Research on Child-Friendly Evaluation and Optimization Strategies for Rural Public Spaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Theoretical Foundation: Child Behavior and Psychology

2.3. Methodological Framework

2.4. Construction of Evaluation Indicators

2.4.1. Indicator Selection and Generalization

2.4.2. Indicator Screening and Revision

2.4.3. Assignment of Indicator Weights and Consistency Tests

3. Results

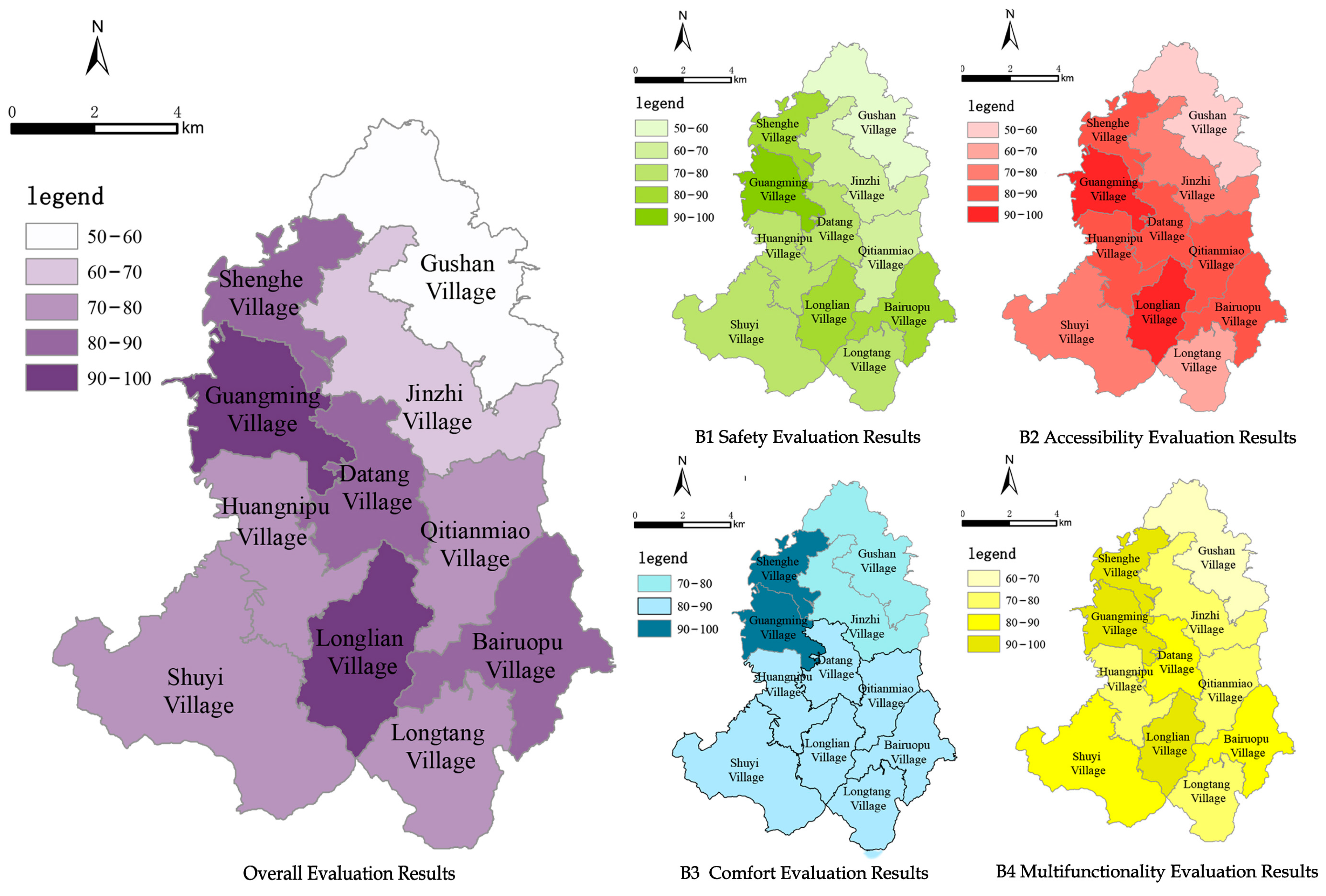

3.1. Overall Conclusion

3.2. Overview of Primary Indicators

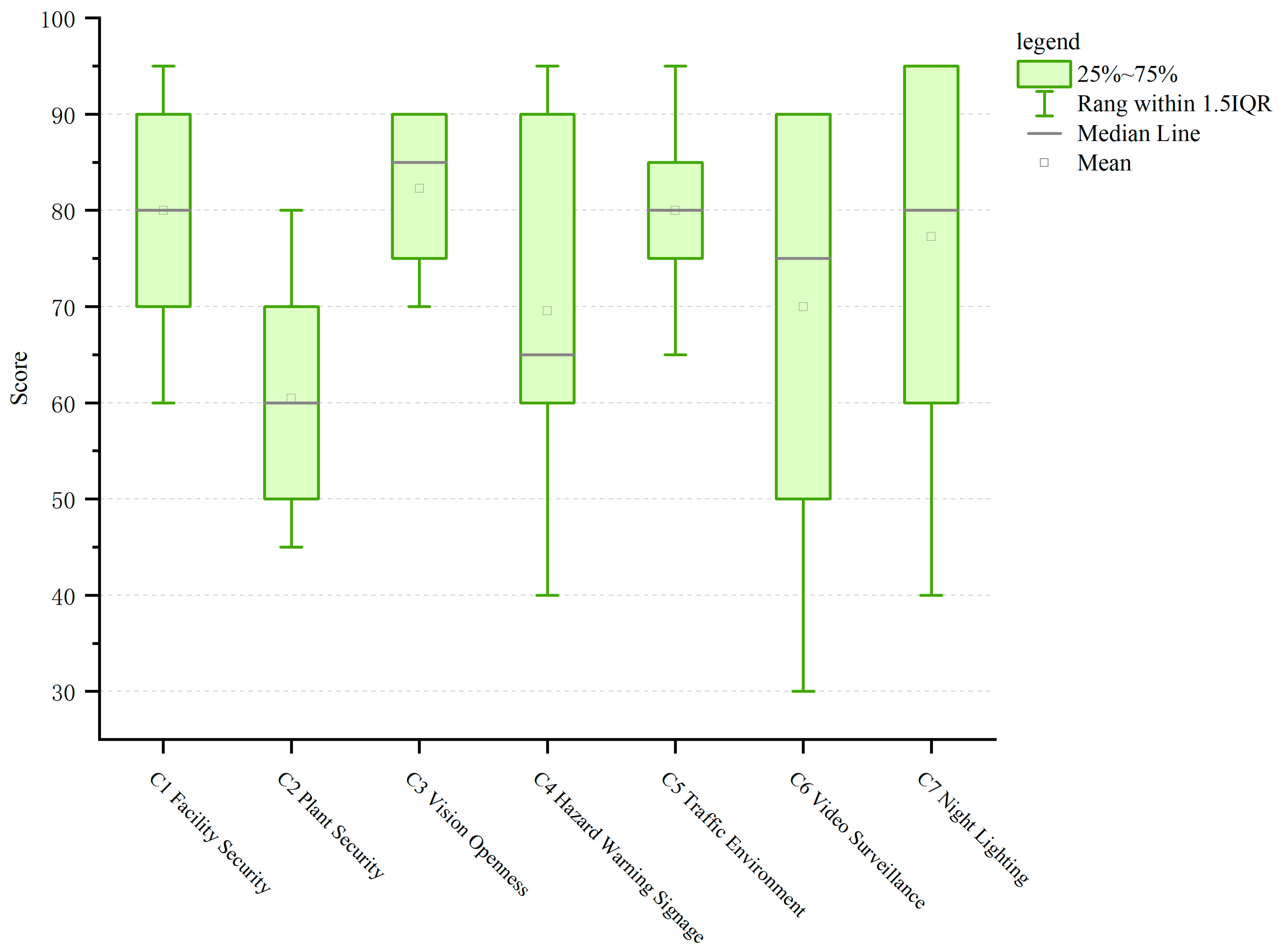

3.2.1. Analysis of Safety Primary Indicator Results

- C1—Facility Security evaluates whether outdoor equipment and facilities for children’s activities are free of sharp edges and corners and whether damaged or outdated equipment is promptly repaired or replaced [36]. This indicator generally scores high, with Longlian Village scoring the highest at 95 points and Gushan Village the lowest at 60 points.

- C2—Plant Security assesses whether plants within children’s outdoor activity spaces, including flowers, fruits, and leaves, are non-toxic, free from irritating odors, and devoid of dense or tall hazardous vegetation [35]. Relevant areas should have warning signs. This indicator scores the lowest among the safety indicators, with Guangming Village scoring the highest at 80 points and Longtang Village and Gushan Village the lowest at 45 points.

- C3—Vision Openness measures the visibility within and around village activity spaces, ensuring that no tall plants or buildings obstruct the view, thereby avoiding dangerous blind spots [35]. This indicator generally scores high with concentrated scores, with Guangming Village, Shenghe Village, and Longlian Village all scoring the highest at 90 points, and Gushan Village the lowest at 70 points.

- C4—Hazard Warning Signage primarily assesses whether warning signs are installed at the entrances to areas unsuitable for children’s activities, such as cliffs or water bodies [35], and whether traffic calming measures like speed bumps and pedestrian crossings are implemented on routes frequently used by children [26]. This indicator generally scores low, with Guangming Village scoring the highest at 95 points and Gushan Village the lowest at 40 points.

- C5—Traffic Environment evaluates whether outdoor children’s activity areas are free from large vehicle crossings and whether pedestrian pathways are smooth and free of steep slopes or deep pits [35]. This indicator generally scores high with concentrated values, with Guangming Village scoring the highest at 95 points and Gushan Village the lowest at 65 points.

- C6—Video Surveillance examines whether security cameras and protective facilities are installed in children’s activity areas to ensure safety and enable independent activities for children [36]. This indicator shows the largest score difference, with Guangming Village, Shenghe Village, and Longlian Village scoring the highest at 90 points, while Gushan Village scores the lowest at 30 points.

- C7—Night Lighting assesses the adequacy of lighting and barrier-free facilities in rural public spaces to ensure safe access for young children and children with disabilities during nighttime activities [36]. This indicator shows significant score differences, with Guangming Village, Shenghe Village, and Longlian Village scoring the highest at 95 points, and Gushan Village the lowest at 40 points.

3.2.2. Analysis of Accessibility Primary Indicator Results

- C8—Ease of Route assesses whether the routes for children to walk to rural activity areas are not overly long and are straightforward and easy to remember [27]. This indicator generally has high scores, with Longlian Village achieving the highest score of 95 points, while Longtang Village and Gushan Village scored the lowest at 60 points.

- C9—Travel Distance evaluates the distribution and placement of public spaces to ensure appropriate travel distances for children from different parts of rural areas, thereby minimizing walking or cycling time [21]. This indicator also shows generally high scores, with Longlian Village scoring the highest at 95 points, and Gushan Village scoring the lowest at 50 points.

- C10—Convenient Entry measures the visibility and prominence of entrance markers in rural public spaces, which should attract children and facilitate easy access [27]. This indicator shows moderate overall scores with notable variation among villages; Guangming Village scores the highest at 95 points, while Longtang Village scores the lowest at 50 points.

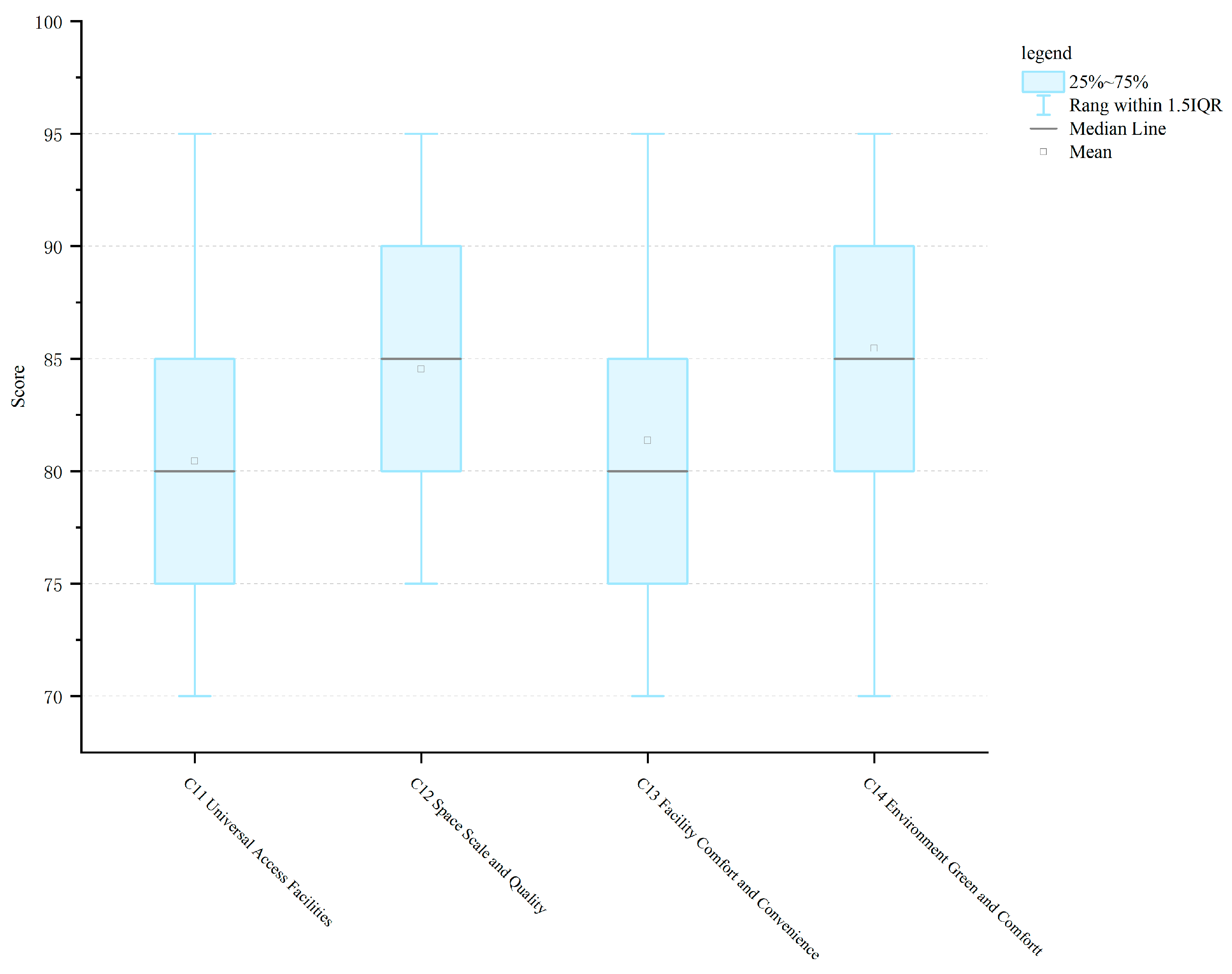

3.2.3. Analysis of Comfort Primary Indicator Results

- C11—Universal Access Facilities assesses whether rural public spaces are equipped with barrier-free facilities that ensure easy access and convenience for young children and children with disabilities [21]. This indicator generally shows lower scores across the villages, with Guangming Village achieving the highest score of 95 points, and Gushan Village scoring the lowest at 70 points.

- C12—Spatial Scale and Quality evaluates whether the spatial scale is appropriate, ensuring a balanced level of enclosure and privacy [21]. This indicator generally scores high, with Guangming Village at 95 points and Gushan Village at 75 points.

- C13—Facility Comfort and Convenience focuses on whether the layout of play facilities is reasonable [36]. This indicator generally shows lower scores, with Guangming Village scoring the highest at 95 points, and both Jinzhi Village and Gushan Village scoring the lowest at 70 points.

- C14—Environment Green and Comfort assesses whether the overall environment, including color and form, meets children’s physiological and psychological needs. It also considers if the selection of trees, flowers, and greenery enhances aesthetic appeal [36]. This indicator generally scores high, with Shenghe Village achieving the highest score of 95 points, and Gushan Village the lowest at 70 points.

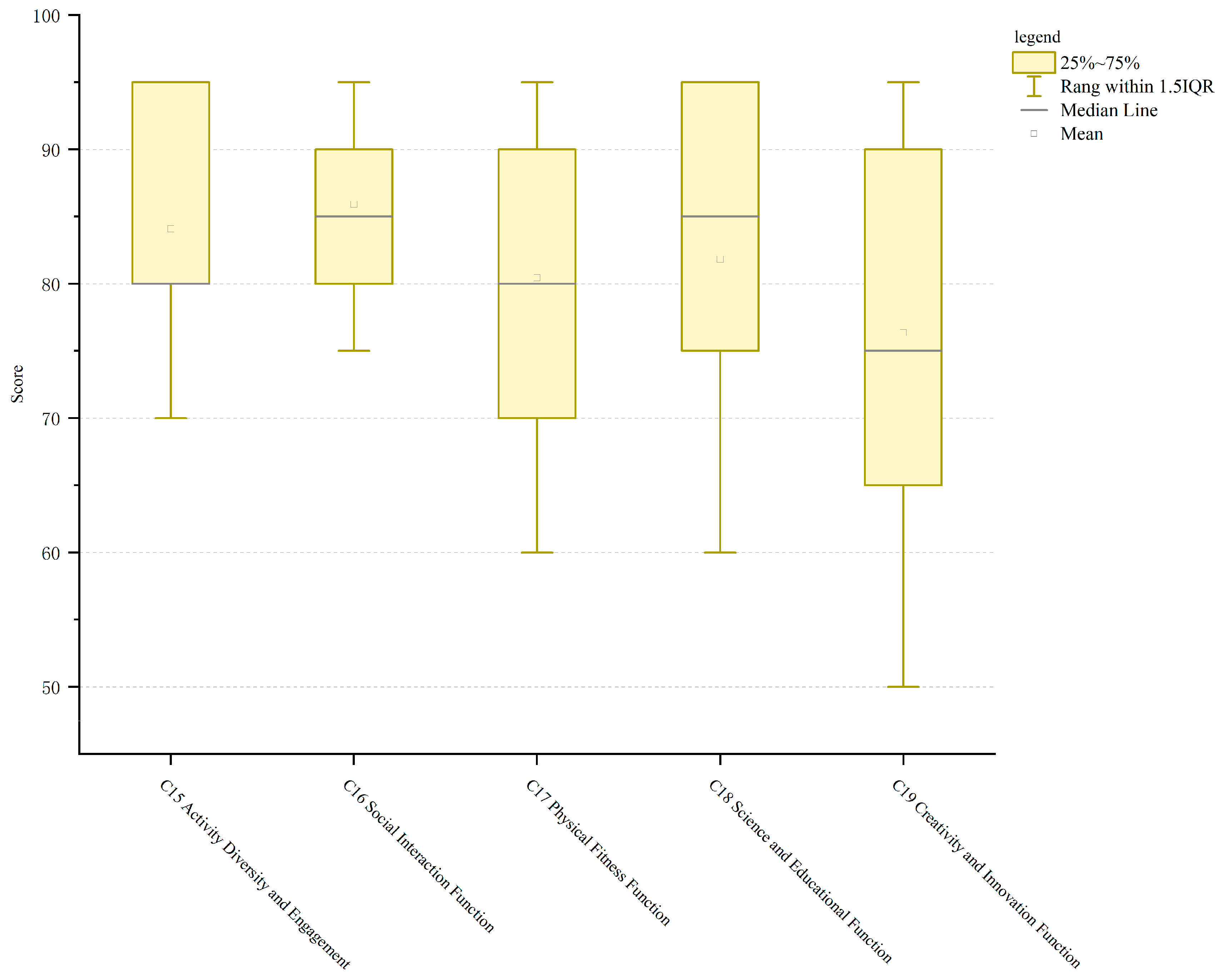

3.2.4. Analysis of Multifunctionality Primary Indicator Results

- C15—Activity Diversity and Engagement assesses the range of play facilities available in public spaces to accommodate diverse activity needs [36]. This indicator generally exhibits high scores, with Guangming Village, Shenghe Village, and Longlian Village all scoring the highest at 95 points, while Gushan Village has the lowest score at 70 points.

- C16—Social Interaction Function evaluates whether spaces provide interactive play areas that help foster children’s social skills and teamwork abilities (22). This indicator generally exhibits high and relatively consistent scores across the villages, with Guangming Village and Longlian Village scoring the highest at 95 points, and Gushan Village the lowest at 75 points.

- C17—Physical Fitness Function measures the availability of facilities that enable children to engage in various physical activities [22]. The overall scores for this indicator are moderate, with Guangming Village and Longlian Village scoring the highest at 95 points, while Jinzhi Village and Gushan Village score the lowest at 75 points.

- C18—Science and Educational Function examines whether rural areas have spaces, such as cultural activity rooms, that support educational activities and foster learning [35]. This indicator shows the highest scores in Guangming Village, Shenghe Village, and Longlian Village, all at 95 points, whereas Gushan Village scores the lowest at 60 points.

- C19—Creativity and Innovation Function assesses whether the design and layout of rural public spaces can stimulate children’s curiosity and enhance their creativity [35]. This indicator has the lowest average score among all, with substantial variation between villages. Guangming Village and Longlian Village score the highest at 95 points, while Gushan Village scores the lowest at 50 points.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion and Analysis

4.1.1. Overall Analysis

4.1.2. Analysis of Primary Indicators

- The allocation of existing public administration and service facilities in rural areas plays a decisive role in influencing the Multifunctionality sub-indicator and has a significant impact on the Accessibility and Comfort sub-indicators. According to the “Technical Guidelines for Village Planning Standards of Hunan Province” [46], rural public administration and service facilities primarily include public administration facilities such as village committees; educational facilities such as kindergartens, primary, and secondary schools; cultural and sports facilities such as sports grounds and cultural centers; medical facilities like clinics; social welfare facilities such as elderly care centers; and commercial service facilities like farmers’ markets and convenience stores. The Multifunctionality sub-indicator in the evaluation framework primarily measures whether rural public spaces can support diverse cultural, sports, and recreational activities for children. Educational and cultural facilities within rural public management and service frameworks are closely linked to the child-friendliness of rural public spaces. In this study, Guangming Village, Shenghe Village, and Longlian Village each have both kindergartens and primary schools. As the seat of the Bairuopu Town government, Longlian Village also hosts town-level kindergartens and primary and secondary schools, resulting in very high scores for the Multifunctionality sub-indicator. Although Datang Village lacks a kindergarten, it includes one nine-year compulsory education school and one senior high school. Bairuopu Community and Shuyi Village each have one primary school. Longtang Village, while lacking both kindergartens and primary schools, has dedicated public basketball courts and cultural activity facilities, leading to a moderate score. In contrast, Huangnipou Village, Qitianmiao Village, Jinzhi Village, and Gushan Village lack kindergartens, primary schools, and other cultural and sports facilities, resulting in the lowest scores. Villages with more public service facilities generally provide more public spaces for outdoor activities for children, thereby enhancing Accessibility and improving the quality of built recreational facilities. Consequently, these villages also achieve higher scores in the Accessibility and Comfort sub-indicators within the evaluation framework.

- The presence of tertiary industries, especially child-centered cultural and tourism sectors, exerts a substantial influence on the Multifunctionality, Safety, and Accessibility sub-indicators. The highest-scoring village, Guangming Village, is recognized as a “National Characteristic Scenic Tourism Town” and features the “Guangming Grand Garden”, a national 4A-level scenic spot renowned as a family-friendly tourism destination in Changsha, attracting an annual footfall of 1.5 million visitors. It achieves the highest scores in Safety, Comfort, and Multifunctionality. Due to some parts of the scenic area being located within Shenghe Village, it ranks second in Comfort and Multifunctionality. Additionally, Shuyi Village is home to a museum and an ancient temple, while Huangnipou Village and Datang Village feature historic temples and agricultural creative parks, respectively. These villages, endowed with certain tourism resources, score relatively high in the Multifunctionality sub-indicator. In contrast, villages lacking tourism resources generally have lower scores. This analysis indicates that the types of rural industries, particularly the integration of tertiary sectors focused on children’s tourism, have a significant impact on the child-friendliness of rural public spaces.

- The transportation environment in rural areas significantly impacts the child-friendliness of public spaces. The convenience and connectivity of transportation networks are positively correlated with Accessibility, but can negatively affect Safety indicators in certain villages. Within Bai Ruo Pu Town, the east–west Changchang Expressway traverses Shenghe Village and Jinzhi Village, while the Changji Expressway runs through Shuyi Village and Longtang Village. The north–south Xuguang Expressway crosses Bairuopu Community, Qitianmiao Village, and Gushan Village, but due to the absence of entry and exit ramps within Bai Ruo Pu, their overall impact remains minimal. Jinzhou Avenue, an east–west arterial road linking Changsha and Ningxiang, passes through Qitianmiao Village, Datang Village, and Guangming Village, resulting in higher scores for these villages under the Accessibility primary indicator. The higher classification of this road, along with improved municipal infrastructure such as surveillance systems and street lighting, contributes to higher scores in safety-related sub-indicators. However, since Jinzhou Avenue is a transit route with frequent large trucks traveling at high speeds, the scores for the surrounding traffic environment indicators are generally low. Running parallel to Jinzhou Avenue is the G319 National Highway, which formerly served as the main connection between the two cities before Jinzhou Avenue’s construction. It runs east to west through Bairuopu Community, Longlian Village, and Huangnipou Village, experiencing a similar situation to those villages along Jinzhou Avenue. However, with the decline in G319′s significance post-Jinzhou Avenue opening, these differences are less marked. Additionally, the town’s internal secondary and feeder roads generally receive high scores for both Safety and Accessibility.

4.2. Strategic Recommendations

4.2.1. Leveraging Village Planning as a Tool for Integrated and Coordinated Planning from a Child-Friendly Perspective

4.2.2. Focus on Spatial Optimization to Create Safe, Engaging, and Highly Accessible Rural Public Spaces for Children

4.2.3. Enhancing Interaction and Popularization of Child-Friendly Rural Development through Child Participation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2012: Children in an Urban World; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-92-1-059758-6. [Google Scholar]

- CFCI Framework Child-Friendly Cities Initiative. Available online: https://www.childfriendlycities.org/cfci-framework (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Cappa, C.; Petrowski, N. Thirty Years after the Adoption of the Convention on the Rights of the Child: Progress and Challenges in Building Statistical Evidence on Violence against Children. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 110, 104460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- State Council Working Committee on Women and Children. Children’s Development Plan Outline for the 1990s [EB/OL]. Available online: https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E4%B9%9D%E5%8D%81%E5%B9%B4%E4%BB%A3%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD%E5%84%BF%E7%AB%A5%E5%8F%91%E5%B1%95%E8%A7%84%E5%88%92%E7%BA%B2%E8%A6%81/4062063?fr=ge_ala. (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Kim, Y. Children’s Walking to Urban Services: An Analysis of Pedestrian Access to Social Infrastructures and Its Relationship with Land Use. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2023, 37, 189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wu, D.; Hang, T.; Ding, H.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Q. Constructing Child-Friendly Cities: Comprehensive Evaluation of Street-Level Child-Friendliness Using the Method of Empathy-Based Stories, Street View Images, and Deep Learning. Cities 2024, 154, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geravandi, A. An In-Depth Perspective Analysis for Developing a Social Marketing Model to Promote Female Adolescents’ Participation in Regular Physical Activities: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 15094–15108. [Google Scholar]

- Hermosilla, S.; Metzler, J.; Savage, K.; Musa, M.; Ager, A. Child Friendly Spaces Impact Across Five Humanitarian Settings: A Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.E.; Gosselin, V.; Collins, P.; Frohlich, K.L. A Tale of Two Cities: Unpacking the Success and Failure of School Street Interventions in Two Canadian Cities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Huang, B.; Su, J.; Zhang, H. Safety Street Design Strategies for Child-Friendly Environment: An Empirical Study of Residential Community in Beijing Old City. Shanghai Urban Plan. Rev. 2020, 3, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, H.; Whitzman, C.; Pieters, J.; Allan, A. Children’s Everyday Freedoms: Local Government Policies on Children and Sustainable Mobility in Two Australian States. J. Transp. Geogr. 2018, 71, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, N. Policy Innovation on Building Child-Friendly Cities in China: Evidence from Four Chinese Cities. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105491. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Vinueza, V.A.; Niekerk, F.; van Dijk, T. Making Child-Friendly Cities: A Socio-Spatial Literature Review. Cities 2023, 137, 104248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, X.; Guo, Y. The Impact of a Child-Friendly Design on Children’s Activities in Urban Community Pocket Parks. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Wei, H. Planning and Design of Children-Friendly Outdoor Activity Space in Residential Area. Huazhong Archit. 2022, 40, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.; Liu, L.Y. Practice of Participation Construction in Shanghai Community Gardens from Child-Friendly Perspective. Landsc. Des. 2022, 1, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, M.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Woolley, H. Research on the Mechanisms of Built Environment and Children’s Travel from the Perspective of Environmental Behavior Studies. China Landsc. Archit. 2022, 38, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- RTPI. Children and Town Planning; Royal Town Planning Institute: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Said Mahmoudi, P.; Leviner, P.; Kaldal, A.; Lainpelto, K. Child-Friendly Justice: A Quarter of a Century of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child; Brill Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Li, L. A Study on the Evaluation System of Child-Friendly Residential Space Environments: From the Perspective of Child Caregivers. Urban Probl. 2022, 45, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, A.; Chen, X.; Deng, W.; Xiao, X. Child-Friendly Communities Based on Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation: A Case Study of Caohu Garden in Suzhou. Huazhong Archit. 2023, 41, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.; Furuya, K. A Bibliometric Analysis of Child-Friendly Cities: A Cross-Database Analysis from 2000 to 2022. Land 2023, 12, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Research on the Construction of an Evaluation System for Interaction Spaces in Kindergartens in the Lanzhou Region under the Background of Child-Friendliness. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Y.; Liu, L.; Wei, L.; Zhou, X. The Practice and Exploration of Planning Standards and Guidelines for Children’s Playgrounds: Taking London and Shenzhen as Examples. Urban Dev. Stud. 2022, 29, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D.; Shi, Y.; Chen, R. Environmental Affordances and Children’s Needs: Insights from Child-Friendly Community Streets in China. Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 12, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orso, G.; Migliore, M. A GIS-Based Method for Evaluating the Walkability of a Pedestrian Environment and Prioritized Investments. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 82, 102555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Ao, Y.; Bahmani, H. Child Friendliness of Rural School Travel Road: Improvement Strategies Based on Rural Children’s Perception. J. Transp. Health 2023, 32, 101674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbu, A.H.; Haque, M. A Framework for the Design of Pediatric Healthcare Environment Using the Delphi Technique. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 14, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y. Children’s Hospital Environment Design Based on AHP/QFD and Other Theoretical Models. Buildings 2024, 14, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Peng, S. Optimizing Rural Public Space Design Based on Child-Friendly Concepts: A Case Study of the Main Street Area in Dong Yang Tuo Village, Beijing. J. Small Town Rural Dev. 2024, 42, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics. The Main Data from the Seventh National Population Census. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202302/t20230203_1901080.html (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, J. The Construction of Reality in the Child; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Zhejiang Province. Guideline for Child-Friendly Rural Village Construction; Group Standard. 2022. Available online: https://www.xiaoshan.gov.cn/art/2022/12/26/art_1302906_59081696.html (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Guideline for the Construction of Child-Friendly Urban Spaces; State Guideline. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-12/04/content_5730111.htm (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, J. A Review of the Development and Application of Grounded Theory. J. Shenyang Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 10, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Guo, J.; Zhao, T. Research on the Image of Outstanding Rural Teachers: A Qualitative Analysis Based on NVivo12. Educ. Guide 2021, 10, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. The Analytic Hierarchy Process: Planning, Priority Setting, Resource Allocation; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Baidu. Baixuopu Town. Available online: https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E7%99%BD%E7%AE%AC%E9%93%BA%E9%95%87/3720286?fr=ge_ala (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Chen, Y.C.; Fan, S.S. Evaluation of Non-use Value and Analysis of Factors Affecting Willingness to Pay in Leisure Farms: A Case Study of Qianjiangyue Leisure Farm. China Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2018, 39, 290–297. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, S. Study on the Preference Characteristics of Outdoor Activity Spaces for Rural Children. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, T.J. Strategies for Enhancing Child-Friendliness in Rural Public Spaces in the Suburban Areas of Changsha. Master’s Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, K. Optimization of Rural Environments Based on Children’s Preferences for Outdoor Activities. Master’s Thesis, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.F. Theoretical Origins, Evolutionary Stages, and Analytical Framework of Child-Friendly Cities: A Research Perspective from the Childhood Viewpoint. Urban Plan. 2024, 48, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Hunan Province. Village Planning Standards Technical Outline. Available online: http://zrzyt.hunan.gov.cn/xxgk/tzgg/201905/t20190507_5328389.html (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Liao, Y.D. Application of Child-Friendly Concepts and Rural Revitalization Based on AHP-CRITIC Evaluation: A Case Study of Guangming Village in Baishoupu Town, Changsha. China Market. 2023, 21, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.R.; Chen, Z. Renewal and Design Strategies for Child-Friendly Public Spaces in Rural Areas. Chin. Foreign Archit. 2022, 8, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People’s Republic of China. Urban and Rural Planning Law. Available online: https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E4%B8%AD%E5%8D%8E%E4%BA%BA%E6%B0%91%E5%85%B1%E5%92%8C%E5%9B%BD%E5%9F%8E%E4%B9%A1%E8%A7%84%E5%88%92%E6%B3%95/8758008?fr=ge_ala (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Fan, J.; Liu, F. Spatial Planning of Rural Children’s Commuting Paths under the Background of Rural Revitalization: A Case Study of Changsha City. J. Chang. Univ. 2023, 37, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

| Total Number of Experts | By Professional Field | By Type of Institution | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban and Rural Planning | Landscape Architecture | Architecture | Agricultural and Forestry Economics and Management | Higher Education Institutions | Design Institutes | Administrative Units | |

| 25 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 8 | 5 |

| Target Layer | Primary Indicators (Primary Indicators) | Indicator Layer (Secondary Indicators) | Description of Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation of the child-friendliness of rural public spaces | B1 Safety | C1 Facility Security | Outdoor equipment and facilities for children’s activities should be free of sharp edges and corners. Damaged or outdated equipment must be promptly repaired or replaced. |

| C2 Plant Security | Plants within activity spaces, including flowers, fruits, and leaves, should be non-toxic, free from irritating odors, and devoid of dense or tall hazardous vegetation. | ||

| C3 Vision Openness | There should be no tall plants or buildings obstructing the view to avoid creating dangerous blind spots. | ||

| C4 Hazard Warning Signage | Hazard warning signage should be placed at the entrances of areas unsuitable for children’s activities, such as cliffs with falling rocks or the edges of ponds and rivers. Prohibitive signs should be installed in wooded areas to discourage children from climbing. Additionally, traffic calming measures, such as speed bumps and pedestrian crossings, should be implemented on pathways frequently used by children for their daily journeys to and from school. | ||

| C5 Traffic Environment | The activity area should be free of large vehicle crossings, and pedestrian pathways should be smooth, without steep slopes or deep pits. | ||

| C6 Video Surveillance | Security cameras and protective facilities should be installed in children’s activity areas to reduce parental concerns about safety and facilitate independent activities for children. | ||

| C7 Night lighting | Rural public spaces should have barrier-free facilities to provide easy access for young children and children with disabilities. | ||

| B2 Accessibility | C8 Ease of Route | The distance for children to walk to rural activity areas should not be too far, and the routes should be straightforward and easy to remember. | |

| C9 Travel Distance | Public spaces should be well-distributed and reasonably located to ensure suitable travel distances for children from different parts of rural areas, minimizing the time required for walking or cycling. | ||

| C10 Convenient Entry | Rural public spaces should have prominent entrance markers that attract children and facilitate easy access. | ||

| B3 Comfort | C11 Universal Access Facilities | Rural public spaces should include barrier-free facilities to ensure easy access and convenience for young children and children with disabilities. | |

| C12 Spatial Scale and Quality | The space should have an appropriate scale—neither too crowded nor too sparse—with adequate lighting, ventilation, and air quality. It should also offer a moderate level of enclosure and privacy. | ||

| C13 Facility Comfort and Convenience | Facilities should be arranged to facilitate ease of use by children, with dimensions suitable for their size, and forms and colors that are visually appealing to them. | ||

| C14 Environment Green and Comfortt | The overall environment, including color and shape, should align with children’s physiological and psychological needs. Plantings should display distinct seasonal changes, and the choice of trees, flowers, and greenery should enhance aesthetic appeal. | ||

| B4 Multifunctionality | C15 Activity Diversity and Engagement | Provide a wide range of play facilities to accommodate diverse activity needs. | |

| C16 Social Interaction Function | Facilitate interactive games such as hide-and-seek and jump rope, as well as various parent–child activities, to develop children’s social skills and teamwork abilities. | ||

| C17 Physical Fitness Function | Enable children to participate in physical activities such as jump rope, shuttlecock kicking, skateboarding, basketball, badminton, and table tennis within rural public spaces. | ||

| C18 Science and Educational Function | Include areas such as children’s reading rooms or parent–child reading zones; rural public spaces should support activities that promote learning about traditional culture, agricultural knowledge, and other intangible cultural heritage. | ||

| C19 Creativity and Innovation Function | The design and layout of rural activity spaces should foster children’s natural curiosity and energy, providing opportunities for exploring nature, enhancing creativity, and showcasing artistic talents. |

| A | B1 | B2 | B3 | … | Bn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | B1/B1 | B1/B2 | B1/B3 | … | B1/Bn |

| B2 | B2/B1 | B2/B2 | B2/B3 | … | B2/Bn |

| B3 | B3/B1 | B3/B2 | B3/B3 | … | B3/Bn |

| … | … | … | … | … | … |

| Bn | Bn/B1 | Bn/B2 | B6/B3 | … | Bn/Bn |

| Scale aij | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1 | Element i is as important as element j |

| 3 | Element i is slightly more important than element j |

| 5 | Element i is significantly more important than element j |

| 7 | Element i is very much more important than element j |

| 9 | Element i is extremely more important than element j |

| from the bottom (lines on a page) | If element j is compared with element i, the judgement value is the inverse of the above scale |

| A | B1 Safety | B2 Accessibility | B3 Comfortability | B4 Multifunctionality | Weights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 Safety | 1 | 4.077 | 3.454 | 2.333 | 0.4937 |

| B2 Accessibility | 0.245 | 1 | 3.625 | 1.333 | 0.2285 |

| B3 Comfortability | 0.289 | 0.276 | 1 | 0.600 | 0.1023 |

| B4 Multifunctionality | 0.429 | 0.750 | 1.667 | 1 | 0.1755 |

| λmax = 4.201, CR = 0.075, CR < 0.1, satisfy consistency test | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, J.; Zheng, B.; Liu, J.; Tian, F.; Sun, Z. Research on Child-Friendly Evaluation and Optimization Strategies for Rural Public Spaces. Buildings 2024, 14, 2948. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14092948

Fan J, Zheng B, Liu J, Tian F, Sun Z. Research on Child-Friendly Evaluation and Optimization Strategies for Rural Public Spaces. Buildings. 2024; 14(9):2948. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14092948

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Jia, Bohong Zheng, Junyou Liu, Fangzhou Tian, and Zhaoqian Sun. 2024. "Research on Child-Friendly Evaluation and Optimization Strategies for Rural Public Spaces" Buildings 14, no. 9: 2948. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14092948

APA StyleFan, J., Zheng, B., Liu, J., Tian, F., & Sun, Z. (2024). Research on Child-Friendly Evaluation and Optimization Strategies for Rural Public Spaces. Buildings, 14(9), 2948. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14092948