Blood pH Changes in Dental Pulp of Patients with Pulpitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

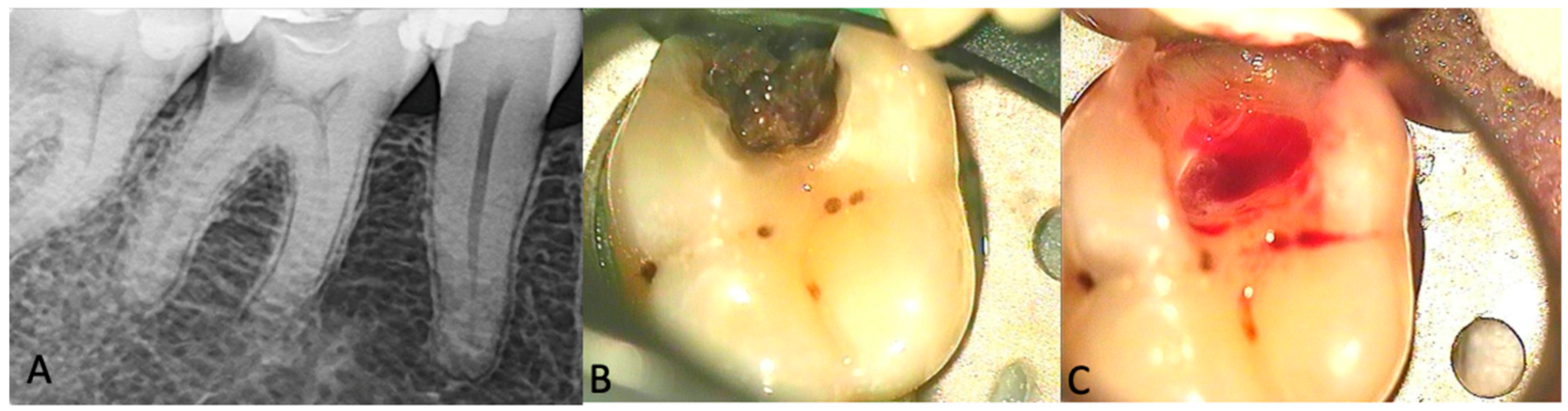

2.2. Clinical Procedures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

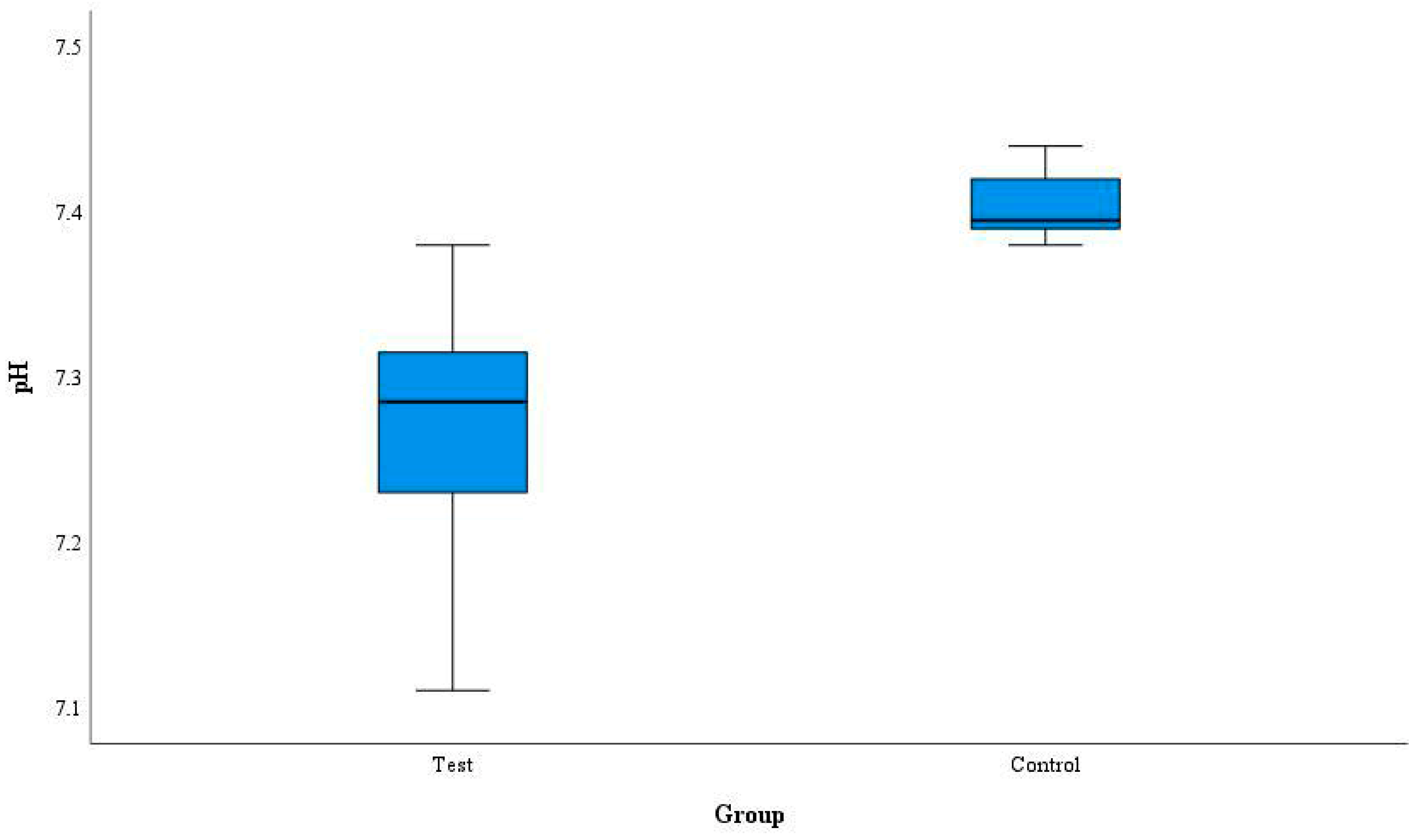

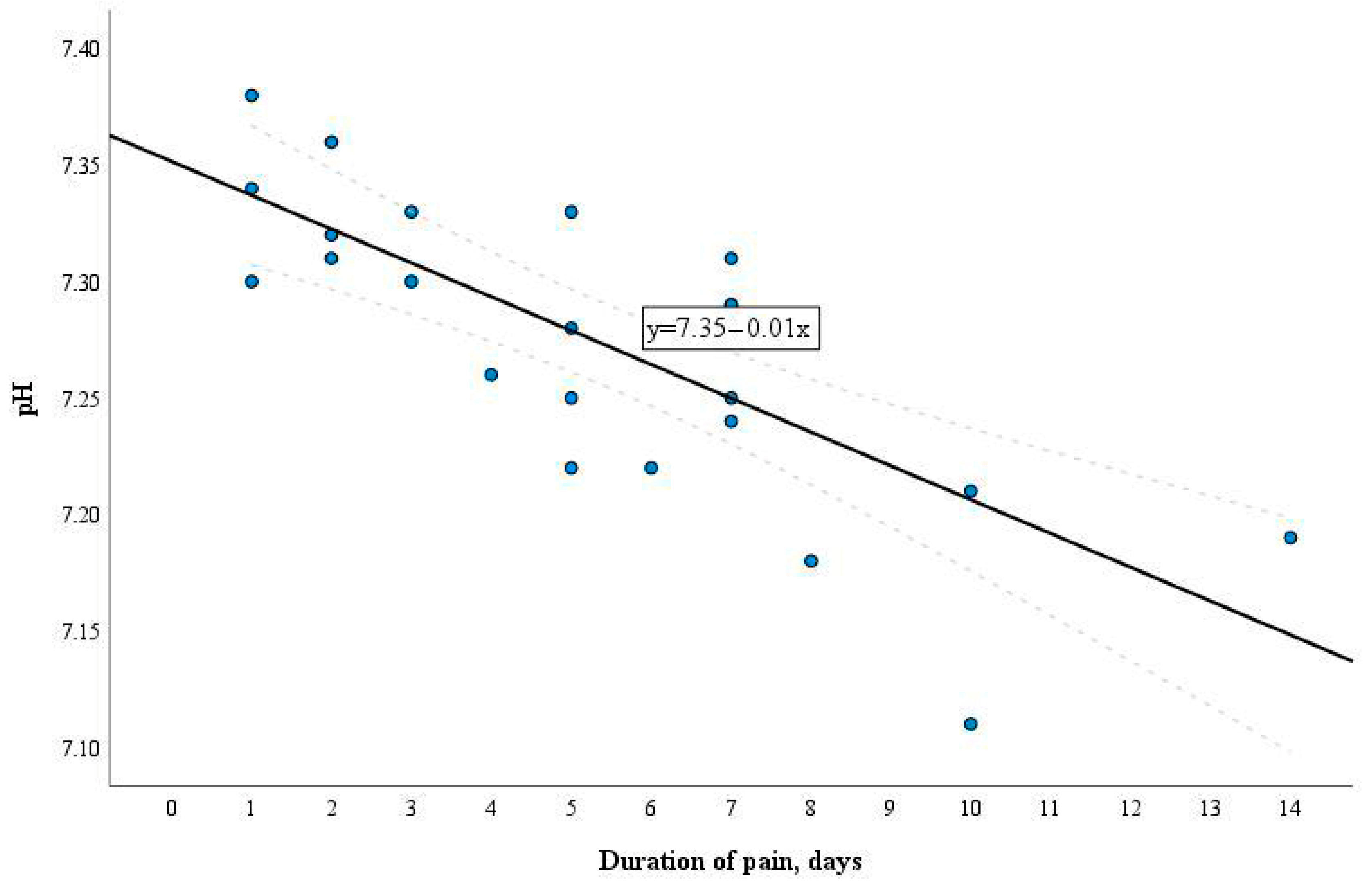

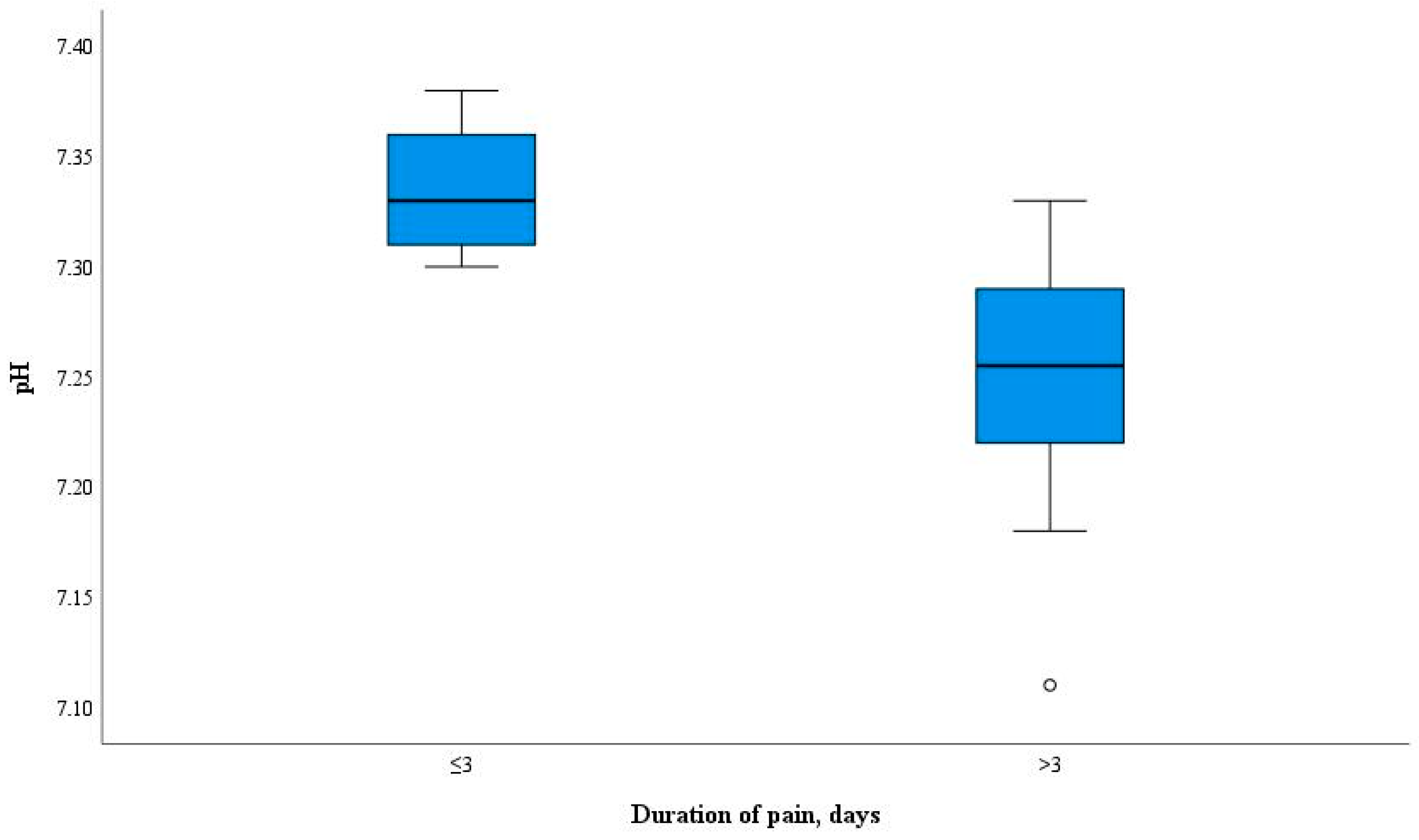

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hahn, C.L.; Falkler, W.A., Jr.; Minah, G.E. Microbiological studies of carious dentine from human teeth with irreversible pulpitis. Arch. Oral. Biol. 1991, 36, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Society of Endodontology (ESE); Duncan, H.F.; Galler, K.M.; Tomson, P.L.; Simon, S.; El-Karim, I.; Kundzina, R.; Krastl, G.; Dammaschke, T.; Fransson, H.; et al. European Society of Endodontology position statement: Management of deep caries and the exposed pulp. Int. Endod. J. 2019, 52, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wolters, W.J.; Duncan, H.F.; Tomson, P.L.; Karim, I.E.; McKenna, G.; Dorri, M.; Stangvaltaite, L.; van der Sluis, L.W.M. Minimally invasive endodontics: A new diagnostic system for assessing pulpitis and subsequent treatment needs. Int. Endod. J. 2017, 50, 825–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricucci, D.; Loghin, S.; Siqueira, J.F., Jr. Correlation between clinical and histologic pulp diagnoses. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 1932–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, N.A.; Ahmad, M.B.; Ghanim, A. Assessment of Mineral Trioxide Aggregate pulpotomy in mature permanent teeth with carious exposures. Int. Endod. J. 2017, 50, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.; Abbott, P.V. Dental pulp testing: A review. Int. J. Dent. 2009, 2009, 365785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejàre, I.A.; Axelsson, S.; Davidson, T.; Frisk, F.; Hakeberg, M.; Kvist, T.; Norlund, A.; Petersson, A.; Portenier, I.; Sandberg, H.; et al. Diagnosis of the condition of the dental pulp: A systematic review. Int. Endod. J. 2012, 45, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghouth, N.; Duggal, M.S.; BaniHani, A.; Nazzal, H. The diagnostic accuracy of laser Doppler flowmetry in assessing pulp blood flow in permanent teeth: A systematic review. Dent. Traumatol. 2018, 34, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igna, A.; Mircioagă, D.; Boariu, M.; Stratul, Ș.I. A Diagnostic Insight of Dental Pulp Testing Methods in Pediatric Dentistry. Medicina 2022, 58, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Almudever-Garcia, A.; Forner, L.; Sanz, J.L.; Llena, C.; Rodríguez-Lozano, F.J.; Guerrero-Gironés, J.; Melo, M. Pulse Oximetry as a Diagnostic Tool to Determine Pulp Vitality: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechenberg, D.K.; Galicia, J.C.; Peters, O.A. Biological Markers for Pulpal Inflammation: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrar, R.N.; Cushley, S.; Duncan, H.F.; Lundy, F.T.; Abushouk, S.A.; Clarke, M.; El-Karim, I.A. Molecular biomarkers for objective assessment of symptomatic pulpitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Endod. J. 2023, 56, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauschenberger, C.R.; McClanahan, S.B.; Pederson, E.D.; Turner, D.W.; Kaminski, E.J. Comparison of human polymorphonuclear neutrophil elastase, polymorphonuclear neutrophil cathepsin-G, and alpha 2-macroglobulin levels in healthy and inflamed dental pulps. J. Endod. 1994, 20, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, H.F. Present status and future directions-vital pulp treatment and pulp preservation strategies. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusman, H.; Santana, R.B.; Zehnder, M. Matrix metalloproteinase levels and gelatinolytic activity in clini- cally healthy and inflamed human dental pulps. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 2002, 110, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mente, J.; Petrovic, J.; Gehrig, H.; Rampf, S.; Michel, A.; Schürz, A.; Pfefferle, T.; Saure, D.; Erber, R. A Prospective Clinical Pilot Study on the Level of Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 in Dental Pulpal Blood as a Marker for the State of Inflammation in the Pulp Tissue. J. Endod. 2016, 42, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuroiu, C.L.; Căruntu, I.D.; Lozneanu, L.; Melian, A.; Vataman, M.; Andrian, S. Dental Pulp: Correspondences and Contradictions between Clinical and Histological Diagnosis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 960321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Cheng, L.; Yang, H.; Zou, W.; Cheng, R.; Hu, T. Lysophosphatidic acid rescues human dental pulp cells from ischemia-induced apoptosis. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Jiang, H.; Wei, X.; Ling, J.; Wang, J. Expression of erythropoietin and erythropoietin receptor in human dental pulp. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 1972–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodis, H.E.; Poon, A.; Hargreaves, K.M. Tissue pH and temperature regulate pulpal nociceptors. J. Dent. Res. 2006, 85, 1046–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, A.; Guelmann, M.; Tickotsky, N.; Ninio-Harush, R.; Noy, A.F.; Moskovitz, M. Blood Gas Tension and Acidity Level of Caries Exposed Vital Pulps in Primary Molars. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2020, 44, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, E.; Sanvictores, T.; Sharma, S. Physiology, Acid Base Balance. [Updated 12 September 2022]. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507807/ (accessed on 3 February 2024).

- Gopinath, V.K.; Anwar, K. Histological evaluation of pulp tissue from second primary molars correlated with clinical and radiographic caries findings. Dent. Res. J. 2014, 11, 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Dastpak, M.; Ghoddusi, J.; Jafarian, A.H.; Sarmad, M. Association between Clinical Symptoms and Histological Features of Molars with Acute Pulpitis. Iran. Endod. J. 2023, 18, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alqaderi, H.E.; Al-Mutawa, S.A.; Qudeimat, M.A. MTA pulpotomy as an alternative to root canal treatment in children’s permanent teeth in a dental public health setting. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 1390–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgary, S.; Parhizkar, A. Importance of “Time” on “Haemostasis” in Vital Pulp Therapy–Letter to the Editor. Eur. Endod. J. 2021, 6, 128–129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mutluay, M.; Arıkan, V.; Sarı, S.; Kısa, Ü. Does Achievement of Hemostasis After Pulp Exposure Provide an Accurate Assessment of Pulp Inflammation? Pediatr. Dent. 2018, 40, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El Karim, I.A.; Duncan, H.F.; Fouad, A.F.; Taha, N.A.; Yu, V.; Saber, S.; Ballal, V.; Chompu-Inwai, P.; Ahmed, H.M.A.; Gomes, B.P.F.A.; et al. Effectiveness of full Pulpotomy compared with Root canal treatment in managing teeth with signs and symptoms indicative of irreversible pulpitis: A protocol for prospective meta-analysis of individual participant data of linked randomised clinical trials (PROVE). Trials 2023, 24, 807. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Vásquez, J.L.; Castañeda-Alvarado, C.P. Dental Pulp Fibroblast: A Star Cell. J. Endod. 2022, 48, 1005–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LAQUAtwin ph-33 (No Date) HORIBA. Available online: https://www.horiba.com/sgp/waterquality/products/detail/action/show/Product/laquatwin-ph-33-873 (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Baliga, S.; Muglikar, S.; Kale, R. Salivary pH: A diagnostic biomarker. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2013, 17, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzureanu, P.C.; Popescu, F.; Tudor, A.; Stef, L.; Negru, A.G.; Mihăilă, R. Saliva pH and Flow Rate in Patients with Periodontal Disease and Associated Cardiovascular Disease. Med. Sci. Monit. 2021, 27, e931362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, L.L.; Nakhoul, N.; Hering-Smith, K.S. Acid-base homeostasis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 10, 2232–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzorno, J. Acidosis: An old idea validated by new research. Integr. Med. 2015, 14, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.S.; Lee, S.P.; Huang, S.F.; Chao, S.C.; Chang, C.Y.; Wu, G.J.; Li, C.H.; Loh, S.H. Functional and molecular characterization of transmembrane intracellular pH regulators in human dental pulp stem cells. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2018, 90, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajjar, S.; Zhou, X. pH sensing at the intersection of tissue homeostasis and inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2023, 44, 807–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajamäki, K.; Nordström, T.; Nurmi, K.; Åkerman, K.E.; Kovanen, P.T.; Öörni, K.; Eklund, K.K. Extracellular acidosis is a novel danger signal alerting innate immunity via the NLRP3 inflammasome. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 13410–13419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galler, K.M.; Weber, M.; Korkmaz, Y.; Widbiller, M.; Feuerer, M. Inflammatory response mechanisms of the dentine-pulp complex and the periapical tissues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barkhordar, R.A.; Hayashi, C.; Hussain, M.Z. Detection of interleukin-6 in human dental pulp and periapical lesions. Endod. Dent. Traumatol. 1999, 15, 26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyeraas, K.J.; Berggreen, E. Interstitial fluid pressure in normal and inflamed pulp. Crit. Rev. Oral. Biol. Med. 1999, 10, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dag, Ø. Apical Periodontitis: Microbial Infection and Host Responses. In Essential Endodontology; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, E.; Gaudin, A.; Bienvenu, G.; Amiaud, J.; Farges, J.C.; Cuturi, M.C.; Moreau, A.; Alliot-Licht, B. Immune Cells and Molecular Networks in Experimentally Induced Pulpitis. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Bahuguna, R. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in dental caries, pulp and periapical inflammation: An overview. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2015, 5, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stashenko, P.; Teles, R.; D’Souza, R. Periapical inflammatory responses and their modulation. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1998, 9, 498–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mjör, I.A.; Tronstad, L. Experimentally induced pulpitis. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1972, 34, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, R.; Stanley, H.R. The relationship of bacterial penetration and pulpal pathosis in carious teeth. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1966, 22, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-G.; Lin, J.-J.; Wang, Z.-L.; Cai, W.-K.; Wang, P.-N.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, A.S.; Wu, G.Y.; Zhu, G.X.; Ni, L.X. Melatonin attenuates inflammation of acute pulpitis subjected to dental pulp injury. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2015, 7, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hosseinzadehfard, P.; Skučaitė, N.; Maciulskiene-Visockiene, V.; Lodiene, G. Blood pH Changes in Dental Pulp of Patients with Pulpitis. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111128

Hosseinzadehfard P, Skučaitė N, Maciulskiene-Visockiene V, Lodiene G. Blood pH Changes in Dental Pulp of Patients with Pulpitis. Diagnostics. 2024; 14(11):1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111128

Chicago/Turabian StyleHosseinzadehfard, Pedram, Neringa Skučaitė, Vita Maciulskiene-Visockiene, and Greta Lodiene. 2024. "Blood pH Changes in Dental Pulp of Patients with Pulpitis" Diagnostics 14, no. 11: 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111128

APA StyleHosseinzadehfard, P., Skučaitė, N., Maciulskiene-Visockiene, V., & Lodiene, G. (2024). Blood pH Changes in Dental Pulp of Patients with Pulpitis. Diagnostics, 14(11), 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111128