Abstract

This article is a critical analysis of the conservation of a historic earth building: the Saint Bartholomew’s Church in Nigeria. It presents the conservation actions carried out through the application of conservation principles adapted to local context and contributes to building knowledge regarding building conservation in Africa. The conservation actions consisted of diagnostics, technical interventions and developing guidance for future maintenance of the building. The conservation was carried out between August 2021 and April 2023. A dualistic approach that combines local resources and internationally acceptable conservation practices was employed in the conservation of the church. This approach ensured that the appropriate interventions were carried out on the church building fabric simultaneously with training and knowledge exchange between experts from Nigeria and the UNESCO World Heritage site in Djenne, Bamako, Mali. This article highlights the challenges of conserving earthen architectural conservation in the 21st century and how these challenges can be mitigated through repair and documentation.

1. Introduction and Overview of the Church Architecture

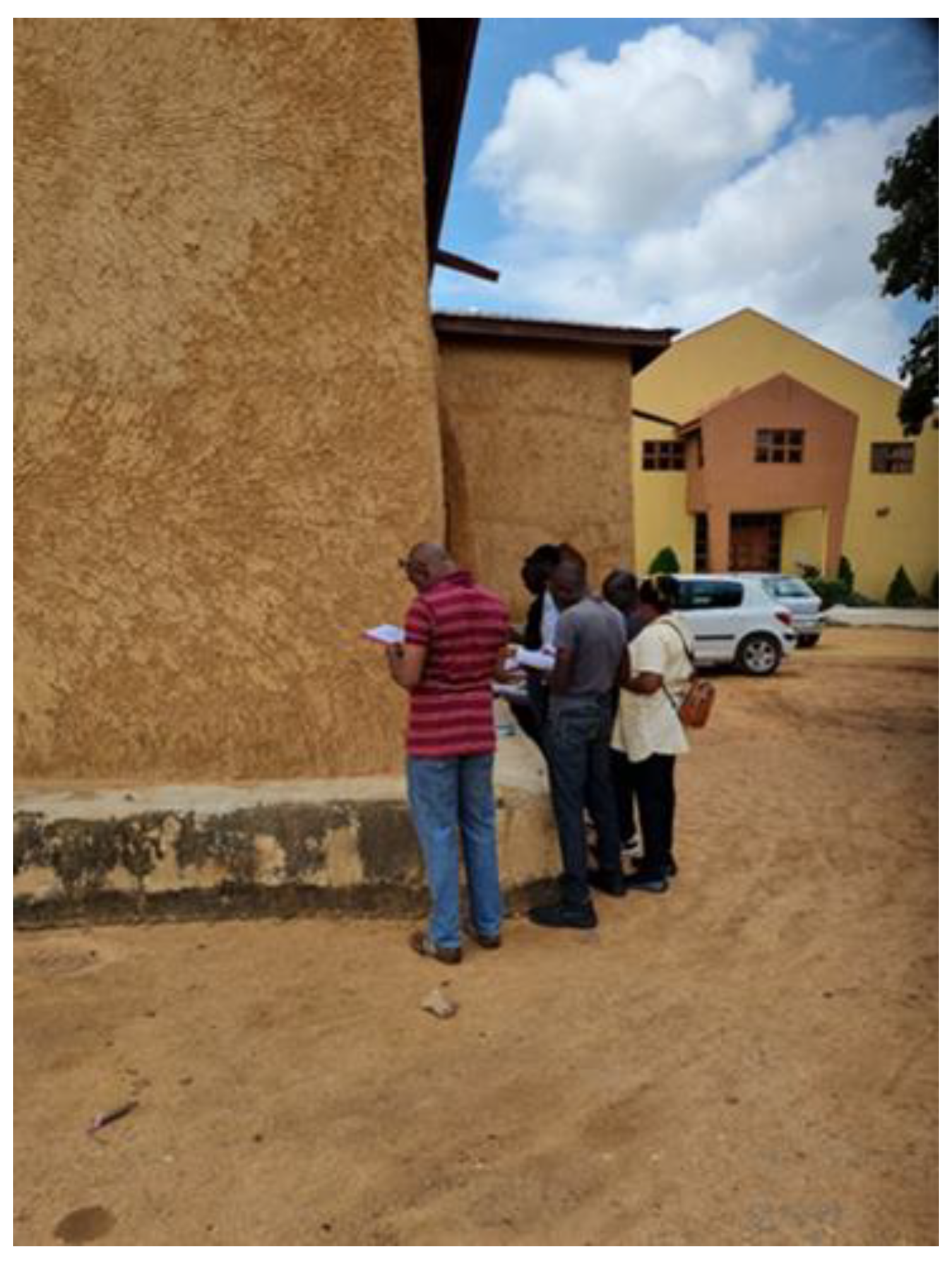

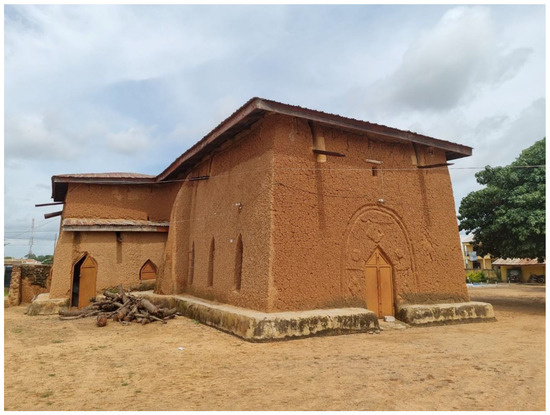

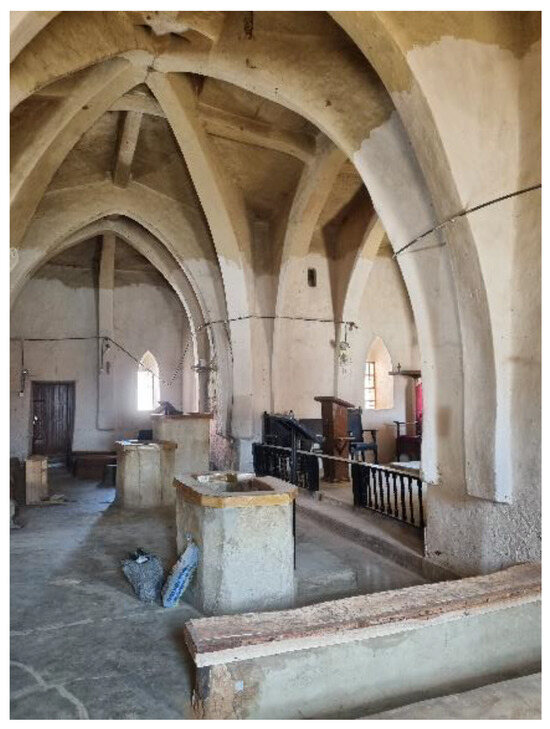

Wusasa is a suburb of Zaria, Kaduna State, Nigeria. It was founded in 1928 as a Christian mission field after the Christian community outgrew the space, the Emir of Zaria, allocated to them within the walled city [1]. Upon moving to this new location, Reverend Guy Bullen commissioned the Sarkin Maginan Zazzau or Sarkin Magina (head of builders in Zaria) to build the St Bartholomew Church (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3), one of the oldest church buildings in northern Nigeria. The building was completed in 1929 and dedicated on Easter Sunday, 20 April 1930 [2].

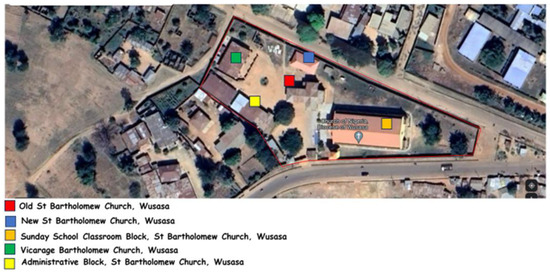

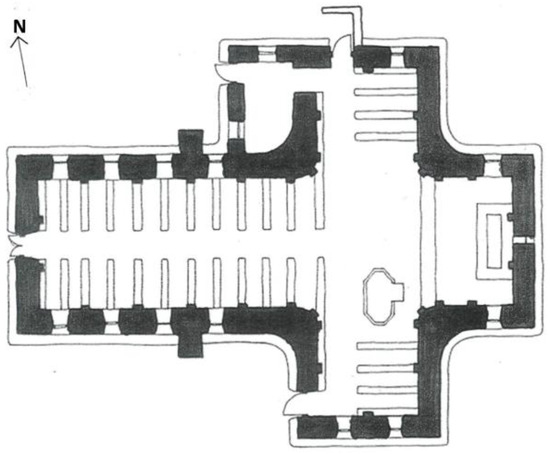

St Bartholomew Church building was one of three buildings constructed by the Christian missionaries in 1928 [2]. The other two significant buildings were the administrative building for the St Francis of Assisi College and a residential building, the Guy Bullen House. St Bartholomew Church reflects the traditional Hausa architectural style adapted to a cruciform church plan, in line with Anglican traditions, with the altar axis oriented to the east. The adaptation and use of local materials to interpret church architecture was contrary to other church buildings of the time. Other churches used imported European building materials such as cement and metal roofing sheets [3]. The building has maintained its original form over the years, and no addition has been made to its original floor plan.

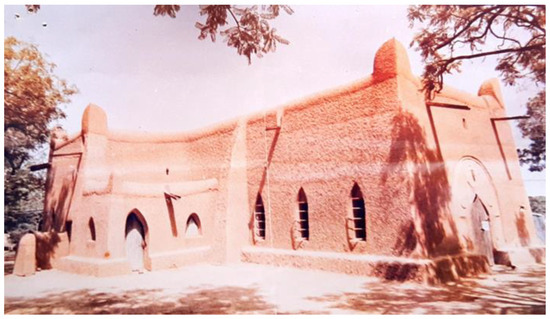

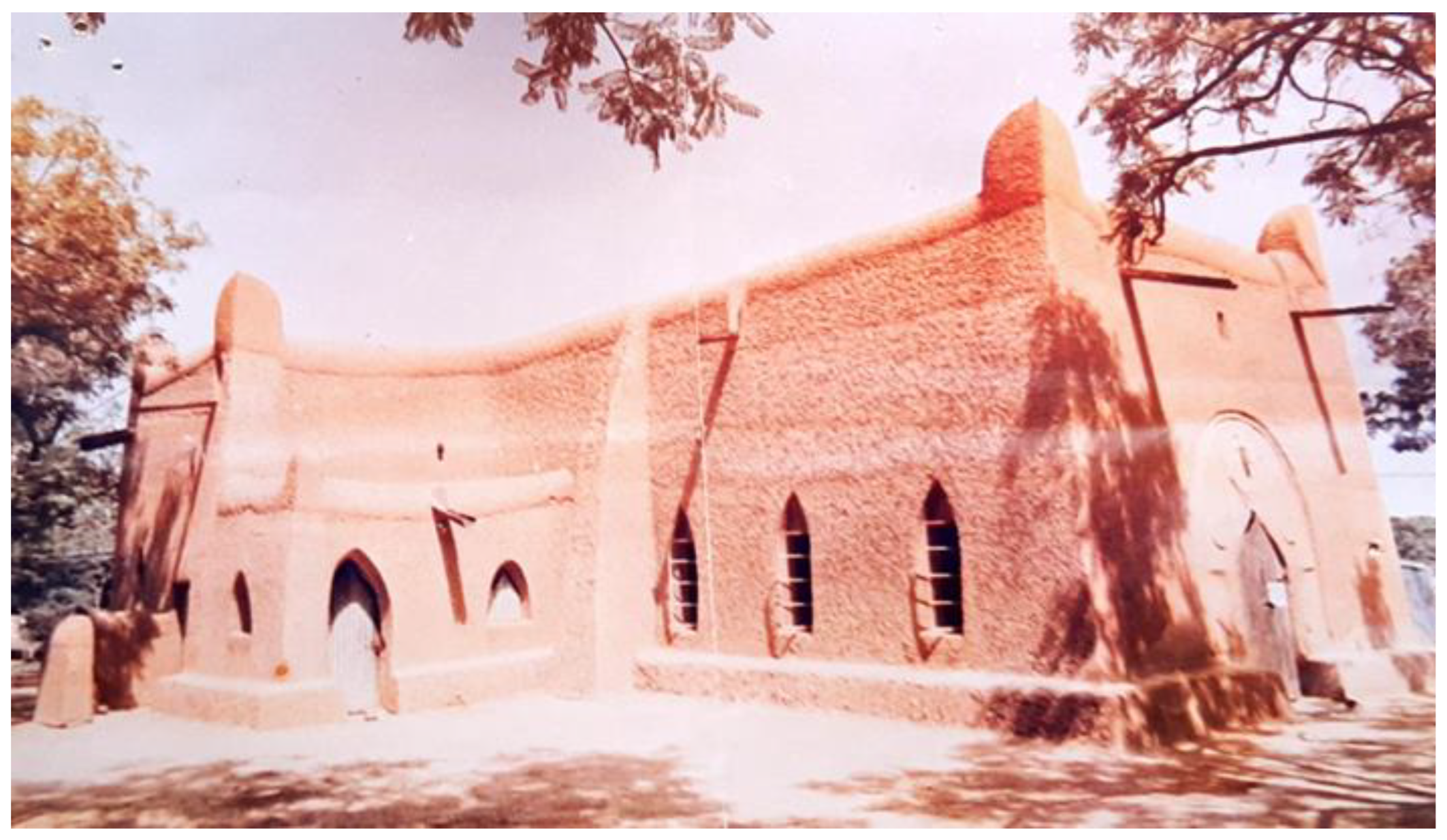

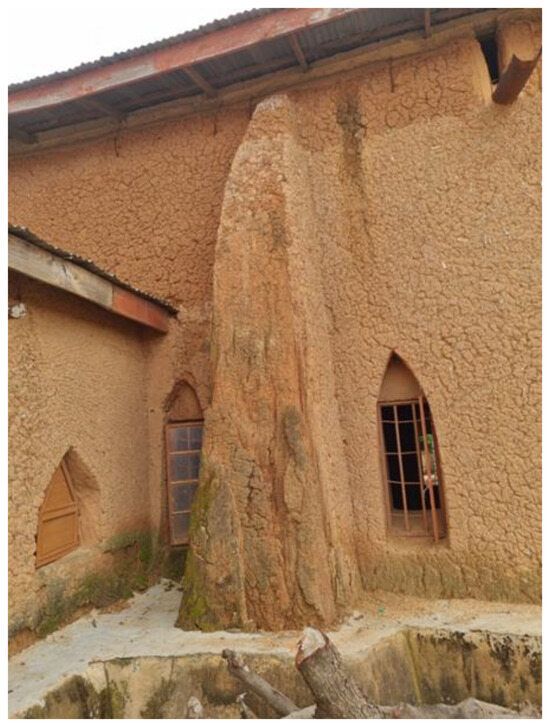

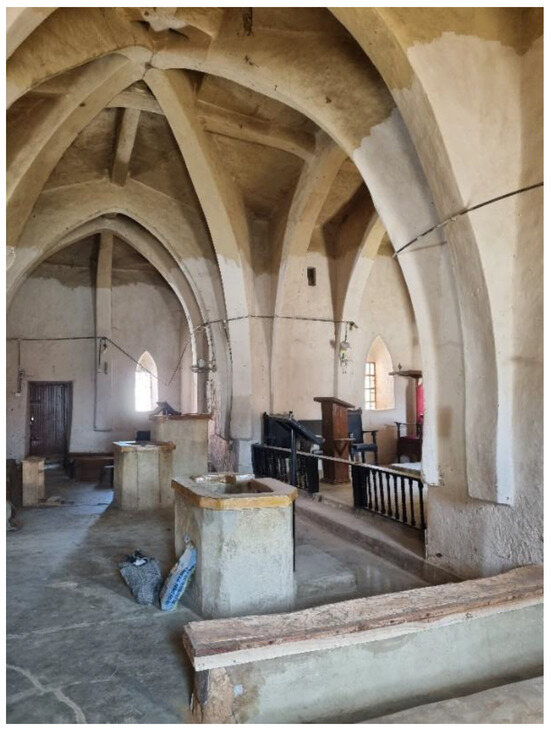

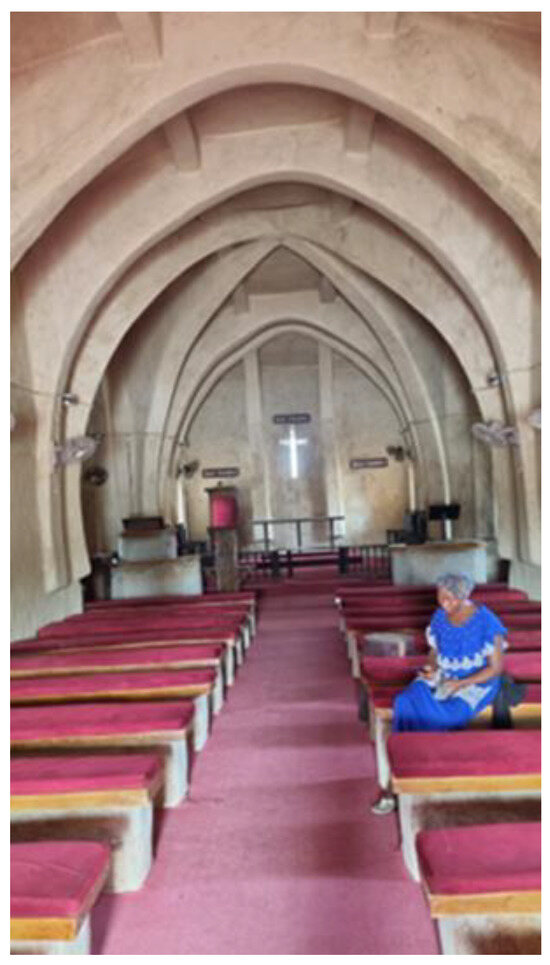

The building consists of thick earth walls, about 600 mm thick, covered with earth domes. The domes are supported by a system of interior arches and vaults reinforced with deleb palm (Borassus aethiopum). The earth domes are plastered with earth and drained through gutters (ndararro) in the parapet earth walls (Figure 3), capped at each corner by the decorative zanko or “horns” modelled in earth. The zankaye (plural of zanko in Hausa) remained until 2003 when a metal roof was introduced to protect the earth roof and to reduce the required annual maintenance at the end of each rainy season. This intervention was not carried out properly—the roof overhangs were insufficient to direct rainwater away from the walls—and resulted in accelerated erosion of the earth buttresses, threatening the structural stability of the building.

Figure 1.

Site plan of the premises of St Bartholomew Church, Wusasa. Source: Google Earth.

Figure 1.

Site plan of the premises of St Bartholomew Church, Wusasa. Source: Google Earth.

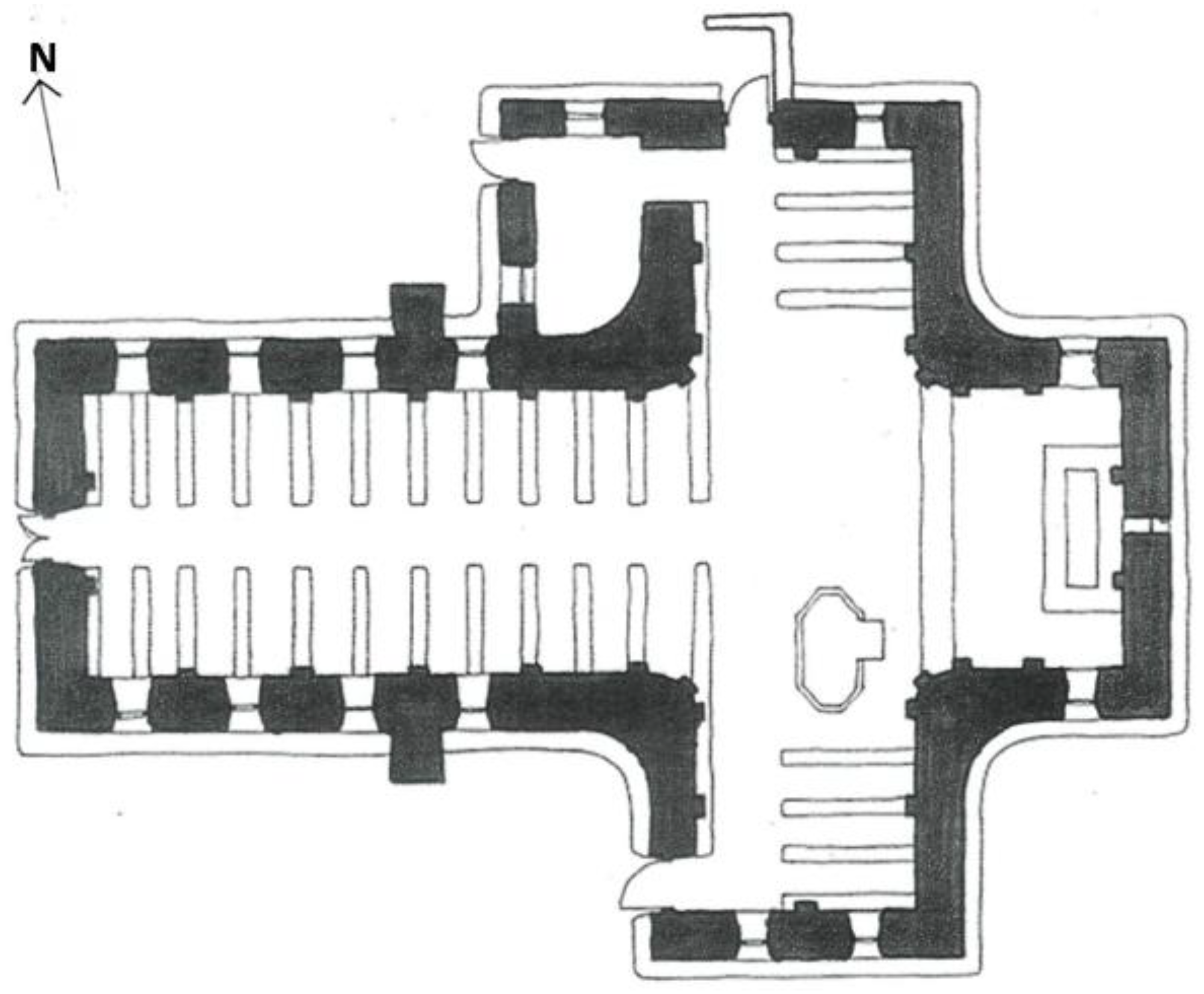

Figure 2.

Floor plan of St Bartholomew Church, Wusasa, developed using Moughtin (1985) [4].

Figure 2.

Floor plan of St Bartholomew Church, Wusasa, developed using Moughtin (1985) [4].

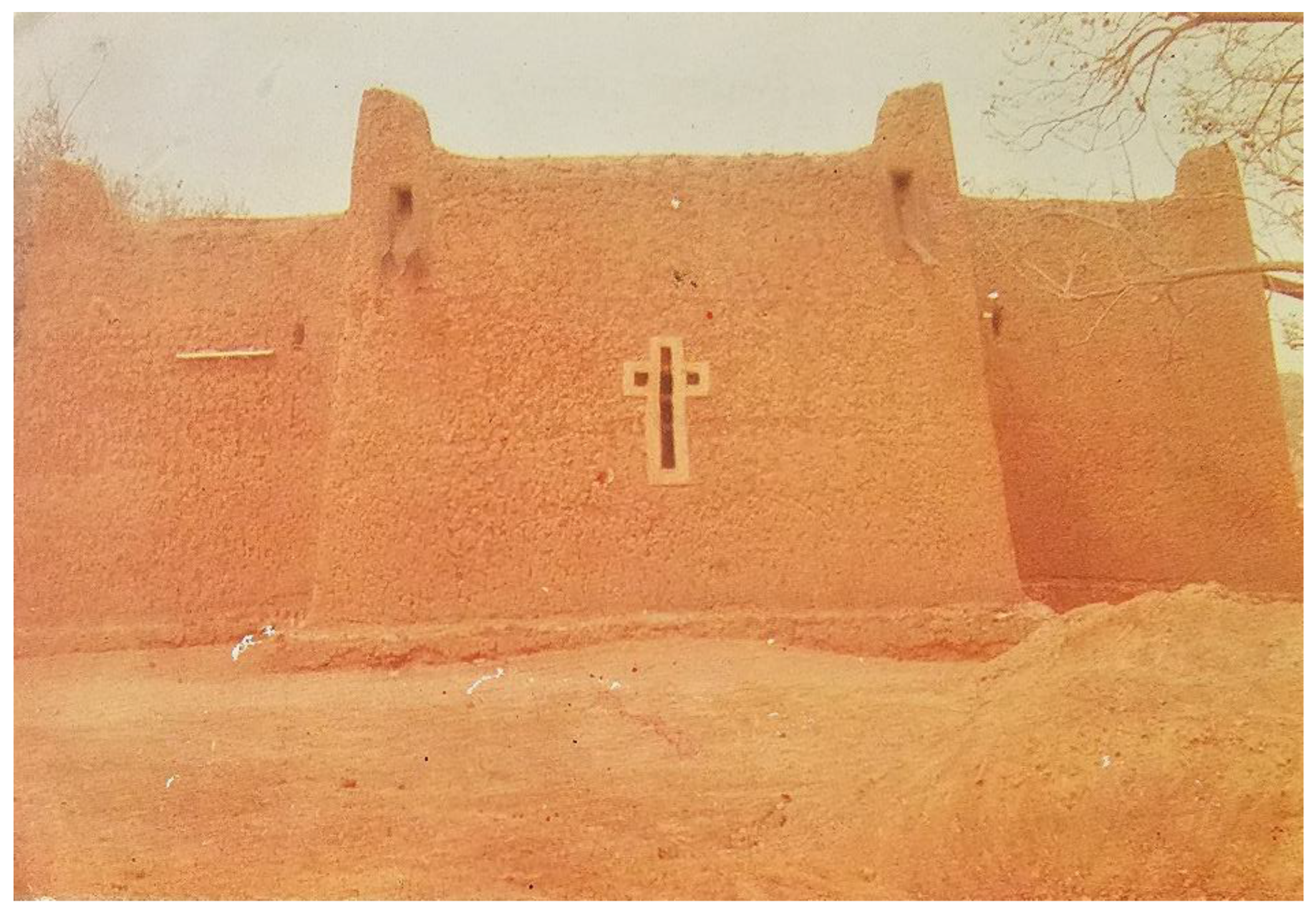

Figure 3.

South-west view of the church before the metal roof was introduced in 2003. Note the decorative “horns” (zanko) at the corners of the parapet walls. Source: Archives of St. Bartholomew Church, Wusasa [5].

Figure 3.

South-west view of the church before the metal roof was introduced in 2003. Note the decorative “horns” (zanko) at the corners of the parapet walls. Source: Archives of St. Bartholomew Church, Wusasa [5].

As the church congregation grew, a bigger church was built on the same premises in 1998. This new building is wholly built of industrial materials such as concrete, steel, and glass. The historic church was converted into a venue for children’s Sunday School gatherings and special occasions such as weddings, wedding anniversaries, and commemorative events. Thus, the building was actively in use by 2022 when the conservation project was carried out.

The 2022–2023 conservation of the historic church building involved minimal intervention and was designed with consideration for traditional building technology and methodologies, adapted to contemporary reality. The conservation activity faced the challenge of the dearth of local knowledge for earth construction techniques and overturning inappropriate practices hitherto carried out in maintaining the historic structure. The challenge of earth conservation is a recurrent one that is both technical [6] and social [7].

2. Structure and Guiding Principles Underpinning the Conservation Project in Wusasa

The achievement of architectural conservation aims to protect a building from loss, damage, unacceptable deterioration, or destruction, through an understanding of the building history, its materials and construction methods, as well as environmental and situational factors [8,9,10]. While there might be no universal recipe for architectural conservation, there are universally acceptable principles that guide national legislations governing cultural heritage conservation and, by extension, built heritage [8]. Thus, similar to most countries, there is no specific legislation on architectural conservation in Nigeria. However, relevant legislations that could be applied include the following: (i) the National Building Code’s [11] section on earth construction, which refers to the construction of new buildings; (ii) the 1992 Nigerian Urban and Regional Planning Act [12], which characterises listed buildings; and (iii) the National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM) Act of 2004, which mandates the NCMM to safeguard cultural heritage in Nigeria. However, the NCMM has no publicly available guidelines on architectural conservation in the country.

Considering the above, the conservation of the St Bartholomew Church building was guided by the principles and strategies of the Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage [13]. First, the conservation was carried out by a multidisciplinary team of national and international professionals, consisting of architects, traditional earth builders, carpenters, electrician, plumber, and specialists in earthen architecture. Second, all the conservation work, including the extension of the roof eaves and introduction of new furniture, were carried out with respect to the cultural values and the traditional character of the building. There was a deliberate effort to respect the cultural identity and setting of the building in carrying out the conservation activity. Finally, the tangible and intangible aspects of the building were investigated, documented, and considered during implementation. Table 1 and Table 2 present the alignment of the conservation programme with the guidelines of the Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage (CIAV) [13] guidelines. The integrity of the structure in itself, the use of appropriate resources and technique, and respect for the building setting were critical, in line with the CIAV Charter. It was also guided by the principle of authenticity [12], which ensured that the original character of the building was protected.

Table 1.

Framework for the conservation of the historic St Bartholomew Church building in Wusasa.

Table 2.

Summary of defects and repair interventions.

The implementation plan for this conservation activity was informed by the desire to conserve the building and revitalise traditional building techniques while sharing knowledge with a younger generation to ensure its continued survival. Further, respect for the concept of ‘learning by doing’ and the involvement of a master mason from Djenne expanded the horizons regarding shared methods and possibilities in earth construction. Against the backdrop that much of the church’s technical construction knowledge is neither documented nor written, it was critical to (i) ensure the active involvement of the descendants of the original builder of the church in the rehabilitation work and training, with the Wusasa community and church hierarchy playing an active role in linking the conservation team with this family, and (ii) carry out the conservation work during the dry season, in strict observance of the traditional building cycle. For this reason, the actual rehabilitation work and practical training sessions were carried out between October 2022 and January 2023.

3. Research and Consultation

Preliminary research included bibliographic research, telephone interviews with the members of the Wusasa community, the church hierarchy, and master builders in Zaria. These stakeholders and the NCMM were actively involved from the planning stage. The participative approach was a co-production model proffered by Rosen and Painter (2019) [14], who argue that there are limitations in Arnstein’s (1969) [15] ladder of citizen participation. In applying the co-production model to this activity, the church community was empowered to address the conservation challenge of the old church. This co-production involved various levels of decision making such as the following: introduction to the church leadership by members of the church community, facilitating access to the church building (granted by the church leadership), identification of necessary actions by the master earth builders and other artisans, the availability of resources from a grant, and the coordination role of the technical team that coordinated the co-production.

The conservation activity was introduced to stakeholders at a first meeting in April 2021. The meeting was an opportunity to gauge the interest of the church authority and its community and to obtain their approval to proceed with the conservation activity. It paved the way for subsequent formal and informal meetings with the church hierarchy and Wusasa community.

The constant communication between the community, church hierarchy, and the conservation team ensured collective decision making and community ownership of the project, which is critical for the sustainable preservation of the building. It ensured that the community and the local master builders were aware of the intervention process in its entirety, while informing and building local capacity. This will also ensure the development of good practice in earth-building conservation as the activity equipped the community to confidently carry out regular maintenance and future conservation actions.

Research was based on bibliographic sources from the church archives and oral interviews with stakeholders: the Wusasa community, the church hierarchy, and the master builders from Zaria. Photographs from the church archives and postcards (see Figure 4) were useful for understanding the building and its transformation over time. Significant timelines, such as the year of construction although documented in the literature, and the introduction of the metal roof were confirmed from the interviews.

The research also allowed the correction of the print sources, such as Dmochowski (1990) [16] which ascribed the ownership of the church building to the Roman Catholic Church, rather than to the Anglican Church. The printed works of Moughtin (1985) [4] and Dmochowski (1990) [16] provided relevant measured drawings and monochrome photographs of the old church building in their respective publications. These drawings were a useful baseline for a survey of the building’s condition.

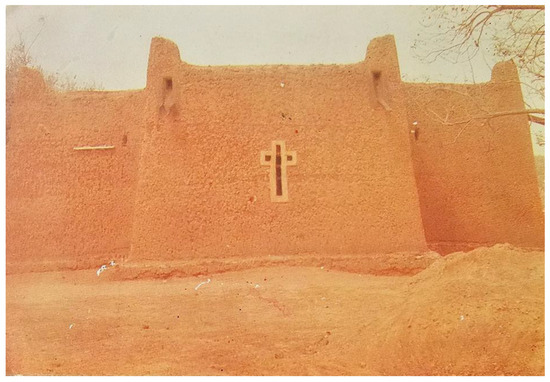

Figure 4.

Back (east) view of old St Bartholomew Church, Wusasa. Source: Postcard produced by Kaduna State Tourism Board [17].

Figure 4.

Back (east) view of old St Bartholomew Church, Wusasa. Source: Postcard produced by Kaduna State Tourism Board [17].

4. Condition Survey

The condition survey was carried out in two phases. A preliminary survey was first conducted in August 2021 to assess the state of the building and identify existing risks. The assessment identified the risks associated with the building and the site, including security risks around Wusasa and Zaria in general. The assessment was carried out using standard measuring tools and through observation. The measured survey was carried out by one of the authors, who was assisted by a volunteer within the community. Measuring tape was used to compare measurements of the floor plan (Figure 2), section, and election as they were represented in Moughtin’s book on Hausa architecture [4].

The building was still in use as of August 2021 when the preliminary survey was conducted. This revealed some areas of concern such as a pile of wood at the base of the plinth lining the base of the external walls (see Figure 5 and Figure 6). This wood pile retained moisture and introduced moisture into the walls. Similarly, the earth renders on both external and internal walls were in poor condition and needed to be renewed. The two buttresses on the northern and southern sides of the building were in critical condition and required immediate intervention as the metal roof overhang did not provide enough covering to these buttresses. The roof eaves were also leaking in several places. If the leakage continued unnoticed, there was a risk that the water would eventually fall directly on the earth roof, thus heightening the risk of its eventual collapse (see Figure 7). Although the introduction of the metal roof resulted in the loss of the zanko, it is a major factor for the survival of the building. According to oral accounts, the introduction of the metal roof addressed the following: increasing costs of annual maintenance due to the dearth of skilled artisans, the scarcity of specialised earth materials associated with rapid urbanisation, and annual increases in rainfall.

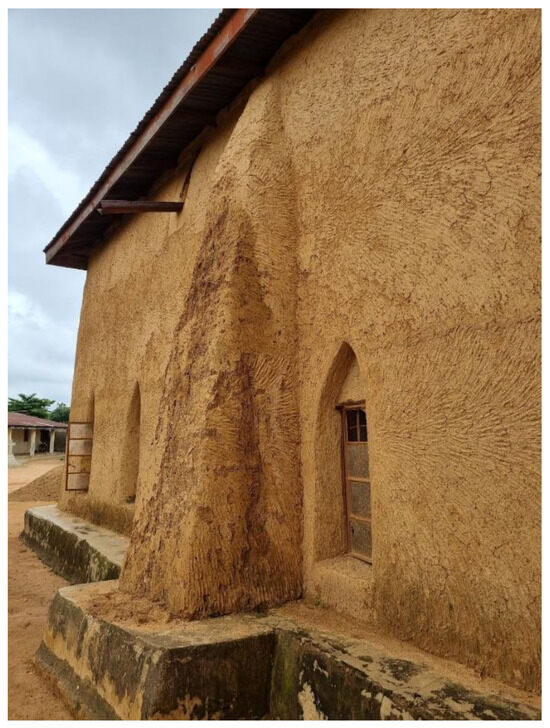

Figure 5.

The condition of the church in August 2021. Note the pile of wood next to the plinth and accelerated issues related to water damage in the earth walls (Authors).

Figure 6.

The eroded back of the church in August 2021(Authors).

Figure 7.

Accelerated erosion on the buttress due to inadequate roof overhang in August 2021 (Authors).

The preliminary condition survey was also an opportunity to map out a strategy, in collaboration with the community, regarding the general safety of the team that would be involved in the training and intervention works. Given the insecurity prevalent in the area and Kaduna State in general, the Wusasa community recommended certain security measures regarding accommodation and transportation, which were strictly adhered to, throughout the duration of the conservation activity.

In June 2022, the church authority attempted to correct the defects noted during the preliminary condition survey of August 2021. It consisted of applying a mixture of earth and cement as external render on the earth walls. However, this intervention was inappropriate. The timing of this external rendering was also inappropriate. It was carried out during the rainy season, contrary to traditional practice. The incompatible cement-stabilised external earth render was already being eroded by rain at the time when the final condition survey was conducted in August 2022. During this same period, the church authority embarked on some improvement works in the church compound, and this included the introduction of concrete paving throughout the church compound, including the area around the historic church building (Figure 8). Furthermore, painting of the interior with industrial paint has commenced by the church when the conservation team arrived on site in August 2022 as shown in Figure 9. The church authority was advised to discontinue the painting and laying of the concrete paving around the old church building to avoid condensation in the interior of the earth building, which would have brought devastating consequences over time if left unchecked.

Figure 8.

The historic St Bartholomew Church after the application of the cementitious render and during external work by the church (August 2023) (Authors).

Figure 9.

The church interior before the start of the rehabilitation work in December 2022. The team arrived whilst the church was applying inappropriate paint on the wall instead of the traditional earth-based slurry finish (Authors).

The final condition survey took place in August 2022. August is the peak of the rainy season in Zaria. This was a deliberate choice, as it provided the opportunity to assess the effects of rainwater on the building. The major concern associated with rain observed during this visit was the direct impact of rainwater falling directly on the wall buttresses, causing their accelerated erosion (Figure 10 and Figure 11). The condition survey established the basis for the remediation plan, cost, and plan for the next phase of the conservation actions.

Figure 10.

Condition of one of the buttresses in August 2021 [Authors].

Figure 11.

Same buttress shown in Figure 10 above, have been rendered by the church with render composed of earth and cement mix in June 2023. This picture was taken in August 2023 during the second condition survey (Authors).

Other deterioration observed in the historic church building during the final condition survey was largely due to inappropriate interventions on the earth walls and ageing building components. In addition, other inappropriate interventions were taken by the church community, such as the application of industrial-grade white paint to the internal wall surfaces (Figure 12); the composition of this paint includes synthetic dye compounds that are incompatible with the original earthen material. Within the church building, the electrical fittings and furniture were dilapidated and required replacement and refurbishment, respectively (Figure 13). The earthen benches were cracked (Figure 14); the electrical conduits had sagged or were completely detached from the wall; some of the window and door frames were either missing or partially broken; two of the door locks were missing; and some window glass panes were similarly either broken or missing.

Figure 12.

Industrial paint being applied to the interior by the church. This was stopped by the conservation team when they arrived on site in August 2022.

Figure 13.

Sagging electrical conduit pipes and damaged fittings.

Figure 14.

Worn-out benches (Authors).

5. Remediation Practical Actions: Rehabilitation, Repair, and Refurbishment

With the completion of the condition surveys, four critical conservation actions were planned and carried out. The first was the removal of all inappropriate and incompatible materials on the earth walls and their replacement with the appropriate, earth-compatible, materials. Thus, the cement-stabilised earth render applied to external walls and the whitewash applied on the internal surfaces of the earth walls were removed. The corrugated metal roof and electrical fittings were removed and replaced. The earthen seats were repaired, and the edges were capped with timber to protect the edges from frictional wear and erosion. The third action consisted of improvements to the immediate building surrounding, particularly removing the impermeable concrete pavers and replacing it with gravels and a 105 m long drainage system to improve permeability around the base of the earthen walls. The drainage was connected to the main drainage line just outside the church compound. Finally, the worn-out furniture fabrics and upholstery were replaced. None of the frames and glass panes of the 4 doors and 16 windows in the building were intact. Thus, the frames were refurbished and glass panes were replaced depending on need.

The community played a crucial role in identifying the places from which the relevant earth-building materials could be obtained to carry out the planned remedial actions on the earth walls. Due to rapid urbanisation in Wusasa and its environs, the sources of earth-building materials are now further away from the church location. In addition to the main material (earth), other materials such as straw, makuba (pods of locust bean), karo (gum Arabic), buntun shinkafa (rice husk), buzai (smectite clayey soil rich in mica), and katsi (kaolinite clay soil) were sourced locally. Each of these materials enhances the intrinsic properties of earth. Makuba is a stabilising agent that increases plasticity and improves the workability and moisture-holding capacity of earth [16]. The straw and buntun shinkafa (rice husk) reduce the shrinkage and cracks on the earth render. In the past, these materials were transported to the building site either by humans or on the back of donkeys. However, this is no longer the case. For the purpose of the conservation activity, the earth for the external render was sourced from borrow pits near a village called Zangon Aya, approximately 20 km from Wusasa. Similarly, katsi and buzai were sourced from Aba (18 km from Wusasa) and Dumbi (40 km from Wusasa), respectively. The master mason (Katukan Magina) identified these locations, which were unknown to the Wusasa community. The materials are not sold in commercial quantities and had to be pre-ordered to obtain the quantities required for the project.

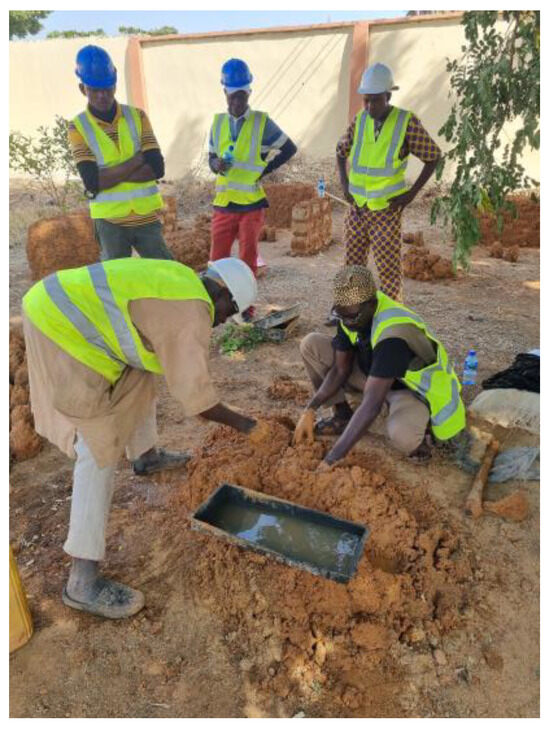

The rehabilitation work started with the preparation of materials at the end of the wet season in October and continued until December 2022. Earth samples were collected and tested on site, using the cigar-and-bottle test to determine the plasticity and particle size distribution, respectively. The first earth mixing was carried out in October 2022 (Figure 15). The earth was mixed with straw, plant additive (makuba), and water. The ratio of the mix was approximately 8 parts of earth to 1 part of makuba and 1 part of straw. This mixture was turned over twice, once in November and again in December 2022, and fresh solutions of makuba and water were added on each occasion.

Figure 15.

Earth mixing in October 2022. The white powder is makuba (Authors).

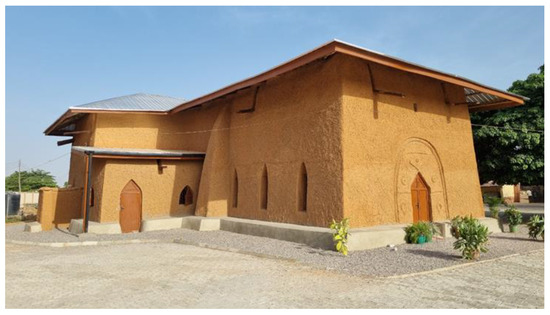

A systematic approach was deployed during the rehabilitation of the old church building. The refurbishment of the furniture and the external work were carried out towards the end of the rainy season in September 2022, before other work on the interior of the building, as furniture refurbishment was not dependent on weather conditions. Thereafter, external work started with the removal of the corroded metal roof and replacing it with a non-corroding aluminium roof with long overhangs that protect the buttresses and the base plinth (dakali) as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

External view of the church after rehabilitation (April 2023) (Authors).

The earth roof underneath the corroded metal roof was inspected. It was structurally sound but presented some superficial cracks on its soffit. The cracks were repaired by hacking into the affected areas to remove the weakened earthen material and replacing it with like material and applying three coats of earth plaster. The first coat consisted of a mixture of soil stabilised with makuba that was applied in its plastic state. The second coat was applied the following day in order to fill up visible cracks on the newly applied earth render. The third and final coat was applied the following week when the entire interior of the church was given a finish coating of traditional earth-based paint consisting of katsi, buzai, and karo that were mixed with water.

On the external wall surfaces, the existing external cement-stabilised earth was removed and replaced with the fermented earth mixture prepared between October and December 2022. New render was also applied to the wall plinth (dakali), after the old one was removed [4]. Similarly, broken metal frames of the windows and doors were repaired and painted before the replacement of missing and broken glazing. The final stage of external work was the landscaping around the old church. This consisted of creating underground French drains and inspection chambers, covered with gravel. Concrete kerbs were laid at the edges of the loose gravel, to keep them in place.

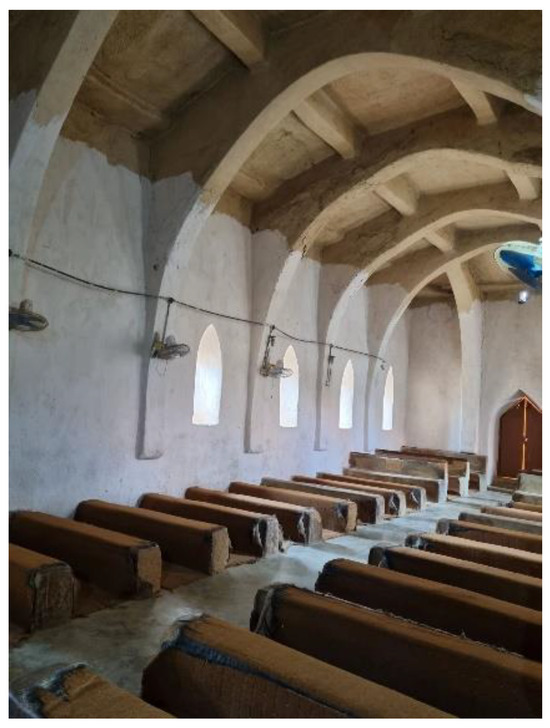

The interior wall surfaces were rendered with solutions of fine earth, buzai, katsi, karo, and water. The buzai was sieved to separate the required shiny mica from the clayey soil. The katsi and karo act as a glue, while the mica particles give the interior a shiny grey appearance (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

The interior of the church after rehabilitation in January 2023. (Authors).

The electrical work consisted of straightening the alignment of the sagging electrical conduit pipes along the walls and arches. Seventeen new wall fans were also installed to replace the damaged or missing ones, in addition to electrical sockets, switches, and wall brackets.

New render was applied on the earth seats, and new seat covers which serve as additional protection to the seats were introduced (Figure 17). The church community requested for the floor of the church to be covered with carpeting. Both the seat covers and carpet were not part of the original features of the building. However, they were introduced as additional protection to the seats and floor, respectively. Both actions are reversible and pose no danger to the original fabric of the building. Table 2 presents a summary of recorded defects, the causes of the defects, and the remedial measures taken during the rehabilitation of the church.

6. Capacity Building

Capacity building was carried out in two phases. Sixteen people were trained. Eight of them were selected by the church community, represented by its leadership, while the other eight were professionals with interest and experience in earth construction from other towns and cities in Nigeria, some of whom were members of ICOMOS-Nigeria.

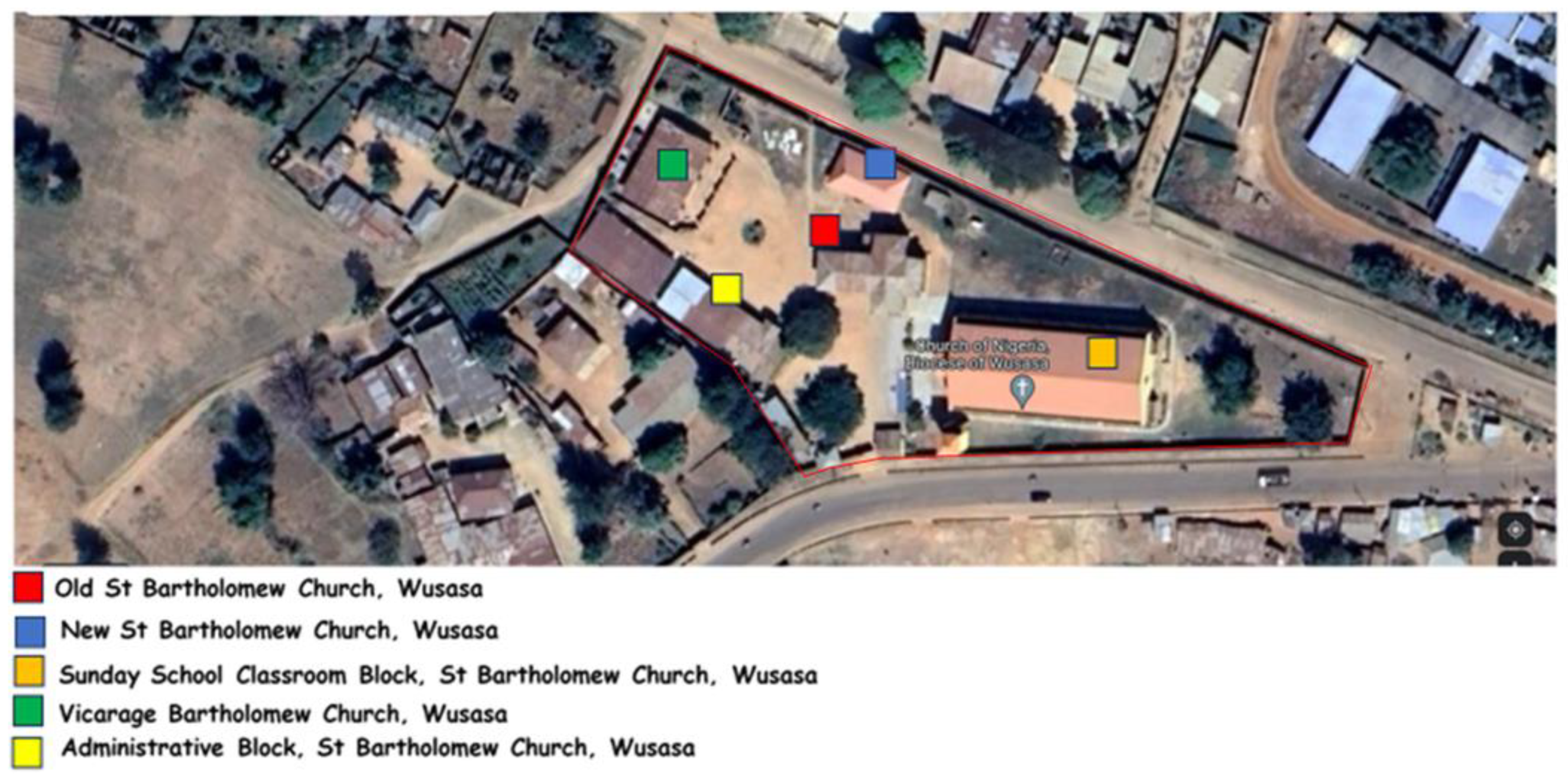

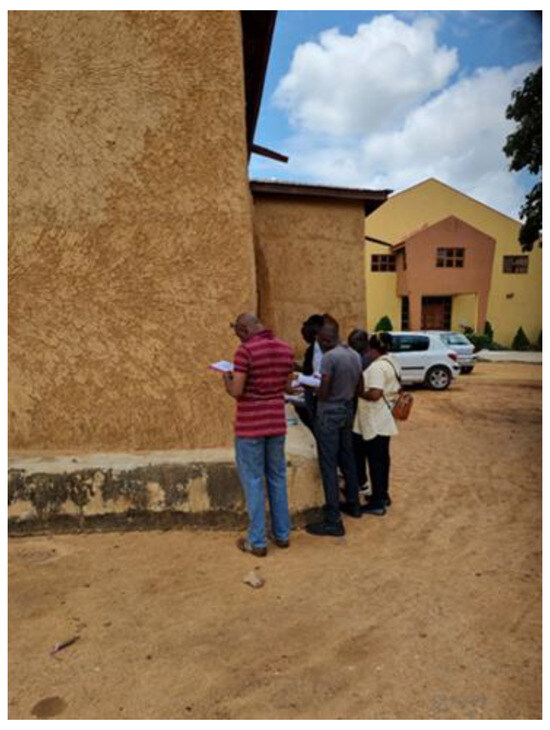

The first phase of the training took place from 20 to 24 August 2022. The first day consisted of theoretical sessions, focussing on Nigerian traditional earth construction and conservation, condition survey techniques, and building inventory techniques. The final two days involved the application of the theoretical knowledge accrued, and the trainees conducted a condition survey of the historic church building as well as an inventory of earth buildings in Wusasa (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Trainees carrying out condition survey in August 2022. (Authors).

The second phase of capacity building was hands-on and took place in December 2023 simultaneously with the rehabilitation work. A 9 m2 multi-purpose building was constructed specifically for the demonstration and training purposes, instead of using the historic old church, to avoid damage to the historic building. This phase involved the participation of master mason Boubacar Kouroumanse of the Djenne barey-ton or mason’s guild [4], who shared his earth construction experience at Djenne (Figure 19). He demonstrated various rendering techniques from Djenne, Mali, which lies in a similar geographic zone as Wusasa, on the walls of a test building prepared for the purpose. The trainees and builders from Zaria recognised the additives he brought from Mali with which he carried out his demonstrations. It was also an opportunity for him to exchange knowledge with the Katukan Magina of Zaria who led the earth-wall repair team. The trainees in this second phase were the same trainees as in the first phase in addition to three new trainees from Benin City in southern Nigeria. This alternative provided the trainees the opportunity to learn traditional brick moulding, earth construction, and rendering, whilst observing the rehabilitation work by the traditional artisans.

Figure 19.

Katukan Magina, the chief builder of Zaria (left) and Boubacar Kouroumanse (right) demonstrating soil-mixing techniques for different earth finishes.

The impact of both trainings is already felt at local and national levels. Locally, some of the trainees from Wusasa participated in the rehabilitation of the Sarkin Wusasa Palace, which is also a building made of earth and built around the same time as the church. The rehabilitation was carried out in February 2024. Similarly, another training workshop on Hausa earthen architecture was conducted in Zaria in January 2024 by some of the professionals that were involved in the two trainings.

7. Sustainability through Dissemination

The dissemination of the results of the conservation of the historic St Bartholomew Church building was carried out through a permanent exhibition that showcased the entire conservation project and as part of the handing-over ceremony in April 2023. The exhibition was prepared and installed with the support of the church and now forms a part of the church’s archives. Similarly, a maintenance manual was prepared and presented to the church and the community head (Sarki) of Wusasa. This manual contains best practices employed in the conservation of the church and a directory of sources of materials and the contacts of the artisans involved in the project. This document will be critical for maintenance and continuous preservation of the building.

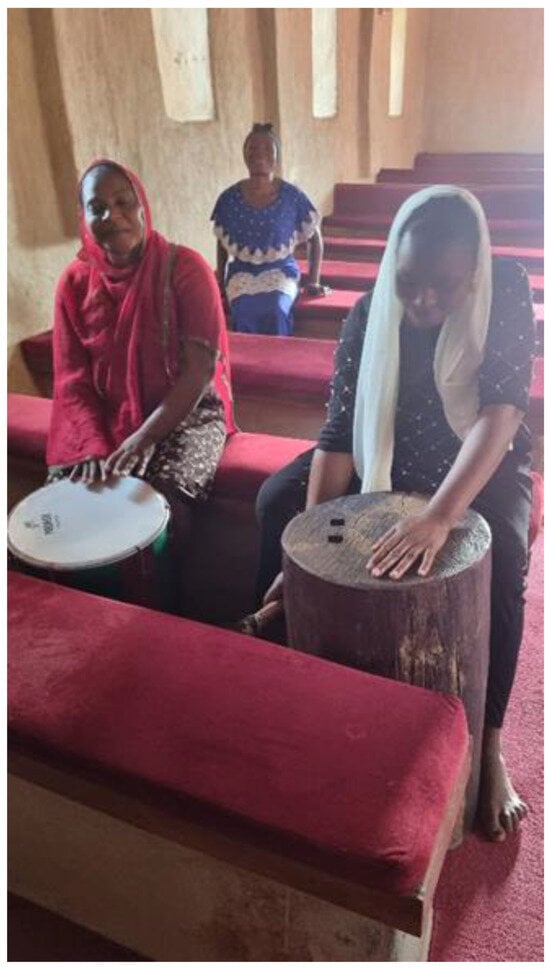

The handover and exhibition in April 2023 also provided the opportunity to evaluate the building 3 months after completion of the rehabilitation. The rehabilitated building was in excellent condition and normal activities such as choir practice, small group meetings, and Sunday School have resumed. Figure 20 shows the church choir practising inside the church building and traditional musical instruments. The conservation actions encouraged the church community to refurbish its old musical instruments such as the old church organ and traditional musical instruments (kachau-kachau, tumburunbuntu, and kuge) with the aim of including them as part of the display in the old church building. These traditional music instruments are unique to the ethnic groups in northern Nigeria. This sense of ownership is exemplary and was achieved as a result of the inclusive approach adopted throughout the project. The community now sees the rehabilitated church as a piece of history worth preserving rather than just any building.

Figure 20.

The church in use after conservation.

8. Conclusions

The conservation of the old St Bartholomew Church building was conceived with the aim of carrying out an intervention to safeguard it in a manner that is sympathetic to its setting and to bridge the knowledge gap in earthen architectural conservation in Nigeria and similar contexts in Africa and around the world. The practice of earth construction worldwide can be boosted by the dissemination of good practices and principles which can be adapted to context. The general principles, as adopted in the St Bartholomew example, consists of a systematic approach that recognises traditional practices, including seasonal earth construction practices, use of local resources (skilled labour, materials, and technology), capacity building, and systematic documentation and dissemination (exhibition). This approach ensures not only the success of the conservation activity but can also boost a sense of community ownership and participation throughout the activity, from the conceptual stage to handover to the community. This in turn enhances community use, as demonstrated by the post-conservation occupancy of the restored historic St Bartholomew Church building and is an assurance of the sustainable preservation of the building. The maintenance manual provides additional support to the community’s independence to carry out periodic maintenance and repair and is a good practice that can be replicated elsewhere. Similarly, the materials included in the permanent exhibition provide visual and written records of this conservation project that will be useful for the future conservation of the building. The application of traditional construction techniques in contemporary times enhances public knowledge of the opportunities that earth offers for current construction needs. Observation over time will also be necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of the actions carried out.

In all, the exercise was a demonstration of the very real challenges faced by earth construction even in regions where there is a strong tradition of earth construction. The exercise also highlighted the need for strong community engagement to ensure buy-in, continuity, and sustainability of earth construction practices. It flagged the need for continuous training at all levels.

Author Contributions

T.A.S. and I.O. contributed to all aspects of the conservation project and in writing this article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The conservation of the old St Bartholomew Church building in Wusasa was made possible by the generous financial support of the Gerda Henkel Stiftung. This funding made it possible for Theophilus Shittu to travel and oversee the activities reported upon in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during this study are available from the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the physical and intellectual contributions of Malam Yahaya Mohammed (Katukan Magina) to the project and this article. He kindly shared his professional knowledge of earthen architecture through interviews; demonstrations during the training workshops; and the masonry work during the actual rehabilitation work. The authors would also like to express their deep appreciation to the Wusasa Anglican Diocese led by the Archbishop of Wusasa, His Lordship Buba Lamido, and particularly the Vicar, Venerable Davou Zang; the Sarkin Wusasa, His Highness Engr Isiyaku Danlami Yusufu; Malam Jamo Julde; and the elders of Wusasa, particularly Malam Haliru Yusuf and Capt. Jonathan Ibrahim (Garkuwan Wusasa) for their support and intellectual contributions to the project. Paul Audu and Omar Peter Isiyaku provided us with archival pictures of the church prior to the introduction of the metal roof.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Idowu-Fearon, J.A. Reconciling a Religiously Divided Community Through Inter-Faith Dialogue: An Experiment in Wusasa—Zaria of Nigeria; A Ministry Report Presented to the Faculty of Hartford Seminary in Partial Fulfilment of Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Ministry (D.Min.); ProQuest LLC: Hartford, CT, USA, 1993; pp. 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W.R.S. Reflections of a Pioneer; Church Missionary Society (CMS): London, UK; The Camelot Press, Ltd.: Chicago, IL, USA, 1936; pp. 215–216. [Google Scholar]

- St Bartholomew Church. Thanksgiving Service Programme: Coronation of Village head (Sarki) of Wusasa, His Highness Engr Isiyaku Danlami Yusufu; St Bartholomew Anglican Cathedral: Wusasa, Zaria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moughtin, J.C. Hausa Architecture; Ethnographica Ltd.: London, UK, 1985; pp. 114–115. [Google Scholar]

- Abdu, P. Old Picture of the St Bartholomew Church, Wusasa before the Intervention in 2003; St Bartholomew Church: Zaria, Nigeria, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, M.; Guerrero, L. Conservation of Earthen Building Materials. In The Encyclopedia of Archaeological Sciences; López Varela, S.L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, J.; Barada, J. The technical and the social: Challenges in the conservation of earthen vernacular architecture in a changing world (Jujuy, Argentina). Built Herit. 2021, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbaşlı, A. Architectural Conservation; Willey Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, J. Conservation of Earth Structures; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, N.L. An Introduction to Architectural Conservation: Philosophy, Legislation and Practice; RIBA Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2014; pp. 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Republic of Nigeria. National Building Code; LexisNexis Butterworths: Sandton, South Africa, 2006; pp. 348–354. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Government of Nigeria. Nigerian Urban and Regional Planning Act. 1992. Available online: https://archive.gazettes.africa/archive/ng/2018/ng-government-gazette-dated-2018-01-02-no-8.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- ICOMOS. Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage. 1999. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/participer/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards?start=18 (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Rosen, J.; Painter, G. From Citizen Control to Co-Production. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2019, 85, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmochowski, Z.R. Introduction to Nigerian Traditional Architecture; London and Lagos, Ethnographica in Association with the National Commission for Museum and Monuments (NCMM): Abuja, Nigeria, 1990; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kaduna State Tourism Board. Nigeria. St Bartholomew’s Church Zaria; A postcard printed in the 1990s; Kaduna State Tourism Board: Kaduna, Nigeria, 1990. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).