Abstract

This paper takes the “Largos” of the Macau Peninsula as the object of study. By applying historical combing and field research, the main functions of Largos are categorized as follows: serving the community, facilitating traffic and promoting religious culture. The paper applied a spatial syntactic theory to establish a model, and three syntactic parameters were used, synergy, integration and choice, to interpret the results of the analysis. Based on the results of the syntactic parameters of Largos, results are divided into four categories. From this, the spaces that require improvements are selected, and corresponding improvement strategies are proposed. Taking Macau’s Largos as an example, this paper aimed to apply a space syntax to analyze the Largos in Macau so as to play a reference role in the effective renewal of urban micro-spaces and small public spaces.

1. Introduction

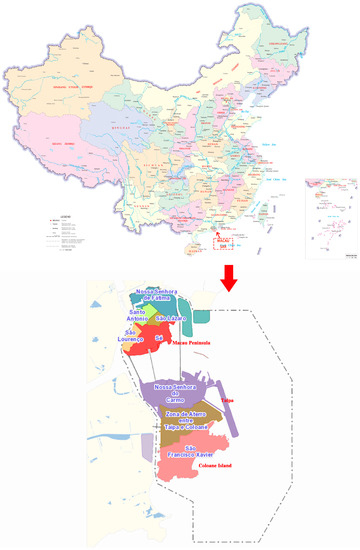

In the era of “stock” development, an objective quantitative evaluation of the built environment is both a prerequisite and a necessary aspect of technical support for urban renewal [1,2]. As a city with a 100% urbanization rate in China, quantitatively analyzing Macau (Figure 1)’s stock space is of urgent practical value and representative significance. Space syntax theory can effectively solve the problem of a lack of quantitative analysis in public space research. “Largo” is a unique type of public space in Macau with important historical and humanistic values, and it is an indispensable place for the daily life of contemporary citizens in the city. “Largo” is a fusion product of Chinese and Western cultures. It was introduced by Portuguese colonists as an open space for performing religious activities in front of a church. In the early days of Macau’s construction, the churches and Largos appearing along straight streets were the symbols of a European medieval Renaissance city [3,4]. In Portuguese, it is called “Largo, Praca, Praceta”. However, the open space in front of a house where the Minnan people live, gather and talk is referred to as “the ground” in Chinese society. To provide both a living environment and to meet the integration needs of both the Chinese and Portuguese people, the nature of Largos gradually changed from being a religious place to a place for more general daily activities [5].

Figure 1.

Macau Location Map.

Earlier studies promoted the cultural value of Largos by exploring their role in promoting tourism [6]. In the process of urban development, the landscape environment and original functions of some Largos have been substantially destroyed and reduced into open-air parking lots, which are spaces without character and sense of place [7]. Some Largos have disappeared, leaving only their names. In the face of such challenges, the government and design authorities have undertaken a sustainable transformation of Largos in important locations [8]. Among them, Largo do Senado and Largo da Sé have been successfully renovated and reused, forming the Macau Model for Urban Rehabilitation and Revitalization (MMURR) [9]. They provide a model for design of the reuse of public spaces in the historic center of the city [10,11]. Largos are rich in physical form and surrounded by brightly colored stucco buildings, and with its exquisite patterns, the Portuguese gravel road has a unique urban imagery [12]. Some scholars explored the spatial characteristics of Largos by using typological analysis and sample studies [13]. In addition, multiculturalism has also had a profound impact on Largos, whether it is a church foreground where Western rituals are held or a temple foreground where traditional culture is passed down, both of which carry rich intangible cultural information [14,15]. Overall, these studies of Largos mainly focus on exploring the value of humanities and arts as represented by Largos [16]. In addition, they analyze the design of space transformation, the protection of cultural heritage and similar aspects.

Nevertheless, issues related to spaces and venues remain in the category of phenomenology, and these issues lack scientific methods and deserve further attention. With the deepening of urban research, the limitations of traditional spatial imagery cognition are increasingly clear. This paper takes a spatial syntactic perspective to interpret the Largos of the Macau Peninsula and to explore spatial cognition based on mathematical quantification. The aim was to contribute to earlier knowledge and provide a more comprehensive perspective for the study of urban public space. This paper firstly provides the development history and quantitative changes of Largos by examining historical information and data from the Macao Cadastral Bureau, while using GIS software to visually represent the location distribution of Largos. Following that, the space syntax is applied to quantitatively describe the spatial structure of the foreland, which organically combines human activities and spatial morphology and seeks to make up for the shortage of qualitative research. The parameters used for quantitative analysis in this paper are integration, synergy and choice. Finally, optimization strategies are proposed for the screened Largos that need to be enhanced.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Foundation Materials

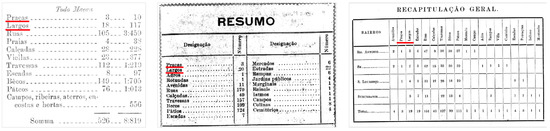

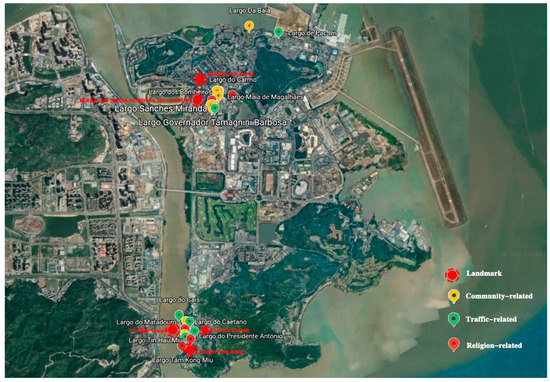

‘Largo’ is a unique square-type public space in Macau. It first appeared as a type of transitional space for churches, initially Largo do São Domingos, during the 1590s. By 1632, there were five Largos: Largo de Santo António, Largo da Companhia de Jesus, Largo da Sé, Largo do São Domingos and Largo do Senado [17,18,19]. The Portuguese maritime trade was hit hard from the middle of the 17th century until the beginning of the Opium War. Regrettably, as a result of the Qing government’s strict control over urban construction and development in Macau, urban development stagnated. During this period, the number of Largos gradually increased, and the period from the end of the Opium War to the late 1930s marks the period of Macau’s urban expansion. During this period, Portuguese authorities began their colonial expansion in Macau and large-scale land reclamation projects alleviated shortages with respect to land resources. Consequently, the number of Largos increased rapidly. Their nature changed from being a meeting place for religious activities to a square in front of a church as a venue for gathering local people undertaking public activities. According to the list of roads in Macau (Figure 2), the number of Largos in 1867, 1906 and 1925 was 27, 23 and 22, respectively. An online search with “Largo” as the keyword on the website https://www.dscc.gov.mo/zh-hant/index.html (accessed on 24 September 2022) identifies a total of 57 Largos, including 38 Largos in the Macau Peninsula, 9 Largos in Taipa and 10 Largos in Coloane Island. We marked the locations of Largos on Google Maps and found that they are mainly concentrated in the neighborhoods where residents live, near churches and temples, or appear as spaces for auxiliary traffic (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Based on the above analysis, this indicates that Largos have existed since the early stage of Macau’s urban development, and with their increasing number and changing nature of use, they have gradually developed into indispensable public spaces in the city.

Figure 2.

Lists of roads in Macau in 1867, 1906 and 1925.

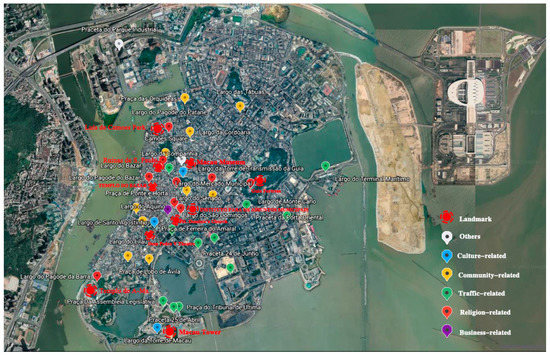

Figure 3.

Location of the Largos(Peninsula Macau, redrawn based on Google Map).

Figure 4.

Location of the Largos (Taipa and Coloane Island, redrawn based on Google Map).

2.2. Space Syntax

Space syntax theory reveals the logical relationship of space, a configurational law that connects material and social properties; that is, cultural and social natures are conveyed via configurations [20,21]. The application of space syntax theory in quantitatively describing the spatial structure of Largos, which organically combines human activities with spatial patterns, can compensate for the dearth of qualitative research. The parameters used for quantitative analysis in this study are integration, choice and synergy. Global integration (Integration Rn) is the accessibility of a node in the system relative to all other nodes in the study area. It measures the potential of a space to attract arrival traffic. Urban centers are typically strong agglomeration spaces. Local integration reflects the ease of linking a node to a nearby node. It would be biased to describe the degree of human flow dispersion. Integration with a topological distance of three can be considered to cover the range of activities completed by walking [12]. A higher choice means that the nodes are selected more frequently, expressing the likelihood of the space being traversed [22]. Synergy is used to describe how easy it is for people to perceive the overall structure via the microenvironment of a certain space [23].

3. The Logic of “Largo” from a Syntactic Perspective

3.1. Classification and Distribution of Largos

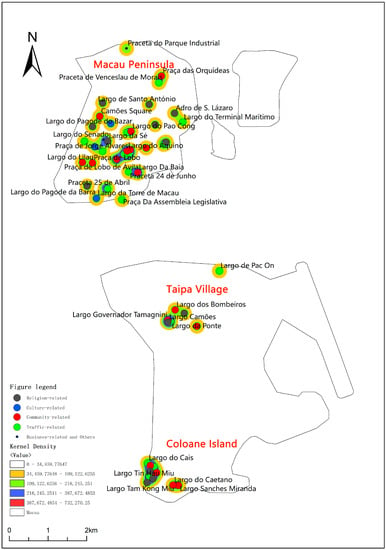

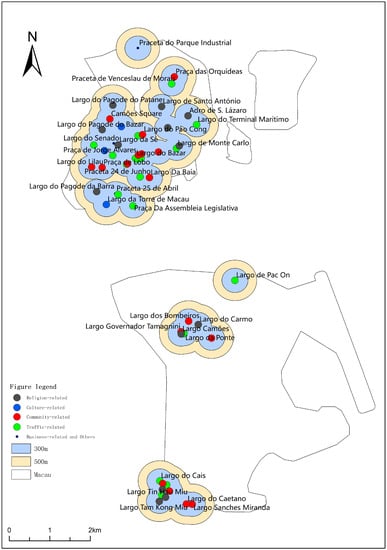

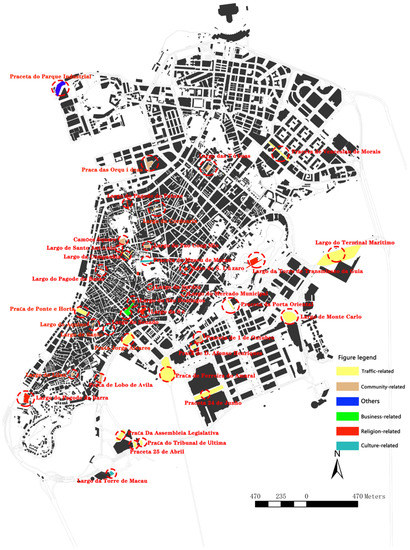

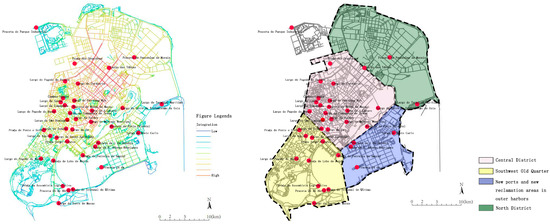

Based on field research and according to the existing functional attributes of Largos, the 57 Largos can be divided into six categories: community-related, traffic-related, culture-related, religion-related, business-related and other types. The main functions of Largos are to serve the community, ease traffic and promote religious culture (Table 1). To understand the distribution of Largos, their latitudes and longitudes were visualized using GIS software. Additionally, kernel density estimation was performed. The Largos were found to be distributed mainly in the Macau Peninsula, Taipa Village and Coloane Island (Figure 5). These three areas were the main living places of Macau residents before the reclamation of Macau. Therefore, it can be assumed that the density of the foreland is necessarily related to the daily life of the citizens. In addition, the Largos were used as the sampling sites to set up a 300 m buffer zone [24], occupying an area of 9.1 km2 and accounting for 65.266% of the total Macau Peninsula area. The 500 m buffer zone would cover the entire Macau Peninsula (Figure 6). The number of Largos in the Macau Peninsula is large and densely distributed, and the samples are typical; thus, the Macau Peninsula was chosen as the research focus of this paper (Figure 7).

Table 1.

Classifications of Largos (Source: https://www.dscc.gov.mo/zh-hant/index.html).

Figure 5.

Kernel density estimation.

Figure 6.

Buffer zone analysis.

Figure 7.

Largos in Macau Peninsula.

3.2. Space Syntax and Its Configuration

3.2.1. Analysis of the Relationship between the Largos and the Macau Peninsula

First, the axial model was established based on an electronic map provided by the Cartography and Cadastre Bureau of Macao SAR. The urban space system is summarized as an axial model, which is generally used in the study of street layouts or large-scale urban networks. The axes have dual functions, including both visual perception and motion state. The space syntax theory stipulates that the longest axis shall be used to cover the entire spatial system. Each axis is regarded as a node. Syntactic computation was performed according to the handover relationship between nodes. Finally, different colors were used to indicate the level of syntactic variables of each axis [20,25].

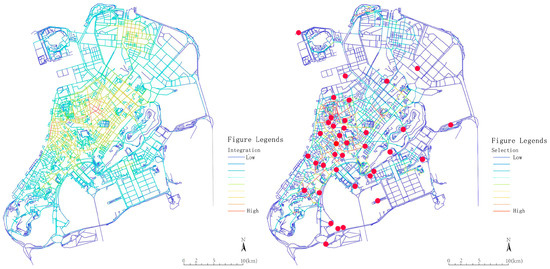

The axes model was imported into Depthmap software for data processing. The global integration of the Macau Peninsula on average is 0.539, and the highest global integration is 0.891. The local integration on average is 1.402, the highest local integration is 4.033, and the synergy is 0.315. As shown in the map of the global integration (Figure 8), the integration core of the city on the Macau Peninsula is the area with the highest accessibility at the whole-city level [26]. Largos’ locations avoid the integration core and are mainly clustered in the historically formed traditional commercial centers and areas with denser residential communities. Since the local degree of integration is much higher than its overall degree, this means that Largos do not contribute to the urban agglomeration effect of the city.

Figure 8.

The global degree of integration and the location of Largos in the Macau Peninsula.

Largos are small and micro-public spaces, and it is justifiable to discuss their accessibility by using local integration. From the perspective of the local degree of integration (Figure 9), the local accessibility of the dense area of the Largos is relatively high, resulting in the formation of a dense and accessible spatial structure. As described by Hillier, this reflects the necessary spatial conditions for a qualified living center [27]. The choice reflects the frequency of space used. According to Figure 7, most of the community-related and religion-related Largos are distributed along streets with a high choice. Public spaces with a high degree of choice attract pedestrian flow, making such places in cities the center of most social and economic activities.

Figure 9.

The local degree of integration and the degree of choice in the Macau Peninsula.

Taken together, Largos avoid the most accessible areas in the city, and their spatial composition prevents highly concentrated activities, thereby forming a local environment with cultural characteristics and a community space with a strong enclosure in the city. At the local level, Largos dominated by natural movement constitute highly pedestrian-accessible areas.

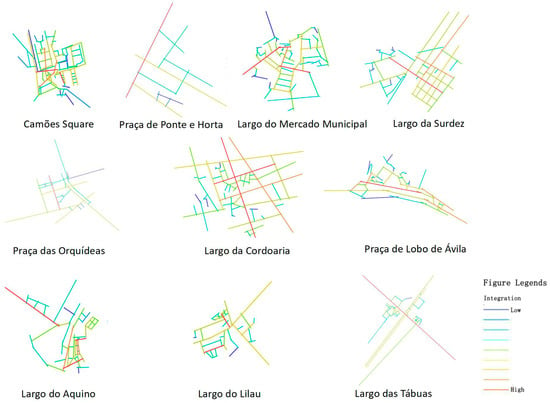

3.2.2. Spatial Characteristics of the Largos

The syntactic analysis of the Largos was performed using the segment model, established on the basis of the axial model. The computational method of the segment model was based on the mathematical method of angle analyses. Theoretically, peoples’ flow in urban roads is believed to be directional, and the degree of street turning often affects citizens’ street choice. Hillier’s research on London indicates that the actual people flow has minimal relevance for the fewest turns but is closely related to the shortest path of the metric distance and the sum of the least angle [27,28]. Therefore, the syntactic analysis of the Largos was performed using the segment model, and the radius was set at 500 m to ensure that the Largos were located in the center of the topological structure for spatial remapping, thereby avoiding the influence of geographic locations. The above analysis shows that Largos avoid the urban core and their spatial structure approach forms a community space rich in local characteristics and life in the city. During the urban development of Macau, the location of churches and temples was also once the center of people’s lives, so this paper selected community-related Largos and religious-related Largos for specific discussion.

For community-related Largos, the statistics of community-related Largos are presented in Table 2 and Figure 10. The value of synergy is expressed as the correlation coefficient (R²) between the local integration (R3) and the global integration (Rn). The value of R² ranges from 0 to 1. An R² value of <0.5 indicates lower synergy, whereas an R² value of ≥0.7 indicates a strong correlation between R3 and Rn. The synergy of Largo do Aquino is the lowest, and it is located at the intersection of residential units and urban roads that cannot be easily discovered. It has a low potential in becoming a destination and involves the slight traversing of traffic. The synergy of Largo do Lilau is 0.564, and its spatial structure restricts access to a significant amount of foot traffic. The users are mainly community residents, and the structure creates a quiet and peaceful living environment (Figure 11). The synergy of the remaining community-related large areas is greater than 0.7, which is strongly correlated with the city. (Figure 11). The synergy of the remaining community-related large areas is greater than 0.7, which is strongly correlated with the city. Combining the other parameters, the community-related Largos can be divided into the following three categories.

Table 2.

Syntax parameters of community-related Largos.

Figure 10.

Community-related Largos.

Figure 11.

Largo do Aquino and Largo do Lilau.

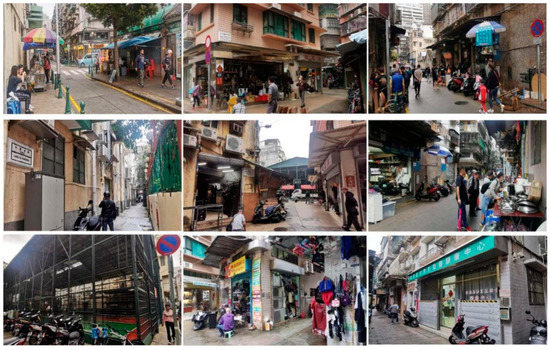

Largos with high integration and high choice are Largo da Cordoaria, Largo do Mercado Municipal and Largo da Surdez. Considering Largo da Cordoaria as an example, the fishing industry in Macau was once prosperous, and local residents were well known for rope braiding. Later, the place evolved into the current community-related Largo. The synergy of Largo da Cordoaria is 0.957, implying that it exhibits a high degree of correlation with the spatial structure of the entire city, with prominent identification features reflecting the common life of Macau. High integration and high choice indicate that the Largos exhibit a strong potential for being a destination in the system with active traversing traffic. Furthermore, site investigation indicates that Largo da Cordoaria is located in the downtown area and is connected to urban roads. Low- and medium-level businesses inside Largo da Cordoaria, such as electrical repair shops, grocery stores and restaurants, serve community residents. Public facilities such as neighborhood centers and basketball courts are also located here. Finally, the location contains public buildings such as Cinema Alegria and O Templo de Lin Kai. This indicates that Largos with high integration and choices are lively places (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Largo da Cordoaria.

Both Largos exhibit high synergy and integration, with a welcoming relationship with the city’s streets and alleys. They can be easily identified and are accessible. The low choice of these Largos indicates that they are less likely to generate traversing traffic and, thus, have low trafficability. The investigation indicates that Praça das Orquídeas is surrounded by residential units, and businesses in this space include coaching centers and music stores. The public facilities in Praça das Orquídeas include children’s toys and sports equipment. The users are mainly community residents, forming a resting space. Largo das Tábuas is the end space; therefore, its choice is low. This indicates that Largos with high integration and low choice tend to form resting environments or dead ends (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Praça de Ponte e Horta.

Largos with low integration and high choice are Praça de Ponte e Horta, Praça de Lobo de Ávila and Camões Square. Praça de Ponte e Horta is in a semi-enclosed state with surrounding buildings, and the types of business are similar to those of Praça das Orquídeas. It is connected to the main road of the city, which makes walking accessibility low, as does a large fountain (Figure 14). This indicates that such Largos do not have high accessibility. They are used intensively and form a lively area on their own.

Figure 14.

Praça das Orquídeas and Largo das Tábuas.

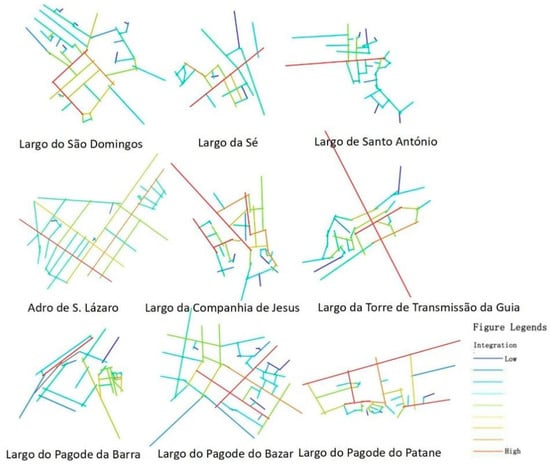

For religion-related Largos, as shown in Table 3, the synergy of Western religion-related Largos is higher than that of Chinese religion-related Largos, which reflects the early urban spatial structure of Macau: that is, “the church and the Largo are connected by rua direita”. The synergy of Largo da Companhia de Jesus, Largo da Torre de Transmissão da Guia, Largo do Pagode da Barra and Largo do Pagode do Patane is lower than 0.7, indicating that these Largos exhibit a weak correlation with the city. To try to understand the entire city by virtue of these Largos’ microenvironments is challenging. The synergy of Largo do Pagode do Bazar is 0.813, which is much higher than that of other Chinese religion-related Largos (Figure 15). This is because, in the process of urban development, the Largos underwent a gradual change from being a purely religious place to a community-related venue, and their original spatial structure also changed. This change improved the accessibility and traversability of Largo do Pagode do Bazar. The degree of synergy of Adro de S. Lázaro is 0.947, indicating that it fits well with overall urban traffic (Figure 16). From the perspective of integration, religion-related Largos exhibit a weaker potential for being a destination than community-related Largos. They are more likely to form a quiet resting place and a buffer zone.

Table 3.

Syntax parameters of religion-related Largos.

Figure 15.

Religion-related Largos.

Figure 16.

Largo do Pagode do Bazar and Adro de S. Lázaro.

Religion-related Largos can be divided into two analytical categories: Largos with low integration and high choice. Examples of such Largos include Largo do São Domingos, Largo da Companhia de Jesus and Largo do Pagode do Patane. Largo do São Domingos is connected to Largo do Senado, which disperses accessibility and provides better synergy. The surrounding areas contain diverse business types, and there are high people flows. It serves as a gathering place not only for local residents but also for tourists and migrant workers (Figure 17). Low integration and high choice indicate that this type of spatial structure forms its own domain in the city, has a unique cultural background or social environment and is full of vitality and imagery.

Figure 17.

Largo do São Domingos, Largo do Pagode da Barra.

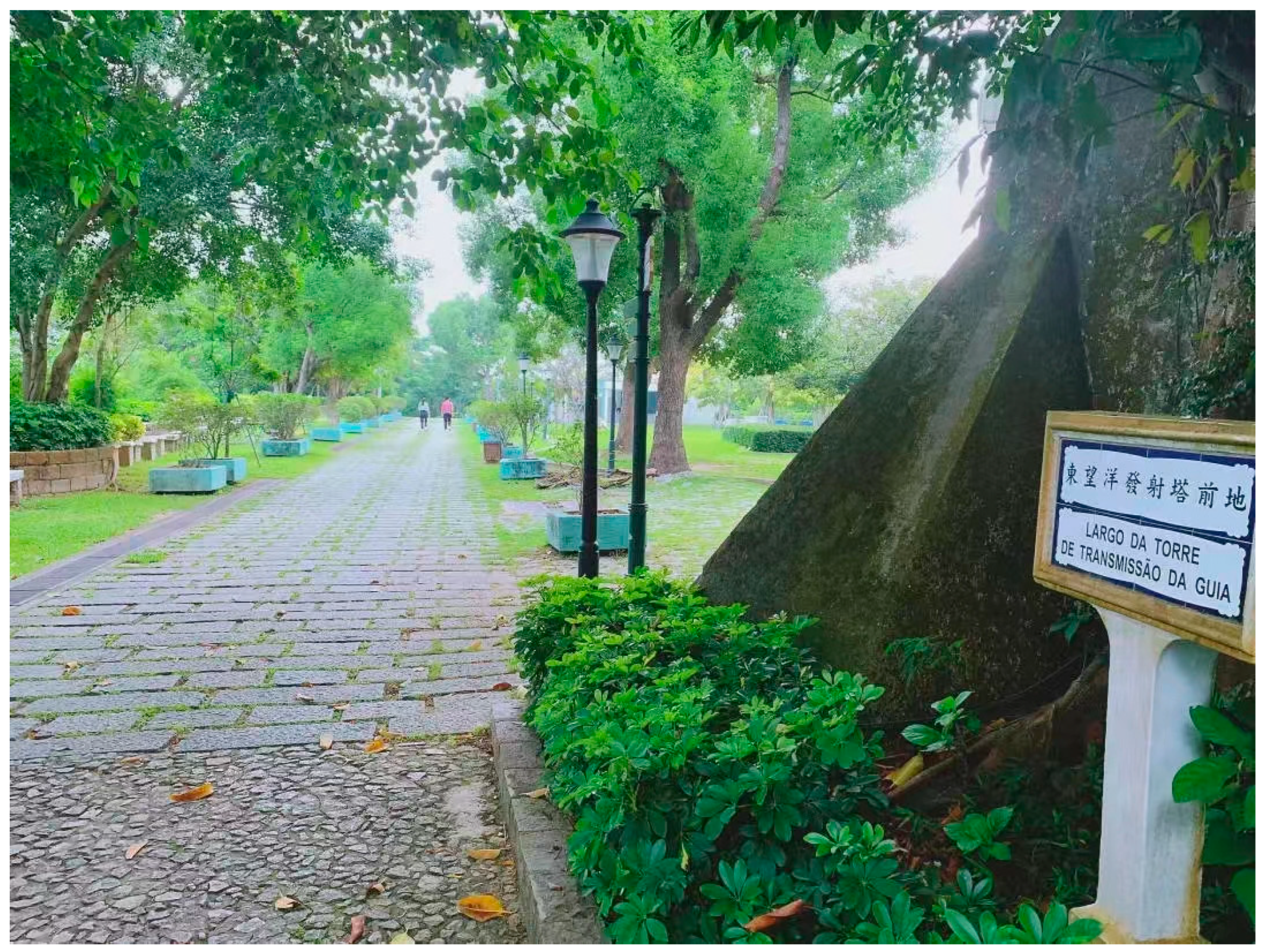

Largos with low integration and low choice—examples of such Largos include Largo do Pagode da Barra and Largo da Torre de Transmissão da Guia. Largo do Pagode da Barraa is adjacent to the motorway, which accounts for its low walking accessibility, poor synergy with the city and only having a few pedestrians crossing the space. Although resting facilities have been established, they are only used by a small number of nearby residents during the nonholiday period, and overall, such Largos are isolated from the city (Figure 15). Largo da Torre de Transmissão da Guia is a “ religion-related “ Largo. The Largo is located in Guia Hill, a famous scenic spot on the Macau Peninsula, with no residential community around it and tourists are the main user group. It is also isolated from the city (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Guia Launch Tower Largo.

3.2.3. Summary

According to Hillier’s Space is the Machine, the synergy between the local area and the overall space determines an area’s vitality and safety. The synergy of the two types of Largos is mostly greater than 0.7, indicating that most Largos have a high vitality and are safe environments. Largos with high integration and high choice have strong accessibility, with many people traversing, and easily form regional centers. Largos with high integration and low choice form peaceful and pleasant living habitats. Largos with low integration and high choice have strong local characteristics. Largos with low integration and low choice have poor vitality and are isolated from urban centers.

4. Summary of Largo Problems and Enhancement Suggestions

4.1. Summary of the Problems

As a special type of public space in the evolution of Macau’s urban development, Largos were transformed from a single religious place in the early days into a comprehensive space for citizens’ daily activities. Today, Largos function in promoting religious culture, serving community life and relieving traffic pressure. Analyzing the results of the aforementioned synergy, integration and choice, Largos can be classified into those with “high integration and high choice”, “high integration and low choice”, “low integration and high choice” and “low integration and low choice”. We conducted a field survey, which mainly included the taking of on-site photos, and the actual current preservation and use of Largos. Largos that could be upgraded were extracted for summary (Table 4). To tackle the common problems of the current situation of Largos, it is necessary to improve the efficiency of the public use of space, diversify the functions of space and pass on cultural values. All are effective strategies for optimization.

Table 4.

Elevatable Largos.

The lack of humanized designs leads to spaces being used for a single function. Largos, which are mainly used for community life services, have diverse space users and often meet the needs of public use and promote socialization. However, the ancillary facilities provided in the Largos are mainly common sports equipment and leisure seats, failing to provide human-oriented designs for user needs, such as seating for face-to-face communication, locations for supervising children’s activities and pergolas for shading from the sun. They also lack stable maintenance.

A loss of spatial vitality occurs due to the occupation of Largos. Due to the completeness of urban construction, the existing space in the old part of the Macau Peninsula lacks adequate public service facilities. This results in the occupation of the foreground by some motor vehicles, and the lack of both facilities and space leads to the space losing its original vitality.

The closed landscape space affects the spatial potential. Some of the Largo spaces are cluttered and closed, making it difficult for users to access them and leading to the underutilization of the landscape space, thus forming a negative space.

4.2. Improvement Measures

Macau has been fully urbanized, and Largos, as the primary type of stock space, have high research significance in the context of current urban renewal. This study rises above the limitations of the lack of scientific quantification in traditional public space research. To do so, it applied the theory of space syntax to parameterize the main categories of Largos in Macau in order to summarize common practical problems and to provide enhancement strategies. This study proposes countermeasures in three dimensions, namely, spatial layout, public use and cultural heritage.

The composite function of the Largos should be improved, refined designs should be encouraged and behavioral activities of different types of people should be met. In addition, efficient landscape forms should be created, existing landscape green space use efficiency should be improved, landscape forms should be enriched, and accessibility and interactivity should be enhanced [29]. Finally, the necessary Largos space should be regulated using social governance to regulate spatial order, introduce sports and leisure facilities, form interaction spaces and add vitality to Largos.

There are three levels relative to the public use of Largo spaces: access, usage and communication. The accessibility of Largos is mainly limited by road connectivity and transportation convenience, and some Largos are difficult to access due to insufficient pedestrian space. As a result, a better distribution of transportation is needed to create a long-term transportation plan. In terms of usage, attention should be given to the usage characteristics of different types of users, and leisure facilities should be improved. Public spaces that encourage social interaction are undoubtedly successful, and it is worth exploring how leisure-oriented Largos are shaped into interactive spaces.

Macau is the oldest European settlement in China, and Largos have been in existence since the Ming Dynasty. Currently, the functions of Largos, such as rituals, opportunities and lives and transportation, are closely related to the life of Macau citizens, and tourist activities are not only a valuable for cultural heritage but also act as carriers for transmitting intangible culture. Therefore, Largos’ strong cultural identifiability and regional characteristics should be highlighted in the renewal process in order to attract socioeconomic investment and achieve sustainable development via cultural inheritance and innovation.

5. Conclusions

This study illustrates the important historical and cultural values and the distribution classifications of Macau’s Largo, and this study mainly applied Depthmap software to calculate the metrics of space syntax for the Largos of Macau Peninsula. Additionally, the study combined the space syntax theory and relevant parameters to sort out the coupling relationship between the Largos and the Macau Peninsula, as well as the spatial characteristics of the Largos, from the spatial logic level. The main conclusions are as follows.

First, the study analyses the relationship between Largos and the overall spatial structure of Macau city based on space syntax. A total of 38 Largos exist on the Macau Peninsula; however, they are not concentrated in the most accessible urban centers but are distributed near crowd-friendly neighborhoods and religious sites, thereby creating a pedestrian-friendly local environment.

Second, the Largos are classified into different types, namely, “high integration and high choice”, “high integration and low choice”, “low integration and high choice” and “low integration and low choice” based on syntactic parameters. They form regional activity centers, pleasant living environments, unique places and negative spaces that are isolated from the city.

Third, based on the results of the parameter measurement, six Largos that can be upgraded are selected from the four types of Largos: Praça das Orquídeas, Largo das Tábuas, Praça de Ponte e Horta, Largo do Aquino, Largo do Pagode da Barra and Largo da Torre de Transmissão da Guia (Figure 15). All have practical problems, including their relations to single spatial function, occupied space and closed space. In response to the above problems, the efficiency of the use of Largos should be improved, the frequency of public use should be enhanced, and humanistic and historical values should be highlighted.

With reference to the results of spatial syntactic parameters, this paper selected six Largos that need to be improved in the Macau Peninsula and proposes that the main directions for improvement are to improve the efficiency of public use, diversify spatial functions and pass on cultural values. For each of the six Largos, targeted improvement strategies are also proposed (Table 4). The spatial syntactic model provides an effective method for the quantitative study of Largos and a new perspective for the study of similar urban public spaces. When the current city enters the stage of stock renewal, improving the existing environment and including the optimization of public space in communities and traditional historical blocks becomes particularly important. An analysis of the spatial structure by using space syntax and proposing a realistic update plan based on parameter variables are effective methods for improving the urban public space. Further studies will be aimed at developing specific Largo-regeneration designs based on this study’s findings, in addition to conducting in-depth explorations of enhancement strategies in order to develop a comprehensive understanding of the conservation and regeneration of Macau’s Largos.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and J.C.; methodology, S.L.; validation, Y.Z. and J.C.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation, S.L.; resources, J.C.; data curation S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z.; supervision, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Zhejiang Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project, grant number 23NDJC359YB.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pan, M.Y.; Shen, Y.F.; Jiang, Q.C.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.H. Reshaping Publicness: Research on Correlation between Public Participation and Spatial Form in Urban Space Based on Space Syntax—A Case Study on Nanjing Xinjiekou. Buildings 2022, 12, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Oca, S.; Ferrante, A.; Ferrer, C.; Pernetti, R.; Gralka, A.; Sebastian, R.; Veld, P.O. Technical, Financial, and Social Barriers and Challenges in Deep Building Renovation: Integration of Lessons Learned from the H2020 Cluster Projects. Buildings 2018, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q. Protection and Utilization of Historical buildings in Macao. Centr. China Arch. 2007, 8, 206–210. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Q.; Sheng, J. Urban Planning and Development in Macao. Eng. J. Wuhan Univ. 2005, 6, 115–119. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Grzybek, H.; Xu, S.; Gulliver, S.; Fillingham, V. Considering the Feasibility of Semantic Model Design in the Built-Environment. Buildings 2014, 4, 849–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. The front space of Macao. Cult. J. 2004, 53, 1–36. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, R.; Wu, Y. Macao Front Land; Hong Kong Sanlian Bookstore: Hong Kong, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Kawasaki, M. Urban revitalization in highly localized squares: A case study of the Historic Centre of Macao. Urban Des. Int. 2018, 23, 34–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Wang, X. Restoration of Macau Historic District Square—Traditional Revival and its Contribution to urban culture identification. World Arch. 2009, 12, 28–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, R. Renovation and Reuse of public Space in urban historical Center—Experience of Reconstruction of Square in Macao historical urban Area. Decoration 2007, 3, 16–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Herthogs, P.; Debacker, W.; Tuncer, B.; De Weerdt, Y.; De Temmerman, N. Quantifying the Generality and Adaptability of Building Layouts Using Weighted Graphs: The SAGA Method. Buildings 2019, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Wei, M.; Zhi, Y.; Xi, J. Reconstruction of urban leisure green space walking space network based on behavior simulation: A case study of Suzhou Huqiu Wetland Park. Geogr. Geo-Inform. Sci. 2022, 38, 79–88. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Cheng, Z. Analysis on spatial characteristics of Macao Front area. Chin. Landsc. Arch. 2015, 31, 57–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J. Research on the Space Use of Temple Front in Macao. Master’s Thesis, Huaqiao University, Macao, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M. The Influence of Multi-Culture on the Space of Macao. Master’s Thesis, Huaqiao University, Macao, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zolfagharkhani, M.; Ostwald, M.J. The Spatial Structure of Yazd Courtyard Houses: A Space Syntax Analysis of the Topological Characteristics of the Courtyard. Buildings 2021, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xuan, F. Urban Development of Macao. Huazhong Arch. 2002, 6, 92–96. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, K. Touch of Alienation in the Celestial Empire: Western Civilization in Macau, 16–19 Centuries; Jinan University Press: Guangzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, X. Development of Urban architecture in Macao. Chin. Foreign Arch. 2004, 4, 66–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. On space Syntax. Architect 2004, 3, 33–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sun, S.; Lin, K.; Lin, J. Post-use evaluation of public space in traditional villages and towns from the perspective of space syntax. South. Arch 2022, 4, 99–106. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Guo, W. A study on the mechanism of place image transmission and continuation based on spatial syntactic Analysis: A Case study of Changsha Historic City. Mod. Urban Res. 2014, 1, 89–95. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, E.; Martin, B.; Lopez-lambas, M.E. Evaluating the impact of urban design scenarios on walking accessibility: The case of the Madrid ‘Centro’ district. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Bai, Y. Progress and prospect of spatial syntax research. Geogr. Geo-Inform. Sci. 2014, 30, 82–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S.; Byrne, J.; Pickering, C. A systematic quantitative review of urban tree benefits, costs, and assessment methods across cities in different climatic zones. Urban For. Urban Gree 2012, 11, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, B. Space Is the Machine; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, J. Research on Protection and Renewal of Zhongshan Road Historical District based on Space Syntax. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University of Technology, Qiandao, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.K. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).