COVID-19 Syndemic: Convergence of COVID-19, Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CAPA), Pulmonary Tuberculosis, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, and Arterial Hypertension

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Pulmonary Microbial Infections

1.1.1. Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis (IPA)

1.1.2. COVID-19-Associated Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CAPA)

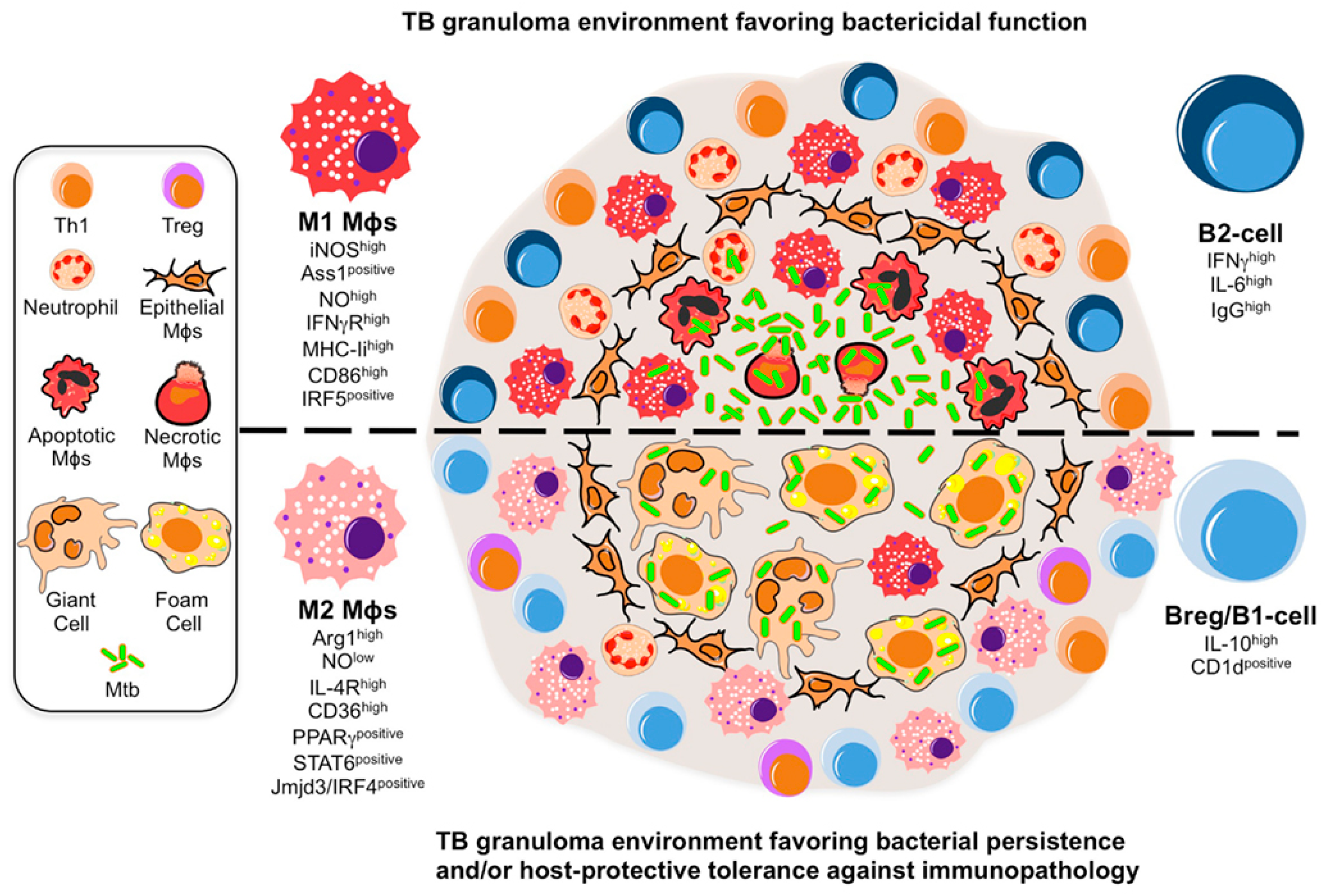

1.1.3. Pulmonary Tuberculosis (PTB)

1.2. COVID-19 and Comorbidities

1.3. Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Definition of CAPA (2020 ISHAM/ECMM Consensus Definitions)

- (A).

- Proven CAPA is defined as pulmonary or tracheobronchial infection. It is proven by either or both histopathological and direct microscopic detection of fungal elements morphologically consistent with Aspergillus spp. that show invasive growth into tissues with associated tissue damage, either alone or in combination with Aspergillus recovered by culture, detected by microscopy in histology studies, or detected by PCR from material obtained by sterile aspiration or biopsy from a pulmonary site.

- (B).

- Probable CAPA involves the presence of tracheobronchial ulceration, nodule, pseudo-membrane, plaque, or eschar, alone or in combination, on bronchoscopic analysis and mycological evidence by positive culture for Aspergillus. Probable pulmonary CAPA also required a pulmonary infiltrate or nodules, preferably documented by chest CT, or cavitating infiltrate (not attributed to another cause), or both, combined with mycological evidence, serum GM index > 0.5, and clinical criteria. Detection of GM in NBL is considered to be evidence for CAPA.

- (C).

- Possible CAPA: In the setting of COVID-19 and in view of the challenges related to CAPA diagnosis, this category requires pulmonary infiltrate or nodules, preferably documented by chest CT, or cavitating infiltrate (which is not attributed to another cause) in combination with mycological evidence (e.g., microscopy, culture, or GM, alone or in combination) obtained via NBL, including those who have undergone NBL to obtain mycological evidence.

2.3. Definition of Diabetes, Obesity, and Hypertension

3. Case Report

3.1. Case Report 1

3.2. Case Report 2

3.3. Case Report 3

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singer, M.; Clair, S. Syndemics and public health: Reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Med Anthr. Q 2003, 17, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, R. Offline: After COVID-19-is an “alternate society” possible? Lancet 2020, 395, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderbeke, L.; Janssen, N.A.F.; Bergmans, D.; Bourgeois, M.; Buil, J.B.; Debaveye, Y.; Depuydt, P.; Feys, S.; Hermans, G.; Hoiting, O.; et al. Posaconazole for prevention of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill influenza patients (POSA-FLU): A randomised, open-label, proof-of-concept trial. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verweij, P.E.; Bruggemann, R.J.M.; Azoulay, E.; Bassetti, M.; Blot, S.; Buil, J.B.; Calandra, T.; Chiller, T.; Clancy, C.J.; Cornely, O.A.; et al. Taskforce report on the diagnosis and clinical management of COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, P.; Bassetti, M.; Chakrabarti, A.; Chen, S.C.A.; Colombo, A.L.; Hoenigl, M.; Klimko, N.; Lass-Florl, C.; Oladele, R.O.; Vinh, D.C.; et al. Defining and managing COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: The 2020 ECMM/ISHAM consensus criteria for research and clinical guidance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 21, E149–E162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoli, A.; Falahi, S.; Kenarkoohi, A. COVID-19-associated opportunistic infections: A snapshot on the current reports. Clin. Exp. Med. 2021, 22, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, N.E.; Bass, J.; Fujiwara, P.; Hopewell, P.; Horsburgh, C.R.; Salfinger, M.; Simone, P.M.; Tuber, S.A.M. Diagnostic standards and classification of tuberculosis in adults and children. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care 2000, 161, 1376–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, R.L.S. Tuberculosis 2: Pathophysiology and microbiology of pulmonary tuberculosis. SSMJ 2013, 6, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, P.T.; Ugarte-Gil, C.A.; Friedland, J.S. Matrix metalloproteinases in tuberculosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 38, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, I. Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis and molecular determinants of virulence. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 16, 463–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moule, M.G.; Cirillo, J.D. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Dissemination Plays a Critical Role in Pathogenesis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrickson, E.M. Associations between Ever-Smoking and Tuberculosis among Hispanics Residing in the United States; San Diego State University: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Corti, A.; Franzini, M.; Scataglini, I.; Pompella, A. Mechanisms and targets of the modulatory action of S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) on inflammatory cytokines expression. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 562, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugo-Villarino, G.; Hudrisier, D.; Benard, A.; Neyrolles, O. Emerging trends in the formation and function of tuberculosis granulomas. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glickman, M.S.; Jacobs, W.R. Microbial pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Dawn of a discipline. Cell 2001, 104, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franssen, F.M.; Vanfleteren, L. Differential diagnosis and impact of cardiovascular comorbidities and pulmonary embolism during COPD exacerbations. In ERS Monograph: Acute Exacerbations of Pulmonary Diseases; European Respiratory Society: Sheffield, UK, 2017; pp. 114–128. [Google Scholar]

- Apicella, M.; Campopiano, M.C.; Mantuano, M. COVID-19 in people with diabetes: Understanding the reasons for worse outcomes. Lancet. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamming, I.; Timens, W.; Bulthuis, M.L.C.; Lely, A.T.; Navis, G.J.; van Goor, H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J. Pathol. 2004, 203, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez-Camacho, J.R.; Avila-Carrasco, L.; Murillo-Ruiz-Esparza, A.; Garza-Veloz, I.; Araujo-Espino, R.; Martinez-Vazquez, M.C.; Trejo-Ortiz, P.M.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, I.P.; Delgado-Enciso, I.; Castaneda-Lopez, M.E.; et al. Evaluation of the Potential Risk of Mortality from SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Hospitalized Patients According to the Charlson Comorbidity Index. Healthc 2022, 10, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miners, S.; Kehoe, P.G.; Love, S. Cognitive impact of COVID-19: Looking beyond the short term. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igase, M.; Strawn, W.B.; Gallagher, P.E.; Geary, R.L.; Ferrario, C.M. Angiotensin II AT(1) receptors regulate ACE2 and angiotensin-(1-7) expression in the aorta of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005, 289, H1013–H1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besler, M.S.; Arslan, H. Acute myocarditis associated with COVID-19 infection. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 2489.e1–2489.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhatariya, K.K.; Vellanki, P. Treatment of Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA)/Hyperglycemic Hyperosmolar State (HHS): Novel Advances in the Management of Hyperglycemic Crises (UK Versus USA). Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2017, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Unger, T.; Borghi, C.; Charchar, F.; Khan, N.A.; Poulter, N.R.; Prabhakaran, D.; Ramirez, A.; Schlaich, M.; Stergiou, G.S.; Tomaszewski, M.; et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2020, 75, 1334–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, S17–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee; Draznin, B.; Aroda, V.R.; Bakris, G.; Benson, G.; Brown, F.M.; Freeman, R.; Green, J.; Huang, E.; Isaacs, D.; et al. 16. Diabetes Care in the Hospital: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, S244–S253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee; Draznin, B.; Aroda, V.R.; Bakris, G.; Benson, G.; Brown, F.M.; Freeman, R.; Green, J.; Huang, E.; Isaacs, D.; et al. 8. Obesity and Weight Management for the Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, S113–S124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Treatment; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- De Salud, S.; de México, G. Lineamientos de Manejo General y Masivo de Cadáveres por COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) en México; Gobierno de México-Secretaria de Salud: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2020; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, M.; Herrera, T.; Villareal, H.; Rich, E.A.; Sada, E. Cytokine profiles for peripheral blood lymphocytes from patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis and healthy household contacts in response to the 30-kilodalton antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.; Mendez-Sampeiro, P.; Jimenez-Zamudio, L.; Teran, L.; Camarena, A.; Quezada, R.; Ramos, E.; Sada, E.J.C.; Immunology, E. Comparison of the immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens between a group of patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis and healthy household contacts. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1994, 96, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miro, M.S.; Vigezzi, C.; Rodriguez, E.; Icely, P.A.; Caeiro, J.P.; Riera, F.; Masih, D.T.; Sotomayor, C.E. Innate receptors and IL-17 in the immune response against human pathogenic fungi. Rev. Fac. Cien. Med. Univ. Nac. Cordoba. 2016, 73, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Shi, J.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, H. Therapy Targets SARS-CoV-2 Infection-Induced Cell Death. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 870216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targownik, L.E.; Fisher, D.A.; Saini, S.D. AGA Clinical Practice Update on De-Prescribing of Proton Pump Inhibitors: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 1334–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.; El Baz, Y.; Graf, N.; Wildermuth, S.; Leschka, S.; Kleger, G.R.; Pietsch, U.; Frischknecht, M.; Scanferla, G.; Strahm, C.; et al. Clinical and Imaging Features of COVID-19-Associated Pulmonary Aspergillosis. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmanton-Garcia, J.; Sprute, R.; Stemler, J.; Bartoletti, M.; Dupont, D.; Valerio, M.; Garcia-Vidal, C.; Falces-Romero, I.; Machado, M.; de la Villa, S.; et al. COVID-19-Associated Pulmonary Aspergillosis, March–August 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.; Cho, S.Y.; Lee, D.G.; Ahn, H.; Choi, H.; Choi, S.M.; Choi, J.K.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; et al. Risk factors and clinical impact of COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: Multicenter retrospective cohort study. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadolini, M.; Codecasa, L.R.; Garcia-Garcia, J.M.; Blanc, F.X.; Borisov, S.; Alffenaar, J.W.; Andrejak, C.; Bachez, P.; Bart, P.A.; Belilovski, E.; et al. Active tuberculosis, sequelae and COVID-19 co-infection: First cohort of 49 cases. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2001398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Ish, P.; Gupta, A.; Malhotra, N.; Caminero, J.A.; Singla, R.; Kumar, R.; Yadav, S.R.; Dev, N.; Agrawal, S.; et al. A profile of a retrospective cohort of 22 patients with COVID-19 and active/treated tuberculosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2003408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sereda, Y.; Korotych, O.; Klimuk, D.; Zhurkin, D.; Solodovnikova, V.; Grzemska, M.; Grankov, V.; Hurevich, H.; Yedilbayev, A.; Skrahina, A. Tuberculosis Co-Infection Is Common in Patients Requiring Hospitalization for COVID-19 in Belarus: Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaila, R.G. Voriconazole and the liver. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 1828–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, M.G.; Carbajal, C.M.; Urrutia, M.I. Influenza, SARS-CoV-2 and Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2021, 57, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, P.E.; Rijnders, B.J.; Brüggemann, R.J.; Azoulay, E.; Bassetti, M.; Blot, S.; Calandra, T.; Clancy, C.J.; Cornely, O.A.; Chiller, T.; et al. Review of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis in ICU patients and proposal for a case definition: An expert opinion. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1524–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Agolli, A.; da Costa Rocha, M.; Riquieri Nunes, L.; Girish Mistry, H.; Hemant Patel, Z.; Adhvaryu, M.; Agolli, O.; Sikandarbhai Vahora, I.; Paresh Bhatt, K.; et al. Correlation of Diabetes Mellitus and COVID-19: A Review. Diabetes Its Complicat. 2021, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, L.L.; Rothenberg, S.J.; Ortega, Á.M.; Loira, B.L.G.; Collado, G.F.; Moreno, K.F.R.; García, M.K.F.; Ruiz, R.C. Contaminación ambiental, estilo de vida y cáncer mamario. Inst. Nac. Salud Pública 2020, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.; Bae, J.H.; Kwon, H.-S.; Nauck, M.A. COVID-19 and diabetes mellitus: From pathophysiology to clinical management. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| COVID-19 and CAPA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study, total cases, reference | Mean age (±SD or IQR) and percentage by gender | CAPA total Percentage and by gender (x/n) if available | Comorbidities and other pre-existing condition Percentage from total CAPA | Anti-COVID-19 treatment Percentage from total CAPA | ANF treatment | Outcome |

| Case-control, 65 COVID-19 cases, Tim Fischer et al., 2022 [35]. | 64.8 (±9.5) years, M: 74% (48/65), F: 26% (17/65) | CAPA: 20% (13/65), M: 54% (7/13), F: 46% (6/13) | ST: 62% (8/13) BWT: 62% (8/13) COPD: 15% (2/13) H 62% (8/13) CHD: 46% (6/13) CVA: 31% (4/13) DM: 31% (4/13) H: 61.5% (8/13) | S: 100% (13/13) IMD: 15% (2/13) Antiviral 8% (1/13) | No use of antifungal was reported in this study | tendency for consolidation in early COVID-19 disease Bacterial superinfection 77% (10/13) |

| Retrospective study, 221 COVID-19 cases, Jon Salmanton et al., 2021 [36]. | 68 (IQR 58–73) years, Not specified gender | CAPA: 84% (186/221), M: 73% (135/186), F: 27% (51/186) | Aspergillus fumigatus: 66% (122/186) A. niger: 7% (13/186) A. flavus: 5% (10/186) A. terrenus: 3% (6/186) CHD: 51% (94/186) RF: 40% (74/186) DM 34% (64/186) | C: 53% (98/186) | ANF: 74% (137/186) AB: 19% (36/186) E: 12.9% (24/186) T: 62.9% (117/186) | Overall mortality 52.2% (97/186) Cause of death CAPA 17.2% (32/186) COVID-19 (27.4% (51/186) |

| Multicenter retrospective study, 218 COVID-19 cases, Raeseok Lee et al., 2022 [37]. | 62 (49–72) years, M: 53% (116/218), F: 46.7% (102/218) | CAPA: 5% (10/128), M: 50% (5/10), F: 50% (5/10) | COPD 20% (2/10) TB 0% (0/10) DM 0% (0/10) CKD 20% (2/10) CAD 10% (1/10) CVA 0% (0/10) | C: 100% (10/10) | No use of antifungal was reported in this study | Overall in-hospital mortality 12% (26/218), higher rate in CAPA In hospital mortality 50% (5/10) |

| COVID-19 and TB | ||||||

| Study/total cases/reference | Mean age (± SD or IQR) and percentage by gender | TB Total Percentage ”n” and by gender (x/n) if available | Underlying diseases or pre-existing condition Percentage from total TB | Anti-COVID-19 treatment Percentage from total TB | ATT | Outcome |

| Cohorts study, 49 TB/COVID-19 cases, Tadolini M et al., 2020 [38]. | 48 (32–69) years, M: 82% (40/49), F: 18% (9/49). | TB before COVID-19: 53% (26/49), COVID-19 before TB: 29% (14/49); diagnosed within the same week: 18% (9/49); on the same day: 8% (4/49) | COPD: 17% (8/47) DM: 16% (8/49) HIV: 13% (6/48) RF: 10% (5/49) LD: 14% (7/49) AA: 20% (10/49) SMK: 41% (20/49) | Overall: 57% (28/49), HCQ: 78% (22/28), A-HIV-PI: 43% (12/28), AZ: 25% (7/28) | Standard first-line regimen: 76% (37/49). Second-line drugs: 16% (8/49) | Cured: 12% (6/49), Completed: 2% (1/49), On treatment: 76% (37/49), Died: 10% (5/49) |

| Retrospective observational study, 1073 COVID-19 cases, Gupta et al., 2020 [39]. | 40.59 (19–67) years Active TB: 36 (27–59.5) years Treated TB: 44 (28–51) years | Active/treated TB: 2% (22/1073), Active TB: 59% (13/22), F: 85% (11/13) Treated TB: 41% (9/22) F: 100% (9/9) | H: 18% (4/22) HT: 5% (1/22) DM: 14% (3/22) SD: 9% (2/22) | Any especial COVID-19 treatment was mentioned in this study | Conventional ATT: 92% (12/13) Conventional MDR: 8% (1/13) | Died 27% (6/22), Discharged 73% (16/22) Deaths attributed to COVID-19 co-infection |

| Secondary analysis of health records, 844 COVID-19 cases, Yuliia Sereda et al., 2022 [40]. | 43.5 (15.6) years M: 64% (540/844) F: 36% (304/844) | MTB detected: 6% (47/844) M: 77% (36/47) F: 23% (11/47) | HTB: 15% (7/47) HIV: 4% (2/47) DM: 4% (2/47) Other: 49% (23/47) | Any especial COVID-19 treatment was mentioned in this study | History of ATT: 25% (12/47) | Overall IHM: 2% (19/844) COVID-19: 2% (18/797) COVID-19/TB: 2% (1/47) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Badillo-Almaraz, J.I.; Cardenas-Cadena, S.A.; Gutierrez-Avella, F.D.; Villegas-Medina, P.J.; Garza-Veloz, I.; Almaraz, V.B.; Martinez-Fierro, M.L. COVID-19 Syndemic: Convergence of COVID-19, Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CAPA), Pulmonary Tuberculosis, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, and Arterial Hypertension. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2058. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12092058

Badillo-Almaraz JI, Cardenas-Cadena SA, Gutierrez-Avella FD, Villegas-Medina PJ, Garza-Veloz I, Almaraz VB, Martinez-Fierro ML. COVID-19 Syndemic: Convergence of COVID-19, Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CAPA), Pulmonary Tuberculosis, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, and Arterial Hypertension. Diagnostics. 2022; 12(9):2058. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12092058

Chicago/Turabian StyleBadillo-Almaraz, Jose Isaias, Sergio Andres Cardenas-Cadena, Fausto Daniel Gutierrez-Avella, Pedro Javier Villegas-Medina, Idalia Garza-Veloz, Valentin Badillo Almaraz, and Margarita L Martinez-Fierro. 2022. "COVID-19 Syndemic: Convergence of COVID-19, Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CAPA), Pulmonary Tuberculosis, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, and Arterial Hypertension" Diagnostics 12, no. 9: 2058. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12092058

APA StyleBadillo-Almaraz, J. I., Cardenas-Cadena, S. A., Gutierrez-Avella, F. D., Villegas-Medina, P. J., Garza-Veloz, I., Almaraz, V. B., & Martinez-Fierro, M. L. (2022). COVID-19 Syndemic: Convergence of COVID-19, Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CAPA), Pulmonary Tuberculosis, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, and Arterial Hypertension. Diagnostics, 12(9), 2058. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12092058