Research on Vehicle Fatigue Load Spectrum of Highway Bridges Based on Weigh-in-Motion Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Vehicle Load Data Analysis

2.1. Vehicle Classification

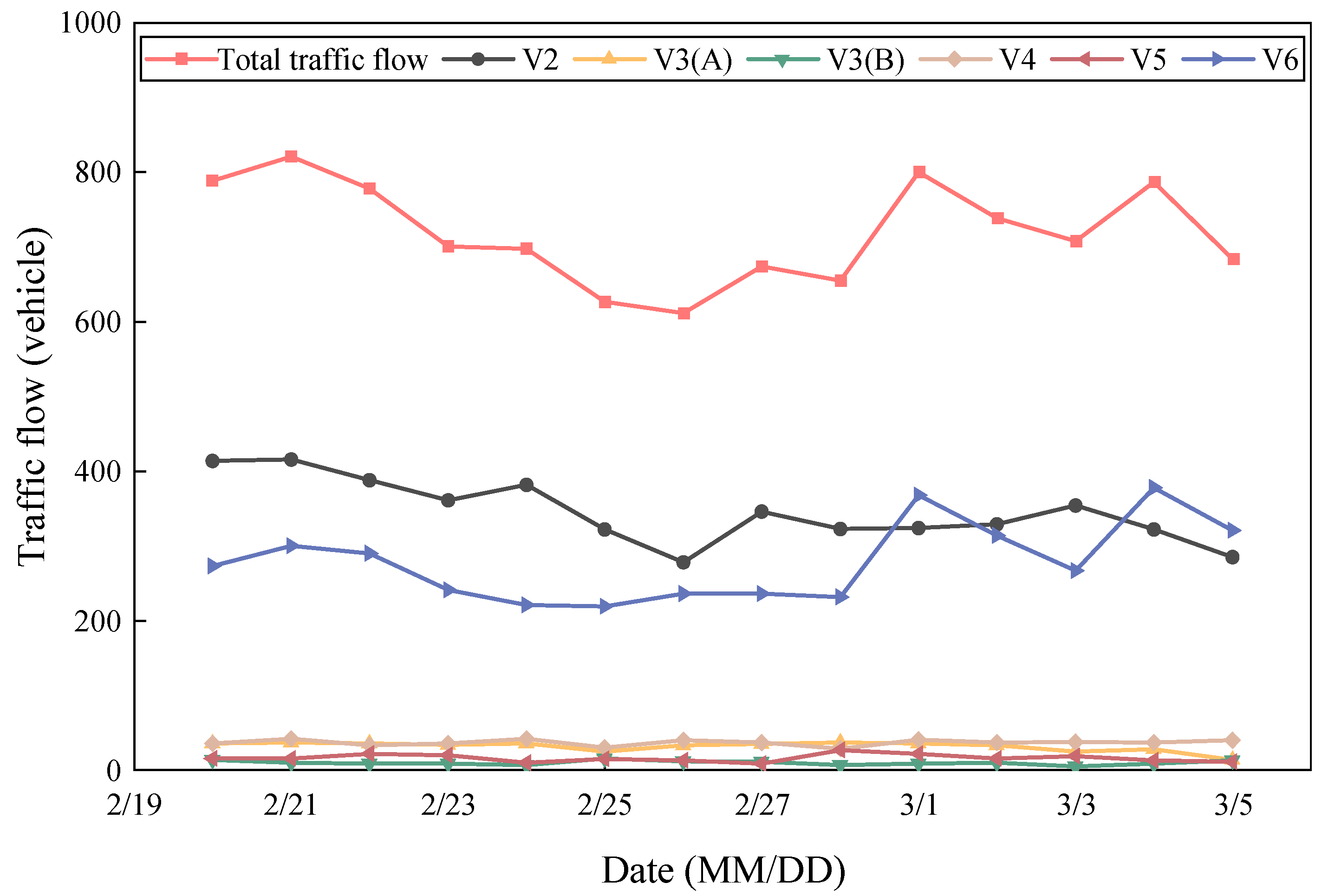

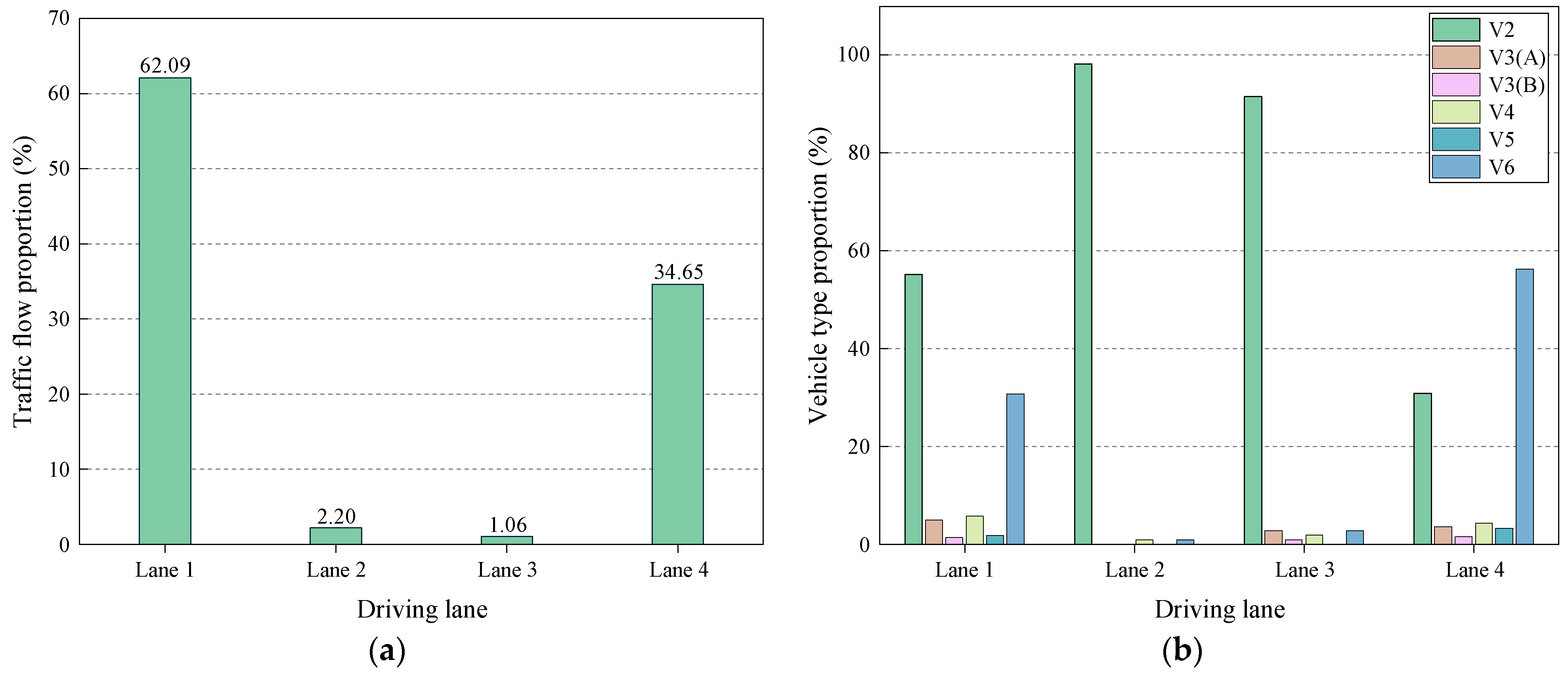

2.2. Traffic Flow Statistics

3. Statistical Parameters of Vehicle Load

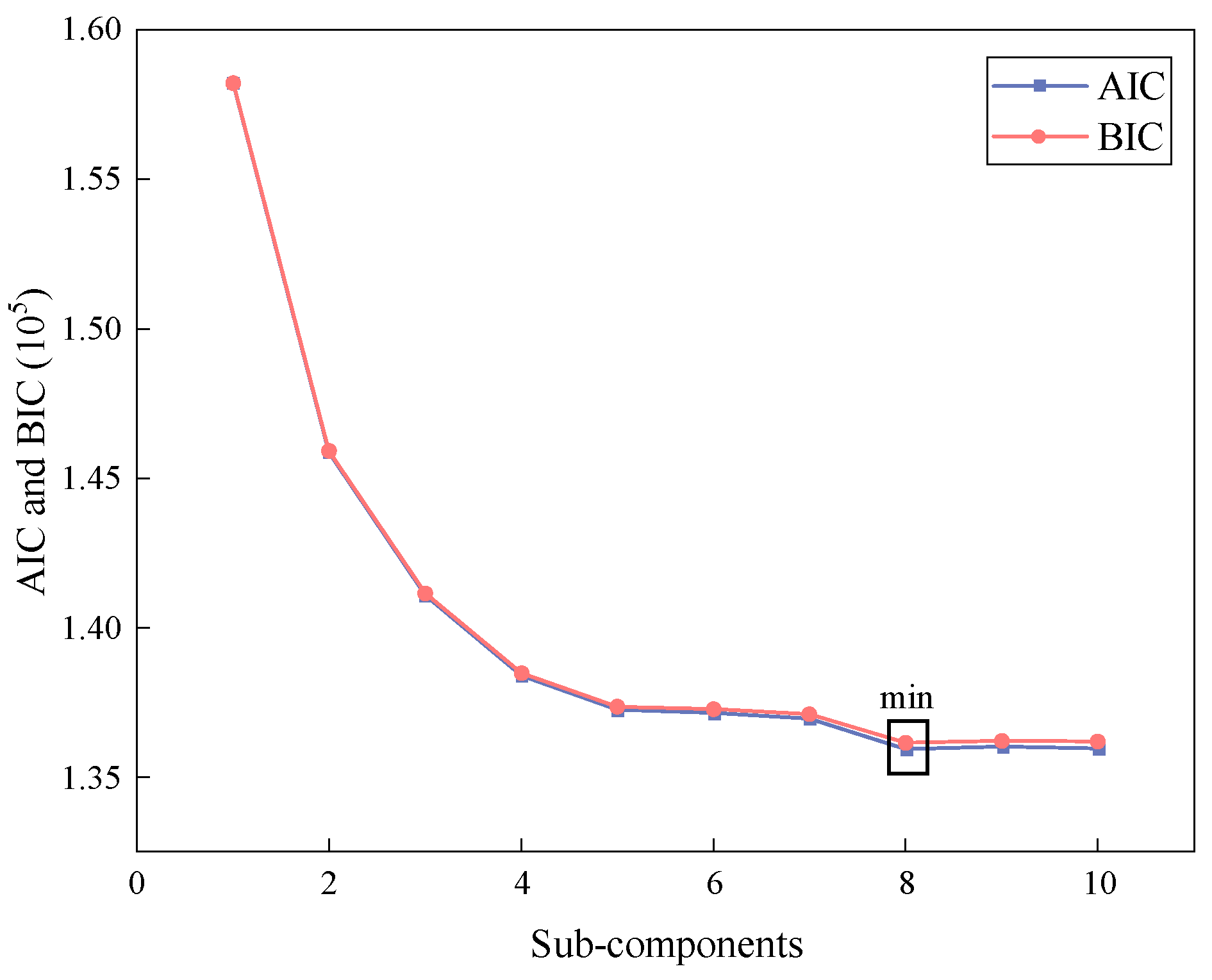

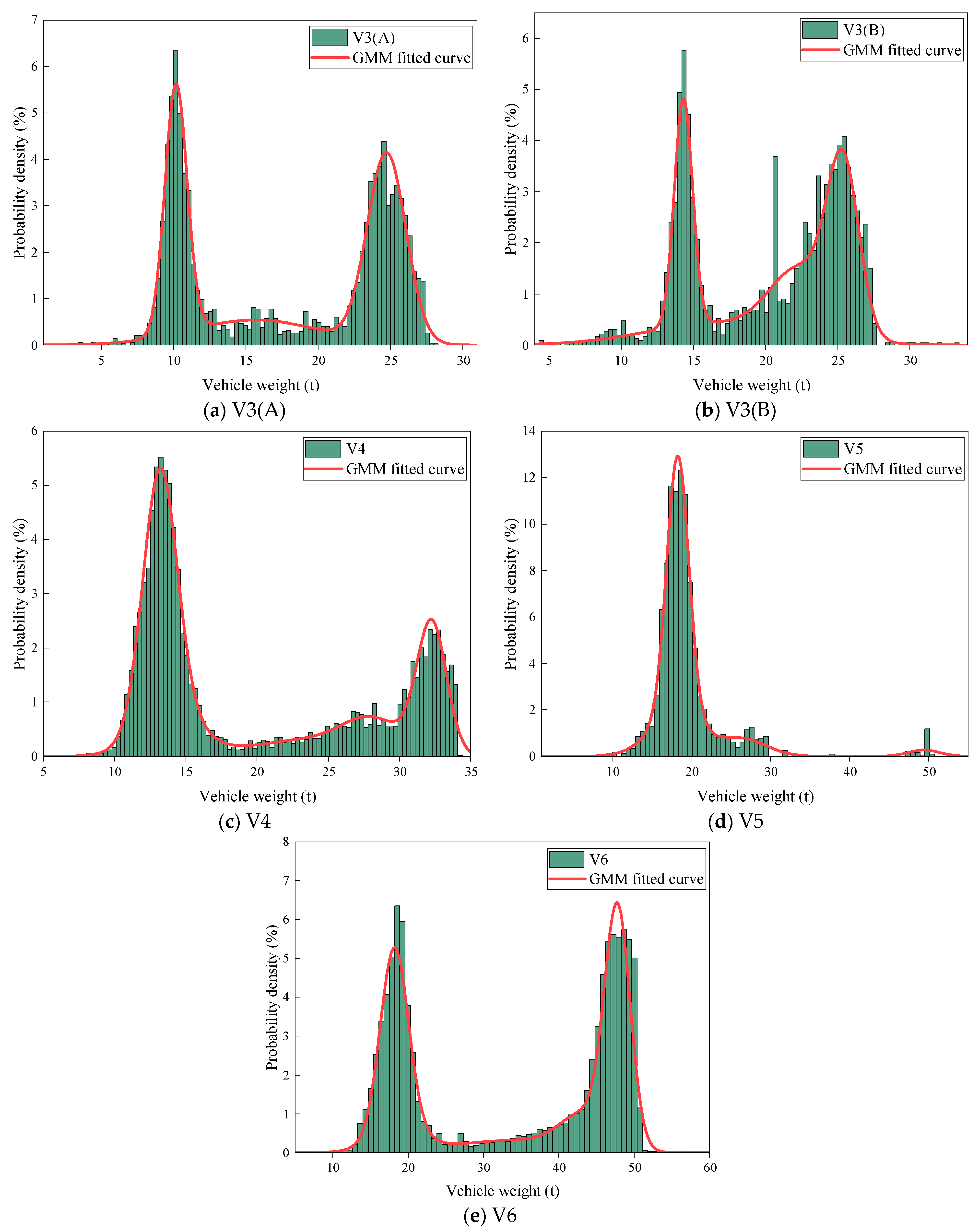

3.1. Vehicle Weight

3.2. Headway Time

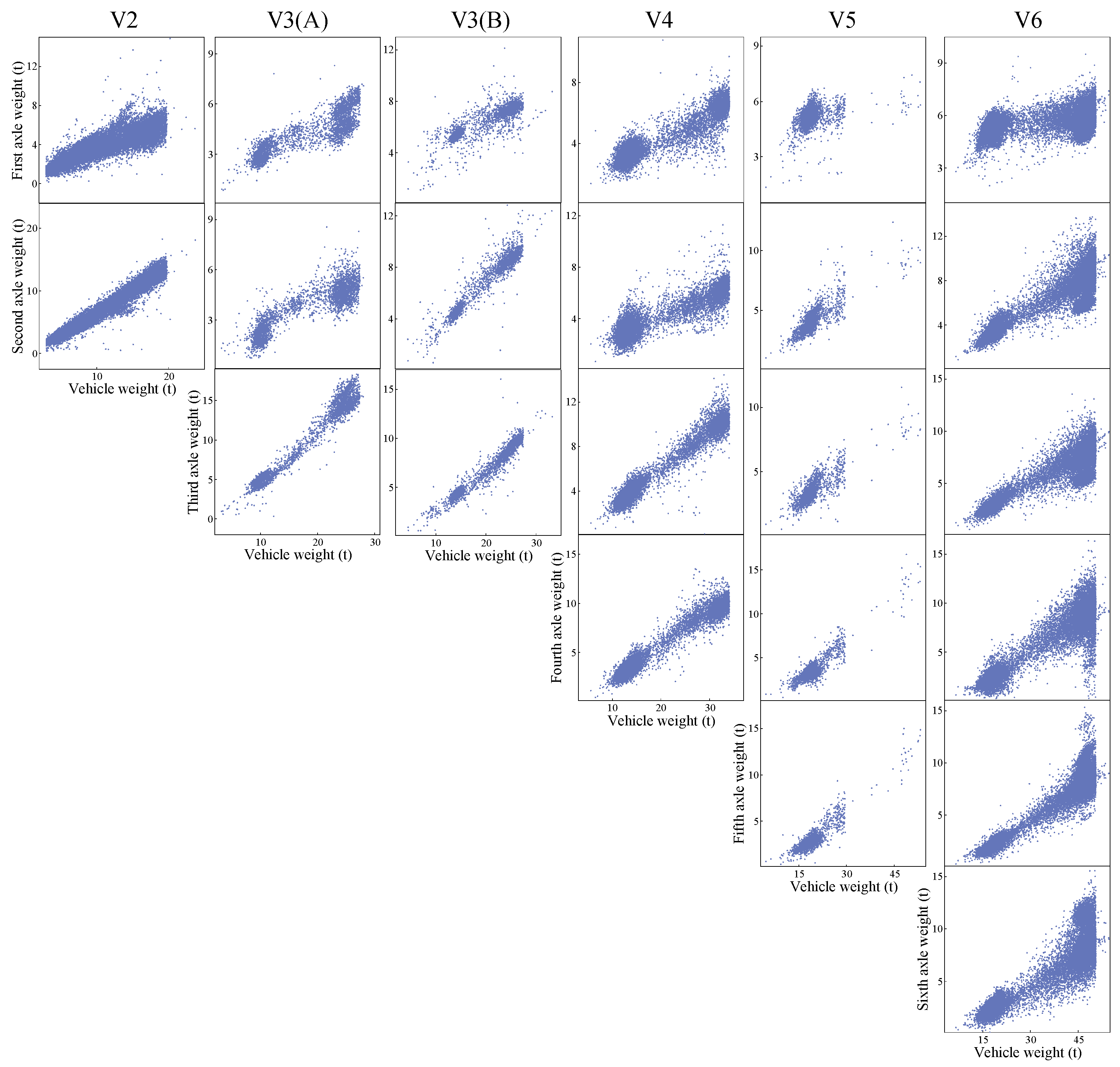

3.3. Axle Load and Wheelbase

4. Analysis of Vehicle Fatigue Load Spectrum

4.1. Vehicle Fatigue Load Spectrum

4.2. Fatigue Damage Contribution

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- In the traffic flow of vehicles crossing the bridge, the numbers of truck type V2 and truck type V6 account for a larger proportion compared to other vehicle types, with proportions of 40.39% and 31.04%, respectively. Additionally, the distribution of vehicle loads across different lanes is significantly imbalanced, with lanes 1 and 4 having a much higher traffic volume than lanes 2 and 3.

- (2)

- The weight probability density distributions of each truck exhibit a multi-modal pattern. Thus, a GMM was introduced, with the optimal number of sub-components determined using the AIC and the BIC. The results indicate that the weight probability density distributions of truck types V2 to V6 follow Gaussian mixture distributions, which were also validated through the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Additionally, the headway time distribution for lanes 1 and 4 can be characterized by a log-normal distribution, and the relationship between axle weight and total vehicle weight for each truck model can be described using a linear regression model.

- (3)

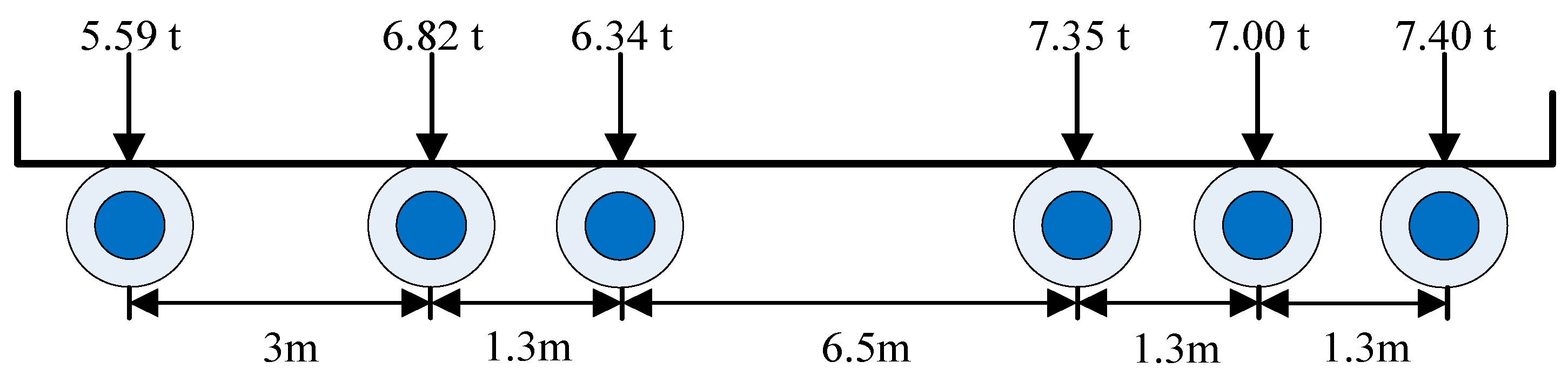

- The vehicle fatigue load spectrum reveals that the equivalent vehicle weight for all truck models is greater than 10 t. Among them, truck type V2 has the lowest equivalent weight at 11.58 t, while truck type V6 has the highest equivalent weight at 40.50 t. Additionally, the equivalent vehicle weight tends to increase with the number of axles.

- (4)

- By calculating the fatigue damage contribution of each axle for each vehicle, it was found that although truck type V2 has the highest frequency, truck type V6 has the greatest fatigue damage contribution to the bridge, accounting for 53.81%. Therefore, based on the vehicle fatigue load spectrum and fatigue damage contribution, it is recommended to select the six-axle truck as the standard fatigue vehicle for this highway.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, M.; Huang, T.L.; Liao, J.J.; Zhong, J.; Zhong, J.W. WIM-Based Vehicle Load Models for Urban Highway Bridge. Lat. Am. J. Solids Strut. 2020, 17, e290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Xiong, F. Study of a Fatigue Load Model for Highway Bridges in Southeast China. J. Croat. Assoc. Civ. Eng. 2020, 72, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujon, M.; Dai, F. Application of Weigh-in-Motion Technologies for Pavement and Bridge Response Monitoring: State-of-the-Art Review. Autom. Constr. 2021, 130, 103844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, T.; Deng, L.; He, W.; Cao, R.; Zhong, W. Determination of Dynamic Amplification Factors for Small- and Medium-Span Highway Bridges Considering the Effect of Automated Truck Platooning Loads. Mech. Syst. Sig. Process. 2023, 204, 110812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonari, S.; Nicoletti, V.; Martini, R.; Gara, F. Dynamics of Bridges during Proof Load Tests and Determination of Mass-Normalized Mode Shapes from OMA. Eng. Struct. 2024, 310, 118111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, B.; Bursi, O.S.; Casciati, F.; Casciati, S.; Del Grosso, A.E.; Domaneschi, M.; Faravelli, L.; Holnicki-Szulc, J.; Irschik, H.; Krommer, M.; et al. A European Association for the Control of Structures Joint Perspective. Recent Studies in Civil Structural Control across Europe: Recent Studies in Civil Structural Control Across Europe. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2014, 21, 1414–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Lugo, M.A.; Nogal, M.; Morales-Nápoles, O. Estimating Bridge Criticality Due to Extreme Traffic Loads in Highway Networks. Eng. Struct. 2024, 300, 117172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agüero-Barrantes, P.; Lobo-Aguilar, S.; Hain, A.; Christenson, R.E. Exploring Kriging Metamodeling to Alleviate Speed Reading Dependence in Bridge Weigh-In-Motion Predictions. Structures 2024, 68, 107086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, C.G.; Klippstein, K.H. New Method for Fatigue Design of Bridges. J. Struct. Div. 1978, 104, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.R.; Mohseni, M.; Lashgari, M. Reliability Evaluation of Axially Loaded Steel Members Design Criteria in AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Code. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2013, 116, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, C.; OBrien, E.J.; Enright, B.; Hajializadeh, D. Review of HL-93 Bridge Traffic Load Model Using an Extensive WIM Database. J. Bridge Eng. 2015, 20, 04014115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Spuy, P.; Lenner, R. Towards a New Bridge Live Load Model for South Africa. Struct. Eng. Int. 2019, 29, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wang, K.; Yang, Q.; Xu, B.; Di, J. Fatigue Load Model of Orthotropic Steel Deck for Port Highway in China. Front. Mater. 2023, 10, 1115632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, N. Fatigue Load Model Using the Weigh-in-Motion System for Highway Bridges in China. J. Bridge Eng. 2017, 22, 04017011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, L.; Xiaoyu, X.; Xueyan, D. Fatigue Load Spectrum of Highway Bridge Vehicles in Plateau Mountainous Area Based on Wireless Sensing. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2021, 2021, 9955988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Deng, Y. Vehicle Load Spectrum and Fatigue Vehicle Model of a Long-Span Concrete-Filled Steel Tube (CFST) Arch Bridge Based on Measured Data of Weight-In-Motion System. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 3092579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhong, Z.; Xie, X.; Lu, P. Measurement-Based Vehicle Load Model for Urban Expressway Bridges. Math. Probl. Eng. 2014, 2014, 340896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Chang, W.; Li, F. Development of Standard Fatigue Vehicle Force Models Based on Actual Traffic Data by Weigh-In-Motion System. J. Test. Eval. 2017, 45, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Ye, Z.; Chen, Z.; Xie, X. Bridge Vehicle Load Model on Different Grades of Roads in China Based on Weigh-in-Motion (WIM) Data. Measurement 2018, 122, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Xu, S.; Wang, D.; Chen, A. Vehicle Models for Fatigue Loading on Steel Box-Girder Bridges Based on Weigh-in-Motion Data. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2018, 14, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasni, H.; Jiao, P.; Alavi, A.H.; Lajnef, N.; Masri, S.F. Structural Health Monitoring of Steel Frames Using a Network of Self-Powered Strain and Acceleration Sensors: A Numerical Study. Autom. Constr. 2018, 85, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paepegem, W.V.; Degrieck, J. Effects of Load Sequence and Block Loading on the Fatigue Response of Fibre-Reinforced Composites. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2002, 9, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F.; Jacob, B.; Domprobst, F. Investigation of Truck Weights and Dimensions Using WIM Data. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, R.; Barabino, B.; Vetturi, D.; Maternini, G. Monitoring Vehicles with Permits and That Are Illegally Overweight on Bridges Using Weigh-In-Motion (WIM) Devices: A Case Study from Brescia. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2023, 13, 101023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akalke, H. A New Look at the Statistical Model Identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. Wind-Vehicle-Bridge Coupled Vibration Analysis Based on Random Traffic Flow Simulation. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2014, 1, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vehicle Type Number | Vehicle Type | Schematic Diagram | Amounts | Percentage/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V2 | Two-axle truck |  | 26,010 | 40.39 |

| V3(A) | Three-axle truck |  | 3962 | 6.15 |

| V3(B) | Three-axle truck |  | 2718 | 4.22 |

| V4 | Four-axle truck |  | 9252 | 14.37 |

| V5 | Five-axle truck |  | 2468 | 3.83 |

| V6 | Six-axle truck |  | 19,987 | 31.04 |

| Vehicle Type Number | Probability Distribution Function | Distribution Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| V2 | Eight-component Gaussian mixture model | , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , |

| V3(A) | Three-component Gaussian mixture model | , , , , , , |

| V3(B) | Four-component Gaussian mixture model | , , , , , , , , |

| V4 | Five-component Gaussian mixture model | , , , , , , , , , , |

| V5 | Four-component Gaussian mixture model | , , , , , , , , |

| V6 | Five-component Gaussian mixture model | , , , , , , , , , , |

| Vehicle Type Number | Axle 1 | Axle 2 | Axle 3 | Axle 4 | Axle 5 | Axle 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ai1 | bi1 | ai2 | bi2 | ai3 | bi3 | ai4 | bi4 | ai5 | bi5 | ai6 | bi6 | |

| V2 | 0.28 | 0.74 | 0.72 | −0.74 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| V3(A) | 0.16 | 1.27 | 0.15 | 1.03 | 0.69 | −2.30 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| V3(B) | 0.20 | 2.46 | 0.37 | −0.61 | 0.43 | −1.85 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| V4 | 0.16 | 1.08 | 0.17 | 0.86 | 0.34 | −0.80 | 0.33 | −1.14 | - | - | - | - |

| V5 | 0.04 | 4.45 | 0.19 | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.31 | −2.40 | 0.29 | −2.55 | - | - |

| V6 | 0.02 | 4.69 | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.16 | −0.08 | 0.22 | −1.62 | 0.22 | −1.77 | 0.22 | −1.53 |

| Vehicle Type Number | Vehicle Weight/t | Equivalent Axle Weight/t | Wheelbase/m | Frequency/% | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axle 1 | Axle 2 | Axle 3 | Axle 4 | Axle 5 | Axle 6 | Axle 1~2 | Axle 2~3 | Axle 3~4 | Axle 4~5 | Axle 5~6 | |||

| V2 | 11.58 | 3.99 | 7.59 | - | - | - | - | 4.00 | - | - | - | - | 40.39 |

| V3(A) | 19.90 | 4.44 | 4.04 | 11.42 | - | - | - | 1.90 | 5.30 | - | - | - | 6.15 |

| V3(B) | 22.23 | 6.89 | 7.65 | 7.69 | - | - | - | 3.50 | 1.30 | - | - | - | 4.22 |

| V4 | 23.61 | 4.77 | 4.86 | 7.15 | 6.82 | - | - | 2.00 | 5.50 | 1.30 | - | - | 14.37 |

| V5 | 22.60 | 5.23 | 4.53 | 3.88 | 4.72 | 4.25 | - | 3.00 | 6.00 | 1.30 | 1.30 | - | 3.83 |

| V6 | 40.50 | 5.59 | 6.82 | 6.34 | 7.35 | 7.00 | 7.40 | 3.00 | 1.30 | 6.50 | 1.30 | 1.30 | 31.04 |

| Vehicle Type Number | Number of Axles | Fatigue Damage Contribution/% | Number of Vehicles | Frequency/% | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle Weight | Axle 1 | Axle 2 | Axle 3 | Axle 4 | Axle 5 | Axle 6 | ||||

| V2 | 2 | 18.55 | 2.35 | 16.21 | - | - | - | - | 26,010 | 40.39 |

| V3(A) | 3 | 9.26 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 8.40 | - | - | - | 3962 | 6.15 |

| V3(B) | 3 | 4.75 | 1.27 | 1.73 | 1.76 | - | - | - | 2718 | 4.22 |

| V4 | 4 | 11.95 | 1.43 | 1.51 | 4.82 | 4.19 | - | - | 9252 | 14.37 |

| V5 | 5 | 1.67 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.20 | 0.37 | 0.27 | - | 2468 | 3.83 |

| V6 | 6 | 53.81 | 4.98 | 9.01 | 7.25 | 11.28 | 9.76 | 11.54 | 19,987 | 31.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, R.; Xie, G.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, H.; Wu, C.; Liu, H. Research on Vehicle Fatigue Load Spectrum of Highway Bridges Based on Weigh-in-Motion Data. Buildings 2025, 15, 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15050675

Feng R, Xie G, Zhang Y, Kong H, Wu C, Liu H. Research on Vehicle Fatigue Load Spectrum of Highway Bridges Based on Weigh-in-Motion Data. Buildings. 2025; 15(5):675. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15050675

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Ruisheng, Guilin Xie, Youjia Zhang, Hu Kong, Chao Wu, and Haiming Liu. 2025. "Research on Vehicle Fatigue Load Spectrum of Highway Bridges Based on Weigh-in-Motion Data" Buildings 15, no. 5: 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15050675

APA StyleFeng, R., Xie, G., Zhang, Y., Kong, H., Wu, C., & Liu, H. (2025). Research on Vehicle Fatigue Load Spectrum of Highway Bridges Based on Weigh-in-Motion Data. Buildings, 15(5), 675. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15050675