Right Bundle Branch Block Predicts Appropriate Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Therapies in Patients with Non-Ischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy and a Prophylactic Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

Patient Population and Study Design

3. Study Variables, Follow-Up, and Outcomes

Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population

4.2. Follow-Up and Outcomes

4.3. Predictors of Appropriate ICD Therapies

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Primary Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death in NICM

5.3. Identifying High-Risk Patients for Sudden Cardiac Death

6. Complications Related to ICD Implantation

Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shen, L.; Jhund, P.; Petrie, M.B.; Claggett, B.L.; Barlera, S.; Cleland, J.G.; Dargie, H.J.; Granger, C.B.; Kjekshus, J.; Køber, L.; et al. Declining Risk of Sudden Death in Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrakis, S.; Asad, Z.; Reynolds, D. Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators for Primary Prevention of Mortality in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 2017, 28, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; Falk, V.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.-P.; Jankowska, E.A.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2129–2200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kober, L.; Thune, J.J.; Nielsen, J.C.; Haarbo, J.; Videbæk, L.; Korup, E.; Jensen, G.; Hildebrandt, P.; Steffensen, F.H.; Bruun, N.E.; et al. Defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic systolic heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japp, A.G.; Gulati, A.; Cook, S.A.; Cowie, M.R.; Prasad, S.K. The Diagnosis and Evaluation of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 2996–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baddour, L.M.; Epstein, A.E.; Erickson, C.; Knight, B.P.; Levison, M.E.; Lockhart, P.B.; Masoudi, F.A.; Okum, E.J.; Wilson, W.R.; Beerman, L.B.; et al. Update on Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Device Infections and their management. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010, 121, 458–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, G.; Lancellotti, P.; Antunes, M.; Bongiorni, M.G.; Casalta, J.-P.; Del Zotti, F.; Dulgheru, R.; El Khoury, G.; Erba, P.A.; Iung, B.; et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 3075–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bänsch, D.; Antz, M.; Bozcor, S.; Volkmer, M.; Tebbenjohanns, J.; Seidl, K.; Block, M.; Gietzen, F.; Berger, J.; Kuck, K.H. Primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: The Cardiomyopathy Trial (CAT). Circulation 2002, 105, 1453–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strickberger, S.A.; Hummel, J.D.; Bartlett, T.G.; Frumin, H.I.; Schuger, C.D.; Beau, S.L.; Bitar, C.; Morady, F.; AMIOVIRT Investigators. Amiodarone versus implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: Randomized trial in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy and asymptomatic nonsustained ventricular tachycardia-AMIOVIRT. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41, 1707–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadish, A.; Dyer, A.; Daubert, J.P.; Quigg, R.; Estes, N.M.; Anderson, K.P.; Calkins, H.; Hoch, D.; Goldberger, J.; Shalaby, A.; et al. Prophylactic Defibrillator Implantation in Patients with Nonischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2151–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardy, G.H.; Lee, K.L.; Mark, D.B.; Poole, J.E.; Packer, D.L.; Boineau, R.; Domanski, M.; Troutman, C.; Anderson, J.; Johnson, G.; et al. Amiodarone or an Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator for Congestive Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankovic, V.; Karha, J.; Passman, R.; Kadish, A.; Goldberger, J. Predictor of appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2002, 89, 1072–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.; Sarak, B.; Kaplan, A.J.; Oosthuizen, R.; Beardsall, M.; Wulffhart, Z.; Higenbottam, J.; Khaykin, Y. Predictors of appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) therapy in primary prevention patients with ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2010, 33, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, L.; Jiang, R.; Fang, W.; Yan, C.; Tang, Y.; Hua, W.; Fu, M.; Li, X.; Luo, R. Prognostic impact of right bundle branch block in hospitalized patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: A single-center cohort study. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Luo, R.; Fang, W.; Xu, X.; Niu, G.; Xu, Y.; Fu, M.; Hua, W.; Wu, X. Effects of ventricular conduction block patterns on mortality in hospitalized patients with dilated cardiomyopathy: A single-center cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2016, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elming, M.; Hammer-Hanser, S.; Voges, I.; Nyktari, E.; Raja, A.A.; Svendsen, J.H.; Pehrson, S.; Signorovitch, J.; Køber, L.V.; Prasad, S.K.; et al. Right ventricular dysfunction and the Effect of Defibrillator Implantation in Patients with Nonischemic Systolic Heart Failure. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2019, 12, e007022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Heijden, A.C.; Thijssen, J.; Borleffs, C.J.W.; van Rees, J.B.; Höke, U.; van der Velde, E.T.; van Erven, L.; Schalij, M.J. Gender-specific differences in clinical outcome of primary prevention implantable cardioverter defibrillator recipients. Heart 2013, 99, 1244–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haigney, M.C.; Zareba, W.; Nasir, J.M.; McNitt, S.; McAdams, D.; Gentlesk, P.J.; Goldstein, R.E.; Moss, A.J. Gender differences and risk of ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2009, 6, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elming, M.B.; Nielsen, J.; Haarbo, J.; Videbæk, L.; Korup, E.; Signorovitch, J.; Olesen, L.L.; Hildebrandt, P.; Steffensen, F.H.; Bruun, N.E.; et al. Age and Outcomes of Primary Prevention Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators in Patients with Nonischemic Systolic Heart Failure. Circulation 2017, 136, 1772–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (n = 224) | No Therapy (n = 163) | Appropriate Therapies (n = 61) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, IQR) | 62.7 (55.1–69.0) | 63.7 (57.0–69.8) | 58.7 (53.0–64.8) | 0.0204 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 165 (73.7%) | 112 (68.7%) | 53 (86.9%) | 0.006 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 121 (54.3%) | 88 (54.3%) | 33 (54.1%) | 0.976 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 64 (28.8%) | 50 (30.9%) | 14 (23.3%) | 0.271 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 88 (39.5%) | 62 (38.3%) | 26 (42.6%) | 0.553 |

| NYHA class, n (%) | 0.7961 | |||

| I | 20 (9.1%) | 17 (10.7%) | 3 (4.9%) | |

| II | 117 (53.2%) | 81 (50.9%) | 36 (59.0%) | |

| III | 78 (35.5%) | 57 (35.9%) | 21 (34.4%) | |

| IV | 5 (2.3%) | 4 (2.5%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL, median (IQR) | 1421.5 (503–4586) | 1396 (501–4755) | 1465 (515–4586) | 0.9526 |

| Coronariography, n (%) | 210 (94.2%) | 154 (95.1%) | 56 (91.8%) | 0.355 |

| ECG—rhythm | 0.9131 | |||

| Sinus rhythm, n (%) | 143 (63.8%) | 108 (66.7%) | 35 (59,3%) | |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter, n (%) | 64 (28.6%) | 41 (25.3%) | 23 (39.0%) | |

| Ventricular pacing, n (%) | 14 (6.3%) | 13 (8.0%) | 1 (1.7%) | |

| ECG—conduction disturbance | ||||

| LBBB, n (%) | 93 (41.5%) | 77 (47.2%) | 16 (26.2%) | 0.005 |

| RBBB, n (%) | 16 (7.1%) | 7 (4.3%) | 9 (14.8%) | 0.007 |

| IVCD, n (%) | 23 (10.3%) | 17 (10.4%) | 6 (9.8%) | 0.896 |

| None, n (%) | 62 (27.7%) | 40 (24.5%) | 22 (36.1%) | 0.086 |

| Echocardiogram at baseline LVEF (%) (median, IQR) LVEDV, ml/m2 (median, IQR) LVESV, ml/m2 (median, IQR) LA diameter, mm (mean ± SD) Significant mitral regurgitation (moderate or severe), n (%) | 28 (22–31.9) 90.9 (72.6–113.5) 65.2 (49.5–84.7) 45.7 ± 8.7 81 (36.2%) | 29 (24.2–32.0) 86.0 (71.3–110) 60.9 (47.4–80.5) 44.8 ± 8.5 61 (37.4%) | 26 (20–30) 100 (90–116.8) 72.2 (58.9–87.4) 48.2 ± 8.8 20 (32.8%) | 0.0770 0.0106 0.0467 0.0480 0.520 |

| Type of cardiomyopathy Idiopathic, n (%) Alcoholic, n (%) Others Familial, n (%) Valvular, n (%) Hypertensive, n (%) | 133 (60.5%) 32 (14.6%) 29 (13.0%) 14 (6.4%) 9 (4.1%) 3 (1.4%) | 98 (61.3%) 21 (13.1%) 22 (13.6%) 10 (6.3%) 6 (3.8%) 3 (1.9%) | 35 (58.3%) 11 (18.3%) 7 (11.6%) 4 (6.7%) 3 (5.0%) 0 (0%) | 0.9199 |

| Heart failure medications ACE inhibitors, n (%) Betablockers, n (%) Mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonist, n (%) ARNI, n (%) Amiodarone, n (%) | 196 (88.3%) 207 (92.8%) 160 (71.4%) 17 (7.7%) 24 (10.8%) | 143 (88.8%) 153 (94.4%) 119 (73.5%) 15 (9.3%) 18 (11.4%) | 53 (86.9%) 54 (88.5%) 41 (67.2%) 2 (3.3%) 6 (9.2%) | 0.689 0.127 0.356 0.131 0.636 |

| Type of implanted device Single-chamber ICD, n (%) Dual-chamber ICD, n (%) ICD-CRT n (%) | 98 (43.8%) 10 (4.5%) 116 (51.8%) | 70 (42.9%) 7 (4.3%) 86 (52.8%) | 28 (45.9%) 3 (4.9%) 30 (49.2%) | 0.655 0.924 0.657 |

| Outcomes Death, n (%) Heart transplant, n (%) Death or heart transplant, n (%) | 43 (19.2%) 9 (4.0%) 52 (23.2%) | 27 (16.6%) 3 (1.8%) 30 (18.4%) | 16 (26.2%) 6 (9.8%) 22 (36.1%) | 0.102 0.007 0.005 |

| Patient | Symptoms | Fever | Blood Cultures | ICD Cultures | Vegetation in TOE | Explant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Phlebitis | Yes | Staphylococcus lugdunensis | - | Yes | No |

| 2 | Urinary sepsis | Yes | Negative | Negative | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | Erythema | No | Staphylococcus hominis | S. epidermidis Acinetobacter | No | Yes |

| 4 | Missing data | No | Negative | S. epidermidis S. hominis-hominis | No | Yes |

| 5 | Wound dehiscence | No | Negative | S. epidermidis | No | Yes |

| 6 | Erythema and warmth | No | Negative | S. epidermidis | No | Yes |

| 7 | Wound dehiscence and purulent drainage | No | Negative | S. aureus S. epidermidis | No | Yes |

| 8 | Erythema, warmth and fluctuance | Yes | Staph coagulase negative | Negative | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | Erythema and fluctuance | No | Negative | S. aureus | - | Yes |

| 10 | Wound dehiscence, edema, and warmth | No | Not performed | S. aureus | - | Yes |

| 11 | Wound dehiscence and erythema | No | Negative | S. epidermidis | - | Yes |

| Adjusted Hazards Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.99 | 0.97–1.02 | 0.645 |

| Male sex | 2.04 | 0.84–5 | 0.115 |

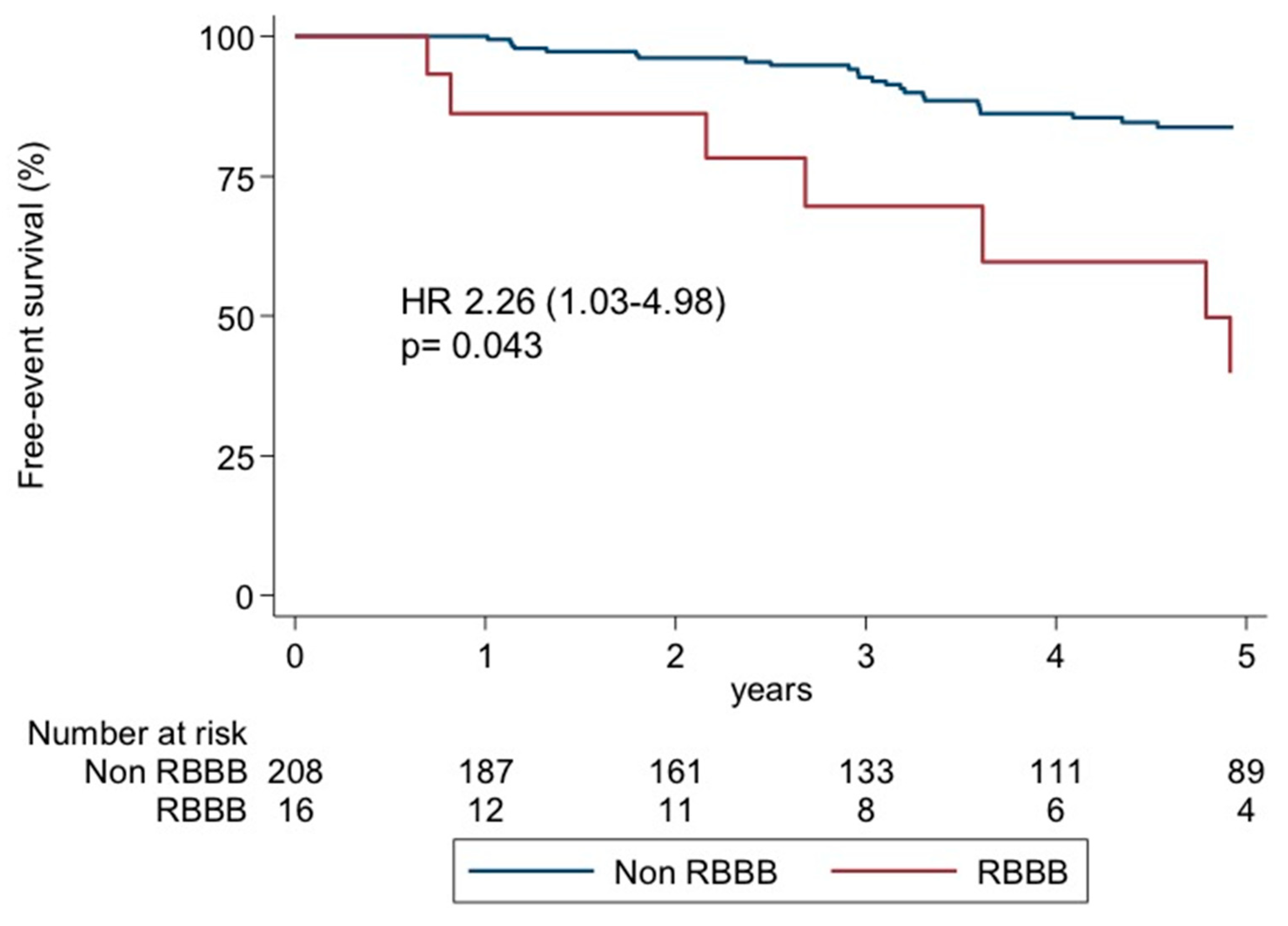

| RBBB | 2.26 | 1.03–4.98 | 0.043 |

| LBBB | 0.62 | 0.33–1.16 | 0.135 |

| LVEF | 0.99 | 0.96–1.03 | 0.626 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Blanco Bravo, M.; Alonso Salinas, G.L.; Parra Esteban, C.; Toquero Ramos, J.; Amores Luque, M.; Zamorano Gómez, J.L.; García-Izquierdo, E.; Álvarez-García, J.; Fernández Lozano, I.; Castro Urda, V. Right Bundle Branch Block Predicts Appropriate Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Therapies in Patients with Non-Ischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy and a Prophylactic Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111173

Jiménez-Blanco Bravo M, Alonso Salinas GL, Parra Esteban C, Toquero Ramos J, Amores Luque M, Zamorano Gómez JL, García-Izquierdo E, Álvarez-García J, Fernández Lozano I, Castro Urda V. Right Bundle Branch Block Predicts Appropriate Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Therapies in Patients with Non-Ischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy and a Prophylactic Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator. Diagnostics. 2024; 14(11):1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111173

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Blanco Bravo, Marta, Gonzalo Luis Alonso Salinas, Carolina Parra Esteban, Jorge Toquero Ramos, Miguel Amores Luque, Jose Luis Zamorano Gómez, Eusebio García-Izquierdo, Jesús Álvarez-García, Ignacio Fernández Lozano, and Víctor Castro Urda. 2024. "Right Bundle Branch Block Predicts Appropriate Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Therapies in Patients with Non-Ischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy and a Prophylactic Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator" Diagnostics 14, no. 11: 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111173

APA StyleJiménez-Blanco Bravo, M., Alonso Salinas, G. L., Parra Esteban, C., Toquero Ramos, J., Amores Luque, M., Zamorano Gómez, J. L., García-Izquierdo, E., Álvarez-García, J., Fernández Lozano, I., & Castro Urda, V. (2024). Right Bundle Branch Block Predicts Appropriate Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Therapies in Patients with Non-Ischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy and a Prophylactic Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator. Diagnostics, 14(11), 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111173