Abstract

Background. Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is the most common cause of flaccid paralysis, with about 100,000 people developing the disorder every year worldwide. Recently, the incidence of GBS has increased during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) epidemics. We reviewed the literature to give a comprehensive overview of the demographic characteristics, clinical features, diagnostic investigations, and outcome of SARS-CoV-2-related GBS patients. Methods. Embase, MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Central Trials Register were systematically searched on 24 September 2020 for studies reporting on GBS secondary to COVID-19. Results. We identified 63 articles; we included 32 studies in our review. A total of 41 GBS cases with a confirmed or probable COVID-19 infection were reported: 26 of them were single case reports and 6 case series. Published studies on SARS-CoV-2-related GBS typically report a classic sensorimotor type of GBS often with a demyelinating electrophysiological subtype. Miller Fisher syndrome was reported in a quarter of the cases. In 78.1% of the cases, the response to immunomodulating therapy is favourable. The disease course is frequently severe and about one-third of the patients with SARS-CoV-2-associated GBS requires mechanical ventilation and Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission. Rarely the outcome is poor or even fatal (10.8% of the cases). Conclusion. Clinical presentation, course, response to treatment, and outcome are similar in SARS-CoV-2-associated GBS and GBS due to other triggers.

1. Introduction

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is the most common cause of flaccid paralysis, with about 100,000 people developing the disorder every year worldwide [1]. GBS is considered a postinfectious disease as approximately two-thirds of patients report preceding infections with specific pathogens, such as Campylobacter jejuni (32%), cytomegalovirus (13%), and Epstein-Barr virus (10%) [2].

Recently, several cases of GBS were reported during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) epidemics worldwide. Patients with COVID-19 typically have fever and respiratory illness; however, a wide range of other symptoms have been described. While the neurological sequelae of the virus remain poorly understood, there are a growing number of reports of neurological manifestations of COVID-19 [3].

GBS is an acute, immune-mediated polyradiculoneuropathy with a wide range of clinical manifestations. The classic form of GBS is characterized by a rapidly progressive and symmetrical weakness of the limbs, with sensory symptoms and reduced or absent tendon reflexes [4]. The clinical presentation and severity of GBS can vary extensively between patients. Electrophysiological studies help confirm the diagnosis of GBS, and can indicate different subtypes, including acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP), acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN), and acute motor and sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN) [5]. Besides the classic presentation of GBS, clinical variants are reported, such as the Miller Fisher syndrome (MFS) which is characterized by ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, and areflexia without any weakness [5].

Treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) or plasma exchange (PLEX) is the optimal management approach, alongside supportive care [6]. Most patients with GBS show extensive recovery, and about 80% of patients with GBS regain the ability to walk independently at 6 months after the disease onset [6].

Since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” on 30 January 2020, the impact of COVID-19 on patients has been profound. As the full clinical spectrum of COVID-19 is continuing to be described, preliminary findings from case reports and case series have uncovered neurological complications. An important step is to get a better understanding of the acute and post-infectious manifestations of COVID-19 to guide long-term management and health service reorganization. To help add to this small albeit developing body of evidence, this systematic review adds to other studies on GBS secondary to COVID-19.

Objectives. We have performed a systematic review of all published studies on SARS-CoV-2-related GBS, and give a comprehensive overview of the demographic characteristics, clinical features, diagnostic investigations, and outcome of SARS-CoV-2-related GBS patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

We performed a systematic review based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [7]. The protocol was not published, and the review was not registered with the International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO).

2.2. Literature Search

We identified the articles by searching electronic databases (Embase, MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Central Trials Register). Other relevant studies were identified from the reference lists. We used a combination of such terms as “Guillain-Barré Syndrome” and “COVID-19”. The initial search was performed on 24 September 2020. The titles and abstracts were screened by two researchers (PS and LGG) to identify the key words. The selected papers were read in full by the two independent reviewers and a third reviewer (MCP) was consulted in case of disagreement.

We included all the papers with available full text, without any restriction of the year of publication, reporting original data of patients with GBS and a suspected, probable, or confirmed recent SARS-CoV-2 infection, of any age, gender, and in any setting.

Predefined exclusion criteria were: GBS within 3 months after a vaccination or other proven triggering infection (e.g., C. jejuni), and studies with no information on residence, and at least one clinical variable of interest.

2.3. Data Extraction and Management

Data were extracted independently by one of the three reviewers (PS, LGG, MCP) according to a predefined protocol. The data extraction was then checked by one of the other two reviewers, and discrepancies were solved by discussion among all of them. Variables of interest comprised demographics, clinical characteristics (symptoms and signs of coronavirus infection and GBS), ancillary diagnostic investigations (electrophysiology and cerebrospinal fluid [CSF]), treatment, clinical course, and outcome of GBS.

Cases were classified according to the reported diagnostic certainty levels for GBS and SARS-CoV-2 infection. To classify the diagnosis GBS, we employed the “Brighton Collaboration Criteria (2011)” [8]. These were defined on the basis of the available reported data. The diagnostic certainty of SARS-CoV-2 infection was established according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria [9].

Clinical characteristics were reported together with the ratio of the number of patients in whom the variable was present (n) and the total number of reported cases (N): n/N (%). As for the symptoms, we assumed they were absent rather than missing if they were not cited in the manuscript, in order to account for the reporting bias, and therefore described as zero (n) out of the total number of reported cases (N).

Continuous variables (age, time between infectious and neurological symptoms, duration of progression and plateau phase of GBS, duration of hospital admission) were extracted as medians and or means, depending on how they were presented in the original article.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

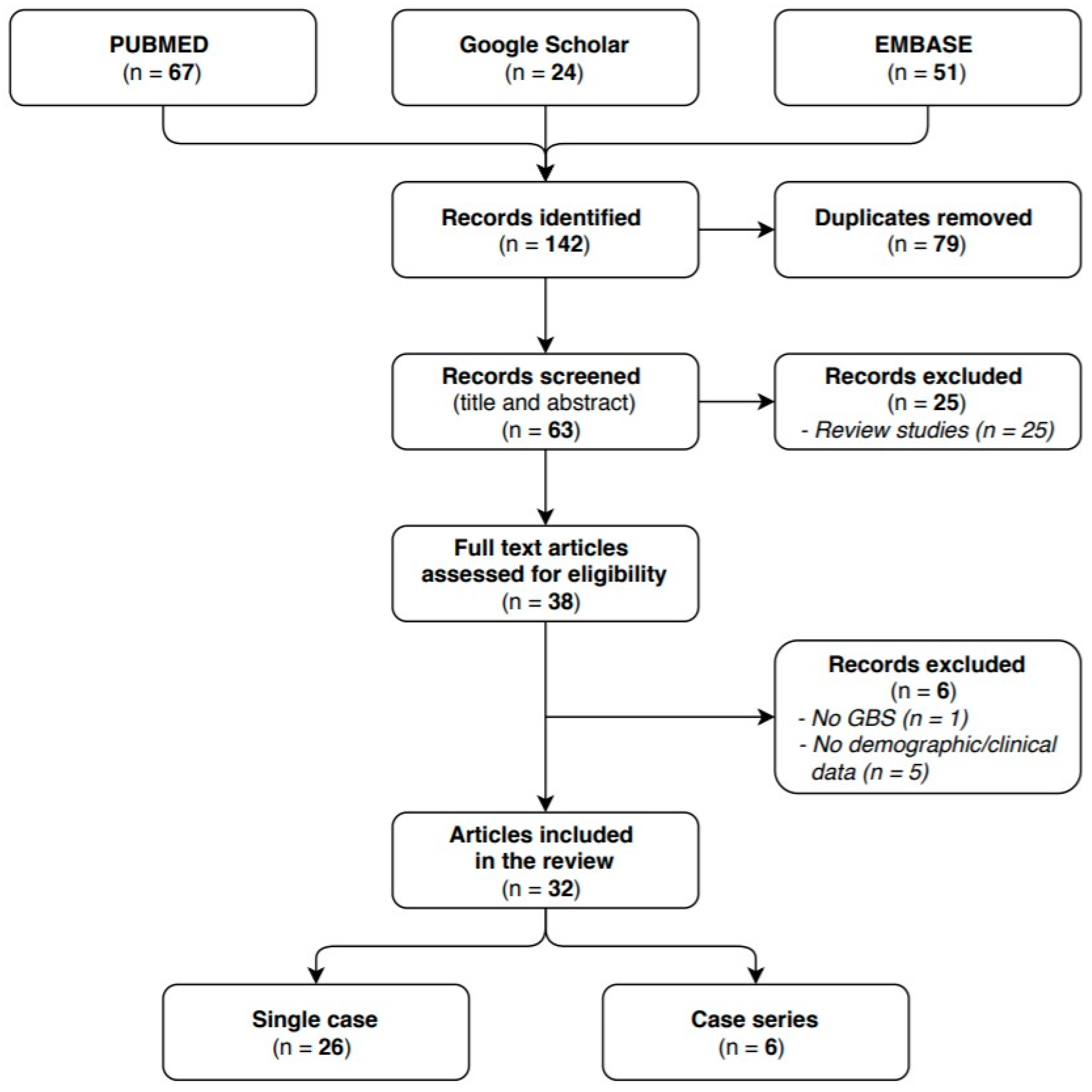

We identified 63 articles in the researched databases, and 32 of them were included in our systematic review. The 32 selected studies reported on a total of 41 GBS cases with a confirmed or probable COVID-19 infection: 26 of them were single case reports and 6 case series. The flow diagram (see Figure 1) shows the results from the literature search and the study selection process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram study selection process.

3.2. Study Characteristics

All the Studies Are Presented Alphabetically with a Brief Clinical Description Per Case (Table 1).

Table 1.

Case reports of Guillain-Barre’ syndrome (GBS) with recent COVID-19 infection.

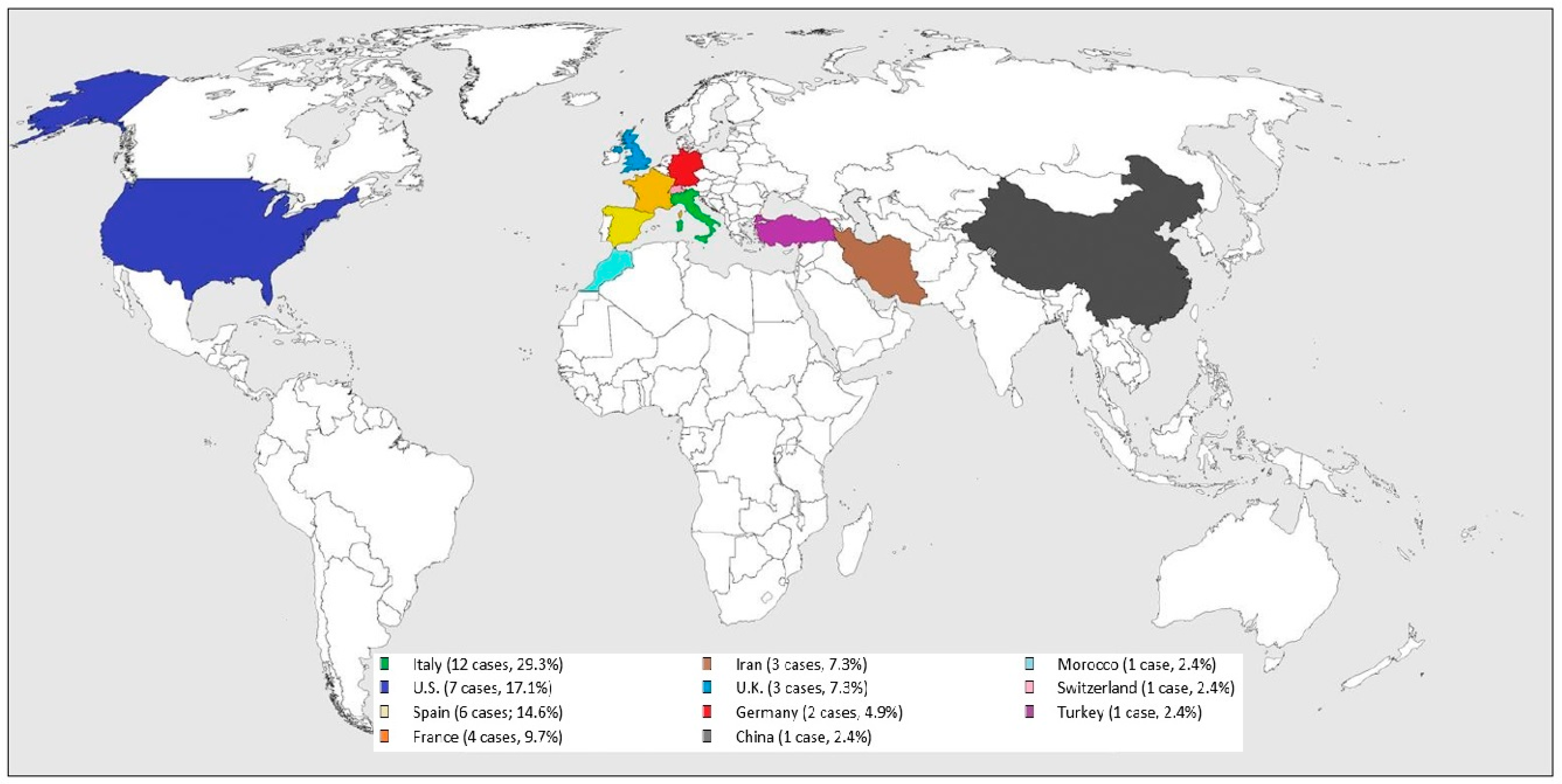

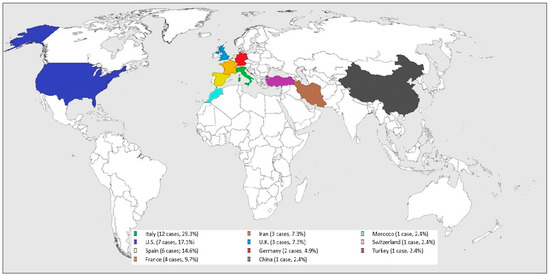

All the cases were from COVID-19 epidemic or endemic regions (see Figure 2): 12 cases were from Italy (29.3%), 7 from U.S. (17.1%), 6 from Spain (14.6%), 4 from France (9.7%), 3 from Iran (7.3%) and U.K. (7.3%), 2 from Germany (4.9%), and one from China (2.4%), Morocco (2.4%), Switzerland (2.4%), and Turkey (2.4%).

Figure 2.

Worldwide SARS-CoV-2 related GBS distribution.

Thirty-three cases were positive for nasopharyngeal swab test for SARS-CoV-2 by qualitative RT-PCR assay, four for oropharyngeal swab test for SARS-CoV-2 by qualitative RT-PCR assay, two for anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgA, and four for anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG. In Manganotti P et al., the patient was reported to be COVID-19 positive with no further information provided. After discussion, we decided to consider it as a probable case of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A chest CT scan was performed in fifteen cases showing multiple bilateral ground glass opacities, typical of COVID-19 pneumonia. Eleven studies reported a chest X-ray: five studies showed bilateral ground glass pneumonia.

The classic form of GBS was diagnosed in 33 cases. Twenty-one of the twenty-seven cases where the Brighton classification was reported, fulfilled level 1. The most frequent clinical phenotype was demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. In 8 cases, the variant MFS was diagnosed.

3.3. Patient Characteristics

3.3.1. Demographics

The median age of the study populations varied between 36 and 74 years, and only 1 pediatric patient was included in Paybast S et al. The majority of patients were male (62.8%) and the male:female ratio of all studies combined was 1.69. Toscano G et al. did not report the patients’ age.

3.3.2. Certainty Levels of GBS Diagnosis and Infection

Separate proportions of each Brighton level (1–4) were obtained in twenty-one studies (27 cases): 21 cases fulfilling level 1; 5 level 2; 0 level 3; and 1 level 4. MFS was reported in seven studies: two studies from Italy (1 patient in Assini A et al., and 1 patient in Manganotti P et al.), from Spain (1 patient in Fernandez-Dominguez J et al., and 2 patients in Gutierrez-Ortiz C et al.), and from U.S. (1 patient in Dinkin M et al., and 1 patient in Lantos JE et al.), and one study from U.K. (1 patient in Ray A).

SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed in 40 (97.6%) and probable in 1 (2.4%) of all cases.

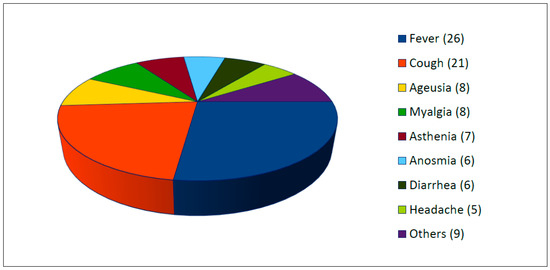

3.3.3. Clinical Characteristics

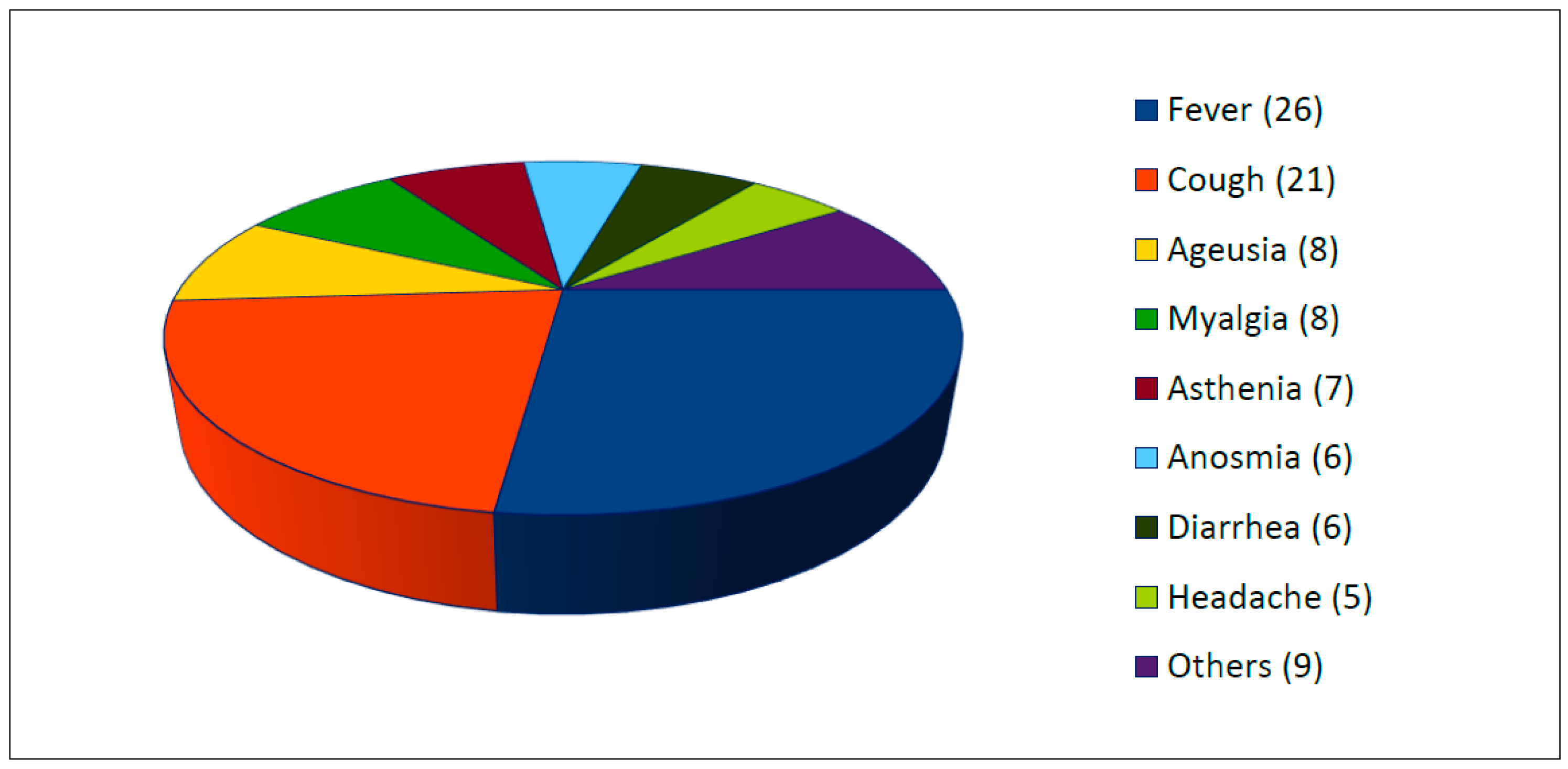

All studies reported the presence of clinical symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection (see Figure 3). Two or more symptoms were present in 87.5% of cases. The most common symptoms were fever (63.4%, 26/41 cases), cough (51.2%, 21/41 cases), ageusia (22%, 9/41), myalgia (19.5%, 8/41), asthenia (17.1%, 7/41), anosmia (17.1%, 7/41), diarrhea (14.6%, 6/41), and headache (12.2%, 5/41). Others reported symptoms were chills, dyspnea, dizziness, and pruriginous rash.

Figure 3.

Clinical symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection (number, n =).

The median time between the start of infectious symptoms and neurological symptoms ranged from 23 to 8 days in the studies reporting on this, except for Dinkin M et al., Oguz-Akarsu E et al., and Paybast S et al.

Among neurological findings, almost all studies reported on sensory symptoms, tendon reflexes, and facial palsy, whereas other symptoms were reported less frequently. The most frequent neurological findings were hypo/areflexia (n = 34), paraesthesia (n = 26), and limb paresis (n = 18). Other frequent symptoms were facial palsy and ataxia in about one third of cases. Other symptoms were reported less frequently, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Neurological symptoms and signs.

3.4. Diagnostic Investigations

PCR, principally from nasal or throat swab, was the most frequently performed test for SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgA was positive in two cases (Coen M et al., and Naddaf E et al.), and anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG in three cases (Coen M et al., Naddaf E et al., and Riva N et al.). In the CSF, SARS-CoV-2 PCR was negative in all tested cases.

Only eleven studies tested all the cases for other infections that have been associated with GBS (C. jejuni, CMV, EBV, hepatitis E virus, mycoplasma pneumoniae) and all the tested cases (11/41; 26.8%) were negative for recent infection. None of the studies tested for all of these pathogens.

CSF was examined in thirty-one studies, and information on protein level and cell count was provided by all of these. Increased protein level and albuminocytological dissociation were present in the vast majority of cases. Only three studies reported normal CSF cell count: 1 case in Oguz-Akarsu E et al., 1 case in Riva N et al., and two cases in Toscano G et al.

Electrophysiological studies were done in 30 (73.2%) of the reported cases. The most frequent electrophysiological subtype was AIDP in 56.7%, followed by AMSAN in 16.7% and AMAN in 13.3% of cases. In three studies (Ottaviani D et al., Paybast S et al., and Rana S et al.) electrophysiological studies showed a mixed pattern of demyelination and axonal damage. The investigations are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Ancillary investigations, treatment, and disease progression of GBS cases associated with SARS-CoV-2.

3.5. Treatment and Disease Progression

As shown in Table 3, all the studies provided information on the treatment, except for Marta-Enguita J et al. Almost all cases were treated with an immunomodulating therapy. In Caamaño DSJ et al., patients received oral prednisone. Only two cases (Dinkin M et al. and Gutierrez-Ortiz C et al.) did not require any treatment.

Thirty patients were treated with IVIg. The preferred therapeutic regimen was intravenous immunoglobulin at 0.4 g/kg/day for 5 days. Plasma exchange was performed four times (Granger A et al., Naddaf E et al., Oguz-Akarsu E et al., and Paybast S et al.). In two cases (Pfefferkorn T et al. and Toscano G et al), IVIg and PLEX were both administered.

Admission to ICU was required in a third of the cases, as well as the mechanical ventilation. Death was infrequent and only two studies (Alberti P et al. and Marta-Enguita J et al.) reported the patient exitus.

4. Discussion

It is now known that SARS-CoV-2 can often affect central and peripheral nervous system, apart from the bronchopulmonary system [42].

The current study reports various cases of GBS or its variants in patients with SARS-CoV2 infection. Our systematic review shows that published studies on SARS-CoV-2-related GBS typically report a classic sensorimotor type of GBS often with a facial palsy and a demyelinating electrophysiological subtype.

The time between onset of infectious and neurological symptoms and negative PCR in most patients suggests a post-infectious mechanism rather than a direct infectious one.

The mechanism involving the peripheral nervous system in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients and the development of GBS is unknown. Since most patients developed GBS on average 10 days after the first non-neurological symptoms of the SARS-CoV-2 infection, a causal relation is quite likely.

However, in none of the included patients, specific SARS-CoV2 RNA was found in the CSF. This suggests that GBS is not triggered by a direct viral attack against the nerve roots but rather by an immune-mediated mechanism, such as antibody precipitation on myelin sheaths or axons [43]. COVID-19 is associated with a cytokine storm and a dysregulated immune response [44]. A mimicry between the epitopes on the surface of the virus and the ones on neuronal membranes is possible, because they are simultaneously attacked by the immune response, just like in the GBS due to C. jejunii [45]. It is also possible that the virus directly invades motor and sensory neurons since the presence of the virus was reported in neural and capillary endothelial cells in frontal lobe tissue obtained at post-mortem examination from a patient infected with SARS-CoV-2 [46].

Published studies on SARS-CoV-2-related GBS typically report a classic sensorimotor type of GBS often with a demyelinating electrophysiological subtype. The distribution of subtypes varies between countries. In Europe and the United States, AIDP affects 60–80% of people with GBS, while AMAN affects only a 6–7%. In Asia and Central and South America, that proportion is nearly 30–65%. This is related to the exposure to various infections and to the genetic characteristics of population [47]. This study found that in Western countries, the demyelinating subtype affected most of the people with GBS, while AMAN/AMSAN affected only a small number. MFS was reported in a quarter of the cases.

A male preponderance was noted as with non-SARS-CoV-2-associated GBS. Similarly, elderly patients are more frequently affected than the younger.

We noticed how GBS can arise in patients who are totally asymptomatic or with moderate symptoms of COVID-19. Furthermore, the severity of GBS is not correlated with that of COVID-19. GBS-related neurological symptoms have often overlapped with COVID19-related symptoms, due to the short time between the SARS-CoV-2 infection and the onset of GBS (8–23 days). It is therefore evident that this overlap contributes to a poor prognosis.

Increased protein level and albuminocytological dissociation were present in most cases. This pattern distinguishes GBS from other conditions, such as lymphoma and poliomyelitis, in which both the protein and the cell count are elevated. Furthermore, protein level in CSF was shown to correlate with disease activity, progression, and response to the treatment [48].

None of the patients with reported CSF analysis had SARS-CoV-2 in the CSF. This is in contradiction with various case reports, which detected SARS-CoV-2 in the CSF [49,50]. A possible explanation is the lack of disruption of the blood-brain barrier that would allow SARS-CoV-2 to cross the CSF space [51].

Another possible explanation is the low sensitivity, around 60%, of the currently available real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) [52].

In almost all cases, the response to immunomodulating therapy was favorable. Intravenous immunoglobulins and plasmapheresis are the two main immunotherapy treatments for GBS [53,54]. A five-day course of daily IVIg (0.4 g/kg/day) was the most common regime adopted. Plasma exchange was performed four times. In two cases, IVIg and PLEX were both administered but a combination of the two is not significantly better than either alone [53]. Only a patient received corticosteroids, even if it is shown that they are not effective in speeding recovery and could potentially delay recovery [55].

The disease course was frequently severe and about one-third of the patients with SARS-CoV-2-associated GBS required mechanical ventilation and ICU admission. Rarely the outcome was poor or even fatal.

Limitations. Our study has several limitations. First, the studies included in this systematic review are variable in study design and setting, selection criteria, diagnostic ascertainment, and reporting of variables, which are potential sources of bias. Second, given the concurrent manifestations of COVID-19 and GBS, it is possible that some COVID-19 symptoms could be attributed to GBS and vice versa, since both diseases affect the respiratory system. Third, such cases without results of nerve conduction were not categorized into GBS subtypes, since it was not possible to confirm whether the symptoms were due to demyelination or axonal damage.

5. Conclusions

The SARS-CoV-2 infection can cause GBS. The underlying mechanism leading to development of this condition is still unclear. The CSF is free of SARS-CoV2 RNA, therefore excluding a viral attack directed against the nerve roots, but various hypotheses are possible. Clinical presentation, course, response to treatment, and outcome are similar in SARS-CoV-2-associated GBS and GBS due to other triggers. It is important to be aware of this association to avoid delay in diagnosis and to promote early treatment initiation given the significant risk of morbidity and mortality.

Author Contributions

P.S. and L.G.G. helped design the study, conduct the study, analyse the data, and writethe manuscript; C.A., F.C., V.E., M.F., A.P., M.B.P. and V.P. helped design thestudy and analyse the data; M.C.P. helped designthe study, conduct the study and analyse the data. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sejvar, J.J.; Baughman, A.L.; Wise, M.; Morgan, O.W. Population incidence of Guillain-Barre’ syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology 2011, 36, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, B.C.; Rothbarth, P.H.; Van der Meché, F.G.A.; Herbrink, P.; Schmitz, P.I.M.; De Klerk, M.A.; Van Doorn, P.A. The spectrum of antecedent infections in Guillain-Barre’ syndrome: A case-control study. Neurology 1998, 51, 1110–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, A.; Anson, M.; Harky, A. Neurological Manifestations of COVID-19: A systematic review and current update. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2020, 142, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willison, H.J.; Jacobs, B.C.; van Doorn, P.A. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet 2016, 388, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimachkie, M.M.; Barohn, R.J. Guillain-Barré syndrome and variants. Neurol. Clin. 2013, 31, 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhard, S.E.; Mandarakas, M.R.; Gondim, F.A.; Bateman, K.; Ferreira, M.L.; Cornblath, D.R.; van Doorn, P.A.; Dourado, M.E.; Hughes, R.A.C.; Islam, B.; et al. Diagnosis and management of Guillain-Barré syndrome in ten steps. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokke, C.; van den Berg, B.; Drenthen, J.; Walgaard, C.; van Doorn, P.A.; Jacobs, B.C. Diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome and validation of Brighton criteria. Brain 2014, 37, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diagnostic Testing for SARS-CoV-2. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/diagnostic-testing-for-sars-cov-2 (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- Alberti, P.; Beretta, S.; Piatti, M.; Karantzoulis, A.; Piatti, M.L.; Santoro, P.; Viganò, M.; Giovannelli, G.; Pirro, F.; Montisano, D.A.; et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome related to COVID-19 infection. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 7, e741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, S.; Budowski, C.; Tin, S.N.W.; Degos, B. Post SARS-CoV-2 Guillain-Barré syndrome. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 131, 1652–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assini, A.; Benedetti, L.; Di Maio, S.; Schirinzi, E.; Del Sette, M. New clinical manifestation of COVID-19 related Guillain-Barrè syndrome highly responsive to intravenous immunoglobulins: Two Italian cases. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 41, 1657–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigaut, K.; Mallaret, M.; Baloglu, S.; Nemoz, B.; Morand, P.; Baicry, F.; Godon, A.; Voulleminot, P.; Kremer, L.; Chanson, J.-B.; et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome related to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 7, e785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juliao Caamaño, D.S.; Alonso Beato, R. Facial diplegia, a possible atypical variant of Guillain-Barré Syndrome as a rare neurological complication of SARS-CoV-2. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 77, 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camdessanche, J.P.; Morel, J.; Pozzetto, B.; Paul, S.; Tholance, Y.; Botelho-Nevers, E. COVID-19 may induce Guillain-Barré syndrome. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 176, 516–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coen, M.; Jeanson, G.; Almeida, L.A.C.; Hübers, A.; Stierlin, F.; Najjar, I.; Ongaro, M.; Moulin, K.; Makrygianni, M.; Leemann, B. Guillain-Barré syndrome as a complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 111–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkin, M.; Gao, V.; Kahan, J.; Bobker, S.; Simonetto, M.; Wechsler, P.; Harpe, J.; Greer, C.; Mints, G.; Salama, G.; et al. COVID-19 presenting with ophthalmoparesis from cranial nerve palsy. Neurology 2020, 95, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Otmani, H.; El Moutawakil, B.; Rafai, M.A.; El Benna, N.; El Kettani, C.; Soussi, M.; El Mdaghri, N.; Barrou, H.; Afif, H. Covid-19 and Guillain-Barré syndrome: More than a coincidence! Rev. Neurol. 2020, 176, 518–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Domínguez, J.; Ameijide-Sanluis, E.; García-Cabo, C.; García-Rodríguez, R.; Mateos, V. Miller-Fisher-like syndrome related to SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID 19). J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 2495–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velayos Galán, A.; Del Saz Saucedo, P.; Peinado Postigo, F.; Botia Paniagua, E. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Neurologia 2020, 35, 268–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granger, A.; Omari, M.; Jakubowska-Sadowska, K.; Boffa, M.; Zakin, E. SARS-CoV-2-Associated Guillain-Barre Syndrome With Good Response to Plasmapheresis. J. Clin. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2020, 22, 58–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Ortiz, C.; Méndez-Guerrero, A.; Rodrigo-Rey, S.; San Pedro-Murillo, E.; Bermejo-Guerrero, L.; Gordo-Mañas, R.; de Aragón-Gómez, F.; Benito-León, J. Miller Fisher syndrome and polyneuritis cranialis in COVID-19. Neurology 2020, 95, e601–e605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantos, J.E.; Strauss, S.B.; Lin, E. COVID-19-Associated Miller Fisher Syndrome: MRI Findings. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2020, 41, 1184–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manganotti, P.; Pesavento, V.; Stella, A.B.; Bonzi, L.; Campagnolo, E.; Bellavita, G.; Fabris, B.; Luzzati, R. Miller Fisher syndrome diagnosis and treatment in a patient with SARS-CoV-2. J. Neurovirol. 2020, 26, 605–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta-Enguita, J.; Rubio-Baines, I.; Gastón-Zubimendi, I. Fatal Guillain-Barre syndrome after infection with SARS-CoV-2. Neurologia 2020, 35, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naddaf, E.; Laughlin, R.S.; Klein, C.J.; Toledano, M.; Theel, E.S.; Binnicker, M.J. Guillain-Barré Syndrome in a Patient with Evidence of Recent SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 1799–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguz-Akarsu, E.; Ozpar, R.; Mirzayev, H.; Acet-Ozturk, N.A.; Hakyemez, B.; Ediger, D.; Karli, N. Guillain-Barré Syndrome in a Patient with Minimal Symptoms of COVID-19 Infection. Muscle Nerve. 2020, 62, E54–E57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, D.; Boso, F.; Tranquillini, E.; Gapeni, I.; Pedrotti, G.; Cozzio, S.; Guarrera, G.M.; Giometto, B. Early Guillain-Barré syndrome in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A case report from an Italian COVID-hospital. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 41, 1351–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padroni, M.; Mastrangelo, V.; Asioli, G.M.; Pavolucci, L.; Abu-Rumeileh, S.; Piscaglia, M.G.; Querzani, P.; Callegarini, C.; Foschi, M. Guillain-Barré syndrome following COVID-19: New infection, old complication? J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 1877–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paybast, S.; Gorji, R.; Mavandadi, S. Guillain-Barré Syndrome as a Neurological Complication of Novel COVID-19 Infection: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Neurologist 2020, 25, 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferkorn, T.; Dabitz, R.; von Wernitz-Keibel, T.; Aufenanger, J.; Nowak-Machen, M.; Janssen, H. Acute polyradiculoneuritis with locked-in syndrome in a patient with Covid-19. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 1883–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Lima, A.A.; Chandra, R.; Valeriano, J.; Desai, T.; Freiberg, W.; Small, G. Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19)-Associated Guillain-Barré Syndrome: Case Report. J. Clin. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2020, 21, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, A. Miller Fisher syndrome and COVID-19: Is there a link? BMJ Case Rep. 2020, 13, e236419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, N.; Russo, T.; Falzone, Y.M.; Strollo, M.; Amadio, S.; Del Carro, U.; Locatelli, M.; Filippi, M.; Fazio, R. Post-infectious Guillain-Barré syndrome related to SARS-CoV-2 infection: A case report. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 2492–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidl, E.; Canseco, D.D.; Hadji-Naumov, A.; Bereznai, B. Guillain-Barré syndrome during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: A case report and review of recent literature. J. Peripher Nerv. Syst. 2020, 25, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaghat, Z.; Karimi, N. Guillain Barre syndrome associated with COVID-19 infection: A case report. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 76, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.W.; Palka, S.V.; Rao, R.R.; Chen, F.S.; Brackney, C.R.; Cambi, F. SARS-CoV-2-associated Guillain-Barré syndrome with dysautonomia. Muscle Nerve. 2020, 62, E48–E49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiet, M.Y.; Al Shaikh, N. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with COVID-19 infection: A case from the UK. BMJ Case Rep. 2020, 13, e236536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toscano, G.; Palmerini, F.; Ravaglia, S.; Ruiz, L.; Invernizzi, P.; Cuzzoni, M.G.; Baldanti, F.; Postorino, P. Guillain-Barré Syndrome Associated with SARS-CoV-2. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2574–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, S.; Wallace, V.C.; Martin-Lopez, D.; Yogarajah, M. Guillain-Barré syndrome following COVID-19: A newly emerging post-infectious complication. BMJ Case Rep. 2020, 13, e236182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Shen, D.; Zhou, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, S. Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: Causality or coincidence? Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 383–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finsterer, J.; Stollberger, C. Update on the neurology of COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2316–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finsterer, J.; Scorza, F.A.; Ghosh, R. COVID-19 polyradiculitis in 24 patients without SARS-CoV-2 in the cerebro-spinal fluid. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, T.; Cai, D.; Hu, Z.; Chen, J.; Liao, H.; Zhi, L.; Wei, H.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, Y.; et al. Cytokine storm intervention in the early stages of COVID-19 pneumonia. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020, 53, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuki, N.; Susuki, K.; Koga, M.; Nishimoto, Y.; Odaka, M.; Hirata, K.; Taguchi, K.; Miyatake, T.; Furukawa, K.; Kobata, T.; et al. Carbohydrate mimicry between human ganglioside GM1 and Campylobacter jejuni lipooligosaccharide causes Guillain-Barre syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 11404–11409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paniz-Mondolfi, A.; Bryce, C.; Grimes, Z.; Gordon, R.E.; Reidy, J.; Lednicky, J.; Sordillo, E.M.; Fowkes, M. Central nervous system involvement by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 699–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, B.; Walgaard, C.; Drenthen, J.; Fokke, C.; Jacobs, B.C.; van Doorn, P.A. Guillain-Barré syndrome: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 10, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingues, R.B.; Fernandes, G.B.P.; Leite, F.B.V.D.M.; Tilbery, C.P.; Thomaz, R.B.; Silva, G.S.; Mangueira, C.L.P.; Soares, C.A.S. The cerebrospinal fluid in multiple sclerosis: Far beyond the bands. Einstein 2017, 15, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.H.; Jiang, D.; Huang, J.T. SARS-CoV-2 Detected in Cerebrospinal Fluid by PCR in a Case of COVID-19 Encephalitis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Saiegh, F.; Ghosh, R.; Leibold, A.; Avery, M.B.; Schmidt, R.F.; Theofanis, T.; Mouchtouris, N.; Philipp, L.; Peiper, S.C.; Wang, Z.-X.; et al. Status of SARS-CoV-2 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with COVID-19 and stroke. J. Neurol. Neurosurg Psychiatry 2020, 91, 846–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Gomes, J. Neuropathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Elife 2020, 9, e59136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Xu, Y.; Gao, R.; Lu, R.; Han, K.; Wu, G.; Tan, W. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Different Types of Clinical Specimens. JAMA 2020, 323, 1843–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, R.A.C.; Swan, A.V.; van Doorn, P.A. Intravenous immunoglobulin for Guillain-Barré syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 9, CD002063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raphaël, J.C.; Chevret, S.; Hughes, R.A.; Annane, D. Plasma exchange for Guillain-Barré syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2002, CD001798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.A.C.; Brassington, R.; Gunn, A.A.; van Doorn, P.A. Corticosteroids for Guillain-Barré syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 10, CD001446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).