Development of a Subtraction Processing Technology for Assistance in the Comparative Interpretation of Mammograms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

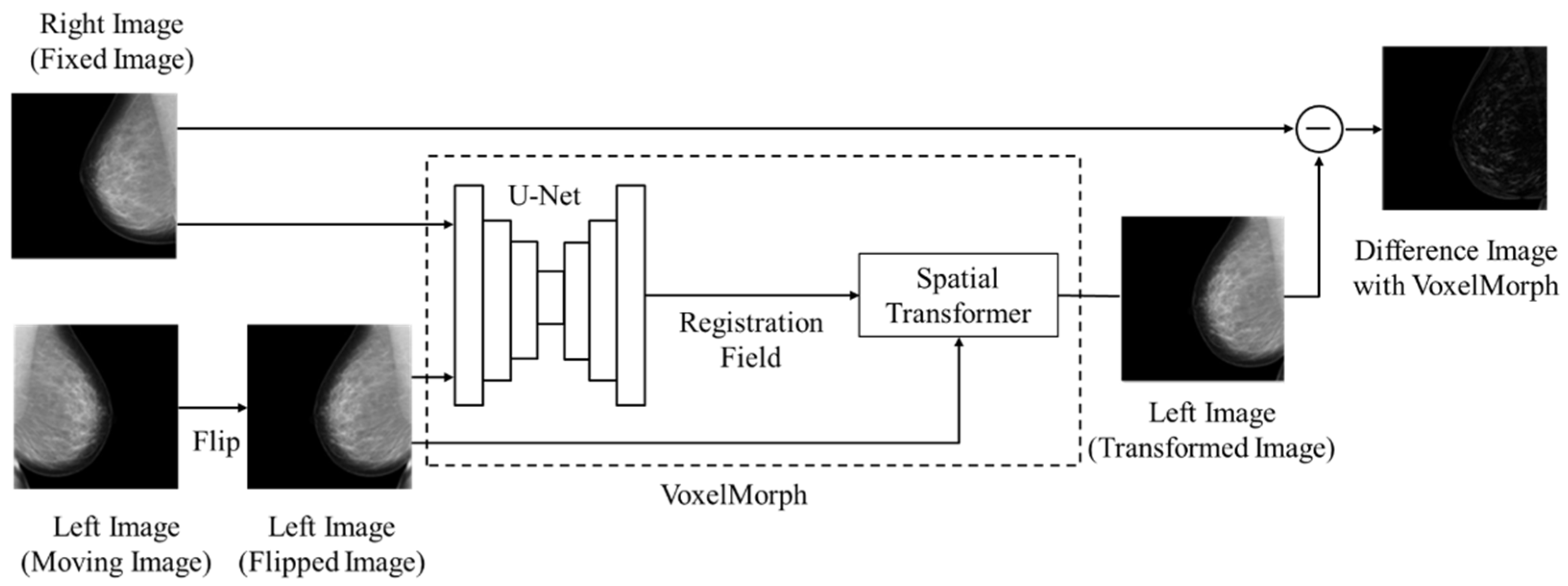

2.2. Registration Method and Subtraction Processing

2.3. Evaluation Method

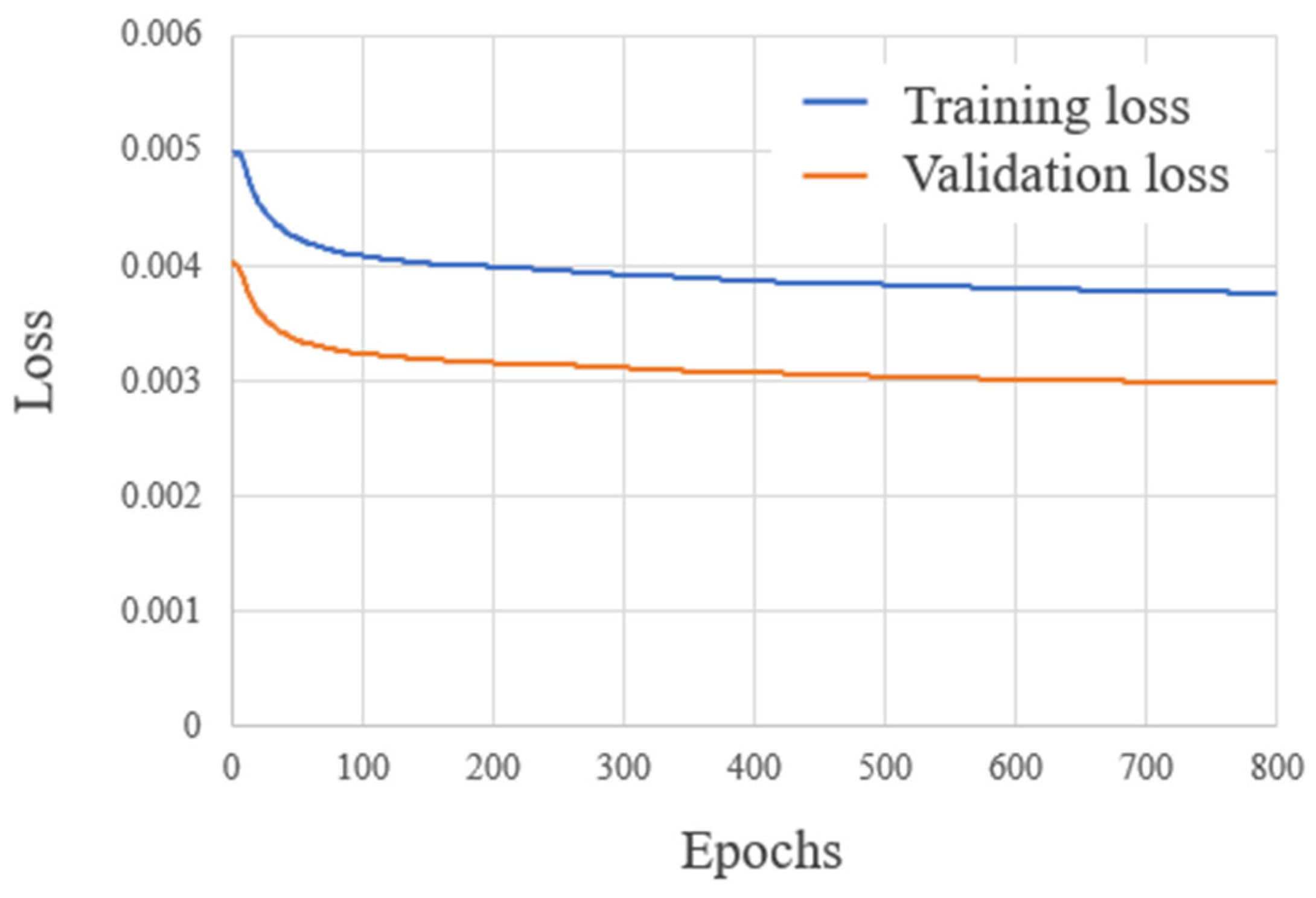

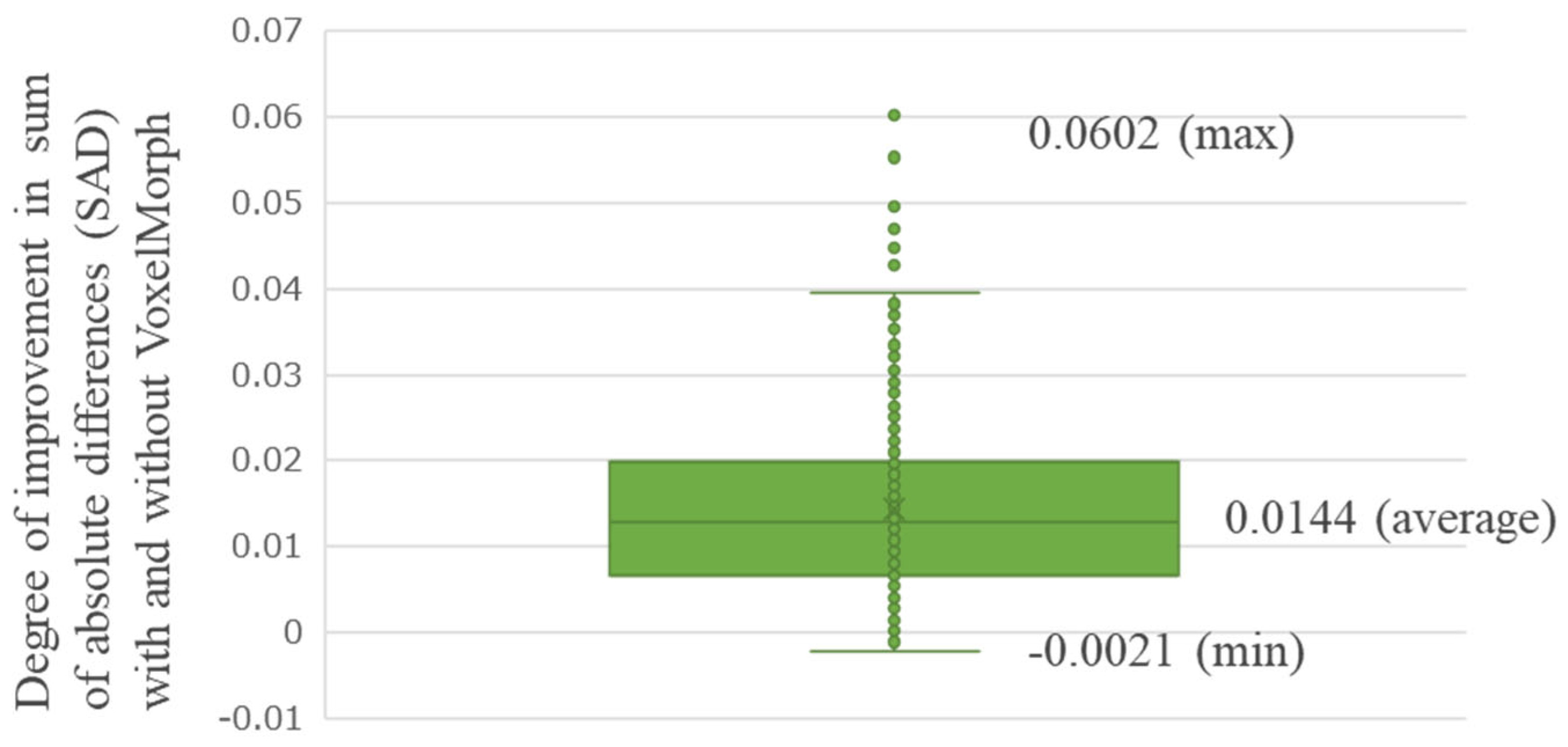

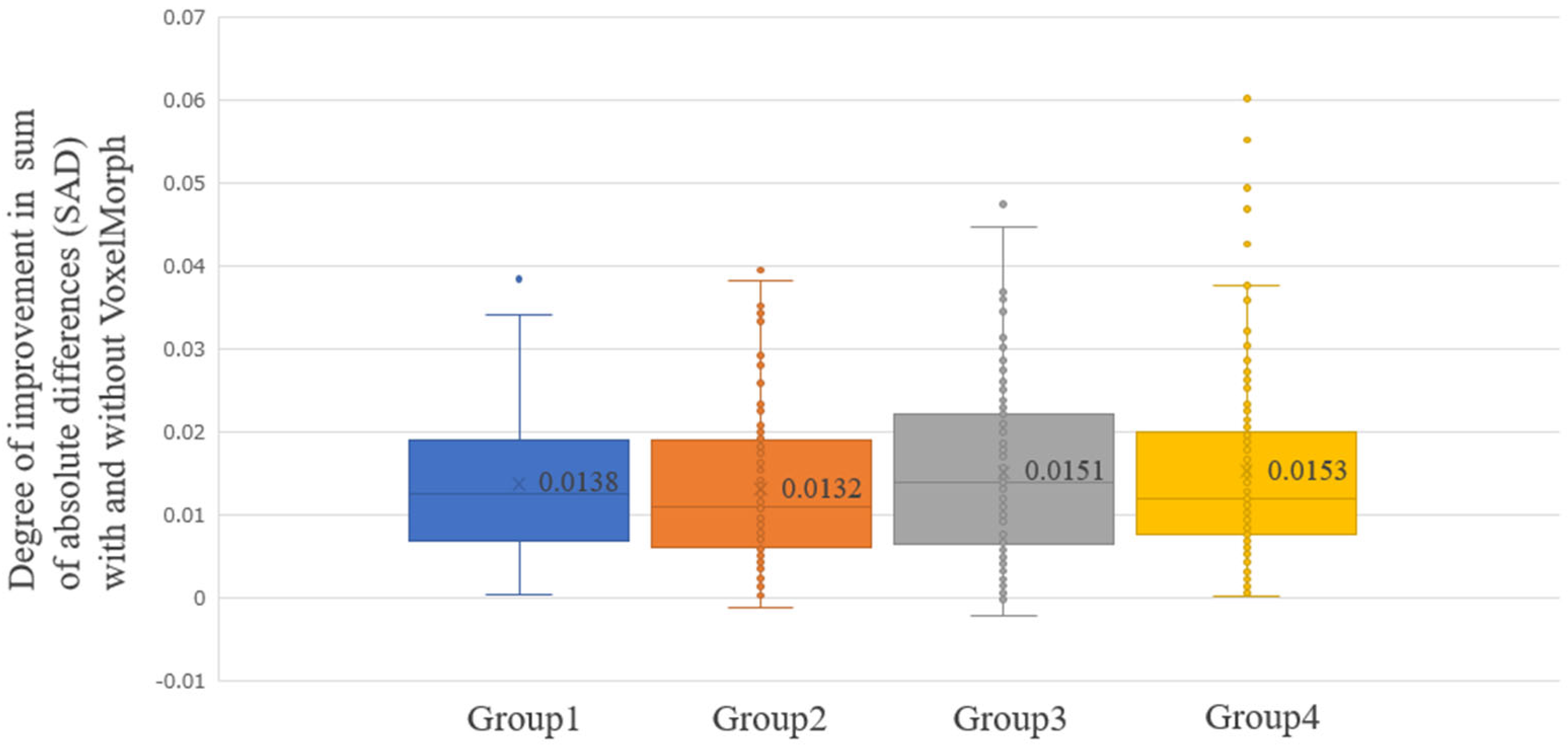

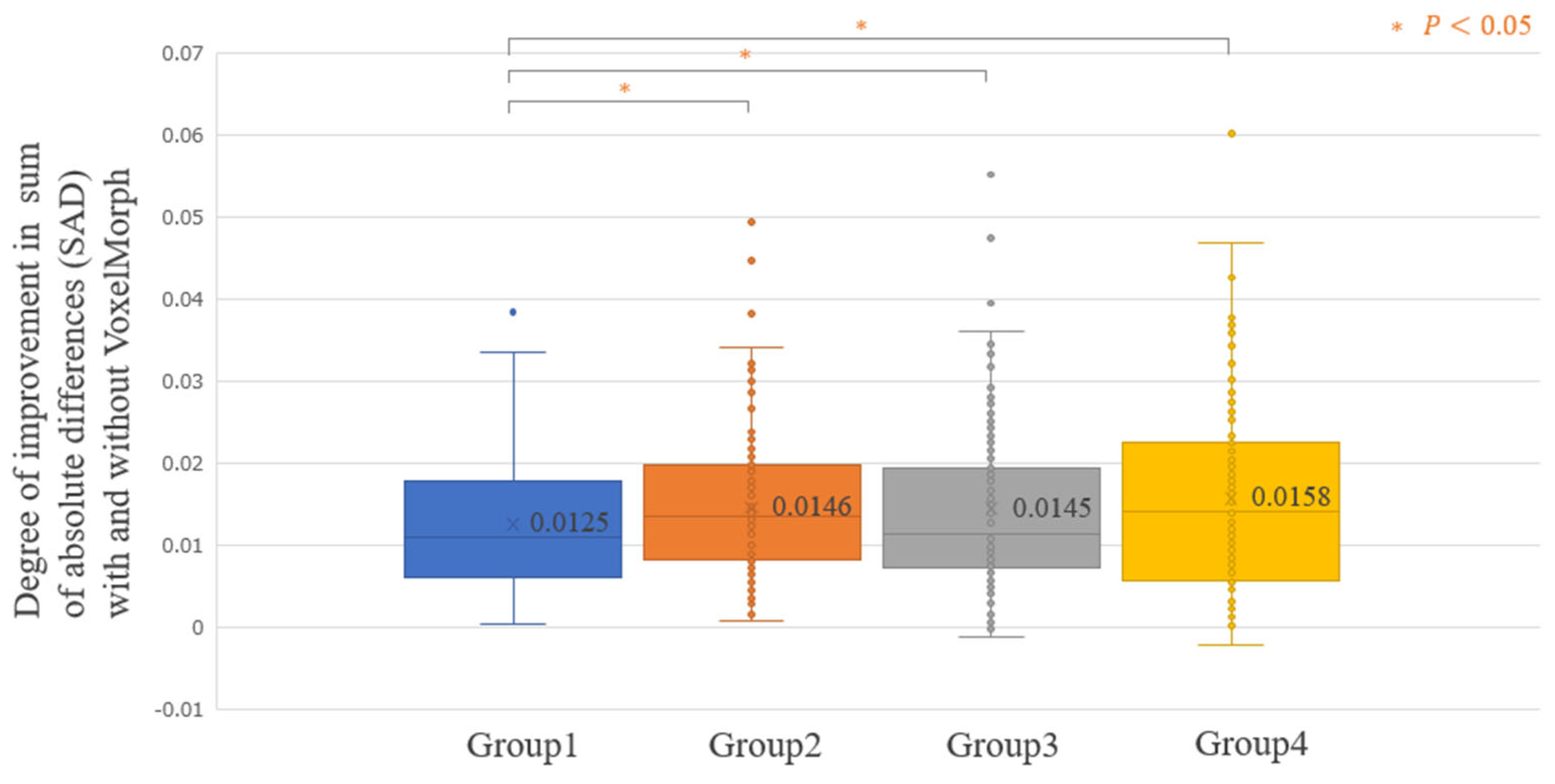

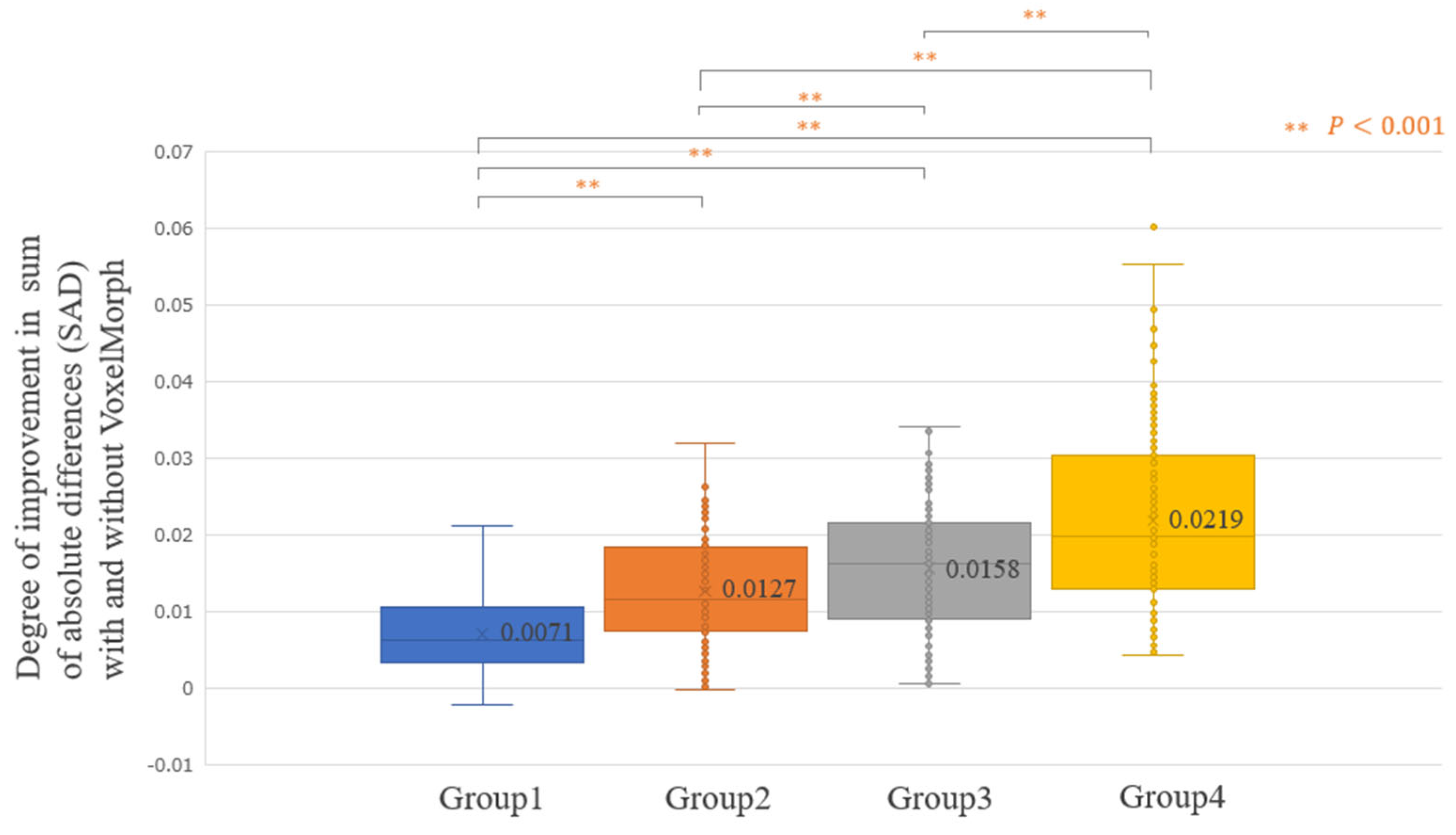

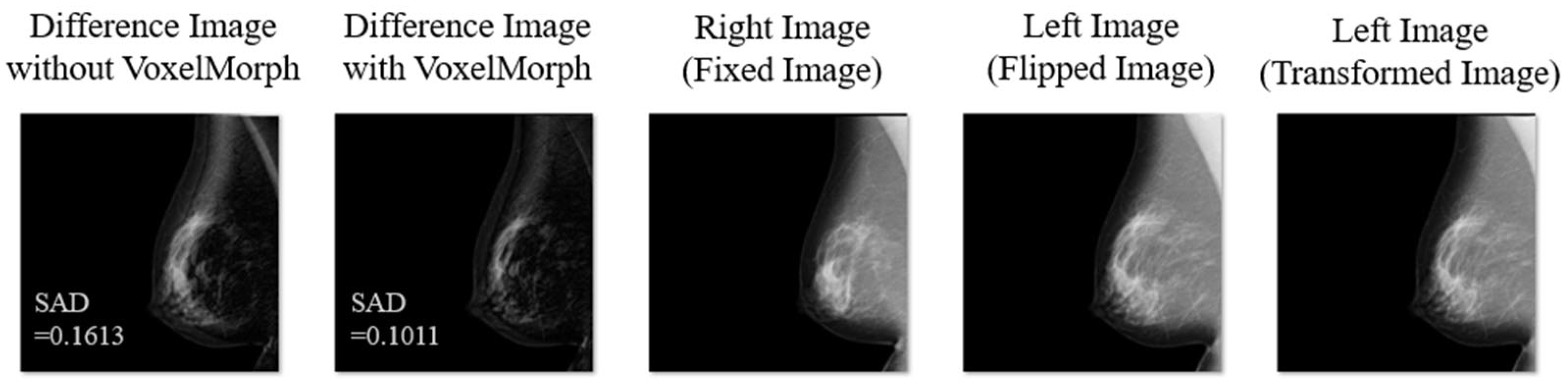

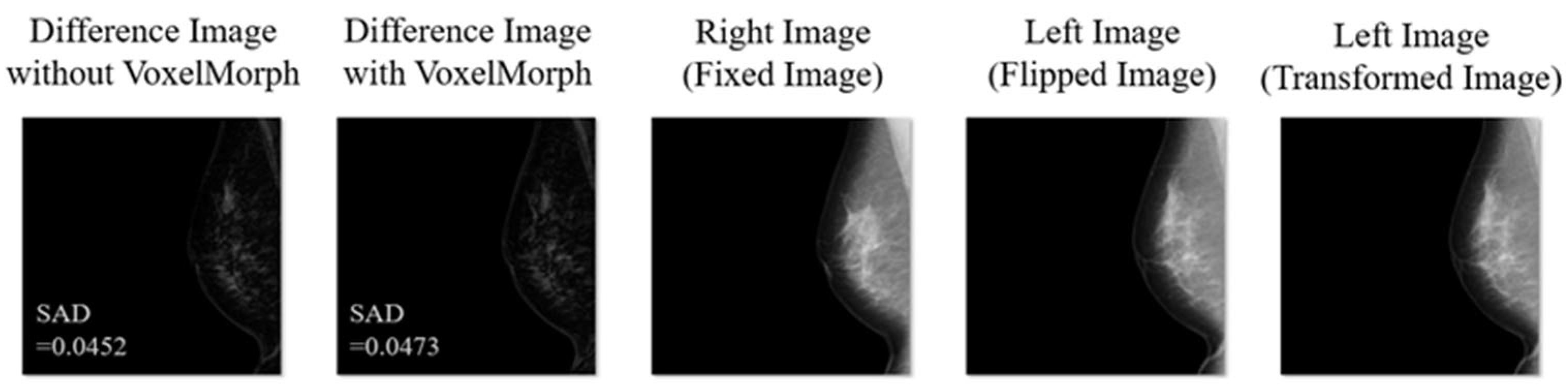

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moss, S.M.; Wale, C.; Smith, R.; Evans, A.; Cuckle, H.; Duffy, S.W. Effect of mammographic screening from age 40 years on breast cancer mortality in the UK Age trial at 17 years’ follow-up: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1123–1132, Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, E427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabár, L.; Dean, P.B.; Chen, T.H.; Yen, A.M.; Chen, S.L.; Fann, J.C.; Chiu, S.Y.; Ku, M.M.; Wu, W.Y.; Hsu, C.Y.; et al. The incidence of fatal breast cancer measures the increased effectiveness of therapy in women participating in mammography screening. Cancer 2019, 125, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Duffy, S.W.; Vulkan, D.; Cuckle, H.; Parmar, D.; Sheikh, S.; Smith, R.A.; Evans, A.; Blyuss, O.; Johns, L.; Ellis, I.O.; et al. Effect of mammographic screening from age 40 years on breast cancer mortality (UK Age trial): Final results of a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Duffy, S.W.; Tabár, L.; Yen, A.M.; Dean, P.B.; Smith, R.A.; Jonsson, H.; Törnberg, S.; Chiu, S.Y.; Chen, S.L.; Jen, G.H.; et al. Beneficial effect of consecutive screening mammography examinations on mortality from breast cancer: A prospective study. Radiology 2021, 299, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Radiology. Available online: https://aicentral.acrdsi.org/ (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- Rodríguez-Ruiz, A.; Krupinski, E.; Mordang, J.J.; Schilling, K.; Heywang-Köbrunner, S.H.; Sechopoulos, I.; Mann, R.M. Detection of breast cancer with mammography: Effect of an artificial intelligence support system. Radiology 2019, 290, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacilè, S.; Lopez, J.; Chone, P.; Bertinotti, T.; Grouin, J.M.; Fillard, P. Improving breast cancer detection accuracy of mammography with the concurrent use of an artificial intelligence tool. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2020, 2, e190208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Ruiz, A.; Lång, K.; Gubern-Merida, A.; Teuwen, J.; Broeders, M.; Gennaro, G.; Clauser, P.; Helbich, T.H.; Chevalier, M.; Mertelmeier, T.; et al. Can we reduce the workload of mammographic screening by automatic identification of normal exams with artificial intelligence? A feasibility study. Eur. Radiol. 2019, 29, 4825–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dembrower, K.; Wåhlin, E.; Liu, Y.; Salim, M.; Smith, K.; Lindholm, P.; Eklund, M.; Strand, F. Effect of artificial intelligence-based triaging of breast cancer screening mammograms on cancer detection and radiologist workload: A retrospective simulation study. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, E468–E474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.E.; Kim, H.H.; Han, B.K.; Kim, K.H.; Han, K.; Nam, H.; Lee, E.H.; Kim, E.K. Changes in cancer detection and false-positive recall in mammography using artificial intelligence: A retrospective, multireader study. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, E138–E148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo, R.C.; Kent, D.; Sen, L.C.; Kapoor, M.; Leung, J.W.T.; Watanabe, A.T. Reduction of false-positive markings on mammograms: A retrospective comparison study using an artificial intelligence-based CAD. J. Digit. Imaging 2019, 32, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, C.; Karssemeijer, N.; Hendriks, J.H.; Holland, R. Use of prior mammograms in the classification of benign and malignant masses. Eur. J. Radiol. 2005, 56, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, T.; Yasuhara, Y.; Kano, A.; Mochizuki, T.; Ikezoe, J. Effect of temporal subtraction technique on the diagnosis of primary lung cancer with chest radiography. Radiat. Med. 2003, 21, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pal, S.; Ikeda, D.M.; Jesinger, R.A.; Mickelsen, L.J.; Chen, C.A.; Larson, D.B. Improving performance of mammographic breast positioning in an academic radiology practice. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2018, 210, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, G.; Zhao, A.; Sabuncu, M.R.; Guttag, J.; Dalca, A.V. Voxelmorph: A learning framework for deformable medical image registration. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2019, 38, 1788–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eijnatten, M.; Rundo, L.; Batenburg, K.J.; Lucka, F.; Beddowes, E.; Caldas, C.; Gallagher, F.A.; Sala, E.; Schönlieb, C.B.; Woitek, R. 3D deformable registration of longitudinal abdominopelvic CT images using unsupervised deep learning. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 208, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Feng, H.; Yang, Y.; Holmes, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, D.; Wong, W.W.; Yu, N.Y.; Sio, T.T.; Schild, S.E.; et al. Deep-learning based fast and accurate 3D CT deformable image registration in lung cancer. Med. Phys. 2023, 50, 6864–6880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, M.; Bi, L.; Fulham, M.; Feng, D.D.; Kim, J. Enhancing medical image registration via appearance adjustment networks. NeuroImage 2022, 259, 119444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Bajaj, H.; Siddiquee, I.H.; Subbarayappa, N.B.; Simon, S.; Shashidhar, S.B.; Speck, O.; Nürnberger, A. MICDIR: Multi-scale inverse-consistent deformable image registration using UNetMSS with self-constructing graph latent. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2023, 108, 102267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 18, pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Jaderberg, M.; Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Spatial transformer networks. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.02025v3. [Google Scholar]

- Kai, C.; Ishizuka, S.; Otsuka, T.; Nara, M.; Kondo, S.; Futamura, H.; Kodama, N.; Kasai, S. Automated estimation of mammary gland content ratio using regression deep convolutional neural network and the effectiveness in clinical practice as explainable artificial intelligence. Cancers 2023, 15, 2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast area (%) | Training | 33.3 ± 10.0 | 22.2 ± 2.9 | 29.0 ± 1.6 | 35.1 ± 2.0 | 47.0 ± 7.1 |

| [12.7–73.1] | [12.7–26.0] | [26.1–31.8] | [31.8–38.8] | [38.9–73.1] | ||

| Validation | 32.3 ± 8.6 | 22.5 ± 2.7 | 29.3 ± 2.1 | 34.4 ± 1.0 | 43.1 ± 7.6 | |

| [14.9–64.2] | [14.9–25.7] | [25.9–32.4] | [32.6–36.2] | [36.2–64.2] | ||

| Test | 34.4 ± 10.7 | 22.8 ± 3.5 | 29.7 ± 1.4 | 36.0 ± 2.4 | 49.2 ± 7.4 | |

| [11.1–79.8] | [11.1–27.1] | [27.2–32.4] | [32.4–40.7] | [40.8–79.8] | ||

| Mammary gland content ratio (%) | Training | 45.0 ± 16.5 | 23.9 ± 6.2 | 38.5 ± 3.2 | 50.7 ± 4.4 | 66.7 ± 5.9 |

| [11.0–85.6] | [11.0–32.6] | [32.7–43.8] | [43.8–58.3] | [58.3–85.6] | ||

| Validation | 45.1 ± 15.1 | 26.5 ± 6.6 | 39.2 ± 3.0 | 49.4 ± 3.6 | 65.3 ± 5.9 | |

| [11.8–81.0] | [11.8–33.8] | [34.0–43.5] | [43.6–56.9] | [57.7–81.0] | ||

| Test | 44.0 ± 16.0 | 24.0 ± 6.2 | 37.6 ± 3.0 | 49.0 ± 4.0 | 65.3 ± 6.9 | |

| [11.5–85.0] | [11.5–32.7] | [32.8–42.5] | [42.5–56.5] | [56.6–85.0] | ||

| Compressed breast thickness (mm) | Training | 44.7 ± 13.4 | 27.9 ± 4.7 | 39.6 ± 2.9 | 49.1 ± 2.9 | 62.2 ± 6.7 |

| [10–86] | [10–34] | [34–44] | [44–54] | [54–86] | ||

| Validation | 44.1 ± 12.4 | 29.0 ± 4.7 | 38.7 ± 2.8 | 48.7 ± 3.0 | 59.9 ± 6.4 | |

| [20–78] | [20–34] | [34–44] | [44–54] | [54–78] | ||

| Test | 45.7 ± 13.6 | 27.9 ± 5.0 | 40.8 ± 3.2 | 51.0 ± 2.8 | 63.0 ± 5.6 | |

| [12–84] | [12–36] | [36–46] | [46–56] | [56–84] | ||

| Difference Image without VoxelMorph (sum of absolute differences: SAD) | Training | 0.070 ± 0.025 | 0.044 ± 0.006 | 0.058 ± 0.004 | 0.073 ± 0.005 | 0.105 ± 0.023 |

| [0.022–0.230] | [0.022–0.052] | [0.052–0.065] | [0.065–0.082] | [0.082–0.230] | ||

| Validation | 0.069 ± 0.023 | 0.044 ± 0.006 | 0.059 ± 0.004 | 0.072 ± 0.006 | 0.101 ± 0.014 | |

| [0.031–0.128] | [0.031–0.051] | [0.052–0.063] | [0.064–0.083] | [0.084–0.128] | ||

| Test | 0.069 ± 0.023 | 0.045 ± 0.007 | 0.059 ± 0.003 | 0.072 ± 0.004 | 0.101 ± 0.020 | |

| [0.021–0.177] | [0.021–0.054] | [0.054–0.065] | [0.065–0.081] | [0.081–0.177] | ||

| Breast Area (%) | Mammary Gland Content Ratio (%) | Compressed Breast Thickness (mm) | Difference Image without VoxelMorph (SAD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without | With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | With | |

| Group 1 | 0.0540 ± 0.013 | 0.0402 ± 0.009 | 0.0791 ± 0.026 | 0.0621 ± 0.021 | 0.0452 ± 0.014 | 0.0381 ± 0.011 | 0.0563 ± 0.007 | 0.0438 ± 0.007 |

| Group 2 | 0.0600 ± 0.014 | 0.0468 ± 0.009 | 0.0724 ± 0.026 | 0.0581 ± 0.020 | 0.0589 ± 0.022 | 0.0463 ± 0.018 | 0.0691 ± 0.003 | 0.0545 ± 0.007 |

| Group 3 | 0.0727 ± 0.018 | 0.0576 ± 0.013 | 0.0658 ± 0.018 | 0.0511 ± 0.015 | 0.0723 ± 0.023 | 0.0566 ± 0.019 | 0.0724 ± 0.004 | 0.0579 ± 0.009 |

| Group 4 | 0.0903 ± 0.026 | 0.0750 ± 0.019 | 0.0596 ± 0.017 | 0.0482 ± 0.015 | 0.1005 ± 0.025 | 0.0786 ± 0.019 | 0.0790 ± 0.020 | 0.0633 ± 0.018 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kai, C.; Kondo, S.; Otsuka, T.; Yoshida, A.; Sato, I.; Futamura, H.; Kodama, N.; Kasai, S. Development of a Subtraction Processing Technology for Assistance in the Comparative Interpretation of Mammograms. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111131

Kai C, Kondo S, Otsuka T, Yoshida A, Sato I, Futamura H, Kodama N, Kasai S. Development of a Subtraction Processing Technology for Assistance in the Comparative Interpretation of Mammograms. Diagnostics. 2024; 14(11):1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111131

Chicago/Turabian StyleKai, Chiharu, Satoshi Kondo, Tsunehiro Otsuka, Akifumi Yoshida, Ikumi Sato, Hitoshi Futamura, Naoki Kodama, and Satoshi Kasai. 2024. "Development of a Subtraction Processing Technology for Assistance in the Comparative Interpretation of Mammograms" Diagnostics 14, no. 11: 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111131

APA StyleKai, C., Kondo, S., Otsuka, T., Yoshida, A., Sato, I., Futamura, H., Kodama, N., & Kasai, S. (2024). Development of a Subtraction Processing Technology for Assistance in the Comparative Interpretation of Mammograms. Diagnostics, 14(11), 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111131