Abstract

Air conditioning is the most common and efficient measure against summer heat. However, overcooling issues exist widely in well-conditioned buildings, and the health risks and causes require further exploration. This study aims to rethink the indoor environment control and demand in hot summer from a novel perspective of yin summer-heat in traditional Chinese medicine. The core idea was to reflect health risks embodied in the indoor environment control that was oriented by the average comfort zone in air-conditioned buildings. Three research questions were explored, namely, indoor–outdoor environment features in hot summer, the heterogeneity of demands and behaviors, and relationships between personal attributes and lifestyles. Eleven field tests were conducted in residential buildings, together with experiments in an office building and three questionnaire surveys with 765 responses from 2020 to 2023 in China. Results showed that notable indoor–outdoor environment gaps appeared due to air conditioning. Yin summer-heat symptoms, such as a heavy feeling in the body, were reported by individuals of vulnerable constitutions even in neutral air-conditioned environments. In addition, Chinese medicine theories, including pathogenic factors, constitutions, and health preservation principles, worked well to interpret diverse environment perceptions, demands, and adaptive behaviors. These findings will add to the scientific basis of wellbeing in indoor environments.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Increasing Usage of Air Conditioners and the Narrowing Comfort Zone

Climate change has permanently changed summer characteristics, with extreme heat events occurring globally from tropical to temperate climates. Almost half of the global population are exposed to extreme heat currently [1]. Hot ambient temperature and associated heat stress can increase mortality and morbidity [2], e.g., causing cardiovascular, respiratory, cerebrovascular, and endocrine diseases, etc., in addition to heat-related illness [1,3]. Moreover, recent studies highlighted the significant impact of heat stress on human mental health, including an increased suicide rate with high temperature [4], anxiety disorders in hot and humid environments (mouse experiment) [5], and less perceived happiness on hot days [6].

Globally, space cooling has been one of the fastest-growing end-uses in recent years against such hot summers [7,8]. However, long-term AC use reduces occupants’ thermal adaptability, leading to a preference for lower temperatures and a relatively stable environment. Alnuaimi et al. [9] carried out a large-scale study based on a global database including over 90 thousand responses from 27 countries in warm climates across thirty years. It was found that 17% of the occupants were overcooled according to their TSVs (Thermal Sensation Votes) and TP (Thermal Preference). The comfort temperature was 22~25 °C and the observed temperature was lower by 0.4~3.0 °C in summer. “Well-conditioned” buildings enable a tight control of indoor climate, where occupants become less tolerant of discomfort, compared with naturally ventilated buildings. A field study in Brazil with 20 university students [10] showed that occupants with air conditioning exposure preferred cooler environment, though their TSV was similar to those without, even at an indoor temperature of 24.5 °C. A field study in China [11] examined the neutral temperature of naturally ventilated (NV) and split air-conditioned (SAC) buildings based on 465 and 345 responses from healthy students. The NV group had a higher neutral temperature of 26.2 °C, compared to 25.5 °C of the SAC group. A large-scale study in Australia [12] analyzed occupant’s thermal sensitivity using the Griffith Constant, i.e., a coefficient of changes in TSV by temperature, based on 11,500 samples in different types of buildings. The G value of occupants in naturally ventilated spaces (0.208/°C) was about half of those in air-conditioned environments (0.440/°C), indicating less sensitivity to indoor thermal environments.

In addition, more exposure to HVAC systems suggests higher thermal expectations. A 15-month field measurement with 41 Australian households [13] found that heavy users (over 500 h annual HVAC system usage) maintained a significantly higher temperature in winter in the bedroom (20.9 °C, 0.6 °C higher) and living room (21.4 °C, 1.4 °C higher) than medium or light users. A field study in Brazil [14] with over 3000 responses in naturally ventilated classrooms (air temperature 26.9~31.6 °C) had similar findings. Students who routinely spend over 12 h per day in an air-conditioned environment reported the most warm or hot feelings (41%) and strongest needs for cooling (78%), compared with less exposed or unexposed students. A climate chamber study [15] investigated the physiological acclimation of 60 healthy young people when the temperature ranged within 20~32 °C and the humidity was suitable. Half of the participants were from central air-conditioned (CAC) buildings and the other half from SAC buildings. The CAC group reported a significantly higher mean skin temperature under the non-neutral conditions than the SAC group. Also, the 90% acceptable standard effective temperature (SET) was 24.8~27.4 °C and 24.4~30.1 °C for the CAC and SCA groups, with the range of the SAC group being wider by 3.1 °C.

As pointed out by de Dear [16], the comfort zone has become progressively narrower over the past seven decades. Short-term and long-term thermal experiences vary from seconds to years, impacting thermal sensation, comfort, acceptability, and expectations in different manners [17]. Individuals would easily and quickly improve their thermal expectations but take more effort to lower them, as found by a study with people with varied long-term thermal experiences in China [18]. Prolonged exposure to a stably cool indoor environment would restrain humans’ adaptive capacity, while a dynamic environment was more beneficial [17]. Thus, a more relaxed thermal comfort zone is called for, as it was in the adaptive model in ASHRAE Standard 55 since 2004 version [16], to encourage more climate-adaptive practices. Therefore, the narrowing thermal comfort zone has led to a preference for prolonged stays in air-conditioned environments, and the associated health risks have increasingly become a focus of research attention.

1.2. Health Risks Associated with Air-Conditioned Environments

Escalating health risks are associated with such air-conditioned environments due to their stable indoor conditions. Despite diseases caused by polluted AC systems and air contaminants [19,20], studies since the 2000s have found that sickness symptoms still appear in non-problem AC buildings, with a higher prevalence than NV buildings. For example, Muzi et al. [21] compared self-reported irritative symptoms of 198 and 281 employees in AC and NV buildings in Italy and found more ocular, upper airway, and cutaneous symptoms in the AC than NV group, with 29.8% (AC) and 14.9% (NV), 25.3% and 9.6%, and 14.1% and 3.6% for the three symptoms, respectively. Wong and Huang [22] investigated the bedroom environment of three residential buildings and SBS symptoms of 105 occupants in Singapore. Occupants sleeping with operating air conditioners mostly presented SBS symptoms. Also, more symptoms appeared when they turned from NV to AC. Cao et al. [23] examined twelve categories of discomfort related to neural, digestive, and respiratory systems, and the skin and mucous membranes of 2595 responses in China. Significant differences were found in the prevalence of certain symptoms among people exposed to an air-conditioned environment for different hours per day. Unsurprisingly, overcooling and sickness issues exist in buildings at the same time. A field test [24] with eleven office buildings and 599 occupants in Thailand, Indonesia, and Singapore during 2017 to 2018 found that the mean operative temperatures were all lower than 24 °C indoors. Self-reported symptoms, such as headache and fatigue in the body, were most severe and gentle at an operative temperature of 21.0 °C and 24.5 °C.

Interdisciplinary exploration has provided medical evidence on the working mechanism of indoor thermal environment factors on human health. A comprehensive review by Liu et al. [25] showed that temperature was the most important and frequently discussed factor, followed by humidity and air movement, which were associated with SBS, metabolic symptoms, and respiratory diseases. Chamber tests with 20 people [26] found that the NV group presented stronger physiological regulatory capacity for heat shock from 26 to 36 °C, particularly showing a more rapid skin temperature response, a lower “chest–feet ΔT”, a higher volume of sweat, a smaller rise in HRV (Heart Rate Variability), and a higher level of HSP70 (Heat Stress Protein 70) than the AC group. In addition, experiments with 26 healthy subjects at ambient temperatures of 24 °C and 28 °C and air velocities of 0 m/s and 1 m/s [27] displayed that cold draft would restrain upper respiratory mucosal immunity. In particular, the concentration of secretory immunoglobulin A (S-lgA) remained low after one day in the 24 °C and 1 m/s case, indicating a prolonged adverse impact.

Health risks also exist for temperature steps or sudden temperature changes, which are quite common in indoor–outdoor space switching. A climate chamber study with 16 persistent allergic rhinitis patients and 16 control subjects in Brazil [28] found that the former were more susceptible to the sudden temperature change of 14 → 26 °C. Another laboratory experiment in China [29] with 24 subjects exposed to temperature step changes between 32 and 37 °C, 26 and 37 °C, and 22 and 37 °C reported a notable shrink in perspiration at sudden temperature drops of 12 and 15 °C. A list of biomarkers were found to reflect the impact of sudden temperature changes on human immune, thermal metabolism, respiratory, and cardiovascular systems [30], including interleukin-6 (IL-6), oral and skin temperature, heart rate, and heart rate variability. Also, a significant and strong correlation existed between such physiological parameters and self-reported symptoms.

1.3. “Yin Summer-Heat” Perspective in Traditional Chinese Medicine

Evidently, reliance on or even “addiction” to air conditioning not only increases energy use in buildings but also leads to the sickness of occupants. How, then, should we manage indoor comfort needs and maintain the health of occupants in air-conditioned buildings? It is not easy to answer this question, since a large number of variables are involved, which are coupled in a complex manner and present varied features in different time scales. The “yin summer-heat” concept in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) may help with this question.

The idea of cold-induced illness in hot summer, i.e., “yin” symptoms in TCM, were proposed by Jiegu Zhang (Jin Dynasty, 1131~1234), which were common among inactive people who got away from hot weather inside massive buildings, in comparison with heat-induced illness in summer, i.e., “yang” symptoms, for active people walking around outdoors. The expression of “yin summer-heat” was formally proposed by Jingyue Zhang (Ming Dynasty, 1563~1640) as typhoid in hot summer [31], which was common but quite covert.

Modern Chinese medicine interprets yin summer-heat from the perspective of chills in summer [32]. Clinical observations of 120 patients [33] confirmed that yin summer-heat illness was caused by the pathogenic factor of cold excess, usually combined with another pathogenic factor of dampness excess, resulting from overly taking cold drinks, shelter from the sun, etc. An epidemiological study of 203 patients with respiratory tract infections in summer in Beijing, China [32], showed that most patients usually caught a “cold” via air conditioners (152 ppl.), electric fans (11 ppl.), chill natural wind (16 ppl.), rain or shower (3 ppl.), or cold drinks (3 ppl.). The pathogenic factors could invade in two ways, i.e., from an external boundary such as the skin or the internal body such as organs, and induce different symptoms, e.g., fever, headache, anhidrosis, chills, and body aches, or vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain, respectively [34]. Such pathogenic factors and symptoms work well to explain discomfort feelings in air-conditioned environments [35]. Chinese medicine theories and methods, e.g., substantial classic prescriptions targeting summer heat [36], are advantageous to avoid and treat such yin summer-heat diseases. The classification of common yin summer-heat symptoms is elaborated in Table 1, together with a comparison of the concept, symptoms, and pathogens among building-related illness, SBS, and yin summer-heat illness.

Table 1.

Comparison of building-related illness, SBS, and yin summer-heat illness.

Furthermore, constitutions in Chinese medicine would help to understand individual differences in environmental adaptability, responses to the pathogenic factors, and potential symptoms in air-conditioned environments, when gender or age are not the only reasons for individual disparities in thermal comfort [38]. Constitutions in Chinese medicine comprise a scientific and systematic description of the physiological and mental conditions of an individual, considering physical characteristics, common manifestations, psychological features and symptoms, etc. The national standard (ZYYXH/T157-2009 [39]) stipulates a series of questions about health status to evaluate an individual’s constitution type. The questions adopted five-point Likert scales and the score of questions reflects one’s tendency toward certain constitutions. The segmentation of constitutions has been calibrated and validated by interdisciplinary epidemical studies with more than 129 thousand people [40]. As illustrated in Table 2, there are nine constitutions, indicating different environment and social adaptabilities. An individual of a certain constitution will be vulnerable to corresponding TCM pathogenic factors and get sick in a given environment.

Table 2.

Identification of nine constitutions in Chinese medicine and corresponding environment adaptabilities [39].

1.4. Research Aim

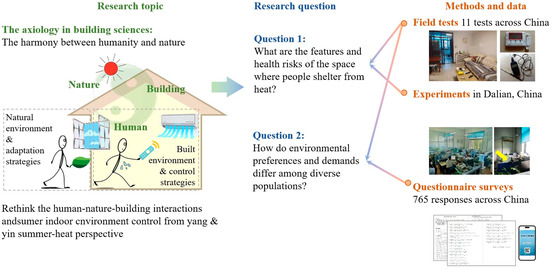

Continuous extreme heat has brought great challenges to human beings living on this planet. Existing studies have evidenced that long-term exposure in air-conditioned environments is associated with a series of health risks, including weakened environmental adaptability and building-related illness, or more specifically, overcooled symptoms. However, there has been limited exploration of the complex links between the sensation, adaptability, and symptoms of the occupants in air-conditioned environments. Also, the so-called comfort environment is not necessarily healthy for modern urbanites who live and will still live in such well-conditioned buildings. TCM concepts, including yin summer-heat illness, which is associated with occupant’s strong desire for cool feelings in hot summer (e.g., relying on air conditioners, cold showers, cold drinks, etc.), six pathogenic factors, and constitutions, could work well to explain the discomfort feelings and individual adaptability in air-conditioned environments. Therefore, this study aims to introduce the pathogenic factors and prevention strategies of “yin summer-heat” illness in masterpieces of Chinese medicine to rethink indoor environment control from the following aspects. Two questions are to be answered:

- Question 1: What are the features and health risks of the space where people shelter from heat?

- Question 2: How do environmental preferences and demands differ among diverse populations?

The findings of this study will facilitate human-centric demand-facing personalized indoor environment control strategies in hot summer.

2. Data and Method

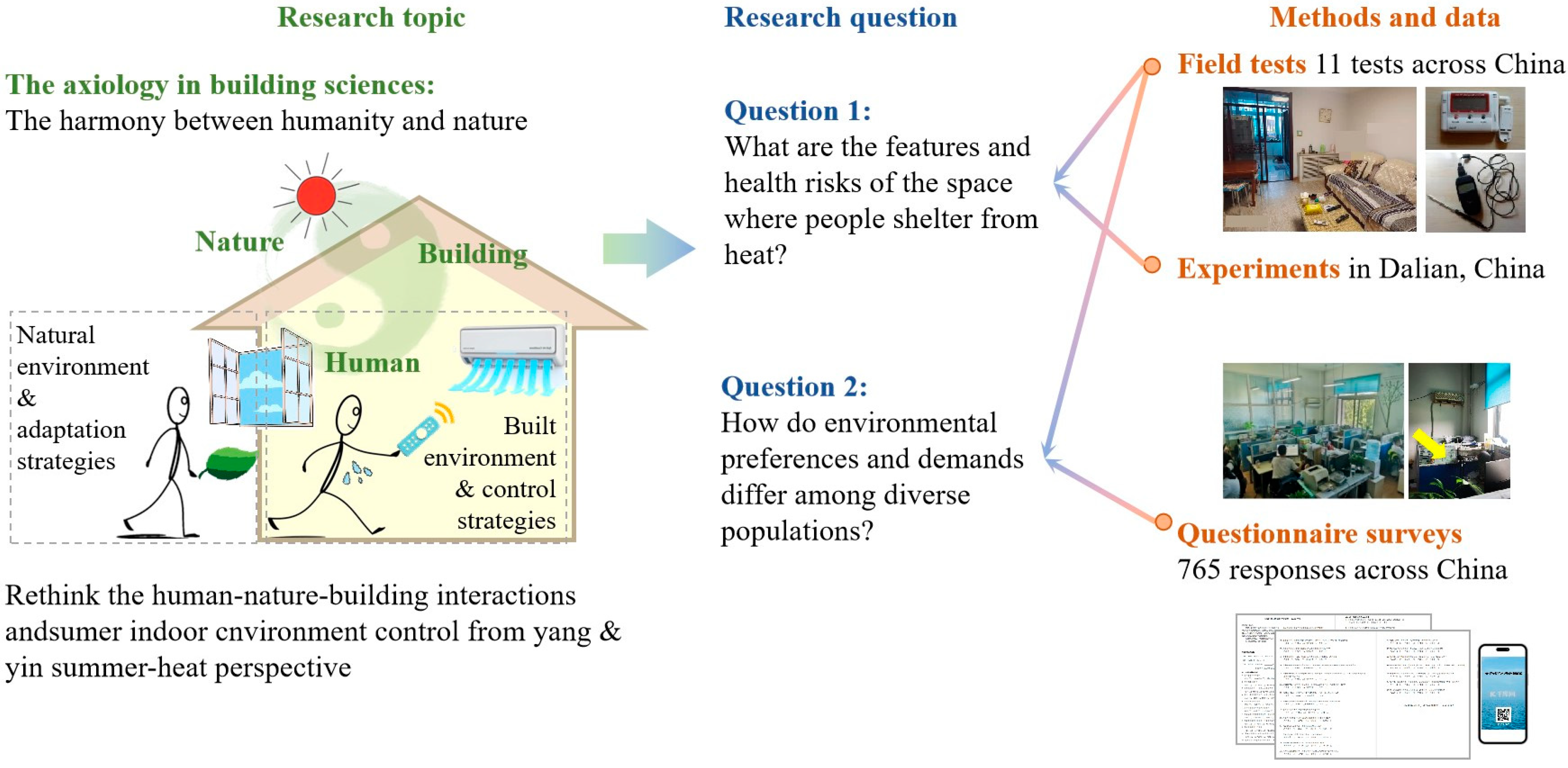

To answer the questions above, field tests and questionnaire surveys were carried out from 2020 to 2023, in typical subtropical or temperate climatic cities in China, to explore how buildings and occupants adapt to or get rid of hot summer and potential health risks. In particular, this study did not manage to cover all disparities induced by geographical or demographic heterogeneity, but tried to point out and showcase the challenges faced by the “concrete forest” cooled down by numerous air conditioners in the modern city. The research framework of this study is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The research questions, methods, and data of this study (illustration by the authors).

2.1. Field Tests and In Situ Experiments

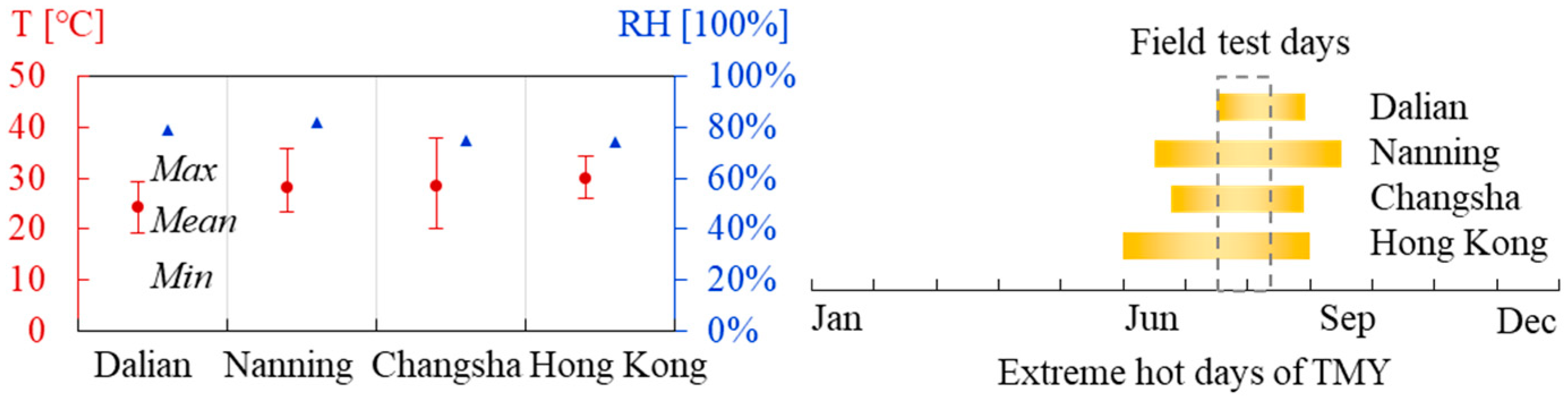

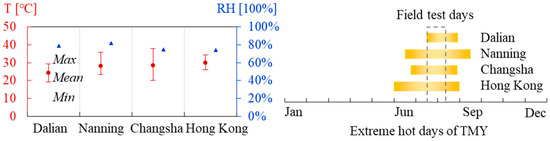

Eleven field tests were conducted in residential buildings to investigate the indoor and outdoor environment features in hot summer, as elaborated in Table 3. Participants of the field tests comprised young, middle-aged, and elderly people, who lived in Dalian, Nanning, Changsha, and Hong Kong in China. The participants maintained their lifestyles, including daily dress habits, during the tests. The monitoring in residential buildings lasted for three to fourteen days. All tests were conducted during extreme hot days of the year, with outdoor temperature and humidity being stably high, as shown in Figure 2. Existing studies showed that large temperature steps, low air humidity, and drafts appearing in the overcooled indoor environment, together with indoor–outdoor switching, would lead to discomfort feelings or illness of occupants [27,28,29,30,35]. Therefore, relevant indoor and outdoor environment parameters were obtained in the field tests. Thermal diaries and follow-up interviews were also applied to some participants to record their instant feelings and comments. In addition, the constitution of the participants of the field tests were identified. Typical meteorological year (TMY) data were also collected for targeted cities.

Table 3.

A summary of field tests and experiments during hot summer in 2020~2023 in China.

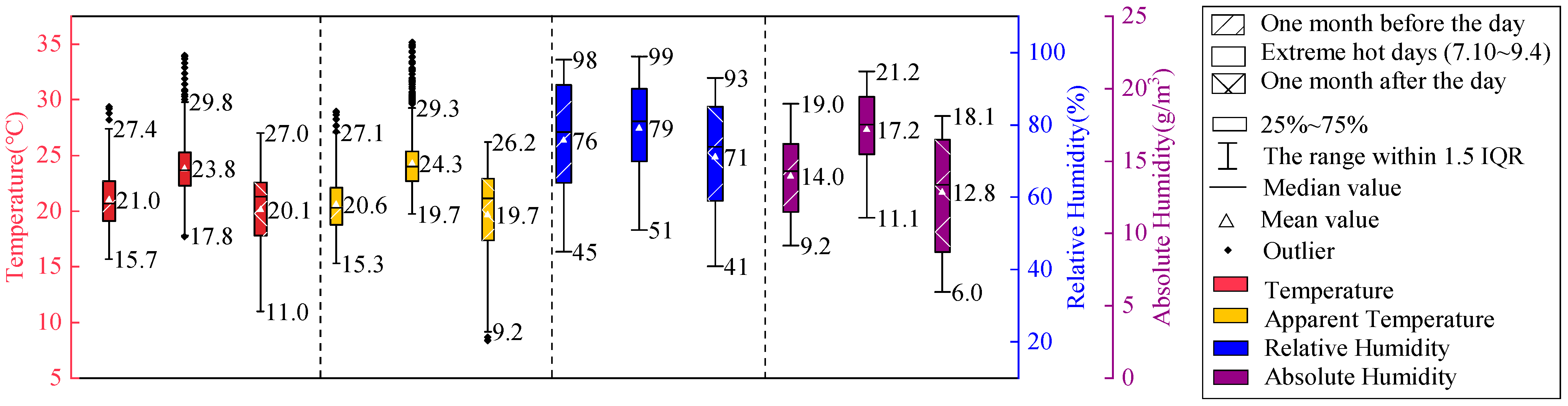

Figure 2.

Outdoor environment of extreme hot days in TMY of the targeted cities.

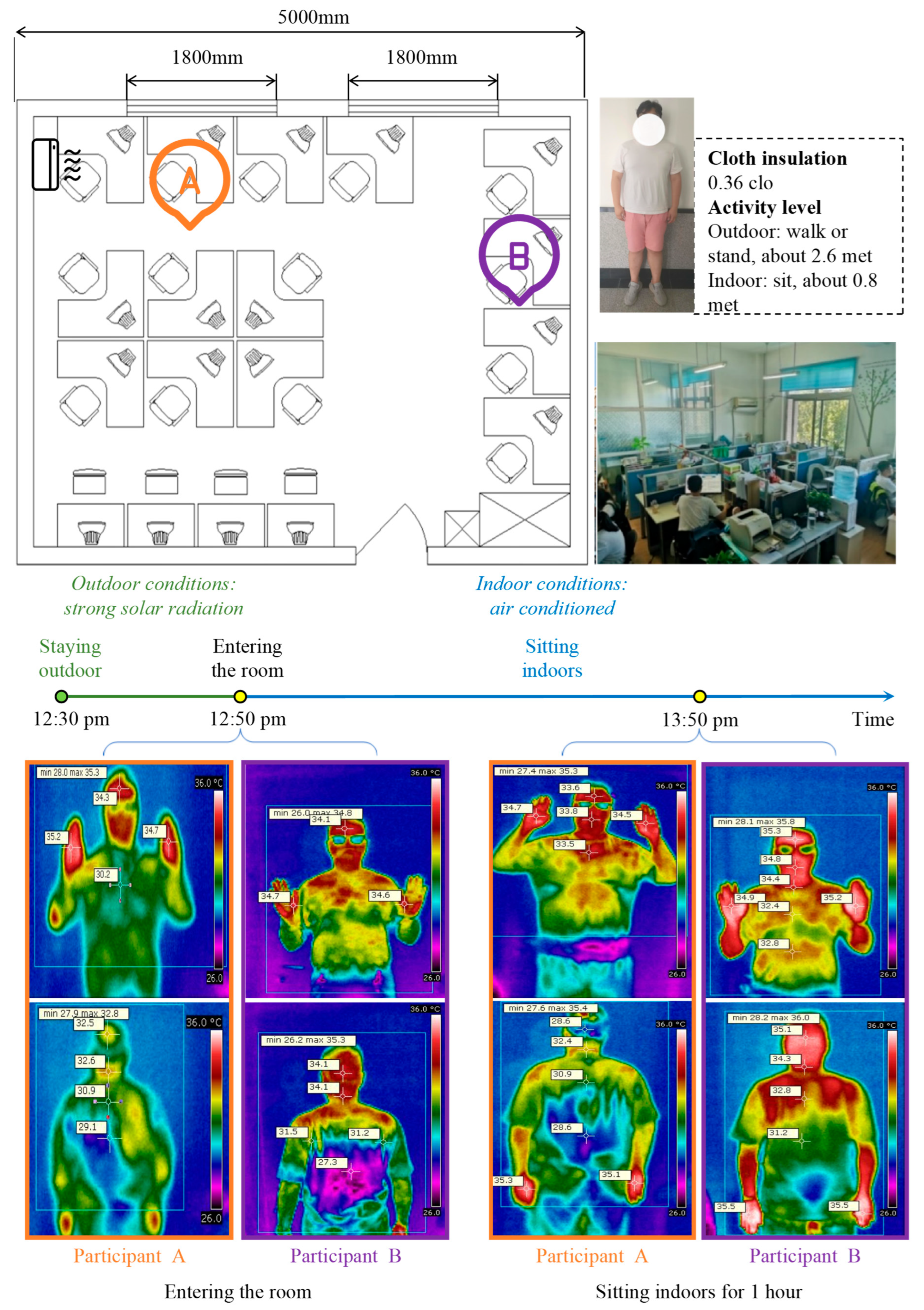

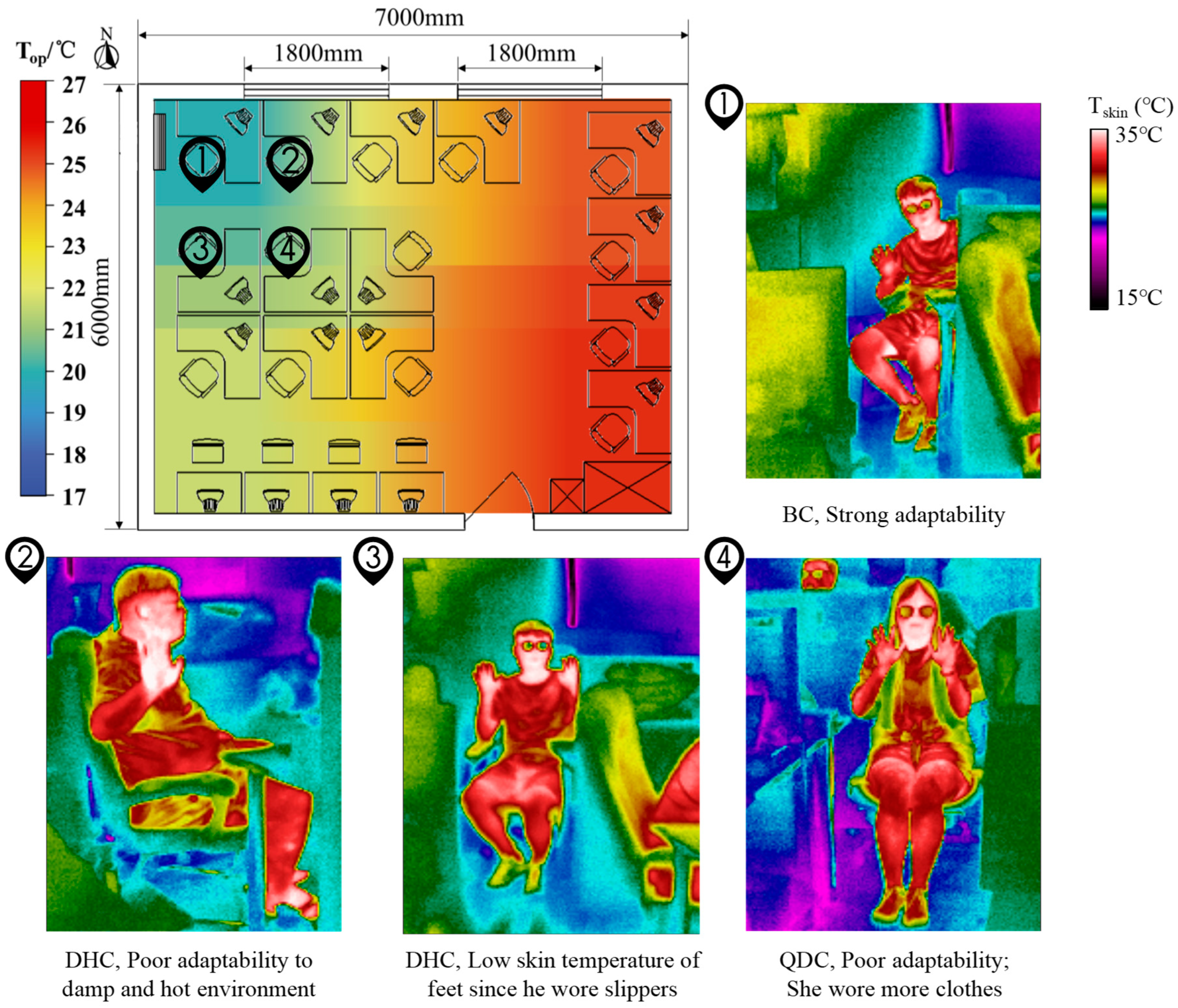

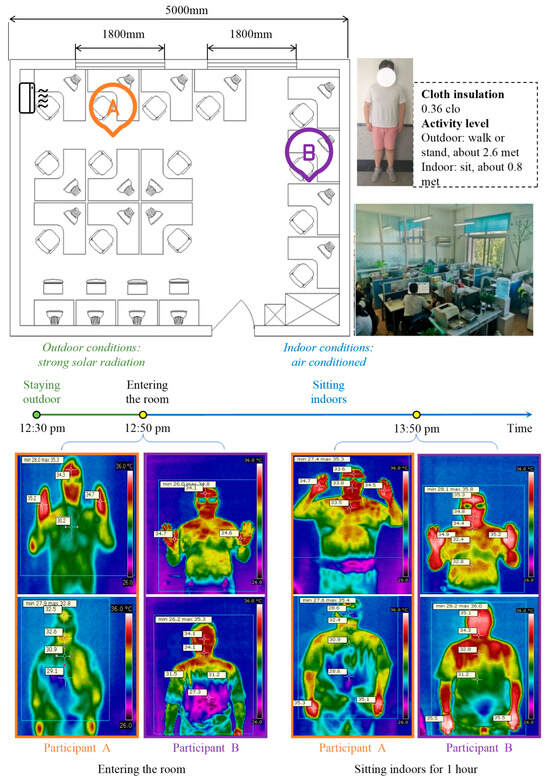

Furthermore, in situ experiments (Test L in Table 3) with young healthy staff in an office building on a university campus were employed to demonstrate how yin summer-heat risks appear in air-conditioned environments. The first experiment was to demonstrate thermal experience related to the typical routine of “returning to work after lunch break” on hot summer days with typical summer clothing. In the experiment, as shown in Figure 3, two healthy young male participants staying outdoors walking or standing for at least 20 min, with shading from time to time to adapt to the outdoor environment, and then entered the building to work in the air-conditioned offices. The real-time thermal environment changes experienced by the two participants were recorded using portable sensors that they carried with them, together with clothes and activity levels during the experiment. Thermal images of the upper-body skin temperature of the two participants were recorded when just stepping into the office and one hour later. In the office, Participants A and B were seated nearby and away from the outlet of air conditioners. Therefore, Participant A would feel more breezy and cool airflows. In addition, Participant A and B were of DHC and BC constitutions, respectively. There were also follow-up thermal image experiments to investigate the physiological responses of staff of different constitutions when they worked in the air-conditioned office with their daily clothing. All participants had lived in the city for years and adapted to the climate.

Figure 3.

A typical outdoor-to-indoor routine and individuals’ responses to environment changes on extreme hot days (Data from Test L).

The sensors used in the field tests were produced by reliable global suppliers with acceptable accuracy, and were calibrated regularly, such as temperature and humidity data loggers by T&D (e.g., TR-72Ui, ±0.1 °C), air velocity meters by Kanomax (e.g., KA-12, ±0.001 m/s), the thermal comfort meter by LSI-LASTEM (e.g., R-Log 7730, temperature ±0.1 °C, relative humidity ±0.1 °C, globe temperature ±0.5 °C), and the infrared thermal imaging camera by FLIR (e.g., T420, ±0.01 °C). Data analyses involved the calculation of operative temperature (), SET, the spectral analysis of air velocity, descriptive statistical analysis and regression analysis, etc.

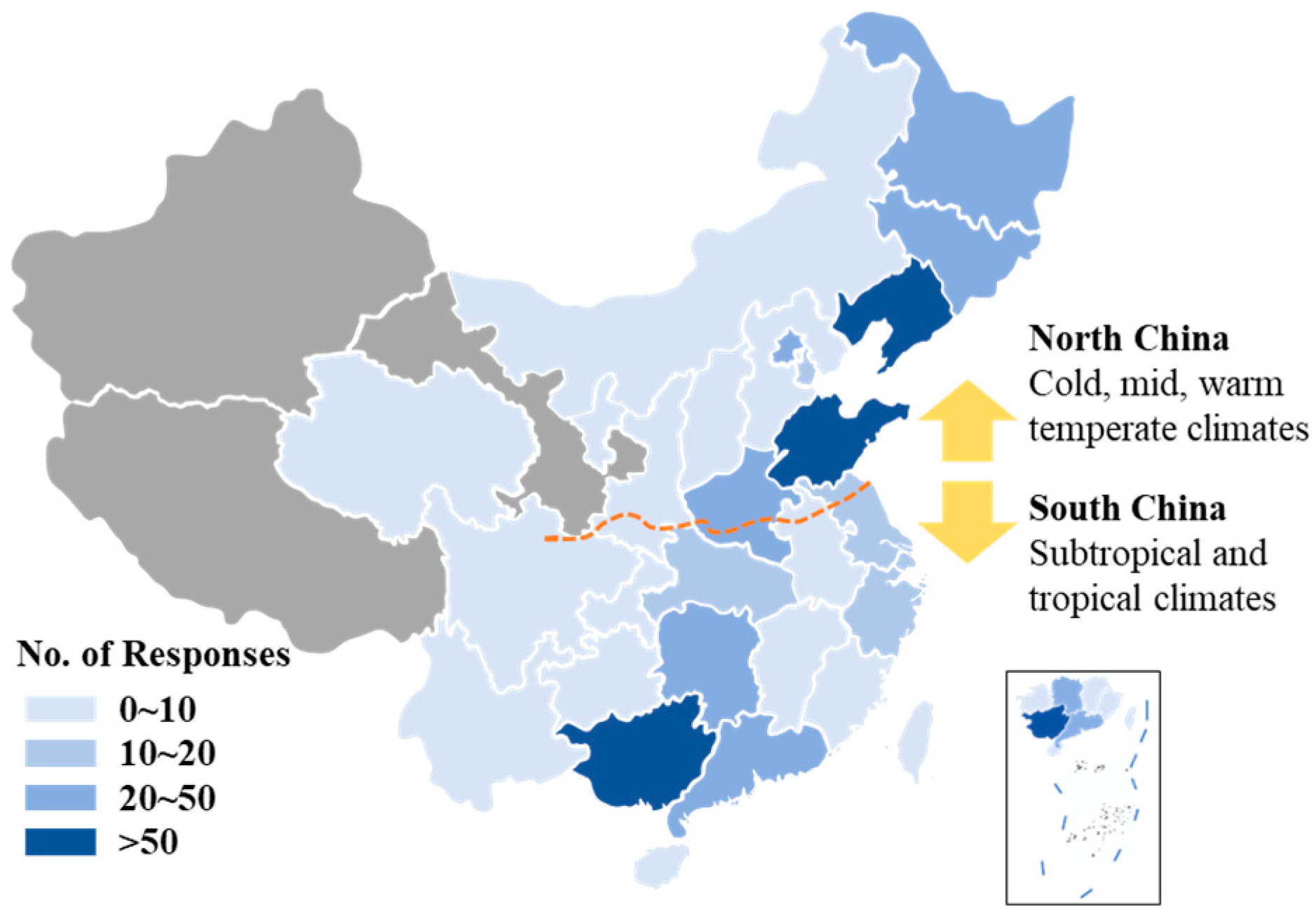

2.2. Questionnaire Survey

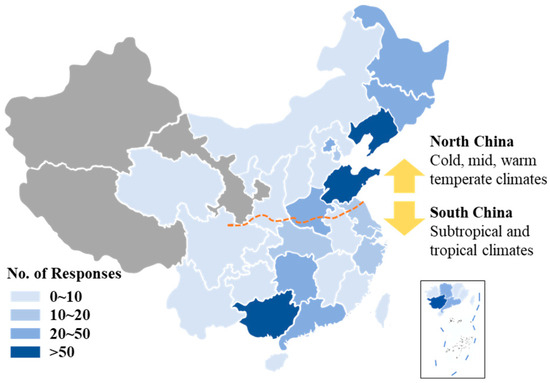

Three questionnaire surveys were carried out during the hottest days in 2020, 2022, and 2023, as shown in Table 4. The 10 min surveys contained about twenty to forty questions in six aspects, namely, a. demographic and physiologic characteristics, b. cooling-related adaptive behaviors, c. wellness habits and TCM knowledge, d. indoor environment sensation, acceptance, and preference, e. illness symptoms indoors, and f. test of constitutions in Chinese medicine (taking another 5 min). The definition of and identification approach to constitutions were mentioned above in Section 1.3. Example questions are shown in Appendix A Table A1. Questionnaires were delivered by well-trained researchers to ensure data quality. The participants were recruited by both online platforms and site visits roughly in a snowball process. The participants were required to understand and answer the questionnaire correctly. Finally, a total of 765 valid responses were obtained, in which 157 responses provided additional constitution identification results. The sample size qualified for descriptive statistical analysis. The participants of the questionnaire surveys lived in different cities across China, from both the subtropical climatic zone with long summers and the temperate climatic zone with four distinct seasons (Figure 4). The map of China used in Figure 4 is sourced from the WPS software, Version 12.0 [41], and the data for Questionnaire I and Questionnaire II are derived from the author’s research team [42,43]. There were 54.5% males and 45.5% females. Most participants ranged from eighteen to seventy years old (90.2%), and there were 30 and 45 responses from teenagers and the elderly aged more than seventy, respectively. The geographical and demographic diversity of the sample enabled comparative analyses of the varied demand, perception, and interaction with the built environment of different occupant segments.

Table 4.

A brief overview of questionnaire surveys during hot summer in 2020~2023.

Figure 4.

Regional distribution of responses of questionnaire surveys (the map was produced by WPS Office [41]; the data were collected by the authors in previous work [42,43]).

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Outdoor and Indoor Environment Features During Extreme Hot Period

Extreme hot days refer to a period when the outdoor temperature and humidity remain relatively high according to the typical meteorological year (TMY) data, as shown in Figure 2. First, the comparison of the TMY data before, during, and after the extreme hot period showcased the temporal changes in outdoor conditions to be adapted to by humans. Dalian was taken as an example, to which other cities showed analogous results. Statistical and analysis results of the TMY data are presented in Figure 5, including air temperature, apparent temperature, relative humidity, and absolute humidity. In particular, apparent temperature (), was defined by Equation (1) in a tourism industrial standard [44] to reflect an individual’s perceived outdoor temperature determined by air temperature, velocity, and humidity.

where refers to real-time air temperature [°C]; and refer to the daily maximum or minimum air temperature [°C], respectively; refers to real-time relative humidity [%]; and refers to real-time air velocity [m/s].

Figure 5.

TMY data before, during, and after extreme hot days in the city of Dalian (data from Li et al. [45]).

Generally, the variation in outdoor temperature and humidity narrowed down during extreme hot days, and it would be continuously hot and humid outside with more gentle fluctuations. The increase steps of environment parameters were smaller than the decrease steps, indicating a milder emerging of heat and dampness but a slightly faster appearing of coldness and dryness, before and after extreme hot days, respectively. Specifically, air temperature and apparent temperature during extreme hot days in Dalian became separately 2.8 °C and 3.7 °C higher than the former month. This supported the necessity to consider the combined impact of climatic indicators on an individual’s outdoor thermal feelings. In addition, absolute humidity became 3.2 g/m3 and 4.4 g/m3 higher during extreme hot days in Dalian. Meanwhile, relative humidity remained similarly high in the transition and hot days, suggesting the advantages of absolute humidity in describing changes in moisture. This study therefore prioritized absolute humidity in analyses.

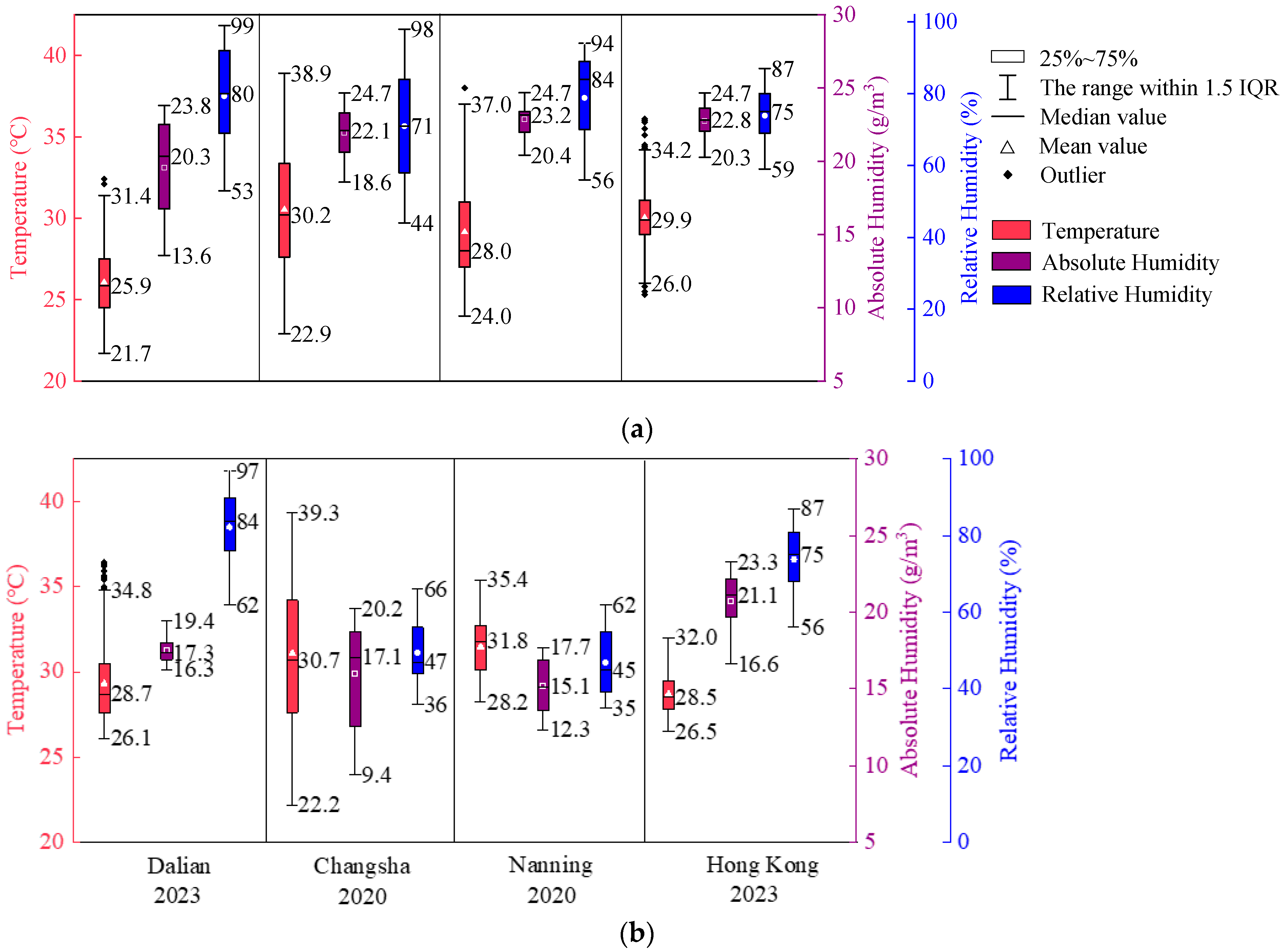

Second, outdoor conditions during the extreme hot period were examined in different cities from North to South China, where the field tests were conducted (Figure 6). Though certain discrepancies existed in the TMY data and the field test records, the TMY data helped to understand the fundamental climate characteristics of different cities. The diurnal temperature range (DTR), i.e., the difference between day and night temperatures, was roughly 4.9 °C, 8.0 °C, 7.3 °C, and 4.0 °C separately for Dalian, Changsha, Nanning, and Hong Kong in the TMY data during the extreme hot period. Moreover, the average TMY wind speed was 3.5 m/s, 2.2 m/s, 1.5 m/s, and 3.8 m/s in Dalian, Changsha, Nanning, and Hong Kong, respectively. Wind directions remained mostly the same or were more varied for seaside cities, but became to some extent converged in the inland city of Changsha.

Figure 6.

(a) TMY records during extreme hot days; (b) Outdoor climate conditions during field test periods in selected cities (data from Li et al. [45] and field test results. Extreme hot days were defined as in Figure 2).

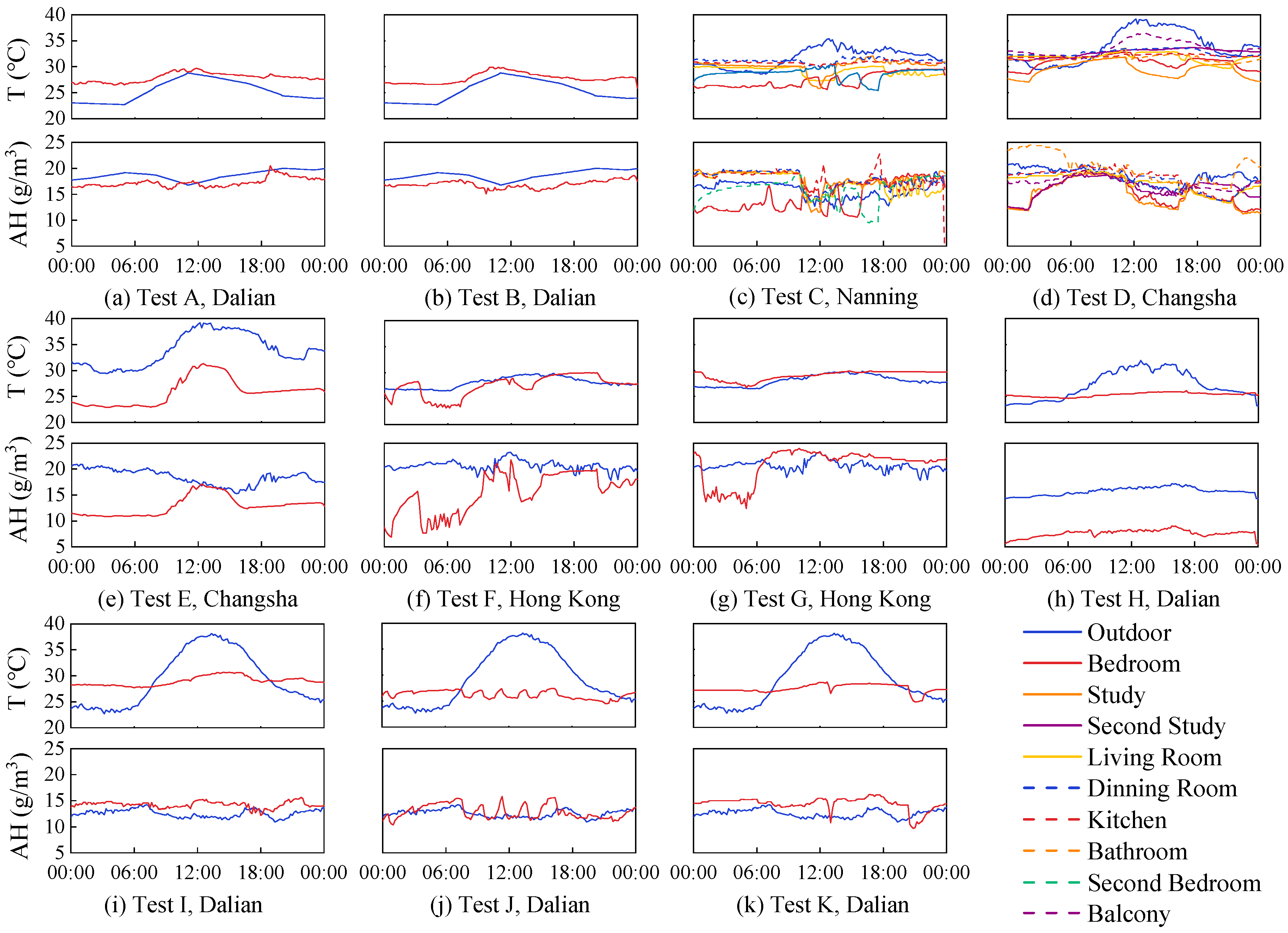

Third, indoor conditions in Tests A~K on typical hot summer days are presented in Figure 7. As for air temperature, it was hotter outdoors for most of the time and the orientation of certain rooms and rainy days (e.g., in Tests A, B, F, and G) could explain other situations. The maximum real-time indoor–outdoor temperature differences in a day even reached 12.2 °C (Test J), which usually appeared in the daytime. Generally, in the daytime (10:00~16:00), the average real-time temperature difference between the outside and living room or study room was −1.0 °C~10.4 °C, while at nighttime (22:00~6:00) the difference between the outside and bedroom was −4.2 °C~7.2 °C in different tests. In addition, temperature gaps existed among different rooms. For example, a sectional analysis of air temperatures in different rooms in Test C, Nanning, at 17:00 on August 30 in 2020, showed varied indoor air temperature in the master bedroom (28.9 °C), second bedroom (25.6 °C), living room (30.1 °C), kitchen (31.0 °C) and dining room (31.9 °C) when it was 32.5 °C outside. The occupant would experience a sudden temperature drop of 6.9 °C when entering the second bedroom from the outside, and then a temperature rise of 6.3 °C when going to the dining room to drink water. That is, occupants would experience unignorable sudden drops or rises not only with indoor–outdoor space switching but also with movement between different rooms, indicating potential health risks related to temperature steps, as discussed in Section 1.1.

Figure 7.

Indoor thermal conditions in monitoring periods. (a) Test A in Dalian; (b) Test B in Dalian; (c) Test C in Nanning; (d) Test D in Changsha; (e) Test E in Changsha; (f) Test F in Hong Kong; (g) Test G in Hong Kong; (h) Test H in Dalian; (i) Test I in Dalian; (j) Test J in Dalian; (k) Test K in Dalian. The houses were mostly occupied on the selected day (both sunny and rainy (Tests A, B, F, and G). Data from Tests A~K). T and AH refer to air temperature and absolute humidity.

As for air humidity, it is more humid indoors for most tests, except for Tests I, J, and K in Dalian. The maximum real-time indoor–outdoor humidity differences in a day reached 13.6 g/m3 (Test F), excluding the regular high-humidity moments in daily life, such as cooking in the kitchen and showering in the rest room. Similarly, absolute humidity gaps existed not only between indoor and outdoor environments but also among different rooms, and the gaps could be larger in the latter situation. For example, the absolute humidity was 11.4 g/m3 in the master study room and 11.7 g/m3 in the bedroom, but 15.9 g/m3 in the living room, 16.1 g/m3 in the kitchen, 16.6 g/m3 in the dining room, and 21.9 g/m3 in the bathroom when it was 18.3 g/m3 outdoors, for Test D, Changsha, at 22:30 on 10 August in 2022.

Summarily, extreme hot periods in Chinese cities featured a continuously hot and humid outdoor environment. Obvious indoor–outdoor and indoor–indoor gaps appeared in thermal environments during extreme hot periods in the observed cities, e.g., the maximum real time indoor–outdoor temperature and absolute humidity differences in a day reached 12.2 °C and 13.6 g/m3 (Q1).

3.2. “Yin Summer-Heat” Risks in the Well-Conditioned Buildings

The in-situ experiments elaborated the process and stress of thermal accumulation in air-conditioned environments. Figure 3 displays the skin temperature changes of the two participants entering the air-conditioned office room from the sunny outside. Both of them experienced rapid changes in ambient micro-climates when entering the room, with the sudden drops in air temperature and absolute humidity being 8.3 °C (35.8 °C → 27.2 °C) and 5.4 g/m3 (17.5 g/m3 → 12.1 g/m3). After resting for one hour, the forehead and chest skin temperature of Participant A decreased by 0.7 °C (34.3 °C → 33.6 °C) and increased by 1.9 °C (30.2 °C → 32.1 °C), separately, while those of Participant B increased by 0.8 °C (34.1 °C → 35.3 °C) and decreased by 2.2 °C (34.6 °C → 32.4 °C). In particular, the TCM acupoint of Wind Pool (“Feng Chi” in Chinese) was located nearby the back of neck, which is sensitive to drafts [46].

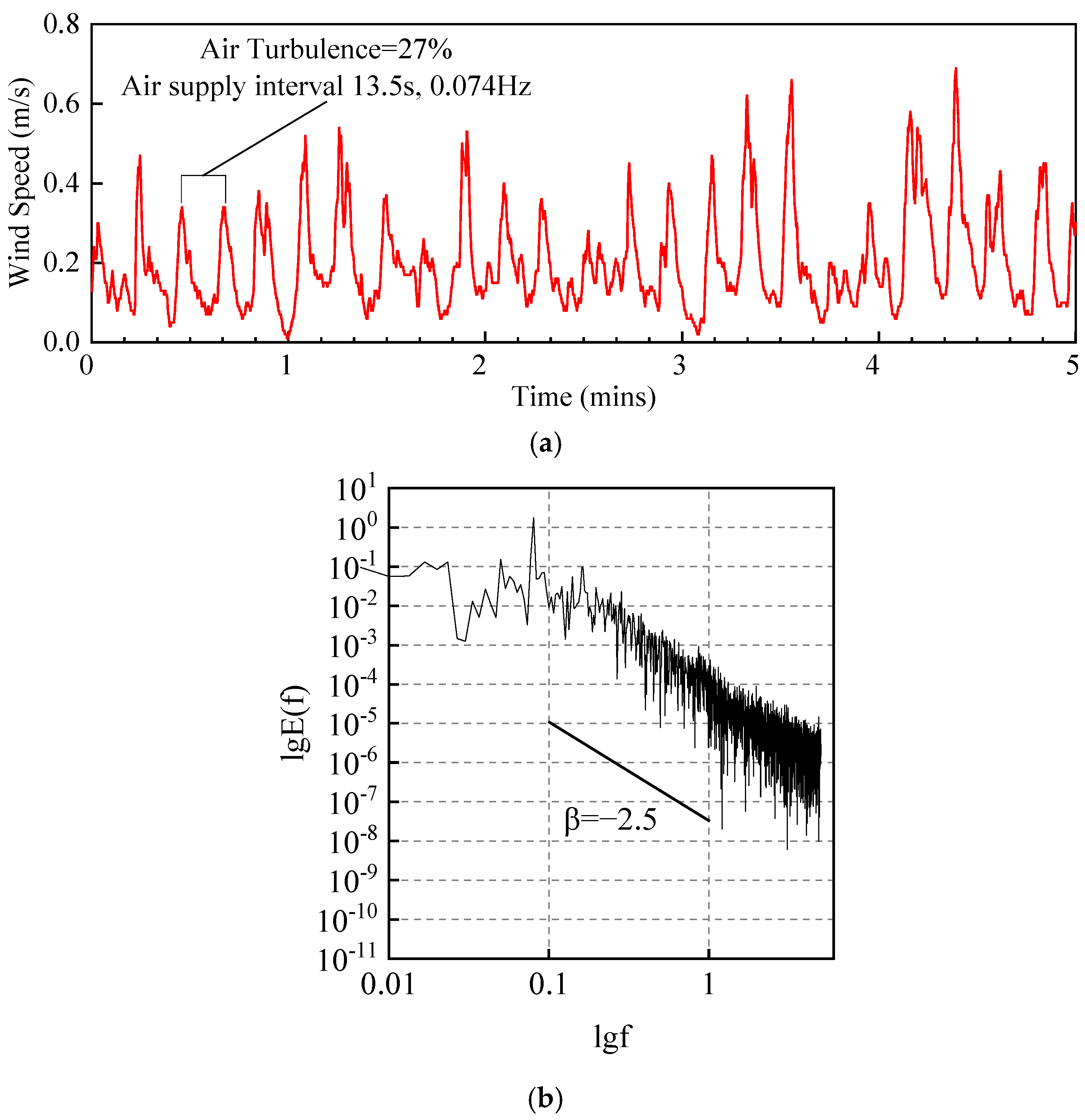

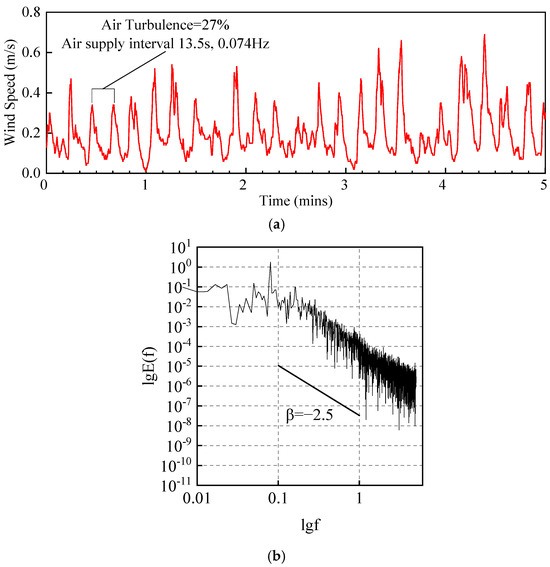

Further analyses indicated wind characteristics in the air-conditioned experiment office. The wind azimuth angle was investigated using the power spectral density function (PSD), and the negative slope of the curve (β) indicated horizontal directional fluctuations in wind at the dominant frequency, as proposed and elaborated in [47]. Natural wind samples typically exhibit β values exceeding 1.1 [47]. In this experiment, the β value of air conditioning supply airflow measured 2.5 (Figure 8). A maximum air velocity of 0.4–0.6 m/s was observed, exceeding or reaching the upper limit of the draft rate (DR) values specified in ASHRAE standards [48]. Accordingly, Participant A positioned within the airflow trajectory reported thermal discomfort due to the elevated air velocity. Also, a much lower skin temperature was observed on the back of neck with Participant A than Participant B, being 28.6 °C and 34.3 °C, respectively, after one hour of staying indoors. The different skin temperature changes of the two participants could be explained by the fact that Participant A (DHC) naturally preferred cooler feelings than Participant B (BC) and therefore stayed near the air conditioner, which aroused yin summer-heat risks. For example, the SET of Seat A and B was roughly 18.1 °C and 28.1 °C.

Figure 8.

Dynamic features of airflows in the SAC office (data from Test L). (a) Air velocity of the supply air of the split-type air conditioner near the neck of Participant A; (b) logarithmic power spectrum curves of supply air.

That is, the enlarged gaps between indoor and outdoor conditions due to air conditioning would bring about notable regulation stress for occupants, evoke cold and wind excesses, and then cause yin summer-heat symptoms such as muscle soreness or stiffness. There would also be other symptoms, including respiratory discomfort related to low humidity. Also, yin-summer heat risks would appear to different extents due to the exposure to the cool supply air of air conditioners and occupants’ constitutions.

Follow-up analyses of four staff sitting near the air conditioners suggested different yin summer-heat risks for vulnerable individuals (Figure 9). Staff 1, 2, 3, and 4 were of BC, DHC, DHC, and QDC constitutions, respectively. The operative temperature () was clearly lower for the four seats than others distant seats. The thermal and humid sensation votes of the four staff were mostly neutral and occasionally slightly cool or dry. However, they showed somewhat varied skin temperature. For example, Staff 1 (BC) with strong adaptability showed a slightly higher face and palm temperature than Staff 2 and 3 (DHC), who tended to feel hot. Also, they adjusted their clothes differently. Staff 3 wore slippers, and the exposed foot skin showed a relatively low temperature (27.8 °C). Staff 4 with poor environment adaptability wore more clothes (e.g., a coat). Despite such behavioral adaptation, yin summer-heat risks hid in the so-called “neutral” air-conditioned environment. It is essential to figure out how to utilize artificial cooling appropriately without covert health risks in the long run.

Figure 9.

Yin summer-heat risks in the SAC office for young people of different constitutions (data from Test L).

Summarily, the experiment results showed that yin summer-heat risks were quite common with daily exposure to air-conditioned environments, even with thermally neutral cases, which presented quite different air temperature, humidity, and air movement characteristics than a natural environment (Q1).

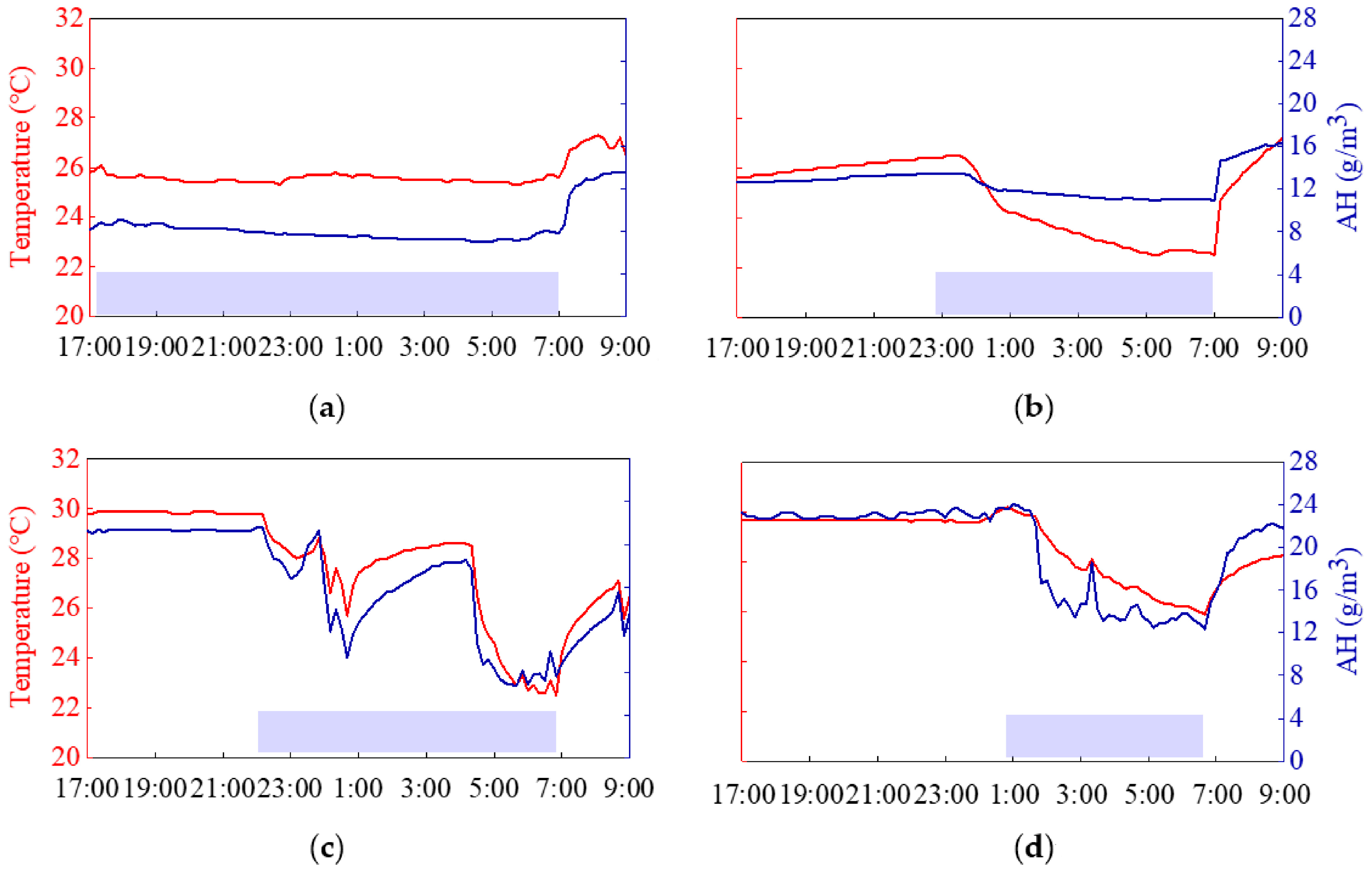

3.3. The Diverse Lifestyles and Demands of Occupants with Different Constitutions

Field test results in bedrooms for participants of different constitutions indicated that indoor thermal environment control modes would vary according to individuals’ constitution features. As shown in Figure 10, the longest air conditioner usage time during non-work time was observed with the young male in Dalian, who was of the dampness–heat constitution (DHC), being less tolerant of damp and hot environments. The room air conditioning kept operating almost all the time when the room was occupied. The room temperature and absolute humidity were kept roughly at 25.3 °C and 7.3 g/m3. Moreover, much less air conditioner usage time was found with a young female and a young male in Hong Kong The young female was of the yang-deficiency constitution (YADC), being vulnerable to wind, cold, and dampness excesses. She turned on air conditioners only for a while before sleeping or when it was getting hot and humid (28.6 °C and 18.3 g/m3 around 4:00 a.m.). The rapid drops in temperature and humidity, e.g., towards as low as 22.6 °C and 7.2 g/m3 after 4:00 a.m. probably suggested her compensatory expectation of a cool and dry sleeping environment. The young male was of the balanced constitution (BC), with strong environment adaptability. He moderately used air conditioners during sleeping when the room temperature decreased gradually from 30.1 °C to 25.9 °C. As for the elderly female in Changsha, who was of the yin-deficiency constitution (YIDC), being vulnerable to summer heat, dryness, and fire excesses, he could only endure the contradictory dehumidifying and overcooling effects of air conditioning when sleeping.

Figure 10.

Operation modes of room air conditioners during non-work time (17:00~9:00 (the next day)) for participants of different constitutions. (a) Test H, Dalian, DHC, AC kept open in rest time; (b) Test E, Changsha, YIDC, Low temperature, high AH; (c) Test F, Hongkong, YADC, Greater humidity drop; (d) Test G, Hongkong, BC, Shorter AC time and higher set temperature. Abbreviations such as BC refer to the constitutions listed in Table 2.

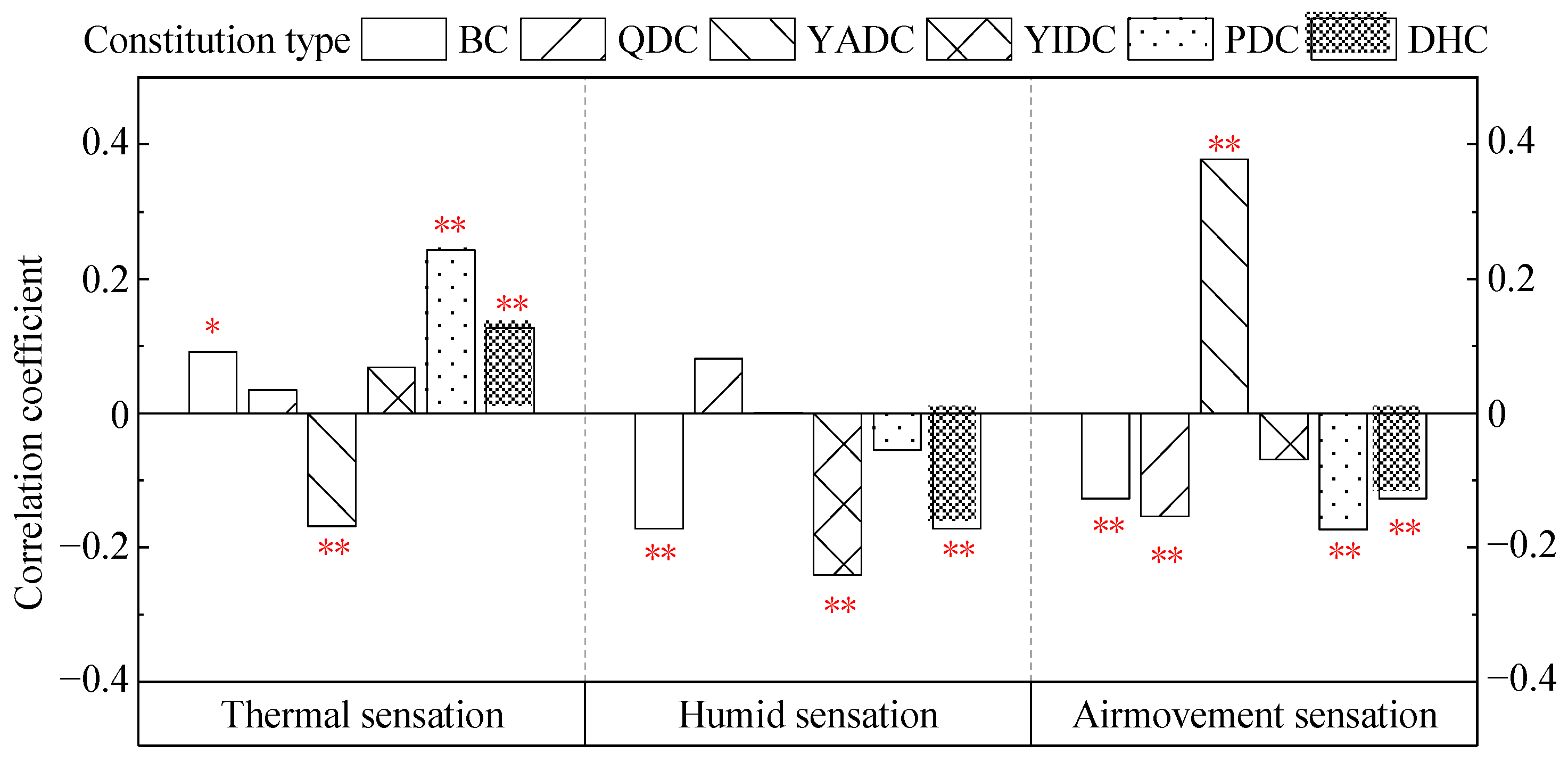

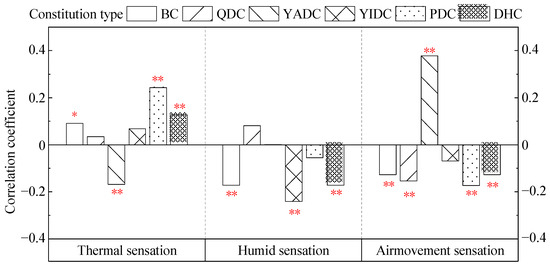

Furthermore, significant correlations existed between the participants’ constitutions and environment perceptions in the field tests. Generally, the major constitution worked well to interpret an individual’s tendency in thermal, humid, and air movement sensation. As illustrated in Figure 11, participants with more YADC features, being vulnerable to wind, cold, and dampness excesses, tended to feel warm and breezy indoors. Participants with more YIDC features, being vulnerable to summer heat, dryness, and fire excesses, would feel dry easily. Participants with more DHC features, being less tolerant of damp and hot environments, were sensitive to heat. However, there seemed to some extent to be contradictory or irrelevant results for BC, QDC, and PDC features. This might be explained by potential pathogenic excesses associated with individuals’ minor constitutions, which needs further exploration.

Figure 11.

Correlations between constitutions and thermal, humid, and air movement sensation. Thermal, humid, and air movement sensation were measured with 7-point scales, with “−3” and “3” referring to hot and cold, very dry and very humid, and very still and very breezy, respectively. Lack of data for BSC, QSD, and ISC constitutions. * and ** mean significance at p < 0.01 and 0.05 levels, respectively.

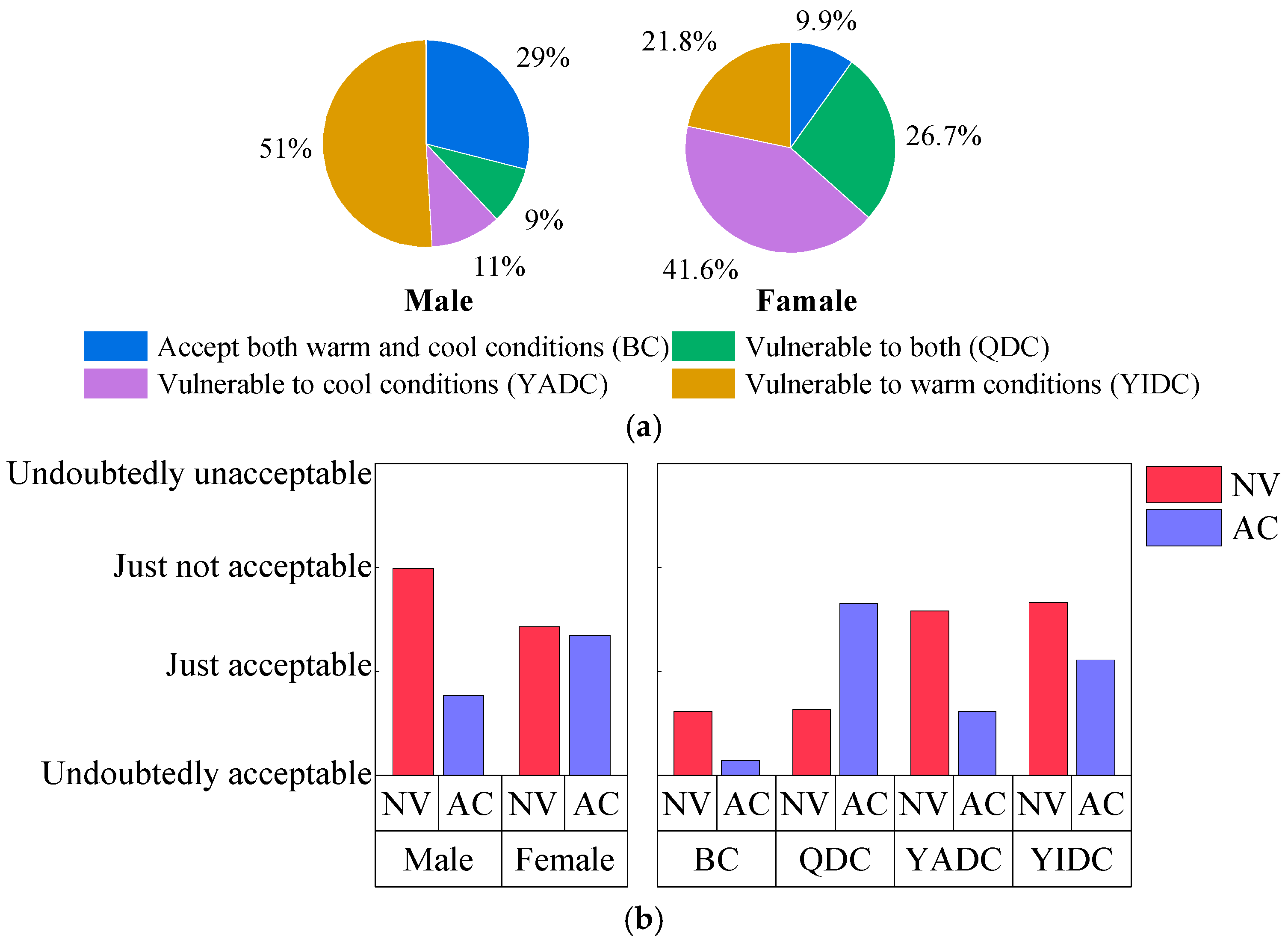

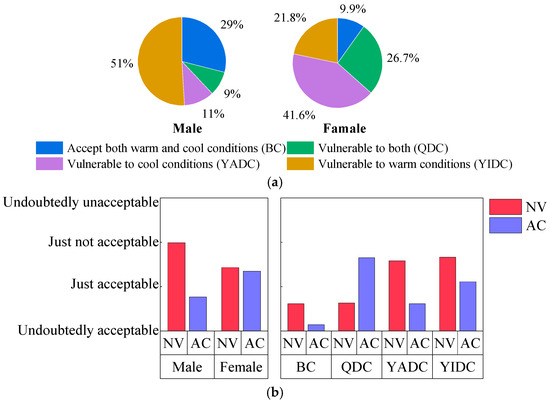

The large sample size of the questionnaire surveys enabled further exploration of population heterogeneity in the physiological and behavioral adaptation to hot summer, in the view of personal properties such as gender, age, and constitutions. There were four typical constitutions, which varied a lot in the tolerance of heat and coldness. Specifically, BC showed good thermal acceptance, with a wide thermal comfort zone, according to the environment adaptability and TCM pathogenic factors elaborated in Table 2; QDC presented a narrow zone easily affected by both heat and coldness; and YADC could not bear coldness and YIDC could not bear heat. Figure 12a illustrates that about 29% of males and 10% of females were of constitutions with strong thermal acceptance (BC). Generally, males were more resistant to cool conditions (BC + YIDC, 80%) and disliked warm conditions, while females were less tolerant of cool conditions (QDC + YADC, 68%) and preferred warm conditions. The constitution features explain the gender differences in thermal acceptance in naturally ventilated (NV) and air-conditioned environments (Figure 12b). That is, AC environments were usually cooler and poorly accepted by individuals vulnerable to cool conditions, such as many females, but well accepted by males.

Figure 12.

Thermal acceptance with gender and constitutions (data from Questionnaire I). NV and AC refer to naturally ventilated and air-conditioned buildings, respectively. (a) Gender distribution of constitutions; (b) thermal acceptance with gender (left) and constitutions (right).

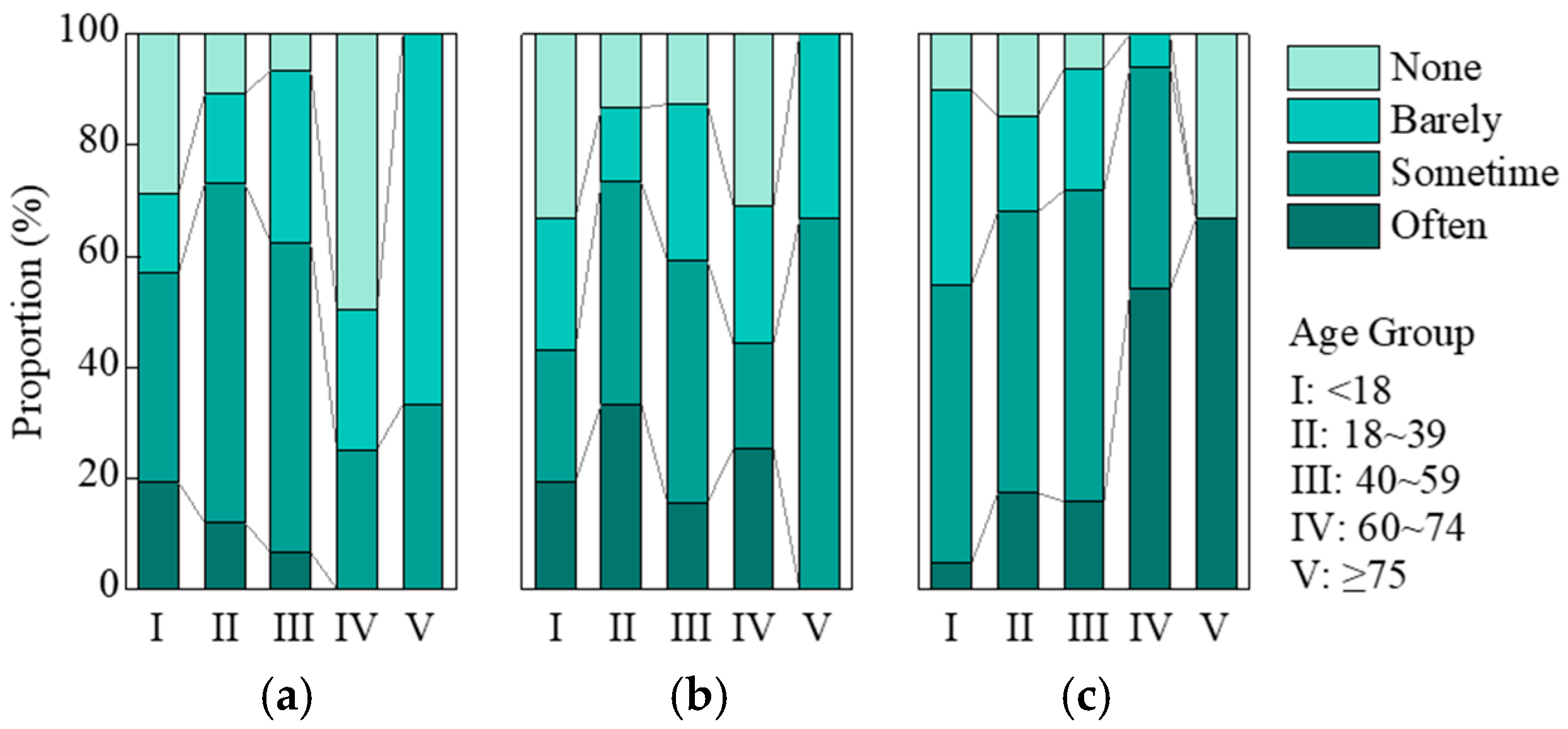

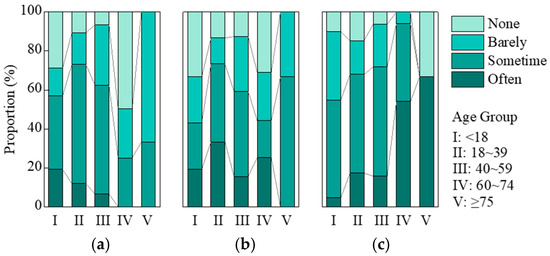

Adaptive behaviors in hot summer changed with age. As displayed in Figure 13, young people would sometimes find it too hot to sleep and frequently use electric fans or air conditioners. Meanwhile, middle-aged and elderly people would only be annoyed by sleepless hot nights occasionally. Elderly people preferred natural cooling measures, such as hand fans and opening windows.

Figure 13.

Behavioral adaption in hot summer days of different age groups (data from Questionnaire II). (a) How often will you feel too hot to sleep; (b) How often will you sleep with air-conditioner or electric fan operating; (c) How often will you use natural cooling measures.

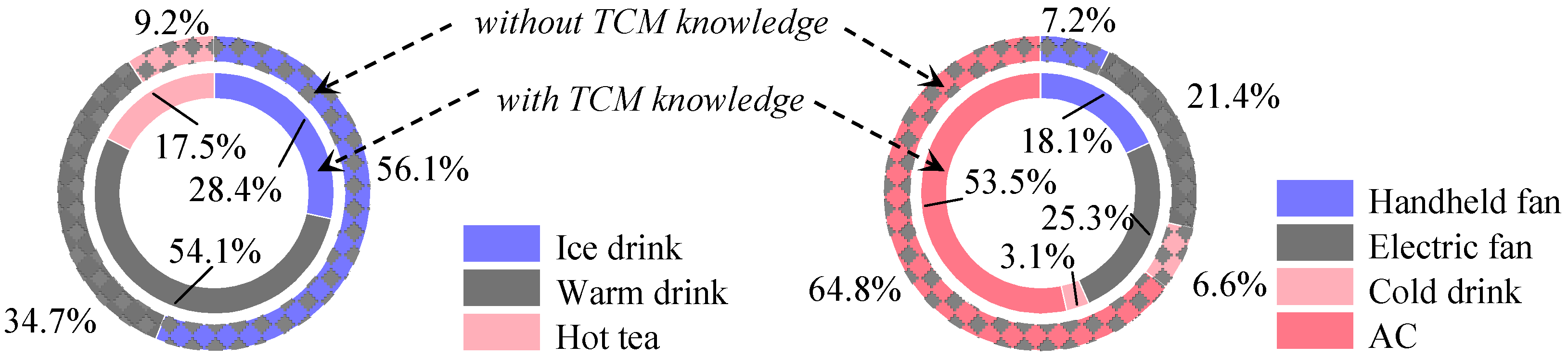

Differences in adaptive behaviors could not only be explained by the tendency toward warmer environments when people get older or their heat exposures at earlier ages, mentioned in a large-scale study in Australia [49], but also be associated with lifestyles cultivated silently by the TCM culture. TCM knowledge guides individuals to maintain wellbeing in everyday life, e.g., how to adjust clothes, food, and housing conditions to prevent illness and improve health. The health preservation principles originated from the concept of organic wholeness as the core idea of TCM, e.g., the unity of internal and external environments and the unity of the body and the spirit. As shown in Figure 14, individuals with TCM health preservation knowledge relied less on air conditioning and preferred natural cooling measures, such as hand fans, compared with those without TCM knowledge. Individuals (82%) with TCM knowledge would take hot tea or drinks at room temperature when they were sweating, while those without TCM knowledge preferred cold drinks (56%). However, such reliance on air conditioners and cold drinks for quick cool feelings in hot summer was accompanied by yin summer-heat risks.

Figure 14.

Summer adaptive behaviors reported by participants who were with or without TCM health preservation knowledge (data from Questionnaire II).

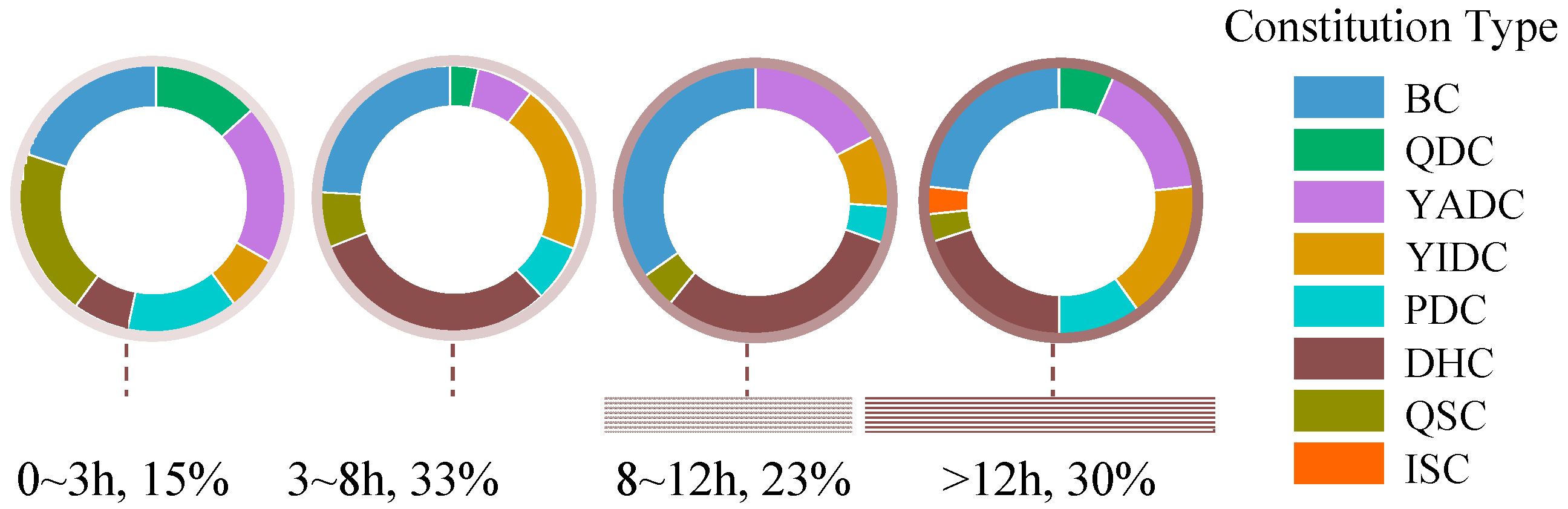

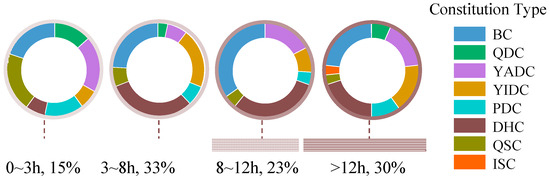

As for the usage time of air conditioners (Figure 15), 15%, 33%, 23%, and 30% of responses reported less than three hours, three to eight hours, eight to twelve hours, and more than twelve hours staying in air-conditioned environments, including the workplace and home, in a day. Restrained usage of air conditioners, i.e., less than three hours of exposure to air-conditioned environments, was common for QDC and QSC participants with weak constitutions. Meanwhile, DHC participants who were less tolerant of dampness and heat would stay in air-conditioned environments for even more than twelve hours per day.

Figure 15.

Daily time in air-conditioned environments by constitutions (data from Questionnaire III).

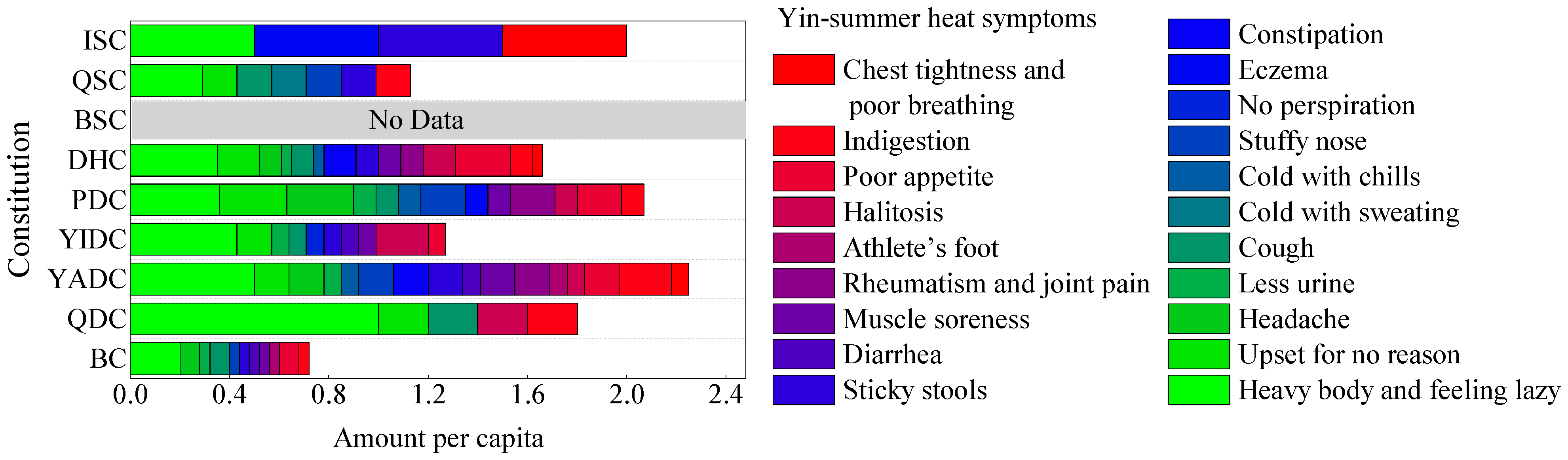

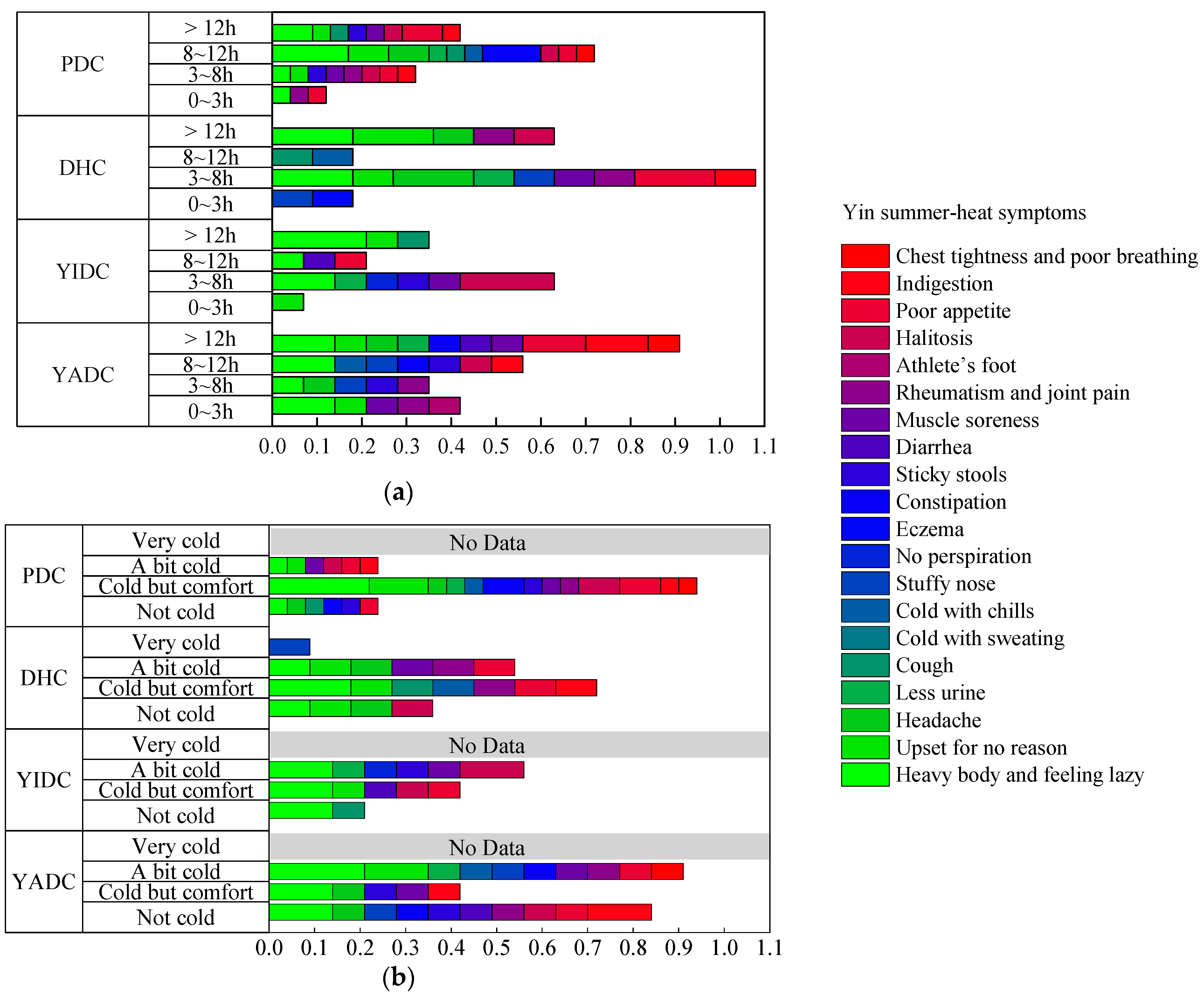

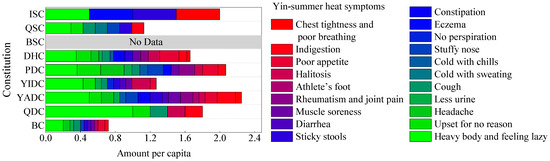

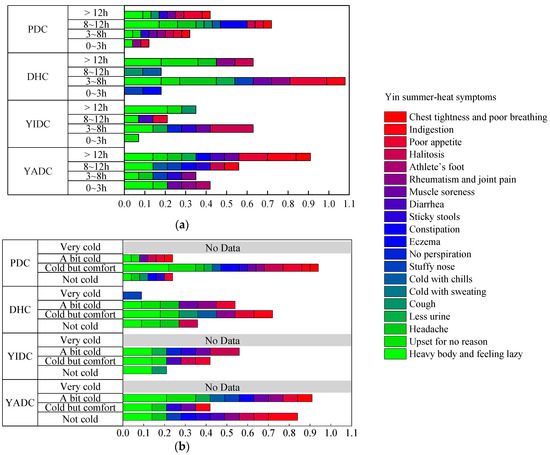

The average number of specific yin summer-heat symptoms appearing in the questionnaires of participants of the nine constitutions was examined, as shown in Figure 16. This study employed the indicator of the average number of all symptoms per capita to show the overall impact. Twenty symptoms were investigated, namely, a heavy feeling in the body and feeling lazy, upset for no reason, headache, less urine, cough, cold with sweating, cold with chills, stuffy nose, no perspiration, eczema, sticky stools, diarrhea, muscle soreness, rheumatism and joint pain, athlete’s foot, halitosis, poor appetite, indigestion, chest tightness, and poor breathing. A higher proportion of BC participants stated no symptoms compared to other constitutions. A greater variety and number of discomfort feelings were reported by YADC, PDC, and DHC participants. YADC participants, who used air conditioners rather frequently, topped the nine constitutions in the average number of symptoms. Many non-BC participants reported a heavy feeling in the body, which was a typical yin summer-heat characteristic. Furthermore, extended AC exposure might exacerbate yin summer-heat symptoms. As shown in Figure 17, YADC, YIDC, PDC, and DHC participants, who suffered from cold excess associated with overcooling, showed severe symptoms such as diarrhea, poor appetite, and chest tightness, indicating that cold excess was trapped in the body, other than just invading the skin or approaching the lungs. Also, more symptoms would emerge when these participants felt cold, even in a comfortable manner, than when it was neutral or not cool.

Figure 16.

Amount of yin summer-heat symptoms per capita of different constitutions (data from Questionnaire III). Lack of BDC data in the analyzed data.

Figure 17.

Cross-analysis results of the number of symptoms per capita in air-conditioned environments by constitutions, AC hours, and thermal sensation (data from Questionnaire III; limited data for “very cold” scenario). (a) Amount of symptoms per capita with different AC hours and constitutions; (b) Amount of symptoms per capita with different thermal sensation and constitutions.

Summarily, the field tests and questionnaire survey results suggested the large variation in indoor environment demands and adaptive behaviors due to personal attributes, including gender, age, health preservation knowledge, and the Chinese constitution. In particular, constitutions worked well to explain the thermal perceptions, the usage mode of air conditioners, and the yin summer-heat symptoms of different populations (Q2).

4. Discussion

4.1. Health Risks in Well-Conditioned Buildings and Comfortable Environments: Should the Environment Be Isolated or Open?

Occupants in well-conditioned modern buildings are becoming accustomed to efficient and standardized control strategies and losing patience with natural solutions, such as adjusting clothing, using hand fans, and opening windows. As shown in Figure 13, young people were more often bothered by sleepless hot nights than elderly people (e.g., about 60% aged below 60 vs. 30% aged above 60), and tended to rely on air conditioners and electric fans for night cooling. It was also found that, for individuals with a lack of TCM knowledge to strengthen their adaptation to seasonal natural environment changes, air conditioners (64.8%) were their first choice for quick cooling in hot summer (Figure 14). Another study with Chinese urbanites [50] stated similar findings that young people performed fewer wellness habits, set lower indoor temperatures, and operated air conditioners more frequently, indicating the trend of the dependence on and precedence of air conditioning in summer indoor environment control.

However, this study found that staying long-term in “neutral” or “comfortable” air-conditioned environments was accompanied by potential yin summer-heat risks, aroused mainly by cold excess. For example, the number of symptoms per capita in the “cold but comfortable” environment was about 0.9, 0.7, 0.4, and 0.4 for participants with vulnerable constitutions of PDC, DHC, YIDC, and YADC, respectively (Figure 16). The health risks could firstly appear as trivial discomforts, which were easily ignored, for example, occasional coughs, but accumulate to be severe body symptoms in the long run according to TCM theories. Similar worries were proposed in the existing literature that the use of air conditioning for cooling would remove stimuli for physiological and perceptual adaption to the heat [51]. Some researchers used the metaphor of an “antibiotic” [52] to demonstrate the overuse of cooling devices and the necessity of demand management in modern buildings. A climate chamber study with seven healthy young subjects in China [53] found that short-term appropriate cold or hot exposure may help to enhance respiratory mucosal immunity by testing salivary secretory immunoglobulin E (S-IgE) at a temperature of 15~33 °C. This suggests that appropriate short-term cold and heat exposure may enhance human immune competence. However, the mechanisms underlying the beneficial versus detrimental effects of rapid thermal stress exposure require further investigation in future studies, particularly regarding dose–response relationships and individual constitutional variations. A multidisciplinary approach integrating thermo-physiology, immunophenotyping, and constitution assessment would be critical to establish personalized thermal exposure protocols.

4.2. The Ignored Role of Occupants in Indoor Environment Control and Their Diverse Demands: Should the Control Targets Be Fixed or Flexible?

Another issue is the overlooking of the proactive role of occupants in indoor environment control and their diverse demands due to contextual factors in existing thermal models and IEQ standards. Reflections on the narrow comfort zone (22~25 °C) and the standardized thermal comfort models, e.g., the predicted mean vote (PMV) model, led to the development of personal thermal comfort models, such as an adaptive model that extended the comfort zone to 21~29 °C [51] considering outdoor conditions and the thermal adaptation of occupants. It is now widely accepted that occupants should not be treated as “passive receipts of the external environment”, since multifaceted and comprehensive interactions exist between occupants and the external environment [54]. Occupant centric control (OCC) strategies, compared to traditional centralized control strategies, also follow the fundamental principle of delivering building services according to occupants’ needs [55].

Generally, organic wholeness thoughts shaped the environment values of Chinese people, as well as their sensing of and reaction to the external environment. Such culture factors might explain the greater slope of 0.45 in the adaptive model tailored to China’s naturally ventilated buildings [56], indicating a wider comfort zone than the slopes of 0.31 and 0.33 in ASHRAE 55-2020 [57] and EN 15251-2007 [58], respectively. In this present study, diverse demands and adaptive behaviors were found at the individual level, varying with gender, age, and, particularly, constitution. In particular, constitutions in Chinese medicine help to understand the environmental adaptability and adaptive behaviors of Chinese people. For example, DHC individuals who were less tolerant of hot and damp environments reported roughly the most usage of air conditioners in hot summer. Moreover, TCM knowledge on health preservation inspired ways to avoid potential health risks and create a wellbeing-centered indoor environment. For example, BC individuals displayed strong thermal adaptability. Individuals of constitutions such as YADC, YIDC, PDC, and DHC, being vulnerable to cold or wind excesses, showed more and severe yin summer-heat symptoms in an air-conditioned environment despite it being “comfortable”. Thus, appropriate indoor micro-climate control targets and strategies should be set correspondingly for occupants of different constitutions. Flexible control in both temporal and spatial manners should be encouraged for shared spaces, e.g., in multi-member families and multi-person offices.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed reflections on indoor environment control in hot summer from a “yin summer-heat” perspective under TCM theories. Eleven field tests were carried out in residential buildings, together with experiments in an office environment and three questionnaire surveys with 765 responses from 2020 to 2023 in China. Overall, it was proved that introducing TCM theories, including pathogenic factors, constitutions, and health preservation principles, would enable a better understanding of diverse occupant demands and facilitate the design of indoor environment control strategies. The conclusions of this study are as follows:

- Question 1: Notable indoor–outdoor temperature, humidity, and air movement gaps existed in modern buildings due to air conditioning. The maximum observed real time indoor–outdoor temperature and absolute humidity differences were 12.2 °C and 13.6 g/m3. Such gaps added to the thermal regulation stress of occupants. Yin summer-heat risks associated with cold and wind excesses existed even in so-called “neutral” air-conditioned environments.

- Question 2: Individual of different constitutions in Chinese medicine usually presented varied adaptive behaviors and environment perceptions. Individuals who were vulnerable to cold or wind excesses, such as DHC, etc., would suffer from yin summer-heat symptoms in air-conditioned environments to different extents. A personalized threshold system based on constitution typology is recommended.

The novelty of this study is the firsthand data to demonstrate the inspiration of TCM theories for indoor environment control. Also, the constitutions in Chinese medicine and associated pathogenic excesses enable a much more systematic interpretation of the heterogeneity of occupant demands and potential health risks related to environmental factors. The findings will facilitate the development of user-tailored IEQ control targets and personalized environment control technologies. Moreover, this study is limited in the sample size. Further exploration of other TCM knowledge, such as the nine-palace–eight-wind theory and the 24 solar terms, which are associated with environment adaptation, is expected to inspire interesting reflections on indoor environment control in modern buildings.

When referencing certain philosophical ideas and methodologies from Chinese classical literature or traditional Chinese medicine, the quantitative scientific evidence remains insufficient. Extensive scientific validation is required to transition from empirical discourse to scientific substantiation. Key questions for future research include how to effectively utilize the clinical samples accumulated in traditional Chinese medicine and how to translate these into regulatory threshold indicators for engineering applications in the field of built environments. These issues will undoubtedly become critical areas for investigation and validation in the years to come.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by S.X., J.D. and B.C. The first draft of the manuscript was written by J.D. and S.X. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 51978121, and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number DUT23RC(3)036.

Data Availability Statement

Data are unavailable due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Contents and example questions in questionnaire surveys.

Table A1.

Contents and example questions in questionnaire surveys.

| Aspect | Contents or Example Questions | Answers |

|---|---|---|

| a. Demographic and physiological characteristics | Age | / |

| Gender | Male/female | |

| City of residence | / | |

| b. Cooling-related adaptive behaviors | What will you do when you feel hot recently? | Open windows/adjust clothes/turn on AC/take cold drinks, etc. |

| What will you do when returning from the outside? | ||

| How will you rank the following cooling measures? | ||

| c. Wellness habits and TCM knowledge | Do you maintain a regular routine? | Frequency or agreement scales |

| How often will you work out? | ||

| Is it true that physical and mental status are related? | ||

| d. Indoor environment sensation, acceptance and preference | How do you feel about the temperature here and now? | Scales in reference to ASHRAE standards, etc. |

| How do you feel about the humidity here and now? | ||

| How do you feel about the air velocity here and now? | ||

| e. Illness symptoms indoors | Have you been sweating a lot recently? | Yes or no or scales |

| Do you have following symptoms recently? | ||

| Do you often feel tired in summer? | ||

| f. Test of constitutions in Chinese medicine | Do you have cold hands and feet? | Frequency scales |

| Do you feel your hands and feet hot? | ||

| Do you get tired easily? |

Notes: three questions from each aspect are shown as examples in this table.

References

- Ebi, K.L.; Capon, A.; Berry, P.; Broderick, C.; de Dear, R.; Havenith, G.; Honda, Y.; Kovats, R.S.; Ma, W.; Malik, A.; et al. Hot weather and heat extremes: Health risks. Lancet 2021, 398, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, J.; Quijal-Zamorano, M.; Méndez Turrubiates, R.F.; Pegenaute, F.; Herrmann, F.R.; Robine, J.M.; Basagaña, X.; Tonne, C.; Antó, J.M.; Achebak, H. Heat-related mortality in Europe during the summer of 2022. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1857–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, F.M.; Leow, M.K.S.; Lee, J.K.W.; Kovats, S.; Elajnaf, T.; Kennedy, S.H.; Thakker, R.V. Endocrine effects of heat exposure and relevance to climate change. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2024, 20, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.; Lawrance, E.L.; Roberts, L.F.; Grailey, K.; Ashrafian, H.; Maheswaran, H.; Toledano, M.B.; Darzi, A. Ambient temperature and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e580–e589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.; Deng, L.; Wang, T.; Xu, H.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Yu, L.; Chen, B.; Huang, L.a.; Qu, Y.; et al. Humid heat environment causes anxiety-like disorder via impairing gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism in mice. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Yu, Z.; Xu, C.; Manoli, G.; Ren, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yin, R.; Zhao, B.; Vejre, H. Climatic and Economic Background Determine the Disparities in Urbanites’ Expressed Happiness during the Summer Heat. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 10951–10961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Sustainable, Affordable Cooling Can Save Tens of Thousands of Lives Each Year; IEA: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Energy Efficiency 2023; IEA: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alnuaimi, A.; Natarajan, S.; Kershaw, T. The comfort and energy impact of overcooled buildings in warm climates. Energy Build. 2022, 260, 111938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cândido, C.; de Dear, R.; Lamberts, R.; Bittencourt, L. Cooling exposure in hot humid climates: Are occupants ‘addicted’? Archit. Sci. Rev. 2010, 53, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, N.; Peng, J.; Li, J. Effect of long-term indoor thermal history on human physiological and psychological responses: A pilot study in university dormitory buildings. Build. Environ. 2019, 166, 106425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, R.F.; Kim, J.; Ghisi, E.; de Dear, R. Thermal sensitivity of occupants in different building typologies: The Griffiths Constant is a Variable. Energy Build. 2019, 200, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, B.; Kim, J.; de Dear, R. A/C usage intensity and adaptive comfort behaviour in residential buildings in South East Queensland, Australia. Energy Build. 2024, 317, 114407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonocore, C.; De Vecchi, R.; Scalco, V.; Lamberts, R. Influence of recent and long-term exposure to air-conditioned environments on thermal perception in naturally-ventilated classrooms. Build. Environ. 2019, 156, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Khan, A. Thermal comfort of people from two types of air-conditioned buildings—Evidences from chamber experiments. Build. Environ. 2019, 162, 106287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Dear, R.; Xiong, J.; Kim, J.; Cao, B. A review of adaptive thermal comfort research since 1998. Energy Build. 2020, 214, 109893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Ji, W.; Deng, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S. A review of dynamic thermal comfort influenced by environmental parameters and human factors. Energy Build. 2024, 318, 114467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; de Dear, R.; Ji, W.; Bin, C.; Lin, B.; Ouyang, Q.; Zhu, Y. The dynamics of thermal comfort expectations: The problem, challenge and impication. Build. Environ. 2016, 95, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, M.J.; Pickering, C.A.C. Building related illness. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1986, 16, 387–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redlich, C.A.; Sparer, J.; Cullen, M.R. Sick-building syndrome. Lancet 1997, 349, 1013–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzi, G.; Abbritti, G.; Accattoli, M.P.; dell’Omo, M. Prevalence of irritative symptoms in a nonproblem air-conditioned office building. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 1998, 71, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.H.; Huang, B. Comparative study of the indoor air quality of naturally ventilated and air-conditioned bedrooms of residential buildings in Singapore. Build. Environ. 2004, 39, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Shang, Q.; Dai, Z.; Zhu, Y. The Impact of Air-conditioning Usage on Sick Building Syndrome during Summer in China. Indoor Built Environ. 2012, 22, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukawa, Y.; Murakami, R.; Ichinose, M. Field study on occupants’ subjective symptoms attributed to overcooled environments in air-conditioned offices in hot and humid climates of Asia. Build. Environ. 2021, 195, 107741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chen, H.; Yuan, Y.; Song, C. Indoor thermal environment and human health: A systematic review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 191, 114164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ouyang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Shen, H.; Cao, G.; Cui, W. A comparison of the thermal adaptability of people accustomed to air-conditioned environments and naturally ventilated environments. Indoor Air 2012, 22, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zheng, X.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, C.; Yang, Z.; Qian, H. Unraveling the link between draught and upper respiratory mucosal immunity: Assessing lysozyme and S-lgA concentrations in nasal lavage fluid. Build. Environ. 2024, 254, 111379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graudenz, G.S.; Landgraf, R.G.; Jancar, S.; Tribess, A.; Fonseca, S.G.; Faé, K.C.; Kalil, J. The role of allergic rhinitis in nasal responses to sudden temperature changes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lian, Z.; Zhou, X.; You, J.; Lin, Y. Effects of temperature steps on human health and thermal comfort. Build. Environ. 2015, 94, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lian, Z.; Zhou, X.; You, J.; Lin, Y. Potential indicators for the effect of temperature steps on human health and thermal comfort. Energy Build. 2016, 113, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. Reserving or disposing the expression of “yin summer-heat” as a disease name. Shaaxi J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 1980, 6, 33–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F. Investigatin on Clinical Features of Summer-Heat Disease. Master’s Thesis, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China, 2009. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G. Suggestions to keep yang-related wellness in the view of treating yin summer-heat syndromes of 120 cases. J. Pract. Tradit. Chin. Intern. Med. 1997, 2, 11–12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S. Features and treatment of yin summer-heat diseases. J. Nanjing Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 1999, 6, 330. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zheng, X. Initial Research of Air-Conditioning Disease on Etiology and Pathogenesis Aspects of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Liaoning J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2015, 42, 68–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Theoritical Invesitigation on Summer-Heat Diseases. Master’s Thesis, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China, 2015. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Sun, L.; Li, C. The Six Pathogenic Factors in Huangdi Neijing: Origins and Clinical Implications. Chin. Arch. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2006, 24, 2. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; de Dear, R.; Luo, M.; Lin, B.; He, Y.; Ghahramani, A.; Zhu, Y. Individual difference in thermal comfort: A literature review. Build. Environ. 2018, 138, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZYYXH/T157-2009; Identification and Classification of Constitution of TCM. China Association of Chinese Medicine: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Wang, Q. Identification of the Nien Constitutions in Chinese Population; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2011. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- WPS Office Development Team. WPS Office, Version 12.0; Kingsoft Office Software Corporation Limited: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Research on the Field Evidence of Environmental AdaptabilityBased on CTCM; Dalian University of Technology: Dalian, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W. Applied Basic Research Based on the Demand of Indoor Environment for TCM Health Preservation; Dalian University of Technology: Dalian, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- QX/T500-2019; Evaluation Method of Climate Suitability for the Cool Summer Tourism. China Meteorological Administration: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Li, H.; Huang, J.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Yang, L. A new TMY generation method based on the entropy-based TOPSIS theory for different climatic zones in China. Energy 2021, 231, 120723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medicine, N.U.O.C.; Veith, I. The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine; University of California Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Z.; Xie, Y.; Cao, B.; Zhu, Y. A study of the characteristics of dynamic incoming flow directions of different airflows and their influence on wind comfort. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE Handbook: Fundamentals; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc.: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021.

- Zander, K.K.; van Hoof, J.; Carter, S.; Garnett, S.T. Living comfortably with heat in Australia—Preferred indoor temperatures and climate zones. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 96, 104706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Chen, B. Indoor thermal environment and adaptive behaviors in summer of urban households in northern China: Status and trend. Energy Build. 2024, 324, 114916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, O.; Capon, A.; Berry, P.; Broderick, C.; de Dear, R.; Havenith, G.; Honda, Y.; Kovats, R.S.; Ma, W.; Malik, A.; et al. Reducing the health effects of hot weather and heat extremes: From personal cooling strategies to green cities. Lancet 2021, 398, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, L.; Strengers, Y. Air-conditioning and antibiotics: Demand management insights from problematic health and household cooling practices. Energy Policy 2014, 67, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, S.; Liu, R.; Liang, S.; Liu, G.; Tong, L. Study on the relationship between thermal comfort and S-IgE based on short-term exposure to temperature. Build. Environ. 2022, 216, 108983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z. Revisiting thermal comfort and thermal sensation. Build. Simul. 2024, 17, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; O’Neill, Z.; Wen, J.; Dong, B. From occupants to occupants: A review of the occupant information understanding for building HVAC occupant-centric control. Build. Simul. 2022, 15, 913–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wang, F.; Zhao, S.; Gao, S.; Yan, H.; Sun, Z.; Lian, Z.; Duanmu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; et al. Comparative analysis of indoor thermal environment characteristics and occupants’ adaptability: Insights from ASHRAE RP-884 and the Chinese thermal comfort database. Energy Build. 2024, 309, 114033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-2020; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc.: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020.

- EN 15251-2007; Indoor Environmental Input Parameters for Design and Assessment of Energy Performance of Buildings Addressing Indoor Air Quality, Thermal Environment, Lighting and Acoustics. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2007.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).