Abstract

The new EU Cohesion Policy for 2021–2027 aims for inclusive and sustainable growth to address regional disparities by improving transport connectivity, digitalisation, and social inclusion, thereby reducing peripheral isolation. It is intended to provide development tools and enable investments in green and digital transitions to integrate peripheral areas more effectively with their development centres. This study assumes that, considering the EU cohesion policy objectives, regional centres (in Poland, centres of administrative territorial units named Voivodeships) should exert significant economic and social influence over their administrative regions. This aligns with both classic spatial concepts of socio-economic development and contemporary approaches to sustainable development. The research aimed to assess the extent to which regional centres are connected to their regions and their impact on the entire regional hinterland, particularly on municipalities outside the agglomeration system. The study identified municipalities that lack the influence of regional centres, creating zones with challenging socio-economic development conditions (based on the road network and the population potential of the Huff model). The analysis reveals that the highest probabilities are observed near Warsaw (Mazowieckie voivodeship; 0.7548) while the lowest are around Olsztyn (Warmińsko-Mazurskie voivodeship; 0.6763). The deepest depression in terms of usage of the regional capital is observed in the Zachodniopomorskie voivodeship. In this voivodeship, municipalities in the internal peripheries have an average probability coefficient of 0.3015.

1. Introduction

The main goals of traditional regional policy are increasingly being replaced by the more recent concepts of polycentric development, related to a better use of the potential of cities and their functional areas [1,2,3]. Most often they include components of the cohesion policy and strategies for enhancing the competitiveness of regional structures. Zonal approaches, based on growth nodes and poles, as well as initiatives supporting regions lagging behind are replaced by the policy of inclusion and the activation of regions through city centres (the so-called “engines of the economy”), which integrate them in economic, social, and infrastructural terms [4,5,6]. In the practice of Polish regional policy, this means further strengthening the development potential of metropolitan centres and to some extent also regional, and less often sub-regional, centres. However, on the other hand, this can cause an increase in the differences between the level of development.

The research was inspired by the still open question about the effectiveness of the European cohesion policy in Poland (e.g., [7,8,9]). Raising the level of cohesion within regional structures is a key component of the EU cohesion policy, which remains a primary investment strategy aimed at regions and cities within Member States. The policy’s main objectives include supporting employment, enhancing enterprise competitiveness, fostering economic growth, promoting sustainable development, and improving quality of life. Depending on the level of gross GDP (an index of the initial level of economic development), three categories of territories are distinguished: less developed regions, more developed regions, and regions in transition. Support funds are allocated to these regions with varying intensities [10,11,12]. The policy ensures the concentration of resources from the funds in appropriate proportions relative to GDP, aiming to support the development of less developed regions. However, a significant obstacle to achieving these objectives is the considerable internal diversification of regions, which is also observed in Poland. The larger the regional structures, the more inconsistencies they exhibit in terms of socio-economic, spatial, infrastructural, and sustainable growth. The current focus also includes addressing climate change, youth unemployment, and integrating migration, to ensure a more holistic and inclusive approach to regional development.

When implementing the cohesion policy, its main goal (for the 2014–2020 period), i.e., supporting the comprehensive and harmonious development of the entire structure, became increasingly difficult to achieve, especially at the level of individual European Union countries. Although over 75% of the cohesion policy funds were still allocated to support the convergence process, the remaining approximately 20% was allocated to supporting regional competitiveness and employment, which strengthened divergent phenomena. After 2000, at the regional level, Poland’s territorial differentiation deepened, similar to the vast majority of EU countries. However, on the scale of the entire EU, the process of convergence progressed, showing rather the effectiveness of the cohesion policy and justifying the necessity to continue it (cf.: results of the analysis of the last four EU programme periods, e.g., [13,14,15,16]). In the regional structure of Poland, the importance of the advantages of metropolises over peripheral regions (inter-metropolitan regions) and over peripheral zones in “their own” regions grew (cf. among others: [17,18,19,20,21,22]). In the spatial arrangement, there were clear differences of a macroregional character (east–west/metropole–periphery) and a sectoral nature (city–village/service sector and innovative production–agriculture). Also, for the 2014–2020 period, the selection of cohesion policy priorities in Poland focused on projects that strengthened the concentration and agglomeration processes and, as a consequence, caused divergence on a regional scale (rapid growth of the metropolis) and national scale (the growing advantage of Warsaw as the capital)1.

In the 2021–2027 period, the EU Cohesion Policy aims to adapt and respond to contemporary challenges by fostering inclusive and sustainable growth across all regions. Building on the successes of and lessons from previous periods, the policy focuses on five main objectives [11]: Smarter Europe: Enhancing innovation and competitiveness by promoting digitalization, technological advancements, and support for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) [a]; Greener Europe: Prioritizing climate change mitigation, energy transition, and environmental sustainability. This includes significant investments in renewable energy, energy efficiency, and resilient infrastructure [b]; More Connected Europe: Improving mobility and connectivity through investments in transport and digital networks, ensuring that even the most remote areas are well-integrated into broader economic activities [c]; More Social Europe: Fostering inclusive growth by addressing social inequalities, improving access to education and healthcare, and supporting employment, particularly for youth and marginalized groups [d]; Europe Closer to Citizens: Promoting sustainable and integrated development strategies at the local level, ensuring that regional development is tailored to the unique needs and potentials of individual communities [e].

These objectives are accompanied by a stronger emphasis on good governance, stakeholder engagement, and the integration of cross-cutting issues such as gender equality, non-discrimination, and sustainable development [23]. The new EU Cohesion Policy for 2021–2027 focuses on inclusive and sustainable growth to address regional disparities. It emphasizes improving transport connectivity, digitalisation, and social inclusion to reduce peripheral isolation. By tailoring local development strategies and investing in green and digital transitions, it aims to integrate peripheral areas more effectively [12].

This study assumes that, considering the objectives of the EU cohesion policy, regional centres2 (in Poland’s voivodeship’s capitals) should influence or have dominant economic and social links with the largest possible part of their administrative regions. This understanding represents a reference to both the classic spatial concepts of socio-economic development (growth poles, development paths, centres, etc.) and to contemporary approaches related to permanent or sustainable development (e.g., new economic geography, polarization and diffusion models, geographic distance, etc.).

The aim of the research was to recognize to what extent regional centres are connected with their regions and to what extent they affect the entire regional hinterland, and, in particular, have relations with municipalities outside the agglomeration system. An attempt was made to identify municipalities that “do not feel” the influence of regional centres, perceived as their mutual relations (impact, cooperation, interaction) and connections (economic, social, cultural flows, etc.). On a regional scale, this creates zones with difficult or poorer conditions for socio-economic development.

2. Approaches to Research on the Integrity of Regional Structures

Various methods allow for the examination of the integrity, differentiation, and hierarchy of linkages in regional structures3. This study employed the Huff relative gravity model [33,34]4. The chosen research procedure belongs to the group of potential models a group of techniques widely used in the analysis of development levels. In these models, potential is interpreted as a measure of the influence of regions that are part of the analyzed system. The intensity of interactions between regions depends not only on their size but also on their location [27,29,39]. The formula that describes the model is as follows:

where Pij represents the probability that a resident of the region will satisfy their needs in a given city; Sj is the potential of the city’s population; Tij represents the cost availability of the city, determined on the basis of the increasing costs of driving on public roads; and parameter “a” reflects the impact of cost availability on satisfying needs [40].

Originally, in its primary application, the parameter Pij was indicative of the likelihood that a single consumer living in region i would visit a shop located in place j. The Sj parameter initially represented the size of a retail establishment. Tij was a measure of the time required for a consumer to travel from region i to the shopping location j, and the parameter reflecting the impact of travel time on shopping-related movements was determined based on empirically established quantities. This model, frequently employed to ascertain the extent of market impacts, has been adapted and modified numerous times to suit various research objectives. This has been achieved by altering the quantities that determine market attractiveness (Sj), the method used to determine the accessibility of the location (Tij), and the value of the ‘a’ parameter (a value of 2 is the most often used) [41,42,43], which has also been used in spatial interaction models [44]. There are also some more recent, direct applications of the model for the determination and indication of the extent of the impact of large shopping centres, health centres, and hospitals or other social relations, i.e., [45,46,47,48]; in addition, the results of other research also highlight the relatively higher life satisfaction in the rural surroundings of bigger urban agglomerations in more developed countries [49,50,51].

The use of population figures as a potential measure is empirically validated due to their strong correlation with other indicators of development level and they are frequently employed in research on interregional relationships [27,52,53]. Similarly, studies on the interdependencies arising from improved transport accessibility at the regional level have shown that the interplay between economic and population potentials as well as GDP per capita in both intra-European and intra-national terms might be a good way to delimit inner peripheries [54,55].

Calculations were carried out using data obtained from geoportal.gov.pl and stat.gov.pl, which are official sources of spatial and statistical data available in Poland. For spatial data, the State Register of Borders (PRG) as of 1 January 2024 and the SKDR road layer of the BDOT10k map as of 31 December 2023 were used. For statistical data, the total population status provided by municipalities and dated 31 December 2023 was used. Calculations were conducted using a raster model in SAGA GIS 7.8.2 software with the cost module, and the friction map used to generate the fractal friction coefficients is presented in Table 1. In this study, population data from Polish municipalities were used as an indicator of potential and the frictions in the road network were used as a basis for cost. Friction was determined on a scale from 0 to 1 based on the distribution of the maximum speed applicable in Poland for vehicular traffic on various types of roads, with the fuzzification carried out using an s-shaped function applied to real numbers.

Table 1.

Friction coefficients.

In our research into the impact ranges and interaction zones of regional centres in Poland itself, the P parameter was calculated for 18 regional capitals (the calculation was performed using software from the SAGA GIS as well as QGIS). The results are presented in an analytical grid (a polygon with a side of 100 m) and by municipality (with the average calculated for the pixels located within its area presented in the layout of the municipalities).

The boundary of the impact (the direct impact zone) was defined as a minimum 50% probability of the population being served by a given regional centre. Municipalities were assigned to the influence zones of centres based on the highest probability indications, meaning a municipality was included in the zone of the centre exerting the dominant influence. Municipalities that do not ‘feel’ the influence of regional centres (peripheral municipalities of the centre) are those where the probability did not exceed 50%. These municipalities are influenced by the centre for which the calculations indicated the highest probability among those calculated.

The applied model has several advantages, including (a) the relative simplicity of calculations, (b) the resilience of the results (and thus also the conclusions) to short-term fluctuations in the values used in the study, and (c) flexibility due to the ease of matching the numerator and denominator to the specific purpose of the study. However, it is not without drawbacks, among which the most significant are time-consuming calculations and a fairly strong dependence of the results on the value of the ‘a’ coefficient.

3. Research Results and Their Interpretation

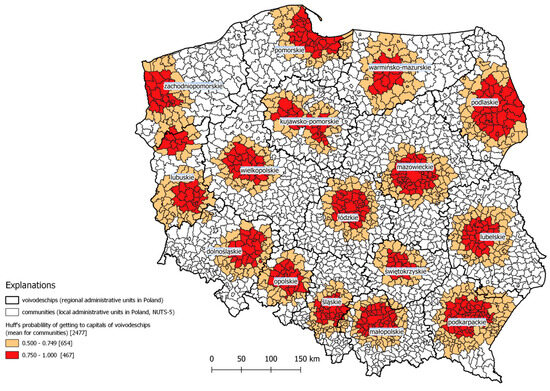

The probability visualization (using QGIS 3.28.3 software), divided into the zones of direct and peripheral influence of a given regional centre, is presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Generally speaking, areas under the direct influence of regional capitals do not extend beyond their voivodeship boundaries, though there are exceptions (shown in red and orange in Figure 1). For instance, the influence zone of Gorzów Wielkopolski extends beyond the borders of the Lubuskie voivodeship and reaches into the influence zone of Szczecin from the south (Zachodniopomorskie voivodeship). Katowice’s zone of influence also extends into the municipalities of the Małopolskie voivodeship, while Gdańsk’s zone of influence includes municipalities in the north-western part of the Warmińsko-Mazurskie voivodeship.

Figure 1.

Regional centres in Poland determined by a minimum 50% probability of interaction in the Huff model. Source: own elaboration.

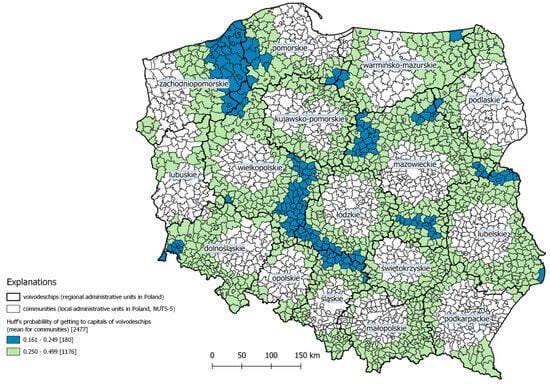

Figure 2.

Peripheral municipalities in Poland with a maximum 50% probability of interaction in the Huff model. Source: own elaboration.

On the other hand, there are relatively broad bands of a low probability of residents fulfilling their needs in the regional capital at the borders of voivodeships, with this phenomenon intensifying towards the north-east (light green colour in Figure 2). There are also relatively large areas with extremely low connectivity to regional centres (blue colour at Figure 2), mainly located at the borders of the Zachodniopomorskie, Pomorskie, and Wielkopolskie voivodeships. A visible band of such municipalities can also be observed between the Wielkopolskie, Opolskie, Śląskie, and Łódzkie voivodeships. Smaller areas of very low probability are primarily located in the external zones of the Mazowieckie voivodeship. They also appear in border municipalities both in the east (Lubelskie and Warmińsko-Mazurskie voivodeships) and west of the country (though in this case, they are limited to the peripheral areas of the Dolnośląskie voivodeship).

What is practically surprising is the smaller extent of the direct impact on the surrounding areas than would be apparent from the size of the centre and its place in the hierarchy of the settlement system. This means that investments and undertakings that strengthen the socio-economic potential of smaller regional centres have a better integrating effect when they are located in cities that are not metropolises [56].

When analyzing the spatial distribution of probabilities for areas under the direct influence of regional capitals, it is important to note that high probabilities of residents meeting their needs in the regional capital are limited to a relatively small number of municipalities that are functionally linked to that city. The smallest percentage of such municipalities is found in the Wielkopolskie voivodeship (25% of the voivodeship’s municipalities), Mazowieckie voivodeship (33%), and Dolnośląskie voivodeship (36%). The highest percentages are in Lubuskie (78% of the voivodeship’s municipalities), Podkarpackie (71%), and Opolskie (66%) (Table 2). The highest probability of residents meeting their needs in the regional capital is among residents of municipalities under the influence of Warsaw (Mazowieckie Voivodeship—average probability 0.7548), Katowice (Śląskie Voivodeship—average probability 0.7532), and Gdańsk (Pomorskie Voivodeship—average probability 0.7532). The lowest probability percentages are among the residents of municipalities surrounding Olsztyn (Warmińsko-Mazurskie voivodeship—0.6763), Wrocław (Dolnośląskie voivodeship—0.6877), and Szczecin (Zachodniopomorskie voivodeship—0.6997) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Minimum 50% probability of interaction in the Huff model—statistics in voivodeships.

Table 3.

Maximum 50% probability of interaction in the Huff model—statistics in voivodeships.

The deepest depression in terms of usage of the regional capital is observed in the Zachodniopomorskie voivodeship. In this voivodeship, municipalities in the internal peripheries have an average probability coefficient of 0.3015. However, it should be noted that their internal variability is relatively high, fluctuating by as much as 0.1065 from the average value. Slightly higher average probability indices are found in municipalities located in the internal peripheries of the Wielkopolskie (0.3121), Mazowieckie (0.3176), Pomorskie (0.3303), and Łódzkie (0.3319) voivodeships. It is also worth noting the relatively large range of municipal probability coefficients in terms of deviations within the internal periphery areas of the Śląskie (0.0837), Łódzkie (0.0835), and Wielkopolskie (0.0835) voivodeships—which strongly correspond with the blue colour in Figure 2.

4. Discussion

This analysis was designed to assess the strength of the functional links ( related to the economy, labour market, education, the public sector, trade and services, and investment) of regional centres with their regions and to assess the impact of regional cities on the entire regional structure in formal (administrative) terms, in particular on local units lying within the zone of direct functional links. These zones were treated as areas of concentration for cohesion policy activities that will enable regional integration processes to accelerate and development opportunities to grow. Additionally, it should be noted that the close connections within the functional zones of regional cities create mutual linkages and integrate them. In contrast, areas outside these functional zones gradually accumulate the negative effects of weaker connections [56,57].

The EU development policy that has been implemented for a long time (at least since 2000), and includes the cohesion policy, which in a territorial sense has been focused on supporting metropolitan-type centres5. As a consequence, the processes of territorial differentiation (in terms of the level of development) are growing on regional, sub-regional, and intra-regional scales [58]. There is a persistent incongruity between centres (regional centres) and their regions [7,21,59,60,61]. Voivodeship centres, which fail to exert their influence over a substantial portion of their regions, do not function as ‘growth poles’. These centres are unable to facilitate the spread of development factors to non-urban (non-metropolitan) areas of the voivodeships, particularly in territorially large regions [62].

Here, reference can be made to the theory of city regions, which are based on the concept of areas of a strong integration within the zones of influence of regional urban centres and serve as a form of effective development management for areas (regions) administratively linked to regional centres. However, firstly, they are not fully effective in areas outside the zones of strong influence of the central centre, and secondly, they can also lead to negative phenomena, such as the draining of human potential or draining of investment capital [63,64]. The mismatch between the zones of influence and formal administrative boundaries indicates that policies for shaping functional areas should be better aligned with the actual impact zones of regional centres [65]. Additionally, these policies should take into account cross-regional relationships in areas where administrative centres have limited influence. This is particularly significant as the peripheral areas within regional structures (especially in larger voivodeships) are extensive. As a result, significant areas weakly or very weakly linked with regional centres, often located in zones of relationships with centres located outside their own region, are deprived of direct development impulses, especially in the context of the preference of regional policy and development policy for the polarization–diffusion model, regardless of the research methodology adopted (cf. [18,21,26,66,67]). The possibility of changing such a development path in peripheral zones is seen mainly in the improvement and expansion of the transport infrastructure of the regions (cf. [55,68,69,70]). In the context of consolidating the regional dichotomy systems between the, metropolitan centres of regions and regional peripheral zones, special attention towards regional and territorial cohesion policies is required in the eastern part of the Zachodniopomorskie Voivodeship (where in the absence of the direct influence of Szczecin, relationships with Bydgoszcz, Gorzów Wielkopolski, Poznań and Gdańsk become more important), and the need to strengthen sub-regional centres (Koszalin, Słupsk) requires the formulation of a national, tailor-made policy aimed at changing development priorities in the marginalized regional peripheries (cf. [71,72]). This is the situation in the southern part of the Wielkopolskie voivodeship (where the peripheries of Poznań meet and the influences of Wrocław, Opole, and Łódź are visible), particularly in the areas of Kalisz and Ostrów Wielkopolski. Moving further through the southern part of the Łódzkie voivodeship (Wieluń) and also the northern part of the Śląskie voivodeship (the long belt between Kłobuck and Szczekociny), this is also the case. The peripheries of the Mazowieckie voivodeship in the northern part (Ostrołęka) and western part (municipalities north of Płock) are also noteworthy, as well as the areas around Biała Podlaska (in the Lubelskie voivodeship). The mentioned areas of peripheralization (which are the result of the research method adopted in the article) are recognizable in Poland, resulting in proposals for the creation of separate new administrative regions, such as the Central Pomeranian (Koszalin) region and the less frequently mentioned Częstochowa region (cf. [73,74]).

It should be noted that the present study is inherently static and illustrates the relationships of regional influences around the year 2024. In this context, however, it is worth highlighting that both demographic potential and socio-economic capacity undergo relatively minor changes, especially within the group of major urban centres, including all regional ones. A dynamic approach, in the context of the study’s aim, does not lead to significantly different results regarding the scope of influence of regional centres and their alignment with administrative-type relationships.

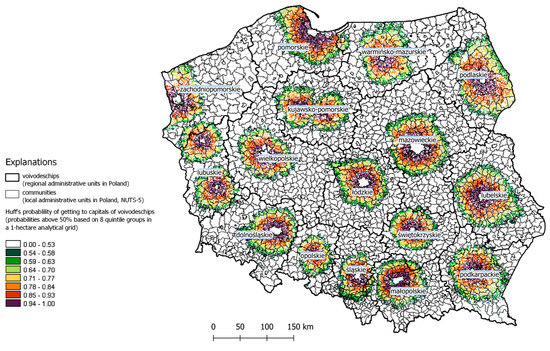

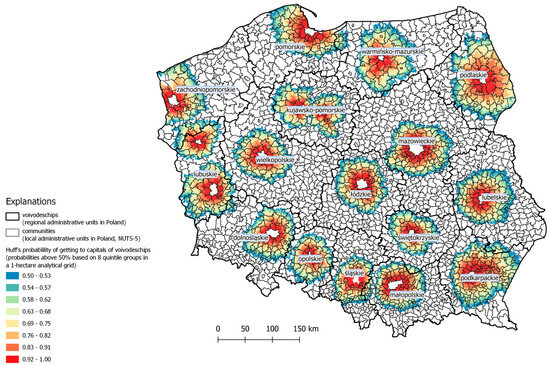

To confirm these statements, one can compare (in Figure 3 and Figure 4) the ranges of influence calculated, respectively, for the state as of 31 December 2012 and 31 December 2023. The method and cost calculation approaches remain analogous; however, changes have occurred in the road network layout, the number of people residing in municipalities, and (in rare cases) the administrative boundaries of municipalities. For data comparability (relative to those published in 2015 [75]), the reference system was also adjusted (to LAEA, EPSG: 3035), and the data calculated were presented in a 1-hectare system, omitting those with a probability of up to 50%.

Figure 3.

Impact zones of metropolitan centres determined using the Huff gravity model based on the spatial accessibility model and population potential data for 2012—visualization of probabilities above 50% based on 8 quintile groups in a 1-hectare (100 m × 100 m) analytical grid. Source: own elaboration [75].

Figure 4.

Impact zones of metropolitan centres determined using the Huff gravity model based on the spatial accessibility model and population potential data for 2023—visualization of probabilities above 50% based on 8 quintile groups in a 1-hectare (100 m × 100 m) analytical grid. Source: own elaboration.

It should be noted that the gravity-based approach is just one of the possible methodologies, and its results are similar to at least some other studies based, among other factors, on multidimensional analyses. The results of these studies at least partially overlap with those presented in this article (cf. [76,77,78]). Various research approaches that have been applied in the Polish practice of delimiting functional areas, along with a methodological summary of this field up to 2023, are included in the study [68]. This study also presents the results of an original delimitation of functional urban areas (FUAs), which were determined based on the population movements of commuters.

A separate issue is the impact of significant transport infrastructure investments in Poland over recent decades. Their influence and importance are primarily evident at the supra-regional level, that is, in the sphere of interactions between metropolises and regional centres. On the regional and sub-regional level, however, improvements in transport and public communication mainly serve to integrate regions with their central hubs, paradoxically worsening the situation of peripheral areas within the regions [21,79]. In-depth research in this area, focused on a dynamic analysis of changes in the transport accessibility of local zones within regions, would be highly valuable. The analysis of the transport accessibility of regional capitals refers to the socio-economic characteristics of territorial units within their respective regions. Poor communication infrastructure is one of the factors (though not necessarily the most important one) contributing to economic, social, and depopulation challenges [80]. Peripheral status arises as a result of weaker, un-strengthened connections with regional centres.

5. Conclusions

Based on our results, it is justified to state that territorially smaller regions are covered by the connections and impact of their centres to a greater extent than larger structures, even if voivodeship centres are not fully equipped with metropolitan infrastructure and functions. The fact that the spatial differences in the size of the zones of socio-economic relationships between smaller and larger centres are relatively small is another conclusion that is important for the regional policy. The direct, predominant influence of metropolises and smaller regional centres covers similar areas, which means that the size of the centres (most often measured by population or economic potential) does not translate into a larger area of strong links with the centre in the region. Some studies support the assumption that urban centres’ network relationships can replace proximity, resulting in potentially weaker intra-regional ties [81]. It is reasonable to conclude that a larger region (voivodeship) generates a wider peripheral zone (Zachodniopomorskie, Mazowieckie and Warmińsko-Mazurskie), and this occurs despite the high probability of the dispersed population fulfilling their needs in the capitals of these regions.

In Poland’s metropolitan regions, socio-economic activity accumulates primarily in the centres but, unlike many large Western European cities, the beneficial effects of metropolization do not spread to outer zones and neighbouring regions (cf. [82,83,84]). There is a flushing out of resources from the regional and interregional fringe of metropolises, which gradually transforms these areas into inner peripheries (intra-regional peripheries). Rationally conducted cohesion policies “weaken” the forces accelerating polarization and peripheralization in the regions. However, even if it is directed at peripheral and inter-metropolitan regions, it is under constant pressure from initiatives that integrate these structures into systems of metropolitan impact.

The emergence of peripheral areas in regions is primarily related to the difficult access to metropolises and regional centres, which is associated with the weaknesses of transport infrastructure or geographical barriers (land diversity and remoteness). Limited accessibility results in a low share in the diffusion of development from higher rank centres and fewer opportunities to participate in the regional labour market, which lead to the intensification of depopulation processes [85,86]. Paradoxically, the implementation of the objectives of the EU cohesion policy may, in such a structure, result in increasing interregional differences and difficulties in ensuring the implementation of its main objectives, especially achieving sustainable development and improving quality of life [87,88].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G. and K.H.; Methodology, P.G. and K.H.; Formal analysis, P.G. and K.H.; Investigation, P.G. and K.H.; Writing—original draft, P.G. and K.H.; Writing—review & editing, P.G. and K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Among the 11 priorities of the cohesion policy for the period 2014–2020, it directly and indirectly strengthens the growth of development disparities, e.g., supporting research, technological development and innovation (1), increasing the availability, use and quality of information and communication technologies (2), promoting sustainable transport and improving key network infrastructures (7), promoting sustainable and high-quality employment and supporting labor mobility (8), investing in education, skills and lifelong learning (10), improving the efficiency of public administration (11) [10]. |

| 2 | The study perceives all cities that play the role of Voivodeship capitals (16 in Poland), as regional centers, however in two regions the administrative function has been divided between two centers (Kujawsko-Pomorskie—Bydgoszcz and Toruń, Lubuskie—Zielona Góra and Gorzów Wielkopolski). There are thus 18 regional centers in total. |

| 3 | The literature on the subject in this area uses a wide range of research methods and techniques widely applied in economic and spatial analysis (i.e., [24,25,26,27,28,29,30], see also [31,32]). |

| 4 | Models of this type had been formulated before, but it was only Huff’s work that disseminated brightly their use [35,36,37,38]. |

| 5 | In the EU countries, these are cities with a diverse population, demographic, economic and socio-cultural potential. |

References

- Shaw, D.; Sykes, O. The Concept of Polycentricity in European Spatial Planning: Reflections on its Interpretation and Application in the Practice of Spatial Planning. Int. Plan. Stud. 2004, 9, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S.; Wishardt, M. The polycentric turn in the Irish spatial strategy. Built Environ. 2005, 31, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, E.; Waterhout, B.; Zonneveld, W. Closing the Gap: Territorial Cohesion through Polycentric Development. Eur. J. Spat. Dev. 2007, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Crescenzi, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Infrastructure and regional growth in the European Union. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2012, 91, 487–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuschewski, A.; Leick, B.; Demuth, M. Growth-based Theories for Declining Regions? A Note on Conceptualisations of Demographic Change for Regional Economic Development. Comp. Popul. Stud. 2016, 41, 225–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratesi, U. Regional Policy; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781351107617/regional-policy-ugo-fratesi (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Kisiała, W.; Bajerski, A.; Stępiński, B. Equalising or polarising: The centre–periphery model and the absorption of EU funds under regional operational programmes in Poland. Acta Oecon. 2017, 67, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowski, Ł.; Mróz, A.; Stanny, M. The Spatial Pattern of the Absorption of Cohesion Policy Funds in Polish Rural Areas. Land 2021, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirodea, F.; Toca, C.V.; Soproni, L. Regional development at the borders of the European Union: Introductory studies. Crisia 2021, LI (Suppl. S1), 7–17. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357868010_Regional_Development_at_the_Borders_of_the_European_Union_Introductory_Studies (accessed on 9 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Polityka Spójności 2014–2020—Inwestycje w Rozwój Gospodarczy i Wzrost Zatrudnienia; Komisja Europejska, Urząd Publikacji Unii Europejskiej: Luksemburg, 2011; Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/inforegio (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Cohesion Policy 2021–2027. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/2021-2027_en (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Malkowska, A.; Bera, A.; Malkowski, A.; Penza, I. Building a more competitive and smarter Europe as a goal of the co-hesion policy of the European union–the perspective of the Polish economy. In Zeszyty Naukowe; Organizacja i Zarządzanie/Politechnika Śląska: Zabrze, Poland, 2024; Volume 191, pp. 371–386. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau-Lepage, L.; Huriot, J.-M.; Perreur, J. À la recherche de la centralité perdue. Rev. d’Économie Régionale Urbaine 2009, 3, 549–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R.; Capello, R. Spatial effects of economic integration: A conceptualization from regional growth and location theories. In International Handbook of Economic Integration: Competition, Spatial location of Economic Activity and Financial Issues; Jovanović, M., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 187–203. [Google Scholar]

- Crescenzi, R.; Giua, M. The EU Cohesion Policy in Context: Regional Growth and the Influence of Agricultural and Rural Development Policies, “Europe in Question”; Discussion Paper; Series No. 85/2014; The London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, S.O.; Egger, P.H.; von Ehrlich, M. Effects of EU regional policy: 1989–2013. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2018, 69, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenik, S. Kształtowanie się metropolii w warunkach polskich—ogólne uwagi. In Gospodarka Przestrzenna, nr XI, Wyd; Korenik, S., Przybyła, Z., Eds.; UE We Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2008; pp. 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- KSRR. Krajowa Strategia Rozwoju Regionalnego 2010–2020: Regiony, Miasta, Obszary Wiejskie; Ministerstwo Rozwoju Regionalnego: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich, K.; Kriszan, A.; Lang, T. Urban development in Central and Eastern Europe—Between Peripheralization and centralization? disP-Plan. Rev. 2012, 48, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, M. Peripheralization: Theoretical concepts explaining socio-spatial inequalities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffner, K.; Gibas, P. Functional areas in the regions and their links to scope sub-regional centres impact. Stud. Reg. 2016, 46, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malý, J. Impact of Polycentric Urban Systems on Intra-regional Disparities: A Micro-regional Approach. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 116–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppido, S.; Ragozino, S.; De Vita, G.E. Peripheral, Marginal, or Non-Core Areas? Setting the Context to Deal with Territorial Inequalities through a Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mynarski, S. Badania Rynkowe w Przedsiębiorstwie, Wyd; Akademii Ekonomicznej w Krakowie: Kraków, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolini, S. Restructuring Europe: Centre Formation, System Building, and Political Structuring Between the Nation State and the European Union; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; von Hofe, R. Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Suchecki, B. (Ed.) Ekonometria przestrzenna. In Metody i Modele Analizy Danych Przestrzennych; Wydawnictwo, C.H. Beck: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, P.M. Cities and Regions as Self-Organizing Systems: Models of Complexity; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue, J.-P.; Comtois, C.; Slack, B. The Geography of Transport Systems. 2020. Available online: https://repositories.nust.edu.pk/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/48739/THE%20GEOGRAPHY%20OF%20TRANSPORT%20SYSTEMS%202006.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Churski, P.; Herodowicz, T.; Konecka-Szydłowska, B.; Perdał, R. Spatial differentiation of the socio-economic development of Poland—“Invisible” historical heritage. Land 2021, 10, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commenges, H.; Giraud, T. Introduction to the Spatial Position Package. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/SpatialPosition/vignettes/SpatialPosition.html (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Commenges, H.; Giraud, T. Potential. 2023. Available online: https://riatelab.github.io/potential/articles/potential.html (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Huff, D.L. A Probabilistic Analysis of Consumer Spatial Behavior. Emerging Concepts in Marketing. In Proceedings of the Winter Conference of the American Marketing Association, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 27–29 December 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Huff, D.; McCallum, B.M. Callibrating the Huff Model Using ArcGIS Model Business Analyst; ESRI: Redlands, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, W.J. (Ed.) The Law of Retail Gravitation; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J.Q. An Inverse Distance Variation for Certain Social Influences. Science 1941, 93, 89–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.Q. A Measure of the influence of a population at a distance. Sociometry 1942, 5, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, D.L. Defining and Estimating a Trading Area. J. Mark. 1964, 28, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowska, K.; Kryszk, H.; Kietlinska, E. The use of gravity model in spatial planning. In Environmental Engineering, Proceedings of the International Conference on Environmental Engineering, ICEE, Vilnius, Lithuania, 27–28 April 2017; Department of Construction Economics & Property, Vilnius Gediminas Technical University: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2017; Volume 10, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Huff, L.D. Parameter Estimation in the Huff Model; ArcUser: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, D.A. A Generalized Huff Model. In Geographical Analysis; Ohio State University Press: Columbus, OH, USA, 1982; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Pirowski, T.; Drzewiecki, W. Wybrane problemy modelowania przestrzennych interakcji zachowań konsumentów z wykorzystaniem GIS. Arch. Fotogram. Kartogr. Teledetekcji 2000, 10, 61-1–61-8. Available online: https://home.agh.edu.pl/~zfiit/publikacje_pliki/Pirowski_Drzewiecki_2000.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2016).

- Kim, P.J.; Kim, W.; Chung, W.K.; Youn, M.K. Using new Huff model for predicting potential retail market in South Korea. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 1543–1550. [Google Scholar]

- Brol, W.; Brzezinka, M.; Ślązok, A. Moduł przestrzenny. Cześć I: Dostępność Przestrzenna Wybranych Usług Publicznych w Województwie Śląskim. Cześć II: Siła i Zasięg Oddziaływania Ośrodków Akademickich Województwa Śląskiego (Raporty z Badań); Regionalne Centrum Analiz i Planowania Strategicznego, Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Śląskiego: Katowice, Poland, 2015; Available online: http://rcas.slaskie.pl/files/zalaczniki/2015/06/16/1350456627/1434452355.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2016).

- Fotheringham, A.S.; O’Kelly, M.E. Spatial Interaction Models: Formulations and Applications; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1989; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dramowicz, E. Retail Trade Area Analysis Using the Huff Model. 2005. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/665723326/Retail-Trade-Area-Analysis-Using-Huff-Model (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Youn, M.K.; Kim, W.; Kim, P.J.; Lee, S.Y. Retail sales forecast analysis of general hospitals in Daejeon, Korea, using the Huff model. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 971. [Google Scholar]

- Dolega, L.; Pavlis, M.; Singleton, A. Estimating attractiveness, hierarchy and catchment area extents for a national set of retail centre agglomerations. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 28, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azanlerigu, J.A.; Atiga, O. Applicability of the huff model in the estimation of market shares of supermarkets within the Tamale metropolis in Ghana. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 9, 782–788. [Google Scholar]

- Dogaru, T.; VAN Oort, F.; Thissen, M. Agglomeration economies in European regions: Perspectives for objective 1 regions. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2011, 102, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckroth, M.; Kemppainen, T. (Un)Happiness, where are you? Evaluating the relationship between urbanity, life satisfaction and economic development in a regional context. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2021, 8, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckroth, M.; Kemppainen, T. Rural conservatism and the urban spirit of capitalism? On the geography of human values. Reg. Stud. 2023, 57, 1747–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyż, T. Application of the potential model to the analysis of regional differences in Poland. Geogr. Pol. 2002, 75, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Michalek, J.; Zarnekow, N. Application of the Rural Development Index to Analysis of Rural Regions in Poland and Slovakia. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 105, 1–37. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41409399 (accessed on 9 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rosik, P.; Pomianowski, W.; Komornicki, T.; Goliszek, S.; Szejgiec-Kolenda, B.; Duma, P. Regional dispersion of potential accessibility quotient at the intra-European and intranational level. Core-periphery pattern, discontinuity belts and distance decay tornado effect. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 82, 102554. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0966692319303679 (accessed on 9 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Heffner, K.; Gibas, P. Polityka spójności UE a obszary funkcjonalne centrów regionalnych w Polsce. In Unia Europejska w 10 lat po Największym Rozszerzeniu; Pancer-Cybulska, E., Szostak, E., Eds.; Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2015; Volume 380, pp. 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, K.; Gibas, P. Centra Regionów a spóJność Regionalna w Polsce; Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu: Wrocław, Poland, 2017; Volume 466, pp. 98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, E.; Zaucha, J.; Ciołek, D. Measuring territorial cohesion trends in Europe: A correlation with EU Cohesion Policy. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 31, 1868–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs-Crisioni, C.; Koomen, E. Population growth, accessibility spillovers and persistent borders: Historical growth in West-European municipalities. J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 62, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanowicka, A. Metropolitan areas in Poland-state of development and its barriers. Olszt. Econ. J. 2015, 10, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratesi, U.; Wishlade, F.G. The impact of European Cohesion Policy in different contexts. Reg. Stud. 2017, 51, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churski, P.; Żuber, P. EU Regional Policy and Its Implications for the Development of Polish Regions. In Three Decades of Polish Socio-Economic Transformations; Churski, P., Kaczmarek, T., Eds.; Economic Geography; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smętkowski, M. Wpływ polityki spójności na dyfuzję procesów rozwojowych w otoczeniu dużych polskich miast. Stud. Reg. I Lokal. 2011, 12, 123–154. [Google Scholar]

- Gorzelak, G.; Smętkowski, M. Rozwój regionalny, polityka regionalna. In Forum Obywatelskiego Rozwoju; Uniwersytet Warszawski: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, E.; Rauhut, D. Territorial Cohesion Cities: A policy recipe for achieving Territorial Cohesion? Reg. Stud. 2020, 54, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborowski, Ł. Próba przebudowy układu województw z wykorzystaniem sieci ośrodków regionalnych. Przegląd Geogr. 2016, 88, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śleszyński, P.; Bański, J.; Degórski, M.; Komornicki, T. Delimitation of problem areas in Poland. Geogr. Pol. 2017, 90, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churski, P.; Adamiak, C.; Szyda, B.; Dubownik, A.; Pietrzykowski, M.; Śleszyński, P. Nowa delimitacja miejskich obszarów funkcjonalnych w Polsce i jej zastosowanie w praktyce zintegrowanego podejścia terytorialnego (place based approach). Przegląd Geogr. 2023, 95, 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wpływ Potencjału Demograficznego i Gospodarczego Miast wojewódzkich na Kondycje Województw; Urząd Statystyczny w Warszawie, Mazowiecki Ośrodek Badań Regionalnych: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. Available online: https://warszawa.stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/warszawa/pl/defaultaktualnosci/760/7/1/1/wplyw_potencjalu_demograficznego_i_gospodarczego.pdf. (accessed on 24 April 2016).

- Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Śląskiego. Strategia Rozwoju województwa Śląskiego “Śląskie 2020+”; Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Śląskiego: Katowice, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- de Menezes, T.A.; Silveira-Neto, R.M.; Azzoni, C.R. Demography and evolution of regional inequality. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2012, 49, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Czerny, M.; Czerny, A. The challenge of spatial reorganization in a peripheral Polish region. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2002, 9, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humer, A. Linking polycentricity concepts to periphery: Implications for an integrative Austrian strategic spatial planning practice. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybyła, K.; Kachniarz, M.; Hełdak, M.; Ramsey, D.; Przybyła, B. The influence of administrative status on the trajectory of socio-economic changes: A case study of Polish cities. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2022, 30, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffner, K.; Gibas, P. Obszary funkcjonalne i ich związki z zasięgiem oddziaływania ośrodków subregionalnych (na przykładzie województwa opolskiego). Stud. Miej. 2015, 18, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śleszyński, P. Delimitacja Miejskich Obszarów Funkcjonalnych stolic województw. Przegląd Geogr. 2013, 85, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilnicki, D.; Janc, K. Obszary intensywnych powiązań funkcjonalnych miast na prawach powiatu w Polsce—Autorska metoda delimitacji. Przegląd Geogr. 2021, 93, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcińczak, S.; Bartosiewicz, B. Commuting patterns and urban form: Evidence from Poland. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 70, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, S.; Wójtowicz, M.; Gałka, J. Functional Urban Areas—Theoretical Background. In Functional Urban Areas in Poland; The Urban Book Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubownik, A.; Churski, P.; Adamiak, C.; Szyda, B. Cohesion Policy in the Struggle Against the Marginalization of the Inner Peripheries: Polish Experience and Recommendations. In Nature, Society, and Marginality: Case Studies from Nepal, Southeast Asia and Other Regions; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Cieślak, B.; Nagler, P.; van Oort, F. How administrative degradation affects middle-sized cities: Lessons from Poland’s 1998 regional reform. Reg. Stud. 2024, 58, 2518–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrzewska-Półtorak, A. Metropolization of the Polish space and its implications for regional development. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2013, 324, 167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Meijers, E.; Hoogerbrugge, M.; Cardoso, R. Beyond polycentricity: Does stronger integration between cities in polycentric urban regions improve performance? Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2018, 109, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Ketterer, T. Institutional change and the development of lagging regions in Europe. Reg. Stud. 2020, 54, 974–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diemer, A.; Iammarino, S.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. The Regional Development Trap in Europe. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 98, 487–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffner, K. Rural Labour Markets and Peripherization Processes in Poland. In Rural Areas Between Regional Needs and Global Challenges. Transformation in Rural Space; Leimgruber, W., Chang, C., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, K.; Twardzik, M. Rural Areas in Poland–Changes Since Joining the European Union. Eur. Countrys. 2022, 14, 420–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, S. Peripherie muss nicht Peripherie bleiben: Entperipherisierung am Beispiel der Region Bodensee-Oberschwaben. disP-Plan. Rev. 2012, 48, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).