The Power of Requests in a Redistribution Game: An Experimental Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Game

3. Experimental Design

- (R1)

- “The rule of the restaurant is that each waiter can choose how much they wish to put in the common pot.”

- (R2)

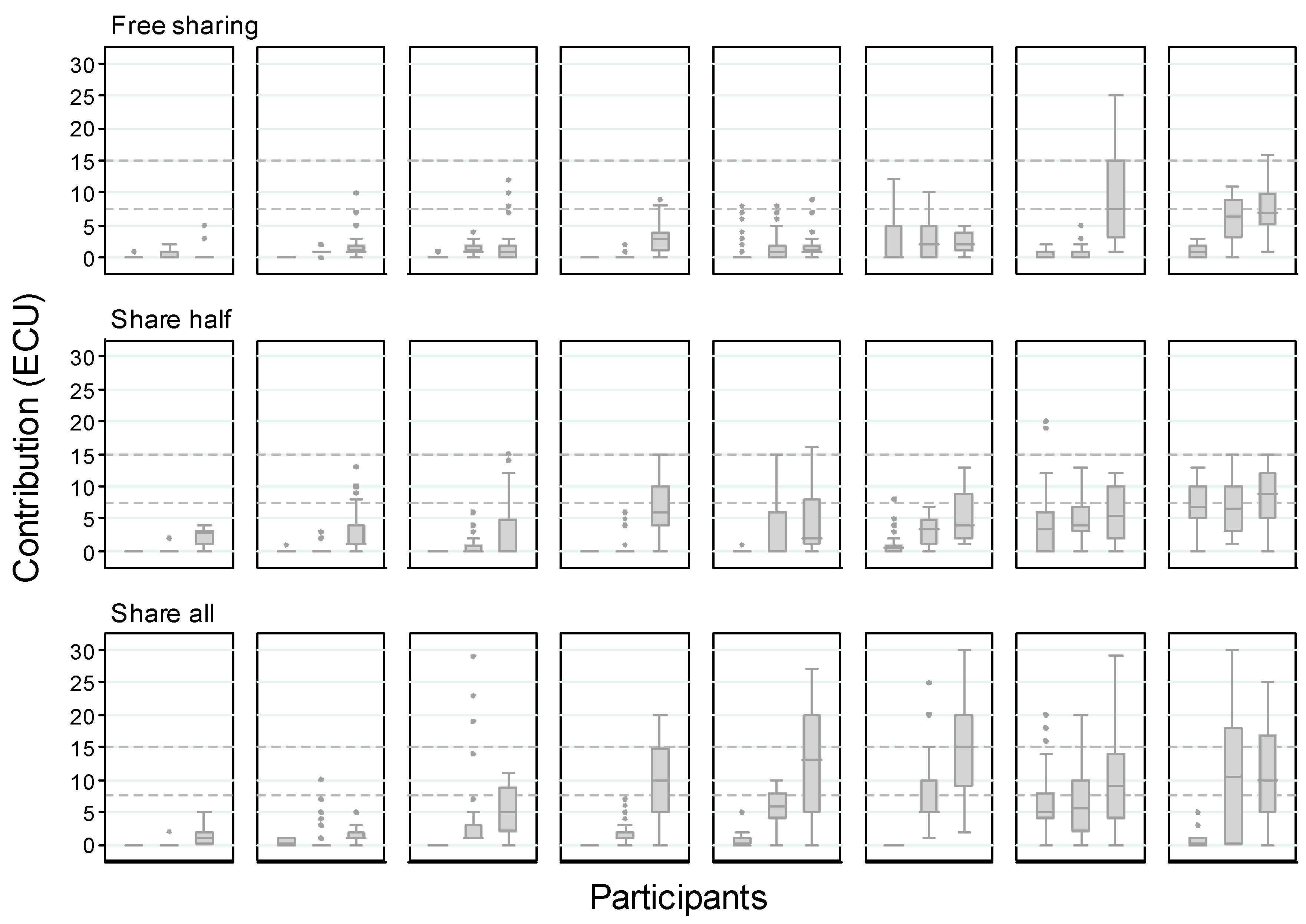

- “The rule of the restaurant is that each waiter puts at least half of their tips in the common pot.”

- (R3)

- “The rule of the restaurant is that each waiter puts all their tips in the common pot.”

4. Results

4.1. Mean Contributions Across Subjects Over Time

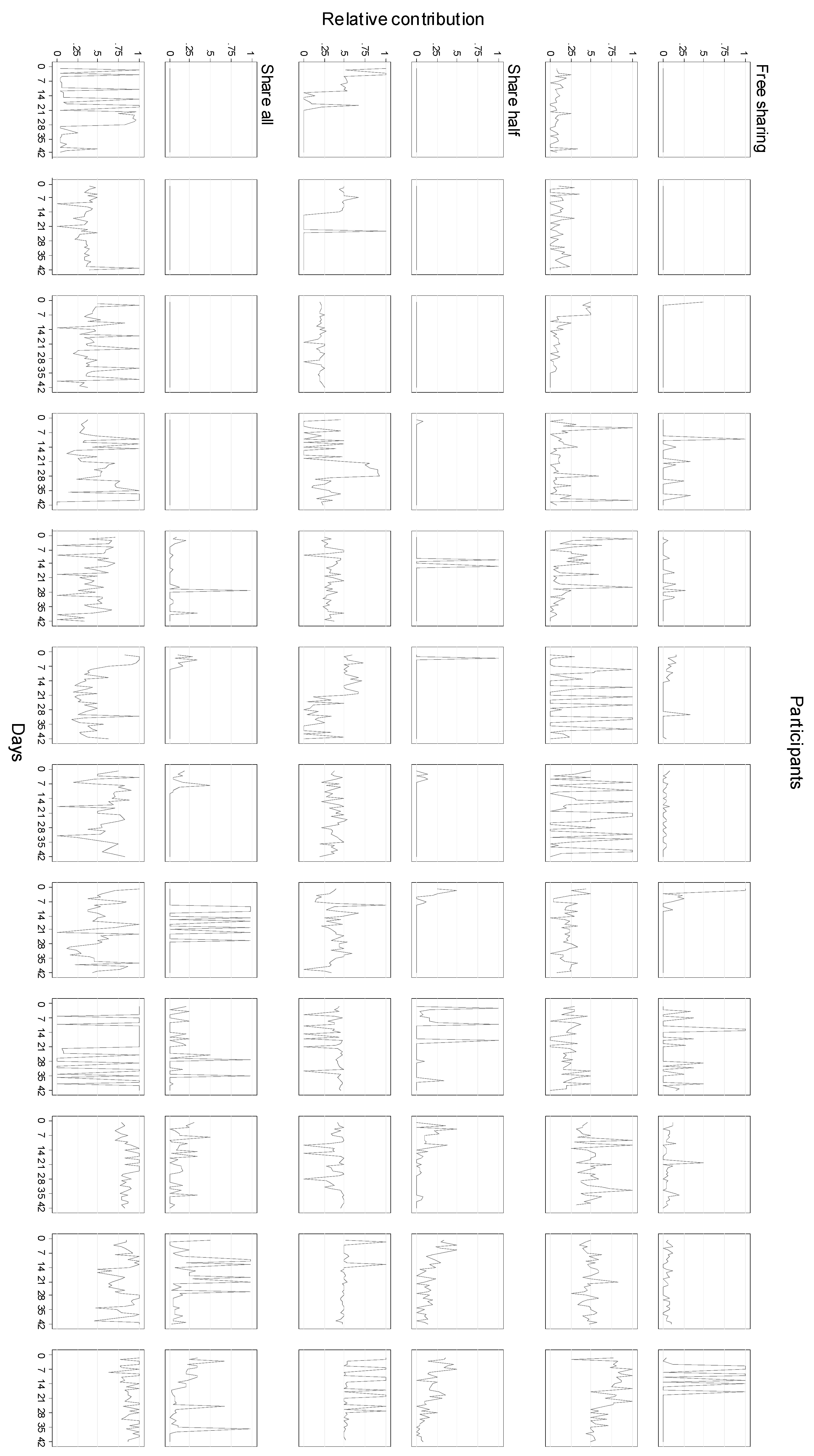

4.2. Relationship between Contribution and Tips

4.3. Results about Individual Contributions

5. Comparison with Public Good Data

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- the number of tokens you received at each day,

- the number of tokens you shared at each day,

- the number of tokens you received back from the common pot,

- the sum of your earnings at each day,

- the number of tokens accumulated since the beginning of the experiment.

Appendix B

| LINEAR TRENDS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Zero Contributions | B. Positive Contributions | C. Relative Contributions | |

| Rule | |||

| Free Sharing | (reference) | (reference) | (reference) |

| Share Half | 1.12 (1.19) | 0.956 (0.908) | 0.035 (0.065) |

| Share All | 0.497 (0.405) | 2.66 (1.13) ** | 0.162 (0.072) ** |

| Tip | 0.943 (0.014) *** | 0.189 (0.036) *** | −0.004 (0.001) *** |

| Constant | 1.96 (1.19) | −0.826 (0.623) | 0.229 (0.045) *** |

| χ2 | 16.21 *** | 27.84 *** | 31.48 *** |

References

- Alexander, L.; Moore, M. Deontological ethics. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Zalta, E.N., Ed.; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, A.E.; Lysonski, S.; Singer, M.; Hayes, D. Ethical myopia: The case of “framing” by framing. J. Bus. Ethics 1991, 10, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.K. Rational Fools: A Critique of the Behavioral Foundations of Economic Theory. Philos. Public Aff. 1977, 6, 317–344. [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Ackerman, S. Charitable Giving and “Excessive” Fundraising. Q. J. Econ. 1982, 97, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandts, J.; Charness, G. Truth or consequences: An experiment. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gneezy, U. Deception: The Role of Consequences. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azar, O.H. The Social Norm of Tipping: A Review 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, M. Tipping in Restaurants and Around the Globe: An Interdisciplinary Review. In Handbook of contemporary behavioral economics: Foundations and developments; Altman, M., Ed.; ME Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 626–643. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, S.J. Restaurant Service Employees Motivation and Organizational Commitment: Shared Gratuity versus Independent Gratuity Environments; University of Nevada: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, A. Tips, Tip Pooling, and Tip Credits. Available online: http://marketdesigner.blogspot.com/2011/01/tips-tip-pooling-and-tip-credits.html (accessed on 19 April 2019).

- Younkins, A.L. Starbucks Case Tips the Scales: Changing California Law to Allow Supervisory Employees Their Fair Share of the Tips. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1415002 (accessed on 10 May 2016). [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Schmidt, K.M. Theories of Fairness and Reciprocity: Evidence and Economic Applications. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=255223 (accessed on 10 February 2019).

- Bicchieri, C.; Dimant, E.; Sonderegger, S. It’s Not a Lie if You Believe It: Lying and Belief Distortion under Norm-Uncertainty. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3326146 (accessed on 10 February 2019).

- Allingham, M.G.; Sandmo, A. Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. J. Public Econ. 1972, 1, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, L.P.; Frey, B.S. Trust breeds trust: How taxpayers are treated. Econ. Gov. 2002, 3, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voss, T. Game-theoretical Perspective on the Emergence of Social Norms. In Social Norms; Hechter, M., Opp, K.-D., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bicchieri, C. Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure, and Change Social Norms; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, T.-H.; Weigelt, K. Trust Building Among Strangers. Manag. Sci. 2005, 51, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kessler, J.B.; Leider, S. Norms and Contracting. Manag. Sci. 2012, 58, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolton, G.E.; Ockenfels, A. ERC: A theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 166–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, G.W. The Methodologies of Behavioral Econometrics. In Contemporary Philosophy and Social Science: An Interdisciplinary Dialogue; Nagatsu, M., Ruzzene, A., Eds.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ledyard, J.O. Public Goods: A Survey of Experimental Research; California Institute of Technology: Pasadena, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Azar, O.H. The implications of tipping for economics and management. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2003, 30, 1084–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, O.H. What sustains social norms and how they evolve?: The case of tipping. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2004, 54, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkan, R.; Erev, I.; Zinger, E.; Tzach, M. Tip policy, visibility and quality of service in cafes. Tour. Econ. 2004, 10, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, U. Z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp. Econ. 2007, 10, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, B. An Online Recruitment System for Economic Experiments. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/13513/ (accessed on 10 May 2015).

- De Quidt, J.; Haushofer, J.; Roth, C. Measuring and Bounding Experimenter Demand. Am. Econ. Rev. 2018, 108, 3266–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zizzo, D.J. Experimenter demand effects in economic experiments. Exp. Econ. 2010, 13, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.D.; Holt, C.A. Experimental Economics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, E.; McCabe, K.; Shachat, K.; Smith, V. Preferences, property rights, and anonymity in bargaining games. Games Econ. Behav. 1994, 7, 346–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Ahn, T.K. Adaptation vs. Anticipation in Public Good Games. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Philadelphia Marriott Hotel, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 28 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, A.; Prasnikar, V.; Okuno-Fujiwara, M.; Zamir, S. Bargaining and Market Behavior in Jerusalem, Ljubljana, Pittsburgh, and Tokyo: An Experimental Study. Am. Econ. Rev. 1991, 81, 1068–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Botelho, A.; Harrison, G.W.; Pinto, L.M.C.; Rutström, E.E. Testing static game theory with dynamic experiments: a case study of public goods. Games Econ. Behav. 2009, 67, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, A. From the Help Desk: Hurdle Models. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata. 2003, 3, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Gächter, S. Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 980–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, R.M.; Walker, J.M. Group size effects in public goods provision: The voluntary contributions mechanism. Q. J. Econ. 1988, 103, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, R.M.; Walker, J.M.; Williams, A.W. Group size and the voluntary provision of public goods. Experimental evidence utilizing large groups. J. Public Econ. 1994, 54, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, L.P.; Frey, B.S. Tax compliance as the result of a psychological tax contract: The role of incentives and responsive regulation. Law Policy 2007, 29, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Most literature related to tipping typically studies the behavior of the tipper, i.e., the client in a restaurant (see, e.g., [7]). Lynn [8] presents empirical research on the determinants and predictors of restaurant tipping and of national differences in tipping habits. Furthermore, the behavioral data is discussed in the light of economic theory and welfare analysis. Roe [9] studies different gratuity sharing arrangements and discusses the effects of these arrangements. We are not aware of any lab tip pooling experiments. |

| 2 | Tip-pooling is an important economic phenomenon: “In 2008, a San Diego trial court slapped Starbucks Corporation with a $100 million judgment for violation of California’s tip sharing laws” [11]. |

| 3 | Since we did not elicit believes nor vary the information structure about each other’s sharing we are not able to analyze the reasons behind the behavior of a subject, in particular how believes influence sharing. For related literature, see [13]. |

| 4 | According to de Quidt and colleagues [28] our rule implication falls under the category “strong demand effect” with the phrase in every period “the rule of the restaurant is … “, similar to “We (experimenters) expect that participants who are shown these instructions will invest more/less in the project than they normally would” as in de Quidt et al. [28]. Zizzo [29] writes along these lines that Davis and Holt [30] (p. 26) “do not see a problem with EDE (Experimenter Demand Effect) if ‘explicit suggestion’ is a treatment variable. This is accurate if identifying an EDE is the objective of the experiment.” In our case, we especially want to see the difference in behavior with different request rules. |

| 5 | A way to avoid experimenter demand effect is using anonymity towards the experimenter in a double-blind procedure [31], which was not implemented in our study. |

| 6 | Subjects knew the exchange rate in advance. We used an artificial currency in case of later replications in other countries with different currencies. This makes comparisons between different data sets more workable (see discussion on currency effects in [33]). However, this could have produced confounds due to money illusion, meaning that high artificial nominal amounts could have reduced misbehavior or, at the opposite, by encouraging gambling behavior [30]. However, these effects should be small as payoffs are quite low in each round. |

| 7 | This effect might be driven by the way relative contributions are computed, combined with the choice of subjects to treat their tips as integers and not as rational numbers. Excluding the choices following a tip of zero (which do not leave subjects any choice but contributing zero), the lowest possible contribution is 1 ECU, which is the 100% of a 1 ECU tip, the 50% of a 2 ECU tip, the 33.3% of a 3 ECU tip, the 25% of a 4 ECU tip and so on. As a result, subjects have more limited choices for lower tips than for higher tips. Therefore it is more difficult to reveal subjects’ preferences with accuracy when tips are low (mainly between 1 and 5 ECU). |

| 8 | A boxplot provides a summary of a distribution: the box represents the interquartile range of variation (IQR, from the 25th to the 75th percentile, named Q1 and Q3 respectively) and the line within the box is the median (Q2); the lower whisker extends to Q1 − 1.5·IQR and the higher one to Q2 + 1.5·IQR. The black dots are suspected outliers, data points falling outside the two whiskers. |

| A. Zero Contributions | B. Positive Contributions | |

|---|---|---|

| Rule | ||

| Free Sharing | (reference) | (reference) |

| Share Half | 1.14 (1.24) | 0.317 (0.091) ** |

| Share All | 0.490 (0.413) | 0.613 (0.103) *** |

| Week | 1.48 (0.132) *** | −0.037 (0.015) * |

| Tip | (exposure) | |

| Constant | 0.206 (0.128) * | −1.30 (0.094) *** |

| χ2(3) | 19.97 *** | 1372.9 *** |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pedersini, R.; Nagel, R.; Le Menestrel, M. The Power of Requests in a Redistribution Game: An Experimental Study. Games 2019, 10, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/g10030027

Pedersini R, Nagel R, Le Menestrel M. The Power of Requests in a Redistribution Game: An Experimental Study. Games. 2019; 10(3):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/g10030027

Chicago/Turabian StylePedersini, Riccardo, Rosemarie Nagel, and Marc Le Menestrel. 2019. "The Power of Requests in a Redistribution Game: An Experimental Study" Games 10, no. 3: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/g10030027

APA StylePedersini, R., Nagel, R., & Le Menestrel, M. (2019). The Power of Requests in a Redistribution Game: An Experimental Study. Games, 10(3), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/g10030027