Victor Moscoso’s (b. 1936) psychedelic posters have captivated collectors, musicians, and historians alike for decades. Like many of the poster designers working in San Francisco’s hazy heyday of the late 1960s, Moscoso’s cavalier approach to design protocols and printing techniques resulted in an avant-garde mode of site-specific image making. In particular, Moscoso’s freeform innovation brought forth a new type of print that blurred the line between static image and moving picture—now coined as his “moving posters”, or his kinetic lithographs. These posters, though few in number, present a broader question for curators who must contend with the quandary of installing a shapeshifting medium that refutes standards for works on paper and media art alike.

It is important to note that these posters do not actually have moving parts in the literal sense, like flaps or spinning dials. Instead, they

appear to move—a significant distinction given the history of print’s expansive lineage of interactive printed materials dating as early as the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

1 However, unlike volvelles or other human-mediated moving elements, Moscoso’s prints can only be animated by their environment—an optical illusion initiated by external factors rather than the human brain. Moscoso developed his kinetic lithographs to engage with the immersive space of the psychedelic dance hall, which offered colorful light projections, olfactory surprises of sweet, spice-scented air, pulsing subwoofers, and a specific kind of fogginess that diffused everything into a dreamscape. When immersed in the fluid light shows of the dance halls, the lithograph’s central subject would move in a synchronized fashion, taking cues from each changing hue. So particular in their original context, Moscoso’s kinetic lithographs come with an implied set of stipulations for museums to fully activate their potential. But how does one replicate this kind of all-consuming sensory environment in a museum setting? Or, rather, is it even necessary?

Drawing from a larger study of San Francisco’s postwar psychedelic visual and material culture, this essay analyzes two recent exhibitions that include Victor Moscoso’s kinetic lithographs to consider what affordances and limitations these genre-bending artworks offer when placed in a museum setting.

2 This essay examines exhibitions at the de Young Museum in San Francisco and the Fundación Luis Seoane in A Coruña, Spain, in 2017 and 2021, respectively, to reflect on a museum’s obligation to careful contemplation. As an object that directly dismisses the tenets of a standard museum installation designed for gazing in extended duration, such as stable white light and a frame to distinguish an artwork as an object of focus, Moscoso’s kinetic lithographs are a well-suited case study to explore the ever-changing demands of immersive artwork.

1. Tangible Dreamscapes

Amidst the stroboscopic hues of San Francisco’s emerging music scene in the 1960s, San Francisco became a hot spot for eclecticism and progressive thinking, owing much of this widespread popularity to the Human Be-In and Monterey Pop Festival in 1967. Frequent live music performances at local venues drew an enormous crowd of young people to the Bay Area, which reached its height in the summer of 1967—the Summer of Love. And though psychedelic rock was the San Francisco Sound’s most prominent genre, blues, folk, and jazz musicians shared the spotlight to create unexpected mash-ups at local establishments like the Fillmore Auditorium, the Avalon Ballroom, and the Matrix. In the late 1960s, many of San Francisco’s existing performance venues shifted into dance halls to accommodate this trending sensation and paved the way for a new visual and material culture to emerge. Club promoters and music producers needed to fill their auditoriums and looked to local artists to get the job done.

Psychedelic poster artists eagerly accepted the task at hand and began exploring the printed surface through photo-offset lithography, a primarily commercial method that rose to popularity in the late nineteenth century. This process began with a mechanical, or “paste up”, which consisted of a preliminary drawing on which artists indicated color selections, positive and negative areas, and any other important details necessary to inform print shops of the intended outcome. Artists would deliver mechanicals to local print shops such as West Coast Lithograph Co., Bindweed Press, Double-H Press, and Tea Lautrec Lithography, among others. Seasoned print technicians then brought the poster artists’ visions to life with large printing apparatuses. At times, this process was collaborative. Technicians would offer small tweaks to better suit the overall composition informed by the process’s distinctive traits. Often, technicians would even mix inks with artists present to ensure a good match. Photo-offset lithography was the ideal medium for dance hall posters because it allowed room for modification and experimentation while also allowing for the production of multicolor designs at an affordable rate. In each case, technicians carefully adapted the initial drawing to ensure clarity and vibrancy in the final image. Crisp plate-making processes ensured that each plate lined up just right so that after the final pass, the image blended into a uniform design.

Aligned with the technical turn in art historical scholarship, as exemplified by the work of such scholars as Francesca Bewer, Caroline Fowler, and Pamela Smith, my discussion of psychedelia’s experimental approach to print is rooted in the materials and techniques used by artists to achieve the final effect.

3 Though often relegated to the periphery of conversations surrounding the posters themselves, a closer look at their development helps to reveal the material reality of a visual style marked by immaterial signifiers—mind-expanding drug experiences, dreamy atmospheres, and fantasy imagery. For instance, both in part due to the expedited timeline of dance hall posters and an affection for nostalgia, psychedelic artists often employed repurposed imagery in their paste ups. Decades-old postcards, photographs, advertisements, and other cast-off items one might find in a thrift shop found new life in psychedelia’s rapidly growing visual culture. Once cut out, copied, and placed in the final design, artists would then hand-letter information such as the musician’s name and performance dates around the image before submitting the design to the printers. Therefore, these artists (and occasionally the promoters who commissioned the designs) were equally curators of found images and aficionados of hand lettering. My intention is not to construct a binary between psychedelia’s intangible history and material artifacts but to bring their deeply embedded relationship into focus by integrating the physical and embodied elements of the studio setting with the visual outcome, a point to which I will soon return.

2. The First Moving Poster

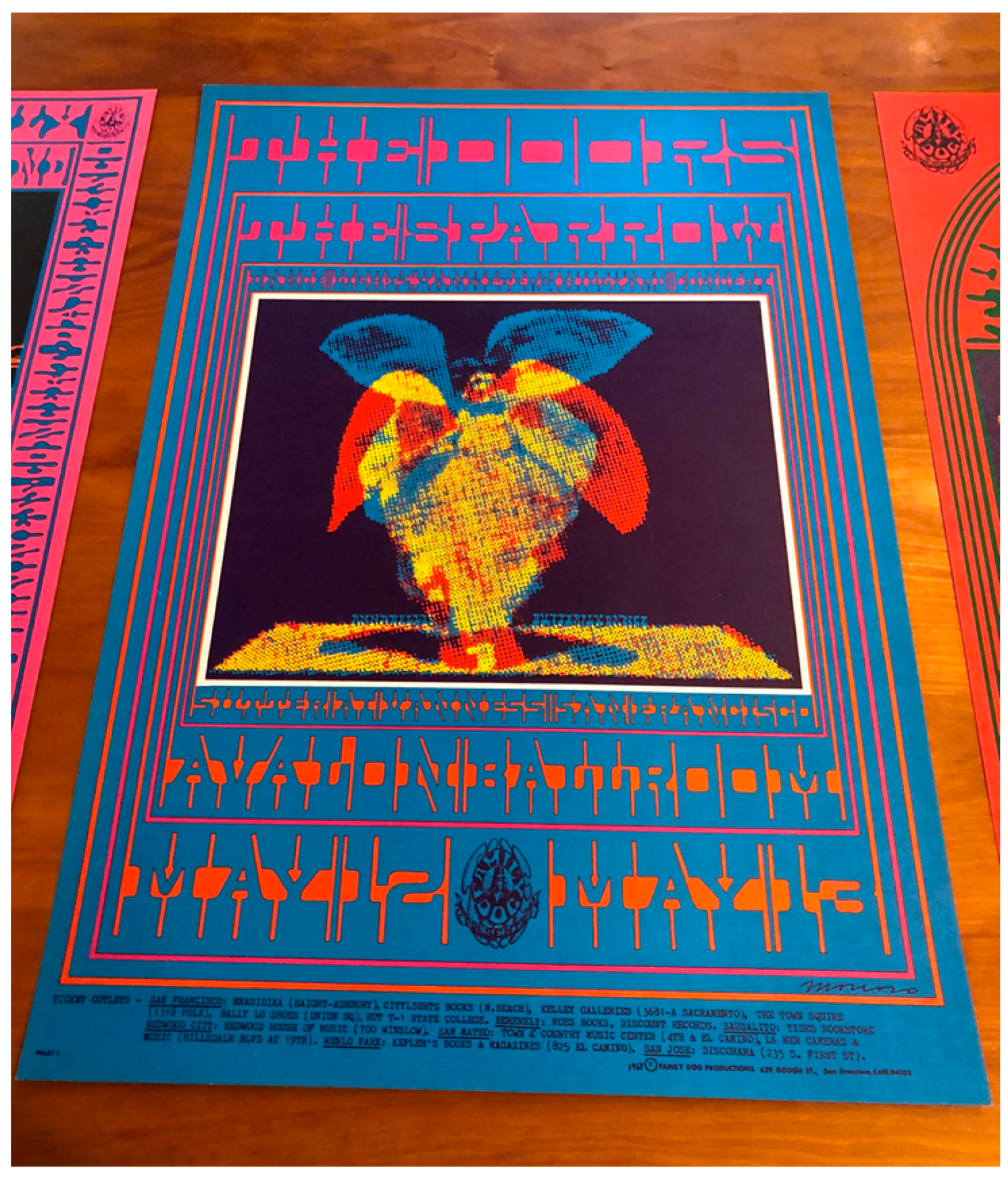

In the spring of 1967, San Francisco transplant Victor Moscoso designed a poster to advertise an upcoming performance by the Doors and the Sparrow at the Avalon Ballroom (see

Figure 1), located on Sutter Street in the city’s Polk Gulch neighborhood. Commissioned by local music production company Family Dog Productions, Moscoso’s poster followed the visual expectations of a psychedelic poster—a style quickly codified through rapid iterations after its inception in the winter of 1965—illegible lettering, imagery curated from a vintage source, and electric hues married into a single vertically oriented poster to be pasted all around the Bay Area. However, this poster departed from the status quo in a significant way. In an effort to try something new, Moscoso ignored conventional approaches to printing, which take care in precise registration for each layer, and instead asked print technicians to stack incongruous subject matter atop one another to yield a muddled mess of color, or so it seemed.

Cribbing imagery from stolen library books, vintage postcards, and other decades-old ephemera was a central tenet of a psychedelic artist’s process. Other psychedelic artists like Wes Wilson, Alton Kelley, and Rick Griffin often turned to images from the past to define a budding zeitgeist founded on a material culture of nostalgia and eclecticism.

4 Introduced in 1959, the Xerox machine became an affordable device for image reproduction, especially for creatives. Like many psychedelic artists, Moscoso stumbled upon inspiration for the poster inside a book, likely housed at the San Francisco Public Library, a frequent haunt and source of inspiration for psychedelic artists operating on quick timelines and meager budgets (

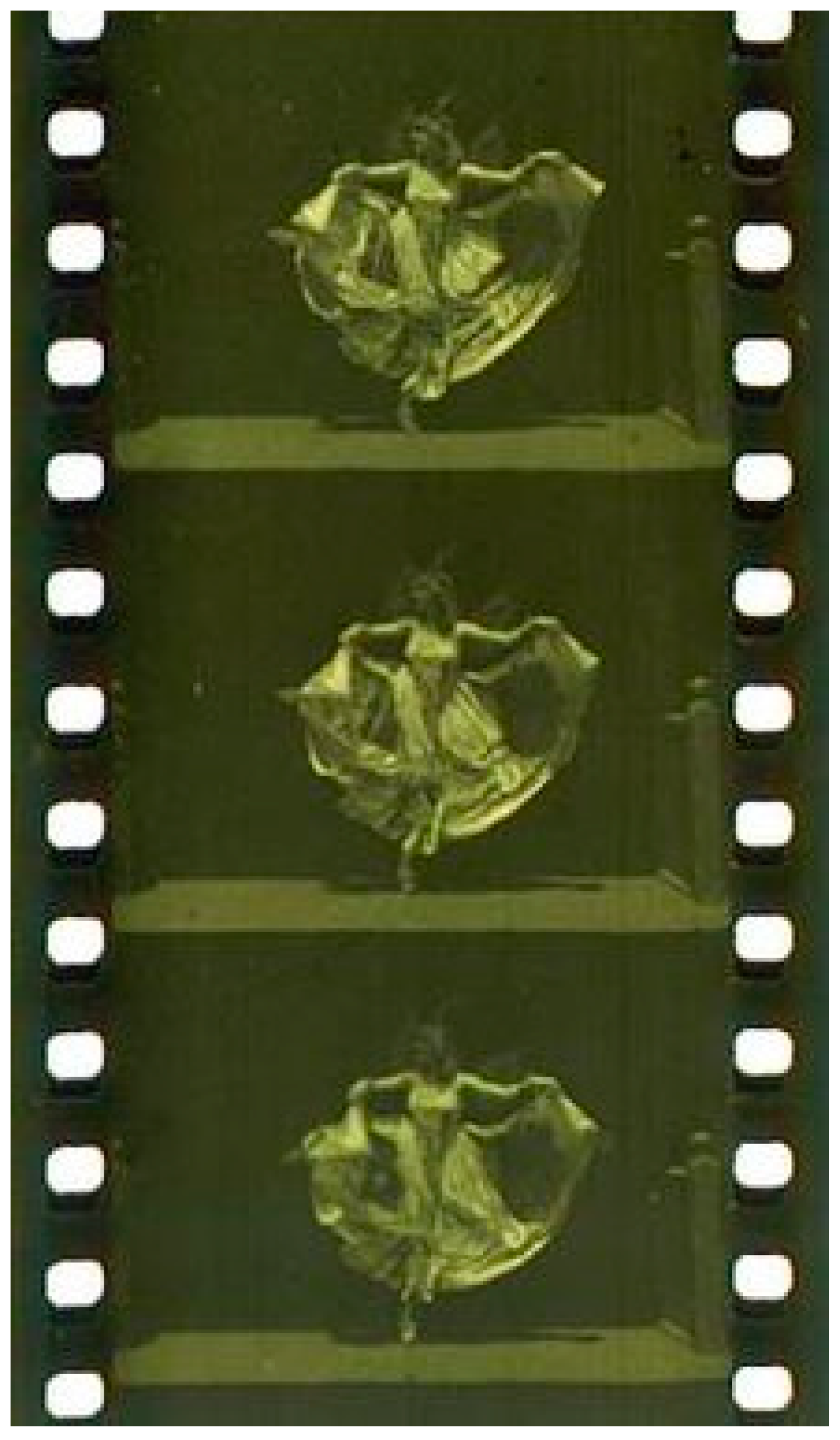

Moscoso 2005). In the case of this particular design for the Doors, film stills from

Annabelle Butterfly Dance, an 1894 film directed by Edison Lab innovator William K. L. Dickson, caught Moscoso’s attention. Rather than drafting original artwork, Moscoso used dancer Annabelle Whitford’s captivating performance reproduced in the book’s pages as the poster’s central image. Taking the book and flattening it on the photocopier bed, Moscoso duplicated selected film stills into black-and-white versions to be cut up and pasted on the poster mechanical. To give poster viewers a better sense of the overall performance, Moscoso selected three different stills showing Whitford and her billowing dress sleeves in various positions.

The Xerox photocopier was an unusual but exciting medium to explore, with immediate results and public access. Nearly anything could be made two-dimensional and reproduced endlessly, so long as it fit on the copier bed. In fact, and perhaps most obvious in a later collaboration with writer Richard Brautigan and actor Jack Thibeau, Moscoso’s appreciation for the technical innovation of the Xerox machine is most evident. Together, they developed a “magazine” titled

The San Francisco Public Library: A Publishing House in 1968, which featured the following description on its front cover: “This magazine was created and Xeroxed at the Main Library in the Civic Center using their ten cent Xerox machine”, drawing attention to the quotidian nature of the process itself when, in reality, the outcome was highly experimental and anything but ordinary. Inside, copies of Thibeau’s stomach, newspaper advertisements, and even a reproduction of a friend’s Siamese cat grace its pages (

Hjortsberg 2012). By calling the library a “publishing house”, Moscoso and his peers staked the claim that the library now held the same power as large publishing companies. With this highly democratic medium, anyone with a dime could become their own publisher without edits, endorsement, or censorship.

Once Moscoso selected the desired film stills, he needed to create transparency between each image in order to print each still atop one another (and keep each layer visible). Conveniently, the halftone dots from the book’s commercial reproduction provided the perfect opportunity to create visual space while keeping the image intact at the same time. Moscoso used the Xerox machine to enlarge each copy until the halftone dots were big enough that he felt confident they would not dissolve into a single form during the final editioning process.

5 As a result, the poster’s central image bears witness not only to its original format as a film still but also to its secondary iteration as Moscoso found it. The negative space in the figure allowed transparency between each layer, so that viewers could observe all three positions of the dancer at once.

Presented in a triad palette of cerulean, yellow, and tomato red, the dancer’s body becomes distorted as the halftone dots from each position coalesce to create a pointillist array of color. However, the dancer’s wings stand out on their own, each in different stages of “flight”. Moscoso cited his source directly in the image with the words “Annabelle” to the left of the dancer’s ankles and “Butterfly Dance” to the right. And while it remains uncertain whether Moscoso was familiar with the hand-tinted version of the film, with its many colors shifting across Whitford (See

Figure 2), for those familiar with the later version of the film, the resemblance is impossible to miss. Along with the enlargement of the halftone dots, color serves as the key mechanism to create visual clarity amidst Whitford’s fanciful dancing, which would otherwise be reduced to an indeterminate outline, akin to the aftermath of a snow angel in fresh snow.

In his self-authored book, Sex, Rock & Optical Illusions, Moscoso reflected on the Doors poster, which at the time was simply another job to complete and another opportunity to experiment with a new idea. It was not until radio host and friend Howard Hesseman directed Moscoso’s attention to the poster’s unique feature that he realized what he had made in this explorative design:

Howard Hesseman, who introduced me to my wife Gail (thanks, Howard), had his hallway all papered with posters and lit by blinking Christmas lights. He said to me, “Victor, that poster you did for the Doors, the lady flies”. The moment he said it, I knew what I had done; it was only an accident the first time.

It was only an accident the first time. Moscoso’s quick reclamation of this happenstance awakening to the mechanics at play in the Doors poster emphasizes the experimental nature of the psychedelic poster scene. Required to churn out new posters weekly, Bay Area artists mobilized this commission-based format as an incubator for design experimentation, testing the limitations of two-dimensional surfaces on the dime of local production companies. When good ideas struck, they stuck. Initially, the Doors poster was simply another attempt to reinterpret a found image in a new way, using color and hand lettering to find a fresh look. But when placed in just the right context, a new, more exciting development appeared. Hesseman’s observation underscores the crucial factor of site specificity embedded in kinetic lithographs. With each alternating hue of the Christmas lights, the poster became something new—a time-based medium dependent on the duration of each light’s glow. With this enlightening experience, formally trained Moscoso could easily dissect the technical reason his design worked in that specific way once he focused on it; however, he may not have ever recognized the design’s potential without the twinkle of red and green and a kind friend guiding him there—a bit of kismet rooted in the medium.

When viewed in stable white light, the imagery in kinetic lithographs appears as double (or triple) exposure photography. Dizzying at first glance, the composition is only clarified by flashing lights of the same hues, whether the poster is witness to a psychedelic light show at a dance hall or staged in a museum context. Each layer of the print dissolves one by one as light of the same hue washes out the ink on the page. Red ink vanishes in red light, only to reappear as blue light strikes the poster’s surface seconds later. In effect, the dance hall becomes the organizing mechanism, but only for a moment or two. Despite promoters’ small printing budgets, this inventive mode of making enabled Moscoso to participate in the burgeoning media art landscape of the 1960s by looking backwards to the nineteenth century via subject matter, process, and cinema.

Through iterative experimentation, Moscoso continued to test the limits of photo-offset lithography to make use of the existing dance hall surroundings–no outlets or bulky video projection equipment required on his end. Instead of plugging in a projector, he could simply hang a lithograph on the wall, wait for the show to begin, and watch the lights shift the composition throughout the night. Of course, the psychedelic light shows themselves required electricity—but in terms of the print itself, it simply had to find its light. Consequently, this strategy highlights the inherent reflexivity of psychedelic ephemera and its surrounding built environment. Unlike a ribbon of film, which links each frame together in a linear fashion, the stacked registration of a kinetic lithograph compresses the “scene” into a single moment, creating a visual cacophony of storytelling until placed in the dance hall’s embrace. The legibility of the poster is entirely dependent on its environment, destabilized in conventional viewing settings.

Along with Moscoso’s autobiography, curators and collectors alike have concentrated on his formal training in biographical essays, placing a strong emphasis on his knowledge base as a key factor in his success as a poster artist. A common refrain of Moscoso’s is, “The better you know the rules, the better you can break the rules” (

Moscoso 2005). However, in the instance of his kinetic lithographs, though his formal training may have led him near innovation, his surroundings solidified the breakthrough. In other words, Moscoso’s talents are often exclusively attributed to his storied pedigree but fail to acknowledge the magic of the psychedelic print—the iterative, collaborative, and occasionally miraculous spontaneity of art and design fueled by a relentless schedule of performances that landed San Francisco a spot on the international music scene.

In part, this gap in scholarship is due to art historical convention, which favors single-artist narratives and the quandary posed by an incomplete archive, obscuring much of the nebulous network implicit in psychedelic poster production. Film historian Gregory Zinman shares in this frustration from a different vantage point, describing scholarship surrounding the psychedelic light show as disappointing. He writes:

Light shows also featured collaborative work among artists operating in a variety of mediums, and thus scholars who are more comfortable dealing with works by a single author or artist find them hard to analyze. The collective memory of the light show, which was poorly understood and scarcely documented, retains the shorthand of shallow classic-rock spectacle or countercultural kitsch.

Similar can be said of Moscoso’s posters and those of his peers. Although these posters are simultaneously admired and sought after by collectors, art historians have rarely dug deep into their complex histories. To call either the kinetic lithograph or the psychedelic light show “kitschy” would be to ignore its tremendous impact on society. As media scholar Fred Turner has argued, countercultural media had transformational properties within community settings. He states, “Their makers shared an understanding that media should be used to create environments”, continuing, “that such spaces could produce individual psychological changes, and that altered audiences could ultimately change the world” (

Turner 2013). In other words, the immersive realm of the dance hall was more than a spectacle; it set the tone for a new way of connecting with each other—a crucial ontology for San Francisco’s counterculture community.

3. A 50th Anniversary Spotlight

In 2017, multiple exhibitions popped up to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Summer of Love.

6 In San Francisco, the de Young Museum curated an immersive overview of the legendary summer of 1967. The Summer of Love Experience: Art, Fashion, and Rock + Roll opened April 8 and ran through August 20, 2017. The exhibition was curated by Jill D’Alessandro and Colleen Terry, along with Victoria Binder, Dennis McNally, Joel Selvin, and Ben Van Meter (

D’Alessandro and Terry 2017). Kicking off in a chronological fashion, visitors were greeted with elements of the Trips Festival, a three-day event in January 1966 that has become nearly synonymous with the start of the hippie boom. Afterward, the exhibition shifted into different realms of the memorable era, including fashion, photography, and, of course, ephemera, particularly posters.

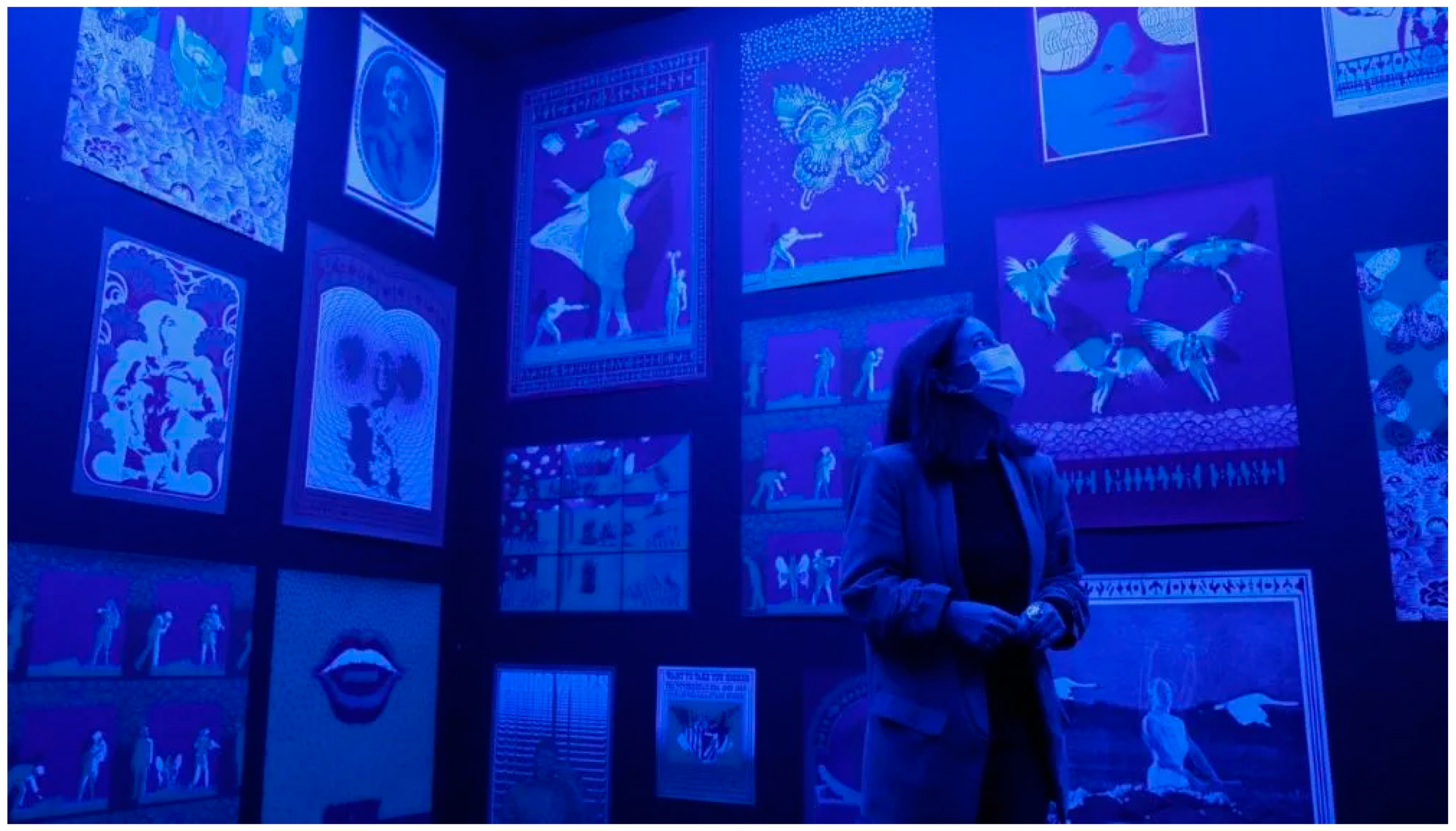

Of particular relevance, the final segment of the exhibition, titled “Making Posters That Rock” and curated by conservator Victoria Binder, featured Moscoso’s kinetic lithographs (See

Figure 3). This area of the gallery centered on the materials utilized by artists and printers alike to develop the vibrant visual culture of San Francisco’s psychedelic age. Binder directed a film with printer David Lance Goines to illustrate the process of photo-offset lithography and help visitors get their bearings on this technical aspect of the show. “Though the posters are recognized around the world”, Binder remarked in her catalog essay, “few people know the story and process of how they were made” (

D’Alessandro and Terry 2017). The pieces shown in display cases and on the walls helped unfurl the hidden layers of experimentation and skill represented by each poster. Lithographic plates, acetate sheets, film negatives, and other tools of the trade paired with didactics demystified commonly held misconceptions—especially the misguided notion that San Francisco’s poster artists relied on Day-Glo ink for their vivid compositions.

7But the most captivating element for visitors, without a doubt, was Moscoso’s kinetic lithographs, and understandably so. On a bright-red wall bisecting the room, several circular portals beckoned visitors to peer inside. Gazing inward, viewers were met with an otherworldly dimension of animation. As lights flashed, the posters’ subjects appeared to fly, dance, wave, talk, and even explode! Above the portals, framed originals of each poster hung on the wall. Isolated in dark frames, the largest posters hung in the center, with smaller posters on the edges. In effect, the five framed posters appeared as film posters advertising the cinematic surprises below. Out of the five selected, the Doors poster was included, as well as the Youngbloods poster—Moscoso’s first intentional moving poster. The installation of the original kinetic lithographs above the portals allowed viewers to carefully contemplate the still images and then experience them in action seconds later, enabling them to oscillate between each presentation. Further, the decision to frame the kinetic lithographs individually signaled that they were clear outliers from the other posters in the exhibition. In an effort to ditch the frame, preparators sandwiched the rest of the posters between layers of plexiglass attached to the wall, using standoff hardware to make it appear as though the posters were papering hallways, dance hall walls, and other local venues, just as one would have experienced them in their original context.

But the framed moving posters served an important role. They seemed to act almost as a pause button to ponder and better make sense of the chaos of the miniature light shows’ effect, a foil to the portals’ disorientation. But they also enabled visitors to connect what they had learned regarding the process of making posters to finished versions by looking closely. Certainly, Moscoso’s kinetic lithographs are no less disorienting under stable light—a true paradox. With incongruent layers stacked atop one another, yielding a jumbled composition, the framed posters performed better as didactic tools than visual resolutions. This contemplative portion of The Summer of Love Experience permitted visitors to stand in the shoes of both artist and viewer. Equipped with a crash course on inks, matrices, and editioning, visitors could observe the poster’s mechanisms in action and then stand back seconds later to identify the artistic choices that contributed to the overall effect. Perhaps, rather than a pause button, a better comparison is a light switch. Moving from portal to frame, one could see the poster turned on and off—emphasizing the integral role of the dance hall to the poster’s full effect.

Furthermore, the portals were not only engaging but also practical. The museum’s installation timeline and other demands of the exhibition made it difficult to complete a full risk assessment regarding the flashing lights and their impact on these fragile works on paper. Therefore, to prevent any potential damage, de Young Museum conservation staff suggested the use of facsimiles in the portals to avoid the potential ramifications of long-term illumination from the colorful lights (

Gupta and Binder 2017). Because kinetic lithographs rely on color and form to make the posters “work” under the lights, not specific inks or papers, the reproductions did not impact viewers’ experience with the artworks.

4. A Homecoming Celebration

In 2021, an exhibition in Moscoso’s hometown—A Coruña, Spain—also featured his kinetic lithographs in an isolated context within the broader exhibition, further underlining their eccentricity as a medium. Moscoso Cosmos: the Visual Universe of Victor Moscoso was a retrospective exhibition focused exclusively on the work of Victor Moscoso that ran from 14 April through 10 October 2021 (after significant delays due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic). Filling two rooms of the Fundación Luis Seoane, the exhibition displayed the largest public collection of Moscoso artworks in Europe, belonging to the Concello da Coruña. The exhibition was co-organized by the Fundación Luis Seoane, A Coruña; MUSAC (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León); and Centro Niemeyer, Avilés, with the collaboration of AC/E—Acción Cultural Española. Curator David Carballal worked with Moscoso, who managed the art direction himself, to bring together a lifetime of work including psychedelic posters, underground comics, illustrations, album covers, and animations.

Though not his first solo exhibition, Moscoso Cosmos was an especially exciting project for Moscoso, allowing the artist to revel in his successes in his hometown. In 1936, approximately two weeks after the start of the Spanish Civil War, Moscoso was born in A Coruña, the most northwestern province of Spain. Less than four years later, he moved with his mother to Brooklyn, New York, following the war’s end. His father, born to immigrant parents in New Jersey, held dual citizenship with Spain and the United States and awaited their arrival on the East Coast of the United States after departing Spain earlier to avoid military conflict (

Carballal 2021). As he grew up, Moscoso attended the Industrial Art Institute in Manhattan and Cooper Union, where he trained under Abstract Expressionist Franz Kline.

However, after graduation, Moscoso was disappointed in the opportunities available to him as a commercial artist, so he enrolled in graduate school at Yale University with then-girlfriend Eva Hesse. After completing his studies in New Haven, the Beat movement captured Moscoso’s interest as a musician and artist, leading him to Berkeley in 1959 following graduation. Upon arrival in the Bay Area, Moscoso returned to school, this time for postgraduate studies at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) to avoid being drafted into military service (

Carballal 2021). After two years, he became an instructor of stone lithography for the college for about a year. His musical interests quickly pulled him into the Bay Area’s underground scene. Eager to participate and make connections, he worked as a window dresser to make ends meet in the meantime. Only a few years later, Moscoso made his first psychedelic poster, and the rest is history, or at least is included in the retrospective exhibition.

Importantly, the exhibition highlighted posters that Moscoso made not only for San Francisco promoters but also under his own company, Neon Rose. In December 1966, Moscoso started Neon Rose to find more freedom and creative license in the poster-making process. Neon Rose had an exclusive partnership with another dance hall located on Fillmore Street, the Matrix. It had a smaller budget than other dance halls in the area, so Moscoso cut a deal with the venue, offering 200 free posters in exchange for unlimited printing rights and all the poster profits.

8 Neon Rose also completed jobs for bands, poets, and other creatives in the area. A businessman at his core, Moscoso wanted to be in full control of his creative enterprises, protected from club promoters’ whims and other design mandates. Under his own company, Moscoso continued to experiment with kinetic imagery. One of the first moving posters to come out of Neon Rose was a custom holiday mailer for a longtime friend, the Cuban film-title designer Pablo Ferro, who attended the Industrial Art Institute alongside him in his younger years.

As visitors moved through the exhibition, they happened upon a small, glowing room with a cartoonish opening. Designed to house the kinetic lithographs in the exhibition, Carballal created a semienclosed space to better experience them. Tube lights hung around the ceiling’s perimeter and radiated varying hues, including red and green (see

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Since Moscoso did not make a lot of kinetic lithographs, there were multiple versions of the same posters tacked up on the room’s three walls. A few other experimental posters also shared the space. The room featured a mixture of posters created for Family Dog Productions and Neon Rose. The Family Dog Productions posters (like the Doors poster) are smaller, often measuring 14 by 20 inches, whereas the Neon Rose posters are larger, typically measuring at 22 × 28 inches. The space also held later works, including a poster created for an American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) lecture and an exhibition poster made for Moscoso Cosmos, which uses elements from an unpublished poster, “Two Ton Mustard Seed”. It is not clear whether the posters in this portion of the gallery are facsimiles, but the effects remain the same regardless.

Unlike the portals at the de Young Museum, visitors could enter the dynamic room and shift under the colorful hues alongside the posters’ cast of characters, including a hovering set of lips and floating butterflies. Looking down at one’s hands, glancing across the room at someone else’s face, staring at one’s shoes—the impact was universal (see

Figure 6). The shifting lights above stood in the way of a museum’s conventional aims. Changing constantly and skewed by their environment, the lighting eliminated visual stability. As the posters oscillated between the categories of print and animation, beholden to the lights’ steady flash, the ritual of the museum’s concentrated gaze was substituted for the ritual of the psychedelic dance hall, one centered on communal engagement and embodied participation. As Carol Duncan explained in her seminal 1995 essay, the sacredness of the modern museum is deeply tied to its uncluttered and individually lit displays that isolate objects, subsequently elevating them to an otherworldly level through aesthetic choices (

Duncan 1995). However, although Carballal’s installation of the kinetic lithographs could not be further from the white cube world Duncan refers to, I argue it functioned in a similar manner and created a ritual of its own: still an entirely different mode of being but one without the baggage of poised expectations and revelatory observations—one could simply

be. In its original context, the light show “provided a means of deemphasizing the individual in favor of collectivity”, and the same is true of the communal experience of museum goers (

Zinman 2020). Regardless of identity, the lights cast a uniform glow onto everyone in the room, projecting a new, heavily saturated existence that allowed visitors to step outside of themselves.

5. Psychedelia’s Liminal Materiality

Without the trappings of a pseudopsychedelic dance hall, particularly the flashing lights, the kinetic lithographs lose their boundlessness and become inert in the museum—similar to how art historian Bissera Pentcheva describes the Byzantine icon which “performed through its materiality”. Describing the flicker of candle flames, swirling incense smoke, and noisy auditory environment, she asserts that “in saturating the material and sensorial to excess, the experience of the icon led to a transcendence of this very materiality and gave access to the intangible, invisible, and noetic” (

Pentcheva 2006). However, when situated in a “glass-cage” in the museum, the icon’s life is stripped away completely. Importantly, the key culprit for this lifeless display is “uniform and steady electric lighting”, and Moscoso’s posters are no different. As mentioned earlier, the manipulation of the offset-photo lithography process is precisely what enabled Moscoso to transform this printed ephemera into a time-based medium—its materiality makes the intangible nature of its movement possible. The technical process employed by the artist and printers facilitates the experience, the ink’s imperfect registration and handpicked palette unleashing a portal into a phantasmic presence—but only if placed under the right conditions.

Under the flashing lights in both the portal displays at the de Young Museum and the room installation at the Fundación Luis Seoane, the lithographs are especially peculiar objects as animated scenes without screens, their closest analogue perhaps being a flip book—but even for these, the experience is mediated by one’s own hand. Kinetic lithographs are a more autonomous medium, like a film, in that they keep moving regardless of one’s interaction with them. As Kate Mondloch writes, screens in the conventional sense function simultaneously as immaterial and material entities: “The screen’s objecthood, however, is typically overlooked in daily life: the conventional propensity is to look

through media screens and not

at them” (

Mondloch 2010). In this unique instance, the posters serve as the screens by which a visitor views the animations. However, since the animation’s various frames are forever locked onto the surface, it becomes nearly impossible for viewers to look past the poster’s surface and forget the material reality before them. Without the flashing lights, looking at one of Moscoso’s moving posters is like seeing a film all at once. Carballal’s immersive room allows the posters to transcend their material realities by way of their environment—it makes looking

through them possible in a way that a conventional installation would make difficult.

Recent scholarship surrounding psychedelia has most predominately emerged in fields like communication, film, media studies, and musicology rather than art historical inquiries, as psychedelia’s printed history is eclipsed by the flashing lights and sonic drone of the psychedelic dance hall. Further, art historian David Joselit has argued that the “visual culture of psychedelia was devoted to dissolving objects into optical pulsation”, equating its visual tactics to Nam June Paik’s media art, such as “Magnet TV” from 1965, for its scramble of lines and dissolving forms, or, more succinctly, a “dancing pattern” that reflected much of Aldous Huxley’s description of a psychedelic trip (

Joselit 2007;

Huxley 2009). Joselit’s comparison to Paik is important; it highlights a connection between mid-twentieth century media and psychedelic ephemera as highly recursive media. For Paik, distorting the television’s signal threw open a door to enormous potential in terms of technology manipulation. The same is true for Moscoso, who eschewed standard plate preparations and printing practices to uncover a way to bring print into a time-based category. However, if we take the charge of “dissolving objects” too seriously, we stand to lose much of psychedelic ephemera’s rich visual and material culture, founded upon cut-and-pasted photocopies. Joselit’s statement is not unusual; it echoes common sentiments regarding psychedelia, for example, that it is a tool to aid in a druglike experience or a portal to expand consciousness, even, and this is true. But it is also only part of the story.

Beginning as tangible ephemera, such as a postcard, magazine page, or book plate, psychedelic posters are the result of exploring the potential of print and its many iterations. Stepping away from close looking as the central method of analysis and looking to technical art history, oral histories, and other archival sources allows for the acknowledgement of psychedelia as a highly social realm, demanding an awareness of its tactile qualities and circulation to fully comprehend its context and function. By doing so, through immersive displays and detailed technical lessons, museums can restore the broader network of designers, printers, promoters, and other crucial roles involved in their production. Exhibitions like those at the de Young Museum and the Fundación Luis Seoane offer ideal opportunities to have these conversations, giving visitors a chance to witness this extremely visceral medium.

6. A Postwar Kinetoscope

The poster itself as a medium is an element of nostalgia, a mode of communication that had faded in the wake of radio and television during the mid-twentieth century. Art historian Elizabeth Guffey notes that the poster aligned with San Francisco hippies’ overall obsessions with the past, “apparent in the cast-off Edwardian frock coats and stove-pipe hats” throughout the city, particularly the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Guffey implores us to recognize the value of understanding “retro” as a “non-historical way of knowing the past”, a relationship to objects that requires a sense of detachment to create space for new meaning (

Guffey 2006). I argue that Moscoso’s kinetic lithographs embody this notion explicitly. While Guffey is referring more to items and motifs, exhibitions like those discussed in this essay expand this concept into technical processes, such as the iterative experiments which enabled poster artists to reimagine a century-old mode of printing. By refuting standard practices of offset-photo lithography, Moscoso mobilized the past for an updated way of communicating that suited psychedelic sentiments of escape and imagination. Though his kinetic work allowed him to dabble in the burgeoning media art landscape of the 1960s, his subject matter allowed him to stay connected to the past.

When Moscoso developed his first (accidental) moving poster, he started with film stills intended for a kinetoscope (See

Figure 7), an early motion picture device that allowed one person at a time to view a film through a small peephole. It, too, like the kinetic lithograph, was an illusion that relied upon a bright, shifting light in order to appear in motion. A simulation for one, the experience of using a kinetoscope reflects the portals at the de Young exhibition, as one can peek at a spectacle that is otherwise enclosed and separated from our environment. On the other side of the spectrum, in the case of the Fundación Luis Seoane, expanding the light’s cast to the entire room allows the museum to shift into the dance hall’s original context—an updated, large-scale collective kinetoscope made possible by fluctuating lights.

Maybe the most important distinction between the portal installation and the immersive room is the role of an embodied perspective. The escapism of the posters was twofold; the colors and patterns created an otherworldly sensation, while the citations of the past via the source imagery acted as something of a time machine. As Jean Baudrillard reveals in

The System of Objects, an antique can serve as a “mythological object” which allows the user or owner to gain a “projective myth” of its origins. “The antique object no longer has any practical application”, Baudrillard explains, “its role being merely to signify” (

Baudrillard 1968). Though the posters did originally have a practical application—advertising the dance hall—they slowly became something more, signifiers of a new sociality within the Bay Area, and embedded in that way of being is the transportive, ritualistic space of the dance hall.

This social significance remains intact, even now, as these moving posters enter the museum, long detached from their original dance hall context. The posters construct a time warp that oscillates between the past and the future, while the viewer remains planted in the present. Constant reconfigurations of media and space in light shows (even when reproduced in a museum setting), due to “the tinkering with, the manipulation of, and the literal and metaphorical rewiring of technologies”, open individuals’ minds to a “radical new sociality” (

Zinman 2020). Given the social and cultural upheaval of the 1960s, this claim undoubtedly also carries political weight. When conceived as an element of social engagement, the installation of Moscoso’s kinetic lithographs raises larger questions about how visitors are meant to engage with museums and their offerings.