Pre- and Postnatal Exposures to Residential Pesticides and Survival of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics

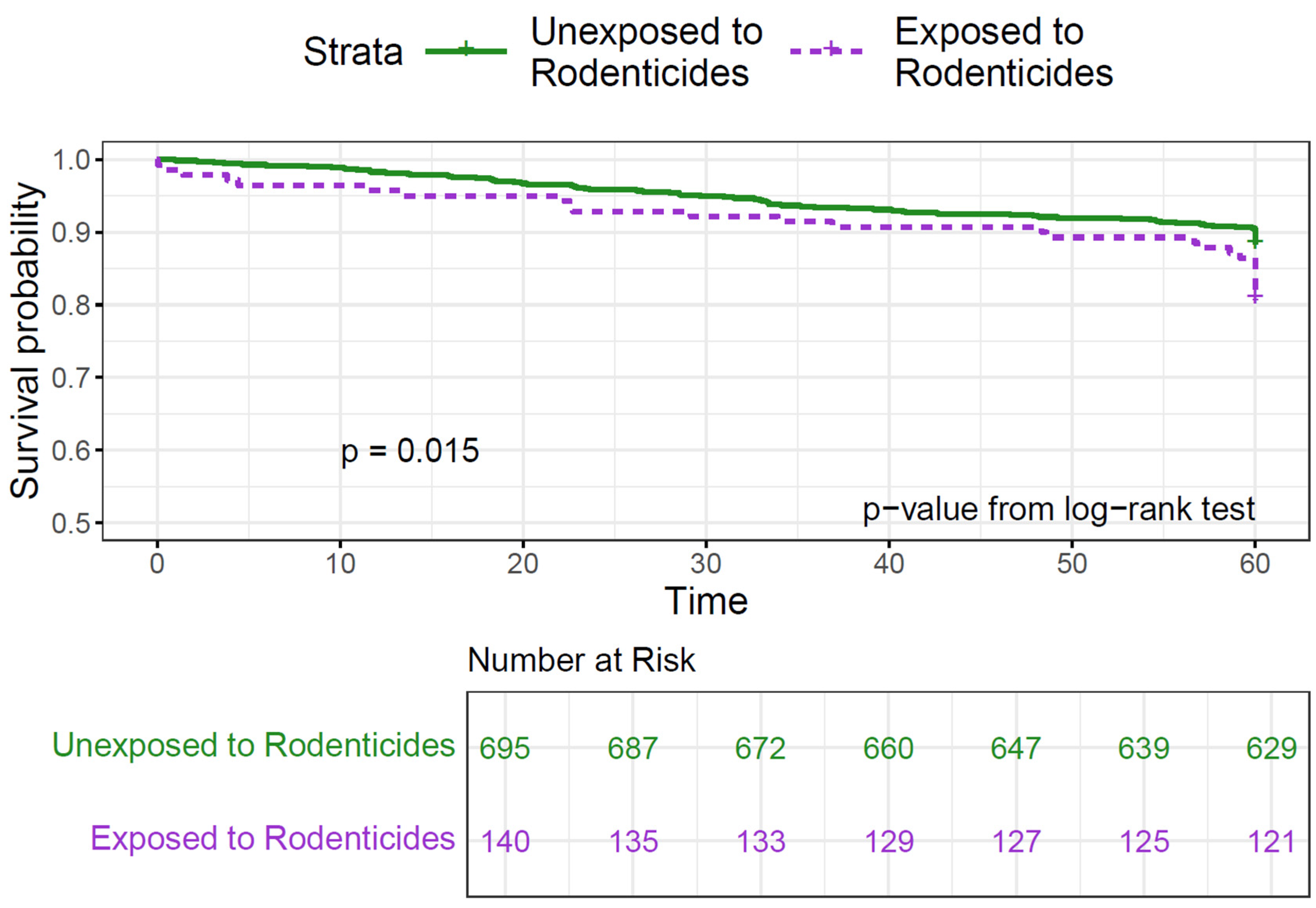

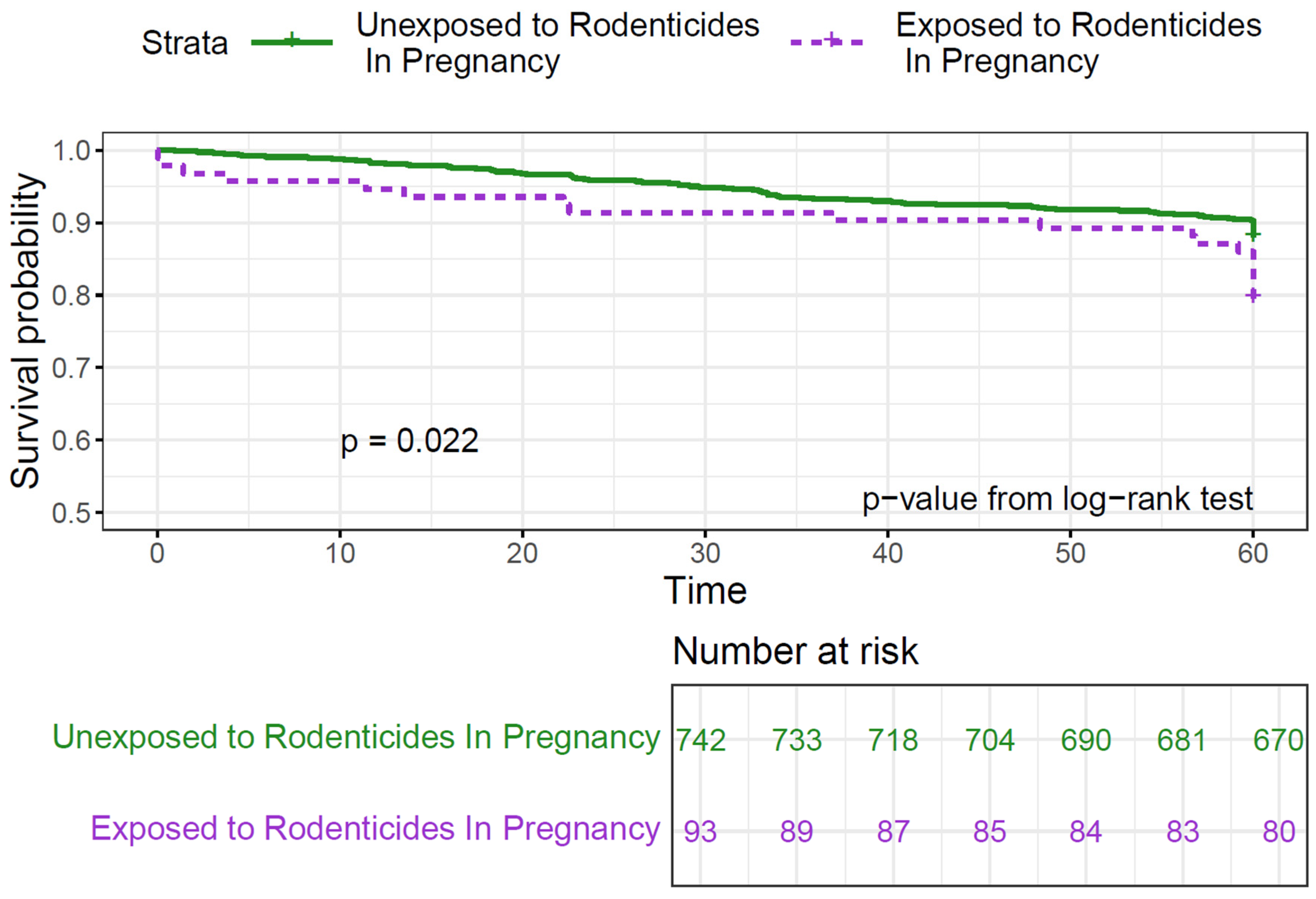

3.2. Bivariate Analyses

3.3. Multivariate Analyses

3.4. Effect Modification

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Biological Effects of Pesticides

4.3. Rodenticides: Prevalence and Potential Health Risks

4.4. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALL | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| CCLS | California Childhood Leukemia Study |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DAG | Directed Acyclic Graph |

| HR | Hazards Ratio |

| NCI | National Cancer Institute |

| Ref | Reference |

| SES | Socioeconomic Status |

References

- SEER: Cancer Stat Facts: Childhood Leukemia (Ages 0–19). Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/childleuk.html (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Hernández, A.F.; Menéndez, P. Linking Pesticide Exposure with Pediatric Leukemia: Potential Underlying Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Onyije, F.M.; Olsson, A.; Baaken, D.; Erdmann, F.; Stanulla, M.; Wollschläger, D.; Schüz, J. Environmental Risk Factors for Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: An Umbrella Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chang, C.-H.; Tao, L.; Lu, C. Residential Exposure to Pesticide During Childhood and Childhood Cancers: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics 2015, 136, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karalexi, M.A.; Tagkas, C.F.; Markozannes, G.; Tseretopoulou, X.; Hernández, A.F.; Schüz, J.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Petridou, E.T.; Tzoulaki, I.; et al. Exposure to Pesticides and Childhood Leukemia Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 285, 117376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.S.; Ritz, B.; Yu, F.; Cockburn, M.; Heck, J.E. Prenatal Pesticide Exposure and Childhood Leukemia—A California Statewide Case-Control Study. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 226, 113486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, H.D.; Fritschi, L.; Infante-Rivard, C.; Glass, D.C.; Miligi, L.; Dockerty, J.D.; Lightfoot, T.; Clavel, J.; Roman, E.; Spector, L.G.; et al. Parental Occupational Pesticide Exposure and the Risk of Childhood Leukemia in the Offspring: Findings from the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 135, 2157–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.C. Windows of Exposure to Pesticides for Increased Risk of Childhood Leukemia. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2006, 88, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, H.D.; Infante-Rivard, C.; Metayer, C.; Clavel, J.; Lightfoot, T.; Kaatsch, P.; Roman, E.; Magnani, C.; Spector, L.G.; Petridou, E.; et al. Home Pesticide Exposures and Risk of Childhood Leukemia: Findings from the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 137, 2644–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Van Maele-Fabry, G.; Gamet-Payrastre, L.; Lison, D. Household Exposure to Pesticides and Risk of Leukemia in Children and Adolescents: Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metayer, C.; Zhang, L.; Wiemels, J.L.; Bartley, K.; Schiffman, J.; Ma, X.; Aldrich, M.C.; Chang, J.S.; Selvin, S.; Fu, C.H.; et al. Tobacco Smoke Exposure and the Risk of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic and Myeloid Leukemias by Cytogenetic Subtype. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2013, 22, 1600–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, G.; Pogribny, I.P.; Guyton, K.Z.; Rusyn, I. Epigenetic Alterations Induced by Genotoxic Occupational and Environmental Human Chemical Carcinogens: A Systematic Literature Review. Mutat. Res. Mutat. Res. 2016, 768, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petridou, E.T.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Perlepe, C.; Papathoma, P.; Tsilimidos, G.; Kontogeorgi, E.; Kourti, M.; Baka, M.; Moschovi, M.; Polychronopoulou, S.; et al. Socioeconomic Disparities in Survival from Childhood Leukemia in the United States and Globally: A Meta-Analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, A.L.; Furutani, E.; Ribeiro, K.B.; Rodriguez Galindo, C. Death Within 1 Month of Diagnosis in Childhood Cancer: An Analysis of Risk Factors and Scope of the Problem. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 1320–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kent, E.E.; Sender, L.S.; Largent, J.A.; Anton-Culver, H. Leukemia Survival in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults: Influence of Socioeconomic Status and Other Demographic Factors. Cancer Causes Control CCC 2009, 20, 1409–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon-Hernandez, J.; Jarquin-Yañez, L.; Reyes-Arreguin, L.; Diaz-Padilla, L.A.; Gonzalez-Compean, J.L.; Gonzalez-Montalvo, P.; Rivera-Gomez, R.; Villanueva-Toledo, J.R.; Pech, K.; Arrieta, O.; et al. Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Survival and Spatial Analysis of Socio-Environmental Risks in Mexico. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1236942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárceles-Álvarez, A.; Ortega-García, J.A.; López-Hernández, F.A.; Fuster-Soler, J.L.; Ramis, R.; Kloosterman, N.; Castillo, L.; Sánchez-Solís, M.; Claudio, L.; Ferris-Tortajada, J. Secondhand Smoke: A New and Modifiable Prognostic Factor in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemias. Environ. Res. 2019, 178, 108689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metayer, C.; Morimoto, L.M.; Kang, A.Y.; Sanchez Alvarez, J.; Winestone, L.E. Pre- and Postnatal Exposures to Tobacco Smoking and Survival of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic and Myeloid Leukemias in California, United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2024, 33, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Rivera, L.T.; Sweetser, B.; Fuster-Soler, J.L.; Ramis, R.; López-Hernández, F.A.; Pérez-Martínez, A.; Ortega-García, J.A. Looking Towards 2030: Strengthening the Environmental Health in Childhood-Adolescent Cancer Survivor Programs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.Y.; Hanson, H.A.; Ramsay, J.M.; Kaddas, H.K.; Pope, C.A.; Leiser, C.L.; VanDerslice, J.; Kirchhoff, A.C. Fine Particulate Matter Air Pollution and Mortality among Pediatric, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Patients. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2020, 29, 1929–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.T.; Rathod, R.A.; Rosales, O.; Castellanos, M.I.; Schraw, J.M.; Burgess, E.; Peckham-Gregory, E.C.; Oluyomi, A.O.; Scheurer, M.E.; Hughes, A.E.; et al. Residential Proximity to Oil and Gas Developments and Childhood Cancer Survival. Cancer 2024, 130, cncr.35449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, P.E.; Zhao, J.; Liang, D.; Nogueira, L.M. Ambient Air Pollution and Survival in Childhood Cancer: A Nationwide Survival Analysis. Cancer 2024, 130, 3870–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamure, S.; Carles, C.; Aquereburu, Q.; Quittet, P.; Tchernonog, E.; Paul, F.; Jourdan, E.; Waultier, A.; Defez, C.; Belhadj, I.; et al. Association of Occupational Pesticide Exposure With Immunochemotherapy Response and Survival Among Patients With Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e192093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, C.; McPherson, J.D.; Tuscano, J.; Li, Q.; Parikh-Patel, A.; Vogel, C.F.A.; Cockburn, M.; Keegan, T. Environmental Pesticide Exposure and Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Survival: A Population-Based Study. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment (PDQ®)—Patient Version. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/types/leukemia/patient/child-all-treatment-pdq#_32 (accessed on 21 February 2024).

- Søegaard, S.H.; Andersen, M.M.; Rostgaard, K.; Davidsson, O.B.; Olsen, S.F.; Schmiegelow, K.; Hjalgrim, H. Exclusive Breastfeeding Duration and Risk of Childhood Cancers. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e243115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, B.H.; DeBaun, M.R.; Camitta, B.M.; Shuster, J.J.; Ravindranath, Y.; Pullen, D.J.; Land, V.J.; Mahoney, D.H.; Lauer, S.J.; Murphy, S.B. Racial Differences in the Survival of Childhood B-Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Pediatric Oncology Group Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2023.

- Winestone, L.E.; Yang, J.; Lichtensztajn, D.Y.; Abrahao, R.; Keegan, T.H.; Cheng, I.; Gomez, S.L.; Shariff-Marco, S. Abstract C067: Impact of Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status on Survival among Young Patients with Acute Leukemia in California. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2020, 29, C067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raetz, E.A.; Bhojwani, D.; Devidas, M.; Gore, L.; Rabin, K.R.; Tasian, S.K.; Teachey, D.T.; Loh, M.L. Children’s Oncology Group Blueprint for Research: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2023, 70 (Suppl. S6), e30585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amitay, E.L.; Keinan-Boker, L. Breastfeeding and Childhood Leukemia Incidence: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, e151025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Sun, X.; Zhu, L.; Yan, Q.; Zheng, P.; Mao, Y.; Ye, D. Breastfeeding and the Risk of Childhood Cancer: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.M.; Emeny, R.T.; Bagley, P.J.; Blunt, H.B.; Butow, M.E.; Morgan, A.; Alford-Teaster, J.A.; Titus, L.; Walston, R.R.; Rees, J.R. Causes of Childhood Cancer: A Review of the Recent Literature: Part I-Childhood Factors. Cancers 2024, 16, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, F.E.; Patheal, S.L.; Biondi, A.; Brandalise, S.; Cabrera, M.E.; Chan, L.C.; Chen, Z.; Cimino, G.; Cordoba, J.C.; Gu, L.J.; et al. Transplacental Chemical Exposure and Risk of Infant Leukemia with MLL Gene Fusion. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 2542–2546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Buffler, P.A.; Gunier, R.B.; Dahl, G.; Smith, M.T.; Reinier, K.; Reynolds, P. Critical Windows of Exposure to Household Pesticides and Risk of Childhood Leukemia. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo-de-Oliveira, M.S.; Koifman, S. Brazilian Collaborative Study Group of Infant Acute Leukemia Infant Acute Leukemia and Maternal Exposures during Pregnancy. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2006, 15, 2336–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabarwal, A.; Kumar, K.; Singh, R.P. Hazardous Effects of Chemical Pesticides on Human Health–Cancer and Other Associated Disorders. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 63, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.-H.; Choi, K.-C. Adverse Effects of Pesticides on the Functions of Immune System. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 235, 108789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuneo, A.; Fagioli, F.; Pazzi, I.; Tallarico, A.; Previati, R.; Piva, N.; Carli, M.G.; Balboni, M.; Castoldi, G. Morphologic, Immunologic and Cytogenetic Studies in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Following Occupational Exposure to Pesticides and Organic Solvents. Leuk. Res. 1992, 16, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummin, D.D.; Mowry, J.B.; Beuhler, M.C.; Spyker, D.A.; Rivers, L.J.; Feldman, R.; Brown, K.; Nathaniel, P.T.P.; Bronstein, A.C.; Weber, J.A. 2021 Annual Report of the National Poison Data System© (NPDS) from America’s Poison Centers: 39th Annual Report. Clin. Toxicol. 2022, 60, 1381–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 54678486, Warfarin. 2025. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/warfarin (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- PubChem Annotation Record for, BRODIFACOUM, Source: Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB); National Center for Biotechnology Information: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2025.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Poisoning by an Illegally Imported Chinese Rodenticide Containing Tetramethylenedisulfotetramine—New York City, 2002. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2003, 52, 199–201. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Poisonings Associated with Illegal Use of Aldicarb as a Rodenticide—New York City, 1994–1997. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 1997, 46, 961–963. [Google Scholar]

- Silberhorn, E.M. Bromethalin. In Encyclopedia of Toxicology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 340–342. ISBN 978-0-12-369400-3. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, S.; Fenik, Y.; Vohra, R.; Geller, R.J. Human Bromethalin Exposures Reported to a U.S. Statewide Poison Control System. Clin. Toxicol. 2016, 54, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isackson, B.; Irizarry, L. Rodenticide Toxicity. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Restrictions on Rodenticide Products. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/rodenticides/restrictions-rodenticide-products (accessed on 4 August 2024).

- King, N.; Tran, M.-H. Long-Acting Anticoagulant Rodenticide (Superwarfarin) Poisoning: A Review of Its Historical Development, Epidemiology, and Clinical Management. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2015, 29, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Underwood, E.L.; Sutton, J.; Ellis, I.K.; Qualls, B.; Zamber, J.; Walker, B.N. Prolonged Coagulopathy after Brodifacoum Exposure. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. AJHP 2014, 71, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.T.; Hartzell, J.D.; More, K.; Durning, S.J. Ingestion of Superwarfarin Leading to Coagulopathy: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. MedGenMed Medscape Gen. Med. 2006, 8, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, R.B.; Alakija, P.; de Baca, J.E.; Nolte, K.B. Fatal Brodifacoum Rodenticide Poisoning: Autopsy and Toxicologic Findings. J. Forensic Sci. 1999, 44, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov Aleksandrov, A.; Tucovic, D.; Kulas, J.; Popovic, D.; Kataranovski, D.; Kataranovski, M.; Mirkov, I. Toxicology of Chemical Biocides: Anticoagulant Rodenticides—Beyond Hemostasis Disturbance. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 277, 109841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, T.M.; Alonzo, T.A.; Tasian, S.K.; Kutny, M.A.; Hitzler, J.; Pollard, J.A.; Aplenc, R.; Meshinchi, S.; Kolb, E.A. Children’s Oncology Group’s 2023 Blueprint for Research: Myeloid Neoplasms. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2023, 70 (Suppl. S6), e30584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bona, K.; Brazauskas, R.; He, N.; Lehmann, L.; Abdel-Azim, H.; Ahmed, I.A.; Al-Homsi, A.S.; Aljurf, M.; Arnold, S.D.; Badawy, S.M.; et al. Neighborhood Poverty and Pediatric Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Outcomes: A CIBMTR Analysis. Blood 2021, 137, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Overall n = 837 | Alive n = 729 | Deceased n = 108 |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Sex (assigned at birth) | |||

| Female | 366 (43.7) | 324 (44.4) | 42 (38.9) |

| Male | 471 (56.3) | 405 (55.6) | 66 (61.1) |

| Race and Ethnicity | |||

| Latinx | 396 (47.3) | 340 (46.6) | 56 (51.9) |

| Non-Latinx White | 295 (35.2) | 272 (37.3) | 23 (21.3) |

| Non-Latinx Asian/Pacific Islander | 73 (8.7) | 61 (8.4) | 12 (11.1) |

| Non-Latinx Black | 24 (2.9) | 16 (2.2) | 8 (7.4) |

| Other/Unknown | 49 (5.9) | ||

| Birth Years | |||

| 1982–1989 | 64 (7.6) | 48 (6.6) | 16 (14.8) |

| 1990–1999 | 509 (60.8) | 442 (60.6) | 67 (62.1) |

| 2000–2014 | 264 (31.5) | 239 (32.8) | 25 (23.1) |

| Household Annual Income (USD) | |||

| <15,000 | 131 (15.7) | 112 (15.4) | 19 (17.6) |

| 15,000–29,999 | 149 (17.8) | 123 (16.9) | 26 (24.1) |

| 30,000–44,999 | 130 (15.5) | 112 (15.4) | 18 (16.7) |

| 45,000–59,999 | 122 (14.6) | 102 (14.0) | 20 (18.5) |

| 60,000–74,999 | 63 (7.5) | 57 (7.8) | 6 (5.5) |

| 75,000+ | 242 (28.9) | 223 (30.6) | 19 (17.6) |

| Number of Dependents in the Household | |||

| 1–3 | 184 (22.0) | 155 (21.2) | 29 (26.9) |

| 4–5 | 524 (62.6) | 459 (63.0) | 65 (60.1) |

| 6+ | 129 (15.4) | 115 (15.8) | 14 (13.0) |

| Highest Parental Education Attained | |||

| High School or Lower | 303 (36.2) | 260 (35.7) | 43 (39.8) |

| Some College or More | 533 (63.7) | 468 (64.2) | 65 (60.2) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Age at Diagnosis (years) | |||

| <1 | 27 (3.2) | 13 (1.8) | 14 (13.0) |

| 1–2 | 195 (23.3) | 175 (24.0) | 20 (18.5) |

| 3–6 | 391 (46.7) | 360 (49.4) | 31 (28.7) |

| 7–9 | 103 (12.3) | 86 (11.8) | 17 (15.7) |

| 10–14 | 121 (14.5) | 95 (13.0) | 26 (24.1) |

| NCI Risk Group | |||

| Standard | 561 (67.0) | 509 (69.8) | 52 (48.1) |

| High | 226 (27.0) | 186 (25.5) | 40 (37.0) |

| Infant | 26 (3.1) | 12 (1.7) | 14 (13.0) |

| Unknown | 24 (2.9) | ||

| Birthweight (grams) | |||

| <2500 | 39 (4.7) | 34 (4.7) | 5 (4.6) |

| 2500–4000 | 663 (79.2) | 580 (79.6) | 83 (76.9) |

| >4000 | 135 (16.1) | 115 (15.8) | 20 (18.5) |

| Gestational Age (weeks) | |||

| <36 | 45 (5.4) | 36 (4.9) | 9 (8.3) |

| 36–41 | 608 (72.6) | 535 (73.4) | 73 (67.6) |

| 41+ | 175 (20.9) | 149 (20.4) | 26 (24.1) |

| Unknown | 9 (1.1) | ||

| Breastfeeding | |||

| No | 138 (16.5) | 114 (15.6) | 24 (22.2) |

| Yes | 663 (79.2) | 585 (80.2) | 78 (72.2) |

| Unknown | 36 (4.3) | ||

| Breastfeeding Duration (months) | |||

| 6 or Less | 520 (62.1) | 450 (61.7) | 70 (64.8) |

| More than 6 | 281 (33.6) | 249 (34.2) | 32 (29.6) |

| Unknown | 36 (4.3) | ||

| Exposure | Alive n = 729 | Deceased n = 108 | Model 1—Without SES Adjustment * | Model 2—With SES Adjustment ** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Any Pesticides | |||||||

| No | 62 (8.5) | 5 (4.6) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 667 (91.5) | 103 (95.4) | 0.23 | 2.06 (0.83–5.11) | 0.1 | 2.22 (0.89–5.54) | 0.09 |

| Number of Types Used | |||||||

| 0–2 (Low) | 327 (44.9) | 40 (37.0) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| 3–4 (Medium) | 226 (31.0) | 42 (38.9) | 1.67 (1.07–2.59) | 0.02 | 1.77 (1.14–2.77) | 0.01 | |

| 5–12 (High) | 176 (24.1) | 26 (24.1) | 0.17 | 1.47 (0.88–2.44) | 0.14 | 1.56 (0.93–2.62) | 0.09 |

| Insecticides | |||||||

| No | 110 (15.0) | 15 (13.9) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 619 (84.9) | 93 (86.1) | 0.86 | 1.10 (0.63–1.91) | 0.7 | 1.15 (0.66–2.00) | 0.6 |

| Herbicides | |||||||

| No | 362 (49.7) | 54 (50.0) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 367 (50.3) | 54 (50.0) | 1 | 1.16 (0.78–1.72) | 0.5 | 1.31 (0.87–1.98) | 0.2 |

| Flea Control | |||||||

| No | 419 (57.5) | 64 (59.3) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 310 (42.5) | 44 (40.7) | 0.8 | 1.16 (0.72–1.57) | 0.8 | 1.04 (0.70–1.54) | 0.8 |

| Rodenticides | |||||||

| No | 614 (84.2) | 81 (75.0) | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Yes | 113 (15.5) | 27 (25.0) | 0.02 | 1.75 (1.13–2.72) | 0.01 | 1.69 (1.08–2.64) | 0.02 |

| Unknown (n = 2) | |||||||

| Exposures | Preconception | Pregnancy | Postnatally | 12 Months Before Interview | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Any Pesticides | ||||||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes | 1.02 (0.68–1.52) | >0.90 | 1.60 (1.05–2.42) | 0.03 | 0.84 (0.53–1.35) | 0.5 | 1.35 (0.87–2.09) | 0.2 |

| Insecticides | ||||||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes | 1.00 (0.67–1.48) | >0.90 | 1.45 (0.96–2.17) | 0.08 | 0.81 (0.53–1.25) | 0.3 | 1.13 (0.75–1.71) | 0.6 |

| Herbicides | ||||||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes | 1.22 (0.79–1.88) | 0.4 | 1.50 (0.98–2.29) | 0.06 | 1.10 (0.73–1.65) | 0.7 | 1.26 (0.84–1.90) | 0.3 |

| Flea Control | ||||||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes | 0.90 (0.57–1.43) | 0.7 | 1.05 (0.68–1.64) | 0.8 | 0.83 (0.55–1.26) | 0.4 | 1.11 (0.74–1.68) | 0.6 |

| Rodenticides | ||||||||

| No | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes | 1.49 (0.85–2.63) | 0.2 | 1.91 (1.15–3.16) | 0.01 | 1.46 (0.91–2.33) | 0.1 | 1.60 (0.98–2.61) | 0.06 |

| Exposure | Non-Latinx White | Latinx | Non-Latinx Black + Asian + Others | Interaction p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95%CI) n Total/n Deaths | p-Value | HR (95% CI) n Total/n Deaths | p-Value | HR (95% CI) n Total/n Deaths | p-Value | ||

| Insecticides | 1.02 (0.24–4.41) | >0.90 | 1.41 (0.69–2.9) | 0.3 | 0.70 (0.22–2.26) | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| 265/21 | 317/47 | 130/25 | |||||

| Herbicides | 1.00 (0.41–2.45) | 0.9 | 0.54 (0.88–2.68) | 0.1 | 1.40 (0.59–3.28) | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| 197/15 | 141/23 | 83/16 | |||||

| Flea Control | 0.83 (0.36–1.90) | 0.7 | 1.55 (0.91–2.64) | 0.1 | 0.55 (0.22–1.39) | 0.2 | 0.09 |

| 164/12 | 145/26 | 45/6 | |||||

| Rodenticides | 3.35 (1.42–7.88) | 0.005 | 1.66 (0.91–3.01) | 0.1 | 0.45 (0.10–1.93) | 0.3 | 0.02 |

| 46/9 | 73/16 | 21/2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Desai, S.; Morimoto, L.M.; Kang, A.Y.; Miller, M.D.; Wiemels, J.L.; Winestone, L.E.; Metayer, C. Pre- and Postnatal Exposures to Residential Pesticides and Survival of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancers 2025, 17, 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17060978

Desai S, Morimoto LM, Kang AY, Miller MD, Wiemels JL, Winestone LE, Metayer C. Pre- and Postnatal Exposures to Residential Pesticides and Survival of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancers. 2025; 17(6):978. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17060978

Chicago/Turabian StyleDesai, Seema, Libby M. Morimoto, Alice Y. Kang, Mark D. Miller, Joseph L. Wiemels, Lena E. Winestone, and Catherine Metayer. 2025. "Pre- and Postnatal Exposures to Residential Pesticides and Survival of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia" Cancers 17, no. 6: 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17060978

APA StyleDesai, S., Morimoto, L. M., Kang, A. Y., Miller, M. D., Wiemels, J. L., Winestone, L. E., & Metayer, C. (2025). Pre- and Postnatal Exposures to Residential Pesticides and Survival of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancers, 17(6), 978. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17060978