Geotechnical Aspects of N(H)bSs for Enhancing Sub-Alpine Mountain Climate Resilience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Land Resilience Evaluation

3. Resilience of Mountain Environments

3.1. Geotechnical Aspects of Mountain Resilience

3.2. Engineering Geostructures for Resilient Mountain Environments

3.3. Geotechnical Factors Influencing Slope Stability and Landslide Classification

4. Climate Vulnerability and Slope Stability in Mountain Regions

4.1. Overview of Climate Threats

4.2. Effects of Climate Threats

4.3. Consequences of Climate Threats

4.4. Measures for Slope Stability

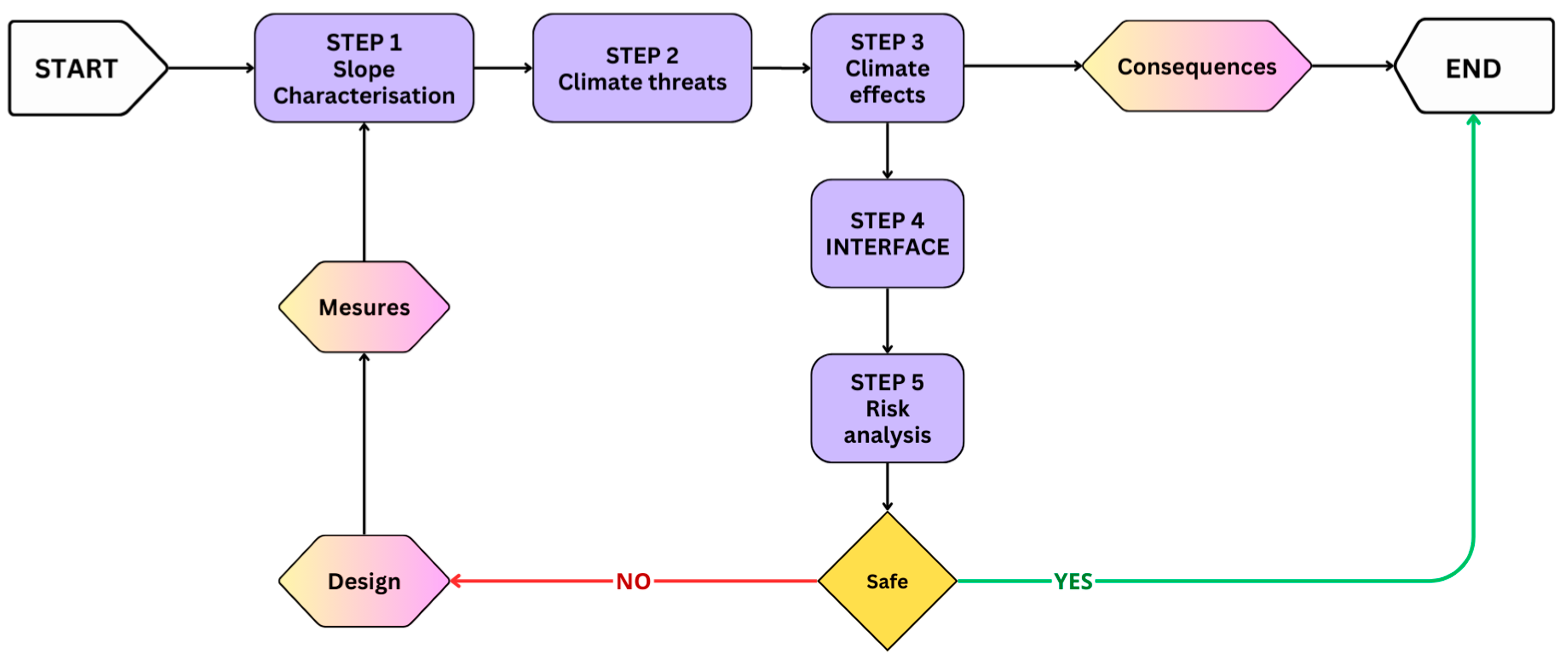

5. Climate-Adaptive Resilience Evaluation Concept

- Input Data—Characterization: Collecting detailed information on slope properties and geotechnical conditions, including material composition, slope geometry, and vegetation cover.

- Climate Threats: Identifying climate-related hazards, such as increased rainfall intensity, temperature fluctuations, and shifting weather patterns.

- Climate Effects: Evaluating the direct impacts of these threats, including changes in soil moisture levels, erosion rates, and slope stability.

- Consequences: Analyzing the broader implications, such as habitat degradation, infrastructure damage, and heightened landslide risks.

5.1. Approaches for Achieving Climate Neutrality

5.2. Approaches to Climate Change Mitigation

5.3. Planning Steps, Criteria, and Measures for Slopes

5.4. The Role of the Interface in Geomechanical Analyses

5.5. Conventional Measures, Nature-Based Solutions (NbSs), and Hybrid Solutions (NHbSs)

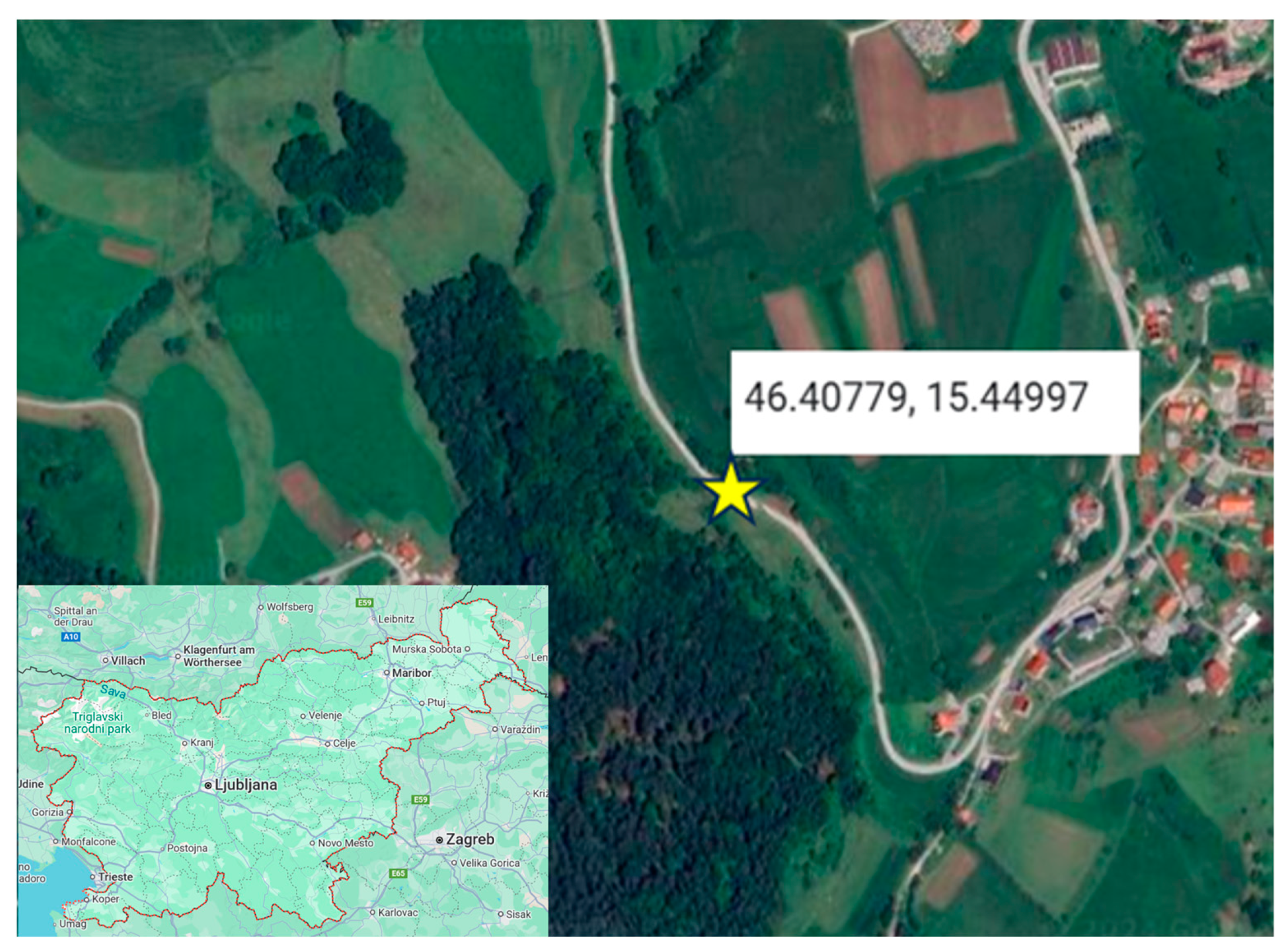

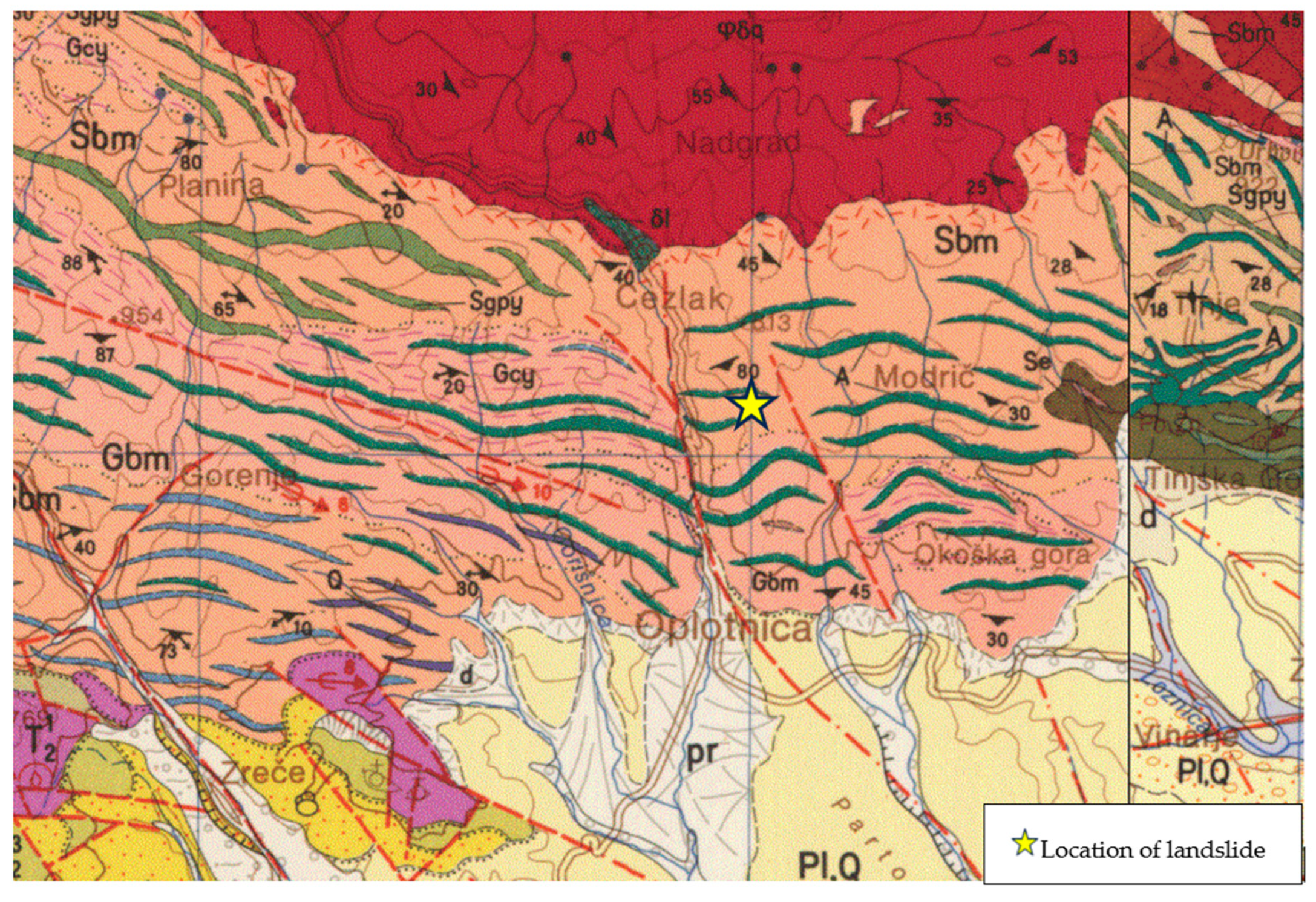

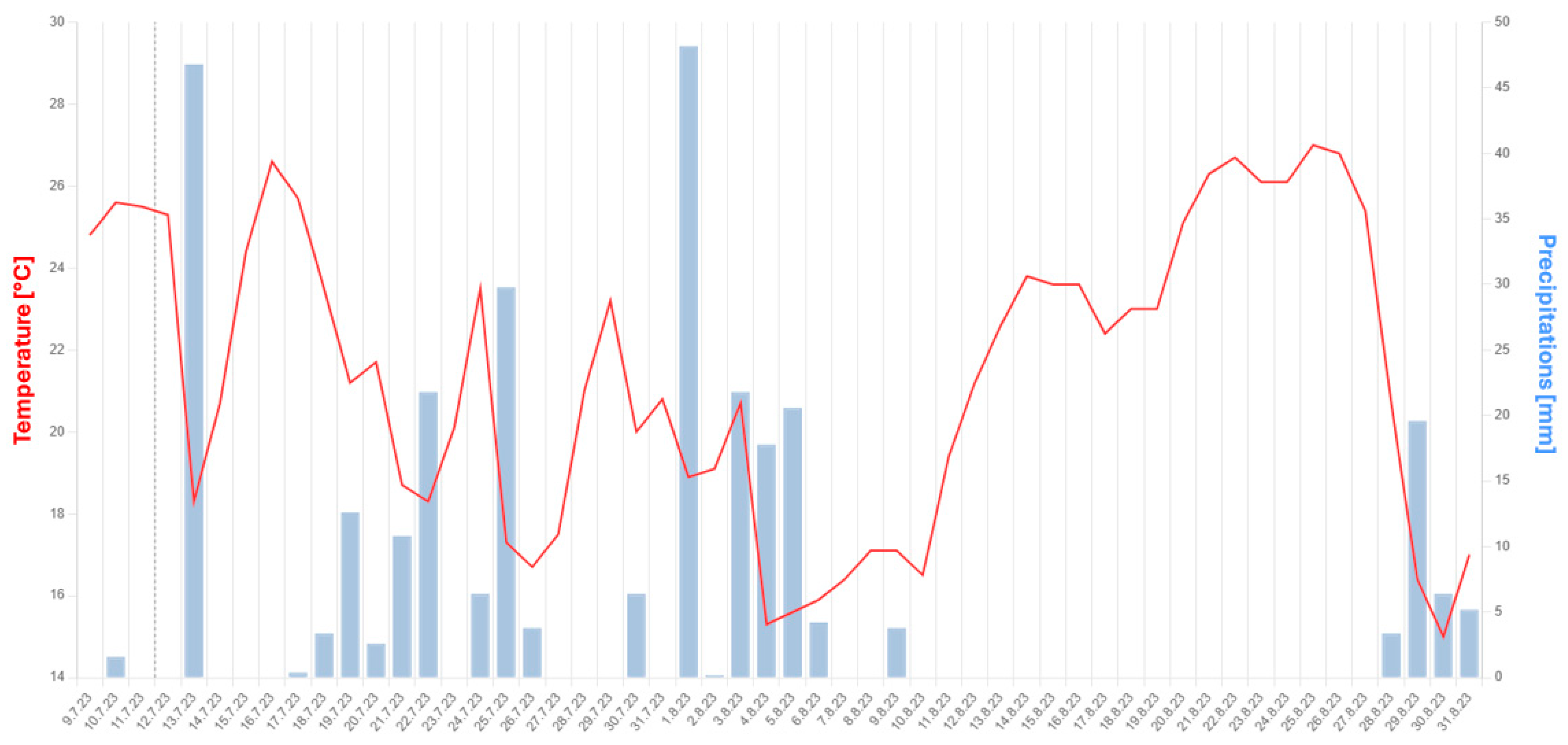

6. Implementation of Climate-Adaptive Resilience Evaluation Concept

Example of Landslides “Kebelj” in the Sub-Alpine Pohorje Mountains

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sokolova, M.V.; Fath, B.D.; Grande, U.; Buonocore, E.; Franzese, P.P. The Role of Green Infrastructure in Providing Urban Ecosystem Services: Insights from a Bibliometric Perspective. Land 2024, 13, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, B.; Song, W.; Yu, H. The Relationship between Rural Sustainability and Land Use: A Bibliometric Review. Land 2023, 12, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, M.; Li, R.; Shalamzari, M.J.; Ren, Y.; Silakhori, E. Comprehensive Assessment of Drought Susceptibility Using Predictive Modeling, Climate Change Projections, and Land Use Dynamics for Sustainable Management. Land 2025, 14, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggel, C.; Clague, J.J.; Korup, O. Is Climate Change Responsible for Changing Landslide Activity in High Mountains? Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2012, 37, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, F.; Brugger, K.; Haslinger, K.; Auer, I. The Climate of the European Alps: Shift of Very High Resolution Köppen-Geiger Climate Zones 1800–2100. Meteorol. Z. 2017, 26, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrorillo, M.; Licker, R.; Bohra-Mishra, P.; Fagiolo, G.; Estes, L.D.; Oppenheimer, M. The Influence of Climate Variability on Internal Migration Flows in South Africa. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 39, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/research-area/environment/nature-based-solutions_en/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Babí Almenar, J.; Petucco, C.; Navarrete Gutiérrez, T.; Chion, L.; Rugani, B. Assessing Net Environmental and Economic Impacts of Urban Forests: An Online Decision Support Tool. Land 2022, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, L.; Setyowati, A.B. Toward a Socially Just Transition to Low Carbon Development: The Case of Indonesia. Asian Aff. 2020, 51, 875–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolovska, A.; Josifovski, J.; Susinov, B.; Abazi, S. Erosion of Soil Slopes under the Influence of Atmospheric Actions and Stabilization with Natural Polymer Solutions. In Proceedings of the Second Macedonian Road Congress, Skopje, North Macedonia, 3–4 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- BenDor, T.; Lester, T.W.; Livengood, A.; Davis, A.; Yonavjak, L. Estimating the Size and Impact of the Ecological Restoration Economy. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murti, R.; Mathez-Stiefel, S. Social Learning Approaches for Ecosystem-Based Disaster Risk Reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 33, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquatic Ecosystem Health and Management. Key Role of Modelling Techniques in the Conservation and Management of Diverse Freshwater Ecosystems Models from North America, Africa and India. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2024, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, B.K.; Rafiei Emam, A.; Masago, Y.; Kumar, P.; Regmi, R.K.; Fukushi, K. Assessment of Future Flood Inundations under Climate and Land Use Change Scenarios in the Ciliwung River Basin, Jakarta. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2018, 11, S1105–S1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, N.Y.; Traore, V.B.; Ndiaye, M.L.; Isimemen, O.; Celestin, H.; Sambou, B. Assessment of Climate Trends and Land Cover/Use Dynamics within the Somone River Basin, Senegal. Am. J. Clim. Change 2017, 6, 513–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.E.; Demory, M.-E.; Leung, L.R.; Ramos, A.M.; Shields, C.A.; Rutz, J.J.; Siler, N.; Villarini, G.; Hall, A.; Ralph, F.M. Responses and Impacts of Atmospheric Rivers to Climate Change. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, R.; Luthe, T.; Pedoth, L.; Schneiderbauer, S.; Adler, C.; Apple, M.; Acosta, E.E.; Fitzpatrick, H.; Haider, J.; Ikizer, G.; et al. Mountain Resilience: A Systematic Literature Review and Paths to the Future. Mt. Res. Dev. 2022, 42, A23–A36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, D. Literature Review: Systematic Review. In Rituals and Music in Europe; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bračko, T.; Žlender, B.; Jelušič, P. Implementation of Climate Change Effects on Slope Stability Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bračko, T.; Jelušič, P.; Žlender, B. A Concept for Adapting Geotechnical Structures Considering the Influences of Climate Change. Urbani Izziv 2024, 35, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Veintimilla, D.; Ochoa-Cueva, P.; Arteaga-Marín, J. Evaluation of the Hydrological Response to Land Use Change Scenarios in Urban and Non-Urban Mountain Basins in Ecuador. Land 2024, 13, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehari, A.; Genovese, P.V. A Land Use Planning Literature Review: Literature Path, Planning Contexts, Optimization Methods, and Bibliometric Methods. Land 2023, 12, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kang, J.-Y.; Hwang, C. Identifying Indicators Contributing to the Social Vulnerability Index via a Scoping Review. Land 2025, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, S.H.; Grêt-Regamey, A. Policy Strategies to Foster the Resilience of Mountain Social-Ecological Systems under Uncertain Global Change. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 66, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, F.R.; Park, M.S.-A.; Golden, K.; Bokharey, I.Z. “We Are the Soul, Pearl and Beauty of Hindu Kush Mountains”: Exploring Resilience and Psychological Wellbeing of Kalasha, an Ethnic and Religious Minority Group in Pakistan. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2017, 12, 1267344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arso. Climate Change. Available online: https://meteo.arso.gov.si/met/sl/climate/change/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- CAP Strategic Plan 2023–2027. Available online: https://skp.si/en/cap-2023-2027 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Li, S.; Zhang, J. Landscape Character Identification and Zoning Management in Disaster-Prone Mountainous Areas: A Case Study of Mentougou District, Beijing. Land 2024, 13, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perko, D.; Ciglič, R.; Zorn, M. (Eds.) The Geography of Slovenia; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-14065-6. [Google Scholar]

- Natura 2000. Available online: https://cdr.eionet.europa.eu/help/natura2000 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Pepin, N.C.; Arnone, E.; Gobiet, A.; Haslinger, K.; Kotlarski, S.; Notarnicola, C.; Palazzi, E.; Seibert, P.; Serafin, S.; Schöner, W.; et al. Climate Changes and Their Elevational Patterns in the Mountains of the World. Rev. Geophys. 2022, 60, e2020RG000730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzi, E.; Mortarini, L.; Terzago, S.; von Hardenberg, J. Elevation-Dependent Warming in Global Climate Model Simulations at High Spatial Resolution. Clim. Dyn. 2019, 52, 2685–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Ghate, R.; Maharjan, A.; Gurung, J.; Pathak, G.; Upraity, A.N. Building Ex Ante Resilience of Disaster-Exposed Mountain Communities: Drawing Insights from the Nepal Earthquake Recovery. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 22, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnykovych, M.; Nijnik, M.; Soloviy, I.; Nijnik, A.; Sarkki, S.; Bihun, Y. Social-Ecological Innovation in Remote Mountain Areas: Adaptive Responses of Forest-Dependent Communities to the Challenges of a Changing World. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613–614, 894–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insana, A.; Beroya-Eitner, M.A.; Barla, M.; Zachert, H.; Žlender, B.; van Marle, M.; Kalsnes, B.; Bračko, T.; Pereira, C.; Prodan, I.; et al. Climate Change Adaptation of Geo-Structures in Europe: Emerging Issues and Future Steps. Geosciences 2021, 11, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J.M.; Wright, S.G.; Brandon, T.L. Soil Strength and Slope Stability, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781118917954. [Google Scholar]

- Varnes, D.J. Slope Movement Types and Processes; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Cruden, D.M.; Varnes, D.J. Landslide Types and Processes, Transportation Research Board, U.S. National Academy of Sciences, Special Report, 247: 36–75. Spec. Rep. Natl. Res. Counc. Transp. Res. Board 1996, 247, 36–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hungr, O.; Evans, S.G.; Bovis, M.J.; Hutchinson, J.N. A Review of the Classification of Landslides of the Flow Type. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 2001, 7, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highland, L.M.; Bobrowsky, P.T. The Landslide Handbook: A Guide to Understanding Landslides; U.S. Geological Survey Circular: 1325; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2008.

- European Large Geotechnical Institutes Platform (ELGIP). Available online: https://elgip.org/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- ELGIP. WG Sustainability. Available online: https://elgip.org/working-groups/sustainability/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- ELGIP. Climate Change Adaptation. Available online: https://elgip.org/working-groups/climate-change-adaptation/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Calvin, K. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- EN 1997-1; Eurocode 7: Geotechnical Design Part 1, Part 1. BSI: London, UK, 2004; ISBN 9780580671067/0580671062/0580452123/9780580452123.

- Gulvanessian, H. Eurocode 0—Basis of Structural Design. Civ. Eng. 2002, 3, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pk, S. Effects of Climate Change on Soil Embankments. Master’s Thesis, York University, Toronto, ON, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fredlund, D.G.; Rahardjo, H. Soil Mechanics for Unsaturated Soils; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993; ISBN 9780471850083. [Google Scholar]

- Pratama, G.B.S.; Waspodo, R.S.B.; Putra, H. An Experimental Study on the Unsaturated Soil Parameters Changes Due to Various Degree of Saturation. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2022, 10, 1505–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Genuchten, M. A Closed-Form Equation for Predicting the Hydraulic Conductivity of Unsaturated Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1980, 44, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossrisk. Available online: https://crossrisk.eu/en/ (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Agromet. Available online: https://agromet.mkgp.gov.si/APP2/Tag/Graphs?id=122#pg-title (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Ocepek, D.; Škrabl, S.; Jerman, J.; Car, M. Priročnik Priročnik za Izvedbo Geotehničnih Preiskav; Inženirska Zbornica Slovenije: Ljubljana, Slovenija, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van Genuchten, M.T.; Nielsen, D.R. Describing and Predicting the Hydraulic Properties of Unsaturated Soils. Ann. Geophys. 1985, 3, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Threats | Effects | Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Climate Change | Modifies groundwater, soil, and rock characteristics; enhances weathering processes. | Increased erosion, slope instability, permafrost degradation, altered groundwater, higher sediment loads. |

| Land Use Changes | Soil compaction, habitat loss, altered runoff and sediment transport. | Slope destabilization, landslides, drainage disruptions, long-term erosion. |

| Natural Resource Over-Exploitation | Weakening of rock masses and soil stability. | Landslides, subsidence, soil degradation, and slope destabilization. |

| Pollution | Degradation of soil and rock quality from agricultural runoff, industrial waste, and chemical leaching. | Contaminated aquifers, increased erosion, and weakening of geotechnical structures. |

| Waste | Soil contamination, reduced shear strength, altered permeability. | Risk of slope failure, groundwater contamination, and long-term impacts on soil stability and ecosystem health. |

| Invasive Species | Disrupts soil cohesion and hydrology through non-native plant roots. | Increased erosion, slope destabilization, landslides and soil degradation. |

| Infrastructure and Traffic | Habitat fragmentation, pollution, stress changes in subsurface layers. | Landslides, subsidence, disruption of natural processes. |

| Energy Development | Slope modifications from hydropower dams, wind farms, and mining impacts. | Seismicity, slope failures, hydrological disruption, soil and rock deformation. |

| Ecosystem Shifts | Changes in vegetation patterns and species distributions. | Increased soil erosion, reduced slope stability, and cascading effects on sedimentation and ecosystem health. |

| Loss of Ecosystem Services | Decline in stabilizing vegetation and critical soil processes. | Soil degradation, slope instability, vulnerability to natural disruption. |

| Economic Impacts | Environmental degradation and biodiversity loss harm tourism, agriculture, and forestry. | Reduced income for local communities, increased geotechnical management costs, and economic instability. |

| Type of Geostructures | Ecosystem and Climate Impacts |

|---|---|

| Natural/Engineered Slopes | Provide habitats and regulate water flow. They can disrupt ecosystems and drainage, while vegetation helps with stabilization. |

| Embankments | Alter hydrology, create wildlife barriers, and impact water flow. |

| Foundations | Compact soil, increase runoff, and reduce groundwater recharge. |

| Retaining Walls | Stabilize slopes but may disrupt water flow and habitats, increasing erosion if poorly managed. |

| Bridge Abutments | Modify river flow, sediment transport, and aquatic habitats. |

| Pipelines | Impact groundwater flow and soil moisture; pose pollution risks from leaks. |

| Dikes and Levees | Control flooding but alter ecosystems and floodplain dynamics, increasing downstream risks if not maintained. |

| Slope Stabilization Structures | Enhance stability but disrupt local ecosystems through land alterations. |

| Green Infrastructure | Boost resilience, improve water quality, provide habitats, mitigate urban heat, and reduce carbon emissions. |

| Classification | Types |

|---|---|

| Material Type | Rock: Bedrock or large fragments Soil: Fine-grained materials (clay, silt, sand, gravel) Debris: Mix of rock, soil, and organic matter |

| Movement Type | Falls: Sudden free fall of material (e.g., rockfall, debris fall) Topples: Forward rotation (e.g., rock topple, soil topple) Slides: Movement along a failure plane (rotational or translational) Flows: Viscous movement (e.g., debris flow, mudflow, earthflow, lahar) Creep: Slow, imperceptible movement Spreads: Lateral extension (e.g., lateral spreads, liquefaction) |

| Rate of Movement | Extremely Rapid: >5 m/s (e.g., rockfalls) Very Rapid: 0.05–5 m/s (e.g., debris flows) Rapid: 0.0005–0.05 m/s (e.g., fast earthflows) Moderate: 0.00002–0.0005 m/s (e.g., slow slides) Slow: 0.0000007–0.00002 m/s (e.g., creep) Very Slow: 0.00000005–0.0000007 m/s (e.g., deep-seated creep) Extremely Slow: <0.00000005 m/s (e.g., tectonic movement) |

| Depth | Superficial, affecting top layers Shallow: ≤2 m medium deep: 2–5 m Deep: 5–12 m Very deep: ≥12 m |

| Consequences | Description |

|---|---|

| Slope Instability, Landslides | Climate change, deforestation, and road construction reduce soil cohesion, increasing landslides and rockfalls. |

| Soil Erosion | Improper waste disposal, deforestation, and overgrazing accelerate erosion, weakening slopes and vegetation support. |

| Riverbank Erosion and Flooding | Increased glacial melt and rainfall lead to riverbank erosion and flooding, threatening infrastructure and ecosystems. |

| Soil Weakening | Erosion, thawing of permafrost, or loss of vegetation reduces soil cohesion, making it prone to sliding or collapsing. |

| Debris Flows | Heavy rainfall and glacial melt create debris flows of mud, rock, and organic material, damaging infrastructure. |

| Permafrost Thaw | Thawing of permafrost weakens soil through loss of ice content, leading to ground subsidence and increased instability. |

| Rock Fracturing | Temperature fluctuations or glacial retreat alter pressure on rock, causing fractures and weakening rock mass, increasing landslides and rockfalls. |

| Snowpack Destabilization | Temperature rise or human activity destabilizes snowpacks, increasing avalanche risk. |

| Hydraulic Pressure Changes | Increased rainfall or snowmelt adds weight and water pressure, reducing friction in soil/rock layers, triggering slippage. |

| Avalanches | Warming temperatures and human activity destabilize snowpacks, triggering destructive avalanches. |

| Infrastructure Damage | Erosion, landslides, and permafrost thaw weaken foundations of buildings and roads, leading to safety risks and increased costs. |

| Planning Steps: Safety and Usability Criteria, Considering Climate Change | New Geostructure: New Planning | Existing Geostructure: No Damage Found—Check Safety and Usability of Geostructure | Existing Geostructure: Damage Found—Take Emergency Measures and Redesign |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feasibility Study | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Initial Design | ✔ | - | ✔ |

| Detailed Design | ✔ | - | ✔ |

| Evaluation | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Implementation | ✔ | - | ✔ |

| NbS | Description | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Revegetation | Planting native vegetation to stabilize the soil. | Plant roots absorb water, improve soil structure, and reduce the risk of erosion and landslides. |

| Bioengineering Techniques | Using natural materials combined with vegetation (e.g., live stakes, coir mats, and brush layers) to stabilize slopes. | Enhance slope resistance to erosion, promote vegetation growth, and provide both immediate and long-term stabilization. |

| Terracing | Creating stepped levels on slopes to reduce runoff and soil erosion. | Slows water flow, improves water absorption, and decreases the likelihood of soil saturation and landslides. |

| Check Dams (Small Barriers) | Constructing small barriers made of natural materials across gullies or slopes to slow water runoff. | Retains sediment, reduces erosion, and promotes organic matter accumulation and vegetation growth. |

| Erosion Control Mats | Installing biodegradable mats made from natural fibers. | Mats allow vegetation to grow, enhance surface stabilization, and control erosion. |

| Natural Drainage | Implementing measures to improve drainage in landslide-prone areas. | Reduces water accumulation, soil saturation, and the likelihood of landslides. |

| Reforestation and Afforestation | Planting trees in deforested or degraded areas to restore ecosystems. | Tree roots improve soil stability, enhance water retention, and reduce landslide risks. |

| Riparian Buffers | Creating vegetated zones along waterways and slopes. | Reduce sediment runoff, prevent bank erosion, and protect water quality. |

| Slope Reshaping and Stabilization | Reshaping slopes to a more stable angle and reinforcing with vegetation and organic materials. | Minimizes the risk of landslides by reducing steepness, enhancing stability, and encouraging vegetation cover. |

| Slope Stabilization and Erosion Control | Techniques like revegetation and soil bioengineering to stabilize slopes. | Reduces erosion, promotes vegetation growth, and mitigates instability. |

| Disaster Risk Reduction | Forest barriers and river restoration to manage landslide and flood risks. | Provides natural defenses against disasters, reducing the impacts of floods and landslides. |

| Water Management | Wetland restoration and floodplain conservation for improved water retention. | Enhances water storage capacity, mitigates flooding, and maintains ecosystem functions. |

| Climate Adaptation | Agroforestry and ecosystem restoration to boost climate resilience. | Improves soil stability, enhances ecosystem services, and helps communities adapt to climate change. |

| Biodiversity Conservation | Protected areas, rewilding, and invasive species control to safeguard habitats. | Maintains biodiversity, protects ecosystems, and supports resilience. |

| Sustainable Livelihoods | Eco-tourism and sustainable farming to balance development with conservation. | Strengthens local economies, promotes community engagement, and ensures sustainable use of natural resources. |

| Measures | NbS | NHbS | Gray | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroseeding, turfing, trees | ✔ | They are primarily NbSs. Can become NHbSs when combined with gray solutions, such as irrigation systems or infrastructure. | ||

| Fascines/brush | ✔ | ✔ | An NbS if made with natural materials. Becomes an NHbS when combined with artificial elements like meshes or other gray infrastructure. | |

| Geosynthetics | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Geosynthetics are artificial materials. |

| Substitution/drainage blanket | ✔ | ✔ | If using only artificial materials, it is a gray solution. Can become an NHbS when combined with natural materials. | |

| Riprap | ✔ | ✔ | An NbS if natural materials (e.g., sand) are used. Becomes an NHbS when combined with artificial elements (e.g., concrete structures). | |

| Dentition | ✔ | It is a technical solution using concrete or other materials, so it is considered a gray solution. | ||

| Removal of (potentially) unstable slope mass | ✔ | ✔ | If the technical method does not involve natural processes, it is a gray solution. Combined with an NbS, it can be an NHbS. | |

| Removal of loose, unstable rock blocks | ✔ | ✔ | A technical method without natural processes, thus a gray solution. Combined with an NbS, it can be an NHbS. | |

| Removal of material from driving area | ✔ | Technical methods are gray when they do not use natural processes. Sometimes it is a temporary (urgent) solution. | ||

| Substitution of material in driving area | ✔ | Use of artificial materials for stabilizing the driving area, considered a gray solution. | ||

| Addition of material to the area maintaining stability | ✔ | ✔ | Artificial materials, like concrete or geosynthetics, are used for stabilizing the area, considered a gray solution. | |

| Surface drainage works | ✔ | ✔ | Gray if artificial materials are used. | |

| Local regrading to facilitate runoff | ✔ | Artificial method to reshape the terrain without integrating natural processes. | ||

| Sealing tension cracks | ✔ | Artificial materials used to seal cracks without natural elements. | ||

| Impermeabilization (geomembranes) | ✔ | Use of artificial materials to prevent water passage, without involving natural processes. | ||

| Vegetation–hydrological effect | ✔ | The use of vegetation to improve water balance and prevent erosion is an NbS. | ||

| Hydraulic control works | ✔ | ✔ | Artificial structures for controlling water flow are gray. | |

| Shallow and deep trenches | ✔ | ✔ | Trenches filled with free-draining material are gray. Combined with an NbS, it can be an NHbS. | |

| Sub-horizontal drains | ✔ | ✔ | Gray if artificial drainage is used. | |

| Wells | ✔ | Use of artificial structures for water collection or control without involving natural processes. | ||

| Drainage tunnels, galleries | ✔ | Technical drainage systems without natural processes. | ||

| Vegetation | ✔ | ✔ | It is a natural solution. | |

| Substitution | ✔ | ✔ | Substitution of material with artificial solutions can be an NHbS if it involves an NbS. | |

| Surface or deep compaction | ✔ | Technical methods of surface compaction without natural elements. | ||

| Lime/cement mech. deep mixing | ✔ | Use of artificial materials like cement and lime to stabilize soil, considered a gray solution. | ||

| Grouting with cement or chemical binder | ✔ | Artificial binding materials used to stabilize the ground, considered a gray solution. | ||

| Jet grouting | ✔ | Use of artificial materials to improve soil stability without natural processes. | ||

| Modification of ground water | ✔ | ✔ | Artificial solutions to manage groundwater can be NHbSs if they incorporate NbSs. | |

| Counterfort drains | ✔ | ✔ | Gray if artificial drainage systems are used. | |

| Piles | ✔ | Use of concrete or steel piles for stabilizing soil considered a gray solution. |

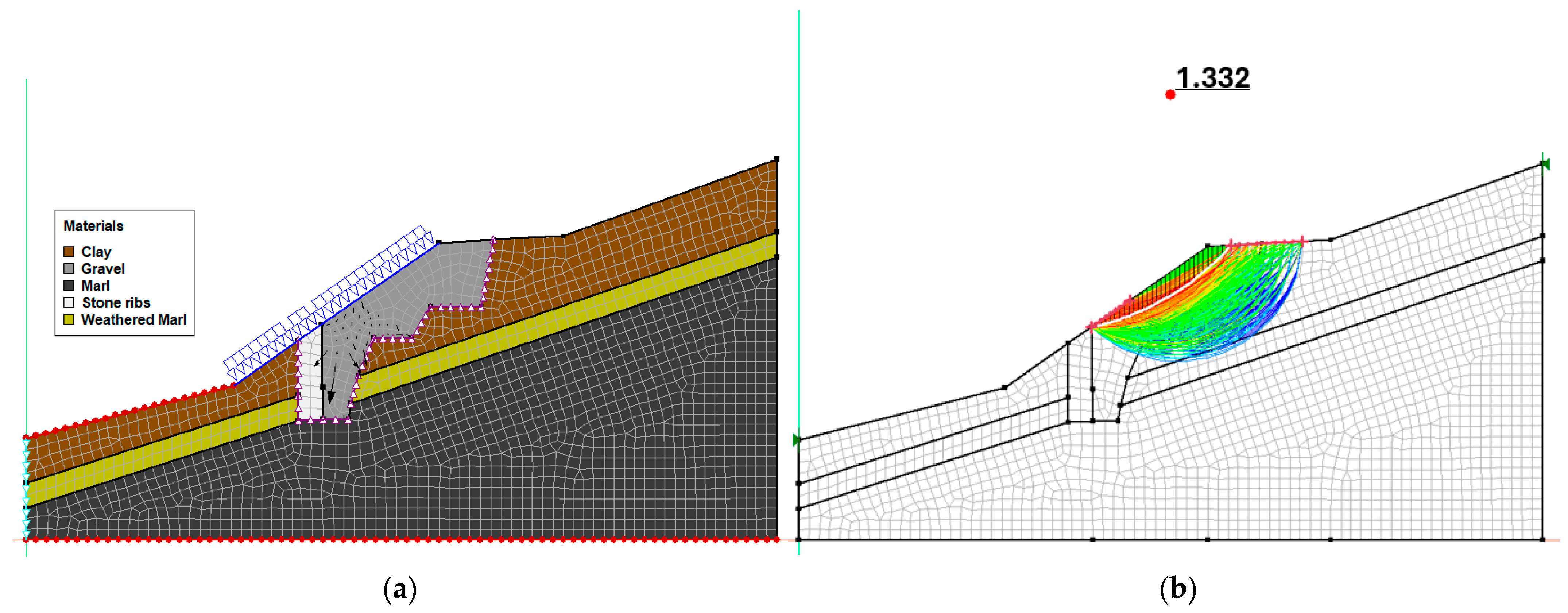

| Property, Symbols (Units) | Scenario * | Sandy Clay | Weathered Marl | Marl | Counterforts | Stone Ribs | Gravel Fill |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated unit weight γ (kN/m3) | A | 18.5 | 19 | 23 | |||

| B | 18.5 | 19 | 23 | ||||

| C | 18.5 | 19 | 23 | 22 | |||

| D | 18.5 | 19 | 23 | 24 | 22 | ||

| Effective cohesion c′ (kPa) | A | 4 | 10 | 100 | |||

| B | 4 (5) | 10 | 100 | 0 | |||

| C | 4 | 10 | 100 | 0 | |||

| D | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 1 | ||

| Effective friction angle Φ′ (°) | A | 24 | 28 | 45 | |||

| B | 26 | 28 | 45 | ||||

| C | 24 | 28 | 45 | 35 | |||

| D | ≤20 | ≤20 | 45 | 45 | 35 | ||

| Saturated permeability ky = kx (m/s) | A, B, C, D | 1·10−6 | 1·10−6 | 5·10−10 | 1·10−4 | 1·10−5 | 1·10−4 |

| Volumetric water content VWC = Vw/Vs (-) | A, B, C, D | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.005 | |||

| Compressibility mv (1/kPa) | A | 5·10−4 | 5·10−4 | 1·10−7 | |||

| B | 5·10−4 | 5·10−4 | 1·10−7 | ||||

| C | 5·10−4 | 5·10−4 | 1·10−7 | 1·10−5 | |||

| D | 5·10−4 | 5·10−4 | 1·10−7 | 1·10−8 | 2·10−5 |

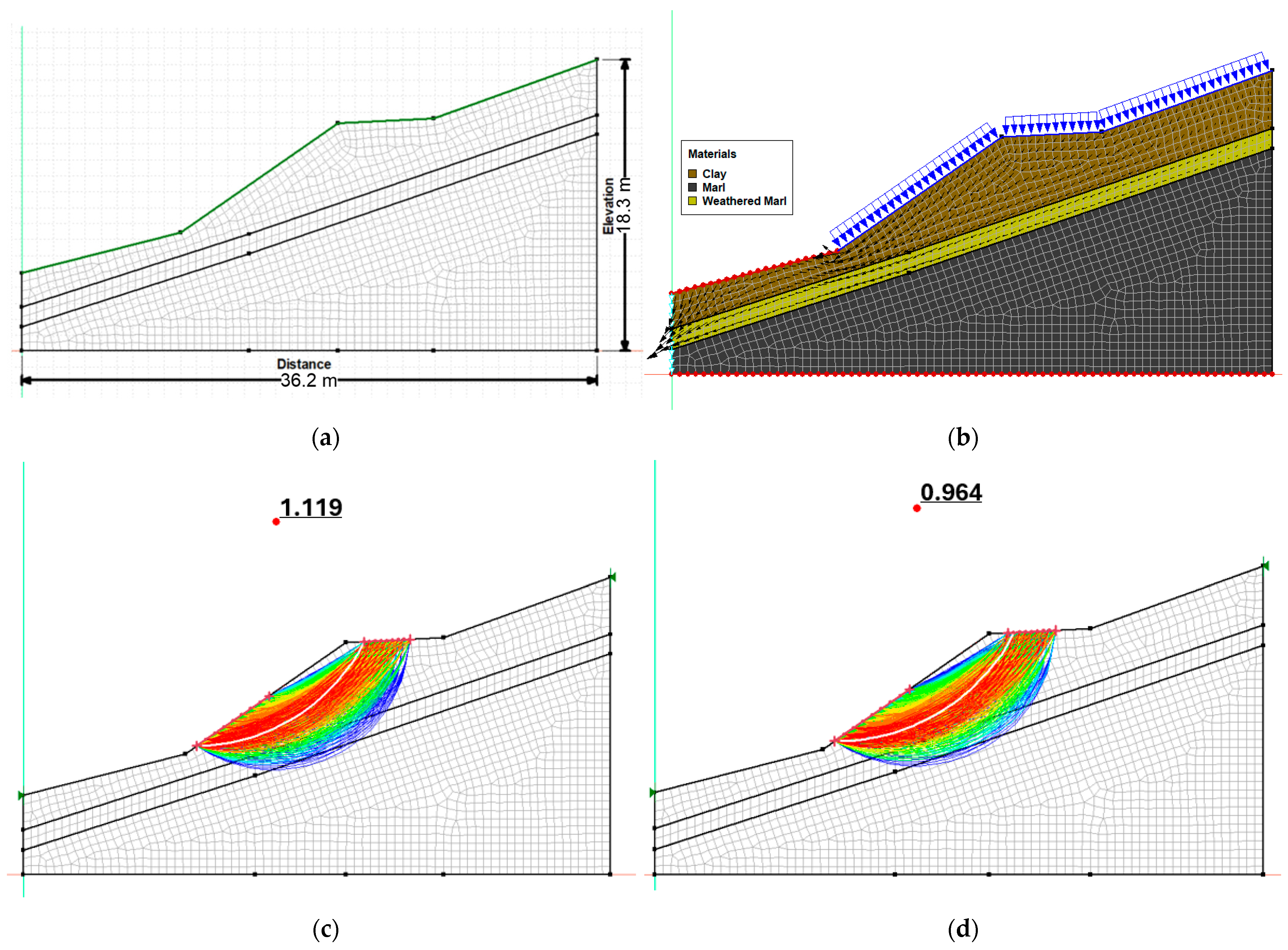

| Time (Days) | Without Remediation, NI = 0.5794 × 10−7 m3/s/m2 | Without Remediation, NI = 1.157 × 10−7 m3/s/m2 | Without Remediation, NI = 1.736 × 10−7 m3/s/m2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.119 | 1.119 | 1.119 |

| 1 | 1.112 | 1.091 | 1.060 |

| 2 | 1.058 | 1.004 | 0.964 |

| 3 | 1.011 | 0.956 | |

| 4 | 0.984 | ||

| 5 |

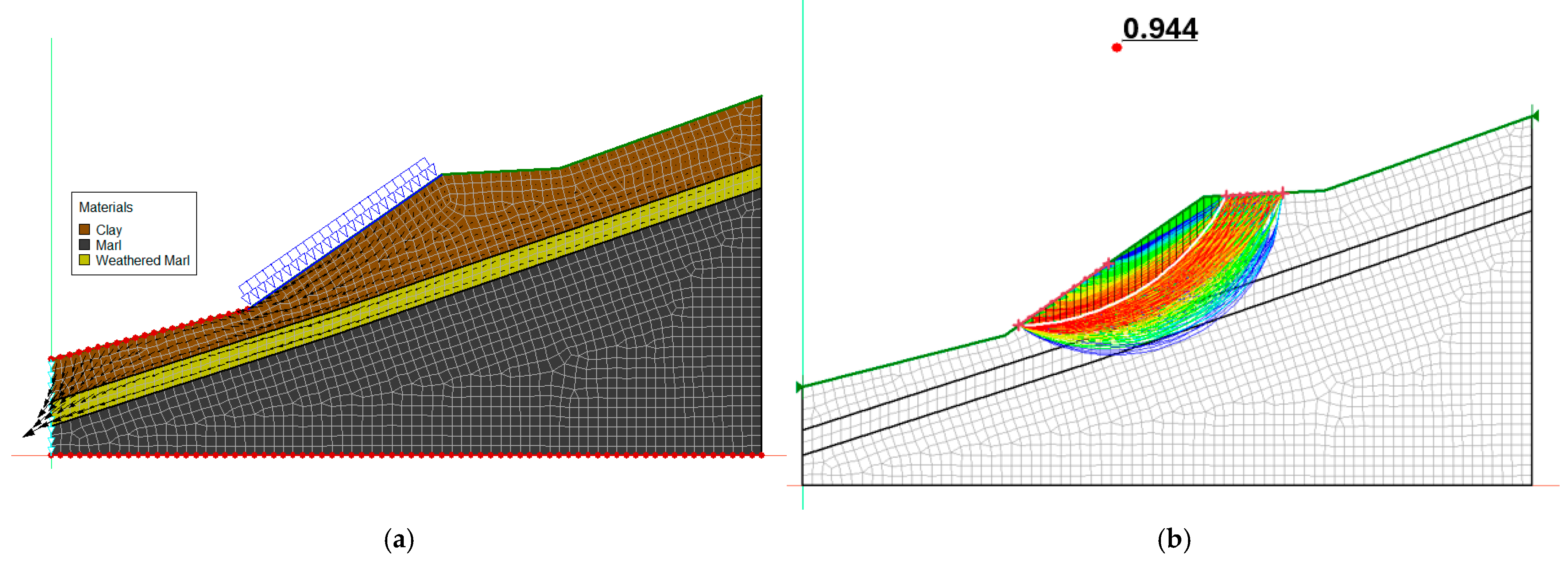

| Time (Days) | Without Remediation, NI = 0.5794 × 10−7 m3/s/m2 | Without Remediation, NI = 1.157 × 10−7 m3/s/m2 | Without Remediation, NI = 1.736 × 10−7 m3/s/m2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.195 | 1.195 | 1.195 |

| 1 | 1.141 | 1.106 | 1.071 |

| 2 | 1.071 | 1.022 | 0.982 |

| 3 | 1.038 | 0.986 | |

| 4 | 1.019 | ||

| 5 | 1.015 |

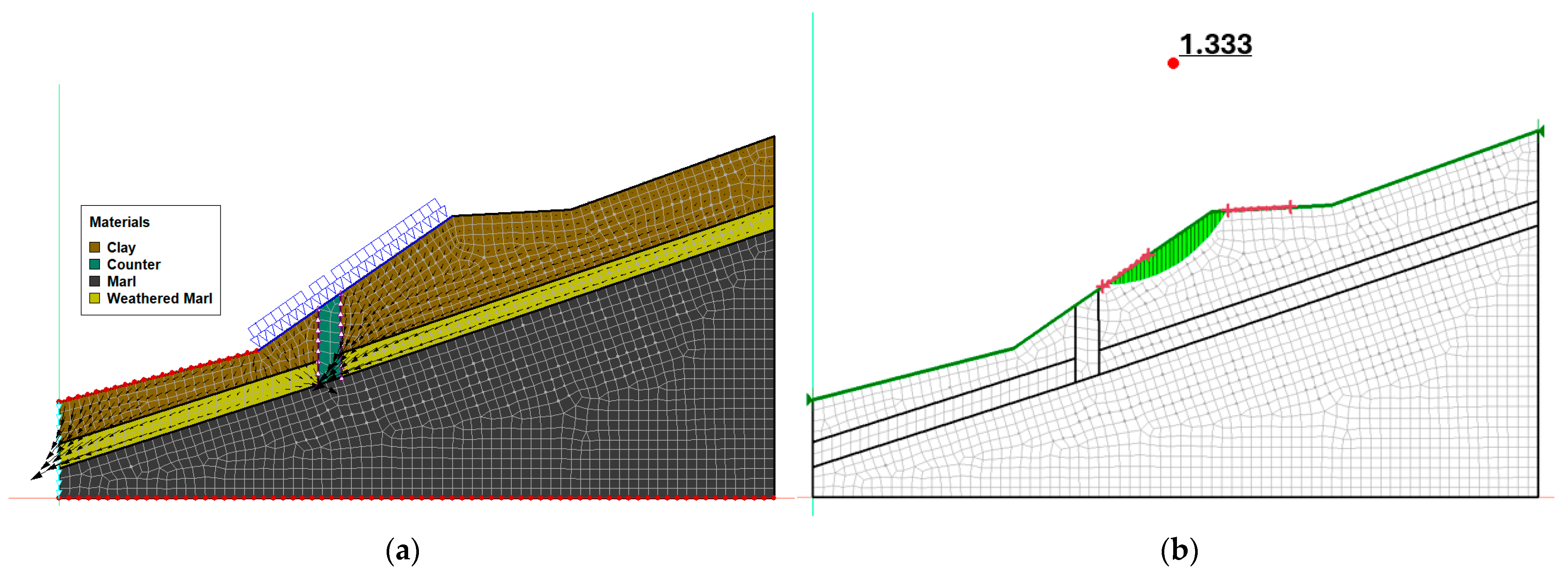

| Time (Days) | Without Remediation, NI = 0.5794 × 10−7 m3/s/m2 | Without Remediation, NI = 1.157 × 10−7 m3/s/m2 | Without Remediation, NI = 1.736 × 10−7 m3/s/m2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.275 | 1.275 | 1.275 |

| 1 | 1.212 | 1.179 | 1.146 |

| 2 | 1.139 | 1.095 | 1.058 |

| 3 | 1.107 | 1.060 | 1.021 |

| 4 | 1.088 | 1.036 | 0.999 |

| 5 | 1.084 | 1.030 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bračko, T.; Jelušič, P.; Žlender, B. Geotechnical Aspects of N(H)bSs for Enhancing Sub-Alpine Mountain Climate Resilience. Land 2025, 14, 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030512

Bračko T, Jelušič P, Žlender B. Geotechnical Aspects of N(H)bSs for Enhancing Sub-Alpine Mountain Climate Resilience. Land. 2025; 14(3):512. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030512

Chicago/Turabian StyleBračko, Tamara, Primož Jelušič, and Bojan Žlender. 2025. "Geotechnical Aspects of N(H)bSs for Enhancing Sub-Alpine Mountain Climate Resilience" Land 14, no. 3: 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030512

APA StyleBračko, T., Jelušič, P., & Žlender, B. (2025). Geotechnical Aspects of N(H)bSs for Enhancing Sub-Alpine Mountain Climate Resilience. Land, 14(3), 512. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030512