Green Skepticism? How Do Chinese College Students Feel about Green Retrofitting of College Sports Stadiums?

Abstract

1. Introduction

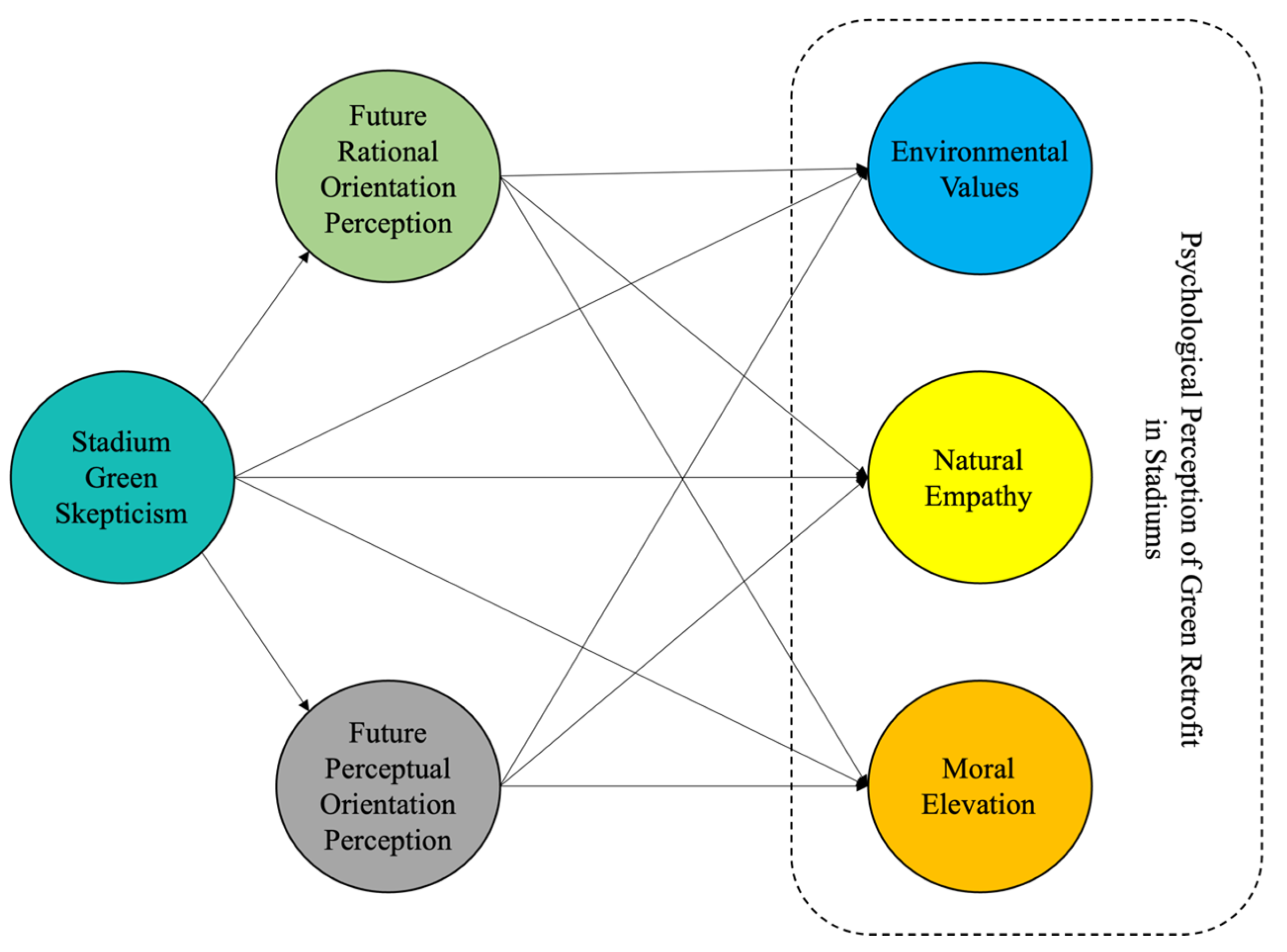

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Green Skepticism and Psychological Perceptions of Green Renovation of Stadiums

2.2. The Mediating Role of Future Rational Orientation Perception

2.3. The Mediating Role of Future Perceptual Orientation Perception

3. Methods

3.1. Subjects

3.2. Measurement of Variables

3.3. Questionnaire Distribution

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias Test

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis of Variables

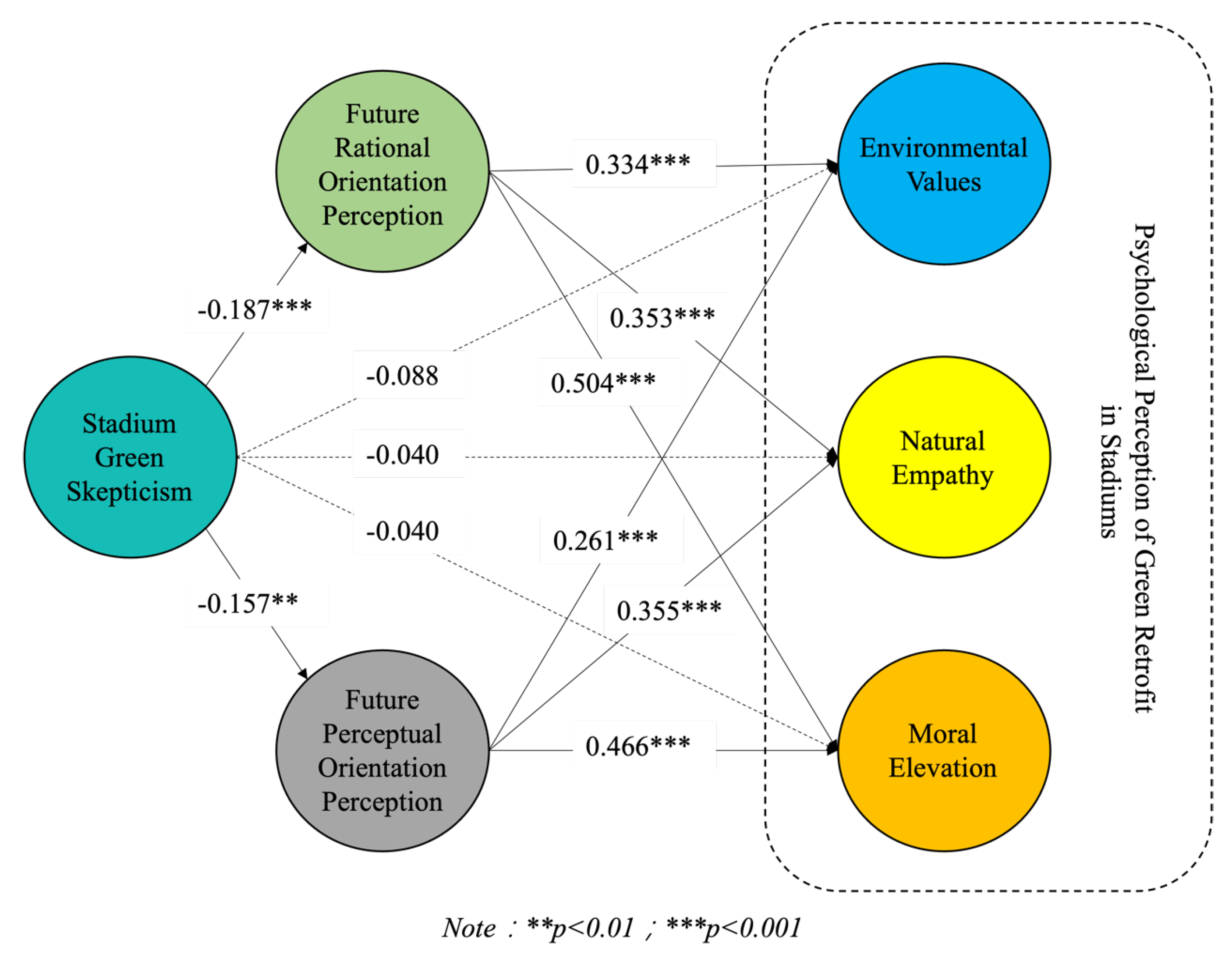

4.3. Parallel Mediation Effect Tests

5. Discussion and Analysis

5.1. Current Status of College Students’ Green Skepticism, Future Orientation of Green Retrofitting of Stadiums, and Psychological Perceptions of Green Retrofitting of Stadiums

5.2. Influence of College Students’ Green Skepticism on Psychological Perceptions of Green Renovation of Stadiums

5.3. Parallel Mediation of Future Rational Orientation Perception, Future Perceptual Orientation Perception

6. Conclusions and Shortcomings

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Shortcomings and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| Variant | Dimension (Math.) | Subject | Score |

| Stadium green skepticism | Green skepticism | I’m not a big believer in most of the environmental and safety claims on some stadium green renovation package labels or advertising messages. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree |

| I believe that most of the environmental information related to the green renovation of stadiums has been publicized to mislead the public and gain other benefits rather than for the true cause of green development. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | ||

| I am conservative or skeptical about the true environmental results that can be achieved after a green renovation of a stadium. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | ||

| I believe that the green renovation process of some stadiums has been described or publicized with misleading words, in order to exaggerate their own green features. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | ||

| Future orientation of green retrofit of stadiums | Future rational orientation perception | When I hear about a green renovation of a stadium, I look out for information about the quality testing, environmental monitoring, and parametric performance indicators of that green renovation project. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree |

| When I hear about green retrofitting stadiums, I focus on what green value can be delivered by greening stadiums. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | ||

| When I hear about the green retrofit of stadiums, I will pay more attention to the government’s environmental plans or programs. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | ||

| Future perceptual orientation perception | When I hear about the green renovation of stadiums, I sketch in my mind what the renovated venues will look like. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | |

| When I hear about the green retrofit of stadiums, I’ll have something to look forward to. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | ||

| When I hear about the green retrofit of stadiums, I will have more confidence in the upgrading of the environmental cause. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | ||

| Psychological perception of green retrofit in stadiums | Environmental values | For the survival and growth of future generations and the preservation of urban resources, I believe that green renovation and upgrading of stadiums and other buildings is very necessary. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree |

| I think if we don’t green our stadiums, we’re bound to have insurmountable environmental problems in the future. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | ||

| I believe that environmental pollution problems in one place can affect the health of residents in other areas and even globally. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | ||

| I believe that the green retrofit of stadiums is a practice that respects nature and harmonizes with the natural environment. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | ||

| Natural empathy | I think that although people have the ability to modify nature, they should also follow the laws of nature. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | |

| I believe that people’s participation in sports or watching services needs to be based on the preservation of the natural environment. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | ||

| I believe that greening stadiums is a sign of the harmonious development of man and nature. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | ||

| Sense of moral elevation | After learning about the advantages of greening stadiums, I will try to increase and persuade my friends and family to do more pro-environmental behaviors in the future as well. | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | |

| With the general trend of low carbon emission reduction, I hope I can become a more environmentally conscious person too! | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree | ||

| Would a green renovation of stadiums lead me to believe that the world is a more stable and better place? | 1. strongly disagree 2. somewhat disagree 3. generally agree 4. somewhat agree 5. strongly agree |

Appendix B

| Group (Mean ± Standard Deviation) | t (Decision Value) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Grouping (n = 61) | High Subgroup (n = 61) | |||

| GS1 | 2.69 ± 0.92 | 4.33 ± 0.79 | 10.541 | 0.000 ** |

| GS2 | 2.59 ± 0.88 | 4.33 ± 0.72 | 11.888 | 0.000 ** |

| GS3 | 2.52 ± 0.87 | 4.31 ± 0.81 | 11.774 | 0.000 ** |

| GS4 | 2.72 ± 1.02 | 4.15 ± 0.81 | 8.546 | 0.000 ** |

| FROP1 | 2.74 ± 0.87 | 4.15 ± 0.93 | 8.639 | 0.000 ** |

| FROP2 | 2.54 ± 0.96 | 4.21 ± 0.99 | 9.501 | 0.000 ** |

| FROP3 | 2.48 ± 0.94 | 4.20 ± 0.96 | 9.981 | 0.000 ** |

| FPOP1 | 2.84 ± 0.97 | 4.08 ± 0.88 | 7.429 | 0.000 ** |

| FPOP2 | 2.72 ± 0.93 | 4.00 ± 0.84 | 7.968 | 0.000 ** |

| FPOP3 | 2.90 ± 1.14 | 4.31 ± 0.81 | 7.902 | 0.000 ** |

| EV1 | 2.61 ± 0.86 | 4.18 ± 0.81 | 10.415 | 0.000 ** |

| EV2 | 2.59 ± 0.84 | 4.30 ± 0.67 | 12.377 | 0.000 ** |

| EV3 | 2.61 ± 0.94 | 4.21 ± 0.82 | 10.09 | 0.000 ** |

| EV4 | 2.66 ± 0.87 | 4.20 ± 0.87 | 9.751 | 0.000 ** |

| NE1 | 2.70 ± 0.97 | 4.10 ± 1.01 | 7.757 | 0.000 ** |

| NE2 | 2.70 ± 0.86 | 3.93 ± 1.14 | 6.723 | 0.000 ** |

| NE3 | 2.77 ± 0.99 | 3.93 ± 1.15 | 5.983 | 0.000 ** |

| ME1 | 2.49 ± 0.94 | 3.98 ± 0.99 | 8.519 | 0.000 ** |

| ME2 | 2.59 ± 0.84 | 4.07 ± 1.03 | 8.65 | 0.000 ** |

| ME3 | 2.52 ± 0.79 | 4.20 ± 1.03 | 10.073 | 0.000 ** |

| Sports Event | Decision Value (CR) | p-Value (CR) | Correlation with Scale Total Score | p-Value (Correlation with Scale Total Score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GS1 | 10.541 ** | 0.000 | 0.596 ** | 0.000 |

| GS2 | 11.888 ** | 0.000 | 0.640 ** | 0.000 |

| GS3 | 11.774 ** | 0.000 | 0.628 ** | 0.000 |

| GS4 | 8.546 ** | 0.000 | 0.581 ** | 0.000 |

| FROP1 | 8.639 ** | 0.000 | 0.559 ** | 0.000 |

| FROP2 | 9.501 ** | 0.000 | 0.616 ** | 0.000 |

| FROP3 | 9.981 ** | 0.000 | 0.638 ** | 0.000 |

| FPOP1 | 7.429 ** | 0.000 | 0.555 ** | 0.000 |

| FPOP2 | 7.968 ** | 0.000 | 0.583 ** | 0.000 |

| FPOP3 | 7.902 ** | 0.000 | 0.614 ** | 0.000 |

| EV1 | 10.415 ** | 0.000 | 0.548 ** | 0.000 |

| EV2 | 12.377 ** | 0.000 | 0.592 ** | 0.000 |

| EV3 | 10.090 ** | 0.000 | 0.637 ** | 0.000 |

| EV4 | 9.751 ** | 0.000 | 0.577 ** | 0.000 |

| NE1 | 7.757 ** | 0.000 | 0.584 ** | 0.000 |

| NE2 | 6.723 ** | 0.000 | 0.529 ** | 0.000 |

| NE3 | 5.983 ** | 0.000 | 0.518 ** | 0.000 |

| ME1 | 8.519 ** | 0.000 | 0.599 ** | 0.000 |

| ME2 | 8.650 ** | 0.000 | 0.589 ** | 0.000 |

| ME3 | 10.073 ** | 0.000 | 0.612 ** | 0.000 |

| Factor | Mean Variance Extraction AVE Value | Combined Reliability CR |

|---|---|---|

| Green skepticism | 0.635 | 0.874 |

| Future rational orientation perception | 0.636 | 0.84 |

| Future perceptual orientation perception | 0.532 | 0.773 |

| Environmental values | 0.654 | 0.883 |

| Natural empathy | 0.623 | 0.832 |

| Moral elevation | 0.634 | 0.838 |

| Green Skepticism | Future Rational Orientation Perception | Future Perceptual Orientation Perception | Environmental Values | Natural Empathy | Moral Elevation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| green skepticism | 0.797 | |||||

| future rationality oriented cognition | 0.501 | 0.798 | ||||

| futuristic oriented cognition | 0.568 | 0.481 | 0.730 | |||

| environmental values | 0.514 | 0.468 | 0.465 | 0.809 | ||

| natural empathy | 0.380 | 0.428 | 0.420 | 0.436 | 0.789 | |

| moral elevation | 0.509 | 0.366 | 0.519 | 0.428 | 0.380 | 0.796 |

References

- Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Zhang, T. Urbanization, economic growth, and environmental pollution: Partial differential analysis based on the spatial Durbin model. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2019, 30, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellstrom, T.; Lodh, M.; McMichael, T.; Ranmuthugala, G.; Shrestha, R.; Kingsland, S. Air and water pollution: Burden and strategies for control. In Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries, 2nd ed.; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, L.; Wang, S. Can industrial agglomeration affect biodiversity loss? Energy Environ. 2023, 0958305X231200575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, V.N. Impact of droughts on industrial emissions into surface waters. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 42806–42814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, W.; Borlace, S.; Lengaigne, M.; Van Rensch, P.; Collins, M.; Vecchi, G.; Timmermann, A.; Santoso, A.; McPhaden, M.J.; Wu, L.; et al. Increasing frequency of extreme El Niño events due to greenhouse warming. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.E.; Autry, C.W.; Mollenkopf, D.A.; Thornton, L.M. A natural resource scarcity typology: Theoretical foundations and strategic implications for supply chain management. J. Bus. Logist. 2012, 33, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, U.d.P.; Arbex, M.A.; Braga, A.L.F.; Mizutani, R.F.; Cançado, J.E.D.; Terra-Filho, M.; Chatkin, J.M. Environmental air pollution: Respiratory effects. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2021, 47, e20200267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, L. Green structural transformation. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 877–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.Z.; Zhu, Z.H.; Yang, E.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.H. Assessment and management of air emissions and environmental impacts from the construction industry. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 61, 2421–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheriyan, D.; Choi, J.h. A review of research on particulate matter pollution in the construction industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kodmany, K. Green retrofitting skyscrapers: A review. Buildings 2014, 4, 683–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, R.B.; Foo, K.S.; Zin, R.M.; Yang, J.; Zolfagharian, S. Potential retrofitting of existing campus buildings to green buildings. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 178, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, S.; Shen, G.Q. A critical review of green retrofit design. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Construction and Real Estate Management 2013 (ICCREM 2013): Construction and Operation in the Context of Sustainability, Karlsruhe, Germany, 10–11 October 2013; pp. 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Triantafyllidis, S.; Ries, R.J.; Kaplanidou, K. Carbon dioxide emissions of spectators’ transportation in collegiate sporting events: Comparing on-campus and off-campus stadium locations. Sustainability 2018, 10, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N.; Yan, G.; McLeod, C. The Impact of Sporting Events on Air Pollution: An Empirical Examination of National Football League Games. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szasz, A. Shopping Our Way to Safety: How We Changed from Protecting the Environment to Protecting Ourselves; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wergeland, E.S.; Hognestad, H.K. Reusing stadiums for a greener future: The circular design potential of football architecture. Front. Sport. Act. Living 2021, 3, 692632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozma, G.; Radics, Z.; Teperics, K. The Role of Sports Facilities in the Regeneration of Green Areas of Cities in Historial View: The Case Study of Great Forest Stadium in Debrecen, Hungary. Buildings 2022, 12, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Eroǧlu, D.; Ellen, P.S. The development and testing of a measure of skepticism toward environmental claims in marketers’ communications. J. Consum. Aff. 1998, 32, 30–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastak, M.; Olson, J.C. Assessing the role of brand-related cognitive responses as mediators of communication effects on cognitive structure. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 15, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermiller, C.; Spangenberg, E.; MacLachlan, D.L. Ad skepticism: The consequences of disbelief. J. Advert. 2005, 34, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parguel, B.; Benoît-Moreau, F.; Larceneux, F. How sustainability ratings might deter ‘greenwashing’: A closer look at ethical corporate communication. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Paço, A.M.F.; Reis, R. Factors affecting skepticism toward green advertising. In Green Advertising and the Reluctant Consumer; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Li, X.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, G. Building green retrofit in China: Policies, barriers and recommendations. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.H.; Chang, C.T.; Lee, Y.K. Linking hedonic and utilitarian shopping values to consumer skepticism and green consumption: The roles of environmental involvement and locus of control. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 14, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, S.; Grappi, S.; Bagozzi, R.P. Corporate socially responsible initiatives and their effects on consumption of green products. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.K.; Balaji, M. Linking green skepticism to green purchase behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiong, O. A brief introduction to perception. Stud. Lit. Lang. 2017, 15, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.; Scheier, M. On the Self-Regulation of Behavior; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, A. Creating Shareholder Value: A Guide for Managers and Investors; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jahdi, K.S.; Acikdilli, G. Marketing communications and corporate social responsibility (CSR): Marriage of convenience or shotgun wedding? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrus, G.; Passafaro, P.; Bonnes, M. Emotions, habits and rational choices in ecological behaviours: The case of recycling and use of public transportation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansla, A.; Gamble, A.; Juliusson, A.; Gärling, T. Psychological determinants of attitude towards and willingness to pay for green electricity. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Kumar, M. “Yes, but this other one looks better/works better”: How do consumers respond to trade-offs between sustainability and other valued attributes? J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinath, B.; Stiensmeier-Pelster, J. Goal orientation and achievement: The role of ability self-concept and failure perception. Learn. Instr. 2003, 13, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubić, A.; Abraham, A. Neurocognitive bases of future oriented cognition. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 21, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, L.; Graham, S.; O’brien, L.; Woolard, J.; Cauffman, E.; Banich, M. Age differences in future orientation and delay discounting. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stren, P. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behaviour. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Yang, Z.; Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W.; Cao, T.K. Greenwash and green purchase intention: The mediating role of green skepticism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Skarmeas, D. Gray shades of green: Causes and consequences of green skepticism. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshbakht, M.; Gou, Z.; Xie, X.; He, B.; Darko, A. Green building occupant satisfaction: Evidence from the Australian higher education sector. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekinezhad, F.; Courtney, P.; bin Lamit, H.; Vigani, M. Investigating the mental health impacts of university campus green space through perceived sensory dimensions and the mediation effects of perceived restorativeness on restoration experience. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 578241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, W.S. Social accountability and corporate greenwashing. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 43, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, S.P.M. Teaching approaches in geography and students’ environmental attitudes. Environmentalist 2004, 24, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimberg, L.K. The Measurement of Future Time Perspective; Vanderbilt University: Nashville, TN, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H.; Yang, C.C. Conceptualizing and measuring environmentally responsible behaviors from the perspective of community-based tourists. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diessner, R.; Solom, R.D.; Frost, N.K.; Parsons, L.; Davidson, J. Engagement with beauty: Appreciating natural, artistic, and moral beauty. J. Psychol. 2008, 142, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Shuai, C.; Shen, G.Q. Green retrofit of aged residential buildings in Hong Kong: A preliminary study. Build. Environ. 2018, 143, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Aman, J.; Nurunnabi, M.; Bano, S. The impact of social media on learning behavior for sustainable education: Evidence of students from selected universities in Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Gupta, A. Pro-environmental behaviour among tourists visiting national parks: Application of value-belief-norm theory in an emerging economy context. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhu, Y. How love of nature promotes green consumer behaviors: The mediating role of biospheric values, ecological worldview, and personal norms. PsyCh J. 2021, 10, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Zhao, H.; Shen, L.; Dong, L.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, K. Factors influencing residents’ intention toward green retrofitting of existing residential buildings. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A.; Maleki, F. From decision to run: The moderating role of green skepticism. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J.; Wonneberger, A. The skeptical green consumer revisited: Testing the relationship between green consumerism and skepticism toward advertising. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S. Pro-environmental behaviours among agricultural students: An examination of the value-belief-norm theory. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2019, 21, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Average Value | (Statistics) Standard Deviation | GS | FROP | FPOP | EV | NE | ME | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GS | 3.287 | 1.06 | 1 | |||||

| FROP | 3.714 | 0.85 | −0.154 ** | 1 | ||||

| FPOP | 3.642 | 0.862 | −0.129 ** | 0.448 ** | 1 | |||

| EV | 3.661 | 0.892 | −0.165 ** | 0.380 ** | 0.344 ** | 1 | ||

| NE | 3.677 | 0.865 | −0.139 ** | 0.403 ** | 0.400 ** | 0.363 ** | 1 | |

| ME | 3.77 | 0.803 | −0.154 ** | 0.523 ** | 0.501 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.468 ** | 1 |

| Trails | Efficiency Value | Magnitude of Effect | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Limit | |||

| EV | ||||

| Ind1: GS→FROP→EV | −0.062 ** | 32.3% | −0.110 | −0.026 |

| Ind2: GS→FPOP→EV | −0.041 * | 21.4% | −0.084 | −0.013 |

| Total indirect effect TIE12 | −0.104 ** | 54.2% | −0.171 | −0.046 |

| Direct effect DE12 | −0.088 | −0.188 | 0.011 | |

| Total effect TE12 | −0.192 *** | −0.289 | −0.086 | |

| diff1 = Ind1-Ind2 | −0.017 | −0.055 | 0.019 | |

| NE | ||||

| Ind3: GS→FROP→NE | −0.066 ** | 37.7% | −0.119 | −0.029 |

| Ind4: GS→FPOP→NE | −0.056 * | 32.0% | −0.106 | −0.019 |

| Total indirect effect TIE34 | −0.122 ** | 69.7% | −0.284 | −0.054 |

| Direct effect DE34 | −0.054 | −0.155 | 0.051 | |

| Total effect TE34 | −0.175 ** | −0.284 | −0.061 | |

| diff2 = Ind3-Ind4 | −0.007 | −0.043 | 0.029 | |

| ME | ||||

| Ind5: GS→FROP→ME | −0.094 ** | 46.1% | −0.154 | −0.041 |

| Ind6: GS→FPOP→ME | −0.070 * | 34.3% | −0.131 | −0.023 |

| Total indirect effect TIE56 | −0.164 *** | 80.4% | −0.254 | −0.073 |

| Direct effect DE34 | −0.040 | −0.129 | 0.050 | |

| Total effect TE34 | −0.204 *** | −0.308 | −0.090 | |

| diff3 = Ind5-Ind6 | −0.016 | −0.055 | 0.026 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hou, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Huang, Q. Green Skepticism? How Do Chinese College Students Feel about Green Retrofitting of College Sports Stadiums? Buildings 2024, 14, 2237. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072237

Hou Y, Chen S, Zhang Y, Yao Z, Huang Q. Green Skepticism? How Do Chinese College Students Feel about Green Retrofitting of College Sports Stadiums? Buildings. 2024; 14(7):2237. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072237

Chicago/Turabian StyleHou, Yuyang, Sen Chen, Yujie Zhang, Zhening Yao, and Qian Huang. 2024. "Green Skepticism? How Do Chinese College Students Feel about Green Retrofitting of College Sports Stadiums?" Buildings 14, no. 7: 2237. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072237

APA StyleHou, Y., Chen, S., Zhang, Y., Yao, Z., & Huang, Q. (2024). Green Skepticism? How Do Chinese College Students Feel about Green Retrofitting of College Sports Stadiums? Buildings, 14(7), 2237. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14072237