Factors Associated with Withdrawal Time in European Colonoscopy Practice: Findings of the European Colonoscopy Quality Investigation (ECQI) Group

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Development

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Ethics

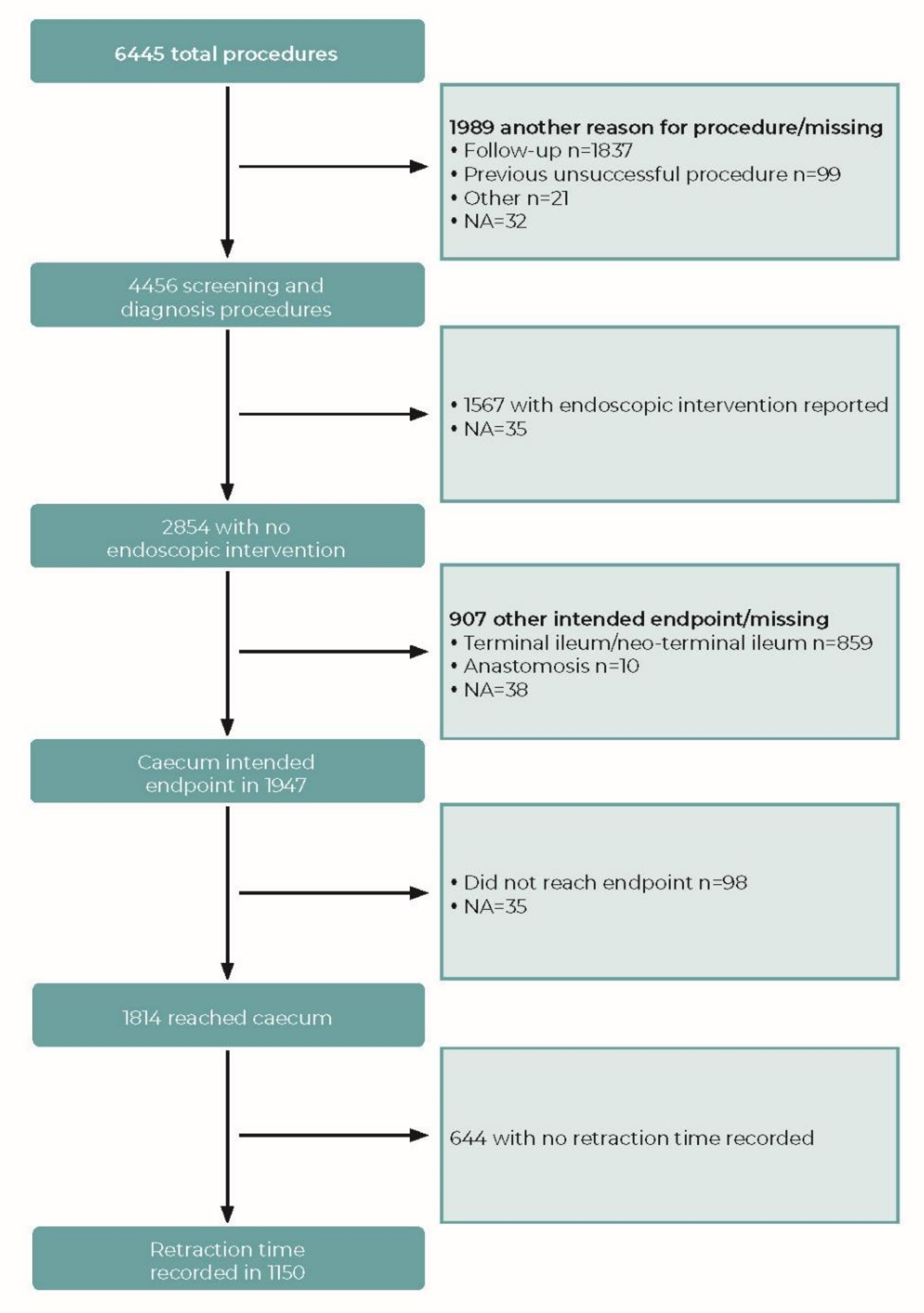

2.4. Dataset

2.5. Withdrawal Time

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

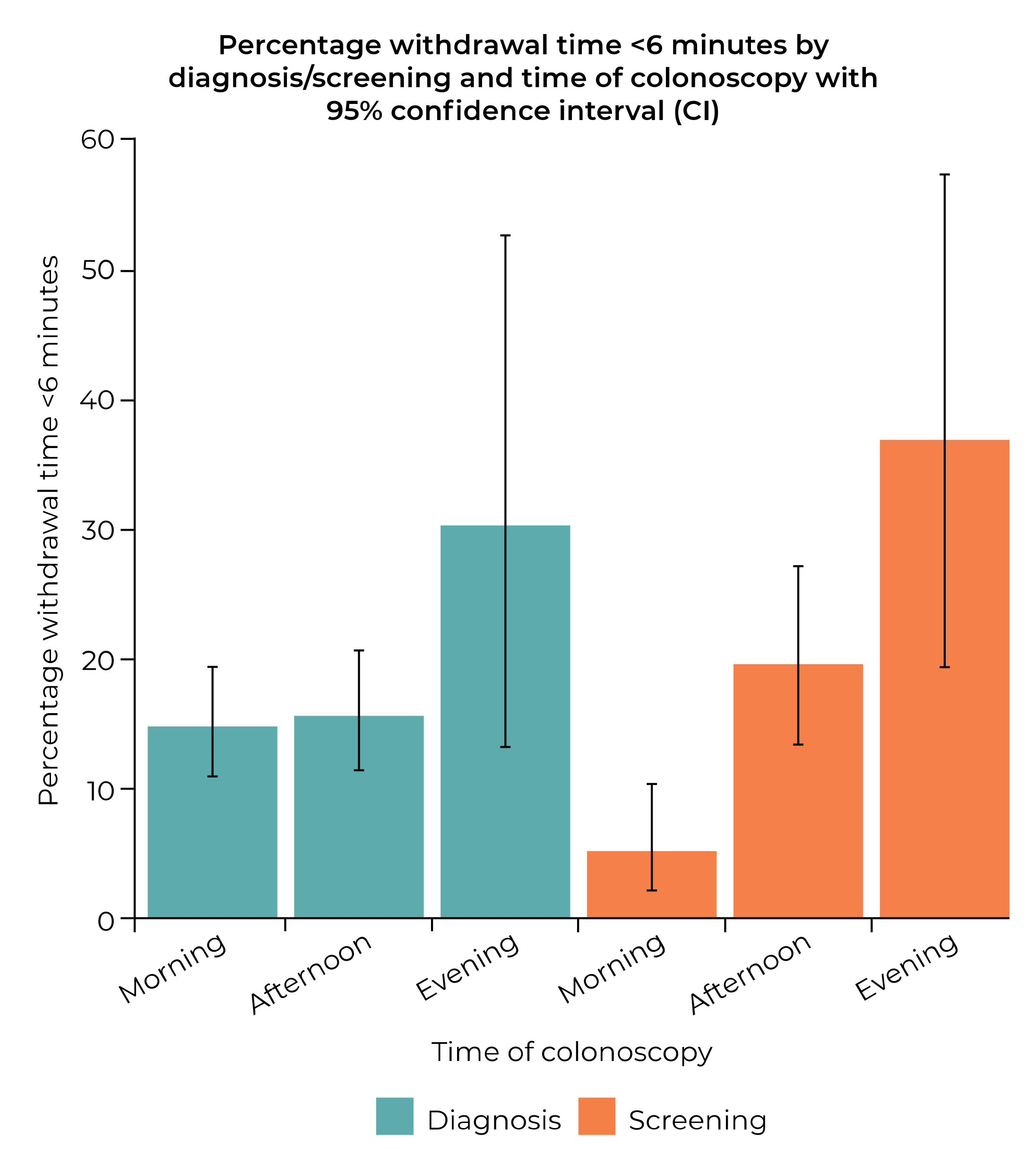

3.1. Withdrawal Time

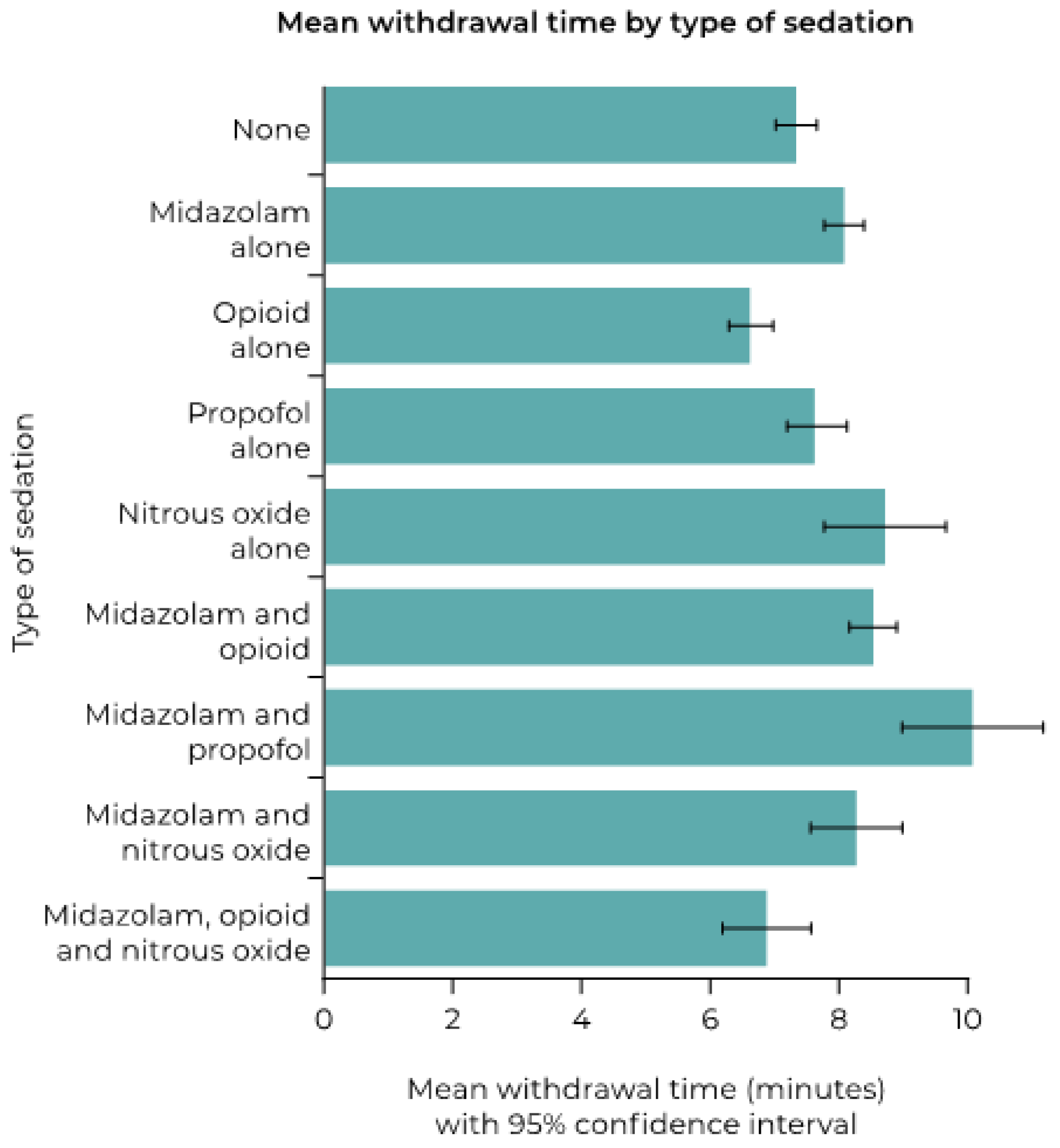

3.2. Impact of Sedation

4. Discussion

4.1. Multiple Imputation Analysis

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaminski, M.F.; Thomas-Gibson, S.; Bugajski, M.; Bretthauer, M.; Rees, C.J.; Dekker, E.; Hoff, G.; Jover, R.; Suchanek, S.; Ferlitsch, M.; et al. Performance measures for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy: A European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) quality improvement initiative. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2017, 5, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spada, C.; Koulaouzidis, A.; Hassan, C.; Amaro, P.; Agrawal, A.; Brink, L.; Fischbach, W.; Hünger, M.; Jover, R.; Kinnunen, U.; et al. Colonoscopy quality across Europe: A report of the European Colonoscopy Quality Investigation (ECQI) Group. Endosc. Int. Open 2021, 9, e1456–e1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rembacken, B.; Hassan, C.; Riemann, J.F.; Chilton, A.; Rutter, M.; Dumonceau, J.M.; Omar, M.; Ponchon, T. Quality in screening colonoscopy: Position statement of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE). Endoscopy 2012, 44, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemann, J.F.; Agrawal, A.; Amaro, P.; Brink, L.; Fischbach, W.; Hünger, M.; Jover, R.; Ono, A.; Toth, E.; Spada, C. Adoption of colonoscopy quality measures across Europe: The European Colonoscopy Quality Investigation (ECQI) Group experience. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2018, 6, 1106–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderwood, A.H.; Jacobson, B.C. Comprehensive validation of the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010, 72, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azur, M.J.; Stuart, E.A.; Frangakis, C.; Leaf, P.J. Multiple imputation by chained equations: What is it and how does it work? Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 20, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Marcondes, F.O.; Gourevitch, R.A.; Schoen, R.E.; Crockett, S.D.; Morris, M.; Mehrotra, A. Adenoma Detection Rate Falls at the End of the Day in a Large Multi-site Sample. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2018, 63, 856–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, T.Y.; Khor, S.N.; Kailasam, M.; Cheah, W.K.; Lau, C.C. Morning colonoscopies are associated with improved adenoma detection rates. Surg. Endosc. 2016, 30, 1796–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Dhawan, M.; Chowdhry, M.; Babich, M.; Aoun, E. Differences between morning and afternoon colonoscopies for adenoma detection in female and male patients. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2016, 29, 497–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Thosani, N.; Ladabaum, U.; Friedland, S.; Chen, A.M.; Kochar, R.; Banerjee, S. Adenoma miss rates associated with a 3-minute versus 6-minute colonoscopy withdrawal time: A prospective, randomized trial. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017, 85, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, A.; Rector, T.S.; Church, T.R.; Lederle, F.A.; Kim, A.S.; Rank, J.M.; Allen, J.I. Longer Withdrawal Time Is Associated With a Reduced Incidence of Interval Cancer After Screening Colonoscopy. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jover, R.; Zapater, P.; Polanía, E.; Bujanda, L.; Lanas, A.; Hermo, J.A.; Cubiella, J.; Ono, A.; González-Méndez, Y.; Peris, A.; et al. Modifiable endoscopic factors that influence the adenoma detection rate in colorectal cancer screening colonoscopies. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2013, 77, 381–389.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barclay, R.L.; Vicari, J.J.; Greenlaw, R.L. Effect of a time-dependent colonoscopic withdrawal protocol on adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 6, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, A.B.; Nielsen, O.H.; Hendel, J. Impact of feedback and monitoring on colonoscopy withdrawal times and polyp detection rates. BMJ Open. Gastroenterol. 2017, 4, e000142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Then, E.O.; Brana, C.; Dadana, S.; Maddika, S.; Ofosu, A.; Brana, S.; Wexler, T.; Sunkara, T.; Culliford, A.; Gaduputi, V. Implementing visual cues to improve the efficacy of screening colonoscopy: Exploiting the Hawthorne effect. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2020, 33, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, F.; Fukushima, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Kawakami, T.; Tanaka, R.; Kato, J.; Sato, A.; Konda, K.; Sugihara, K.; Baba, S. Individual feedback and monitoring of endoscopist performance improves the adenoma detection rate in screening colonoscopy: A prospective case-control study. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 2566–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.R.; Li, Z.; Shao, X.J.; Ji, C.R.; Ji, R.; Zhou, R.C.; Li, G.C.; Liu, G.Q.; He, Y.S.; Zuo, X.L.; et al. Impact of a real-time automatic quality control system on colorectal polyp and adenoma detection: A prospective randomized controlled study (with videos). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 91, 415–424.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yang, X.; Wang, S.; Meng, Q.; Wang, R.; Bo, L.; Chang, X.; Pan, P.; Xia, T.; Yang, F.; et al. Impact of 9-Minute Withdrawal Time on the Adenoma Detection Rate: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 20, e168–e181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes, G.; Andreozzi, P.; Omazzi, B.; Bezzio, C.; Redaelli, D.; Devani, M.; Morganti, D.; Reati, R.; Saibeni, S.; Mandelli, E.; et al. Efficacy of withdrawal time monitoring in adenoma detection with or without the aid of a full-spectrum scope. Endosc. Int. Open 2019, 7, E1135–E1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavricka, S.R.; Sulz, M.C.; Degen, L.; Rechner, R.; Manz, M.; Biedermann, L.; Beglinger, C.; Peter, S.; Safroneeva, E.; Rogler, G.; et al. Monitoring colonoscopy withdrawal time significantly improves the adenoma detection rate and the performance of endoscopists. Endoscopy 2016, 48, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parihar, V.; O’Leary, C.; O’Reagan, P. Timed colonoscopy withdrawal, a mandatory quality measure in the era of national screening? Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 187, 943–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, L.B.; Ladas, S.D.; Vargo, J.J.; Paspatis, G.A.; Bjorkman, D.J.; Van der Linden, P.; Axon, A.T.; Axon, A.E.; Bamias, G.; Despott, E.; et al. Sedation in digestive endoscopy: The Athens international position statements. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 32, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, H.; Poluha, W.; Cheung, M.; Choptain, N.; Baron, K.I.; Taback, S.P. Propofol for sedation during colonoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 4, CD006268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, O.S. Sedation for routine gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: A review on efficacy, safety, efficiency, cost and satisfaction. Intest. Res. 2017, 15, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triantafillidis, J.K.; Merikas, E.; Nikolakis, D.; Papalois, A.E. Sedation in gastrointestinal endoscopy: Current issues. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouda, B.; Gouda, G.; Borle, A.; Singh, A.; Sinha, A.; Singh, P.M. Safety of non-anesthesia provider administered propofol sedation in non-advanced gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: A meta-analysis. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, Y. Effect and safety of propofol for sedation during colonoscopy: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Anesth. 2018, 51, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, D.K.; Deenadayalu, V.P.; Eid, E.; Imperiale, T.F.; Walker, J.A.; Sandhu, K.; Clarke, A.C.; Hillman, L.C.; Horiuchi, A.; Cohen, L.B.; et al. Endoscopist-directed administration of propofol: A worldwide safety experience. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, A.; Frangopoulos, C.; Shaffer, L.E.T. Patient Satisfaction With Propofol for Outpatient Colonoscopy: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind Study. Dis. Colon Rectum 2017, 60, 1102–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakshabendi, R.; Berry, A.C.; Munoz, J.C.; John, B.K. Choice of sedation and its impact on adenoma detection rate in screening colonoscopies. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2016, 29, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Hoda, K.M.; Holub, J.L.; Eisen, G.M. Does level of sedation impact detection of advanced neoplasia? Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 2337–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Thirumurthi, S.; Raju, G.S.; Pande, M.; Ruiz, J.; Carlson, R.; Hagan, K.B.; Lee, J.H.; Ross, W.A. Does deep sedation with propofol affect adenoma detection rates in average risk screening colonoscopy exams? World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2017, 9, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Number | Mean ± SD | 95%CI | p Value for Variable | Mean p Value Following MI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient type | <0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| Outpatient | 942 | 7.7 ± 3.0 | 7.5, 7.9 | ||

| Inpatient | 98 | 9.0 ± 4.3 | 8.2, 9.9 | ||

| Missing | 110 | ||||

| Reason for procedure | <0.001 | NA | |||

| Diagnosis | 754 | 7.5 ± 2.7 | 7.3, 7.7 | ||

| Screening | 396 | 8.4 ± 3.7 | 8.1, 8.8 | ||

| Missing | 0 | ||||

| BBPS | 0.004 | 0.004 | |||

| BBPS < 6 | 142 | 8.5 ± 3.7 | 7.9, 9.2 | ||

| BBPS ≥ 6 | 998 | 7.7 ± 3.0 | 7.5, 7.9 | ||

| Missing | 10 | ||||

| Time colonoscopy performed | 0.015 | 0.098 | |||

| 07:00–11:59 | 415 | 7.8 ± 2.6 | 7.5, 8.0 | ||

| 12:00–17:59 | 385 | 7.4 ± 3.5 | 7.1, 7.8 | ||

| 18:00–19:59 | 50 | 6.5 ± 2.0 | 5.9, 7.1 | ||

| Missing | 300 | ||||

| Previous total colonoscopy in last 5 years | 0.018 | 0.020 | |||

| No | 875 | 7.7 ±3.1 | 7.5, 7.9 | ||

| Yes | 168 | 8.3 ± 3.5 | 7.8, 8.9 | ||

| Missing | 107 | ||||

| Sedation used | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 326 | 7.3 ± 3.1 | 6.9, 7.6 | ||

| Yes | 816 | 8.1 ± 3.1 | 7.8, 8.3 | ||

| Missing | 8 | ||||

| Variable | Proportion with Withdrawal Time > 10 min (%) | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | p Value | p Value for Variable | Mean p Value Following MI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient type | 0.005 | 0.021 | |||

| Outpatient | 94/942 (10.0) | Reference | |||

| Inpatient | 19/98 (19.4) | 2.170 (1.259, 3.739) | 0.005 | ||

| Missing | 110 | ||||

| Reason for procedure | <0.001 | NA | |||

| Diagnosis | 63/754 (8.4) | Reference | |||

| Screening | 61/396 (15.4) | 1.997 (1.372, 2.907) | <0.001 | ||

| Missing | 0 | ||||

| BBPS | 0.007 | 0.007 | |||

| BBPS < 6 | 25/142 (17.6) | Reference | |||

| BBPS ≥ 6 | 99/998 (9.9) | 0.515 (0.319, 0.832) | 0.007 | ||

| Missing | 10 | ||||

| Time colonoscopy performed | 0.479 | 0.561 | |||

| 07:00–11:59 | 44/415 (10.6) | Reference | |||

| 12:00–17:59 | 34/385 (8.8) | 0.817 (0.510, 1.308) | 0.399 | ||

| 18:00–19:59 | 3/50 (6.0) | 0.538 (0.161, 1.802) | 0.315 | ||

| Missing | 300 | ||||

| Previous total colonoscopy in last five years | 0.083 | 0.104 | |||

| No | 90/875 (10.3) | Reference | |||

| Yes | 25/168 (14.9) | 1.525 (0.946, 2.458) | 0.083 | ||

| Missing | 107 | ||||

| Sedation used | 0.002 | 0.002 | |||

| No | 20/326 (6.1) | Reference | |||

| Yes | 103/816 (12.6) | 2.210 (1.344, 3.634) | 0.002 | ||

| Missing | 8 | ||||

| Proportion with Withdrawal Time >10 min (%) | Odds Ratio (95%CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of sedation | <0.001 | ||

| None | 20/326 (6.1) | Reference | |

| Midazolam alone | 2/100 (2.0) | 0.312 (0.072, 1.360) | 0.121 |

| Opioid alone | 2/64 (3.1) | 0.494 (0.112, 2.166) | 0.349 |

| Propofol alone | 24/218 (11.0) | 1.893 (1.018, 3.519) | 0.044 |

| Nitrous oxide alone | 6/40 (15.0) | 2.700 (1.015, 7.185) | 0.047 |

| Midazolam and opioid | 55/323 (17.0) | 3.140 (1.835, 5.374) | <0.001 |

| Midazolam and propofol | 12/34 (35.3) | 8.345 (3.616, 19.259) | <0.001 |

| Midazolam and nitrous oxide | 0/11 (0) | 0 | – |

| Midazolam, opioid, and nitrous oxide | 0/15 (0) | 0 | – |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spada, C.; Koulaouzidis, A.; Hassan, C.; Amaro, P.; Agrawal, A.; Brink, L.; Fischbach, W.; Hünger, M.; Jover, R.; Kinnunen, U.; et al. Factors Associated with Withdrawal Time in European Colonoscopy Practice: Findings of the European Colonoscopy Quality Investigation (ECQI) Group. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12020503

Spada C, Koulaouzidis A, Hassan C, Amaro P, Agrawal A, Brink L, Fischbach W, Hünger M, Jover R, Kinnunen U, et al. Factors Associated with Withdrawal Time in European Colonoscopy Practice: Findings of the European Colonoscopy Quality Investigation (ECQI) Group. Diagnostics. 2022; 12(2):503. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12020503

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpada, Cristiano, Anastasios Koulaouzidis, Cesare Hassan, Pedro Amaro, Anurag Agrawal, Lene Brink, Wolfgang Fischbach, Matthias Hünger, Rodrigo Jover, Urpo Kinnunen, and et al. 2022. "Factors Associated with Withdrawal Time in European Colonoscopy Practice: Findings of the European Colonoscopy Quality Investigation (ECQI) Group" Diagnostics 12, no. 2: 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12020503

APA StyleSpada, C., Koulaouzidis, A., Hassan, C., Amaro, P., Agrawal, A., Brink, L., Fischbach, W., Hünger, M., Jover, R., Kinnunen, U., Ono, A., Patai, Á., Pecere, S., Petruzziello, L., Riemann, J. F., Staines, H., Stringer, A. L., Toth, E., Antonelli, G., & Fuccio, L., on behalf of the ECQI Group. (2022). Factors Associated with Withdrawal Time in European Colonoscopy Practice: Findings of the European Colonoscopy Quality Investigation (ECQI) Group. Diagnostics, 12(2), 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12020503