1. Introduction

Aside from the well-known pollutants and contaminants in the aquatic environment, compounds of emerging concern (CECs) may impact aquatic life even in very low concentrations [

1]. Wastewater influents and effluents can contain CECs, due to their presence in everyday products, such as detergents, fabric coatings, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, beverages and food packaging [

2]. Pharmaceuticals are being detected in drinking and surface water, and although not very persistent, the continuous re-entering increases their abundance, and renders them pseudo-persistent [

3]. Pharmaceuticals, include diverse types of compounds, e.g., antibiotics and show low biodegradability. CECs cannot be removed completely by wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) [

2], since WWTP were not designed to treat CECS. In some cases, even less than 10% of CECs is removed, making WWTP effluents a major factor for introducing CECs into the environment [

2]. Recently, great attention is given to adsorption technique [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], which is easily applied to the last stage of wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), with the aim of removing all residues that were not separated and removed from the previous stages.

In particular, special attention is given to find appropriate ways to effectively treat antibiotics from effluents, due to their strong resistance to various decontamination techniques [

20]. Available statistics indicate that 100–200 tn of antibiotics are used annually worldwide. As a result, the risk of water resources contamination by these compounds is very high. The residue of those antibiotics in the form of major constituents or metabolites has also been observed in WWTP.

It is noteworthy to mention that the inability of WWTP to remove antibiotics leads to the discharge of those compounds into surface water and underground waters. The inadequate and incorrect use of those compounds, and their continuous entry into the environment, leads to biodistribution and faulty resistance [

21,

22]. Of the large antibiotic classes, fluoroquinolones are worth mentioning. Antibiotics in this family include Ciprofloxacin (CIP), epinephrine, and norfloxacin. The presence of fluorine atoms in combination with these antibiotics makes these compounds particularly stable, so they are considered to be very dangerous and toxic pollutants in the environment. CIP is detected in sewage and surface water in medical effluents and pharmaceutical plants. The antibiotic can be adsorbed into the sludge and, if applied as fertilizer, it is accumulated in the soil and enters into plants [

23]. CIP was observed in surface waters and wastewaters at concentrations below 1 μg/L, while in medical wastewaters in 150 μg/L. Therefore, it is mandatory to find and apply an efficient method for ciprofloxacin removal.

The most important methods used to remove and separate the drug compounds from water and sewage include ozonation, nanofiltration, electron radiation, ion exchange, chemical coagulation and photocatalytic oxidation, all of which have high performance and operation costs [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Nowadays, nanotechnologies are mainly used in water and wastewater treatment, using materials like iron nanoparticles, zeolites and magnetic nanomaterials [

30,

31]. Among the various methods, adsorption is a simple, environmental friendly, fast, highly efficient and low-cost solution, making it one of the most favorable methods [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

The removal of pharmaceuticals by adsorption has been the focus of many studies. So far, as adsorptive materials, activated carbon [

38,

39,

40,

41] or zeolites [

42,

43] have been widely used in wastewater treatment. The removal of pharmaceuticals by adsorption shows great potential, due to its easy application into existing water treatment processes. On the other hand, issues regarding adsorbent stability and regeneration costs lead to R&D of innovative and effective adsorbents from polymeric materials. Adsorption processes, such as activated carbon-based have high capital cost, and ineffectiveness and non-selectivity against vat and disperse dyes. Furthermore, saturated carbon regeneration is expensive and leads to adsorbent loss. Depending on the demand, cost, and the nature of the pollutant to be adsorbed, the adsorbents are either disposed or regenerated for future use. The regeneration process of adsorbents needs to be cheap and environmental friendly by recovering valuable adsorbates while reducing the need of virgin adsorbents.

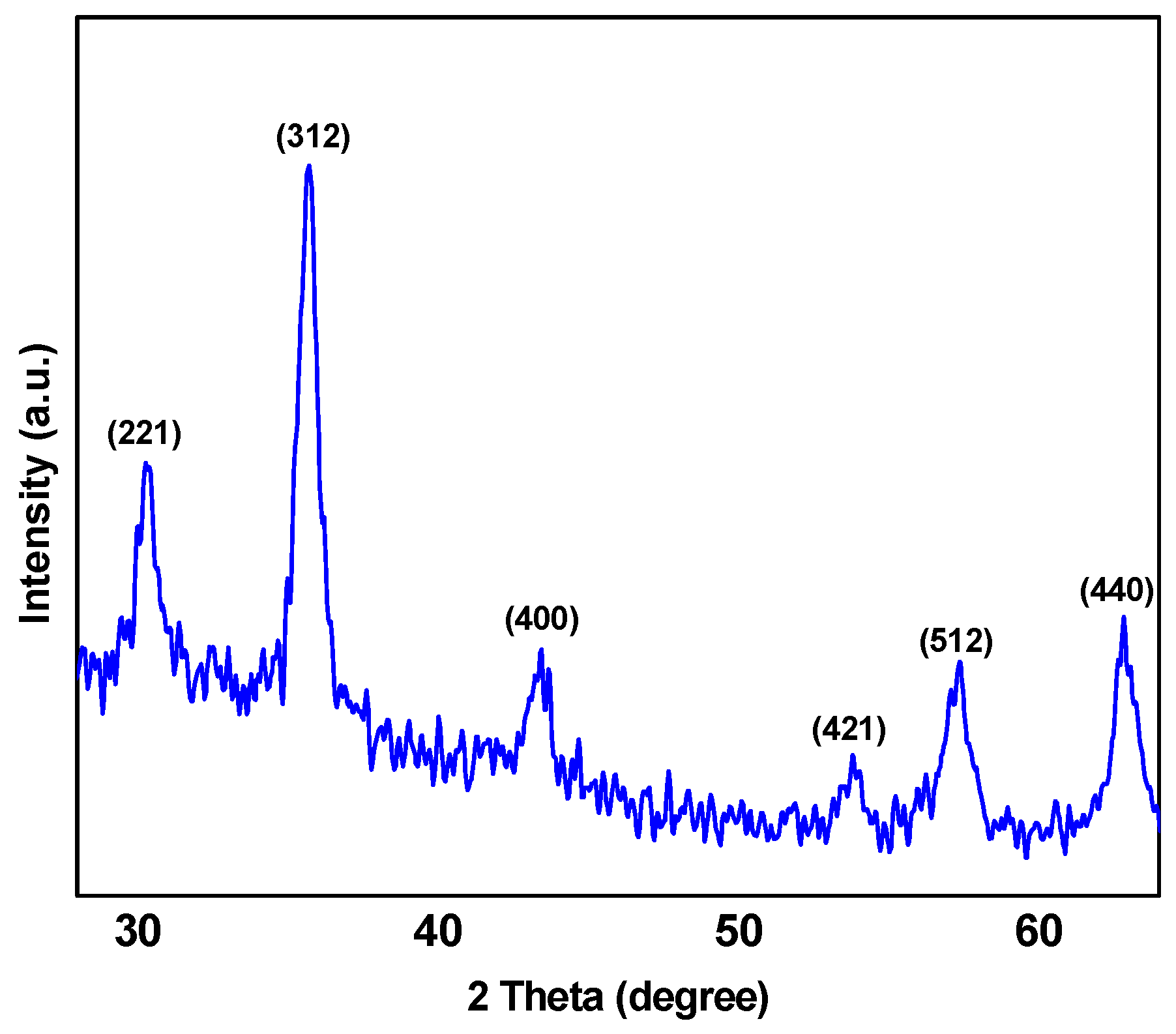

In this study, a versatile synthesis of poly(styrene-block-acrylic acid) diblock copolymer/Fe3O4 magnetic nanocomposite (abbreviated as P(St-b-AAc)/Fe3O4)) was achieved for environmental applications with a focus on the removal of ciprofloxacin. The nanocomposites were characterized with SEM, XRD and VSM analysis. The nanoparticles were then applied to remove ciprofloxacin (antibiotic drug compound) from aqueous solutions, evaluating the effect of certain important parameters such as the solution’s pH, initial ciprofloxacin concentration, adsorbent dosage and contact time.

4. Discussion

The contact time is an important factor that directly influences the whole process. In the present work, for a concentration of 5 mg/L, the adsorption process reaches equilibrium at about 37 min, and then shows a relatively stable trend. The effect of the pollutant’s initial concentration is affecting a lot the adsorption process. In this paper, the pollutant’s initial concentration was studied, ranging from 5 to 50 mg/L. As shown in

Figure 7, the initial CIP concentration had a negative effect on the elimination efficiency, and by increasing the ciprofloxacin concentration from 16.25 to 25 mg/L, the elimination efficiency decreased from 84 to 57%. The decrease in removal efficiency when increasing initial concentration can be explained by the fact that the active sites are constant with a constant amount of adsorbent dose, but as the concentration of the adsorbent increases, the pollutant molecules (in the medium—water) saturate the available adsorption sites, thereby, the removal efficiency is lowered [

49]. Bajpai et al. observed that by increasing the initial concentration of ciprofloxacin from 10 to 20 mg/L, the adsorption capacity increased from 3.74 to 11.32 mg/g [

50].

4.1. Effect of pH Solution

In the purification processes, including adsorption, pH plays an important role. The Solution’s pH can affect the adsorbent’s surface load, the degree of ionization of various pollutants, the separation of functional groups on active adsorbent sites, as well as the structure of the antibiotic molecule; in effect, the solution’s pH affects the chemical environment of the aqueous and adsorption surface bonds. The pH changes were applied to the range of 4–10, and its effect on the removal efficiency was then analyzed. The removal process had the highest percentage at pH 6.2–7, while with the increase of pH, the removal efficiency decreased.

The effect of pH on the ciprofloxacin molecule has shown that in pH less than 6.2, the surface of the molecule appears cationic and positive due to the protonation of amino groups. At pH values higher than 8.6, the ciprofloxacin molecule is converted into anionic form, due to the loss of the proton from the carboxylic group in the antibiotic structure. In the range of 6.2 to 8.6, the deprotonation of carboxyl groups leads to negative carboxylate production. However, the amino group of proteins has a positive charge. In other words, it has a positive and a negative “head”. The stabilization and behavior of ciprofloxacin molecule from 6.2 to 7.8 have also been investigated [

51]. Since the pH value at pH

pzc at the isoelectric absorption point is 7.5, and is negatively charged at higher pH values, given that at pH values above 7.5, both the adsorbent and the antibiotic molecule are both negatively charged. At a pH of less than 6.2, the adsorbent and the antibiotic have positive charge, so in this range, the adsorption process occurs slower and reaches at minimum removal rate at pH = 6.2-6.8, because the unnamed bands reach the maximum electrostatic gravity.

4.2. Effect of Adsorbent’s Dose

Based on the findings of this study, the adsorbent dose was the most important factor affecting the efficiency of ciprofloxacin elimination. The study of the effect of adsorbent mass on adsorption processes is one of the most important issues to be considered. Adsorption dose was applied to the range of 1 to 3 mg/L, and its effect on the effectiveness of ciprofloxacin antibiotic removal was measured. Depending on the results obtained using constant concentrations of antibiotics, the increase in the dose of the adsorbent improves the removal efficiency. As shown in

Figure 8, when the concentration of antibiotic is constant and equal to 16.25 mg/L, and the amount of adsorbent is 1.5 mg/L, the removal efficiency is 75.97%—and when the amount of adsorbent reaches 2 mg/L, the removal efficiency is improved, reaching 95.91%; at a constant concentration of antibiotic, by increasing the dose of adsorbent, the ratio of active sites on the adsorbent’s surface is high relative to the adsorbing molecules (pollutants), resulting in increased elimination efficiency. On the contrary, in low adsorbent amounts, the ratio of active sites to the adsorbent molecules is lower, and the adsorption decreases.

On the other hand, with the increase of adsorbent above the optimal amount, the adsorption capacity decreased below the maximum level of 15.25 mg/g, which is also due to the fact that by increasing the adsorbent dose, the total capacity of the active sites present in the adsorbent level is completely covered. If not, its adsorption capacity is reduced. This can be the use of available surface in the form of unsaturated attributed adsorbent. The results show that the adsorption pattern in the non-saturable adsorbent form causes undesirable use of existing spaces; this issue is very important in the design of the process economics, particularly in scaling-up.

In this study, 5 mg/L of antibiotic and 2 mg/L of adsorbent were introduced as the optimum amount, at maximum efficiency, with application of 2 mg/L of adsorbent, despite the increase in adsorbent content, other increase in cleavage removal efficiency has not shown any increase. In other words, the removal rate remains constant. It can be concluded that this amount of adsorbent adsorbs all the antibiotics in the solution. Therefore, the antibiotic concentration in the solution is so low that it is no longer “able to be adsorbed” easily. A study by Peasant et al. also showed that with the increase in the adsorbent dose (chitosan/zeolite composite), the dye removal increases, due to the increasing number of adsorption sites, while the increase of adsorbent’s dose reduces the adsorption capacity (from the maximum of 17.77 mg/g) [

52].

4.3. Effect of Contact Time

An important issue when using the adsorption system is providing an effective contact time under specific conditions. In this paper, contact time was applied to the range of 15 to 60 min, and its effect on the ciprofloxacin antibiotic removal.

Figure 7 shows that the adsorption process reaches equilibrium at different times. For a concentration of 5 mg/L, the adsorption process reaches equilibrium at about 37 min, and then shows a relatively stable trend. By increasing contact time, the probability of colliding with adsorbent molecules is also increased, and the efficiency of removal increased. Chang et al. (2012) obtained the equilibrium time for tetracycline removal by Monte Myrnolite for 8 h [

53]. In another study by Liu et al. who removed tetracycline using zeolite= by increasing contact time, resulted in the removal efficiency also increased, and the time of equilibrium was 120 min [

54].

4.4. Kinetics and Adsorption Isotherms

The adsorption kinetics depends on the adsorbent chemical and physical properties, which influence the adsorption mechanism. In this study, we have used different kinetic and isotherm adsorption models such as pseudo-first order, pseudo-second order, Langmuir, and Freundlich (

Table 4).

The pseudo-first and pseudo-second order kinetic equations are shown in

Figure 10. Adsorption kinetics were used to determine the control mechanism of adsorption processes. Thus, in this figure, the experimental points were not shown, and only theoretical ones are presented. Based on

Table 5, the best fitting was achieved with pseudo-second order equation (R

2 = 0.9984).

The isotherm of adsorption describes how the adsorbent and adsorbate interact. In this study, the experimental results were fitted to Freundlich and Langmuir isotherms. The Langmuir model is valid for single-layer adsorption on adsorbent surface, with limited and uniform adsorption locations, while the Freundlich isotherm is based on single-layer adsorption on heterogeneous adsorption sites with unequal and non-uniform energies.

Figure 11 shows the relative isotherms.

In Freundlich isotherm, when K

F increases, the adsorbent material adsorbed higher amounts of pollutant, and the value of n between 1 and 10 reflects the proper adsorption process. The parameters and coefficients are briefly summarized in

Table 5. In this study, the calculated K

F value is 4.75, and the value of n is 2.79, which is within the specified range. Therefore, the adsorption of ciprofloxacin on the adsorbent is well fitted to Langmuir model (

Table 6), but it is fact that the data may suggest the presence of non-specific or multi-type interactions between the adsorbate molecules and the adsorptive sites.

A major concern regarding any synthesized adsorbent material is answering why this material was synthesized instead of another structure-type material? To respond, it is of fundamental importance to mention some facts. Nanoparticles have a unique combination of properties, such as small size, large surface area, catalytic potential, large number of active sites, high chemical reactivity; all of the above give nanoparticles high adsorption capacity [

59]. Also, magnetic nanoadsorbents can be applied as cost-saving and effective materials to separate the materials (solid) from the liquid-phase (water) after the end of the adsorption process. Moreover, the relatively simple isolation of magnetic materials from the solution can aid to their regeneration and reuse [

60]. Therefore, the magnetic nanoadsorbents can be good candidates for water/wastewater treatment. Based on the above, Poly(vinylimidazole-co-divinylbenzene) magnetic nanoparticles have been used for the adsorption of fluoroquinolones from aqueous environments [

61]. Wang et al. also synthesized the easy to separate magnetic chalcogenide composite KMS-1/L-Cystein/Fe

3O

4 using L-cystein to connect KMS-1 and Fe

3O

4 nanoparticles for ciprofloxacin removal from aqueous solutions [

62].

Table 7 shows a brief comparison of some other adsorbent materials tested for the removal of CIP. However, similar experimental conditions should be kept in order to compare two adsorbents (even for the treatment of the same pollutant). Parameters affecting adsorption are the contact time, the solutions’ pH, the initial concentration of the pollutant, temperature, adsorbate volume, agitation speed, the solution’s ionic strength, and adsorbent dosage. Any change to the abovementioned conditions will lead to different results, and the comparison can be made for adsorbent/adsorbate systems of the same study. Also, based on the interaction groups, a possible mechanism of adsorption is illustrated in

Figure 12.

4.5. Aspects

It is known that activated carbon is a very popular adsorbent material, with the demand for virgin activated carbon expanding, since demand from water and wastewater treatment facilities has been steadily increasing. Together with the increase of wastewater treatment applications, the demand and production of activated carbon is also increasing. The largest quantities of activated carbon consumption are observed the U.S.A, Japan and then Europe [

72]. Antibiotics are being detected in the aquatic environment. There are different ways for antibiotics to enter the aquatic environment with WWTP considered to be one of the main points of entrance. Even treated wastewater effluent can contain antibiotics, since WWTP cannot eliminate the presence of antibiotics. Compared to other tertiary treatments, adsorption can be a sustainable option for antibiotic removal from wastewaters. Activated carbon is used in the pharmaceutical for the removal of unwanted compounds [

72]. Activated carbon possesses a plethora of disadvantages [

73], such as high capital cost, ineffectiveness and non-selectivity against vat/disperse dyes. Furthermore, saturated carbon regeneration is expensive and leads to adsorbent loss. Depending on the demand, cost, and the nature of the pollutant to be adsorbed, the adsorbents are either disposed or regenerated for future use. Used adsorbents are considered hazardous waste, causing environmental and societal problems in various countries [

74]. Heat accumulation and toxic adsorbates desorption could create hazardous conditions. In addition, odor can be caused by the dumping of adsorbents.

Since regeneration costs can be quite high, the reduction of consumption costs is the key to sustainable and industrial benefits. Substantial studies regarding the activated carbon-based adsorption of pollutants onto have been conducted, but research on regeneration methodologies remains limited [

75]. Adsorbent regeneration capability cost analysis is necessary for the economic and environmental assessment of the adsorption process. For the spent adsorbent stabilizing or proper disposal seem to be difficult. The regeneration process of adsorbents from the points of view of sustainability and the environmental involves recovering valuable adsorbates, while reducing the need of virgin adsorbents, and this is extremely important. Studies on novel adsorbents, at full-scale adsorption systems, should be considered for potential industrial applications.