Occupational Accidents, Injuries, and Associated Factors among Migrant and Domestic Construction Workers in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

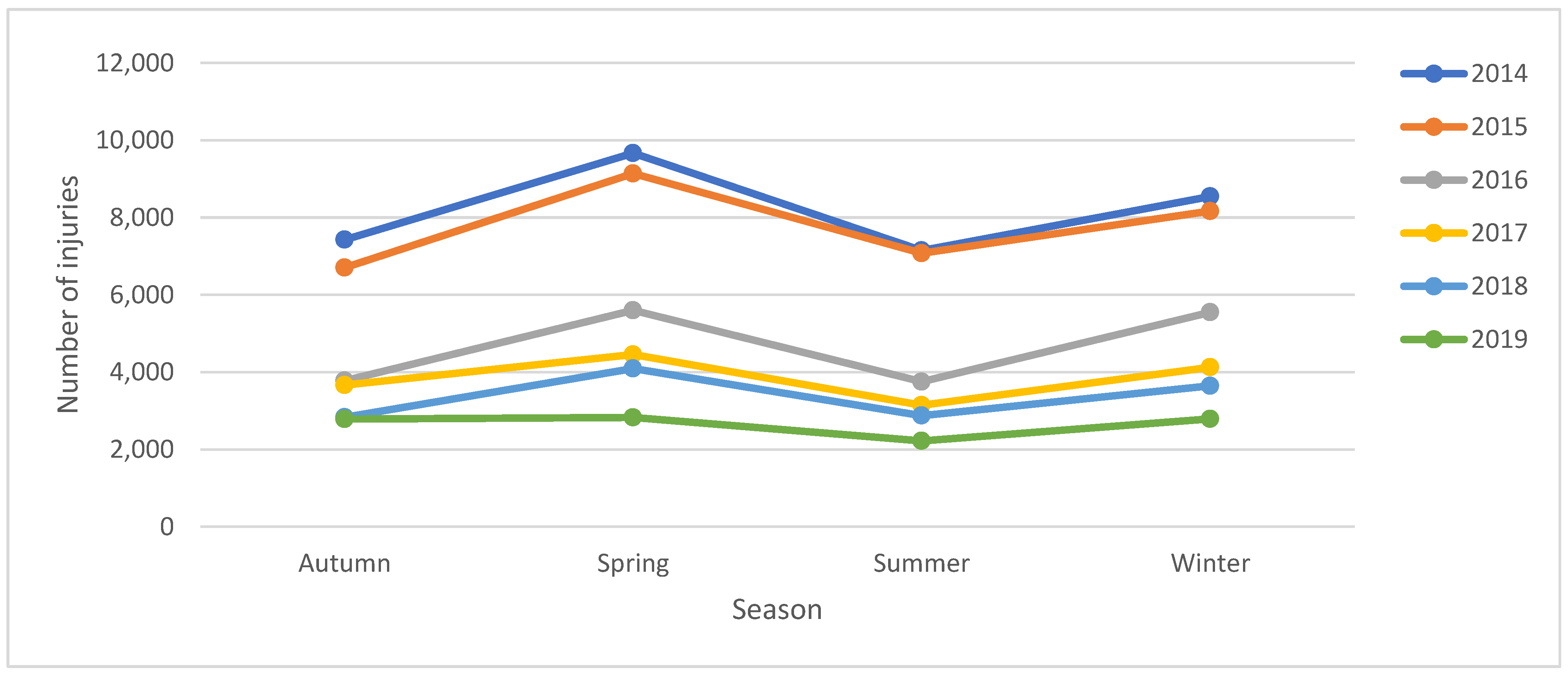

3.1. Accidents Trends

3.2. Fatal Accidents: Among Migrant and Domestic Workers

3.3. Non-Fatal Accidents among Migrant and Domestic Workers

3.4. Association between Type of Accident and Its Consequences across Domestic and Migrant Workers

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Limitations

- The research depends on the GOSI database, which may not record every single incident and could fail to obtain comprehensive knowledge on the particular causes and settings of accidents and injuries. This shortcoming causes possible underreporting or misclassification.

- Using a retrospective cohort design reduces the capacity for determining causation. Potential confounding variables that could affect the observed associations include variations in experience levels, safety training, and the enforcement of safety laws. These variables were not controlled for.

- The findings may not be applicable to industries beyond Saudi Arabia’s building industry due to its distinctive socio-economic and regulatory environment.

- The reliability of the data could also be influenced by selection bias and self-reporting inaccuracies, which could potentially distort the results.

4.2. Recommendations and Future Works

- Developing more effective and structured safety training programs using advanced technology such as wearable sensors and implementing safety audits and inspections.

- Employers and construction site managers should ensure that migrant workers use personal protective equipment appropriately at all times.

- More attention should be paid to migrant workers with less experience and knowledge of safety measures. This can include providing safety training in their native languages.

- Given the prevalence of psychosocial factors and musculoskeletal injuries in the construction industry, a comprehensive risk management technique must be implemented in order to effectively reduce these risks [37,38]. Further studies should be conducted to examine the causation of work-related accidents among migrant construction workers in SA and its potential impact on occupational health and safety is imperative.

5. Conclusions

- Routine risk assessments should be implemented to identify high-risk activities and environments that are unique to migrant workers. Development of management plans involving improved safety measures and the supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) to help to reduce identified risks.

- Develop and implement training programs that are specifically designed to address the distinct safety challenges encountered by migrant workers, with an emphasis on the prevention of falls, strikes, and collisions. Enhance the comprehension and efficacy of migrant workers by providing training that is conveniently accessible in their native languages.

- Adjust work schedules and safety measures to account for seasonal variations in accident rates, particularly during the spring when accidents are more frequent.

- Establish a robust monitoring system to track the effectiveness of implemented safety measures and make data-driven adjustments as needed. Regularly review accident and injury data to identify emerging trends and areas for improvement.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO/ILO: Almost 2 Million People Die from Work-Related Causes Each Year. Comun Prensa Conjunto 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/17-09-2021-who-ilo-almost-2-million-people-die-from-work-related-causes-each-year (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Hargreaves, S.; Rustage, K.; Nellums, L.B.; McAlpine, A.; Pocock, N.; Devakumar, D.; Aldridge, R.W.; Abubakar, I.; Kristensen, K.L.; Himmels, J.W.; et al. Occupational health outcomes among international migrant workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e872–e882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onarheim, K.H.; Egli-Gany, D.; Aftab, W. Occupational health outcomes among international migrant workers. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porru, S.; Baldo, M. Occupational Health and Safety and Migrant Workers: Has Something Changed in the Last Few Years? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekkodathil, A.; El-Menyar, A.; Al-Thani, H. Occupational injuries in workers from different ethnicities. Int. J. Crit. Illn. Inj. Sci. 2016, 6, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, R.; Lorente, L.; Vignoli, M.; Nielsen, K.; Peiró, J.M. Challenges influencing the safety of migrant workers in the construction industry: A qualitative study in Italy, Spain, and the UK. Saf. Sci. 2021, 142, 105388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, M.; Rafiq, M. An overview of construction occupational accidents in Hong Kong: A recent trend and future perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.R.; Leclercq, S.; Lockhart, T.E.; Haslam, R. State of science: Occupational slips, trips and falls on the same level. Ergonomics 2016, 59, 861–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, O.S.; Hamid, R.A.; Misnan, M.S. Analysis of Fatal Building Construction Accidents: Cases and Causes. J. Multidiscip. Eng. Sci. Technol. JMEST 2017, 4, 8030–8031. Available online: http://www.jmest.org/wp-content/uploads/JMESTN42352371.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Solomon, E.O.; Eucharia, C.E.; Felix, E.O. Accidents in Building Construction Sites in Nigeria: A Case of Enugu State. Int. J. Innov. Res. Dev. 2016, 5, 244–248. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Cho, S.I. Prohibition on changing workplaces and fatal occupational injuries among chinese migrant workers in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Migration. Migrant Workers Face Heightened Risk of Death and Injury: New IOM Report; International Organization for Migration: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Thani, H.; El-Menyar, A.; Consunji, R.; Mekkodathil, A.; Peralta, R.; Allen, K.A.; Hyder, A.A. Epidemiology of occupational injuries by nationality in Qatar: Evidence for focused occupational safety programmes. Injury 2015, 46, 1806–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, P.; Boggess, B.; Zhang, K. Assessing heat stress and health among construction workers in a changing climate: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, F.; Gebrehiwot, M.; Gizaw, Z. Workplace injury and associated factors among construction workers in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brika, S.K.M.; Adli, B.; Chergui, K. Key Sectors in the Economy of Saudi Arabia. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 696758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri-Mirza, A. Saudi Arabia: Total Number of Non-National Employed Workers in the Private Sector 2021|Statista 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1325038/saudi-arabia-total-number-of-non-national-employed-workers-in-the-private-sector/ (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Mosly, I. Safety Performance in the Construction Industry of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2015, 4, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Organization for Social Insurance (GOSI). Annual Statistical Report 1443H. 2021. Available online: https://www.gosi.gov.sa/en/StatisticsAndData/AnnualReport (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Abukhashabah, E.; Summan, A.; Balkhyour, M. Occupational accidents and injuries in construction industry in Jeddah city. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 1993–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, S.M.; Kamel, S.; Assiri, A.M.; Almeshal, A.S. The Epidemiology of Work-Related Injuries in Saudi Arabia Between 2016 and 2021. Cureus 2023, 15, e35849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.; Ammar, A.I. The Effect of Season on Construction Accidents in Saudi Arabia. Emir. J. Eng. Res. 2019, 24, 5. Available online: https://scholarworks.uaeu.ac.ae/ejer/vol24/iss4/5 (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Guan, Z.; Yiu, T.W.; Samarasinghe, D.A.S.; Reddy, R. Health and safety risk of migrant construction workers—A systematic literature review. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 31, 1081–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Construction: A hazardous work. Occup. Health Saf. 2015, 1–2. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/resource/construction-hazardous-work (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Ahonen, E.Q.; Benavides, F.G. Risk of fatal and non-fatal occupational injury in foreign workers in Spain. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 424–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, K.S.; Yang, H.S.; Guedes Soares, C. Accidents of foreign workers at construction sites in Korea. J. Asian Archit. Build Eng. 2013, 12, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biering, K.; Lander, F.; Rasmussen, K. Work injuries among migrant workers in Denmark. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 74, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, A.J.; Abudayyeh, O.; Albert, A. Managing active cultural differences in U.S. construction workplaces: Perspectives from non-Hispanic workers. J. Saf. Res. 2018, 66, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.W.; Wu, T.C. An investigation and analysis of major accidents involving foreign workers in Taiwan’s manufacture and construction industries. Saf. Sci. 2013, 57, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Son, K.; Yum, S.G.; Ahn, S. Analyzing the risk of safety accidents: The relative risks of migrant workers in construction industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwatka, N.V.; Butler, L.M.; Rosecrance, J.R. An aging workforce and injury in the construction industry. Epidemiol. Rev. 2012, 34, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barss, P.; Addley, K.; Grivna, M.; Stanculescu, C.; Abu-Zidan, F. Occupational injury in the United Arab Emirates: Epidemiology and prevention. Occup. Med. 2009, 59, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lette, A.; Ambelu, A.; Getahun, T.; Mekonen, S. A survey of work-related injuries among building construction workers in southwestern Ethiopia. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2018, 68, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuma, M.A.; Acerra, J.R.; El-Menyar, A.; Al-Thani, H.; Al-Hassani, A.; Recicar, J.F.; Al Yazeedi, W.; Maull, K. Epidemiology of workplace-related fall from height and cost of trauma care in Qatar. Int. J. Crit. Illn. Inj. Sci. 2013, 3, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraudo, M.; Bena, A.; Costa, G. Migrant workers in Italy: An analysis of injury risk taking into account occupational characteristics and job tenure. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, V.; Rothenbacher, D.; Daniel, U.; Zschenderlein, B.; Schuberth, S.; Brenner, H. All-cause and cause specific mortality in a cohort of 20 000 construction workers; results from a 10 year follow up. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 61, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreshpaj, B.; Bodin, T.; Wegman, D.H.; Matilla-Santander, N.; Burstrom, B.; Kjellberg, K.; Davis, L.; Hemmingsson, T.; Jonsson, J.; Håkansta, C. Under-reporting of non-fatal occupational injuries among precarious and non-precarious workers in Sweden. Occup. Environ. Med. 2022, 79, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; International Labour Organization. List of Occupational Diseases (revised 2010) [Report]. In Occupational Safety and Health Series 2010; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Volume 74. [Google Scholar]

| General Organization for Social Insurance (GOSI) | |

|---|---|

| Data Categories | Description |

| Workers Time period provided | Categorization as Saudi (domestic) or non-Saudi (migrant) 2014–2019 |

| Fatal and Non-Fatal Accidents/Injuries | Fatal accidents: Resulting in death Non-fatal accidents: Resulting in >1 day of work absence |

| Type of Accidents/Injuries (Recorded by GOSI) Consequences of work-related accidents | Falls Strikes and Collision (struck by objects or materials) Rubbing and Abrasion (injuries from scraping or abrasion) Transport and Vehicle Accidents that related to construction Bodily reactions (reactions to chemicals or materials) Other Full recovery Under recovery Permanent disability Fatality (death) |

| Seasons | Spring (March–May) Summer (June–August) Autumn (September–November) Winter (December–February). |

| Age Groups | <20 years 20–29 years 30–39 years 40–49 years 50–59 years 60+ years |

| Industry | Construction |

| Variables | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accidents % Compared to Total Accidents for All Industries | 32,781 | 31,085 | 18,681 | 15,389 | 13,442 | 10,621 | 22,275.6 |

| 47.3% | 46.3% | 35.0% | 36.3% | 36.5% | 34.76% | 41.4% | |

| Fatality Rate (Per 100,000) | 7.9 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 4.2 |

| Non-Fatal Accident Rate (Per 1000) | 8.3 | 7.3 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 4.6 | 5.4 |

| Variable | Overall 2 | Migrant N 1 (%) | Domestic N 1 (%) | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatal accidents No Yes | 311,682 (99.9) 973 (0.1) | 2,764,697 (99.9) 914 (0.1) | 346,985 (99.9) 59 (0.1) | <0.01 |

| Fatal accidents by age group | <0.001 | |||

| <20 | 3 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 2 (3.4) | |

| 20–29 | 259 (26.6) | 231 (25.3) | 28 (47.5) | |

| 30–39 | 324 (33.3) | 306 (33.5) | 18 (30.5) | |

| 40–49 | 260 (26.7) | 254 (27.8) | 6 (10.1) | |

| 50–59 | 96 (9.9) | 91 (10.0) | 5 (8.5) | |

| >60 | 31 (3.2) | 31 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Type of fatal accident | 0.02 | |||

| Fall | 176 (18.0) | 176 (19.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Stuck and Collision | 99 (10.2) | 97 (10.6) | 2 (3.4) | |

| Rubbed and Abrasion | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 37 (3.8) | 36 (4) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Bodily Reaction | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Transport and Car Accidents | 584 (60.0) | 528 (57.7) | 56 (95.0) | |

| Seasons | 0.90 | |||

| Autumn | 249 (25.6) | 232 (25.4) | 17 (28.8) | |

| Spring | 263 (27.0) | 248 (27.1) | 15 (25.4) | |

| Summer | 209 (21.5) | 198 (21.7) | 11 (19.3) | |

| Winter | 252 (25.9) | 236 (25.8) | 16 (27.0) | |

| Variable | Overall n (%) | Migrant N 1 (%) | Domestic N 1 (%) | p-Value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-fatal accidents No Yes | 2,991,629 (96.1) 121026 (4.0) | 2,646,095 (95.7) 119516 (4.5) | 345,534 (99.6) 1510 (0.4) | <0.01 |

| Non-fatal accidents by age group | <0.001 | |||

| <20 | 45 (0.0) | 15 (0.0) | 30 (2.0) | |

| 20–29 | 36,610 (30.2) | 35,857 (30.0) | 753 (49.9) | |

| 30–39 | 47,237 (39.0) | 46,749 (39.0) | 488 (32.3) | |

| 40–49 | 25,018 (20.7) | 24,847 (20.8) | 171 (11.3) | |

| 50–59 | 9843 (8.1) | 9790 (8.2) | 53 (3.5) | |

| >60 | 2273 (1.9) | 2258 (1.9) | 15 (1.0) | |

| Type of non-fatal accident | <0.01 | |||

| Fall | 39,626 (32.7) | 39,150 (32.8) | 476 (31.5) | |

| Stuck and Collision | 32,483 (26.8) | 32,170 (26.9) | 313 (20.7) | |

| Rubbed and Abrasion | 15,398 (12.7) | 15,298 (12.8) | 100 (6.6) | |

| Other | 9324 (7.7) | 9243 (7.7) | 81 (5.4) | |

| Bodily Reaction | 7186 (5.9) | 7098 (5.9) | 88 (5.8) | |

| Transport and Car Accidents | 5974 (4.9) | 5717 (4.8) | 257 (17.0) | |

| Non-fatal accidents by seasons | 0.378 | |||

| Autumn | 26,940 (22.3) | 26,584 (22.2) | 356 (23.6) | |

| Spring | 35,502 (29.3) | 35,046 (29.3) | 456 (30.2) | |

| Summer | 26,023 (21.5) | 25,712 (21.5) | 311 (20.6) | |

| Winter | 32,561 (26.9) | 32,174 (26.9) | 387 (25.6) | |

| Consequences | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Accident | Full Recovery n 1 (%) | Under Recovery n 1 (%) | Permanent Disability n 1 (%) | Fatality n 1 (%) | Total n 1 (%) | p-Value 2 |

| Fall | 24,048 (60.4) | 12,906 (32.4) | 2672 (6.7) | 176 (0.4) | 39,802 (100.0) | 0.021 |

| Migrant | 23,730 (60.3) | 12,774 (32.5) | 2646 (6.7) | 176 (0.4) | 39,326 (100.0) | |

| Domestic | 318 (66.8) | 132 (27.7) | 26 (5.5) | 0 (0) | 476 (100.0) | |

| Strike and Collision | 23,411 (71.8) | 7211 (22.1) | 1861 (5.7) | 99 (0.3) | 32,582 (100.0) | 0.676 |

| Migrant | 23,181 (71.8) | 7146 (22.1) | 1843 (5.7) | 97 (0.3) | 32,267 (100.0) | |

| Domestic | 230 (73) | 65 (20.6) | 18 (5.7) | 2 (0.0) | 315 (100.0) | |

| Rubbing and Abrasion | 11,218 (72.8) | 3145 (20.4) | 1035 (6.7) | 2 (0.0) | 15,400 (100.0) | 0.990 |

| Migrant | 11,144 (72.8) | 3125 (20.4) | 1029 (6.7) | 2 (0.0) | 15,300 (100.0) | |

| Domestic | 74 (74.0) | 20 (20.0) | 6 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) | 100 (0.6) | |

| Other | 6345 (67.8) | 2345 (25.1) | 634 (6.8) | 37 (0.4) | 9361 (100.0) | 0.054 |

| Migrant | 6300 (67.9) | 2318 (24.9) | 625 (6.7) | 36 (0.4) | 9279 (100.0) | |

| Domestic | 45 (54.9) | 27 (32.9) | 9 (10.9) | 1 (1.2) | 82 (100.0) | |

| Bodily Reaction | 5524 (76.8) | 1388 (19.3) | 274 (3.8) | 2 (0.0) | 7188 (100) | 0.445 |

| Migrant | 5456 (76.8) | 1374 (19.3) | 268 (3.8) | 2 (0.0) | 7100 (100) | |

| Domestic | 68 (77.2) | 14 (15.9) | 6 (6.8) | 0 (0.0) | 88 (100) | |

| Transport and Car Accidents | 2045 (31.2) | 3397 (51.8) | 532 (8.1) | 584 (8.9) | 6558 (100) | 0.001 |

| Migrant | 1973 (31.6) | 3235 (51.8) | 509 (8.2) | 528 (8.5) | 6245 (100) | |

| Domestic | 72 (23.0) | 162 (51.7) | 23 (7.3) | 56 (17.9) | 313 (100.0) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alruwaili, M.; Carrillo, P.; Soetanto, R.; Munir, F. Occupational Accidents, Injuries, and Associated Factors among Migrant and Domestic Construction Workers in Saudi Arabia. Buildings 2024, 14, 2714. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14092714

Alruwaili M, Carrillo P, Soetanto R, Munir F. Occupational Accidents, Injuries, and Associated Factors among Migrant and Domestic Construction Workers in Saudi Arabia. Buildings. 2024; 14(9):2714. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14092714

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlruwaili, Musaad, Patricia Carrillo, Robby Soetanto, and Fehmidah Munir. 2024. "Occupational Accidents, Injuries, and Associated Factors among Migrant and Domestic Construction Workers in Saudi Arabia" Buildings 14, no. 9: 2714. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14092714

APA StyleAlruwaili, M., Carrillo, P., Soetanto, R., & Munir, F. (2024). Occupational Accidents, Injuries, and Associated Factors among Migrant and Domestic Construction Workers in Saudi Arabia. Buildings, 14(9), 2714. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14092714