Enhanced Lithium-Ion Transport in Lithium Metal Batteries Using ZSM-5 Nanosheets Hybridized Solid Polymer Electrolytes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Sections

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

2.2. Synthesis of ZSM-5 Nanosheets

2.3. Preparation of Electrolyte Membranes

2.4. Preparation of LFP Cathode

2.5. Characterization

2.6. Electrochemical Test

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization and Performance of ZSM-5 Nanosheets and CPE Membranes

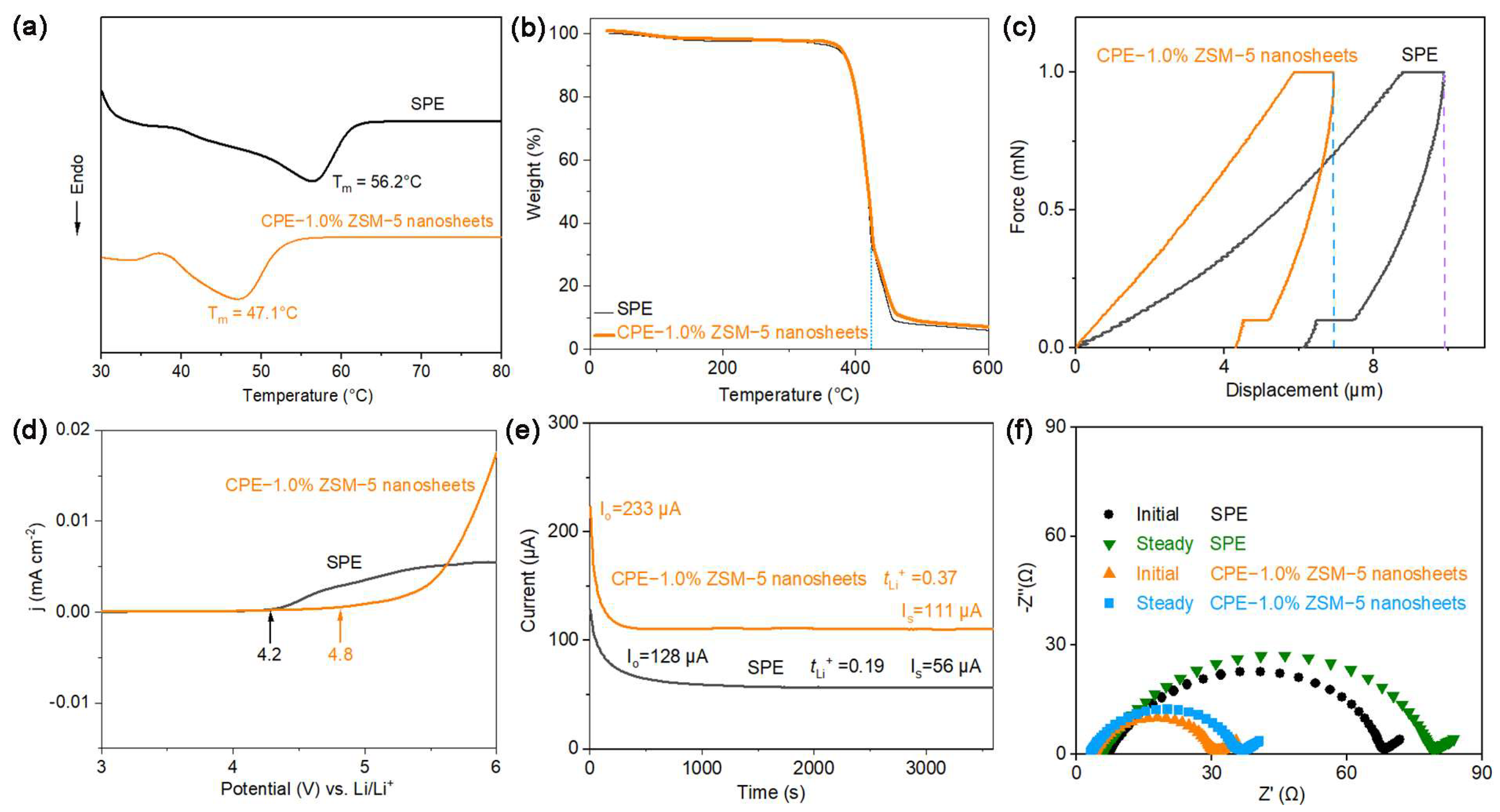

3.2. Electrochemical Performance of Electrolyte Membranes

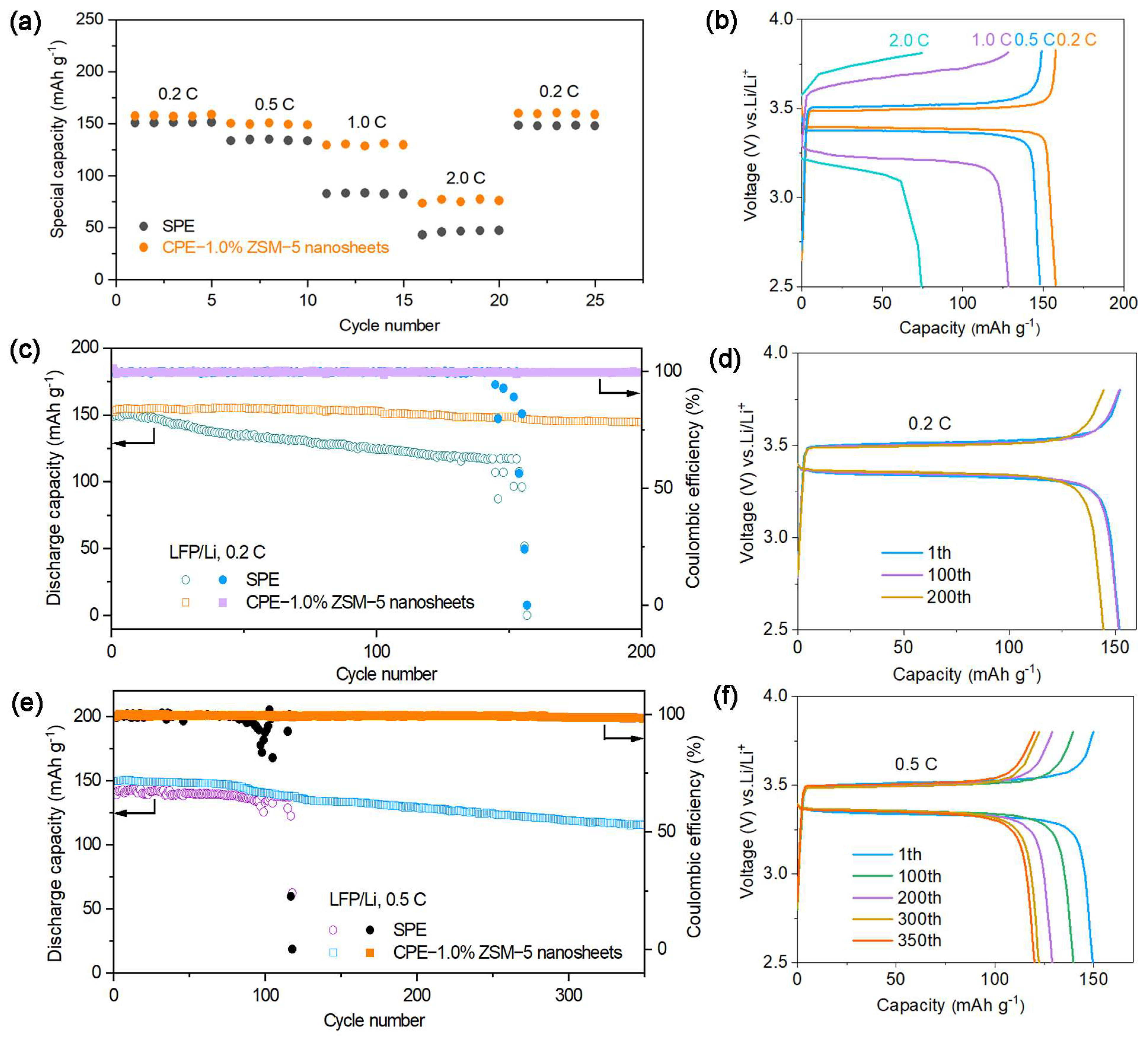

3.3. Performance of All-Solid-State Cells

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, B.; Pan, Z.F.; Su, X.Y.; An, L. Recycling of lithium-ion batteries: Recent advances and perspectives. J. Power Sources 2018, 399, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubi, G.; Dufo-López, R.; Carvalho, M.; Pasaoglu, G. The lithium-ion battery: State of the art and future perspectives. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2018, 89, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.Q.; Ma, J.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhao, J.W.; Dong, S.M.; Liu, Z.H.; Cui, G.L.; Chen, L.Q. All solid-state polymer electrolytes for high-performance lithium ions batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2016, 5, 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.G.; He, D.; Xie, X.L. Poly (ethylene oxide)-based electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 19218–19253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.; Mackanic, D.G.; Cui, Y.; Bao, Z.N. Designing polymers for advanced battery chemistries. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 312–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.X.; Wu, Y.L.; Qiu, M.; Li, X.; Li, C.P.; Li, R.L.; He, J.B.; Lin, G.G.; Qian, Q.R.; Wen, Z.H.; et al. Research progress in electrospinning engineering for all-solid-state electrolytes of lithium metal batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 61, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiker, D.M.D.; Usha, Z.R.; Wan, C.X.; Hassaan, M.M.E.; Chen, X.; Li, L.B. Recent progress of composite polyethylene separators for lithium/sodium batteries. J. Power Sources 2023, 564, 232853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.Y.; Sun, Y.Y.; Hui, B.; Xia, Y.Z.; Zou, Y.H.; Zhang, X.L.; Yang, D.J. Three-dimensional porous alginate fiber membrane reinforced PEO-based solid polymer electrolyte for safe and high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 12, 43805–43812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Deng, N.P.; Zhao, Y.X.; Gao, L.; Cheng, B.W.; Kang, W.M. A review on 1D materials for all-solid-state lithium-ion batteries and all-solid-state lithium-sulfur batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Liu, G.; Yu, W.; Dong, X.; Wang, J. Review on composite solid electrolytes for solid-state lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Today Sustain. 2023, 21, 100316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, M.; Liu, X.F.; Zhang, B.Q. Pebax/two-dimensional MFI nanosheets mixed-matrix membranes for enhanced CO2 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 636, 119612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Guo, H.Y.; Muradi, G.; Zhang, B.Q. Tuning the multi-scale structure of mixed-matrix membranes for upgrading CO2 separation performances. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 293, 121118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, X.F.; Zhang, B.Q. Submicrometer-thick b-oriented Fe–silicalite-1 membranes: Microwave-assisted fabrication and pervaporation performances. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 108265–108269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, B.Q. Defects reparation and surface hydrophilic modification of zeolite beta membranes with spherical polyelectrolyte complex nanoparticles via vacuum-wiping deposition technique. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 602, 117977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.Y.; Tang, X.Z. Investigations on the enhancement mechanism of inorganic filler on ionic conductivity of PEO-based composite polymer electrolyte: The case of molecular sieves. Electrochim. Acta 2006, 51, 4765–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.W.; Zhang, S.P.; Wang, B.R.; Gu, S.; Xu, D.; Wang, J.N.; Chen, C.H.; Wen, Z.Y. Nanoporous adsorption effect on alteration of the Li+ diffusion pathway by a highly ordered porous electrolyte additive for high rate all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 23874–23882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, J.Y.; Miao, S.J.; Tang, X.Z. Selective transporting of lithium ion by shape selective molecular sieves ZSM-5 in PEO-based composite polymer electrolyte. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 8592–8598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.Y.; Qiu, X.P.; Wang, J.S.; Bai, Y.X.; Zhu, W.T.; Chen, L.Q. Effect of molecular sieves ZSM-5 on the crystallization behavior of PEO-based composite polymer electrolyte. J. Power Sources 2006, 158, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Xiang, Y.K.; Jamil, M.I.; Lu, J.G.; Zhang, Q.H.; Zhan, X.L.; Chen, F.Q. Polymers/zeolite nanocomposite membranes with enhanced thermal and electrochemical performances for lithium-ion batteries. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 564, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.L.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, D.H.; Ruoff, R.S.; Yu, G.H. Two-dimensional materials for beyond-lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1600025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramin, R.; Yassar, R.S. Two-dimensional materials to address the lithium battery challenges. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 2628–2658. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, S.; Fang, R.P.; Sun, Z.H.; Wu, M.J.; Gu, Z.; Wang, Y.Z.; Hart, J.N.; Sharma, N.; Li, F.; Wang, D.W. Hybrid solid polymer electrolytes with two-dimensional inorganic nanofillers. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 18180–18203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, M.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Kumar, P.; Lee, P.S.; Rangnekar, N.; Bai, P.; Shete, M.; Elyassi, B.; Lee, H.S.; Narasimharao, K.; et al. Ultra-selective high-flux membranes from directly synthesized zeolite nanosheets. Nature 2017, 543, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, T.T.; Zou, Y.H.; Zhang, X.H.; Li, D.H.; Guo, X.X.; Yang, D.J. Hydrogen Bond Interpenetrated Agarose/PVA Network: A Highly Ionic Conductive and Flame-Retardant Gel Polymer Electrolyte. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 9856–9864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.W.; Ji, Y.C.; Song, H.R.; Chen, S.M.; Ding, S.X.; Zhang, B.K.; Yang, L.Y.; Song, Y.L.; Pan, F. Insights into the interfacial degradation of high-voltage all-solid-state lithium batteries. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Xu, X.; Jiang, S.; Xi, K.; Zhang, L.H.; Lan, Y.L.; Yin, J.Q.; Wu, H.H.; Gao, Y.F. Zeolitic imidazolate framework upgrading polyethylene oxide composite electrolyte for high-energy solid-state lithium batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 630, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, E.Q.; Guo, Y.D.; Xin, Y.; Xu, G.R.; Guo, X.W. Enhanced electrochemical properties and interfacial stability of poly(ethylene oxide) solid electrolyte incorporating nanostructured Li1.3Al0.3Ti1.7(PO4)3 fillers for all solid state lithium ion batteries. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 45, 6876–6887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Gao, H.; Li, C.; Huang, J.X.; Liu, P.B. 3D glass fiber cloth reinforced polymer electrolyte for solid-state lithium metal batteries. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 621, 118940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.; Zhu, L.; Xu, J.N.; Jing, M.X.; Yao, S.S.; Shen, X.Q.; Li, S.J.; Tu, F.Y. Boosting the performance of poly (ethylene oxide)-based solid polymer electrolytes by blending with poly (vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) for solid-state lithium-ion batteries. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 7831–7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.J.; Wang, J.Y.; Zhang, Z.H.; Wu, L.B.; Yao, L.L.; Wei, Z.Y.; Deng, Y.H.; Xie, D.J.; Yao, X.Y.; Xu, X.X. In-situ preparation of poly(ethylene oxide)/Li3PS4 hybrid polymer electrolyte with good nanofiller distribution for rechargeable solid-state lithium batteries. J. Power Sources 2018, 387, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, J.F.; Yu, Z.P.; Guo, X. Composite polymer electrolytes reinforced by two-dimensional layer double-hydroxide nanosheets for dendrite-free lithium batteries. Solid State Ion. 2020, 347, 115275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.W.; Li, F.Q.; Hou, T.Y.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, H.; Wang, H.N.; Li, D.G.; Xu, H.H.; Huang, Y.H. Polymer electrolytes shielded by 2D Li0.46Mn0.77PS3 Li+-conductors for all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2023, 56, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y.F.; Long, X.Y.; Bao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, W.Z.; Cheng, H.S. Hydroxyl-rich single-ion conductors enable solid hybrid polymer electrolytes with excellent compatibility for dendrite-free lithium metal batteries. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 657, 120666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CPEs | Discharge Capacity /mAh g−1 | Cycle Number | Operation Conditions | Capacity Retention | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAF@LCO | 122 | 100 | 0.2 C | 75.1% | [25] |

| / | 100 | 0.5 C | 80.2% | ||

| ZIF-8@CMC | 163.7 | 200 | 0.5 C | 88.95% | [26] |

| LATP | 151.69 | 100 | 0.5 C | 85.05% | [27] |

| GFC | 137.6 | 100 | 0.2 C | 87.3% | [28] |

| PVDF-HFP | 125.3 | 100 | 0.5 C | 89.4% | [29] |

| 2%vol Li3PS4 | 145.2 | 100 | 0.2 C | 86.1% | [30] |

| 133 | 325 | 0.5 C | 80.9% | ||

| 2D LDH | 138 | 100 | 0.2 C | 88% | [31] |

| 5LiMPS | 135.5 | 200 | 0.2 C | 83.6% | [32] |

| 15%SPVA-Li | 158.4 | 100 | 0.2 C | 81.5% | [33] |

| 1.0% ZSM-5 nanosheets | 152.3 | 200 | 0.2 C | 91.4% | This work |

| 149.2 | 350 | 0.5 C | 79.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B. Enhanced Lithium-Ion Transport in Lithium Metal Batteries Using ZSM-5 Nanosheets Hybridized Solid Polymer Electrolytes. Polymers 2024, 16, 1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16111604

Hu X, Liu J, Zhang B. Enhanced Lithium-Ion Transport in Lithium Metal Batteries Using ZSM-5 Nanosheets Hybridized Solid Polymer Electrolytes. Polymers. 2024; 16(11):1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16111604

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Xiaoyan, Jialiang Liu, and Baoquan Zhang. 2024. "Enhanced Lithium-Ion Transport in Lithium Metal Batteries Using ZSM-5 Nanosheets Hybridized Solid Polymer Electrolytes" Polymers 16, no. 11: 1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16111604

APA StyleHu, X., Liu, J., & Zhang, B. (2024). Enhanced Lithium-Ion Transport in Lithium Metal Batteries Using ZSM-5 Nanosheets Hybridized Solid Polymer Electrolytes. Polymers, 16(11), 1604. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16111604