Abstract

Among the indicators of the value and power ascribed to statues in Mesopotamia, reuse is a particularly significant one. By studying some of the best-documented examples of the usurpation and reassignment of a new function to sculptures in the round from the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC, our study reveals the variety of motives and methods employed. We hereafter explore the ways in which the status of such artefacts is maintained, reactivated, or adapted in order to secure their agency.

1. Introduction

In ancient Mesopotamia, certain statues stood out because they were considered alive thanks to a process of incarnation (or embodiment). These statues underwent a Washing of the Mouth Ritual (mīs pî1) that led them to transcend their status as mere representations and become the divine entity they represented. Their design and creation, both based on human decisions, culminate in this incarnation process, which enables the representations to transcend their status of objects of craft. It is even required that the sculptors concede the kinship of their production to the divine by saying: “I did not make (the statue); (I swear) I did not [make (it)]; Ninildu, who is Ea the god of carpenter [made it…]”2 (Walker and Dick 2001). In this situation—which concerns only divine statues3, contrary to Egyptian practice4—the concept of agency is significant and the power of the statue easy to identify. However, as theorized by Alfred Gell, even if an image embedded in the cult has a central and distinctive place (Gell 1998, p. 96), the statuary representing kings or elite members also have strong agency. Royal statuary received a form of worship through the daily cultural practices it underwent (Winter 1992, pp. 16–17). As for the images of the orants, ordinary members of the elite, their mere access to the temple, close to the divine image, had an impact on their agency. This special value of statues can be illustrated, for instance, by the efforts made to keep them present in one way or another when they no longer fulfil their initial role (Connor 2018, p. 148).5

Reuse consists of continuing the use of an artefact, but with a new function. This change of function may be significant (e.g., through the inclusion within a ‘collection’ of a statue originally dedicated in a temple) or it may be no more than a minor adaptation (e.g., when an image is (re-)dedicated to a new deity). There are many reasons for such a practice: pragmatism related to the cost of raw materials, the impossibility of getting rid of an object considered to be of sacred nature, the desire to assert one’s dominance over others, the passing on of memories, etc.

This practice is understood as an overarching category comprising the sub-sections of reassignment, usurpation, and recycling. In the frame of this article, the latter—namely the recovery of raw materials (metal smelting, use of the statue as a building block, etc.)—is not considered. While the intended function of the artefact does indeed change—e.g., architectonic element—the life of the statue is not extended for what it once was. Rather, everything it was is transformed/forgotten/adapted. Moreover, the information on this subject is rather of a philological nature. Indeed, the material traces of such a practice are rarely perceptible on the objects itself, the main exception being when a statue or one of its fragments is used as a building block or, as well attested in Egypt, as vases or hammers (Junker 1950, pp. 125–26; Eaton-Krauss 2008). In Mesopotamia, the recovery and rework of some raw materials is also attested. Precious metals are melted down (Na’aman 1981) or stone is transformed into gypsum by the effect of heat (Evans 2012, p. 141).

As for the other two sub-sections, they form the basis of the organization of this paper. The first part is devoted to usurpation and the second to reassignment, the one being the appropriation of a statue’s identity and the other its modification.6 Before delving into the case studies, it is essential to define this study. It is part of a wider research project looking at all aspects of the ‘life’ and ‘death’ of Mesopotamian statues. It is, therefore, a work in progress, destined to evolve and, above all, to be compared with other practices, reuse being only one of them.7 To quote Nancy Highcock on votive objects that have been recast, moved, buried, and recovered: “The lives of dedicated objects in ancient Mesopotamia were dynamic” (Highcock 2021, p. 40). Through case studies, we will endeavor to encompass the trajectory of statues to this variety of reuses.

2. Case Studies

Unlike Egypt, there is very little evidence of reuse over the three millennia of Mesopotamian history (to delve deeper into this issue in Egypt: Brand 2010a, 2010b; Eaton-Krauss 2015). Statues with slight modifications, such as the removal of the beard,8 exist in addition to the five usurpation examples studied in this paper. However, nothing can be concluded about the when, why, and how of this change, which could even be the result of a change at the time of production rather than a reuse. As for attestations of reassignments, the corpus presented in this paper is exhaustive as far as archaeological evidence is concerned. Other deportations—involving modifications—are documented, but exclusively by texts and they are therefore not all included here.9 The cuneiform tablets describing Akkadian statues (cf. Section 2.2.5) are discussed here, since they are considered to be ekphrasis of statues that have been exhibited. It is precisely because the documentation is scarce and sometimes makes it difficult to come to precise conclusions that the organization of these case studies is based on their relevance, the first examples being the most revealing in respect to the issues.

Apart from the statues, however, several texts provide information about the practice of reusing artefacts. In the 8th century BC, Sargon II (Neo-Assyrian ruler, ruling between 721–705 BC) had paraphernalia, such as a cultic bed and various gold objects, moved to temples in Dur-Šarrukin (present-day Khorsabad, Iraq) (Parpola 1987, pp. 49–51, 93–96; Reade 2002, p. 200). As it appears, the cult function of these objects remained similar, but they were dedicated to other deities in a different place. Small objects such as beads (Galter 1987, p. 17), cylinder seals (Amiet 1976, p. 60; Thomason 2005, pp. 155–56), or vases (Eppihimer 2010, p. 378) are among the artefacts that have undergone this type of adaptation, as their size makes them easy to usurp. In short, reuse took many different forms and served many different purposes.

Among the testimonies to this habit related to statuary are the curse formulas10 precisely meant to prevent such practices. One of the aims of creating an anthropomorphic representation was to ensure that the memory of the individual represented would live on, presumably forever. It inevitably involved the risk of seeing this person, via the medium of their representation, attacked (Bahrani 1995, p. 381). It is therefore easy to understand the importance of protecting one’s statue to protect oneself. The same applies to the name, which, once inscribed, serves the same function of leaving its mark on history, but carries the same risk of being erased (Radner 2005, p. 252). These curse formulas are attested in Mesopotamia, generally placed at the end of dedication inscriptions, intended to protect a monument, a text, an individual, etc. The curse formulas referring to the practice of reuse are those dealing with the damage inflicted on the text rather than on the image itself.11 Many of them are structured as follows:

(RIME 4.06.11.1 [Old Babylonian Period]—l. 17–19)

“He who removes my inscribed name and has his (own) name ins[cri]bed (…)”

(17. ša šu-mi 18. ša-aṭ-ra-am 19. u3-ša-sa3-ku-ma 20. šum-šu u3-ša-aš2-[ṭa]-ru)

As far as sculptures in the round are concerned, what are the criteria for identifying these acts of reuse? Ideally, the image has been transformed, whether this concerns the representation (e.g., changing the features of the face) or the inscription (changing or adding a name to provide a new identity). Stratigraphy also provides information: an archaic style discovered in a more recent layer for instance. However, all these criteria must be considered with caution. An adaptation of a figure or text might simply represent a correction that occurred at the time of production. On the other hand, a style that contrasts sharply with the archaeological layer may attest to the persistence of styles though time. This is what Eva Strommenger warns against when she points to an assertion by Henry Frankfort: “Frankfort seems to assume a stylistic influence from the previous period when he says: ‘In Akkadian works of lesser quality the affinities with the older period are so pronounced that it is sometimes only possible to assign a work to the Akkadian Period because an inscription names the reign in which it was made.’ He also turns to the inscription as the final dating authority, although he clearly recognizes the foreignness of this monument within the Akkadian period.”12 (Frankfort 1955, p. 43; Strommenger 1959, p. 34). In delicate situations where a style seems incompatible with the context in which it is discovered, he presents inscriptions as the best means of dating. She rightly insists on the fact that a single method is conclusive, namely the combination of a study of the style, the inscription (when existing), and the historical context (Strommenger 1959, pp. 28, 36, 50).

2.1. Usurpation

Usurpation regularly occurs by modifying or adding an inscription.13 Understandably, these two methods have very different implications, respectively erasure of the previous owner or the cohabitation with the new one, who may then wish to stress their respect or superiority vis-à-vis the previous owner. This investment in the inscription can also be coupled with displacement since a change of context easily leads to a change of function.14 This practice, known as deportation of the statue, served several purposes. The aim was of course to overcome the enemy, but it was also an opportunity to appropriate their greatness and aura. To appropriate the power of an enemy implies to admit said power. Deportation is therefore a practice that walks the thin line between violence and respect, just like reappropriation. Another way to acknowledge this state of fact is the considerable effort required to move a monumental statue15 (and ultimately any looted object). One might rightly argue that such a considerable effort might not have been undertaken if the purpose was simply to break a valuable artefact to deprive the enemy of it.

Besides this difficulty of determining the intention behind a reuse, another difficulty is that examples are not so easy to identify. As Jean Evans pointed out, many unearthed isolated statue heads might constitute evidence of a habit of replacing them in order to reuse a statue’s body and thus save time and resources (Evans 2012, p. 140). In the meantime, if it is enough to add or change a name to completely alter the identity of an image, it is interesting to address the question of portraiture, an overall rather complex concept, the meaning of which has evolved over time. However, it is generally accepted that the situation in Mesopotamia is similar to the one in Egypt. The representations in both cases were intended to emphasize elements that identified and enhanced the status or function of the individual depicted rather than individualizing them through their physiognomy. It appears that the aim was not to copy, but to confer a significant character to the production (Belting 1993, p. 129; Winter 2009, pp. 266–67; Laboury 2010; Asher-Greve and Westenholz 2013, pp. 159–62; Guichard 2019, p. 31). The statue of Puzur-Eštar (šakkanakku16 of Mari (present-day Tell Hariri, Syria), from the 20th century BC), which we will address in detail later on (cf. Section 2.2.2), is an illustration of this understanding of the concept of portrait. It demonstrates that modifications are only necessary in the case of a change in status or function. Indeed, this depiction of a šakkanakku had horns, the divine symbols par excellence in Mesopotamian iconography, carved in his headress to become a divine representation (Blocher 1999).

Regrettably, nothing on the matter of reuse can be said with any certainty, and the same is true of most of the clues that suggest usurpation. For instance, a work in an ancient style, present in a recent stratigraphic layer, may have “lived” for a long time without necessarily having been reattributed (Hauptmann 1989, p. 33). The five attestations studied in this paper are significant due to their context of discovery or the traces of modification they bear, enabling a closer look at their (multiple) lives.

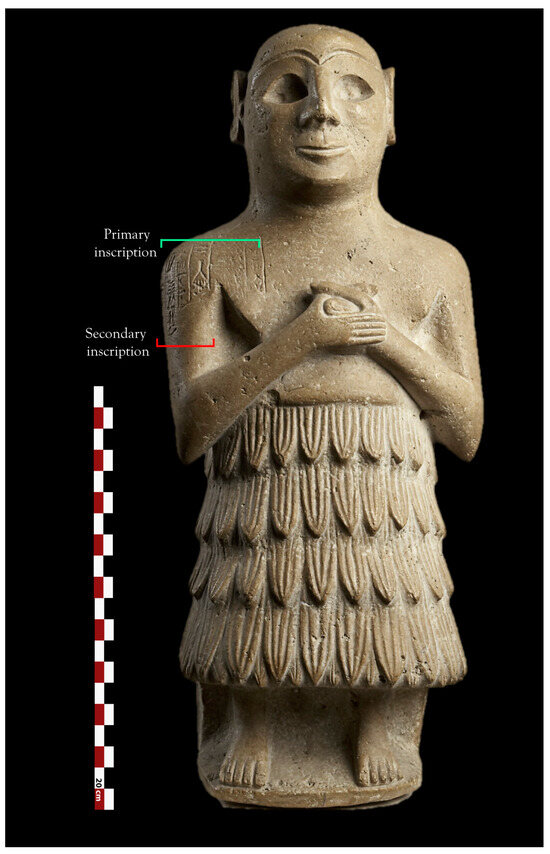

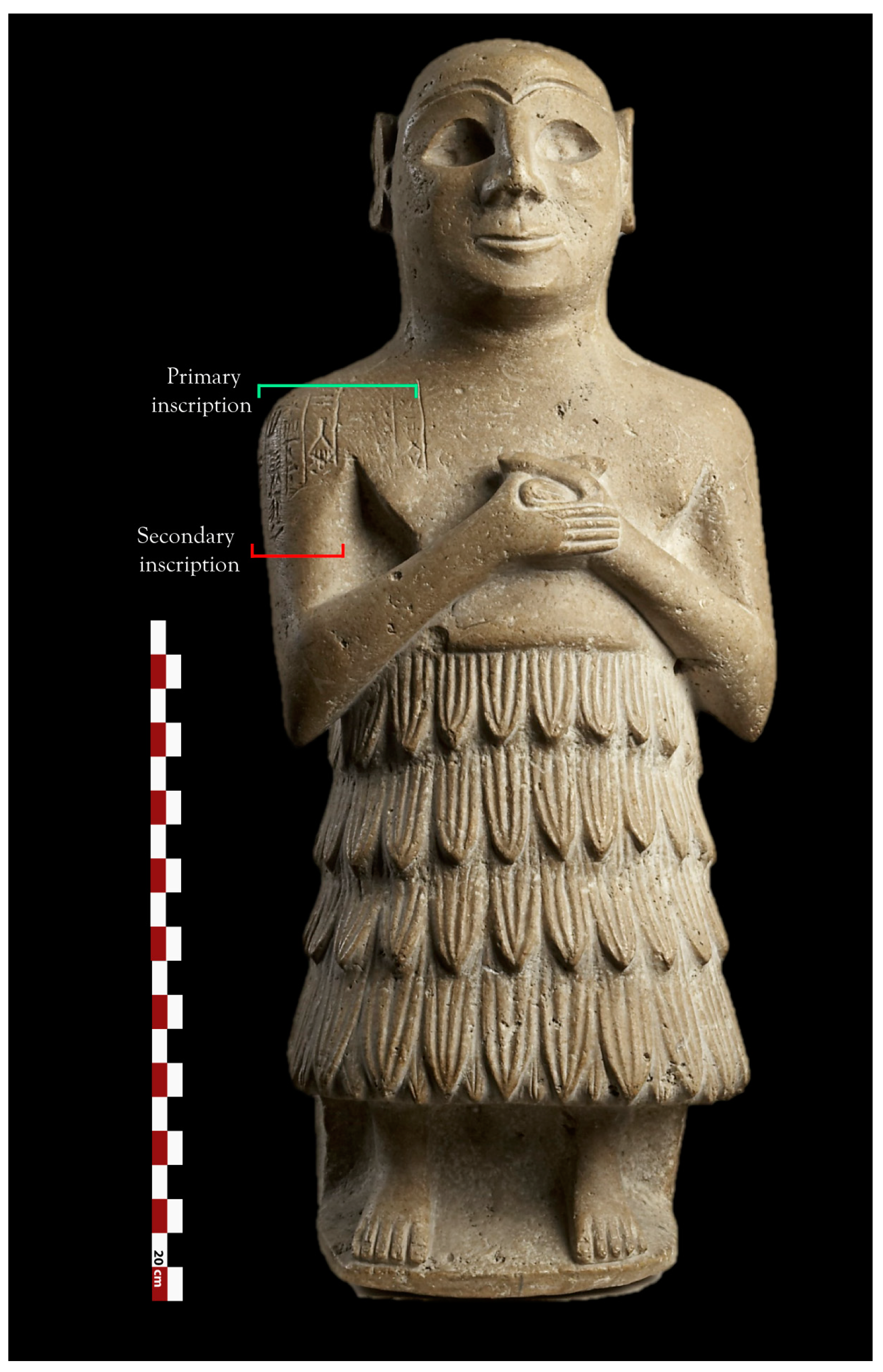

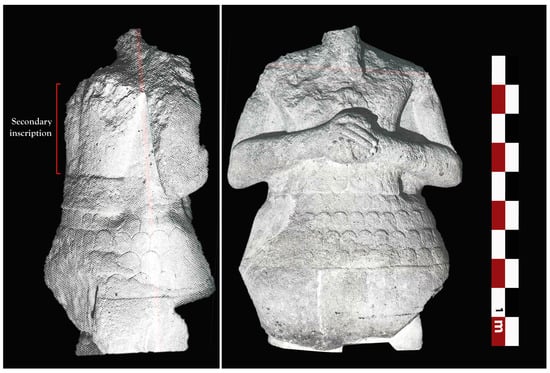

2.1.1. Liebieghaus Orant [1453]17 (Figure 1)

According to Eva Andrea Braun-Holzinger in 1991,18 the only established usurpation of a Mesopotamian statue was identified thanks to the modification of the inscription, namely on an orant statue preserved in the Liebieghaus in Frankfurt am Main (n°1453; H: 37.5 cm) (E. A. Braun-Holzinger 1991, pp. 220, 254). According to her, the only valid clue is the clearly visible ‘palimpsest’ effect. This limestone statuette is dated to the Early Dynastic (ED) III (ca 2600 to 2330 BC) and depicts an orant, hands clasped, wearing a kaunakes.19 Unfortunately, since it was acquired by an American collector before entering the German collection in 1955, its provenance is unknown (Hauptmann 1989, pp. 3–4). The inscription on the right shoulder is inscribed on a polished area: according to Ralf Hauptmann, a first inscription in Sumerian was erased—a few lines of the old inscription are still discernible. The one visible today, in Akkadian, was inscribed at a later date (Hauptmann 1989, p. 5). Though carefully erased, the verb ‘to consecrate’ in the Sumerian text can be identified. It is likely that it was, as the Akkadian one, a dedication to identify the owner of the statue and the god to whom he is offering his representation.

(R. Hauptmann 1989, p. 5; Liebieghaus 1453—l. 1–6)

“For (the god) Lugal-asal, Bazi son of Bēlī-Tišpak, the pašīšu-priest dedicated this.”

(1. ana 2. dLUGAL-ASALX 3.Ba-zi 4. DUMU be-li2-Tišpak 5. KI?/ŠU?.pa4-šiš 6. A.MU.NA.RU)

R. Hauptmann suggests that the Akkadian inscription dates back to the very beginning of the 2nd millennium BC due to the text organization and the signs variability (Hauptmann 1989, p. 6). This means there may be three centuries separating the two inscriptions and/or the carving and the addition of the second inscription. What we have here is indisputable evidence of usurpation. It was suspected due to the erasure of an inscription and confirmed thanks to a lack of consistency between the dating of the representation and the dating of the new inscription. These same criteria are relevant in the study of the following case.

Figure 1.

Statue of the orant [1453] from the Liebieghaus. Courtesy of the Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, Frankfurt am Main.

Figure 1.

Statue of the orant [1453] from the Liebieghaus. Courtesy of the Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, Frankfurt am Main.

2.1.2. Ešpum [Sb 82] (Figure 2)

An alabaster bust was discovered on the acropolis of Susa (present-day Shush, Iran) in 1906 and is currently displayed at the Louvre (Sb 82; H: 31.2 cm). An inscription was added to the back of this bust (Frayne 1993, pp. 81–82):

(RIME 2.01.03.2001 [Sargonic and Gutian Periods]—l. 1–8)

“Maništūšu, king of the world: Ešpum, his servant, dedicated (this statue) to the goddess Narunte.”

(1. ma-an-iš-tu-su 2. LUGAL 3. KIŠ 4. eš4-pum 5. IR11-su 6. a-na 7. dna-ru-ti 8. A.MU.NA.RU)

On the one hand, the anthroponyms allow this inscription to be dated to the end of the 3rd millennium BC since Maništūšu was an Akkadian ruler (ruling between 2284 and 2262 BC). On the other hand, given the style of the statue, which dates from the middle of the 3rd millennium BC, the cuneiform text was added several centuries after the creation of the sculpture (Spycket 1981, p. 73; Frayne 1993, 2:81; Highcock 2021, p. 42). There is no evidence that a first inscription was erased and/or covered by the new one.20 Apparently this reuse is pragmatic, as there is nothing to suggest a desire to impose itself over the identity of the previous owner. Now, to speak of opportunism, we need to know whether steps were taken to move the object or whether it was already in Susa at the outset. Moreover, the antiquity of the object may have made it valuable to the new owner (Highcock 2021, p. 42).

Agnès Spycket and E. Strommenger argue with confidence that the object, of Susian origin, was usurped after three hundred years and appropriated through the addition of an inscription (Strommenger 1959, pp. 34, 36; Spycket 1981, pp. 73–74). E. Braun-Holzinger questions this proposition, believing instead that it reflects a simple persistence of ancient styles, which is attested in Mesopotamia and Elam (E. A. Braun-Holzinger 1991, p. 220). The distinctive beard leads her to believe that this is a local Elamite production, but designed for the Akkadian ruler (E. A. Braun-Holzinger 1991, pp. 257–58). Due to the lack of evidence of Elamite productions of this type, this remains to be studied with hindsight (Evans 2012, p. 230). E. Strommenger responds that, stylistically, the statue strictly follows the codes of earlier style in the 3rd millennium BC. She also rejects the possibility of an ancient inspiration, as the retouching work carried out on the hair bears witness to a period of modification of the work which supports the idea of an usurpation (Strommenger 1959, pp. 34–36). A similar discussion arose regarding the next representation, discovered in southern Mesopotamia.

Figure 2.

Statue of Maništušu [Sb 82] from the Louvre. Front: Courtesy of the Musée du Louvre (1999 Jérome Galland); Back: (Strommenger 1959, 31, pl. IIb).

Figure 2.

Statue of Maništušu [Sb 82] from the Louvre. Front: Courtesy of the Musée du Louvre (1999 Jérome Galland); Back: (Strommenger 1959, 31, pl. IIb).

2.1.3. Ekur/Kurlil [BM 114206] (Figure 3)

This statue, discovered at Tell Al-’Ubaid (present-day Iraq) in 1919, is currently stored in the British Museum (BM 114206; H: 34 cm). Although it was discovered in a well-dated context from the 3rd Dynasty of Ur (ca 2100 to 2000 BC) (Hall and Woolley 1927, pp. 19–20) alongside another representation (BM 114207), its identity and chronology raises several questions. At one point, the two sculptures had been identified as an image of the same individual: Ekur (=Kurlil) (Hall and Woolley 1927, pp. 19, 27, 125). However, the other statue, although in an overall good state of preservation, displays a very fragmentary inscription, with only one sign remaining. The sign in question has long been read as E2 (E. A. Braun-Holzinger 1991, p. 252), but Gianni Marchesi and Nicolò Marchetti have corrected the reading to NIMGIR, proving that it is not the same dedicant (Marchesi and Marchetti 2011, pp. 66, 163). As for the statue we are concerned with, its inscription, unframed but with separating lines, reads:

(Marchesi and Marchetti 2011, 163—l. 1–5)

“Ekur, superintendent of the granaries of Uruk, created a (statue of) Damgalnunak and built (her) ‘house’.”21

(1. e2:kur 2. KA:GUR7-unugki 3. ddam:gal-nun 4. mu-du2 5. [e2] mu-řu2)22

Due to the archaic nature of the inscription, G. Marchesi and N. Marchetti suggested that it came from an earlier level of the temple in which it was discovered (Marchesi and Marchetti 2011, p. 66). At the time of its publication by the excavators, they had already noticed the unusual nature of the inscription, but nevertheless had no doubt that it was contemporary with the layer where it was found (Hall and Woolley 1927, pp. 19–20, 125). As for the style of the statue, A. Spycket considers it to be Early Dynastic II (ca 2750–2600) based on the large format of the arms and the fact that they are detached from a narrow bust (Spycket 1981, p. 106). Considering both the surrounding stratigraphical data and the style of the statue, this representation would have persisted for around five centuries, a period during which, at an unidentified moment, it was allegedly usurped.

Much could also be said about its state of preservation, since it is particularly damaged in an archaeological context where the majority of other artefacts were found in good condition. Thus, Julian Reade proposes a deliberate attack on this particular representation (Reade 2000, p. 83). The fourth case is in a poor state of preservation too, and the lack of diagnostic features such as the head or inscriptions is a limiting factor in the study of reuse and its circumstances.

Figure 3.

Statue of Ekur/Kurlil [BM 114206] from the British Museum. © 2023 Imane Achouche.

Figure 3.

Statue of Ekur/Kurlil [BM 114206] from the British Museum. © 2023 Imane Achouche.

2.1.4. ‘Statue Cabane’ [Aleppo Museum M 7917/1326] (Figure 4)

Known as the ‘Statue Cabane’ (H: ca 1.10 m, estimated weight 300 kg), it is an acephalous representation discovered in 1933 on the tell of Mari, before the first archaeological excavations on the site (Parrot 1935, p. 1; Thureau-Dangin 1939, p. 157). It was named after the Lieutenant Cabane who took it to the Aleppo Museum (n°M 7917 or 132623). The dedication on the lower half of the garment attributes the statue to Yasmaḫ-Addu (ruler of Mari, from the 18th century BC) (Thureau-Dangin 1934, p. 144; Frayne 1990, pp. 615–16):

(RIME 4.06.11.1 [Old Babylonian Period]—l. 1–15)

“[Ia]smaḫ-Addu, ap[point]ee of the god Enlil, [so]n of Šamšī-Adad, for the god Šamaš, his lord […] [had] (this statue) fashioned in [the city of] M[ari, wh]ich he l[ov]es, and [de]dicated (it) (…)”

(1. [ia-a2]s-ma-aḫ-dIŠKUR 2. š[a-k]i-in den-lil2 3. [DUM]U dUTU- dIŠKUR 4. a-na dUTU 5. be-li2-šu 6. […] 7. […] 8. [m]u(?)-te-[…] 9. […] 10. […] ni […] 11. [i]-na q[e2]-r[e-e]b 12. [a-al] m[a-ri.K]I 13. [š]a i-r[a-a]m-mu 14. [u2-še]-p[i2-i]š-ma 15. [u2-š]e-li)

Ursula Moortgart-Correns suggested in 1986 that it was an usurpation, since the overall shape of the body indicates that it must originate from an earlier period, with the treatment of the beard definitely being of the very beginning of the 2nd millennium BC (Moortgat-Correns 1986, p. 185). As for the original identity, she argues that it was a mountain god, given the type of clothing and the posture, appearing to be carrying a load. She therefore considers that it could have been part of a pair framing a door (Moortgat-Correns 1986, pp. 183–84). However, divine statues in stone are rarely attested archaeologically in Mesopotamia, not to mention that there is no evidence of pairs of gods integrated into architecture before the 1st millennium BC. Still, neither the style nor the type of statue correspond to what would be expected of a šakkanakku image from this period.

U. Moortgart-Correns also noticed that no trace of reworking was visible, not even the removal of an earlier inscription that would have been replaced by that of Yasmaḫ-Addu (Moortgat-Correns 1986, p. 186). However, we must not lose sight of the state of conservation of the artifacts examined. Nonetheless, the elements of the head (headdress, facial features) would have been the first to be modified if this were to be done, but many statues—including this one—have been decapitated. However, as we have seen, usurpation does not necessarily require the adaptation of the features of the representation, as the addition of the inscription may be enough. The following statue is of particular interest in this respect.

Figure 4.

‘Statue Cabane’ [M 7917/1326] from the Aleppo Museum. © (Moortgat-Correns 1986, pl. 36.1 & pl. 37.6).

Figure 4.

‘Statue Cabane’ [M 7917/1326] from the Aleppo Museum. © (Moortgat-Correns 1986, pl. 36.1 & pl. 37.6).

2.1.5. Urlammarak [BM 91667] (Figure 5)

This is a very peculiar statue, which entered the British Museum collection (BM 91667; H: 14.6 cm) by purchase in 1854 and whose provenance is therefore uncertain (Reade 2000, pp. 84–85). At first sight, the cohabitation of two inscriptions would suggest that there was no intention to usurp. However, it is difficult to understand the order in which the cuneiform was inscribed or even the exact date of the bust production. It features an inscription on the back, now considered to be the original, which identifies the individual as Urlammarak:

(Marchesi and Marchetti 2011, 168—l. 1–2)24

“Urlammarak, viceroy of AN.PA.x”

(1. ur:dlammarx(KAL) 2. NIĜ2 [PA].SI AN.PA.[x])

This inscription on the back is most probably contemporaneous to the statue’s creation; both the style of the writing and the representation are dated to the Early Dynastic (ca 2900–2330) (Marchesi and Marchetti 2011, p. 130). It is an inscription on the shoulder that attests to the reuse of this object. These are cuneiform signs that are incomprehensible and difficult to date. They are dated to the 1st millennium BC by G. Marchesi and N. Marchetti (Marchesi and Marchetti 2011, p. 168) or to the beginning of the Early Dynastic period by E. Braun Holzinger (E. A. Braun-Holzinger 1977, p. 75). Regardless of their dating, it is quite clear that the two inscriptions were not written at the same time. If the shoulder inscription is correctly considered to be a (much) later addition, and if it is indeed meaningless, then its purpose could be to fulfil an interest in the past rather than to convey a message (Marchesi and Marchetti 2011, p. 130).

At one point, E. Braun-Holzinger proposed that the inscription on the back was a later addition too. According to her, this sculpture in the round was an imitation of an Early Dynastic Style (E. A. Braun-Holzinger 1977, p. 75). Then she suggested that it was the reuse of a statue that had been reworked to give it an older style (E. Braun-Holzinger 2007, p. 44). These supposed traces of retouching work are to be seen in the holes drilled in the nose and scratch marks on the forehead. She thus suggests that the hair and eyes must also have been modified (E. Braun-Holzinger 2007, p. 44). However, the elements in question could very well be traces of repair, as attested in Mesopotamia. In any case, the reuse of the statue is illustrated by the addition of the shoulder inscription whether the image features have also been retouched or not.

Figure 5.

Statue of Urlammarak [BM 91667] from the British Museum. © 2023 Imane Achouche.

Figure 5.

Statue of Urlammarak [BM 91667] from the British Museum. © 2023 Imane Achouche.

More than a quarter of a century ago, Eva Andrea Braun-Holzinger considered that a single statue was certainly a case of usurpation (E. A. Braun-Holzinger 1991, p. 220). Nowadays, four statues in addition to this orant statue from the Liebieghaus have been considered. This is an extremely small total, especially given the large amount of statuary discovered in Mesopotamia.25 Marian Feldman explains that: ‘‘The apparent hesitancy to reuse statues may be traceable to the close correspondence posited by the ancient Mesopotamians between an individual and his or her image.” (Feldman 2009, p. 46).

2.2. Reassignment

When the objective is not to completely appropriate the statue by erasing the memory of its past, it is a question of making its new existence coexist with its past identity. This practice may even, sometimes, aim to insist on the original identity of the image. This is for example the case when king Nabonidus (Neo-Babylonian ruler, ruling between 556–539 BC) took care of a representation of Sargon of Akkad26 found in the Ebabbar foundations (Šamaš temple in Sippar, present-day Tell Abu Habbah, Iraq). This ‘antiquarianism’, as described by Melissa Eppihimer, was the result of a “face-to-face encounter with an ancient king” (Eppihimer 2019, pp. 1–2).

When seeking to reassign, as well as to usurp, what is more common is the addition of an inscription. However, in the second case, it cohabits with a previous inscription, or refers to it if it has not been preserved.

2.2.1. Šutruk-Naḫḫunte I’s Loot

There are few examples dating back to Šutruk-Naḫḫunte I (ruler of Elam, ruling between 1185–1155 BC), who had numerous objects carried away from Babylonia to Susa. This deportation policy was massive. Nearly half of the kudurrus/narûs27 excavated so far were found in Susa, although none were produced for the city (Slanski 2003). As for the statues, at least sixteen were discovered in Susa, transported from Babylonian cities (Table 1). On nine of them, traces of an inscription by Šutruk-Naḫḫunte I remain, indicating that he had recovered these representations and taken them to Susa. An example of these inscriptions, all relatively similar, can be found on the statue Sb 61, depicting a seated sovereign:28

“I am Šutruk-Naḫḫunte, son of Hallutuš-[In]šušinak, king of Anšan and Susa, the great likume(=SUKKAL.MAḪ in Akkadian inscriptions), the throne [holder of Ela]m, sovereign of the land of Elam. [Inšušinak], my god, having helped me, [I have destroyed] Eš[nunna]; I have taken away from there [the statu]e and I have brought it [to the country of El]am. [I have placed it before Inšušinak], my god.”

(1. u2 Išu-⸢ut-ru⸣-uk-Dnah-hu-un-te ša-ak Ihal-lu- 2.-du-uš-⸢D⸣[in]-šu-ši-na-ak-gi-ik su-un-ki- 3.-ik AŠan-za-an AŠšu-šu-un-ka4 li-ku-me ri-ša-ak 4.-ka4 ka4-a[t-ru ha-tam5-ti]-⸢ik⸣ hal-me-ni-ik ha-tam5-ti- 5.-ik ⸢D⸣[in-šu-ši-na-ak] ⸢na⸣-pir2 u2-ri ur-tah-ha-an 6.-ra AŠiš-[nu-nu-uk hal-pu-uh za-al-m]u a-ha hu-ma-ah 7. a-ak hal-ha-[tam5-ti te-en-gi-ih Din-šu-ši-na-ak] 8. na-pir2 u2-ri [i si-ma-ta-ah])

Regarding those statues with no inscription, chances are that the inscription is simply missing. It is indeed very common that the statues bear an inscription in Mesopotamia, at least the title of the individual represented (Winter 2010, p. 185). Depending on the period, material, and type of object, the location of the inscription may vary, but it is very often the upper back or lower part of the garment—large, flat areas. For example, Sb 60, which was badly damaged, may have carried an original inscription that is now missing from what was excavated. Similarly, the absence of an Elamite (=Hatamtite29) inscription may be linked to surviving evidence. In any scenario, it is worth questioning whether there is a primary and/or secondary inscription, and whether it is due to conservation reasons or a voluntary decision. Indeed, at least Sb 85 is sufficiently well preserved and still shows no inscription, indicating that the addition of a text by Šutruk-Naḫḫunte I was not systematic. Another variable is the appearance of the name of the sovereign initially represented. Indeed, while some of the secondary Elamite inscriptions mention the king who was originally depicted, in other examples a blank space was left, which was almost certainly intended to be filled in with the name of the king, but this was never carried out. These vacats provide a very interesting insight into the process by which stone inscriptions were made. The addition of an inscription, including the name of the sovereign represented by the statue, indicates that there was a possible attempt—and that an effort was made—to read the original inscription. Furthermore, it is essential to remember that the aforementioned rulers were not those who were ruling in the looted cities. As can be seen from the table below, the rulers identified lived between ten and five centuries before Šutruk-Naḫḫunte I.

Table 1.

Statues deported to Susa from Mesopotamia,30 with details of the inscriptions (ordered according to the chronology of the rulers initially represented). Based on Melissa Eppihimer’s work (Eppihimer 2010). [? = information unavailable; no = sufficiently preserved to confirm absence; / = not sufficiently preserved to confirm absence].

Table 1.

Statues deported to Susa from Mesopotamia,30 with details of the inscriptions (ordered according to the chronology of the rulers initially represented). Based on Melissa Eppihimer’s work (Eppihimer 2010). [? = information unavailable; no = sufficiently preserved to confirm absence; / = not sufficiently preserved to confirm absence].

| Museum Number(s) | (H × L × Th) | Sovereign | Reign Dates | Origin | Original Inscription | Secondary Inscription |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sb 47 + Sb 9099 | 100 × 58 × 48 cm | Maništusu | 23rd century BC | Akkad (?) | / | Claim of the deportation by Š.-N. |

| Sb 51 | 20 × 31 × 36 cm | Maništusu | Babylonia | Extract of the standard inscription | / | |

| Sb 15566 | H: 5 cm | Maništusu | Babylonia | Extract of the standard inscription | / | |

| Sb 49 + Sb 50 + Sb 9097 | 99 × 100 × 56 cm | Maništusu | Akkad (?) | / | Claim of the deportation by Š.-N. | |

| Sb 52 | 59 × 47 × 64 cm | Naram-Sîn | 2261–2206 BC | Babylonia | Dedication of the statue | / |

| Sb 53 | 18 × 15 × 11 cm | Naram-Sîn (by Šu’āš-takal)31 | Babylonia | Dedication of the statue | / | |

| Sb 57 | 50 × 23 × 14 cm | Ur-Ningišzda | 20th century BC | Ešnunna | Dedication of the statue, deliberately erased | Claim of the deportation by Š.-N. |

| Sb 56 | 62 × 26 × 17 cm | ? | Early 2nd mill. BC | Ešnunna | Illegible, deliberately erased | Claim of the deportation by Š.-N |

| Sb 58 | 40 × 21 × 26 cm | ? | Early 2nd mill. BC | Ešnunna | Illegible, deliberately erased | Claim of the deportation by Š.-N. |

| Sb 61 | 89 × 52 × 55 cm | ? | Early 2nd mill. BC | Ešnunna | Illegible, deliberately erased | Claim of the deportation by Š.-N. |

| Sb 5932 | 24 × 17 × 19 cm | ? | Early 2nd mill. BC | Ešnunna | / | Claim of the deportation by Š.-N. |

| Sb 85 | 20 × 11 × 7 cm | ? | Early 2nd mill. BC | ? | no | no |

| Sb 141 | 30 × 33 × 20 cm | ? | Early 2nd mill. BC | Babylonia | / | / |

| Sb 163 | 31 × 27 × 18 cm | ? | Early 2nd mill. BC | Ešnunna | / | Claim of the deportation by Š.-N. |

| Sb 95 | 15 × 9 × 11 cm | Hammurabi (?) | 1792–1750 BC (?) | Babylonia | / | / |

| Sb 60 | 66 × 35 × 20 cm | ? | ? | ? | / | Claim of the deportation by Š.-N. |

2.2.2. Puzur-Eštar [EŞEM 7813] (Figure 6)

As we mentioned in the introduction, this is an excellent example of what can be performed to adapt a pre-existing statue. On 22 April 1914, a pair of life-size statues (H: 1.7 m) were unearthed in Nabuchadnezzar II’s Babylon (Neo-Babylonian ruler, ruling between 605–562 BC). They are preserved in the Eski Şark Eserleri Müzesi in Istanbul under numbers EŞEM 7813 and EŞEM 7814, except for the head of the best-preserved statue, which is in the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin under inventory number VA 08748. Dated to the 20th century BC, they are identified as representations of Puzur-Eštar, thanks to the inscription on EŞEM 7813. This statue is also the one featuring a pair of horns, a divine attribute in Mesopotamian iconography. The presence of this feature led scholars to consider for some time that it was a representation of a deified ruler. A representation of a god would have had to feature more than a simple row of horns, and two-dimensional examples of deified kings were discussed as parallels (Nagel 1959, pp. 262–65).

The inscription on the right forearm identifies their dedicators as being Puzur-Eštar, šakkanakku of Mari, as well as his brother, Ṣilla-Akka,33 while that on the lower garment identifies another dedicator, Tūra-Dagan, also šakkanakku of Mari and father of Puzur-Eštar (Gelb and Kienast 1990, pp. 363–64; Colonna d’Istria 2022, p. 180). It is suggested that the inscription on the forearm was added later, perhaps after the father’s death, by the two sons (Nassouhi 1926, p. 109). The other statue, EŞEM 7814, also featured inscriptions, but they were damaged, like most of the statue itself. Those artefacts were found in what was once thought to be a palace-museum, but is rather a place where “monuments fulfilling both an information and a propaganda function” (Joannès 2011, p. 118) are concentrated. In the Nabuchadnezzar II case specifically, the purpose seems to have been to expose war spoils. Their exposition seems to have been more intended as an effort for public demonstration of power, or even as a magical assemblage aiming to diminish or humiliate the enemies’ gods, rather than an exhibition accessible to all to educate or decorate, as a museum would do (Klengel-Brandt 1991, p. 45). In parallel, the addition of the horns, which turn out to be a modification of the pre-existing headdress of the šakkanakku, have been part of a desire to deify this ancestor, or rather because the identity of the character had been lost.

Figure 6.

Left: Statue of Puzur-Eštar [EŞEM 7813]. © Laurent Colonna d’Istria (2007). Right: Statue of Puzur-Eštar [EŞEM 7814]. © Laurent Colonna d’Istria (2007).

Figure 6.

Left: Statue of Puzur-Eštar [EŞEM 7813]. © Laurent Colonna d’Istria (2007). Right: Statue of Puzur-Eštar [EŞEM 7814]. © Laurent Colonna d’Istria (2007).

2.2.3. Puzur-Sušinak34 (Figure 7)

Françoise Tallon published an article in 1993 in which she suggested that several of the artefacts (table Sb 17, limestone lions Sb 98 and b 99, pebble Sb 6) attributed to Puzur-Sušinak (ruler of Elam, ca 2100–2050 BC), though—potentially, as the depths are not systematically documented—discovered in a more recent level, may have been a reuse (Tallon 1993, p. 107). She includes in this list the statue Sb 48, discovered in the area of the temple of Insušinak. According to her, this sculpture is also a representation of Puzur-Sušinak rather than a sovereign of the Akkad dynasty, deported by Šutruk-Naḫḫunte I, as is commonly accepted (Tallon 1993, pp. 105–6). In this scenario, this representation of the Elamite ruler may have been recovered as a pivot stone, given the traces it bears on the front (Tallon 1993, p. 108). The stratigraphic argument is valid: the statue Sb 48, when compared to some looted items, is neither in the same place (temple area versus acropolis), nor at the same level (3.2 m above level II as opposed to the 6 m to 7 m of some of the deported objects). However, the context of the objects deported by the Šutrukids (Elamite dynasty, from the 13rd and 12th centuries BC) is not systematically documented (Harper 1994, p. 161), and the statue Sb 48 is more similar to Akkadian productions than to surviving representations of Puzur-Sušinak. Javier Álvarez-Mon, based on this argument, proposed an Akkadian inspiration for this image of Puzur-Sušinak (Álvarez-Mon 2020, p. 278).

In the end, this sculpture was reassigned, either as a result of a deportation from Mesopotamia, when it became part of the spoils of war, or as a result of a change of context within the city of Susa itself. Indeed, the traces it bears most certainly testify to wear related to a use that is difficult to identify, the pivot stone being one of several possibilities. The other way round is also possible, since Sb 55 (H: 84 cm) is often considered to have been usurped by Puzur-Sušinak, as the type of clothing appears older, probably from the period of Maništušu (rigid, formal, wavy folds) (Strommenger 1959, p. 37; Amiet 1972, p. 103). Although J. Álvarez-Mon also acknowledges the foreign features—mainly the presence of the sandals—he is again more inclined to the theory of Akkadian inspiration, rather than the result of looting (Álvarez-Mon 2020, p. 281). When the initial origin of the representation is identified by an inscription and differs from the place where it was found, the study is more straightforward. This is the situation presented next.

Figure 7.

Left: Statue of Puzur-Sušinak [Sb 48]. Courtesy of the Musée du Louvre (Raphaël Chipault 2023). Right: Statue of Puzur-Sušinak [Sb 55]. Courtesy of the Musée du Louvre (Raphaël Chipault 2023).

Figure 7.

Left: Statue of Puzur-Sušinak [Sb 48]. Courtesy of the Musée du Louvre (Raphaël Chipault 2023). Right: Statue of Puzur-Sušinak [Sb 55]. Courtesy of the Musée du Louvre (Raphaël Chipault 2023).

2.2.4. Gudea

Statues of Gudea (ruler of Lagaš, ruling between ca 2130–2110 BC) were centralized in Girsu (present-day Tello, Iraq) by Adad-nādin-aḫḫe (Seleucid ruler, from the 3rd century BC). Gudea has passed through history mainly thanks to his large production of statues representing himself (twenty-six in total, whose identification is the subject of current consensus, labelled from A to AA, minus the letter L) (Colbow 1987). Another striking feature is that almost all are manufactured in diorite. In the case of those bearing—and having preserved—an inscription, one understands that they were originally intended to stand in a temple next to a deity (Suter 2000, pp. 57–59). The divinity is not always the same depending on the statue, and the size of the latter can vary considerably. It is therefore quite clear that these statues were not designed to operate together.

However, most of those sculptures, in the round, were discovered grouped in an installation made nineteen centuries after they were produced in Gudea’s time. According to Sebastian Rey, this initiative was part of the Seleucids’ political desire to spread the cult of ancestors (Rey 2020, pp. 78–79). To achieve this, it does not appear to have been necessary to modify the statues or even to add an inscription testifying to the reassignment. Only the rest of the archaeological context made it possible to identify Adad-nādin-aḫḫe.

2.2.5. Akkadian Statuary

Some five hundred years after the demise of the Akkadian Empire (ca 2330 to 2100 BC), representations of 23rd century BC rulers Sargon of Akkad, Rimuš, and Maništušu were still on display. Archaeologically, no evidence of this assemblage has been uncovered. However, texts do tell us that these statues existed in the courtyard of the Ekur (Enlil temple in Nippur). Indeed, Old Babylonian tablets discovered at Nippur (present-day Nuffar, Iraq) are copies of the inscriptions on these Akkadian statues35 installed in the open air (Spycket 1968, pp. 44–45; Gelb and Kienast 1990; Buccellati 1993; Thomason 2005, p. 100). These copies are accompanied by short ekphrasis. Those sources allow us to determine that the function and location of the monuments differed from what they had originally been produced for, as they were assembled in the courtyard of the Ekur as witnesses to a glorious past (Feldman 2009, p. 42)—or to avoid offending the gods (Eppihimer 2019, p. 15). As such, although they were reused in a temple, and perhaps had the status of ex-voto, they fulfilled at the very least the additional function—inevitably attributed to them in a second phase of their existence—of witnesses to the past.

In this situation, we suggest using the term ‘collection’, not in the sense of some sort of museum, which would be a misnomer, but in order to refer to groupings of monuments that were intended to expose traces of the past. The purpose of these ‘collections’ was manifold: to pass on memories, to establish a political tradition, and so on. The practice of collecting has been documented over almost three millennia of Mesopotamian history (Thomason 2005, p. 9). On the other hand, the gathering of statues in a given place is often difficult to distinguish from a purely cultic installation of orants within a temple. Indeed, although difficult to identify, these assemblages may have been used for memorial worship.36

Certainly, in this case in particular, the process of reattribution is vague. What is undeniable is that having survived for almost half a millennium, these artefacts were no longer perceived in the same way as when they were first erected. Although little information has come down to us, mainly because of the lack of associated archaeological remains, there is no doubt that this installation was remodelled over time. However, the impossibility of identifying and quantifying these changes greatly reduces the scope for further study.

This desire to preserve the memory of an original function or context, that is to say of a previous life of the statue, is the major difference from the practice of usurpation. As we have seen, although Šutruk-Naḫḫunte I was most likely responsible for erasing the original inscriptions, he preserved the memory of the sovereign represented via his own dedication. In the case of statues reinstalled in the 1st millennium, such as Puzur-Eštar or Gudea, it is not certain that the memory maintained is specifically that of the sovereign represented, but rather that of the ancestor and what he represents. On the other hand, cases such as that of Puzur-Sušinak—because the reconstruction of its history is complex—do not allow us to clearly identify the motivations.

3. Conclusions

This paper aimed to demonstrate the power of statues through the study of investment in their reworking to make them convey a new message. As a complex artefact, the statue allows stories and ideas to coexist. Their reuse illustrates their capacity to adapt; in addition to the efforts made by societies to change their status or function, there is a belief in their intrinsic malleability. If its context influences the statuary, it also influences its environment.

In addition to reuse, the significance of the image is also evident in other actions carried out on the statues. As we have seen, the effort invested in the deportation reveals the importance attached to the statue by individuals outside the community that produced it. The mutilation of statues, mostly carried out by enemies of the community as well, could also be explored in greater depth (Brandes 1980). It would demonstrate that the opinion of the target community was being considered: there is no need to be convinced of the agency of a statue in order to damage it; it is enough to know that its ‘owner’ will be disempowered when confronted with this violence. When faced with their damaged statues, communities either repair them or get rid of them. However, in both cases, the practice must be codified and supervised—in theory anyway. The mīs pî ritual mentioned in the introduction provides information on the principles to be observed if a divine image is to be repaired or disposed of by returning it to the deities (Walker and Dick 2001, pp. 228–29). Reuse, examined as an isolated phenomenon in this paper, may have been a way of keeping a statue active and within the community that produced it. However, the change of function, or even context, implied by this practice puts it more likely on the enemy side of the statue: an identity is replaced, appropriated, or imposed. As we have seen with cases such as the Gudea corpus (cf. Section 2.2.4) and the statue of Sargon of Akkad restored by Nabonidus (cf. Section 2.2), reuse can sometimes be part of a process of respect and commemoration. As such, while practices can easily be classified as respectful (burial, reparation) or disrespectful (deportation, mutilation), reuse is an isolated case that, depending on the methods and motivations, can slide from one end of the spectrum to the other.

Combining usurpation—as the practice of appropriation of a statue—and reattribution—as the alternative of the coexistence of identities—very few attestations are identified. As we have seen, it may be due to the poor attitude towards reuse; since curse formulas guard against reuse, how wrong was it considered? Furthermore, as far as the actors of these processes are concerned, the new owners faced specific issues as they could not conduct the commission process as a usual one. Indeed, the latter depended on criteria chosen by the previous owner of the image, sometimes long before. As for the sculptor, his role in the documented examples was mainly related to the inscription: to erase and/or add. Were the new owners interested in the statue’s anteriority? What message did the choice to usurp send? As the summary of this special edition points out: ‘Commissioners simultaneously innovated and looked to the past, sometimes with the same social goals in mind’.

In the end, the power of statues, or agency, is also perceptible in their ability to transmit and make explicit the innovations and archaisms of the civilizations in which they evolved, down to the present day.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Laurent Colonna d’Istria and Tobias Hofstetter for their comments, and to Alessio Delli Castelli and François Desset for the discussions related to the themes developed in this article. I would naturally like to thank Kathlyn M. Cooney and Alisée Devillers for their great support. The author is solely responsible for the entire content of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

RIME 2–Frayne, 1993, Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2234–2113 BC); RIME 4–Frayne, 1990, Old Babylonian Period (2003–1595 BC).

Notes

| 1 | Akkadian is rendered in italic lower case, Elamite (=Hatamtite) and Sumerian in straight lower case. However, the latter is rendered in capital letters when it is a logogram in an Akkadian inscription. |

| 2 | Niniveh Mῑs Pî Tablet K 6324+, lines 181–182: anāku ul ēpuš anāku lā […] Ninildu Ea ilu ša nagāri lu […] (Walker and Dick 2001, p. 66). |

| 3 | The sources are still relatively poorly understood as to the possibility that it was also practiced on certain human representations. The textual attestations in this sense are rather understood as representations of deified rulers (Suter 2012, p. 62). |

| 4 | Opening the mouth is a ritual of great importance in many civilizations and eras. First, it should be noted that in Mesopotamia, the opening of the mouth was part of the washing of the mouth, while in Egypt, the opening of the mouth represented the entire rite (Hundley 2015, p. 208). Yet the purpose remains the same: to give life to a statue and ensure its purity and effectiveness. This is a primary objective of many worship practices, up to and including Hinduism (Davis 1997, p. 35), whose Opening of the Eyes is very similar, as demonstrated by Svetla Ilieva (Ilieva 2017). |

| 5 | How statues are dealt with by enemies can also bear witness to their value. In fact, the end of their use can sometimes be imposed by force during a conflict. In this case, practices such as deportation or mutilation are illustrations of the power granted to these artefacts, even outside the context of their production and use. |

| 6 | Depending on the context, as in Simon Connor’s study of Egyptian statuary, reuse and usurpation are synonymous, since both refer only to the reutilization by a new owner (Connor 2020a, p. 83). In the case of Mesopotamia, other types of ‘reuse’ are attested, which is why we propose a specific definition. |

| 7 | The study is the preparation of a PhD dissertation, the aim of which is to understand the significance and evolution of statuary-related practices in Mesopotamian cultures (deportation, mutilation, reuse, abandonment and burial). |

| 8 | One example is an orant from Tutub, dated to the Early Dynastic, whose beard is cleanly chiselled off across his torso, between two strands of hair falling over the front of his shoulders. It is displayed at the Penn Museum under inventory number 37-15-29. |

| 9 | Deportations of divine statues are of particular interest—in fact, it is called ‘godnapping’. Shana Zaia published a synthesis article on the subject in 2015 (Zaia 2015). These cases of deportation differ from those of royal statues, in that the aim is not necessarily to impose authority, but rather it is sometimes presented as a rescue of the divinity. The most famous case is that of the statue of Marduk. According to the textual tradition, the statue was deported four times, leading to its subsequent reuse abroad. First brought to Hatti (present-day Turkey), it was eventually reinstalled in Babylon (present-day Iraq) by an anonymous king (Dalley 1997, pp. 165–66). Then, at the beginning of the 16th century BC, the Hittites seized Babylon and took the statue of Marduk as a spoil to their capital Ḫattusa (present-day Boğazkale, Turkey) (Landsberger 1954, p. 116; Dalley 1997, p. 165). The Prophecy of Marduk refers to a return to Babylon some two hundred years later (Dalley 1997, p. 165). Chronicle P11 recounts a third episode, when Tukulti-Ninurta I (Medio-Assyrian ruler from ca 1243 to 1207 BC) took a statue of Marduk to Assyria. A final episode took place while the aforementioned statue of Marduk was still in Assyria, which shows that there were several of them. Kudur-Naḫḫunte (ruler of Elam, from the 12th century BC) had a statue of Marduk taken to Elam around 1155 BC (Dalley 1997, p. 166). Eventually, the two statues also returned to their city of origin. These divine deportations is very similar to that described in a much more recent time in Egypt in the Ptolemaic Decree of Canopus, which also states that it is the king’s role to recover the divine images carried away by an enemy (Bernand 1988, pp. 44–45; Pfeiffer 2004). |

| 10 | In Egyptology, Scott Morschauer speaks of ‘threat-formulae’, the translation of ‘Drohformeln’, because he considers that although the gods are the most common agents in these formulae, they are not the only ones mentioned, and the king may sometimes be cited instead of the deities (Morschauser 1991, p. xiii). As cuneiform practice refers exclusively to members of the pantheon, it seems that the term curse and its very specific meaning—i.e., a threat involving a divinity—are entirely appropriate in the Mesopotamian context. |

| 11 | This importance of the name is also attested in Egypt. Also, through their presence in curse formulas (Morschauser 1991, pp. 38–70), or even in funeral commemorations. |

| 12 | Author’s translation from German: “Frankfort scheint eine stilistische Nachwirkung aus der vorhergehenden Zeit anzunehmen, wenn er folgendes sagt: ‘In Akkadian works of lesser quality the affinities with the older period are so pronounced that it is sometimes only possible to assign a work to the Akkadian Period because an inscription names the reign in which it was made’. Auch er wendet sich an die Inschrift als letzte Datierungsinstanz, obgleich er die Fremdheitdieses Denkmals innerhalb der Akkadzeit deutlich erkennt.” (Strommenger 1959, p. 34; Frankfort 1955, p. 43). |

| 13 | In ancient Egypt, there was an additional possibility alongside the adaptation of the inscription, namely the modification of the features of the representation. Simon Connor talks of ‘chirurgie esthétique’ to adapt a statue to the iconographic codes of another period (Connor 2020b). This practice is not as well attested in Mesopotamia. One of the main reasons for this is the difference in the size of the sculptures in the round discovered in these two regions. The generally small size of Mesopotamian statues makes them less suitable for features adaptation. |

| 14 | In Egypt, it is, for example, illustrated by the statues unearthed at Tanis (present-day San el-Hagar, Egypt) and testifying to several adaptations combined with deplacements (Hyksos, Ramessides, Third Intermediate Period) (Connor 2020a, pp. 143–44). |

| 15 | When the sole aim behind the reuse is to convey a message about the relationship with the original, it seems just as effective to leave the artefact standing in its original location. Attested on another type of sculpture, for instance, is the case of a bas-relief at Kalḫu (present-day Nimrud, Iraq) where a silhouette was added schematically facing a mutilated image of an Assyrian ruler (Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick Maine, n°1860.3). Although not very detailed, the silhouette headdress identifies it as an Elamite ruler (Porter 2009, p. 220). In this scene, the combination of destruction and addition seem to have been carried out by an enemy group (likely Elamite) with the aim of diminishing the power of the initial representation. Other adaptations of this type have a very different purpose. In the case of a bas-relief (BM 124918) from Nineveh (present-day Kouyunjik, Iraq), the bow and arrow held by the deities have been erased with the simple aim, according to Richard Barnett, of modifying the identity of the individuals depicted. By replacing the bows with small axes, they turned into representations of the gods associated with the Pleiades (Barnett 1976, p. 48). |

| 16 | ‘Šakkanakku’ was the title of the rulers of the city of Mari between the 23rd and 19th centuries BC (Colonna d’Istria 2022, p. 177). |

| 17 | I would like to thank Jakob Salzmann, Assistant Curator in the Department of Antiquities at the Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung, for providing me with information about this artefact. |

| 18 | In 1977, Braun-Holzinger still considered Ešpum [Sb 82], which will be describe later on (cf. Section 2.1.2.), to be a usurpation of an earlier piece (E. A. Braun-Holzinger 1977, p. 18), but in 1991 she stated that: « Der einzige eindeutige Beleg für eine Usurpation einer beschrifteten Statue ist bisher St 79 [Orant 1453 Liebieghaus] mit einer getilgten frühdynastischen une einer darübergesetzten altbabylonischen Weihinschrift. » (E. A. Braun-Holzinger 1991, p. 220) |

| 19 | ‘Kaunakes’ is a woolen garment, particularly recognizable in Mesopotamian art. |

| 20 | Unless it was on the lower part of the statue, which is missing. However, an inscription on the bottom of the garment for a representation of this type is highly unlikely. |

| 21 | Lambert suggests reading the last line: “the year the temple was built” because he finds it unlikely that Ekur would have built a temple (Lambert 1952, p. 61). |

| 22 | Regarding the transcription, G. Marchesi and N. Marchetti use ‘řu2′, but it is equivalent to the more common ‘du3′. |

| 23 | François Thureau-Dangin presents it under inventory number 1326 while Douglas Frayne assigns it number M 7917. |

| 24 | Formerly identified as ‘Nebo’. The initial understanding of the inscriptions was very limited due to its early date of discovery (acquired by the BM in 1854). Furthermore, François Lenormant’s publication erroneously divides the inscriptions into 3 sections: shoulder, back and kidney (Lenormant 1868, pp. 234–35). Except the signs on the back are all concentrated in the middle. Furthermore, AN.PA.x could be a place, or if the reading is dPA.x, it could be the name of a god (Marchesi and Marchetti 2011, p. 168). |

| 25 | Quantifying the total number of statues unearthed in Mesopotamia is difficult, given the fragmentary elements that are impossible to reconstitute, the looting and the large number of sites and excavations. However, as an example, more than two hundred statues and other fragments have been unearthed in the temple zones occupied during the 3rd millennium at two Iraqi sites, Tutub (present-day Khafajah) and Ešnunna (present-day Tell Asmar) (Frankfort 1939, pp. 56–80). |

| 26 | The exact type of the image is unknown. Indeed, the Akkadian word ṣalmum should not systematically be considered as a ‘statue’. Depending on the context, it should be translated as a ‘representation’ (figurative or symbolic) (Durand 2019, pp. 17–18; Guichard 2019, p. 12), ‘image’ (Boden 1998, p. 5), ‘body substitute’ (Bahrani 2003, p. 96), etc. |

| 27 | ‘Kudurrus/narûs’ are stone stelae recording the allocation of land under divine protection. |

| 28 | Transliteration and translation by Laurent Colonna d’Istria via a personal communication (March 2024), based partially on an English translation in (Harper et al. 1992, p. 111), which is a translation of the French version by Françoise Grillot in (Caubet 1994, p. 172). About the title “great likume” see (De Graef 2022, 461 note 303). The aforementioned inscription is not in (König 1965), the reference publication for royal Elamite texts. |

| 29 | Hatamtite is the name proposed to replace Elamite. Elamite is etic, as it is derived from Mesopotamian terminology, while Hatamtite is emic (Desset 2021, p. 2). |

| 30 | According to some studies, other statues have been included in this corpus. However, as the evidence seems too slight, we have not included them in this table. Here is the list, however: A 6415 (Maništušu?), Sb 9098 (Maništušu?), Sb 9147, Sb 10088, Sb 11387, Sb 48 and Sb 55 (cf. Section 2.2.3) (Eppihimer 2010). Moreover, it should also be borne in mind that these deported statues are part of a much larger group of displaced artefacts of various types. There is, for example, a stele of Sargon of Akkad (Sb 1 + Sb 10482 (A 6392) + Sb 11388 (6393) + 1359 + Sb 11387). |

| 31 | Dedicated by a private individual, Šu’āš-takal, for his sovereign Naram-Sîn. |

| 32 | Sb 59 and Sb 163 are sometimes considered as two pieces of a single statue. However, these are two lower parts of a representation and the inscription would be repeated. |

| 33 | Ṣilla-Akka formerly read Milga (Nassouhi 1926, p. 113). Ṣilla-Akka formerly read Milga (Nassouhi 1926, p. 113). |

| 34 | We are relying here on the new Linear Elamite discoveries made by François Desset, Kambiz Tabibzadeh, Matthieu Kervran, Gian Pietro Basello and Gianni Marchesi. As explained in their 2022 article, the ancient reading Puzur-Inšušinak should be replaced by Puzur-Sušinak (Desset et al. 2022, p. 29). |

| 35 | Unfortunately, neither the description nor the copy of the inscription is systematically sufficient to accurately identify the type of artefact. For instance, a Sargon of Akkad inscription (RIME 2.01.01.01) could have been written on a statue…or any artefact that had a base: “inscription on its base” ([colophon, l. 1-2] mu-sa-ra ki-gal-ba). On the other hand, some inscriptions include the word DUL3—which is very likely to be translated as statue in this context–, e.g., Rimuš (RIME 2.01.02.04): “s[ay]s, ‘(This is) my statue’” ([curse formula, 108–109] DUL3-mi-me i-[qa2-bi]-u3) (Buccellati 1993, p. 70). |

| 36 | This practice would be similar to that attested in chapels for the cult of kings at Karnak or Memphis (Gabolde 2016). |

References

- Amiet, Pierre. 1972. Les Statues de Manishtusu, Roi d’Agadé. Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale 66: 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Amiet, Pierre. 1976. Contribution à l’histoire de La Sculpture Archaïque de Suse. Cahiers de La Délégation Archéologique Française En Iran 6: 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Asher-Greve, Julia, and Joan Goodnick Westenholz. 2013. Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 259. Fribourg: Academic Press Fribourg. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Mon, Javier. 2020. The Art of Elam, ca. 4200–525 BC. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrani, Zainab. 1995. Assault and Abduction: The Fate of the Royal Image in the Ancient Near East. Art History 18: 363–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrani, Zainab. 2003. The Graven Image. Representation in Babylonia and Assyria. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, Richard. 1976. Sculptures from the North Palace of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (668–627 BC). London: British Museum Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Belting, Hans. 1993. Likeness and Presence. A History of the Image before the Era of Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernand, André. 1988. Le Statut de l’image Divine Dans l’Égypte Hellénistique. Collection de l’Institut Des Sciences et Techniques de l’Antiquité 367: 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Blocher, Felix. 1999. Wann Wurde Puzur-Eschtar Zum Gott? In Babylon: Focus Mesopotamischer Geschichte, Wiege Früher Gelehrsamkeit, Mythos in Der Moderne. 2. (Internationales Colloquium Der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft, 24.-26. Marz 1998 in Berlin). Edited by Johannes Renger. Berlin: SDV, Saarbrücker, pp. 253–69. [Google Scholar]

- Boden, Peggy Jean. 1998. The Mesopotamian Washing of the Mouth (Mῑs Pî) Ritual. An Examination of Some of the Social and Communication Strategies Which Guided the Development and Performance of the Ritual Which Transferred the Essence of the Deity into Its Temple Statue. Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, Peter. 2010a. Reuse and Restoration. UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Directed by W. Wendrich. Los Angeles. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2vp6065d (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Brand, Peter. 2010b. Usurpation of Monuments. UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Directed by W. Wendrich. Los Angeles. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5gj996k5 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Brandes, Mark. 1980. Destruction et mutilation des statues en Mésopotamie. Akkadica 16: 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Holzinger, Eva Andrea. 1977. Frühdynastische Beterstatuetten. Abhandlungen Der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 19. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Holzinger, Eva Andrea. 1991. Mesopotamische Weihgaben Der Frühdynastischen Bis Altbabylonischen Zeit. Heidelberger Studien Zum Alten Orient 3. Heidelberg: Heidelberger Orientverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Holzinger, Eva. 2007. Das Herrscherbild in Mesopotamien Und Elam: Spätes 4. Bis Frühes 2. Jt. V. Chr. Alter Orient Und Altes Testament 342. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Buccellati, Giorgio. 1993. Through a Tablet Darkly. A Reconstruction of Old Akkadian Monuments Described in Old Babylonian Copies. In The Tablet and the Scroll. Near Eastern Studies in Honor of William W. Hallo. Edited by Mark Cohen, Daniel Snell and David Weisberg. Bethesda: CDL Press, pp. 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caubet, Annie, ed. 1994. La cité royale de Suse: Trésors du proche-orient ancien au Louvre. Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux. [Google Scholar]

- Colbow, Gudrun. 1987. Zur Rundplastik des Gudea von Lagas. Münchener Universitäts-Schriften 5. München: Profil Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Colonna d’Istria, Laurent. 2022. Langue et Écriture Dans La Vallée Du Moyen-Euphrate à La Fin de La Période Des Sakkanakkus de Mari (Seconde Moitié Du 20e et 19e Siècles Av. J.-C.): Quelques Nouvelles Données. In Transfer, Adaption Und Neukonfiguration von Schrift- Und Sprachwissen Im Alten Orient. Edited by Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum and Ingo Schrakamp. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 177–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, Simon. 2018. Mutiler, Tuer, Désactiver Les Images En Égypte Pharaonique. Perspective. Actualités En Histoire de l’art 2: 147–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, Simon. 2020a. Être et Paraître: Statues Royales et Privées de La Fin Du Moyen Empire et de La Deuxième Période Intermédiaire (1850–1550 Av. J.-C.). Middle Kingdom Studies 10. Londres: Golden House Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, Simon. 2020b. ‘Ramessiser’ des statues. Bulletin de la Société Française d’Égyptologie 202: 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Dalley, Stephanie. 1997. tatues of Marduk and the Date of Enūma Eliš. Altorientalische Forschungen 24: 163–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Richard. 1997. Lives of Indian Images. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Graef, Katrien. 2022. The Middle East after the Fall of Ur: From Ešnunna and the Zagros to Susa. In The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume II. Edited by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller and Daniel Potts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 408–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desset, François, Kambiz Tabibzadeh, Matthieu Kervran, Gian Pietro Basello, and Gianni Marchesi. 2022. The Decipherment of Linear Elamite Writing. Zeitschrift Für Assyriologie Und Vorderasiatische Archäologie 112: 11–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desset, François. 2021. Considerations on the History of Writing on the Iranian Plateau (ca. 3500–1850 B.C.). Journal of Archaeology and Archaeometry 1: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, Jean-Marie. 2019. Le Culte Des Bétyles Dans La Documentation Cunéiforme d’époque Amorrite. In Représenter Dieux et Hommes Dans Le Proche-Orient Ancien et Dans La Bible. Edited by Thomas Römer, Hervé Gonzalez and Lionel Marti. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 287. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 15–37. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. 2008. Ein Hammer?! Göttinger Miszellen 216: 99–100. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. 2015. Usurpation. In Joyful in Thebes: Egyptological Studies in Honor of Betsy M. Bryan. Edited by Cooney Kathlyn and Jasnow Richard. Material and Visual Culture of Ancient Egypt 1. London: Lockwood Press, pp. 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Eppihimer, Melissa. 2010. Assembling King and State: The Statues of Manishtushu and the Consolidation of Akkadian Kingship. American Journal of Archaeology 114: 365–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppihimer, Melissa. 2019. Exemplars of Kingship. Art, Tradition, and the Legacy of the Akkadians. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Jean. 2012. The Lives of Sumerian Sculpture: An Archaeology of the Early Dynastic Temple. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, Marian. 2009. Knowledge as Cultural Biography: Lives of Mesopotamian Monuments. Studies in the History of Art 74: 40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Frankfort, Henri. 1939. Sculpture of the Third Millennium B.C. from Tell Asmar and Khafajah. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frankfort, Henri. 1955. The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient. Baltimore: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frayne, Douglas. 1990. Old Babylonian Period (2003–1595 BC). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayne, Douglas. 1993. Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2234–2113 BC). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabolde, Luc. 2016. À l’exemple de Karnak, Une « chambre Des Rois » et Une Cachette de Statues Royales Annexées Au Temple de Ptah à Memphis. In La Cachette de Karnak. Nouvelles Perspectives Sur Les Découvertes de Georges Legrain. Edited by Laurent Coulon. Bibliothèque d’Étude 161. Le Caire: IFAO-Ministry of Antiquities of Egypt, pp. 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Galter, Hannes. 1987. On Beads and Curses. Annual Review of the Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia Project 5: 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gelb, Ignace, and Burkhart Kienast. 1990. Die Altakkadischen Königsinschriften Des Dritten Jahrtausends v. Chr. Freiburger Altorientalische Studien 7. Stuttgart: Steiner Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. New York: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guichard, Michael. 2019. Les Statues Divines et Royales à Mari d’après Les Textes. Journal Asiatique 307: 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Harry, and Leonard Woolley. 1927. Al-’Ubaid. A Report on the Work Carried out at al-’Ubaid for the British Museum in 1919 and for the Joint Expedition in 1922–3. Ur Excavations 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, Prudence. 1994. Les monuments mésopotamiens. In La cité royale de Suse: Trésors du proche-orient ancien au Louvre. Edited by Annie Caubet. Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, pp. 159–82. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, Prudence, Joan Aruz, and Françoise Tallon, eds. 1992. The Royal City of Susa. Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Hauptmann, Ralf. 1989. Die Sumerische Beterstatuette. Liebieghaus Monographie 12. Francfort-sur-le-Main: Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung. [Google Scholar]

- Highcock, Nancy. 2021. The Lives of Inscribed Commemorative Objects: The Transformation of Private Personal Memory in Mesopotamian Temple Contexts. In The Social and Cultural Contexts of Historic Writing Practices. Edited by Philip J. Boyes and M. Philippa. Steele and Natalia Elvira Astoreca. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundley, Michael. 2015. Divine Presence in Ancient Near Eastern Temples. Religion Compass 9: 203–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, Svetla. 2017. Some Parallels Between the Opening of the Mouth Ritual and the Indian Prana Pratistha. In The Journal of Egyptological Studies V. Edited by Sergei Ignatov. Sofia: Bulgarian Institute of Egyptology, pp. 114–131. [Google Scholar]

- Joannès, Francis. 2011. L’écriture Publique Du Pouvoir à Babylone Sous Nabuchodonosor II. In Babylon: Wissenskultur in Orient Und Okzident. Edited by Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum, Margarete Van Ess and Joachim Marzahn. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 113–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, Hermann. 1950. Bericht Über Die von Der Akademie Der Wissenschaften in Wien Auf Gemeinsame Kosten Mit Dr. Wilhelm Pelizaeus Unternommenen Grabungen Auf Dem Friedhof Des Alten Reiches Bei Den Pyramiden von Giza: Das Mittelfeld Des Westfriedhofs. Giza 9. Vienne: Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky. [Google Scholar]

- Klengel-Brandt, Evelyn. 1991. Gab Es Ein Museum in Der Hauptburg Nebukadnezars II. in Babylon? Forschungen Und Berichte 28: 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, Friedrich Wilhelm. 1965. Die elamischen Königsinschriften. Graz: Weidner. [Google Scholar]

- Laboury, Dimitri. 2010. Portrait versus Ideal Image. UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Directed by W. Wendrich. Los Angeles. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9370v0rz (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Lambert, Maurice. 1952. La Période Présargonique. Sumer 8: 55–75, 198–216. [Google Scholar]

- Landsberger, Benno. 1954. Assyrische Königsliste Und ‘Dunkles Zeitalter’. Journal of Cuneiform Studies 8: 106–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenormant, François. 1868. Sur Une Statuette Babylonienne d’albâtre. Revue Archéologique 18: 231–36. [Google Scholar]

- Marchesi, Gianni, and Nicolo Marchetti. 2011. Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia. Mesopotamian Civilizations 14. Winona Lake: Penn State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moortgat-Correns, Ursula. 1986. Einige Bemerkungen Zur ‘Statue Cabane’. In Insight through Images: Studies in Honor of Edith Porada. Edited by Marilyn Kelly-Buccellati, Paolo Matthiae and Maurits Van Loon. Bibliotheca Mesopotamica 21. Malibu: Undena Publications, pp. 183–88. [Google Scholar]

- Morschauser, Scott. 1991. Threat-Formulae in Ancient Egypt: A Study of the History, Structure, and Use of Threats and Curses in Ancient Egypt. Baltimore: Halgo. [Google Scholar]

- Na’aman, Nadav. 1981. The Recycling of a Silver Statue. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 40: 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, Wolfram. 1959. Die Statue Eines Neusumerischen Gottkönigs. Zeitschrift Für Assyriologie Und Vorderasiatische Archäologie 53: 261–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassouhi, Essad. 1926. Statue d’un Dieu de Mari, Vers 2225 Av. J.-C. Archiv Für Orientforschung 3: 109–14. [Google Scholar]

- Parpola, Simo. 1987. The Correspondence of Sargon II, Part I: Letters from Assyria and the West. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parrot, André. 1935. Les Fouilles de Mari: Première Campagne. Syria 16: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, Stefan. 2004. Das Dekret von Kanopos (238 v. Chr.). Kommentar Und Historische Auswertung Eines Dreisprachigen Synodaldekretes Der Ägyptischen Priester Zu Ehren Ptolemaios’ III. Und Seiner Familie. Archives for Papyrus Research and Related Areas: Supplement 18. München: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Barbara. 2009. Noseless in Nimrud: More Figurative Responses to Assyrian Domination. In Of God(s), Trees, Kings, and Scholars: Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola. Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila. Studia Orientalia 106. Helsinki: Eisenbrauns, pp. 201–20. [Google Scholar]

- Radner, Karen. 2005. Die Macht des Namens: Altorientalische Strategien zur Selbsterhaltung. SAATAG 8. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Reade, Julian. 2000. Early Dynastic Statues in the British Museum. Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires 4: 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Reade, Julian. 2002. The Ziggurrat and Temples of Nimrud. Iraq 64: 135–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, Sebastien. 2020. A Seleucid Cult of Sumerian Royal Ancestors in Girsu. In In Context: The Reade Festschrift. Edited by Irving Finkel and St John Simpson. Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology, pp. 56–81. [Google Scholar]

- Slanski, Kathryn E. 2003. The Babylonian Entitlement narus (kudurrus): A Study in Their Form and Function. ASOR Books 9. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Researc. [Google Scholar]

- Spycket, Agnès. 1968. Les statues de culte dans les textes mésopotamiens des origines à la Ire dynastie de Babylone. Cahiers de la revue biblique 9. Paris: Gabalda. [Google Scholar]

- Spycket, Agnès. 1981. La Statuaire Du Proche-Orient Ancien. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Strommenger, Eva. 1959. Statueninschriften Und Ihr Datierungwert. Zeitschrift Für Assyriologie Und Vorderasiatische Archäologie 53: 28–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, Claudia. 2000. Gudea’s Temple Building: The Representation of an Early Mesopotamian Ruler in Text and Image. Cuneiform Monographs 17. Groningen: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Suter, Claudia. 2012. Gudea of Lagash: Iconoclasm or Tooth of Time? In Iconoclasm and text destruction in the ancient Near East and beyond. Edited by May Natalie. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 57–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tallon, Françoise. 1993. Statue Royale Anonyme Provenant Du Temple d’Inshushinak à Suse (Louvre, Sb 48). Studi Micenei Ed Egeo-Anatolici 31: 103–10. [Google Scholar]

- Thomason, Allison. 2005. Luxury and Legitimation: Royal Collecting in Ancient Mesopotamia. Perspectives on Collecting. New York: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Thureau-Dangin, François. 1934. Inscriptions Votives Sur Des Statuettes de Ma’eri. Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale 31: 137–44. [Google Scholar]

- Thureau-Dangin, François. 1939. La statue Cabane. In Mélanges syriens offerts à monsieur René Dussaud. Paris: Geuthner, pp. 157–59. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Christopher, and Michael Dick. 2001. The Induction of the Cult Image in Ancient Mesopotamia: The Mesopotamian Mῑs Pî Ritual. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, Irene. 1992. Idols of the King: Royal Images as Recipients of Ritual Action in Ancient Mesopotamia. Journal of Ritual Studies 6: 13–42. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, Irene. 2009. What/When Is a Portrait? Royal Images of the Ancient Near East. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 153: 254–70. [Google Scholar]