Abstract

This study presents a data driven comparative analysis of the painting industries in sixteenth and seventeenth century Antwerp and Amsterdam. The popular view of the development of these two artistic centers still holds that Antwerp flourished in the sixteenth century and was succeeded by Amsterdam after the former’s recapturing by the Spanish in 1585. However, a demographic analysis of the number of painters active in Antwerp and Amsterdam shows that Antwerp recovered relatively quickly after 1585 and that it remained the leading artistic center in the Low Countries, only to be surpassed by Amsterdam in the 1650’s. An analysis of migration patterns and social networks shows that painters in Antwerp formed a more cohesive group than painters in Amsterdam. As a result, the two cities responded quite differently to internal and external market shocks. Data for this study are taken from ECARTICO, a database and a linked data web resource containing structured biographical data on over 9100 painters working in the Low Countries until circa 1725.

1. Introduction

At an auction in the early autumn of 1637, Rembrandt bought the painting Hero and Leander by Peter Paul Rubens for a little less than 425 guilders. Today, two paintings by Rubens with this subject are known: One in the collection of the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden (Figure 1) and a smaller version of the same painting in the collection of Yale University. From these paintings, we know that the painting bought by Rembrandt depicted a dramatic scene in which the Nereids out of a stormy Hellespont bring ashore the dead body of Leander who drowned during a midnight swim to meet his lover Hero. She is depicted at the right side of the painting, throwing herself into the Hellespont out of devastation over her lover’s death. Prior to being purchased by Rembrandt, the painting had been in the possession of the Amsterdam painter Jan Jansz. Uyl who had given it as collateral to the lawyer Trojan de Magistris. Uyl was no stranger to Rembrandt, who had previously bought a number of works painted by Uyl himself.1 Visiting his workshop, Rembrandt would have become familiar with the Hero and Leander before he had the opportunity to actually purchase it. This might well have been as early as 1633 when Rembrandt painted his own dramatic scene at a dark and stormy sea: The famous—but stolen—Christ in the storm on the lake of Galilee (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Peter Paul Rubens, Hero and Leander, ca. 1608, oil on canvas, Gemäldegalerie Dresden), artwork in the public domain.

Figure 2.

Rembrandt, Christ in the Storm on the Lake of Galilee, 1633, oil on canvas, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (stolen), artwork in the public domain.

Rembrandt admired Rubens. According to Schwartz (2018), he admired him to such a degree that in his early career he was driven by a fierce ambition to equal and to outperform the grand master of ‘Flemish Baroque’. For many who are familiar with seventeenth century Netherlandish art, this might still come as a surprise. After all, there is a large body of literature and critiques in which the two artists and their works are described in antithetical terms: The Roman Catholic versus the Calvinist, the aristocrat versus the miller’s son, grace versus realism, and extravaganza versus introspection. However, as Schwarz also pointed out, this Rubens/Rembrandt dichotomy is largely the product of nineteenth and early-twentieth century nationalist historiography and museology. In the aftermath of Belgium becoming independent of the Netherlands (1830–1839), the new Belgian authorities actively supported the creation of an own national history. In this climate, a series of events and publications around the Rubens Year 1840 (two hundred years after his death) contributed to the appropriation of Rubens as a Belgian national icon (Schwartz 2018; Pil 1993; Wijnsouw 2018). The Dutch, of course, responded by claiming Rembrandt as their national icon. Catalyzed by publications like those by Busken Huet (1879, 1882), this identification of Rubens with Belgium and Rembrandt with the Netherlands quickly became institutionalized in Dutch and Belgian historiography. Even the celebrated Johan Huizinga wrote—without any reservation—that ‘you grasp Rembrandt through the Netherlands, and the Netherlands through Rembrandt’ (Huizinga 1941, p. 150).

Seventeenth century Netherlandish painting and painters would—in terms of classification—suffer the same fate as its most famous artists. Whereas contemporary biographers like Van Mander, De Bie, and Houbraken still spoke about Netherlandish artists indiscriminately, nineteenth century biographers like Kramm started to subdivide them into Dutch and Flemish artists. This practice has continued until today. As a result, the Flemish Baroque painting and Dutch Golden Age painting are almost always studied in separation, as distinct phenomena. However, there are some notable exceptions. Briels (1987, 1997), for instance, demonstrated that many Dutch Golden Age painters were actually of Flemish descent and consequently, he argued, Northern Netherlandish painting was strongly rooted in Flemish traditions. The work of Briels was the onset of a gradual rethinking of the ‘North–South divide’ in the history of seventeenth century Netherlandish art by many scholars. Most explicit in this rethinking were De Clippel and Vermeylen (2015) who called for a more integrative history of Dutch and Flemish art. Their research project Cultural transmission and artistic exchanges in the Low Countries, 1572–1672 yielded a number of studies that highlighted the interconnectedness of painting in the Dutch Republic and the Habsburg Netherlands from various perspectives.

With the present study, we continue in this line of research. Considering the current developments in the historiography of seventeenth century Netherlandish art, the question arises how the painting industries in Antwerp and Amsterdam, the main artistic centers of the Netherlands, actually compared. Were they comparable in size, development, and social structure? To which extent were those industries connected by means of migration? Furthermore, thinking of painting as an industry also allows us to take into account broader spatial and economic developments. This is particularly relevant in the case of Antwerp and Amsterdam, because after 1585 the latter city took over the former’s position as the most important gateway in the Northern European trading system (Lesger 2006). Antwerp’s economy, however, experienced a remarkable revival in the first half of the seventeenth century, a period often referred to as the Indian Summer of Antwerp’s Golden Age.

2. Data

The sharp distinction being made between Dutch and Flemish art is obviously an important reason why a comparative analysis, let alone an integrated analysis of the painting industries of Antwerp and Amsterdam, is still lacking. Another reason is data. What we need for such a comparison is structured data on all the persons involved in this trade, some of their characteristics (occupations, periods of activity, et cetera), and preferably also data on the relations between these persons. Considering that besides Rubens, Rembrandt, and of course Jan Jansz. Uyl, more than 4000 other painters have been active in Antwerp and Amsterdam during this period, one will understand that this is by all means a very tedious task. Nevertheless, we accepted this challenge, and over the past years we have collected such data on a very large portion of the painter populations of Amsterdam and Antwerp in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. These data were structured and stored in a prosopographical database and web resource called ECARTICO.2

ECARTICO has its roots in a research project on history painting in Amsterdam in the mid seventeenth century. While building a research database—which was quite limited in scope—for this project, we were so fortunate that the late Pieter Groenendijk was willing to share his data that were collected to draw up a lexicon of Netherlandish visual artists from ca. 1475 to ca. 1725 (Groenendijk 2008). As a consequence, we were able to build a data set with a much wider scope than originally intended. In consecutive projects, we also added data on book sellers, printers, publishers, sculptors, gold- and silversmiths, and other representatives of the ‘creative industries’. Currently, ECARTICO is being further developed as a central Linked Open Data resource for Golden Agents, a digital research infrastructure for the Dutch Golden Age (Brouwer and Nijboer 2018).

In its design, ECARTICO is being geared toward the aggregation and grouping of biographical data. In this objective, it takes a different approach than documentation systems that are primarily designed for storage and retrieval of single data. Both our data model and our data entry policy are focused on avoiding, for instance, non-standardized input and duplicate entries. In case of uncertainty, this offers less room to leave things open for interpretation by the (human) end user. Choosing data consistency over expressiveness at the level of single facts, however, ensures more reliable results at higher levels of aggregation.

Currently, the database contains biographical data on more than 45,000 persons, of whom more than 9100 are labeled as painters. Unlike traditional art historical resources which are biased toward artists whose works are still known, we also included data on minor artists whose names are only known from written sources. By including all persons who are mentioned as ‘painters’ in written sources, we also included data on painters who may actually have been house painters. That is not just an imperfection to be accepted for the sake of inclusiveness, but rather an acknowledgement of the fact that in the sixteenth and seventeenth Low Countries there was often a gliding scale between minor artists and ordinary house painters (Mund 2005; Bakker 2011).

In the past years, we have extensively corrected the existing data and added many data on the relatives of artists and on visual artists that were not covered by the original Groenendijk data. We have done extensive research on the Amsterdam baptism, marriage, and burial registers in the past years. This has yielded a lot of new data on Amsterdam painters in the Dutch Golden Age. In 2010, we had data on 1010 painters who had been active in Amsterdam in the seventeenth century (Nijboer 2010); at the time of writing, this number has risen to 1744. Unfortunately, the admission ledgers of the Amsterdam guild of Saint Luke have not survived the ravages of time. Regarding Antwerp, however, these lists—although with a few omissions—are still at our disposal, and they were published by Rombouts and Van Lerius (1864). These Liggeren are not completely covered by the ECARTICO database yet. However, current coverage is well over 90%, and data processing on Antwerp painters is steadily proceeding. We expect to have covered the Liggeren and auxiliary resources (e.g., Duverger 1984; Van Hemeldonck 2007) more completely in the course of 2020.

The ECARTICO database is accessible through an online interface. Web users can browse through individual records, but they can also use several tools to visualize and analyze the data. All these tools run directly against the database. In the following section, we use these tools to provide some new insights into the topic under discussion. Keeping in mind that we are dealing with data that are not complete, we provide some provisional statistics on the Antwerp and Amsterdam painter populations in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

3. Counting Painters in Antwerp and Amsterdam

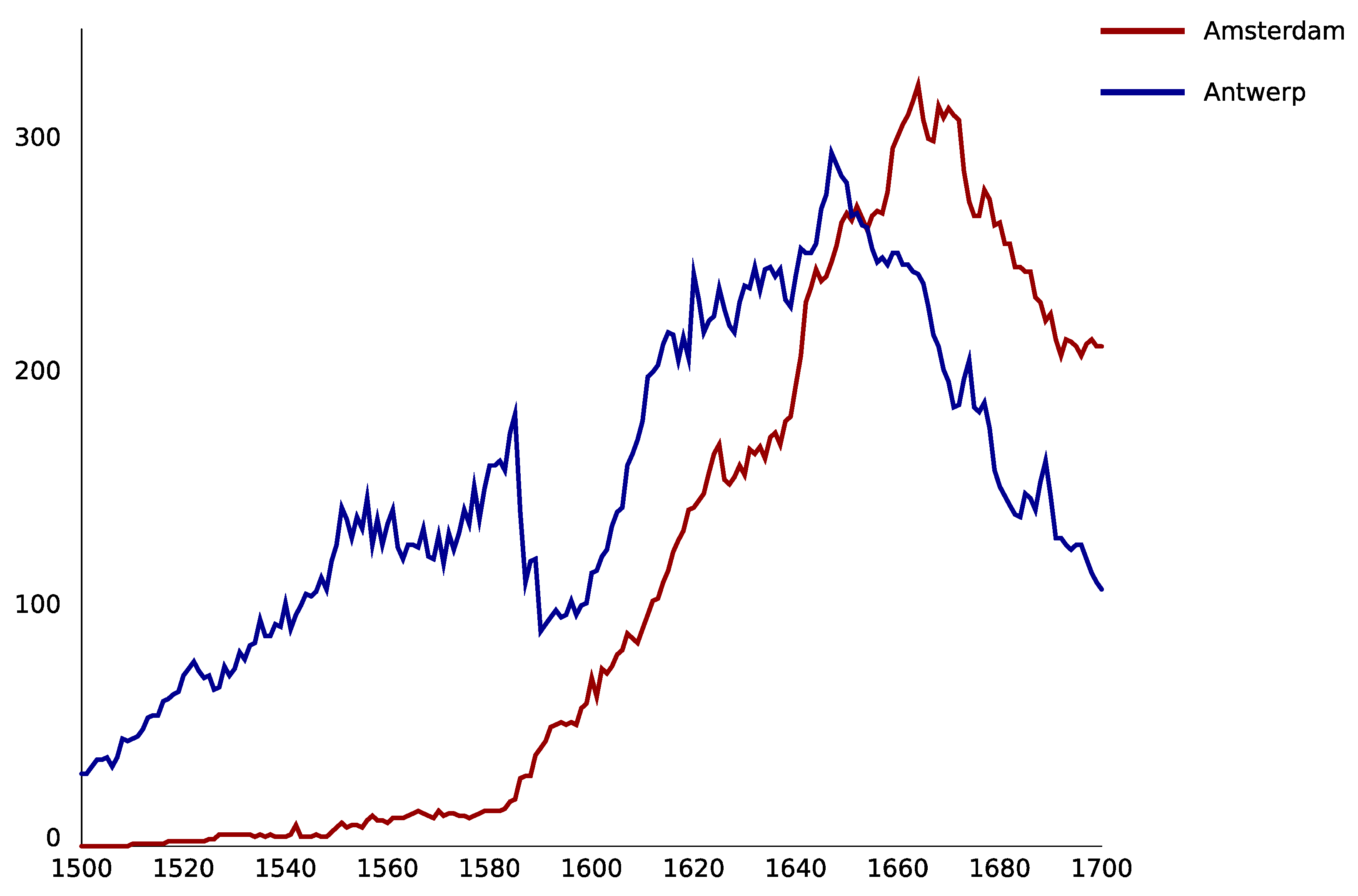

Using the (dated) work locations documented in ECARTICO, we can calculate the total number of painters that were active in a given place for each year. In Figure 3, we have plotted these numbers for Antwerp and Amsterdam between 1500 and 1700. Since we are dealing with incomplete data, these numbers are of course lower boundaries above which the actual population size has to be estimated. The plotted numbers for Antwerp between 1585 and 1590 are expected to be very close to the actual population size because there are two fairly complete lists of guild members for that period and because extensive research has been done on the painter population of that period. Outside of this range, we expect the actual population sizes to be higher than the plotted numbers. Going back further in time, the difference is likely to become more significant.

Figure 3.

Number of painters active in Antwerp and Amsterdam, 1500–1700. Source: ECARTICO, date accessed 10 April 2019.

Notwithstanding that they represent lower boundary estimates of actual population sizes, the curves plotted in Figure 3 reliably reflect the demographic trends of the two painter populations under consideration. Since we are dealing with two finite populations that are already extensively covered by the available data, additional research and data entry will lift the curves but is not likely to significantly alter their shapes.

Until the last two decades of the sixteenth century, the chart does not show a very surprising pattern. While Amsterdam was still an artistic center of modest importance, Antwerp developed into an important market for art while becoming the main commercial metropole north of the Alps (cf. Vermeylen 2003; Martens and Peeters 2006). The only thing that might be surprising is that the data collected so far suggest that the Antwerp painter population stagnated from circa 1550 onward, the more so since we may safely assume that the peak in 1585 can be attributed to the sampling bias described above. We have considered the possibility that this phase of stagnation could reflect a lack of sources, since the Liggeren are very incomplete for the 1560’s. However, if we narrowed the Antwerp painter population to only painters whose works are known, the curve would indicate a similar phase of stagnation, and the 1585 peak would disappear.

Therefore, the stagnation of the Antwerp art market may well have predated the religious, military, and political events and developments that had such a profound effect on artistic life in Antwerp: The rise of Protestantism and the revolt of the Dutch against their ruler, the king of Spain. After the iconoclasm of the 1566 Beeldenstorm and the looting of the city by Spanish troops in 1576, Antwerp took the side of the rebels in their struggle against the king of Spain from 1579 onward. In 1581, Calvinism became the official religion of the town. Antwerp had a good starting position to become the leading city in the independent Dutch Republic. However, on 17 August 1585, after being besieged by Spanish troops for fourteen months, Antwerp surrendered to the Spanish Crown. Protestant inhabitants of Antwerp were offered the choice to reconcile with Catholicism or to leave the city. Many chose the latter option.

Emigration and the fact that very few painters entered the trade in the years following 1585 had a dramatic effect on the Antwerp painter population which decreased in size by about one half. Meanwhile, the Amsterdam painter population rose rapidly in size. Shortly after 1590, the Antwerp and Amsterdam painter populations were almost comparable in size. At the same time, the Antwerp painter population started to grow again and—according to the chart—continued to be larger than that of Amsterdam for six decades. Recalling that much more data have been processed on Amsterdam than on Antwerp, we may safely assume that the latter city stayed ahead of the former until the late 1640′s. Only after 1650 did the Amsterdam painter population surpass that of Antwerp.

The continuing importance of Antwerp compared to Amsterdam between circa 1590 and circa 1650 is one surprising outcome of this time series. Even more remarkable is that the growth of the painter populations in Antwerp and Amsterdam between 1590 and 1620 runs almost perfectly parallel, and between 1620 and 1640 both populations suffered from an almost equal phase of reduced growth. This similarity in development means that both the ‘restoration’ of painting in Antwerp and the ‘rise’ of painting in Amsterdam cannot be explained by focusing on mere local conditions (and specifically local demand) as has been done so far (e.g., Bok 1994; Timmermans 2008; Sluijter 2009; Nijboer 2010). Instead, the pattern discussed here points at a high degree of market integration, something that is also evidenced by the lively trade in Antwerp (and Mechelen) paintings in the Dutch Republic and the frequent travels by Antwerp painters and art dealers to the north (cf. Duverger 1968; Sluijter 2009; Rasterhoff and Vermeylen 2015).

4. Migration

Most historians will agree that the Fall of Antwerp in 1585 was a pivotal event in the shift of the economic focal point of northwestern Europe from Antwerp to Amsterdam. In the years following 1585, about 38,000 people left the city (Briels 1985, p. 80). Briels has argued in several publications (Briels 1971, 1974, 1985, 1987, 1997) that the flux of (mostly) religious refugees was instrumental in the actual relocation of commercial activities, including painting, from the Southern to the Northern Netherlands. Gelderblom (2000), however, has shown that most merchants originating from the Southern Netherlands, who were active in Amsterdam in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, were relatively young when they settled in Amsterdam and that they arrived with modest capital. van der Linden (2015) analyzed the 1584/85 Antwerp painter population and concluded that only a minority of the painters left the city after 1585. Moreover, painters with an established reputation were even more likely to stay, and when they left, they did not go to Amsterdam. Similar reservations with regard to the claims by Briels have been made by Sluijter (2009).

When we take a look at the figures for Amsterdam in the period 1585–1620 (Table 1), we find more ground to be critical about the thesis of Briels. In this period, we have evidence for 321 painters being active in Amsterdam, from whom 61 were born in Antwerp. However, the number of painters that had actually been working in Antwerp prior to settling in Amsterdam was much lower: Only 32 on a total of 321. When we narrow the period under investigation to 1585–1600, Antwerp links become a little more prominent, but even then it is clear that the growth of painting in Amsterdam in the years following 1585 was certainly not the result of the relocation of painter workshops (or to put it in the abstract: Production capacity) from Antwerp to Amsterdam.

Table 1.

Painters in Amsterdam and their relation to Antwerp, 1585–1600 and 1585–1620.

Notwithstanding this conclusion, Antwerp born artists were conspicuously present within the Amsterdam painter population of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century. However, there was a much wider area from which Amsterdam painters were recruited.3 Amsterdam was an immigrant town and remained so for the rest of the seventeenth century. This was in sharp contrast with Antwerp where most artists were natives, as is illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Number of painters in Antwerp and Amsterdam according to place of birth, 1600–1700.

Throughout the seventeenth century, the Amsterdam painting industry was much more open to outsiders than the Antwerp industry. This is also reflected in the degree to which the trade of painting was handed over from father to son (Table 3). The number of painters in Antwerp who were both natives of the city and sons of painters was large in both a relative and absolute sense. This indicates that the Antwerp market for paintings was much more than its Amsterdam counterpart an insider’s market. This implies that both markets were quite different in terms of information asymmetries, market access, and competitiveness, but there is no reason to assume that such differences in market conditions seriously affected the economic performance of the painting industry of one city over the other. More important is the implication that the painting industries of Amsterdam and Antwerp evolved around different stocks of social capital.

Table 3.

Painters that were painters’ sons, Amsterdam and Antwerp, 1600–1700.

Recent contributions to social capital theory state that networks of tight interpersonal relations (bonding social capital) are beneficial to enhancing high levels of mutual trust and the formation of informal institutions that make markets operate smoothly. However, such networks are also susceptible to lock-in effects (situations in which the costs of change are higher than the benefits of change). Networks of loose and outward interpersonal ties (bridging social capital), on the other hand, tend to facilitate innovation and access to new opportunities (Knorringa and Van Staveren 2006; Wang et al. 2016).

When, like in Antwerp, economic and artistic activities are embedded in a local network of strong interpersonal ties, relocating such activities is likely to result in a loss of social capital. That makes insider markets relatively resistant to external shocks, like the Fall of Antwerp, because leaving would simply cost too much (cf. van der Linden 2015). On the other hand, as De Marchi and Van Miegroet (2012) have recently argued, because of the strong kinship ties, the Antwerp art market was also characterized by a tendency toward risk avoidance and rent seeking behavior. As a result, painters in Antwerp were less equipped to deal with internal shocks, like a drop in demand. The heterogeneous and loosely connected painter population of Amsterdam had more and better opportunities for exploring new directions when the market called for change. This might well have been one of the reasons why the Antwerp painter population was surpassed by that of Amsterdam after the market for Netherlandish paintings had reached its summit between circa 1640 and 1650.

5. Conclusions

In this short paper, we have set a first step toward the systematic comparison of the painting industries of Antwerp and Amsterdam in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Using aggregates of the biographical data stored in the ECARTICO database, we have demonstrated that even a rather straightforward analysis of the Antwerp and Amsterdam painter populations yields important new insights into the development of the two most important artistic centers in the Low Countries between 1500 and 1700. By using the same data, we could also provide some new metrics on the impact of migration and on the social cohesion of both populations.

To summarize our most important findings:

- The Antwerp painting industry recovered quickly after 1585, and Antwerp continued to be the leading center of painting in the Low Countries until the late 1640s.

- The Amsterdam painting industry grew parallel to that of Antwerp between 1600 and 1640. This might indicate that the painting industry in Amsterdam was still in many ways dependent on Antwerp as the main center for the production and distribution of paintings in the Low Countries.

- The migration of painters from Antwerp to Amsterdam after 1585 did not involve a large relocation of established production capacity.

- The Antwerp painter population formed, as compared to Amsterdam, a rather cohesive social group. This strong cohesion might explain why the Antwerp painting industry quickly recovered after 1585. On the other hand, the relative weak cohesion of the Amsterdam painter population might explain why Amsterdam painters were better equipped to deal with the changing market conditions after 1640.

At a methodological level, we have demonstrated in this paper that datasets with structured biographical data can be used to map the development and social structure of industries, and that as a consequence the research potential of such data collections goes beyond the retrieval of single data. We acknowledge that data quality, both in terms of accuracy and coverage, is a serious issue when using data in such a manner. A more inclusive data collection strategy is definitely needed to overcome the bias induced by the biographer’s gaze in traditional biographical resources. On the other hand, we should not be too afraid of incomplete data either. As always in the statistical analysis of economic or social data, one should be aware that incomplete or inconclusive data may undermine the value of outcomes at the level of absolute numbers at a given point in time. However, our main concern has been long term trends and changes over time. In this respect, even incomplete data sets may reveal patterns that are unlikely to change after additional data entry. Moreover, even provisional results can guide us into further research and data collection.

In future papers, we will explore other methods and techniques to deal with the very rich data that are already present in ECARTICO. Meanwhile, we will continue to review, update, enhance, and expand our data. More data on basic biographic properties like life dates, places of birth, and places of death, especially for the Antwerp painter population, would help to strengthen or weaken the conclusions reached in this paper. Future research should, of course, include other towns as well. Furthermore, it would be interesting to investigate whether other creative industries in Antwerp and Amsterdam like printmaking, gold- and silversmithery, and the book trade developed in a similar way as the painting industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization H.N., M.J.B., and J.B.; methodology, H.N.; software, H.N.; validation, H.N., M.J.B., and J.B.; data curation, H.N., M.J.B. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, H.N.; writing—review and editing, H.N., M.J.B. and J.B.; funding acquisition, M.J.B.

Funding

This research was funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO), grant number 360-55-050 and grant number 380-98-003.

Acknowledgments

The Golden Agents program is sponsored by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) and is a collaboration between Huygens ING, the Meertens Institute, the University of Amsterdam, Utrecht University, VU University Amsterdam, the Rijksmuseum, KB National Library of the Netherlands, the Amsterdam City Archives, the RKD Netherlands Institute for Art History, and Lab1100. Furthermore, the authors wish to express their gratitude to Anne-Rieke van Schaik for her assistance in preparing data on Antwerp painters.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bakker, Piet. 2011. Crisis? Welke crisis? Kanttekeningen bij het economisch verval van de schilderkunst in Leiden na 1660. De Zeventiende Eeuw 27: 232–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bok, Marten Jan. 1994. Vraag en Aanbod op de Nederlandse kunstmarkt, 1580–1700. Ph.D. thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Briels, Jan. 1971. Zuidnederlandse goud- en zilversmeden in Noordnederland omstreeks 1576–1625. Bijdrage tot de kennis van de Zuidnederlandse immigratie. Bijdragen tot de geschiedenis 54: 87–147. [Google Scholar]

- Briels, Jan. 1974. Zuidnederlandse Boekdrukkers en Boekverkopers in de Republiek der Verenigde Nederlanden Omstreeks 1570–1630. Nieuwkoop: De Graaf. [Google Scholar]

- Briels, Johannes Gerardus Carolus Antonius. 1985. Zuid-Nederlanders in de Republiek 1572–1630: Een Demografische en Cultuurhistorische Studie. Sint Niklaas: Danthe. [Google Scholar]

- Briels, Jan. 1987. Vlaamse Schilders in de Noordelijke Nederlanden in het Begin van de Gouden Eeuw 1585–1630. Haarlem: Becht/Gottmer. Antwerpen: Mercator. [Google Scholar]

- Briels, Jan. 1997. Vlaamse schilders en de dageraad van Hollands Gouden Eeuw, 1585–1630, met biografieën als bijlage. Antwerpen: Mefrcatorfonds. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer, Judith, and Harm Nijboer. 2018. Golden Agents. A web of linked biographical data for the Dutch Golden. Paper presented at Second Conference on Biographical Data in a Digital World 2017, Linz, Austria, November 6–7; pp. 33–38. Available online: http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2119/paper6.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- Busken Huet, Conrad. 1879. Het Land van Rubens: Belgische Reisherinneringen. Amsterdam: J.C. Loman jr. [Google Scholar]

- Busken Huet, Conrad. 1882. Het land van Rembrand. Studiën over de Noordnederlandsche beschaving in de zeventiende eeuw. 2 vols. Haarlem: H.D. Tjeenk Willink. [Google Scholar]

- De Clippel, Karolien, and Filip Vermeylen. 2015. In search of Netherlandish art. Cultural transmission and artistic exchanges in the Low Countries, an introduction. De Zeventiende Eeuw. Cultuur in de Nederlanden in interdisciplinair perspectief 31: 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, Neil, and Hans J. Van Miegroet. 2012. Uncertainty, Family Ties and Derivative Painting in Seventeenth-Century Antwerp. In Family Ties. On Art Production, Kinship Patterns and Connections 1600–1800. Edited by Koen Brosens, Leen Kelchtermans and Katlijne Van der Stighelen. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Duverger, Erik. 1968. Bronnen voor de geschiedenis van de artistieke betrekkingen tussen Antwerpen en de Noordelijke Nederlanden tussen 1632 en 1648. In Miscellanea Jozef Duverger. Bijdragen tot de kunstgeschiedenis der Nederlanden. Gent: Vereniging voor de geschiedenis der textielkunsten, vol. I, pp. 337–73. [Google Scholar]

- Duverger, Erik. 1984. Antwerpse kunstinventarissen uit de zeventiende eeuw. 14 vols. [Fontes historiae artis Neerlandicae/Bronnen voor de kunstgeschiedenis van de Nederlanden 1–14]. Brussel: Koninklijke Academie voor Wetenschappen, Letteren en Schone Kunsten van België/Paleis der Academiën. [Google Scholar]

- Gelderblom, Oscar. 2000. Zuid-Nederlandse kooplieden en de opkomst van de Amsterdamse stapelmarkt (1578–1630). Hilversum: Verloren. [Google Scholar]

- Groenendijk, Pieter. 2008. Beknopt biografisch lexicon van Zuid- en Noord-Nederlandse schilders, graveurs, glasschilders, tapijtwevers et cetera van ca. 1350 tot ca. 1720. Leiden: Primavera. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga, Johan. 1941. Nederland’s beschaving in de zeventiende eeuw, een schets. Haarlem: Tjeenk Willink. [Google Scholar]

- Knorringa, Peter, and Irene Van Staveren. 2006. Social Capital for Industrial Development: Operationalizing the Concept. Vienna: United Nations Industrial Development Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Lesger, Clé. 2006. The Rise of the Amsterdam Market and Information Exchange. Merchants, Commercial Expansion and Change in the Spatial Economy of the Low Countries, c. 1550–1630. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, Max, and Natasja Peeters. 2006. Artists by numbers. Quantifying artists’ trades in sixteenth-century Antwerp. In Making and Marketing. Studies of the Painting Process in fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Netherlandish Workshops. Edited by Molly Faries. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Mund, Hélène. 2005. Schilderen op Doek: Een Miskende activiteit van de Vlaamse Primitieven. Vlaanderen 54: 136–40. Available online: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_vla016200501_01/_vla016200501_01_0025.php (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- Nijboer, Harm. 2010. ’Een bloeitijd als crisis. Over de Hollandse schilderkunst in de 17de eeuw. Holland 42: 193–205. Available online: http://www.tijdschriftholland.nl/wp-content/uploads/2010_3_Nijboer.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- Pil, Lut. 1993. De metropool herzien. De creatie van een Gouden Eeuw. In Antwerpen, verhaal van een Metropool. Edited by Jan Van der Stock. Antwerpen: Snoeck-Decaju & Zoon, pp. 129–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rasterhoff, Claartje, and Filip Vermeylen. 2015. Mediators of trade and taste. Dealing with demand and quality uncertainty in the international art markets of the seventeenth century. De Zeventiende Eeuw. Cultuur in de Nederlanden in Interdisciplinair Perspectief 31: 138–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombouts, Philippe-Félix, and Théodore François Xavier Van Lerius. 1864. De Liggeren en andere historische archieven der Antwerpsche Sint Lucasgilde onder de zinspreuk: Wt ionsten versaemt. 2 vols. Antwerpen: Baggerman. Gravenhage: Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Gary. 2018. Rubens in Holland, Rembrandt in Flanders. The Low Countries: Arts and Society in Flanders and the Netherlands 26: 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sluijter, Eric Jan. 2009. On Brabant Rubbish, Economic Competition, Artistic Rivalry, and the Growth of the Market for Paintings in the First Decades of the Seventeenth Century. Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 1: 112–43. Available online: https://www.jhna.org/index.php/past-issues/volume-1-issue-2/109-on-brabant-rubbish (accessed on 16 January 2019). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Timmermans, Bert. 2008. Patronen van patronage in het zeventiende-eeuwse Antwerpen. Een elite als actor binnen een kunstwereld. Amsterdam: Aksant. [Google Scholar]

- van der Linden, David. 2015. Coping with crisis. Career strategies of Antwerp painters after 1585. De Zeventiende Eeuw. Cultuur in de Nederlanden in Interdisciplinair Perspectief 31: 18–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eeghen, Isabella Henriette. 1977. Jan Jansz Uyl en Rembrandt als “tamme eend”. Maandblad Amstelodamum 64: 123–26. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hemeldonck, Godelieve. 2007. Kunst en kunstenaars. Antwerpen: Felixarchief. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeylen, Filip. 2003. Painting for the Market: Commercialization of Art in Antwerp’s Golden Age. Studies in European Urban History (1100–1800) 2. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jenn-Hwan, Tsung-Yuan Chen, and Ray-May Hsung. 2016. Introduction: Guanxi matters? Rethinking social capital and entrepreneurship in Greater China. In Rethinking Social Capital and Entrepreneurship in Greater China: Is Guanxi Still Important? Edited by Jenn-Hwan Wang and Ray-May Hsung. London: Routledge, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wijnsouw, Jana. 2018. National Identity and Nineteenth-Century Franco-Belgian Sculpture. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The documents concerning Rembrandt buying the Rubens painting and his relation to Jan Jansz. Uyl are discussed by van Eeghen (1977). She suggests that Rembrandt participated as a shill bidder at the auction and might not have bought the painting on purpose. However, she fails to explain how this would make sense. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | See also the zoomable map on: http://www.vondel.humanities.uva.nl/ecartico/analysis/?task=origin. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).