Abstract

This article focuses on a performance titled In the Land of the Gilead, performed in 2012 by Doron Tavori and Yochai Avrahami at the Centre for Digital Art in Israel. The work was performed as a part of the exhibition Le’an (Where To?). Its title is derived from a plan suggested by Laurence Oliphant (a British colonialist bureaucrat, author, and Member of Parliament) in 1881 to settle Jews in the Gilead region east of the Jordan River. The article examines the ways in which Tavori and Avrahami re-enact Oliphant’s plan, which was never realised, as well as numerous other historical moments of Oliphant’s colonialist endeavours and those of his contemporaries, tying them to the present-day situation in the Middle East and elsewhere. The article also examines the wider contexts and curatorial strategies of the exhibition Le’an, which focused on alternative Zionist histories that challenged Zionism’s exclusive focus on the land of Israel. The article suggests that by juxtaposing nuanced and complex re-enactments of numerous and conflicting histories, the work prompts audiences to reconsider their political and national understanding of such colonial and Zionist histories, allowing these complex pasts (which are often celebrated or silenced) to be articulated as integral to contemporary national narratives.

1. Introduction

In the last 20 years or so, re-enactment has become a widely present practice in contemporary art: 2001 saw Jeremy Deller’s Battle of Orgreave in which a major battle between the miners and Thatcherite police was re-enacted (Correia 2006); in 2010 a re-enactment of Marina Abramović’s works in the MoMa exhibition The Artist is Present ignited a debate about re-enactment and the future of performance (Jones 2011); and in 2011 Rebecca Schneider published a book titled Performance Remains: Art and War in Theatrical Re-Enactment which was one of the first academic works to explore the subject in depth (Schneider 2011). This paper contributes to this discourse by examining the practices of re-enactment within the specific contexts of the field of Israeli art and the Middle East region’s histories. Focusing on a performance titled In the Land of the Gilead, performed by the artist Yochai Avrahami and the actor Doron Tavori, as a part of an exhibition titled Le’an (Where To?) held at the Centre for Digital Art in Holon in 2012 (Danon et al. 2011), this paper examines the ways in which contemporary re-enactments allow us to rethink the region’s conflicted histories and imagine its pasts, presents, and futures otherwise.

In the Land of the Gilead takes its title from one of Laurence Oliphant’s books titled The Land of the Gilead: With Excursions in the Lebanon (Oliphant 1881). Oliphant—a British colonialist bureaucrat at the service of Her Majesty, a member of the British Parliament, a newspaper reporter, a published author, and an avid Christian Zionist— details in the book his plans to settle Jews in the Gilead region, a part of modern-day Jordan, which was a peripheral region of the Ottoman empire at the time (Taylor 1982). Oliphant advocated for his plans, which were hatched in 1879 after the Berlin agreement, to Jewish and British Zionist figures, as well as to Ottoman officials and pre-eminent colonial figures for a number of years. His plans raised interest amongst British, Jewish, and European notables and Nahum Sokolov even translated the book into Hebrew in 1885 (Sokolov 1885), but it had little success with the Ottoman rulers who were wary of the growing British influence in the region (Ilan 1983). The plan was finally aborted in 1882, and although Oliphant’s book circulated widely at the time and was well received, it was also quickly forgotten and garnered little academic or political interest since the late 19th century. Within the art world, there has been no mention of it, as far as I am aware.

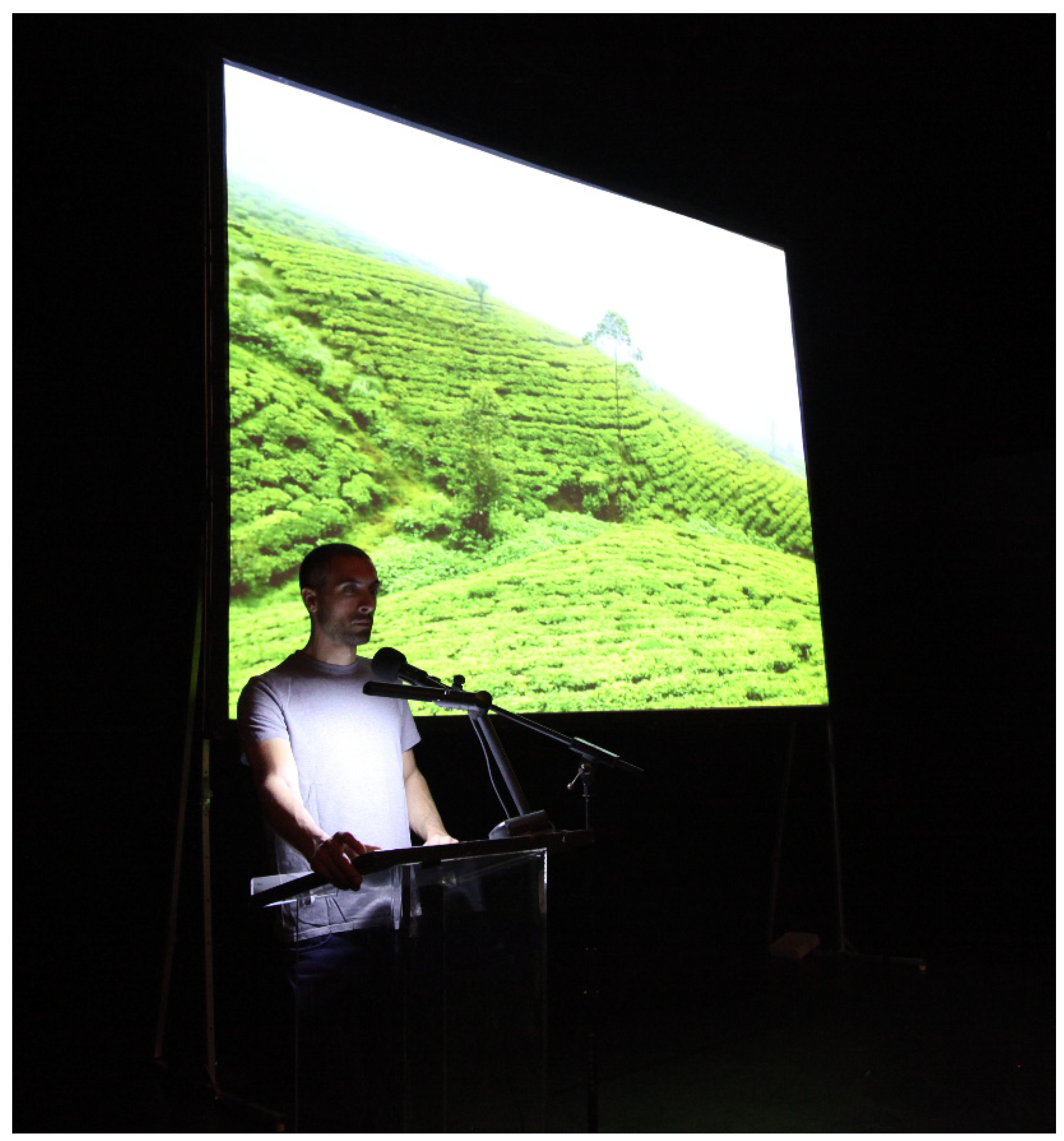

The artwork titled In the Land of the Gilead, initially researched and written by Tavori, was divided into 24 sections (based on the format of the Homeric Iliad) and provides a “grand journey” through Oliphant’s life, as well as an exploration of colonialism and its impact on contemporary geo-politics in the Middle East and elsewhere (Tavori 2012). The sections are divided into two types of presentations presented alternately: The first type was presented live by Tavori (and sometimes by other actors) who performed as Oliphant, and read one of his texts (for example, his description of the Saugeen first nations with whom Oliphant signed a territorial agreement when he was Superintendent of Indian Affairs). See Figure 1. The second type of performance consisted of a more contemporary text or another historical text written by another author, in both cases relating to the same events. Thus, after we hear of Oliphant’s sojourn with the Saugeen in Canada, we see another performance, pre-recorded rather than live, in which an actor reads from the lawsuit presented by the Chippewa and Saugeen first nations in 1994, claiming 80 billion dollars as compensation for breaking Oliphant’s promise to protect parts of their territory in return for handing over other areas to the white settlers—a promise that was perhaps never given in earnest. The work begins with colonised Sri Lanka where Oliphant lived as a child—a son of a high-ranking colonialist official (his house has now turned into a boutique hotel)—and ends with Oliphant’s last home in Daliat el Carmel, which has been turned into a memorial house for the Druze fallen soldiers. In between, Oliphant—like a Victorian Forrest Gump—appears in Kathmandu, the British-Chinese Opium wars, the Polish uprising, Chechnya, Canada, the English immigration to the U.S., and of course the Middle East and Ottoman Palestine.

Figure 1.

In the Land of the Gilead (actor Nimrod Bergman). Still from performance, 2012.

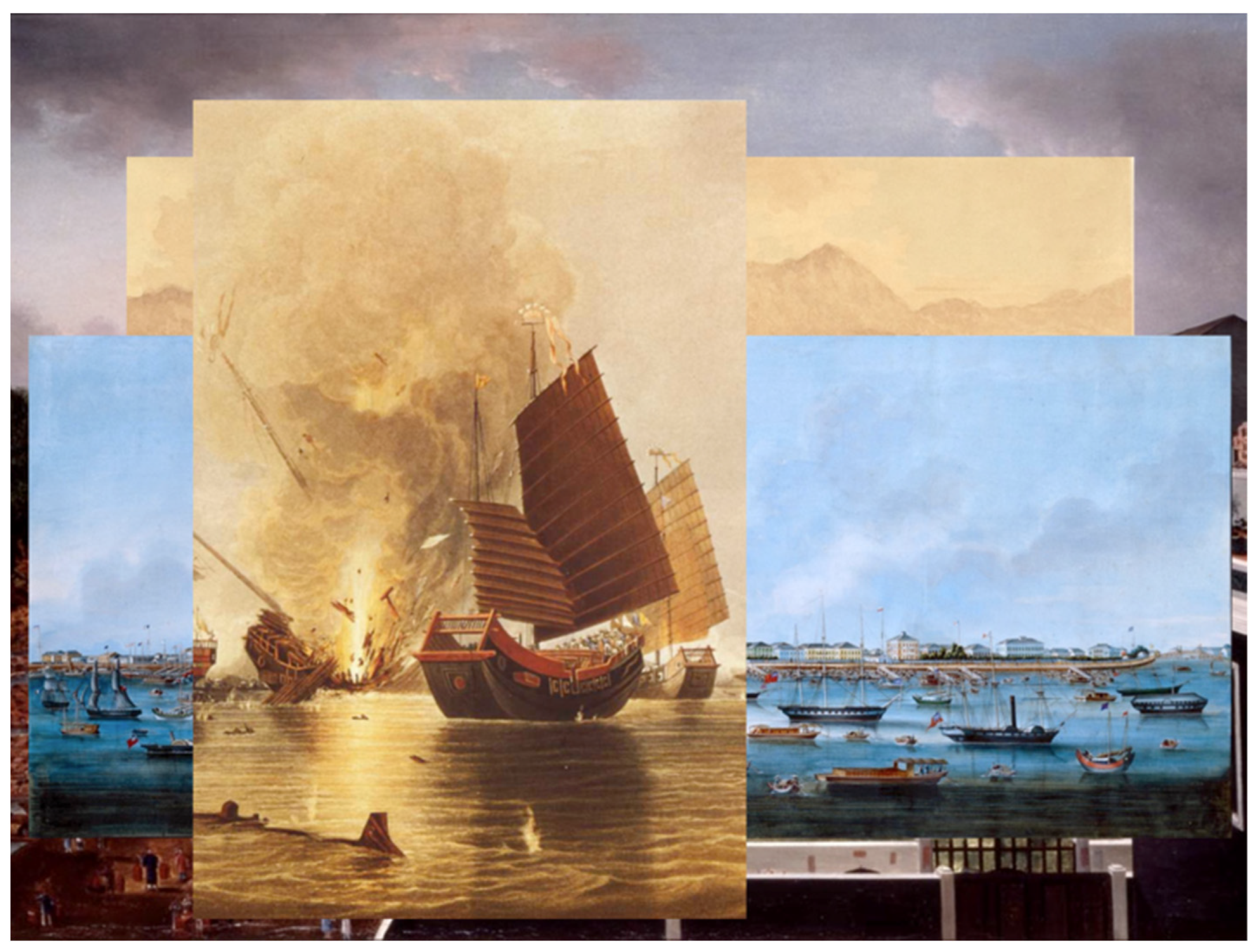

All performances, whether live or pre-recorded, are accompanied by elaborate slideshows of “found images” devised by Avrahami. See Figure 2. Some of the images seem directly related to the texts, such as maps with arrows showing the regions discussed, others are more associative and collage-like, and others still provide a contemporary, critical, and sarcastic commentary on the events depicted.

Figure 2.

In the Land of the Gilead. Still from slideshow, 2012.

As is often the case with artworks based on re-enactments and the performance of history, In the Land of the Gilead, returned to carefully chosen moments and events whose impact, although not always appreciated in real time, is still keenly felt today. Jeremy Deller found “his” moment in the conflict between the miners and the Thatcherite government that still haunts contemporary England and seems ever more relevant after Brexit (Ten Brink 2012). In her book, Rebecca Schneider discusses the artistic responses to re-enactments of the American civil war—a war whose outcomes still, perhaps more than ever before, resonate with American society today (Schneider 2011). Unlike Deller and Schneider, Tavori and Avrahami’s work re-enacts something which was never “enacted” in the first place—a spectre of a failed plan, long forgotten in Zionist History, bringing its practice closer to works such as those of Yael Bartana’s And Europe will be stunned that depict imagined histories. However, In the Land of the Gilead, unlike Bartana’s work, does not perform a history imagined by the artist, but rather a historical plan, which despite sounding quite fantastical today, was well aligned with other colonialist endeavours of the time which came to fruition and could have been realised in different historical circumstances.

2. Imaging Zionism’s Histories and Curatorial Strategies

The questions of “pregnant” historical moments and the exploration of a historical imaginary, featured prominently not only in In the Land of the Gilead, but also in other projects included in the Le’an exhibition. The group exhibition was curated by Eyal Danon, Ran Kasmy Ilan, and Udi Edelman, and included 19 different artists and researchers such as Efi & Amir, Ariella Azoulay, Ronen Eidelman, Louis Kaplan, and Yael Bartana, all of whom staged various artworks and research based projects which addressed forgotten and imaginary Zionist histories, providing alternatives to current Zionism’s almost exclusive focus on a the land of Israel. Melissa Shiff, Louis Kaplan, and John Craig Freeman, for example, explored Mordechai Manuel Noah’s failed plan to build a refuge for Jews in Grand Island New York in 1825. Re-enacting his plans in virtual reality, Michael Blum traced the plans of Joseph Otmar Hefter who in the 1930’s developed the idea of a Jewish state in Alaska, Australia, or South America; while Malkit Shoshan and Nirit Peled developed a dispersed and globalised vision of contemporary Israel, featuring an interactive map of Israeli presence and interests the world over.

The Le’an exhibition held in 2012 was the second iteration of an ongoing project that had begun in the previous year and was displayed at the Centre for Digital Art in Holon as an in-process work consisting of archival materials and a visual network of concepts developed by some of the artists and curators. While Tavori had collected, sifted, and edited the work’s texts before the Le’an project began, many of the images were collected and reworked by Avrahami during the project’s first stage. In 2014, two years after the Le’an exhibition, Udi Edelman expanded some of the exhibition’s main issues in another project he curated. Titled Histories, the project explored the ways in which artists worked with historical and archival materials, this time widening the scope beyond Zionism and the question of a Jewish territory (Edelman 2013). Avrahami, but not Tavori, also participated in Histories and developed his ideas regarding museological displays of history, conflict, and nationalism in a series of large-scale photographs simply titled Display.

Both Histories and Le’an explored some of the major issues and practices that have come to be identified with the Centre for Digital Art. Their emphasis on documentary, research, and performative aspects, their focus on crucial political questions, and their interest in issues of nationalism and conflict in Israel/Palestine and beyond have been some of the main axes of the Centre since its foundation in 2001 by the curator Galit Eilat. Many of the Centre’s exhibitions held throughout its first decade delved into such large political questions: Chosen, for example, held in 2008, explored the messianic dimensions in nationalist narratives of Israel and Poland (Eilat and Szylak 2008); while According to Foreign Sources, which was held three years later, focused on censorship and other restrictions of information based on vague “security interests” (Melzer 2011). In both these exhibitions and others, the curatorial strategies were based in the attempt to uncover and deconstruct hidden ideologies. In According to Foreign Sources, Gilad Meltzer, the exhibition’s curator, defined the project’s mission as “to explore what it means to observe, listen, and represent, what we have been trained to accept as prohibited to gaze, knowledge or presentation” (p. 262), while in The Chosen curators Galit Eilat and Aneta Szylak presented works which explored “the way in which current national and communal narratives are still affected by philosophical, literary and ideological messianism”.

Other exhibitions, such as the Liminal Spaces project initiated by Eilat between 2006 and 2009, also explored national narratives and conflicts, but focused less on uncovering hidden ideologies and more on exploring new ways of subverting existing political hegemonies while working in liminal positions (Eilat and Danon 2009). The project, which provided a shared platform for Israeli, Palestinian, and International artists who worked together in response to the West Bank barrier wall being built by Israel at the time, indeed challenged existing political concepts and hegemonic constructs, as providing a shared space for Palestinians and Israelis to work together was seen as problematic by both sides.

The curatorial strategies adopted by many of the exhibitions in the Centre for Digital Art, i.e., deconstructing hidden ideologies upholding hegemony and working from liminal sites to actively subvert such ideologies, fall squarely within the remit of critical contemporary art of the last decades. Such practices, largely based in post-structuralist critique which developed from the late 1970s onwards and became prominent in Israel’s art field and political discourse in the mid 1990s, favoured the deconstruction of existing hegemonies and the exposition of hidden power relations, often using liminal spaces, such as borders and barriers, as sites from which to challenge existing political constructs.

Contrary to many of the centre’s previous exhibitions, Le’an focused on a highly hegemonic political framework, that of Zionism. The main aim of the exhibition, as the curators state in their opening statement and as the works themselves demonstrate, was to challenge the exclusive focus of current Zionism on the land of Israel, a challenge prompted by the Iranian nuclear threat to Israel that dominated the political discourse of the time. “A nuclear Iran”, the curators Danon, Kasmy Ilan, and Edelman write, “appears to pull the rug from under Zionism’s main argument, regarding the formation of a singular haven for world Jews, a promise that an Israel existing under nuclear threat could no longer live up to” (Danon et al. 2011). If such historical promises have now been shaken, they continue; it is time to return to Zionism’s own histories in order to re-examine some of the now forgotten alternatives to its focus on the land of Israel. Danon, Kasmy Ilan, and Edelman describe this historical return as the key element of their curatorial work in the exhibition:

The point of departure for the project and the current exhibition is the similarity between questions regarding Jewish existence that emerge in the contemporary context and those which emerged in the context of the second half of the 19th century. In both periods, we detect a sense of anxiety. In the past, this sense arose out of the failure of Jewish emancipation, the Pogroms, and social rejection, all of which led to mass migration, alongside an incredible ferment of creative ideas and experimental creative answers to “the Jewish question”1.(Danon et al. 2011)

It is interesting to note the ways in which the curators describe the historical moments they return to not only as anxious but also as “creative” and “experimental”. Such creative roles which were previously taken up by Zionist and other public figures and visionaries are now, it seems, embodied by the curators themselves as well as the artists and researchers participating in the exhibition—shifting the onus of re-imaging the national pasts, presents, and futures from the political sphere to the realm of the aesthetic.

While Le’an’s exploration of alternatives to the exclusive focus of Zionism on the land of Israel is thought provoking and provides a critical framework in which to rethink some of the contemporary Zionist axioms, the exhibition, by and large, did not challenge the very idea of Zionism as an historical and territorial answer to the “Jewish question”, nor did it challenge the very idea of territory as a crucial component for a Jewish polity. Although many of the projects included in the exhibition did not present a vision of a fully articulated Jewish state, many of them did re-enact or imagine a particular territorial site or sites in which the Jews would live as an organised and defined community.

Re-examining only certain aspects of a construct as complex as Zionism and exploring its differing histories is certainly a viable curatorial strategy, but it is a highly unusual one. Le’an did not seek to deconstruct Zionism and re-train our gaze and our knowledge (as the curator Gilad Meltzer suggested in According to Foreign Sources), nor did it work to subvert existing ideologies from liminal sites as Galit Eilat did. Its approach to Zionism is also unusual within the larger scope of the critical theory and practice in the Israeli art field. Going back to the essay that inaugurated the critical and post-structural “turn” of contemporary art in the Israeli art field—Sarah Chinski’s The Silence of the Fish published in 1993, it is exactly the issues of land and territory and their inherently Zionist embodiment by the Israeli avantgarde that are the main target of Chinski’s sharp critique (Chinski 1993). Working to undermine the avantgarde’s conceptualisation as non-nationalist or even anti-nationalist, Chinski convincingly demonstrated how works of art deemed highly critical actually serve to naturalise the territorial aims of Zionism and its emphasis on the land of Israel. In this essay and others, Chinski articulates her aim to expose and sever the ties between Zionist nationalism and the land of Israel, and it is this move that came to define some of the goals and practices of critical art in the Israeli field in the following decades.

Chinski was not alone in her attempt to undermine the Gordian knot between Zionism and the land of Israel. Numerous historians, geographers, and sociologists began to re-examine these basic premises of Zionism during the 1990′s in a discourse which was often referred to (more or less accurately) as post-Zionism. Laurence Silberstein, a Jewish Studies scholar and one of the key writers within this discourse, described post-Zionism in 2002 as a set of positions which sought to reveal that “the foundations upon which the prevailing Zionist definitions of Israeli national identity, national territory, national history, and national law rest are contingent rather than natural, necessary or essential” (Silberstein 2002). It also sought to demonstrate “that things can be otherwise, that alternative ways of understanding Israel identity, territory, history and law are available”. Three years later, in 2005, Uri Ram, one of the key sociologists associated with post-Zionism, reviewed the discourse in more detail, identifying four distinct theoretical frameworks included within it (Ram 2005). One of these frameworks, which Ram dubs as postmodernist, and which I have referred to as post-structuralist, is highly pertinent to the discourse of contemporary critical art. Reflecting on the postmodernist approaches to Zionism, Ram suggests such approaches see nationalism at large, and Zionism in particular, not as a “the conventional expression of peoplehood’’ but rather as a “framework forced upon fluctuating identities”. Within such an understanding, adds Ram, nationalism is seen inherently as “a form of oppression” while “post-nationalism [as] a form of liberation”. Such approaches, which veered from the descriptive to the normative, saw national narratives, as well as national territories, not only as a formation whose premises could and should be rethought but as constraints to be liberated from. The role of the critical scholar within such an understanding, as evident in Chinski’s work almost a decade earlier, is not to examine existing national narratives, but rather aid in the liberation from them.

The curatorial practices of Le’an seem to fall squarely within the remit of Silberstein’s description, offering alternative ways to understand the question of territory within Zionism by returning to its forgotten histories. Unlike the position adopted in the post-structuralist critique of nationalism though, Le’an does not prescribe a normative reading of Zionism as inherently oppressive and suggests a liberation from it. Rather, it maintains a critical approach based in curiosity, positioning itself as a part of creative and experimental histories developed since the mid-19th century, and offering a platform in which to explore their relevance for today’s Zionism. In doing so, it has become a part of a marked shift towards a more nuanced understanding of Zionism which developed in the second decade of the 21st century. Such approaches developed by historians such as Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin, Hillel Cohen, and Menachem Klein have become paramount in contemporary discussions around Zionism, but has had very little impact on the field of contemporary art.

3. Re-Enacting Histories and Futures, or What Can We Learn from “The Land of the Gilead”

Having analysed the curatorial strategies of Le’an, it is now time to return to Avrahami and Tavori’s Land of the Gilead’ and its particular practices. How does the re-enactment of Laurence Oliphant’s colonial endeavours and his plans to settle Jews in the Gilead work with Le’an’s curatorial strategies? How does it challenge or expand them? One possible answer to these questions could come from seeing In the Land of the Gilead as simply offering another 19th century answer to the “Jewish Question”. Indeed, if we focus our attention on the two sections of the performance in which Laurence Oliphant’s proposal for a Jewish a settlement in the Gilead and Nahum Sokolov’s translation of it are re-enacted, then the work becomes yet another territorial “solution” for the Jews. Such a reading of the work would locate it comfortably within the aims of the exhibition and underline its inherent relevance to Zionism’s histories. It would also highlight the links between Oliphant’s scheme in the Gilead and other such schemes proposed by the British Empire, the most well known of which is the “Uganda Scheme” proposed in 1903 by Joseph Chamberlain, the British colonial secretary. Chamberlain’s offer focused on an area in western Kenya in which the British empire would allow Jews to settle and to have varying degrees of autonomy (the details of the plan were never finalised). The area proposed was deemed to be “free” of local inhabitants and would have provided a safe haven for Eastern European Jews after the Kishinev Pogroms. The plan was seriously debated within Jewish and Zionists factions over two years until 1905, when the sixth Zionist congress considered and ultimately rejected it by a tiny majority.2 Returning to Chamberlain’s proposal, its colonialist motivations for employing the Jews as a shield against German expansionism in East Africa, and his views of the Jews as inherently European, potentially prosperous and subservient to the British Empire, resemble many aspects of Oliphant’s scheme hatched 25 years earlier. Although the Uganda plan was ultimately rejected by the Zionist Congress and withdrawn by the British, it remained enshrined in Zionism’s history, marking an alternative history never tested and providing an immediate context in which to reconsider Oliphant’s plan and its re-enactment.

Land of the Gilead indeed originated with Tavori’s interest in Oliphant’s specific endeavours in Palestine and his scheme for the settlement of the Jews in the Gilead, but in the finished work the performance of these particular histories make up only a fraction of the entire project. Any serious consideration of the work must thus take into account its other sections that address issues and histories the world over, from Sri Lanka to the Black Sea. If the emphasis on Jewish histories is to be maintained, in light of the exhibition’s aims, a potential reading of the work in its entirety could see the various colonial histories included in it, as building up to Oliphant’s plan in the Gilead and exposing their colonial contexts. Such an interpretation would see Oliphant’s various schemes included in the work, as demonstrating a similar colonial “logic” of usurpation, displacement, and implementation of the British Empire’s interests all around the world, with Palestine serving as just one further example. Within such a framework, the role of In the Land of the Gilead would be a critical one, exposing the genealogy of colonialism and performing Oliphant’s scheme to divide and conquer the region of the Gilead as foretelling of the fateful division of the Middle East into separate territories by the colonialist powers of France and Britain—a division which has resulted in the ongoing conflict in the region. The warm embrace of Oliphant’s colonial schemes by Nahum Sokolov and other Jewish and British Zionists, could also be seen as attesting to a “streak” of colonialism buried within Zionism, highlighting its contribution to this unresolved conflict. Such a reading could be supported by the Land of the Gilead’s last section, in which a text written by Amal Nasser el-Din (a Druze author and former member in the Israeli Parliament) describes the contemporary incarnation of Oliphant’s last home in the Druze town of Daliat el Carmel. The home, now dedicated to the memory of the Druze soldiers who lost their lives while serving in the Israeli Defence Forces, as well as Nasser el-Din’s text, could be seen as attesting to the outcome of the colonialist logic re-enacted throughout the work: a bloody conflict involving various communities, nations, and political alliances for which there is no end in sight.

Reading In the Land of the Gilead as an exposition of colonialism’s brutal wrongdoings provides a framework to understand the numerous histories and global sites included in the work and to reconsider their relevance for today’s conflicts in the Middle East. However, such an interpretation based in a singular colonial “logic” misses a lot of the nuanced and complex depiction of colonialism in the Land of the Gilead. For rather than an exposition of colonialism’s hidden genealogy of usurpation and wrongdoings, or rather alongside such a genealogy, Tavori and Avrahami’s work provides a plethora of positions and events highlighting colonialism’s differing and often contradicting actions and histories.

In Section 6 of The Land of the Gilead for example, just before the performance of Oliphant’s broken promise to the Saugeen first nation in Canada, there is a text taken from a guide written in 1855 by the Irish educationist and philanthropist Vere Henry Louis Foster, in which he provides advice for lower class immigrants (house servants, labourers, and the like) wishing to cross the Atlantic to the U.S. and Canada. In the text, the hardships of the immigrants are outlined, and Vere Foster suggests ways in which they may equip themselves for the trip. Thus, the text describes the immigrants, those who were the actual colonisers, as the socially and economically disenfranchised people they were—people crossing the ocean in search of a better future with little knowledge of what awaits them. Seeing the performance of this text, especially when it was re-enacted right before Oliphant’s broken promise to protect the first nations lands and the Saugeen legal claim for compensation, paints a highly complex picture of colonialism, one which does not absolve its immorality, but which places it within a wider political and socio-economic context, allowing us to think and rethink our position.

Another text included in the subsection of the work titled “Ceylon, Nepal and India”, includes a damning critique of British colonialism in Sri Lanka (where Oliphant’s father served as a high-ranking colonialist Judge) and accuses the local colonial regime not only of financial misconduct, but also of a grieve subversion of justice which caused the wrongful execution of a local priest. The text was written by none other than William Molesworth the 8th—a long-standing member of the British Parliament who even served briefly as the British colonial secretary in 1855. Molesworth, a Baron who also held the title of Sir and served as a local sheriff at one point, was clearly a part of the British upper class and colonialist regime, yet he advocated for a self-government of the British colonies and did not hesitate to critique the immoral aspects of colonialism. Reading his text just before Oliphant’s own texts on Ceylon and Kathmandu, as well as the London Times reporter’s mocking description of the Nepalese ruling dynasty and another of Vere Henri Louis Foster’s texts which derides the religions of East Asia and calls for renewed missionary efforts to convert the heathens to Christianity, one is forced again and again to reconsider their stance towards colonialism and its numerous voices.

Oliphant’s own position as a colonialist is also more complex than initially assumed. His account of the Gilead, for example, however steeped in an abhorrent colonial “logic” which sees people and communities as objects rather than subjects—easily removed or subjected to various powers—also provides utopian visions of regional cooperation. These visions are not unlike those of Herzl’s own utopia developed 21 years later in Altneuland (Herzl 1902) or that of Boris Schatz (the founder of the Bezalel School) whose own utopia for Jerusalem was published in 1923 (Schatz 1923). The detailed description of the Gilead’s train system was particularly striking as it attested not only to Oliphant’s vivid imagination, but also to his accumulated knowledge in the British colonies, reading less like a utopian dream and more like a plan to be implemented. He writes:

The true outlet for it’s [the Gilead region] produce would be the port of Haifa, situated under Mount Carmel. From here a railway might be constructed to Tiberias, with a branch to Damascus, as I already proposed, while the line to the colony would then follow the valley of the Jordan to the northern shore of the Dead Sea. …It would then pass for twenty-five miles through the lands of the colony and the plain of the Seisaban to the north-east angle of the Dead Sea. …It might also be deemed desirable, in the event of the Jaffa and Jerusalem railroad not being made by the French company, who obtained a concession for the purpose, to have a short branch or tramway by way of Jericho to Jerusalem, this would put the colony in close and direct communication with Jerusalem, and bring the latter city to within five or six hours distance of the port of Haifa by rail.(Tavori 2012)

The moral positions and counter positions embodied by Tavori and Avrahami’s re-enactment, and the dynamic rethinking they demand from their audience are clearly conceptualised by Elizabeth Edwards, a British researcher whose own work focuses on the crossroads of photography, documentation, museums, and colonialism. Reflecting on the displays of colonialism in British museums, Edwards and Mead suggest that unlike other challenging histories such as those of the Holocaust or the slave trade “the colonial past resists being reduced to a tidy narrative or a single meaning; rather, it unfolds as an incomplete set of fluid relationships, as any number of unpredictable trajectories, over time and space” (Edwards and Mead 2013). The narrative of the colonial past, Edwards and Mead continue, “lacks discursive unity, apparent closure and moral certainty, and the rawness of its legacy is still under negotiation”. This past, they add, includes highly varied events such as “the experience of an unruly Indian peasant attacking a police station, a district officer in 1930s Kenya, an Australian Aboriginal child taken from her or his parents, or an officer of the East India Company in the 1860s” which not only differ from each other, but also provide hugely different experiences depending on the position of the viewer and participants within the existing power relations. Such an “untidy” past, conclude Edwards and Mead, makes displaying historical texts and photographs within museum exhibitions hugely difficult, often culminating with either a “ludic multiculturalism” or a deep silence regarding the past.

In their exploration of British museums, Edwards and Mead describe one exhibition, in the now closed British Empire and Commonwealth Museum (BECM) in Bristol, in which the attempt “to articulate the colonial past as integral to the national narrative” had been much more successful. In this museum, the various historical and contemporary texts and photographs of colonialism were juxtaposed against each other in a way that made each instance tell a larger and more complex colonialism as a whole. Thus, a photograph displaying officials opening the railway in Nigeria was displayed next to a less official image of local rail workers in Sierra Leone. These images together and other such pairings tell a tale of forced labour and inequality, of modernisation and of varied political allies working within but also across racial divides. They thus offer audiences multiple and competing historical narratives which as Edwards and Mead suggest “make no claim to finality”.

In many ways, In the Land of the Gilead re-enacts the colonial pasts in manners very similar to those described by Edwards and Mead in their analysis of the BECM. It juxtaposes colonial images and texts collected from Oliphant’s empirical endeavours and portrays an image far wider than that of his life or his specific plans to settle Jews in the Gilead. It portrays colonialism as abhorrent and suggests its links to the current conflicts in the Middle East, but it also demonstrates the complexity of colonialism, portraying the actual colonisers as poor immigrants searching for a better future, highlighting the critical positions of some colonisers, and underlining the utopian vision of regional cooperation included in Oliphant’s own colonial scheme. The Zionist histories included and alluded to in the work were also performed in a complex manner. Avrahami and Tavori juxtapose the search for a territory in which Jews could have some form of autonomy with the colonialist “logic” in which such a potential is steeped; they position Oliphant’s suggestion as one of the solutions for the “Jewish Question”, but allude to the Uganda scheme in which a similar plan was rejected by the Zionist congress; and they link Zionist histories but also those of the larger colonial powers to the current conflict in the Middle East.

In the Land of the Gilead complements the critical position of the Le’an exhibition in many ways. It centres on hegemonic histories, both of colonialism and Zionism, and offers a genealogy of their faults, providing a sharp critique of them based in post-colonialism and postzionism. Like the curatorial strategies of the exhibition, the work does not focus on a liberation from colonialism or Zionism, but offers a rather complex, nuanced, and above all, curious examination of them, allowing the audience to take up numerous and shifting positions in regard to their differing histories. By re-enacting not one pregnant moment, but a series of such moments, and by elaborating their relevance for the present and futures, In the Land of the Gilead provides a way in which the past, as Edwards and Mead hope, may be articulated as integral to contemporary national narratives.

Funding

This research receives no funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The “Jewish question” is a phrase that originated in the early 19th and was used by both Jews as well as anti-Semites. It pertains to the discourse regarding the cultural and political status of Jews within Europe, and to the possibility for a territorial and national “solution” for the Jews. See for example the discussion of the “Jewish question” in Holy Case’s book The Age of questions which addresses various national and social questions of the time (Case 2018). |

| 2 | The Uganda scheme and other territorial “solutions” for the Jewish people outside the land of Israel have been discussed by various scholars. See for example Gur Alroey’s discussion of the tension between Zionism and other Jewish territorial groups (Alroey 2016) and Adam Rovner’s discussion of promised lands before (Rovner 2014). |

References

- Alroey, Gur. 2016. The Jewish Territorial Organization and Its Conflict with the Zionist Organization. Detroit: Wayne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Case, Holly. 2018. The Age of Questions. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chinski, Sara. 1993. Silence of the Fish: The Local versus the Universal in the Israeli Discourse on Art (Hebrew). Theory and Criticism 4: 105–22. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, Alice. 2006. Interpreting Jeremy Deller’s The Battle of Orgreave. Visual Culture in Britain 7: 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Danon, Eyal, Ran Kasmy Ilan, and Udi Edelman. 2011. Where to? Available online: https://www.digitalartlab.org.il/skn/en/c6/e3584/Exhibition/Where_To_?nsid=2# (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Edelman, Udi. 2013. Histories. Available online: https://www.digitalartlab.org.il/skn/en/c6/e3204/Exhibition/Histories?nsid=2#cq=FEa8%D7%94%D7%A1%D7%98%D7%95%D7%A8%D7%99%D7%95%D7%AAQ (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Edwards, Elizabeth, and Matt Mead. 2013. Absent Histories and Absent Images: Photographs, Museums and the Colonial Past. Museums and Society 11: 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Eilat, Galit, and Eyal Danon. 2009. Liminal Spaces. Tel Aviv: The Center for Digital Art, PACA: Palestinian Association for Contemporary Art and International Art Academy Palestine. [Google Scholar]

- Eilat, Galit, and Aneta Szylak. 2008. The Chosen. Available online: https://www.digitalartlab.org.il/skn/en/c6/e3878/Exhibition/Chosen?nsid=2# (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Herzl, Ze’ev Theodor. 1902. Altneuland (German). Leipzig: Herman Seeman Nachfolger. [Google Scholar]

- Ilan, Zvi. 1983. Laurence Oliphant and “The Land of the Gilead” (Hebrew). Ḳatedrah be-toldot Erets-Yiśraʼel ṿe-yishuvah 27: 141–62. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Amelia. 2011. “The Artist in Present”: Artistic RE-enactments and the Impossibility of Presence. Drama Review 55: 16–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzer, Gilad. 2011. According to Foreign Sources. Available online: https://www.digitalartlab.org.il/skn/en/c6/e4288/Exhibition/According_to_Foreign_Sources?nsid=2# (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Oliphant, Laurence. 1881. The Land of the Gilead with Excursions in Lebanon. New York: D. Appleton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, Uri. 2005. Four Perspectives on Civil Society and Post-Zionism in Israel. Israel-Palestine Journal of Politics, Economics and Culture 12. Available online: https://pij.org/articles/328/four-perspectives-on-civil-society-and-postzionism-in-israel (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Rovner, Adam. 2014. In the shadow of Zion: Promised lands before Israel. New York and London: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schatz, Boris. 1923. The Built Jerusalem: A Daydream (Yiddish). Jerusalem: Bezalel. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Rebecca. 2011. Performance Remains: Art and War in Theatrical Re-Enactment. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein, Laurence. 2002. Postzionism: A critique of Zionist Discourse (Part 2). Israel-Palestine Journal of Politics, Economics and Culture 9. Available online: https://www.pij.org/articles/135/postzionism-a-critique-of-zionist-discourse-part-2 (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Sokolov, Nahum. 1885. Eretz Hemda (Hebrew). Warsaw: Itzhak Geldman Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Tavori, Doron. 2012. In the Land of the Gilead. Personal communication, Tel Aviv 2023. Available online: https://www.digitalartlab.org.il/skn/en/c6/e3631/Art_Works/In_the_Land_of_Gilead (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Taylor, Anne. 1982. Laurence Oliphant 1829–1888. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ten Brink, Joram. 2012. Interpreting Jeremy Deller’s “The Battle of Orgreave”. In Killer Images: Documentary Film, memory and the Performance of Violence. Edited by Ten Brink Joram and Oppenheimer Joshua. London: Wallflower Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).