel in serum for screening renal cell carcinoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2021, 227, 153625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorko, M.; Stanik, M.; Iliev, R.; Redova-Lojova, M.; Machackova, T.; Svoboda, M.; Pacik, D.; Dolezel, J.; Slaby, O. Combination of MiR-378 and MiR-210 serum levels enables sensitive detection of renal cell carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 23382–23389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, S.; Wulfken, L.M.; Holdenrieder, S.; Moritz, R.; Ohlmann, C.H.; Jung, V.; Becker, F.; Herrmann, E.; Walgenbach-Brünagel, G.; von Ruecker, A.; et al. Analysis of serum microRNAs (miR-26a-2*, miR-191, miR-337-3p and miR-378) as potential biomarkers in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012, 36, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinemann, F.G.; Tolkach, Y.; Deng, M.; Schmidt, D.; Perner, S.; Kristiansen, G.; Müller, S.C.; Ellinger, J. Serum miR-122-5p and miR-206 expression: Non-invasive prognostic biomarkers for renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Epigenet. 2018, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Peng, X.; Liu, K.; Zhao, L.; Lai, Y.; et al. A Three-microRNA Panel in Serum: Serving as a Potential Diagnostic Biomarker for Renal Cell Carcinoma. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2020, 26, 2425–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Peng, X.; Liu, K.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Lai, Y.; Ni, L. Combination of tumor suppressor miR-20b-5p, miR-30a-5p, and miR-196a-5p as a serum diagnostic panel for renal cell carcinoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2020, 216, 153152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamoto, H.; Kanda, Y.; Sejima, T.; Osaki, M.; Okada, F.; Takenaka, A. Serum miR-210 as a potential biomarker of early clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 44, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogirou, C.; Ellinger, J.; Kristiansen, G.; Hatzichristodoulou, G.; Kübler, H.; Kneitz, B.; Busch, J.; Fendler, A. Identification of miR-21-5p and miR-210-3p serum levels as biomarkers for patients with papillary renal cell carcinoma: A multicenter analysis. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2020, 9, 1314–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Sha, Y.; Zhang, X. Migration and Invasion in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2017, 10, 153152. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Lu, C.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Huang, G.; Wen, Z.; Li, H.; Tao, L.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; et al. A Four-MicroRNA Panel in Serum as a Potential Biomarker for Screening Renal Cell Carcinoma. Front. Genet. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Chen, W.; Lu, C.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Huang, G.; Wen, Z.; Li, H.; Tao, L.; Hu, Y.; et al. A four-microRNA panel in serum may serve as potential biomarker for renal cell carcinoma diagnosis. Front. Oncol. 2023, 12, 1076303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.Y.; Zhang, H.; Du, S.M.; Li, J.; Wen, X.H. Expression of microRNA-210 in tissue and serum of renal carcinoma patients and its effect on renal carcinoma cell proliferation, apoptosis, and invasion. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15, 15017746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Hu, X.; Ge, Q.; Xiao, J.; Ginting, C.N. Expression of miR-410 in peripheral blood of patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma and its effect on proliferation and invasion of Caki-2 cells. Jalan Sekip Simpang Sikanbing Dist. 2021, 26, 2059–2066. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, N.; Ruan, A.M.; Qiu, B.; Bao, L.; Xu, Y.C.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, R.L.; Zhang, S.T.; Xu, G.H.; Ruan, H.L.; et al. miR-144-3p as a novel plasma diagnostic biomarker for clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2017, 35, e7–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redova, M.; Poprach, A.; Nekvindova, J.; Iliev, R.; Radova, L.; Lakomy, R.; Svoboda, M.; Vyzula, R.; Slaby, O. Circulating miR-378 and miR-451 in serum are potential biomarkers for renal cell carcinoma. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, A.L.; Ferreira, M.; Silva, J.; Gomes, M.; Dias, F.; Santos, J.I.; Maurício, J.; Lobo, F.; Medeiros, R. Higher circulating expression levels of miR-221 associated with poor overall survival in renal cell carcinoma patients. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 4057–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, A.L.; Dias, F.; Ferreira, M.; Gomes, M.; Santos, J.I.; Lobo, F.; Maurício, J.; Machado, J.C.; Medeiros, R. Combined influence of EGF+61G>A and TGFB+869T>C functional polymorphisms in renal cell carcinoma progression and overall survival: The link to plasma circulating MiR-7 and MiR-221/222 Expression. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0103258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusong, H.; Maolakuerban, N.; Guan, J.; Rexiati, M.; Wang, W.G.; Azhati, B.; Nuerrula, Y.; Wang, Y.J. Functional analysis of serum microRNAs miR-21 and miR-106a in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 2017, 18, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hu, J.; Lu, M.; Gu, H.; Zhou, X.; Chen, X.; Zen, K.; Zhang, C.Y.; Zhang, T.; Ge, J.; et al. A panel of five serum miRNAs as a potential diagnostic tool for early-stage renal cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, H.; Cui, L.; Feng, J.; Fan, Q. MicroRNA-182 suppresses clear cell renal cell carcinoma migration and invasion by targeting IGF1R. Neoplasma 2016, 63, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Lu, C.; Sun, C.; Chen, W.; Ge, Z.; Ni, L.; et al. A serum panel of three microRNAs may serve as possible biomarkers for kidney renal clear cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulfken, L.M.; Moritz, R.; Ohlmann, C.; Holdenrieder, S.; Jung, V.; Becker, F.; Herrmann, E.; Walgenbach-Brünagel, G.; von Ruecker, A.; Müller, S.C.; et al. MicroRNAs in renal cell carcinoma: Diagnostic implications of serum miR-1233 levels. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Khandelwal, M.; Seth, A.; Saini, A.K.; Dogra, P.N.; Sharma, A. Serum microRNA Expression Profiling: Potential Diagnostic Implications of a Panel of Serum microRNAs for Clear Cell Renal Cell Cancer. Urology 2017, 104, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Di, W.; Dong, Y.; Lu, G.; Yu, J.; Li, J.; Li, P. High serum miR-183 level is associated with poor responsiveness of renal cancer to natural killer cells. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 9245–9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, A.; Li, G.; Péoc’h, M.; Genin, C.; Gigante, M. Serum miR-210 as a novel biomarker for molecular diagnosis of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2013, 94, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campi, R.; Stewart, G.D.; Staehler, M.; Dabestani, S.; Kuczyk, M.A.; Shuch, B.M.; Finelli, A.; Bex, A.; Ljungberg, B.; Capitanio, U. Novel Liquid Biomarkers and Innovative Imaging for Kidney Cancer Diagnosis: What Can Be Implemented in Our Practice Today? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2021, 4, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tito, C.; De Falco, E.; Rosa, P.; Iaiza, A.; Fazi, F.; Petrozza, V.; Calogero, A. Circulating micrornas from the molecular mechanisms to clinical biomarkers: A focus on the clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Genes 2021, 12, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Getz, G.; Miska, E.A.; Alvarez-Saavedra, E.; Lamb, J.; Peck, D.; Sweet-Cordero, A.; Ebert, B.L.; Mak, R.H.; Ferrando, A.A.; et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature 2005, 435, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lánczky, A.; Nagy, Á.; Bottai, G.; Munkácsy, G.; Szabó, A.; Santarpia, L.; Győrffy, B. miRpower: A web-tool to validate survival-associated miRNAs utilizing expression data from 2178 breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 160, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella, R.; Pizzocaro, E.; Bannone, E.; Gualtieri, P.; Frank, G.; Giardino, A.; Frigerio, I.; Pastorelli, D.; Gruttadauria, S.; Mazzali, G.; et al. Nutritional Intervention for the Elderly during Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study (First Author, Publication Year, Country) | Number of Participants (Cases; Controls) | miRNA | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chanudet E. (2017, France) [12] | 194 (94 ccRCC; 100 controls) | 288 miRNAs evaluated | miR451 + miR26b# discriminate cases from controls (AUC = 0.64); 60 miRNAs significantly differentially expressed in late-stage ccRCC compared with controls (miR-451 ↓ in late-stage ccRCC vs. controls); no significant differences in miRNA between early-stage ccRCC cases and controls. As prognostic factors, miR-150 and miR-587 ↑ in RCC survivors (q = 0.004 and q = 0.03, respectively) |

| Chen X. (2021, China) [13] | 241 (123 RCC; 118 healthy) | 30 miRNAs evaluated; 6 miRNAs (miR-145-5p, miR-146a-5p, miR-150-5p, miR-21-5p, miR-17-5p and miR-20a-5p) went through validation phase | miR-150-5p (p < 0.001) and miR-21-5p (p < 0.001) ↑ in RCC compared to controls; miR-145-5p (p < 0.001), miR-146a-5p (p < 0.001), miR-20a-5p (p < 0.001) and miR-17-5p (p = 0.004) ↓ in RCC compared to controls |

| Fedorko M. (2015, Czech Republic) [14] | 295 (195 RCC; 100 healthy) | miR-378 and miR-210 | miR-378 (p < 0.0001) and miR-210 (p < 0.0001) ↑ in RCC compared to controls; miR-378 (p < 0.0001) and miR-210 (p < 0.0001) ↓ in patients 3 months after nephrectomy compared to RCC pre-surgery |

| Hauser S. (2012, Germany) [15] | 240 (117 RCC, 14 benign renal tumor; 109 healthy) | miR-26a-2*, miR-191, miR-337-3p and miR-378 | miR-378 equally expressed in RCC, benign renal tumor and controls |

| Heinemann F. G. (2018, Germany) [16] | 169 (86 ccRCC, 55 benign renal tumor; 28 healthy) | miR-122-5p, miR-206, miR-193a-5p | miR-122-5p (p = 0.002), miR-206 (p < 0.001) ↓ in ccRCC compared to controls; miR-193a-5p not statistically different in RCC, benign renal tumor and controls (all p > 0.3) |

| Huang G. (June 2020, China) [17] | 256 (126 RCC; 130 healthy) | 30 miRNAs evaluated; 8 miRNAs selected for validation (miR-149-5p, miR-224-5p, miR-34b-3p, miR-129-2-5p, miR-142-3p, miR-182-5p, miR-671-5p, miR-625-3p) | miR-224-5p (p < 0.05) and miR-149-5p (p < 0.05) ↑ in RCC; miR-34b-3p (p < 0.05), miR-129-2-3p (p < 0.05) and miR-182-5p (p < 0.05) ↓ in RCC; no statistical difference reported for miR-142-3p, miR-625-3p and miR-671-5p |

| Huang G. (July 2020, China) [18] | 220 (110 RCC, 110 healthy) | miR-20b-5p, miR-30a-5p and miR-196a-5p | miR-20b-5p (p < 0.001), miR-30a-5p (p < 0.001) ↓ in RCC compared to controls; miR-196a-5p (p < 0.001) ↑ in RCC compared to controls |

| Iwamoto H. (2014, Japan) [19] | 57 (34 ccRCC; 23 healthy) | miR-210 | miR-210↑ in ccRCC compared to controls (p = 0.001) |

| Kalogirou C. (2020, Germany) [20] | 100 (34 pRCC type 1, 33 pRCC type 2; 33 healthy) | let-7b, miR-10a-3p, miR-10b-5p, miR-21-5p, miR-126-3p, miR-127-3p, miR-142-3p, miR-155-5p, miR-199a-3p, miR-210-3p and miR-425-5p | No different expression of any serum miRNAs in pRCC compared to controls |

| Li M. (2017, China) [21] | 278 (139 RCC; 139 healthy) | miR-22 | miR-22 (p < 0.001) ↓ in RCC compared to controls; miR-22 (p < 0.001) ↑ in RCC post-nephrectomy compared RCC pre-surgery |

| Li R. (2022, China) [22] | 220 (108 RCC; 112 healthy) | 12 miRNAs evaluated; 6 miRNAs (miR-18a-5p, miR-138-5p, miR-141-3p, miR-181b-5p, miR-200a-3p and miR-363-3p) went through validation phase | Panel of 4 combined miRNAs (miR-18a-5p, miR-181b-5p, miR-138-5p and miR-141-3p) selected for RCC detection (AUC = 0.908) |

| Li R. (2023, China) [23] | 224 (112 RCC; 112 healthy) | 12 miRNAs evaluated; 6 miRNAs (miR-1-3p, miR-124-3p, miR-129-5p, miR-155-5p, miR-200b-3p and miR-224-5p) went through validation phase | miR-155-5p (p = 0.001) miR-224-5p (p < 0.001) ↑ in RCC compared to controls; miR-1-3p (p = 0.001), miR-124-3p (p = 0.003), miR-129-5p (p < 0.001) and miR-200b-3p (p < 0.001) ↓ in RCC compared to controls |

| Liu T.Y. (2016, China) [24] | 64 (32 RCC; 32 healthy) | miR-210 | miR-210 (p < 0.001) ↑ in RCC compared to controls |

| Liu Z. (2021, China) [25] | 226 (113 ccRCC; 113 healthy) | miR-410 | miR-410 (p < 0.001) ↑ in ccRCC compared to controls |

| Lou N. (2016, China) [26] | 276 (106 ccRCC, 28 angiomyolipomas, 19 nccRCC; 123 healthy) | 1523 miRNAs evaluated | miR-144-3p ↑ in ccRCC compared to angiomyolipomas and controls (both p < 0.0001); miR-144-3p ↓ in ccRCC post-nephrectomy compared to ccRCC pre-surgery (p = 7.02 × 10−5) |

| Redova M. (2012, Czech Republic) [27] | 152 (105 ccRCC; 47 healthy) | 667 miRNAs evaluated; 3 miRNAs (miR-378, miR-150, miR-451) selected for validation | miR-378 (p = 0.0003) ↑ in ccRCC compared to controls; miR-150 (p = 0.222); miR-451 (p < 0.0001) ↓ in ccRCC compared to controls |

| Teixeira A. L. (2014, Portugal) [28] | 77 (43 RCC; 34 healthy) | miR-221, miR-222 | miR-221 (p = 0.028) and miR-222 (0.044) ↑ in RCC compared to controls |

| Teixeira A. L. (2015, Portugal) [29] | 577 (133 RCC; 443 healthy) | miR-7, miR-221, miR-222 | miR-7 (p < 0.001), miR-221 (p = 0.035), miR-222 (p = 0.042) ↑ in RCC compared to controls |

| Tusong H. (2016, China) [30] | 60 (30 RCC; 30 healthy) | miR-21 and miR-106a | miR-21 (p < 0.0001) and miR-106a (p < 0.0001) ↑ in RCC compared to controls; miR-21 (p < 0.0001) and miR-106a (p < 0.0001) ↓ in RCC 1 month after nephrectomy compared to RCC pre-surgery |

| Wang C. (2015, China) [31] | 264 (132 ccRCC; 132 healthy) | 754 miRNAs evaluated; 20 miRNAs went through validation phase | miR-193a-3p (p < 0.0001), miR-362 (p < 0.0001), miR-572 (p < 0.0001), miR-425-5p (p = 0.0480) and miR- 543 (p = 0.0405) ↑ in ccRCC compared to controls; miR-28-5p (p = 0.0010) and miR-378 (p = 0.0033) ↓ in ccRCC compared to controls; miR-382, miR-208b, miR-337-5p, miR-1300, miR-7, miR-194, miR-324-5p, miR-886-3p, miR-1225-3p, miR-663b, miR-1247, miR-520c-3p, miR-1208 no statistical difference between ccRCC and controls (p > 0.05) |

| Wang X. (2016, China) [32] | 67 (57 ccRCC; 10 healthy) | miR-182 | miR-182 (p < 0.05) ↓ in ccRCC compared to controls |

| Wen Z. (2024, China) [33] | 224 (112 RCC; 112 healthy) | 12 miRNAs evaluated; 8 miRNAs (miR-1-3p, miR-129-5p, miR-141-3p, miR-146b-5p, miR-187-3p, miR-200b-5p, miR-200a-3p and miR-486-5p) went through validation phase | miR-1-3p (p < 0.001), miR-129-5p (p < 0.001), miR-187-3p (p < 0.001) and miR-200a-3p (p < 0.001) ↓ in RCC compared to controls; miR-146b-5p (p < 0.01) ↑ in RCC compared to controls; miR-141-3p, miR-200b-5p and miR-486-5p no statistical difference between RCC and controls (p > 0.05) |

| Wulfken L. M. (2011, Germany) [34] | 265 (108 ccRCC, 10 pRCC, 3 chRCC, 2 sRCC; 129 healthy; 3 angiomyolipoma; 10 oncocytoma) | 318 miRNAs evaluated; 7 miRNAs (miR-106b*, miR-1233, miR-1290, miR-210, miR-7-1*, miR-320b and miR-93) went through verification; miR-1233 went through validation | miR-1233 (p = 0.044) ↑ in RCC compared to controls |

| Yadav S. (2017, India) [35] | 45 (30 RCC; 15 healthy) | miR-34a, miR-141, miR-200c, miR-1233, miR-21-2 | miR-34a (p < 0.001) and miR-141 (p = 0.003) ↓ in RCC compared to controls; miR-1233 (p < 0.001) ↑ in RCC compared to controls; miR-200c (p = 0.086) and miR-21-2 (p = 0.331) not differentially expressed in RCC and controls |

| Zhang Q. (2015, China) [36] | 101 (82 ccRCC; 19 healthy) | miR-183 | miR-183 (p < 0.01) ↑ in ccRCC compared to controls |

| Zhao A. (2013, France) [37] | 110 (68 RCC; 42 controls) | miR-210 | miR-210 (p < 0.0001) ↑ in ccRCC compared to controls; miR-210 ↓ in ccRCC after nephrectomy compared to ccRCC pre-surgery (p = 0.001) |

| Risk of Bias (ROBINS-E) | Certainty Assessment (GRADE) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (First Author, Publication Year) | Domain 1 | Domain 2 | Domain 3 | Domain 4 | Domain 5 | Domain 6 | Domain 7 | Overall Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Quality |

| Chanudet E. (2017) [12] | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Not serious | Not serious | Serious 1 | Moderate |

| Chen X. (2021) [13] | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | High |

| Fedorko M. (2015) [14] | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | High |

| Hauser S. (2012) [15] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns 3 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| Heinemann F. G. (2018) [16] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns 4 | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Serious 1 | Low |

| Huang G. (June 2020) [17] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| Huang G. (July 2020) [18] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| Iwamoto H. (2014) [19] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Serious 1 | Low |

| Kalogirou C. (2020) [20] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Serious 1 | Low |

| Li M. (2017) [21] | Some concerns 2 | High-risk 5 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | High-risk | Not serious | Serious 6 | Not serious | Very low |

| Li R. (2022) [22] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| Li R. (2023) [23] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| Liu T.Y. (2016) [24] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Serious 1 | Low |

| Liu Z. (2021) [25] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| Lou N. (2017) [26] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | High-risk 7 | High-risk | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Low |

| Redova M. (2012) [27] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Serious 1 | Low |

| Teixeira A. L. (2014) [28] | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Not serious | Not serious | Serious 1 | Moderate |

| Teixeira A. L. (2015) [29] | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | High |

| Tusong H. (2017) [30] | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Not serious | Not serious | Serious 1 | Moderate |

| Wang C. (2015) [31] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| Wang X. (2016) [32] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Very serious 8 | Very low |

| Wen Z. (2024) [33] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| Wulfken L. M. (2011) [34] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Moderate |

| Yadav S. (2017) [35] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Serious 1 | Low |

| Zhang Q. (2015) [36] | Some concerns 2 | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Some concerns 9 | Some concerns | Not serious | Not serious | Serious 1 | Low |

| Zhao A. (2013) [37] | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Low-risk | Not serious | Not serious | Serious 1 | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cochetti, G.; Guadagni, L.; Paladini, A.; Russo, M.; La Mura, R.; Vitale, A.; Saqer, E.; Mangione, P.; Esposito, R.; Gioè, M.; et al. An Evaluation of Serum miRNA in Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17050816

Cochetti G, Guadagni L, Paladini A, Russo M, La Mura R, Vitale A, Saqer E, Mangione P, Esposito R, Gioè M, et al. An Evaluation of Serum miRNA in Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Cancers. 2025; 17(5):816. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17050816

Chicago/Turabian StyleCochetti, Giovanni, Liliana Guadagni, Alessio Paladini, Miriam Russo, Raffaele La Mura, Andrea Vitale, Eleonora Saqer, Paolo Mangione, Riccardo Esposito, Manfredi Gioè, and et al. 2025. "An Evaluation of Serum miRNA in Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review" Cancers 17, no. 5: 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17050816

APA StyleCochetti, G., Guadagni, L., Paladini, A., Russo, M., La Mura, R., Vitale, A., Saqer, E., Mangione, P., Esposito, R., Gioè, M., Pastore, F., De Angelis, L., Ricci, F., Vannuccini, G., & Mearini, E. (2025). An Evaluation of Serum miRNA in Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Cancers, 17(5), 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17050816