1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic affects much of the population globally in many ways. There is an exponential growth in literature on the COVID pandemic to document its disruptions, impacts, and responses around the world, which focused on an endless list of possible aspects and features. To put this into perspective, a search performed on the Google Scholar search engine using ‘COVID’ as the keyword had returned a total of 5.26 million results at the time of writing (October 2022) compared to 1.77 million in Oo and Lim’s [

1] search performed back in November 2020. Even when a more focused search using ‘COVID’ and ‘impact’ as the keywords yielded a total of 3.49 million results, signifying the wide-ranging impacts of the pandemic on essentially everything such as human milk bank, fresh produce supply, health and diseases, education, transportation, national economy, etc. One of the focuses of these vast number of publications is on the impacts of the pandemic on different industry sectors in different countries. Unsurprisingly, there is a sizeable collection of studies on the impacts of pandemic on the construction industry globally, which explained the uncovering of systematic review articles despite the novelty of this topic area (e.g., [

2,

3,

4]). The sudden transition to a new unplanned work setting, i.e., switching to working from home (WFH) was identified in the systematic review studies as one of the key impacts on the industry, affecting construction workforce who used to working in the company workplace. Indeed, it is estimated that more than four out of five people (81%) in the global workforce of 3.3 billion were affected by full or partial workplace closures [

5].

There is wealth of literature on remote working (i.e., working away from the conventional workplace, often from home, which is also known as telework or telecommuting) over the last several decades on a broad scope of research interests, for e.g., [

6,

7]. However, a bright spotlight was thrown on the WFH practices in March 2020 because of its sudden growth of prominence due to the pandemic lockdowns in most countries. Researchers have explored WFH setting from different perspectives including its benefits and shortcomings, its impacts on work productivity and employees’ well-being, and the challenges, opportunities and implications of WFH during and post the pandemic (e.g., [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]). Raišienė et al. [

14] asserted that a body of knowledge on WFH practices induced by the pandemic is essential in addressing human resource management challenges given the fact that knowledge on telework in the literature was accumulated before the pandemic, and that the experience of those who was new to WFH practices due to the pandemic is peculiar. The present study was carried out because of the dearth of literature on how construction workforce perceived WFH arrangement induced by the pandemic lockdowns. Hitherto, it is evidenced in the systematic review articles that most articles on the impacts of the pandemic have had focused on construction site operations, especially on the health and safety of construction workers on-site. There is only a handful of empirical studies that shed light on WFH practices among construction workforce (e.g., [

1,

15,

16]). The study aims to explore individuals’ perceptions of WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic from the construction workforce perspective. Focusing on consultants in the Australian construction industry, it specifically examines: (i) their perceptions of the impacts of WFH challenges on work activities and performance, and (ii) their self-reported work productivity, overall WFH satisfaction and future preference for WFH post-pandemic. In Australia, since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a series of national, state, and territory-based lockdowns between March 2020 and December 2021 have been part of the Australian response to managing the health crisis [

17]. Construction businesses had been significantly impacted by the government lockdown measures in response to COVID-19 pandemic including changes to the work arrangements—reduced hours worked, changed to WFH and placed staff on paid leave [

1]. The findings from this exploratory study provide an insight that is crucial to provide a foundation in future research efforts on WFH practices in the industry. This insight brings with it some important implications for employing organizations in addressing human resource management challenges, in particular, the development of WFH and/or hybrid working protocols in order to maximize the potential benefits of WFH practices post-pandemic.

2. The Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Construction Industry

For the construction industry, there is a significant growth of the body of knowledge on the impacts and responses to COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the novelty of this topic area, noting that the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as pandemic on 11 March 2020 [

18], the present study had located as many as four systematic review articles at the time of writing (October 2022). While this seemingly suggests a spike of COVID-related literature in construction which would continue to grow, these systematic review studies have nevertheless provided a good overview of current research focuses on this topic area. Firstly, a systematic review by Sierra [

4] has classified the challenges faced by contractors due to the pandemic into seven major themes: health and safety, economics, procurement, manpower, supply chain, subcontractors, and uncertainty about the evolution of COVID, markets and government decisions. It is noted that the majority of the literature sources included in his review were web articles, specialized e-magazines, videos and webinars available between January and June 2020 (i.e., at the beginning of the pandemic), and these sources focus mainly on the health and safety on-site, economics and construction procurement aspects. Next, Pamidimukkala and Kermanshachi’s [

3] systematic review aimed at identifying the challenges faced by construction workforce and the strategies they adopted to address these challenges during the pandemic. From their collection of 81 articles, a total of seventeen challenges identified in their review were classified into five factor groups: organizational, economic, psychological, individual and moderating factors. Similarly, their review presented a list of identified strategies on safeguarding workforce, project performance and project community.

The review by Ayat et al. [

19], based on a collection of 53 peer-reviewed articles, reveals that most of these articles have focused on the challenges, impacts, and health and safety issues at construction sites in relation to the pandemic. Their review has also highlighted the positive and negative impacts, the new opportunities and safety barriers in construction sector resulting from the pandemic. Lastly, a more recent systematic review on the impacts of the pandemic by Li et al. [

2], on the other hand, have grouped the eleven key impacts identified from a collection of 83 journal articles under the four stages of a project life cycle, namely planning, design, construction, and operation and maintenance. The identified key impacts cover many different aspects ranging from risk management and environmental quality control in the planning and design stages to performance, contracts, standards, workers and operational barriers during the construction, operation and maintenance stages. It is worth nothing that their collection of 83 articles is originated from 35 countries, with studies from China (

n = 26) topped the list, followed by studies from the United States (

n = 11) and the United Kingdom (

n = 8). All in all, while the authors have provided classifications of themes and/or findings from their systematic review, there was no attempt on the part of quantification to shed greater light on the prevalence and severity of the identified impacts, challenges and strategies. This could possibly be explained by three reasons. First, the impacts of the pandemic are wide ranging and most of the studies on this novel topic area are of exploratory nature. Second, there is a lack of empirical investigation of quantitative nature in the literature since the selection of measurement items would be a difficult task given the immaturity of research in this area. Thirdly, these exploratory studies have employed varying research methods [

19], which would not facilitate a meta-analysis or the use of a statistical technique for an orderly summarization of studies so that knowledge can be extracted from the myriad individual studies.

In terms of research gaps, it is evidenced in these systematic review studies that most articles on the impacts of the pandemic have had focused on construction site operations, especially on the health and safety of construction workers on-site. There is a sizeable collection of health and safety studies from different countries, for example, in the US [

20,

21,

22], in the UK [

23,

24], in Singapore [

25] and in South Africa [

26]. Very little has been reported on the well-being of office-based construction workforce who had to adapt to an unfamiliar way of working, i.e., WFH due to the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns. Indeed, the government-imposed workplace lockdowns (i.e., including restrictions on non-essential travel, closing schools and non-essential businesses) in most countries had provoked a sudden transition to a new unplanned WFH setting for a large population of employees for the first time. Bonacini et al. [

10] opined that WFH is the only option to both continue working and minimize the risk of virus exposure due to the pandemic lockdowns.

3. Construction Workforce and Working from Home (WFH)

With no exception, the sudden transition to a new unplanned WFH setting is one of the key impacts induced by the pandemic for office-based construction workforce [

3]. Indeed, literature on remote working (also known as telework or telecommuting) over the last several decades has covered a broad scope of research interests, for example, Martin and MacDonnell’s [

6] meta-analysis of empirical research on perceptions of telework and organizational outcomes, Allen et al.’s [

7] critical review that aimed to shed light on the debate in the literature on telecommuting’s benefits and drawbacks, Gajendran and Harrison’s [

27] meta-analysis on psychological mediators and individual consequences of telework, and Bailey and Kurland’s [

28] critical review on wh-question in telework. While these studies do find evidence that telework is beneficial both at organization and individual levels, its prevalence rates vary considerably as reported in the literature. On the question why individuals telework, Bailey and Kurland [

28] found that, on one hand, work-related factors are the most predictive of individuals’ choice of telework. On the other hand, managers perceived little need and concerned about costs and control over telework, and thus unwilling to create remote working programs. However, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, remote working or WFH possibility has been transformed from a choice to an obligation, requiring noteworthy adjustments in working arrangements of many employees around the globe. Additionally, challenges in employment are inevitable with statistics on job losses and reductions in work hours in labour markets in different countries, for example, in Australia [

29,

30,

31], in the UK [

32,

33] and in Canada [

34]. It has also been reported that women suffer more than men in their employment and well-being, especially working mothers (e.g., [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]).

For construction workforce, there is a lack of statistics on the prevalence of regular and planned remote work (or WFH) as a flexible work option. However, it could be expected that the rate would have been notably low given the industry’s culture of presenteeism and long work hours [

36,

37,

38,

39]. In a US-based study, it is estimated that the teleworkable ratio (i.e., a measure of the extent of work that can be performed remotely) for construction occupations is less than 25%, similar to those in other industries such as agriculture, manufacturing and retail trades [

40]. Thus, for the majority of construction workforce, the sudden shift to WFH setting would bring challenges in employment since WFH during a pandemic is dissimilar to that of regular remote working [

14,

41]. Through a gender lens, Oo and Lim [

1] explored the changes in job situations of women workforce in the Australian construction industry and their perceptions of career aspects around six months into the pandemic. They reported on the profound changes to work location and working hours among their respondents including WFH and worked more hours than usual. However, and fortunately, their respondents’ perceptions of the negative impacts of the pandemic on their capacity to engage in paid work activities due to caring responsibilities, pay or earnings, job security, and career progression and advancement were modest. Oo et al. [

15] found that the top ranked challenges associated with changes in work location and working hours induced by the pandemic among their female respondents in Australia are: (i) overworked; (ii) working space; (iii) social interactions; (iv) collaboration; and (v) parenting. Their respondents had whined about increased caring and domestic responsibilities during the pandemic and adopted multi-level and interdependent strategies to address the challenges including: (i) increased visual communication; (ii) dedicated workspace; (iii) self-scheduling; (iv) flexible working arrangements; and (v) breaking out work time and personal time.

In another Australia-based study, Pirzadeh and Lingard [

16] examined the impact of remote working on the mental health of construction workforce working on site and WFH. Their results show that there is no statistically significant difference between their two groups of respondents for mental well-being, physical activity, sleep, diet, and work–life satisfaction. While some of their respondents indicated a preference for WFH, their regression analyses showed that increased work hours, feeling pressured for time, and work interference with social life have significant negative impacts on the respondents’ mental well-being, which was moderated by work–life satisfaction. With a group of consultants in the Malaysia construction industry, Suratkon and Azlan’s [

42] survey findings revealed the practicability of WFH arrangement despite of some key challenges faced by their respondents during WFH periods, which were related to social connectivity, emotional support and sense of belonging, mental and physical health, and fear of job security. Remote working was indeed commended by respondents from five continents (excluding South America) who responded to an online open-ended structured questionnaire in Ogunnusi et al. [

43], in which WFH was claimed to provide opportunities to improve on virtual alternatives, and to appreciate the new work mode and flexibility that were thought could not be achieved prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. These handful empirical studies on WFH experiences of construction workforce highlight a dearth of research on construction workforce perceptions of WFH arrangement induced by the pandemic lockdowns, i.e., an essential body of knowledge to realize the full potential benefits of WFH or remote working in the industry.

4. Research Method

A survey design was adopted in this exploratory study in achieving the research objectives. It enables an efficient and timely data collection process to examine the specific aspects of research interest of a given population. The targeted population is construction workforce working for construction consultancy firms in the Australian construction industry, who are at least 18 years old and experienced WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the selection and recruitment of the prospective survey respondents, given the fact the public sector is the major client of the construction industry, the authors had approached the public works divisions of the states of New South Wales (NSW), Victoria and Queensland in attempt to secure their permission for the use of their registers of prequalified consultants for construction procurement. Fortunately, the NSW government public works advisory had kindly granted permission for the use of their register of prequalified consultants in construction procurement. An online survey link using the Qualtrics Survey platform was distributed via emails to all consultancy firms on the register. This sampling approach was considered necessary because of the anticipated low response rate, especially since the study has been classified in the human research ethics approval process as ‘more than low risk’ research that leads (or has the potential) to harms where a person may experience some level of self-doubt and distress. The data collection was carried out in the beginning of 2022 where the prospective survey respondents had experienced WFH during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown periods in Australia between 2020 and 2021.

In the development of the survey questionnaire, the survey respondents were first asked about their demographic profile including the average number of hours spent on unpaid domestic work for household in a typical week during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown periods. Next, they were asked to indicate the impacts of a list of 22 challenges associated with WFH on their work activities and performance. These 22 measurement items were adapted from relevant literature (e.g., [

3,

14,

41])). Recognizing that the challenges associated with WFH would have impacted individual respondents to different degrees in either positive or negative way, the measurement items were thus written in a neutral way, for example, working hours, home office environment, and support from work supervisor. The respective scale is a five-point Likert scale of very negatively (−2), negatively (−1), neutral (0), positively (+1), very positively (+2) and a ‘n/a’ option since some challenges would not be appliable from individual perspectives. The scale of their self-reported work productivity, on the other hand, was adopted from Parry et al. [

44], which was based on work done per hour when WFH during the pandemic compared to normal workplace before the pandemic, using a five-point Likert scale (1 = I get much less done and 5 = I get much more done). The last section of the questionnaire required the respondents to indicate their overall satisfaction with WFH arrangement and future preference for WFH post-pandemic based on their WFH experience induced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

For the data analysis, a One-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was first performed to test on the normality of dataset of quantitative nature. The test results show that the observed variables failed the normality assumption (i.e., the respective p-values are less than 0.05, range between 0 and 0.003), and thus non-parametric statistical tests were used for the data analysis. These tests include: (i) Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests to examine the association between categorial variables, where the latter was used when assumptions for Chi-square test of independence have not been met; (ii) One-sample Wilcoxon Signed Rank test for examining whether the sample median is equal to a test value of three (i.e., the mid-point of the five-point Likert scale). This test allows to test the hypothesis whether the respondents’ perceptions on the challenges associated with WFH are lower or greater than the neutral level; (iii) Mann–Whitney U-test for testing the difference in distribution of responses between two main groups of respondents according to their gender; and (iv) Spearman correlation test on the relationships between the respondents’ self-report work productivity, overall satisfaction with WFH and future preference for WFH after the pandemic. That is, the hypothesis whether there is statistically significant association among these measurement items. The SPSS software was used to perform these statistical tests.

5. Results

In total, the online survey link was distributed via emails to all 769 consultancy firms on the register. These include firms providing architectural and design, project management, engineering, quantity surveying, and environmental planning services in public sector construction procurement. There were 88 complete responses usable for the data analysis, representing a response rate of 11.44%. While the number of responses is considerably low, it is recognized that the COVID-19 pandemic has placed substantial strain on people’s life globally that could justify the low response rate. Thus, the response rate was considered satisfactory and adequate for this exploratory study, particularly when taking into consideration the risk level of the survey as highlighted above. The respondents’ voluntary participation assumedly reflects their interest and seriousness to share their WFH experiences in the present study. Thus, their responses are useful to reveal some key insights on their WFH experiences during the pandemic times.

The results were reported in three major sections focusing on the respondents’ demographic profile and WFH experiences, their perceptions of challenges associated with WFH on work activities and performance, and their overall WFH satisfaction and future preference for WFH after the pandemic.

Table 1 shows the profile of the respondents with the majority of them (64.7%) aged between 26 and 45 years old. The percentages of male, female and non-binary respondents are 55.7%, 43.2% and 1.1%, respectively. About 70% of the respondents were born in Australia and the percentage of respondents with undergraduate and postgraduate degrees is as high as 90.9%. Similarly, 90.9% of the respondents were employed full-time at the time of survey and majority of them worked in the state of NSW (72.7%). In terms of type of employment, the two major groups were employees of public or private organizations (60.2%) and business owners (33.0%). On the respondents’ working experience in the industry, as high as 40.9% of them have had over 25 years of experience, this is followed by 36.4% of those of between 11 and 25 years of experience, signifying these respondents are very experienced in the industry. While about 30% of respondents preferred not to answer the question on their pre-tax annual job income, the distribution of those indicated their annual income is rather even with about 35% of respondents earned below and above AUD 110,000, respectively. Sixty-eight percent of the respondents were primary income earners in their family. For the two major groups of male and female respondents,

Table 2 shows a cross tabulation between gender and role as primary income earner A Chi-square test of independence confirms that there is a statistically significant association between their gender and role as primary income earner (i.e.,

X2(1) = 4.871,

p = 0.027), with male respondents more likely to be the primary income earners for their family compared to female respondents.

Another respondents’ demographic characteristic that worth examining is the number of hours spent on unpaid domestic household responsibilities during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown periods.

Figure 1 shows the respondents’ average number of hours spent on unpaid domestic work, including (or excluding) home schooling and caring duties if applicable, for their household in a typical week during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown periods according to their gender. It can be seen that the recorded percentages of female respondents are higher when the average number of hours is above five. Focusing on the male and female groups, a Fisher’s exact test was carried out to assess the association between gender and average number of hours spent on unpaid domestic work. The results show that there is a statistically significant association at

p < 0.05 level (

p = 0.025), providing evidence that women on average had spent a greater number of hours on unpaid domestic work for their household compared to man during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown periods. Overall, the respondents were in different individual circumstances including domestic household responsibilities and income support for their family, and these may shape their WFH experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown periods. The statistically significant associations ascertained in these test results prompts the need to investigate if there are significance differences between the male and female groups in terms of their WFH perceptions experiences in the subsequent analysis.

5.1. WFH Experiences

The respondents’ WFH experiences were examined at two levels. First,

Figure 2 compares their normal workplace for most of their working days prior to and during the pandemic in 2020 and 2021. As expected, most of the respondents (84.1%) worked at their company workplace prior to the pandemic including those business owners, who made up about a third of the total number of respondents. A closer examination reveals that the 6.8% (

n = 6) of respondents who worked fully from home prior to the pandemic were not from the employees group. The number of respondents who worked: (i) partly in normal workplace and partly from home, and (ii) fully from home have increased significantly in 2020 and 2021 due to the lockdowns induced by the pandemic. Indeed, with no change for the group working fully from home between 2020 and 2021(37.5%), the percentage of respondents who were working at company workplaces was lowest in 2021 with more respondents moved to work partly in normal workplace and partly from home. Next, they were asked to indicate the use of their home as a workplace prior to the pandemic as illustrated in

Figure 3a. About 50% of the respondents had never or rarely used their home as a workplace and this is followed by another one-third of them who sometimes used their home as a workplace. For the major group of respondents—employees of public or private organizations—who would have little say about their workplace, their WFH experience was further examined in

Figure 3b. While some of them had sometimes or often used their home as a workplace, about two-third of them (64.1%) had no or little WFH experience before the pandemic. In summary, despite some respondents had sometimes used their home as a workplace, the evidence is suggestive that most of them were new to WFH and worked at their company workplace for most of their working days prior to the pandemic. This suggests that they would need to adapt to an unfamiliar way of working with essentially no or little time for preparation and training.

5.2. Perceptions of the Impacts of Challenges Associated with WFH on Work Activities and Performance

Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics and One-sample Wilcoxon Signed Rank test results of the respondents’ perceived impacts of 22 challenges associated with WFH on their work activities and performance. As expected, some challenges are not applicable to all respondents, for example, C3 caring responsibilities and C4 home-schooling. The recorded mean scores range from the lowest of −0.966 to the highest of 0.400 (scale −2 to +2). Seven (out of 22) challenges have recorded negative mean scores (i.e., perceived negative impacts), and the test results show that the median values for five of these challenges are statistically significantly below zero (i.e., neutral level). These challenges are: (i) social interactions with colleagues (C10, mean = −0.966); (ii) communication and/or collaboration with colleagues (C11, mean = −0.591); (iii) team spirit and inspiration (C12, mean = −0.616); (iv) updates on office politics and decisions (C17, mean = −0.357); and (v) feedback from colleagues (C18, mean = −0.476), suggesting that these challenges have been perceived by greater number of respondents (i.e., more than half) to negatively impact their work activities and performance when WFH. It is also worth noting that challenges C10 to C12 ranked top three among the seven challenges of negative mean scores. Turning into the fifteen challenges of positive mean scores, it is rather surprisingly that the recorded mean scores are all marginally above zero with the highest mean score as low as 0.4. However, the test results show that only the median values of three top ranked challenges are statistically significantly greater than zero, signifying the significance of the perceived positive impacts of these challenges on their work activities and performance when WFH among the majority of the respondents. These challenges are: (i) overall work-family balance (C6, mean = 0.400); (ii) mutual trust between you and your work supervisor (C20, mean = 0.357); and (iii) information and communication exchanges via virtual meetings (C22, mean = 0.310). Despite the mixed positive and negative perceived impacts indicated by the mean scores, one should take into consideration the rather high variabilities in the respondents’ responses for most of the challenges as indicated by the high standard deviation values (ranging from 0.777 to 1.255). This wide spread of responses provides suggestive evidence of the diversity of WFH experiences among individual respondents, with extreme responses become more likely. It could be expected that some might had either an extreme positive or negative experience when WFH during the pandemic lockdown periods.

With the detected associations between gender and demographic characteristics,

Table 4 further examines the respondents’ perceived impacts of the 22 challenges according to the two main gender groups—male and female groups. Consistent with results in

Table 3, there are high variabilities in responses for both genders as indicated by the high standard deviation values. For the male group, the recorded mean scores range from the lowest of −1.082 to the highest of 0.458. The corresponding challenges are ‘social interactions with colleagues (C10)’ and ‘overall work-family balance (C6)’. It is worth noting that there are greater number of challenges with negative mean scores (12 out of 22) for male group compared to five negative mean scores in female groups. For the female group, the recorded mean scores range from the lowest of −0.816 to the highest of 0.541. Similar to the male group, ‘social interactions with colleagues (C10)’ has recorded the lowest negative mean score, while the highest positive mean score is for ‘information and communication exchanges via virtual meetings (C22)’. In investigating if there are significant differences between the male and female groups, the Mann–Whitney U-test results show that there are statistically significant differences in distributions of responses between the two groups on their perceptions for five challenges at

p < 0.05 significance level. These challenges are caring responsibilities (C3), feedback from colleagues (C18), and the challenges which are related to availability and accessibility to information, communication and technology (C13, C14 and C15). Although the evidence is suggestive that both groups have different perceptions on the impacts of challenges, the differences are not statistically significant for most of the challenges. This could possibly be explained because of the respondents’ individual circumstances, regardless of their gender, would have shaped their WFH experiences during the pandemic lockdown periods.

5.3. Work Productivity, Overall WFH Satisfaction and Future Preference for WFH

The three measurement items on the respondents’ self-reported work productivity, overall WFH satisfaction and future preference for WFH were examined via the distributions of their responses, along with the corresponding descriptive statistics and inferential statistical test results as summarized in

Table 5.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of the respondents’ self-reported work productivity based on work done per hour when WFH during the pandemic compared to normal workplace before the pandemic. As high as three-quarter of the respondents (75%) reported that they had got more done or as much done as in the normal workplace prior to the pandemic. The respective overall mean score values 3.352 (out of 5). A further test confirms that the median of the respondents’ self-reported work productivity is statistically significant above three (i.e., neutral level, see

Table 5). In examining their self-reported work productivity according to gender, the female group has recorded a higher mean score (3.579) compared to the male group (3.184). However, the Mann–Whitney U test results show that there is no statistically significant difference in distribution between the two groups for their self-reported work productivity (

p = 0.196).

Next, on the respondents’ overall satisfaction with WFH arrangement,

Figure 5 shows that slightly above 60% of the respondents (62.8%) are agreeable that they were very satisfied with WFH arrangement, and about one-fifth (19.7%) were not agreeable. With an overall mean score of 3.570, the median of the respondents’ overall WFH satisfaction is statistically significantly above three (

p < 0.05). Similar to that of self-reported work productivity, the female group recorded high mean score compared to male group on their overall WFH satisfaction (3.892 vs. 3.313). A Mann–Whitney U test confirms that there is a statistically significant difference in distribution of responses between both groups (

U = 1102.5,

p = 0.047). Therefore, it can be concluded that overall satisfaction with WFH arrangement for the female group (mean rank = 48.80) is statistically significantly higher than the male group (mean rank = 38.53).

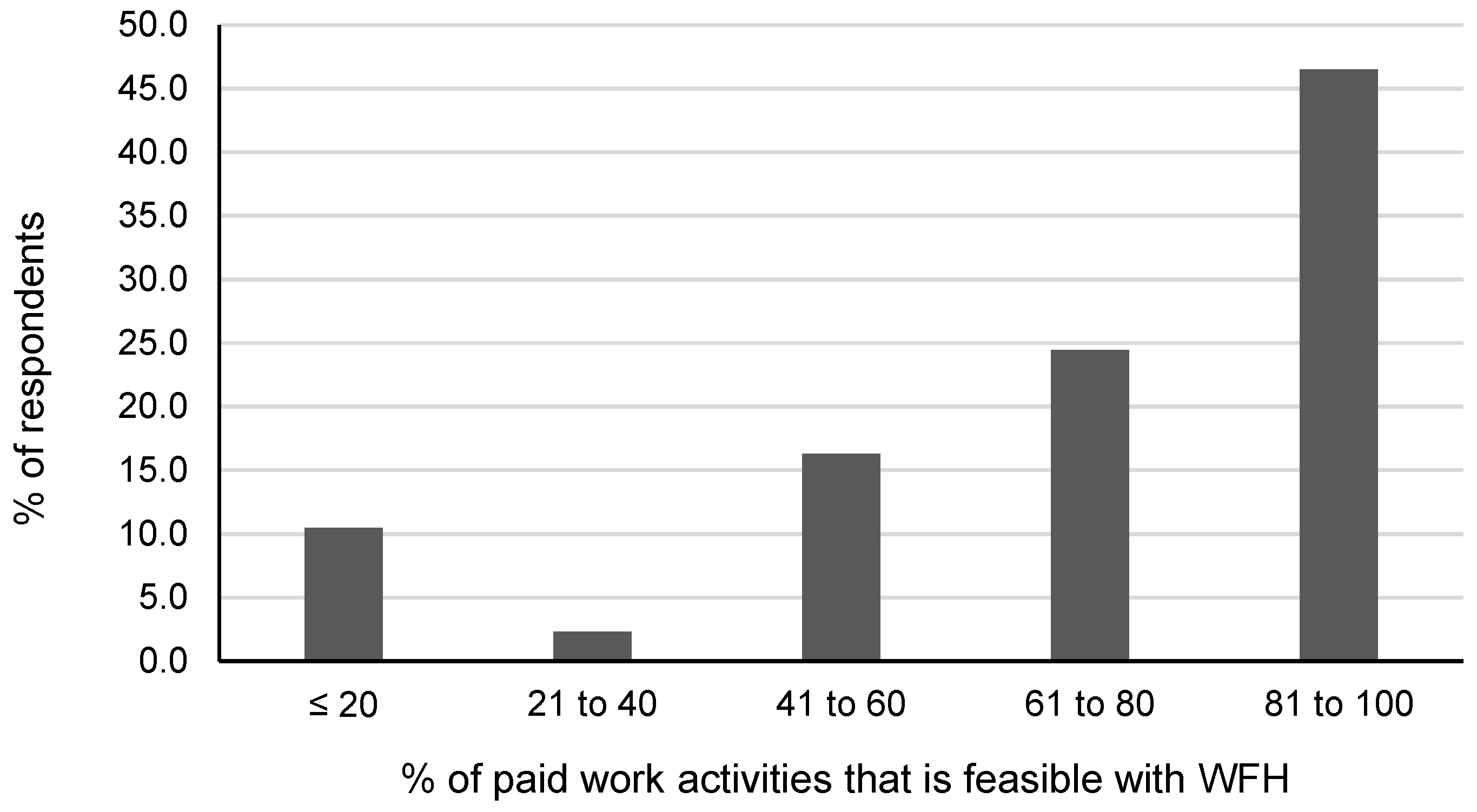

Thirdly, on the respondents’ future preference for WFH after the pandemic, they were asked to indicate the percentage of their paid work activities that was feasible with WFH arrangement based on their WFH experience during the lockdown periods. The recorded values range between 5 and 100% and were regrouped into five intervals as shown in

Figure 6. Almost nine in ten respondents (87.21%) reported that above 40% of their paid work activities were feasible with WFH arrangement, and the largest group (46.51%) is those in the category of above 80%. These findings seemingly suggest the feasibility of WFH arrangement among the majority of the respondents. About 65% of them were agreeable that they would like to WFH after the pandemic if there were given an opportunity to do so (

Figure 7). It is worth nothing that the distributions of responses for both overall WFH satisfaction and future preference for WFH are rather consistent, i.e., above 60% were very satisfied and would like to WFH post-pandemic, and just about 20% were dissatisfied and prefer not to WFH. In terms of the descriptive statistics, the mean scores of the respondents’ future preference for WFH are the highest among the three measurement items (see

Table 5). The respective overall mean score values 3.674, with a median that is statistically significantly above three (

p < 0.05). The mean score of the female group is high at 4.0 compared to 3.396 of male group, suggesting a higher preference for WFH for the female group. However, the test results show that the difference in distribution of preference for WFH for both groups is only marginally statistically significant at 10% significance level (

p = 0.105).

To conclude, the associations between gender and the respondents’ self-reported work productivity, overall WFH satisfaction and future preference for WFH were examined. The Fisher’s exact test results in

Table 6 show that there is a statistically significant association between: (i) gender and productivity at 10% significance level (

p = 0.090), and (ii) gender and overall satisfaction with WFH at 5% significance level (

p = 0.044). The correlations between the respondents’ self-reported work productivity, overall WFH satisfaction and future preference for WFH, on the other hand, are all statistically significance at

p < 0.01 level where the tests were performed on the total sample and the two gender groups (

Table 7). These statistically significant positive correlations suggest that as the respondents’ perceived level of work productivity increases, their overall WFH satisfaction increases and they would welcome WFH arrangement post-pandemic, and vice versa. Overall, the results show that the correlation between overall WFH satisfaction and future preference for WFH is rather strong (

r = 0.621), this is followed by moderate correlation between work productivity and future preference for WFH (

r = 0.572), and lastly between work productivity and overall satisfaction with WFH (

r = 0.490). The former two correlations are indeed even stronger for the male group and the correlation coefficients are

r = 0.663 and

r = 0.639, respectively.

6. Discussion

The majority of the respondents had no or little WFH experience before the pandemic. They were new to the WFH arrangement induced by the pandemic lockdowns, which would have brought significant challenges for many of them. On one hand, it could be expected that while individual employees were adopting to an unfamiliar way of work setting, companies were demanding same level of employees’ engagement while they were WFH to facilitate timely responses to changing clients’ needs in the times of pandemics [

41]. The pandemic, on the other hand, has introduced unique circumstances to construction workforce including changes in job situations and household responsibilities (e.g., childcare and home-schooling) following the COVID lockdowns, while also managing their paid workload [

1,

15]. Accordingly, these changes and associated challenges require noteworthy adjustments that many respondents have assumed, which has been demonstrated in the present findings with high variabilities in the respondents’ perceptions of challenges associated with WFH on their work activities and performance, and their self-reported work productivity, overall WFH satisfaction and future preference for WFH after the pandemic.

Indeed, the wide spread of their responses provides suggestive evidence of the diversity of WFH experience among individual respondents. They were in different individual circumstances including domestic household responsibilities and income support for their family, which were found to be statistically significantly associated with gender. Women on average had spent a greater number of hours on unpaid domestic work for their household compared to man during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown periods, consistent with early evidence in the literature (e.g., [

15,

30]). Both male and female groups’ perceptions of the impacts of 22 challenges associated with WFH on their work activities and performance are rather mixed. While some challenges were perceived to positively (or negatively) impact their work activities and performance when WFH, the differences are statistically significance for some of the challenges only (see

Table 4). This seemingly suggests that gender is not the driving factor, and that other factors were at play in shaping their perceptions.

Overall, the results show that the respondents’ perceptions of the impacts of WFH challenges on their work activities and performance are positive for most of the challenges (15 out of 22), signifying that they were adapting well when WFH while some were able to benefit from the flexibility of WFH arrangement. This is evidently demonstrated by the top ranked challenge of ‘overall work-family balance’ (see

Table 3) that recorded the highest positive mean scores, echoing the findings in Pirzadeh and Lingard [

16] and Ogunnusi et al. [

43] on construction workforce positive experience on overall work-family balance while WFH. The potential benefits claimed by their respondents include time saving associated with commuting, feeling safer at home, being able to work flexibly and having more time for family and nonwork activities. Correspondingly, the present findings provide evidence on positive outcome on self-reported work productivity among most of the respondents (75%), who indicated that they had got at least as much, if not more work done, at home. This percentage is slightly lower than the corresponding 88.4% in Parry et al. [

44] and Felstead and Reuschke [

45] of similar measurement scale, which involved office-based employees in the (i) Professional, Scientific and Technical, and (ii) Public Administration and Defence sectors in the UK. Nonetheless, Morikawa [

12] pointed out that quantitative evidence on WFH productivity measure is limited, and authors have used subjective self-reporting WFH productivity which is expressed in relative to their usual workplace. Indeed, Dingel and Neiman [

40] pointed out that, regardless of the percentage of jobs that is plausibly to be performed at home, individual workers’ WFH productivity may vary considerably under a lockdown situation induced by the pandemic. As such, one should interpret the subjective self-reporting WFH productivity of high variability with care, recognizing other individual and firm-related factors may be in play [

12].

Lastly, the results show that as the respondents’ self-reported work productivity increases, their overall WFH satisfaction increases and they would welcome WFH arrangement post-pandemic, and vice versa. Above 60% of the respondents were very satisfied with WFH arrangement and would like to WFH post-pandemic, again echoing the previous findings of preference for WFH post-pandemic among construction workforce in Pirzadeh and Lingard [

16] and Ogunnusi et al. [

43]. The reported percentage of their paid work activities that was feasible with WFH arrangement is generally higher than the industry teleworkable ratio in Dingel and Neiman [

40], signifying the feasibility of WFH and/or remote working arrangements. Indeed, the overall satisfaction with WFH for the female group is statistically significantly higher than the male group, although it is evidenced in the present study that the female group had spent a greater number of hours on unpaid domestic work. This could possibly be explained by the flexibility and benefits afforded by WFH arrangement where the female group was able to get work and nonwork activities done in less time.

7. Research Implications

As one of the very few exploratory studies on WFH experiences among construction workforce, the findings clearly have implications to research community and employing organizations. Thus far, the detected associations between gender and the respondents’ demographic characteristics, their self-reported work productivity and overall WFH satisfaction suggest the need to consider gender effects in similar future studies. Additionally, the detected associations between the respondents’ self-reported work productivity, overall WFH satisfaction and future preference for WFH could serve as a foundation in future research efforts on modelling the relationships among these three constructs using a set of carefully selected measurement items, and taking into consideration the effects of respondents’ demographic characteristics in their model (for e.g., gender and family circumstances). For employing organizations, on the other hand, the divergent WFH perceptions and experiences uncovered could be considered in the development of their protocols on WFH and/or hybrid working arrangements. Considering that WFH has become a ‘new’ normal even after the pandemic [

11,

12,

46], establishing the optimal combination of working some time at the office (or normal workplace) and some time at home—hybrid mode—may be an important agenda for firms continuing with WFH practices. The respective human resource protocols could address the WFH challenges with perceived negative impacts on work activities and performance, for example, the three top ranked negative factors revealed in the present studies are social interactions with colleagues, communication and/or collaboration with colleagues and team spirit and inspiration. These may require new communication tools or virtual alternatives to enhance employees’ engagement. Similarly, WFH challenges that were perceived to positively impact work activities and performance should not be overlooked. In attempts to enhance the positive factors, personal circumstances of individual employees could come at play and should be considered to better support employees while WFH. All in all, individual organizations should recognize that ‘one size does not fit all’ in establishing their WFH and/or hybrid working practices.

8. Conclusions

A group of consultants working in the Australian construction industry participated in this exploratory study and shared their perceptions and experiences of WFH during the pandemic lockdown periods. Most of them were new to the WFH arrangements, which may relatively explain the variabilities of their responses on: (i) the perceived impacts of WFH challenges on their work activities and performance; (ii) self-reported productivity; (iii) overall satisfaction with WFH arrangement; and (iv) and future preference for WFH after the pandemic. The observed heterogeneity in their responses could also be partly explained by their varying individual circumstances and demographic characteristics including domestic household responsibilities, which would have shaped their WFH experiences. It is found that there are statistically significant associations between gender and their responses in some of the measurement items, suggesting the need to consider gender factor in similar future studies.

Overall, the results suggest that most respondents were adopting well when WFH while some were able to benefit from the flexibility of WFH arrangement. This is evidenced in their perceptions of the impacts of WFH challenges on their work activities and performance that are mostly positive. Correspondingly, their self-reported WFH productivity is encouraging where most had got at least as much, if not more work done, at home. The results also show that as the respondents’ self-reported work productivity increases, their overall WFH satisfaction increases and they would welcome WFH arrangement post-pandemic, and vice versa. Most respondents have indicated that WFH arrangement is feasible for a rather high percent of their paid work activities, whereas the female group has a higher preference for WFH arrangement post-pandemic. The research findings clearly have implications to research community and employing organizations. Future studies could explore on the detected associations in the present study through different research designs and analytical techniques. For employing organizations, the divergent WFH perceptions and experiences uncovered could be considered in the development of their protocols on WFH and/or hybrid working arrangements since WFH practices are likely to stay post-pandemic.

A key limitation in this exploratory study is its small sample size. In addition, its focus is on consultants in the industry, thus there is a need to include construction workforce working for other construction-related organizations including construction contracting firms in future studies. Next, this study focuses mainly on the employees’ perspective, and it is obvious that similar future studies should look into employers’ perspective on this subject matter. Indeed, there are many other WFH aspects that future studies could consider including the lessons learnt from WFH practices among different cohorts of construction workforce, and critical factors for successful WFH and/or hybrid working arrangements from both the employees’ and employers’ perspectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L.O.; Methodology, S.K.; Investigation, B.L.O. and B.T.H.L.; Resources, B.T.H.L. and S.K.; Writing—original draft, B.L.O.; Writing—review & editing, B.L.O. and B.T.H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the the School of Build Environment, Faculty of Arts, Design and Architecture, UNSW Sydney, Australia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of UNSW Sydney, Australia (HC210728, 22 October 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all respondents involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Oo, B.L.; Lim, T.H.B. Changes in job situations for women workforce in construction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Constr. Econ. Build. 2021, 21, 34–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jin, Y.; Li, W.; Meng, Q.; Hu, X. Impacts of COVID-19 on construction project management: A life cycle perspective. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022; ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Pamidimukkala, A.; Kermanshachi, S. Impact of COVID-19 on field and office workforce in construction industry. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2021, 2, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, F. COVID-19: Main challenges during construction stage. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 29, 1817–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. COVID-19 Causes Devastating Losses in Working Hours and Employment. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_740893/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Martin, B.H.; MacDonnell, R. Is telework effective for organizations? A meta-analysis of empirical research on perceptions of telework and organizational outcomes. Manag. Res. Rev. 2012, 35, 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Golden, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2015, 16, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arntz, M.; Yahmed, S.B.; Berlingieri, F. Working from home and COVID-19: The chances and risks for gender gaps. Intereconomics 2020, 55, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezak, E.; Carson-Chahhoud, K.V.; Marcu, L.G.; Stoeva, M.; Lhotska, L.; Barabino, G.A.; Ibrahim, F.; Kaldoudi, E.; Lim, S.; Marques da Silva, A.M.; et al. The biggest challenges resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic on gender-related work from home in biomedical fields—World-wide qualitative survey analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacini, L.; Gallo, G.; Scicchitano, S. Working from home and income inequality: Risks of a ‘new normal’ with COVID-19. J. Popul. Econ. 2021, 34, 303–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, N.; Tappin, D.; Bentley, T. Working from home before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for workers and organisations. N. Z. J. Employ. Relat. 2020, 45, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, M. Work-from-home productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Japan. Econ. Inq. 2022, 60, 508–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutarto, A.P.; Wardaningsih, S.; Putri, W.H. Factors and challenges influencing work-related outcomes of the enforced work from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: Preliminary evidence from Indonesia. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2022, 41, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raišienė, A.G.; Rapuano, V.; Varkulevičiūtė, K.; Stachová, K. Working from home—Who is happy? A survey of Lithuania’s employees during the COVID-19 quarantine period. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, B.L.; Lim, T.H.B.; Zhang, Y. Women workforce in construction during the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and strategies. Constr. Econ. Build. 2021, 21, 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirzadeh, P.; Lingard, H. Working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: Health and well-being of project-based construction workers. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Effects of COVID-19 Strains on the Australian Economy. 2022. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/effects-covid-19-strains-australian-economy (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Ayat, M.; Kang, C.W. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the construction sector: A systemized review. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.D.; Staley, J.A. Safety and health implications of COVID-19 on the United States construction industry. Ind. Syst. Eng. Rev. 2021, 9, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.H.; Abdulmajeed, H.A. Improving construction safety: Lessons learned from COVID-19 in the United States. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasco, R.F.; Fox, S.J.; Johnston, S.C.; Pignone, M.; Meyers, L.A. Estimated association of construction work with risks of COVID-19 infection and hospitalization in Texas. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2026373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, W.; Gibb, A.G.; Chow, V. Adapting to COVID-19 on construction sites: What are the lessons for long-term improvements in safety and worker effectiveness? J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2021, 20, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, S.; Golightly, D.; Ryan, B. Impact of COVID-19 on health and safety in the construction sector. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2021, 31, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, W.H.; Koh, D. COVID-19 and return-to-work for the construction sector: Lessons from Singapore. Saf. Health Work 2021, 12, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, C.; Simpeh, F. Implementation challenges of COVID-19 safety measures at construction sites in South Africa. J. Facil. Manag. 2020, 19, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, R.S.; Harrison, D.A. The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1524–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bailey, D.E.; Kurland, N.B. A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland, J.; Charlton, A. The Australian labour market and the early impact of COVID-19: An assessment. Aust. Econ. Rev. 2020, 53, 297–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, L.; Churchill, B. Dual-earner parent couples’ work and care during COVID-19. Gend. Work. Organ. 2021, 28, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risse, L.; Jackson, A. A gender lens on the workforce impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Aust. J. Labour Econ. 2021, 24, 111–143. [Google Scholar]

- Etheridge, B.; Spantig, L. The Gender Gap in Mental Well-Being during the COVID-19 Outbreak: Evidence from the UK; Paper No. 2020-08; Institute for Social and Economic Research: Colchester, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew, K.; Anand, P. COVID-19 and the UK labour market. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2020, 36 (Suppl. 1), S215–S224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Fuller, S. COVID-19 and the gender employment gap among parents of young children. Can. Public Policy 2020, 46, S89–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichelt, M.; Makovi, K.; Sargsyan, A. The impact of COVID-19 on gender inequality in the labor market and gender-role attitudes. Eur. Soc. 2021, 23 (Suppl. 1), S228–S245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Rameezdeen, R.; Baroudi, B.; Ahn, S. Mobile ICT–induced informal work in the construction industry: Boundary management approaches and consequences. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; Francis, V. The work-life experiences of office and site-based employees in the Australian construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2004, 22, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekchiri, S.; Kamm, J.D. Navigating barriers faced by women in leadership positions in the US construction industry: A retrospective on women’s continued struggle in a male-dominated industry. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 44, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Astor, E.; Roman-Onsalo, M.; Infante-Perea, M. Women’s career development in the construction industry across 15 years: Main barriers. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2017, 15, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingel, J.I.; Neiman, B. How many jobs can be done at home? J. Public Econ. 2020, 189, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prodanova, J.; Kocarev, L. Employees’ dedication to working from home in times of COVID-19 crisis. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 509–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suratkon, A.; Azlan, A.S. Working from Home (WFH): Challenges and practicality for construction professional personnel. Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. 2021, 12, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunnusi, M.; Omotayo, T.; Hamma-Adama, M.; Awuzie, B.O.; Egbelakin, T. Lessons learned from the impact of COVID-19 on the global construction industry. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2021, 20, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, J.; Young, Z.; Bevan, S.; Veliziotis, M.; Baruch, Y.; Beigi, M.; Bajorek, Z.; Salter, E.; Tochia, C. Working from Home under COVID-19 Lockdown: Transitions and Tensions; Work After Lockdown; University of Southhampton: Southampton, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Felstead, A.; Reuschke, D. A flash in the pan or a permanent change? The growth of homeworking during the pandemic and its effect on employee productivity in the UK. Inf. Technol. People, 2021; ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Hite, L.M.; McDonald, K.S. Careers after COVID-19: Challenges and changes. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2020, 23, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).