Petrified Beholders: The Interactive Materiality of Baldassarre Peruzzi’s Perseus and Medusa

Abstract

1. Introduction

And what is of stupendous marvel [at the villa Chigi] is a loggia that may be seen over the garden, painted by Baldassarre with scenes of the Medusa turning men into stone, such that nothing more beautiful can be imagined; and then there is Perseus cutting off her head, with many other scenes in the spandrels of that vaulting, while the ornamentation, drawn in perspective, simulated [contrafatto] in color and in stucco, is so natural and lifelike, that even to excellent craftsmen it appears to be in relief. And I remember that when I took the cavalier Titian, a most excellent and honored painter, to see that work, he would by no means believe that it was painted until he had changed his point of view [mutando veduta], when he was struck with amazement.2

2. Interactive Materiality

3. Iconography of Peruzzi’s Vault Fresco

4. The Petrified Beholder

Love, you see perfectly well that this ladycares nothing for your power at any time,though you be accustomed to lord it over other ladies:and since she has been aware of being my ladybecause of your light that shines in my face,she has made herself Lady Cruelty,so that she does not seem to have the heart of a womanbut of whatever beast keeps its love coldest:for in the warm weather and in the coldshe seems to me exactly like a ladycarved from some lovely precious stoneby the hand of some master carver of stone

And I, who am constant (even more than a stone)in obeying you, for the beauty of a lady,I carry hidden away the wound from that stonewith which you struck me as if I had been a stonethat had caused you pain for a long time,so that the blow reached my heart, where I have turned to stone.And never was there found any precious stonethat from the brightness of the sun or its own lighthad so much virtue or lightthat it could help me against this stone,that she not lead me with her coldnessto a place where I will be dead and cold.

Lord, you know that in the freezing coldwater becomes crystalline stoneunder the mountain wind where the great cold is,and the air always turns into the coldelement there, so that water is queenthere, because of the cold.Just so, before her expression that is all cold,my blood freezes over always, in all weather,and the care that so shortens my time for meturns everything into fluid coldthat issues from me through the lightswhere her pitiless light came in. (…)

Amor, tu vedi ben che questa donnala tua vertù non cura in alcun tempoche suol de l’altre belle farsi donna;e poi s’accorse ch’ell’era mia donnaper lo tuo raggio ch’al volto mi luce,d’ogne crudelità si fece donna;sì che non par ch’ell’abbia cor di donnama di qual fiera l’ha d’amor più freddo;ché per lo tempo caldo e per lo freddomi fa sembiante pur come una donnache fosse fatta d’una bella petraper man di quei che me’ intagliasse in petra.

E io, che son costante più che petrain ubidirti per bieltà di donna,porto nascoso il colpo de la petra,con la qual tu mi desti come a petrache t’avesse innoiato lungo tempo,tal che m’andò al core ov’io son petra.E mai non si scoperse alcuna petrao da splendor di sole o da sua luce,che tanta avesse né vertù né luceche mi potesse atar da questa petra,sì ch’ella non mi meni col suo freddocolà dov’io sarò di morte freddo.

Segnor, tu sai che per algente freddol’acqua diventa cristallina petralà sotto tramontana ov’è il gran freddoe l’aere sempre in elemento freddovi si converte, sì che l’acqua è donnain quella parte per cagion del freddo:così dinanzi dal sembiante freddomi ghiaccia sopra il sangue d’ogne tempo,e quel pensiero che m’accorcia il tempomi si converte tutto in corpo freddo,che m’esce poi per mezzo de la lucelà ond’entrò la dispietata luce. (…)36

That mortal enemy of naturewho dared to hurt all and the gods several timesis here converted to marble by herwith a sweet gaze that rages souls:One day she decided to hurt without carewith those ardent Medusan gazesand those high mountains, which because of hermen are transformed into hard stone.Oh how love has varied its stylehere it lies cold, and there was such fierce ardor,there was a light spirit, now heavy and vile.But such an example terrifies everyoneand there is never anyone so finewho does not presume to be superior.

Quel nimico mortal de la naturaChe ardí ferir piú volte omni e deiIn marmo è qui converso da costei,Che col dolce mirar gli animi fura,Ferir la volse un dì senza aver curaA quelli ardenti sguardi medusei,Et a questi alti monti, che per leid’omini son conversi in pietra dura.O quanto amore ha variato stilequi freddo iace, e fu sì fiero ardore,fu lieve spirito, or ponderosa e vile.Ma un tale exempio a ognun metta terrorené sia già mai nissun tanto sottileche non presume aver superiore.39

I have come to the point on the wheelwhere the horizon gives birth at sunset to the twinned heaven,and the star of love is kept from usby the sun’s ray that straddles her so transverselythat she is veiled; and that planetthat strengthens the frost shows itself to us entirely,along the great arcwhere each of the seven casts little shadow:and yet my mind casts offnot one of the thoughts of love that burden me,mind harder than stone to hold fast an image of stone. (…)

Io son venuto al punto de la rotache l’orizzonte, quando il sol si corca,ci partorisce il geminato cielo,e la stella d’amor ci sta remotaper lo raggio lucente che la ‘nforcasì di traverso, che le si fa velo;e quel pianeta che conforta il gelosi mostra tutto a noi per lo grand’arconel qual ciascun di sette fa poca ombra:e però non disgombraun sol penser d’amore, ond’io son carco,la mente mia, ch’è più dura che petrain tener forte imagine di petra. (…)40

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | On the Villa Farnesina and its notorious patron, see (Hermanin 1927; Frommel 1961; Coffin 1979; Frommel 2003; Rowland 1986, 2005; Turner 2022; Barbieri and Zuccari 2023). |

| 2 | (Vasari 1976), IV: 318. “E quello che è di stupenda maraviglia, vi si vede una loggia in sul giardino dipinta da Baldassarre con le storie di Medusa quando ella converte gl’uomini in sasso, che non può immaginarsi più bella, et appresso quando Perseo le taglia la testa, con molte altre storie né peducci di quella volta: e l’ornamento tirato in prospettiva di stucchi e colori contraffatti è tanto naturale e vivo, che anco agl’artefici eccellenti pare di rilievo. E mi ricorda che menando il cavaliere Tiziano, pittore eccellentissimo et onorato, a vedere quella opera, egli per niun modo voleva credere che quella fusse pittura: per che, mutato veduta, ne rimase maravigliato.” Unless otherwise noted, all English translations hereafter are mine. |

| 3 | (Pliny 1855), XXXV: 36. According to Pliny, Parrhasius “entered into a pictorial contest with Zeuxis, who represented some grapes, painted so naturally that the birds flew towards the spot where the picture was exhibited. Parrhasius, on the other hand, exhibited a curtain, drawn with such singular truthfulness, that Zeuxis, elated with the judgment which had been passed upon his work by the birds, haughtily demanded that the curtain should be drawn aside to let the picture be seen. Upon finding his mistake, with a great degree of ingenuous candor he admitted that he had been surpassed, for that whereas he himself had only deceived the birds, Parrhasius had deceived him, an artist.” Translation by John Bostock. |

| 4 | Leonard Barkan has suggested the notion of mutability as one of the main points of appeal of Ovid for Renaissance readers. (Barkan 1986), p. 172. |

| 5 | See (Holly 2013), pp. 15–17. |

| 6 | See (Holly 2013), p. 15. |

| 7 | See (Holly 2013), pp. 15–16. |

| 8 | On how the material turn overhauled art historical scholarship, see (Athanassoglou-Kallmyer 2019), pp. 6–7. |

| 9 | See for instance the work by Pamela Smith and her Making and Knowing Project collaborative research team. www.makingandknowning.org, accessed on 1 September 2023. See also (Cook et al. 2014; Anderson et al. 2015). |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

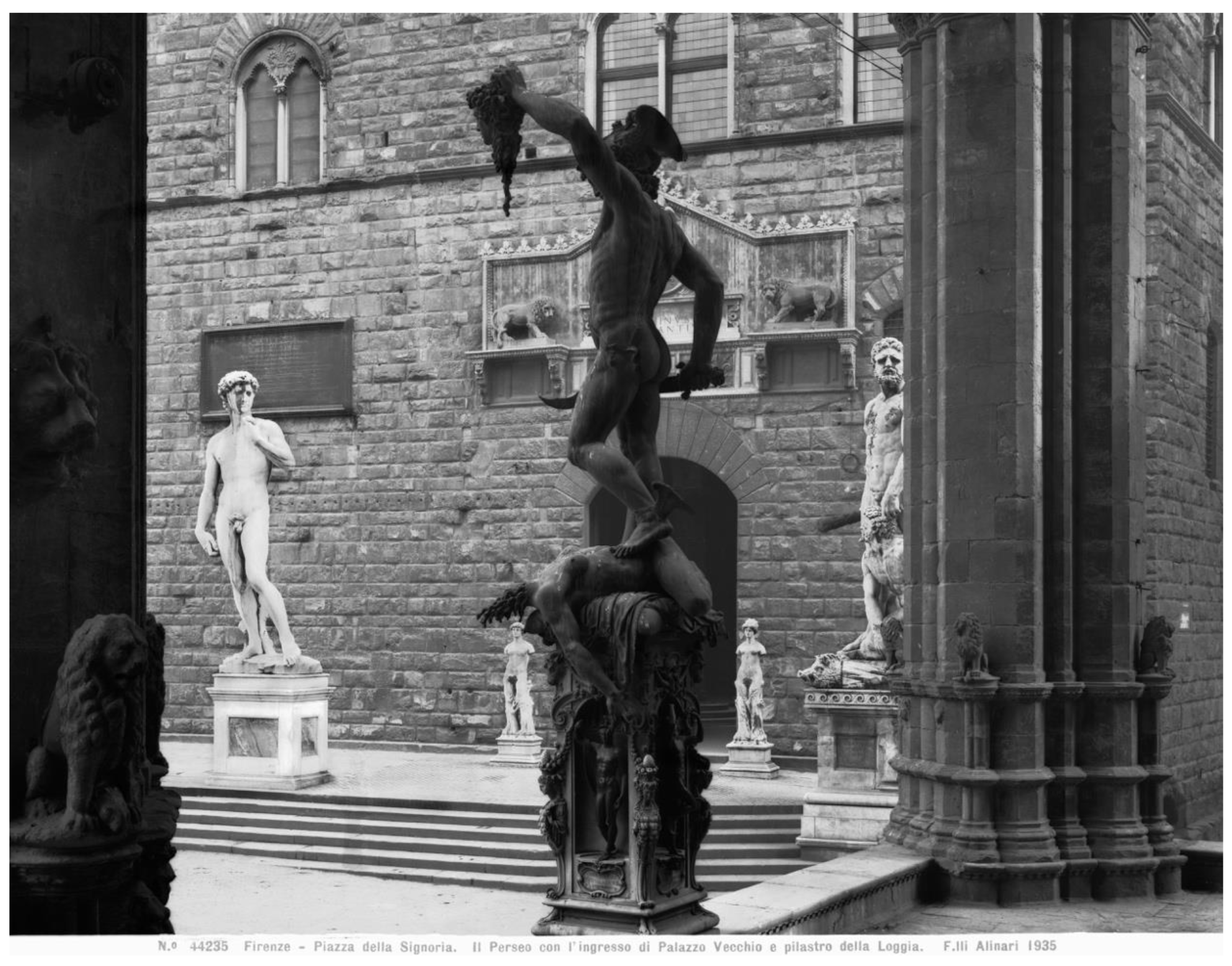

| 13 | (Campbell and Cole 2012), pp. 480–81. See also (Weil Grarris 1983; Gardner Coates 2000; Corretti 2015; Cieri Via 2021). |

| 14 | (Shearman 1992), pp. 44–58. As Shearman noted, Renaissance art was often “transitive” in this way, just as a transitive verb requires an object. |

| 15 | (Cellini 2002), pp. 30–31. Cellini mentions his conversations with Peruzzi in his Discorso dell’architettura (1776), a work initially written to be included in his Trattati dell’oreficeria e della scultura (1568). On the popularity of Perseus and Medusa as a subject matter in Renaissance art, see (Cieri Via 2021; van Eck 2016). |

| 16 | (Cole 2010). On iconological approaches to artistic materials, see also (Gramaccini and Raff 2003). On the use of bronze more specifically, see (Weinryb 2016). |

| 17 | (Walker Bynum 2011), p. 28; (Kumler 2019). |

| 18 | (Warburg 1920), pp. 33–34. (Quinlan-McGrath 2013), esp. pp. 114–18 and pp. 173–80. See also (Förster 1880; Saxl 1934; Beer 1967; Hartner 1967; Quinlan-McGrath 1984; Lippincott 1990, 1991; Quinlan-McGrath 1995; Dekker 2018; Barbieri 2022). |

| 19 | See (Durling and Martinez 1990), p. 8. |

| 20 | See (Quinlan-McGrath 1995), pp. 66–69. |

| 21 | (Blume 2014), pp. 333–98, especially pp. 380–83. An important precedent for this type of stylized astrological representation was the Sala dei Mesi in Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara by Ercole Roberti from circa 1470. |

| 22 | See (Métal 2021), pp. 196, 207. |

| 23 | “(…) la Tribuna fabbricata a volta rotonda tutta colorata d’azzurro, ornata di stelle, e de’ dodici segni del Zodiaco a mezzo rilievo, e indorati.” Alfonso Landi, Racconto di pitture, di statue, e d’altre opera eccellenti, che si ritrovano nel tempo della cattedrale di Siena (1655), pp. 30–38. Biblioteca Communale, Siena (MS C.II.30). The paintings do not survive. Payment records to Peruzzi for this commission are found in Siena, Archivio del Opera del Duomo di Siena 718, Debitori e Creditori, 593. See also (Huppert 2015), pp. 30–31. |

| 24 | Saxl and Beer were the first to determine that the ceiling represented Chigi’s personal horoscope. (Saxl 1934), pp. 61–67. |

| 25 | (Rowland 1984a). The baptismal record is in the Archivio di Stato di Siena, Pieve di San Giovanni 2 fol. 69r. “Agostino Andrea di Mariano Chigi si batezo a di 30 di novembre 1466 e naque a di 29 di deto messe a ore 21 ½ e fu compare Giovanni Salvani”. |

| 26 | Peruzzi’s choice to show Ursa Minor as a maiden driving a chariot recalls an association that ancient Roman authors frequently made when discussing the constellation. (Quinlan-McGrath 1984), pp. 97–98. |

| 27 | See (Quinlan-McGrath 1995), pp. 65–69. |

| 28 | See (Quinlan-McGrath 2013), pp. 177–80. |

| 29 | Peruzzi would later put his knowledge to use when he collaborated on the publication of Sigismondo Fanti’s curious little fortune telling book called Triompho di Fortuna (Fanti 1527) dedicated to Pope Clement VII. On Peruzzi’s studies in mathematics and astronomy, see also (Vasari 1879), IV: 604. |

| 30 | See (Rowland 1986), pp. 714–15; (Turner 2022), p. 25. |

| 31 | See (Coffin 1979), p. 99. |

| 32 | (Quinlan-McGrath 2013), p. 170. On Salviati, see also, https://800anniunipd.it/en/storia/dragisic-juraj-giorgio-benigno-salviati/ [consulted 1 August 2023]. |

| 33 | See note 18 above. |

| 34 | Petrarch made much use of the petrification metaphor for the convenient opportunities it offered to create puns on his name. His beloved Laura is also compared frequently to Medusa. Poem 37 of his Rime sparse. “(…) Andrei non altramente/a veder lei che ‘l volto di Medusa,/che fecea marmo diventar la gente” [“I would not go to see her otherwise than to see the face of Medusa, which made people become marble.”] (Rime sparse 179, 9–11). (Sturm-Maddox 1985), pp. 86–94. |

| 35 | |

| 36 | English translation and Italian text from (Durling and Martinez 1990), pp. 282–85. |

| 37 | See for example, Petrarch’s Canzone 179. (Durling 1979), pp. 324–25. |

| 38 | |

| 39 | (Ciminelli 1894), p. 49. Translation is mine. |

| 40 | (Durling and Martinez 1990), pp. 278–79. |

| 41 | On Agostino Chigi’s failed courtship of Margherita Gonzaga, see (Rowland 1984b), p. 195; (Dudley 1995; Luchterhand 1996). |

| 42 | |

| 43 | For the lunette scenes by Sebastiano, treated all too hastily here, see (Barbieri 2022). |

| 44 | (Barbieri and Zuccari 2023), pp. 507–9; (Barbieri 2014), pp. 199–211. Several ancient Roman marble copies of this sculpture group exist. While scholars generally assume that the copy housed in the Palazzo Altemps is the one from the former Chigi collection, the Uffizi museum’s version is also a candidate. |

| 45 | This sculptural group is possibly an ancient Roman copy of a lost work by the Greek sculptor Heliodorus, mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History XXXVI: 29. |

| 46 | Ovid, Metamorphoses IV:275. |

References

- Anderson, Christy, Anne Dunlop, and Pamela Smith, eds. 2015. The Matter of Art: Materials, Practices, Cultural Logics c. 1250–1750. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, Nina. 2019. Editor’s Note: Materiality, Sign of the Times. The Art Bulletin 101: 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, Costanza. 2014. Le Magnificenze di Agostino Chigi: Collezioni e Passioni Antiquarie nella Villa Farnesina. Rome: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, Costanza. 2022. Ovid and the Aerial Metamorphoses Painted by Sebastiano del Piombo in the Loggia di Galatea. In After Ovid: Aspects of Reception of Ovid in Literature and Iconography. Edited by Franca Ela Consolio. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 229–59. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, Costanza, and Alessandro Zuccari, eds. 2023. Raffaello e l’antico nella villa di Agostino Chigi. exh. cat. Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei. Rome: Bardi Edizioni. [Google Scholar]

- Barkan, Leonard. 1986. The Gods Made Flesh: Metamorphoses and the Pursuit of Paganism. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baxandall, Michael. 1972. Painting and Experiences in Fifteenth Century Italy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, Arthur. 1967. Astronomical Dating of Works of Art. Vistas in Astronomy 9: 177–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belting, Hans. 1997. Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Art. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blume, Dieter. 2014. Picturing the Stars: Astrological Imagery in the Latin West, 1100–1550. In A Companion to Astrology in the Renaissance. Edited by Brendan Dooley. Leiden: Brill, pp. 333–98. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Stephen, and Michael Cole. 2012. Italian Renaissance Art. New York: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Cellini, Benvenuto. 2002. My Life. Translated by Julia Bondanella, and Peter Bondanella. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cieri Via, Claudia. 2021. Petrification and Animation: The Myth of Perseus as Metaphor for the Paragone in Early Modern Art. In Re-inventing Ovid’s Metamorphoses: Pictorial and Literary Transformations in Various Media 1400–1800. Edited by Karl Enenkel and Jan de Jong. Leiden: Brill, pp. 443–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ciminelli, Serafino. 1894. Le rime di Serafino de’ Ciminelli dall’ Aquila. Edited by Mario Menghini. Bologna: Romagnoli dall’Acqua. [Google Scholar]

- Ciminelli, Serafino, and Antonio Rossi. 2002. Strambotti. Milan: Fondazione Pietro Bembo. [Google Scholar]

- Coffin, David. 1979. The Villa in the Life of Renaissance Rome. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, Michael. 2010. The Cult of Materials. In Revival and Invention: Sculpture Through its Material Histories. Edited by Sébastien Clerbois and Martina Droth. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Comens, Bruce. 1986. Stages of Love, Steps to Hell: Dante’s rime petrose. MLN 101: 157–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Harold, Amy Meyers, and Pamela Smith, eds. 2014. Ways of Making and Knowing: The Material Culture of Empirical Knowledge. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corretti, Christine. 2015. Cellini’s Perseus and Medusa and the Loggia dei Lanzi: Configurations of the Body of State. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Cugnoni, Giuseppe. 1883. Agostino Chigi il Magnifico. Rome: Archivio della R. Società Romana di Storia Patria, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, Elly. 2018. The Astronomical Framework Underlying the Sala di Galatea. Nuncius 33: 537–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, Edward. 1995. Goddess on the Edge: The Galatea Agenda in Raphael, Garcilaso and Cervantes. Calíope 1: 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durling, Robert. 1979. Petrarch’s Lyric Poems: The Rime Sparse and Other Lyrics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durling, Robert, and Ronald Martinez. 1990. Time and the Crystal: Studies in Dante’s Rime Petrose. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fanti, Sigismondo. 1527. Triompho di Fortuna. Venice: Giacomo Giunta. [Google Scholar]

- Förster, Richard. 1880. Farnesina Studien: Ein Beitrag zur Frage nach dem Verhältnis der Renaissance zur Antike. Rostock: Hermann Schmidt. [Google Scholar]

- Frangenberg, Thomas, and Robert Williams, eds. 2006. The Beholder: The Experience of Art in Early Modern Europe. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Freccero, John. 1972. Medusa: The Letter and the Spirit. Yearbook of Italian Studies 2: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Freccero, John. 1979. Dante’s Medusa: Allegory and Autobiography. In By Things Seen: Reference and Recognition in Medieval Thought. Edited by David Jeffrey. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, Michael. 1980. Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frommel, Christoph. 1961. Die Farnesina und Peruzzis architektonisches Frühwerk. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Frommel, Christoph, ed. 2003. La Villa Farnesina a Roma/The Villa Farnesina in Rome. Modena: Cosimo Panini Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner Coates, Victoria C. 2000. Ut Vita Scultura: Cellini’s Perseus and the Self-Fashioning of Artistic Identity. In Fashioning Identities in Renaissance Art. Edited by Mary Rogers. Aldershot: Ashgate, pp. 149–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gombrich, Ernst. 1960. Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gramaccini, Norberto, and Thomas Raff. 2003. Iconologia delle materie. In Del costruire: Tecniche, Artisti, Artigiani, Committenti—Arti e Storia nel Medioevo. Edited by Enrico Castelnuovo and Giuseppe Sergi. Turin: Giulio Einaudi, pp. 395–416. [Google Scholar]

- Hartner, Willy. 1967. Qusayr ‘Amra, Farnesina, Luther, Hesiod: Some Supplementary Notes to Arthur Beer’s Contribution. Vistas in Astronomy 9: 226–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanin, Federico. 1927. La Farnesina. Bergamo: Istituto Italiano d’arti grafiche. [Google Scholar]

- Hirst, Michael. 1981. Sebastiano del Piombo. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holly, Michael Ann. 2013. Notes From the Field: Materiality. The Art Bulletin 95: 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Huppert, Ann Claire. 2015. Becoming an Architect in Renaissance Italy: Art, Science and the Career of Baldassarre Peruzzi. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2007. Materials Against Materiality. Archaeological Dialogues 14: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iser, Wolfgang. 1980. The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, Wolfgang. 1985. Kunstwerk und Betrachter: Der Rezeptions-ästhetische Ansatz. In Kunstgeschichte: Eine Einführung. Edited by Hans Belting, Heinrich Dilly, Wolfgang Kemp, Willibald Sauerländer and Martin Warnke. Berlin: Reimer, pp. 247–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kumler, Aden. 2019. Materials, Materia, Materiality. In A Companion to Medieval Art: Romanesque and Gothic in Northern Europe. Edited by Conrad Rudolph. Hoboken: Wiley & Sons, pp. 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Law, John, and John Hassard, eds. 1999. Actor Network Theory and After. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lippincott, Kristen. 1990. Two Astrological Ceilings Reconsidered: The Sala di Galatea in the Villa Farnesina and the Sala del Mappamondo at Caprarola. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 53: 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippincott, Kristen. 1991. Aby Warburg, Fritz Saxl and the Astrological Ceiling of the Sala di Galatea. In Aby Warburg, Akten des Internationalen Symposions Hamburg 1990. Edited by Horst Bredekamp, Michael Diers and Charloote Schoell-Glass. Hamburg: VCH Verlagsgesellschaft, pp. 213–32. [Google Scholar]

- Luchterhand, Manfred. 1996. Im Reich der Venus: Zu Peruzzis Sala delle prospettive. Römisches Jahrbuch der Bibliotheca Hertziana 31: 207–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzotta, Giuseppe. 1979. Dante, Poet of the Desert. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Métal, Florian. 2021. The Sistine Chapel’s Starry Sky Reconsidered. Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 63: 180–209. [Google Scholar]

- Pliny, the Elder. 1855. The Natural History. Translated by John Bostock, and Henry Riley. London: Henry Bohn. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan-McGrath, Mary. 1984. The Astrological Vault of the Villa Farnesina: Agostino Chigi’s Rising Sign. Journal of the Warburg and the Courtauld Institutes 47: 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan-McGrath, Mary. 1995. The Villa Farnesina: Time Telling Conventions and Renaissance Astrological Practice. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 58: 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan-McGrath, Mary. 2013. Influences: Art, Optics, and Astrology in the Italian Renaissance. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, Ingrid D. 1984a. The Birth Date of Agostino Chigi: Documentary Proof. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 47: 192–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, Ingrid D. 1984b. Some Panegyrics to Agostino Chigi. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 47: 194–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, Ingrid D. 1986. Render unto Caesar the Things Which are Caesar’s: Humanism and the Arts in the Patronage of Agostino Chigi. Renaissance Quarterly 39: 673–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, Ingrid D. 2005. The Roman Garden of Agostino Chigi. Groningen: The Gerson Lectures Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Saxl, Fritz. 1934. La fede astrologica di Agostino Chigi: Interpretazione dei dipinti di Baldassare Peruzzi nella sala di Galatea della Farnesina. Rome: Reale Accademia d’Italia. [Google Scholar]

- Shearman, John. 1992. Only Connect: Art and the Spectator in the Italian Renaissance. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, Donald. 1967. A Reading of Dante’s rime petrose. Italica 44: 144–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm-Maddox, Sara. 1985. Petrarch’s Metamorphoses: Text and Subtext in the Rime Sparse. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thoenes, Christof. 1986. Galatea: Tentativi di avvicinamento. In Raffaello a Roma, Il Convegno del 1983. Edited by Christoph Frommel. Rome: Elefante, pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Thoenes, Christof. 2005. Opus Incertum: Italienische Studien aus drei Jahrzehnten. Munich and Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, James G. 2022. The Villa Farnesina: Palace of Venus in Renaissance Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Eck, Caroline. 2016. The Petrifying Gaze of Medusa: Ambivalence, Ekplexis, and the Sublime. Journal of the Historians of Netherlandish Art 8: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vasari, Giorgio. 1879. Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori. Edited by Gaetano Milanesi. Florence: Sansoni. [Google Scholar]

- Vasari, Giorgio. 1976. Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori scultori e architettori nelle relazioni del 1550 e 1568. Edited by Rosanna Bettarini and Paola Barocchi. Florence: Sansoni. [Google Scholar]

- Walker Bynum, Caroline. 2011. Christian Materiality: An Essay on Religion in Late Medieval Europe. New York: Zone Books. [Google Scholar]

- Warburg, Aby. 1920. Heidnisch-antike Weissagung in Wort und Bild zu Luthers Zeiten. Heidelberg: Carl Winters Universitätsbuchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, Heather. 2003. Dante’s Stone Cold Rhymes. Dante Studies 121: 149–68. [Google Scholar]

- Weil Grarris, Kathleen. 1983. On Pedestals: Michelangelo’s David, Bandinello’s Hercules and Cacus and the Sculpture of the Piazza della Signoria. Römisches Jahrbuch der Bibliotheca Hertziana 20: 409–11. [Google Scholar]

- Weinryb, Ittai. 2013. Living Matter: Materiality, Maker, and Ornament in the Middle Ages. Gesta 52: 113–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinryb, Ittai. 2016. The Bronze Object in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hara, M.Y. Petrified Beholders: The Interactive Materiality of Baldassarre Peruzzi’s Perseus and Medusa. Arts 2023, 12, 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12060246

Hara MY. Petrified Beholders: The Interactive Materiality of Baldassarre Peruzzi’s Perseus and Medusa. Arts. 2023; 12(6):246. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12060246

Chicago/Turabian StyleHara, Mari Yoko. 2023. "Petrified Beholders: The Interactive Materiality of Baldassarre Peruzzi’s Perseus and Medusa" Arts 12, no. 6: 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12060246

APA StyleHara, M. Y. (2023). Petrified Beholders: The Interactive Materiality of Baldassarre Peruzzi’s Perseus and Medusa. Arts, 12(6), 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12060246