Housing Practices of Albanian Immigrants in Athens: An “in-between” Socio-Spatial Condition

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Contextual and Theoretical Factors

2.1. Micro-Segregation Trends in Athens

2.2. Contextual Evidence on the Athenian Housing Market

2.3. Albanians in Athens: Arrival, Socio-Spatial Settlement, and Vulnerabilities

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Albanian Socioeconomic Profile

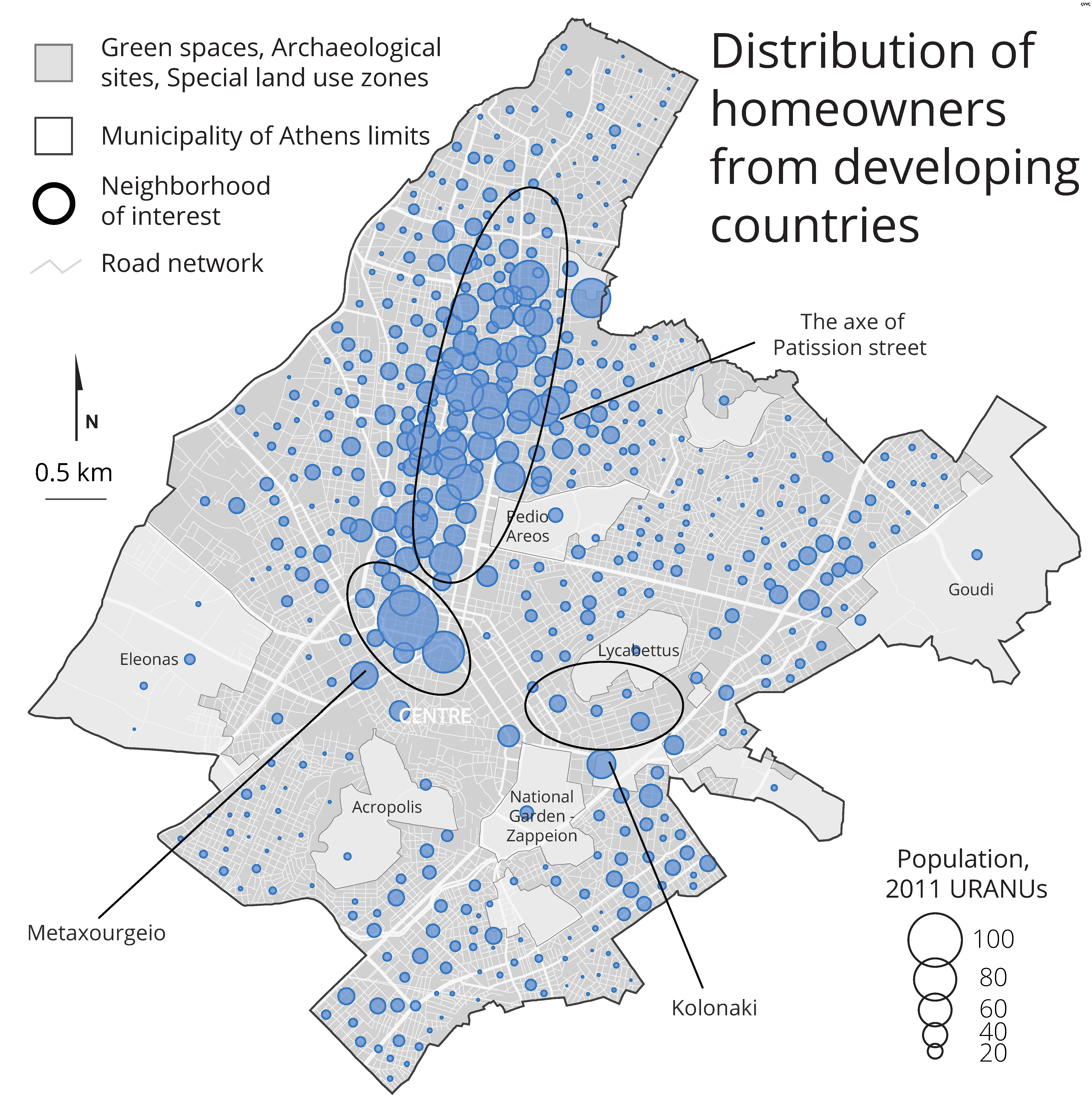

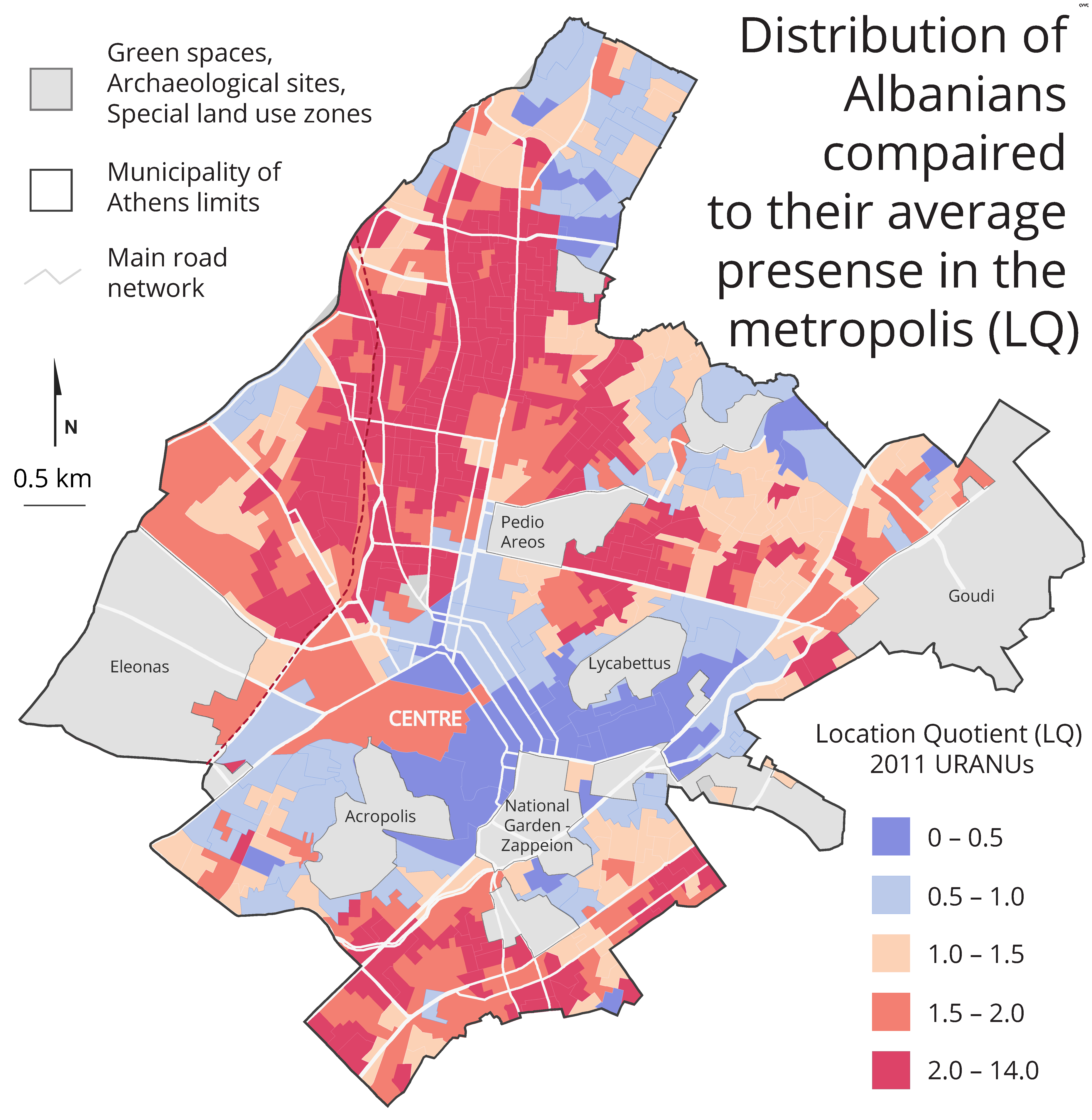

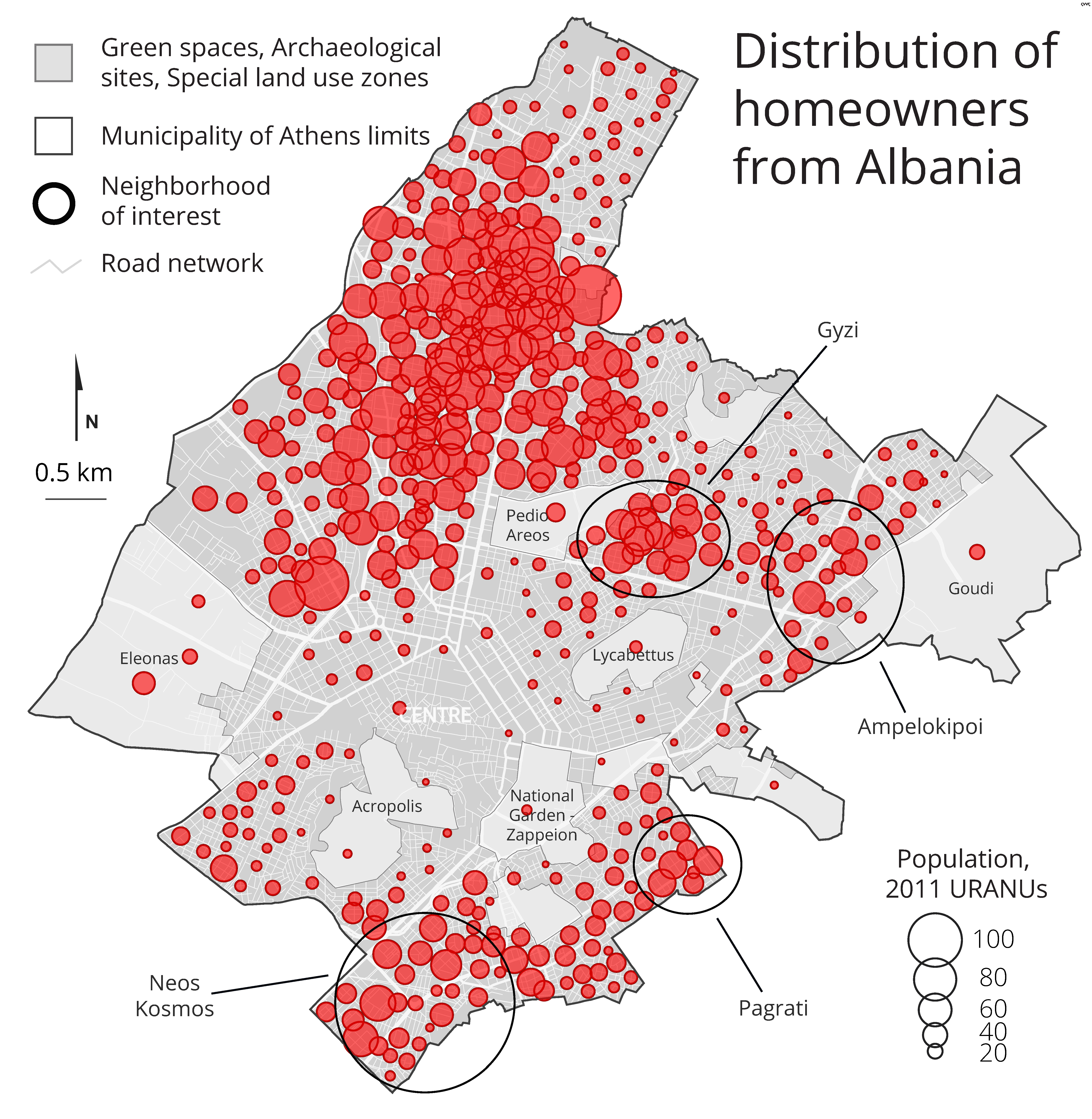

4.2. Urban Settlement of Albanian Immigrants in the Municipality of Athens: An “in-between” Situation

4.3. Housing Pathways: Between Geographic Dispersal, Social Mobility, and Multiple Marginalities

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Code ID | Role/Function | Place of Meeting | Date of Meeting |

|---|---|---|---|

| EX.INT.01 | Professor, Aleksander Moisiu University | Online (Durrës) | 19 April 2022 |

| EX.INT.02 | Professor, University of Western Attica | Online (Athens) | 10 March 2023 |

| EX.INT.03 | Postdoctoral Researcher, Aegean University | Athens | 2 June 2022 |

| EX.INT.04 | Member of an Albanian association in Athens | Online (Athens) | 3 March 2023 |

| EX.INT.05 | Member of the Greek Forum for Migrants | Online (Athens) | 13 July 2022 |

| Title | Place of Meeting | Participants | Date of Meeting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Policy Council Event. Media representations and self-representation of migrants in COVID-19 Times. | Online (Athens) | ACCMR, Municipality of Athens, IOM, NGO Intersos, NGO Babel, NGO Nostos, NGO Praxis, Greek Council for Refugees, Greek Forum of Migrants, Migrant Intercultural, Mediator Integration Centers, National Kapodistrian University of Athens (NKUA) | 18 February 2022 |

| National Policy Council Event. Media representations and self-representations ofmigrants in COVID-19 Times. | Online (Athens) | ACCMR, Migrant Intercultural, Mediator Integration Centers, IOM, Greek Council for Refugees, Migrants’ Integration Center (M.I.C) in the Municipality of Athens, Greek Organization of Public Health (EODY), NGO NOSTOS, NGO PRAXIS, Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) | 11 March 2022 |

| Training session. “How the Ngos can become active protagonists of the collection and preservation of migrants’ narratives” | Athens, NKUA, Department of Economics | Centre for Asia Minor Studies, Institute of Historical, Research of the National Hellenic Research Foundation (IHR/NHRF), Greek Forum of refugees, NGO Babel, Greek Forum of migrants, Sams-USA, University of West Attica, National Centre for Social Research (EKKE) | 29–30 September 2023 |

| Local Policy Council Event. Acted, narrated, deconstructed: how research may influence European migration policies. | Online (Athens) | University of Cyprus, UNHCR, Migrants’ Integration Center (M.I.C) in the Municipality of Athens, Federation of Albanian Associations in Greece | 3 March 2023 |

| National Policy Council Event. Acted, narrated, deconstructed: how research may influence European migration policies. | Online (Athens) | Federation of Albanian Associations in Greece, Ministry of Migration & Asylum, Greek Forum of refugees, University of West Attica | 10 March 2023 |

| Code ID | Household Composition during the Day of the Interview—Present Members | Date of Birth of the Principal Household Informant) | Year of the Household Settlement in Greece | Place and Date of Interview |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HS.INT.01 (Eleni) | 4 members: husband, wife, wife’s father, and daughter | 1979 | 1997 | Athens, 8 March 2023 |

| HS.INT.02 (Agni) | 5 members: husband, wife, husband’s mother, two sons | 1972 | 1992 | Athens, 3 April 2023 |

| HS.INT.03 (Mari) | 4 members: husband, wife, two sons | 1965 | 1995 | Athens, 5 April 2023 |

| HS.INT.04 (Irini) | 4 members: husband, wife, daughter, son | 1980 | 1998 | Athens, 5 April 2023 |

| HS.INT.05 (Liza) | 3 members: husband, wife, son | 1970 | 1995 | Athens, 5 April 2023 |

| HS.INT.06 (Zoe) | 4 members: husband, wife, daughter, son | 1978 | 1997 | Athens, 10 April 2023 |

| HS.INT.07 (Afroditi) | 3 members: husband, wife, son | 1949 | 1993 | Athens, 10 April 2023 |

| HS.INT.08 (Vasiliki) | 4 members: husband, wife, two daughters | 1971 | 1998 | Athens, 3 April 2023 |

| 1. | For the 1998 and 2001 legalization procedures, see [38]. |

| 2. | The distinction between developed and developing countries was made according to the UN’s Human Development Index [44] (127–130). http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/hdr/human_developmentreport2011.html (accessed on 22 June 2024). |

| 3. | These units are a modified version of the 2011 Census Tracts (CTs) produced by the Panorama of Greek Census Data 1991–2011 team to bypass confidentiality issues in sparsely populated Census Tracts. The metropolitan area comprises 3000 URANUs with an average population of 1250, and the municipality of Athens comprises 494 URANUs with an average population of 1330. |

| 4. | It is critical to underline that while the informants were female members of the aforementioned NGO, the questionnaire used—designed specifically for the needs of the ITHACA program—collects information about the households as a whole. As a result, this policy paper observes the issue of household integration, not focusing especially on women’s housing integration experience. |

References

- Musterd, S. Social and Ethnic Segregation in Europe: Levels, Causes, and Effects. J. Urban Aff. 2005, 27, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbaci, S. (Re)Viewing Ethnic Residential Segregation in Southern European Cities: Housing and Urban Regimes as Mechanisms of Marginalisation. Hous. Stud. 2008, 23, 589–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettas, D.; Avdikos, V.; Papageorgiou, A. Platform—Driven housing commodification, financialisation and gentrification in Athens. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloutas, T.; Siatitsa, D.; Balampanidis, D. Access to Housing and Social Inclusion in a Post-Crisis Era: Contextualizing Recent Trends in the City of Athens. Soc. Incl. 2020, 8, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakou, I. Vacancy, Access to Housing and Micro-segregation. Bull. De Corresp. Hellénique Mod. Et Contemp. 2022, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balampanidis, D.; Maloutas, T.; Papatzani, E.; Pettas, D. Informal urban regeneration as a way out of the crisis? Airbnb in Athens and its effects on space and society. Urban Res. Pract. 2021, 14, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, D. Socio-economic inequalities and housing in Athens: Impacts of the monetary revolution of the 1990s. Greek Rev. Soc. Res. 2004, 113, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavounidis, J. Migration and the Economic and Social Landscape of Greece. South-East. Eur. J. Econ. 2013, 11, 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gemi, E. Transnational practices of Albanian families during the Greek crisis: Unemployment, de-regularization and return. Int. Rev. Sociol. 2014, 24, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gropas, R.; Triandafyllidou, A. Migrants and Political Life in Greece: Between Political Patronage and the Search for Inclusion. South Eur. Soc. Politics 2012, 17, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandylis, G.; Maloutas, T. From Laissez-Faire to the Camp: Immigration and the Changing Models of Affordable Housing Provision in Athens. In New Developments in Southern European Housing after the Crisis; Pisa University Press: Pisa, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Karadimitriou, N.; Maloutas, T.; Arapoglou, V.P. Multiple Deprivation and Urban Development in Athens, Greece: Spatial Trends and the Role of Access to Housing. Land 2021, 10, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, D. The Greek System of Home Ownership and the Post-2008 Crisis in Athens. Région Et Développement 2014, 39, 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Arapoglou, V.P.; Spyrellis, S.N. Arrival Infrastructures: Segregation of Displaced Migrants and Processes of Urban Change in Athens. Geographies 2024, 4, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatzani, E.; Psallidaki, T.; Kandylis, G.; Micha, I. Multiple geographies of precarity: Accommodation policies for asylum seekers in metropolitan Athens, Greece. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2021, 29, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourachanis, N. From camps to social integration? Social housing interventions for asylum seekers in Greece. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2019, 39, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakou, I.; Balampanidis, D.; Myofa, N.; Polyzou, I.; Siatitsa, D.; Spyrellis, S.N.; Vakalopoulos, K. Micro-Segregation and Coexistence in Athens: The Debate on Segregation and Its Implications for Urban Research. In Cities. Micro-Segregation, Social Mix and Urban Housing Markets; Maloutas, T., Karadimitiriou, N., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Leontidou, L. The Mediterranean City in Transition: Social Change and Urban Development; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; ISBN 9780521344678. [Google Scholar]

- Maloutas, T.; Karadimitriou, N. Vertical Social Differentiation in Athens: Alternative or Complement to Community Segregation? Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2001, 25, 699–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maloutas, T.; Spyrellis, S.N. Vertical segregation: Mapping the vertical social stratification of residents in Athenian apartment buildings. Méditerranée 2016, 127, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantouvalou, M.; Mavridou, M.; Vaiou, D. Processes of social integration and Urban development in Greece: Southern challenges to European unification. Eur. Plan. Stud. 1995, 3, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloutas, T.; Spyrellis, S.N.; Karadimitriou, N. Measuring and Mapping Vertical Segregation in Athens. In Vertical Cities. Micro-segregation, Social Mix and Urban Housing Markets; Maloutas, T., Karadimitriou, N., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Maloutas, T. The role of vertical segregation in urban social processes. Nat. Cities 2024, 1, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloutas, T.; Karadimitriou, N. Introduction to Vertical Cities: Urban Micro-Segregation, Housing Markets and Social Reproduction. In Vertical Cities. Micro-segregation, Social Mix and Urban Housing Markets; Maloutas, T., Karadimitriou, N., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Veneti, A.; Poulakidakos, S.; Minotakis, A. Rents—ETERON Housing 360°; ETERON: Athens, Greece, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandri, G. Housing financialisation a la Griega. Geoforum 2022, 136, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myofa, N. Social Housing Estates in Athens. In Athens Social Atlas. Digital Compendium of Texts and Visual Material; Maloutas, T., Spyrellis, S., Eds.; Athens Social Atlas: Athens, Greece, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandylis, G.; Maloutas, T.; Myofa, N. Exceptional Social Housing in a Residual Welfare State: Housing Estates in Athens, Greece. In Housing Estates in Europe; Hess, D.B., Tammaru, T., van Ham, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kerpaci, K.; Kuka, M. The Greek Debt Crisis and Albanian Return Migration. J. Balk. Near East. Stud. 2019, 21, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantis, L. Spatial Planing, Institutional Refroms and Globalization. In Policies of International Development during the Post-Socialist Transition in Albania (in Greek); Nissos Academic Publishing: Athens, Greece, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Triantafyllidou, A.; Maroukis, T. Migration in Greece in the 21st Century (in Greek); Kritiki: Athens, Greece, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Labrianidis, L.; Hatziprokopiou, P. The Albanian Migratory Cycle. Migrants Tend to Return to Their Country of Origin after All. In The New Albanian Migration; King, R., Mai, N., Schwandner-Sievers, S., Eds.; Sassex Academic Press: Brighton, UK, 2005; pp. 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- de Rapper, G. Better than Muslims, Not as Good as Greeks. Emigration as Experienced and Imagined by the Albanian Christians of Lunxhëri. In The New Albanian Migration; King, R., Mai, N., Schwandner-Sievers, S., Eds.; Sussex Academic Press: Brighton, UK, 2005; pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Korovilas, J.P. The Albanian Economy in Transition: The Role of Remittances and Pyramid Investment Schemes. Post-Communist Econ. 1999, 11, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EKKE (National Centre for Social Research)—ELSTAT (Hellenic Statistical Authority) Panorama of Greek Census Data 1991–2011. Internet Application to Access and Map Census Data 2015. Available online: https://panorama.statistics.gr/en/ (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Papadopoulos, A.; Fratsea, L.M.; Spyrellis, S.; Baltas, P. Exploring Migrant Labour Contribution in Greek Agriculture Exploring Migrant Labour Contribution in Greek Agriculture. Ital. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2021, 76, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- King, R.; Vullnetari, J. A population on the move: Migration and gender relations in Albania. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2012, 5, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakiolas, R. Regularising undocumented immigrants in Greece: Procedures and effects. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2003, 29, 535–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELSTAT (Hellenic Statistical Authority). The Results of the Census, Population and Residences 2021; Hellenic Statistical Authority: Athens, Greece, 2023. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Mavrommatis, G. Nativism and second-generation migrants in Greece: Differentiating between ethnic and civic elements of citizenship. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2022, 45, 2289–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimis, C.; Papadopoulos, A.G.; Zografakis, S. The Precarious Status of Migrant Labour in Greece: Evidence from Rural Areas. In The New Social Division; Della Porta, D., Hanninen, S., Siisiainen, M., Silvasti, T., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Vaiou, D. In the Interstices of the City: Albanian Women in Athens. Espace Popul. Soc. 2002, 3, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbaci, S. Paradoxes of Segregation; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; ISBN 9781444338324. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP Human Development Report 2011. Sustainability and Equity: A Better Future for All; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, A. Moving Stories: Oral History and Migration Studies. Migration 1999, 27, 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Maloutas, T. The Social Geography of Athens; Alexandria: Athens, Greece, 2018. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Immigrant Housing in Europe: Overview; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Debrunner, G.; Hofer, K.; Wicki, M.; Kauer, F.; Kaufmann, D. Housing Precarity in Six European and North American Cities: Threatened by the Loss of a Safe, Stable, and Affordable Home. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzou, I. Invest the city by doing businesses: Geographies of migrant entrepreneurs in the center of Athens. Greek Rev. Soc. Res. 2020, 153, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadimitriou, N.; Spyrellis, S.N. Measuring Deprivation and Micro-Segregation in Greek ITI SUD: Time to Apply a Common Method? Land 2024, 13, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Mai, N.; Schwandner-Sievers, S. The New Albanian Migration; Sussex Academic Press: Brighton, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gemi, E.; Triantafyllidou, A. Rethinking Migration and Return in Southeastern Europe. In Albanian Mobilities to and from Italy to Greece; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hatziprokopiou, P.A. Globalisation, Migration and Socio-Economic Change in Contemporary Greece: Processes of Social Incorporation of Balkan Immigrants in Thessaloniki; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; ISBN 9789053568736. [Google Scholar]

- Balampanidis, D.; Polyzos, I. Migrants’ settlement in two central neighborhoods of Athens. City 2016, 20, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soureli, K. Housing Affordability, Fair Housing, and Adaptation Strategies by Migrant Residents of Athens in the Early 2010s; University of California: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandri, G.; Janoschka, M. Who Loses and Who Wins in a Housing Crisis? Lessons From Spain and Greece for a Nuanced Understanding of Dispossession. Hous. Policy Debate 2017, 28, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balampanidis, D. Access of Immigrants to Homeownership (2000–2010). Main Patterns of “Horizontal” and “Vertical” Ethnic Residential Segregation in the Municipality of Athens. In Athens Social Atlas. Digital Compendium of Texts and Visual Material; Maloutas, T., Spyrellis, S., Eds.; Athens Social Atlas: Athens, Greece, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMF. IMF Country Report No. 24/24; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bank of Greece. Indices of Residential Property Prices: Q1 2024; Bank of Greece: Athens, Greece, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rousanoglou, N. Properties: More than 5.5 Billion Euros from the Golden Visa Program. Kathimerini Money Rev. 2024. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Bank of Greece. Governor’s Annual Report 2023; Bank of Greece: Athens, Greece, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat Housing in Europe; Interactive Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2023.

| Country of Origin | Population | Part (%) of Total Population | Part (%) of Foreign Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greece | 499,947 | 74.1 | |

| Albania | 66,825 | 10.1 | 39.8 |

| Eastern Europe—EU (Bulgaria, Romania, Poland) | 24,347 | 3.7 | 14.5 |

| Indian peninsula (Bangladesh, Pakistan) | 11,578 | 1.7 | 6.9 |

| Eastern Europe—non-EU (Georgia, Ukraine) | 10,791 | 1.6 | 6.4 |

| Total | 664,046 | 91.8 | 67.7 |

| Country of Origin | 12–15 Year Olds Not in Education | NEET 1 (15–22) | Unemployed | Looking for a Job for the First Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greece | 1.3 | 13.0 | 5.9 | 2.0 |

| Albania | 4.2 | 21.1 | 12.1 | 2.9 |

| Eastern Europe—EU (Bulgaria, Romania, Poland) | 3.2 | 27.8 | 12.1 | 3.1 |

| Indian peninsula (Bangladesh, Pakistan) | 32.1 | 50.0 | 16.9 | 11.2 |

| Eastern Europe—non-EU (Georgia, Ukraine) | 3.2 | 22.8 | 11.1 | 3.1 |

| Total | 1.1 | 13.9 | 7.4 | 2.7 |

| Country of Origin | 0–14 Years Old | More Than 65 Years Old | Males | Average Number of Children per Mother 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greece | 9.9 | 23.7 | 46.2 | 1.1 |

| Albania | 21.3 | 4.0 | 50.6 | 1.5 |

| Eastern Europe—EU (Bulgaria, Romania, Poland) | 14.0 | 1.5 | 41.2 | 0.8 |

| Indian peninsula (Bangladesh, Pakistan) | 4.7 | 0.5 | 92.3 | 0.9 |

| Eastern Europe—non-EU (Georgia, Ukraine) | 7.8 | 2.0 | 28.4 | 0.8 |

| Total | 11.0 | 19.0 | 47.5 | 1.1 |

| Top 5 Occupations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 16–29 Year Olds 1 | 30–50 Year Olds 2 | ||

| Shop salespersons. | 11.4 | Domestic, hotel, and office cleaners and helpers. | 21.3 |

| Waiters and bartenders. | 9.7 | Building frame and related trades workers. | 18.2 |

| Building frame and related trades workers. | 8.9 | Shop salespersons. | 6.0 |

| Domestic, hotel, and office cleaners and helpers. | 7.8 | Building finishers and related trades workers. | 4.9 |

| Building finishers and related trades workers. | 5.9 | Painters, building structure cleaners, and related trades workers. | 3.9 |

| Total | 43.7 | Total | 54.3 |

| Tenure Status by Household | Housing Amenities by Household | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of Origin | Owners | Tenants | No Glazing | No Heating |

| Greece | 67.6 | 25.3 | 48.9 | 2.1 |

| Albania | 25.9 | 72.3 | 69.4 | 8.0 |

| Eastern Europe—EU (Bulgaria, Romania, Poland) | 13.5 | 83.8 | 71.9 | 5.8 |

| Indian peninsula (Bangladesh, Pakistan) | 7.0 | 90.8 | 77.5 | 16.3 |

| Eastern Europe—non-EU (Georgia, Ukraine) | 22.3 | 73.3 | 73.5 | 5.7 |

| Total | 56.0 | 37.7 | 54.4 | 3.5 |

| Country of Origin | Before 1960 | 1960–1980 | After 1980 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greece | 10.8 | 60.4 | 28.7 |

| Albania | 13.0 | 76.5 | 10.5 |

| tenants | 13.9 | 79.9 | 6.3 |

| owners | 9.9 | 67.2 | 22.9 |

| Eastern Europe—EU (Bulgaria, Romania, Poland) | 14.4 | 76.8 | 8.9 |

| Indian peninsula (Bangladesh, Pakistan) | 23.4 | 74.4 | 2.2 |

| Eastern Europe non-EU (Georgia, Ukraine) | 18.0 | 74.6 | 7.4 |

| Total | 12.1 | 64.0 | 23.9 |

| Country of Origin | Lower Floors (Basements and Ground Floors) | Middle Floors (1st to 3rd Floor) | Higher Floors (4th Floor or Higher) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Greece | 8.1 | 61.7 | 31.1 |

| Albania | 22.3 | 63.7 | 14.0 |

| tenants | 24.4 | 62.8 | 12.9 |

| owners | 9.7 | 70.0 | 20.2 |

| Eastern Europe—EU (Bulgaria, Romania, Poland) | 24.8 | 54.7 | 20.5 |

| Indian peninsula (Bangladesh, Pakistan) | 35.8 | 46.4 | 17.8 |

| Eastern Europe—non-EU (Georgia, Ukraine) | 23.7 | 54.3 | 21.9 |

| Total | 14.5 | 60.2 | 25.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polyzou, I.; Spyrellis, S.N. Housing Practices of Albanian Immigrants in Athens: An “in-between” Socio-Spatial Condition. Land 2024, 13, 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13070964

Polyzou I, Spyrellis SN. Housing Practices of Albanian Immigrants in Athens: An “in-between” Socio-Spatial Condition. Land. 2024; 13(7):964. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13070964

Chicago/Turabian StylePolyzou, Iris, and Stavros Nikiforos Spyrellis. 2024. "Housing Practices of Albanian Immigrants in Athens: An “in-between” Socio-Spatial Condition" Land 13, no. 7: 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13070964