Abstract

Since China entered the 21st century, a phenomenon of return migrants moving back from urban to rural areas has been noted, especially in central regions such as Hubei Province. Despite its significance, this phenomenon remains inadequately understood. Employing ethnographic research methods, we conducted multiple rounds of fieldwork in Guangzhou, Wuhan, and three of Wuhan’s neighbouring county-level cities—Hanchuan, Xiantao, and Tianmen—where rising garment industrial enclaves and return migration have been observed. Our findings reveal that the pro-growth policies of megacities like Wuhan and Guangzhou, aimed at industrial transformation while eliminating ‘low-end’ manufacturing, have forced migrants to leave large cities. Among these individuals, return-migrant entrepreneurs (RMEs), comprising entrepreneurs and family workshop owners, have had a profound impact on advancing county urbanisation in Hubei Province. Specifically, we identified three features for return-migrant urbanisation. First, entrepreneurs took their return as an opportunity to expand and promote their businesses, thereby fostering industrialisation in Hanchuan. Second, local state activities in Xiantao, encompassing the construction of highways, logistics systems, and other facilities, coupled with institutionalised arrangements, triggered return migration and township urbanisation. Third, households and individuals with entrepreneurship dominated the development of the informal workshop industry in Tianmen. Overall, our study contributes to the nuanced understanding of new types of urbanisation in China.

1. Introduction

In the early 21st century, population mobility in China has been marked by a remarkable transformation from rural-to-urban to urban-to-rural flow, which has attracted high attentions [1,2,3,4,5]. The National Population and Family Planning Commission claimed that the number of Chinese migrants migrating from rural to urban areas has declined annually since 2015, and approximately 22.8 percent of the migrants returned in 2017 [6]. According to data from the Seventh Census of China [7], there is a significant trend of return migration from coastal regions, such as the Pearl River Delta and Yangtze River Delta, and large cities, such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Wuhan, towards small townships or even villages in the central and western regions of China. For example, in Hubei Province, located in the central region of China, over 210,000 rural migrants have returned to their hometowns and villages since 2018 [8]. Return migrants, especially return-migrant entrepreneurs (RMEs), may become a new driving force to promote the development of inland China [3,9].

Nevertheless, in China, the literature centring on the urbanisation of coastal areas has been dominant, shedding light on the importance of rural migrants characterised by their one-way movement from central and western regions to the eastern regions, as well as from the countryside to large cities [10,11]. Few studies have paid attention to the new types of urbanisation in Central and Western China, such as return-migrant urbanisation. In the 1980s, three types of urbanisation emerged in post-reform China [12]: the ‘Sunan model’, driven by the development of the rural collective economy [13,14]; the ‘Wenzhou model’, dominated by local private family enterprises and characterised by the development of the traditional manufacturing industry [15]; and the ‘Pearl River Delta model’, in which Guangdong Province achieved its economic take-offs through investment from Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan [16]. However, it has recently been observed that return migration has grown and plays an increasing role in promoting urbanisation in inland China [17]. Thus, more efforts should be made to examine the impact of return migrants on the urbanisation of their homelands to further develop a nuanced understanding of China’s new types of urbanisation.

In academia, return migration is defined as the repatriation of migrants to their origin countries for resettlement, a process that may serve as a driving force of hometown developments. This concept transcends the prevailing assumption advocated by transnationalists and mobilities paradigms that return is solely a part of circular migration [18,19]. The literature focuses on two types of return migrants: successful and failed returnees [20,21,22]. Evidence from developed countries such as the United States articulates the positive impact of successful returnees on their hometowns [23]. Successful returnees are believed to be well-trained in both technology and knowledge because of their working experience in developed countries [24]. After returning, return migrants may lead the economic development of their hometowns or villages by making use of capital and skills accumulated during migration [25,26]. However, the literature on migrants in developing countries claims that most migrants are so-called failed migrants, who form part of marginalised groups in host cities due to a lack of education and work experience. Thus, they may have a limited or even negative impact on their hometowns after returning [20,27]. However, this ‘success–failure’ dichotomy is problematic, as it is just concerned with the capital accumulation of migrants during their migration, while other key factors, such as their entrepreneurial spirit, local policies, or the market resources of their hometowns, are ignored.

Low-capital returnees can play a crucial role in promoting the development of their hometowns, particularly in the Chinese context. Since 2014, against the backdrop of ‘people-centred’ urbanisation, the loosening of the hukou system1 and the enhancement of social integration by the central government have improved the living standards of migrants in host cities [28,29]. Along with the coverage of various forms of social welfare such as education, medical security, and affordable housing, rural migrants no longer have to engage in the so-called three-D jobs (dirty, dangerous, and difficult) [30,31,32] and accumulate more economic capital and skills in host cities [33]. Meanwhile, the emergence of new developmental opportunities in Central and Western China have begun to attract rural migrants. Accordingly, there is a trend of migrants returning with economic capital or even entrepreneurships.

However, little is known about the impact of this wave of return migrants on hometown development. To fill this gap, this study focuses on the relationship between return migration and county-level urbanisation in Central China. First, we articulate the entrepreneurial behaviours of rural migrants and their impact on the urbanisation of their homelands. Second, in addition to the individual or collective behaviours of return migrants, we are concerned with the actions and attitudes of local states, as well as the policies they have adopted.

This study aims to answer the following questions: What are the characteristics of return migrants and RMEs? What are their impacts on the urbanisation of their homelands? What are the policy implications of this phenomenon? To answer these questions, our study is built upon five-year fieldwork, surveys, and interviews conducted in Guangzhou, Wuhan, and its neighbouring county-level cities, namely, Hanchuan, Xiantao, and Tianmen, taking advantage of first-hand survey data, including interview recordings, official reports, and news reports, to reveal the dynamics as well as the impacts of return-migrant urbanisation in China.

The paper consists of six sections. Following the introduction is a literature review on return migration and urbanisation against various contexts, focusing on the contribution of RMEs to urbanisation. Section 3 discusses the three cases in our empirical study. Section 4 introduces the characteristics of RMEs in Central China, particularly in the three cases. Section 5 examines the relationship between RMEs and urbanisation and further discloses the effects of RMEs on county-level urbanisation. Section 6 summarises the main findings and sheds light on their implications.

2. Understanding the Relations between Return Migration and Urbanisation

2.1. Impact of Return Migration on Urbanisation across Different Contexts

In recent decades, the trend of return immigration has attracted significant attention because of its increasing scale and importance in many countries [34,35]. Return migration is characterized by migrants who, largely motivated by economic and social advancements in their origin countries, opt to return and resettle therein [18,19]. The impact of returnees on their hometowns has been widely noted [20]; however, there are two opposing arguments. First, studies conducted in developed countries such as the United States and Canada claim that returnees who moved back to developing countries would bring back capital, work skills, and advanced ideas and have a positive influence on their home communities [36,37]. In the study of intra-European immigrants, it was found that returnees would significantly promote the operation of innovative farms and small-sized enterprises in their homelands by exploiting ‘modern’ work habits and their savings accumulated abroad [38]. Most of the literature articulates the beneficial impact of returnees on their countries of origin [39,40].

Second, empirical studies conducted in developing countries may reject the idea that returnees benefit from the accumulation of developed skills [27,41]. For instance, in Mexico, the technical or industrial skills acquired in developed countries cannot be applied to migrant homelands wherein the agricultural sector is dominant [39]. Moreover, most immigrants are employed in unskilled jobs abroad, and few return with skills that matter to the economic development of their hometowns [20]. For example, more than 90 percent of Turkish returnees are not skilled workers [42]. It has also been suggested that the return migration observed in Thailand and Vietnam had a limited effect on the development of the migrants’ hometowns [43].

There are different perspectives on the impact of returnees on their home cities, towns, or villages in developed or developing countries, most of which are in line with the classical success–failure dichotomy in the extant literature. Nevertheless, there is a consensus that successful returnees tend to have a positive effect on their home communities, while failed returnees may have a slight or even negative impact on their regions of origin [20]. In this vein, the literature has further examined the behaviours of successful returnees, especially their entrepreneurial behaviour after returning [44]. Some have stated that successful returnees, especially young and well-educated ones, are more sensitive to market turbulence than other migrants when they are self-employed [45,46]. Moreover, it has been found that the successful returnees alleviate the deficiencies in credit markets and human capital at home by starting businesses [47]. However, less attention has been paid to the behaviours or actions of so-called failed returnees.

Therefore, such a success–failure dichotomy is problematic [48], as it simply assumes that successful returnees have a positive impact on their homelands, and vice versa. This dichotomy seeks to assess the returnees’ financial capital, social capital, and technologies, which have been proven to be the drivers behind the socioeconomic development of the migrants’ homelands, regardless of the actions they have taken due to the new development opportunities emerging in their homelands.

2.2. Decoding Return-Migrant Urbanisation in China

Owing to China’s specific political and economic context, return migration and its dynamics have been highly concerned by recent literature. First, extant studies on return migration have mainly focused on hukou policies, indicating that rural migrants are not only excluded by the urban welfare system, yet also marginalized by the mainstream labour market due to their lack of education and professional skills [49].

Second, since the beginning of the 21st century, structural unemployment caused by industrial restructuring has led to forced return of migrant workers [50]. For example, in Eastern China, some large cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou are seeking to acquire ‘global city’ status, implementing a new wave of sectoral upgrading, that is, the implementation of a new strategy of state-oriented promotion of high-tech industries such as AI, IT, advanced manufacturing, and so on, along with the exclusion of so-called ‘low-end sectors’. As a result, some low-end sector workers must face unemployment and are forced to return to their home cities, townships, or villages [51].

Third, the ‘Regional Coordinated Development’ strategy enacted by the Chinese central government has recently further narrowed the disparity between the central and western regions and the east. Specifically, a series of new policies, such as ‘New-type Urbanisation’ and ‘Rural Revitalisation’, have positively promoted the development of the central and western regions—such as via the construction of a set of infrastructures including highways, railways, logistics, etc., generating some new opportunities for attracting return migration—as well as the low-end sectors and the widespread application of e-commerce [52]. Therefore, there is a new type of so-called return-migrant urbanisation appearing in China’s inland regions. We argue that such urbanisation is notably characterised by return migrants, especially RMEs, as they bring capital, technology, and advanced ideas back to their homes and further promote the urbanisation process in China’s inland regions.

A number of empirical studies have shed light on topics such as the reasons for return migration, the employment statuses of return migrants, and their residential choices after returning [49,53]. However, few studies have noted the impact of return migration on the urbanisation of their hometowns, especially in the central and western regions of China. Based on a survey conducted in seven provinces, scholars have examined the influence of return migrants on their sending areas and pointed out that returnees with urban work experience are likely to engage in non-agricultural activities after returning [49]. Using data from the 2010 China General Social Survey (CGSS2010), it was found that interprovincial return migrants in coastal regions are more likely to settle in cities or towns, as their urban settlement decisions are highly relevant to engagement in non-agricultural employment [48]. Along with the rise in investments in rural areas, especially in coastal regions like Fujian Province, the growth of e-commerce, rural tourism, and other factors, a number of migrants return to their hometowns to start businesses, such as joint household enterprises or township enterprises [52], and further accelerate the modernisation process in their home communities [54,55,56].

Nevertheless, most studies on return migration and its impacts on urbanisation have focused on coastal regions of China, where rural industries are well developed [56]. Little is known about the interplay between return migration and the urbanisation of the areas from which migrants emigrate, especially in Central or Western China. To fill this gap, we should explore the diverse returning groups, including their reasons for returning, dynamic processes, and entrepreneurial behaviours, to develop a nuanced understanding of county-level urbanisation in Central and Western China.

3. Research Area and Data Collection

3.1. Study Area

This study is based on an examination of three county-level cities near Wuhan, namely, Hanchuan, Xiantao, and Tianmen, known for their increasing number of return migrants and garment industries in coastal regions such as Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hangzhou, and provincial-level cities such as Wuhan. The three aforementioned county-level cities have deeply established clothing production culture and technology. For instance, before the 1950s, there were more than 5000 tailors working in the rural areas of Hanchuan. After 1949, state-owned garment factories, cotton mills, and military enterprises were put into operation in Hanchuan, where garment enterprises employed more than 10,000 people. Second, the development of Tianmen’s garment industry largely depends on the local cotton-planting industry, which accounts for 10% of China’s annual output and promotes the growth of both textile technology and the cotton-planting industry chain. More than 300 garment enterprises in Tianmen are currently engaged in clothing fabric production. Third, Maozui Town, located in the northwest of Xiantao City, is known as the so-called hometown of sewing and has also been called the capital of women’s pants in recent years by the garment industry.

In the last three or four decades, China’s high-speed urbanisation has attracted a large labour force and rural migrants to its coastal regions. In this vein, the three cases have sent large numbers of garment workers to coastal areas. As a result, some large-scale Hubei migrant settlements appeared in major cities, such as Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Wuhan. For example, Hanzheng Street, located in the central area of Wuhan, was a nationwide market that included more than 60 specialised markets in the 1990s, gathering more than 300,000 kinds of commodities and attracting migrants from Hanchuan, Xiantao, and other places in Hubei Province to engage in clothing production and sales. Kangle Village, or Xiaohubei (XHB) village, a typical migrant agglomeration area in Guangzhou, is known for its garment production, and it is an area where more than 50,000 rural migrants from Hubei Province gather, with 60 percent of the migrants stemming from Tianmen and 25 percent coming from Xiantao [57]. However, a gradual change has occurred in recent years, as rural migrants have begun to return to their hometowns to pursue employment or even startups. In 2021, more than 3000 textile and garment enterprises were established in Hanchuan. After the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic2 in 2020, more than 500 small- and medium-sized clothing companies returned to Tianmen from Guangzhou, where export trade has been distinctly damaged due to the closure of borders beween China and other countries.

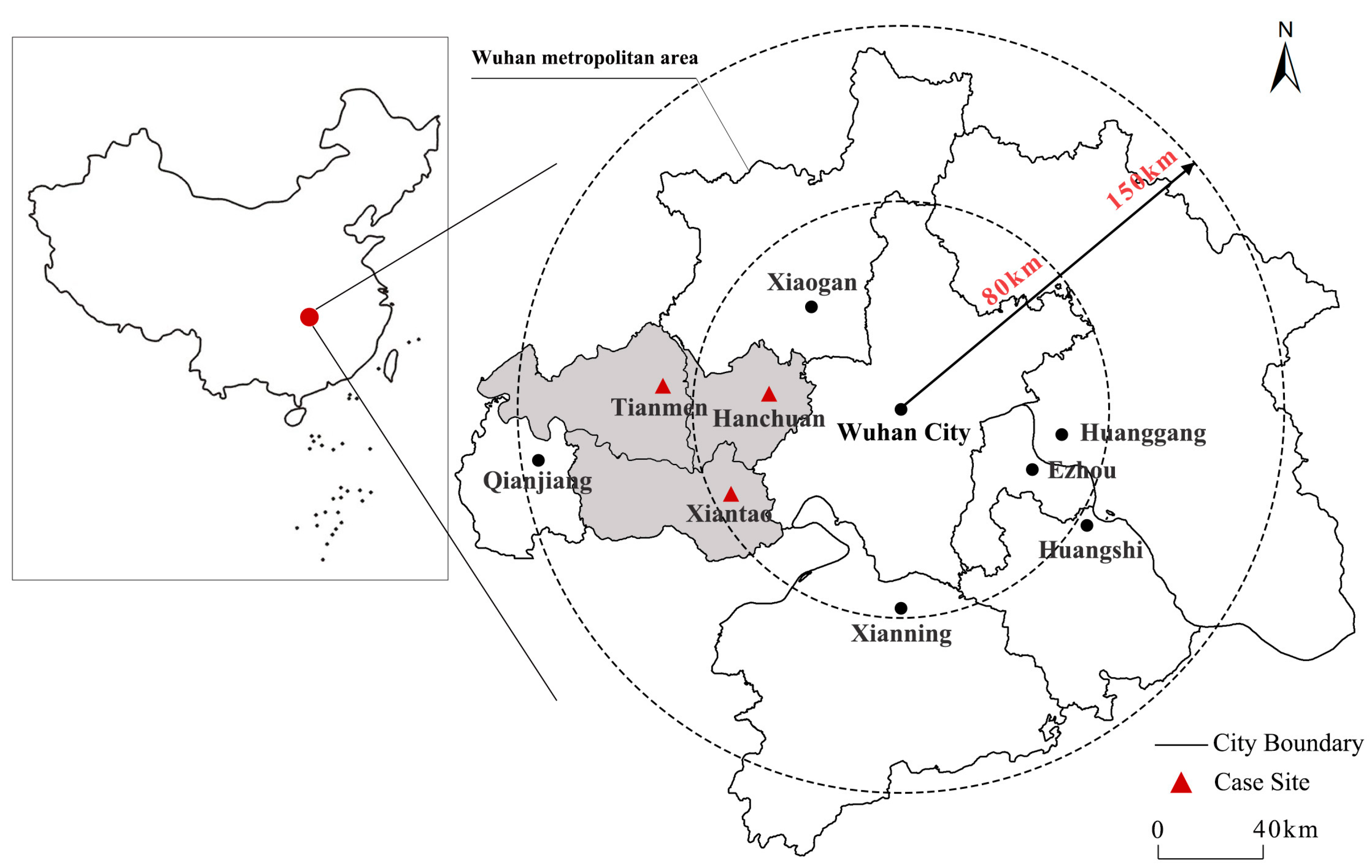

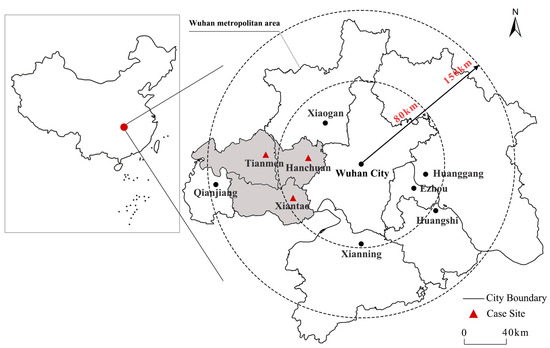

Therefore, we focus on these three county-level cities, namely, Hanchuan, Xiantao, and Tianmen, to examine their transitions from typical regions with large outflow populations to destinations of return migrants and further investigate the new mechanisms of county-level urbanisation. Specifically, our work mainly centres on the following four typical sites, namely, the ‘Hanchuan Economic and Technological Development Zone’ in Hanchuan City, ‘Tianmen High-Tech Industrial Park’ and ‘Yuekou Town’ in Tianmen City, and ‘Maozui Town’ in Xiantao City (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Case site.

3.2. Data and Method

This study is based on multiple rounds of field investigations carried out not only in Hanchuan, Xiantao, and Tianmen but also in Hanzheng Street in Wuhan and Kangle Village in Guangzhou from 2016 to 2021. Notably, the findings from the team’s early investigations in Wuhan and Guangzhou provide supports for elucidating the background and historical context of return migration. We conducted interviews with a total of 57 individuals in Hanchuan, Xiantao, and Tianmen. The interviewees consisted of 15 government officials, 11 returning entrepreneurs, six workshop owners, and 25 garment workers. We collected qualitative data through in-depth interviews, supplemented by government documents, statistical yearbooks, newspaper reports, and articles, to track the dynamics of return migration and its impact on the migrants’ homelands [58].

Specifically, we initiated a centralized discussion with the county government leaders of the three county-level cities and carried out in-depth interviews with representative staff from various departments, including the County Development and Reform Commission, the Natural Resources and Planning Bureau, the Economic and Information Technology Bureau, the Statistics Bureau, the Commerce Bureau, the Human Resources and Social Security Bureau, town governments, the Development Zone Management Committee, and other relevant governmental departments.

The results of the statistical analysis of our samples reveal significant differences in the characteristics of returning entrepreneurs and family workshop owners. Regarding returning entrepreneurs, they predominantly possessed extensive entrepreneurial experience prior to their return, with an average age of 48 years (ranging from 33 to 65 years). Nearly half of the returning entrepreneurs resided in Wuhan and regularly commuted from the study areas to Wuhan and vice versa. Furthermore, a significant portion of them had previously established shops or factories on Hanzheng Street in Wuhan. In contrast, the majority of family workshop owners were young individuals who typically lacked entrepreneurial experience prior to their return. On average, they were 35 years old, with ages ranging from 27 to 42 (maximum to minimum). A majority of the workshop owners returned to their hometowns after leaving Guangzhou. Regarding the garment workers, 80% had a great deal of experience in the garment industry, and they were mainly returning workers with significant expertise in garment production in large cities like Guangzhou, Hangzhou, and Shenzhen. The remaining 20% were handymen responsible for tasks such as buttoning and packing, primarily consisting of local labourers.

We approached returning entrepreneurs and workshop owners using snowball sampling and randomly interviewed garment workers in factories. In addition, a systematic analysis of government documents provided information on national and local policies and measures aimed at rural migrants.

4. Profiling Return Migration in Hubei Province

Return migration to Hubei Province is initially driven by institutional factors. In particular, Eastern China is dedicated to industrial transformation and upgrading, seeking to draw in high-tech industries while simultaneously phasing out traditional manufacturing or labour-intensive sectors. Meanwhile, the central region, propelled by ‘The Rise of Central China’ strategy, actively strives to attract return migrants for further development. We argue that RMEs are the key components of return migration in Central China and that they are driving the emergence of new industrial areas in county-level cities. Specifically, RMEs can be defined as migrants who return to their hometowns to establish industries and commerce, carry out production or services by means of their strengths or resources accumulated in the migration process [26]; however, in this study we focus more on the group engaged in clothing production and processing, constituting the main RMEs in the case area. In this study, RMEs mainly include entrepreneurs and family workshop owners; they are the earliest returnees and have significant advantages in terms of capital scale and labour resources. In contrast to entrepreneurs, by workshop owners we refer to those who lack entrepreneurial experience before returning and carry out small-scale, low-cost entrepreneurial activities after returning.

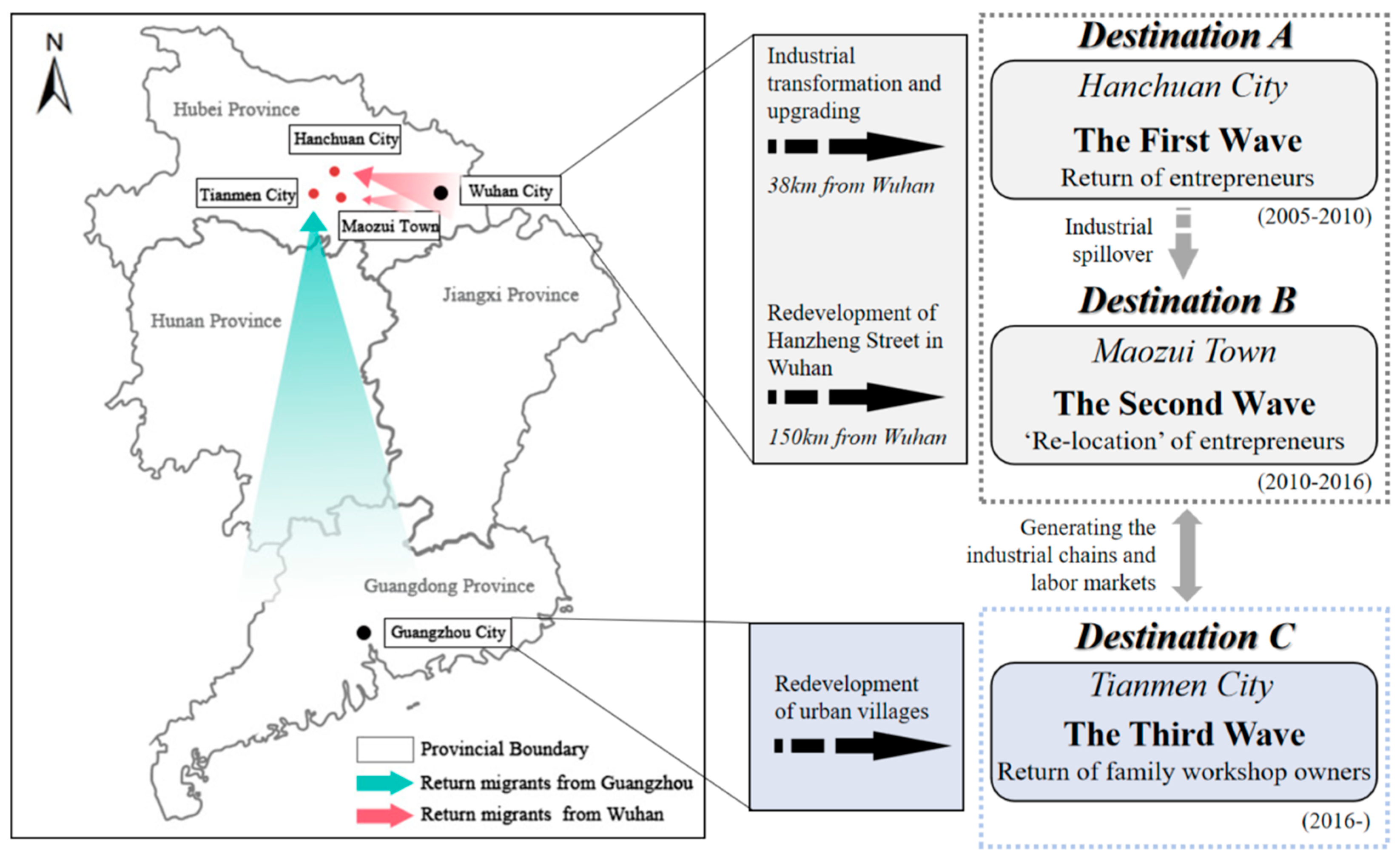

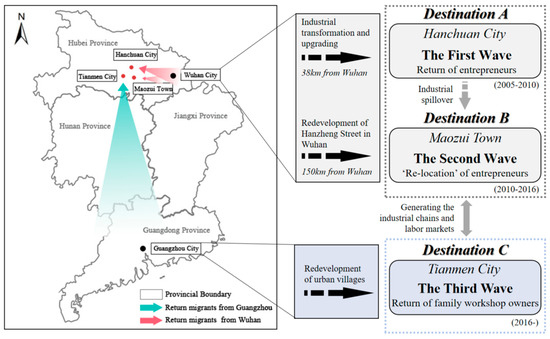

Therefore, this study focuses on the return processes of RMEs and their effects on county-level urbanisation. We found that the processes of return in the case area can be divided into three stages: a first wave, dominated by entrepreneurs in pursuit of economic efficiency; a second wave, characterised by the relocation of entrepreneurs to scale up their businesses; and a third wave, led by family workshop owners, consisting of setting up informal industries to reduce the cost of starting a business (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Return migration from Wuhan and Guangzhou.

4.1. First Wave: The Return of Entrepreneurs

Since 2005, against the background of Wuhan’s economic transformation, which was initiated to promote the relocation of traditional ‘low-end’ industries out of the main urban area of Wuhan while introducing a large number of high-tech industries around the new industrial zone, garment enterprises located on Hanzheng Street in Wuhan have been forced to move out. Hanchuan, which is approximately 38 km away from Wuhan, has become the first choice for returning entrepreneurs. On the one hand, the returning enterprises started to strategically relocate their production departments to Hanzheng Clothing Industry Park, situated in Hanchuan, while still keep their sales operations centred in Wuhan. This configuration establishes a cross-regional division of labour between Wuhan and Hanchuan, creating an integrated model for production and sales.

On the other hand, returning enterprises take advantage of labour resources and convenient infrastructure in Hanchuan, effectively reducing their production costs. Specifically, the Hanchuan Power Plant provides steam energy for returning enterprises, which is highly relevant to the garment industry and attracts the return of the remaining garment industry on Hanzheng Street. In the following years, more than 3000 garment enterprises and 80,000 migrant workers gathered in Hanchuan.

4.2. Second Wave: The ‘Relocation’ of Entrepreneurs

Around 2010, the textile and garment industries in Hanchuan developed vigorously under the impetus of returning migrants and industries. This period was characterised by a notable increase in the number of returning enterprises and the expansion of the production scale. Consequently, the available land space in industrial parks within Hanchuan City was constrained, accelerating the relocation of garment enterprises. The ongoing redevelopment of Hanzheng Street in Wuhan propelled the outward expansion of clothing enterprises from Hanzheng Street to the surrounding areas of Wuhan. Additionally, enterprises that returned to Hanchuan contemplated expanding their production scales, intensifying the demand for new industrial spaces.

In response, in Xiantao City, the local government of Maozui Town seized the opportunity to attract the garment population and industry, thus emerging as a new destination for return migration. Maozui, with its established clothing production base, was planned by Xiantao as a new industrial cluster, i.e., the Maozui Clothing Industrial Park. This park is expected to accommodate return migrants and enterprises. Since 2010, more than 240 enterprises have returned to Maozui. Diverging from the small workshops prevalent in the early years on Hanzheng Street in Wuhan, the majority of enterprises in Maozui now engage in the garment production on assembly lines.

4.3. Third Wave: The Return of Family Workshop Owners

Since 2016, along with its ‘High Quality Development’ strategies and the ‘Urban Renewal Action’, Guangzhou has taken extensive actions to reshape itself and its industries in recent years. This transformation involves the closure of ‘low-end’ garment factories and the redevelopment of urban villages in Guangzhou. As a result, many Tianmen clothing workers have been forced to leave Kangle Village and other places within Haizhu District of Guangzhou. Leveraging the knowledge, technology, and capital available, migrants established family workshops, capitalising on the burgeoning e-commerce industry that had emerged in the returning areas. The return migration and industries not only generated new industrial spaces, but also established a new market and industrial chain within the returning area. This has paved a way for the return and entrepreneurial activities of family workshop owners.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated return migration in Tianmen. From a global perspective, the lockdown policies implemented by the state to curb the virus’s spread have effectively restricted mobility; however, these policies have notably posed challenges for migrants, including increased unemployment, income shortages, and even discrimination issues, as migrants are often viewed as a source of infection [59]. In this vein, the pandemic has also disrupted internal migration in China. On one hand, interregional lockdown policies limit the mobility of migrants. On the other hand, the impacts of the pandemic on exports has severely reduced the job opportunities of rural migrants. Therefore, nearly 500 family workshops from Guangzhou have returned to Tianmen, mainly concentrating in the Changwan Community or Yuekou Town after the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Modalities of the Return-Migrant Urbanisation of Hubei Province

5.1. Industrial Agglomeration Driven by Market Forces

We argue that the investment spillover dominated by entrepreneurs from central cities, such as Wuhan, to surrounding areas serves as a pivotal force in county-level urbanisation. The relocation of enterprises to county-level cities primarily stems from entrepreneurs’ consideration of reducing production costs and strengthening industrial connections. Such urbanisation, promoted by entrepreneurs, has become a prominent feature of county-level urbanisation in Hanchuan.

The return of entrepreneurs from Wuhan is closely linked to the industrial restructuring of large cities. For a long time, practitioners engaged in garment industries from Xiantao, Hanchuan, and Xiaogan accumulated in Hanzheng Street in Wuhan, where the density of both the industry and population increased quickly in the 1990s. Accordingly, the available space for businesses has shrunk sharply. Constrained by such limitations, garment entrepreneurs have resorted to using rental houses or factories around Hanzheng Street, and some small-scale factories are as compact as 20 square metres, with a combination of living, production, and storage space, contributing to poor living conditions and severe security risks. In the 2000s, the local government of Wuhan promulgated an ‘industrial restructuring plan’ that encourages the growth of high-tech industries while phasing out low-end industries, such as the garment industry. Additionally, the government initiated a ‘comprehensive relocation and transformation plan’ for Hanzheng Street, facilitating the repositioning of the garment industry to surrounding counties. By leveraging its convenient location near Wuhan, Hanchuan has emerged as a carrier for accommodating returning industries and populations from Wuhan. In 2005, a handful of garment enterprises initially made the move from Hanzheng Street to Hanchuan and established the Hanzheng Garment Industry Park, only 35 km away from Hanzheng Street.

The industrial relocation is not a random process; it is closely linked to the industrial base, resources, and other factors in the receiving areas [60,61]. Our findings further reveal that the relatively low production cost in Hanchuan has become a key indicator of garment enterprises’ returns. Relocation to the Hanzheng Clothing Industry Park, in close proximity to the Hanchuan Power Plant, ensures a reliable power supply for returning enterprises. This offers stable and cost-effective steam energy for garment enterprises, significantly reducing operational costs because steam serves as the primary heat medium in the ironing process in clothing production. A government official of Hanchuan attributed Hanchuan’s success to its industrial relevance and locational advantages.

Many companies from Wuhan to Hanchuan are interested in the steam energy of our Hanchuan Power Plant, which is a comparative advantage of Hubei Province. The east side of Xinhe Town (where the Hanzheng Clothing Industry Park locates) in Hanchuan is next to the Dongxihu District of Wuhan, and the south is next to the Caidian District of Wuhan. It is because of its proximity to Wuhan that entrepreneurs are willing to move here.

Consequently, the Hanzheng Garment Industrial Park in Hanchuan has driven the development of many industrial projects, including factories, washing, dyeing facilities, and sewage treatment. In 2020, the Hanchuan Economic Development Zone, in which Hanzheng Garment Industry City is located, initiated its spatial expansion and adjustments. The original area of 438.94 hectares was expanded to 2243.69 hectares. This expansion will incorporate more than 20 local villages into the development zone, fostering growth in the surrounding rural areas. Furthermore, to sustain the ongoing return of the garment industry and population from Wuhan and coastal regions of China, the entrepreneurs who returned to Hanchuan have demonstrated foresight by initiating the construction of other industrial park projects, including Zheshang Industrial Park, Yuhua Industrial Park, and Central China Fur City, etc. Drawing inspiration from the successful experience of the Hanzheng Garment Industry Park, the development of other industrial parks has significantly expanded the scale of Hanchuan’s garment industry. The annual output value of enterprises above the designated size in Hanchuan’s garment industry increased from CNY 10.54 billion in 2010 to CNY 71.30 billion in 2021, accounting for 45.2% of the total output value of the whole city. Hanchuan has also been certified as one of the largest garment production and processing bases in China owing to its annual processing of more than 200 million garments, over 800 garment-supporting enterprises, and the large figure of employees (about 10,000 in 2022).

However, it has also been noted that enterprises returning to Hanchuan exhibit weak inter-enterprise connections, imposing certain limitations on industrial upgrading. Specifically, a significant portion of returning enterprises falls into the category of low-end businesses. Radically, these enterprises opt to relocate only their production departments, keeping intact the sales departments that heavily depend on the markets of the large cities. This strategy serves to lower production costs for the enterprises while sustaining their existing sales channels. Given the underdeveloped state of the local professional market in the return area, high-end talents within these enterprises, including designers and managers, tend to congregate in Wuhan.

5.2. Development Oriented by Local States

Local states are often recognised as the driving forces behind return migration and county-level urbanisation in China [62]. As the urban redevelopment of Hanzheng Street continued to implement, the local state of Maozui Town in Xiantao played a vital role in attracting the return of its garment industry and population. Specifically, the local state of Maozui viewed such a return as an opportunity to stimulate local economic growth. Approaches taken by the local state include the promulgation of various policies to attract both the garment industry and returning migrants.

Our investigation confirms that the local state of Maozui accommodates the second wave of the garment industry and population returning from both Wuhan and Hanchuan. On one hand, the redevelopment of Hanzheng Street continues to crowd out the garment industry. From August 2007 to February 2009, there were eight fire accidents on Hanzheng Street, where safety problems were prominent. Garment industries that did not meet the safety requirements were demanded to leave by the local government. On the other hand, the return of the garment industry to Maozui are also closely related to the saturation of industrial land in Hanchuan. In the first wave of returns, Hanchuan housed many spillover garment enterprises, though its industrial land was limited. In this context, the garment enterprises and population that initially settled in Hanchuan began to shift to more peripheral areas of the Wuhan metropolitan area, such as Maozui. Compared to Hanchuan, the newly built Maozui Garment Industrial Park could provide a larger amount of construction lands (Figure 3). Meanwhile, the local state of Xiantao also guided enterprises returning to Maozui by limiting the provision of industrial lands to other townships. Therefore, the local state of Maozui launched a series of strategies to encourage the entrepreneurs to move back to their hometowns.

Figure 3.

New factories built by the local government of Maozui Town.

The rapid development of the garment industry in Maozui can be attributed to the efforts of the local state for investment promotion, planning, and construction. The local state has made three significant contributions. First, the local state has energetically invested in transportation infrastructure, including highways and town roads, laying a solid foundation for the garment industry and new markets. Additionally, the local state has promulgated policies such as loan discounts, tax incentives, and recruitment assistance to encourage enterprises to return. Representatives of the local state ventured to Guangzhou to entice logistics parks to settle in Maozui, further fortifying the garment industry chain. Such logistics parks can effectively reduce the high transportation costs of garment enterprises, as they have long relied on the Hanzheng Street logistics market. Today, entrepreneurs can distribute goods nationwide from Maozui.

Second, the local state facilitated the concentration of original village residents in towns through adjustments in the allocation of urban and rural construction land. This process involved the construction of commodity houses or new rural communities, creating ample industrial space for returning enterprises. Consequently, standardised canteens, accommodation areas, and parking lots were constructed. Accordingly, after their return, the living conditions of the workers greatly improved, as the local state built standardised factories and dormitories equipped with separate showers and toilets, which could accommodate one to two people per unit.

Third, the local state adopted a collaborative approach using social capital to plan and build these factories jointly. Specifically, the local government would cover the costs of factory construction according to the needs of the returning enterprise. From 2010 to 2016, the area of Maozui expanded by approximately 2 square kilometres, and the long-term residents increased by approximately 25,000. In 2015, the urbanisation rate of Maozui exceeded 65%, which was higher than that of Xiantao (54.6%). A staff member of Xiantao’s Natural Resources and Planning Bureau praised the leaders of Maozui Town as follows:

Maozui is located at the junction of Tianmen, Xiantao and Qianjiang, and has been a transportation hub since ancient times, so its status in the towns of Xiantao is special, ranking relatively high. The cadres of Maozui are more energetic, of relatively high quality, and they are often more creative.

Consequently, the development of the garment industry in Maozui increased the income of the returning population. Against the background of the reform of the county-level hukou system, the education demand and consumption demand of the return migrants have also increased. Therefore, most of them buy commodity housing in Xiantao to settle their elderly family members or children, where high-quality service resources could be accessed. From 2010 to 2017, the real estate market in Xiantao experienced an explosive growth. Specifically, the investments in real estate development increased from CNY 480 million to CNY 3.59 billion. In 2017, the sales area of commodity housing in Xiantao reached 2.57 million square metres, with an average annual growth rate of 46.8% and a sales volume of CNY 10.27 billion, an average annual growth rate of 54.5%. The director of one of the garment factories in Maozui said:

We didn’t buy a house in Xiantao for investment, because buying a house has nothing to do with living there. It is for the convenience of our children’s education, so that they can receive a good education.

However, there are also some drawbacks regarding the development of Maozui, notably the challenges of extensive land use. Maozui’s local state failed to anticipate the subsequent significant influx of the returning population and enterprises, leading to the provision of extensive land resources to these enterprises at the early stages. Specifically, Maozui’ local state attracted the return of its population and businesses by actively providing industrial land and constructing standardised, spacious factories, leading to an inefficient utilisation of land resources. Our survey indicates that in 2021, the annual output value per acre in the Maozui Garment Industrial Park was approximately CNY 2.56 million, which is significantly lower than the figure of CNY 4.57 million in the Hanchuan Zheshang Industrial Park located in Hanchuan. Moreover, the enterprises in Maozui occupy a larger land area compared to the garment workshops on either Hanzheng Street or in the urban villages of Guangzhou. Consequently, Maozui today is facing a shortage of industrial land.

5.3. Informality Driven by Individuals or Families

Some scholars believe that informal businesses effectively reduce the cost of starting a business while increasing the income of low-capital groups [63]. Our research indicates that, under the guidance of individual or family entrepreneurship, low-capital migrants who returned from Datang Village and Kangle Village in Guangzhou gathered in the suburbs of Tianmen to set up family workshops. We also claim that the trend of the migrant population returning to their hometowns to establish family workshops is a response to the industrial restructuring of major cities.

Tianmen’s urbanisation exhibits two characteristics, the informality of space production and sectoral management. First, the owners employed a strategy of setting up family workshops in their own farmhouses or rented rural dwellings to cope with the constraints of formal industrial parks, such as higher rent and the requirements of the scale of production. This approach is cost-effective as the rental fees for workshops are significantly lower than those for industrial parks. Accordingly, the functions of farmhouses are gradually being diversified; that is, the initial residential function is gradually shifting to a combination of storage, clothing production, and other functions. In the survey, we noticed that a typical family workshop in the Changwan Community, located in the suburb of Tianmen, was a self-built house with an area of about 100 square metres and with a total of four floors. The first floor is a combination of fabric storage and packaging areas; the second and third floors are clothing production areas for cutting, sewing, and ironing; and the fourth floor is often a staff dormitory (Figure 4). According to the data released by the City Media Centre of Tianmen, the comprehensive cost of garment workshops is approximately 50% lower than that in Guangzhou because the cost to rent such a space can reach CNY 35 per square metre in Guangzhou, while it is only CNY 7–8 in the suburban and rural areas of Tianmen.

Figure 4.

Workshop agglomerations in Tianmen, Hubei Province.

In terms of informal sectoral management, owing to the lack of formal business licences and tax registration certificates, family workshop owners are not restricted by laws and regulations, and their management is informal. However, the informal or flexible management system of family workshops is in line with the demands of return migrants who must take care of their families. The evidences from Tianmen show that the causes of return migration are mainly affected by family factors, such as caring for elderly family members or raising children. Compared with formal garment factories, working in family workshops is more convenient with respect to workers picking up their children from schools or taking elderly members to medical service facilities. Furthermore, the informal organisation of family workshops is generally based on stable social networks; thus, there is a high cohesion among family workshops. For example, one family workshop in the Changwan Community is run by the family members: the parents are responsible for the cleaning and diet of the workshop, the workshop owner’s sister is in charge of production supervision, and the workshop owner himself is responsible for receiving orders and arranging the tasks. Additionally, the workers employed in family workshops are mostly former colleagues, relatives, and neighbours who are closely linked.

Owing to the informality of workshops, which are characterised by small-scale and diverse types of production orders, the owners flexibly allocate the distribution of labour within the workshop or temporarily recruit workers/part-timers in response to order needs. In this vein, a workshop can offer low-skilled jobs, such as packaging, to elderly labourers and low-skilled labourers, who serve as part-time workers. Consequently, these informal employment systems have promoted the growth of the non-agricultural employment. A family workshop owner in the Changwan Community said:

When I was rushing the goods, the people in the community were also helping. I didn’t stipulate how long they have to work, as there were not so many rules. They (workers) all have their own things to deal with on weekdays, they come to help me when they are free. For example, they will help me pack and deliver goods, which is a part-time job.

Additionally, we found that family workshop owners capitalised on the new opportunities ushered in by e-commerce to cultivate informal industries. Compared to garment enterprises with relatively fixed production and sales systems, family workshops with flexible production and management systems often resort to e-commerce. Many ‘online shop’ operators have accumulated extensive experience in e-commerce operations while working in Wuhan, Guangzhou, and other large cities, thus have gained insights into e-commerce market through their social networks. Specifically, these ‘online shops’ flexibly organised clothing production, such as trading orders, fabrics, garment workers, and warehouses, which have become key driving forces leading to the agglomeration of various family workshops. The impact of the e-commerce platforms on family workshop owners has been articulated by the director of the Tianmen High-tech Industrial Park:

After the development of this e-commerce platform like Taobao or Pinduoduo, it has changed the garment industry. The income of many large-scale factories is decreasing, while the small family workshops which didn’t receive orders in the beginning are now able to operate their own e-commerce platforms and sell clothes online.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

In the earlier 21st century, the scale of return migration have intensified in China. We argue that the conventional push–pull model is undergoing a reversal; that is, the dual dynamic of the industrial upgrading of developed areas and the revitalisation of less-developed areas is collectively giving rise to the rise of return migration. In this study, we found that the number of return migrants has grown and that they have played a vital role in promoting the development of Central China such as the counties of Hubei Province. Prior literature in the Chinese context has mainly centred on the diverse urbanisation models in coastal areas, including the ‘Sunan model’, ‘Wenzhou model’, and ‘Zhujiang model’, by employing multiple macroeconomic factors to determine the mechanisms of rapid urbanisation [13,15,16]. However, few studies have investigated new urbanisation patterns in Central and Western China, where there has been a large amount of return migration and new industrial clusters. Second, although international migration studies have shed light on the impact of return migration on the migrants’ homelands, they tend to emphasise that successful returnees with greater education and capital accumulation often have a positive impact on their homelands, while the so-called failed returnees are recognised as being useless to their homelands, weakening the effects of the local state, households, and individuals [20].

Therefore, through multiple rounds of surveys involving a total of 57 individuals conducted in three county-level cities around Wuhan, China, we explored the diverse logic of county urbanisation in Central China, placing particular emphasis on local governance, emerging markets, households, and individual perspectives. This effort has contributed to the development of a novel framework for understanding county-level urbanisation. We have also contributed to filling the gap in the study of other countries by considering political and institutional factors that may trigger new opportunities for different types of return migration. As indicated in our study, the reasons for the return of RMEs are closely related to some local policies in Wuhan and Guangzhou, which aim to eliminate so-called low-end manufacturing, as well as the efforts of local states in Central China, such as those regarding building highways, logistics, and pro-growth policies.

This study aims to depict the characteristics and dynamics of RMEs and further examine their impacts on county-level urbanisation. The findings indicate that RMEs constitute the primary force in return migration, encompassing two categories: entrepreneurs and family workshop owners. We contend that the former are typically entrepreneurs, serving as the initial group that triggers the flow amid macroeconomic structural changes, subsequently influencing the return of family workshop owners and migrant workers. Concerning family workshop owners, a significant proportion of this group comprises young individuals with entrepreneurship and e-commerce skills. The evidence suggests that RMEs are emerging as a pivotal driver of county urbanisation in Central China. Their return brings back capital, technology, and e-commerce business strategies.

It has also been observed that return migration has had a profound impact on advancing county urbanisation in Hubei Province, leading to diverse modalities of new-types of urbanisation: industrialisation in Hanchuan, township urbanisation in Maozui, and informality in Tianmen, which played a vital role in promoting local economic and industrial development. Specifically, most entrepreneurs relocate the production departments of their enterprises to the industrial clusters in Hanchuan, thereby making notable contributions to economic growth at the county level. Second, the local state of Maozui employed a range of measures, including investment attraction, land transfer, and factory construction, to actively attract return migrants. These initiatives aim to elevate the industrial growth of Maozui Town. Third, family workshop owners who gained entrepreneurial skills set up informal workshops in towns or villages around industrial parks in Tianmen, taking advantage of social networks and emerging online businesses such as pinduoduo. We argue that such family workshops play an important role in boosting regional development and improving the garment industry chain by means of social networks or kinships. However, certain negative aspects, such as weak inter-business and non-intensive land use, also impose constraints on the sustainable development of urbanisation in returning areas (to some extent).

We have found that return migration, seen as a rational response to macroeconomic structural changes, has become a significant driver for promoting the social and economic development of migrants’ homelands. Building upon our research, we assert that the precise assessment by local governments of the trends and characteristics of return migration, coupled with the efficient allocation of resources such as land and public service facilities, can maximize the impact of the migrants’ return on county urbanisation. Therefore, we propose the following policy recommendations: First, we call for conducting comprehensive research in other counties in the central and western regions to comprehend the dynamics of return migration. This will enable accurate predictions regarding future returnees. Second, we recommend a calibrated supply of industrial land and public service resources in county spatial planning. This approach ensures the alignment of resources with the evolving needs of returning enterprises. Moreover, we recommend that the local governments try to revitalize existing spaces within townships, such as vacant factories or old markets, to accommodate returning enterprises, particularly small-scale family workshops. Also there is a need to enhance infrastructure support for these industrial clusters, encompassing roads, logistics, gas, fire, and other facilities. This initiative is designed to facilitate the transition of the family workshop industry to practices involving formalisation, clustering, and adherence with high-quality standards. Third, we suggest the establishment of a specialized clothing market, accompanied by the construction of a supporting exhibition centre. This initiative constitutes a potent measure aimed at attracting leading enterprises and high-end talents. Finally, we recommend that local governments adopt participatory governance. By involving returning entrepreneurs in the process of local spatial planning, construction, and implementation, the sense of belonging, attachment, and satisfaction among return migrants can be enhanced.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: L.Y. and Z.L.; Methodology: L.Y. and D.L.; Formal analysis: L.Y., Z.L., and D.L.; Investigation: L.Y. and D.L.; Resources: Z.L.; Data curation, L.Y. and D.L.; Writing (original draft preparation and review and editing): L.Y. and Z.L.; Visualisation: L.Y.; Supervision: Z.L.; Project administration: Z.L. and D.L.; Funding acquisition: Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 42171203).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments that improved this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Hukou system refers to the household registration system that categorizes the Chinese population into rural and urban segments, serving as a mechanism to regulate rural-urban migration in pre-reform China. Individuals with rural hukou find it challenging to convert to an urban status, whereas those with urban hukou are entitled to the associated urban welfare benefits. |

| 2 | COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, is a global health crisis that began in late 2019. The virus was first identified in Wuhan, China, and quickly spread worldwide, significantly impacting the social and economic fabric of countries across the globe. On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization declared it a pandemic. |

References

- Démurger, S.; Xu, H. Return migrants: The rise of new entrepreneurs in rural China. World Dev. 2011, 39, 1847–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croitoru, A.; Vlase, I. Stepwise migration: What drives the relocation of migrants upon return. Popul. Space Place 2022, 28, e2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z. Returned migrants, family capital and entrepreneurship in rural China. China Popul. Dev. Stud. 2017, 1, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, K. Return migration in China: A case study of Zhumadian in Henan province. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2017, 58, 114–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korinek, K.; Entwisle, B.; Jampaklay, A. Through thick and thin: Layers of social ties and urban settlement among Thai migrants. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2005, 70, 779–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floating Population Family Planning Service and Manage Division of National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Report of China’s Migrant Population Development; China Population Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Tabulation on the 2020 Population Census of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/d7c/ (accessed on 26 November 2021).

- Department of Human Resources and Social Security of Hubei Province. Notice on the in-Depth Implementation of the Action Plan for Returning Home to Start a Business. Available online: http://rst.hubei.gov.cn/zfxxgk/zc/gfxwj/202112/t20211230_3941692.shtml (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Liu, C.W. Return migration, online entrepreneurship and gender performance in the Chinese ‘Taobao families’. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2020, 61, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. Changing urbanization processes and in situ rural-urban transformation: Reflections on China’s settlement definitions. In New Forms of Urbanization; Champion, T., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004; ISBN 9781315248073. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. China’s Urban Transition; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.D.; Lin, J.; Zhang, L. E-commerce, taobao villages and regional development in China. Geogr. Rev. 2020, 110, 380–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Wei, Y.D.; Chen, W. Economic transition, industrial location and corporate networks: Remaking the Sunan Model in Wuxi City, China. Habitat Int. 2014, 42, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.H.D. Network linkages and local embeddedness of foreign ventures in China: The case of Suzhou municipality. Reg. Stud. 2015, 49, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.D.; Li, W.; Wang, C. Restructuring industrial districts, scaling up regional development: A study of the Wenzhou model, China. Econ. Geogr. 2007, 83, 421–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. The geopolitics of cross-boundary governance in the Greater Pearl River Delta, China: A case study of the proposed Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macao Bridge. Political Geogr. 2006, 25, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Fu, Q.; Gu, J.; Shi, Z. Does migration pay off? Returnees, family background, and self-employment in rural China. China Rev. Interdiscip. J. Greater China 2018, 18, 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- King, R. Migration comes of age. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2015, 38, 2366–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibreab, G. Citizenship rights and repatriation of Refugees. Int. Migr. Rev. 2003, 37, 24–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.W.; Fan, C.C. Success or failure: Selectivity and reasons of return migration in Sichuan and Anhui, China. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2006, 38, 939–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R. How Migrant Labor Is Changing Rural China; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Causes and consequences of return migration: Recent evidence from China. J. Comp. Econ. 2002, 30, 376–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottinger, R. Return Migration and Rural Industrial Employment: A Navajo case study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrldnder, U. The ‘human resource’ problem in Europe: Migrant labor in the FRG. In Ethnic Resurgence in Modern Democratic States; Raaman, U., Ed.; Pergamon: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Wahba, J.; Zenou, Y. Out of sight, out of mind: Migration, entrepreneurship and social capital. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2012, 42, 890–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dustmann, C.; Kirchkamp, O. The optimal migration duration and activity choice after re-migration. J. Dev. Econ. 2002, 67, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmelch, G. Return migration. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1980, 9, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wu, F.; Liang, Q.; Li, Z.; Guo, Y. From hometown to the host city? Migrants’ identity transition in urban China. Cities 2022, 122, 103567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wu, F.; Moore, S.; Li, Z. Migrants’ willingness to contact local residents in China. Cities 2023, 133, 104120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, Z. Where your heart belongs to shapes how you feel about yourself: Migration, social comparison and subjective well-being in China. Popul. Space Place 2020, 26, e2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lados, G.; Hegedus, G. Return migration and identity change: A Hungarian case study. Reg. Stat. 2019, 9, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Xiang, B. Native place, migration and the emergence of peasant enclaves in Beijing. China Q. 1998, 155, 546–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Hu, F.Z.; Jeong, J. Towards inclusive urban development? New knowledge/creative economy and wage inequality in major Chinese cities. Cities 2020, 105, 102385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, J. Selection, selection, selection: The impact of return migration. J. Popul. Econ. 2015, 28, 535–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azose, J.J.; Raftery, A.E. Estimation of emigration, return migration, and transit migration between all pairs of countries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019, 116, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S. Return migration in the United States. Int. Migr. Rev. 1974, 8, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderkamp, J. Return migration: Its significance and behavior. Econ. Inq. 1972, 10, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, R.E. Foreign labor and German industrial capitalism 1871–1978: The evolution of a migratory system. Am. Ethn. 1978, 5, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainer, A. Rural development and migration in Mexico. Dev. Pract. 2013, 23, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, A.; Robinson, C. Global labour markets, return, and onward migration. Can. J. Econ. Rev. Can. D Econ. 2008, 41, 1285–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetta, F. Return migration and the survival of entrepreneurial activities in Egypt. World Dev. 2012, 40, 1999–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paine, S. Exporting Workers: The Turkish Case; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Junge, V.; Revilla, J.D.; Schätzl, L. Determinants and consequences of internal return migration in Thailand and Vietnam. World Dev. 2015, 71, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Radu, D. Return migration: The experience of Eastern Europe. Int. Migr. 2012, 50, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piracha, M.; Vadean, F. Return migration and occupational choice: Evidence from Albania. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1141–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilahi, N. Return migration and occupational change. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2002, 3, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesnard, A. Temporary migration and capital market imperfections. Oxf. Econ. Pap. New Ser. 2004, 56, 242–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul, M.K.; Fredericks, L.J. The new economics of labour migration (NELM): Econometric analysis of remittances from Italy to rural Bangladesh based on kinship relation. Int. J. Migr. Res. Dev. 2015, 1, 156276588. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:156276588 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, W.W.; Lin, L.; Shen, J.; Ren, Q. Return migration and in situ urbanization of migrant sending areas: Insights from a survey of seven provinces in China. Cities 2021, 115, 103242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.H.D.; Liefner, I.; Miao, C.H. Network configurations and R&D activities of the ICT industry in Suzhou municipality, China. Geoforum 2011, 42, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Li, Z.; Ma, Z. Changing patterns of the floating population in China, 2000–2010. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2014, 40, 695–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. In situ urbanization in China: Processes, contributing factors, and policy implications. China Popul. Dev. Stud. 2017, 1, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Jin, L.; Chen, L. Reurbanisation in my hometown? Effect of return migration on migrants’ urban settlement intention. Popul. Space Place 2021, 27, e2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z. Urban labour-force experience as a determinant of rural occupation change: Evidence from recent urban-rural return migration in China. Environ. Plan. A 2001, 33, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W. China’s Mobile Economy: Opportunities in the Largest and Fastest Information Consumption Boom; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Yin, X.; Zheng, X.; Li, W. Lose to win: Entrepreneurship of returned migrants in China. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2017, 58, 341–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H. Growth of rural migrant enclaves in Guangzhou, China: Agency, everyday practice and social mobility. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 3086–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axinn, W.G.; Pearce, L.D. Mixed Method Data Collection Strategies; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, A.A.; Nawaz, F.; Chattoraj, D. Locked up under lockdown: The COVID-19 pandemic and the migrant population. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2021, 3, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boschma, R. Towards an evolutionary perspective on regional resilience. Reg. Stud. 2015, 49, 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, R. Regional resilience: A promising concept to explain differences in regional economic adaptability? Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Planning centrality, market instruments: Governing Chinese urban transformation under state entrepreneurialism. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1383–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Huang, G. Informality and the state’s ambivalence in the regulation of street vending in transforming Guangzhou, China. Geoforum 2015, 62, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).