Abstract

The formation of valuable chiral skeletons through asymmetric gold catalysis has made considerable progress due to the unrivaled affinity of gold complexes with multiple carbon–carbon bonds. The renaissance of chiral ligands in recent decades has enabled the elaborate design of chiral gold complexes, which are of great significance to control chiral formation in these catalytic reactions. Therefore, this review intends to highlight the design and central role of versatile chiral ligands in asymmetric gold catalysis. Specifically, the seminal applications of various chiral ligands with representative examples in various gold-catalyzed asymmetric reactions are comprehensively explored. In addition, the reaction mechanisms are mentioned when the crucial interactions between ligands and activated substrates are introduced. Furthermore, the applications of enantioselective gold catalysis in the construction of chiral functional organic materials and drug molecules are also presented.

1. Introduction

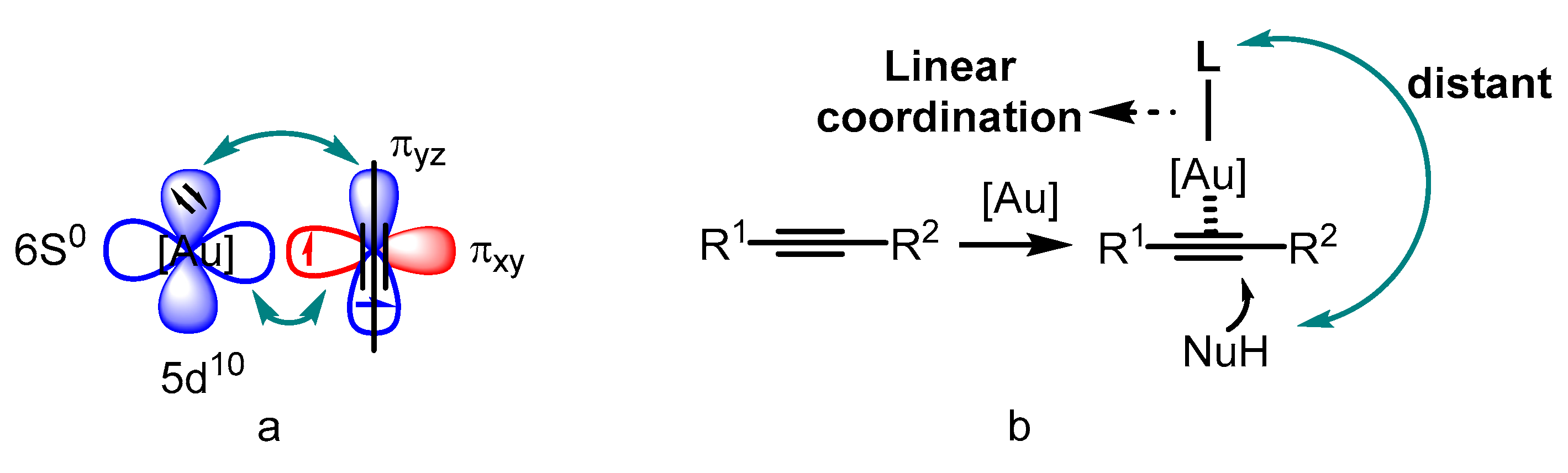

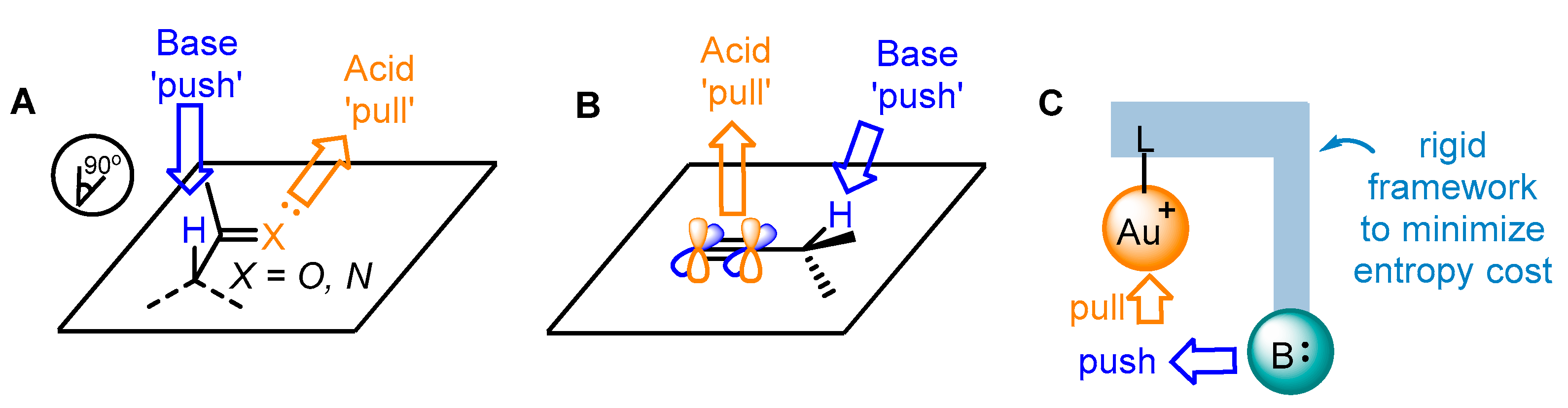

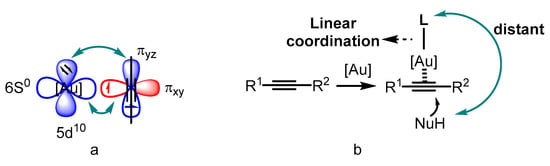

Catalysis is an advanced technology in both the chemical industry and academic research [1,2,3]. Transition-metal catalyzed organic transformations have attracted a great deal of attention for the efficient crack and formations of chemical bonds [4,5,6,7]; therefore, they have been widely applied in the research and development of drugs, pesticides, fine chemicals and other functional materials [8,9,10]. Compared to other transition metals, the d10 electron configuration of gold(I) results in superior π affinity for multiple carbon–carbon bonds (Figure 1a) [11,12,13,14,15]. In addition, the gold center adopted by linear coordination places the ancillary ligand and substrate in opposite positions (Figure 1b). Thus, the conventional chelating mode of the ligands used in catalytic reactions involving other transition metals could not be employed for the design of ligand-modified gold catalysts. Furthermore, the gold(I)-catalyzed carbophilic addition of nucleophiles to carbon–carbon triple bonds proceeds through outer-sphere activation [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. These factors make asymmetric modulation in gold(I) catalysis challenging. On the other hand, several gold(III) catalysts have also been reported to be active for such transformations because of their inherent square-planar geometry that promotes the formation of chiral centers.

Figure 1.

The superior π affinity mode (a) and the linear coordination format (b).

The practical atom economy and step economy of enantioselective gold catalysis are attributed to its unique catalytic mode for constructing sets of complex molecules and efficient tandem processes, even when dealing with remote substrates and chiral ligand fragments [25,26,27,28,29,30]. Enantioselective gold catalysis has flourished due to its distinct performance. In particular, a series of valuable chiral ligands have been identified, including aryl phosphine ligands bearing the proximal chiral sulfinamide motif, phosphoramidite and phosphonite ligands, phosphine ligands comprising the ferrocene scaffold, bifunctional phosphine ligands, biphosphine ligands, chiral counterion-based ligands derived from chiral phosphoric acids and chiral carbene ligands for gold(I) catalysis, along with unique ligand frameworks for cyclometalated gold(III) catalysis. Notably, these types of chiral ligands and structural modifications are of crucial significance.

In practice, there are several reviews already reported in the literature [31,32,33]. These reviews mainly focus on the latest development of ligands or the defined types of reactions in asymmetric gold catalysis. However, it has been observed that the initial conception of elaborated design for novel ligands can lead to the creation of new asymmetric reactions and further accurate modification for the known ligands. Accordingly, the objective of this review is to stress the key role of chiral ligands in achieving modulation of chiral formation alongside exploring the unprecedented bonding modes and distinct activation efficiencies for multiple carbon–carbon bond-involving reactions. The seminal elaborated design and important progress of chiral ligands are the main focus of the review. To this end, we present a comparison of different ligands in most cases, while the state-of-the-art desired designs for ligands are inevitable considerations in “match” or “mismatch” effects for reactions. There is also a brief mention of reaction mechanisms, which are explained through interactions between ligands and activated substrates. Furthermore, the applications of enantioselective gold catalysis in the construction of chiral functional organic materials and drug molecules are also outlined.

2. Classification of Various Ligands

Various chiral organic ligands have been applied to asymmetric gold catalysis, representing an important part of transition-metal-catalyzed asymmetric transformations. Among them, the phosphine-containing ligands are one of the most common and effective. In addition, non-phosphine ligands, including chiral carbene and cyclometalated ligands, have also been developed by different research groups. To discuss these ligands in an appropriate order, the first Section 2.1, Section 2.2, Section 2.3, Section 2.4, Section 2.5 and Section 2.6 intend to focus on the different types of phosphine ligands. The second Section 2.7 aims to address chiral carbene ligands followed by the third Section 2.8 referring to cyclometalated ligand frameworks.

2.1. Phosphoramidite and Phosphonite Ligands

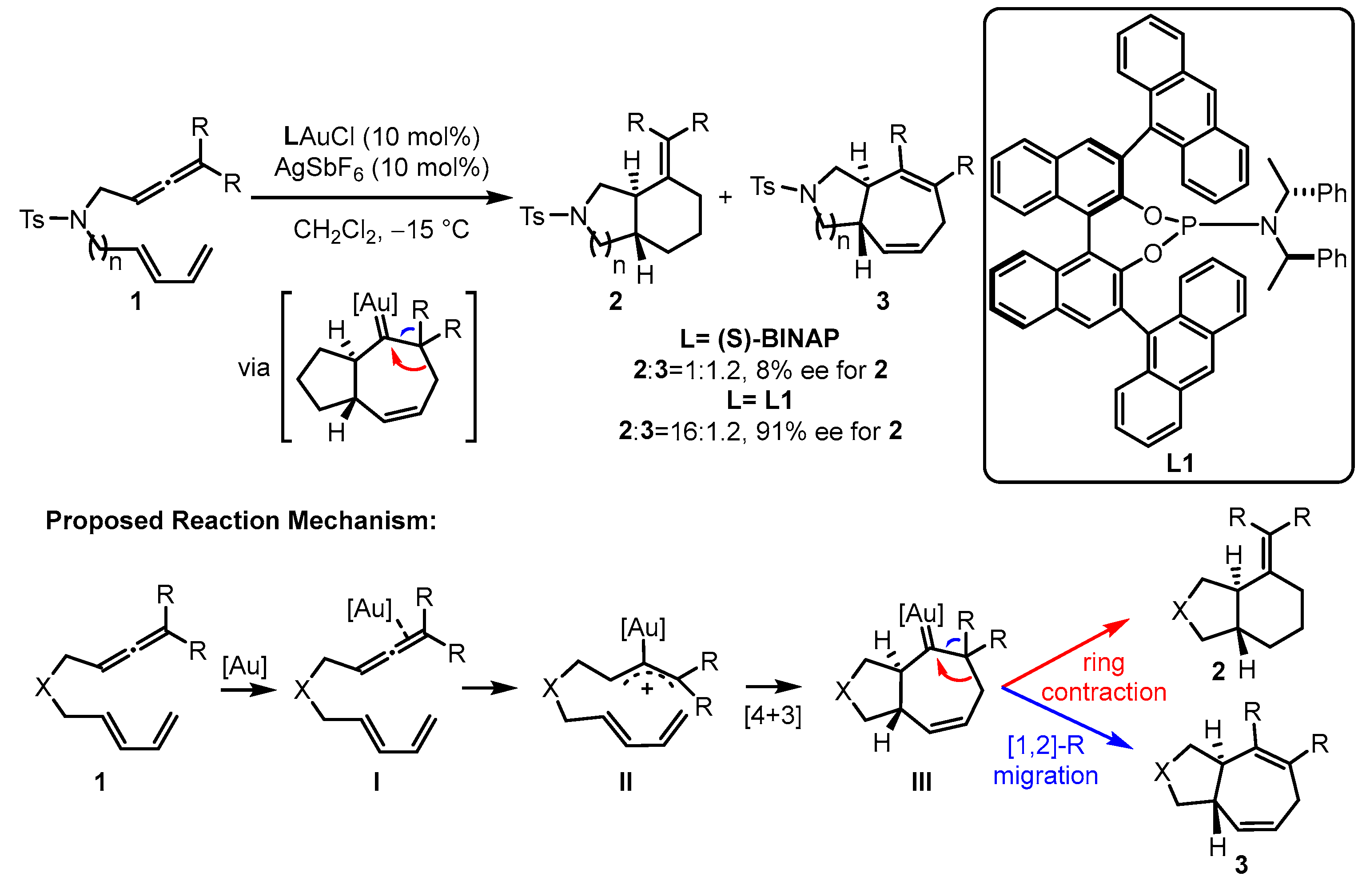

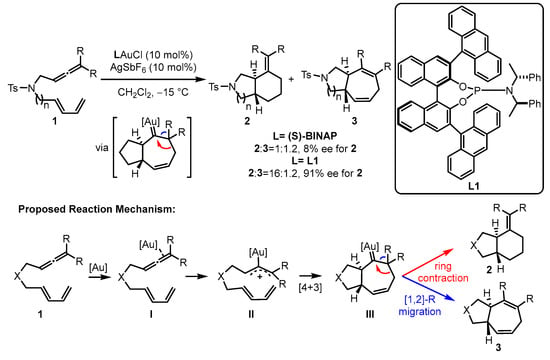

In the gold(I)-catalyzed [4 + 3] or [4 + 2] cyclization, electron-withdrawing phosphite ligands are believed to fit the excellent activation of the corresponding gold(I) catalysts [34,35]. To construct better chiral modulation for the challenging asymmetric gold(I) catalysis, phosphoramidite ligands have also been incorporated into the catalytic systems owing to their similar electronic properties with phosphites and π–π interactions with substrates resulting from the attenuated flexibility around the gold center as well as the closer chiral information to the new carbon stereocenters. For the enantioselective intramolecular cycloaddition of allene-tethered 1,3-dienes 1, the bicyclic products 2 and 3 can be furnished smoothly, and phosphoramidite ligand L1-ligated gold(I) catalyst displayed superior chemoselectivity (16:1.2) and enantioselectivity (91% enantiomeric excess (ee)) over the chiral bisphophine (S)-(−)-2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthalene (S-BINAP)-coordinated gold(I) analogue (Scheme 1) [36]. The proposed mechanism begins with the activation of an allene through the coordination of a gold complex. This activation leads to a concerted [4 + 3] cycloaddition, resulting in the formation of gold carbene intermediate III. The selectivity between [1,2]-R migration and ring contraction was demonstrated with density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The calculation results indicate that the ring contraction pathway possesses a lower energy barrier than that of the [1,2]-R migration pathway.

Scheme 1.

The chiral phosphoramidite-tethered gold(I)-catalyzed asymmetric cycloaddition.

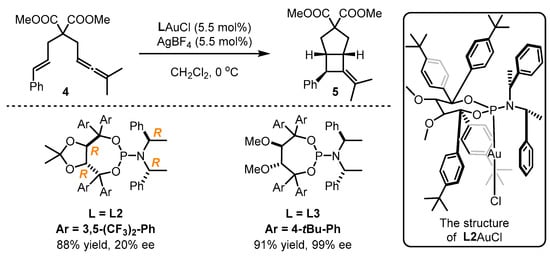

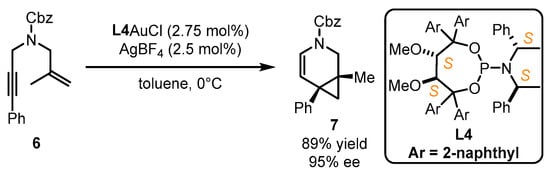

Fürstner et al. implemented enantioselective cyclopropanation of styrene 4 catalyzed by a gold(I) catalyst bearing a bulky steric chiral phosphoramidite ligand associated with the 1-(2-hydroxynaphthalen-1-yl)naphthalen-2-ol (BINOL) core [37]. Nevertheless, the performance of structural modifications on this type of ligand is difficult. Accordingly, the authors further developed chiral gold catalysts with phosphoramidites featuring the α,α′-(dimethyl-1,3-dioxolane-4,5-diyl)bis(diphenylmethanol) (TADDOL) backbone (Scheme 2). With a certain adjustment of aryl substitution in the TADDOL part and amine component, L3 was found to be an ideal companion for the gold catalyst in asymmetric [2 + 2] cyclization with a 91% yield and 99% ee value, while inferior results were obtained with the employment of L2 [38]. The crystal structure of L2AuCl suggests that the two phenyl groups from the TADDOL part along with one phenyl ring from the amine part can form a cone-shaped binding pocket surrounding the gold atom. This pocket effectively restricts the flexibility of the gold center and conveys the chirality information to the final product. Another study illustrated that L4 was highly effective to realize the gold-catalyzed enantioselective cycloisomerization of 1,6-enyne 6, leading to the formation of the bicyclic product 7 in 89% yield and 95% ee (Scheme 3) [39]. Despite being an ancillary point to the gold catalysts, this ligand type displays remarkable chiral transformation for π-acidic activation.

Scheme 2.

The application of TADDOL-containing ligands L2 and L3 in asymmetric gold catalysis.

Scheme 3.

The application of TADDOL-containing ligand L4 in asymmetric gold catalysis.

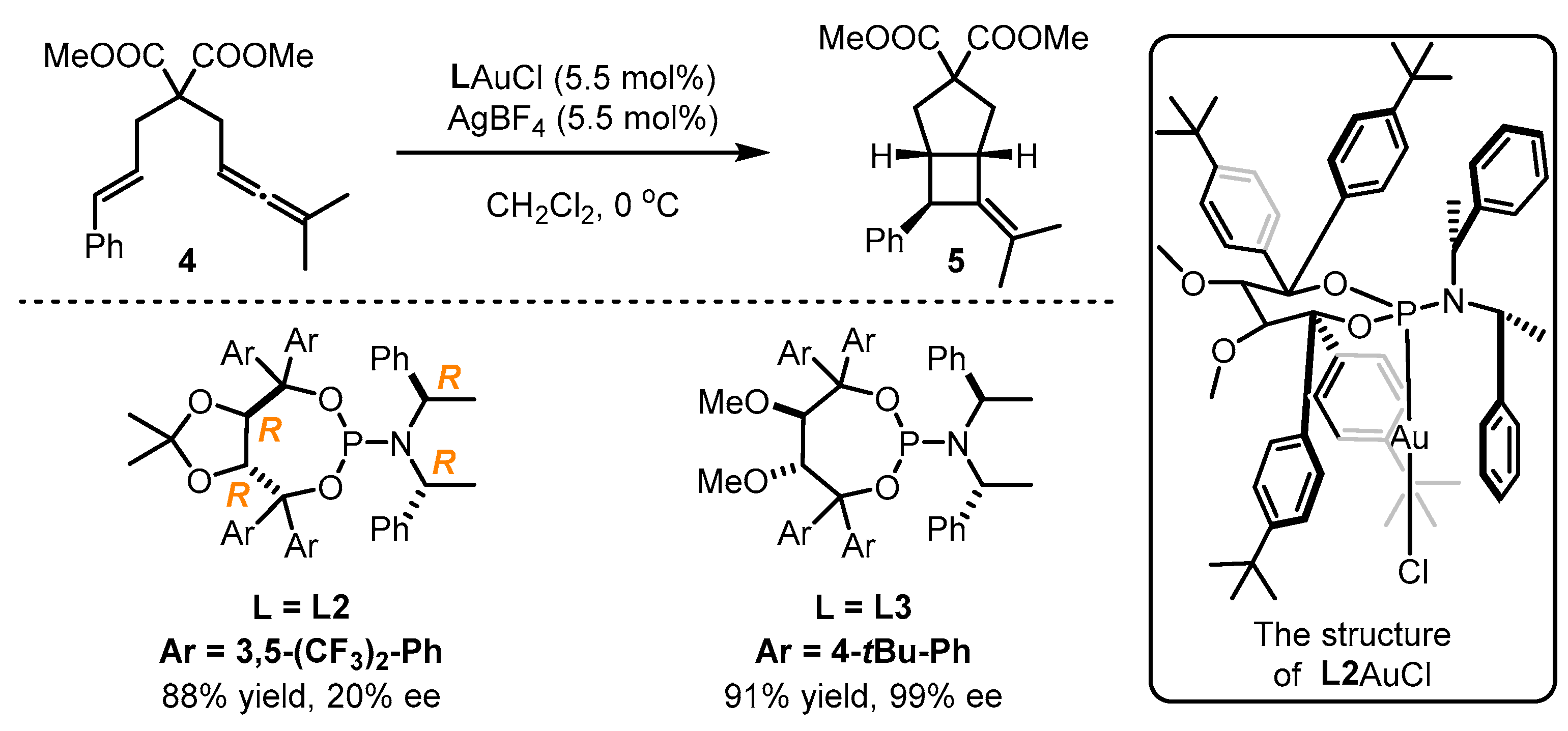

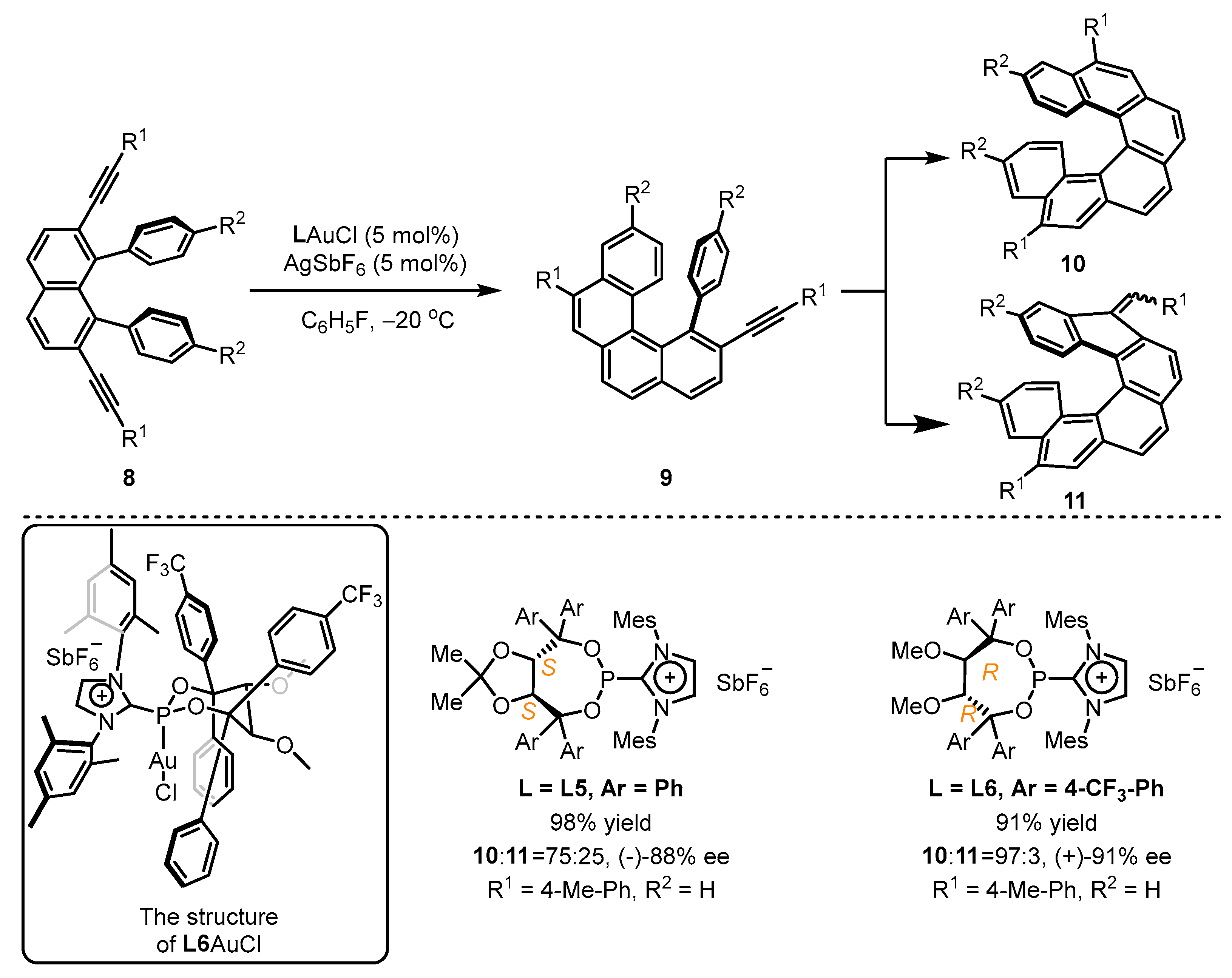

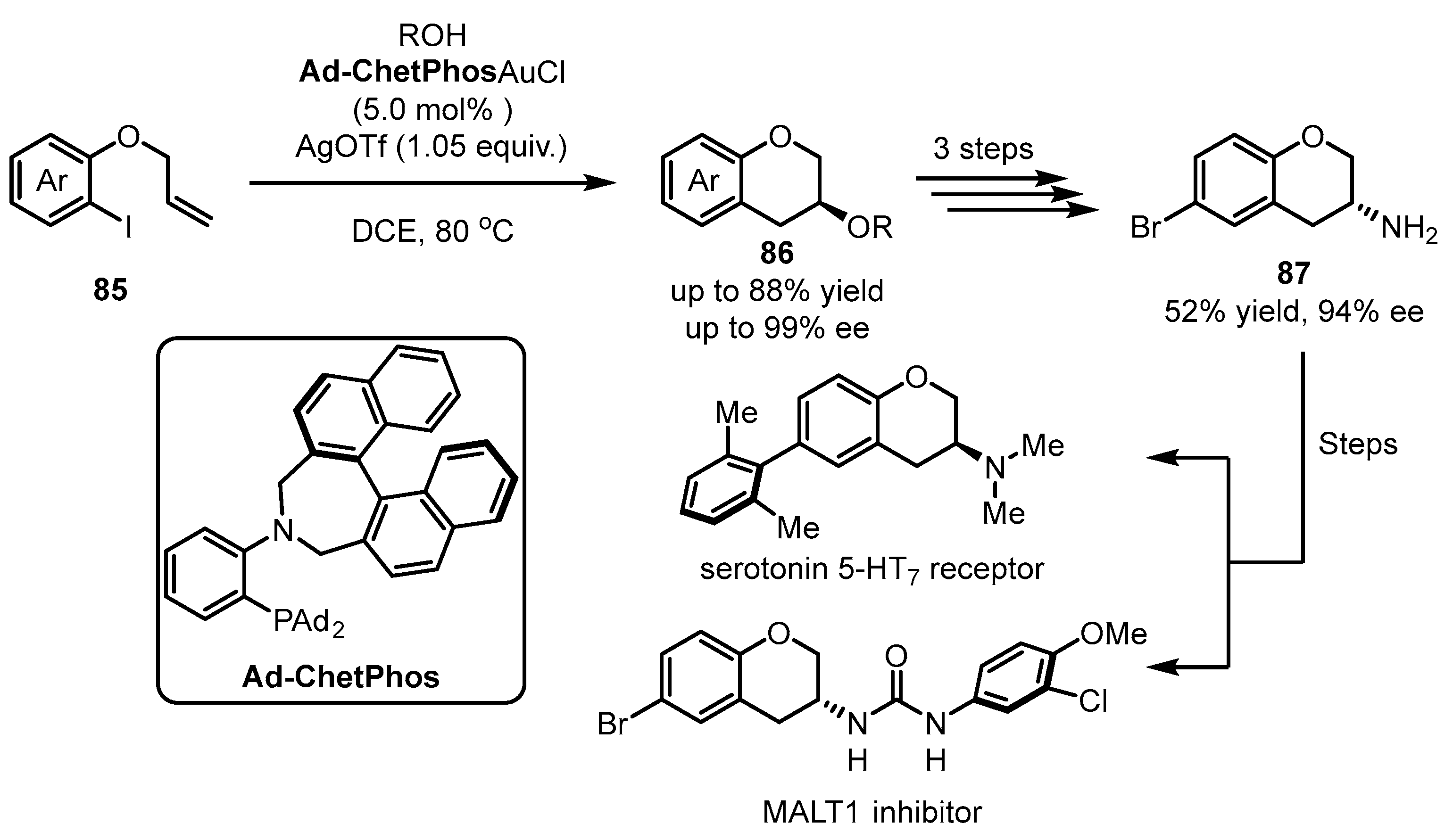

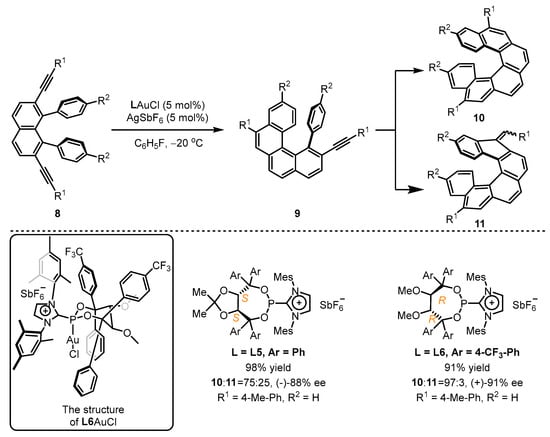

In pursuit of greater success, the Alcarazo group adopted an elaborated preparation of chiral cationic ancillary phosphonites and developed asymmetric cyclization of diyne 8 (Scheme 4) [40]. Their design utilized the TADDOL backbone to provide an appropriate chiral pocket for this catalytic process, while the cationic imidazolium unit introduced a positive charge to enhance the catalytic activity of the corresponding gold(I) template, leading to the facile synthesis of chiral helicene 10 with excellent regioselectivity and enantioselectivity when the L6-coordinated gold(I) catalyst was employed. However, L5 was unsatisfactory in this regard. The single-crystal structure of L6AuCl clearly reveals that the gold atom can immerse into a chiral pocket resulting from two CF3-phenyl groups and one mesityl group. Compared with L5AuCl, the formation of a seven-membered ring without the constrains of annulation was observed for L6AuCl, which leads to a closer contact between the gold atom and the three vicinal aryl substituents.

Scheme 4.

Chiral cationic ancillary phosphonites applied in gold(I) catalysis.

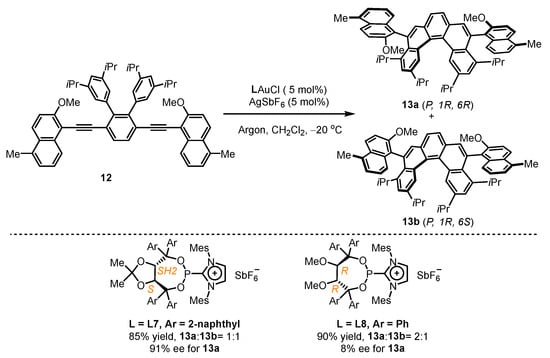

Given the success of TADDOL-type phosphonites in gold(I)-catalyzed enantioselective hydroarylation, the Alcarazo group attempted to construct one helical and two axial stereogenic elements in one molecule using similar ligands (Scheme 5) [41]. They anchored multi-substituted diyne 12 for the attempt of gold(I) catalysts comprising chiral cationic ancillary phosphonites. It was found that L7 led to the simultaneous isolation of 13a and 13b with a remarkable 91% ee value for 13a. However, L8 was not up to the task, resulting in an unsatisfactory 8% ee value for 13a despite exhibiting excellent catalytic activity with a total yield of 90% for 13a and 13b.

Scheme 5.

Chiral cationic ancillary phosphonites applied in gold(I) catalysis.

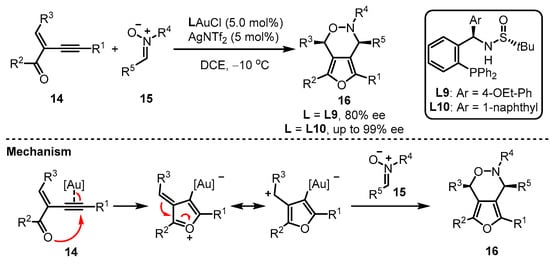

2.2. Aryl Phosphine Ligand with a Proximal Chiral Sulfinamide

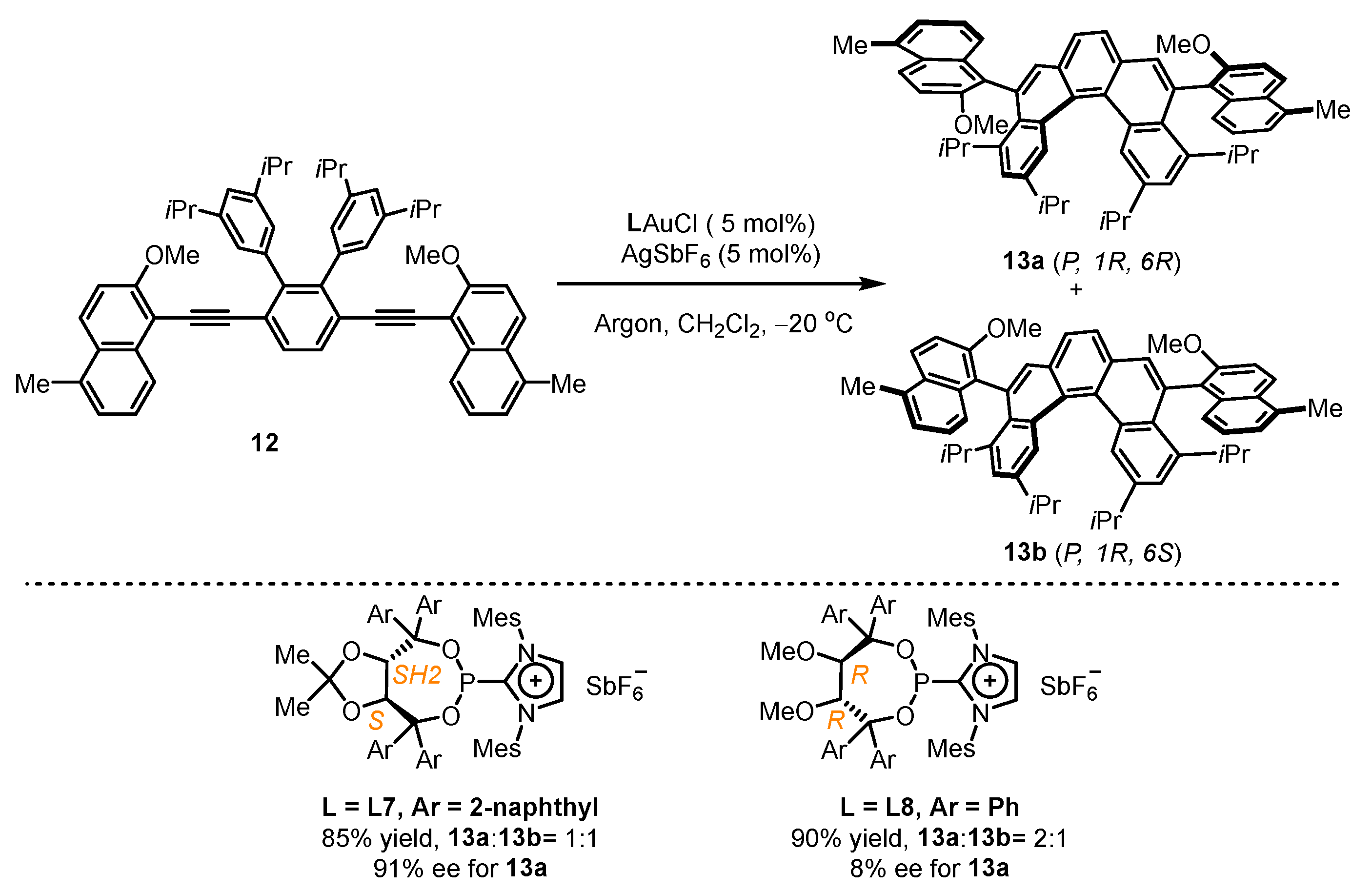

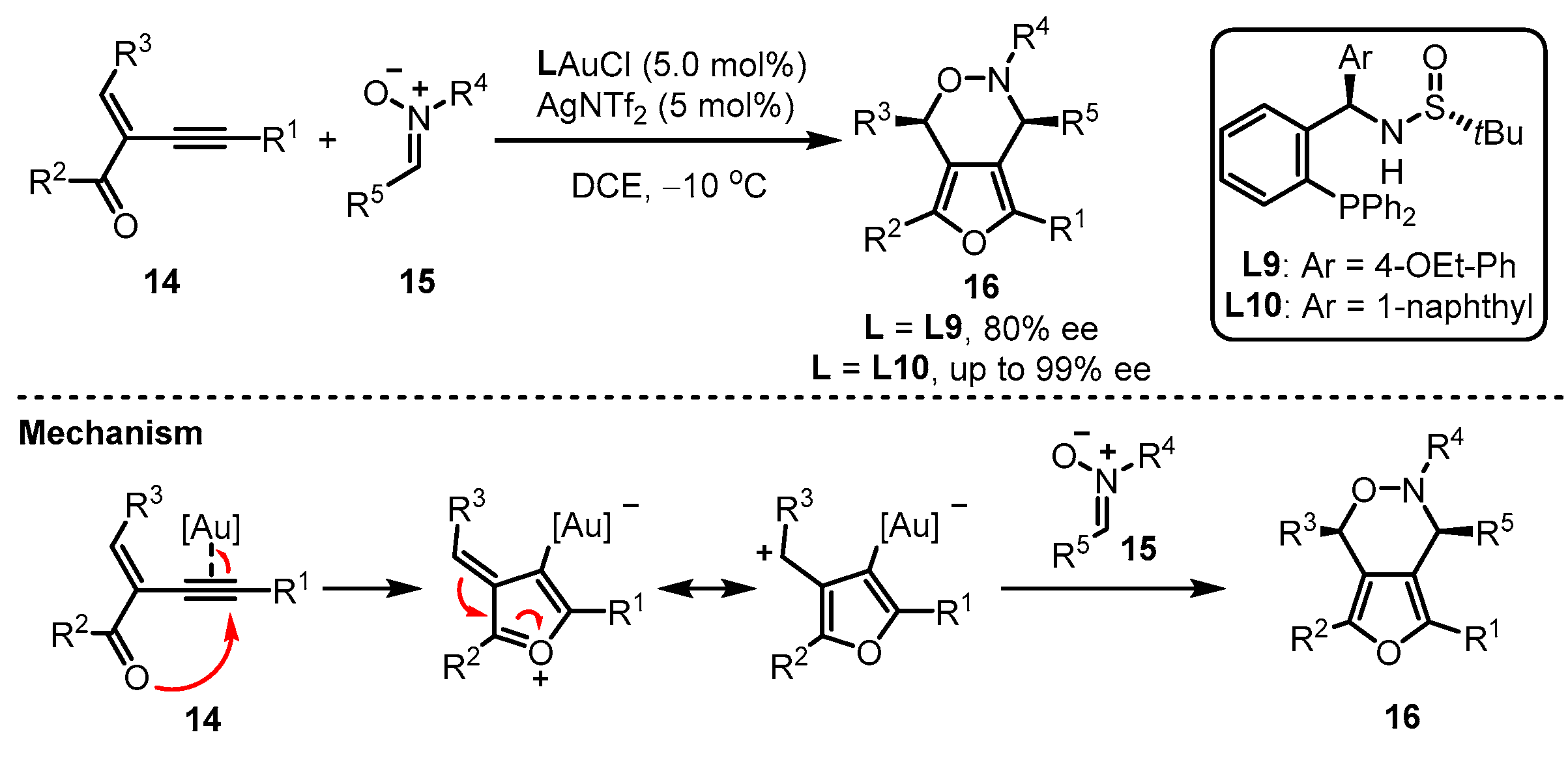

Apart from the phosphoramidite and phosphonite ligands mentioned above, aryl phosphine ligands bearing one chiral sulfinamide motif have also been developed. As reported by Zhang and coworkers, the in situ formed monogold cationic catalyst generated from digold chloride [(AuCl)2] always showcased a better catalytic activation ability than the pre-prepared monogold cationic catalyst [42,43]. Zhang et al. provided an elaborate design of the MingPhos series (including L9 and L10), where the chiral sulfinamide moiety containing adjustable steric groups was located on the ortho-position of the aryl phosphines (Scheme 6) [44]. The L9/L10-tethered gold(I) complexes performed good activity for the intermolecular asymmetric cycloaddition of 2-(1-alkynyl)-2-alken-1-one 14 and nitrone 15 with the L10-based gold complex exhibiting higher performance than the L9-containing analogue in terms of enantioselectivity. Moreover, a proposed mechanism was presented.

Scheme 6.

Asymmetric synthesis of chiral α-Allyl-α,β-butenolides.

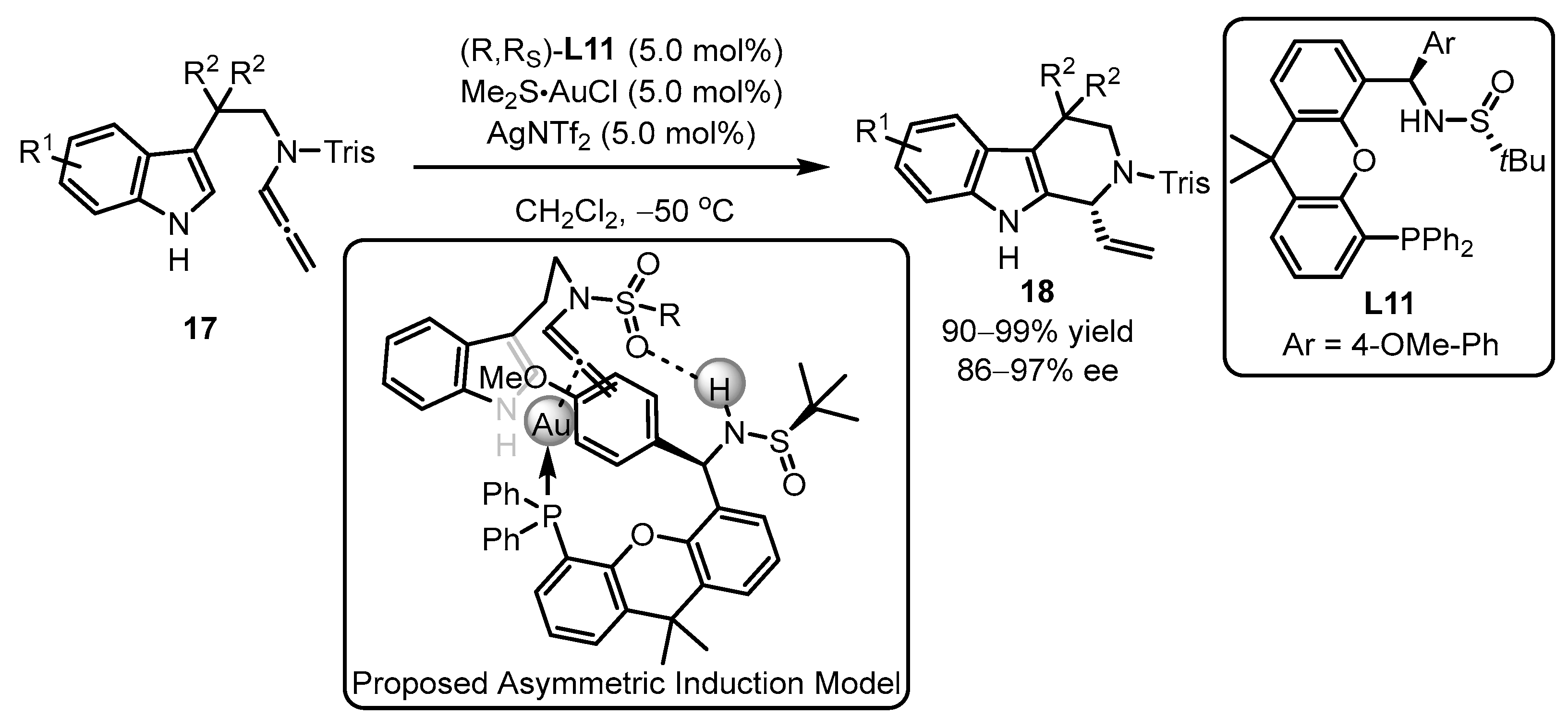

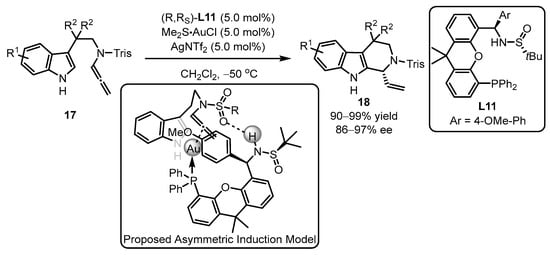

PC-Phos ligands, featuring a bigger chiral cave and bigger retortion of the sulfinamide part to the proximal phosphine part, were later exploited by Zhang et al. (Scheme 7) [45]. As expected, the catalytic system accommodated protected N-allenamide 18 smoothly with a 99% yield and 96% ee. The ligand L11 and a suitable protecting group were crucial for the control of high regioselectivity and enantioselectivity in this catalytic process. The authors proposed an asymmetric induction model based on the structure of L11AuCl and product 18. According to the model, the indole part only attacks the gold-activated allene bond at the Si face. Otherwise, if the attack occurs from the other side, the nucleophilic attack will be blocked by the steric obstacle from the OMe group in phosphine. Additionally, the chirality transfer can be facilitated by the hydrogen bonding interaction between the sulfonyl group and the N–H bond from the amino group, as suggested by the model of the substrates and the chiral PC-Phos ligands.

Scheme 7.

PC-Phos ligands ancillary to gold complex for the asymmetric arylation.

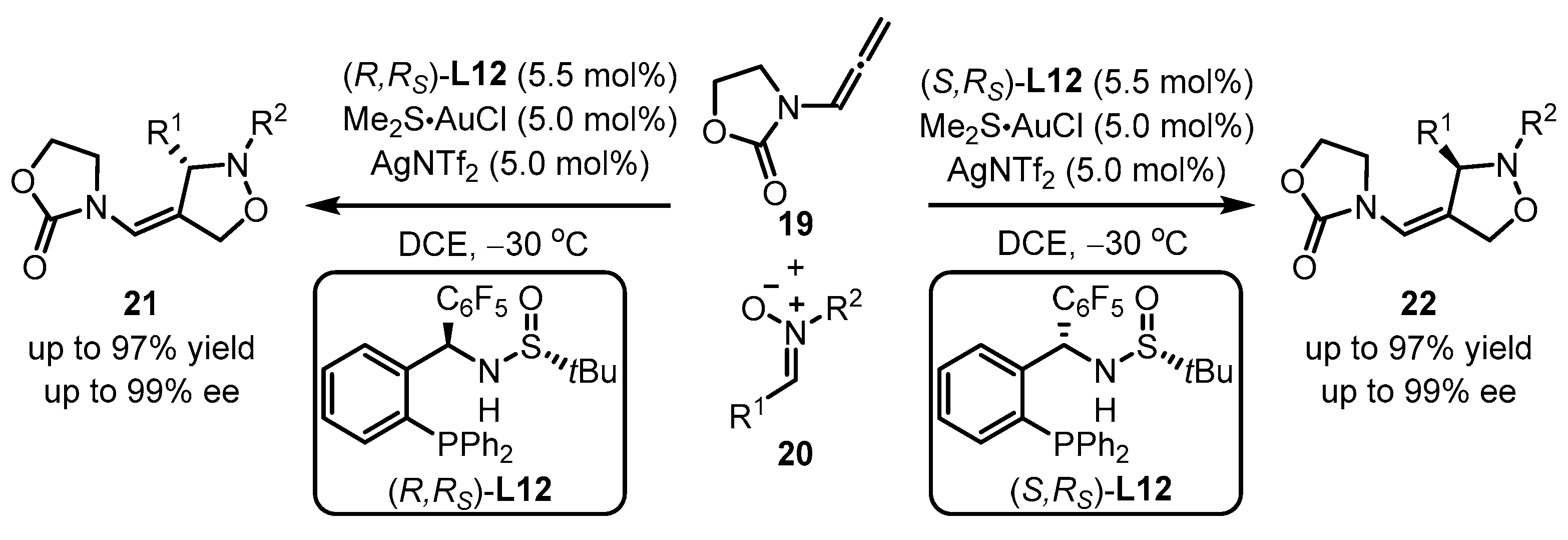

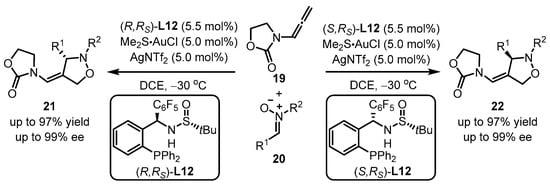

Recently, MingPhos ligands were introduced into gold(I)-catalyzed intermolecular asymmetric [3 + 2] cycloaddition of N-allenamides 19 and nitrone 20 by Zhang et al. (Scheme 8) [46]. To note, the opposite enantiomers of oxazolidin-2-one 21 or 22 were achieved via the usage of (R,Rs)-L12 or the corresponding (S,Rs)-L12. The interactions between the sulfinamide N−H group and the pentafluorophenyl substituent are responsible for the effective allocation of chirality transfer.

Scheme 8.

MingPhos ligands ancillary to gold complexes for asymmetric arylation.

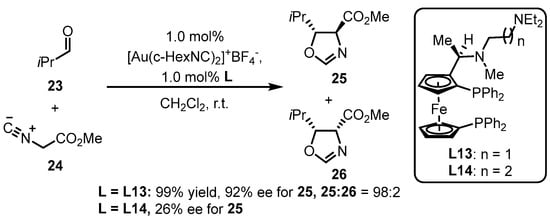

2.3. Phosphine Ligands Comprising the Ferrocene Scaffold

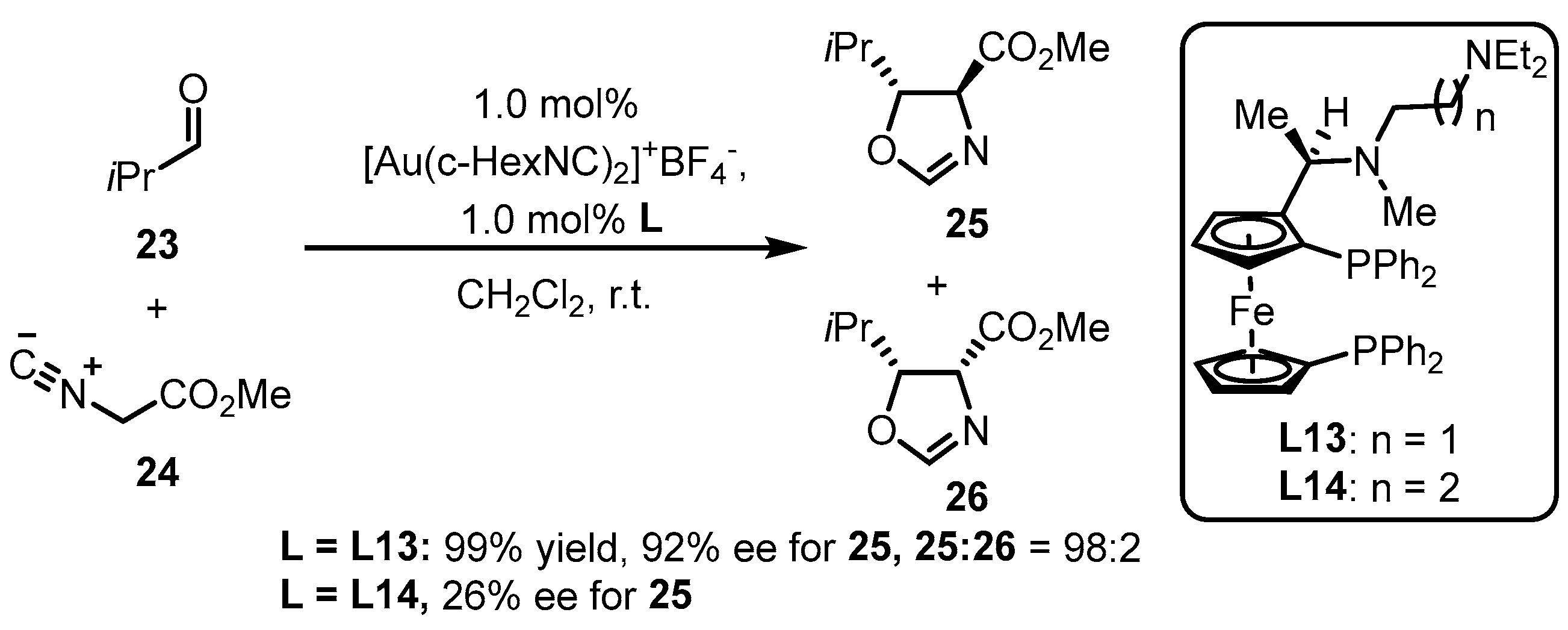

Phosphine ligands bearing the ferrocene backbone are a typical class of chiral ligands used for enantioselective gold(I) catalysis due to their easy accessibility and possibility to modulate chiral formation. Hayashi and colleagues reported the successful cooperation between chiral bisphosphines with the ferrocene backbone decorated with an amino group and a gold complex, in situ generating an chiral gold species for the asymmetric aldol reaction of aldehyde 23 and isocyanoacetate 24 (Scheme 9) [47]. The diastereoselectivity and enantioselectivity depend on the selection of a bulky aldehyde and a suitable ligand. Furthermore, the L13-tethered gold template provided divergent chiral oxazoline derivative 25, while the similar ligand (L14) did not efficiently catalyze the process.

Scheme 9.

Phosphine ligands possessing the ferrocene backbone for asymmetric gold catalysis.

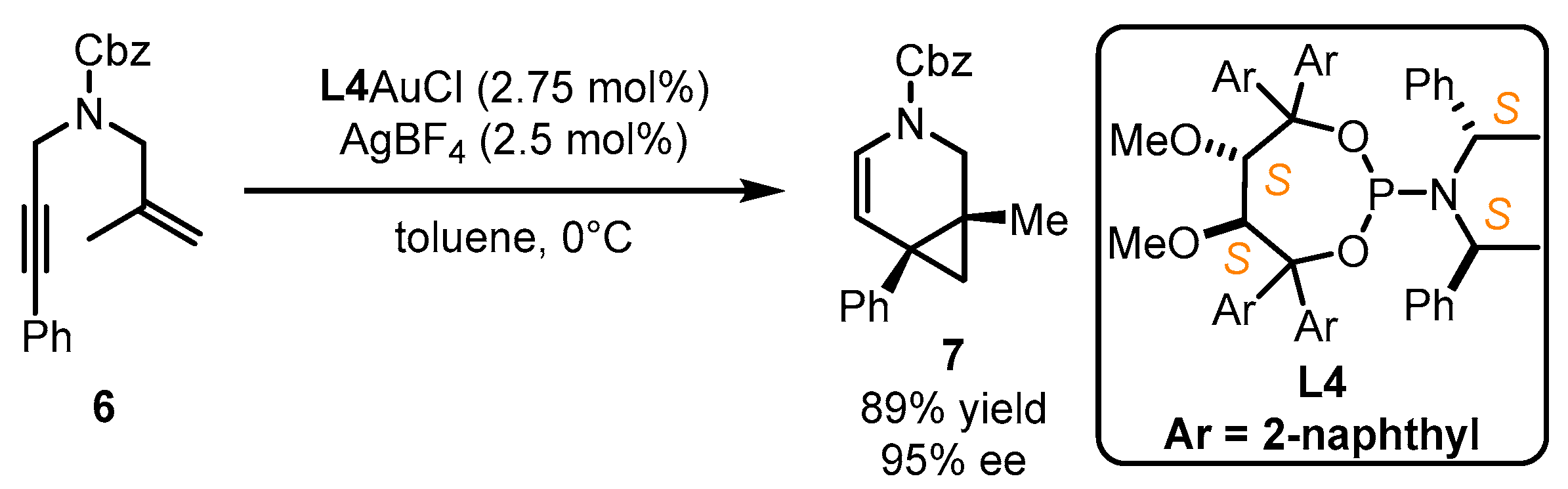

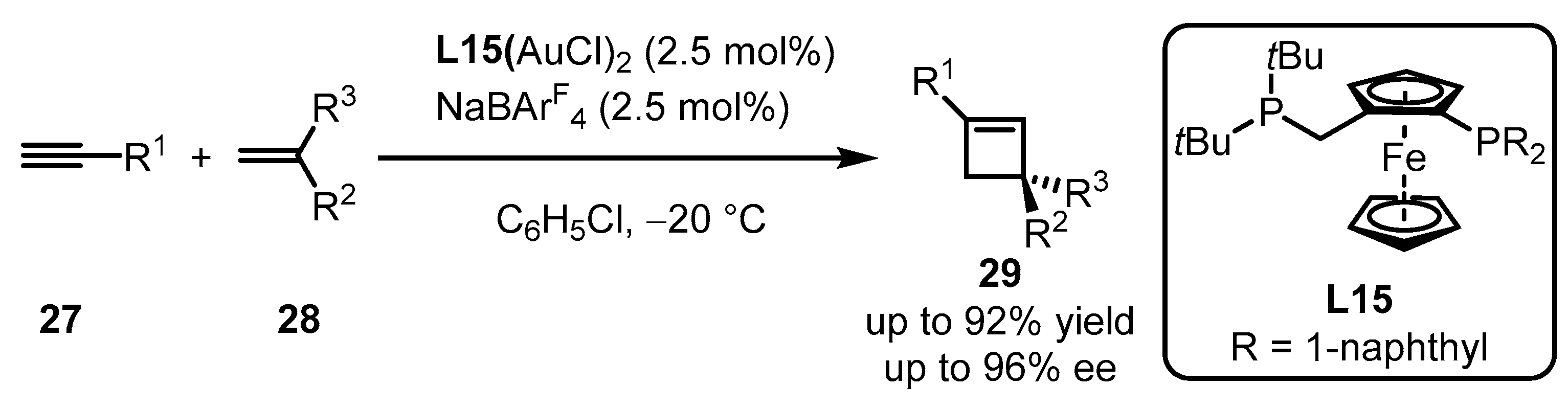

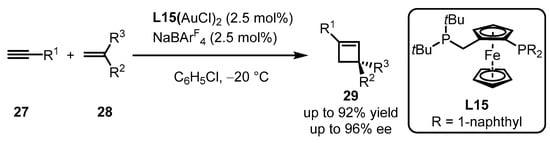

Owing to the outer-sphere catalytic mode between a gold(I)-activated carbon–carbon triple bond and a nucleophile, the intermolecular asymmetric [2 + 2] cycloaddition of terminal alkynes 27 with alkenes 28 is challenging to conduct in gold(I) catalysis. High-throughput methods, including the screening of 90 chiral ligands, were employed to accelerate the formation of chiral cyclobutene via gold(I) catalysis (Scheme 10) [48]. Non-C2 symmetric bisphosphine ligand L15 with the ferrocene skeleton was found to be an excellent promoter for the corresponding gold(I) complex, providing catalytic reactivity under the accurate ratio of the gold(I) complex to NaBArF4 in a 1:1 ratio.

Scheme 10.

Ferrocenyl bisphosphine-ligated gold catalyzed asymmetric [2 + 2] cycloaddition.

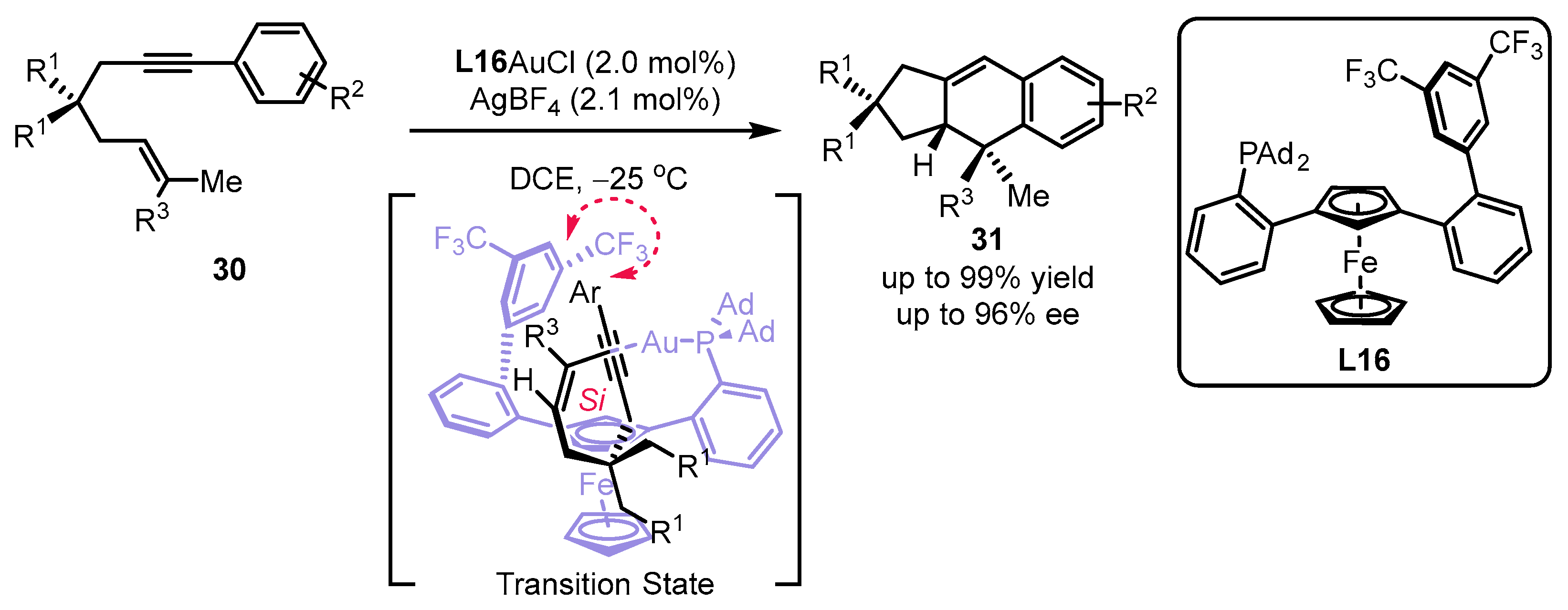

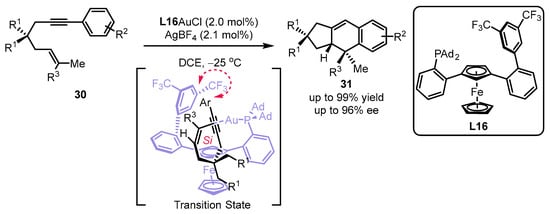

In light of the chiral JohnPhos-type scaffold, the Echavarren group synthesized a set of planar chiral monodentate 1,3-disubstituted ferrocenyl phosphines for the assembly of a sterogenic gold(I) complex (Scheme 11) [31]. It was suggested that the ancillary bulky adamantyl in ferrocene was required for the excellent performance of L16 in the desired [4 + 2] cyclization [49]. From the DFT calculations, the T-shaped π–π interaction between 3,5-(CF3)2-aryl from the phosphine ligand and an aryl group from the substrate as well as the Si face interaction of an alkenyl group with an alkynyl group meet the lowest energy for the chirality transfer.

Scheme 11.

Design of planar chiral phosphines for the asymmetric [4 + 2] cyclization.

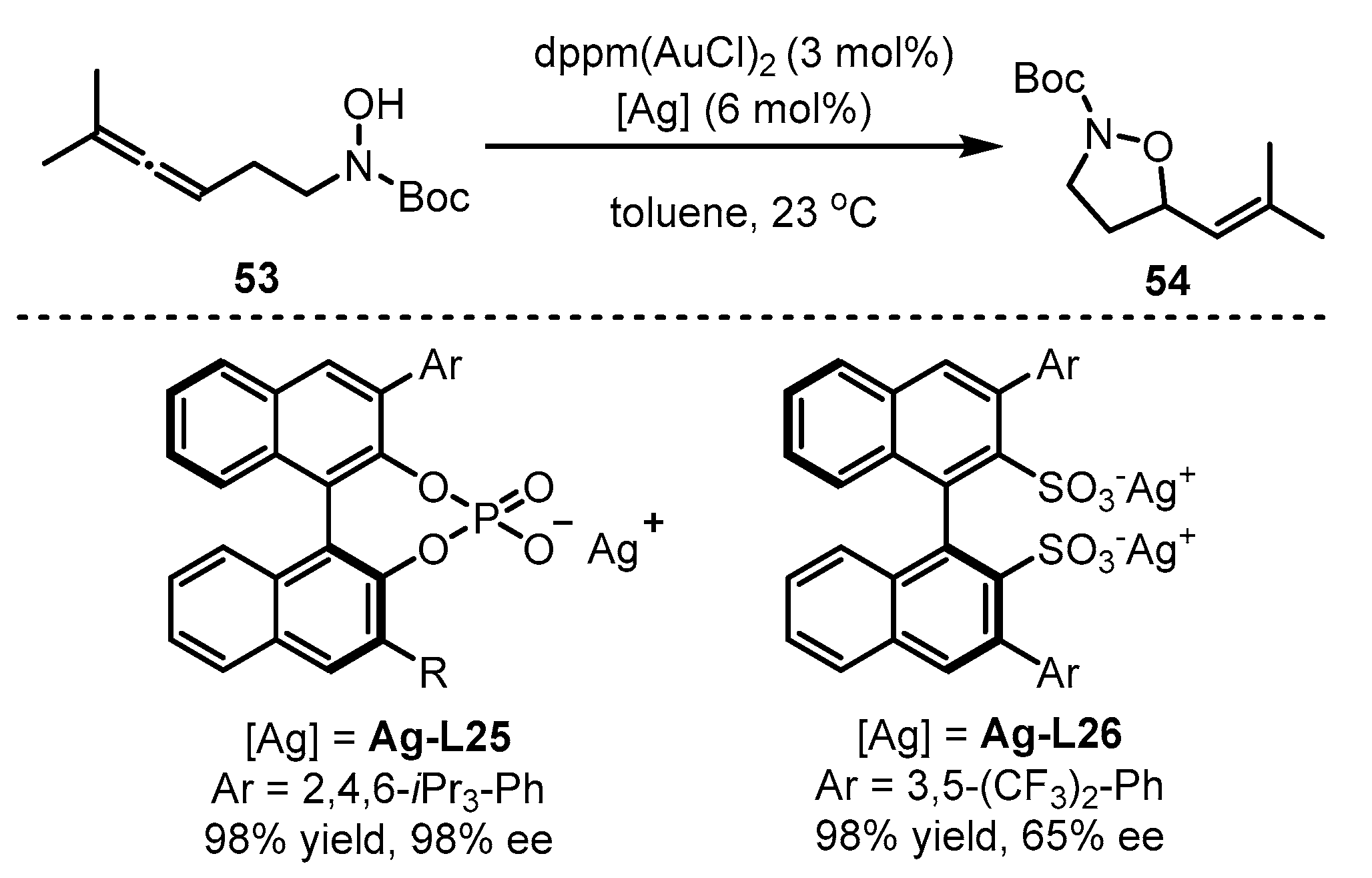

2.4. Bifunctional Phosphine Ligand

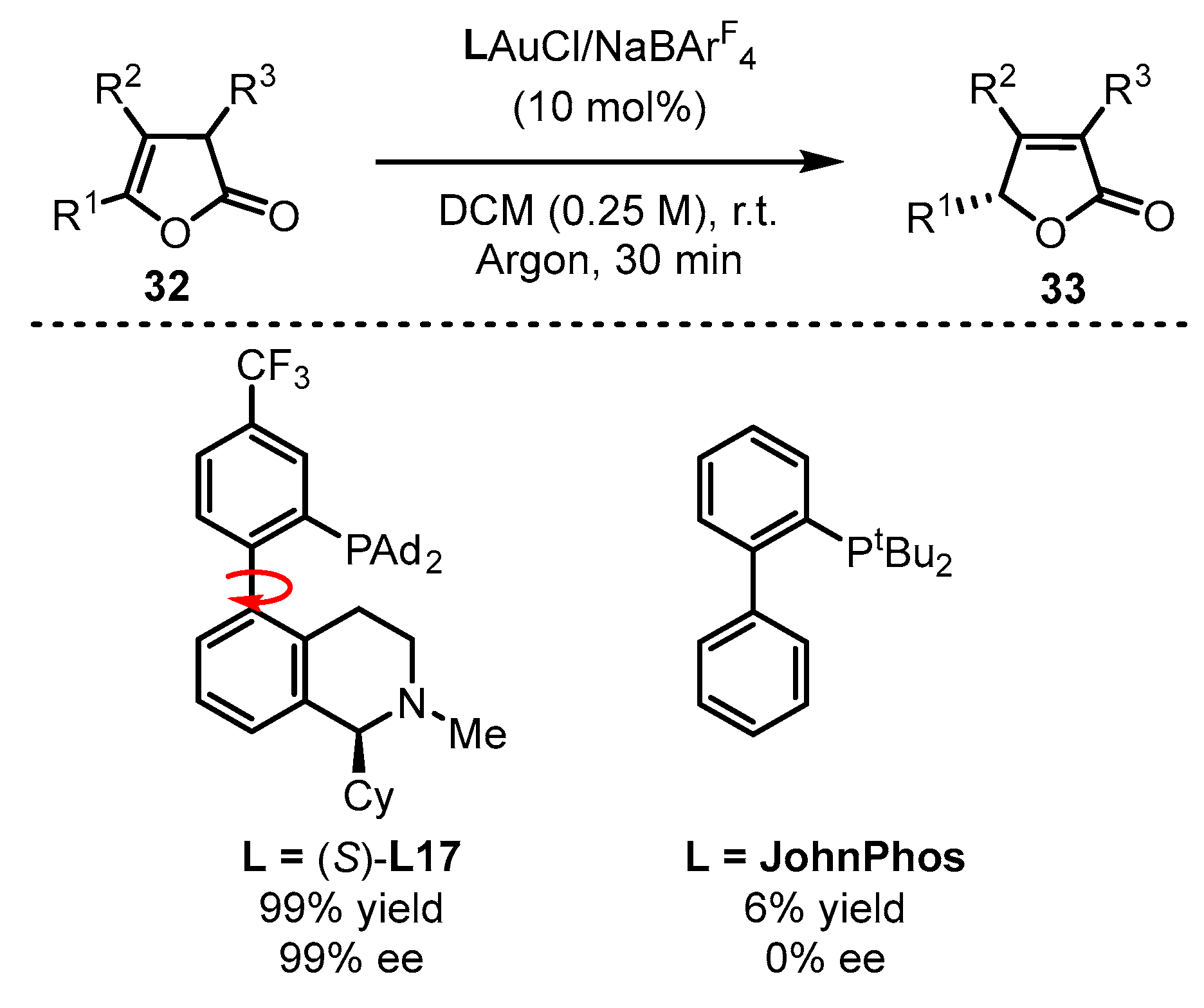

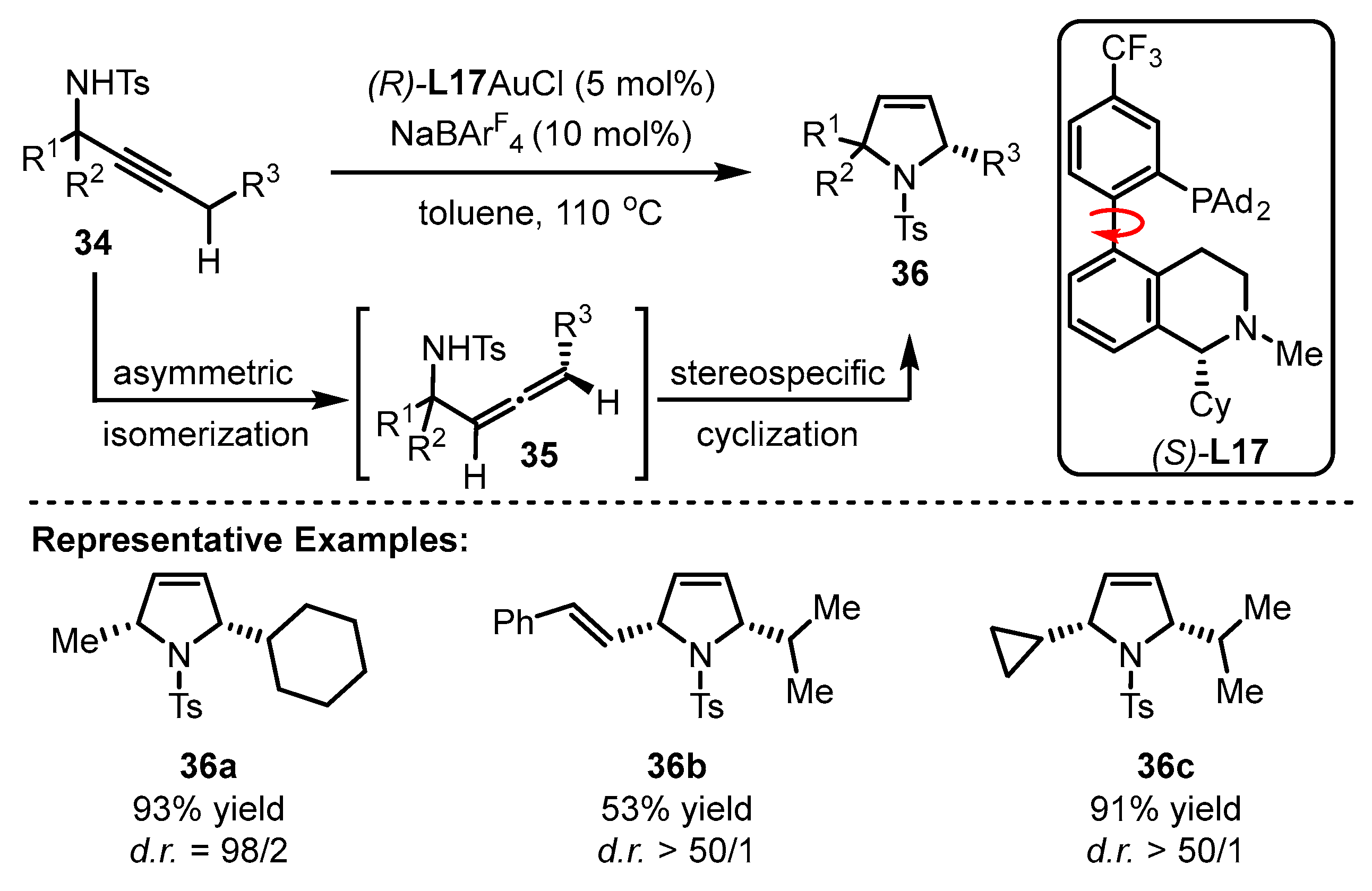

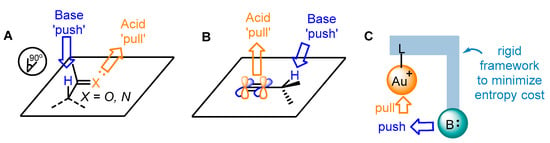

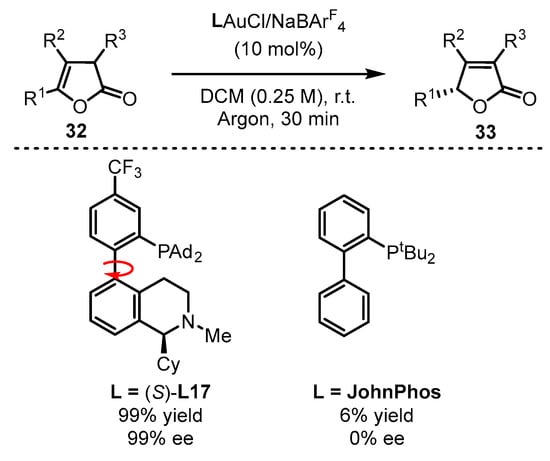

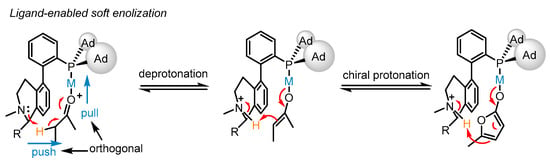

Benefitting from enol chemistry that the α-C−H bond of a carbonyl could be clearly attenuated by the activation from an acid (Lewis acid or protic acid) to the carbonyl group, the Zhang group developed bifunctional phosphine ligands for gold(I)-catalyzed asymmetric reactions [50]. In such reactions, a Lewis acid acts as a ‘pull’, and a weak base functions as a ‘push’. The weak base Et3N (pKa in DMSO, 9.0) can be employed to remove α-H of a carbonyl or an imine group (pKa in DMSO ∼16–30) [51]. Without the utilization of a strong base, the reactions could accommodate more base-sensitive substances (Scheme 12A) [52,53]. From the initial design, it is anticipated that the α-H of a C−C triple bond, i.e., a propargylic proton (estimated pKa in DMSO, >30) [54,55], could be removed by a weak base with the ‘pull’ of a gold(I) catalyst to an alkynyl group (Scheme 12B,C). As a typical example, biphenyl 2-ylphosphines with remote tertiary amino groups for gold(I) catalysis were conceived by Zhang and coworkers (Scheme 13) [52]. As expected, the ligated tertiary amino group could play the role of ‘push’ for the removal of the propargylic proton to initiate new allene reactions, conjugated alkene reactions and aldol-type reactions in alkyne chemistry. With the introduction of asymmetric elements into the ligand, chiral products could be effectively achieved. As per the principle, the authors successfully converted racemic β,γ-butenolides 32 into chiral α,β-butenolides 33 promoted by chiral bifunctional phosphine ligand (S-L17)-ligated gold(I) catalysts (Scheme 13) [56]. In contrast to the JohnPhos-tethered gold(I) catalyst exhibiting 6% product yield and no ee value, the (S)-L17-tethered gold(I) catalyst showed excellent asymmetric catalysis for the γ-protonation process (99% yield and 99% ee).

Scheme 12.

The idea of enol chemistry (A) and the inspiration for the propargyl chemistry (B) and designed approach for bifunctional phosphine ligands in asymmetric gold catalysis (C).

Scheme 13.

Enantioselective isomerization of β,γ-butenolides to chiral α,β-butenolides.

The bifunctional phosphine ligand (S)-L17 features a fluxional biphenyl axis and contains a remote tertiary amino group possessing a vicinal chiral group to remove the α-H of an alkynyl group or a carbonyl group (Scheme 14). Though the biphenyl motif is fluxional, the chiral group can shield the amino group from one conformer to conduct the deprotonation step, which displays the chiral modulation for the process. Moreover, the cooperative ‘pull’ and ‘push’ of the bifunctional phosphine ligand-ligated gold catalysts were rationalized. Upon gold activation to the carbonyl group, the α-H is anticipated to be more acidic, allowing it to be removed by a weak base such as a tertiary amino group. Consequently, the metal enolate generated from soft enolization and the chiral ammonium cation constitute a chiral ion pair. Eventually, the chiral protonation process becomes possible, catering to the principle of soft deprotonation and chiral protonation for the asymmetric isomerization into α,β-butenolides 33 with high enantioselectivity from β,γ-butenolides 32.

Scheme 14.

Enantioselective isomerization of β,γ-butenolides to chiral α,β-butenolides.

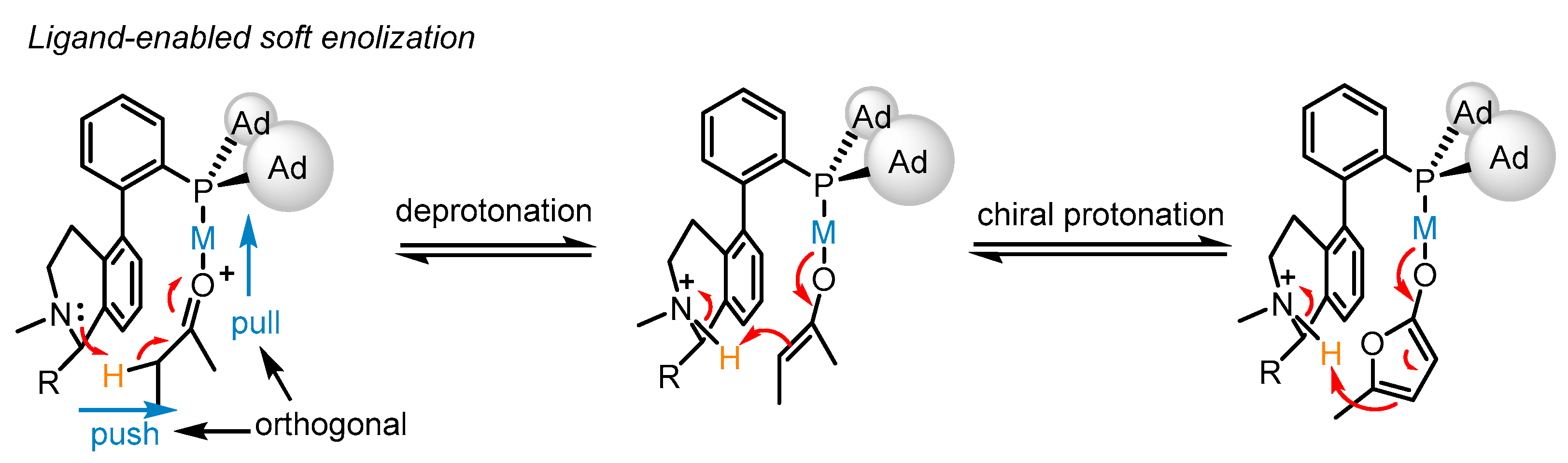

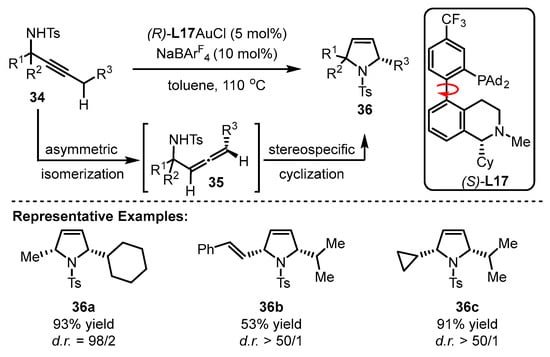

The Zhang group achieved the implementation of a reaction from propargylic sulfonamides into chiral polysubstituted pyrroles via the cooperative catalysis of gold(I) and chiral bifunctional phosphine ligand (S)-L17 (Scheme 15) [57]. The innate diastereoselectivity of this reaction and the ‘matched’ geometry of the (S)-L17-associated gold(I) catalyst with substrates contributed to an excellent diastereo ratio (d.r.) with two chiral centers (2-methyl-5-cyclohexyl pyrrole derivative(36a–36c). The key procedure is the formation of allenes generated from the asymmetric isomerization of sulfonamides. Notably, the asymmetric reaction could tolerate high reaction temperature despite the routine pattern of low temperature to achieve higher enantioselectivity. However, the desired product was obtained in poor yield and low enantioselectivity when (R)-L17 was exposed to the catalytic system.

Scheme 15.

Enantioselective isomerization of β,γ-butenolides to chiral α,β-butenolides.

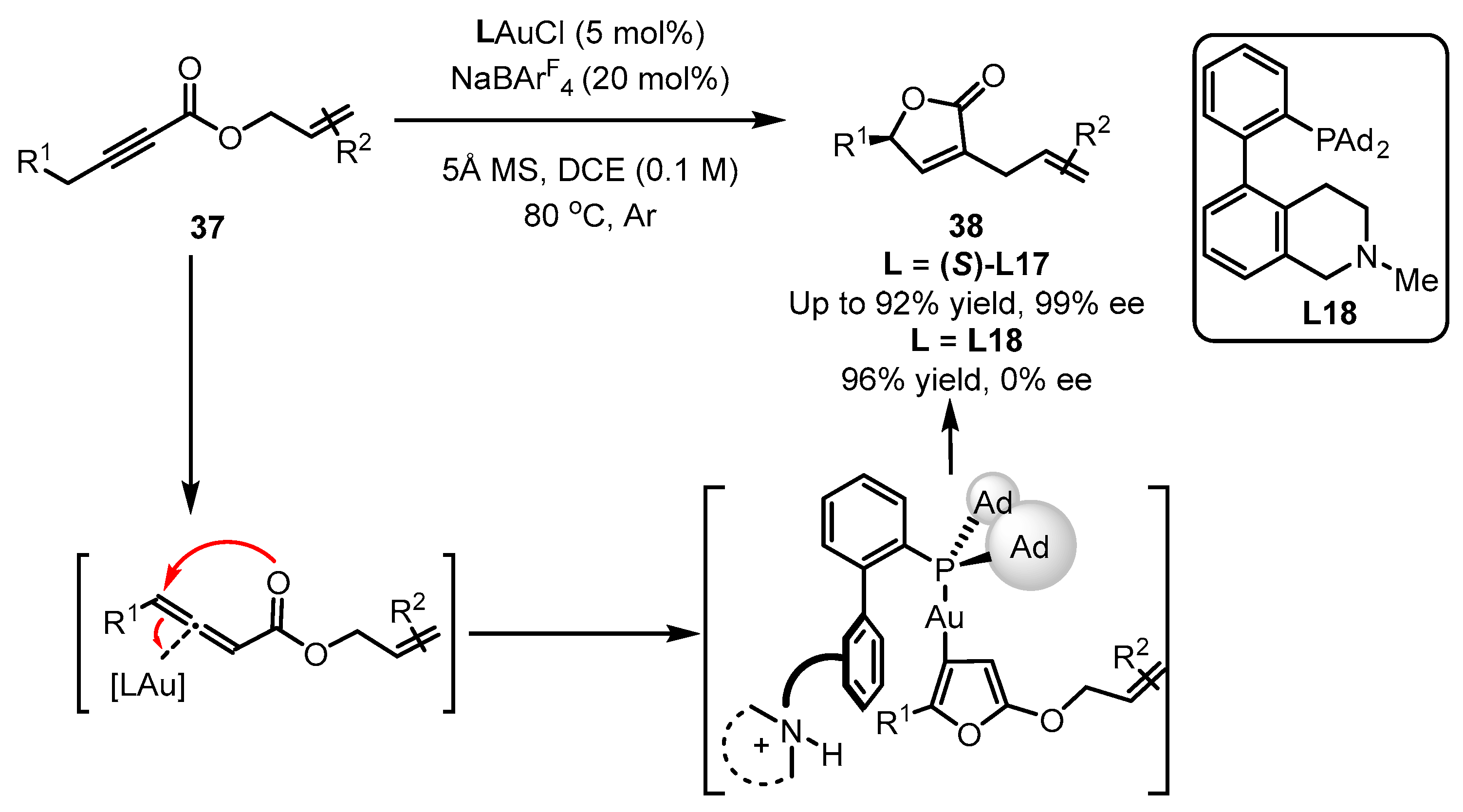

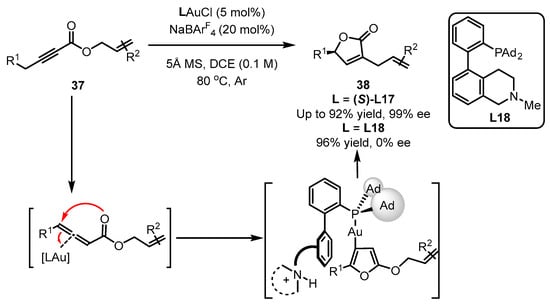

Additionally, the Zhang group reported that the asymmetric version of ynolates 37 to chiral α-Allyl-α,β-butenolides 38 was achieved with the aid of a (S)-L17-ligated gold catalyst (Scheme 16) [58]. As described, in this tandem reaction, the ‘push’ and ‘pull’ processes were involved several times for the generation of an allene intermediate, a furan intermediate and the isomerization product. According to their reports, no ee value was detected for the desired product if a racemic L18 ligand was introduced instead of (S)-L17, despite the excellent yield obtained [59].

Scheme 16.

Asymmetric synthesis of chiral α-Allyl-α,β-butenolides.

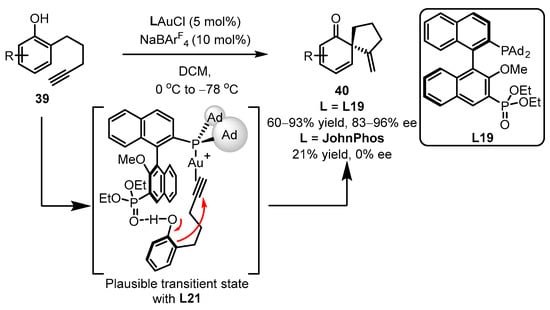

Later, the same group reported gold(I)-catalyzed enantioselective dearomatization of phenol 39 to drug-valuable chiral spirocyclic enone products 40, employing the strategy of gold(I)-chiral ligand cooperation (Scheme 17) [60]. The distal phosphonate presented in the binaphthyl framework L19 displayed better catalytic performance compared to the JohnPhos ligand. It is believed that the H-bond interaction of the phosphate with the hydroxyl group in phenol is the crucial step that dictates asymmetric selectivity and accelerates the dearomatization/cyclization process.

Scheme 17.

Asymmetric synthesis of chiral α-Allyl-α,β-butenolides.

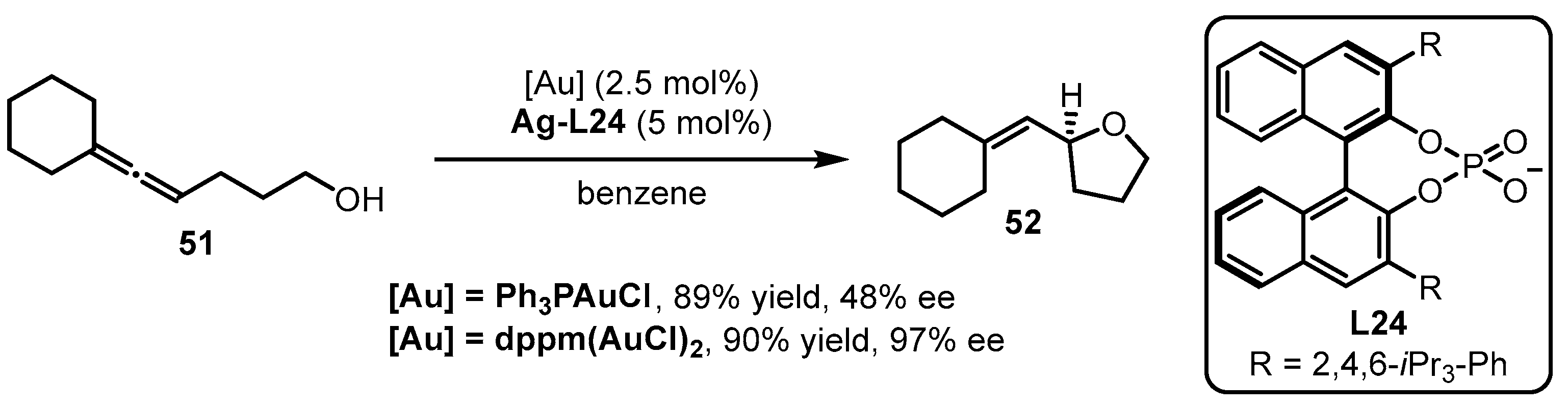

2.5. Biphosphine Ligands

Apart from the above monophosphine ligands, biphosphine ligands have also been developed. Thus, this section intends to present the development of these biphosphine ligands and their applications in gold-catalyzed asymmetric reactions. Although the linear coordination of a ligand with the gold(I) complex generates a single coordination site from the metal center, the asymmetric bisphosphine ligands have been successfully applied to multiple carbon–carbon bond activation reactions. The arguable Au–Au interaction is believed to play a crucial role in modulating chiral transfer due to its subtle tortuosity for the linear coordination way.

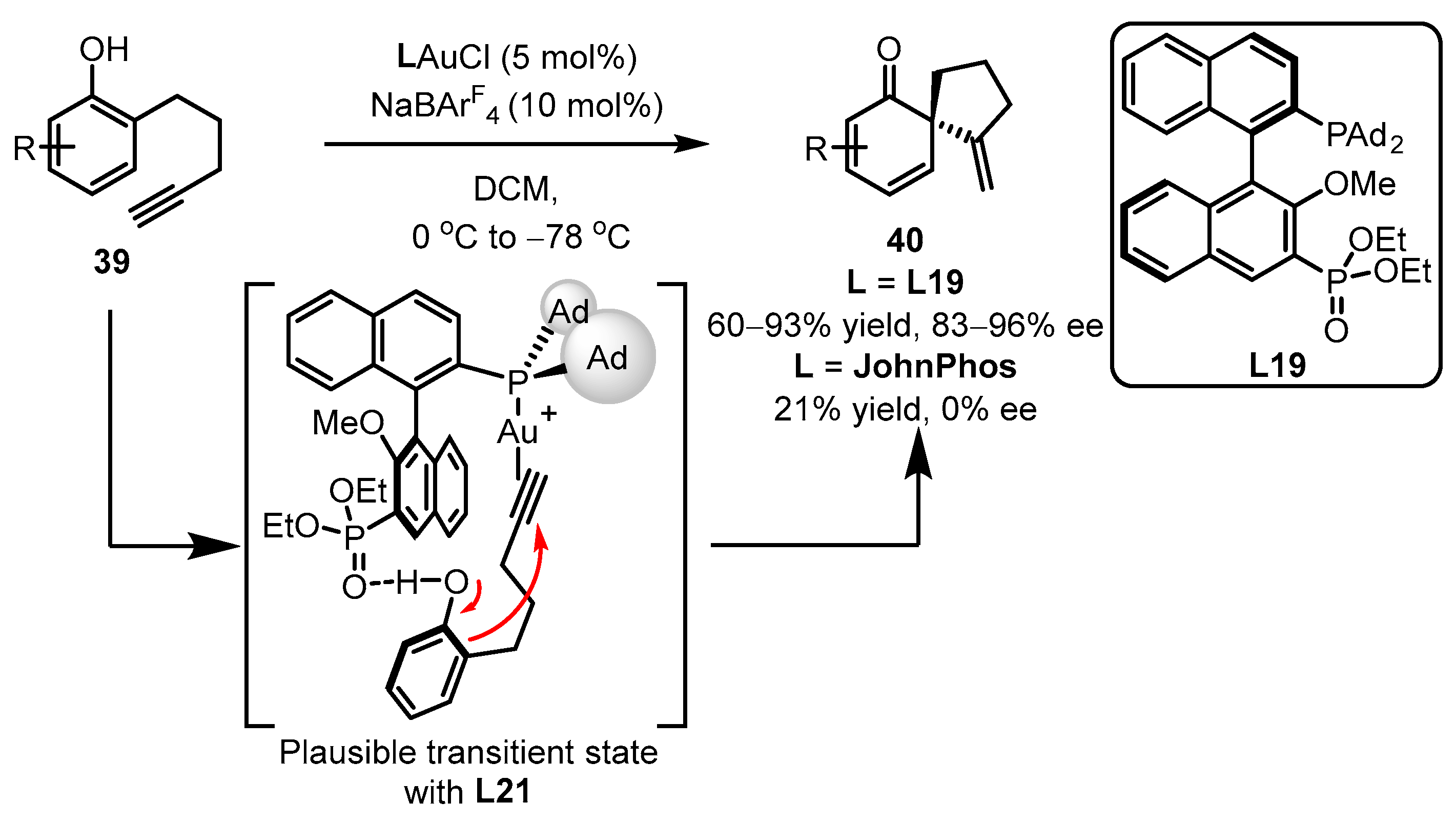

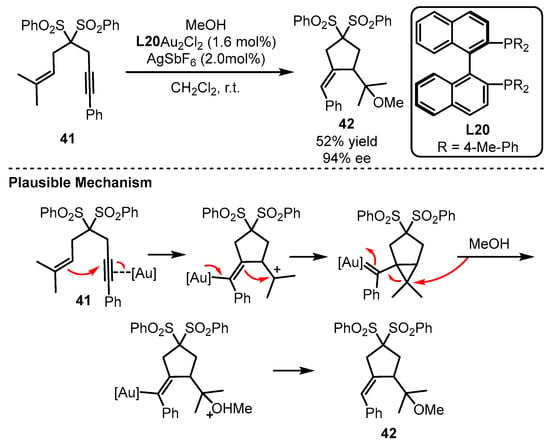

The Echavarren group first discovered the potential of a bisphosphine ligand (L20) in the gold(I)-catalyzed enantioselective tandem cycloisomerization and hydromethoxylation process (Scheme 18) [61]. Remarkably, the addition of a catalytic amount of a silver salt suggested that the monocationic Au species promoted the transformation. The reaction occurred as the electron-rich alkenyl part acted as a nucleophile to attack the chiral gold-activated alkynyl group. After the gold complex feedbacked one pair of electrons to the double bond, the alkenyl group combined with an unstable cation for the formation of a gold carbene species. Following the ring-opening and protodeauration process, the chiral alkoxylation product could be given.

Scheme 18.

Enantioselective bisphosphine-tethered gold(I) catalysis.

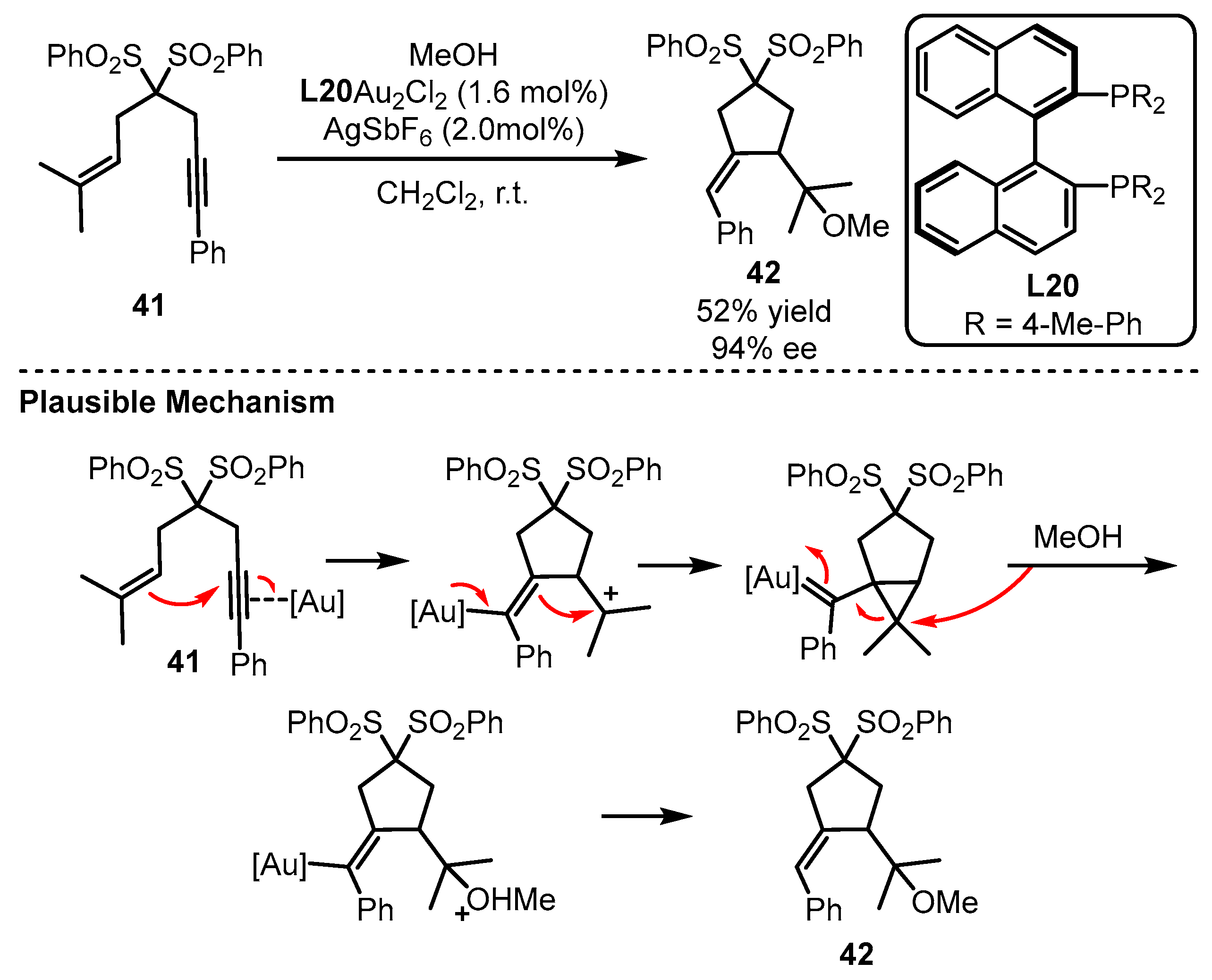

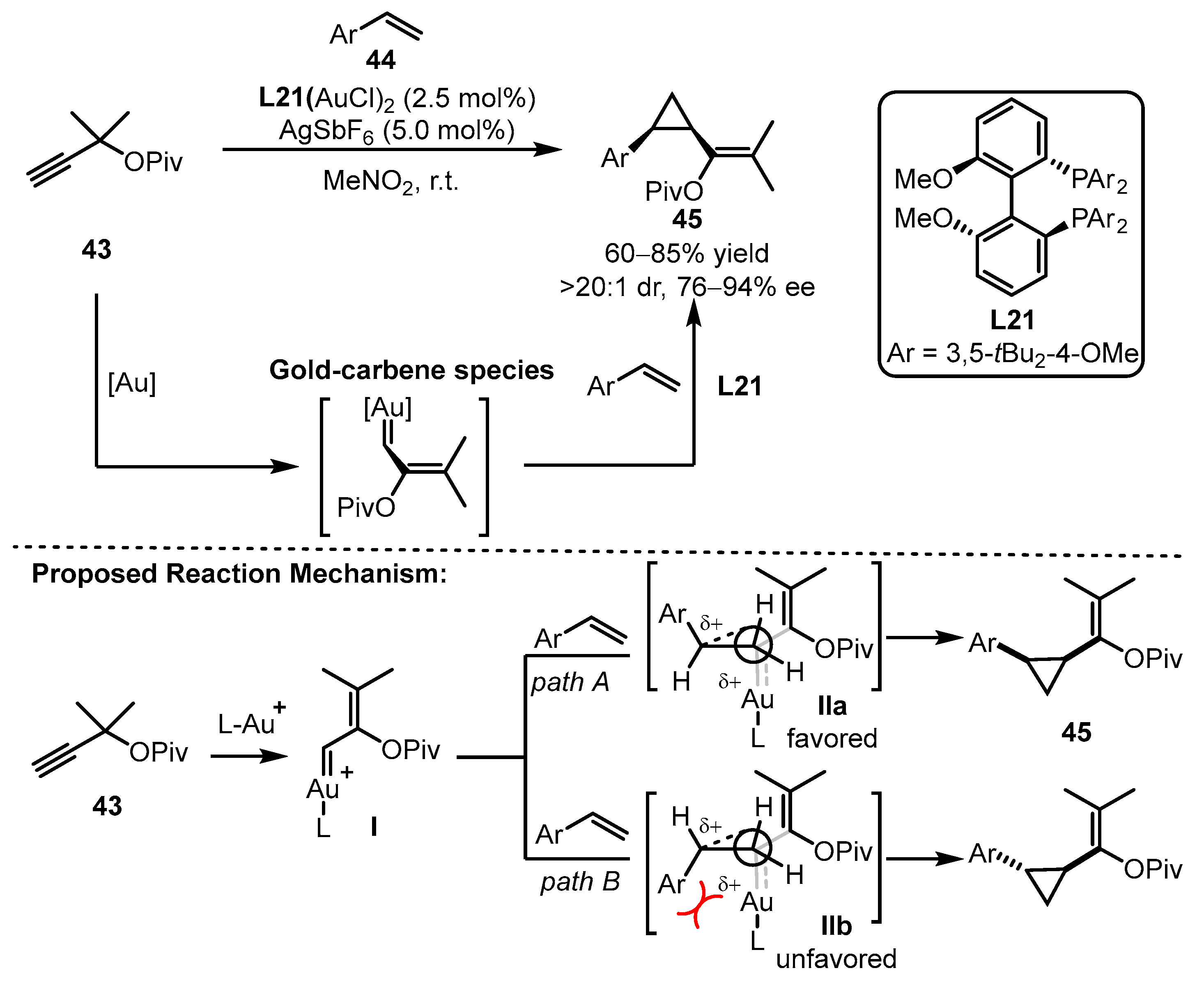

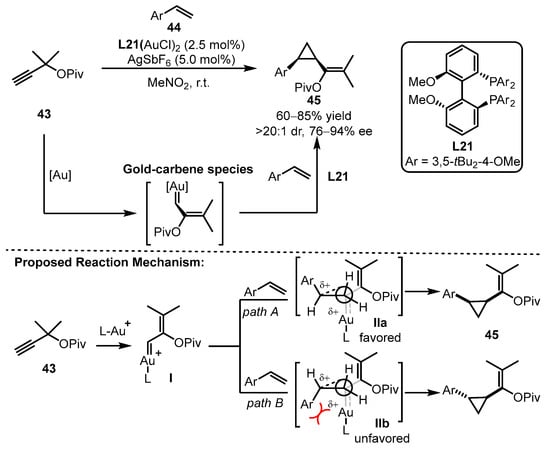

In the same year, the Toste group documented cyclopropantion reactions of alkyne 43 and aryl alkenes 44 using (R)-DTBM-SEGPHOS (L21) as the optimal bisphosphine ligand, affording the desired products 45 with high diasteroselectivity (>20:1) and enantioselectivity (76–94% ee) [62]. In this catalytic process, reactive gold carbene species were involved after a Rautenstrach rearrangement process. The proposed mechanism suggests that substituents from alkenes will intrinsically interact with the ligated gold complex (IIb), which disfavors the formation of trans-substituted cyclopropanes. Thus, the cis-selectivity was easily offered in most cases. However, the sterically less hindered BINAP ligand could not efficiently induce the transfer of chirality (Scheme 19), as observed from the ligand screening data.

Scheme 19.

Asymmetric cyclopropanation of alkynes and aryl alkenes.

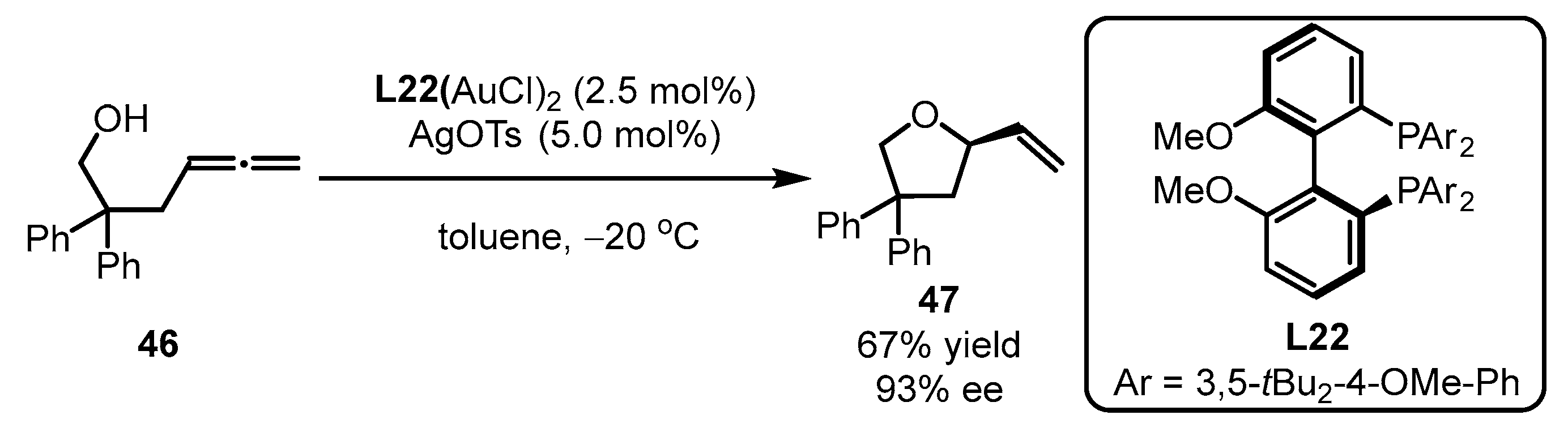

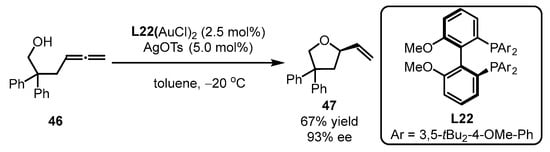

Additionally, bisphosphine-containing gold complexes were also applicable to asymmetric alkoxylation of allenes, as illustrated by Widenhoefer and coworkers (Scheme 20) [63]. Specifically, bisphosphine ligand L22 was smoothly accommodated with allene 46, providing (R)-4,4-diphenyl-2-vinyltetrahydrofuran 47 with a moderate yield and high enantioselectivity (67% yield, 93% ee).

Scheme 20.

Gold(I)-catalyzed asymmetric alkoxylation of allenes.

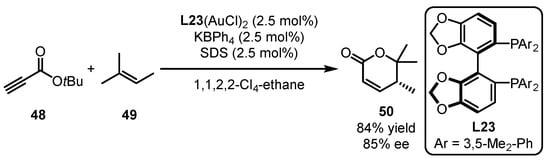

Shin and coworkers applied a chiral bisphosphine ligand (L23) derived from the SegPhos backbone to a gold-catalyzed enantioselective intermolecular [4 + 2] cycloaddition of propiolate 48 with substituted alkene 49 (Scheme 21) [64]. α, β-Unsaturated δ-lactone 50 was detected as the main product along with several diene side-products generated from metathesis and conjugate addition. Furthermore, the use of 1,1,2,2-Cl4-ethane as a solvent and the addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) as a surfactant were significant for enhancing chemoselectivity and mediating chiral transfer.

Scheme 21.

Dimeric gold catalyst-promoted enantioselective [4 + 2] cycloaddition.

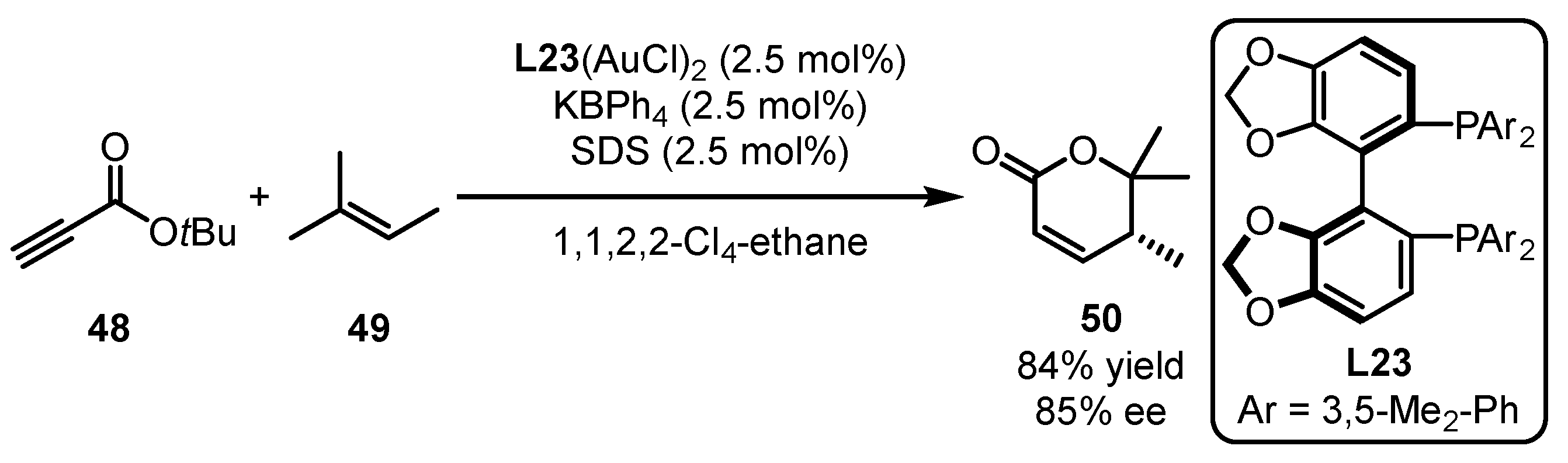

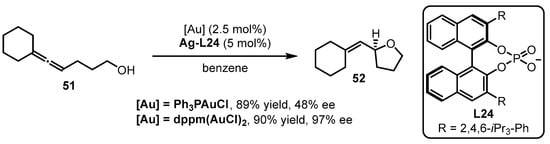

2.6. Chiral Counterions Derived from Chiral Phosphoric Acids

The phosphine-containing organic ligands are summarized from Section 2.1 to Section 2.5. In this section, a unique type of phosphine ligand, referred to as chiral phosphoric acid-derived chiral counterion ligands, is discussed. The development of asymmetric gold catalysis via chiral ion pairs between cationic gold catalysts and chiral counterions is a successful strategy to confer to the enantioselectivity of gold-catalyzed reactions [65]. The Toste group explored the counterion strategy in gold catalysis for the intramolecular asymmetric hydroalkoxylation of allenes [66]. To achieve high enantioselectivity in the reactions, the “matched” effect of a phosphine-associated gold catalyst with a chiral silver salt should be considered (Scheme 22). Specifically, the cooperation of bis(chlorogold) bis(diphenylphosphino)methane [dppm(AuCl)2] with Ag-L24 prompted the asymmetric cyclization of allenol 51 to tetrahydrofuran 52 with excellent yield and enantioselectivity. On the contrary, inferior results were provided when Ph3PAuCl was utilized instead of dppm(AuCl)2.

Scheme 22.

Chiral counterion-induced asymmetric cyclization of allenol 51.

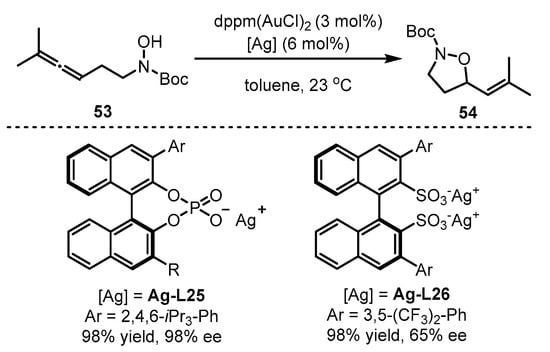

On the other hand, the chiral counterion induction approach could be extended to enantioselective cyclization of alkynyl hydroxylamine 53 (Scheme 23) [67]. The ‘matched’ system of dppm(AuCl)2 with Ag-L25 could induce efficient chirality mediation for the formation of vinyl isoxazolidine 54. As an alternative, if Ag-L25 was displaced with Ag-L26, the enantioselectivity of the reaction decreased dramatically.

Scheme 23.

Gold(I)-catalyzed asymmetric formation of vinyl isoxazolidines.

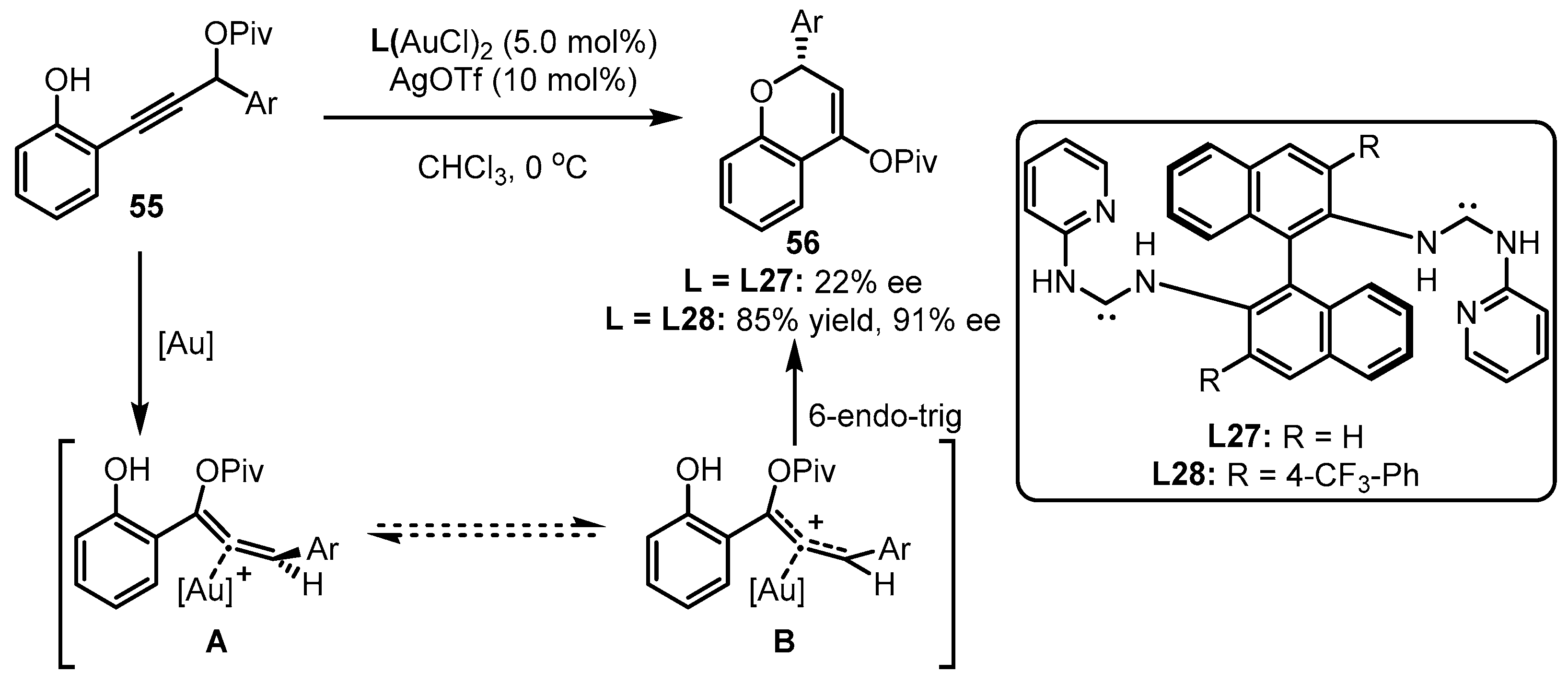

2.7. Chiral Carbene Ligand

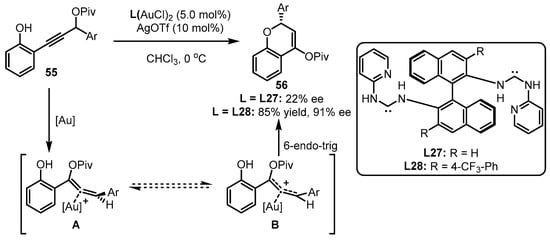

Apart from the above phosphine-containing organic ligands, chiral carbene ligands have also been developed for asymmetric gold catalysis. As the distinct performance of gold(I)-carbene complexes in terms of chemoselectivity and regioselectivity in carbophilic activation, chiral carbene ligand-involving gold(I) catalysts were also elaborately designed to conduct a set of asymmetric transformations [68]. Considering the repertoire of an electron-rich group in offering the stability of an allene intermediate, Toste and coworkers conceived that, compared to phosphite-tethered gold complexes, the more electron-donating carbene-coordinated gold(I) catalysts could facilitate 6-endo-trig cyclization of propargyl ester 55 in a more efficient manner (Scheme 24) [69]. Undoubtedly, incorporation of different substituents into the ligand skeleton is crucial for the effective enantioselectivity control. As observed, ligand L28 bearing a 4-CF3 group was identified as an excellent auxiliary for achieving 85% yield and 91% ee, while the unsubstituted ligand (L27) triggered an inferior result.

Scheme 24.

Asymmetric [3 + 3] reaction catalyzed by (acyclic diaminocarbene)-gold(I) complexes.

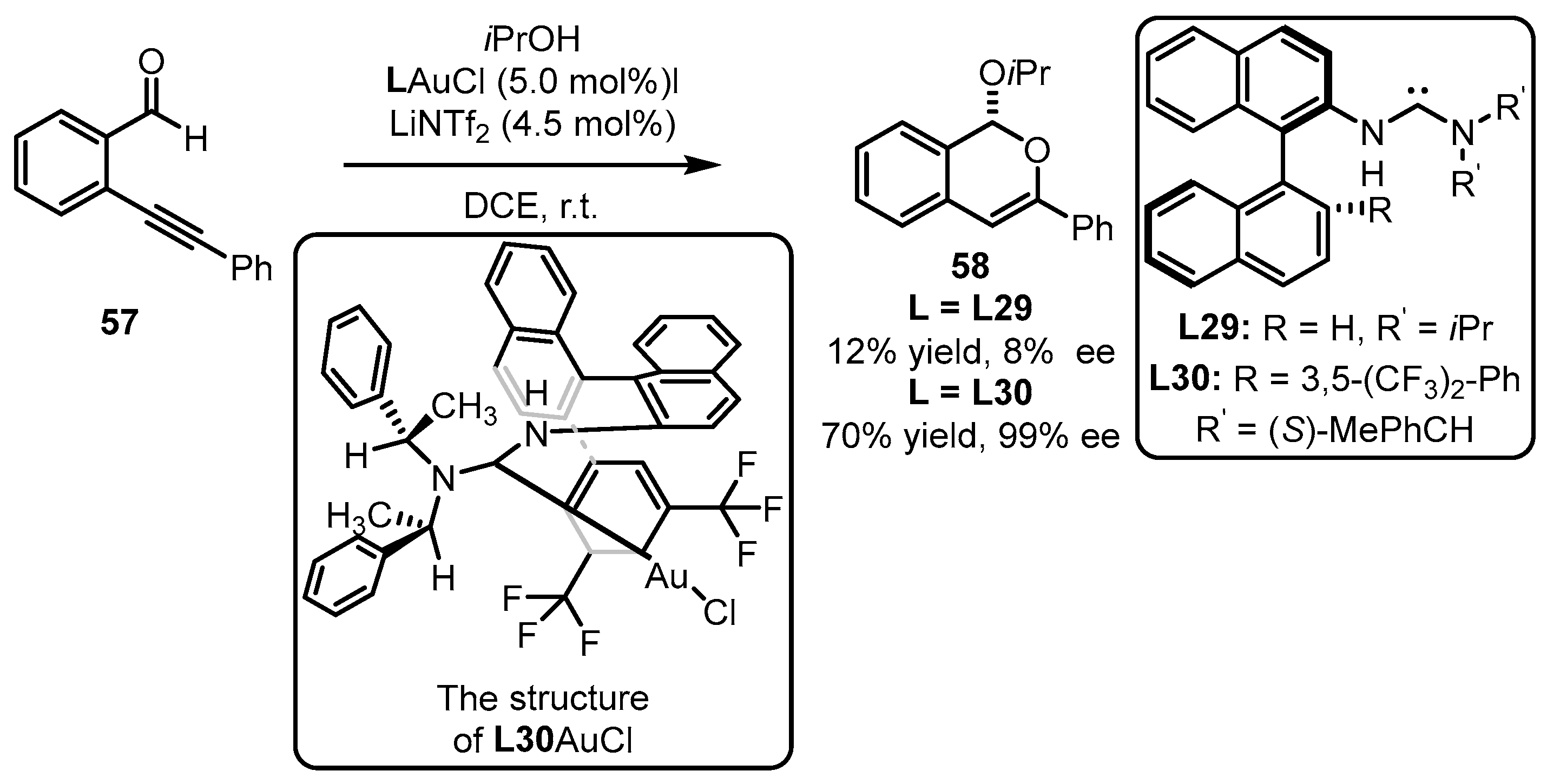

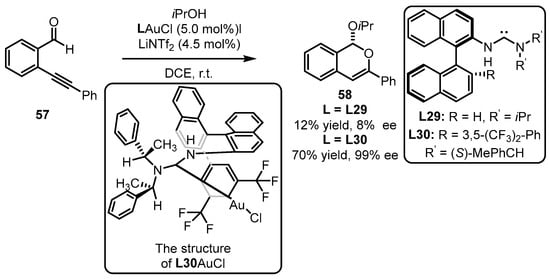

Subsequently, Slaughter and coworkers developed impressive monodentate acyclic diaminocarbene ligands (L29, L30) for the enantioselective gold(I) catalysis based on the comprehension of the chiral (carbene)gold template (Scheme 25) [70]. The designed monodentate gold(I) complexes were introduced into tandem cyclization and nucleophilic addition of ortho-alkynylbenzaldehyde 57. Although L29 mismatched the catalytic system with a detrimental result, the modified ligand (L30) was found to be an excellent promoter for the formation of sterogenic 1H-isochromene 58 (70% yield, 99% ee). It appeared that the secondary interactions generated from the electrostatic attraction between the decorated amino group and suitable substrate promoted the efficient construction of the chiral motif. The crystal structure of L30AuCl reveals that the rotation of the gold complex with the substrates is restricted due to the interaction between the gold atom and the aryl ring (3,5-(CF3)2-Ph in binaphthyl skeleton) as well as the π–π stacking between a phenyl (in the amino part) and a naphthyl unit. This restriction facilitates chirality control during the cyclization process.

Scheme 25.

Tandem cyclization reaction catalyzed by (acyclic diaminocarbene)gold(I) complexes.

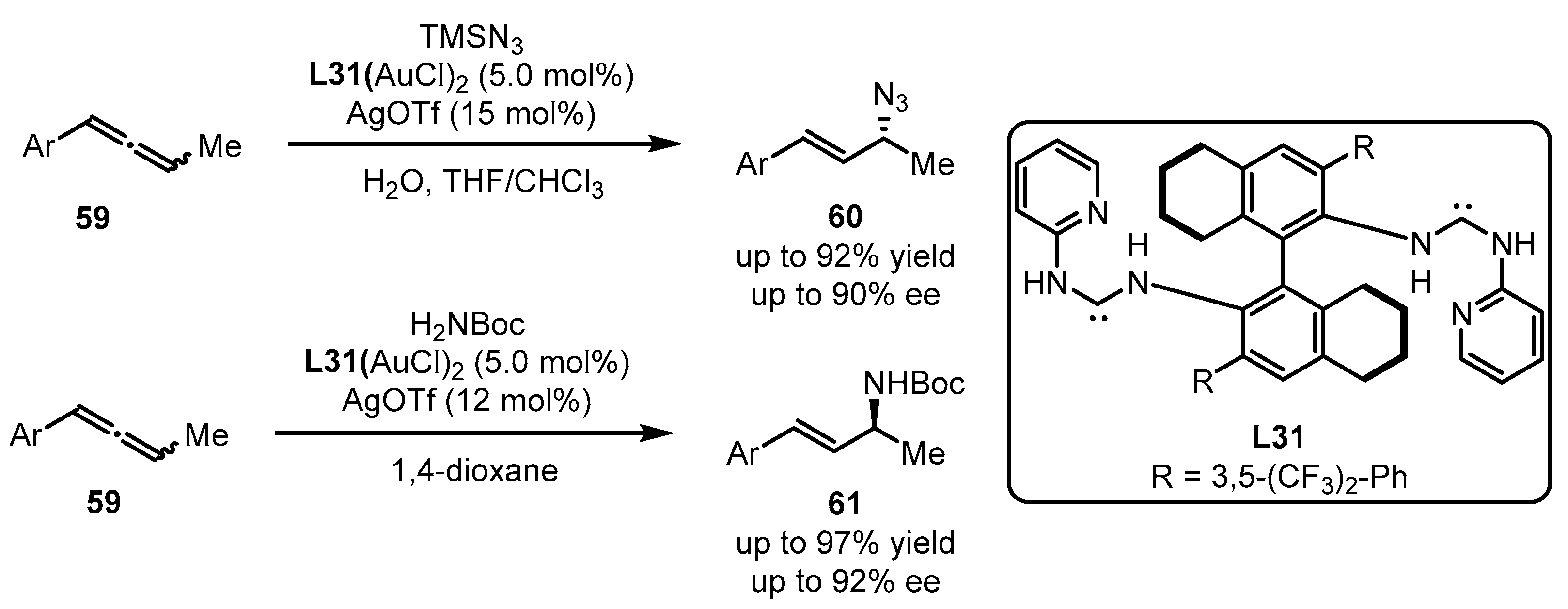

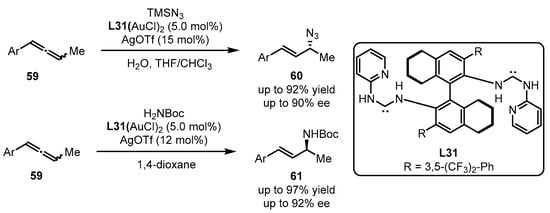

Acyclic diaminocarbene gold(I) complexes were further applied to the asymmetric hydroazidation and hydroamination of allenes 59 by the Toste group (Scheme 26) [71]. The introduction of carbene ligand L31 resulted in excellent yield and ee values, whereas the other explored ligands failed to dictate the chirality formation. It is noteworthy that, with L31 as a ligand, opposite conformers can be obtained only by using different nucleophiles (TMSN3 for the formation of 60 and H2NBoc for the generation of 61).

Scheme 26.

Chiral carbene-tethered gold catalyzed nucleophilic addition of allenes.

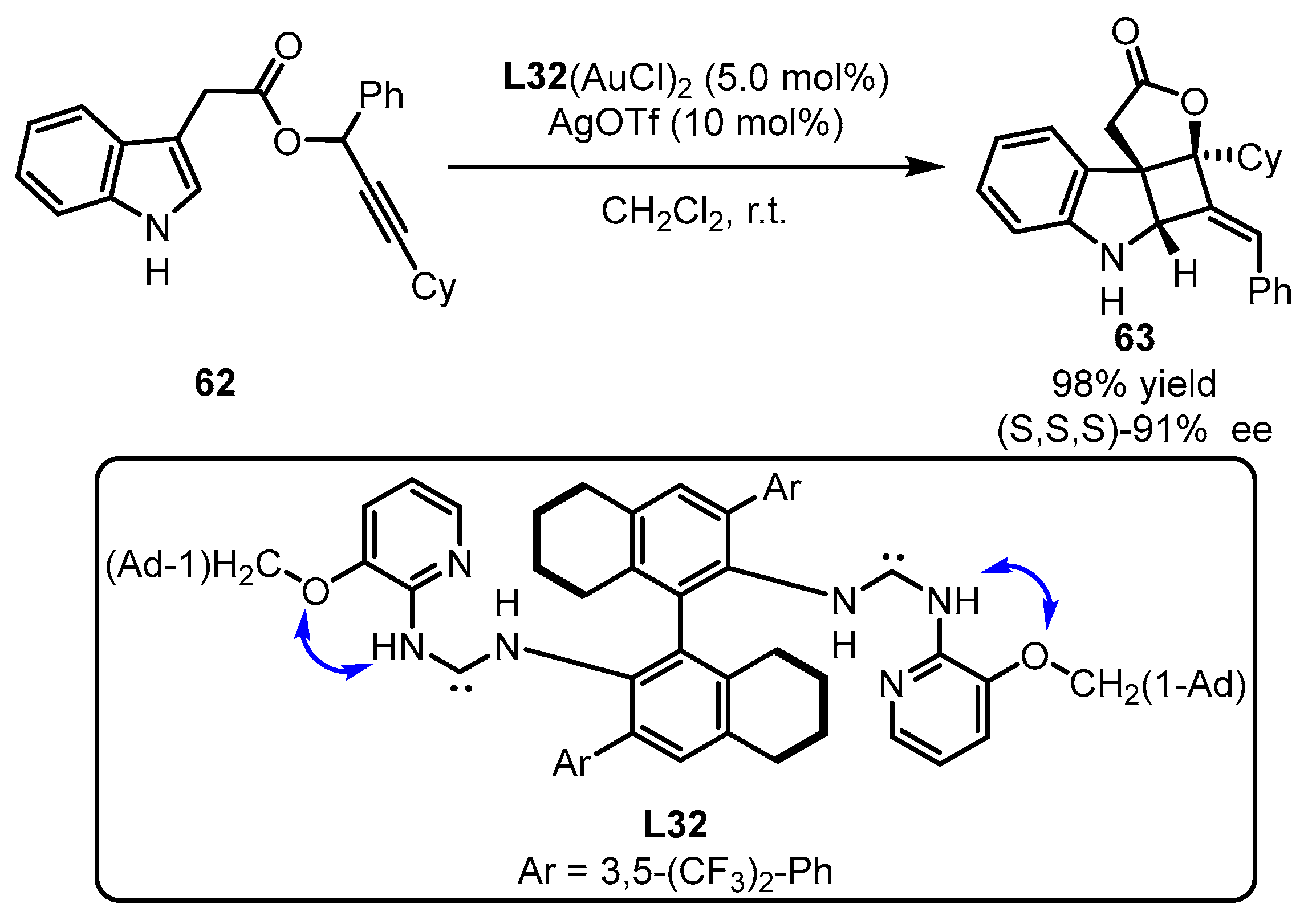

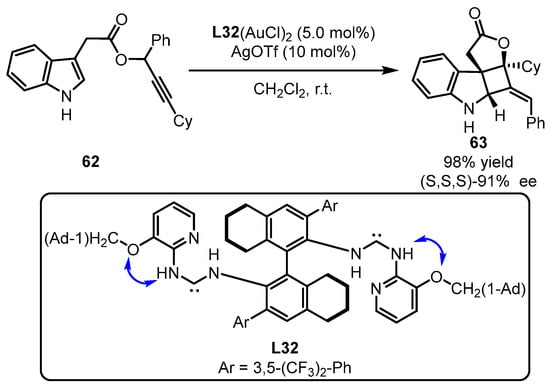

The Toste group subsequently challenged enantio-induction of tandem [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement and [2 + 2]-cyclization of propiolate 62 containing an indolyl group with the aid of computation (Scheme 27) [72]. The bulky L32-tethered gold(I) complex was identified as the optimized catalyst for chirality transformation through the construction of three chiral carbon centers. The computational studies suggested that the intramolecular H-bond formation from vicinal amino NH and O facilitated the mediation of chirality achievement.

Scheme 27.

(Acyclic diaminocarbene)gold(I) complexes for challenging chirality formation.

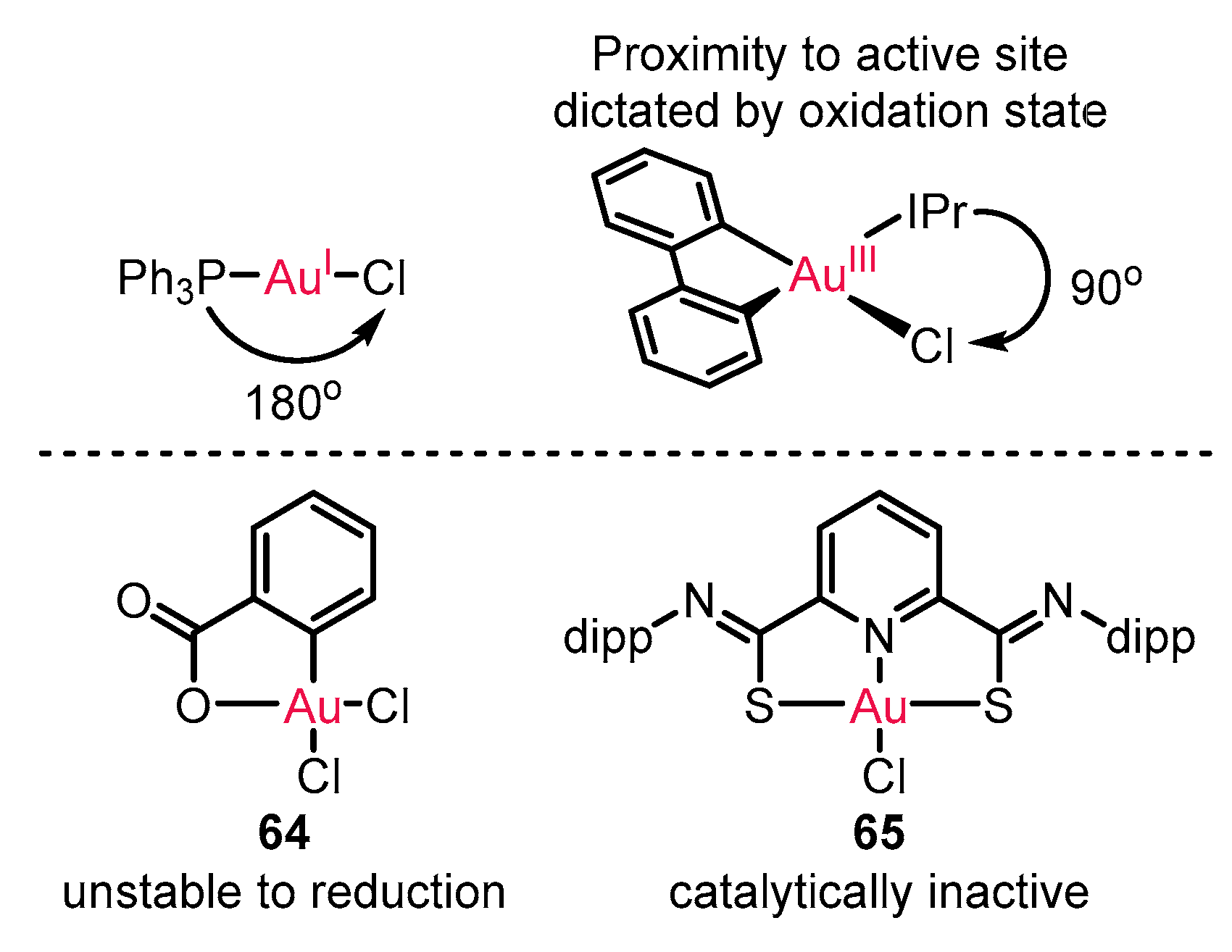

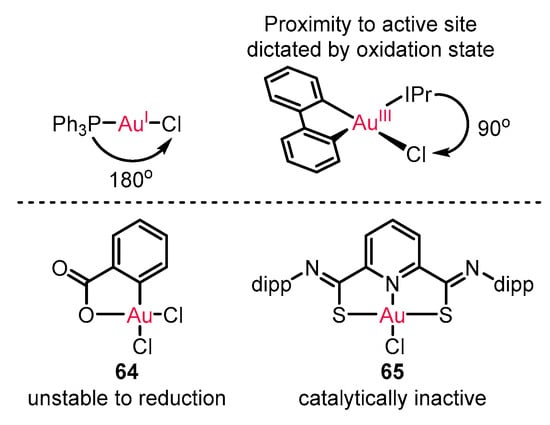

2.8. Cyclometalated X-Y (X = C, O; Y = C, O) Ligand Frameworks

Enantioselective reactions with gold(I) catalysis have been extensively developed [73,74,75], as also illustrated in all the above examples. However, the linear geometry of gold(I) catalysts restricts its ability to modulate chirality formation (Scheme 28). On the other hand, the square-planar geometry of gold(III) catalysts introducing cyclometalated ligand frameworks is expected to avoid the restriction owing to the potential mediation from lithered chiral ligand proximal to the reactive center. However, the unstable risk of gold(III) complex 64 for reduction to gold(I) or unreactive state of traditional gold(III) catalyst 65 impeded its application in enantioenriched catalysis [76,77,78].

Scheme 28.

The innate difference of gold(I) and gold(III) catalytic mode.

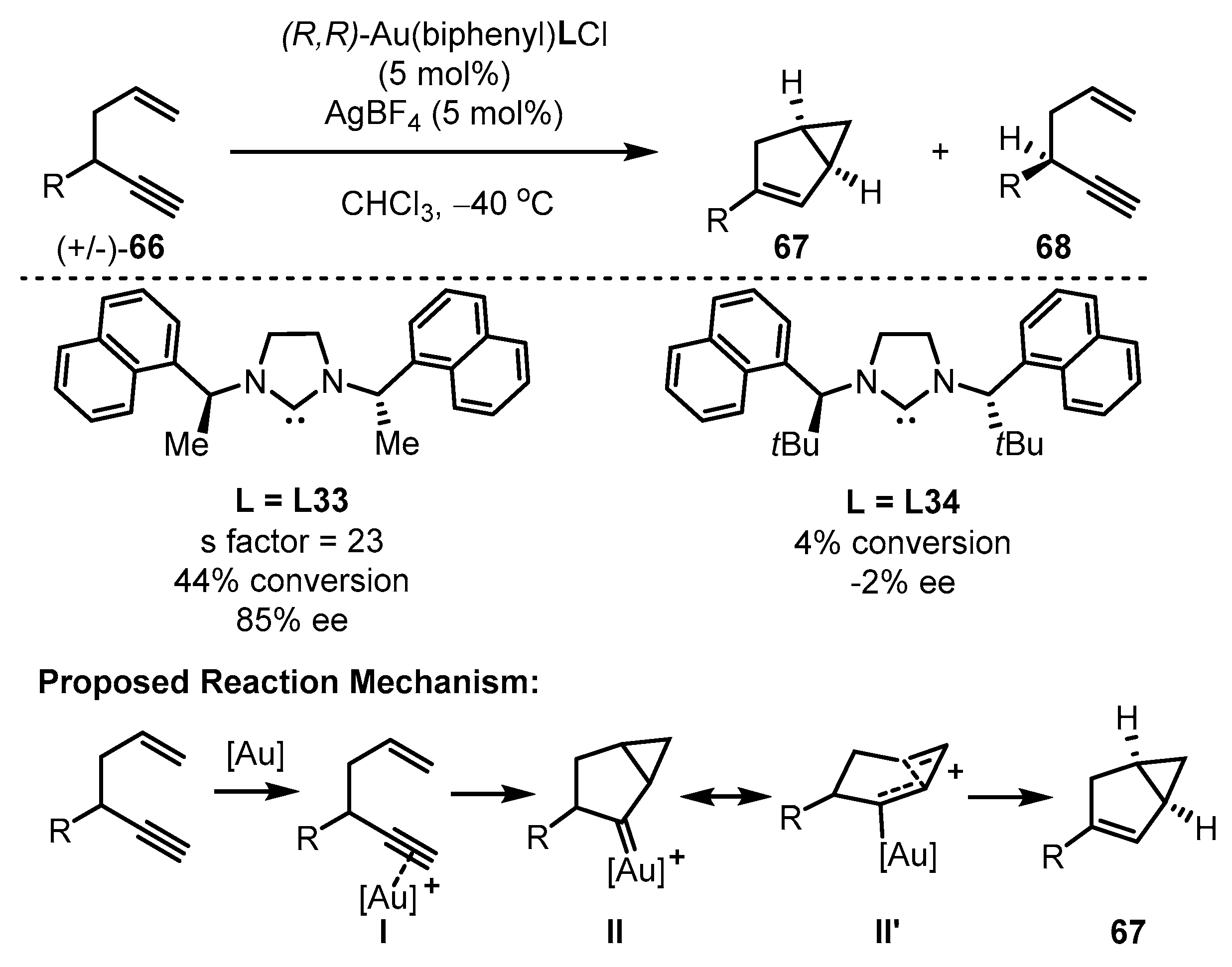

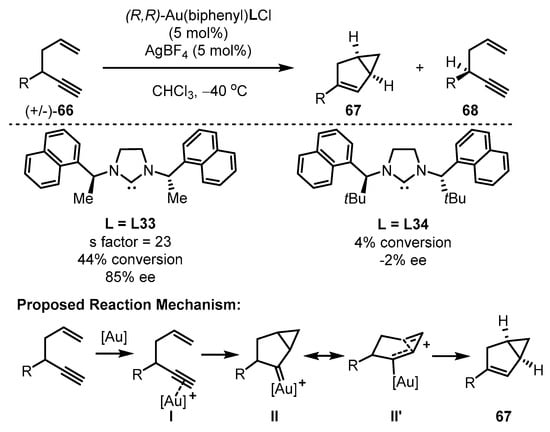

To address the above-mentioned limitations of traditional gold(III) catalysts, the Toste group developed a cyclometalated C−C ligand framework to stabilize the gold(III) cationic species [79]. This framework possesses powerful catalytic activity while maintaining a stable structure that facilitates effective reaction turnover (Scheme 29). A chiral N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligand was positioned in the square vicinal to the reaction center to induce chiral formation. The resulting elaborated chiral NHC-tethered gold(III) catalysts displayed varied activity and divergent enantioselectivity in the cycloisomerization of enynes 66. Notably, (R,R)-gold(III)(biphenyl)L33Cl selectively facilitated the conversion of the (R)-enyne substrate into bicyclic adducts 67 in moderate conversion (44%) and good ee value (85%), whereas the gold(III) catalyst bearing L34 showcased a sluggish result (4% conversion, −2% ee) [80]. Meanwhile, (S)-enyne substrate 68 was provided along with the enantioconvergent cyclization via kinetic resolution. As described above, the reaction is initiated by the effective coordination of the gold complex with the triple bond of the enyne substrates, leading to the formation of complex I. Following this, a concerted cycloaddition took place, resulting in the generation of gold carbenes (II and II’). Subsequently, the bicyclic scaffold is furnished with the migration of α–H and the release of the catalyst from the system.

Scheme 29.

The chiral gold(III)-catalyzed asymmetric cycloisomerization of enynes.

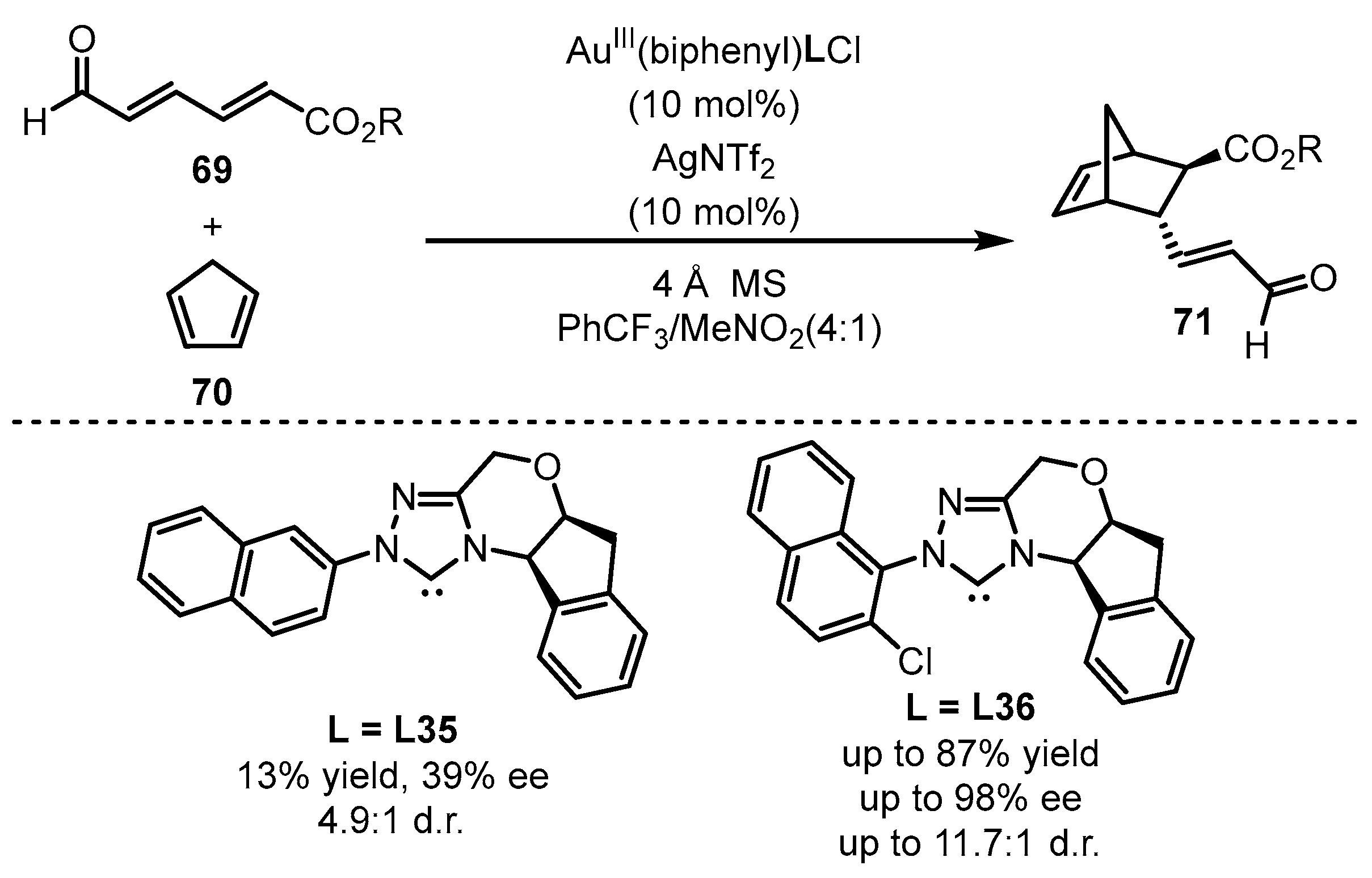

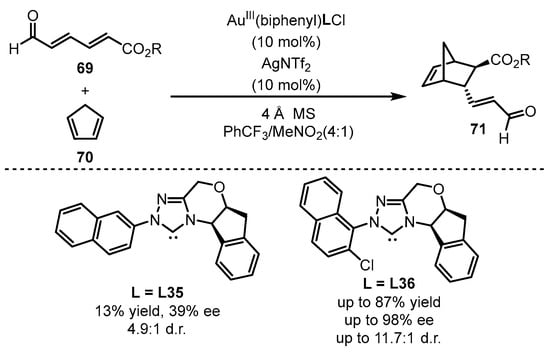

The square-planar chiral gold(III) catalysts were further applied to the asymmetric cycloaddition of 2,4-hexadienals 69 and cyclopentadiene 70 to synthesize valuable chiral bicycles 71 (Scheme 30) [81]. Different NHC ligands were prepared for the formation of chiral gold(III) catalysts. As observed, 1-naphthyl substituted NHC (L36) demonstrated superior chiral induction compared with the 2-naphthyl counterpart (L35), which suggests that a sterically bulky ligand is beneficial for this catalytic transformation.

Scheme 30.

The chiral gold(III)-catalyzed enantioselective Diels–Alder reaction.

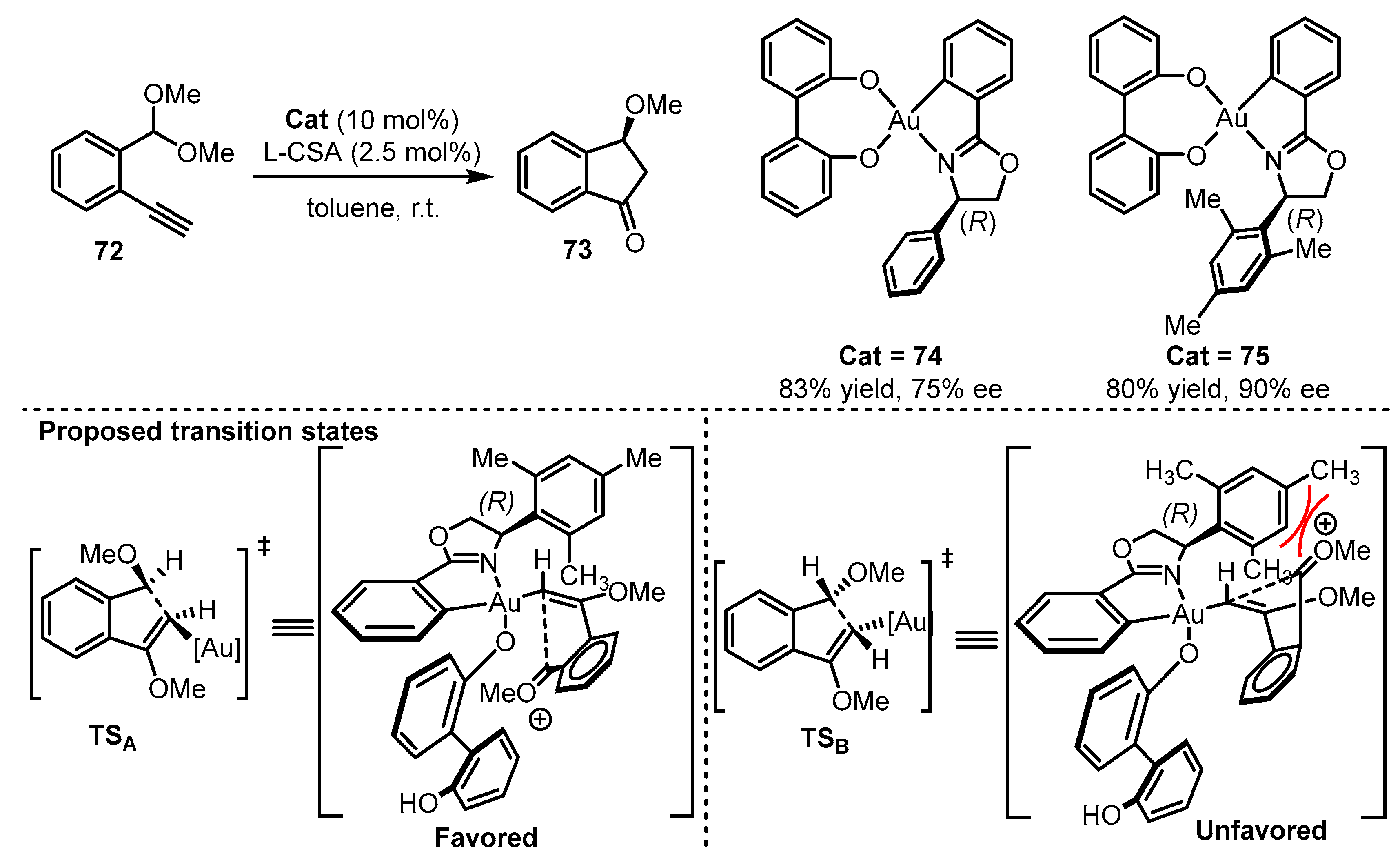

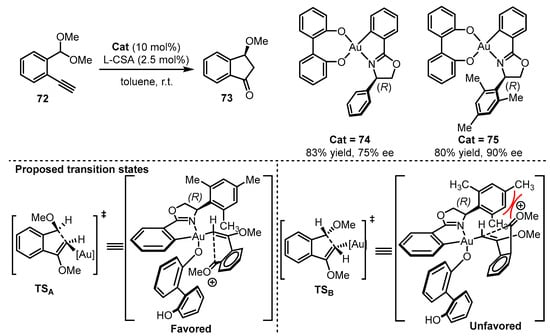

Subsequently, Wong and coworkers synthesized O,O-chelated cyclometalated oxazoline gold(III) catalysts [78]. When the chiral O,O-chelated backbone was introduced into the gold(III) complexes, the combination of gold(III) catalyst (74 or 75) and L-camphorsulfonic acid (L-CSA) effectively initiated the carboalkoxylation reaction of alkyne 72 for the formation of 3-methoxyindanone 73 (Scheme 31) [82]. From the proposed transition state, the steric hindrance from the 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl group in the oxazoline part would be significant. This hindrance creates clear repulsion towards the substrate in the unfavored TSB, which contributed significantly to the improvement of enantioselectivity (75% ee for 74 vs. 90% ee for 75).

Scheme 31.

Asymmetric O,O-chelated cyclometalated oxazoline gold(III) catalysis.

3. Application of Asymmetric Gold Catalysis

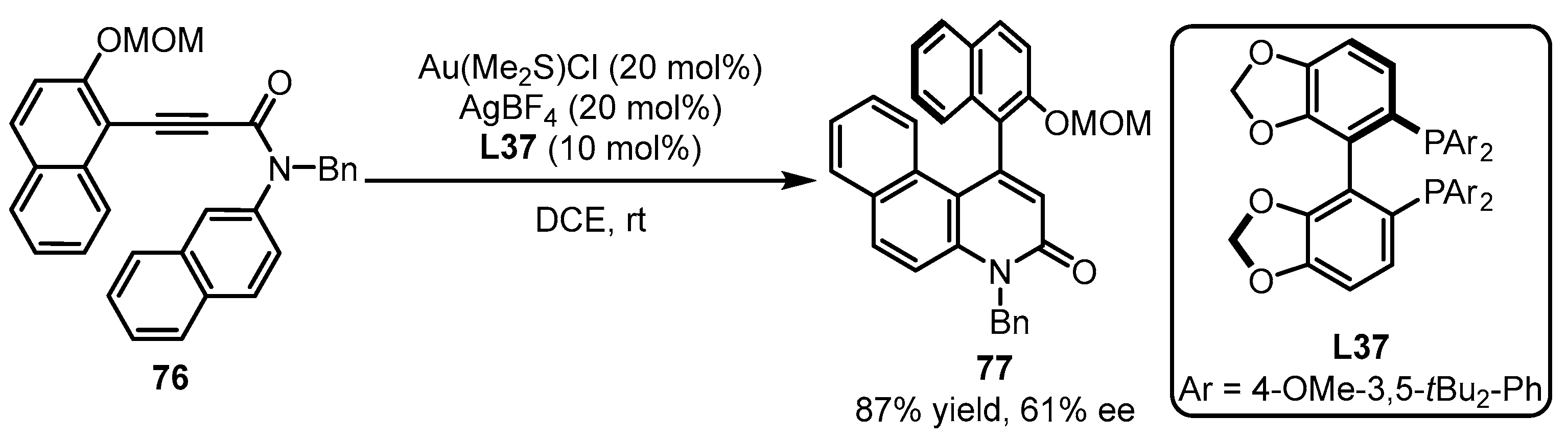

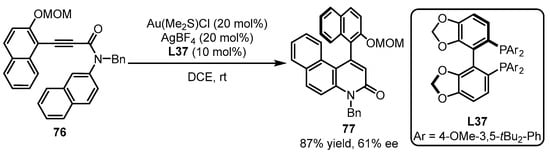

Axially chiral biaryl compounds exert important roles in natural product synthesis. The asymmetric hydroalkenylation strategy for the synthesis of axially chiral N-hetero-biaryl compound 77 was first achieved by Tanaka and coworkers utilizing chiral bisphosphine L37 as the ligand for asymmetric gold catalysis (Scheme 32). This methodology, though achieving a moderate ee value, opened the avenue for the enantioselective formation of various axially chiral polyaryl molecules.

Scheme 32.

Bisphosphine-tethered gold catalyzed asymmetric hydroalkenylation.

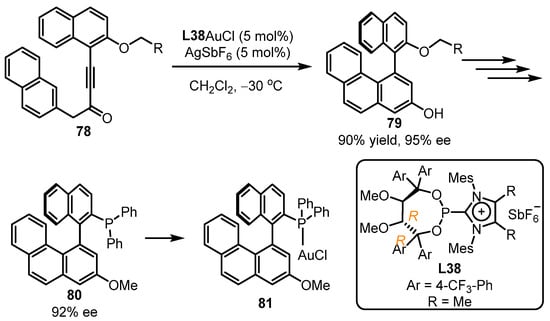

Axially chiral phosphines have been demonstrated to be an important class of chiral ligands. Aiming at the chiral non-C2-symmetric BINOL ligand-directed synthesis, the Alcarazo group developed the asymmetric arylation of naphthyl alkynone 78 into enantiopure 1,1′-binaphthalene-2,3′-diol 79 (90% yield, 95% ee) with the assistance of the phosphonite L38-tethered gold(I) catalyst (Scheme 33). To ensure higher catalytic activity of the gold complex, the positively charged heterocyclic rest was cooperated into the ligand, which had a strong electron-withdrawing character [83]. After several steps, a new axially chiral phosphine 80 with a 92% ee value was provided, which could be used for the formation of new chiral gold compounds 81.

Scheme 33.

Atropselective synthesis of non-C2-symmetric BINOL.

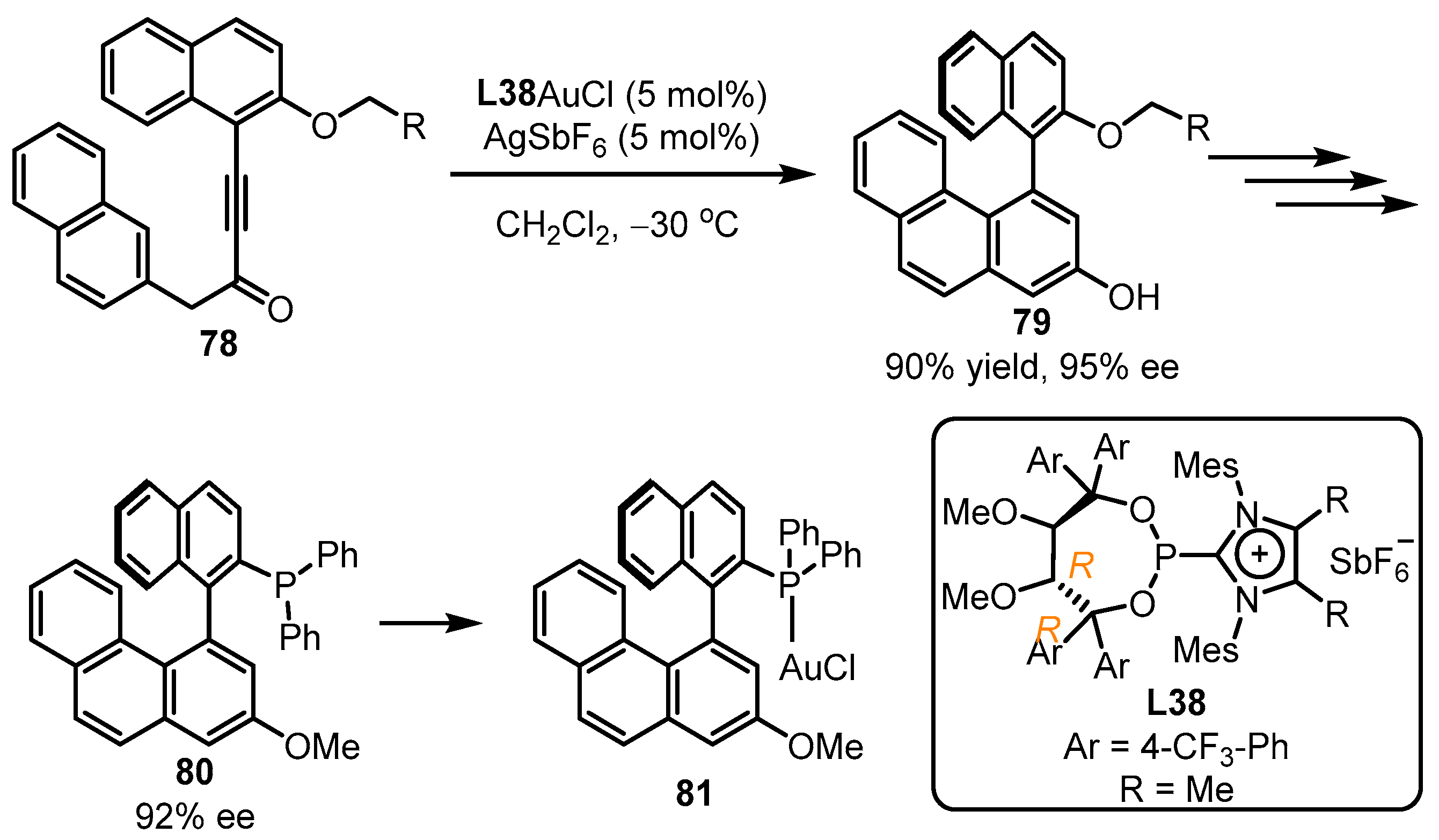

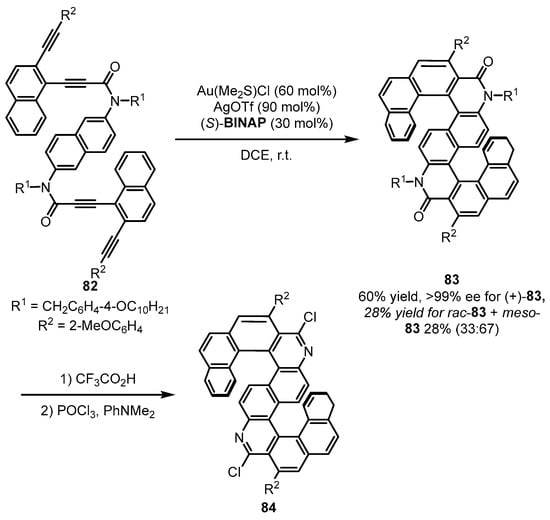

Helicenes have been extensively studied as functional organic materials due to their potential photophysical properties. In the asymmetric gold-catalyzed arylation of tetraalkynes 82 (Scheme 34), (S)-BINAP was introduced to achieve the desired S-shaped double azahelicenes [84]. The tandem control for chiral formation posed challenges for diasteroselectivity and enantioselectivity. The desired enantio-pure (+)-83 and separable (rac)-83 and (meso)-83 could be smoothly produced. Gratifyingly, the desired azahelicenes 84 with enhanced circularly polarized luminescence were readily given after another two steps.

Scheme 34.

Gold-(S)-BINAP complex promoted enantioselective arylation of alkynes.

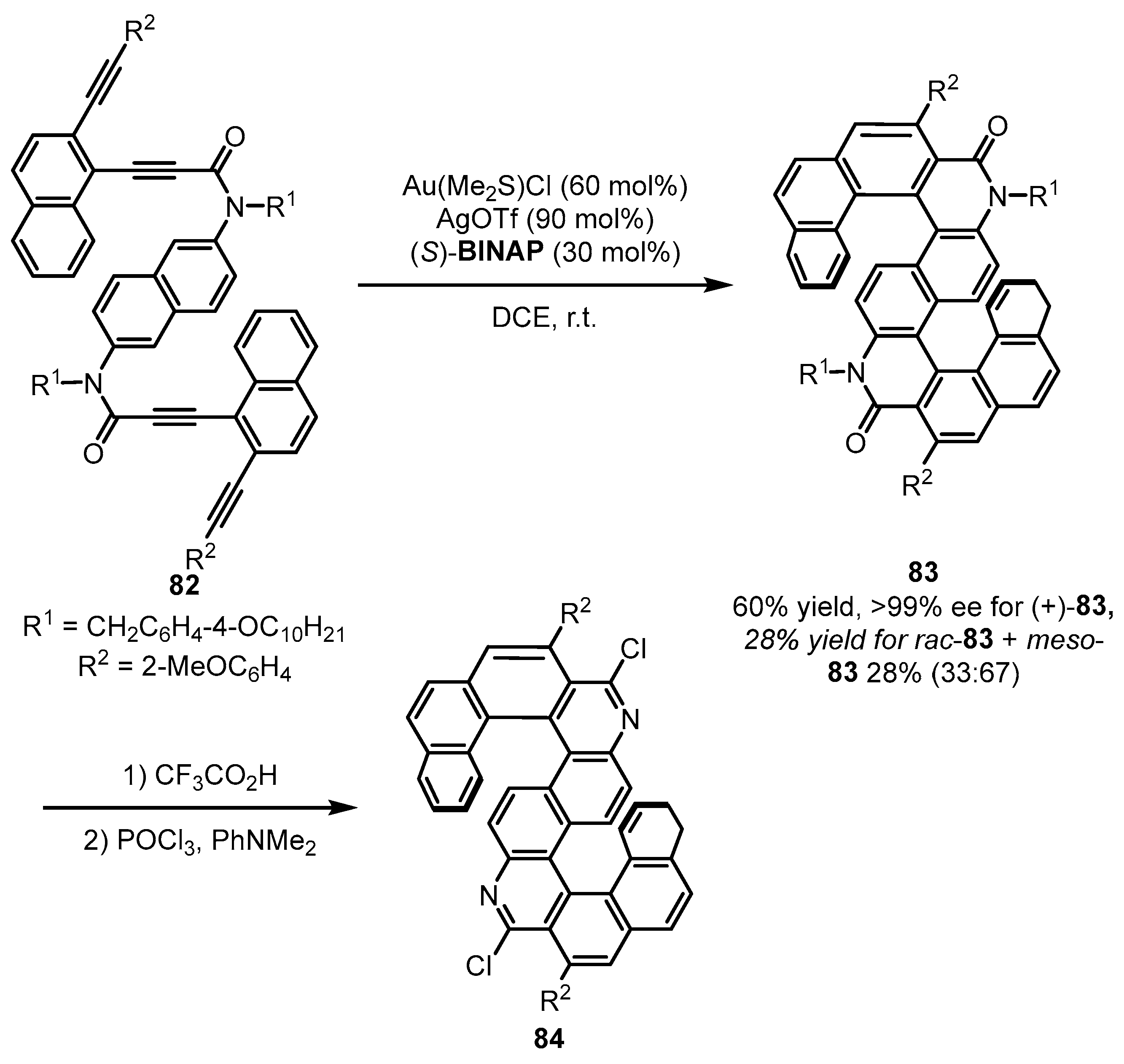

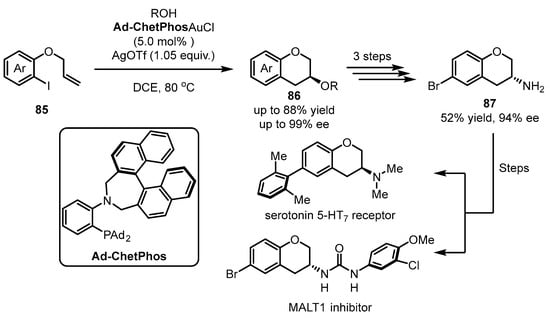

Chiral 3-aminochromane is an important precursor used to synthesize medicinally relevant chiral serotonin 5-HT7 receptor [85,86] or MALT1 inhibitor [87]. For the effective construction of this skeleton, the Patil group developed a gold(I)/gold(III) catalytic system for asymmetric 1,2-difunctionalization of alkenes in 2022 (Scheme 35) [88]. To tackle the challenging conflict between linear dicoordination in gold(I) and square-planar tetracoordination in gold(III), the authors introduced a hard Lewis base part (an amino group) adjacent to a sterically bulky soft phosphine group. Gold(III) is anticipated to form rigid geometry due to the combination of the hard amino group and the soft phosphine group simultaneously, while only the soft phosphine can construct coordination with gold(I). The Ad-ChetPhos-tethered gold(I) complex was exposed to the iodoaryl alkene 85 to yield 3-methoxychromane 86 in high yield and enantioselectivity (up to 88% yield and 99% ee). After an additional three steps, chiral 3-aminochromane 87 was smoothly achieved.

Scheme 35.

Redox gold(I)/gold(III) for asymmetric 1,2-difunctionalization of alkenes.

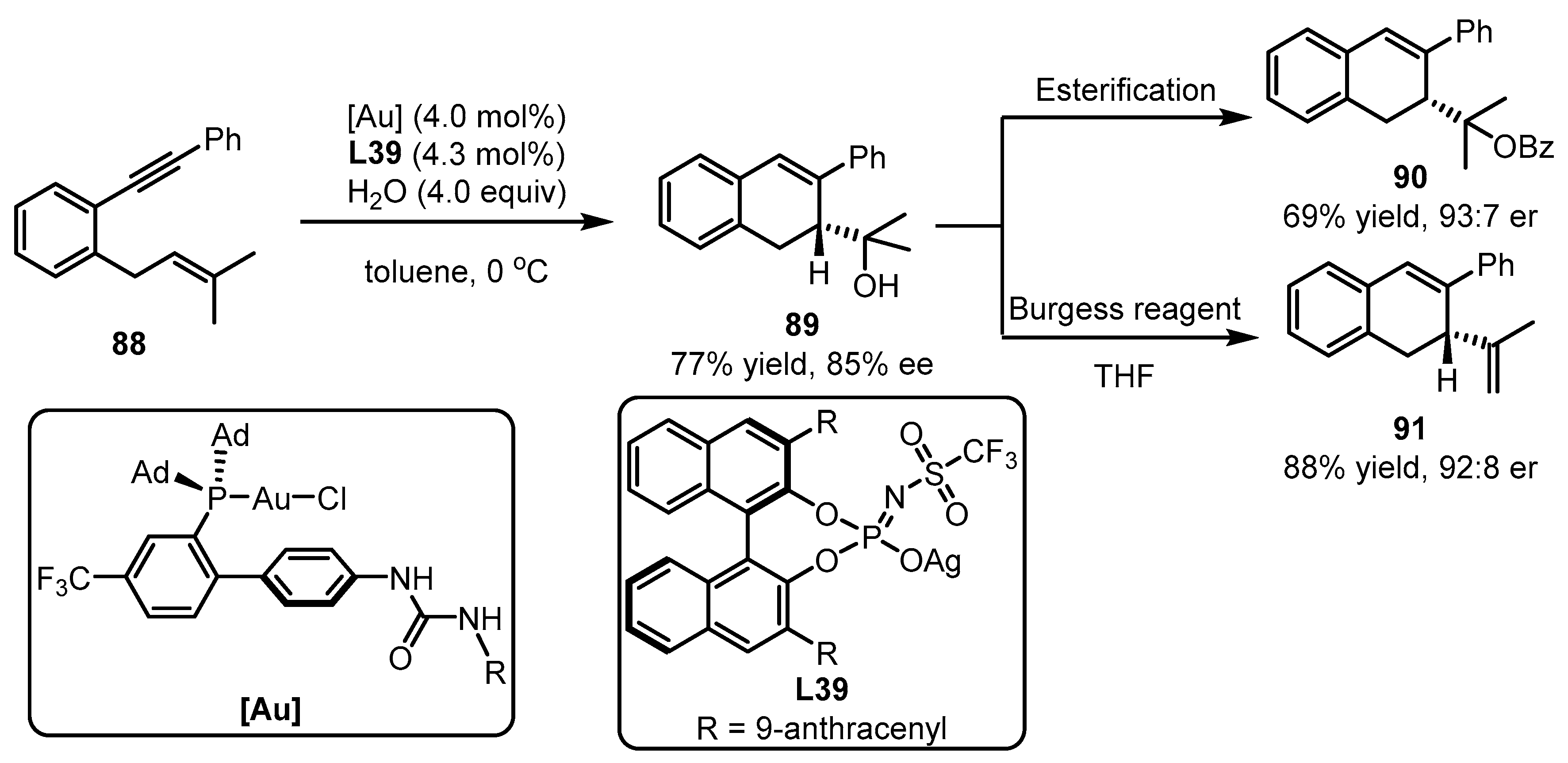

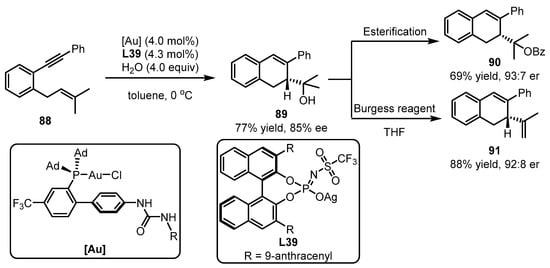

The prenylated stibenoid scaffolds have attracted the research interest of synthetic chemists due to their potential pharmaceutical applications. The Carexanes, which were isolated from the leaves of Carex distachya, demonstrated considerable good antimicrobial and antioxidant activity [89]. Recently, the Carexane core was efficiently prepared using bifunctional phosphines with a dual H-bond donor group (urea) for the gold catalyst by the Echavarren group (Scheme 36). To achieve this, the novel catalytic system was utilized for the effective asymmetric 5-exo-dig or 6-exo-dig cycloisomerization of 1,6-enynes 88. The bicyclic alcohol 89 was obtained in 77% yield and 85% ee, and it could be further transformed into other valuable molecules (69% yield and 93:7 er for 90; 88% yield and 92:8 er for 91) [90]. The chiral benzoate 90 and diene core 91 of the Carexane natural products offer considerable pharmaceutical potential.

Scheme 36.

Synthesis of chiral core of the carexane asymmetric gold catalysis.

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

In this review, a variety of chiral ligands are presented and their applications in asymmetric gold catalysis are demonstrated. These ligands are divided into different types, including aryl phosphine ligands bearing the proximal chiral sulfinamide motif, phosphoramidite and phosphonite ligands, phosphine ligands comprising the ferrocene scaffold, bifunctional phosphine ligands, biphosphine ligands, chiral counterion-based ligands derived from chiral phosphoric acids and chiral carbene ligands for Gold(I) catalysis along with unique ligand frameworks for cyclometalated gold(III) catalysis. The pivotal roles of the versatile ligands are comprehensively emphasized and the representative ligand-involving catalytic mechanisms are briefly discussed. Moreover, the potential applications of these gold-involved asymmetric reactions are further illustrated by the preparation of valuable functional molecules.

From the above discussions, significant progress has been made in the rapidly growing field of asymmetric gold catalysis. Nevertheless, several challenging problems and limitations remain, as described in the following aspects.

(1) Although the combination of photoredox catalysis and gold catalysis has been utilized to construct structurally diverse molecules, the direct construction of chiral molecules through this strategy has yet to be accomplished. Thus, designing chiral Gold photocatalysts for enantioselective transformations should be explored in future research.

(2) Gold(I) catalysts have been investigated more extensively than gold(III) catalysts. Thus, conducting detailed mechanistic studies utilizing gold(III) catalysts could provide a better understanding of the precise functions of gold and ligands in these transformations, potentially leading to broader applications of gold(III) catalysts.

(3) Apart from the intermolecular cycloaddition reactions, most of the asymmetric transformations have been achieved in an intramolecular manner. Thus, the exploration of various intermolecular reactions in the future may be another hot research topic in gold catalysis.

(4) The gold loadings for most reported reactions in the literature are between 5 and 10 mol%, which are relatively high and may restrict the applications of these techniques in industry. As a solution, designing new ligands capable of better binding to both gold catalysts and substrates may help alleviate this problem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, writing-original draft preparation Y.W. and H.Y.; writing—review and editing H.G., X.H. and L.G.; Supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, review and editing R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We are grateful for the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province of China (Grant Nos. 2022CFB779) and the financial support of Hubei University of Art and Science (qdf2023006), Foundation of Scientific and Technological Project of Xiangyang-area of Agriculture and Country (No. 202719290).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Santi, M.; Sancineto, L.; Nascimento, V.; Braun Azeredo, J.; Orozco, E.V.M.; Andrade, L.H.; Gröger, H.; Santi, C. Flow Biocatalysis: A Challenging Alternative for the Synthesis of APIs and Natural Compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, M.; Dong, M.; Zhao, T. Advances in Metal-Organic Frameworks MIL-101(Cr). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Sancho, C.; Mérida-Robles, J.M.; Cecilia-Buenestado, J.A.; Moreno-Tost, R.; Maireles-Torres, P.J. The Role of Copper in the Hydrogenation of Furfural and Levulinic Acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabortty, S.; Almasalma, A.A.; de Vries, J.G. Recent developments in asymmetric hydroformylation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 5388–5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, F.C. Transition metal-catalyzed deoxydehydration: Missing pieces of the puzzle. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 6308–6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Fu, G.C. Transition metal-catalyzed alkyl-alkyl bond formation: Another dimension in cross-coupling chemistry. Science 2017, 356, eaaf7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakiuchi, F.; Kochi, T. Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Carbon-Carbon Bond Formation via Carbon-Hydrogen Bond Cleavage. Synthesis 2008, 2008, 3013–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshi, N.U.D.; Saptal, V.B.; Beller, M.; Bera, J.K. Recent Progress in Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Asymmetric Reductive Amination. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 13809–13837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aplan, M.P.; Gomez, E.D. Recent Developments in Chain-Growth Polymerizations of Conjugated Polymers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 7888–7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Patil, N.T. Ligand-Enabled Sustainable Gold Catalysis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 6900–6918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, A.S.K. Gold-Catalyzed Organic Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 3180–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Brouwer, C.; He, C. Gold-Catalyzed Organic Transformations. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 3239–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcadi, A. Alternative Synthetic Methods through New Developments in Catalysis by Gold. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 3266–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorel, R.; Echavarren, A.M. Gold(I)-Catalyzed Activation of Alkynes for the Construction of Molecular Complexity. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9028–9072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.; Zhang, J. Gold-catalyzed cyclopropanation reactions using a carbenoid precursor toolbox. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 677–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, A.S.K.; Hutchings, G.J. Gold Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7896–7936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.C. Recent advances in syntheses of heterocycles and carbocycles via homogeneous gold catalysis. Part 1: Heteroatom addition and hydroarylation reactions of alkynes, allenes, and alkenes. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 3885–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.C. Recent advances in syntheses of carbocycles and heterocycles via homogeneous gold catalysis. Part 2: Cyclizations and cycloadditions. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 7847–7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrouwer, W.; Heugebaert, T.S.A.; Roman, B.I.; Stevens, C.V. Homogeneous Gold-Catalyzed Cyclization Reactions of Alkynes with N- and S-Nucleophiles. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015, 357, 2975–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huple, D.B.; Ghorpade, S.; Liu, R.-S. Recent Advances in Gold-Catalyzed N- and O-Functionalizations of Alkynes with Nitrones, Nitroso, Nitro and Nitroxy Species. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016, 358, 1348–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, S.A.; Sajid, M.A.; Khan, Z.A.; Canseco-Gonzalez, D. Gold catalysis in organic transformations: A review. Synth. Commun. 2017, 47, 735–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, R.T.; Awuah, S.G. Gold Catalysis: Fundamentals and Recent Developments. In Catalysis by Metal Complexes and Nanomaterials: Fundamentals and Applications; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Volume 1317, pp. 19–55. [Google Scholar]

- Collado, A.; Nelson, D.J.; Nolan, S.P. Optimizing Catalyst and Reaction Conditions in Gold(I) Catalysis–Ligand Development. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 8559–8612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campeau, D.; León Rayo, D.F.; Mansour, A.; Muratov, K.; Gagosz, F. Gold-Catalyzed Reactions of Specially Activated Alkynes, Allenes, and Alkenes. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 8756–8867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cera, G.; Bandini, M. Enantioselective Gold(I) Catalysis with Chiral Monodentate Ligands. Isr. J. Chem. 2013, 53, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-M.; Lackner, A.D.; Toste, F.D. Development of Catalysts and Ligands for Enantioselective Gold Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, W.; Dean Toste, F. Recent advances in enantioselective gold catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 4567–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, J. Gold-Catalyzed Enantioselective Annulations. Chem.-Eur. J. 2017, 23, 467–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milcendeau, P.; Sabat, N.; Ferry, A.; Guinchard, X. Gold-catalyzed enantioselective functionalization of indoles. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 6006–6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Hu, C.; Wang, T.; Eberle, L.; Hashmi, A.S.K. Gold-Catalyzed Reaction of Anthranils with Alkynyl Sulfones for the Regioselective Formation of 3-Hydroxyquinolines. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2022, 364, 1233–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniparoli, U.; Escofet, I.; Echavarren, A.M. Planar Chiral 1,3-Disubstituted Ferrocenyl Phosphine Gold(I) Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 3317–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.-J.; Wong, M.-K. Recent Advances in the Development of Chiral Gold Complexes for Catalytic Asymmetric Catalysis. Chem. Asian J. 2021, 16, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccarello, G.; Escofet, I.; Caniparoli, U.; Echavarren, A.M. New-Generation Ligand Design for the Gold-Catalyzed Asymmetric Activation of Alkynes. ChemPlusChem 2021, 86, 1283–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, S.; Herrero-Gómez, E.; Pérez-Galán, P.; Nieto-Oberhuber, C.; Echavarren, A.M. Gold(I)-Catalyzed Intermolecular Cyclopropanation of Enynes with Alkenes: Trapping of Two Different Gold Carbenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 6029–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorin, D.J.; Watson, I.D.G.; Toste, F.D. Fluorenes and Styrenes by Au(I)-Catalyzed Annulation of Enynes and Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3736–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, I.; Trillo, B.; López, F.; Montserrat, S.; Ujaque, G.; Castedo, L.; Lledós, A.; Mascareñas, J.L. Gold-Catalyzed [4C+2C] Cycloadditions of Allenedienes, including an Enantioselective Version with New Phosphoramidite-Based Catalysts: Mechanistic Aspects of the Divergence between [4C+3C] and [4C+2C] Pathways. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 13020–13030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flügge, S. Total Synthesis of Amphidinolide V and Analogues-Studies on Homogeneous Gold(I) Catalysis; Technische Universität Dortmund: Dortmund, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Teller, H.; Flügge, S.; Goddard, R.; Fürstner, A. Enantioselective Gold Catalysis: Opportunities Provided by Monodentate Phosphoramidite Ligands with an Acyclic TADDOL Backbone. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1949–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, H.; Corbet, M.; Mantilli, L.; Gopakumar, G.; Goddard, R.; Thiel, W.; Fürstner, A. One-Point Binding Ligands for Asymmetric Gold Catalysis: Phosphoramidites with a TADDOL-Related but Acyclic Backbone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 15331–15342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Fernández, E.; Nicholls, L.D.M.; Schaaf, L.D.; Farès, C.; Lehmann, C.W.; Alcarazo, M. Enantioselective Synthesis of [6]Carbohelicenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1428–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Simon, M.; Golz, C.; Alcarazo, M. Enantioselective Synthesis of [5]Helicenes Containing Two Additional Chiral Axes. Isr. J. Chem. 2022, e202200043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Qian, D.; Li, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J. Diastereo- and Enantioselective Gold(I)-Catalyzed Intermolecular Tandem Cyclization/[3+3]Cycloadditions of 2-(1-Alkynyl)-2-alken-1-ones with Nitrones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6669–6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Liu, F.; Zhang, J. Enantioselective Gold-Catalyzed Functionalization of Unreactive sp3 C—H Bonds through a Redox–Neutral Domino Reaction. Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 3101–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-M.; Chen, P.; Li, W.; Niu, Y.; Zhao, X.-L.; Zhang, J. A New Type of Chiral Sulfinamide Monophosphine Ligands: Stereodivergent Synthesis and Application in Enantioselective Gold(I)-Catalyzed Cycloaddition Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 4350–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Di, X.; Dai, Q.; Zhang, Z.-M.; Zhang, J. Gold-Catalyzed Asymmetric Intramolecular Cyclization of N-Allenamides for the Synthesis of Chiral Tetrahydrocarbolines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 15905–15909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Zhang, Z.-M.; Han, J.; Gu, G.; Zhang, J. Enantioselectivity Tunable Gold-Catalyzed Intermolecular [3 + 2] Cycloaddition of N-Allenamides with Nitrones. Chin. J. Chem. 2022, 40, 1407–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Sawamura, M.; Hayashi, T. Catalytic asymmetric aldol reaction: Reaction of aldehydes with isocyanoacetate catalyzed by a chiral ferrocenylphosphine-gold(I) complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 6405–6406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, C.; Ranieri, B.; Escofet, I.; López-Suarez, L.; Obradors, C.; Konovalov, A.I.; Echavarren, A.M. Enantioselective Synthesis of Cyclobutenes by Intermolecular [2+2] Cycloaddition with Non-C2 Symmetric Digold Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 13628–13631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Tian, B.; Hu, C.; Sekine, K.; Rudolph, M.; Rominger, F.; Hashmi, A.S.K. Chemodivergent reaction of azomethine imines and 2H-azirines for the synthesis of nitrogen-containing scaffolds. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 5505–5508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S.; Yamamoto, H. Carbonyl Recognition. In Modern Carbonyl Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2000; pp. 33–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.; Cramer, C.J.; Squires, R.R. Superacidity and Superelectrophilicity of BF3−Carbonyl Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 2633–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathke, M.W.; Cowan, P.J. Procedures for the acylation of diethyl malonate and ethyl acetoacetate with acid chlorides using tertiary amine bases and magnesium chloride. J. Org. Chem. 1985, 50, 2622–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathke, M.W.; Nowak, M. The Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons modification of the Wittig reaction using triethylamine and lithium or magnesium salts. J. Org. Chem. 1985, 50, 2624–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.S.; Polak, M.L.; Bierbaum, V.M.; DePuy, C.H.; Lineberger, W.C. Experimental Studies of Allene, Methylacetylene, and the Propargyl Radical: Bond Dissociation Energies, Gas-Phase Acidities, and Ion-Molecule Chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 6766–6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, W.S.; Bares, J.E.; Bartmess, J.E.; Bordwell, F.G.; Cornforth, F.J.; Drucker, G.E.; Margolin, Z.; McCallum, R.J.; McCollum, G.J.; Vanier, N.R. Equilibrium acidities of carbon acids. VI. Establishment of an absolute scale of acidities in dimethyl sulfoxide solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 7006–7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Li, T.; Gutman, K.; Zhang, L. Chiral Bifunctional Phosphine Ligand-Enabled Cooperative Cu Catalysis: Formation of Chiral α,β-Butenolides via Highly Enantioselective γ-Protonation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 10876–10881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Zhang, L. Chiral Bifunctional Phosphine Ligand Enables Gold-Catalyzed Asymmetric Isomerization and Cyclization of Propargyl Sulfonamide into Chiral 3-Pyrroline. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 8194–8198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Dong, S.; Tang, C.; Zhu, M.; Wang, N.; Kong, W.; Gao, W.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L. Asymmetric Construction of α,γ-Disubstituted α,β-Butenolides Directly from Allylic Ynoates Using a Chiral Bifunctional Phosphine Ligand Enables Cooperative Au Catalysis. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 4427–4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, T.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, L. Efficient Synthesis of α-Allylbutenolides from Allyl Ynoates via Tandem Ligand-Enabled Au(I) Catalysis and the Claisen Rearrangement. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 10339–10342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Kohnke, P.; Yang, Z.; Cheng, X.; You, S.-L.; Zhang, L. Enantioselective Dearomative Cyclization Enabled by Asymmetric Cooperative Gold Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202207518. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, M.P.; Adrio, J.; Carretero, J.C.; Echavarren, A.M. Ligand Effects in Gold- and Platinum-Catalyzed Cyclization of Enynes: Chiral Gold Complexes for Enantioselective Alkoxycyclization. Organometallics 2005, 24, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.J.; Gorin, D.J.; Staben, S.T.; Toste, F.D. Gold(I)-Catalyzed Stereoselective Olefin Cyclopropanation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 18002–18003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Widenhoefer, R.A. Gold(I)-Catalyzed Intramolecular Enantioselective Hydroalkoxylation of Allenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, S.Y.; Shin, S. Asymmetric Synthesis of Dihydropyranones via Gold(I)-Catalyzed Intermolecular [4+2] Annulation of Propiolates and Alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 13130–13134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaLonde, R.L.; Sherry, B.D.; Kang, E.J.; Toste, F.D. Gold(I)-Catalyzed Enantioselective Intramolecular Hydroamination of Allenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 2452–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, G.L.; Kang, E.J.; Mba, M.; Toste, F.D. A Powerful Chiral Counterion Strategy for Asymmetric Transition Metal Catalysis. Science 2007, 317, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaLonde, R.L.; Wang, Z.J.; Mba, M.; Lackner, A.D.; Toste, F.D. Gold(I)-Catalyzed Enantioselective Synthesis of Pyrazolidines, Isoxazolidines, and Tetrahydrooxazines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 598–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomé, C.; García-Cuadrado, D.; Ramiro, Z.; Espinet, P. Synthesis and Catalytic Activity of Gold Chiral Nitrogen Acyclic Carbenes and Gold Hydrogen Bonded Heterocyclic Carbenes in Cyclopropanation of Vinyl Arenes and in Intramolecular Hydroalkoxylation of Allenes. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 9758–9764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-M.; Kuzniewski, C.N.; Rauniyar, V.; Hoong, C.; Toste, F.D. Chiral (Acyclic Diaminocarbene)Gold(I)-Catalyzed Dynamic Kinetic Asymmetric Transformation of Propargyl Esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12972–12975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, S.; Slaughter, L.M. Enantioselective Alkynylbenzaldehyde Cyclizations Catalyzed by Chiral Gold(I) Acyclic Diaminocarbene Complexes Containing Weak Au–Arene Interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 2912–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khrakovsky, D.A.; Tao, C.; Johnson, M.W.; Thornbury, R.T.; Shevick, S.L.; Toste, F.D. Enantioselective, Stereodivergent Hydroazidation and Hydroamination of Allenes Catalyzed by Acyclic Diaminocarbene (ADC) Gold(I) Complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6079–6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeyer, Z.L.; Pindi, S.; Khrakovsky, D.A.; Kuzniewski, C.N.; Hong, C.M.; Joyce, L.A.; Sigman, M.S.; Toste, F.D. Parameterization of Acyclic Diaminocarbene Ligands Applied to a Gold(I)-Catalyzed Enantioselective Tandem Rearrangement/Cyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12943–12946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joost, M.; Amgoune, A.; Bourissou, D. Reactivity of Gold Complexes towards Elementary Organometallic Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 15022–15045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, J.; del Pozo, C. Fluorine and Gold: A Fruitful Partnership. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11924–11966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Shi, M. Divergent Synthesis of Carbo- and Heterocycles via Gold-Catalyzed Reactions. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 2515–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.W.; DiPasquale, A.G.; Bergman, R.G.; Toste, F.D. Synthesis of Stable Gold(III) Pincer Complexes with Anionic Heteroatom Donors. Organometallics 2014, 33, 4169–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, A.S.K.; Blanco, M.C.; Fischer, D.; Bats, J.W. Gold Catalysis: Evidence for the In-situ Reduction of Gold(III) During the Cyclization of Allenyl Carbinols. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 2006, 1387–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.-F.; Ko, H.-M.; Shing, K.-P.; Deng, J.-R.; Lai, N.C.-H.; Wong, M.-K. C,O-Chelated BINOL/Gold(III) Complexes: Synthesis and Catalysis with Tunable Product Profiles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3074–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-Y.; Horibe, T.; Jacobsen, C.B.; Toste, F.D. Stable gold(III) catalysts by oxidative addition of a carbon–carbon bond. Nature 2015, 517, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohan, P.T.; Toste, F.D. Well-Defined Chiral Gold(III) Complex Catalyzed Direct Enantioconvergent Kinetic Resolution of 1,5-Enynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 11016–11019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, J.P.; Hu, M.; Ito, S.; Huang, B.; Hong, C.M.; Xiang, H.; Sigman, M.S.; Toste, F.D. Strategies for remote enantiocontrol in chiral gold(iii) complexes applied to catalytic enantioselective γ,δ-Diels–Alder reactions. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 6450–6456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.-J.; Cui, J.-F.; Yang, B.; Ning, Y.; Lai, N.C.-H.; Wong, M.-K. Chiral Cyclometalated Oxazoline Gold(III) Complex-Catalyzed Asymmetric Carboalkoxylation of Alkynes. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 6289–6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Simon, M.; Golz, C.; Alcarazo, M. Gold-Catalyzed Atroposelective Synthesis of 1,1′-Binaphthalene-2,3′-diols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 5647–5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Furumi, S.; Takeuchi, M.; Shibuya, T.; Tanaka, K. Enantioselective Synthesis and Enhanced Circularly Polarized Luminescence of S-Shaped Double Azahelicenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5555–5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmberg, P.; Tedenborg, L.; Rosqvist, S.; Johansson, A.M. Novel 3-aminochromans as potential pharmacological tools for the serotonin 5-HT7 receptor. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badarau, E.; Bugno, R.; Suzenet, F.; Bojarski, A.J.; Finaru, A.-L.; Guillaumet, G. SAR studies on new bis-aryls 5-HT7 ligands: Synthesis and molecular modeling. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 1958–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pissot Soldermann, C.; Simic, O.; Renatus, M.; Erbel, P.; Melkko, S.; Wartmann, M.; Bigaud, M.; Weiss, A.; McSheehy, P.; Endres, R.; et al. Discovery of Potent, Highly Selective, and In Vivo Efficacious, Allosteric MALT1 Inhibitors by Iterative Scaffold Morphing. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 14576–14593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chintawar, C.C.; Bhoyare, V.W.; Mane, M.V.; Patil, N.T. Enantioselective Au(I)/Au(III) Redox Catalysis Enabled by Chiral (P,N)-Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 7089–7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Abrosca, B.; Fiorentino, A.; Golino, A.; Monaco, P.; Oriano, P.; Pacifico, S. Carexanes: Prenyl stilbenoid derivatives from Carex distachya. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 5269–5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchino, A.; Martí, À.; Echavarren, A.M. H-Bonded Counterion-Directed Enantioselective Au(I) Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 3497–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).