1. Introduction

The exhibition

La modernité, un projet inachevé: 40 architectures (The Modernity, an unfinished project: 40 architectures) (

Figure 1) (

Chemetov and Garcias 1982), curated by Paul Chemetov and Jean-Claude Garcias and held in the Palais des études of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris between 30 September and 15 November 1982 in the framework of the Festival d’Automne, aimed to show that, in contrast with the international context, the modern tradition in France was not characterised by continuity. This hypothesis could be opposed to Walter Gropius’s view in (

Gropius 1964) “Tradition and Continuity in Architecture”, published in

Architectural Record in 1964. Chemetov and Garcias, through the aforementioned exhibition, aimed to address the role of architects within a generalised context of massification of their action. As Paul Chemetov underlines in the catalogue, one of the main objectives of the exhibition was to show that “for France, Jean-Paul Sartre’s

Critique de la raison dialectique rose up against the socialist complex of progress and against the one-dimensionality […] of historical materialism” (

Sartre 1960;

Chemetov 1982a). Α question that dominated architectural discourse during the years of the crisis of modernity concerned the ways in which these changes influenced the status of architecture as an art representative of culture and history. Relevant for understanding the view developed by Chemetov and Garcias in the aforementioned exhibition was Sartre’s conception of the engaged intellectual. According to Sartre, the intellectual’s engagement should be understood as linked to the human condition. More specifically, for Sartre, the intellectual is a restless soul who feels ill at ease in the society of his time because he no longer wants to express the objective spirit of his class or to put his universal knowledge at the service of particular interests.

The catalogue of the exhibition

La modernité, un projet inachevé: 40 architectures included Kenneth Frampton’s “Réfléxions sur l’état de la modernité: fragments polémiques” (

Frampton 1982), Jean-Claude Garcias’s “La modernité la plus récente” (

Garcias 1982), Jürgen Habermas’s “L’autre tradition” (

Habermas 1982), and “Le postmodernisme ou la peur des conflits” (

Schmidt 1982,

1986) by German philosopher Burghart Schmidt. It concluded with a text by Paul Chemetov entitled “Inachevé, parce qu’inachevable” (

Chemetov 1982a), in which the author suggested readdressing the questions raised by the modern movement through a critical re-evaluation of its strategies. Reading “La Biennale de Venise: crise et ornements”, published in

Techniques & Architecture in October 1982 (

Chemetov 1982b, p. 152)—that is to say, the same year that

La modernité, un projet inachevé: 40 architectures was held—one is confronted with the anti-postmodernist view of Chemetov.

The same year as

La modernité, un projet inachevé: 40 architectures, another exhibition also took place in Paris, this time at the Centre Pompidou:

La modernité ou l’esprit du temps (

Modernity or the spirit of the times) (

Nouvel et al. 1982), curated by Jean Nouvel, Patrice Goulet, and François Barré. Comparing the arguments of the two exhibitions could help us to grasp the tension between the modernist and postmodernist stance in architecture within the French context during the early 1980s. The debate represented by the contrast between

La modernité, un projet inachevé: 40 architectures and

La modernité ou l’esprit du temps (

Figure 2) is linked to the emergence of two trends in relation to the reinvention of modernity. Following Pierre Bourdieu’s approach, we could claim that the tension between the ways in which each of these exhibitions treats the role of the image within architectural design and the role of architecture for the construction of a vision regarding progress is the expression of two divergent positions in social space (

Bourdieu 1979,

1987;

Grenfell 2014).

The tension between the approaches of the two exhibitions is related to how their curators interpret Team Ten’s approach. Jean Nouvel claimed, in his text for the catalogue of

La modernité ou l’esprit du temps, that being “[m]odern today is not holding the torch of the modern movement, Team Ten or ‘ordinary ugliness’” (

Nouvel 1982), while Paul Chemetov was positive towards the ideas of Team Ten and the intention of its members to understand habitat as a place for social interaction. To compare the approaches of the Atelier d’urbanisme et d’architecture (AUA) and Team Ten, it would be useful to interpret their differences as part of a generational conflict through the elaboration of concepts first developed by Karl Mannheim, in

Le Problème des générations (

Mannheim [1928] 2011). It also explains why the discourse of Team Ten is less critical vis-à-vis the generation of modernism than that of the AUA. A question that could be useful for better grasping the tension between Jean Nouvel’s approach and that of the AUA is whether the break with the founding myths of modernity is rather a generational rupture than a conceptual one. This question is related to another interrogation asking whether the demystification of modernism is a generational or a conceptual stance.

Paul Chemetov was set against the autonomy of architecture as a discipline. His rejection of architectural autonomy should be interpreted in conjunction with his political agenda (

Chemetov 1981). Chemetov argued that the city should be understood as a “long-term formation” and a territory enhancing sociability “braced on time” (

Chemetov 1995). Chemetov’s interest in duration contrasts with Jean Nouvel’s call to use “the full potential of the present time” (

Nouvel 1982). Nouvel remarked, in his text for the catalogue of the exhibition

La modernité ou l’esprit du temps, “if anything characterises our recent past, it is the extraordinary development of the image through new referents” (

Nouvel 1982). In opposition to Nouvel, Chemetov was sceptical vis-à-vis the image, criticising the reduction of the building to the object of art. Nouvel related modernity to inventiveness, and to its capacity to use “the potential of present time, […] connecting information, [and] creating an effect of synergy between the most recent and the most remote data” (

Nouvel 1982). He paid particular attention to the role of imagination in reshaping reality and claimed that modernity should be opposed to academicism. Provocatively enough, he underscored that “[b]eing modern means having a sense of history, knowing that ‘the present moment of bygone days is no longer the present moment of today’” (

Nouvel 1982). He associated modernity with the desire to question truth, and to reject the obvious. In parallel, Nouvel was convinced that “an architectural attitude [is] rich when it is meaningful, when it becomes critical, political and consequently aesthetic and poetic events” (

Nouvel 1984) (

Figure 3).

The point of view characterising

La modernité ou l’esprit du temps could be compared to the approach developed by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour in

Learning from Las Vegas in 1972 (

Venturi et al. 1972), insofar as they shared an interest in the role of the image for the epistemological shift in architecture (

Figure 4). However, Jean Nouvel had misinterpreted Robert Venturi’s stance vis-à-vis modernism, since he claims the following, which stands in contrast with what Venturi had remarked in his article entitled “Une définition de l’architecture comme abri décoré” in

L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui (

Venturi 1978a):

Venturi does not retain any achievements of the Modern Movement. His analysis leads to an overall negative result. And his attitude hardened ten years later with his second book, in which he denounced pure innovative architecture, abstraction, the creative, new words, the extraordinary, the heroic, the consistent, the advanced technologies, the interesting, for the benefit of the mixture of means of expression, the conventional, conventional technology, the inconsistent, the boring.

2. Europa-America: Architettura Urbana, Alternative Suburbane

An exhibition that is pivotal for relating the tension between modernism and postmodernism to an understanding of the break with the founding myths of modernity as a generational rupture is

Europa-America: Architettura urbana, alternative suburbane (

Raggi 1978), held in the framework of the Biennale di Venezia of 1976 (31 July–10 October) and curated by Vittorio Gregotti. According to the latter, this exhibition aimed to shed light on the dialectic process of existent reality. The title that was originally chosen for the exhibition was

Europa-America: Centro storico-suburbio. Joseph Rykwert was at the time a member of the advisory board of the Biennale. The exhibition was organised in two sections: one was American, the other European. AUA was among the participants to the European section. The American section was entitled “Alternatives: Eleven American Projects” and directed by Peter Eisenman. Among the projects exhibited in the American section were “Seven Gates to Eden” by Raimund Abraham, “House X” by Peter Eisenman, and “The Silent Witnesses” and “Suburban Houses” by John Hejduk. The architects that contributed to the European section were invited to respond to the topic “historical centre” (“centro storico”), while the architects of the American section dealt with the topic “suburbs” (“suburbio”). The participation of the international and, particularly, of the American architects in

Europa-America: Architettura urbana, alternative suburbane should be interpreted in relation to

Architettura Razionale, curated by Aldo Rossi, an exhibition in the framework of the 1973 Triennale (

Bonfanti et al. 1973), which could be considered for Europe as the first real gathering of the "non-modern Internationale" and an event with long-term effects.

Gregotti, in his introduction to the catalogue of

Europa-America: Architettura urbana, alternative suburbane, tried to explain the dialectic strategy of the chosen title. He also aimed to describe the tendencies that characterised the epistemology of architecture at the time. He discerned two main tendencies opposed to one another. On the one hand, a tendency that “is destined to dissolve the constructed architecture as a discipline no longer significantly communicating, immersed in a sort of new everyday life, behaviours where objects seem to have lost their original and instrumental sense to constitute themselves as means of an ecstatic communication, awaiting a new chiliastic society or, turning to the interior, abandoning the earthly competition” (

Gregotti 1978, p. 7). On the other hand, a tendency that is based on “an analysis and a radical reduction of the elements considered to be disciplinary, the value of the architecture accentuated with its traditional symbolic characters, its building substance” (

Gregotti 1978, p. 7).

The analysis of this exhibition and of the debate that took place within its framework is useful for two reasons: firstly, it is a testimony of the tensions that characterised exchanges between Europe and the United States concerning architectural epistemology; secondly, it also reveals the conflicts that characterised the relationship between two successive generations. The title of the debate that took place on 1 August 1976, the day of the exhibition’s opening—“Quale Movimento Moderno?” (“Which Modern Movement?”)—is symptomatic of the growing discontent with the idea of modernism, which had been apparent since the 1950s (

Figure 5). Among the participants in the exhibition were certain figures of Team Ten, such as Giancarlo De Carlo, Alison and Peter Smithson, and Aldo van Eyck. De Carlo and van Eyck were the oldest participants. Manfredo Tafuri also took part in the debate. During the latter, Denise Scott Brown remarked that “[m]odern architecture […] was a very great revolution and […] in line with changes of the time”. Scott Brown also wrote a text entitled “L’architettura simbolica del suburbio Americano” (“The Symbolic Architecture of American Suburbs”) for the catalogue of the exhibition

Europa-America: architetture urbane, alternative suburbane. In an excerpt from this text devoted to the role of form and symbol for architecture, she remarked: “Architecture is perceived as a form and a symbol. Modern architects and urban planners have highlighted the formal and spatial qualities of architecture more than its symbolic qualities. Modern theorists have analyzed functionality and aesthetics rather than the symbolic meaning of form and space. […] we have tried to restore the balance between form and symbolism” (

Scott Brown 1978) (

Figure 6).

3. La Modernité ou L’Esprit du Temps

The jury that selected the works displayed at the exhibition

La modernité ou l’esprit du temps included François Barré, Olivier Boissière, Patrice Goulet, Pierre Granveaud, Damien Hambye, and Luciana Miotto (

Ellin 1996, p.55). The main criterion for the selection of the works was their capacity to defend modernism, but in a way that took distance from doctrine and dogmatism. Jean Baudrillard contributed to the exhibition catalogue with two texts: “Modernité” (“Modernity”) and “Fin de la modernité ou l’ère de la simulation” (“End of modernity or the era of simulation”) (

Baudrillard 1982a,

1982b). In the latter text, he argued that the opposition between the modern and the traditional was no more relevant. He also claimed that modernity no longer existed and that everything was inscribed within the framework of the distinction between the current and the retro (

Baudrillard 1982b). In the same text, Baudrillard maintained that “modernity was a project of universality based on a dialectical movement—movement of discourse, of techniques, of history—which was determined by a progressive finality” (

Baudrillard 1982b). Baudrillard did not refer to “a crisis of modernity, but an end of it” (

Baudrillard 1982b).

In contrast with Baudrillard, who related the end of certainties to the belief in universal ideas and progress, Gilles Deleuze associated the failure of such certainties—referring mostly to the failure of representation—to the project of modern thought as it is evidenced in what he wrote in 1968, in the foreword to his book

Différence et Répétition (

Difference and Repetition)

, where he claimed that “modern thought [was] […] born of the failure of representation, of the loss of identity, and of the discovery of the forces that act under the representation of the identical [, and that] […] modern world is one of simulacra” (

Deleuze 2004, xvii;

1968). Adopting a similar attitude as Jean Baudrillard, François Barré concluded his text entitled “Fréquence Modernité”, which was written for the catalogue of

La modernité ou l’esprit du temps, shedding light on the necessity to “leave behind the old debate of the moderns […] and observe the city which is expanding and decentralizing within itself” (

Barré 1982, p. 19). The catalogue also included two interesting conversations: one between Robert Venturi and Peter Eisenman, and one between Cedric Price and Lucien Kroll. The former conversation had previously been published in English in 1982, in

Skyline, a journal published by the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies. In this conversation, Venturi underlined his view that the aesthetic and ideological aspects of architecture are closely interlinked (

Venturi and Eisenman 1982).

Among the contributors to the exhibition

La modernité ou l’esprit du temps, curated by Jean Nouvel, Patrice Goulet, and François Barré, was Rem Koolhaas, who, with Stefano de Martino and Kees Christiaanse, exhibited three projects: their proposal for a housing complex in Berlin on Koch-Friedrich Strasse (

Figure 7), situated in front of Checkpoint Charlie; a project concerning a Skyscraper and a tower in Rotterdam, which were conceived as parts of a broader programmatic redevelopment around the river; and their proposal for a theatre complex for a dance company in The Hague. Koolhaas, de Martino, and Kees Christiaanse, who worked for the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) in Rotterdam, opened their text for the exhibition catalogue with the observation that the temporal context within which the aforementioned projects should be interpreted is characterised by a situation within which the emblems of “universality, truth, dogma, [and] new beginnings […] [were adopted or even] […] usurped”

1 by the non-moderns.

Rem Koolhaas, Stefano de Martino, and Kees Christiaanse saw this situation as an opportunity of liberation for modern architecture, referring to the possibility of a “new” modern architecture characterised not only by intelligence and programmatic imagination, which were some of the virtues of the old or traditional modern architecture, but also by certain attributes which rendered popular the adversaries of modern architecture. More specifically, in their text for the catalogue, they argued that this “new” modern architecture should not intend “to conquer the whole world […], [but should] concentrate on the establishment of islands—hermetic, autonomous, seductive episodes—every time unique and different—forming together an archipel of modernities, of which the success is guaranteed by [adapting some of the notions characterizing the approaches of the] […] anti-moderns” (

Koolhaas et al. 1982). Koolhaas, de Martino, and Christiaanse chose to display the aforementioned three projects because they were convinced that they represented a shift from the old or traditional modernity to the “new” one. For them, the common denominator of these three projects is their capacity to function as “programmatic and formal injections based on a fascinated interpretation of their respective contexts in which they are called to ‘work’” (

Koolhaas et al. 1982).

OMA had also contributed to

La presenza del passato, curated by Paolo Portoghesi (

Pirovano 1980). The exhibition included the famous 70-metre pedestrian path—

La strada novissima—consisting of facades designed by Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura (RBTA), Costantino Dardi, Frank O. Gehry, Michael Graves, Gruppo romano architetti urbanisti (GRAU), Allan Greenberg, Hans Hollein, Arata Isozaki, Josef Paul Kleihues, Rem Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis, Léon Krier, Charles W. Moore, Paolo Portoghesi with Francesco Cellini and Claudio D’Amato, Franco Purini and Laura Thermes, Massimo Scolari, Thomas Gordon Smith, Robert A. M. Stern, Stanley Tigerman, Oswald Mathias Ungers, and Robert Venturi with Denise Scott Brown and John Rauch. Despite the diversity of the architects that participated in the design of

La strada novissima, no French contributors feature among them. However, Christian de Portzamparc “was also part of the group but withdrew at the last moment, deciding that his façade should not be built inside the Arsenale. Therefore, Portoghesi’s facade, first designed as the entrance portal to the street, was built in place of Portzamparc’s façade” (

Szacka 2011, p. 203).

4. From La Presenza del Passato to Présence de L’Histoire

The French version of

La presenza del passato was held between 15 October and 20 December 1981 at the Chapelle de la Salpêtrière in Paris under the title

Présence de l’histoire, l’après modernisme (

Presence of History: The After Modernism) (

Guy 1981). Among its contributors were Paolo Portoghesi, Ricardo Bofill, Michael Graves, Hans Hollein, Léon Krier, Fernando Montès, Charles W. Moore, Christian de Portzamparc, Franco Purini, Robert Stern, and Oswald Mathias Ungers, among others. Fernando Montès, Manolo Nunez, and Christian de Portzamparc, despite the fact that they were not among the contributors to

La strada novissima of the Venice Biennale of architecture of 1980, were involved in

Présence de l’histoire, l’après modernisme.

An important instance for comprehending the relationship between architecture and politics in the early eighties is the “Charte de Solidarité” or “Charte à Varsovie”, referring not only to the status of Warsaw as a city destroyed during the war, but most importantly to “the encounter of modern doctrine with that of the totalitarian socio-political system”. This document was conceived as an expression of the position that “architecture can only be beautiful and humane when it is created by free citizens in the service of a free society”

2. During the 14th World Congress of the International Union of Architects (UIA), which was convened in Warsaw between 15 and 21 June 1981 under the motto “Architecture–Man–Environment” (

Ziolkowska-Boehm 2018, p. 72), a declaration authored by a group of young Polish architects was distributed in the framework of the seminar “Home and City” (DiM). This declaration, which is known as the “The Warsaw Declaration of Architects”, contained a critique of the 1933 Athens Charter and was opposed to the official position of the 14th World Congress of Architects, which recognised the 1933 Athens Charter as a starting point for architecture and urban planning. It would be interesting to question to what extent the theses of the Warsaw Declaration of Architects were consistent with those of Charles Jencks and Paolo Portoghesi. To grasp the symbolic dimension of the “The Warsaw Declaration of Architects”, one should bear in mind that it was issued eight years before the fall of the Berlin Wall, which took place on 9 November 1989.

The events that took place in conjunction with the exhibition

Présence de l’histoire, l’après modernisme included a debate organised by the architectural magazine

Techniques & Architecture with the participation of Paul Chemetov, Stanislaus von Moos, and Bruno Zevi, who were openly opposed to postmodernist architecture. Chemetov and Zevi’s participation in an event that was part of

Présence de l’histoire, l’après modernisme, which was an exhibition celebrating postmodernist architecture, is striking given that both Chemetov and Zevi rejected postmodernism. Zevi’s presence in the debates that were taking place in France during the early 1980s could, however, explain why he was invited. I could refer, for instance, to the fact that Zevi also contributed, two years later, to the catalogue of the exhibition

Architectures en France: Modernité/post-modernité with an essay entitled “Avenir de l’architecture française” (“Future of French Architecture”), which opened with the following declaration: “I am resolutely optimistic about the prospects for modern architecture in France” (

Zevi 1981). He related his optimism to the political situation and horizons within the French context. In his very personal text, with a tone that brings to mind autobiographical narratives, he declares: “In particular, I would like to see the two necrophilic movements of classicist neo-academism and irresponsible post-modern levity run out of steam as quickly as possible” (

Zevi 1981).

In “Les refusés du post-modernisme”, published in

Techniques & Architecture in December 1981, Stanislaus von Moos remarked that the approach of Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Rauch differed from the postmodern orthodoxy in the sense that it is based on an intense dialogue with the tradition of modern architecture and not against it. According to von Moos, Venturi was influenced by Louis Kahn, Le Corbusier, and Alvar Aalto. Von Moos, in the aforementioned article, claimed that postmodernist architecture became even more dogmatic through the transfer of ideas from its version in

La presenza del passato to other European contexts, such as the French one. More specifically, he remarked regarding this issue: “This dogmatic attitude, this amnesia—coupled with a generally arbitrary historicism—seems to have been further reinforced within the postmodern European elite.” (

Von Moos 1981, p. 104) Von Moos also claimed that “[t]he transformation that the exhibition ‘La presenza del passato’ underwent between Venice (1980) and Paris (1981)” (

Von Moos 1981, p. 104). He concluded his provocative essay with the following thought-provoking remarks: “Faced with the Parisian version of ‘La presenza del passato’ a question arises: is it true that the postmodern has entered its orthodox, dogmatic phase, in which we move to the exclusion of positions deemed revisionist? […] Would it be true that Paris, once again, is appropriating an avant-garde as it is becoming retro-grade?” (

Von Moos 1981, p. 105).

Despite the intention of its curators to present La Modernité, un projet inachevé: 40 architectures as an anti-postmodernist exhibition, it included amongst its contributors Josef Paul Kleihues and Arata Isozaki, who were both among the designers of the facades of La strada novissima. Paul Chemetov and Jean-Claude Garcias invited Kleihues to exhibit his proposal for a hospital extension in Berlin Neukölln (1972–1983), and Isozaki to exhibit his proposal for the Town hall of Kamiaka (1976–1978). The only architect to contribute to La modernité ou l’esprit du temps while also having participated in the design of the facades of La strada novissima was Rem Koolhaas. The contributors to Europa-America: Architettura urbana, alternative suburbane who also took part in the design of the facades of La strada novissima four years later were Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura (RBTA), Hans Hollein, Robert Venturi with Denise Scott Brown and John Rauch, Charles W. Moore, Robert A. M. Stern, Stanley Tigerman, and Oswald Mathias Ungers.

The contributors to

La Modernité, un projet inachevé: 40 architectures who also took part in

Europa-America: Architettura urbana, alternative suburbane six years earlier were Alison and Peter Smithson, and Alvaro Siza. In parallel, Vittorio Gregotti, who was the curator of

Europa-America: Architettura urbana, alternative suburbane, took part in

La Modernité, un projet inachevé: 40 architectures, exhibiting his design for the Department of Sciences of the University of Palermo (1969–83). That same year—in 1982—Vittorio Gregotti was appointed director of

Casabellà, and his book

Il territorio dell’archittetura was translated to French (

Gregotti 1966,

1982). The AUA also exhibited their work in

Europa-America: Architettura urbana, alternative suburbane. Richard Meier and Raimund Abraham, who had contributed

to Europa-America: Architettura urbana, alternative suburbane, also took part in

Nouvelles Directions de l’Architecture Moderne:

France/USA. An event that is enlightening for deciphering what was at stake concerning the tension between modernism and postmodernism within the French context in the early eighties is the debate between Paul Chemetov, Jean-Louis Cohen, Vittorio Gregotti, Christian de Portzamparc, and Henri Gaudin, devoted to the theme “En route pour l’architecture” in the framework of the televisual series “Aux arts! Citoyens!”, in April 1982.

To better understand the divergences and affinities between the attitudes of Nouvel and Chemetov regarding the commoditisation and aestheticisation of the image and their perception of architectural signs, one could bring to mind the well-known controversy between Jürgen Habermas (

Habermas 1981) and Jean François Lyotard (

Lyotard 1982). According to the former, modernity was an unfinished project, while, according to the latter, modernity was an outdated project. The contrast between Habermas and Lyotard’s view of modernity is related to the crisis of the idea according to which architectural language must symbolise and embody the essence of the time, the

Zeitgeist. Their disagreement concerns the question of the end or the continuation of modernity. According to Habermas, the project for the emancipation of modernity should not be abandoned. Habermas’s critiques of postmodernity are associated with his disapproval of Lyotard’s stance towards aesthetic modernity. Habermas criticised Lyotard for abandoning the idea that modernity can still bring about changes in the lived world and everyday life. Another important aspect for understanding the divergences of the positions of the architects towards postmodernism is their political positions. For instance, Paul Chemetov supported the French Communist Party (PCF), while Nouvel favoured the “gauche ‘alternative’” and “tendance”.

5. Between the Contextualist and the Populist Approach

To better grasp the specificity of the French context in the early 1980s, it is important to take into account two tendencies that were present in architectural debates during the 1970s: the contextualist approach, on the one hand, and the populist approach, on the other. According to Joseph Abram’s remarks about the French context, “the generation of the 1970s was engulfed by a superficial return to the urban contextualism” (

Abram 1998, p. 352). Abram sustains that this “urban contextualism” that was dominant in the architectural debates in France during the seventies is closely related to the reinvented interest in history, which, to a certain extent, was part of the postmodernist posture as well. However, the most distinctive characteristic of this French “urban contextualist” is its intention to reveal the contradictions that determine the place in its history. The intensification of the interest in notions as that of “urbanity” (“urbanité”), which was the theme of the architectural section of the

Biennale de Paris: Manifestation international des jeunes artistes of 1980, and the territory, to which Zevi also refers in his text for the catalogue of

Architectures en France: Modernité/post-modernité in 1981, exemplify this intention. Useful for understanding the implications of the populist approaches is an article entitled “Promesses et impasses du populisme” (“Promises and dead ends of populism”) by Jean-Louis Cohen, in which the latter distinguishes two populist postures: on the one hand, a posture that aims at direct communication with the addressees of architecture, and on the other hand, a posture that focuses on the search for new modalities of the participation of the population in architectural production (

Cohen 2004). The participation of residents has been the subject of many experiments since the 1970s. Populism in architecture is linked to the shift away from elite figures, focusing on the expression of citizens. One question that emerges is whether populism is neutral in relation to architectural aesthetics. The dilemma between ethics and aesthetics pointed out by Reyner Banham in his book entitled

The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic? implies that the two terms are not mutually exclusive (

Banham 1966).

The first section of the Biennale de Paris:

Manifestation international des jeunes artistes, devoted to architecture, was held in 1980 with the theme

À la recherche de l’urbanité: savoir faire la ville, savoir vivre la ville (In search of urbanity: knowing how to do the city, knowing how to live the city). The exhibition, which was held between 24 September and 10 November 1980, brought together works from 15 national contexts, focusing on architects younger than forty (

D’Ornano 1980). One of the main criteria for selecting them was their interest in democratic “urbanity”, community identity, local spaces, and a “poetics of the city”. The argument of this exhibition was that a new conception of “urbanity” had emerged. The curators of the exhibition claimed that this new conception of urbanity was characterised by a “reaction against the ravages due to the current practices of urban planning of the ‘modern movement’ (massively applied during the 50s, 60s and 70s)”, on the one hand, and a disapproval of “the technocratic deviations resulting from the “Charter of Athens” (1933) or from various functionalist doctrines which favour the mechanistic, quantitative and materialist dimensions of cities and give rise through various “zoning to the segregation of men, the abusive fragmentation of spaces and the time”

3, on the other hand.

6. À la Recherche de L’Urbanité

In the press release of the exhibition

À la recherche de l’urbanité: savoir faire la ville, savoir vivre la ville, one can read that before the organisation of this Biennale, which for the first time included a section of architecture, not many international architects were invited to contribute to the Biennale, with the exception of British group Archigram, who had been invited to take part in the exhibition in 1967. However, until 1971, some architects, even if they did not have an international profile, contributed to the Biennale. In the case of the exhibition

À la recherche de l’urbanité: savoir faire la ville, savoir vivre la ville, the organising committee consisted of Jean Dethier, Damien Hambye, Luciana Miotto, and Jean Nouvel, while the Délégué Général de la Biennale de Paris was Georges Boudaille and the Advisor for architecture was François Barré. Jean Nouvel was also responsible for the design and layout of the exhibition in the Centre de Création Industrielle (CCI) gallery. Among the young architects who contributed to the exhibition were Gaetano Pesce, Yves Lion, Bernard Tschumi, Jorge Silvetti, and Fernando Montès, who, with Tschumi, had published “Do-It-Yourself-City” in

L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui in 1970 (

Montès and Tschumi 1970). Both Tschumi and Montès had worked for Candilis-Jossic-Woods in Paris in the early years of their career. Among the contributors to the catalogue of the exhibition were Jean Nouvel, with two essays entitled “Pourquoi choisir le thème de l’urbanité pour la 1ère exposition d’architecture de la Biennale?” and “L’impossible urbanité”, respectively; Bruno Zevi, with an essay entitled “Vers un nouvel urbanisme démocratique”; Maurice Culot, with a text entitled “La nostalgie, âme de la révolution”; and Gaetano Pesce, with an essay entitled “Urbanité?”.

7. The Controversy between Modernism and Postmodernism in France

The controversy between modernism and postmodernism was already at the centre of the exhibition

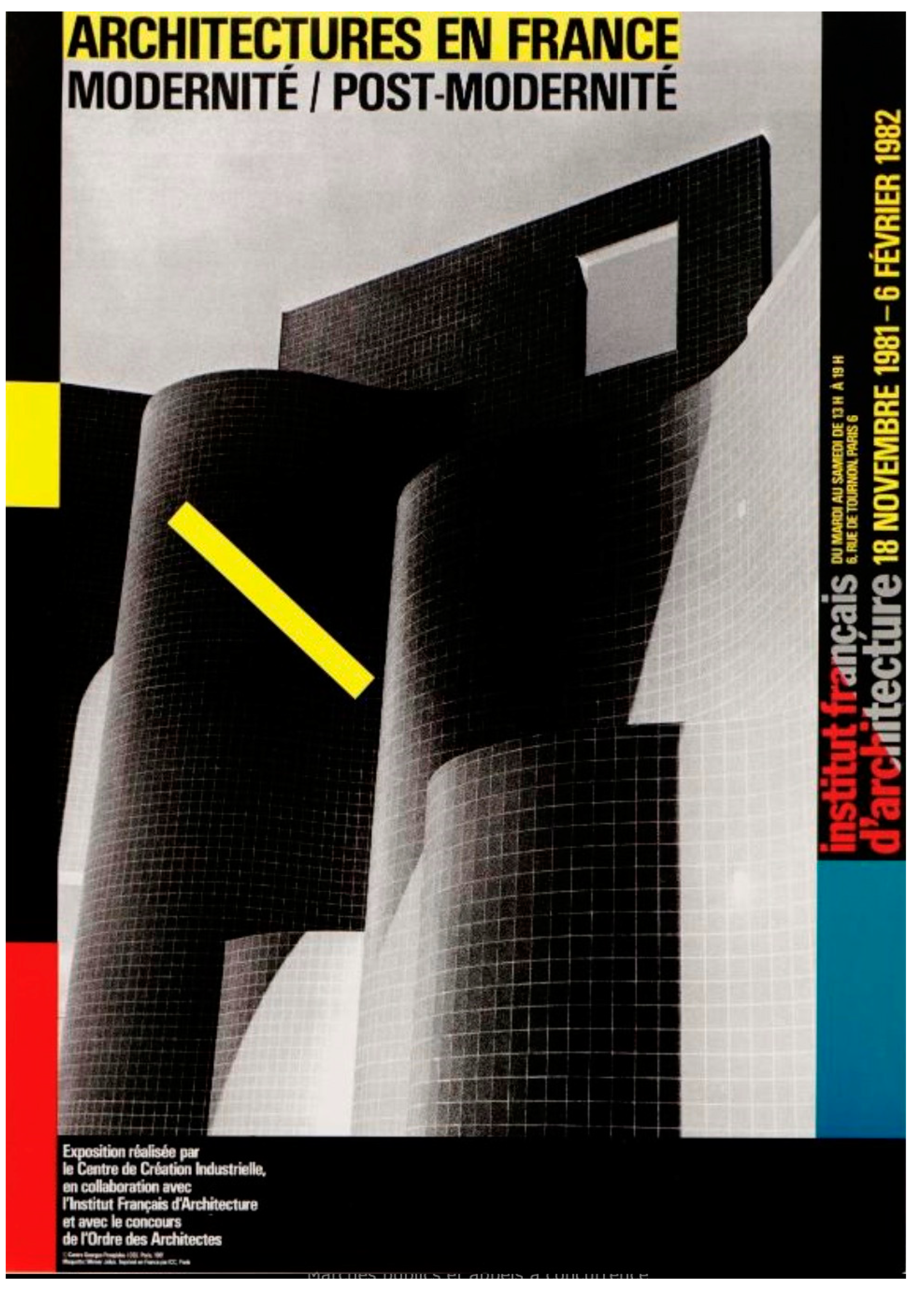

Architectures in France: Modernity/Post-modernity (

Architectures en France: Modernité/post-modernité) (

Figure 8), curated by Chantal Béret and held at the Institut Français d’Architecture from 18 November 1981 through 6 February 1982. Jean-Louis Cohen contributed to the catalogue with an insightful text entitled “Du dessin au chantier: Le printemps des doctrines”, where he related the architectural debates in France to the cross-fertilisation of the field of architecture with the following five fields of thought: history, the urban aspect or urbanity, the imaginary dimension, the modernity, and the construction (

Cohen 1981). Bruno Zevi, in his text for the exhibition catalogue, related “[t]he new social and political climate of [France] […] [to the] […] new confidence of architects in themselves, in society, in the role of architecture in contributing to change” (

Zevi 1981). He also encouraged French architects to take distance “from every academic canon, all post-modern loopholes, [and] all regionalist pettiness.” (

Zevi 1981) Zevi suggested certain directions that could function as antidotes against the dangers of postmodernism. These directions could be summarised in three main tendencies: firstly, a tendency departing from the intention to promote a flexible understanding of urban planning based on a broadened conception of “urbanity” (“urbanite”), which was the theme of the Biennale d’architecture in Paris a year before; secondly, a tendency based on the belief that a new language that aims to enhance flexibility of spaces could contribute to a fresh view of modern architecture, and, thirdly, a tendency based on the search for “a new meaning of architectural terms” (

Zevi 1981). Regarding the first tendency, Zevi highlights, in the aforementioned text, that French architects should try to “plan the territory and the city with breadth and flexibility” (

Zevi 1981). Concerning the second tendency mentioned above, Zevi underscores that French architects should “build in a contemporary language based on the flexibility of spaces” (

Zevi 1981).

Both Paul Chemetov and Jean Nouvel contributed to the catalogue of the exhibition

Architectures en France: Modernité/post-modernité, the former with an essay entitled “Une rude épreuve” (

Zevi 1981), and the latter with a text entitled “Oser l’ornement” (

Nouvel 1981). The curator of the exhibition Chantal Béret, in “La querelle des architectes: vieux Modernes, jeunes Anciens, nouveaux ‘Ni-Ni’”, distinguishes four main tendencies: modernists, historicists, partisans of a populist aesthetic, and “spokespersons of a new modernity” (

Béret 1981). Beret situated the emergence of postmodernism between 1972 and 1976, in direct relation to the intensification of interest in social housing. Christian de Portzamparc, in “Le symbolique et l’utilitaire”, declared:

it is the utilitarian itself that took the place of symbolism, ensuring the very function: to become the phantasmic origin, the nature and the culture which can legitimize and make universal the new plastic emotion.

Despite the gradual dissemination of postmodernist discourse within the architectural circles in France, some years later, in 1985, an exhibition entitled

New Directions in Modern Architecture: France/USA (

Nouvelles directions de I’architecture moderne: France/USA), curated by Kenneth Frampton and Michel Kagan at the Institut français d’architecture in Paris, was openly conceived in opposition to the postmodernist approach that was developed at the Venice Biennale of 1980. The ideas developed by Frampton and Kagan in the introduction to the exhibition catalogue, which was entitled “Moderne versus moderne: Affinités transatlantiques” (“Modern versus Modern: Transatlantic Affinities”) (

Frampton and Kagan 1985), could be opposed to the guiding arguments of the exhibition

Nouveaux plaisirs d’architecture (

New pleasures in architecture) (

Dethier and Walter 1985), curated by Jean Dethier at the Centre Pompidou and held between 21 February and 22 April 1985, which was celebrating postmodernism.

8. François Chaslin’s Interpretation of Postmodernism

François Chaslin, in his essay entitled “L’affranchissement des posts”, written for the catalogue of the exhibition

Nouveaux plaisirs d’architecture, distinguishes as the two main figures promoting postmodernism in France Jean Nouvel and Christian de Portzamparc, claiming that

La modernité ou l’esprit du temps had played an important role in promoting postmodernist architecture in France, despite the fact that it was never embraced by French architectural circles. In his effort to describe the specificity of the postmodernist approach in French architectural debates, Chaslin highlights that “[p]ostmodernism has never, in France, constituted a thought but more exactly an atmosphere, a poorly framed feeling, a simultaneous slippage of minds towards who knows what.” (

Chaslin 1985) According to Chaslin, French postmodernist architecture was not based on a “structured theory, [but on] […] certain apostles of traditional urban forms and typo-morphological analysis or, obviously, with the secretaries of neoclassicism, and even this is more a dogma than a theory, of a sacred ideology that of a philosophy is of a deep analysis of reality” (

Chaslin 1985). Chaslin discerns the following main actors in the dissemination of the postmodernist approach in architecture within the French context: certain articles of

L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui, the rubric “Nostalgie” of

AMC (

Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité), an ensemble of Exhibitions, and the foundation of the Archives of Modern Architecture in Brussels by Maurice Culot in 1968. He places particular emphasis on an article by Robert Venturi published in

L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui in 1978, in which the latter highlights that he treats decoration with humour. Chaslin also sustains that “[p]ostmodernism […] suffers from its origins, too inscribed in reverie, the production of paper, discourse and the pasteboard of exhibitions; it has the disadvantage of favouring a certain exhibitionism, an individualism that is sometimes more outrageous than the race for social recognition” (

Chaslin 1985).

Chaslin concluded his text entitled “L’affranchissement des posts” with the remark that “shock images replace the slower movement of ideas” (

Chaslin 1985). Most probably, Chaslin refers to Venturi’s article entitled “A Definition of Architecture as Shelter with Decoration on it, and Another Plea for a Symbolism of the Ordinary in Architecture” and “Une définition de l’architecture comme abri décoré” (

Venturi 1978a,

1978b). In the former, Venturi claims that “[t]he symbolic content of commercial developments certainly differs from that of traditional towns” (

Venturi 1978b). Venturi, in the aforementioned article, paid particular attention to the role of the Las Vegas strip in shaping a new sensibility towards the urban landscape. He underscored that “the popular art of the ‘strip’ is as much advertising as the architectural refinement or the ‘correct and magnificent skilful play of volumes assembled under the light’ which today characterises the social signs of large companies” (

Venturi 1978b). Chaslin also noted that his embracement of the symbolic dimension of architecture does not mean that he rejects functionalism. On the contrary, he underlined that his “definition of Architecture as a shelter endowed with a symbol does not presuppose a refusal but rather an acceptance of the functionalist doctrine which must be developed in order not to forget it” (

Chaslin 1985). He formulated the following two questions regarding architecture’s functionalism: “How can we not admit the impossibility of preserving pure functionalism in architecture and thereby recognise the contradictions which, in any construction, appear between aesthetic and functional necessities? Why not let functions follow their own path so that functional requirements are not distorted by inadmissible decorative purposes?” (

Chaslin 1985).

9. Les Immatériaux: The Impact of New Technologies on Modernity

An important exhibition for understanding the role of post-modernist approaches beyond the discipline of architecture and urbanism in France is the well-known exhibition

Les immatériaux, curated by French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard, who had published the seminal book

La condition postmoderne:

rapport sur le savoir in 1979 (

Lyotard 1979), and Thierry Chaput and held at the Centre Pompidou from 28 March through 15 July 1985—that is to say, the same year as

Nouvelles directions de I’architecture moderne: France/USA, curated by Kenneth Frampton and Michel Kagan, at the Institut Français d’architecture, and

Nouveaux plaisirs d’architecture, curated by Jean Dethier, at the Centre Pompidou. Reading the press release for the exhibition

Les immatériaux, it becomes clear that this exhibition’s purpose was to question the ways in which “new technologies” challenge “a certain number of accepted ideas which characterize modernity”

4. The curators also remark, in the exhibition’s press release, that this reflection regarding the impact of new technologies on how modernity is conceived had not touched the French context until that moment as much as other national contexts. Taking this observation as a starting point, Lyotard and Chaput, through this exhibition, which he understands mostly as a counter-exhibition as far as its status is concerned, aimed to shed light on how new technologies had triggered the emergence of new sensibilities not only in the arts but also in the fields of literature and sciences and in our lifestyles. Despite the fact that the aforementioned exhibition referred to fields much beyond architecture, Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid, and Peter Eisenman contributed to it.

10. The Tension between Modernism and Postmodernism as Symbolic Domination

To understand the complexity and the multiplicity of the debates regarding the tension between modernism and postmodernism within the French architectural circles during the eighties, it would be insightful to adopt certain aspects highlighted by Pierre Bourdieu, in “Le marché des biens symboliques” (“The Market of Symbolic Goods”), where the latter aimed to shed light on the tactics that different people shape in order to enhance their domination in their field of expertise, on the one hand, and acquire as much as possible legitimacy, on the other hand. More specifically, to grasp the polysemy of the various postures that emerged in response to postmodernist approaches in architecture—either these responses were positive or negative towards postmodernism—one should bear in mind that “the theories, methods and concepts which appear […] to be simple contributions to the progress of science are always also ‘political’ manoeuvres aimed at establishing, restoring, strengthening, safeguarding or overthrowing a determined structure of science [and at enhancing] […] symbolic domination” (

Bourdieu 1971, p. 121;

1984;

1985). In other words, to interpret the ways in which postmodernist architecture was re-semanticised through its incorporation in the debates that accompanied the different exhibitions presented here, one should take into account that the agendas of the curators of the exhibitions, the architects that were invited to exhibit their works, and the authors that contributed to the exhibition catalogues were based, to a certain extent, to the their endeavours or “to conquer or defend the […] legitimate exercise of a scientific activity and of the power to award or deny legitimacy to competing activities” (

Bourdieu 1971, p. 121;

1984;

1985).

Pierre Bourdieu’s “Le marché des biens symboliques” is useful for deconstructing the solidity of the various architects’ positions in relation to their ideological, political, aesthetic, marketing, and academic ambitions. To grasp how symbolic domination affects their ambitions, it suffices to bring to mind Bourdieu’s remark that “[s]ymbolic domination… is something you absorb like air, something you don’t feel pressured by; it is everywhere and nowhere, and to escape from that it is very difficult” (Bourdieu cited in

Grenfell 2014, p. 192). In “Le marché des biens symboliques”, Bourdieu highlights that “[t]he field of production and circulation of symbolic goods is defined as the system of objective relations between different instances characterized by the function they fulfill in the division of labor of production, reproduction and distribution of symbolic goods” (

Bourdieu 1971, p. 54). Another remark of Bourdieu, in the aforementioned text, which is pivotal for grasping how the understanding of the controversy between modernism and postmodernism in architecture was conceived by the architects and architecture critics, theorists, and historians under study in this article “are mediated by the structure of the field” and “depend on the position occupied by the category in question within the hierarchy of cultural legitimacy” is the following:

All relations that a determinate category of intellectuals or artists may establish with any and all external social factors—whether economic (e.g., publishers, dealers), political or cultural (consecrating authorities such as academies)—are mediated by the structure of the field. Thus, they depend on the position occupied by the category in question within the hierarchy of cultural legitimacy.

Bourdieu also argues that “[a]ll relations among agents and institutions of diffusion or consecration are mediated by the field’s structure” (

Bourdieu 1984, p. 25), drawing a distinction between subjective and social representation. Another distinction that is at the centre of Bourdieu’s thought is that between the “field of restricted production” and the “field of large-scale cultural production” (

Bourdieu 1984, p. 17). According to Bourdieu, the former is “measured by its power to define its own criteria for the production and evaluation of its products” (

Bourdieu 1984, p. 5). To understand how the interrelation between architecture and its economic, political, and social context evolves, it is useful to take into consideration Bourdieu’s position claiming that “the more cultural producers form a closed field of competition for cultural legitimacy, the more the internal demarcations appear irreducible to any external factors of economic, political or social differentiation” (

Bourdieu 1984, p. 5). A case in which it becomes evident how Pierre Bourdieu’s approach is useful for understanding the diverse interpretations of the tension between modernism and postmodernism is the comparison between

La modernité, un projet inachevé: 40 architectures, curated by Paul Chemetov and Jean-Claude Garcias, and

La modernité ou I’esprit du temps, curated by Jean Nouvel, Patrice Goulet, and François Barré (

Charitonidou 2015). Following Bourdieu, we could claim that the ways in which the curators of the aforementioned exhibitions perceive the image and role of architecture reflect their respective positions within the social field. In this sense, the exhibitions could be understood as mechanisms or tactics aiming to conquer symbolic capital.