Abstract

Model building in , which is the leading grand unification framework, often involves large Higgs representations and their couplings. Explicit calculations of such couplings is a multi-step process that involves laborious calculations that are time consuming and error prone, an issue which only grows as the complexity of the coupling increases. Therefore, there exists an opportunity to leverage the abilities of computer software in order to algorithmically perform these calculations on demand. This paper outlines the details of such software, implemented in C++ using in-built libraries. The software is capable of accepting invariant couplings involving an arbitrary number of Higgs tensors, each having up to five indices. The output is then produced in LaTeX, so that it is universally readable and sufficiently expressive. Through the use of this software, coupling analysis can be performed in a way that minimizes calculation time, eliminates errors, and allows for experimentation with couplings that have not been computed before in the literature. Furthermore, this software can be expanded in the future to account for similar Higgs–Spinor coupling analysis, or extended to include further invariant couplings.

1. Introduction

The standard model of particle physics, including the strong and electroweak interactions comprising the group , is highly successful [1,2,3,4,5]. One of the important challenges for particle physicists is to determine the underlying scheme where these forces are all unified. The aim of grand unified theories is three-fold: (1) To accomplish these unifications; (2) to provide an understanding of the three generations of quarks and leptons; (3) to provide an explanation of the hierarchy of their masses and of other properties. A more ambitious goal is to extend these ideas to encompass gravity, which requires the framework of superstring theory.

Grand unified models based on the gauge group [6,7] have the most desirable features. They provide a framework for the unification of electroweak and strong interactions. They also allow for all the quarks and leptons of one generation to reside in a single –plet irreducible spinor representation. Additionally, this complex representation contains a right-handed singlet state, needed for the generation of neutrino masses via the seesaw mechanism. models also solve—in a relatively natural way—the doublet-triplet splitting problem without fine tuning. Next, they possess gauge interactions that conserve parity. are aslo free from all gauge anomalies. Supersymmetric models have the additional feature that they manage to unify the gauge couplings, and solve the hierarchy problem.

The Higgs sector of models is largely unconstrained consisting of numerous possible representations. An avenue to the computation of the couplings is via the decomposition of these in terms of invariant couplings and then the further decomposition of them in terms of the invariant couplings. The formalism to accomplish this was carried out in [8,9,10,11]. However, the explicit analyses of the couplings can be laborious and time consuming. For instance the complexity of computation involving large Higgs representations can be seen in the works of [12,13,14]. Thus various models employ elaborate Higgs representations to break the grand unified theory (GUT) symmetry down to the Standard Model (SM) gauge group . These consist of both small and large Higgs representations of such as and . This enormous freedom of choosing symmetry breaking patterns allows one to construct models with natural splitting of Higgs doublets and Higgs triplets to accomplish electroweak symmetry breaking [12,13,14,15] and models with a one-scale breaking of GUT symmetry [16,17,18,19,20]. However, there are restrictions on the Higgs content of a GUT model, such as the strict proton decay limits [21,22]. There are two commonly used symmetry breaking paths: One through the maximal subgroup [8,9,10,11,23,24] and the other through the maximal subgroup [25,26].

The Higgs-Higgs interactions, appearing in supersymmetric and non-supersymmetric models, are necessary to break the GUT and electroweak symmetries. Additionally, a thorough study of higher dimensional operators arising from three point, four point and higher Higgs-Higgs Interactions and matter-Higgs interactions is necessary to explore physics beyond the SM. For example, from matter-Higgs interactions, a top-down approach [14] has been used to find dimension five, seven and nine operators within the supersymmetric grand unification framework. This is in stark contrast to the bottom-up approach that exists prominently in the literature. These violating operators are important in the investigation of seesaw neutrino masses, baryogenesis, proton decay and oscillations.

In this paper, we use the techniques (see Appendix B.4) developed in [8,9,11] for the analysis of such invariant interactions which allows a full exhibition of the invariant content of tensor representations. In particular, in this paper, we focus on the analytic determination of tensor interactions in terms of irreducible fields. It would then be very straightforward to expand all the invariants in terms of SM group invariants using the particle assignments. We wish to point out that our approach here is field theoretic rather than group theoretic [27,28] or other technique [29,30]. Our method is specially suited for the computation of tensor couplings.

Manually preforming such tensor calculations can be a time-consuming endeavor that can very easily lead to errors. There are numerous intermediate calculations, each posing the risk of making an error, which may propagate throughout, affecting the final result. Therefore, there exists a compelling argument to use computer software to perform these calculations automatically, as proposed in this paper.

This C++ program allows users to perform Higgs-Higgs coupling calculations rapidly and automatically, reducing the time needed to complete them and eliminating calculation errors.

With this program, the user is able to enter a coupling via a simple text-based interface. Next, the user is provided with the final normalized output, in a LaTeX format, which can easily be added to a user’s publication. Further, the user is allowed to enter an arbitrary number of tensors in an invariant and can name their indices and tensors as needed. The maximum number of indices a single tensor can have is 5.

Furthermore, to ensure the correctness of the algorithm when applied to couplings not previously attempted in the literature, manual hand calculations were evaluated for certain terms and were successfully matched to the program output.

This program can be easily extended to account for Higgs–Spinor couplings [31], as well as other couplings.

The code is available to download https://github.com/AHB99/tensor-coupling-program/releases (accessed on 13 September 2021).

There exists a variety of software packages for Lie algebra related computations used in grand unified models that are based on various classical and exceptional groups. Here are some examples. LieART 2.0 [32] uses a Mathematica library to perform various computations such as tensor product decomposition and subalgebra branching of irreducible representations. SARAH 4 [33] also exploits a Mathematica library that carries out calculations used in the study of supersymmetric and non-supersymmetric grand unified models, particularly, the full two-loop renormalization group equations for a supersymmetric theory. CleGo [34] package uses OCaml programming language to determine Clebsch–Gordan coefficients of irreducible tensor product representations of Lie algebras . FeynRules 2.0 [35] is a Mathematica package that derives Feynman rules from the Lagrangian of the Standard Model, Minimal Supersymmetric Standard model and their numerous extensions. These software packages rely extensively on standard group theoretic methods and display different degrees of generality. As mentioned earlier, our C++ code uses the more intuitive field theoretic formalism for the analytic decomposition of the invariants of arbitrary order in terms of invariants exhibiting their precise tensorial structure and Clebsch–Gordan coefficients. Our computer program is complementary to the existing software packages.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 contains a detailed breakdown of the computer algorithm to provide readers with an overview of how the code is designed. Section 3 provides sample calculation output and Section 4 discusses the significance of our algorithm. To fully appreciate and understand the properties associated with the groups, we provide a thorough presentation of these groups in the appendices. Specifically, we discuss vector and tensor representations of group and aspects of gauge theory in Appendix A. group algebra in basis, branching rules for into irreducible representations and its specialization to case are explained in Appendix B. We show explicitly the technique to decompose tensor invariants in terms of tensor invariants in Appendix B.4. This technique (The Basic Theorem) uses a unique set of reducible tensors in terms of which the invariants have a straight forward decomposition. The Basic Theorem is specially useful for couplings involving large tensor representations and is central to the computation of any invariant couplings. tensors expressed in terms of irreducible tensors with canonically normalized kinetic energy terms are exhibited in Appendix B.5. In Appendix B.6, we identify singlets, doublets and triplets in fields.

2. Materials and Methods

The program evaluates tensor couplings from input to their final normalized form. Internally, it is executed through various functions of the Product Resolver class, which stores all the intermediate terms during the calculation. It is based on the algorithm developed in Appendix B.4.

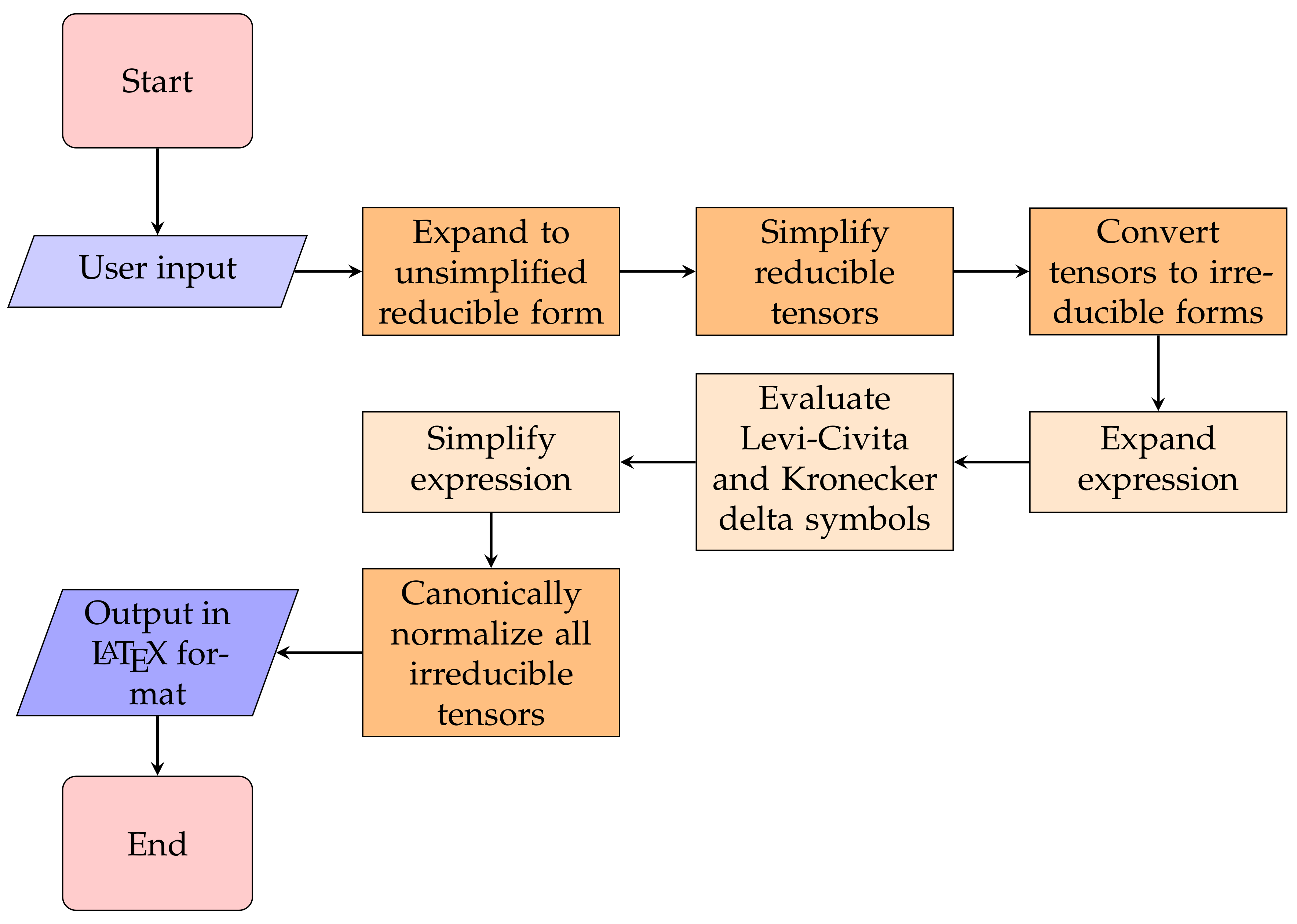

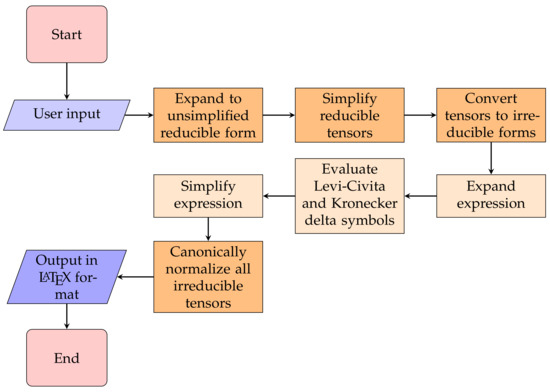

In brief, first the user inputs the original tensor coupling. This coupling is expanded to all its unsimplified reducible tensor terms. Then, all the reducible tensor terms are simplified by reordering the indices, accounting for anti-symmetry, and renaming indices if valid. Next, each reducible tensor term is substituted for its corresponding irreducible tensor expression. This expression is then expanded out fully. All Levi-Civita tensors are evaluated, following which the expression is simplified using the Kronecker Deltas and further properties of irreducible tensors. Then, all simplified irreducible tensor terms are further simplified by renaming if valid. Finally, these terms are substituted for their related normalized tensor term expressions, and the final expression is determined, to be output in LaTeX format. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing the breakdown of the computer algorithm to compute tensor invariants.

2.1. Input Phase

The user inputs a tensor coupling in the format “X_{/i/j/k}Y_{/i/j/k}…” where “X” and “Y” are labels for tensors and “/i/j/k” are labels for index names. The input is parsed using the standard C++ regex library. A regex expression is hard-coded to tokenize the tensors and the indices each. The Product Resolver class uses the following method:

2.2. Generation Phase

All the initial generated reducible tensor terms can be determined by the following pattern. If one were to take a binary number where each binary digit corresponds to each unique index of the input tensor, and then increment the binary number from 0 to (where n is the number of unique indices), each binary number would correspond to a generated term. A term can be developed by the rule where for each binary digit, the corresponding index in that position will have its first occurrence barred if the binary digit is 1, or unbarred if it is 0. The function is as follows:

2.3. Simplification of Reducible Tensor Term Expression Phase

Now we have all the raw, generated reducible tensor terms, we may simplify them. This phase is based on the idea of tensor terms having similar “structure”. Two terms have the same “structure” if, assuming they have the same number of tensors, every tensor in every corresponding position has the same label and number of barred and unbarred indices. Only once two tensor terms have the same “structure” can the possibility of a rename operation leading to equality between them be considered. Currently, the generated tensor terms have their indices unordered, with no grouping of barred and unbarred indices. So firstly, each reducible tensor term has its indices reordered, accounting for anti-symmetry, by the below algorithm. The function is as follows:

2.3.1. Reordering of Reducible Tensor Term Indices

The algorithm is a modified implementation of bubble sorting, accounting for grouping of barred/unbarred indices, as well as anti-symmetry, acting on each Tensor. By the end, the tensors will have their barred indices grouped to the left, and unbarred indices grouped to the right, with each group ordered in ascending order of index names.

2.3.2. Sorting Tensor Terms

The tensor terms need to now be sorted in a uniform manner so that it becomes obvious to identify terms with the same “structure”, as defined above. We require sorting to be done first by tensor labels (alphabetically), then by number of indices, and then by number of barred indices

After sorting, the tensor terms are transferred to a separate container of simplified reducible tensor terms, checking to see if an addition or rename operation can be done with any existing simplified term first. The rename operation is detailed below

2.3.3. Renaming of Reducible Tensor Term Indices (Ignoring Commutativity) Algorithm

The algorithm takes two tensor terms, an Attempt Term that we are will be manipulating and renaming, as well as a Source Term, which will not be modified and is what the Attempt Term will be manipulated to match, if possible. It outputs a Renamed Term if the operation was successful, that, once its indices are reordered, will be identical to the Source Term (excluding coefficients, which are to be added). Moreover, the algorithm makes use of the concept of “zones”, which are either unbarred or barred groups of indices in a tensor. Tensor terms with the same “structure” will also have the same “zones”, and hence when deciding whether a rename operation is possible, we only have to focus on mapping each “zone” of the Attempt Term to the Source Term.

The algorithm assumes the Source Term and Attempt Term have their indices grouped as barred/unbarred and each group is ordered ascendingly, and that their tensors are sorted. The handling of commutativity, for tensor terms that retain identical structure upon permutations, is not considered in this algorithm.

2.3.4. Renaming of Reducible Tensor Term Indices (Accounting for Commutativity) Algorithm

This algorithm deals with the concept of “ambiguity” of tensor terms. This is a characteristic of a tensor term where it is possible to permute the ordering of the tensors within the term (due to the commutativity of tensors) and still retain identical “structure” (as defined above). This requires special consideration as the above Renaming Algorithm focuses on trying to equate corresponding “zones” in the Source and Attempt Terms based on position, so when such permutations are possible, the algorithm may fail to find a legal rename mapping for one arbitrary permutation while it may have been possible in another.

Hence, we need to exhaust every single possible permutation of “ambiguous” tensor terms. Specifically, we deal with the concept of “ambiguous zones”, which are groups of tensors within a tensor term that cause the “ambiguity” property (there can be multiple “ambiguous zones” within a single tensor term)

Ambiguity Detection:

During the rename operation, if a Source Term (and hence it’s matching structure Attempt Term) is found to be ambiguous, then we must generate all possible permutations of the ambiguous zones of the Attempt Term, attempt to rename them to the Source Term, and if even 1 successful rename exists, that must be chosen and applied. Only failing this do we conclude no possible rename exists. To generate all these permutations of the Attempt Term, we first must locate all such zones.

Finding all ambiguous zone locations and sizes:

Once we have the locations and sizes of all ambiguous zones of a tensor, we can generate all the permutations of the locations of all the ambiguous zones. This will be stored in a vector (the overall container) of vectors (for each zone) of vectors (for each permutation) of integers (the locations). For uniformity, we will consider each zone’s locations start from 0, and offset it with the actual location later.

Finding all permutations of the locations for all ambiguous zones:

Now, given this information, we can generate the tensor terms. However, we must consider the fact that for tensor terms with multiple ambiguous zones, we must generate all combinations of all the possible permutations of the ambiguous zones. For example, if a tensor term has 2 ambiguous zones, we must not permute the first zone and exhaust all the permutations of the second zone. Once we have exhausted them, only then can we proceed with the next permutation of the first zone, but again pause as we exhaust all the permutations of the second zone. This logic is expanded to the general case in the algorithm below.

Finding all permutations of the tensor terms for all ambiguous zones:

Now we permute the actual tensor terms in the locations to achieve all possible permutations to test out.

2.3.5. Simplification of Reducible Terms Algorithm

Now, we put all the algorithms together to simplify the raw, generated reducible tensor terms. The Product Resolver class contains within itself a vector of the raw, unsimplified terms, as well as the simplified terms.

- Reorder the indices of all terms, alphabetically.

- Sort the tensors of all terms, as defined above.

- Iterate over all unsimplified terms:

- (a)

- Iterate over all simplified terms:

- i.

- If the current unsimplified (Attempt Term) and simplified (Source Term) terms have the same structure, attempt to rename them.

- ii.

- If the rename is successful, reorder the indices of the Re-named Term.

- iii.

- Check if the Renamed Term is identical to the Source Term. (Theoretically, this must always be true, as else the rename operation would not have been successful). If so, add the coefficient of the Renamed Term into the Source Term. Break iteration over the simplified terms.

- (b)

- If all simplified terms were iterated over with no successful matches, add the current unsimplified term to the vector of simplified terms. (It could not be simplified with any existing simplified term).

- Erase all simplified tensor terms with a coefficient of 0

By the end of this stage, we have a vector of all simplified, reducible tensor terms.

2.4. Reduction of Reducible Tensor Terms to Irreducible Tensor Terms Phase

In this phase, we will first substitute the simplified, reducible tensors with their corresponding (pre-determined) expressions written in terms of irreducible tensors, Kronecker Deltas, and Levi-Civita tensors. We will then expand out these expressions, expand the Levi-Civita tensors, and then simplify the expression using the properties of Kronecker Deltas, Symmetric-Asymmetric irreducible tensors, and the ability to rename the indices of irreducible tensors and add them.

This phase will make use of the Math Expression class, which resembles a typical algebraic expression, composed of algebraic terms from the Math Expression Term class. The Math Expression Term will serve as a more complex form of the Tensor Term class used in previous phases, as it now will contain various mathematical objects. There are also self-explanatory classes for Deltas, Levi-Civitas, Irreducible Tensors, and Coefficients. The function is as follows:

2.4.1. Substitutions of Reducible Tensors for Expressions with Irreducible Tensors Algorithm

- Given the Source Reducible Tensor, find the number of indices it contains.

- Based on the number of indices, choose the correct substitution sub-category

- In the chosen substitution sub-category, given the Source Reducible Tensor, find the number of barred indices it contains

- Based on the number of barred indices of this sub-category (of number of indices), return the corresponding substituted Math Expression

The terms are then expanded by multiplication.

2.4.2. Multiplication of Levi-Civita Tensors Algorithm

- Iterate for every Math Expression Term in a Math Expression:

- (a)

- If there is more than 1 Levi-Civita:

- i.

- If there are 3 or more Levi-Civitas, group the Levis based on number of common indices

- ii.

- Create a temporary Math Expression for the full Delta Expression

- iii.

- Iterate while there exists atleast one pair of Levis:

- A.

- Expand the pair into this temporary.

- B.

- Delete the pair

- iv.

- Multiply the original term with the full Delta Expression, and ap-pend this to the final result Math Expression.

- v.

- Set the original term to 0.

- vi.

- Delete all terms with 0 coefficient

2.4.3. Simplification of Expression by Kronecker Deltas Algorithm

- Iterate for every term:

- (a)

- Sum over the indices of the Deltas.

- (b)

- Check for possibility of the deltas cancelling out the term. If so, move on to the next term.

- (c)

- Rename the indices of the irreducible tensors by using the Deltas.

- (d)

- Solve identical Deltas and modify the coefficient accordingly.

- Erase all terms with coefficient 0.

2.4.4. Simplification of Expression by Renaming Indices of Irreducible Tensors (Accounting for Commutativity)

- While before the concept of “zones” related to barred versus unbarred indices, now “zones” relates to upper versus lower indices.

- While before the concept of “structure” (and hence “ambiguity”) related to whether 2 reducible tensors have the same label, number of indices, and number of barred indices, now “structure” relates to whether 2 irreducible tensors have the same bar state, field, symmetric property, and number of upper and lower indices.

- While before the sorting of the reducible tensor terms was by (in ascending order) label, then by number of indices, and then by number of barred indices, now the sorting of the irreducible tensor terms is (in ascending order) by field, then by symmetric property, then by bar state, then by number of upper indices, and then by number of lower indices.

- A Single Levi-Civita tensor may survive after simplification and also must be considered in the renaming process. It is considered as its own unique “zone”.

2.4.5. Overall Reduction Phase

- Iterate for every Math Expression Term:

- (a)

- Substitute the reducible tensor terms for the appropriate Math Expressions containing irreducible tensors, Levi-Civitas, and Deltas.

- (b)

- Multiply and expand all the substituted expressions.

- (c)

- Multiply the Levi-Civitas of each term and expand the expression.

- (d)

- Simplify the overall expression by the properties of Kronecker Deltas.

- (e)

- Simplify the overall expression by the property of Symmetric and Asymmetric Irreducible tensors that share 2+ indices.

- (f)

- Simplify the overall expression by the renaming the indices of the expression.

- (g)

- Multiply the overall expression with the original coefficient from the reducible tensor term.

- (h)

- Append this result to the overall Math Expression of the final result.

- Simplify this final result by renaming the indices of the expression

- (a)

- (This step is repeated because before it was only considered within each expression that arose from a reducible tensor term, whereas now it is considering all simplified expressions from all the reducible tensor terms.)

- Multiply the overall expression with the coefficient that arose from expanding the initial user input to the reducible tensors (of the form ).

2.5. Normalization of Irreducible Tensors to Normalized Tensors Phase

In this final phase, we substitute the irreducible tensors with the corresponding normalized tensors, including their coefficients. This is similar to the step in the previous phase where we substituted the reducible tensors for their respective expressions. Each substitution is a unique function due to its coefficients, however the general procedure is outlined below.

- For a given irreducible tensor of a Math Expression Term:

- Create a normalized tensor and transfer the indices exactly as they are from the irreducible tensor.

- Multiply the whole Math Expression Term by the required coefficient.

- Erase the Irreducible Tensor from the Math Expression Term.

This process is repeated for every irreducible tensor in every Math Expression Term in the result expression. No further simplification occurs here because all simplification has been completed before this. Hence, we arrive at our final result. The function is as follows:

2.6. Output Phase

Every component in the result, be it a Delta, Normalized tensor, Coefficient, etc., has a representation in LaTeX designed for it, and hence printing a term simply calls all these functions in turn, and printing an expression calls the printing of each term. The function is as follows:

3. Results

The computer program outputs results in LaTeX format that can be easily included in a publication, as it has been done in Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3. The original coupling inputs are mentioned along with their respective processed results in their final format. Some of these couplings have not previously been demonstrated in the literature, proving the generalized capabilities of the software.

The normalizations of fields are displayed in Appendix B.5. Here the H—fields represent irreducible tensors with canonically normalized kinetic energy terms.

3.1. Quadratic Couplings

126 × 126

3.2. Cubic Couplings

3.2.1. 210 × 210 × 210

3.2.2. 210 × 126 × 210

3.2.3. 210 × 120 × 120

3.3. Quartic Couplings

3.3.1. 210 × 210 × 210 × 45

3.3.2. 210 × 210 × 210 × 210

4. Discussion

This paper proposes a novel C++ software that can compute Higgs couplings automatically in terms of invariants, based on the algorithm developed in Appendix B.4. These interactions arise in both supersymmetric and non-supersymmetric models. A top-down approach to calculate two-point, three-point and higher Higgs-Higgs Interactions is necessary. Such couplings are needed in the breaking of GUT and electroweak symmetries and in the study of higher dimensional operators such as for the exploration of physics beyond the SM. This is important as these operators contribute to the understanding of neutrino masses, baryogenesis, proton decay and oscillations. The stand-alone software exposes a text-based interface to conveniently facilitate the calculation procedure from start to finish. The user enters their required coupling via text, and the program then processes the various intermediate calculations, until it presents the final normalized result in LaTeX format. The number of indices can go up to 5, but the number of tensors appearing in an invariant is not limited. The reliability of the algorithm has also been confirmed, as manual calculations were performed and compared with the computer result, and these were successfully matched.

The code has also been made publicly available so that future development can be done to expand the capabilities of the software. Firstly, one such expansion could be the ability of the software to account for any invariant couplings. Currently this is not supported, however the existing algorithms and data structures could be used as a template for such changes. Secondly, it is also possible to expand this software to account for Higgs–Spinor coupling [31] analysis in the future. This would require the introduction of certain other algorithms and data structures, however the existing codebase will provide a solid foundation for the key algorithms required for the overall process.

We believe that our C++ program will be very useful for particle physicists in general. Researchers will have access to our computer code which will calculate tensor interactions exactly and efficiently within their own models using the top-down approach. The code is available to download https://github.com/AHB99/tensor-coupling-program/releases (accessed on 13 September 2021).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M.S.; Formal analysis, R.M.S.; Funding acquisition, R.M.S.; Investigation, A.B.; Software, A.B.; Supervision, R.M.S.; Writing—original draft, R.M.S. and A.B.; Writing—review and editing, R.M.S. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research of A.B. and R.M.S. was supported by the American University of Sharjah’s Faculty Research Grant Award AS1805. The work in this paper was supported, in part, by the Open Access Program from the American University of Sharjah under award OAPCAS-1110-C00005. This paper represents the opinions of the authors and does not mean to represent the position or opinions of the American University of Sharjah.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

It is a pleasure to acknowledge fruitful and illuminating communications with Pran Nath on many aspects of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. SO(N) Group

In this appendix we discuss vector and various tensor representations of SO(N) group and aspects of SO(N) gauge theory [11].

Appendix A.1. Vector Representation

Consider a real —dimensional coordinate space in which a vector transforms as

In order for the transformation (A1) to leave the length of invariant, that is, , Equation (A1) gives . Therefore, the matrix must satisfy . The set of such length-preserving transformation matrices represent rotations in —dimensions and forms a group called orthogonal group . Taking the determinant of both sides of the last equation gives . That is .

The special orthogonal group is a group of of real matrices obeying,

Now consider the group element of which differ infinitesimally from the identity:

The real numbers are the parameters of the group and specify rotation. Since the matrix is antisymmetric, it has only independent parameters. Making use of Equation (A4) in the infinitesimal transformation (A3), we get . Thus the generators of the group in the vector representation are given by linearly independent matrices (The factor of is chosen for convenience and the reason for inserting i in Equation (A5) is because it is more convenient in quantum mechanics to use the anti-Hermitian generators () rather than antisymmetric (). Then group in Equation (A9) is unitary (). Of course this does not change the fact that is a real Lie algebra):

Note that the matrices are antisymmetric: . Hence, necessarily traceless: . Equation (A5) also shows that the only non-vanishing elements of the matrix are and at the intersection of the row, column () and row, column, respectively. The commutation relation satisfied by the generators can be easily calculated using Equation (A5):

We now obtain finite transformation for the group element from the infinitesimal transformation: using . Therefore,

Appendix A.2. Tensor Representation

In general, we define an rank tensor , having components, to transform as a product of p ordinary vectors, :

Appendix A.2.1. Isotropic Tensors

- 2nd—rank identity tensor (kronecker symbol): (Recall form Appendix A.1 that transformations preserve the scalar product: . This invariant can be written using upper (or equally with lower) indices as , where is a metric tensor and is defined through for a set of basis vectors in an — dimensional space. This implies that the metric tensor corresponds to the orthogonal group. Further, the metric tensor can be used to raise or lower indices of vectors/tensors: , . Therefore, . In other words the covariant and contravariant vectors/tensors coincide for orthonormal basis. Hence, we do not distinguish between superscripts and subscripts).The Kronecker symbol is defined throughIt is invariant under transformation: .

- —rank alternating tensor (levi-civita symbol):The completely antisymmetric Levi-Civita symbol is defined throughAs a consequence of antisymmetry of the Levi-Civita symbol, we haveUsing Equation (A12b), we define the determinant of a matrix asFinally, multiplying both sides of this last equation by and using Equation (A12b), we getUsing Equation (A13), the alternating symbol can be also shown to be an invariant of the group: .

- Other —invariantsOne may now construct [36] various rth—rank invariant tensors from the linear combination of the sum of the products of Kronecker symbols and the alternating tensor. For example, the most general invariant tensors for the case when r is even, take the formwhere the summation is over the set of all permutations of r indices and represent a permutation of . For the special case , we get 4! permutations of out of which only three unique quadratic product of Kronecker deltas can be formed. Hence, and . Here ’s are linear combinations of ’s. In a similar fashion, one can form general invariant tensors when r is odd.

Appendix A.2.2. Irreducibility

Contraction of a tensor with Kronecker symbol (trace operation) and Levi-Civita symbol play an important role in constructing irreducible tensors. A tensor is reducible, if through a contraction operation, a new non-vanishing tensor (generally of smaller rank) can be formed.

If a tensor is reducible because it has nonzero trace, say over indices and , then we may contract it with a Kronecker symbol over those two indices,

leading to a tensor of rank . Here the first two indices have been contracted and summed over but the trace operation can be applied to any pair. A tensor is traceless if the contraction with a Kronecker symbol of any pair of indices vanishes. Moreover, a tensor with all —contracted indices () is an —invariant scalar (singlet).

On the other hand, if a tensor is reducible because it is not symmetric with respect to some of its indices, say , and or a tensor is reducible because it is not symmetric with respect to any of its indices, then we may contract these tensors with a Levi-Civita symbol over those indices,

leading to a tensor of rank with mixed symmetry (antisymmetric in and symmetric in ) and a completely antisymmetric tensor of rank , respectively. Additionally, a tensor with all —contracted indices () is an —invariant scalar.

Therefore,

- an irreducible tensor is completely traceless, that isand

- in view of contraction with Levi-Civita tensor, the tensors and are irreducible, if they are symmetric with respect to the indices on which the sum has been performed, so that

Since completely antisymmetric tensors automatically satisfy Equation (A14), they are the first class of irreducible tensors. The second being completely symmetric and traceless tensors and finally traceless tensors with mixed symmetry.

Appendix A.2.3. Completely Antisymmetric Tensors

A 2nd—rank antisymmetric tensor is defined through

Using Equation (A1) in Equation (A16) gives the transformation law for the second rank antisymmetric tensor:

where we have made usage of Equation (A3) in obtaining Equation (A17c). Note that this is also the adjoint representation of the group. This is because number of group generators matches the dimensionality of the second rank antisymmetric tensor representation.

To find the the generators in the adjoint representation, we use Equation (A3) in Equation (A17a) to obtain , where,

are the generators in the adjoint representation.

In a similar fashion one can define completely antisymmetric tensors of higher rank. In general, an —rank antisymmetric tensor of dimensionality can be formed from the antisymmetric product of ’s as

and with the transformation law in various useful forms given by

Finally, the generators in the —rank antisymmetric representation is given by

For even (), a tensor of rank m, can be expressed in terms of another tensor of rank m, , called the dual, through . Both and are not irreducible tensors under . Now, if we define , then are irreducible tensors. Complete formulation of this subtlety is as follows: The tensor of dimension splits into two irreducible tensors and each of dimension according to the invariant decomposition of a tensor of rank m,

From Equation (A20c), we see that for , the tensors and are real and satisfy self and anti-self duality conditions, respectively. While for , the tensors are complex conjugates of each other. To show the validity of the results (A20b)–(A20c), one can start with , where needs to be determined. Next compute the dual of the dual tensor: , where we have made use of Equations (A12a) and (A12b). Now write, , then . Finally, requiring gives .

Appendix A.2.4. Completely Symmetric and Traceless Tensors

We begin by illustrating second rank symmetric and traceless tensor,

Here is the singlet of group and the dimensionality of is .

As before one can easily write down the transformation law for the second rank symmetric and traceless tensor:

Using Equation (A22a), one can find the generators in the 2nd—rank symmetric representation as

In general, an rth—rank symmetric and traceless tensor of dimensionality can be formed from the symmetric product of ’s as follows

where, for conciseness, we have completely dropped the outer product symbol and the numerical coefficients ’s ensure that the tensor is completely traceless. We now illustrate Equation (A24) by means of and rank symmetric and traceless tensors of with dimensionality and , respectively. Explicit expressions are given by

The transformation law for an rth—rank symmetric tensor in various useful forms take the form

while the generators in this representation are given by

Appendix A.3. Elements of SO(N) Gauge Theory

Appendix A.3.1. Global Symmetries

The real group parameters are independent of space-time coordinate, .

- Scalar boson in the vector representationIntroduce a set of scalar bosonic fields by means of an dimensional column vector, :Of course, the transformation law is the same as before (see Equations (A1) and (A9)):and in terms of its components, Equation (A3) in Equation (A28), givesKinetic energy term for the real scalar bosonic fields appearing in the Lagrangian is given byIt is invariant under global rotations, since . Here is the Dirac index () and we are using the metric .One can also add to the Lagrangian the self-interaction terms. The most general fourth-order invariant couplings take the form

- Scalar boson in the 2nd—rank (adjoint) antisymmetric tensor representationRecall that is also the adjoint representation of the group. Thus, it implies that we have vector gauge bosons denoted by having the global transformation law (A17c):In analogy with Equation (A30), we define the Lagrangian for scalar bosonic fieldsand it is easily seen to be invariant under the global transformation (A17b).The most general invariant quartic self-couplings in the Lagrangian take the formSelf-interaction terms for the vector gauge bosons and its interactions with scalar bosons will be dealt in the next subsection.

- Scalar boson in the 2nd—rank symmetric and traceless tensor representationIn this case, the globally invariant kinetic energy and self-interaction terms in the Lagrangian are given by given by

- Scalar boson in the generalrth—rank tensor representationThe invariant Lagrangian under global transformations is given by

Appendix A.3.2. Local Symmetries

The group parameters are functions of space-time coordinate, .

- Scalar boson in the vector representationThis time the scalar fields introduced through Equation (A27) must transform asThe kinetic energy for ’s given by Equation (A30), is no longer invariant under the local rotations (A38a), because . As in QED, we modify the Lagrangian by replacing the differential operator by the gauge covariant derivative , whereand require to transform like :Note that is to be understood as a matrix carrying a Dirac index, , and operating on the component scalar bosonic field, . Here g is a coupling constant between scalar bosons and vector gauge bosons. Further, using the local gauge transformation (A38a) in Equation (A39) givesThere are group generators and we introduce one vector gauge boson, for each and definein terms of Lie-algebra valued gauge field, . In Equation (A41a), represents identity matrix. Next, we determine the transformation law for the vector gauge boson. Substituting Equations (A38a) and (A41a) in Equation (A39) and using the fact which implies , we getOne could equivalently start from Equation (A40) and derive Equation (A42). We now work out the infinitesimal form of Equation (A42). Using Equations (A3) and (A5) in Equation (A42), we obtain after some algebra, the local transformation law for the vector bosonsIn analogy with QED, we define the field strength tensor, asSubstituting Equations (A41) into Equations (A44) and together with Equation (A5), we getTo find the transformation law for we left and right multiply Equation (A44a) by and , respectively, to obtainwhere we have use of Equation (A40). Note that Equation (A46) is in the form of Equation (A42), hence the corresponding infinitesimal result (A43a) applies without the derivative term:After the introduction of local transformation the Lagrangian (A30) must be replaced byIn order to define the system including the new gauge field, , it is necessary to include a kinetic energy term for :

- Scalar boson in the 2nd—rank antisymmetric tensor representationRecall from Equation (A17b) that the second rank antisymmetric tensor, transforms as . Then just as in the case of the vector representation we want the to transform like :Then the covariant derivative, in terms of Lie-valued gauge fields, which has the transformation property (A50), is given byInserting the generators, we find the expression for the covariant derivative to beThe total Lagrangian is

- Scalar boson in the 2nd—rank symmetric tensor representationRecall from Equation (A22b) that the 2nd—rank symmetric tensor, , transforms as . Hence, the results for this case will be identical to that for the 2nd—rank antisymmetric tensor case. Thereforeand of course

- Scalar boson in the generalrth—rank tensor representationRecall from Equations (A19b) and (A26b) the transformation law for an arbitrary antisymmetric and symmetric tensor of rank r: . Hence, we require that the corresponding covariant derivative, , transforms asThe expression for the covariant derivative is then given byFor example, in the case of 3rd—rank tensor, the above result takes the form

Appendix B. SO(2N) Group in a U(N) Basis

In this appendix, we explain group algebra in basis, branching rules for into irreducible representations and its specialization to case. Further, we show explicitly the technique to decompose tensor invariants in terms of tensor invariants and illustrate this method with some concrete invariants. Finally, in this appendix, we express tensors in terms of irreducible tensors with canonically normalized kinetic energy terms and identify singlets, doublets and triplets in fields.

Appendix B.1. Complete Embedding of U(N) into SO(2N)

Let and given by

be —dimensional complex column vectors of the group where , , and are real vectors. Then the group transformations [11],

leaves the following scalar products invariant:

Now, define two —dimensional real column vectors as follows:

The invariants Equations (A62a)–(A62c) can now be expressed in terms of and :

Next, consider the group acting on the real dimensional vectors and . Then, the group transformations

leaves the following scalar products invariant:

Since the invariants in (A66) are also invariants (see Equations (A64a)–(A64c)), is a “natural” subgroup of .

Note that since , the antisymmetric generators in the basis of Equation (A63), can be written as

where and are real antisymmetric (, ) matrices while is an arbitrary real matrix.

Additionally, if we impose that , then is also a generator of : . Then the corresponding transformation must also leave the fourth quantity in Equation (A64d) invariant: , which under infinitesimal transformations takes the form

Inserting Equation (A67) into Equation (A68) gives

where is a real antisymmetric matrix and is a real symmetric matrix.

The number of independent elements in and are and , respectively, giving a total of independent elements in . The traceless matrices (since is antisymmetric) and the traceless part of matrices : will form the adjoint dimensional representation of the group and the trace of : will be an singlet. This term generates the group of complex phase transformations. Thus, we have the decomposition .

However, the adjoint and singlet representations of is not the full story. There are other generators of that are not in . These remaining generators of form two antisymmetric tensor representations of : each of dimension :

This can be seen from the following argument. From above we have learned that dimensional real vector, , decomposes into dimensional vectors of corresponding to , that is, . Further, the (antisymmetric) generators of can be associated with 2nd rank antisymmetric tensors. Thus, under decomposition: . Thus, . Altogether,

Summarizing:

- dimensional adjoint of is formed from

- Singlet of is formed from

- Antisymmetric representations of is formed from and each of dimensionality

- , , are real antisymmetric matrices and is a real symmetric matrix.

Appendix B.2. Generators of SU(N) in Terms of SO(2N)

For compactness and clarity we drop the subscript from and write them simply as . Looking at the block structure of in Equation (A71), we can make the following assignments [11,24] ()

The generators of group are , defined by

and the (traceless) generators, , are given by

They satisfy algebra,

The generator, , is given by

Lastly, the broken generators of group, and are

Appendix B.3. Branching Rules for SO(2N) into SU(N) ⊗ U(!) Irreducible Representations

The irreducible tensor representations of can be decomposed under by forming tensor products and using Young tableau [11].

- Vector ofThis case was already considered in the Appendix B.1:

- 2nd—rank tensors ofThe antisymmetric tensor representation was also considered in the Appendix B.1:In the case of 2nd—rank symmetric traceless tensor of dimensionality , we get , which on simplifying gives

- 3rd—rank tensors ofHere we form an anti-symmetrized and a symmetrized product of three vectors and subtract off the trace in the case of a symmetric tensor representation. The result for the decomposition of antisymmetric tensor representation with dimensionality is given byThe result for the symmetric traceless tensor representation of dimensionality is

- 4th—rank tensors ofUsing the technique as before, we have the following decomposition of the component 4th—rank antisymmetric tensor representationFor the case of symmetric traceless tensor representation of dimensionality , the decomposition is

- 5th—rank tensors ofThe 5th—rank antisymmetric tensor representation has dimensionality is and can be decomposed as followsFor the case of symmetric traceless tensor representation of dimensionality , the decomposition is

- Specializing to gauge groupRecall from Equations (A20b)–(A20c) that the real -dimensional —rank tensor of , decomposes into two complex —rank tensors, and each of dimensionality : =, where

Appendix B.4. Technique for the Evaluation of SO(2N) Invariant Tensor Couplings. The Basic Theorem

Here we discuss a technique for the analysis of invariant couplings which allows a full exhibition of the invariant content of the tensor representations [8,9,10,11]. The technique utilizes a basis consisting of a specific set of reducible tensors in terms of which the invariant couplings have a simple expansion.

We begin with the identification that the natural basis for the expansion of the invariants is in terms of a specific set of reducible tensors, and which we define as

Inversely,

where are indices and are indices. This can be extended immediately to define the quantity with an arbitrary number of unbarred and barred indices where each c index can be expanded out so that

Thus, for example, the quantity is a sum of terms gotten by expanding all the c indices. is completely antisymmetric in the interchange of its c—indices whether unbarred or barred:

Further,

Use of quantities like are also useful in evaluating kinetic energy like terms such as: , , etc., where and are Dirac indices.

As a first example, consider the bilinear invariant : . We evaluate this invariant in terms of the specific set of reducible tensors. To that end, write , where and . Then . Writing, and , we get and . Adding the last two equations give and hence,

One can now exploit the last result to compute other bilinear invariants such as : . Therefore, . Repeating the process, we get and similarly, . Thus, . Finally, using the antisymmetry of the c—indices, we get

Higher order invariants in terms of specific set of reducible tensors can also be easily computed. As a third example, consider the trilinear invariant : . Expanding, . Rearranging,

For our last example, we compute the quartic invariant, : . The result is

We now give some general results here,

Finally, we make the observation that the object transforms like a reducible representation of . Thus if we are able to compute the invariant couplings in terms of these reducible tensors of then there remains only the further step of decomposing the reducible tensors into their irreducible parts. See subsection Appendix B.5.

Appendix B.5. Explicit Decomposition of Irreducible SO(10) Tensors in Terms of SU(5) Irreducible Tensors with Canonically Normalized Kinetic Energy Terms

- tensors in the –plet ofThe –plet of , , can be decomposed in components [8] as followsThe tensors are already in their irreducible form and one can identify with the –plet of Higgs and with the –plet of Higgs. Now the kinetic energy for the —dimensional Higgs field [8] isTherefore, we normalize the fields according to

- tensors in the –plet ofThe –plet of Higgs, , can be decomposed in multiplets as followswhere , , and are the –plet, –plet, –plet and –plet representations of , respectively. To normalize these Higgs fields [9], we carry out a field redefinition:In terms of the normalized fields, the kinetic energy of the –plet of Higgs,

- tensors in the –plet ofThe –plet of , , can be decomposed in components [8] as followswhere , , , , , are the –plet, –plet, –plet, –plet, –plet and –plet representations of . To normalize them we make the following redefinition of fieldsIn terms of the redefined fields the kinetic energy term for the multiplet takes on the form

- tensors in the –plet ofThe –plet of , , has the following decomposition in multiplets [9]where , , , , , , ; and are the –plet, –plet, –plet, –plet, –plet, –plet, –plet, –plet and –plet representations of , respectively. To normalize these fields, we carry out a field redefinitionNow the kinetic energy for the —dimensional Higgs field in terms of the redefined fields takes the form

- tensors in the –plet ofThe —dimensional tensor of , , has the following decomposition in multiplets [8]The fields that appear above are not yet properly normalized. To normalize the fields we carry out a field redefinition, so that,The kinetic energy for the –plet field in terms of the normalized fields is then given bywhere , , , , , , , , , , are the representations of , respectively.

Appendix B.6. Extraction and Normalization of SU(3)C Triplets, SU(2)L Doublets and SU(3)C × SU(2)L × U(1)Y Singlets in SU(5) Fields

SM doublets, triplets and singlets contained in the fields are needed in the spontaneous breaking of —GUT and electroweak symmetry. Let’s first identify them [14]:

and

where for example, the notation means the triplet field with canonically normalized kinetic energy term and residing in the ’s –plet of ’s –plet. Here are color indices, while are weak indices.

- SM doublets and triplets in –plet and –plet ofand fields of have the following decomposition [27]where # appearing in the subscript refers to , , , , fields of and we have definedHere, ’s and ’s represent unnormalized SM doublet and triplet fields. The kinetic energy of the — and — plets are given byso that the SM fields are normalized according to

- SM doublets and triplets in –plet and –plet of—dimensional field of have the following decomposition [27]where # refers to and fields of . The traceless condition on the tensor leads to the definitionsWe now express all the reducible tensors of the -plet in terms of the irreducible ones as follows:The kinetic energy of the -plet is given byso that the fields are normalized according toOne can now easily extend Equations (A111) and (A112) to ’s . field contained in — and –plets:In Equation (A113), # refers to — and –plets.

- SM triplets in –plet and –plet of—dimensional field of have the following decomposition [27]where we have definedThe first relationship above follows from the traceless condition on the irreducible tensor :We now express the reducible tensors of the –plet in terms of the SM irreducible ones as follows:The kinetic energy of the -plet is given byso that the SM fields are normalized according toOne can now extend the above results to of contained in plet.

- SM singlet in –plet of—dimensional field of have the following decomposition [27]where # refers to and fields of . The tracelessness condition on the tensor gives the following definitionThe reducible tensors of the -plet can be expressed in terms of the irreducible ones as follows:The kinetic energy of the -plet is given byso that the SM fields are normalized according to

- SM singlet in –plet of—dimensional field of have the following decomposition [27]where we have definedAgain the first relationship above follows from the double tracelessness condition on the tensor :The reducible tensors of the –plet can be expressed in terms of the irreducible SM states as follows:The kinetic energy of the –plet is given byso that the SM fields are normalized according to

References

- Weinberg, S. A Model of Leptons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1967, 19, 1264–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glashow, S.L. Partial Symmetries of Weak Interactions. Nucl. Phys. 1961, 22, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A. Weak and Electromagnetic Interactions. Conf. Proc. C 1968, 680519, 367–377._0034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, D.J.; Wilczek, F. Ultraviolet Behavior of Nonabelian Gauge Theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1973, 30, 1343–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, H.D. Reliable Perturbative Results for Strong Interactions? Phys. Rev. Lett. 1973, 30, 1346–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgi, H. The State of the Art—Gauge Theories. AIP Conf. Proc. 1975, 23, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzsch, H.; Minkowski, P. Unified Interactions of Leptons and Hadrons. Ann. Phys. 1975, 93, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Syed, R.M. Analysis of couplings with large tensor representations in SO(2N) and proton decay. Phys. Lett. B 2001, 506, 68–76, Erratum in 2001, 508, 216–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Syed, R.M. Complete cubic and quartic couplings of 16 and bar-16 in SO(10) unification. Nucl. Phys. B 2001, 618, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, R.M. Analysis of SO(2N) couplings of spinor and tensor representations in SU(N) times U(1) invariant forms. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Particles, Strings and Cosmology (PASCOS 2004), Part II: Themes in Unification—The Pran Nath Festschrift, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA, 16–22 August 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, R.M. Couplings in SO(10) Grand Unification. Ph.D. Thesis, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Aboubrahim, A.; Nath, P.; Syed, R.M. Corrections to Yukawa couplings from higher dimensional operators in a natural SUSY SO(10) and HL-LHC implications. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 01, 047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboubrahim, A.; Nath, P.; Syed, R.M. Yukawa coupling unification in an SO(10) model consistent with Fermilab (g − 2)μ result. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 06, 002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Syed, R.M. An Analysis of B − L = −2 Operators from Matter-Higgs Interactions in a Class of Supersymmetric SO(10) Models. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 93, 055005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, K.S.; Gogoladze, I.; Nath, P.; Syed, R.M. Variety of SO(10) GUTs with Natural Doublet-Triplet Splitting via the Missing Partner Mechanism. Phys. Rev. D 2012, 85, 075002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, K.S.; Gogoladze, I.; Nath, P.; Syed, R.M. A Unified framework for symmetry breaking in SO(10). Phys. Rev. D 2005, 72, 095011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, K.S.; Gogoladze, I.; Nath, P.; Syed, R.M. Fermion Mass Generation in SO(10) with a Unified Higgs Sector. Phys. Rev. D 2006, 74, 075004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Syed, R.M. Couplings of vector-spinor representation for SO(10) model building. J. High Energy Phys. 2006, 02, 022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Syed, R.M. Suppression of Higgsino mediated proton decay by cancellations in GUTs and strings. Phys. Rev. D 2008, 77, 015015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Syed, R.M. Yukawa Couplings and Quark and Lepton Masses in an SO(10) Model with a Unified Higgs Sector. Phys. Rev. D 2010, 81, 037701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Chamseddine, A.H.; Arnowitt, R.L. Nucleon Decay in Supergravity Unified Theories. Phys. Rev. D 1985, 32, 2348–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Perez, P.F. Proton stability in grand unified theories, in strings and in branes. Phys. Rept. 2007, 441, 191–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, R.N.; Sakita, B. SO(2n) Grand Unification in an SU(N) Basis. Phys. Rev. D 1980, 21, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibbelink, S.G.; Nyawelo, T.S.; van Holten, J.W. Construction and analysis of anomaly free supersymmetric SO(2N)/U(N) sigma models. Nucl. Phys. B 2001, 594, 441–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulakh, C.S.; Girdhar, A. SO(10) a la Pati-Salam. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2005, 20, 865–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulakh, C.S.; Girdhar, A. SO(10) MSGUT: Spectra, couplings and threshold effects. Nucl. Phys. B 2005, 711, 275–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slansky, R. Group Theory for Unified Model Building. Phys. Rept. 1981, 79, 1–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.W.; Blazek, T. E(6) unification model building. 1. Clebsch-Gordan coefficients of 27 x 27-bar. J. Math. Phys. 2000, 41, 4808–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.G.; Meljanac, S. Symmetry breaking and mass spectra in supersymmetric SO(10) models. Phys. Rev. D 1990, 41, 1620–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, T.; Ilakovac, A.; Kikuchi, T.; Meljanac, S.; Okada, N. SO(10) group theory for the unified model building. J. Math. Phys. 2005, 46, 033505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, N.; Emmanuel-Costa, D.; Gonçalves, N.; Simoes, C. SOSpin, a C++ library for Yukawa decomposition in SO(2N) models. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2016, 203, 178–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feger, R.; Kephart, T.W.; Saskowski, R.J. LieART 2.0 – A Mathematica application for Lie Algebras and Representation Theory. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2020, 257, 107490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staub, F. SARAH 4: A tool for (not only SUSY) model builders. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2014, 185, 1773–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, C.; Reuter, J. CleGo: A package for automated computation of Clebsch-Gordan coefficients in Tensor Product Representations for Lie Algebras A–G. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2011, 182, 1543–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alloul, A.; Christensen, N.D.; Degrande, C.; Duhr, C.; Fuks, B. FeynRules 2.0—A complete toolbox for tree-level phenomenology. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2014, 185, 2250–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, P.; Duffy, B.; Ogden, R. On the classification of isotropic tensors. Glasg. Math. J. 1987, 29, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).