Abstract

This article explores the use of echoes in early modern theater, particularly in the context of opera. By examining the incorporation of echoes in plays, libretti, and scores, the article argues that the Ovidian trope of Echo occupies a fluid space spanning textuality and performance. The article begins by delving into how the sonic essence of Echo was conveyed in early modern dramatic texts and conceptualized in coeval theoretical writings, forming a continual negotiation between the specific features of the performance and the endeavor to record it on the page. Subsequently, it looks at the appearance of Echo in Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, offering it as a case study for evaluation through the lens of modern performances and the interpretive questions they raise.

Keywords:

Echo; opera; Giovan Battista Guarini; Angelo Ingegneri; Claudio Monteverdi; L’Orfeo; textuality; performance 1. Introduction

In Act 4 of Giovan Battista Guarini’s Il pastor fido (The Faithful Shepherd, Guarini 1590), the protagonist Silvio laments about love. His disappointment leads him to raise his voice when addressing Cupid, thus eliciting an echo from the surrounding space. Silvio—clearly familiar with the Ovidian tradition—immediately questions whether the response he just received comes from Ovid’s nymph, Echo, or maybe from Cupid himself. As is the case with the Latin poet’s seminal account of the dialogue between Echo and Narcissus, the conversation unfolds deceptively, with the shepherd convinced that he has been talking to the god of Love. For sure, the invisibility of both Echo (the nymph) and echo (the sonic effect)—or rather, their immateriality, though the immateriality of voices and sounds may be debatable—makes them most elusive, calling into question the very status of Echo as a being and the essence of echoes as invisible, yet audible phenomena.

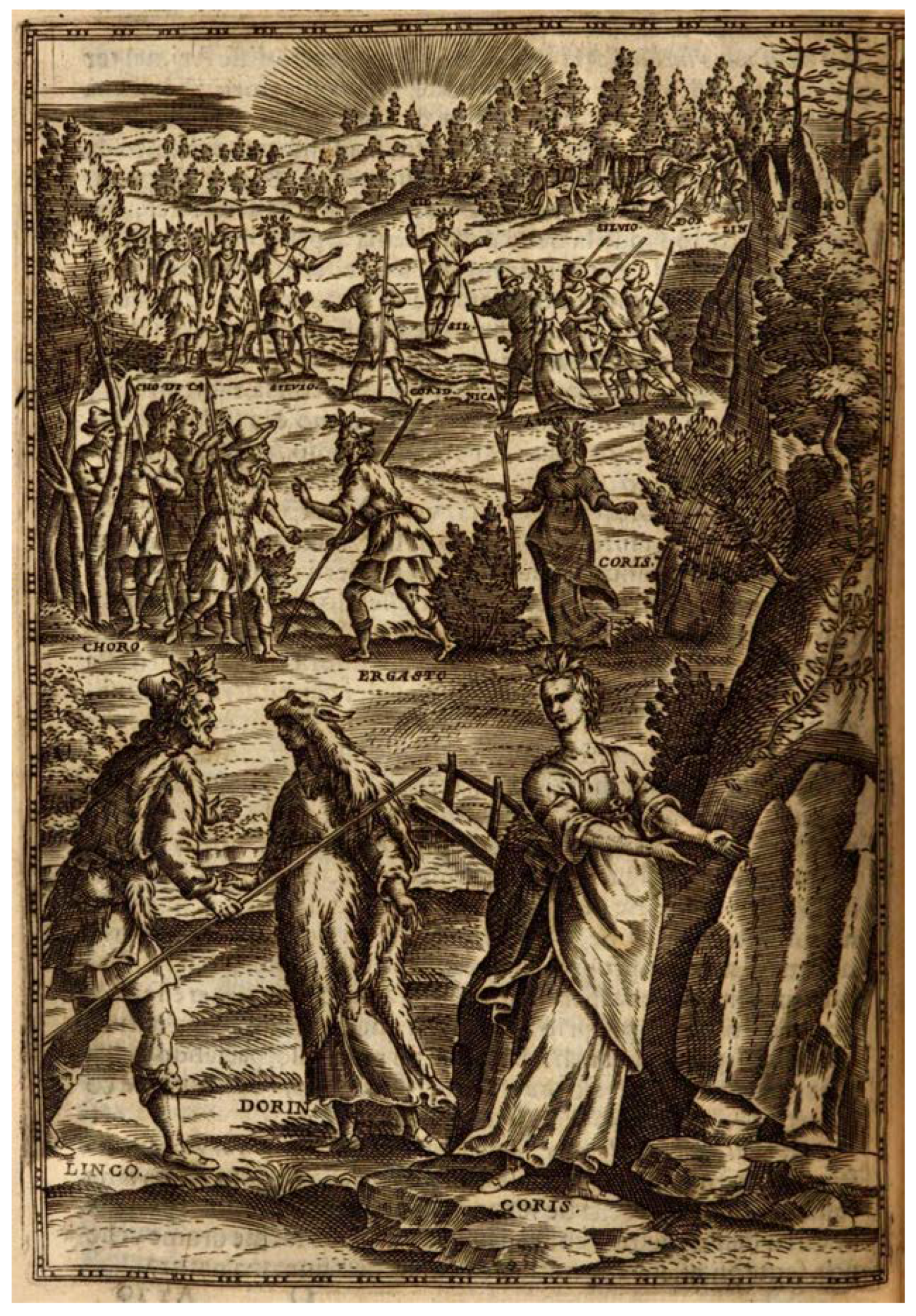

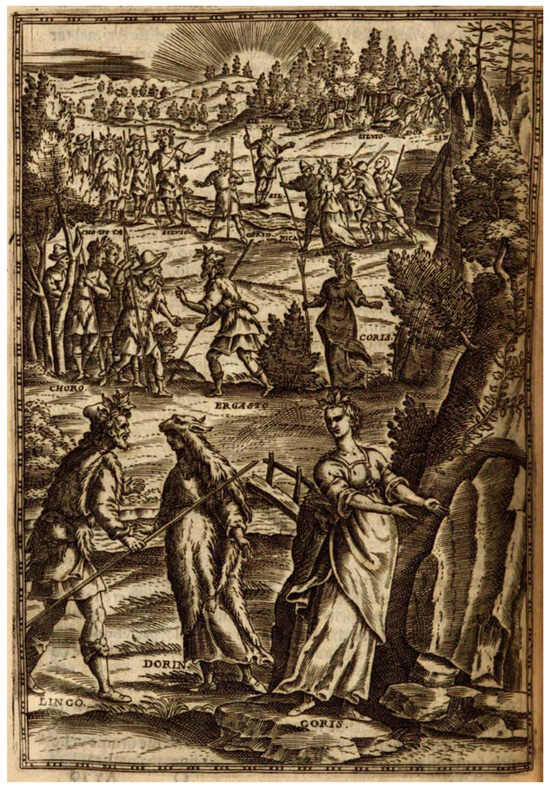

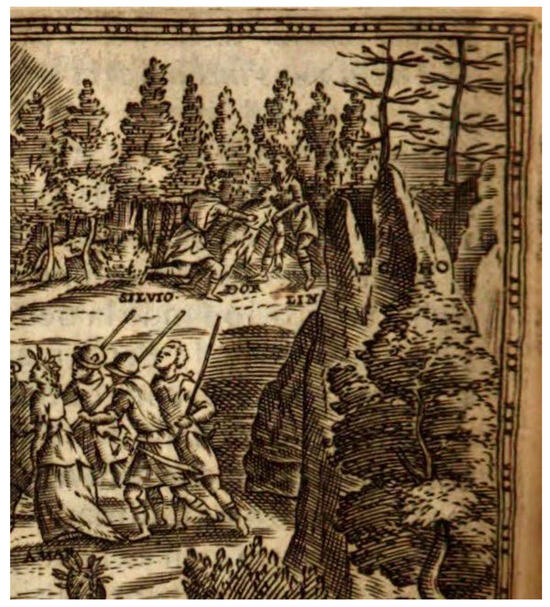

Not quite a voice, but the “image of a voice”, as Ovid himself describes her, Echo emerges as an exceptionally adaptable figure.1 After her body is consumed by grief, her existence as pure voice allows her to blend seamlessly with the spaces in which she is heard. Accordingly, in the illustration that opens Act 4 of Il pastor fido in the Venice edition of 1602, Echo is there—and yet she is not.2 Taking inspiration from the format of full-page illustrations utilized for epic poetry since the mid-sixteenth century, the engraving (Figure 1) portrays diverse scenes spanning multiple spatial layers.3

Figure 1.

Guarini, Il Pastor fido (Venice: 1602), Act 4, p. 242.

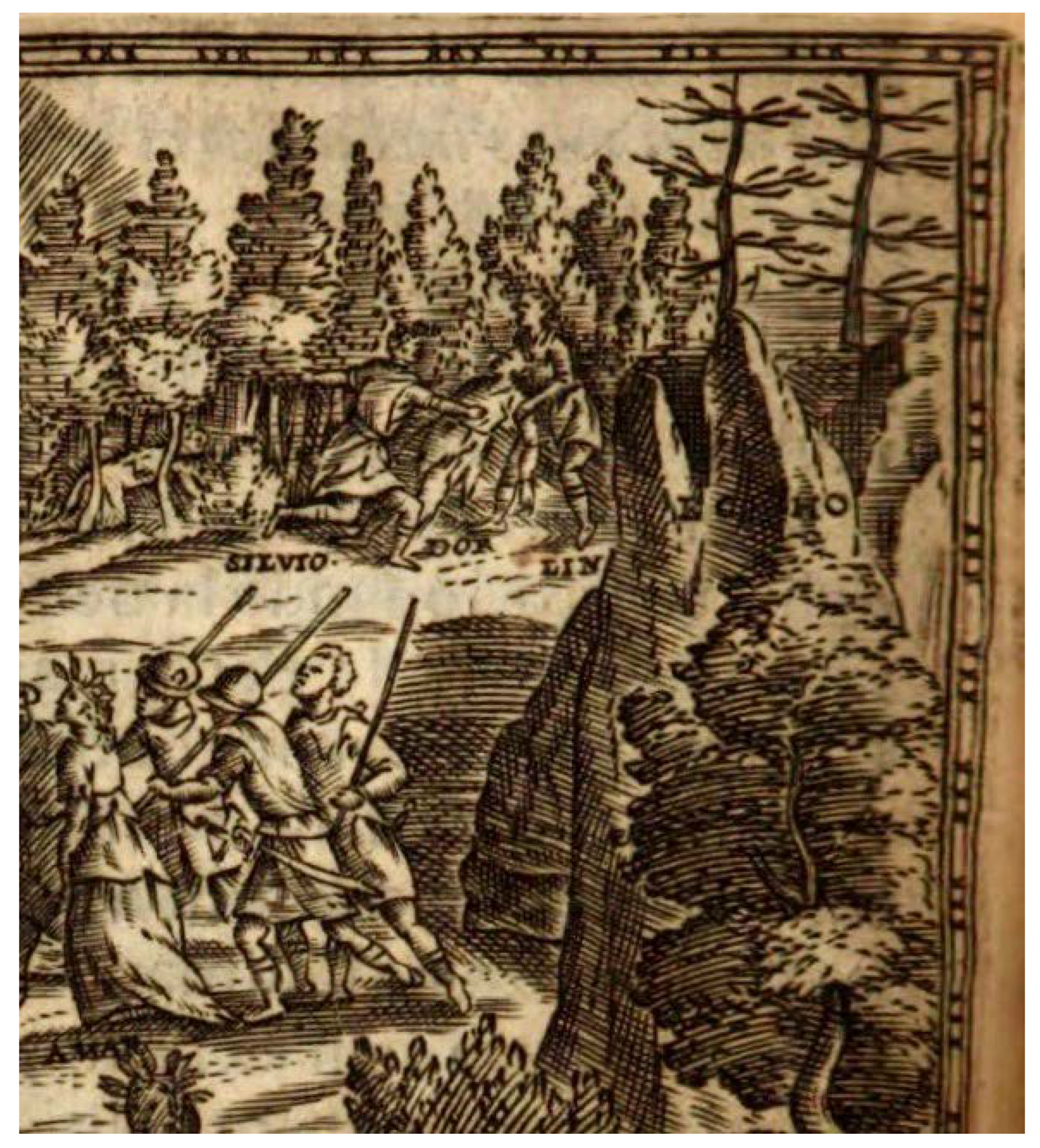

Each character is represented with an abbreviated version of their names, serving to identify them. Echo’s name does appear in the illustration too, specifically in the upper right corner of the image (Figure 2), near a depiction of a landscape suggesting mountains and caves.

Figure 2.

Guarini, Il Pastor fido (Venice: 1602), Act 4, p. 242, detail.

In fact, the configuration of the concave recess, marked by a deep crevice, is quite distinctive, evoking real spaces long associated with powerful echo effects. One might consider, for instance, the so-called Ear of Dionysius in Syracuse, as well as other locations, both natural and artificial, that have traditionally been highlighted in the relevant literature.4 Echo’s ethereal essence is symbolized by her reduction to a mere name, her visual presence blending with the space that designates her and facilitates the occurrence of her reverberations.

Echo’s appearance in Il pastor fido and her invisible depiction in the engraving encapsulate the paradoxical nature of a trope that teeters between the memory of Ovid’s nymph and the acoustic phenomenon from which she takes her name. What (or perhaps who) is Echo? Does she exist on her own terms, or is she simply the product of reflected soundwaves? Is she truly responding to those who trigger her, or is she a mere—if unacknowledged—reflection of their utterances? Does she possess a vocal timbre of her own, or is the sound of her voice a narcissistic reflection of those who speak first? And in that case, does it even make sense to conceive of her as having a gender? While these questions might appear unconventional, their importance in the broader cultural history of the trope becomes evident when one delves into the ways that the reception of Echo as an Ovidian character intersects with the (after)life of echo as a poetical and rhetorical device. As I wish to argue in this essay, these imbrications are thrown into high relief by early modern theater, opera in particular, where Ovid’s nymph was a regular presence, to say the least.

In this context, Echo occupies an exceptionally fluid textual realm, where the interplay between materiality and immateriality intertwines with questions about gender, self-reflexivity, agency, and vocal expression—all questions that, extending beyond the confines of early modernity, allow us to establish a theoretical framework for transhistorical examinations of the intricate interplay between textuality and performance. Indeed, the enduring fascination with Echo, which has captivated poets for centuries, reflects a broader interest in the possibility of weaving voices and sonic effects into literary texts. As an extreme example of a verbal text existing solely as an acoustic reverberation of someone else’s utterance, Echo’s words challenge conventional assumptions about textuality and the place of writing as the primary means of recording it. As convincingly argued by recent scholarship across classical reception and voice studies, poetical texts possess the ability to convey and perform Echo’s unique vocal essence through a variety of exquisitely textual devices, which, at the same time, manage to capture voice and make it heard by the readers.5 Yet, when considering Echo’s peculiar textuality through the lens of performance, one realizes that she captures the paradox of something seemingly immaterial—a purportedly disembodied voice—whose existence hinges on the distinctive materiality of the performance, including the built environment where the performance unfolds, the bodies that inhabit it, and the traces (textual, visual, musical) that, across time and space, make it possible for the performance itself to be revived and for voices long departed to be reanimated.6

In order to assess the particular status of Echo across textuality and performance, I will examine a few late-Renaissance examples (plays, libretti, scores, theoretical writings) to suggest that they are better understood when we adopt a more flexible notion of text—one that engages in a constant dialogue with the inherently transformative context of the performance—and also when we adopt contemporary performance practice as a primary tool with which to evaluate performative works from the past. After considering one instance of Echo’s afterlife as a strictly Ovidian character (an anonymous Florentine intermezzo about the story of Echo and Narcissus), I will turn to discussions of Echo’s textual implications as stirred by the debate surrounding Il pastor fido, including Guarini’s own annotations to the play and Angelo Ingegneri’s treatise Della poesia rappresentativa e del modo di rappresentare le favole sceniche. These texts will help me outline both the ways in which drama incorporated echoes as part of the script and the theoretical framework behind them. I will then close in one case study (Echo’s appearance in Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo) that allows me to bridge across material textuality and performance. In doing so, I also aim to show that the interplay between textuality and performance is pertinent to the methods through which editorial practices seek to capture the transiency of performative events on the written page.

2. Capturing Echo

Seminal studies on Echo in Renaissance poetry and theater attest to the enduring influence of Ovid’s loquacious nymph.7 In this large repertoire, the juxtaposition of Echo as a character from classical mythology and echo as an acoustic phenomenon, replicable through poetry and enacted on stage, offers a rich terrain for assessing the interplay between textuality and performance. But where can Echo be found, and how does she actually function? Poetical treatments tend to follow Ovid’s formulations, embedding Echo within the text and tasking readers with performing the multiplicity of voices through their own reading experience, whether silently or aloud. Performative genres such as spoken drama and opera introduce the challenge of capturing the very essence of the performance—by nature ephemeral and extra-textual—through written signs, be they words or musical notes.

An instructive example of the limitations of written records for texts intended to be performed—and a reminder that these kinds of texts only reach their full potential through performance—is provided by one of the intermezzi of the Rappresentatione di Santa Uliva (The Story of Saint Olive), a late Quattrocento sacred drama known through several printed playbooks from the second half of the sixteenth century.8 Unfortunately, the music for this intermezzo, which stages the story of Echo and Narcissus as an allegorical counterpoint to the romantic component of the story (in fact, a cautionary tale about the risks entailed by love), is lost, leaving us to wonder what the actual performance might have sounded like.9 However, an unusually detailed set of stage directions provides invaluable information about how the echo effect was achieved. While Narcissus’s words are fully written in ottava rima—the typical strophic form of Italian sacred dramas from the period—Echo’s replies were meant to be crafted ad-lib by the actors, based on various factors, including the actual pace of Narcissus’s speech. This resulted in a performance version of the text that only partially aligns with what we read in the playbook:

finalmente tutto lacrimoso [Narciso] si volga alla selva, e dica e sottoscritti versi in canto pietoso e interrotto, e la Ninfa a ogni fermata di parole replichi nel medesimo modo che egli ha fatto le ultime parole da lui dette, e massime certe come sarebbe ahimè, ahimè, e simili; e perché meglio intendiate, vi daremo l’esempio, e diremo s’el detto giovane dicessi questo verso: Sa quest’altier ch’io l’amo e facessi fermata dove dice: ch’io l’amo; la Ninfa dica: ch’io l’amo. Se dicesse tutto il verso, cioè: Sa quest’altier ch’io l’amo e ch’io l’adoro la Ninfa dica solamente con la medesima voce: l’adoro; e così replichi l’ultime parole del verso secondo il modo di chi lo canta.10

[finally, tearful, Narcissus should address the woods and deliver the following lines singing pitifully and with plenty of interruptions, and the nymph, at every pause in the words, should reply in the same manner as he had used for the last words he said, and especially those such as ahimè and similar ones. And so you may understand better we shall give you an example, thus: if the young man should say this line: This arrogant man knows that I love him, and he pauses where he says that I love him; the nymph should say: that I love him. If he says the whole line, that is: This arrogant man knows that I love him and adore the nymph should say only, in the same manner, adore. And thus she should repeat the last words of the line, according to the manner of the singer.]

In the case of the Echo and Narcissus intermezzo, the stage directions, in conjunction with the lyrics, are the primary sources that can offer us a better understanding of how the piece was intended to be performed. They also indicate that there was a certain level of variability in the performance itself, as it relied on the performers’ ability to synchronize with one another in order to create the most convincing echo effect. Interestingly, the explanation of the repetition mechanism draws from a line in Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso (32.19), in which the heroine Bradamante laments her beloved Ruggiero. Beyond the thematic affinity, what holds significance here is that the Rappresentazione demonstrates performative dynamics that treat strophic forms as flexible. The improvisatory nature of the exchange reaches its peak during the dramatic climax at the end of Narcissus’s speech, where words give way to bare exclamations, which Echo is meant to repeat: “Questi [versi] finiti, dica tre volte ad alta voce e adagio: Ahimè, ahimè, ahimè; e la Ninfa gli risponda” (After he has delivered these lines, he should say three times in a loud voice, slowly: Ahimè, ahimè, ahimè; and the nymph should answer him).11

In this case, if by ‘text’ one refers to the lyrics on the page, then there is no Echo in it. Yet, Echo is indeed in there. The encounter between Narcissus and Echo’s voices occurs outside the prosodic framework of the ottava rima, as the reiterated exclamation “Ahimè” is not accounted for within the strophic structure, but only documented in the stage directions. While this exemplifies the performance-centric approach observed in the paratext that accompanies the intermezzo, it also introduces a challenge that later sources will explicitly tackle: how to notate the presence of echoes in the text while also distinguishing them from the primary character’s speech.

3. Turning the Character into a Prop: Echo, Guarini, and Ingegneri

The question of how to capture echoes in writing becomes particularly tricky in cases where, unlike the intermezzo of Santa Uliva, the narrative presented on stage does not revolve around Echo’s own story. As confirmed by the fact that, in these cases, Echo is never listed among the dramatis personae of the plays she appears in, her status changes from that of a conventional character into an intangible (yet audible—and interactive) prop. In most plays and libretti, echoes are unlabeled in the text: they simply appear as repetitions of words or syllables at the end of a verse, either as the final segment of the verse itself, as in Guarini’s Il pastor fido (Figure 3), or as a verbal component added in the margin, as in Ottavio Rinuccini’s La Dafne (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Guarini, Il pastor fido (1590), fol. Bb[1]r.

Figure 4.

Rinuccini, La Dafne (Rinuccini 1600), fol. A2r.

However, there are cases in which echoes happen to be indicated as “Echo” (usually with a capital E) and referred to as a feminine entity, with a clear allusion to Ovid’s nymph (Figure 5), as, for instance, in Alessandro Striggio’s libretto for Claudio Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, to which I shall return momentarily.

Figure 5.

Striggio, La favola d’Orfeo (Striggio 1607), p. 30.

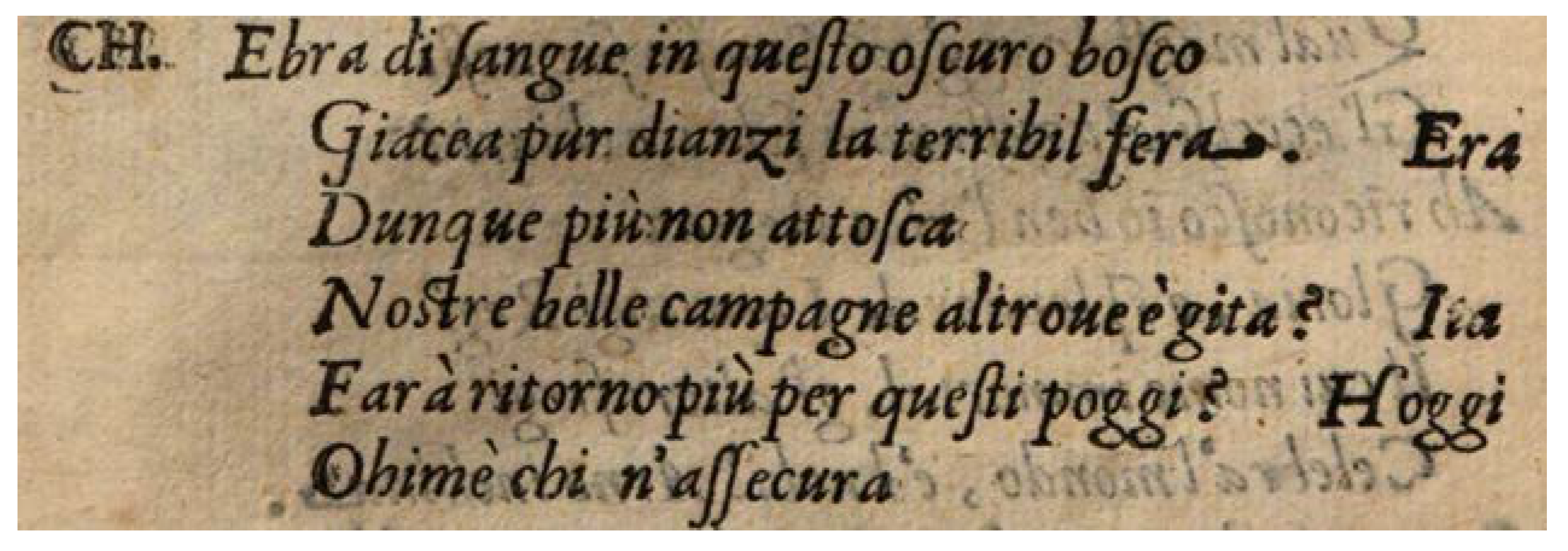

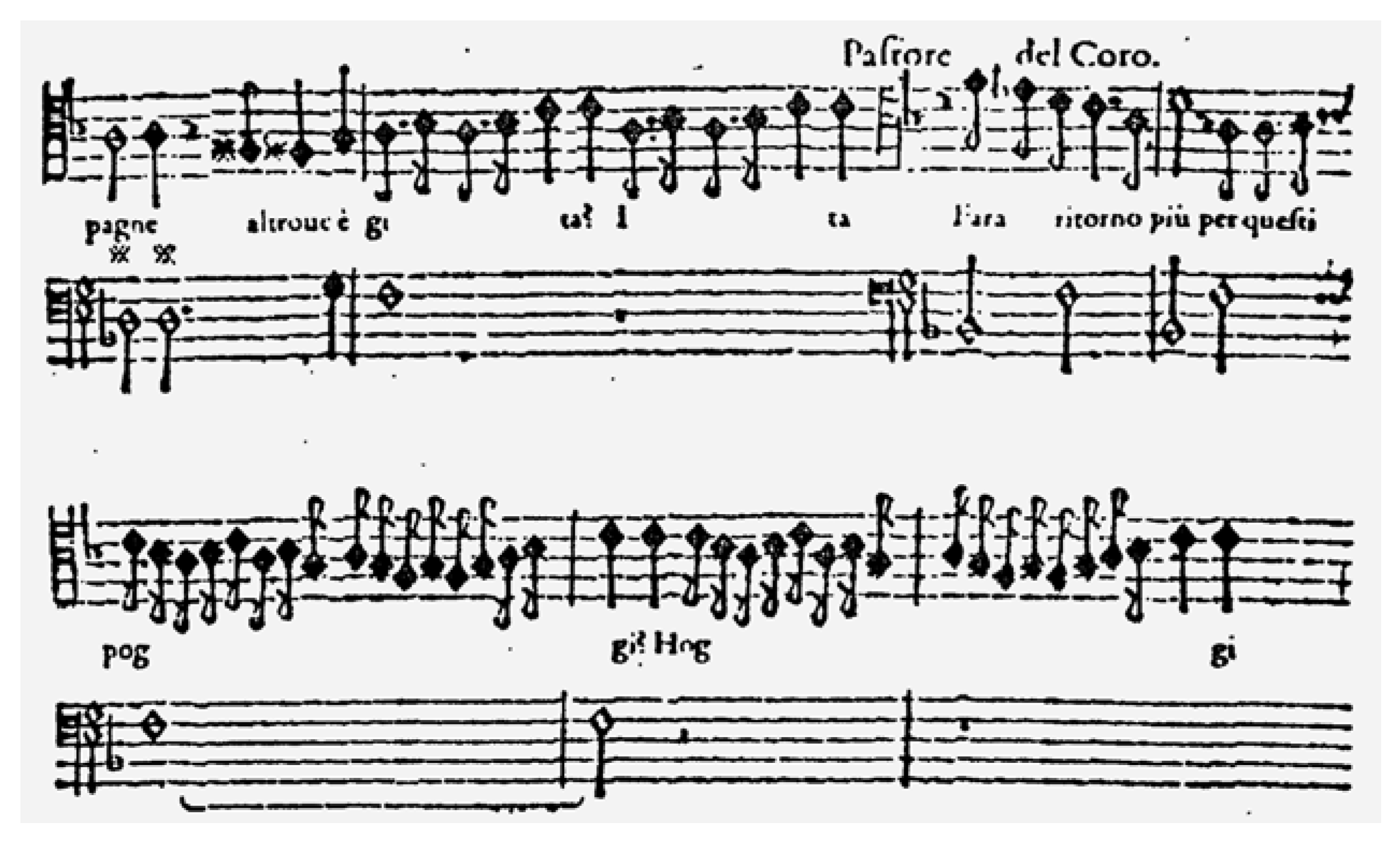

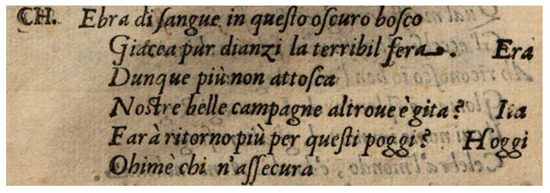

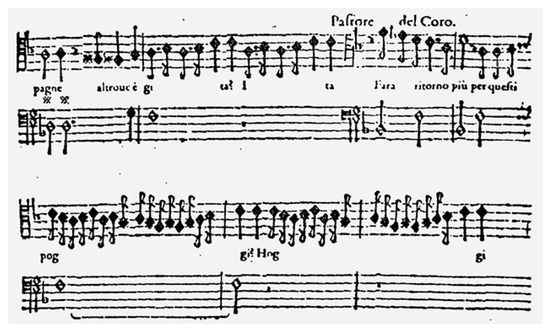

When it comes to scoring echoes, the situation is similar: sometimes, the echo effect is scored in total continuity with the speech of the character whose words are being echoed, with no specific indication that the repetition should be sung by another voice, as in Marco da Gagliano’s La Dafne, where the question “Farà ritorno più per questi poggi?” (Will the monster return to these hills?) is echoed by “Hoggi!” (today). Presented as an exact repetition, in which a tonal echo overlaps with the verbal one, the resulting effect is that of a veritable echo chamber (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Marco da Gagliano, La Dafne (Gagliano 1608), p. 6.

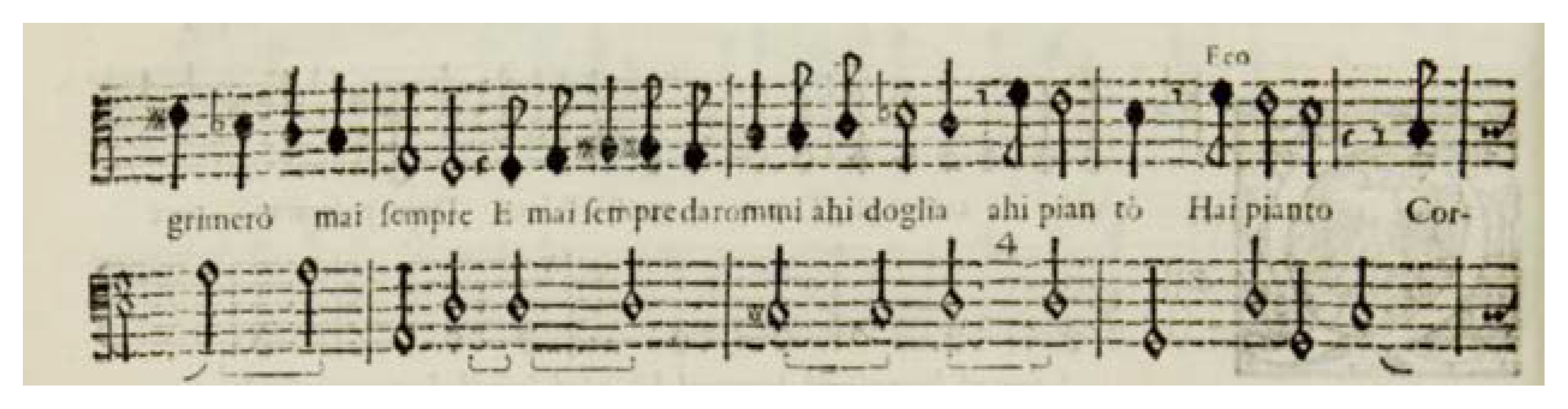

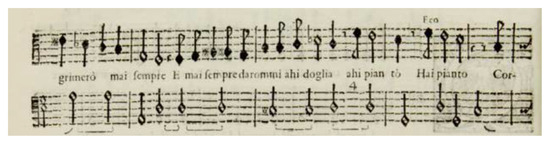

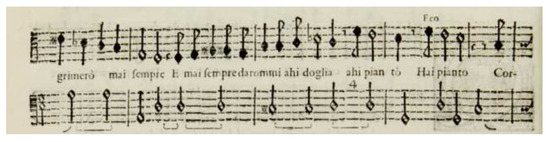

On other occasions, the fact that the repeated words are an echo is signaled by the name “Echo” appearing on the score, as Monteverdi does in the print of L’Orfeo (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Monteverdi, L’Orfeo (1609), p. 90.

While the absence of Echo’s name may imply that echoes are to be considered mere sound effects rather than characters with agency, the inclusion of the name explicitly relies on the shared knowledge of Ovid’s nymph’s story. Either way, the status of echoes in narratives other than Ovid’s myth remains ambiguous and closely tied to questions of poetic form, as evidenced by concurrent theoretical discussions like those surrounding Il pastor fido.

These discussions, which delve into both the prosodic intricacies of the echo effect and the question of its plausibility, originate from authors deeply engaged in the production of theatrical works; as such, they merge the rhetorical-poetical perspective with a more hands-on approach to performance practice. In the aftermath of the publication of Il pastor fido, a substantial debate unfolded across Italy and beyond, centering on the specific features of the pastoral genre in drama, its relationship with the pastoral tradition, and its position in relation to other forms of drama.12 Among the numerous works that were part of the debate, one is especially relevant to my discussion: the treatise Della poesia rappresentativa e del modo di rappresentare le favole sceniche (On Representative Poetry and the Manner of Representing Scenic Fables, 1598) by poet and playwright Angelo Ingegneri (1550–1613), one of the most comprehensive accounts of Renaissance drama, and one that gave particular emphasis to contemporary performance practices.13 Responding to Ingegneri and others, Guarini subsequently reissued Il pastor fido with an extensive set of annotations, which first appeared in the 1602 Venetian edition of the play. Since comprehensive surveys of the Pastor Fido debate have been offered elsewhere, I will concentrate on Guarini and Ingegneri’s discussions of Echo, which will establish a valuable conceptual framework for analysis of the example from Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo I take up later in this essay.

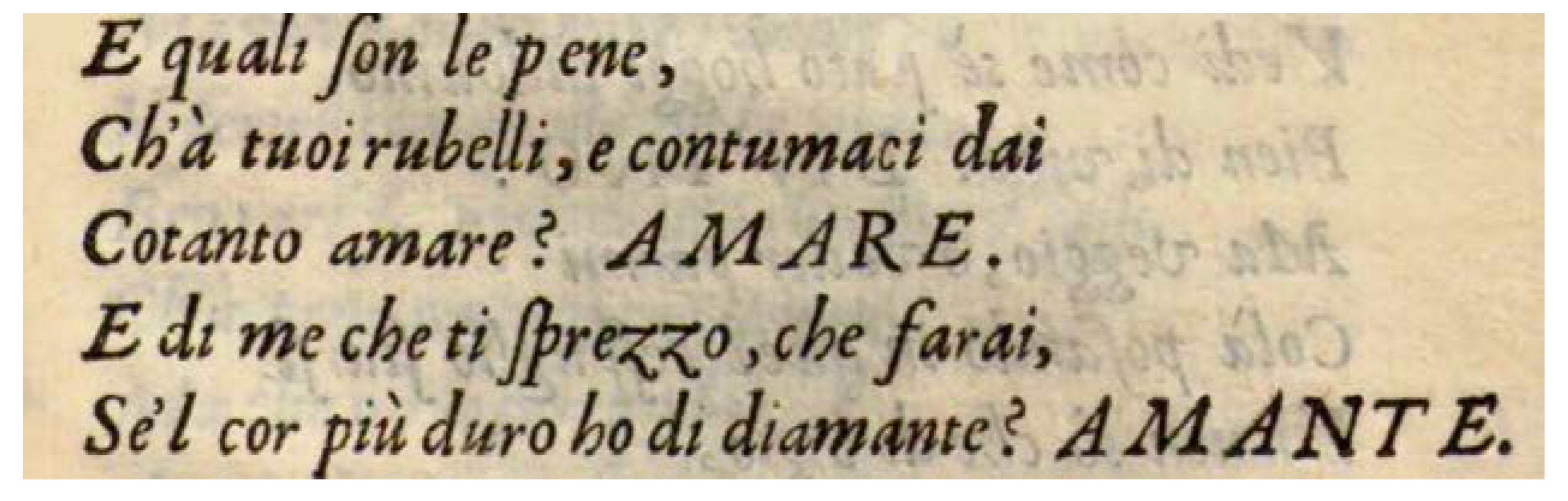

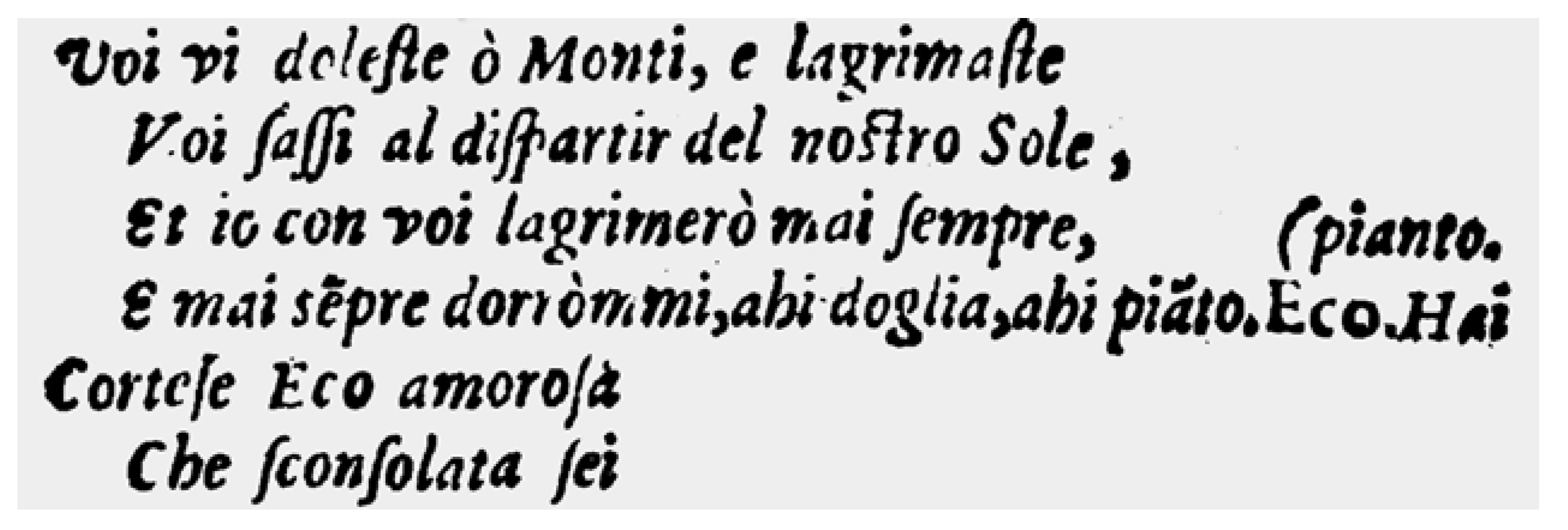

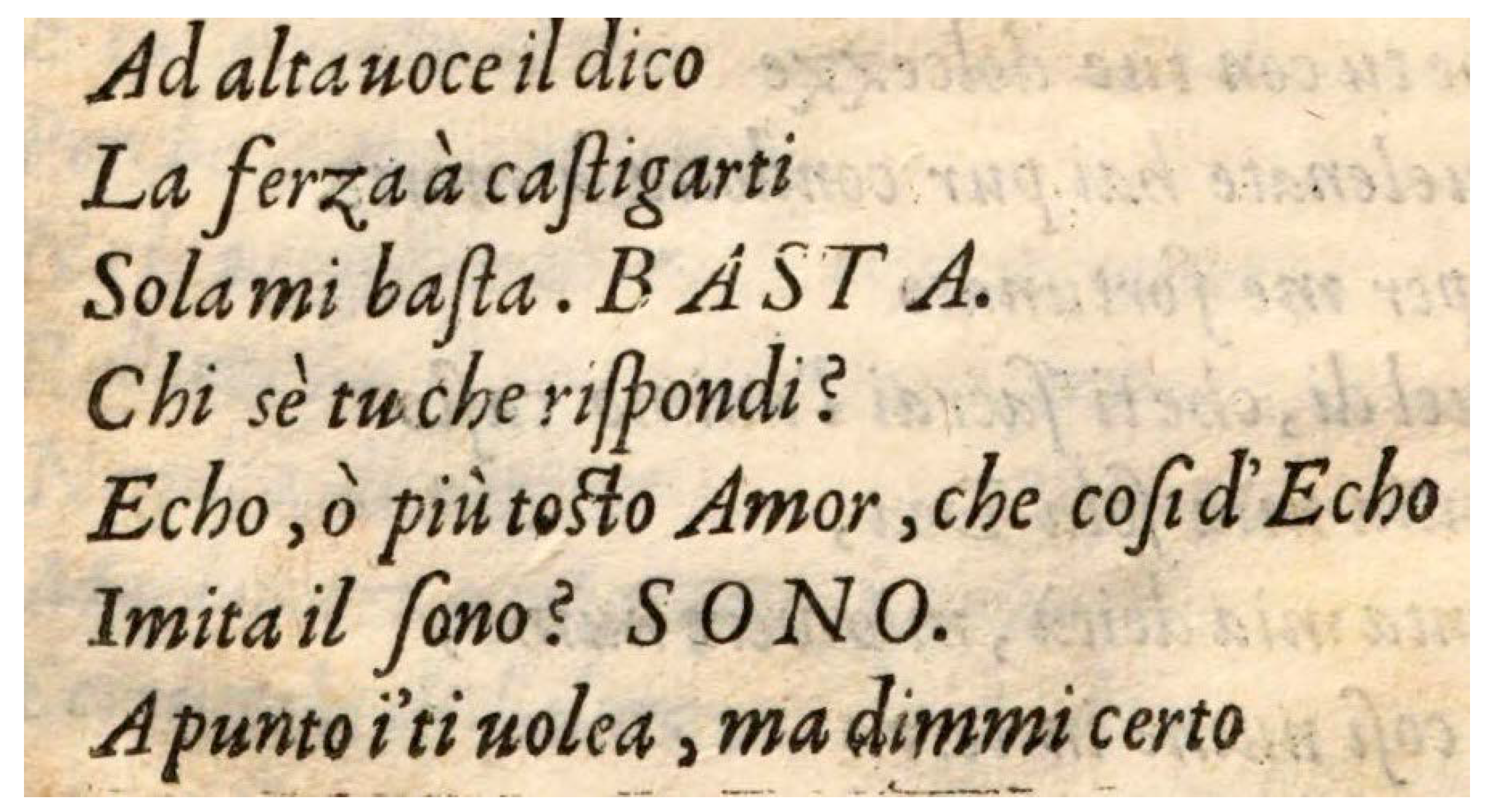

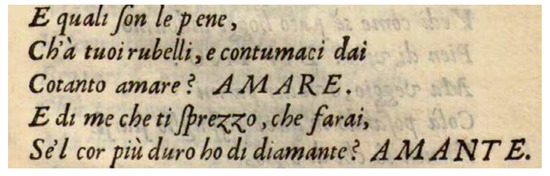

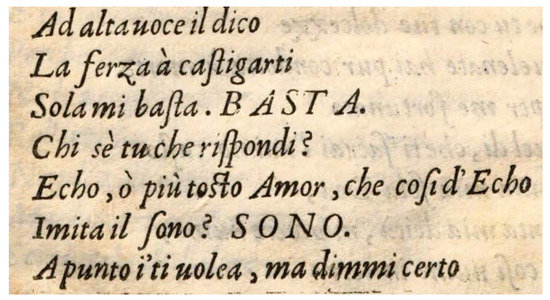

The text of Il pastor fido introduces a textual format distinct from what we observed in the Santa Uliva intermezzo. Guarini does not entrust Echo’s replies entirely to the actors’ discretion. Instead, the poet embeds Echo’s voice directly into the lyrics, underscoring the notion that, in textual terms, Echo’s voice is incorporated into the signs on the page and not simply left to improvisation. The paradoxical nature of Echo—being a disembodied voice that only manifests in response to another’s speech, yet also a textual presence to be transcribed—is vividly exemplified in Scene 8 of Act 4 in Il pastor fido. As recalled at the outset of this essay, when Silvio directs his reproach towards Venus and Love, addressing Cupid and raising his voice (“Ad alta volce il dico”, I say it aloud), he elicits Echo’s response, which he interprets as Love’s own rejoinder to his grievances. This sets off a characteristically frustrating conversation that ultimately leads nowhere. Following the Ovidian model, the echoes are concise (usually one or two syllables), intricately woven into the prosodic fabric of the verse, and imbued with meanings that deceptively suggest a dialogic trajectory:

Ad alta voce il dico:la ferza a gastigartisola mi basta.—Basta—.Chi se’ tu che rispondi?Eco, o più tosto Amor, che così d’Ecoimita il sono?—Sono—.A punto i’ ti volea; ma dimmi certoSe’ tu poi desso?—Esso—.14

[I say it aloud, | The whip is enough to punish you, | That alone suffices. Enough. | Who are you that answers? | Echo, or rather Love, who in this way, like Echo, | Mimics the sound? I am. | It’s you whom I was seeking, but tell me for certain, | Are you really he? It is.]

Echo (audible but invisible in performance) is made visible in the text, her words being printed in capital letters to distinguish them from those uttered by the main character (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Guarini, Il pastor fido (Venice: 1590), Act 4, Scene 8, f. [Aa4v].

The question of Echo’s status within the broader framework of the play, including her role within the narrative and among the interlocutors, was evidently a concern of the playwright himself. He explicitly addressed it in his 1602 annotations to the play, where the playwright advances a double interpretation of Echo. On one hand, as transmitted and retold by the poetic tradition originating in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Echo is the solitary mountain nymph who, reduced to mere voice, is fated to echo the words of others. On the other hand, in accordance with the views of natural philosophers like Aristotle (one might think of the Greek philosopher’s influential discussion of voice in the treatise On the Soul), an echo is a natural occurrence (“accidente del suono”) arising from the reflection of sound within a suitable space. Either way, Echo is not a voice per se, but the “image of a voice” (“immagine della voce”).15 Here, Guarini’s phrasing echoes Ovid’s own “imago vocis” (3.385), while also hinting at the contest of media that informs the artistic culture of early modernity and, more precisely, at the tension between different forms of artistic representation grounded in competing sensorial stimuli.

After establishing the two perspectives through which Echo can be understood (allegorical and scientific), Guarini proceeds with more precise instructions on how to incorporate echoes into poetry. His initial recommendation is that Echo’s responses should not be placed outside the poetic lines, but rather integrated within them (“non resti segnata fuori del margine”), as can be seen in Figure 8.16 According to Guarini, since poetry aims to mimic human speech through prosody, textual fragments located outside the prosodic structure would violate the fundamental rules of poetic language. In other words, if prosody is not respected, the text ceases to be poetry, and its author ceases to be a poet. On a different note, to those who argue that Echo should be considered an autonomous character, Guarini counters that Echo is intended to be nothing more than the reverberation of one’s voice—a reflected utterance without agency. Consequently, if one regards Echo as a natural phenomenon resulting from a specific spatial context, Echo’s inclusion in a play should always be justified by realistic staging. This may encompass characters raising their voices (as Silvio does) and/or the setting, whether it be a cave or a wooded area conducive to acoustic reverberations.

The question of Echo’s plausibility and the necessity to provide a justification for her presence is also central to Ingegneri’s discussion. In his 1598 treatise, he clarifies that echoes in drama are permissible only when they are entirely warranted by the circumstances—either a location naturally conducive to the echo effect or a specific manner of delivery, such as raising one’s voice, which could reasonably provoke an echo from the space nearby. In the absence of such conditions, Ingegneri contends, Echo’s presence can only be rationalized by attributing some form of agency to her. This entails the unacceptable result of transforming a natural phenomenon—the repercussion of sound in the air—into a dramatic character.17

Ingegneri’s ultra-rationalistic approach is further reinforced by a formal argument, leading him to a position quite distinct from Guarini’s. He asserts that Echo’s words should not be integrated into the regular prosodic structure; rather, they should come after the completion of a given verse (as seen in Figure 4). In other words, when it comes to writing, Ingegneri argues that these words should indeed be added in the margins of the page. If Echo’s words were to be included in the regular prosody, as Il pastor fido does, one would have to assume they were produced by a mind capable of completing a poetic line left unachieved by others. In this scenario, Echo would indeed possess (poetical) agency and thus warrant inclusion among the dramatis personae.

While arriving at different conclusions regarding the place of Echo in prosody, both Guarini and Ingegneri reject the idea of elevating a mere reverberation of the air to the status of a character, a point that speaks to preoccupations about the very notion of character that were key to the debates stemming from the reception of Aristotle’s Poetics.18 In fact, the tension between incorporating Echo’s allegedly disembodied presence in the body of the text and relegating their voice to the margins of it highlights the friction between embodiment and disembodiment that fuels any narrative involving echoes. By reducing echo to a distinctive acoustic effect, Guarini and Ingegneri highlight the adaptable nature of a trope whose dramatic function (although not coinciding with that of a regular character) is, as I will suggest in the final part of this essay, activated through performance.

4. Staging Echo in Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo

Echo’s uncertain status within and around the text becomes even more pronounced when we examine how echoes are realized on stage. Early operas, in this regard, offer extremely valuable readings, for the detailed nature of musical scoring, with nuances of delivery notated in microseconds, provides material that can assist in gaining a more detailed assessment of the performative nuances of the trope. Among the numerous operatic depictions of Echo, which range from Arion’s double echo in the 1589 Intermezzi della Pellegrina to Ottavio Rinuccini’s La Dafne, first set to music in Florence by Jacopo Peri and Jacopo Corsi in 1598, and later by Marco da Gagliano in Mantua in 1608, a particularly intriguing example can be found in Claudio Monteverdi’s influential L’Orfeo (Mantua, 1607), which—quite exceptionally—was published in score in 1609 (and reprinted in 1615).19 What renders L’Orfeo an especially fertile subject for examination is the availability of a substantial number of audio and video recordings of modern performances. Over time, these productions have approached the performative aspect of the work in various ways. Indeed, when scrutinized through the lens of performance practice, Orpheus’s encounter with Echo in Act 5 reveals some unexpected elements that challenge enduring assumptions about the trope itself, including those pertaining to the potentially gendered identity and sound of Echo’s voice.

While Ovid’s account emphasizes the semantic flexibility of Echo’s responses (she may alter the meaning of her interlocutor’s words, but not their verbal/acoustic form), the Latin poet does not provide extensive details about how Echo’s voice might be associated with a particular gender. Considering that Echo is a nymph, it is reasonable to expect her voice to be perceived as feminine. However, when her body dissolves, when the nymph, so to speak, transforms into the natural phenomenon of acoustic reverberation, is not it expected to replicate the sound that initially triggered it? If that is the case, when it comes to the reverberation of human voices, echo’s gender should mirror that of the voice that initiates it. Yet, as with all things vocal, the question of echo’s identity proves more complicated, as demonstrated by the issues it raises when textual sources are explored with an ear (and an eye) to performance.

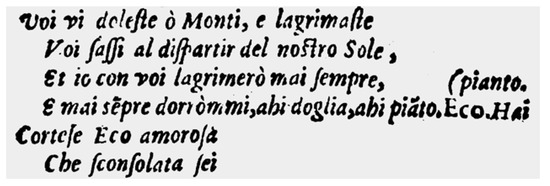

A case in point is Act 5 in Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, where Orpheus laments over Eurydice’s second death. Orpheus’s despair and loneliness are vividly depicted by the librettist, Alessandro Striggio, as he portrays Orpheus engaging in a frustrating conversation with Echo.20 Echo’s initial response occurs when Orpheus addresses the mountains and stones that wept with him upon learning of Eurydice’s first death:

Voi vi doleste, o monti, e lagrimastevoi, sassi, al dipartir del nostro sole,ed io con voi lagrimerò mai sempre,e mai sempre dorrommi, ahi doglia, ahi pianto! Eco: Hai pianto.21

[You grieved, O Mountains, and you cried, Rocks, when our Sun left us, And I will always weep with you And always will yield myself to grief, oh, I’m in pain, oh, I’m in tears! Echo: In tears.]

Echo employs a poetic device, characteristic of her since Ovid’s time, wherein her response alters the meaning of what was initially said. Orpheus’s exclamation “Ahi pianto!” (literally “oh, my tears!”) is transformed into a statement, “Hai pianto” (you have wept). However, similar to Ovid’s account, the full nuance of Echo’s reply is best apprehended when reading the written text, as the mere auditory experience in performance does not distinguish it significantly from Orpheus’s original expression. It is the tension between the ostensibly identical utterance and its shifting semantics that engenders the illusion of a dialogue, the subtleties of which may or may not be fully apprehended by the audience.

Orpheus identifies the voice that responds to him as that of “cortese Eco amorosa” (gentle, loving Echo), who replies to him two more times: “Non ho pianto però tanto che basti. Eco: Basti!” (I have not wept enough. Echo: Enough) and “Se gli occhi d’Argo avessi | e spandessero tutti un mar di pianto, | non fora il duol conforme a tanti guai. Eco: Ahi!” (If I had the eyes of Argus, | And they poured out a sea of tears, | Their grief would not match such woe. Echo: Oh).22 In both instances, the wordplay embedded in the replies straddles the grey area between oral delivery and written text. By repeating “basti”, Echo instructs Orpheus to cease his weeping. By echoing the term “guai” (meaning lamentations) with the exclamation “ahi” (a form of abbreviated lament), Echo creates a performative act that rhymes with the word conveying its meaning. While Orpheus appears to find some comfort in Echo’s sympathy (“S’hai del mio mal pietade, | Io ti ringrazio di tua benignitade”, If you feel for my pain, I thank you for your benevolence), frustration is imminent, as demonstrated by Orpheus’s unattainable desire to hear Echo repeat not only a few syllables of his speech, but his entire lament (“Ma mentr’io mi querelo, | Deh perchè mi rispondi | Sol con gli ultimi accenti? | Rendimi tutti integri i miei lamenti”, But while I do complain, | Why do you answer me | Only with my last words? | Give me back all of my laments).23 Unsurprisingly, Orpheus’s request renders Echo speechless.

As an instance of narrative contamination based on the encounter of two different stories, this scene prompts us to reflect on the role the trope of Echo is playing here—a question closely related to that of Echo’s identity. The capital E in Orpheus’s address (“cortese Eco amorosa”), together with the feminine ending of the adjective, suggests a precise reference to Ovid’s Echo, although one could argue that the capitalized initial is only visible on the written page. At the same time, Echo’s appearance at this juncture in the narrative evokes an eerie resonance with another character from within the opera: the messenger nymph, who, in Act 2 of L’Orfeo, announced Eurydice’s first death. It is quite intriguing how the messenger’s farewell, filled with guilt for the pain caused to Orpheus after announcing Eurydice’s death, parallels Echo’s own fate:

Ma io ch’in questa linguaho portato il coltelloc’ha svenata d’Orfeo l’anima amante,odïosa ai pastori ed a le ninfe,odïosa a me stessa, ove m’ascondo?Nottola infausta, il Solefuggirò sempre e in solitario specomenerò vita al mio dolor conforme.24

[But I who with these words | Have brought the knife | That has slain the loving soul of Orpheus, | Hateful to the Shepherds and to the Nymphs, | Hateful to myself, where may I hide? | Like an ill-omened bat, | I will forever flee the Sun, and in a lonely cavern | Will lead a life that matches my grief.]

For those familiar with the score of L’Orfeo, the idea that the messenger and Echo may share something in common is less far-fetched than it might initially seem. Indeed, the two scenes are not only parallel in terms of the characters’ destinies, but also in their language and tonal shape. In terms of the lyrics, Orpheus’s lament begins by echoing the messenger’s own words: specifically, the image of the heart pierced by grief (“Questi i campi di Tracia e questo è il loco | dove passommi il core | per l’amara novella il mio dolore”, These are the fields of Thrace, and this is the place | where my heart was pierced | by grief when I heard the bitter news) recalls the messenger’s phrasing (“Lassa, dunque debb’io, | mentre Orfeo con sue note il ciel consola, | con le parole mie passargli il core?”, Alas, then must I, | While Orpheus with his notes comforts heaven, | With my words pierce his heart?). Notably, there is also a repetition of an emotional keyword such as doglia (pain) in conjunction with the rhyming words canto (song) and pianto (crying): while the messenger asks the shepherds to cease from singing now that all joy is turned into pain (“Pastor, lasciate il canto, | ch’ogni nostra allegrezza in doglia è volta”, Shepherds, leave your singing, | For all our happiness is turned into pain), canto makes room for pianto in Orpheus’s painful words, “ahi doglia, ahi pianto”, with further repetitions of the latter across the monologue.25 When it comes to the tonal affinities between the messenger scene and Orpheus’s lament, both cases are characterized by a shift from G minor to A minor via an emotionally charged E flat harmony, which marks the psychological domain of grief.26

Similarly, looking at the modern performance tradition of L’Orfeo provides a valuable context for assessing the parallelism between the messenger and Echo. A non-exhaustive examination of productions of Monteverdi’s opera reveals that, differently from the first performance in Mantua, where the messenger was sung by a mezzo-soprano castrato and Echo by a tenor, the two characters happen to be assigned the same vocal register (i.e., soprano).27 However, in most productions, Echo’s three responses to Orpheus are given to a tenor, mirroring the protagonist’s own voice. Needless to say, both approaches to staging Echo’s voice can be justifiable in terms of dramaturgy. On one hand, having Echo sung by a woman allows for the resonance of Ovid’s nymph and the potential for an intra-textual connection with the messenger. On the other hand, employing a male voice for Echo shifts the focus towards the reflexive nature of the acoustic phenomenon, as well as the self-reflective dimension of the protagonist’s encounter with Echo. In this context, Orpheus’s engagement with Echo can also be interpreted as a means to summon the specter of Narcissus, whose influence persists in the reception of Orpheus well beyond Monteverdi (consider, for instance, Jean Cocteau’s hyper-narcissistic Orphée).28 As the poet-singer finds himself in the place of Narcissus, his vexing dialogue with Echo reveals a fundamental limitation—the protagonist’s inability to resist the allure of self-absorption.

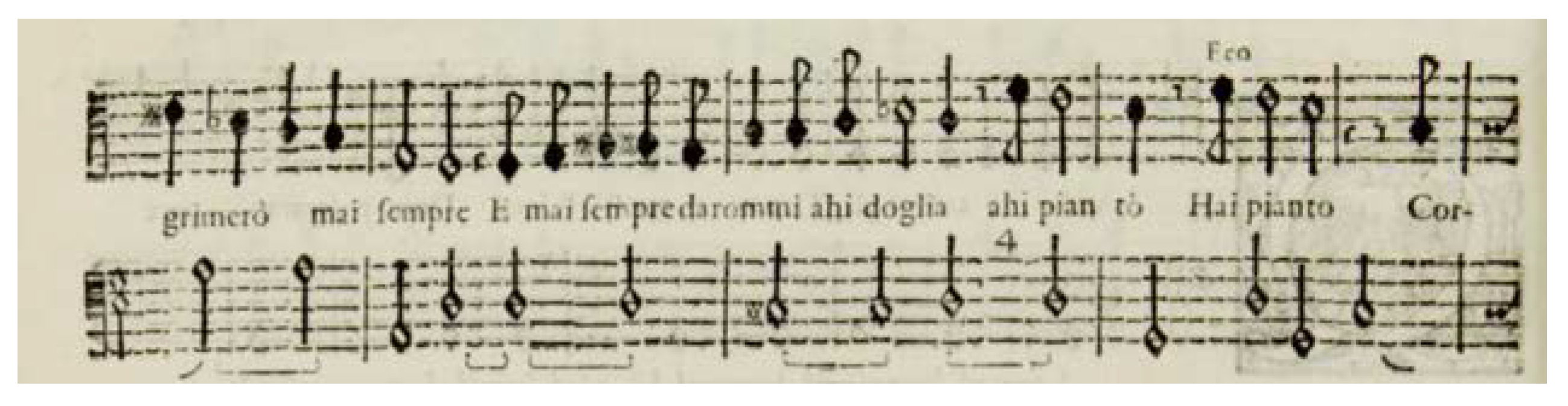

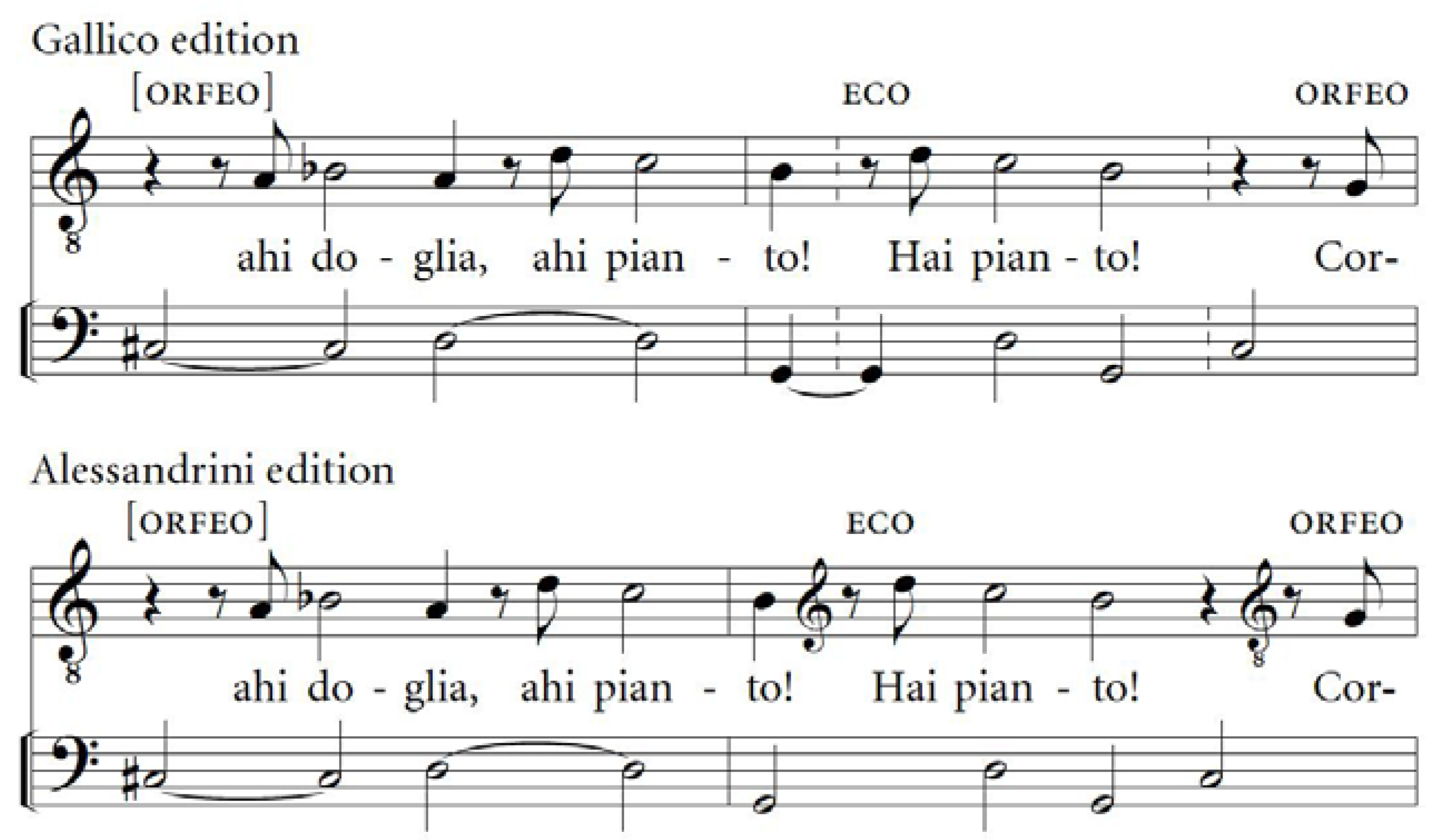

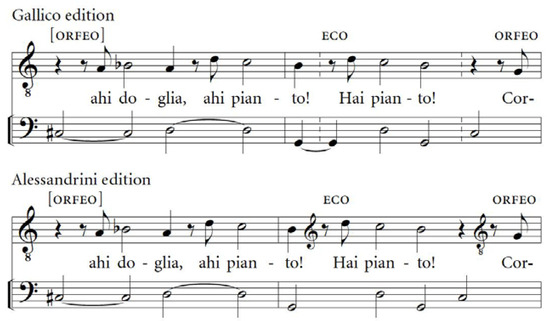

But how can the selection of a male or female voice for Echo be justified based on textual sources, editorial practices, and performative requirements? In terms of textual evidence, Echo’s voice in both the 1609 and 1615 printed scores of L’Orfeo appears to be conceived in the same vocal register as Orpheus’s (that is, a male voice): no clef change, same pitches (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Monteverdi, L’Orfeo (Venice: 1609), p. 90.

This would lead us to expect Orpheus and Echo to share a similar sound. However, a few discrepancies arise when we examine modern editions. The most straightforward way to edit Monteverdi’s score appears in Claudio Gallico’s edition of L’Orfeo, among others, where the voices of Echo and Orpheus share the same register.29 A different editorial solution has more recently been chosen by Rinaldo Alessandrini, who—with no explanation—has assigned Echo a higher register, perhaps to evoke the idea that Echo is supposed to be a nymph, hence a female voice, as suggested by Orpheus’s own words (“Eco amorosa”) (Figure 10).30

Figure 10.

Monteverdi, L’Orfeo (1609), p. 90, Echo’s first response according to Gallico (Monteverdi 2004), p. 105, and Alessandrini (Monteverdi 2012), p. 78 (my transcription).

Consequently, in the production of L’Orfeo directed by Bob Wilson and conducted by Alessandrini himself, Echo’s voice was portrayed as female.31

The crux here is not whether to advocate for an exclusively philological approach to the sources. In fact, it is widely acknowledged that early music notation allowed, and to some extent even necessitated, a certain degree of interpretative freedom (although one could argue that Monteverdi’s scrupulous attention to detail in the 1609 print, where both instrumentation and vocal parts were meticulously notated, suggests that the composer had fairly specific ideas in mind regarding how the score should sound).32 Instead, I want to emphasize that the question of Echo’s vocal identity, including her vocal range, is more productively addressed when one looks at the tension between what is found in the score and what the performance adds to (or reveals about) the score—a tension that, in the case of Echo includes not only the question of gender, but also that of her invisibility.

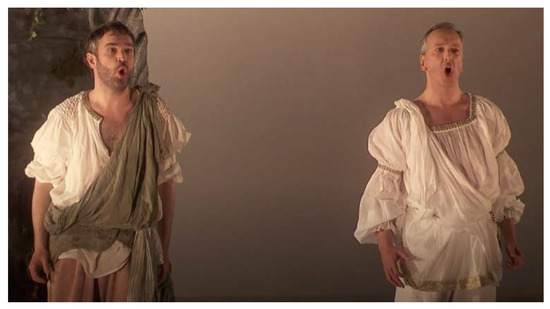

It is reasonable to assume that Striggio and Monteverdi did not intend for Echo to be physically present on stage—a notion widely accepted by most modern stage directors, who typically place Echo behind the scenes. Two notable exceptions are worth considering: Jean-Pierre Ponnelle’s historical production of L’Orfeo (Zürich, 1978), and Paul Agnew’s more recent staging of the opera with Les Arts Florissants (Caen, 2017), where Echo makes a tangible appearance on stage.33 In Ponnelle’s production, Echo’s part is sung by a cloaked woman, positioned behind Orpheus, with the head covered and the typical gesture of amplifying one’s voice with the palms around the mouth (the blurred effect due to the contrast between foreground and background in the video footage is particularly evocative, as it makes Echo—barely visible on the right side of the still image—even more elusive) (Figure 11).34

Figure 11.

Monteverdi, L’Orfeo, dir. J.P. Ponnelle (1978), Act 5.

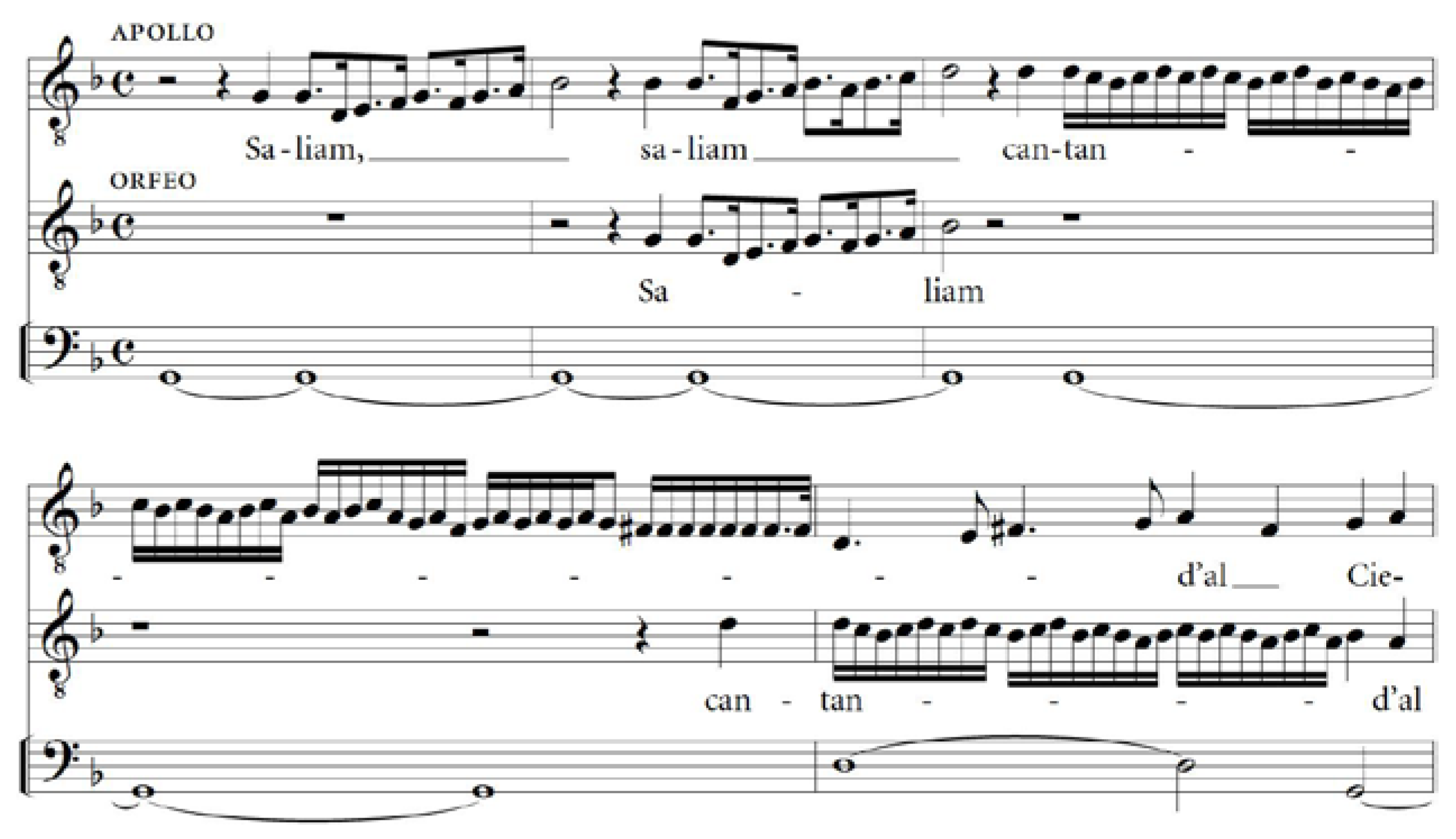

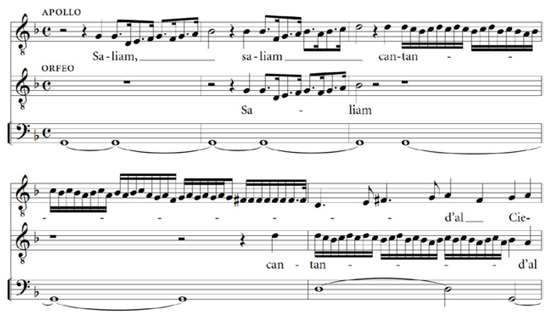

In Paul Agnew’s rendition, Echo’s physical presence takes on even greater significance. Not only is Echo—in line with Monteverdi’s original scoring—portrayed by a tenor (Agnew himself, who simultaneously holds the roles of stage director, music director, and singer), but that very tenor is the same one who, in the immediately following scene, without interruption, takes on the role of Apollo, who, as is known, appears at the end the opera to save Orpheus and lead him to the heavens (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Monteverdi, L’Orfeo, dir. Paul Agnew (2017), Act 5, Orpheus and Echo.

If, musically speaking, in the exchange between Orpheus and Echo, it is the latter who follows the lead of the former, the situation is completely reversed when Apollo enters. After warning Orpheus about the perils of becoming too attached to the things of the world, the god leads the way in a beautiful duet featuring flourished melismatic passages in which it is Orpheus who eventually echoes Apollo (Figure 13 and Figure 14).

Figure 13.

Monteverdi, L’Orfeo, dir. Paul Agnew (2017), Act 5, Orpheus and Apollo.

Figure 14.

Monteverdi, L’Orfeo (1609), pp. 95–96 (my transcription).

Undoubtedly, Agnew’s solution differs significantly from what Monteverdi and Striggio may have originally envisioned. It suggests that echoes in L’Orfeo are not merely musical effects aimed at surprising the audience. Indeed, by combining the score’s musical language with powerful visual concepts—one notably impactful aspect being the use of silhouetted figures against a colored backdrop—the director demonstrates that echoes contribute to the creation of a space where self-reflection plays a pivotal role in the dramatic progression of the action. Incidentally, the same visual technique is adopted for the double instrumental echoes that accompany Orpheus’s prayer to Charon, “Possente spirto”, at the beginning of Act 3, where the echo effect is primarily meant to evoke the vastness of the underworld (Figure 15).35

Figure 15.

Monteverdi, L’Orfeo, dir. Paul Agnew (2017), Act 3, “Possente spirto”.

By making echoes visible on stage, and, particularly in the case of Act 5, visible as a man—almost a visual doppelgänger of Orpheus—Agnew challenges Echo’s original identity and literally embodies the nymph’s transformation into a metamorphic voice (gender-less or, better said, gender fluid) that reiterates what others say, including at pitch.

5. Conclusions

Interestingly enough, the sets that encircle Orfeo throughout Paul Agnew’s production—a few rocks evoking the diverse places where the action unfolds—bear a striking resemblance to Echo’s mountainous crevice depicted in the 1602 illustration of Il pastor fido, which was discussed at the beginning of this essay. While serving different functions, these attempts to visualize the environments where echoes resound encapsulate the pervasiveness and adaptability of the trope. At the same time, the examples gathered here suggest that the questions raised by today’s editorial and performance practices resonate with early modern concerns about the very features of an acoustic phenomenon that exposes the permeability of textuality and performance. Far from exhaustive, my selection of case studies has also shown that Echo lives both in the text and outside of it, thus hanging in the balance between the materiality of the written page and the apparent immateriality of her history in performance.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Shane Butler, Davide Daolmi, Roseen Giles, Jessica Goethals, Wendy Heller, Anne MacNeil, and Kate van Orden, with whom I have discussed the content of this article, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their useful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares there is no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Ovid, Metamorphoses 3.385 (“perstat et alternae deceptus imagine vocis”, my emphasis). |

| 2 | (Guarini 1602, fol. Q[1]v). |

| 3 | For an overview of the iconographic models canonized during the sixteenth century in the illustrated editions of epic poems, see (Bolzoni 2017). |

| 4 | (Yerkes 2021, pp. 163–79; Van der Miesen 2020). For a characteristic, although idiosyncratic early modern treatment of echoes as acoustic phenomena in both natural landscapes and architecture, one may refer to Athanasius Kircher’s discussion of “magia phonocamptica” in both his Musurgia Universalis, especially the “Phonocamptica sive perfecta de Echo” section of book 9, and his Phonurgia Universalis; see (Pangrazi 2009, p. 12). |

| 5 | (Butler 2015). |

| 6 | For a provocative discussion of Echo’s textual status in poetry and the myth’s relevance to vocal expression, see (Butler 2019). |

| 7 | (Hollander 1981; Sternfeld 1993, pp. 197–226); for a focus on the presence of Echo in the musical tradition, see (Russano Hanning 2013, pp. 193–218). |

| 8 | (D’Ancona 1863, pp. 33–36). For an overview of this work, see (D’Ancona 1863, pp. VII–XLIII; Sternfeld 1993, pp. 66–67, 217–18); on the specific function of the intermezzi in the Rappresentazione di Santa Uliva, see (Ventrone 1984). |

| 9 | The allegorical function of the intermezzo vis à vis the main narrative is briefly outlined in (D’Ancona 1863, p. XLII). |

| 10 | (D’Ancona 1863, p. 34). English translation adapted from (Sternfeld 1993, p. 218). |

| 11 | (D’Ancona 1863, p. 34). English translation adapted from (Sternfeld 1993, p. 218). |

| 12 | See the introduction to (Guarini 1999); and (Clubb 1989, pp. 93–187; Henke 1997; Sampson 2006). On the relevance of the pastoral tradition to concurrent developments in music, see (Gerbino 2009; Tomlinson 1987, pp. 114–47; Carter 1992, pp. 152–53; Schneider 2010). |

| 13 | (Ingegneri 1598); here I am using the modern edition (Ingegneri 1989). |

| 14 | (Guarini 1999, 4.8, pp. 218–19). |

| 15 | (Guarini 1602, p. 322). For Aristotle’s discussion of echoes as part of the philosopher’s reflection on the physio-psychological dimension of vocal expression, see Aristotle, On the Soul 2.8. |

| 16 | (Guarini 1602, p. 322). |

| 17 | (Ingegneri 1989, pp. 18–20). |

| 18 | On the question of character in Renaissance drama, a topic that was key to concurrent debates stemming from the reception of Aristotle’s Poetics, see (Reiss 1999, pp. 229–47). |

| 19 | (Monteverdi 1609, 1615). |

| 20 | For subtle readings of the echo scene in Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, though raising different questions from those addressed here, see (Chua 2004; Calcagno 2012, pp. 12–13, 65–68). |

| 21 | (Striggio 1607). Here I am using the modern edition (Striggio 1997, pp. 21–47: 44). |

| 22 | (Striggio 1997, p. 44). |

| 23 | (Striggio 1997, p. 45). |

| 24 | (Striggio 1997, p. 33). |

| 25 | (Striggio 1997, pp. 31, 44). |

| 26 | (Whenham 1986, p. 74). |

| 27 | For the distribution of roles at the 1607 premiere of L’Orfeo, see (Fenlon 1986, pp. 12–16). Modern productions in which Echo is sung by a female singer include the historical one directed by Jean-Pierre Ponnelle (Zürich Opernhaus 1978); the 2009 production directed by Bob Wilson (La Scala); and, most recently, Jens-Daniel Herzog’s staging of 2020 (Staastheater Nürnberg). |

| 28 | (Butler 2014, pp. 185–200); see also (Winkler 2020). |

| 29 | (Monteverdi 2004, p. 105). |

| 30 | (Monteverdi 2012, p. 78). |

| 31 | Monteverdi, L’Orfeo, dir. Bob Wilson; cond. Rinaldo Alessandrini (Milan: Teatro alla Scala 2011, rec. 2009). |

| 32 | (Glover 1986, pp. 138–55; Steinheuer 2007, pp. 119–40). |

| 33 | Monteverdi, L’Orfeo, dir. Jean-Pierre Ponnelle; cond. Nikolaus Harnoncourt (Zürich: Opernhaus 1978); and L’Orfeo, dir. and cond. Paul Agnew (Caen, Théâtre de Caen, 2017). |

| 34 | The iconography of the palms around the mouth is found in depictions of Echo: e.g., Alexandre Cabanel, Echo [1874], The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/435829 accessed on 5 December 2023. |

| 35 | On the function of instrumental echoes in the “Possente spirto” scene, see (Chua 2004, pp. 575–76). |

References

- Agnew, Paul, dir. 2017. Claudio Monteverdi. L’Orfeo (production of Théâtre de Caen). Arles: Harmonia Mundi. [Google Scholar]

- Bolzoni, Lina, ed. 2017. Galassia Ariosto. Rome: Donzelli. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Shane. 2014. Beyond Narcissus. In Synaesthesia and the Ancient Senses. Edited by Shane Butler and Alex Purves. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Shane. 2015. The Ancient Phonograph. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Shane. 2019. Is the Voice a Myth? A Rereading of Ovid. In The Voice as Something More: Essays toward Materiality. Edited by Martha Feldman and Judith T. Zeitlin. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 171–87. [Google Scholar]

- Calcagno, Mauro. 2012. From Madrigal to Opera: Monteverdi’s Staging of the Self. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Tim. 1992. Music in Late Renaissance & Early Baroque Italy. London: B. T. Batsford. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, Daniel. 2004. Untimely Reflections on Operatic Echoes: How Sound Travels in Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo and Beethoven’s Fidelio with a Short Instrumental Interlude. Opera Quarterly 21: 573–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clubb, Louise George. 1989. Italian Drama in Shakespeare’s Time. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ancona, Alessandro, ed. 1863. La Rappresentazione di Santa Uliva. Pisa: Fratelli Nistri. [Google Scholar]

- Fenlon, Iain. 1986. The Mantuan Orfeo. In Claudio Monteverdi, Orfeo. Edited by John Whenham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gagliano, Marco da. 1608. La Dafne. Florence: Cristofano Marescotti. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbino, Giuseppe. 2009. Music and the myth of Arcadia in Renaissance Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glover, Jane. 1986. Solving the musical problems. In Claudio Monteverdi, Orfeo. Edited by John Whenham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 138–55. [Google Scholar]

- Guarini, Giovan Battista. 1590. Il pastor fido. Venice: Giovan Battista Bonfadino. [Google Scholar]

- Guarini, Giovan Battista. 1602. Il pastor fido. Venice: Giovan Battista Ciotti. [Google Scholar]

- Guarini, Giovan Battista. 1999. Il pastor fido. Edited by Guido Baldassarri and Elisabetta Selmi. Venice: Marsilio. [Google Scholar]

- Henke, Robert. 1997. Pastoral Transformations: Italian Tragicomedy and Shakespeare’s Late Plays. Newark: University of Delaware Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander, John. 1981. The Figure of Echo: A Mode of Allusion in Milton and After. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ingegneri, Angelo. 1598. Della poesia rappresentativa e del modo di rappresentare le favole sceniche. Ferrara: Vittorio Baldini. [Google Scholar]

- Ingegneri, Angelo. 1989. Della poesia rappresentativa e del modo di rappresentare le favole sceniche. Edited by Maria Luisa Doglio. Ferrara: Panini. [Google Scholar]

- Monteverdi, Claudio. 1609. L’Orfeo. Favola in Musica. Venice: Ricciardo Amadino. [Google Scholar]

- Monteverdi, Claudio. 1615. L’Orfeo. Favola in Musica. Venice: Ricciardo Amadino. [Google Scholar]

- Monteverdi, Claudio. 2004. L’Orfeo. Edited by Claudio Gallico. London and New York: Eulenburg. [Google Scholar]

- Monteverdi, Claudio. 2012. L’Orfeo. Edited by Rinaldo Alessandrini. Kassel: Bärenreiter. [Google Scholar]

- Pangrazi, Tiziana. 2009. La Musurgia Universalis di Athanasius Kircher: Contenuti, fonti, terminologia. Florence: Leo S. Olschki. [Google Scholar]

- Ponnelle, Jean-Pierre, dir. 1978. Claudio Monteverdi. L’Orfeo (production of Zürich Opernhaus). Berlin: Deutsche Grammophon. [Google Scholar]

- Reiss, Timothy J. 1999. Renaissance theatre and the theory of tragedy. In The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism. Volume 3: The Renaissance. Edited by Glyn P. Norton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 229–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rinuccini, Ottavio. 1600. La Dafne. Florence: Giorgio Marescotti. [Google Scholar]

- Russano Hanning, Barbara. 2013. Powerless Spirit. Echo on the Musical Stage of the Late Renaissance. In Word, Image, and Song. Vol. I: Essays on Early Modern Italy. Edited by Rebecca Cypess, Beth Glixon and Nathan Link. Rochester: Boydell and Brewer, pp. 193–218. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, Lisa. 2006. Pastoral Drama in Early Modern Italy: The Making of a New Genre. Oxford: Legenda. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Federico. 2010. Pastoral Drama and Healing in Early Modern Italy. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Steinheuer, Joachim. 2007. Orfeo (1607). In The Cambridge Companion to Monteverdi. Edited by John Whenham and Richard Wistreich. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 119–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sternfeld, Frederick W. 1993. The Birth of Opera. Oxford: Clarendon. [Google Scholar]

- Striggio, Alessandro. 1607. La favola d’Orfeo. Mantua: Francesco Osanna. [Google Scholar]

- Striggio, Alessandro. 1997. La Favola d’Orfeo. In Libretti d’opera italiani dal Seicento al Novecento. Edited by Giovanna Gronda and Paolo Fabbri. Milan: Mondadori, pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, Gary. 1987. Monteverdi and the End of the Renaissance. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Miesen, Leendert. 2020. Studying the echo in the early modern period: Between the academy and the natural world. Sound Studies 6: 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventrone, Paola. 1984. “Inframessa” e “intermedio” nel teatro del Cinquecento: L’esempio della “Rappresentazione di Santa Uliva”. Quaderni di Teatro 7: 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Whenham, John, ed. 1986. Five acts: One action. In Claudio Monteverdi, Orfeo. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 42–77. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, Martin M. 2020. Ovid on Screen: A Montage of Attractions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yerkes, Carolyn. 2021. The Heptaphonon and the Architecture of Echoes. In Material World: The Intersection of Art, Science, and Nature in Ancient Literature and Its Renaissance Reception. Edited by Guy Hedren. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 163–79. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).