Abstract

This study examines attitudes toward achieving a sustainable balance in ecotourism using the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model, focusing on economic and environmental factors shaping sustainable practices. Data were collected from tourists, local residents, and managers in Serbia and Croatia, encompassing diverse perspectives on natural resource conservation, economic benefits, and community engagement. The results indicate that natural resource conservation significantly contributes to local participation, tourist awareness, and community engagement, with notable differences observed among respondent groups. Economic benefits also positively influence these mediating factors, emphasizing their role in achieving sustainability goals. The MGA revealed significant differences between respondent groups, highlighting that managers and local communities in Croatia demonstrated higher levels of awareness and participation compared to Serbia, while differences among tourists were less pronounced. This research contributes to the sustainable tourism literature by integrating perspectives from various stakeholder groups and emphasizing the importance of community involvement and environmental preservation. Practical implications include recommendations for policymakers and managers to develop strategies that encourage stakeholder participation and promote sustainable tourism development.

1. Introduction

Ecotourism is often presented as a key pathway to achieving sustainable tourism, aligning natural resource conservation with economic development. However, as Das and Chatterjee [1] point out, implementing this concept in practice faces significant challenges. Without careful management, the commercialization of ecotourism can undermine ecological goals, highlighting the importance of maintaining a sustainable balance in ecotourism development. This issue is particularly relevant for Serbia and Croatia, where natural resources are central to tourism offerings but are often subject to economic pressures. The inclusion of local communities in ecotourism initiatives has been recognized as critical for achieving sustainable outcomes. Stronza et al. [2] emphasize that communities directly benefiting from ecotourism play a crucial role in biodiversity conservation. Similarly, Cobbinah [3] notes that universal ecotourism models are not always applicable across different contexts, underscoring the need to adapt strategies to local conditions. These insights underline the necessity of considering specific factors that shape community perceptions and participation in sustainable practices, providing a framework for flexible and tailored strategies.

This study aims to bridge the gap by investigating the key determinants influencing the sustainable balance of ecotourism in the Republic of Serbia and the Republic of Croatia. Particular emphasis is placed on economic sustainability, natural resource conservation, community participation, and tourist awareness. By integrating institutional capacities and participatory strategies, the research offers a comparative analysis of ecotourism within two distinct sociocultural and economic contexts. The differing political and economic conditions in EU and non-EU countries provide an intriguing perspective for analyzing ecotourism practices. Croatia, as an EU member state, operates within a structured regulatory framework for sustainability, while Serbia, as a transitional country aspiring to EU membership, faces unique economic and political challenges that hinder the implementation of sustainable practices. While ecotourism research in EU countries is relatively extensive, the dynamics of this concept in non-EU contexts, such as Serbia, remain underexplored.

The findings of this study contribute to global knowledge by offering adaptable sustainable development models that can inform policies and practices in regions facing similar challenges. Moreover, the research enriches the existing literature with empirical insights from transitional economies, advancing both theoretical understanding and practical applications in the field of sustainable tourism.

2. Literature Review

The challenge of achieving a balance between natural resource conservation and economic development occupies a central position in contemporary research on sustainable tourism, with a particular emphasis on the theoretical and practical dimensions of ecotourism. Ulanowicz [4] explores the concept of sustainable balance in ecotourism, defining it as a delicate equilibrium between economic development, natural resource conservation, and active community engagement. This framework serves as a foundation for examining how various interests can be aligned in sustainable tourism practices. However, achieving this balance is often fraught with practical challenges. Takhumova and Ibragimov [5] extend this discussion by highlighting the complex relationship between economic growth and environmental protection. They point out that while both goals are essential for long-term sustainability, their inherent tensions can become obstacles without clearly defined strategies to overcome them. This underscores the importance of strategic planning that goes beyond theoretical frameworks and focuses on practical implementation. Hansen [6] offers a similar perspective, emphasizing that the success of sustainable tourism initiatives depends on integrating ecological, economic, and social dimensions into a unified and coherent approach. His analysis raises important questions about ensuring the equitable distribution of the benefits from ecotourism while preserving natural resources, particularly in the agritourism sector. Ozcan et al. [7] stress that sustainable approaches must simultaneously ensure ecosystem protection and economic benefits. Their research highlights the complexity of such models, where achieving a balance between nature conservation and meeting the economic needs of local communities is imperative.

Patil and Pattanshetti [8] emphasize that the successful development of ecotourism relies on the effective management and active involvement of local communities. While their findings are significant, the question of universal applicability in diverse geographic and cultural contexts arises, which is highly relevant to this study on sustainable balance in Serbia and Croatia. Anup [9] highlights that ecotourism supports the conservation of natural resources and biodiversity while contributing to poverty reduction by creating economic opportunities for local communities. His work underscores ecotourism’s potential to promote social equity through direct employment and support for local initiatives. However, the challenge remains in ensuring the long-term sustainability of these effects and measuring them across various communities. Kiper [10] points to the importance of ecotourism in rural areas, particularly in alleviating poverty caused by depopulation. Nonetheless, balancing economic development with natural resource conservation in such regions remains a critical challenge. Reimer and Walter [11] advocate for a participatory approach in planning and implementing ecotourism practices, especially in rural regions like Cambodia. Their study underscores the necessity of community inclusion while raising concerns about conflicts of interest among stakeholders.

Stone and Nyaupane [12] focus on the role of wildlife and protected areas as primary attractions of ecotourism but stress the need for sustainable management of these resources in the face of growing mass tourism pressures. This perspective aligns with the findings of Khanra et al. [13] whose bibliometric analysis highlights increasing interest in ecotourism as a tool for addressing sustainability challenges. Xu et al. [14] further emphasize the importance of careful resource management and active community participation in achieving long-term sustainable development. Eddyono et al. [15] introduce an innovative model of e-ecotourism, leveraging digital technologies to enhance sustainability and align ecological and economic goals. While this approach underscores the significance of technology in sustainable development, the challenge lies in ensuring technological accessibility in rural destinations and bridging the digital divide.

Kalaitan et al. [16] highlight the potential of ecotourism in post-Soviet states, particularly Ukraine, to stimulate rural development, while Gajić et al. [17] emphasize the integration of cultural and ecological values through biocultural ethics. Although promising, their findings raise questions about aligning these values with the dynamics of local communities and economic pressures. Machnik [18] points to the dual benefits of ecotourism: reducing tourism’s ecological footprint and providing economic advantages for local communities. Similarly, Baloch et al. [19] propose a framework for sustainable ecotourism development that underscores planning but warns of persistent tensions between conservation and commercialization. While theoretically valuable, the framework faces challenges in practical implementation across diverse regions. Fennell and de Grosbois [20] analyze the role of eco-lodges in promoting sustainable practices, emphasizing the importance of transparency in communication with tourists, which builds trust. Salman et al. [21] synthesize the broader impacts of ecotourism, noting that its proper implementation can preserve ecosystems and improve community quality of life. On the other hand, Nigar [22], focusing on Gilgit-Baltistan, illustrates how ecotourism can foster economic growth in resource-rich but underdeveloped areas. Singgalen et al. [23] stress strategic planning that integrates natural resource protection with respect for local communities, showing long-term benefits of proper planning. D’Souza et al. [24] underline the importance of strengthening local community capacities to ensure ecological and social sustainability while addressing challenges in equitable benefit distribution. Thompson et al. [25] explore tensions between ecological and economic goals in Malaysia, highlighting compromises when profitability overshadows conservation. Similarly, Hatma Indra Jaya et al. [26] in Indonesia emphasize the critical role of local communities in sustainable tourism development but warn of systemic barriers such as resource shortages and stakeholder conflicts. Stone [27] points to the significance of partnerships between local communities and external actors but cautions against marginalizing local voices in complex governance systems. Mbaiwa [28] offers a long-term perspective on sustainable ecotourism models in Botswana, demonstrating how community participation can reduce poverty and conserve natural resources, though questions of model applicability across contexts remain. Turobovich et al. [29] stress the importance of marketing in both attracting tourists and raising awareness about nature conservation, while Boley and Green [30] emphasize the responsible use of resources for long-term sustainability. Conversely, Zacarias and Loyola [31] highlight challenges of inadequate regulation, which can lead to negative social and ecological consequences. Gale and Hill [32] complement this discussion by emphasizing the role of destination management in ensuring sustainable benefits for communities. Nasrilloyevich and Suyun o’g’li [33] broaden the scope by analyzing ecotourism’s impact on the overall tourism sector, showcasing its potential for economic diversification and resource protection but questioning the scalability of these effects and conditions for successful implementation.

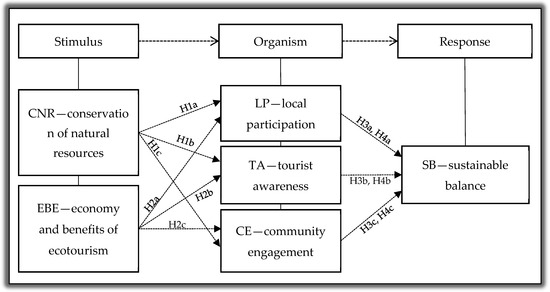

Das and Chatterjee [1] state that Woodworth (1929) proposed the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model as an extension of Pavlov’s (2010) classical stimulus–response theory. This model was originally used to analyze consumer behavior in decision-making but later found broad applications in tourism where it helps us understand how economic and environmental factors shape the perceptions and behaviors of tourists and local communities. In the context of ecotourism, the S-O-R model enables the analysis of the impact of various stimuli, such as sustainable tourism policies and ecological initiatives, on the perceptions and reactions of tourists, managers, and local residents.

The SOR model provides a structured framework for connecting key themes from the literature review, enabling an analysis of the interrelationships between the economic, ecological, and social dimensions of ecotourism. The application of the SOR model (Stimulus-Organism-Response) allows for a deeper understanding of how stimuli, such as economic and ecological factors, shape the perceptions and behaviors of actors (organism) and lead to corresponding responses. The study by Ren et al. [34] emphasizes the role of ecotourism in fostering ecological behaviors among local residents. The authors identify key stimuli, such as ecosystem conservation, which positively influence community perceptions and highlight the importance of responsible behavior as a critical factor for achieving sustainability. Critically, their findings suggest the need for further analysis to better understand how social contexts shape ecological responses, which can be more comprehensively addressed through the SOR model. Based on theoretical insights, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a:

Natural resource conservation positively influences community participation (samples: tourists, local residents, and managers).

H1b:

Natural resource conservation positively contributes to increased tourist awareness (samples: tourists, local residents, and managers).

H1c:

Natural resource conservation significantly impacts community engagement (samples: tourists, local residents, and managers).

Guo [35] investigates the economic benefits of ecotourism from an ecological perspective, identifying both direct and indirect links between nature conservation and economic growth. This study provides evidence on how stimuli, such as investments in natural resource conservation, can generate positive economic impacts. However, it does not sufficiently address the perceptions of local communities and tourists, which are key components within the SOR model.

From a broader theoretical perspective, Riaz et al. [36], through bibliometric analysis, highlight the connection between ecotourism and economic growth, emphasizing the importance of systematically assessing the impacts of ecotourism on sustainability. Their work demonstrates how stimuli, such as nature conservation and social participation, can be integrated with community and tourist perceptions to achieve a sustainable balance. Based on these theoretical considerations, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a:

Economic benefits of ecotourism positively influence community participation (samples: tourists, local residents, and managers).

H2b:

Economic benefits of ecotourism significantly contribute to increased tourist awareness (samples: tourists, local residents, and managers).

H2c:

Economic benefits of ecotourism positively impact community engagement (samples: tourists, local residents, and managers).

Ndhlovu and Dube [37] focus on global research trends and key challenges. Their work provides a context for understanding how social norms and perceptions, as well as internal reactions (organism), shape the sustainable behavior of local communities in practice. While offering valuable insights into the mechanisms of adopting sustainable practices, their analysis also highlights the lack of an integrated understanding of the interaction between economic and ecological dimensions, which is critical for sustainable agritourism development. This contribution further underscores the importance of socio-ecological interactions in shaping sustainable tourism practices. Huang and Wang [38] explore the application of virtual reality (VR) technology in promoting ecotourism and its connection to regional economies and culture. Although their study offers innovative methods to enhance tourist perceptions, it does not fully integrate the social aspects of local communities, which could enrich the analysis through the SOR model. To investigate the mechanisms linking stimuli, such as natural resource conservation (CNR), with sustainable balance (SB), this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H3a:

The impact of natural resource conservation on sustainable balance is mediated by community participation (samples: tourists, local residents, and managers).

H3b:

The impact of natural resource conservation on sustainable balance is mediated by tourist awareness (samples: tourists, local residents, and managers).

H3c:

The impact of natural resource conservation on sustainable balance is mediated by community engagement (samples: tourists, local residents, and managers).

Jiang [39] models influential factors in ecotourism management, considering economic fluctuations and their potential impact on sustainable development. While it provides important insights into the role of forecasting economic factors, the study does not sufficiently address the perceptions and engagement of actors, which are essential elements of response within the SOR model. Conversely, Abuhay et al. [40] focus on the perceptions of local communities in Ethiopia, examining how ecotourism can have dual effects—providing economic benefits and triggering conflicts in resource conservation. Their analysis emphasizes the importance of economic initiatives as stimuli while suggesting that the perceptions of tourists and managers must be integrated to ensure a sustainable balance. Based on these theoretical foundations, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a:

The impact of economic benefits of ecotourism on sustainable balance is mediated by community participation (samples: tourists, local residents, and managers).

H4b:

The impact of economic benefits of ecotourism on sustainable balance is mediated by tourist awareness (samples: tourists, local residents, and managers).

H4c:

The impact of economic benefits of ecotourism on sustainable balance is mediated by community engagement (samples: tourists, local residents, and managers).

Figure 1 represents the theoretical framework of the study, illustrating the application of the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model in the context of ecotourism sustainability. The model outlines how external stimuli, such as natural resource conservation (CNR) and economic benefits of ecotourism (EBE), influence internal perceptions and behaviors (organism) among key stakeholders—local participation (LP), tourist awareness (TA), and community engagement (CE). These intermediary factors then contribute to the overall sustainable balance (SB) between nature conservation and economic development. The diagram visually demonstrates the relationships between these variables and the hypothesized pathways tested in the research.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

3. Methods for This Study

3.1. Questionnaire Design

In this study, we apply the SOR (Stimulus-Organism-Response) model to examine the influence of various factors on the perceptions and behaviors of actors in ecotourism, with a specific focus on Serbia and Croatia. The first component of the model, external stimuli (Stimulus), includes the conservation of natural resources (CNR) and economic benefits of ecotourism (EBE). These factors highlight ecotourism’s contributions to nature conservation, pollution reduction, and the economic development of local communities. This dimension draws upon findings by Oviedo-García et al. [41] who explore the perceived value of ecotourism destinations and its impact on tourist satisfaction, and Das and Chatterjee [1], who analyze how ecotourism contributes to balancing nature conservation with economic development. These factors are further tailored to the specificities of destinations in Serbia and Croatia. Internal reactions (Organism) are reflected through three key constructs: local participation (LP), tourist awareness (TA), and community engagement (CE) [42]. These factors encompass the active involvement of local communities in planning and implementing ecotourism initiatives, raising tourists’ awareness of sustainable practices and their responsibility towards nature and fostering community social engagement. Yu et al. [43] emphasize the crucial role of local communities in achieving sustainable tourism, while Kim, Bonn, and Hall [44] highlight how local residents’ perceptions influence the success of ecotourism initiatives. Similarly, Zhang et al. [45] underscore the importance of educating tourists about sustainable practices, while Phung and Trun [46] point out that tourists’ perceptions of a destination’s value play a key role in shaping their responses and engagement with ecotourism. The ultimate response (Response) is represented by sustainable balance (SB), which measures the achieved balance between natural resource conservation and economic development. This concept is based on the work of Hewei and Youngsook [47], who highlight the necessity of integrating economic and ecological goals, and Dabija et al. [48], who analyze the tensions between development and natural resource protection.

The application of this model provides a comprehensive understanding of the interrelationships among the ecological, economic, and social dimensions of ecotourism, offering guidance for the further development of sustainable practices in Serbia and Croatia (Figure 1). A five-point Likert scale was employed to quantify attitudes (1—strongly disagree, 5—strongly agree), enabling precise data collection. Table 1 provides an overview of the ecotourism-related statements, categorized by respondent groups: local community, tourists, and managers. To facilitate further analysis, each statement is labeled with corresponding abbreviations.

Table 1.

Items and abbreviations.

3.2. Procedure and Sample

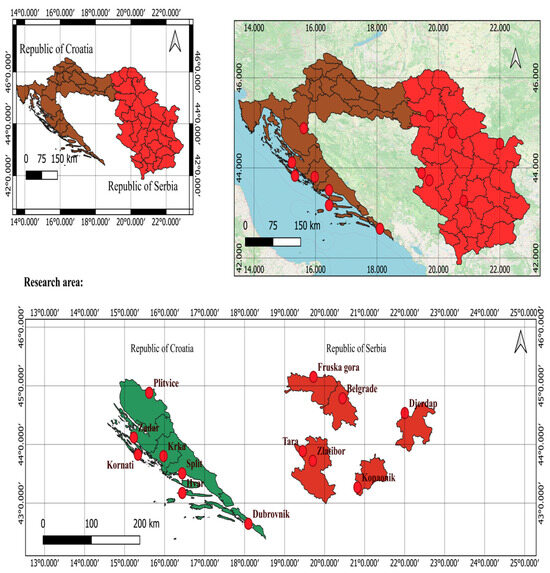

The research was conducted in key tourist destinations of Serbia and Croatia, including Kopaonik, Tara, Zlatibor, Fruška Gora, and the Đerdap National Park in Serbia, as well as Belgrade, Plitvice Lakes National Park, Dubrovnik, Split, Hvar, Zadar, Kornati National Park, and Krka National Park in Croatia (Figure 2). The red dots on the map represent the key ecotourism locations analyzed in the study. These include protected areas, national parks, and significant tourist destinations in both Serbia and Croatia. The distribution of these points highlights the geographical scope of the research, focusing on areas with ecological and economic relevance to sustainable tourism development.

Figure 2.

Research area.

These locations were selected due to their significance for regional tourism and their potential for implementing sustainable tourism practices, with a particular focus on natural resources and cultural heritage. Data were collected from June to August 2024, encompassing a representative sample of tourists, local residents, and managers from the hospitality sector.

Using stratified random sampling ensured adequate representation of key demographic categories, such as age, gender, education, and income. This method allowed for a precise sample distribution, minimizing potential sources of bias and ensuring the validity of the results [49]. The data collection was conducted using the TAPI (Tablet-Assisted Personal Interviewing) method, which ensured high accuracy and efficiency in gathering information directly in the field [50]. Before the main research, the questionnaire was tested on a pilot sample of 50 respondents to ensure the validity and clarity of the questions. The questionnaires were available in Serbian and Croatian, catering to the preferences of the respondents. The total sample size of 1200 respondents exceeded the minimum statistical requirements for reliable analysis, calculated using Cochran’s formula with a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error [51] (Table 2). Stratified sampling further ensured that the sample reflected the demographic characteristics of the population, providing representativeness and reliability in the obtained results [52]. The study was conducted following all ethical guidelines, including voluntary participation, anonymity, and assurances that managers’ responses would not affect their professional evaluations. Particular attention was given to avoiding moral hazard among managers by emphasizing that their responses would not be linked to business or evaluative consequences. This approach ensured a high level of ethical integrity in the study, as well as the validity and reliability of the collected data.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents.

When comparing groups, tourists in Serbia and Croatia exhibited similar demographic structures. However, Croatian tourists had a slightly higher proportion of those with a university education (46.7%) compared to Serbian tourists (51.2%). Local populations in both countries showed similar patterns, with a higher percentage of high-income earners (>€2000) in Croatia (20.3%) compared to Serbia (14.7%). Serbian managers had a significantly higher proportion of men (63.2%) compared to their Croatian counterparts (64.4%), while differences in education and income slightly favored Croatian managers, who had a higher proportion of university-educated individuals and higher income levels (Table 2).

3.3. Data Analysis

The data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 26.00 and SmartPLS version 3.0. Initial descriptive statistics included means (M) and standard deviations (SD) for all items, while data normality was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (p > 0.05) [53]. Scale reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, with the scales showing satisfactory values: 0.888 for the Serbian sample and 0.908 for the Croatian sample. The normality of the data distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, which showed p > 0.05 for all factors, indicating satisfactory normality of the distribution [54]. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.85 for Serbia and 0.876 for Croatia, indicating high adequacy of the sample for factor analysis [55]. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant for both samples (Serbia: χ2 (120) = 745.65, p < 0.001; Croatia: χ2 (136) = 819.24, p < 0.001), confirming the suitability of using factor analysis. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to assess latent constructs, with the factors explaining a significant percentage of variance in both samples. The values of composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) demonstrated high reliability and convergent validity [56]. CR values exceeded 0.7, indicating good internal consistency for all factors, while AVE values surpassed 0.5, confirming that the explained variance was greater than the error variance, which indicates convergent validity of the constructs in both samples. Multi-group analysis (MGA) was conducted to process the data and identify differences in responses among the respondent groups—tourists, local communities, and managers—in Serbia and Croatia. The parameters obtained were utilized within the PLS-SEM framework and were also used for path analysis and the examination of the relationships between key constructs in the model [56].

3.4. Measurement Model

The results indicate high reliability and satisfactory convergent validity for all constructs in the study. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and composite reliability (CR) values were generally high, confirming strong internal consistency. For the Serbian sample, alpha coefficients ranged from 0.870 to 0.892 (Cronbach’s α = 0.888; CR = 0.903), with CR values exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.7. Similarly, for the Croatian sample, slightly higher alpha coefficients were observed, ranging from 0.880 to 0.908 (Cronbach’s α = 0.908; CR = 0.915). The average variance extracted (AVE) exceeded the threshold of 0.5 for most constructs, confirming good convergent validity. For the Serbian sample, the average AVE values were 0.643 (AVE = 0.643), while for Croatia, they were 0.658 (AVE = 0.658). Minor differences were observed in rho_A values, where constructs in the Croatian sample showed slightly lower values (rho_A Serbia = 0.854; rho_A Croatia = 0.841), potentially indicating weaker structural validity among the local population. Results from the HTMT (Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio) analysis showed acceptable values, indicating satisfactory discriminant validity between constructs. Most construct pairs had values below the recommended threshold of 0.85 [57] (HTMT Serbia = 0.742; HTMT Croatia = 0.769), confirming that constructs were not overly correlated and measured distinct concepts. Differences between the Serbian and Croatian groups suggest specific patterns of ecotourism perceptions among local residents, tourists, and managers. The reported VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) values indicated satisfactory control of multicollinearity within the model across all analyzed groups, including local residents, tourists, and managers in Serbia and Croatia. All VIF values were below the threshold of 5 [58] (VIF Serbia = 3.45; VIF Croatia = 3.32), confirming the absence of significant interdependence issues among predictors. Model fit indicators demonstrated satisfactory values across all groups, with metrics indicating adequate model adjustment and high validity. Standardized errors and fit indices confirmed alignment between the model and the data for both the Serbian and Croatian samples.

4. Results

4.1. Results of Descriptive, EFA, and Correlation Analysis

Table 3 presents the descriptive values for the statements within different factors, comparing the samples from Serbia and Croatia. The arithmetic means (m), standard deviations (sd), Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (α), and factor loadings (λ) for each statement are shown. Differences in mean values indicate varying perceptions between the two samples, revealing how local residents, tourists, and managers assess the economic, ecological, and social impact of ecotourism. The results show that respondents from Croatia, on average, provide slightly lower ratings on economic and ecological benefits, with greater variation in responses (sd). On the other hand, the sample from Serbia shows greater consistency and slightly higher mean scores in categories such as community participation and sustainable balance. Cronbach’s alpha values, ranging from 0.865 to 0.898, indicate good internal consistency within the factors for both samples, while the factor loadings (λ) demonstrate the strength of the relationship between each statement and its corresponding factor.

Table 3.

Reliability and convergent validity test.

The results show a high level of reliability in both samples, with Cronbach’s alpha values exceeding 0.87 for all factors, indicating high internal consistency of the statements within each factor (Table 4). Composite reliability (CR) values are above 0.89, further confirming the reliability of the factors. AVE values are above 0.65 for all factors, indicating good convergent validity, as more than 50% of the factor variance is explained by the statements themselves. Differences between the samples from Serbia and Croatia are noticeable in the perception of various aspects of ecotourism. In the Croatian sample, mean values (m) for factors such as economic benefits and natural resource conservation are generally higher compared to the Serbian sample, while standard deviations (sd) show greater variation in responses, suggesting a wider range of opinions and perceptions among respondents in Croatia. On the other hand, the Serbian sample exhibits greater response stability, with lower sd values and slightly higher ratings for factors such as local participation and sustainable balance. The cumulative percentages of variance indicate how much explained variance each factor contributed to the overall model, with the factors of economic benefits of ecotourism and natural resource conservation having the largest share in both samples, highlighting their key role in the perception of ecotourism.

Table 4.

Reliability and convergent validity test for the factors.

Table 5 shows the correlations among constructs, indicating that the square roots of the AVE values (displayed on the diagonal) exceed all inter-construct correlations, confirming satisfactory discriminant validity. For the EBE construct, the square root of the AVE is 0.852, which is higher than all its correlations with other constructs (the highest being with CNR, 0.610). The inter-construct correlations are within acceptable limits, indicating that the constructs measure different aspects of the phenomenon. The strongest inter-construct correlation was observed between LP and SB (0.645), suggesting a strong connection between local community participation and sustainable balance. The weakest correlation was between EBE and CE (0.450), indicating a lower level of association between the economic benefits of ecotourism and community engagement. These results further confirm that each construct measures a specific concept without overlap among constructs.

Table 5.

Correlations among variables.

4.2. Results of SEM Analysis

The results of the model fit statistics indicate satisfactory values for the samples from Serbia and Croatia. The χ2/df values are close to the optimal range, with 1.875 for Serbia and 1.914 for Croatia, suggesting an adequate model fit to the data. The RMSEA values are identical for both samples (0.06), further confirming good model fit [59]. Fit indices such as CFI and NFI demonstrate a high level of model-data alignment [60]. For the Serbian sample, the CFI is 0.94, while for Croatia, it is slightly lower at 0.93. A similar trend is observed with NFI values, which are 0.993 for Serbia and 0.992 for Croatia. The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) remains within acceptable limits, with values of 0.087 for Serbia and 0.080 for Croatia [61]. The coefficients of determination (R2) show that the model explains a significant proportion of the variance in dependent constructs in both countries [59]. For local residents, R2 is 0.512 in Serbia and 0.541 in Croatia, while the values for tourists are 0.579 in Serbia and 0.608 in Croatia. Managers have the highest R2 values, with 0.685 in Serbia and 0.639 in Croatia (Table 6).

Table 6.

Results of the models’ goodness of fit statistics.

Table 7 presents the key metrics for assessing the structural model, including explained variance (R2), predictive relevance (Q2), effect size (f2), as well as the direct, indirect, and total effects on the dependent variable SB for the three respondent groups. The results confirm the significance and predictive power of the model in explaining SB, providing insights into the contributions of the independent constructs [60].

Table 7.

Analysis of effects and explained variance for SB (sustainable balance).

The analysis results confirm significant relationships between the key constructs in the model, supporting all proposed hypotheses. Direct effects show that natural resources (CNR) positively influence local participation (LP), tourist awareness (TA), and community engagement (CE) across all respondent groups (H1a, H1b, H1c). Managers in Serbia stand out, with the strongest effect observed for CNR → CE (β = 0.692, t = 9.231, p < 0.001). In Croatia, the impact on TA is more pronounced among tourists, reflecting successfully implemented conservation and education policies (H1b: β = 0.686, t = 6.098, p < 0.001). Similarly, the economic benefits of ecotourism (EBE) have a significant direct impact on all mediating constructs (LP, TA, and CE) for all respondent groups (H2a, H2b, H2c). Among local residents in Serbia, EBE → LP shows β = 0.431 (t = 9.587, p = 0.003), while in Croatia, the impact on CE is particularly strong for managers (H2c: β = 0.580, t = 10.320, p < 0.001). Indirect effects further confirm the mediating role of LP, TA, and CE in transmitting the influence of CNR and EBE on sustainable balance (SB). For instance, the indirect effects CNR → LP → SB show β = 0.287 for tourists in Serbia (t = 9.102, p < 0.001) and β = 0.341 for tourists in Croatia (t = 8.013, p < 0.001), supporting H3a. Similarly, the effects EBE → TA → SB highlight the importance of tourist education in Croatia, where β = 0.400 (t = 9.450, p < 0.001), confirming H4b. The strongest indirect effect was identified among managers in Serbia, where EBE → CE → SB has β = 0.350 (t = 9.500, p < 0.001), with a similar pattern observed among tourists in Croatia (H4c: β = 0.410, t = 9.300, p < 0.001). These results underscore the critical role of collective engagement in achieving sustainable tourism practices. The findings also reveal regional differences between Serbia and Croatia. While local participation and community contribution dominate in Serbia (CNR → LP, EBE → CE), tourist awareness and education are emphasized in Croatia (CNR → TA, EBE → TA) (Table 8).

Table 8.

Path analysis and hypothesis testing.

After conducting the path analysis, which was used to examine the detailed relationships between constructs and validate the proposed hypotheses, a concise version of the multi-group analysis (MGA) was performed (Table 9). The MGA provided a comparative perspective, allowing for a deeper understanding of variations in perceptions and contextual factors influencing sustainable ecotourism practices. Specifically, the multi-group analysis (MGA) was conducted to investigate and compare differences in path coefficients and effect sizes among the respondent groups: tourists, local communities, and managers, in Serbia (SRB) and Croatia (CRO). Before the analysis, all necessary conditions, including measurement invariance, were satisfied, ensuring the comparability of constructs across groups. The results suggest that the development of sustainable ecotourism is strongly influenced by institutional frameworks, economic priorities, and the level of awareness among tourists and local stakeholders. The most significant differences were observed among managers, where the effects of sustainable practices were more pronounced in Croatia (β = 0.480) compared to Serbia (β = 0.420), indicating a stronger institutional framework and better integration within the EU context. Among local communities, notable differences were also evident (CRO: β = 0.410, SRB: β = 0.360), suggesting that local actor participation in Croatia is better structured and supported. For tourists, although the differences in coefficients were less pronounced (CRO: β = 0.440, SRB: β = 0.400), the analysis indicates higher awareness and engagement among tourists in Croatia. The statistical significance of these differences was confirmed by Δt and Δp values, which highlighted significant variations between groups, particularly for local communities and managers. These findings underscore the importance of local specificities in developing sustainable tourism strategies. Furthermore, the effect sizes (f2) and the predictive relevance of the model (Q2) confirm the validity of the model in both countries, with slightly higher values in Croatia, indicating better predictive strength and integration of sustainable practices.

Table 9.

Multi-group analysis of path coefficients and effect sizes for SRB and CRO.

5. Discussion

The comparative analysis of ecotourism in Serbia and Croatia provides significant insights into different approaches to sustainable tourism, considering the specific political, cultural, and geographical characteristics of each country [4,5,62,63,64,65]. The results of this research indicate notable differences in the perception of ecotourism by tourists, local residents, and managers in Serbia and Croatia. In Serbia, where ecotourism is still developing, respondents demonstrated high awareness of the importance of natural resource conservation. These findings align with Han et al. [66] who emphasize the importance of responsible visitor decision-making within the norm activation process. Additionally, Gössling et al. [67] highlight changes in consumer behavior driven by climate change, underscoring the significance of environmental awareness in fostering responsible tourist behavior. The results of this study confirm that ecological awareness contributes to the sustainability of tourist destinations by positively shaping visitor behavior. The importance of local community participation in ecotourism initiatives is particularly evident in Croatia, where local communities actively participate in the planning and implementation of tourism activities. These findings align with previous research emphasizing the role of community-based approaches in strengthening ecotourism sustainability [19,26,29]. Chan et al. [68] point out that such participation enhances responsible tourism practices, while Waluyo et al. [69] further emphasize the harmonization of economic, cultural, and ecological goals as the key to the long-term success of ecotourism. The findings of this study indicate that natural resource conservation is essential for achieving sustainable balance, consistent with the findings of Sobhani et al. [70] who highlight the importance of active local community involvement in the sustainable development of protected areas. Specific local circumstances in Serbia and Croatia play a crucial role in shaping sustainable ecotourism practices. In Croatia, institutional support and a long-term strategy for ecotourism development have resulted in a higher level of awareness and engagement of the local population in ecological initiatives. On the other hand, in Serbia, ecotourism is still developing, with key challenges related to aligning national policies with international standards and strengthening the participation of local stakeholders. These insights highlight the need for tailored strategies that consider the socio-economic and institutional differences between the two countries. Similar conclusions are drawn by Lasso and Dahles [71] who emphasize the importance of a local approach in ecotourism development, as exemplified by Komodo National Park. Ecotourism has proven to be a platform for developing sustainable practices through the integration of local knowledge and education. By incorporating traditional ecological knowledge, community-driven tourism initiatives enhance both environmental conservation and socio-economic benefits. Education plays a crucial role in equipping local communities with the necessary skills to manage ecotourism operations effectively, ensuring long-term sustainability. Furthermore, participatory approaches enable knowledge-sharing between tourists and host communities, fostering mutual understanding and reinforcing sustainable tourism behaviors. These findings align with previous research emphasizing the importance of local knowledge, community participation, and education in achieving ecotourism sustainability [10,11,26,30,31]. Tauro et al. [72] identify biocultural ethics as a key element in education for sustainable development, while Zainal et al. [73] stress the importance of local knowledge in protecting natural resources and ensuring sustainable community development. Additionally, Imppola [74] and Khan [75] point out the opportunities and challenges globalization brings to ecotourism, particularly in balancing economic benefits with natural resource conservation. Our findings further confirm the necessity of this balance, as respondents recognize and value both the conservation of nature and the economic benefits of ecotourism [76,77,78,79,80]. In the context of environmentally sustainable growth, it is important to consider the existing policies and values of sustainable development in the tourism sector of Serbia and Croatia. Croatia, as an EU member state, already implements regulations that promote ecological sustainability, while Serbia, as a transitional country, is still developing its policies in accordance with international standards. The adoption of effective sustainable development strategies and the implementation of European Union guidelines could contribute to accelerating the adaptation process of ecotourism in Serbia. Further research could focus on specific regulatory barriers and opportunities for improving sustainable tourism practices in the region.

This study underscores the critical role of institutional frameworks in the successful implementation of sustainable practices, making a significant contribution to the global understanding of the importance of policy and governance in ecotourism. The findings are relevant for academics focused on sustainable development and tourism, as well as researchers exploring institutional and participatory models. Moreover, the results are applicable to other regions with transitional economies and industries dependent on sustainable practices, such as agriculture and hospitality. This work is significant as it enhances understanding of sustainable development in regions facing unique challenges, offering clear guidelines for practical application in diverse contexts. Additionally, the study provides practical and theoretical insights useful for educational programs and research projects, making it a valuable resource for the academic community, practitioners, and policymakers.

6. Concluding Remarks on Implications and Directions for Future Research

Although ecotourism is at different stages of development in the countries analyzed, the results indicate similar challenges in achieving a balance between economic growth and environmental protection. The application of the SOR model enabled a systematic analysis of factors influencing sustainability in ecotourism. This model integrates ecological, economic, and social dimensions, providing a comprehensive framework for interpreting the findings. The results confirm that stimuli, such as natural resource conservation and economic benefits, significantly shape stakeholder perceptions, while local participation and community engagement play a crucial role in achieving sustainable balance. While both countries acknowledge the importance of natural resource conservation, respondents in Serbia emphasized the role of ecotourism in preserving biodiversity, whereas in Croatia, the economic benefits of ecotourism were more strongly perceived. These findings suggest that while the overarching principles of sustainability are shared, the relative importance of different factors varies based on institutional and economic contexts. In Serbia, ecotourism is increasingly recognized as a means of preserving natural resources, while in Croatia, it serves as a key driver of economic benefits for local communities. Active participation of local stakeholders in the planning and implementation of ecotourism activities has proven essential for long-term sustainability. Meanwhile, tourists in both countries have shown growing awareness of ecological practices, highlighting the need for further education and promotion of sustainable practices. This comparative analysis provides valuable guidelines for improving ecotourism, particularly by adapting sustainable strategies to local contexts. The results of this study not only highlight the differences in the perception of sustainable ecotourism between Serbia and Croatia but also identify concrete opportunities for improving practices in both countries. The implementation of policies that promote local community involvement and tourist education can contribute to the sustainable development of ecotourism. The study’s findings can serve as a foundation for decision-making in the tourism sector, pointing to specific strategies that could enhance environmental awareness and the economic benefits of ecotourism.

This research emphasizes the importance of tailoring ecotourism strategies to the specific institutional frameworks of EU and non-EU countries. The observed differences between Serbia, a country in transition, and Croatia, an EU member, underscore the significance of institutional support in shaping sustainable practices. Croatia benefits from European policies that integrate ecotourism, whereas Serbia faces challenges in aligning with international standards, pointing to the need for further research on the role of institutions in non-EU countries. The participation of local communities and tourists’ perceptions of sustainable practices further enrich the theory of sustainable tourism development, particularly regarding economic benefits and resource conservation. The findings open pathways for future theoretical developments on the role of innovation and digitalization in enhancing ecotourism in transitional countries. Further investigation should focus on how digital tools can enhance stakeholder engagement, improve visitor experiences, and support real-time environmental monitoring, particularly in countries undergoing policy transitions toward sustainability. This study underscores the need for new theoretical models that consider specific institutional capacities, focusing on how non-EU countries can align ecotourism practices with global sustainability standards, addressing gaps in this area. The use of the SOR model in this research contributes to theory by integrating ecological, economic, and social dimensions into the analysis of sustainable practices. The model identifies key factors and their interrelationships, providing a theoretical framework applicable to various destinations and industries.

The findings provide actionable guidelines for the development of ecotourism in countries with varying institutional capacities, such as Serbia and Croatia. For Serbia, the results highlight the need to strengthen institutional support and implement sustainable development policies. Ecotourism can serve as a tool for preserving natural resources and fostering economic growth in local communities. Croatia, already benefiting from European policies, can further enhance its ecotourism practices by focusing on innovation and digitalization to improve the efficiency and sustainability of tourism activities. It is crucial to continue fostering local community participation in planning and implementing ecotourism initiatives, as the results show that local residents play a pivotal role in long-term sustainability. For policymakers and tourism managers, the study offers practical recommendations on involving local stakeholders in tourism projects, ensuring the equitable distribution of economic benefits and the preservation of natural resources. Additionally, the findings underline the importance of continuously educating tourists on sustainable practices, which could mitigate the negative environmental impacts of tourism. Implementing awareness programs for tourists about ecological practices should be a priority in both countries. The practical implications also include the necessity of investing in innovation and digital tools, especially in Serbia, where technology implementation could accelerate the development of sustainable ecotourism and increase global competitiveness.

Future research should examine the adaptability of ecotourism models to different regulatory environments, comparing how institutional structures influence policy implementation and stakeholder engagement. Additionally, longitudinal studies assessing the long-term impact of sustainability initiatives on local economies and ecosystems would provide deeper insights into the effectiveness of current approaches. Moreover, further studies could investigate the impact of digital technologies and innovations on improving sustainable practices, particularly in developing countries like Serbia. Researching the perceptions of tourists and local communities toward new technologies and their contributions to ecotourism could provide valuable insights for future development strategies.

Limitations

The study has several important limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The sample of respondents was restricted to specific tourist destinations in Serbia and Croatia, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader regions with varying ecotourism characteristics. Although key destinations were included, a wider geographical scope could provide deeper insights into the diversity of ecotourism practices in each country.

One significant limitation relates to the institutional and legal frameworks governing ecotourism. Croatia, as an EU member state, benefits from alignment with European regulations and policies on environmental protection and sustainable tourism. In contrast, Serbia faces challenges in developing and implementing legislation in ecotourism. Serbia’s underdeveloped institutional framework may hinder the adoption of ecotourism standards and policies that align with international environmental norms, posing a significant barrier to the sustainable development of ecotourism. Additionally, the study relies on subjective assessments by respondents regarding sustainable practices, which may introduce potential biases and variability in their knowledge of ecotourism. This limitation is particularly relevant for Serbia, where awareness of ecotourism and ecological practices is less developed compared to Croatia, potentially affecting differing perceptions and interpretations of ecotourism practices. While the results highlight the importance of digitalization and innovation for the sustainability of ecotourism, the study did not deeply investigate specific technological tools and strategies that could enhance ecotourism practices. This is especially relevant in Serbia, where technology could play a pivotal role in accelerating the development of ecotourism offerings. Further research is required to better understand the role of innovation in advancing ecotourism.

Although the SOR model provided a valuable framework for analysis, its application was limited to specific ecotourism factors in Serbia and Croatia. Future research could expand the model to include additional dimensions, such as technological innovations or cultural differences, to capture more complex aspects of sustainability. Longitudinal studies could also provide deeper insights into the long-term effects of the factors identified in this research. Applying the model to other regions or industries would allow further testing of its adaptability and validity.

The findings of this study hold significant value for researchers focused on sustainable tourism, policymakers involved in legislative development, and managers in the tourism sector. This study offers concrete recommendations for improving practices across different regions and industries, contributing to the broader understanding of sustainable tourism development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.G. and D.V.; methodology, M.D.P.; software, I.B.; validation, A.S., J.B. and M.B.; formal analysis, T.G.; investigation, M.D.P.; resources, I.B.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G. and I.B.; writing—review and editing, D.V.; visualization, A.S. and M.M.; supervision, B.D.D. and T.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Contract No. 451-03-66/2024-03/200172), and by the RUDN University (Grant no. 060509-0-000).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Das, M.; Chatterjee, B. Ecotourism: A Panacea or a Predicament? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 14, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronza, A.L.; Hunt, C.A.; Fitzgerald, L.A. Ecotourism for Conservation? Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2019, 44, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbinah, P.B. Contextualising the Meaning of Ecotourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 16, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulanowicz, R.E. Quantifying Sustainable Balance in Ecosystem Configurations. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takhumova, O.V.; Ibragimov, A.G. Cyclic-Genetic Approach to the Formation of Theories of Sustainable Balanced Development of Agricultural Production. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 723, 032008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.G.; Schaltegger, S. The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard: A Systematic Review of Architectures. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, B.; Danish; Bozoklu, S. Dynamics of Ecological Balance in OECD Countries: Sustainable or Unsustainable? Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Pattanshetti, M. The Role of Ecotourism in Sustainable Development: A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Sustainability 2024, 12, 4843585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anup, K.C. Ecotourism in Nepal. The Gaze J. Tour. Hosp. 2017, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiper, T. Role of Ecotourism in Sustainable Development. Adv. Landsc. Archit. 2014, 773–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, J.K.; Walter, P. How Do You Know It When You See It? Community-Based Ecotourism in the Cardamom Mountains of Southwestern Cambodia. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.T.; Nyaupane, G.P. Protected areas, wildlife-based community tourism and community livelihoods dynamics: Spiraling up and down of community capitals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 26, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanra, S.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Mäntymäki, M. Bibliometric Analysis and Literature Review of Ecotourism: Toward Sustainable Development. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Ao, C.; Liu, B.; Cai, Z. Ecotourism and Sustainable Development: A Scientometric Review of Global Research Trends. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 2977–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddyono, F.; Darusman, D.; Sumarwan, U.; Sunarminto, F. Optimization model: The innovation and future of e-ecotourism for sustainability. J. Tour. Futures. [CrossRef]

- Kalaitan, T.V.; Stybel, V.V.; Gutyj, B.V.; Hrymak, O.Y.; Kushnir, L.P.; Yaroshevych, N.B.; Kindrat, O.V. Ecotourism and Sustainable Development: Prospects for Ukraine. Ukr. J. Ecol. 2021, 11, 373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Gajić, T.; Blešić, I.; Petrović, M.D.; Radovanović, M.M.; Ðoković, F.; Demirović Bajrami, D.; Kovačić, S.; Jošanov Vrgović, I.; Tretyakova, T.N.; Syromiatnikova, J.A. Stereotypes and Prejudices as (Non) Attractors for Willingness to Revisit Tourist-Spatial Hotspots in Serbia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machnik, A. Ecotourism as a Core of Sustainability in Tourism. In Handbook of Sustainable Development and Leisure Services; Lubowiecki-Vikuk, A., de Sousa, B.M.B., Đerčan, B.M., Leal Filho, W., Eds.; World Sustainability Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Q.B.; Shah, S.N.; Iqbal, N.; Sheeraz, M.; Asadullah, M.; Mahar, S.; Khan, A.U. Impact of Tourism Development Upon Environmental Sustainability: A Suggested Framework for Sustainable Ecotourism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 5917–5930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fennell, D.A.; de Grosbois, D. Communicating sustainability and ecotourism principles by ecolodges: A global analysis. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 48, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.; Jaafar, M.; Mohamad, D.; Khoshkam, M. Understanding multi-stakeholder complexity & developing a causal recipe (fsQCA) for achieving sustainable ecotourism. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 10261–10284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigar, N. Ecotourism for sustainable development in Gilgit-Baltistan: Prospects under CPEC. Strateg. Stud. 2019, 38, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singgalen, Y.A.; Sasongko, G.; Wiloso, P.G. Efforts to Achieve Environmental Sustainability through Ecotourism. J. Indones. Tour. Dev. Stud. 2019, 7, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Taghian, M.; Marjoribanks, T.; Sullivan-Mort, G.; Manirujjaman, M.D.; Singaraju, S. Sustainability for Ecotourism: Work Identity and Role of Community Capacity Building. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.S.; Gillen, J.; Friess, D.A. Challenging the Principles of Ecotourism: Insights from Entrepreneurs on Environmental and Economic Sustainability in Langkawi, Malaysia. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatma Indra Jaya, P.; Izudin, A.; Aditya, R. The Role of Ecotourism in Developing Local Communities in Indonesia. J. Ecotourism 2024, 23, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.T. Community-Based Ecotourism: A Collaborative Partnerships Perspective. J. Ecotourism 2015, 14, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaiwa, J.E. Ecotourism in Botswana: 30 years later. J. Ecotourism 2015, 14, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turobovich, J.A.; Uktamovna, M.N.; Turobovna, J.Z. Marketing Aspects of Ecotourism Development. Economics 2020, 1, 25–27. Available online: https://uniwork.buxdu.uz/resurs/13729_1_A52A60E892CD9D0E1631B4BF12774104AE7C043B.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Boley, B.B.; Green, G.T. Ecotourism and Natural Resource Conservation: The ‘Potential’ for a Sustainable Symbiotic Relationship. J. Ecotourism 2016, 15, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacarias, D.; Loyola, R. How Ecotourism Affects Human Communities. In Ecotourism’s Promise and Peril; Blumstein, D., Geffroy, B., Samia, D., Bessa, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, T. Ecotourism and Environmental Sustainability: Principles and Practice; Hill, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrilloyevich, A.S.; Suyuno'g'li, C.A. Harnessing the Power of Nature: The Role of Sangardak Waterfall in the Development of Domestic Tourism. Multidiscip. J. Technol. Sci. 2024, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Dang, P. Can ecotourism contribute to ecosystems? Evidence from local residents’ ecological behaviors. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P. Contributors to Economic Benefits of Tourism from the Perspective of Ecological Factors. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2023, 22, 1595–1605. Available online: http://www.eemj.icpm.tuiasi.ro/pdfs/vol22/no9/11_184_Guo_23.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Riaz, A.; Raza, H.; Gharleghi, B.; Riaz, N. Ecotourism and Economic Growth: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Literature Review. In Supporting Environmental Stability Through Ecotourism; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA; New York, NY, USA; Beijing, China, 2024; pp. 24–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ndhlovu, E.; Dube, K. Agritourism and sustainability: A global bibliometric analysis of the state of research and dominant issues. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 46, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Wang, Z. The application of virtual reality technology in the coordination and interaction of regional economy and culture in the sustainable development of ecotourism. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 9847749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X. Research on New Ecotourism Management Impact Factor Modeling Based on Economic Fluctuation Prediction. Tour. Manag. Technol. Econ. 2023, 6, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhay, T.; Teshome, E.; Mulu, G. A Tale of Duality: Community Perceptions Towards the Ecotourism Impacts on Simien Mountains National Park, Ethiopia. Reg. Sustain. 2023, 4, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-García, M.Á.; Castellanos-Verdugo, M.; Vega-Vázquez, M.; Orgaz-Agüera, F. The mediating roles of the overall perceived value of the ecotourism site and attitudes towards ecotourism in sustainability through the key relationship ecotourism knowledge-ecotourist satisfaction. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 19, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saewanee, C.; Napalai, J.; Jaroenwanit, P. Factors affecting customer retention of e-marketplace industries through Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model and mediating effect. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2024, 12, 1537–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, Q.; Chu, D.D.; Chen, T.; Chen, X. Consumer behavior based on the SOR model: How do short video advertisements affect furniture consumers’ purchase intentions? BioResources 2024, 19, 2639–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Bonn, M.; Hall, C.M. What Drives the Adoption of Sustainable Tourism Practices? The effect of digital storytelling on unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 34, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.-L.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, S. Predicting residents’ pro-environmental behaviors at tourist sites: The role of awareness of disaster’s consequences, values, and place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, T.B.; Tran, C.M. The study of consumers’ post-purchasing behavioural intentions towards organic foods in an emerging economy: From the SOR model perspective. Int. J. Serv. Econ. Manag. 2024, 15, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewei, T.; Youngsook, L. Factors affecting continuous purchase intention of fashion products on social e-commerce: SOR model and the mediating effect. Entertain. Comput. 2022, 41, 100474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabija, D.C.; Csorba, L.M.; Isac, F.L.; Rusu, S. Managing sustainable sharing economy platforms: A stimulus–organism–response based structural equation modelling on an emerging market. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; You, H.; Yan, M.; Wang, L. Stratified random sampling for neural network test input selection. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2024, 165, 107331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, T.; Gadár, L. Survey Data on the Attitudes Towards Digital Technologies and the Way of Managing E-Governmental Tasks. Data Brief 2023, 46, 108871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanjundeswaraswamy, T.S.; Divakara, S. Determination of Sample Size and Sampling Methods in Applied Research. Proc. Eng. Sci. 2021, 3, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Bun, M.; Gaboardi, M.; Kolaczyk, E.D.; Smith, A. Differentially private confidence intervals for proportions under stratified random sampling. Electron. J. Stat. 2024, 18, 1455–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 6th ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. An Index of Factorial Simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An Assessment of the Use of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing Research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyshev, K.A.; Alov, I.N.; Li, Y.; Gajić, T. How Real Is Migration’s Contribution to the Population Change in Major Urban Agglomerations? J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2023, 73, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziekański, P.; Popławski, Ł.; Popławska, J. Interaction Between Pro-Environmental Spending and Environmental Conditions and Development. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2024, 74, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujadinović, S.; Šabić, D.; Gajić, M.; Golić, R.; Kazmina, L.; Joksimović, M.; Sedlak, M. Tourism in the Context of Contemporary Theories of Regional Development. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2023, 73, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong Huy, H.; Thi Ngoc Thi, L.; Tri Nam Khang, N.; Thi Tu Trinh, N. Estimating the Economic Value of the Ecotourism Destination: The Case of Tra Su Melaleuca Forest Natural Park in Viet Nam. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2023, 73, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, S.; Hwang, J. Cruise Travelers’ Environmentally Responsible Decision-Making: An Integrative Framework of Goal-Directed Behavior and Norm Activation Process. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 53, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M.; Ceron, J.P.; Dubois, G. Consumer Behaviour and Demand Response of Tourists to Climate Change. Ann. Tour. Res. 2022, 39, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; Marzuki, K.M.; Mohtar, T. Local Community Participation and Responsible Tourism Practices in Ecotourism Destination: A Case of Lower Kinabatangan, Sabah. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waluyo, E.B.; Baroto, E.; Guritno, B. Harmonizing Ecotourism in Indonesia: Balancing the Green Economy, Cultural Heritage, and Biodiversity. Int. Conf. Digit. Adv. Tour. Manag. Technol. 2023, 1, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, P.; Esmaeilzadeh, H.; Sadeghi, S.M.M.; Wolf, I.D.; Deljouei, A. Relationship Analysis of Local Community Participation in Sustainable Ecotourism Development in Protected Areas, Iran. Land 2022, 11, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasso, A.H.; Dahles, H. A community perspective on local ecotourism development: Lessons from Komodo National Park. Tour. Geogr. 2021, 25, 634–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauro, A.; Ojeda, J.; Caviness, T.; Moses, K.P.; Moreno-Terrazas, R.; Wright, T.; Zhu, D.; Poole, A.K.; Massardo, F.; Rozzi, R. Field environmental philosophy: A biocultural ethic approach to education and ecotourism for sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, S.; Nirzalin; Fakhrurrazi; Yunanda, R.; Ilham, I.; Badaruddin. Actualizing Local Knowledge for Sustainable Ecotourism Development in a Protected Forest Area: Insights from the Gayonese in Aceh Tengah, Indonesia. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2302212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imppola, J.J. Global Economy and Its Sustainability in the Globalized World. SHS Web Conf. 2020, 74, 04008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.A. Globalization and Sustainability. In Globalization and The Challenges of Public Administration; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, B.; Pegi, A.L.; Suripto; Syolendra, D.F.; Fajri, H. Environmental Sustainability through Sendang Sombomerti Ecotourism Management. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 506, 05001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seervi, P. Ecotourism and Sustainable Development. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2023, 5, 7049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornburg, J. Eco-tourism and Sustainable Community Development in Cuba: Bringing Community Back into Development. J. Int. Glob. Stud. 2017, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgonja, J.T.; Sirima, A.; Mkumbo, P.J. A Review of Ecotourism in Tanzania: Magnitude, Challenges, and Prospects for Sustainability. J. Ecotourism 2015, 14, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howitt, J.; Mason, C.W. Ecotourism and Sustainable Rural Development in Pérez Zeledón, Costa Rica. J. Rural Community Dev. 2018, 13, 1. Available online: https://journals.brandonu.ca/jrcd/article/view/1478 (accessed on 2 July 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).