Watermelon Genotypes and Weed Response to Chicken Manure and Molasses-Induced Anaerobic Soil Disinfestation in High Tunnels

Abstract

1. Introduction

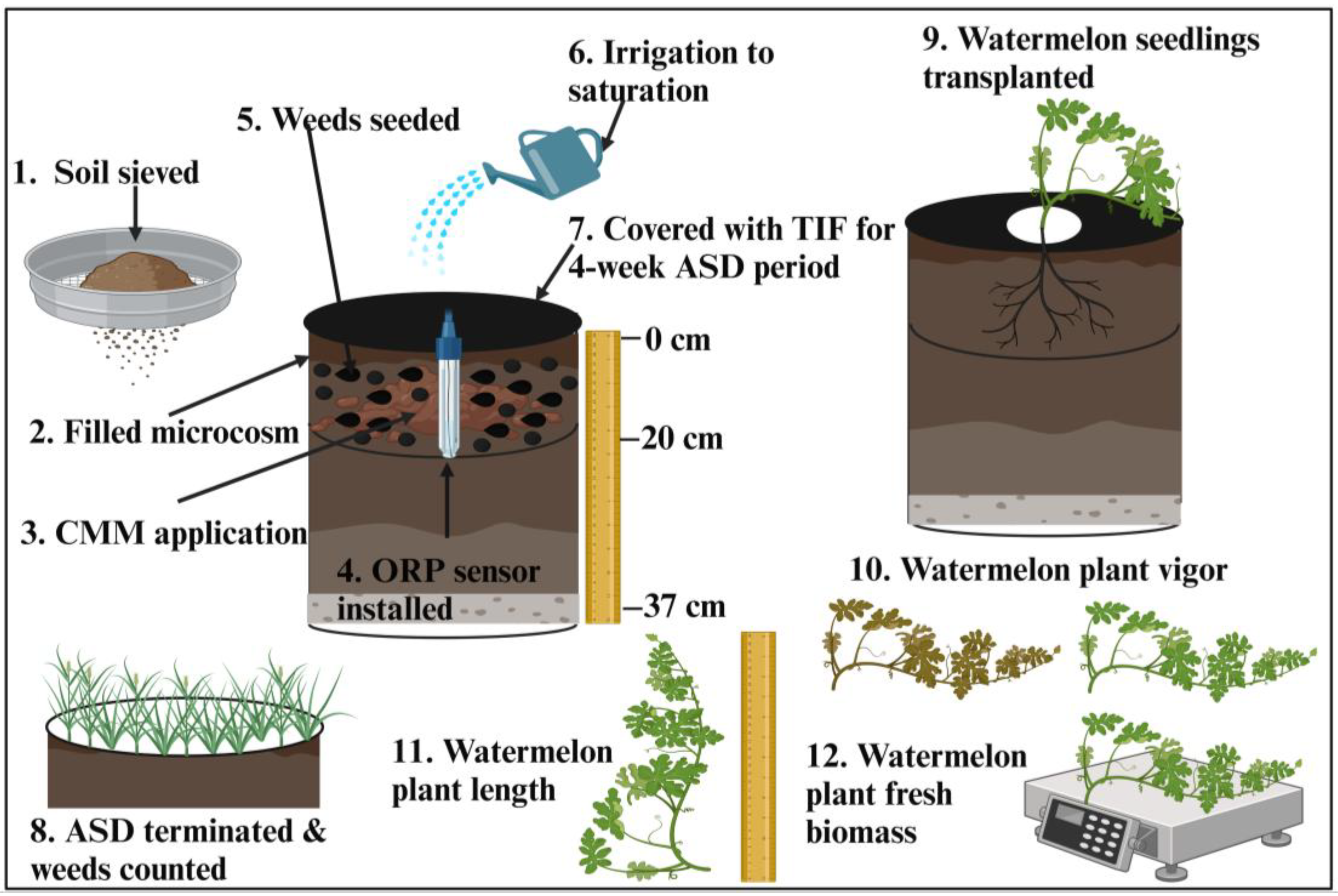

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experiment Location and Experimental Setup

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

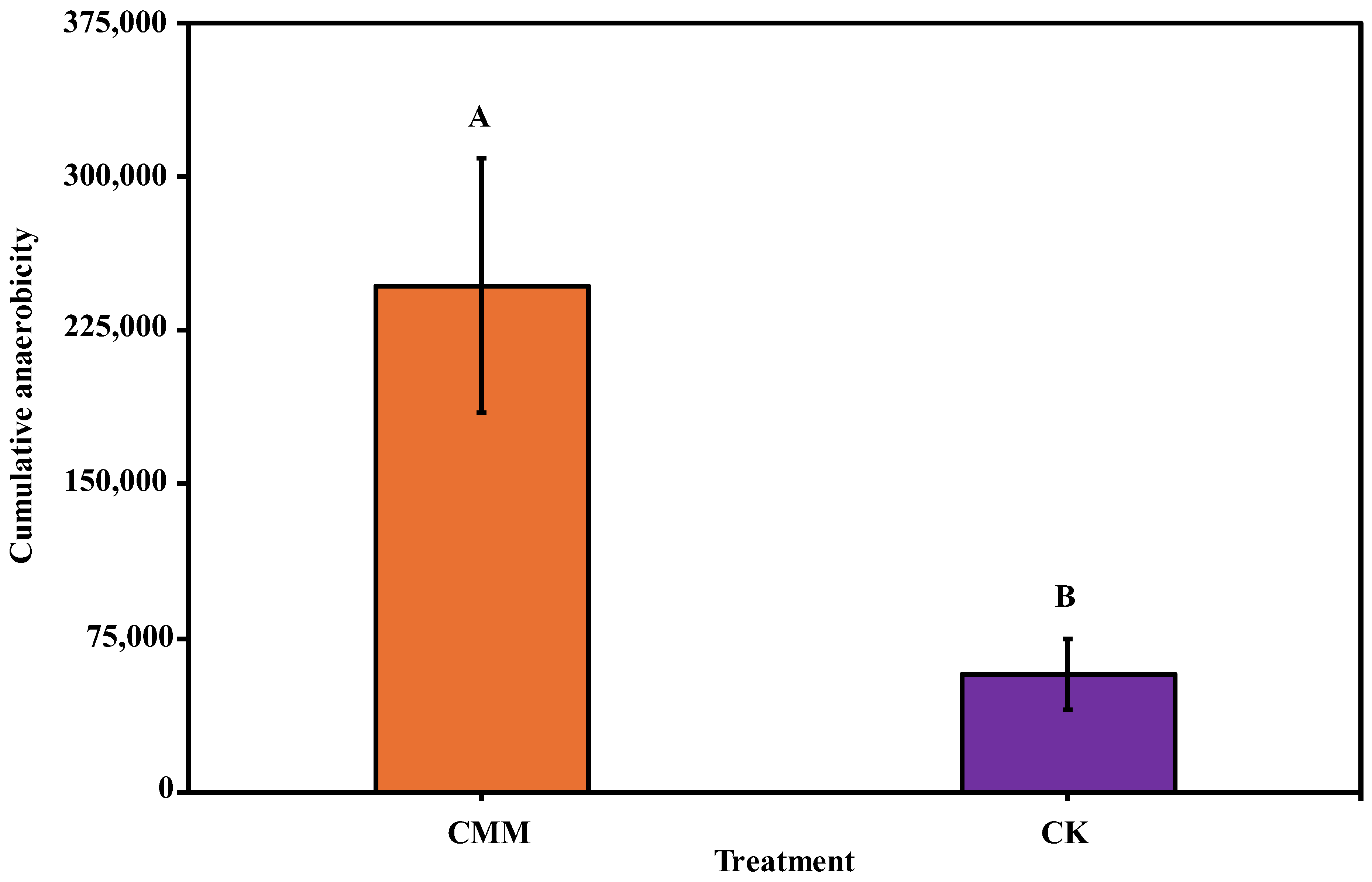

3.1. Impact of Chicken Manure and Molasses-Induced ASD on Cumulative Anaerobicity

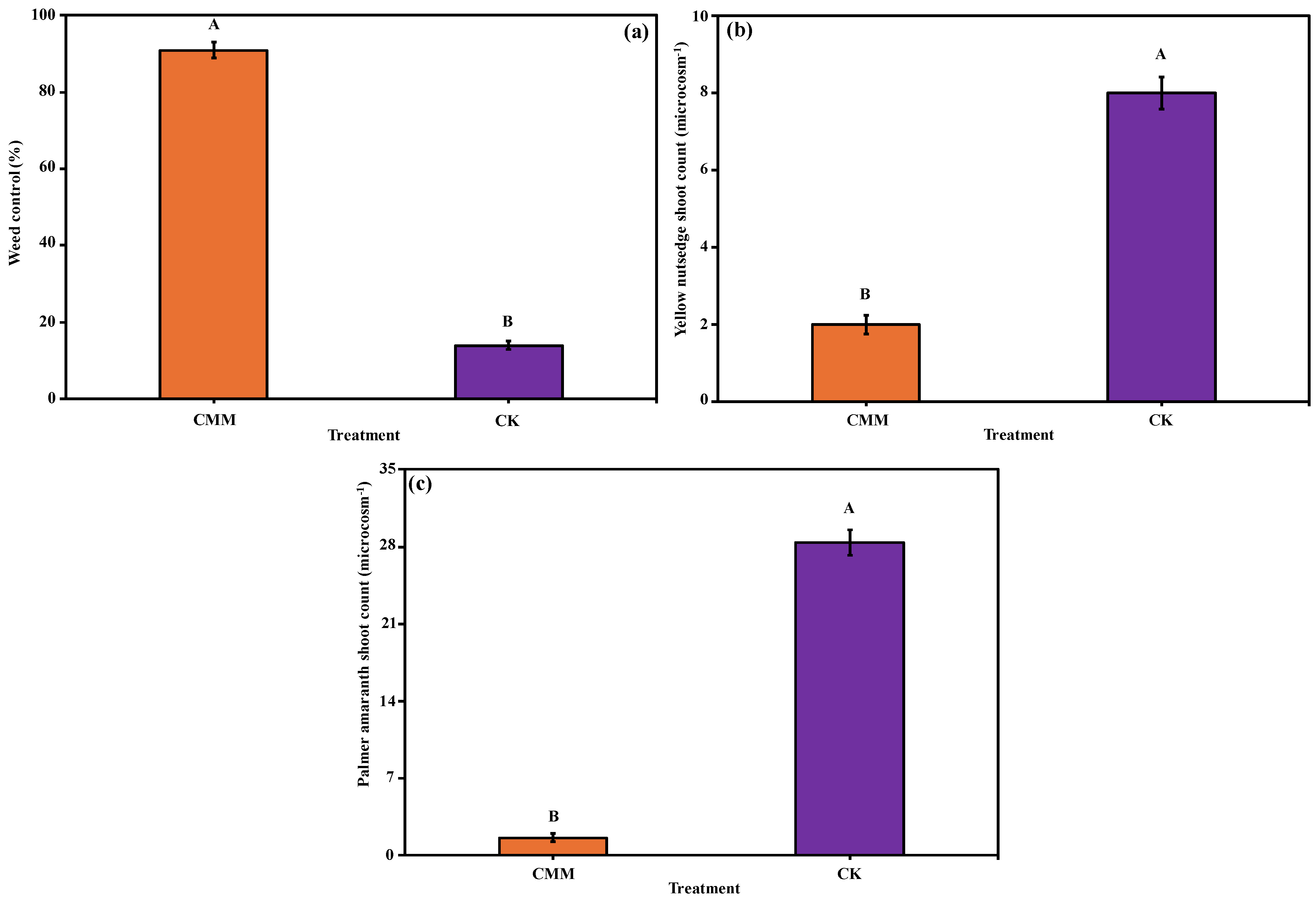

3.2. Impact of Chicken Manure and Molasses-Induced ASD on Weed Control

3.2.1. Percent Weed Control

3.2.2. Weed Counts

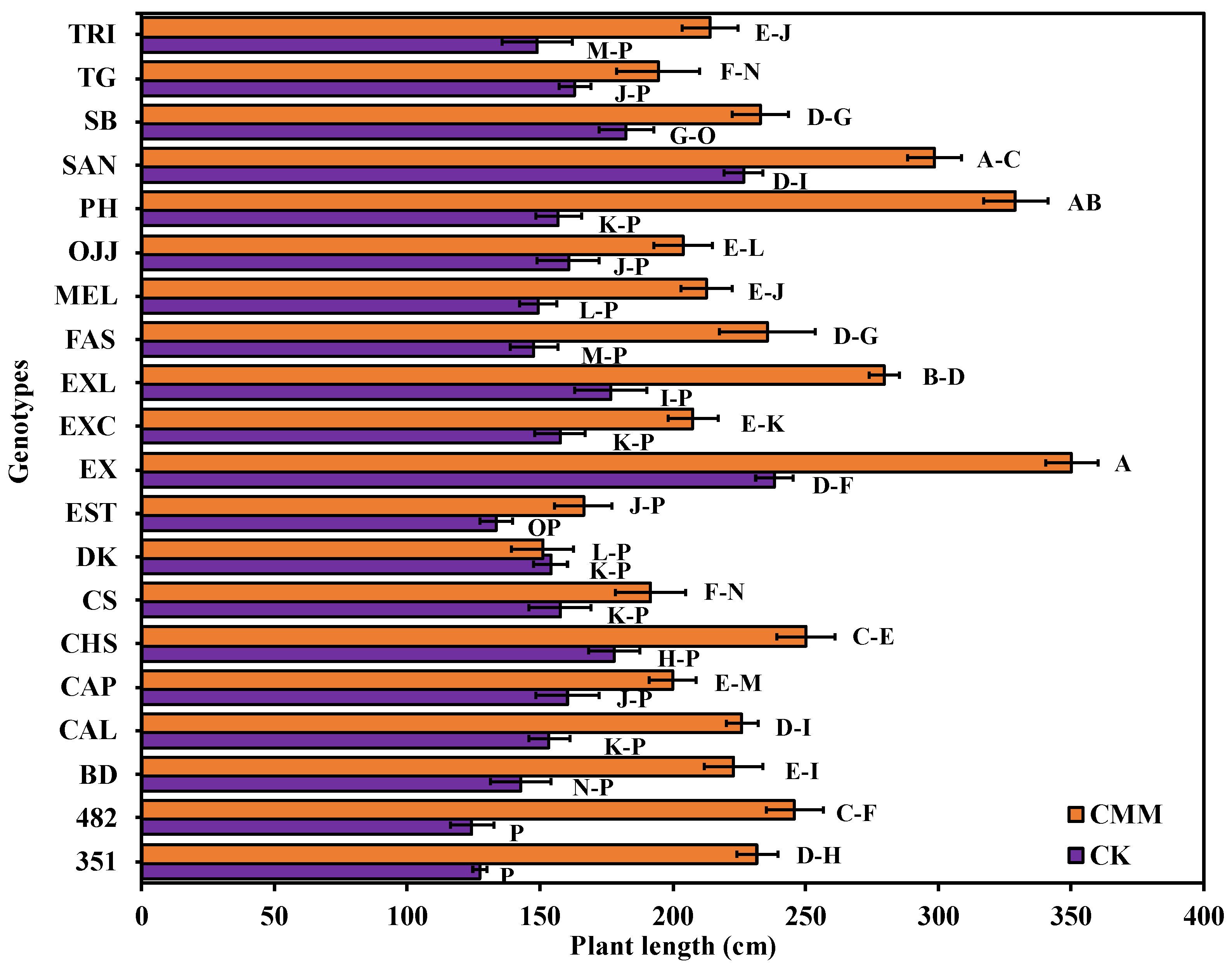

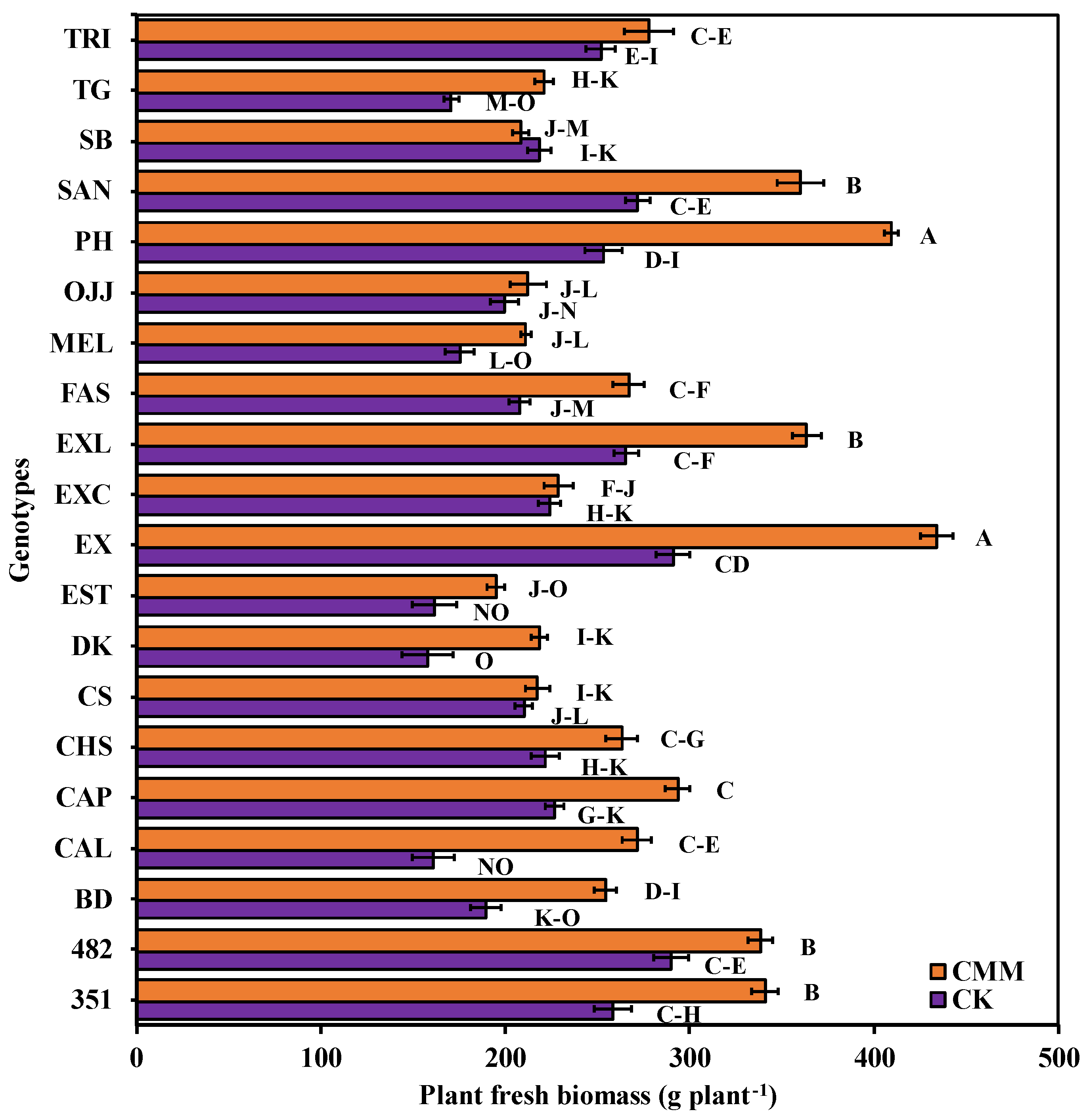

3.3. Impact of Chicken Manure and Molasses-Induced ASD on Watermelon Gentoypes Plant Vigor, Plant Length, and Plant Fresh-Biomass

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- US Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service. Vegetables 2023 Summary (February 2024). 2024. Available online: https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/02870v86p/qz20vd735/ht24z584t/vegean24.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Share of U.S. Watermelon Produced by State, 2021. 2022. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=104374 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Stone, S.P.; Boyhan, G.E.; Johnson, W.C. The impact of weeding regime, planting density, and growth habits on watermelon yield in an organic system. HortTechnology 2019, 29, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culpepper, A.S. UGA Weed Control Programs for Watermelon in 2014. 2014. Available online: https://esploro.libs.uga.edu/esploro/fulltext/report/UGA-weed-control-programs-for-watermelon/9949316466002959?repId=12662096140002959&mId=13662206190002959&institution=01GALI_UGA (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Monks, D.W.; Schultheis, J.R. Critical weed-free period for large crabgrass (Digitaria sanguinalis) in transplanted watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). Weed Sci. 1998, 46, 530–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, D.; McAuslane, H.J.; Adkins, S.T.; Smith, H.A.; Dufault, N.; Webb, S.E. Transmission of Squash vein yellowing virus to and from cucurbit weeds and effects on sweetpotato whitefly (hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) behavior. Environ. Entomol. 2016, 45, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, S.; Webb, S.E.; Baker, C.A.; Kousik, C.S. Squash vein yellowing virus detection using nested polymerase chain reaction demonstrates that the cucurbit weed Momordica charantia is a reservoir host. Plant Dis. 2008, 92, 1119–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Earhart, D.; Baker, M.; Dainello, F.; Haby, V. Interactions of poultry litter, polyethylene mulch, and floating row covers on triploid watermelon. HortTechnology 1998, 9, 128–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.E.; Channell-butcher, C. Effects of row cover and black plastic mulch on yield of ‘au producer’ watermelon on hilled and flat rows. J. Veg. Crop Prod. 1999, 5, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-Jiménez, L.; Munguía-López, J.; Lozano-del Río, A.J.; Zermeño-González, A. Effect of plastic mulch and row covers on photosynthesis and yield of watermelon. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2005, 45, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wychen, L. Survey of the most common and troublesome weeds in broadleaf crops, fruits & vegetables in the United States and Canada. Weed Sci. Soc. Am. Natl. Weed Surv. Dataset 2016. Available online: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1370572092640762502 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Webster, T. Weed survey—Southern States: Vegetable, fruit and nut crops subsection (annual weed survey). In Proceedings of the Southern Weed Science Society, Little Rock, AR, USA, 24–27 January 2010; Volume 63, pp. 246–257. [Google Scholar]

- Daugovish, O.; Mochizuki, M.J. Barriers Prevent Emergence of Yellow Nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus) in Annual Plasticulture Strawberry (Fragaria × Ananassa). Weed Technol. 2010, 24, 478–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransom, C.V.; Rice, C.A.; Shock, C.C. Yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus) growth and reproduction in response to nitrogen and irrigation. Weed Sci. 2009, 57, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buker, R.S.; Stall, W.M.; Olson, S.M.; Schilling, D.G. Season-long interference of yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus) with direct-seeded and transplanted watermelon (Citrullus lanatus). Weed Technol. 2003, 17, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, B.A.; Smeda, R.J.; Johnson, W.G.; Kendig, J.A.; Ellersieck, M.R. Comparative growth of six amaranthus species in missouri. Weed Sci. 2003, 51, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norsworthy, J.K.; Griffith, G.M.; Scott, R.C.; Smith, K.L.; Oliver, L.R. Confirmation and control of glyphosate-resistant palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) in arkansas. Weed Technol. 2008, 22, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnoskie, L.M.; Webster, T.M.; Grey, T.L.; Culpepper, A.S. Severed stems of Amaranthus palmeri are capable of regrowth and seed production in Gossypium hirsutum. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2014, 165, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertucci, M.B.; Jennings, K.M.; Monks, D.W.; Schultheis, J.R.; Louws, F.J.; Jordan, D.L. Interference of palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) density in grafted and nongrafted watermelon. Weed Sci. 2019, 67, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bàrberi, P. Weed management in organic agriculture: Are we addressing the right issues? Weed Res. 2002, 42, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianessi, L.P.; Reigner, N.P. The value of herbicides in u.s. crop production. Weed Technol. 2007, 21, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.G.; Everts, K.L. Characterization of a regional population of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum by race, cross pathogenicity, and vegetative compatibility. Phytopathology 2007, 97, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruton, B.; Fish, W.; Zhou, X.; Everts, K.; Roberts, P. Fusarium Wilt in Seedless Watermelons. In Proceedings of the 2007 Southeast Regional Vegetable Conference, Savannah, Georgia, 5–7 January 2007; pp. 93–98. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C41&q=Fusarium+Wilt+in+Seedless+Watermelons.+In+Proceedings+of+the+2007+Southeast+Regional+Vegetable+Conference%2C+5%E2%80%937+January+2007%2C+Savannah%2C+Georgia%2C+2007%3B+pp.+93%E2%80%9398.&btnG= (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Momma, N.; Kobara, Y.; Uematsu, S.; Kita, N.; Shinmura, A. Development of biological soil disinfestations in japan. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 3801–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, U.; Augé, R.M.; Butler, D.M. A meta-analysis of the impact of anaerobic soil disinfestation on pest suppression and yield of horticultural crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D.M.; Rosskopf, E.N.; Kokalis-Burelle, N.; Albano, J.P.; Muramoto, J.; Shennan, C. Exploring warm-season cover crops as carbon sources for anaerobic soil disinfestation (ASD). Plant Soil. 2012, 355, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D.M.; Ownley, B.H.; Dee, M.E.; Eichler Inwood, S.E.; McCarty, D.G.; Shrestha, U.; Kokalis-Burelle, N.; Rosskopf, E.N. Low carbon amendment rates during anaerobic soil disinfestation (ASD) at moderate soil temperatures do not decrease viability of sclerotinia sclerotiorum sclerotia or fusarium root rot of common bean. Acta Hortic. 2014, 1044, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewavitharana, S.S.; Ruddell, D.; Mazzola, M. Carbon source-dependent antifungal and nematicidal volatiles derived during anaerobic soil disinfestation. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 140, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, S.L.; Kluepfel, D.A. Anaerobic soil disinfestation: A chemical-independent approach to pre-plant control of plant pathogens. J. Integr. Agric. 2015, 14, 2309–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Ward, B.K.; Wechter, W.P.; Katawczik, M.L.; Farmaha, B.S.; Suseela, V.; Cutulle, M.A. Assessment of agro-industrial wastes as a carbon source in anaerobic disinfestation of soil contaminated with weed seeds and phytopathogenic bacterium (Ralstonia solanacearum) in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). ACS Agric. Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Rutter, W.; Wadl, P.A.; Campbell, H.T.; Khanal, C.; Cutulle, M. Effectiveness of anaerobic soil disinfestation for weed and nematode management in organic sweetpotato production. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, S.; Vepraskas, M.J.; Richardson, J. Soil redox potential: Importance, field measurements, and observations. Adv. Agron. 2007, 94, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gioia, F.; Ozores-Hampton, M.; Hong, J.; Kokalis-Burelle, N.; Albano, J.; Zhao, X.; Black, Z.; Gao, Z.; Wilson, C.; Thomas, J.; et al. The effects of anaerobic soil disinfestation on weed and nematode control, fruit yield, and quality of florida fresh-market tomato. Horts 2016, 51, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Cutulle, M.; Rutter, W.; Wadl, P.A.; Ward, B.; Khanal, C. Anaerobic soil disinfestation as a tool for nematode and weed management in organic sweetpotato. Agronomy 2025, 15, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Di Gioia, F.; Zhao, X.; Ozores-Hampton, M.; Swisher, M.E.; Hong, J.; Kokalis-Burelle, N.; DeLong, A.N.; Rosskopf, E.N. Optimizing anaerobic soil disinfestation for fresh market tomato production: Nematode and weed control, yield, and fruit quality. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 218, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D.M.; Kokalis-Burelle, N.; Albano, J.P.; McCollum, T.G.; Muramoto, J.; Shennan, C.; Rosskopf, E.N. Anaerobic soil disinfestation (asd) combined with soil solarization as a methyl bromide alternative: Vegetable crop performance and soil nutrient dynamics. Plant Soil. 2014, 378, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Wechter, W.P.; Farmaha, B.S.; Cutulle, M. Integration of halosulfuron and anaerobic soil disinfestation for weed control in tomato. Hortte 2022, 32, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D.M.; Kokalis-Burelle, N.; Muramoto, J.; Shennan, C.; McCollum, T.G.; Rosskopf, E.N. Impact of anaerobic soil disinfestation combined with soil solarization on plant–parasitic nematodes and introduced inoculum of soilborne plant pathogens in raised-bed vegetable production. Crop Prot. 2012, 39, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, K.; Kortman, S.; Duque, J.; Muramoto, J.; Shennan, C.; Greenstein, G.; Haffa, A.L.M. Analysis of trace volatile compounds emitted from flat ground and formed bed anaerobic soil disinfestation in strawberry field trials on california’s central coast. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momma, N. Studies on mechanisms of anaerobicity-mediated biological soil disinfestation and its practical application. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2015, 81, 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runia, W.T.; Thoden, T.C.; Molendijk, L.P.G.; Van Den Berg, W.; Termorshuizen, A.J.; Streminska, M.A.; Van Der Wurff, A.W.G.; Feil, H.; Meints, H. Unravelling the mechanism of pathogen inactivation during anaerobic soil disinfestation. Acta Hortic. 2014, 1044, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, R.B.; Marasini, M.; Rawal, R.; Testen, A.L.; Miller, S.A. Effects of anaerobic soil disinfestation carbon sources on soilborne diseases and weeds of okra and eggplant in nepal. Crop Prot. 2020, 135, 104846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Massart, S.; Yan, D.; Cheng, H.; Eck, M.; Berhal, C.; Ouyang, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cao, A. Composted chicken manure for anaerobic soil disinfestation increased the strawberry yield and shifted the soil microbial communities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardi, G.; Pugliese, M.; Gullino, M.L.; Garibaldi, A. Evaluation of different carbon sources for anaerobic soil disinfestation against rhizoctonia solani on lettuce in controlled production systems. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2020, 59, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, U.; Rosskopf, E.N.; Butler, D.M. Effect of anaerobic soil disinfestation amendment type and c:n ratio on Cyperus esculentus tuber sprouting, growth and reproduction. Weed Res. 2018, 58, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momma, N. Biological soil disinfestation (bsd) of soilborne pathogens and its possible mechanisms. JARQ 2008, 42, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adcock, C.W.; Foshee, W.G.; Wehtje, G.R.; Gilliam, C.H. Herbicide combinations in tomato to prevent nutsedge (cyperus esulentus) punctures in plastic mulch for multi-cropping systems. Weed Technol. 2008, 22, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Payan, J.P.; Santos, B.M.; Stall, W.M.; Bewick, T.A. Effects of purple nutsedge (Cyperus rotundus) on tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) and bell pepper (Capsicum annuum) vegetative growth and fruit yield. Weed Technol. 1997, 11, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Ward, B.; Levi, A.; Cutulle, M. Weed management by in situ cover crops and anaerobic soil disinfestation in plasticulture. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Samtani, J.; Johnson, C.; Zhang, X.; Butler, D.M.; Derr, J. Brewer’s spent grain with yeast amendment shows potential for anaerobic soil disinfestation of weeds and pythium irregulare. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, R.B.; Sanabria-Velazquez, A.D.; Cardina, J.; Miller, S.A. Evaluation of anaerobic soil disinfestation for environmentally sustainable weed management. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feys, J.; Reheul, D.; De Smet, W.; Clercx, S.; Palmans, S.; Van De Ven, G.; De Cauwer, B. Effect of anaerobic soil disinfestation on tuber vitality of yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus). Agriculture 2023, 13, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmon, Y.; Fernández-Bayo, J.D.; Hernandez, K.; McCurry, D.G.; Harrold, D.R.; Su, J.; Dahlquist-Willard, R.M.; Stapleton, J.J.; VanderGheynst, J.S.; Simmons, C.W. Weed seed inactivation in soil mesocosms via biosolarization with mature compost and tomato processing waste amendments. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Samtani, J.B.; Johnson, C.S.; Butler, D.M.; Derr, J. Weed control assessment of various carbon sources for anaerobic soil disinfestation. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2020, 20, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testen, A.L.; Miller, S.A. Carbon source and soil origin shape soil microbiomes and tomato soilborne pathogen populations during anaerobic soil disinfestation. Phytobiomes J. 2018, 2, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, D.G.; Eichler Inwood, S.E.; Ownley, B.H.; Sams, C.E.; Wszelaki, A.L.; Butler, D.M. Field evaluation of carbon sources for anaerobic soil disinfestation in tomato and bell pepper production in tennessee. Horts 2014, 49, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Origin | Soil Texture | Organic Matter (%) | Soil pH | P (lbs/A) | K (lbs/A) | Ca (lbs/A) | Mg (lbs/A) | Zn (lbs/A) | Mn (lbs/A) | Cu (lbs/A) | B (lbs/A) | Na (lbs/A) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charleston, SC | Sandy loam | 2.4 | 6.3 | 65 | 205 | 1123 | 198 | 4.8 | 16 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 52 |

| Genotypes | Abbreviation | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Tri-X-313 | TRI | Triploid |

| Captivation | CAP | Triploid |

| Dark Knight | DK | Triploid |

| Estrella | EST | Triploid |

| Extazy | EX | Triploid |

| Excursion | EXC | Triploid |

| Exclamation | EXL | Triploid |

| Fascination | FAS | Triploid |

| Melody | MEL | Triploid |

| Powerhouse | PH | Triploid |

| Calhoun Gray | CAL | Diploid |

| Black Diamond | BD | Diploid |

| Charleston Gray | CHS | Diploid |

| Crimson Sweet | CS | Diploid |

| Sangria | SAN | Diploid |

| Sugar Baby | SB | Diploid |

| Top Gun | TG | Diploid |

| Ojjakkyo | OJJ | Watermelon (rootstock) |

| USVL-351 | 351 | Bottle gourd (rootstock) |

| USVL-482 | 482 | Bottle gourd (rootstock) |

| Treatment | Genotypes | Plant vigor Estimate (0–10) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 DAT | 14 DAT | 28 DAT | ||

| CMM | 351 | 4.6 D–J | 5.3 E–I | 6.5 B–D |

| CK | 4.6 E–J | 4.7 F–K | 5.2 C–H | |

| CMM | 482 | 5.5 A–I | 5.5 D–H | 6.8 A–C |

| CK | 5.6 A–H | 5.0 E–K | 4.7 D–I | |

| CMM | BD | 4.2 H–J | 4.5 H–L | 5.7 C–G |

| CK | 4.6 D–J | 4.6 H–K | 3.7 H–J | |

| CMM | CAL | 4.6 E–J | 4.7 F–K | 5.9 C–F |

| CK | 4.6 D–J | 4.6 G–K | 4.0 G–J | |

| CMM | CAP | 4.1 IJ | 4.0 KL | 5.2 C–H |

| CK | 4.0 J | 4.0 KL | 4.1 F–J | |

| CMM | CHS | 4.2 H–J | 4.4 I–L | 5.6 C–H |

| CK | 4.1 IJ | 4.1 J–L | 4.3 E–J | |

| CMM | CS | 4.6 E–J | 4.9 E–K | 5.5 C–H |

| CK | 4.7 D–J | 4.7 F–K | 4.0 G–J | |

| CMM | DK | 5.1 I | 4.9 E–K | 4.7 D–I |

| CK | 4.6 D–J | 4.6 G–K | 4.5 E–J | |

| CMM | EST | 3.8 J | 4.0 KL | 4.4 E–J |

| CK | 4.3 G–J | 4.2 J–L | 3.3 IJ | |

| CMM | EX | 6.4 AB | 6.7 A–C | 8.5 A |

| CK | 6.0 A–E | 5.7 C–F | 5.6 C–G | |

| CMM | EXC | 4.3 H–J | 4.3 I–L | 5.7 C–G |

| CK | 5.0 B–J | 4.7 F–K | 3.7 H–J | |

| CMM | EXL | 6.4 AB | 7.2 A | 8.3 AB |

| CK | 5.8 A–F | 5.6 D–G | 5.6 C–G | |

| CMM | FAS | 4.8 C–J | 4.7 F–K | 5.3 C–H |

| CK | 4.5 F–J | 4.4 I–L | 4.6 E–I | |

| CMM | MEL | 4.3 H–J | 5.1 E–J | 5.0 C–E |

| CK | 4.7 D–J | 4.6 H–K | 4.4 E–J | |

| CMM | OJJ | 3.7 J | 3.5 L | 4.6 E–J |

| CK | 4.7 D–J | 4.4 I–L | 2.6 D–I | |

| CMM | PH | 6.3 A–C | 6.8 AB | 8.4 A |

| CK | 6.1 A–D | 6.3 A–D | 5.7 C–G | |

| CMM | SAN | 6.6 A | 7.2 A | 8.4 A |

| CK | 5.7 A–G | 5.9 B–E | 5.4 C–H | |

| CMM | SB | 5.2 A–J | 5.0 E–K | 5.3 C–H |

| CK | 4.5 F–J | 4.2 I–L | 4.2 F–J | |

| CMM | TG | 3.8 J | 4.4 I–L | 5.3 C–H |

| CK | 4.6 D–J | 4.6 H–K | 4.0 G–J | |

| CMM | TRI | 5.0 B–J | 5.3 E–I | 6.8 A–C |

| CK | 5.2 A–J | 4.6 H–K | 5.1 C–I | |

| p value | ||||

| Treatment | 0.5753 | <0.0001 * | <0.0001 * | |

| Genotypes | <0.0001 * | <0.0001 * | <0.0001 * | |

| Treatment × Genotypes | 0.0121 * | <0.0001 * | 0.0016 * | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chattha, M.S.; Ward, B.K.; Kousik, C.S.; Levi, A.; Farmaha, B.S.; Marshall, M.W.; Bridges, W.C.; Cutulle, M.A. Watermelon Genotypes and Weed Response to Chicken Manure and Molasses-Induced Anaerobic Soil Disinfestation in High Tunnels. Agronomy 2025, 15, 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15030705

Chattha MS, Ward BK, Kousik CS, Levi A, Farmaha BS, Marshall MW, Bridges WC, Cutulle MA. Watermelon Genotypes and Weed Response to Chicken Manure and Molasses-Induced Anaerobic Soil Disinfestation in High Tunnels. Agronomy. 2025; 15(3):705. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15030705

Chicago/Turabian StyleChattha, Muhammad Sohaib, Brian K. Ward, Chandrasekar S. Kousik, Amnon Levi, Bhupinder S. Farmaha, Michael W. Marshall, William C. Bridges, and Matthew A. Cutulle. 2025. "Watermelon Genotypes and Weed Response to Chicken Manure and Molasses-Induced Anaerobic Soil Disinfestation in High Tunnels" Agronomy 15, no. 3: 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15030705

APA StyleChattha, M. S., Ward, B. K., Kousik, C. S., Levi, A., Farmaha, B. S., Marshall, M. W., Bridges, W. C., & Cutulle, M. A. (2025). Watermelon Genotypes and Weed Response to Chicken Manure and Molasses-Induced Anaerobic Soil Disinfestation in High Tunnels. Agronomy, 15(3), 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15030705