Abstract

Despite the ongoing discrimination that hinders women’s full participation in urban life, the International Agenda 2030 and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) emphasize the eradication of violence against women and underscore the need for regulatory measures, local governance, and equitable practices for sustainable urban development focusing on women’s needs. The women-inclusive cities related (WICR) studies, which have been gaining academic attention since the late 1990s, remain broadly explored yet lack a holistic trajectory and trend study and a precise women-inclusive city concept framework. This study applies bibliometric analysis with R-package Bibliometrix version 3.3.2 and a systematic review of 1144 articles, mapping global trends and providing a framework for women-inclusive city concepts. The findings show that WICR research increased significantly from 1998 to 2022, indicating continuous interest. Gender, women, and politics are the top three most frequent keywords. Emerging research directions are expected to focus on politics, violence, and urban governance. The findings also indicate a clear tendency for researchers from the same geographical backgrounds or regions to co-author papers, suggesting further international collaboration. Although no explicit definitions were found in the articles used, the prevailing literature consistently suggests that a “woman-inclusive city” ensures full rights, equal consideration of needs, and the active participation of women in all aspects of urban life.

1. Introduction

While cities theoretically provide equal opportunities for all, fostering a diverse and economically rewarding life [1], urban structures have mainly been male-centric, often overlooking the female experience. Despite constituting half of the global population, women have historically faced discrimination and inequality in areas such as mobility, urban utilities, economic opportunities, and politics [2,3,4]. International commitments play a crucial role in advancing women’s rights and inclusivity in urban spaces. Agenda 2030’s SDG #5 mandates gender equality and women’s empowerment, recognizing their significance for sustainable development. It also calls for the eradication of all forms of violence against women and highlights the importance of regulatory action and local governance. SDG #11 aims to ensure access to safe, inclusive, and green public spaces for all, particularly women, children, the elderly, and people with disabilities. It emphasizes women’s active participation in urban planning and local government decision making [5], underscoring the need for a more equitable approach to the achievement of sustainable urban development.

The concept of an inclusive city emerged in the late 1990s and has gained prominence in academic discourse over the past few years. Prominent international organizations have prioritized this idea since 2002 [6]. An inclusive city, derived from the concepts of inequality and exclusion, is generally defined as a city that promotes development while emphasizing fairness of access. UN-Habitat describes an inclusive city as one where individuals of all backgrounds can access the urban areas’ social, economic, and political opportunities [7,8]. Liang et al. [9] identify five dimensions of an inclusive city: spatial, social, economic, environmental, and political, which provide a comprehensive framework for understanding and implementing the concept of an inclusive city.

To date, some related concepts have been introduced worldwide, such as feminist cities, women-friendly cities, and women-inclusive cities. Any of these concepts are generally acceptable and applicable to describe a women-inclusive city since they share a common goal, which is to promote access, representation, and equity, particularly for women in urban environments. Women-friendly cities emerged as a response to conventional urban planning practices. Initiated by the UN in 2006, the Women-Friendly Cities Program strives to create urban spaces that promote women’s active participation in decision making and ensure equal access to services [10]. Seoul pioneered this initiative in 2007, focusing on enhancing women’s well-being [11]. Another influential concept is the Feminist City, which critiques the patriarchal and capitalist influences on architecture and urban planning that disadvantage women. It proposes a new urban framework that considers communal resources, housing, public spaces, transportation, safety, sustainability, and architectural design from a feminist perspective [12,13]. Finally, we discussed the idea of women-inclusive cities, a subset of the broader gender-inclusive city idea. This concept ensures equal access to urban services and opportunities for all, regardless of gender, and addresses urban socioeconomic disparities [7]. It also considers the rights of marginalized or previously excluded groups in urban policy and planning [14,15]. Vienna is a notable example of a city pioneering gender-inclusive urban planning [16]. While the concept of an “inclusive city” has been explored in various contexts, its specific application to women remains under-researched. Prior studies have examined women’s perceptions and gender differences in urban experiences [17,18,19]. They have also looked at women’s participation and the gender gap in politics [10,20,21], the economy [22,23], and technology [24,25,26]. However, no single study explicitly defined the concept of “women-inclusive cities”. Considering the significant global inequalities women face and the built environment’s profound impact on daily life and social interactions, it is crucial for urban planning and design to strive for greater equity. This includes creating women-inclusive cities. The existing gap in the literature underscores the need for further research to understand and articulate this concept better.

Recent studies have shown that women and girls worldwide suffer safety concerns while accessing public facilities [27,28], encounter significant hurdles in achieving gender equality in the workforce [29], and experience a noticeable leadership gap [30]. The persistent gender inequities that women encounter in urban settings prompt immediate corrective action to establish more inclusive cities for women. While valuable research exists on how urban environments affect women’s access to opportunities such as economic prospects, safety, mobility, public services, infrastructure, housing and land ownership, decision making, and leadership, this information is currently dispersed across multiple sources. Our study’s significance stems from its capacity to collect and synthesize the scattered information of “Women-Inclusive Cities Related” (WICR) studies into a centralized reservoir. This reservoir makes critical information accessible for urban planners, legislators, and other stakeholders working on women-inclusive cities. This reservoir catalyzes worldwide programs promoting gender equality (SDG 5), inclusive cities (SDG 11, New Urban Agenda), and women’s fundamental “right to the city”. It aligns with and strengthens intersectional approaches to urban equity by amplifying and prioritizing women’s perspectives and demands. The centralized knowledge hub provides a comprehensive picture of the current state of WICR studies, identifies gaps and areas for further investigation, lays a solid foundation, and directs future research efforts. It also has the potential to accelerate real progress in achieving SDGs. Additionally, critical findings extracted from the reservoir serve as cumulative evidence, assisting decision makers in clarifying what constitutes a women-inclusive city and translating academic insight into best practices and practical recommendations to inform future gender-responsive urban policies and initiatives.

This study employs a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches. The bibliometric analysis, conducted using the “R-package Bibliometrix”, [31] examines the global research trajectories and trends of WICR studies. The systematic review is used to define the “Women-Inclusive Cities”. The dataset comprises WICR keywords retrieved from the Web of Science Core Collection spanning 1998 to 2022. Bibliometric analysis, a quantitative method, tracks a field’s evolution, identifies research gaps, and establishes cooperative ties between academic institutions or nations [32,33]. Recognized as an efficient approach for studying research patterns within a specific field over time [34], it uses statistical computation to objectively compare scientific research across different countries, institutions, journals, and authors. It also traces research trajectories and emerging fields of inquiry, providing objective insights into a particular research field’s scientific output [35]. While bibliometric analyses are commonly employed in urban women studies [36,37,38], their use specifically in WICR studies is yet to be found. Accordingly, this study aims to:

- Identify the leading journals and authors in WICR studies.

- Identify the leading research articles and co-citations in WICR studies.

- Map the changing trends in WICR studies.

- Map the collaboration pattern in WICR studies.

- Define a “women-inclusive city” term from the existing literature.

By meeting these objectives, we hope to provide a comprehensive understanding of WICR research’s evolution over the past two decades, aiding academics and practitioners in this field’s framework. The review paper begins with an introduction, discusses data gathering and processing techniques, presents the findings, summarizes the study, discusses the limitations, and suggests future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

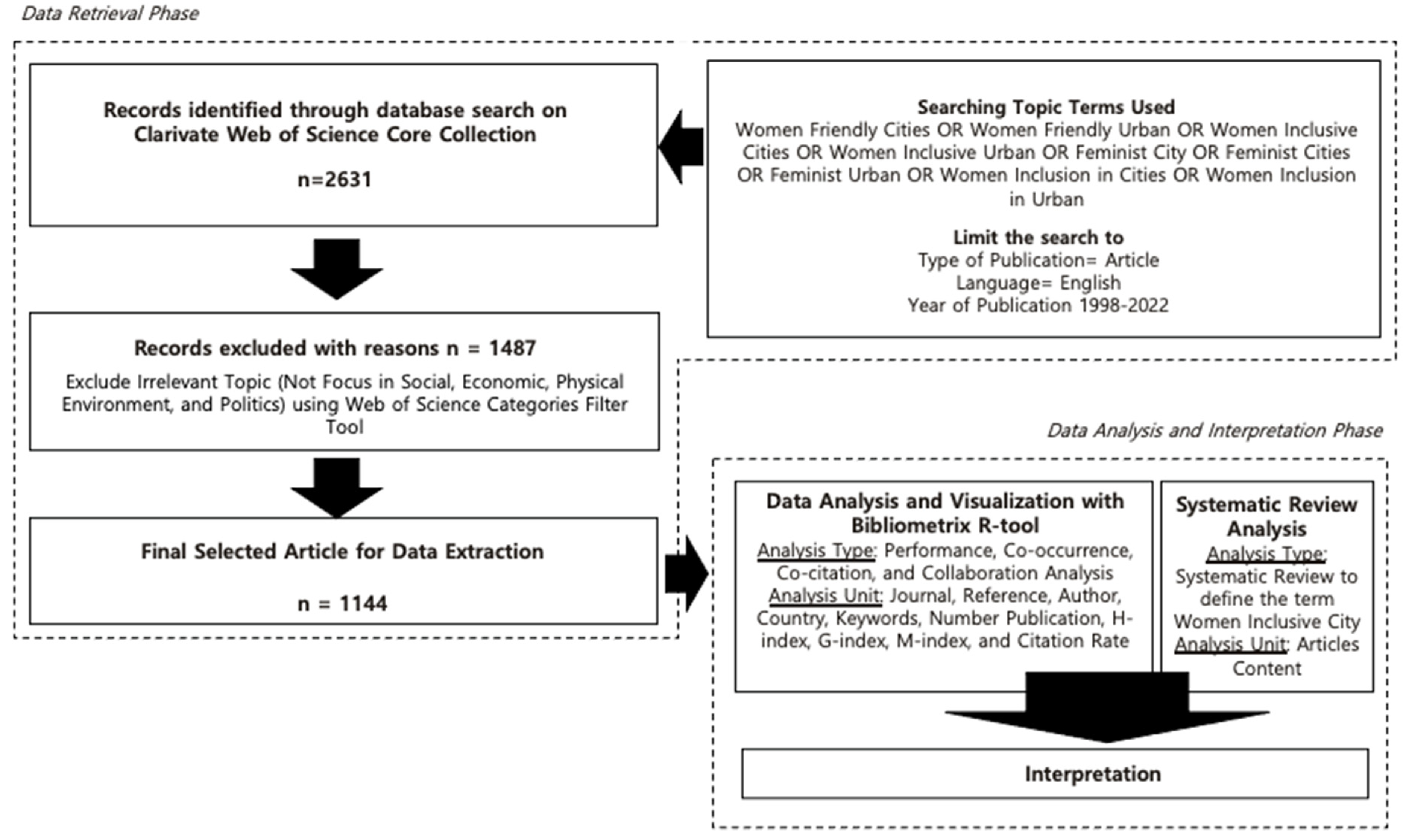

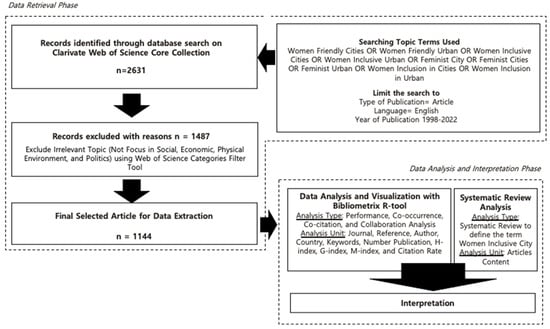

Clarivate’s Web of Science Core Collection (WoSCC) was used as this review paper’s data source. Recognized as a leading bibliographic database, WoSCC is widely accepted for various academic purposes [39,40] and is compatible with the selected bibliometric mapping software for result visualization, making it a reliable choice [31,39]. Only items with one of the following terms found in the article topic were included in the analysis: “Women Inclusive Cities”, “Women Inclusive Urban”, “Women Friendly Cities” “Women Friendly Urban”, “Feminist Cities”, “Feminist Urban”, “Women Inclusion in Cities”, and “Women Inclusion in Urban”. These terms, commonly referred to Women-Inclusive Cities Related (WICR), share a common goal despite their differences. The selection of these keywords was guided by the research objective, and only English articles were reviewed. The PRISMA screening process was applied in this study (see Figure 1). Initially, 2631 articles were discovered; however, to focus our search, we narrowed down the interdisciplinary term of WICR by refining the article categories related to urban planning, architecture, transportation geographical studies, social and behavioral science, economic science, political science, and environmental science with a particular emphasis on the dimension of the inclusive city, as described by Liang et al. [9]. This refinement, emphasizing the dimension of the inclusive city, resulted in a final inventory of 1144 articles for study analysis using the R-tool “Bibliometrix”.

Figure 1.

The scheme of review process. The data retrieval phase adapts the PRISMA flow diagram of the search strategy for the bibliometric analysis of WICR studies.

This study examines the research fronts in the WICR fields, essential articles, authors, journals, references, and nations participating in this field of study and their relationships using bibliometric analysis. Bibliometrix offers a systematic analysis of large bodies of information, identifying trends over time, research themes, changes in disciplinary boundaries, and the most productive scholars and institutions [31]. Our study incorporates descriptive analysis, scientific mapping, and systematic review approaches. Bibliometric science mapping allows for the comprehensive examination and visualization of literature review collections [39]. Bibliographic coupling, co-citation, co-word, and collaboration are the four main tiers of classification in bibliometric mapping analysis [33,41]. This research utilized the Bibliometrix R-package for bibliometric analysis, an open-source software package that is compatible with other statistical programs in the R language environment [31]. Figure 1 depicts the complete scheme of the data and methodology used in this study.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Leading Journals and Authors in WICR Studies

Our findings indicate that between 1998 and 2022, 1144 articles were published across 481 journal sources, with an annual publication growth rate of 12.32%, involving 2110 authors in total with an average of two co-authors per document, 3449 keywords, 58,275 references, and 14.03 average citations per document, as determined by Bibliometrix. The inaugural publication on WICR appeared in Urban Geography Journal in 1998, titled “Gender, Class, and Urban Space: Public and Private Space in Contemporary Urban Landscapes”. This study explores gender and urban space, using Edinburgh as a case study. Bondi’s [42] work on public–private area divisions in Edinburgh demonstrates how gender and class influence public and private situations. Subsequently, an additional 1143 articles were published through to the end of 2022. With 195 articles published, 2022 has become the most productive year. The most recent article, authored by Vijayakumar [43], “Labors of Love: Sex, Work, and Good Mothering in The Globalizing City”, highlights sex work’s role as a good mother, providing social and economic resources and enabling cisgender women to attain respectable femininity, challenging patriarchal ideals of masculine protection and upward mobility.

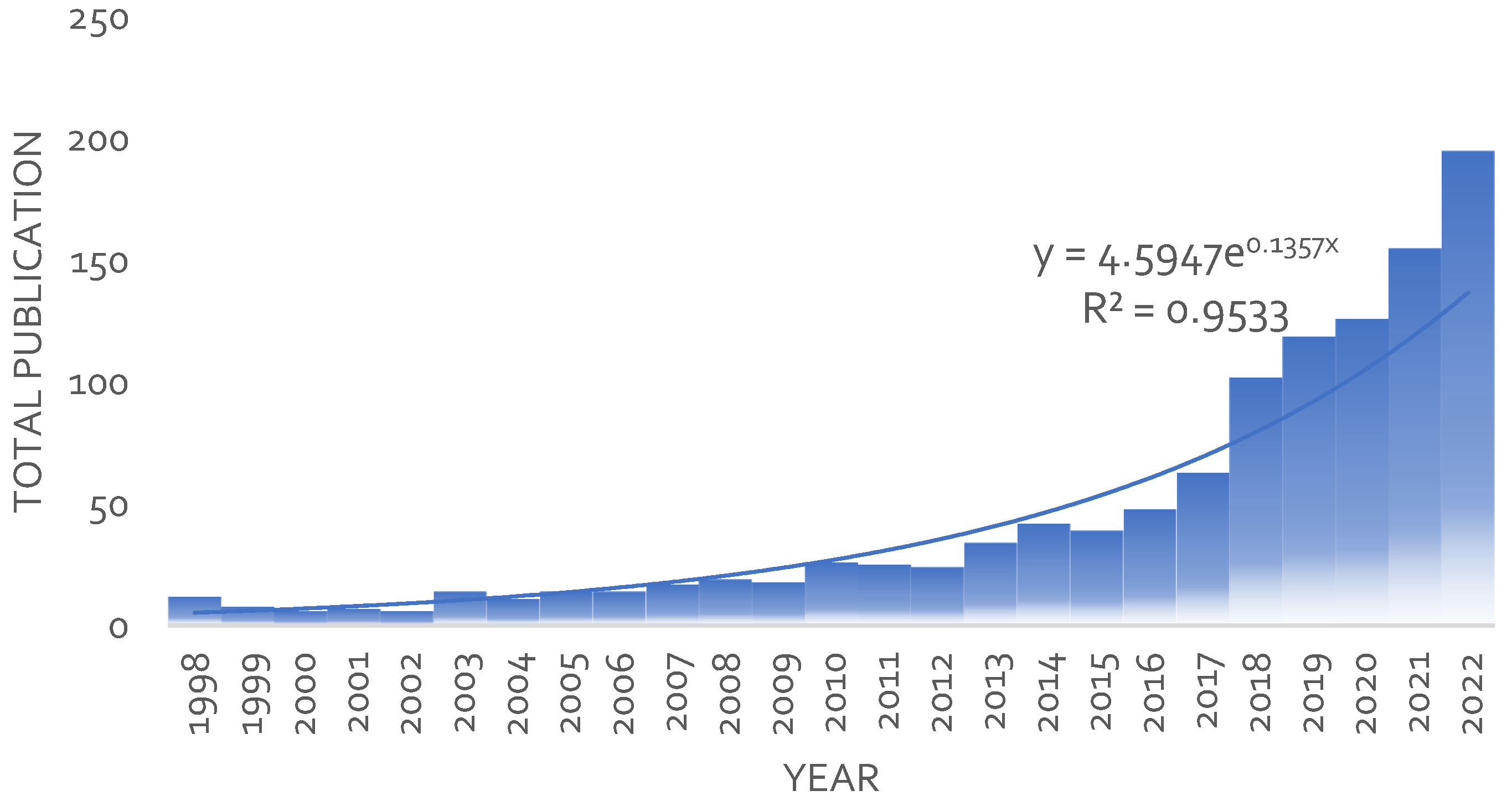

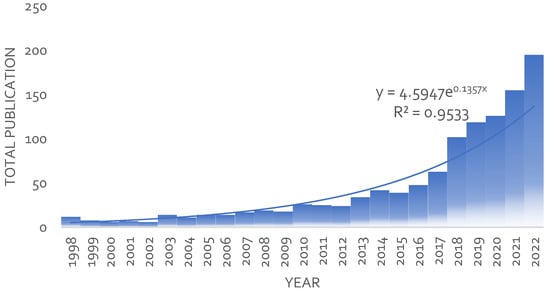

The findings reflect that even since The United Nations Millennium Declaration set the goal for addressing gender equality in September 2000, and UN Women published the practical guide for building safe and inclusive cities for women in 2011, the annual number of publications on WICR has not been significant. However, after the 2017 Women’s March took place in the United States, sounding a protest against Trump’s misogynistic policies that threatened women’s rights, scholars worldwide began to focus more on women’s rights and power dynamics in the cities, and the total publications each year in related subjects increased significantly. Figure 2 provides empirical support for the changing trends in publication patterns observed throughout the study period. Notably, the initial WICR studies publication was low, but it grew gradually after that. This graphical representation helps with the projection of an estimated quantity of upcoming articles by leveraging previous patterns.

Figure 2.

WICR studies publication growth trend 1998–2022.

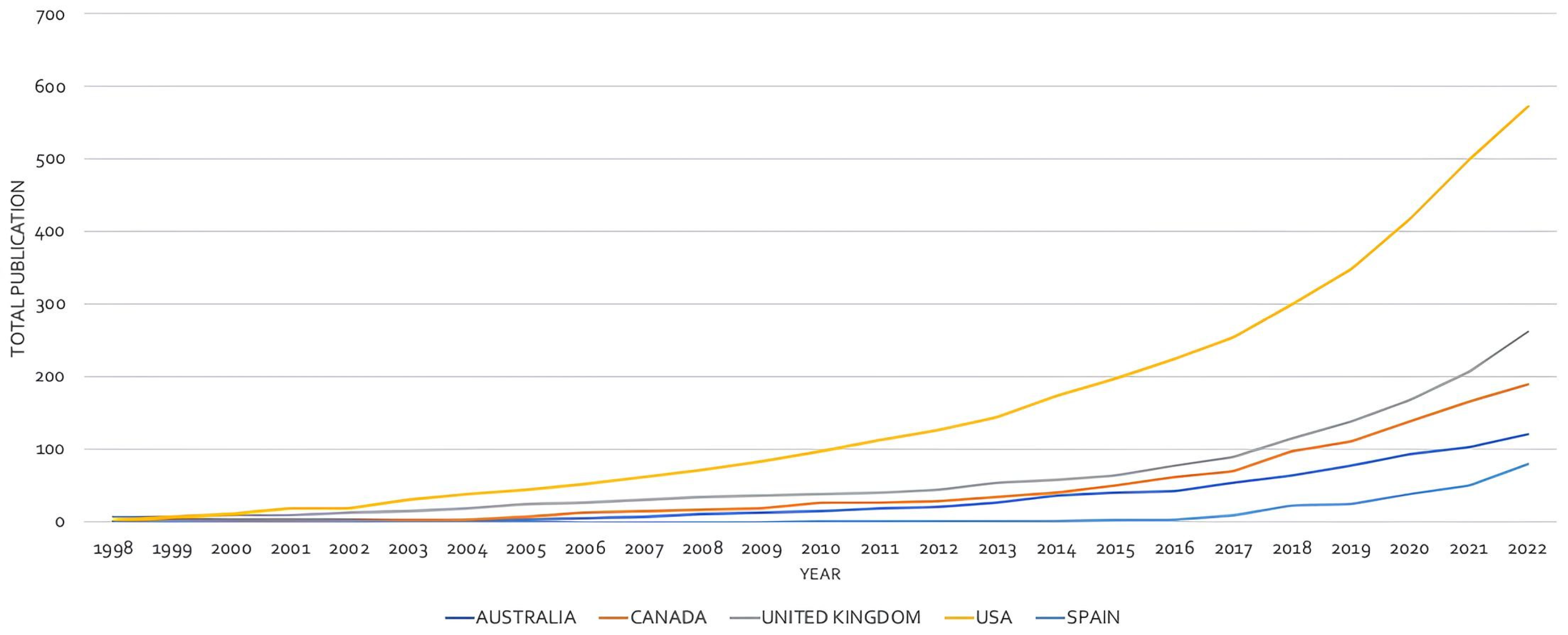

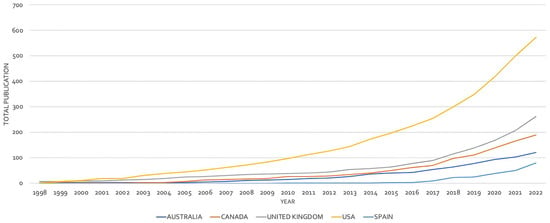

Identifying significant sources, authors, institutions, and countries is critical for researchers to collaborate effectively with other research groups at various levels. Table 1 and Table 2 and Figure 3 show key scientific groups that can be used to identify notable sources, authors, and countries in WICR studies. Table 1 presents the 25 most impactful journals. This study lists each journal’s H-index, G-index, M-index, total citations, number of articles published, and the year of first publication. The findings reveal that the journals Gender, Place, and Culture (GPC), Antipode, and Plos One have significantly influenced women-inclusive city studies due to their high H-index, with GPC leading in publication frequency by issuing 89 papers since 2005. Table 2 highlights the authors with the highest H-index, including Prof. Wright [44], whose pivotal work “A Manifesto Against Femicide” examines gender and class in Ciudad Juárez, and Prof. Fenster [45], who explores urban gender dynamics in “The Right To The Gendered City”. Prof. Parker B.’s [46] research on economic factors in female crime also stands out.

Table 1.

The most notable sources of WICR studies based on H-index *.

Table 2.

The most notable authors of WICR studies *.

Figure 3.

The most productive countries of WICR studies generated from Bibliometrix.

Penn State University and the University of North Carolina lead in publications, reflecting a broader trend of such research predominantly emanating from developed countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and Spain (Figure 3). This pattern underscores the rising focus on gender-inclusive urban planning in affluent nations, supported by the World Economic Forum’s findings that North America has made significant strides in closing its gender gap and has made the most progress globally [30]. However, South Asian countries lag in contributions to women-inclusive city research, underscoring a global disparity and the need for broader engagement.

3.2. Leading Articles and Co-Citation in WICR Studies

Our finding indicates the diversity of the research categories among the top 100 most-cited publications over the past three years. It reveals that 44% of these papers, spanning areas such as mobility, active transportation, economic opportunities, ecology, climate justice, and digital technology, suggest a strong preference for empirical studies. Theoretical conception is next at 21%, emphasizing the need to generate new theories and frameworks to increase understanding in various domains. Survey and ethnographic research, accounting for 18%, continue to be prevalent among scholars. Review studies account for 9%, emphasizing the importance of synthesizing current research to provide thorough overviews and identify gaps. Policy studies and experimental research are the least represented at 3% and 4%, respectively, demonstrating their importance for future research but also their low number of references compared to other research categories.

For bibliometric analysis, we utilized the Bibliometrix-R Package to identify the most cited works globally and locally. Cobo et al. [47] and Beliaeva [48] describe “Global Citation (GC)” as the total number of citations a document receives from all publications indexed in databases like Scopus, WOS, or Google Scholar. “Local Citation (LC)” denotes the citation count from within a specific, highly specialized set of publications under review. This differentiation in citation analysis aids in recognizing a document’s genuine impact, highlighting foundational and interdisciplinary research within the field [49]. Our study introduces crucial insights that are absent from prior literature reviews and bibliometric analyses. Table 3 lists the twenty-five most globally cited papers in WICR studies, with empirical research constituting half of these articles and the remainder spanning theoretical, review, and policy research. The most cited work is “Rethinking Water Insecurity, Inequality, and Infrastructure Through an Embodied Urban Political Ecology” by Truelove [50]; it contributes to urban political ecology by examining less explored aspects of water inequality. Following closely, Doan’s [51] study uses autoethnography to explore transgender individuals’ experiences of gender oppression in both public and private spaces. Till’s [52] work, ranking third, advocates for the understanding of inhabitants’ lived experiences to drive ethical and sustainable urban transformations.

Table 3.

The most influential globally cited articles of WICR studies *.

Further examination of the most locally cited WICR articles reveals a focus on more recent publications (Table 4). Fenster’s [45] study on “The Right To The Gendered City” has garnered significant attention, emphasizing the necessity of scrutinizing patriarchal power to mitigate its long-term negative impacts on diverse individuals’ access to urban areas. Following this, Truelove [50] and Beebeejaun [64] address gender, urban space, and the rights to the city, underscoring the critical role of gender considerations in urban planning for creating inclusive urban environments. The leading global and local citations collectively stress the importance of addressing gender inequality towards achieving sustainable and equitable urban futures, highlighting the urgent need for broader urban inclusion.

Table 4.

The most influential locally cited articles of WICR studies *.

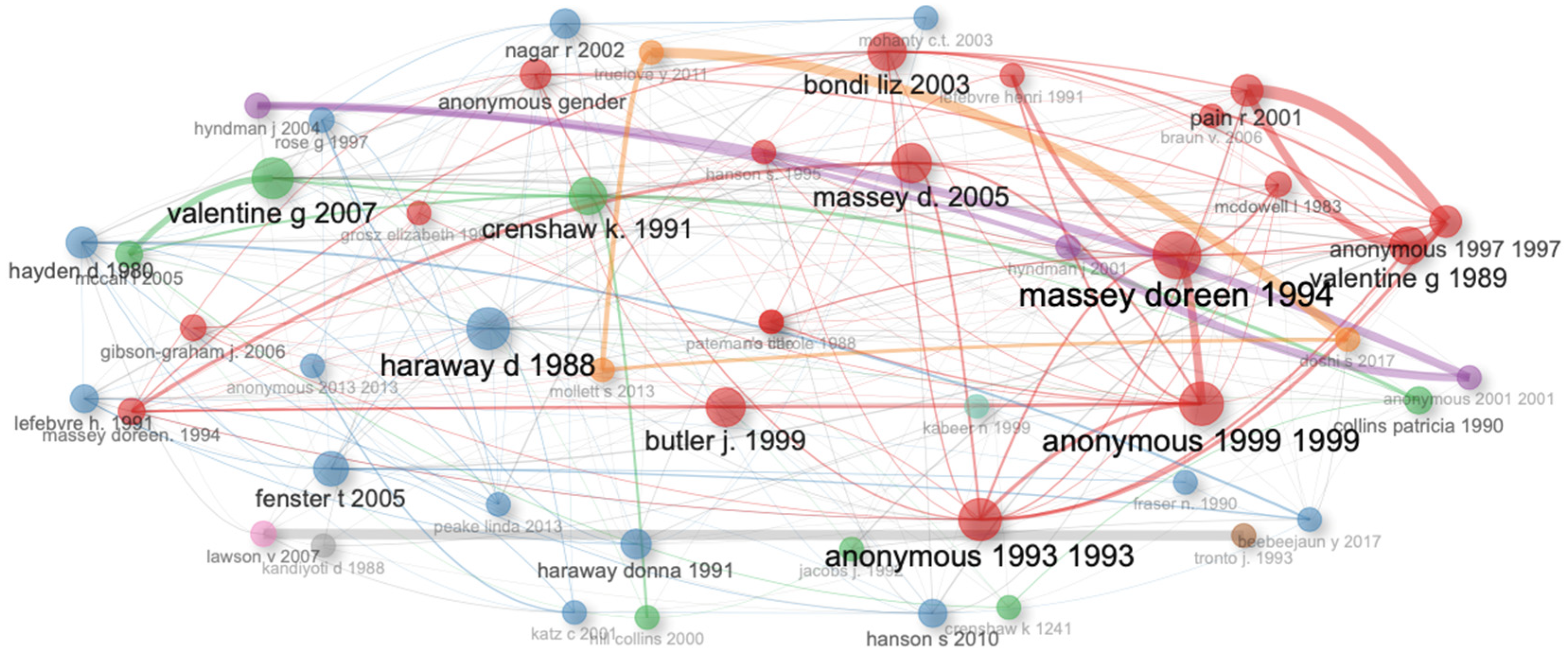

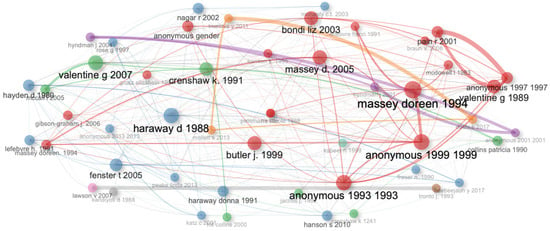

Meanwhile, co-citation analysis evaluates scientific articles, journals, and authors based on how often other researchers cite them. It complements the traditional publication metrics, such as impact factors, h-index, and publication count, and may indicate the research field’s intellectual structure and evolution [91]. A co-citation network is established if two documents are cited in the same document. Research clusters may emerge when multiple authors co-cite the same pairings of papers, and the co-cited papers within these clusters may share a common theme. Figure 4 depicts a co-citation network map of the 50 most cited articles, which are categorized into nine clusters based on the Walktrap algorithm. At the same time, Table 5 provides a comprehensive list of the most effective references associated with each cluster and the detailed key content of each reference.

Figure 4.

The co-citation network analysis of the 50 most cited articles of the total of 1144 articles generated from Bibliometrix. Each node represents an individual paper, the edges connecting them indicate co-citation relationships, implying that the related works are cited together in other academic papers, and the various colors represent clusters based on the Walktrap algorithm.

Table 5.

Most effective references in WICR studies field by co-citation analysis of documents *.

3.3. Changing Trends in WICR Studies

3.3.1. Popular Themes in WICR Studies

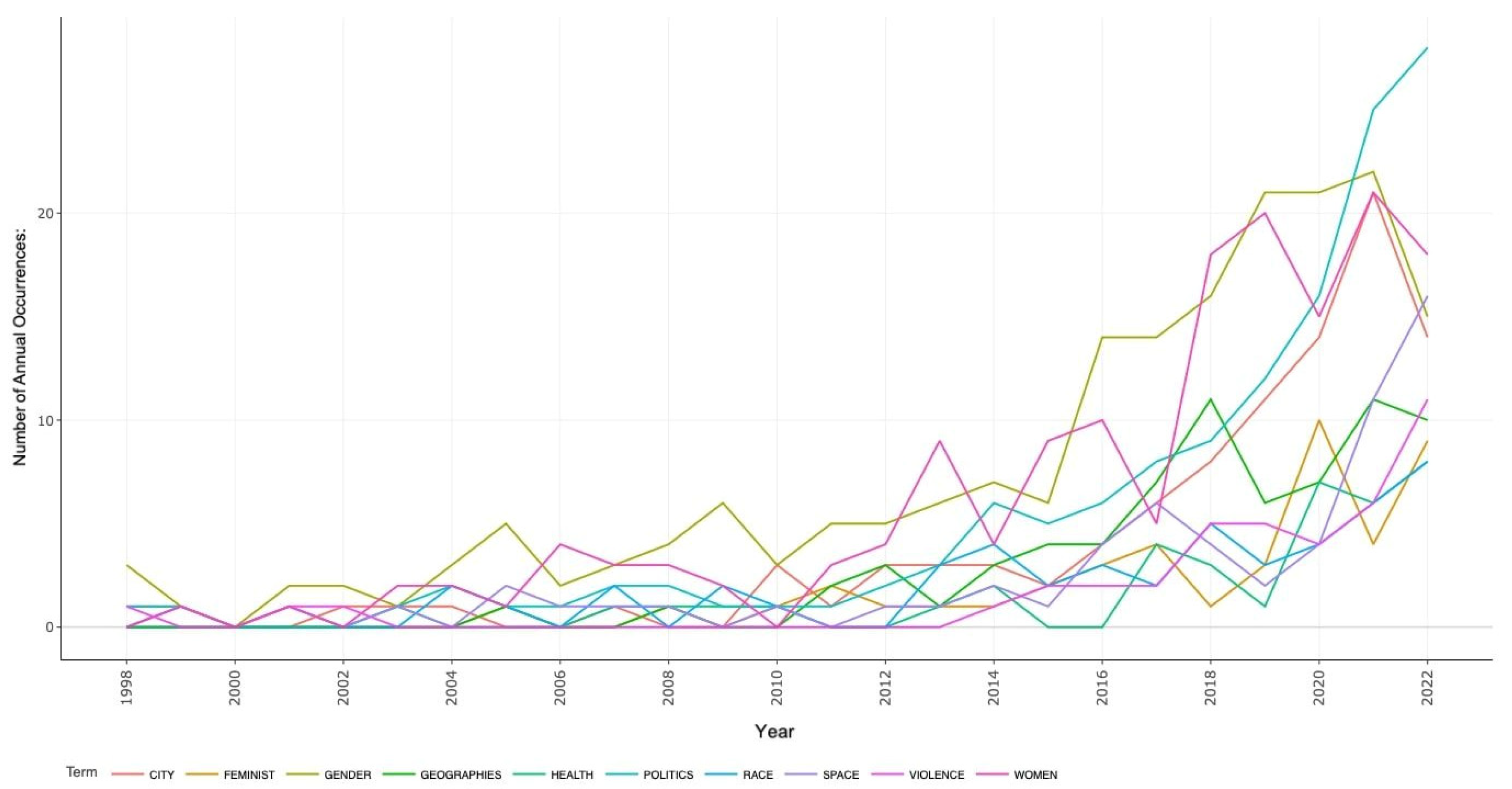

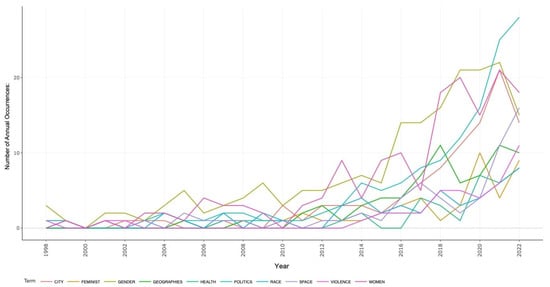

The study utilizes a clustering algorithm and regularization for co-occurrence network analysis of the top 10 KeyWords Plus, which comprises terms found in references but not in their corresponding titles, to identify the growth trend in WICR studies. The KeyWords Plus algorithm in Clarivate databases enhances cited-reference searches by identifying articles with common citations across different fields. Figure 5 illustrates the significant influence of the temporal dimension, as it reveals that gender, women, and politics consistently ranked as the top three keywords across various periods. One interesting observation is the significant rise in “gender”, “women”, “politics”, and “city” occurrences, particularly after 2015. This spike corresponds with all United Nations members adopting the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in 2015. The increased emphasis on gender equality (SDG 5) and inclusive cities (SDG 11, New Urban Agenda) have contributed to the observed trends as organizations and governments ramp up their efforts to fulfill the SDGs globally. Additionally, the terms “politics”, “space”, and “violence” appeared to grow positively over time, while the rise was not significant; however, they may be considered as emerging research directions.

Figure 5.

Growth trend of the top 10 KeyWords Plus generated from Bibliometrix.

3.3.2. Thematic Evolution in WICR Studies

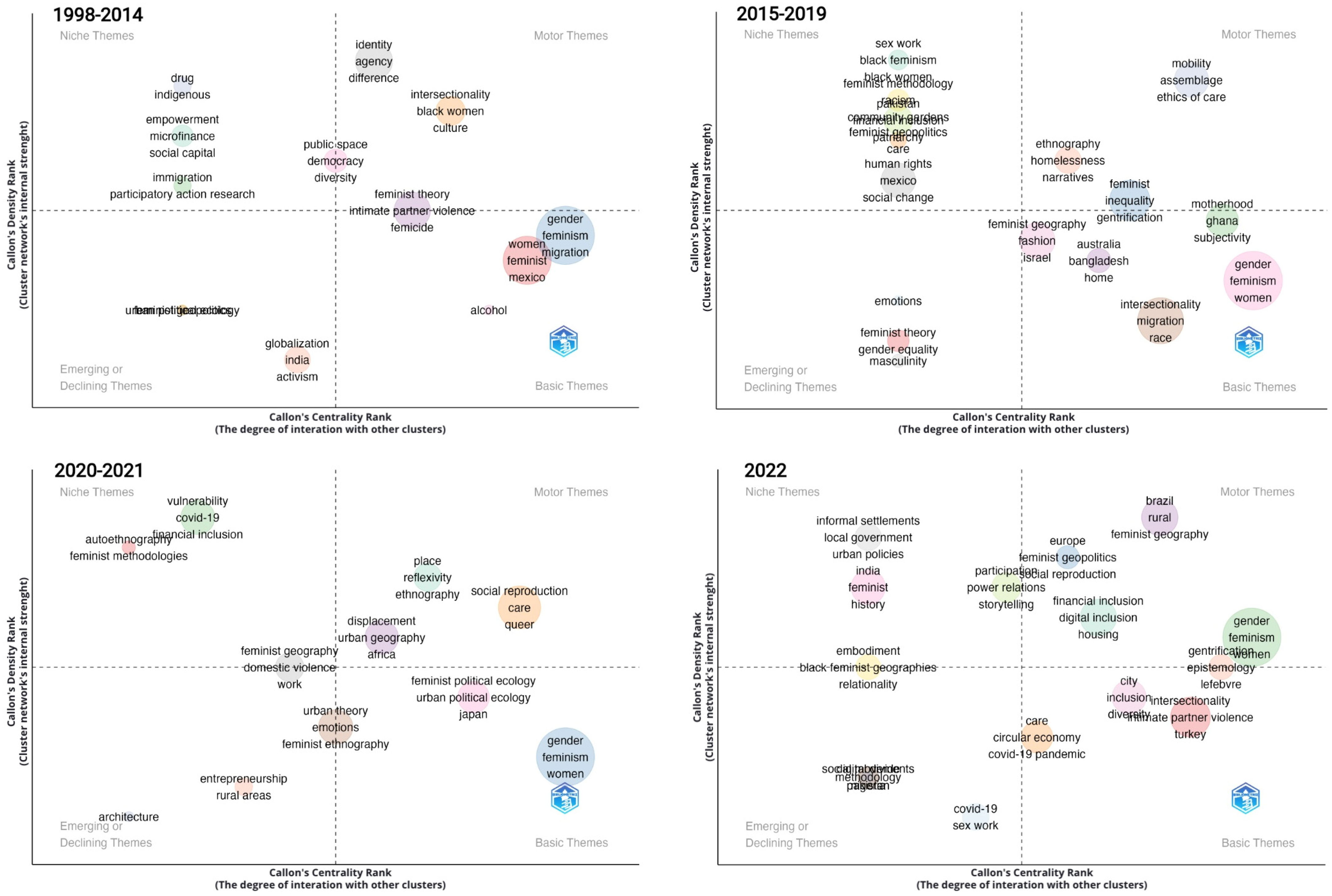

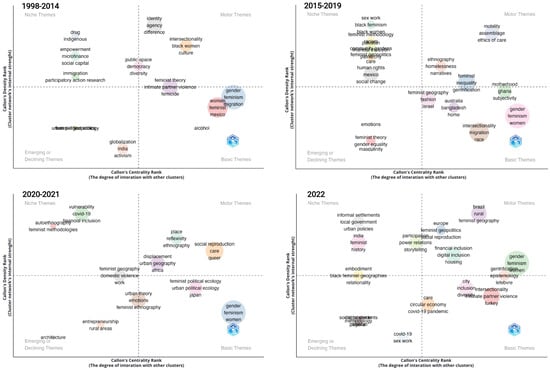

The analysis employs two distinct measures: Callon centrality, indicating research field significance, and Callon density, measuring theme development [108]. Thematic evolution maps are divided into four quadrants, with the motor topics in the upper-right quadrant considered to be well developed and relevant. The core concepts in the lower-right quadrant are deemed significant but underdeveloped; the emerging or declining themes are seen as poorly or marginally developed; and the niche themes are rapidly developed. Figure 6 depicts thematic evolution across four periods from 1998 to 2022.

Figure 6.

Thematic evolution map illustrates the author’s keyword co-occurrence network clusters throughout four periods generated from Bibliometrix. Callon’s centrality and density rank display co-occurrence network clusters as bubbles. Keyword occurrences in the cluster determine the bubble size. The X-axis depicts centrality (the degree of interaction of a network cluster in contrast to other clusters) and also indicates the significance of a theme. The Y-axis represents density (the internal strength of a cluster network), which can measure the theme’s development [109].

In the early 20th century, the global feminist movement advocated for equal opportunities in politics, work, family responsibility, and sexuality. During the initial period (1998–2014), scholars favored clustered themes such as “identity-agency-difference”, “intersectionality-black women-culture”, and “public space-democracy-diversity”. In the second period (2015–2019), WICR studies broadened to include subjects like “mobility-assemblage-ethics of care” and “ethnography-homeliness-narratives”. Social reproduction and ethics of care remained central until the final period (2022), while the focus shifted to “place-reflexivity-ethnography” and “displacement-urban geography-Africa” in the third period (2020–2021). In 2022, inclusivity-related themes like “financial-digital-housing inclusion” emerged as fully developed. Future research may delve into niche themes such as “informal settlement”, “local government”, “policies”, “participation”, “feminist theory”, and “power relations”.

The findings reveal shifting interests in WICR discussions and research over time. Despite feminist progress, women still encounter urban disadvantages compared to men. Scholars stress the urgency of promoting urban inclusivity and accelerating gender equality for a sustainable, resilient, and inclusive future. The field’s future appears promising as scholars expand the thematic scope of WICR studies over 20 years.

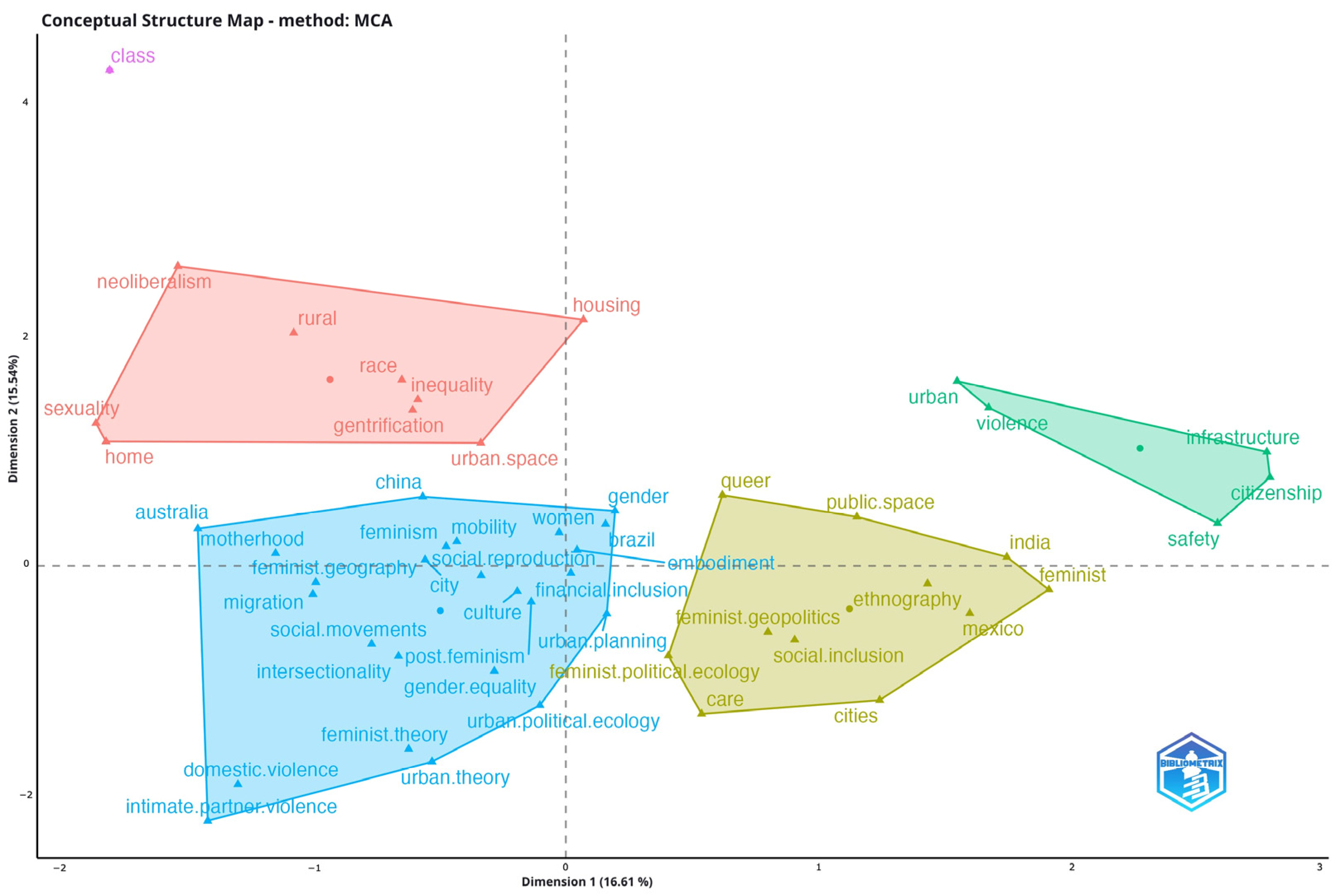

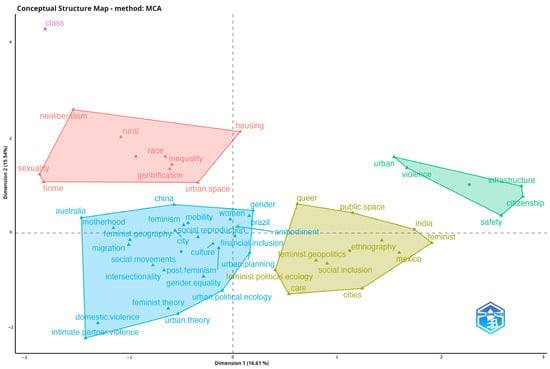

Using the Bibliometrix R-package, we employed multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) to visualize the relationships between the top 50 author keywords in the WICR research and K-means clustering to identify groups of similar concepts, thereby improving keyword homogeneity within the map [31]. This method, commonly used for clustering alongside MCA, displays keywords in a two-dimensional plot, emphasizing relevant keywords and their associations and developing research trends [110]. Figure 7 depicts the resulting map, which uses the x-axis (16.61%) and the y-axis (15.54%) to reflect the proportion of total variation explained by each dimension. These percentages are derived using the eigenvalues associated with each dimension. In MCA, the eigenvalues represent the variation explained by each dimension [111]. The first dimension explains 16.61% of the variation, associated with feminist geopolitics and geography, while the second dimension explains 15.54%, associated with urban space and equal opportunities for women. Additionally, the conceptual structure map also offered fresh insights, categorizing the most frequently used keywords into five clusters, each highlighted in different colors indicating the main thematic areas of the WICR research: feminist perspectives in urban settings, socio-spatial and politico-ecological inclusion, urban violence and safety, housing, and terms related to race, sexuality, and class.

Figure 7.

Conceptual structure map of the top 50 author keywords using the MCA method generated from Bibliometrix. The two dimensions retained from the MCA explain 32.15% of the total variance. Keywords are represented as points in a low-dimensional Euclidean space, where the proximity of points indicates the similarity in their usage across the dataset. K-means clustering creates 5 color-coded clusters.

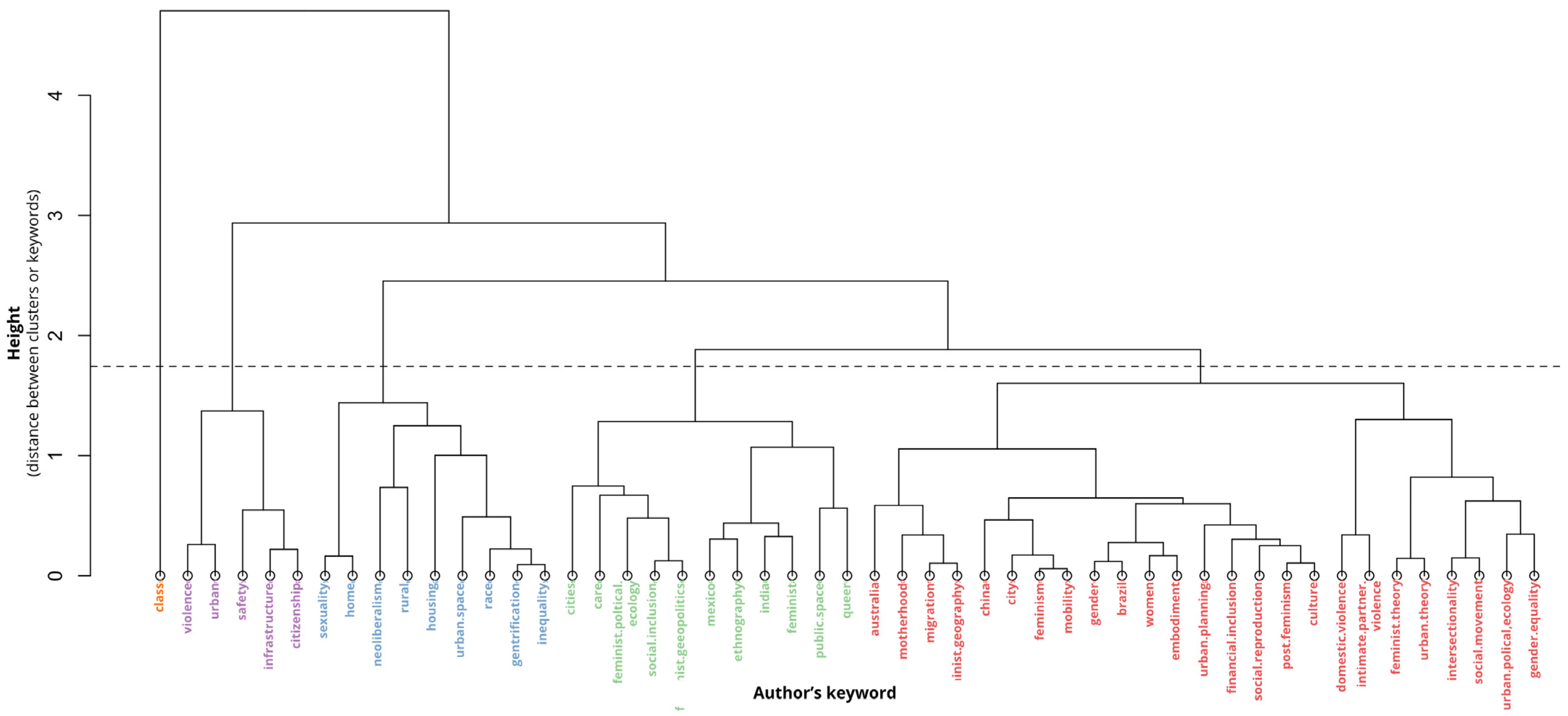

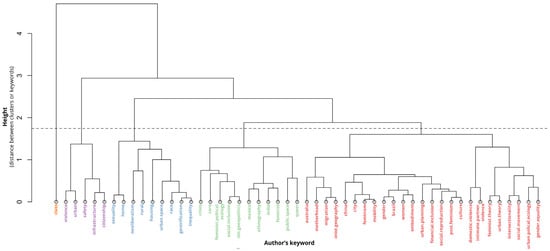

Using the same dataset, the MCA method is used to generate a dendrogram that illustrates the hierarchical relationships among objects based on their similarities or dissimilarities. Figure 8 illustrates a dendrogram of correlation criteria among keywords in a hierarchical framework. The keywords were classified according to their similarity using hierarchical clustering. The y-axis “Height” represents the distance between the cluster and the keywords. The chi-square distance is a common metric used in MCA. The height of each branch denotes the degree of dissimilarity between keywords or clusters: more dissimilar keywords or clusters are displayed higher, while more similar ones appear lower. The relationships between distinct keywords can be understood by observing the height and placement of the connecting lines. The two themes at the bottom of the dendrogram, “gentrification” and “equality”, for instance, are highly similar and are thus linked by a short connecting line at a relatively low height. In the presented dendrogram, the dashed line is drawn at a height of 2. This line sets a merging threshold to count clusters. Clipping the dendrogram at a height of 2 can determine the number of clusters. In this case, approximately five clusters form and are coded in different colors. Clusters that merge at a height of around 1.5 are highly similar. In contrast, those merging at higher heights are less similar. This helps determine the optimal cluster size and theme hierarchy. The resulting map reveals five distinct clusters displayed in different colors. The primary cluster, highlighted in orange, addresses fundamental issues such as motherhood, migration, feminist geography, mobility, gender, embodiment, and urban planning. Other clusters intersecting at similar heights signify their significant impact and the evolving themes in WICR studies.

Figure 8.

Dendrogram of the top 50 author keywords using MCA method generated from Bibliometrix. The x-axis indicates the data points being clustered, which are the author keywords, color-coded by cluster, while the y-axis reflects the distance at which clusters or keywords are merged during hierarchical clustering.

3.4. The Collaboration Pattern in WICR Studies

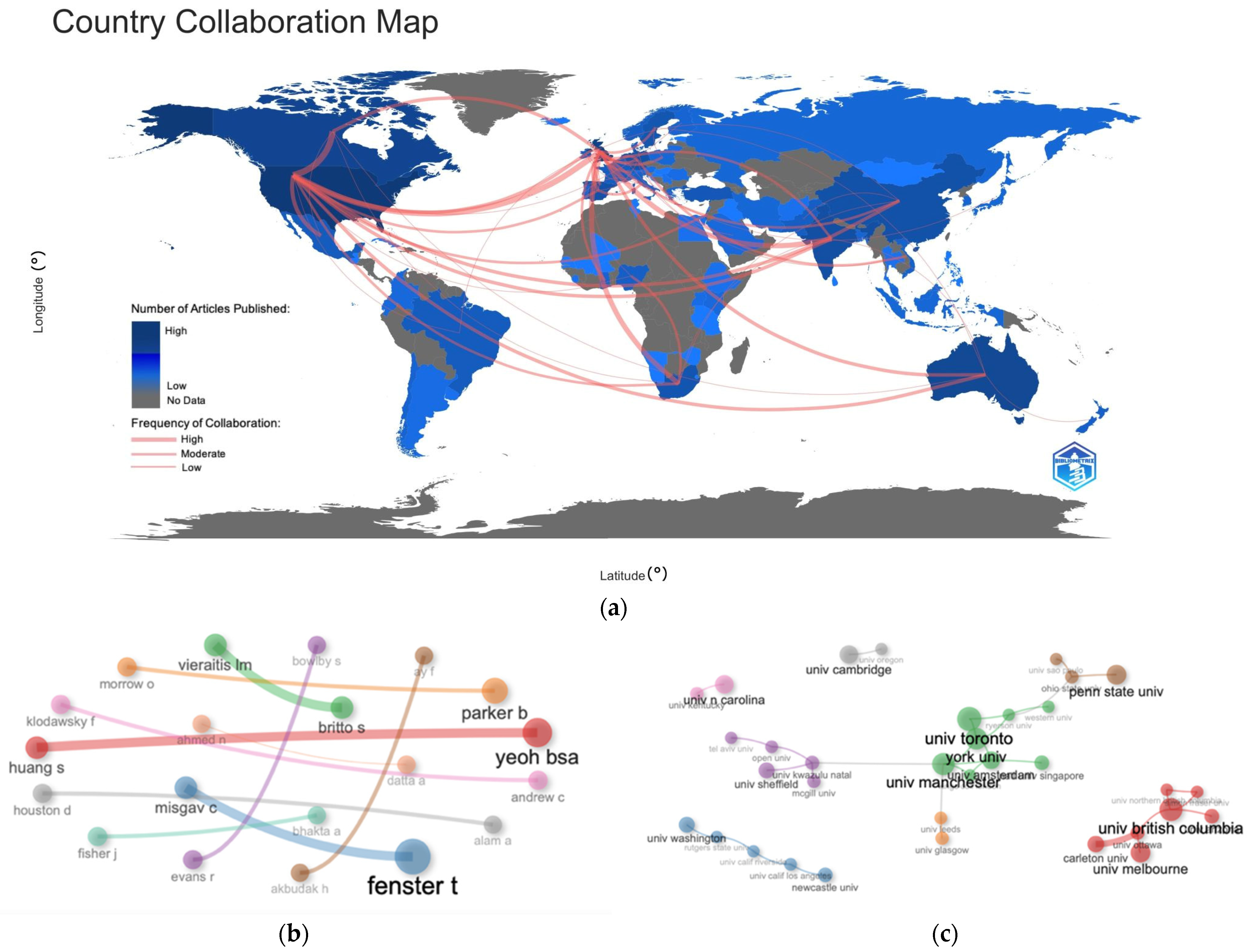

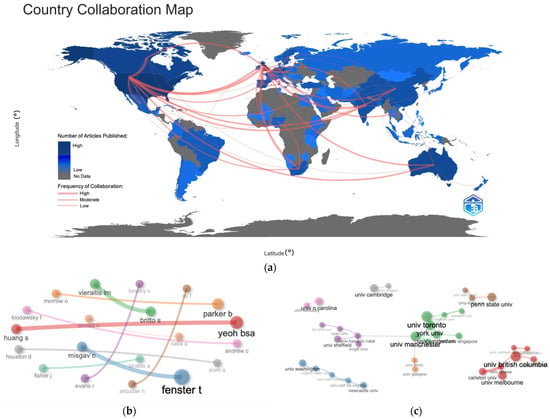

Collaboration and research partnerships can produce different levels of creativity and impact [112,113]. According to Ceballos et al. [114], research collaboration positively impacts production. WICR research has enhanced published co-authorship and national and institutional partnerships. Figure 9a shows the trajectory of international collaboration and country productivity correlation. The gradient of color indicates each country’s article publication count. The thickness of the edges indicates the level of collaboration between countries. The figure shows that the USA is the most active contributor to WICR research, publishing 572 articles and showing evidence of strong international collaborations. The USA often collaborates with the UK and Canada (more than eight times each), followed by the UK, Mexico, Australia, China, India, and Ireland. Similarly, the United Kingdom has a wide range of collaborations, most notably with India and South Africa, indicating a concentration on research ties with emerging economies. While the other nations have fewer collaborations, the figure highlights how crucial it is for countries to collaborate to progress scientific research in WICR, as some countries play a central role in the WICR research community.

Figure 9.

(a) Country collaboration network; (b) authors collaboration; and (c) institutional collaboration network generated from Bibliometrix. (The (b,c) networks include the 20 most active authors and the 34 most active universities contributing to the WICR studies. The edge thickness shows collaboration strength, the circle node size represents collaboration weight based on the number of publication counts, and the color represents clusters based on the Walktrap algorithm).

The author collaboration network illustrates the total number of co-authored papers. The network includes the 20 most active authors contributing to WICR research (Figure 9b). The nodes represent authors, with thicker edges suggesting more frequent collaboration and larger circle nodes presenting collaboration weight based on publication counts. Moreover, ten clusters were created using the Walktrap algorithm. Each color denotes a cluster of authors. Our findings show that collaborators from the same nation or region are common; the collaboration between Fenster T. and Misgav C. is the most central in the collaboration network, followed by Yeoh BSA. and Huang S.; the brown and pink cluster studies women-inclusive cities; the green–orange cluster addresses urban crime and violence; and the red cluster focuses on migrant workers, and the rest address infrastructure and politics.

Figure 9c shows the institutional partnership network. The size of the nodes reflects each institution’s number of publications, and the edge thickness shows their collaboration strength. The figure depicts eight major research clusters created using the Walktrap algorithm, each denoted by a different color. The USA, UK, and Canadian universities dominate. The green cluster is the largest cluster, wherein the University of Toronto becomes the center of the collaboration network.

One of the issues that emerges from these findings is that the collaboration between countries, institutions, and collaboration topics still needs to be improved. International scientific collaboration may encounter challenges, such as a shortage of researchers in relevant fields, inadequate funding, restrictions on exchanging materials and data, and disparities in academic standards [115,116]. By addressing these issues, we anticipate that WICR studies may grow and attract global interest to address the issue of gender inequities in urban areas.

3.5. Defining the Term “Women Inclusive City”

The Sustainable Development Goals #5 and #11, alongside the New Urban Agenda, underscore the importance of gender equity and the creation of safe, resilient, and inclusive cities. These serve as fundamental references for urban geographers globally, offering a comprehensive framework to explore the intricate connections between gender, urbanization, and sustainability [117,118,119]. Incorporating gender equity into the SDGs and the New Urban Agenda underscores the inseparability of urban development from social justice and human rights principles. By focusing on gender equality within urban environments, these documents challenge the entrenched norms and power dynamics that foster inequality and exclusion, which particularly affect women and marginalized groups [120]. The idea of an inclusive city extends beyond mere rhetoric to the use of innovative methods and technologies that empower women and girls, enabling them to become proactive participants in urban development [121,122].

Although the term “women-inclusive city” is not explicitly defined in the articles, they address related concepts, like gender inclusivity within urban contexts, women-friendly cities, and the broader idea of inclusive cities. Some authors reference definitions of an inclusive city provided by the United Nations and the Asian Development Bank. Chang et al. [123] cite the United Nations’ definition of an inclusive city as one where all individuals can actively and positively participate in the urban environment’s opportunities, regardless of socio-economic status, gender, age, ethnicity, or religion. He connects the concept of inclusivity to the women-friendly city concept in Korea, explaining that the term arises from gender mainstreaming and equity, acknowledging that women and men experience the urban environment differently. Thus, he promotes gender equality in participation and benefit sharing, emphasizing women. Some others adopt the Asian Development Bank’s definition of an inclusive city as one that equally values the needs of all its residents, creating a safe living environment with inexpensive and equitable access to urban and social services, as well as livelihood opportunities for everyone [121,124]. Varona [125] describes an inclusive city as user-friendly and a space that offers individuals the chance to develop skills for navigating challenges and engaging with diverse groups. Additionally, some authors also refer to cities of care where the city should embrace disability and disadvantaged people [126,127,128,129,130,131].

Our findings suggest that equality, accessibility, safety, democracy, female representation, and attention to ethics of care are all crucial factors a city should prioritize regarding its socio-economic and physical settings to create more inclusive cities for women. The most influential author in WICR studies, Beebeejaun [64], argues that recognizing multiple rights to the city and the contested publics that coexist within urban spaces can help identify more effective approaches to integrating diverse experiences into planning practices. Bondi’s [42] work emphasizes the impact of emancipatory notions of gender on public and private places. It highlights the intertwining of gender and class, with traditional gender implications frequently associated with wealthy middle-class lifestyles. Other academic researchers have established a connection between the idea of inclusive cities and both social sustainability and spatial accessibility. In their extensive work on the right to the city, they did not explicitly address gender in their conception of this right.

Nevertheless, equal access for all residents is encompassed by the right to the city [123]. Accessibility, a vital aspect of the physical structure of public areas, plays a crucial role in creating democratic spaces. It enables both locals and visitors to engage in community and civic events. Spaces that offer unrestricted access to diverse social groups serve as agents of transformation and nurture a communal sense of identity and belonging. A democratic public space, welcoming a myriad of diverse groups, mirrors the world’s diversity by fostering an environment where different communities coexist harmoniously [132]. Access to urban public places is critical for city democracy, as it represents the expansion of democratic rights. For public spaces to be genuinely democratic, two principles must be recognized: first, the city must be inclusive of all its inhabitants, with human rights as a fundamental requirement; and second, these spaces must provide a variety of values and qualities to meet the diverse needs of their diverse users [133,134,135,136]. Some authors discussed the importance of user-friendliness [137], safety [138], and participation in decision making [139] in the built environment. While some authors discussed the accessibility to urban physical settings, such as public space [118,132,140] and transportation [119,141,142,143], others discussed the accessibility in economics, politics, and technology. In the context of the economic aspect, some authors argue that the city should support women’s social reproduction of value [144], provide equal opportunities for employment [145], promote women’s empowerment and entrepreneurship [146,147], and ease women’s access to mobilize and pursue careers outside the home [148]. Additionally, in the context of politics, WICR should guarantee the freedom of women’s representation in public [149], participation in policy and decision making [150], and equal opportunities to become leaders in society [151]. Lastly, digital technology is crucial for all women and girls to access information and communicate their perspectives. It helps to promote their inclusion, participation, and rights in society. Some authors believe that intersectional theory is essential for understanding how people live and function well in various urban settings because digital technology is deeply affected by social and spatial processes of exclusion, inclusion, and enrichment [152,153]. Furthermore, some authors discuss the challenges faced by women in accessing electricity and digital inclusion [154] and how women derive advantages from the implementation of technology [155].

Overall, although the term “women-inclusive city” is explicitly undefined, the prevailing literature consistently implies a city where women’s rights are fully upheld, their needs are considered equally important, and their disabilities and disadvantages are accommodated. It ensures equal access for women to actively and positively engage in all facets of urban life, including its physical environment, economy, politics, and technology. This approach allows women to enjoy the same opportunities for self-development and representation as other genders, regardless of their socio-economic status.

4. Conclusions

Women have always suffered prejudice, which has limited access and opportunity in urban life. The critical importance of addressing these issues is recognized. Despite years of study, WICR studies keep expanding their scope, and the concept of “Women-inclusive cities” lacks a specific definition, highlighting the need for further equity-focused urban research. Through bibliometric analysis, we offer a comprehensive overview of WICR by analyzing its conceptual, intellectual, social, and descriptive dimensions, aiding academics and practitioners. A detailed analysis of WICR research published in WOSCC-indexed English articles from 1998 to 2022 was conducted, incorporating descriptive analysis and scientific mapping to trace the evolution and trends in WICR. Furthermore, systematic review approaches were employed to define the concept of a women-inclusive city.

In 1998, Bondi’s [42] work in Urban Geography Journal featured the first WICR publication. This groundbreaking work explores how gender and class shape urban public and private spaces, and it illuminates spatial equality and inclusivity, asking how cities may adapt to meet the different demands of their residents, while the most recent article challenges patriarchal ideals by portraying sex work as empowering for cisgender women, fostering social and economic resources. The annual growth of publications was not significant until the 2017 Women’s March took place in the United States, which sounded a protest against Trump’s misogynistic policies that threatened women’s rights. Scholars worldwide began to focus more on women’s rights and power dynamics in the cities, and the total publications each year in related subjects rose significantly.

Our study found that 44% of the top 100 cited papers over the previous three years have come from various empirical studies on mobility and active transportation, economic opportunities, ecology and climate justice, and digital technology. According to our study, scholars still use theoretical conceptions, surveys, and ethnographical investigations. Notable works include Truelove’s [50] exploration of gender inequality in urban political ecology, Doan’s [51] study of gendered space, and Till’s [52] discourse on the ethics of care. The co-citations are organized into nine distinct categories and cover different aspects of scholarly discourse, exploring important topics, such as feminist geography, which looks at how gender influences experiences in different spaces; intersectionality, which examines how social identities and systems of oppression intersect; feminist geopolitics, which analyzes the gendered dynamics of power and politics on a global scale; and women’s empowerment, which focuses on strategies and initiatives to enhance women’s agency and autonomy in urban areas. The categorizations presented here provide a detailed understanding of the complex nature of the research in the field of WICR, offering valuable insights for future exploration and analysis.

Thematic evolution maps have revealed a swift expansion in WICR research interests and have especially highlighted urban women’s disadvantages. Through the KeyWords Plus algorithm, we have observed a modest yet notable rise in studies focusing on “politics”, “space”, and “violence”. Despite their slight growth, these areas are emerging as significant future research directions in WICR. Additionally, our analysis forecasts a broadening research landscape from 2023, shifting towards topics like “informal settlement,” “local government”, “policies”, “participation”, “India”, “feminist theory”, and “power-relation”. The study landscape is broadening as interest in gender, urban policy, and societal structures grows across geographical and cultural contexts.

Meanwhile, we found a clear tendency for researchers from the same geographical backgrounds or regions to co-author papers. This pattern suggests a somewhat closed-off approach to collaboration, which may hinder the exchange of ideas and methods across different intellectual domains. The clusters identified in this analysis primarily address significant topics, including the feminist interpretation of urban spaces, the impact of urban crime and violence on women, the difficulties experienced by migrant workers, and the connections between infrastructure development and gender politics. The results emphasize the significance and immediacy of promoting greater international diversity in collaborative endeavors. Promoting cross-border collaboration is not only advantageous but also essential for enhancing the research domain of WICR. Collaborations between different cultures and academic disciplines can bring new viewpoints, creative approaches, and a more comprehensive examination of gender dynamics in urban environments.

Although we found that the term “women-inclusive city” does not have a precise definition, the available literature on the topic presents a coherent and persuasive vision. The text briefly overviews an urban environment that prioritizes the recognition, protection, and promotion of women’s rights. In such cities, women’s particular needs and viewpoints are treated equally with those of all other citizens, ensuring that gender inclusion is included in all aspects of urban design and government. Efforts must be made to recognize and tackle the unique challenges, disabilities, and disadvantages that women may encounter. These solutions should seamlessly integrate into the city’s infrastructure and social systems. Embracing a comprehensive and interconnected approach creates a space where women can confidently pursue equal opportunities for personal and professional growth, alongside men and individuals of other genders. This indicates a transition towards a fairer urban society, where the efforts and ambitions of women are recognized and encouraged regardless of their socio-economic status.

This review, conducted using the R-package Bibliometrix, provides an in-depth understanding of the trends, impact, collaboration, and visibility in WICR studies. It underscores the existing knowledge gap and emphasizes the need for further research to address the challenges women face in urban life, such as ethics of care, digital inclusion, geopolitical diversity, and queer issues. It also highlights the urgency of ensuring equal access for women to achieve a women-inclusive city. An analysis spanning two decades has illuminated this domain’s social and intellectual structure, unveiling emerging subjects and settings and potential partnerships for future scholars. Importantly, by defining the term “Women Inclusive City”, this study fills a conceptual gap, providing valuable insights for researchers and policymakers engaged in WICR studies. However, this study has several limitations. The first significant limitation is the restriction of keywords and selection criteria. Upon conducting a thorough keyword analysis, we discovered that WICR studies extend beyond the keywords set in this study, encompassing broader terms such as “Gender Equal Cities” and “Care Cities”. Future studies should consider incorporating these keywords for a more holistic and accurate view of WICR study trends. Secondly, an inherent bias exists in the data sources used. This study relies on the Web of Science Core Collection, suggesting that future research should consider expanding the bibliographic source databases for a more comprehensive and accurate representation of WICR studies. Thirdly, this bibliographic analysis was primarily conducted using a quantitative method. Future research could benefit from a thorough qualitative approach to validate or expand upon the findings of this study, considering that the interpretation of selected publications in the qualitative analysis may vary among researchers due to differences in expertise.

Author Contributions

R.L.H. played a part in the whole conception, data retrieval, software processing, and analysis and wrote the manuscript; C.H. played a part in review, added suggestions, and edited the draft of manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific funding from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding entities. This study did not receive any external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request to corresponding authors (R.L.H.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UN Women. Progress of the World’s Women 2019–2020: Families in a Changing World; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2019/06/progress-of-the-worlds-women-2019-2020 (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Bird, S.R.; Sapp, S.G. Understanding the Gender Gap in Small Business Success: Urban and Rural Comparisons. Gend. Soc. 2004, 18, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.B.; Stern, M.J.; Fader, J.J. Women and the Paradox of Economic Inequality in the Twentieth-Century. J. Soc. Hist. 2005, 39, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrix (Organization) (Ed.) Making Space: Women and the Man-Made Environment; Pluto Press: London, UK, 1984; ISBN 978-0-86104-601-0. [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, L.; Castellaneta, M. Women and Cities. The Conquest of Urban Space. Front. Sociol. 2023, 8, 1125439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, Y. Conceptualizing the Inclusive City from Multidimensional Perspectives. LHI J. Land Hous. Urban Aff. 2020, 11, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, P. Inclusive City, Perspectives, Challenges, and Pathways. In Sustainable Cities and Communities; Leal Filho, W., Marisa Azul, A., Brandli, L., Gökçin Özuyar, P., Wall, T., Eds.; Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 290–300. ISBN 978-3-319-95716-6. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. The Global Campaign on Urban Governance; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D.; De Jong, M.; Schraven, D.; Wang, L. Mapping Key Features and Dimensions of the Inclusive City: A Systematic Bibliometric Analysis and Literature Study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2022, 29, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoaty, A.; Saadallah, D.; Bakr, A. Gender Mainstreaming and Women’s Involvement in Urban Planning Strategies. In Proceedings of the Second Arab Land Conference, Cairo, Egypt, 22–24 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, N. ‘She-Spots’ Attempt to Make South Korea More ‘Women-Friendly’. The Washington Post. 29 May 2014. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2014/05/29/she-spots-attempt-to-make-south-korea-more-women-friendly/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Kern, L. Feminist City; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-78873-981-8. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, J.M. Contemporary Urban Planning, 11th ed.; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-138-66638-2. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire, X.; Kerr, D. Inclusive Urban Planning—Promoting Equality and Inclusivity in Urban Planning Practices; UCL Energy Institute/SAMSET: London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10040319/1/SAMSET%20-%20UCL%20-%20Inclusive%20Urban%20Planning%20-%20Sept%202017.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Terraza, H.; Orlando, M.B.; Lakovits, C.; Lopes Janik, V.; Kalashyan, A. Handbook for Gender-Inclusive Urban Planning and Design; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Apolitical. Vienna: A City Designed for Women. Available online: https://apolitical.co/solution-articles/en/vienna-designed-city-women (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Adlakha, D.; Parra, D.C. Mind the Gap: Gender Differences in Walkability, Transportation and Physical Activity in Urban India. J. Transp. Health 2020, 18, 100875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Huang, X.; White, M.; Langenheim, N. Walkability Perceptions and Gender Differences in Urban Fringe New Towns: A Case Study of Shanghai. Land 2023, 12, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayati, I.; Tan, W.; Yamu, C. How Gender Differences and Perceptions of Safety Shape Urban Mobility in Southeast Asia. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 73, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.A.; Juran, L.; Ajibade, I. ‘Spaces of Exclusion’ in Community Water Governance: A Feminist Political Ecology of Gender and Participation in Malawi’s Urban Water User Associations. Geoforum 2018, 95, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, M.R.; Hernandez-Garcia, J. Informal Urbanization in Bogota, between Theory and Urban Policy. Urbe-Rev. Bras. Gest. Urbana 2022, 14, e20210276. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelwahed, N.A.A.; Bastian, B.L.; Wood, B.P. Women, Entrepreneurship, and Sustainability: The Case of Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, L.; McLean, H. Undecidability and the Urban: Feminist Pathways through Urban Political Economy. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 2017, 16, 405–426. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, N.; Tasmin, M.; Ibrahim, S.M.N. Technology for Empowerment: Context of Urban Afghan Women. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 102058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asteria, D.; Jap, J.J.K.; Utari, D. A Gender-Responsive Approach: Social Innovation for the Sustainable Smart City in Indonesia and Beyond. J. Int. Women’s Stud. 2020, 21, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Itair, M.; Shahrour, I.; Hijazi, I. The Use of the Smart Technology for Creating an Inclusive Urban Public Space. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 2484–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.C.; Johnson, L.; Dzombo, M.N. Sanitation-Related Violence against Women in Informal Settlements in Kenya: A Quantitative Analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1191101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirra, M.; Kalakou, S.; Lynce, A.R.; Carboni, A. Walking in European Cities: A Gender Perception Perspective. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 69, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Indonesia Country Gender Assessment: Investing in Opportunities for Women; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap Report 2022; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBurney, M.K.; Novak, P.L. What Is Bibliometrics and Why Should You Care? In Proceedings of the IEEE International Professional Communication Conference, Portland, OR, USA, 20 September 2002; Labors of Love: Sex, Work, and Good Mothering in the Globalizing Cit. pp. 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Zupic, I.; Cater, T. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, M. Worldwide Trends in Prediabetes from 1985 to 2022: A Bibliometric Analysis Using Bibliometrix R-Tool. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1072521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anugerah, A.R.; Muttaqin, P.S.; Trinarningsih, W. Social Network Analysis in Business and Management Research: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Research Trend and Performance from 2001 to 2020. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-H.K.; Seto, K.C. Gender and Authorship Patterns in Urban Land Science. J. Land Use Sci. 2022, 17, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Shuai, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Shuai, J. Topic Modelling of Ecology, Environment and Poverty Nexus: An Integrated Framework. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 267, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidescu, A.A.; Petcu, M.A.; Curea, S.C.; Manta, E.M. The Relationship between Informality and Sustainable Development Goals through Text Analysis. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2023, 30, 1946–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirhashemi, A. Macro-Level Literature Analysis on Pedestrian Safety: Bibliometric Overview, Conceptual Frames, and Trends. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 174, 106720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.K.; Muhuri, P.K.; Abraham, A. A Bibliometric Analysis and Cutting-Edge Overview on Fuzzy Techniques in Big Data. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 92, 103625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.; Lopez-Herrera, A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. Science Mapping Software Tools: Review, Analysis, and Cooperative Study Among Tools. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 1382–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondi, L. Gender, class, and urban space: Public and private space in contemporary urban landscapes. Urban Geogr. 1998, 19, 160–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, G. Labors of Love: Sex, Work, and Good Mothering in the Globalizing City. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 2022, 47, 665–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. A Manifesto against Femicide. Antipode 2001, 33, 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenster, T. The Right to the Gendered City: Different Formations of Belonging in Everyday Life. J. Gend. Stud. 2005, 14, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B. Feminist Forays in the City: Imbalance and Intervention in Urban Research Methods. Antipode 2016, 48, 1337–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.; Wang, W.; Laengle, S.; Merigo, J.; Yu, D.; Herrera-Viedma, E. Co-Words Analysis of the Last Ten Years of the International Journal of Uncertainty, Fuzziness and Knowledge-Based Systems. In Proceedings of the Information Processing and Management of Uncertainty in Knowledge-Based Systems. Applications: 17th International Conference, IPMU 2018, Cádiz, Spain, 11–15 June 2018; Medina, J., OjedaAciego, M., Verdegay, J., Perfilieva, I., BouchonMeunier, B., Yager, R., Eds.; Universidad de Cadiz: Cádiz, Spain, 2018; Volume 855, pp. 667–677. [Google Scholar]

- Beliaeva, T. Marketing and Family Firms: Theoretical Roots, Research Trajectories, and Themes. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista-Canino, R.M.; Santana-Hernández, L.; Medina-Brito, P. A Scientometric Analysis on Entrepreneurial Intention Literature: Delving Deeper into Local Citation. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truelove, Y. Rethinking Water Insecurity, Inequality and Infrastructure through an Embodied Urban Political Ecology. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2019, 6, e1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, P.L. The Tyranny of Gendered Spaces—Reflections from beyond the Gender Dichotomy. Gend. Place Cult. 2010, 17, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, K.E. Wounded Cities: Memory-Work and a Place-Based Ethics of Care. Political Geogr. 2012, 31, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, C. The Personal Is Political: Developing New Subjectivities through Participatory Action Research. Gend. Place Cult. 2007, 14, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzar, S.; Ogden, P.; Hall, R. Households Matter: The Quiet Demography of Urban Transformation. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2005, 29, 413–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suffoletto, B.; Callaway, C.; Kristan, J.; Kraemer, K.; Clark, D.B. Text-Message-Based Drinking Assessments and Brief Interventions for Young Adults Discharged from the Emergency Department. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 36, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRobbie, A. Young Women and Consumer Culture—An Intervention. Cult. Stud. 2008, 22, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, E.J. Just How Do I Love Thee?: Marital Relations in Urban China. J. Marriage Fam. 2002, 62, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibade, I.; McBean, G.; Bezner-Kerr, R. Urban Flooding in Lagos, Nigeria: Patterns of Vulnerability and Resilience among Women. Glob. Environ. Chang.-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2013, 23, 1714–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldred, R.; Woodcock, J.; Goodman, A. Does More Cycling Mean More Diversity in Cycling? Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunnell, T.; Maringanti, A. Practising Urban and Regional Research beyond Metrocentricity. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 34, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landale, N.; Oropesa, R.; Gorman, B. Migration and Infant Death: Assimilation or Selective Migration among Puerto Ricans? Am. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 65, 888–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, L. Elites in the City of London: Some Methodological Considerations. Environ. Plan. A 1998, 30, 2133–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenberg, E. En-Gendering Effective Planning—Spatial Mismatch, Low-Income Women, and Transportation Policy. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2004, 70, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebeejaun, Y. Gender, Urban Space, and the Right to Everyday Life. J. Urban Aff. 2017, 39, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonders, N.; Michalowski, R. Bodies, Borders, and Sex Tourism in a Globalized World: A Tale of Two Cities—Amsterdam and Havana. Soc. Probl. 2001, 48, 545–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, J. What’s in a Label? The Relationship between Feminist Self-Identification and “Feminist” Attitudes among US Women and Men. Gend. Soc. 2005, 19, 480–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.M. The Two-Ness of Rural Life and the Ends of Rural Scholarship. J. Rural. Stud. 2007, 23, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvey, R.; Elmhirst, R. Engendering Social Capital: Women Workers and Rural-Urban Networks in Indonesia’s Crisis. World Dev. 2003, 31, 865–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, J. Staging the Nation—Gendered and Ethnicized Discourses of National Identity in Olympic Opening Ceremonies. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2003, 27, 100–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, A. Working the Socio-Natural Relations of the Urban Waterscape in South Africa. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2007, 31, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G. Posthuman Agency in the Digitally Mediated City: Exteriorization, Individuation, Reinvention. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2017, 107, 779–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwood, S.; Leszczynski, A. Feminist Digital Geographies. Gend. Place Cult. 2018, 25, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; White, N. Gender and Adolescent Relationship Violence: A Contextual Examination. Criminology 2003, 41, 1207–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, Y. (Re-)Conceptualizing Water Inequality in Delhi, India through a Feminist Political Ecology Framework. Geoforum 2011, 42, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peake, L. The Twenty-First-Century Quest for Feminism and the Global Urban. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2016, 40, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovorka, A.J. The No. 1 Ladies’ Poultry Farm: A Feminist Political Ecology of Urban Agriculture in Botswana. Gend. Place Cult. 2006, 13, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heynen, N. Urban Political Ecology III: The Feminist and Queer Century. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2018, 42, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, L. Nourishing Women: Toward a Feminist Political Ecology of Community Supported Agriculture in the United States. Gend. Place Cult. 2011, 18, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, M.; Strauss, K. With, against and beyond Lefebvre: Planetary Urbanization and Epistemic Plurality. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2016, 34, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. From Protests to Politics: Sex Work, Women’s Worth, and Ciudad Juarez Modernity. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2004, 94, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitzman, C.; Andrew, C.; Viswanath, K. Partnerships for Women’s Safety in the City: “Four Legs for a Good Table”. Environ. Urban. 2014, 26, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jupp, E. Women, Communities, Neighbourhoods: Approaching Gender and Feminism within UK Urban Policy. Antipode 2014, 46, 1304–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graglia, A.D. Finding Mobility: Women Negotiating Fear and Violence in Mexico City’s Public Transit System. Gend. Place Cult. 2016, 23, 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, S.; Waitt, G. Walking, Mothering and Care: A Sensory Ethnography of Journeying on-Foot with Children in Wollongong, Australia. Gend. Place Cult. 2017, 24, 1185–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.J. Care-Full Justice in the City. Antipode 2017, 49, 821–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, E.R.; Williams, M.J. Cities of Care: A Platform for Urban Geographical Care Research. Geogr. Compass 2020, 14, e12474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, R. The Paradoxical Relationship between Gender Inequality and Rape—Toward a Refined Theory. Gend. Soc. 2001, 15, 531–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. Paradoxes, Protests and the Mujeres de Negro of Northern Mexico. Gend. Place Cult. 2005, 12, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, C.; Roberts, S.M. Not Everyone Has (the) Balls: Urban Exploration and the Persistence of Masculinist Geography. Antipode 2014, 46, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclean, H. Digging into the Creative City: A Feminist Critique. Antipode 2014, 46, 669–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.K.; Song, M.; Ding, Y. Content-Based Author Co-Citation Analysis. J. Informetr. 2014, 8, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.B. Space, Place, and Gender, 6th ed.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-8166-2617-5. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, G. The Geography of Women’s Fear. Area 1989, 21, 385–390. [Google Scholar]

- Bondi, L. Empathy and Identification: Conceptual Resources for Feminist Fieldwork. ACME Int. J. Crit. Geogr. 2003, 2, 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, C.T. “Under Western Eyes” Revisited: Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles. Signs 2003, 28, 499–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, D. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-415-90387-5. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, G. Theorizing and Researching Intersectionality: A Challenge for Feminist Geography. Prof. Geogr. 2007, 59, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, L. The Complexity of Intersectionality. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 2005, 30, 1771–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, J. Mind the Gap: Bridging Feminist and Political Geography through Geopolitics. Political Geogr. 2004, 23, 307–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, J. Towards a Feminist Geopolitics. Can. Geogr. 2001, 45, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, S. Embodied Urban Political Ecology: Five Propositions. Area 2017, 49, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollett, S.; Faria, C. Messing with Gender in Feminist Political Ecology. Geoforum 2013, 45, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronto, J.C. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-00-307067-2. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, V. Geographies of Care and Responsibility. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2007, 97, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandiyoti, D. Bargaining with Patriarchy. Gend. Soc. 1988, 2, 274–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Dev. Chang. 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Jin, Z.; Qiu, J. Global Isotopic Hydrograph Separation Research History and Trends: A Text Mining and Bibliometric Analysis Study. Water 2021, 13, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cosmo, A.; Pinelli, C.; Scandurra, A.; Aria, M.; D’Aniello, B. Research Trends in Octopus Biological Studies. Animals 2021, 11, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, K.; Yu, Y.; Yang, B. Mapping of Water Footprint Research: A Bibliometric Analysis during 2006–2015. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A. Articles—Principal Component Methods in R: Practical Guide. MCA—Multiple Correspondence Analysis in R: Essentials. STHDA-Stat. Tools High-Throughput Data Anal. 2017, 2, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Coccia, M.; Bozeman, B. Allometric Models to Measure and Analyze the Evolution of International Research Collaboration. Scientometrics 2016, 108, 1065–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.H.T.; Duch, J.; Sales-Pardo, M.; Moreira, J.A.G.; Radicchi, F.; Ribeiro, H.V.; Woodruff, T.K.; Amaral, L.A.N. Differences in Collaboration Patterns across Discipline, Career Stage, and Gender. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, H.G.; Fangmeyer, J.; Galeano, N.; Juarez, E.; Cantu-Ortiz, F.J. Impelling Research Productivity and Impact through Collaboration: A Scientometric Case Study of Knowledge Management. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2017, 15, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, A.; Hamutumwa, N.; Mabuku, M. A Bibliometric Analysis of How Research Collaboration Influences Namibia’s Research Productivity and Impact. SN Soc. Sci. 2022, 2, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, K.R.W.; Yang, E.; Lewis, S.W.; Vaidyanathan, B.R.; Gorman, M. International Scientific Collaborative Activities and Barriers to Them in Eight Societies. Account. Res. 2020, 27, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluko, Y.A.; Okuwa, O.B. Innovative Solutions and Women Empowerment: Implications for Sustainable Development Goals in Nigeria. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2018, 10, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevia, D.; Lathia, S. Women’s Safety and Public Spaces: Lessons from the Sabarmati Riverfront, India. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thynell, M. The Quest for Gender-Sensitive and Inclusive Transport Policies in Growing Asian Cities. Soc. Incl. 2016, 4, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, A.A.; Legesse, A.T.; Feleke, G.G. Women’s Safety and Security in Public Transport in Mekelle, Tigray. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2022, 10, 2443–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geropanta, V.; Cornelio-Marí, E.M. Inclusiveness and Participation in the Design of Public Spaces: Her City and the Challenge of the Post-Pandemic Scenario. Int. J. E-Plan. Res. 2022, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siltanen, J.; Klodawsky, F.; Andrew, C. “This Is How I Want to Live My Life”: An Experiment in Prefigurative Feminist Organizing for a More Equitable and Inclusive City. Antipode 2015, 47, 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-I.; Choi, J.; An, H.; Chung, H.-Y. Gendering the Smart City: A Case Study of Sejong City, Korea. Cities 2022, 120, 103422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampaul, K.; Magidimisha-Chipungu, H. Gender Mainstreaming in the Urban Space to Promote Inclusive Cities. J. Transdiscipl. Res. S. Afr. 2022, 18, a1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varona, G. Defensive Urbanism and Local Governance: Perspectives from the Basque Country. Onati Socio-Legal Series 2021, 11, 1273–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Houston, D. Rethinking Care as Alternate Infrastructure. Cities 2020, 100, 102662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrucki, M.J. Queering Social Reproduction: Sex, Care and Activism in San Francisco. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 1364–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A. Liquid Home? Financialisation of the Built Environment in the UK’s “Hotel-Style” Care Homes. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2021, 46, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kussy, A.; Palomera, D.; Silver, D. The Caring City? A Critical Reflection on Barcelona’s Municipal Experiments in Care and the Commons. Urban Stud. 2022, 60, 2036–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, E.R. Assembling the Capacity to Care: Caring-with Precarious Housing. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2019, 44, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.J. The Possibility of Care-Full Cities. Cities 2020, 98, 102591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.M.; Miles, R. Toward More Inclusive Public Spaces: Learning from the Everyday Experiences of Muslim Arab Women in New York City. Environ. Plan. A-Econ. Space 2014, 46, 1892–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, N.; Asl, S.R. A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Democracy Dimensions in Public Spaces: The Case of 30Tir Street in Tehran. J. Reg. City Plan. 2022, 33, 24–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnington, C.; Russo, A. Defensive Landscape Architecture in Modern Public Spaces. Ri-Vista. Res. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 19, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, C.; Libetta, A.; Conticelli, E.; Tondelli, S. Accessibility to and Availability of Urban Green Spaces (UGS) to Support Health and Wellbeing during the COVID-19 Pandemic-The Case of Bologna. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrini, A.; Choubassi, R.; Messa, F.; Saleh, W.; Ababio-Donkor, A.; Leva, M.C.; D’Arcy, L.; Fabbri, F.; Laniado, D.; Aragon, P. Unveiling Women’s Needs and Expectations as Users of Bike Sharing Services: The H2020 DIAMOND Project. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann-Lunecke, M.G.; Mora, R.; Vejares, P. Perception of the Built Environment and Walking in Pericentral Neighbourhoods in Santiago, Chile. Travel Behav. Soc. 2021, 23, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouali, L.A.B.; Graham, D.J.; Barron, A.; Trompet, M. Gender Differences in the Perception of Safety in Public Transport. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A-Stat. Soc. 2020, 183, 737–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirgwin, H.; Cairncross, S.; Zehra, D.; Waddington, H.S. Interventions Promoting Uptake of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Technologies in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: An Evidence and Gap Map of Effectiveness Studies. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2021, 17, e1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeles, L.C.; Roberton, J. Empathy and Inclusive Public Safety in the City: Examining LGBTQ2+voices and Experiences of Intersectional Discrimination. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2020, 78, 102313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, B. Speculating with Human Rights: Two South Asian Women Writers and Utopian Mobilities. Mobilities 2020, 15, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwittay, A. Designing Urban Women’s Safety: An Empirical Study of Inclusive Innovation Through a Gender Transformation Lens. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2019, 31, 836–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.K. Planning with Urban Informality: A Case for Inclusion, Co-Production and Reiteration. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2016, 38, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzadri, A. A Value Theory of Inclusion: Informal Labour, the Homeworker, and the Social Reproduction of Value. Antipode 2021, 53, 1186–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, V.A. Relocating the “Inmate”: Tracing the Geographies of Social Reproduction in Correctional Supervision. Environ. Plan. C-Politics Space 2020, 38, 1216–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo Garcia, E.; Canete Perez, J.A.; Navarro Valverde, F.; Ruiz Moya, N. Entrepreneurs and Territorial Diversity: Success and Failure in Andalusia 2007–2015. Land 2020, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Jullandhry, S. Are Urban Women Empowered in Pakistan? A Study from a Metropolitan City. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2020, 82, 102390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, J.; Blumenberg, E.; Brumbaugh, S. Driven to Debt: Social Reproduction and (Auto)Mobility in Los Angeles. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2021, 111, 1445–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, C.R. Representations of Utopian Urbanism and the Feminist Geopolitics of ?New City? Development. Urban Geogr. 2019, 40, 1148–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boren, T.; Grzys, P.; Young, C. Policy-Making as an Emotionally-Charged Arena: The Emotional Geographies of Urban Cultural Policy-Making. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2021, 27, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M. The Gendered (Di)-Vision of the Rebellion: The Public and the Private in Life Histories of Female and Male Union Leaders, Salvador-Bahia-Brazil. Identities-Glob. Stud. Cult. Power 1998, 5, 65–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwood, S. Digital Geographies, Feminist Relationality, Black and Queer Code Studies: Thriving Otherwise. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 45, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanditha, N. Exclusion in #MeToo India: Rethinking Inclusivity and Intersectionality in Indian Digital Feminist Movements. Fem. Media Stud. 2022, 22, 1673–1694. [Google Scholar]

- Houngbonon, G.V.; Le Quentrec, E.; Rubrichi, S. Access to Electricity and Digital Inclusion: Evidence from Mobile Call Detail Records. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, N.H.; Kah, M.M.O. Mobile Phones and Social Inclusion of Women in Africa: A Nigerian Perspective. Afr. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 13, 241–258. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).