Abstract

We present state-of-the-art string-based relativistic general-excitation-rank configuration interaction and coupled cluster calculations of the electron electric dipole moment, the nucleon–electron scalar-pseudoscalar, and the magnetic hyperfine interaction constants (, respectively) for the thallium atomic ground state . Our present best values are , cm], and [MHz]. The central value of the latter constant agrees with the experimental result to within 0.7% and serves as a measurable probe of the -violating interaction constants. Our findings lead to a significant reduction of the theoretical uncertainties for -odd interaction constants for atomic thallium but not to stronger constraints on the electron electric dipole moment, , or the nucleon–electron scalar-pseudoscalar coupling constant, .

1. Introduction

Electric dipole moments (EDM) of elementary particles, atoms and molecules give rise to spatial parity () and time-reversal () violating interactions [1] and are a powerful probe for physics beyond the standard model (BSM) [2]. Current single-source limits [3,4,5] on the electron EDM, for instance, can probe New Physics (NP) up to an energy scale of 1000 TeV [6] (radiative stability approach) or even greater [7], surpassing the current sensitivity of the Large Hadron Collider for corresponding sources of NP.

Until today no low-energy EDM experiment has delivered a positive result. However, the obtained EDM upper bounds are useful for constraining -violating parameters [8] of BSM models, cast as effective field theories [6,9] at different energy scales.

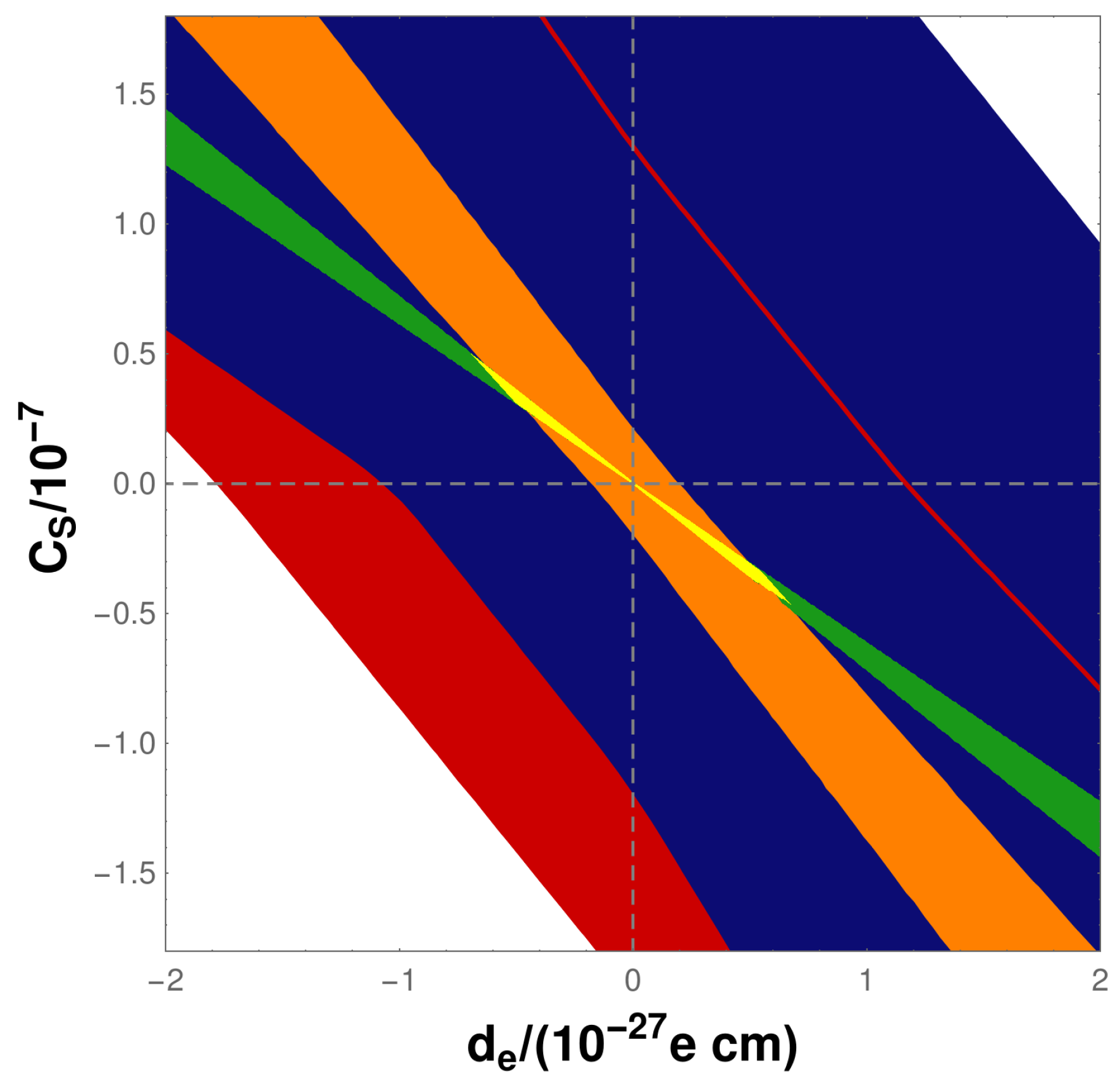

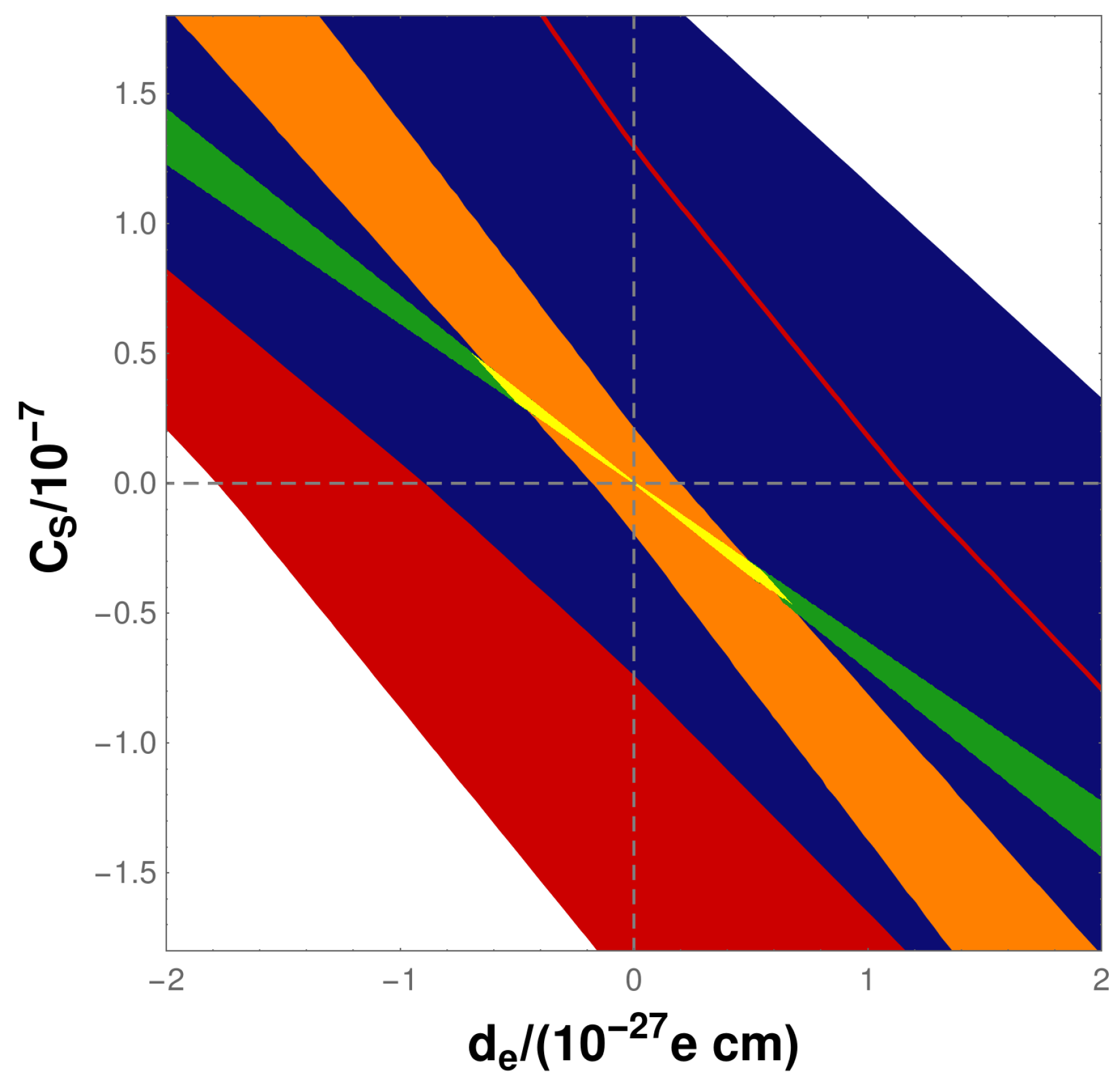

Open-shell atomic and molecular systems are particularly sensitive probes of leptonic and semi-leptonic -violation [10]. In most BSM models [11] the dominant -odd sources are the electron EDM, , and the nucleon–electron scalar-pseudoscalar (Ne-SPS) coupling, . Figure 1 (Courtesy: Martin Jung, Torino, Italy (2019)) shows the constraints (yellow surface) on and using the combined information from measurements [3,12,13,14] and calculations [4,5,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23], including the associated experimental and theoretical uncertainties, on the open-shell systems ThO (green), YbF (red; the red surface underlies the others and its extent is indicated by the thin red line), HfF (orange) and Tl (blue) through a global fit in the / plane. Results from a single system do, therefore, not constrain or individually at all in this multiple-source interpretation [24], but lead to a fan-shaped surface of allowed combinations. The width of this surface is a function of the experimental and theoretical uncertainties.

Figure 1.

Constraints on and without the results of this work. See text for details.

This means that a substantial reduction of an uncertainty for an individual system could lead to more stringent constraints on the unknown -violating parameters. The main reason for this is that the surfaces for different systems are not fully aligned, which is due to the different dependency of electron EDM and Ne-SPS atomic interactions on the electric charge of the respective heavy nuclei [25].

A substantial part of the width of the surface for the Tl atom is due to the great spread of theoretical values for the electron EDM atomic enhancement, R, calculated in the past by various groups using different electronic-structure approaches [1,19,20,21,22,23,26]. Strikingly, Nataraj et al. [22] used a high-level many-body approach, the Coupled Cluster (CC) method, and produced a value for R that strongly disagrees with the results from all other groups that have included electron correlation effects, on the order of 20%.

The purpose of this paper is two-fold:

- We use state-of-the-art relativistic Configuration Interaction (CI) and Coupled Cluster approaches for large-scale applications to determine the mentioned atomic interaction constants. Our calculations represent the most elaborate treatment of electron correlation effects to date on the discussed properties of the thallium atom ground state. We put particular emphasis on the electron EDM enhancement R and a conclusive resolution of the major discrepancy between literature values. Claims about physical effects that purportedly underlie these discrepancies are scrutinized.

- We investigate whether a reduced uncertainty for R(Tl) impacts the above-described constraints on and .

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2 we lay out the theory underlying the atomic electron EDM, Ne-SPS, and magnetic hyperfine interaction constants. Electron EDM and Ne-SPS interactions are both sensitive to electron spin density in the vicinity of the atomic nucleus. The same is true for the magnetic hyperfine interaction. For this reason, the latter is an experimentally measurable probe for the New Physics atomic interaction constants (that cannot be measured by experiment), and we thus include it in our study as a validating property. The following Section 3 contains technical details about our calculations, results, and a discussion of these results in comparison with literature values. The final Section 4 concludes on our findings.

2. Theory

An atomic EDM is defined [27] (p. 16) as

where is a -odd energy shift and is an external electric field. In atoms with nuclear spin [28] and in an electronic state with unpaired electrons, this energy shift is dominated by and originates from either the electron EDM, , or a -odd nucleon–electron (Ne) interaction, or a combination of the two [10,11]. The two cases are presented separately.

2.1. Atomic Edm Due to Electron Edm

The Hamiltonian for the interaction of the electron electric dipole moment, , is for an atomic system

where is a Dirac matrix, is a vector of spin matrices in Dirac representation, j is an electron index, the electric field at position and the bare fermion’s electric dipole moment is expressed as , necessarily linearly dependent on the particle’s spin vector [1,29].

Supposing a non-zero electron EDM , the resulting energy shift can be evaluated as

where is the field-dependent atomic wavefunction of the state in question. The expectation value in Equation (3) has the physical dimension of electric field and can be regarded as the mean interaction of each electron EDM with this field in the respective state. Following stratagem II of Lindroth et al. [30] the expectation value is recast in electronic momentum form as an effective one-body operator

where the approximation lies in assuming that is an exact eigenfunction of the field-dependent Hamiltonian of the system. This momentum-form EDM operator has already been used as early as in 1986, by Johnson et al. [26]. In the present work the field-dependent Hamiltonian is the Dirac-Coulomb Hamiltonian (in a.u., )

with weak and homogeneous, the indices run over n electrons, Z the proton number with the nucleus K placed at the origin, and are standard Dirac matrices. is not treated as a perturbation but included a priori in the variational optimization of the atomic wavefunction. Furthermore, the final results reported in this work include high excitation ranks in the correlation expansion of . For these reasons, the approximation in Equation (4) is considered very good in the present case.

The (dimensionless) atomic EDM enhancement factor is defined as . Denoting for the sake of simplicity, the enhancement factor is

The external field used in the experiment on Tl [14] was a.u. In the present work a.u. is used. This is a very small field which is well within the linear regime considering the derivative in Equation (7). The enhancement factor may under these circumstances be written as a function of two field points

We set , in which case atomic states are parity eigenstates. Since the EDM operator is parity odd, it follows that , and so

is calculated as described in reference [31]. is an approximate configuration interaction (CI) eigenfunction of the Dirac-Coulomb Hamiltonian including . Alternatively, can be calculated within the finite-field approach [32,33]. The latter has been used in coupled cluster calculations.

The electron EDM enhancement factor R is in the particle physics literature often denoted as

the atomic-scale interaction constant of the electron EDM.

2.2. Nucleon–Electron Scalar-Pseudoscalar Interaction

The effective Hamiltonian for a -odd nucleon–electron scalar-pseudoscalar interaction is written as [34]

and the resulting atomic energy shift is accordingly

where A is the nucleon number, is the S-PS nucleon–electron coupling constant, is the Fermi constant (A comment on units: Its value is . With a.u. and a.u., the Fermi constant is also expressed as a.u.) and is the nucleon density at the position of electron j. Please note that in the present work we define , whereas Flambaum and co-workers [21,25] define which explains the sign difference between the present Ne-SPS atomic interaction constants and those of Flambaum and co-workers.

Next, we define (see also reference [35]) in analogy with Equation (7) an Ne-SPS ratio (The physical dimension of the S ratio is dim dim. This is consistent with the dimension of S in the definition, Equation (13), where dim dim.)

and so one can write, using Equation (1),

and in the linear regime

The initial implementation of this expectation value in the latter expression has been described in reference [36]. The independent implementation of the matrix elements of the Hamiltonian (11) has been developed in ref. [4].

For comparison with literature results we also define the S-PS nucleon–electron interaction constant

2.3. Magnetic Hyperfine Interaction

Minimal substitution according to in the Dirac equation and the representation of the vector potential in magnetic dipole approximation as with the nuclear magnetic dipole moment leads to the magnetic hyperfine Hamiltonian

for a single point charge q at position outside the finite nucleus. Given the nuclear magnetic dipole moment vector as where is the magnetic moment in nuclear magnetons (), is the nuclear g-factor, and is the nuclear spin, Equation (17) for a single electron is written as

Based on Equation (18) we now define the magnetic hyperfine interaction constant for n electrons in the field of nucleus K (in a.u.)

where is the nuclear magneton in a.u. and is the proton rest mass. The term in the prefactor of Equation (19) is explained as follows.

The vector operator can be regarded as the component of a rank irreducible tensor operator . Application of the Wigner-Eckart Theorem to the diagonal matrix element in Equation (19) yields

where the Clebsch–Gordan coefficient is—using the general definition in Ref. [37], p. 27—evaluated as

which depends linearly on the total electronic angular momentum projection quantum number . However, the magnetic hyperfine energy must be independent of which is assured by the above prefactor . Magnetic hyperfine interaction matrix elements have been calculated based on the implementations in references [4,38] which do not make direct use of the Wigner-Eckart theorem and reduced matrix elements.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Technical Details

Gaussian atomic basis sets of double-, triple-, and quadruple- quality [39,40,41] (including correlating functions for and shells in the case of CI and cvDZ/CC) [42] have been used in the present work.

The atomic spinor basis is obtained in Dirac-Coulomb Hartree–Fock (DCHF) approximation where the Fock operator is defined by averaging over and open-shell electronic configurations.

A locally modified version of the DIRAC program package [43] has been used for all electronic-structure calculations. Interelectron correlation effects are taken into account through relativistic Configuration Interaction (CI) theory as implemented in the KRCI module [44] of DIRAC. Kramer’s unrestricted CC calculations have been carried out within the mrcc code [45,46,47]. Both implementations are based on creator-string driven algorithms and can treat expansions of general excitation rank.

The nomenclature for both CI and CC models is defined as: S, D, T, etc. denotes Singles, Doubles, Triples etc. replacements with respect to the reference determinant. The following number is the number of correlated electrons and encodes which occupied shells are included in the CI or CC expansion. In detail we have , , , , , . . The notation type S10_SD13, as an example, means that the model SD13 has been approximated by omitting Double excitations from the shells. CAS3in4 means that an active space is used with all possible determinant occupations distributing the 3 valence electrons over the 4 valence Kramers pairs. Further details about active-space-based correlation expansions are given in Ref. [36].

The use of a Kramer’s unrestricted formalism allows performance of coupled cluster calculations of the hyperfine structure constant as well as other properties considered in this paper within the finite-field approach. This method is equivalent to the analytical evaluation of energy derivatives within the Lambda-equation technique [48]. However, some additional uncertainty of the finite-field approach can be expected due to numerical differentiation. To estimate this uncertainty we have compared the values of the effective electric field acting on the electron EDM in Tl placed in the (experimental) external electric field using these two approaches at the CCSD level and cvTZ basis set. The finite-field value differs from the analytical value only by 0.02%. The advantage of the finite-field approach is that one can use CC models for which the analytical evaluation of energy derivatives is not implemented, in particular in the four-component relativistic domain.

We use the experimental value [49] for the nuclear magnetic moment of Tl with nuclear spin , [], in calculations of the magnetic hyperfine interaction constant. In all calculations the Tl nucleus is described by a Gaussian distribution for the nuclear density with exponent taken from Ref. [50].

3.2. Results for Atomic Interaction Constants

The results from the systematic study of many-body effects on atomic EDM enhancement (R), Ne-SPS interaction ratio (S) and magnetic hyperfine interaction constant (A) are compiled in Table 1. The general strategy is to first qualitatively investigate the relative importance of various many-body effects on the properties using a rather small atomic basis set. Then, in a second step, accurate models are developed that include all important many-body effects using the insight from the first step and larger atomic basis sets. Since EDM enhancement and Ne-SPS interaction ratio are analytically related [25] it is sufficient to discuss the trends for R only.

Table 1.

R, S, and A for Tl atom. By default, calculations were performed using DCHF spinors for the neutral Tl atom ( potential) and, for comparison in selected cases, with the Tl cation ( potential) and Tl cation ( potential) spinors.

3.3. Step 1: Many-Body Effects in cvDZ Basis

3.3.1. Valence Electron Correlation

The result of for CAS1in3 which is a singles CI expansion for the electronic ground state can be regarded as close to a DCHF result. The Full CI (FCI) result including only the three valence electrons (CAS3in4_SDT3/60au) of shows that valence correlation effects lead to a considerable change by more than 25% (in the large cvQZ basis by more than 35%). The valence FCI enhancement in cvQZ basis of is, therefore, a benchmark. This value is closely reproduced using the universal basis set of reference [22]. Further effects can be considered to be modifications of this benchmark result and will be studied one by one.

3.3.2. Subvalence Electron Correlation

Subvalence electrons of the Tl atoms are those occupying the , , and shells. All other electrons will be considered core electrons. Correlations among the electrons and in particular of the and the valence electrons lead to a strong decrease of R, on the absolute, on the order of 10% (for instance, compare models SD10_CAS3in4_SD13 and CAS3in4_SD3). Corresponding contributions from the and electrons are significantly smaller (compare SD18_CAS3in4_SD21 with SD10_CAS3in4_SD13).

3.3.3. Outer-Core Electron Correlation

Outer-core-valence correlations have been evaluated by allowing for one hole in the respective outer core spinors along with excitations from the subvalence and valence electrons (compare, for instance, S8_SD18_CAS3in4_SDT29 with SD18_CAS3in4_SDT21). In sum for the shells with effective principal quantum number these effects amount to about %.

3.3.4. Effect of Higher Excitation Ranks

Allowing for three holes in the shells with effective principal quantum number and up to four particles in the virtual spinors (i.e., adding combined quadruple excitations) leads to a total change of around %. Of particular importance are triple excitations into the virtual space, compare models SD18_CAS3in4_SDT21 and SD18_CAS3in4_SD21.

3.4. Step 2: Accurate CI Results

Subsets of important CI models based on the findings of the previous subsection have been repeated using the larger atomic basis sets, cvTZ and cvQZ. The single best values from these calculations are given by the model SD18_CAS3in4_SDT21/35au. These latter values V are then corrected by a “correction shift”, calculated as follows (all corrections using cvDZ basis):

The final best CI values are obtained by adding the above sum of individual corrections to the value from the model SD18_CAS3in4_SDT21/35au.

3.5. Accurate CC Results

Table 2 gives values of R, S and (Tl) constants obtained within the all-electron coupled cluster with single, double and non-iterative triple cluster amplitudes, CCSD(T), method employing several basis sets. One can see a good convergence of the results in the series of the Dyall’s DZ, TZ and QZ basis sets: values of R obtained within the QZ and TZ basis sets differ by about 2%. Table 2 also gives values of the constants obtained within the Nataraj’s universal basis set [22]. Please note that the latter basis set is the even-tempered basis set (geometry progression). One can see a good agreement of the results obtained within the QZ basis set and Nataraj’s universal basis set.

Table 2.

R, S, and A for Tl atom calculated within the 81e-CCSD(T) method in different basis sets. In the case denoted “” the atomic spinors are obtained for the neutral Tl atom and the external field perturbs both the spinor coefficients and the CC amplitudes. In the case denoted “” the atomic spinors are obtained for the Tl cation and the external electric field only perturbs the CC amplitudes but not the atomic spinors.

Table 3 gives values of R calculated with different number of correlated electrons. As can be seen contributions from subvalence and outer-core electrons are close to those obtained within the CI approach above.

Table 3.

R for Tl atom calculated within the CCSD(T) method in Dyall’s cvQZ basis set.

To check the convergence with respect to electron correlation effects we performed a series of successive 21-electron coupled cluster calculations within the TZ basis set (see Table 4). In these calculations two sets of atomic bispinors were used. The first one was obtained within the DCHF approximation where the Fock operator is defined by averaging over and open-shell electronic configurations as in the CI case above. The second one was obtained within the closed-shell DCHF method for the Tl cation. One can see that CC values gives almost identical result for each set at any level. Moreover, the contribution of correlation effects beyond the CCSD(T) model is almost negligible in the considered case. We considered models up to coupled cluster with Single, Double, Triple and perturbative Quadruple cluster amplitudes, CCSDT(Q).

Table 4.

Values of R calculated at different level of theory with correlation of 21 electrons of Tl, cvTZ basis set. Calculations were performed using DCHF spinors for the neutral Tl atom ( potential) and for the Tl cation ( potential) cases. In both cases the external field perturbs both the spinor coefficients and the CC amplitudes.

Contribution of the effect of the Breit interaction on R has been estimated in reference [23] as 0.36%. Based on the uncertainties discussed above we conservatively estimate the uncertainty of our final CC value for R to be less than 5%. For CI the expected residual uncertainties for basis set, inner-core correlations, and inclusion of higher excitation ranks have been added to obtain a final total uncertainty of 6%.

3.6. Discussion in Comparison with Literature Results

Our present best results are shown in Table 5 in comparison with previous work. The earlier controversy between different groups over results for R(Tl) can be condensed into three main points which we address one by one.

Table 5.

Comparison with Literature Values.

3.6.1. Basis Sets

From the results in Table 1 and Table 2 it is evident that a large atomic basis set, at least of quadruple-zeta quality, must be used for obtaining very accurate interaction constants. The results in Table 1 and Table 2 obtained with our correlation methods demonstrate that the basis set used by Nataraj et al., in ref. [22] fulfills this requirement, yielding interaction constants that are very close to those obtained with Dyall’s cvQZ basis set and the same correlation expansion. The earlier suggestion of Porsev et al., about an inadequate basis set used in ref. [22] can, therefore, be excluded as a possible reason for the outlier result in ref. [22].

3.6.2. Treatment of Correlation Effects by the Many-Body Method

It is claimed in reference [22] that the treatment of electron correlation effects was more complete than in references [20,21]. We have therefore first attempted to reproduce the electron EDM enhancement calculated by Nataraj et al., by using the same many-body Hamiltonian and EDM operator, the same atomic basis set (“Nataraj universal”) and the same method, CCSD(T). A persisting difference with the approach of Nataraj et al., is the use of CC amplitudes for the closed shells of neutral Tl (our case) or the closed shells of the singly ionized Tl (Nataraj case). These results are shown in Table 2 under the label “”. Our calculation of the hyperfine constant [MHz] reproduces the value of Nataraj et al., which is [MHz] almost precisely (residual difference of less than %). However, using the same wavefunction we obtain which differs from the value of Nataraj et al., by 17%. Our CC result for R is in accord with similar calculations using the large cvQZ basis set, in accord with the present best CI result ( which after correction for core correlations from the innermost 28 electrons, according to the results in Table 3, becomes ) and in good agreement with the best results of Liu et al., [20], Dzuba et al. [21], and Porsev et al. [23], see Table 5. The correct evaluation of the electron EDM enhancement in our codes has been assured by comparative tests of the independent implementations of present CI and CC, as well as with the DIRRCI module [31,58] in the DIRAC program package. All three independent implementations produce the same values of R for small test cases using Full CI/Full CC expansions. These findings strongly suggest that the CC wavefunctions used by us and by Nataraj et al., are almost identical, but that there is a problem in the evaluation of R in reference [22].

Since correlation effects have been treated at a very similar (but physically more accurate) level in the present work as in ref. [22] and the result is very different, the claim of correlation effects being responsible for the large difference between previous results is untenable.

3.6.3. Use of , , and Potentials

First, given a fixed atomic basis set and a fixed many-body Hamiltonian (In the present and previous works the Dirac-Coulomb picture is employed where negative-energy states are implicitly or explicitly excluded from the orbital/spinor space which is used as a basis for the many-body expansion.), the Full CI expansion delivers the exact solution in the N-particle sector of Fock space [59], independent of the orbital/spinor basis used for this Full CI expansion. This implies that a many-body expansion that closely approximates the Full CI expansion, such as CCSDT or CCSDT(Q), must also be nearly independent of the employed Dirac-Fock potential.

Our results in Table 4 clearly confirm this conjecture and demonstrate that even in the more approximate CCSD expansion the electron EDM enhancement factor R is almost independent (% difference) of the underlying spinor set. As the many-body expansion becomes more approximate, such as in the CI model SD18_CAS3in4_SD21 (see Table 1) basic theory leads us to expect that the difference in R should increase which is indeed the case (roughly 2% difference). Adding external Triple excitations to the CI expansion, model SD18_CAS3in4_SDT21, quenches the difference to a mere %, again in accord with expectation. Even the use of a potential (i.e., spinors optimized for the Tl system) changes R by less than 3% relative to spinors for the neutral atom in the SD18_CAS3in4_SDT21 model. This difference is expected to be even smaller in CC models.

Despite the unimportance of the employed spinor set in highly correlated calculations, we have used the physically most accurate spinors for the neutral Tl atom in obtaining our best final results. The ratios of our calculated -odd interaction constants are (CI) and (CC) which agree well with the analytical value of Dzuba et al. [25] of (an.) . The validity of this analytical relationship has been confirmed numerically in numerous electronic-structure studies of EDM enhancements and Ne-SPS interactions on other systems, for instance in Refs. [17,18,60,61,62,63,64,65].

4. Conclusions

In the present study we have carried out a systematic and elaborate treatment of electron correlation effects for the -violating and magnetic hyperfine interaction constants of atomic Tl. This present treatment of electron correlation effects surpasses the one by Nataraj et al., in ref. [22] in that we include higher CC excitation ranks in the wavefunction expansion. Our findings recommend excluding the result of Nataraj et al., from the dataset used to constrain the -odd parameters and . Likewise, the result by Sahoo et al. [54] (see Table 5) – presumably obtained with a similar code as R(Tl) by Nataraj et al., – is also to a great degree too small. Our CC ratio for the eEDM and Ne-SPS interaction constants differs from the analytical ratio developed by Dzuba et al. in Refs. [25] by 7.1%. This is within the combined uncertainties of the analytical/numerical approaches used for this comparison. Both the results of Nataraj et al., and Sahoo et al., being too small, the last test is a check for internal consistency of the ratio for those two interaction constants. That ratio amounts to (CC Nataraj/Sahoo) which deviates from the analytical ratio by 30%, so those two results are even inconsistent with each other.

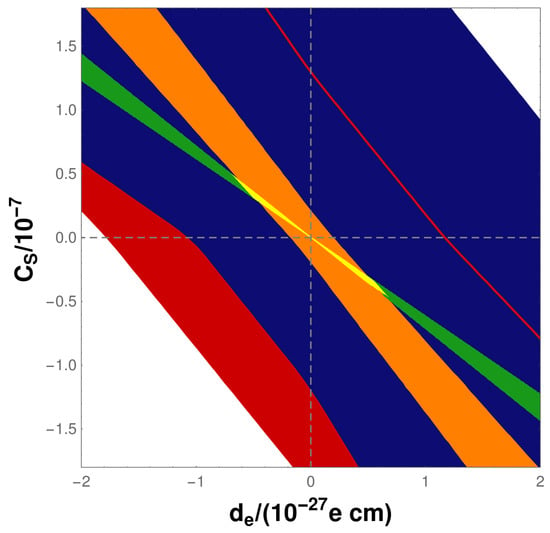

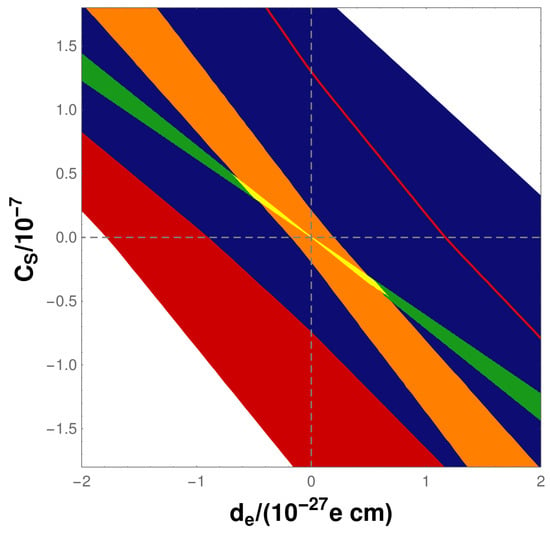

Figure 2 displays the updated version of the global fit shown in the introduction, using the dataset of reliable calculations of and for the Tl atom. The strongly reduced uncertainty of atomic interaction constants for Tl leads to a discernable shrinking of the associated parameter surface (blue), but does not lead to modified constraints. The essential reason for this is the extremely high sensitivity of the experiments on ThO (green) and HfF (orange) and the fact that the surface for Tl is too well aligned with the surfaces for these latter two molecules. However, tighter constraints on and can be obtained by including experimental and theoretical results for closed-shell atomic systems as discussed in ref. [66].

Figure 2.

Constraints on and including the results of this work. See text for details.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.F.; Investigation, T.F. and L.V.S.; Methodology, T.F. and L.V.S.; Resources, T.F. and L.V.S.; Software, T.F. and L.V.S.; Writing— original draft, T.F. and L.V.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The CC research was funded by Russian Science Foundation Grant No. 19-72-10019.

Acknowledgments

We thank Martin Jung (Torino) for providing updated plots and for helpful discussions. Huliyar Nataraj is thanked for sharing many technical details of his calculations with us. Electronic structure calculations were partially carried out using resources of the collective usage center Modeling and predicting properties of materials at NRC “Kurchatov Institute” – PNPI.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Khriplovich, I.B.; Lamoreaux, S.K. CP Violation Without Strangeness; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, J.; Ramsey-Musolf, M.J.; van Kolck, U. Electric dipole moments of nucleons, nuclei, and atoms: The Standard Model and beyond. Prog. Part. Nuc. Phys. 2013, 71, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, V.; Hutzler, N.R. Improved limit on the electric dipole moment of the electron. Nature 2018, 562, 355. [Google Scholar]

- Skripnikov, L.V. Combined 4-component and relativistic pseudopotential study of ThO for the electron electric dipole moment search. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 145, 214301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, M.; Fleig, T. In search of discrete symmetry violations beyond the standard model: Thorium monoxide reloaded. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 145, 028645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesarotti, C.; Lu, Q.; Nakai, Y.; Parikha, A.; Reece, M. Interpreting the electron EDM constraint. J. High Energy Phys. 2019, 5, 059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekens, W.; de Vries, J.; Jung, M.; Vos, K.K. The phenomenology of electric dipole moments in models of scalar leptoquarks. J. High Energy Phys. 2019, 069, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chupp, T.; Ramsey-Musolf, M. Electric dipole moments: A global analysis. Phys. Rev. C 2015, 91, 035502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirigliano, V.; Ramsey-Musolf, M.J.; van Kolck, U. Low energy probes of physics beyond the standard model. Prog. Part. Nuc. Phys. 2013, 71, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pospelov, M.; Ritz, A. Electric dipole moments as probes of new physics. Ann. Phys. 2005, 318, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.M. T- and P-odd electron-nucleon interactions and the electric dipole moments of large atoms. Phys. Rev. D 1992, 45, 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, D.M.; Smallman, I.J.; Hudson, J.J.; Sauer, B.E.; Tarbutt, M.R.; Hinds, E.A. Measurement of the electron’s electric dipole moment using YbF molecules: Methods and data analysis. New J. Phys. 2013, 14, 103051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairncross, W.B.; Gresh, D.N.; Grau, M.; Cossel, K.C.; Roussy, T.S.; Ni, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, J.; Cornell, E.A. Precision measurement of the electron’s electric dipole moment using trapped molecular ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 153001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regan, B.C.; Commins, E.D.; Schmidt, C.J.; DeMille, D. New Limit on the Electron Electric Dipole Moment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 071805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunaga, A.; Abe, M.; Hada, M.; Das, B.P. Relativistic coupled-cluster calculation of the electron-nucleus scalar-pseudoscalar interaction constant WS in YbF. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 93, 042507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, M.; Gopakumar, G.; Hada, M.; Das, B.P.; Tatewaki, H.; Mukherjee, D. Application of relativistic coupled-cluster theory to the effective electric field in YbF. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 90, 022501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skripnikov, L.V. Communication: Theoretical study of HfF+ cation to search for the T,P-odd interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 147, 021101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleig, T. -odd and magnetic hyperfine-interaction constants and excited-state lifetime for HfF+. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 96, 040502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mårtensson-Pendrill, A.M.; Lindroth, E. Limit on a P- and T-Violating Electron-Nucleon Interaction. Eurphys. Lett. 1991, 15, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.W.; Kelly, H.P. Analysis of atomic electric dipole moment in thallium by all-order calculations in many-body perturbation theory. Phys. Rev. A 1992, 45, R4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzuba, V.A.; Flambaum, V.V. Calculation of the (T,P)-odd electric dipole moment of thallium and cesium. Phys. Rev. A 2009, 80, 062509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nataraj, H.S.; Sahoo, B.K.; Das, B.P.; Mukherjee, D. Reappraisal of the Electric Dipole Moment Enhancement Factor for Thallium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 200403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porsev, S.G.; Safronova, M.S.; Kozlov, M.G. Electric Dipole Moment Enhancement Factor of Tl. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 173001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, M. A robust limit for the electric dipole moment of the electron. J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 5, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzuba, V.A.; Flambaum, V.V.; Harabati, C. Relations between matrix elements of different weak interactions and interpretation of the parity-nonconserving and electron electric-dipole-moment measurements in atoms and molecules. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 052108, Erratum ibid, 2012, 85, 029901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.R.; Guo, D.S.; Idress, M.; Sapirstein, J. Weak-interaction effects in heavy atomic systems. II. Phys. Rev. A 1986, 34, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commins, E.D. Electric Dipole Moments of Leptons. Adv. Mol. Opt. Phys. 1999, 40, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sushkov, O.P.; Flambaum, V.V.; Khriplovich, I.B. Possibility of investigating P- and T-odd nuclear forces in atomic and molecular experiments. Sov. Phys. JETP 1984, 60, 873. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, L.R. Tests of Time-Reversal Invariance in Atoms, Molecules, and the Neutron. Science 1991, 252, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindroth, E.; Lynn, B.W.; Sandars, P.G.H. Order α2 theory of the atomic electric dipole moment due to an electric dipole moment on the electron. J. Phys. B 1989, 22, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleig, T.; Nayak, M.K. Electron electric-dipole-moment interaction constant for HfF+ from relativistic correlated all-electron theory. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 88, 032514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skripnikov, L.V.; Maison, D.E.; Mosyagin, N.S. Scalar-pseudoscalar interaction in the francium atom. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 022507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skripnikov, L.V.; Titov, A.V.; Petrov, A.N.; Mosyagin, N.S.; Sushkov, O.P. Enhancement of the electron electric dipole moment in Eu2+. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 84, 022505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flambaum, V.V.; Khriplovich, I.B. New bounds on the electric dipole moment of the electron and on T-odd electron-nucleon coupling. Sov. Phys. JETP 1985, 62, 872. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, A.; Das, B.P.; Andriessen, J. Relativistic many-body calculation of the electric dipole moment of atomic rubidium due to parity and time-reversal violation. Phys. Rev. A 1994, 50, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denis, M.; Nørby, M.; Jensen, H.J.A.; Gomes, A.S.P.; Nayak, M.K.; Knecht, S.; Fleig, T. Theoretical study on ThF+, a prospective system in search of time-reversal violation. New J. Phys. 2015, 17, 043005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissbluth, M. Atoms and Molecules; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA; San Francisco, CA, USA; London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fleig, T.; Nayak, M.K. Electron electric dipole moment and hyperfine interaction constants for ThO. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 2014, 300, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyall, K.G. Relativistic and nonrelativistic finite nucleus optimized double zeta basis sets for the 4p, 5p and 6p elements. Theoret. Chem. Acc. 1998, 99, 366. [Google Scholar]

- Dyall, K.G. Relativistic and nonrelativistic finite nucleus optimized triple-zeta basis sets for the 4p, 5p and 6p elements. Theoret. Chem. Acc. 2002, 108, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyall, K.G. Relativistic double-zeta, triple-zeta, and quadruple-zeta basis sets for the 4p, 5p and 6p elements. Theoret. Chim. Acta 2006, 115, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyall, K.G. Core correlating basis functions for elements 31-118. Theoret. Chim. Acta 2012, 131, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, H.J.A.; Bast, R.; Saue, T.; Visscher, L.; Bakken, V.; Dyall, K.G.; Dubillard, S.; Ekström, U.; Eliav, E.; Enevoldsen, T. DIRAC, a Relativistic ab Initio Electronic Structure Program, Release DIRAC16 (2016). Available online: http://www.diracprogram.org (accessed on 25 February 2020).

- Knecht, S.; Jensen, H.J.A.; Fleig, T. Large-Scale Parallel Configuration Interaction. II. Two- and four-component double-group general active space implementation with application to BiH. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 014108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kállay, M.; Rolik, Z.; Ladjánszki, I.; Szegedy, L.; Ladóczki, B.; Csontos, J.; Kornis, B.; Rolik, Z. mrcc, a quantum chemical program suite. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 135, 104111. Available online: www.mrcc.hu (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Kállay, M.; Surján, P.R. Higher excitations in coupled-cluster theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 115, 2945–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kállay, M.; Szalay, P.G.; Surján, P.R. A general state-selective multireference coupled-cluster algorithm. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kállay, M.; Gauss, J.; Szalay, P. Analytic first derivatives for general coupled-cluster and configuration interaction models. J. Chem. Phys. 2003, 119, 2991. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, N.J.; (IAEA Nuclear Data Section Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 100, 1400 Vienna, Austria). Table of Nuclear Magnetic Dipole and Electric Quadrupole Moments; INDC International Nuclear Data Committee: Vienna, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Visscher, L.; Dyall, K.G. Dirac-Fock Atomic Electronic Structure Calculations using Different Nuclear Charge Distributions. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 1997, 67, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flambaum, V.V. To the question of electric-dipole moment enhancement in heavy atoms. Sov. J. Nucl. Phys. 1976, 24, 199. [Google Scholar]

- Kraftmakher, A.Y. On the Hartree-Fock calculation of the electron electric dipole moment enhancement factor for the thallium atom. J. Phys. B 1988, 21, 2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, A.C.; Lindroth, E.; Mårtensson-Pendrill, A.M. Parity non-conservation and electric dipole moments in caesium and thallium. J. Phys. B 1990, 23, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, B.K.; Das, B.P.; Chaudhuri, R.; Mukherjee, D.; Venugopal, E.P. Atomic electric-dipole moments from higgs-boson-mediated interactions. Phys. Rev. A 2008, 78, 010501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, M.G.; Porsev, S.G.; Johnson, W.R. Parity nonconservation in thallium. Phys. Rev. A 2001, 64, 052107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grexa, M.; Hermann, G.; Lasnitschka, G.; Fricke, B. Hyperfine structure and isotopic shift of the n2PJ levels (n = 7–10) of 203,205Tl measured by Doppler-free two-photon spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. A 1998, 38, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurio, A.; Prodell, A.G. Hfs Separations and Hfs Anomalies in the 2P12 state of Ga69, Ga71, Tl203 and Tl205. Phys. Rev. 1956, 101, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visscher, L.; Saue, T.; Nieuwpoort, W.C.; Fægri, K.; Gropen, O. The electronic structure of the PtH molecule: Fully relativistic configuration interaction calculations of the ground and excited states. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 99, 6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgaker, T.; Jørgensen, P.; Olsen, J. Molecular Electronic Structure Theory; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sasmal, S.; Pathak, H.; Nayak, M.K.; Vaval, N.; Pal, S. Search for parity and time reversal violating effects in HgH: Relativistic coupled-cluster study. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 144, 124307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasmal, S.; Talukdar, K.; Nayak, M.K.; Vaval, N.; Pal, S. Electron–nucleus scalar–pseudoscalar interaction in PbF: Z-vector study in the relativistic coupled-cluster framework. Mol. Phys. 2017, 115, 2807–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleig, T. TaO+ as a candidate molecular ion for searches of physics beyond the standard model. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 022504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaul, K.; Berger, R. Ab initio study of parity and time-reversal violation in laser-coolable triatomic molecules. Phys. Rev. 2018, 101, 012508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, K.; Nayak, M.K.; Vaval, N.; Pal, S. Relativistic coupled-cluster investigation of parity (p) and time-reversal (t) symmetry violations in HgF. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 084304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazil, N.M.; Prasannaa, V.S.; Latha, K.V.P.; Abe, M.; Das, B.P. RaH as a potential candidate for electron electric-dipole-moment searches. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 99, 052502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleig, T.; Jung, M. Model-independent determinations of the electron EDM and the role of diamagnetic atoms. J. High Energy Phys. 2018, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).