1. Background

This paper stems from a collaboration called “Symmetries of the Mind”, with Klinik und Rehabilitationszentrum Lippoldsberg, located in the Wahlsburg area of central Germany. The clinic specializes in the rehabilitation of stroke patients and is situated on the grounds of a former Nazi bomb factory in the forest near the village of Lippoldsberg. The aim of this collaborative project has been, broadly speaking, to bring artistic practices to a therapeutic context by (a) enlarging and expanding the potential for healing beyond the boundaries of established therapies and, conversely, (b) broadening the scope of what one would consider to be an artwork or art process. More specifically, this project aims to bring the tools of contemporary art, in collaboration with science, towards the improvement of function in stroke patients via multisensory stimulation, including the use of a machine learning interface. This is intended to encourage the formation of novel neural connections and thus encourage the formation of alternate, functional connectivity, bypassing the connections damaged by stroke.

As psychiatrist

Joseph Michaels (

1935) noted, in his paper in the

Journal of Orthopsychiatry, upon visiting Hans Asperger’s clinic in Austria: “In this age of ‘technocracy’ with its over-emphasis on technical procedures, it is rather unusual to find a highly personal approach characterized by an appreciable absence of what are ordinarily regarded as rigid methods, apparatus, statistics, formulae and slogans… great value is placed on intuition.” Accordingly, the approach of this paper, which involves art practices in a medical context, makes use of intuitive and creative approaches to healing that may not fit neatly into the standard methods of a medical paper.

This project was initiated in early 2019 by the clinic director Dr. Ralf Pinnau and has been conceptualized under the title of

Clinic Parcours by international curators Christoph Platz and Henriette Gallus. “Parcours” is French for “route” or “course”. Two other artists, apart from Marcos Lutyens, have been invited to participate: Imogen Stidworthy of the United Kingdom and Peter Schloss of Germany. They are working towards an exhibition for late spring 2021. This type of collaboration between art and medicine recalls other collaborations between art and science such as the embedding of artists James Turrell and Robert Irwin with the Garrett Corporation, facilitated by the L.A. County Museum of Art’s Art & Technology program, through which they worked with psychologist Ed Wortz in 1969. By bringing scientists and artists together, new lines of research may be created. Indeed, in the case of Turrell and Irwin, research on the properties of anechoic chambers were later applied to the artists’ works (

Cateforis et al. 2019). Conversely, artists have also contributed to scientific advances, such as William Brockedon, inventor of the first pill-making machine. Indeed, the division between art and science has historically been a porous one (

Wilkinson et al. 1971).

2. Art and Science in Therapy

The focus of Lutyens’ (the primary investigator) work is consciousness, which he has researched extensively through various means that are described below. Human consciousness remains poorly understood from nearly every perspective, whether investigated by philosophers, psychologists, or neuroscientists, as highlighted by cognitive scientist

David Chalmers (

1995), with what he termed “The Hard Problem of Consciousness”. For this reason, Lutyens has turned to less well-established processes and methods: experimenting with groups of synesthetes, exploring the power of suggestion through collective and individual hypnosis, and mediating and promoting shamanic experiences. Lutyens combines these with more conventional methods such as conducting and analyzing online and physical surveys.

Lutyens’ art endeavors have often been interwoven with healing practices, and indeed, his interest in consciousness has led him to explore not just the creative aspects of the mind, but also that of illness and healing. This approach is part of a long trajectory of healing and art being interlinked, dating back not only to hunter–gatherer societies (

Whitley and Hays-Gilpin 2008, p. 44), but also much more recently with the development of creative arts therapies, which can include the use of art, music, psychodrama, and dance within a therapeutic context to promote healing in hospitals, clinics, and independent practitioner’s studios (

Landgarten 1981). To give one example among many, UCLA ran a program called “Art that Heals”, which was designed to help patients to cope with the stresses related to being hospitalized through making art (

Breslow 1993).

Medicine and science have historically been intertwined; Lutyens was drawn to shamanic healing practices as early as age seventeen in the Amazon rainforest of Ecuador and explored it more closely after his twenties, with special interest in those of the Huichol, originally known as the Wixarika, a tribe in the Western Sierra Madre of Mexico. The healing process they use involves the application of medicinal plants (

Valdivia-Correa et al. 2016) as well as the hallucinogenic cactus, peyote (Lophophora Williamsii), for psycho-spiritual rituals.

Figure 1 shows a Huichol Shaman conducting a healing ritual for participants in a pilgrimage to the mountains of the Western Sierra Madre, Mexico. What stood out to Lutyens was how in these traditions, unlike in Western/European medicine, the body, the mind, and the spirit were all considered to be linked and extended seamlessly into nature. This contains, in its intuitive way, the notion that healing needs a strong psycho-somatic basis and that one cannot rely solely on surgery and pharmaceutical drugs to heal. Furthermore, in the West, the ancient role of the shaman has been divided into three practices: (a) the doctor, who looks after the body as a bio-mechanical object, (b) the priest, who looks after the spirit, often in the context of a political matrix, and (c) the artist, who is often relegated to a kind of creative decorator (

La Barre 1979, p. 7). However, recently the idea of integrating psychedelics back into medicine has been gaining traction, particularly in the cases of PTSD or hospice care, and has attracted mainstream attention through the growth of the wellness industry and, most recently, through the bestselling book

How to Change Your Mind by

Michael Pollan (

2018).

Following these shamanic initiations, Lutyens became intrigued by hypnotherapy as a way of accessing altered states of consciousness, as well as its healing potential to help reverse negative habits, as is used in treating addictions or to enhance existing mental or physical attributes. A hypnotherapist has been defined in the Federal Dictionary of Occupational Titles as a professional who “Induces hypnotic state in client to increase motivation or alter behavior patterns: Consults with client to determine nature of problem. Prepares client to enter hypnotic state by explaining how hypnosis works and what client will experience. Tests subject to determine degree of physical and emotional suggestibility. Induces hypnotic state in client, using individualized methods and techniques of hypnosis based on interpretation of test results and analysis of client’s problem. May train client in self-hypnosis conditioning” (

U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Administrative Law Judges 1977, p. 64). Lutyens studied at the now defunct American Institute of Hypnotherapy and began to work with patients struggling with addictions as well as other physical or mental issues.

The most challenging endeavor of the time, relating to the use of hypnotherapy by Lutyens, was working with Los Angeles “at-risk youth” in 1998 through the HeArt Project (now artworxLA), founded by Cynthia Campoy-Brophy. The project, called Blown Away, comprised hypnosis sessions that reframed fear and past trauma, which was often related to first-hand experience of gang violence. The participants re-lived experiences during hypnosis and then translated those experiences into prayer flags that were silk-screened at Self Help Graphics, a non-profit art collective in East Los Angeles. In 2001, the flags were shown at the Armory Center in Pasadena, as well as at the Southern California School of Architecture and the World Festival of Sacred Music hosted by the UCLA Center for Intercultural Performance and the Dalai Lama. The journey for the students from the hypnotherapy sessions to the creation of the flags to their display and sharing with the community was a process devised by Lutyens to turn an internal trauma into a shared and open gesture of healing.

Two years later and extending his research into trauma and art, Lutyens worked on an exhibition at Susanne Vielmetter Gallery in 2003 called “Esomotive”, which sought to psychologically restore the missing arm of celebrity drummer Rick Allen of British rock group Def Leppard. Despite losing his arm in a car accident (

Wilkening 2014), Allen continued drumming successfully in the band. It seemed that he had managed to remap the functioning of his lost arm onto his remaining three limbs, although he still suffered physically and mentally from the loss. Through hypnotherapy sessions together, Lutyens sought to aid him in re-imagining his phantom limb in such a way that he would re-integrate the lost side of himself. The hypnotic ideation sought to convert his loss into a physical thought form, which for Allen took the form of a reptilian, amphibious vehicle. In

Figure 2, Lutyens pictures the imagined shape as taking form in Allen’s mind in this superimposed photograph of him and a 3D printed model of the thought-form, which was fabricated following his description.

A decade later, and extending his research into the relationship between inner states of mind, the body, and the senses, Lutyens worked on a project at the 14th Istanbul Biennial, which charted the emotional response of thousands of biennial visitors to shape and color, in collaboration with the neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran. Together with curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, they brought Ramachandran’s famous “mirror box” (

Figure 3) to the Istanbul Museum of Modern Art. Ramachandran invented the Mirror Box for healing the “phantom limb” syndrome, a condition in which a missing or amputated limb causes pain where the missing limb would be (

The Last Psychiatrist 2009). The patient inserts her existing hand into one side of the box, and her missing hand seems to appear in the other side of the box. By moving the existing hand, the patient has a sense that her missing hand can be reactivated and thus diminishes the pain related to the loss. Lutyens was inspired by this simple tool to explore how symmetry and the use of mirrors could be expanded as a device not just in art but also as it relates to therapy, particularly in its ability to create a sense of completion in the psyche through duplication or even multiplicity.

As an extension of the Mirror Box display, Lutyens and Ramachandran conducted a collaborative survey in the museum near where the box was exhibited. The survey was designed as a mental mirror held up to Biennial visitors that helped better sense which groups of people, in terms of age and sex, were more attuned to a correlation between shape, color, and emotion. From a cultural standpoint, the goal was to reverse the usual exhibition dynamic in which a visitor looks at what is on display at the museum, and instead, the artist reverses the direction of observation by observing the visitor. From a neuroscientific point of view, this was an opportunity to study variations in a cross section of the general public’s understanding of shapes and forms as they relate to emotions. Both of these dynamics could then be fed back into the way museums plan their content to be more attuned to their general public.

These experiments between art and therapy were in part inspired by Chilean-French filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky’s book,

PsychoMagic: The Transformative Power of Shamanic Psychotherapy, which describes how prescribed ritualized activities helped heal subjects who came to him for psychological help (

Jodorowsky 2010). His process was akin to waking people up from a misconstructed world view. As Jodorowsky explains, “Birds born in a cage think flying is an illness” (

Jodorowsky 1973). Another inspiration was Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater’s book

Thought Forms (

Besant and Leadbeater [1901] 1975), which sought to describe how thoughts should be considered to be objects and in this way help to externalize blocked mental states (

Besterman 1934).

As a development of this past research in Istanbul,

Lutyens’ (

2015) work exploring fear and trauma in the context of hypnosis was included in the Salon Suisse of the 57th Venice Biennial in 2017 by invitation of Dakar-based curator Koyo Kouoh. Lutyens created a performance titled

Phobophobia, meaning “the fear of fear”, which sought to isolate the location of fear in the body through hypnosis and expel it through a cathartic process centered around an expectancy violation. This was done by smashing what appeared to be a helium-filled balloon that had been tied around a participant’s wrist with a hammer, revealing the balloon to be made of glass (

Figure 4). The idea behind this process is that the mind is often tied to pre-existing ideas surrounding challenges and illness, especially chronic ailments, and a self-fulfilling dynamic develops, making the situation worse over time. As Rollo May described in his book

The Meaning of Anxiety, “fear ordinarily does not lead to illness if the organism can flee successfully. If the individual cannot flee, but is forced to remain in a conflict situation which cannot be resolved, fear may turn into anxiety and psychosomatic changes may then accompany anxiety” (

May 2015, p. 69). When the mind is unexpectedly confronted with a dynamic that contradicts previous experience, it may be freed from its expectations, or conflicts, and be able to reverse fixed ideas, including ones about the state of one’s health.

3. Applications to Stroke Therapy: The Symmetrical Brain

The application of art-related approaches to therapies dealing with fear and physical trauma, formed a jumping off point for Lutyens to investigate art-based treatments for stroke patients. Art and music therapy have long been used in the treatment of stroke patients. In terms of music, treatments that are based in the understanding of hemispheric lateralization have successful outcomes (

Purdie 1997). Lutyens has witnessed the Lippoldsberg clinic encourage some stroke patients to engage in singing therapy. In terms of art therapy geared towards stroke, studies have shown that art making (see

Figure 5) can help in stroke recovery, such as by focusing attention and motor skills, as well as promoting social interaction and emotional expression (

Reynolds 2012).

When invited to Lippoldsberg, which specializes in stroke therapy, for

Clinic Parcours, Lutyens’ previous experiences meshed well with ongoing studies at the center. One of the main stroke symptoms that the clinic prides itself in treating is that of hemispatial neglect (

Li and Malhotra 2015). This is a condition suffered by 80% of stroke patients, which does not just manifest as the paralysis of the body or just parts such as the right arm or right leg (depending on the location and extent of the brain lesion), but also has the curious effect of preventing the patient from being aware of a corresponding area of their environment, as shown in

Figure 6.

A patient with hemispatial neglect will completely ignore what is on the neglected side of their body and, even curiouser, have no awareness of its absence, a condition called anosognosia. A clock, for instance, may be understood by a stroke patient to be half a clock, with all the numbers from 1 to 12 appearing to be jammed into the non-neglected side. To help combat the kind of magnetized attention to one side, tests using numbers are designed to draw the patient’s attention across to the neglected side of their vision (see

Figure 7).

Previous to his work at Lippoldsberg, Lutyens was intrigued by stimulating both sides of the brain in healthy people as part of his art practice, as in the case of his

Ambidelious project, part of the “Intuition” exhibition at the Palazzo Fortuny, Venice in 2017 (curated by Axel Vervoordt and Daniela Ferretti and with the close curatorial support of Davide Daninos). Lutyens worked with visitors of the exhibition and guided them into a state of trance as they were seated in a circle of 17th-century chairs. Lutyens fed them two different narratives, one into each side of their brain, by means of a hypnotic induction that he performed focusing first on one side of the body and then on the other. When in a trance state, it is easy to associate a narrative with one side of the body (

Figure 8). Lutyens would anchor a narrative in the left hand while signaling the left ear to be especially receptive. This narrative then presumably landed in the right brain hemisphere due to the cross-over of the nervous system from one side of the body to the opposite side of the brain. Lutyens then asked participants, still in an unconscious state, to draw into soft clay tablets positioned on either side of them with a bronze stylus in each hand.

Impressively, participants drew with fluidity—many people drew with both hands at the same time, regardless of which one was supposedly dominant, each hand appearing to express a different emotion. Lutyens hoped that this “artistic therapy” would reconnect different centers of the brain, under siege by constant electronic distractions and overspecialization at work (

Cytowic 2019). It is important to note that this project was not conducted in a medical or hospital context with brain monitoring devices, but nevertheless, following the cues of Hans Asperger’s approach, it used a process of interaction with the visitors to learn of possible cues for stimulating the mind in unexpected ways. Many visitors to the performance reported that they had been in some way “transformed”, while others experienced moving moments of catharsis accompanied by uncontrollable tears, as though some mental blockage had been removed from one or both of the brain hemispheres.

Italian conceptual artist Alighiero e Boetti, whose work was included in the same exhibition and whose pseudonym translates as Alighiero

and Boetti suggesting doubled or split identity, also experimented with this mirrored use of hands. He said that to write with your left hand is like drawing. Of the process of using both hands, he stated, “To write is to draw. Whenever I write, I always use my left hand. My left hand is not able to write: when you see the results you can feel my physical pain; but to me to write is in first instance a great pleasure” (

Catrìona 2012). In other words, the act of writing with both hands created a positive and perhaps healing dynamic for him.

An additional project involving the relation between physical and neurological symmetry was the cabin Lutyens designed, as part of a 2012 work titled

Hypnotic Show in collaboration with Raimundas Malašauskas, built for dOCUMENTA (13) (

Documenta n.d.) in Kassel, Germany. The cabin (

Figure 9) was the site of 340 hypnosis performances that Lutyens conducted and which took place throughout a period of 100 days. Over 7000 visitors passed through, and apart from being a cultural experience in terms of the visitors experiencing 4096 possible narratives delivered through hypnosis, it also appeared to be a kind of healing experience to the people of Kassel, so much so that it was reported in the local press that Lutyens would “mentally clean people’s desktops” (

Von Fraschel 2012).

It also became apparent that certain medical conditions may have benefited from these performances, as in the case of Hans Ellis, who has Parkinson’s disease and diabetes and who later reported that his symptoms had diminished. After the session, he wrote, “in the second session, my Parkinson’s rigor dissolved almost entirely, how wonderful!”

2 His rigor diminished greatly, so much so, that he came back repeatedly for more sessions, bringing with him friends with similar health issues. It must be emphasized that this project was not conducted as a medical trial but, rather, as an art project, so the authors are relying on personal reporting from visitors as well as impressions received over the course of the project.

Born in the art world, the project is now morphing into a therapeutic tool. The cabin is now being rebuilt at the Klinik und Rehabilitationszentrum Lippoldsberg. The particularly important aspect of the cabin, in the context of stroke, is that it is symmetrical along a horizontal axis—the top part of the cabin, including doors, windows, chimney place, lamp are repeated upside-down, into the ground, to give an initial impression that the cabin has a mirror for a floor. This creates an ‘expectancy violation’ (

Burgoon 2015) resulting from the inability to register whether the cabin has a mirrored floor or not, creating a jolt in terms of the viewer’s usual reasoning and expectations. Perhaps this kind of environment, over time, could promote neuroplasticity, contributing to its apparent therapeutic impact.

Mirrors, or the appearance of them, have been much used in art, such as with Yayoi Kusama’s infinity mirrored rooms, which give a sense of awe and disorientation. Kusama herself is an artist who has verged on the edge of mental illness and suicide (

Kusama 2005), so perhaps these mirrored spaces are a tool to quiet the chattering mind, just as they have been used in therapeutic contexts to calm and to encourage self-care as well as self-acceptance (

Freysteinson 2009).

Mirrors are an ideal healing tool to overcome hemispheric neglect in stroke patients, and today, we see Ramachandran’s mirror box being used not just with phantom limb syndrome, but in stroke therapy. In the case of the cabin, the reflection is further disorienting because it is horizontal rather than vertical, but the fact that this idea of symmetry is witnessed in such an unexpected manner may break down the resistance that patients have to acknowledging their “lost” half. This mechanism would be particularly useful, as one acknowledges that a space or object has horizontal symmetry, and as the head tilts to one side, the horizontal symmetry becomes vertical symmetry, and the mind is forced to acknowledge awareness of its missing side.

4. Multisensory Stimulation: The Kaleidoscopic Mind

In the same way that a navigation app automatically reroutes the driver around, say, an accident on the freeway, recovery in neuronal function following stroke requires “rerouting” connectivity around the brain lesion.

Existing therapies at the Lippoldsberg clinic work on just one or two brain functions at a time. The patients might be asked to assemble blocks in the “box-block” test (

Figure 10), identify missing numbers in a lineup of 1–9, or to perform cognitive and physical tasks simultaneously, such as calculating addition problems on a screen or matching images by moving the body to indicate one answer or another (

Figure 11). Lutyens became curious as to whether combining multiple stimuli and exercises at once might enhance brain plasticity and speed up stroke recovery.

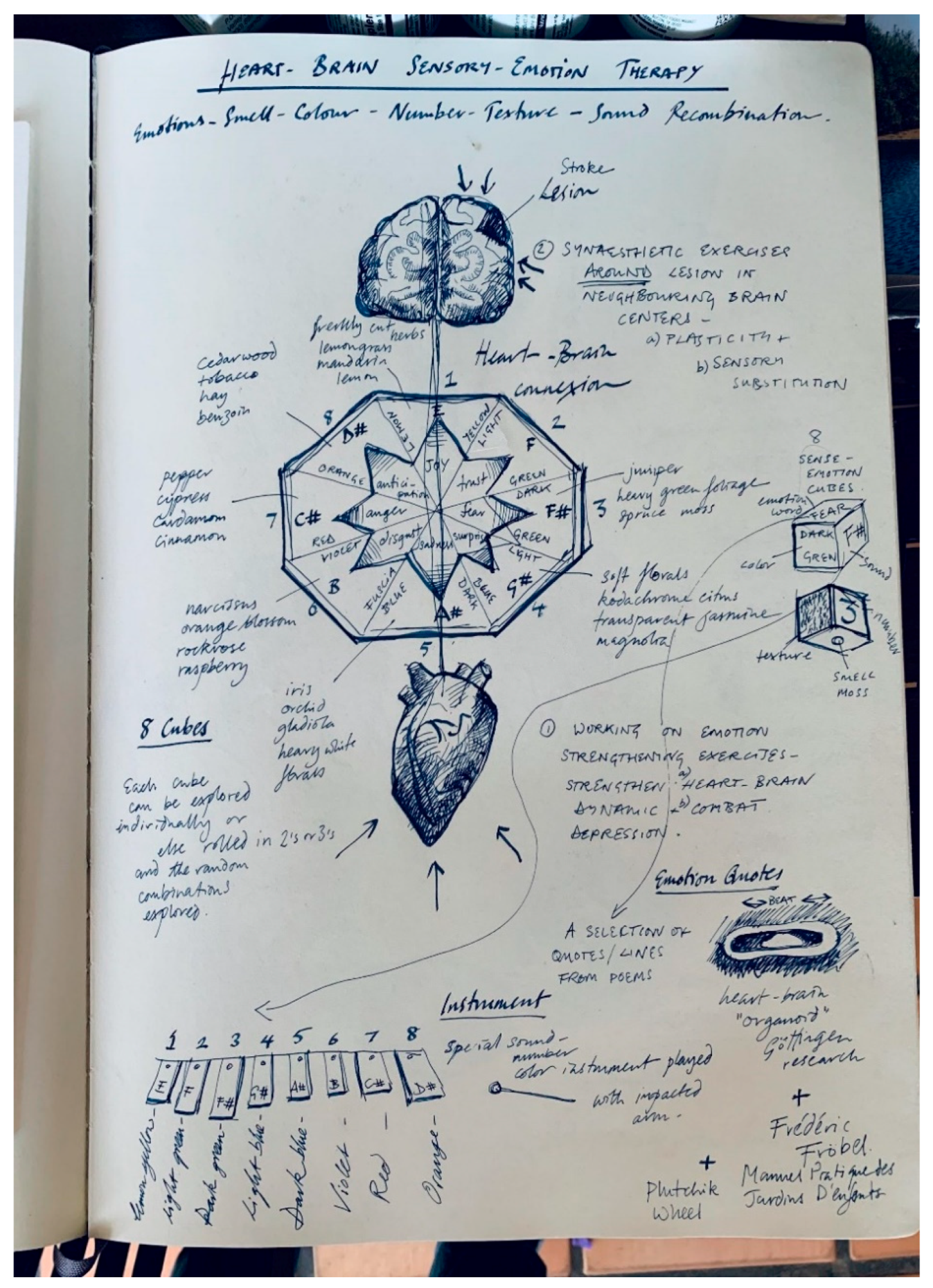

Lutyens envisioned the treatment as a kind of forced synesthesia (

Figure 12) (a condition affecting about 1 in 25 people in which different sensory modalities are involuntarily connected in the brain), which would be provoked in non-synesthetic patients by presenting different simultaneous stimulus modalities. A synesthete may see a color as sound or a letter as a taste or a sound as a texture. This is a similar state of consciousness to that which children under five years of age experience when the neural pathways of the brain have not yet been pruned back to create separated brain centers (

Lutyens 2014). Based on Lutyens’ conversations with the clinic’s psychologist as well as with Dr. Pinnau, it appears this approach could be beneficial to patients’ cognitive and physical recovery.

Lutyens is not the only artist who has been interested in synesthesia and clinical processes. Artist Daria Martin teamed up with scientist Michael Banissey, professor of psychology at Goldsmiths, in a program sponsored by the Wellcome Trust. In response to the collaboration, she created two 16-mm films:

Sensorium Tests (

Martin 2012) and

At the Threshold (

Martin 2014–2015), which explored the newly revealed condition of mirror touch synesthesia. A person with mirror touch senses when another person is touched as if they themselves are being touched, as though there are hyperactive mirror neurons being triggered in the brain that unconsciously echo what is being seen around the person and come to conscious attention as a hallucinatory sensation of touch. These films were a recreation of the discovery of the condition, as well as a fictional portrayal of a mother and daughter who both have the condition, but the films also reflected the clinical dynamic between a therapist or researcher and a patient, which is sometimes not as aligned as one would hope to create the best circumstances for wellbeing.

In the clinical context of stroke treatments, Lutyens envisioned a protocol that provokes synesthesia for therapeutic ends. This approach built on a previous work by Lutyens titled

Memory Observatory, in which colors, smells, images, sounds, and words were orchestrated to recreate old memories and stimulate new collective ones. The correspondences between different sensory modalities were achieved through an augmentation of the Plutchik Wheel (

Pico 2016), which maps a relationship between certain colors and certain emotions. Lutyens expanded these two correspondences to include smell and sound (

Figure 13). The correspondences between color, smell, and emotions were worked out with the expertise of perfumer Stephen V. Dowthwaite and are derived from the Fragrance Wheel, which was first developed by Austrian perfumer Paul Jellinek in 1949 (

Jellinek 1949;

Barwich 2017). The sound to color and emotions relationships were worked out with film sound designer Julia Owen. These were based on prevailing film sound design theory in which major keys are considered to be bright and associated with happiness, whereas minor keys are emotionally darker, as well as more rigorous psychological studies related to color, emotions, and sound by PerMagnus Lindborg and Andres K. Friberg (

Lindbrog and Friberg 2015).

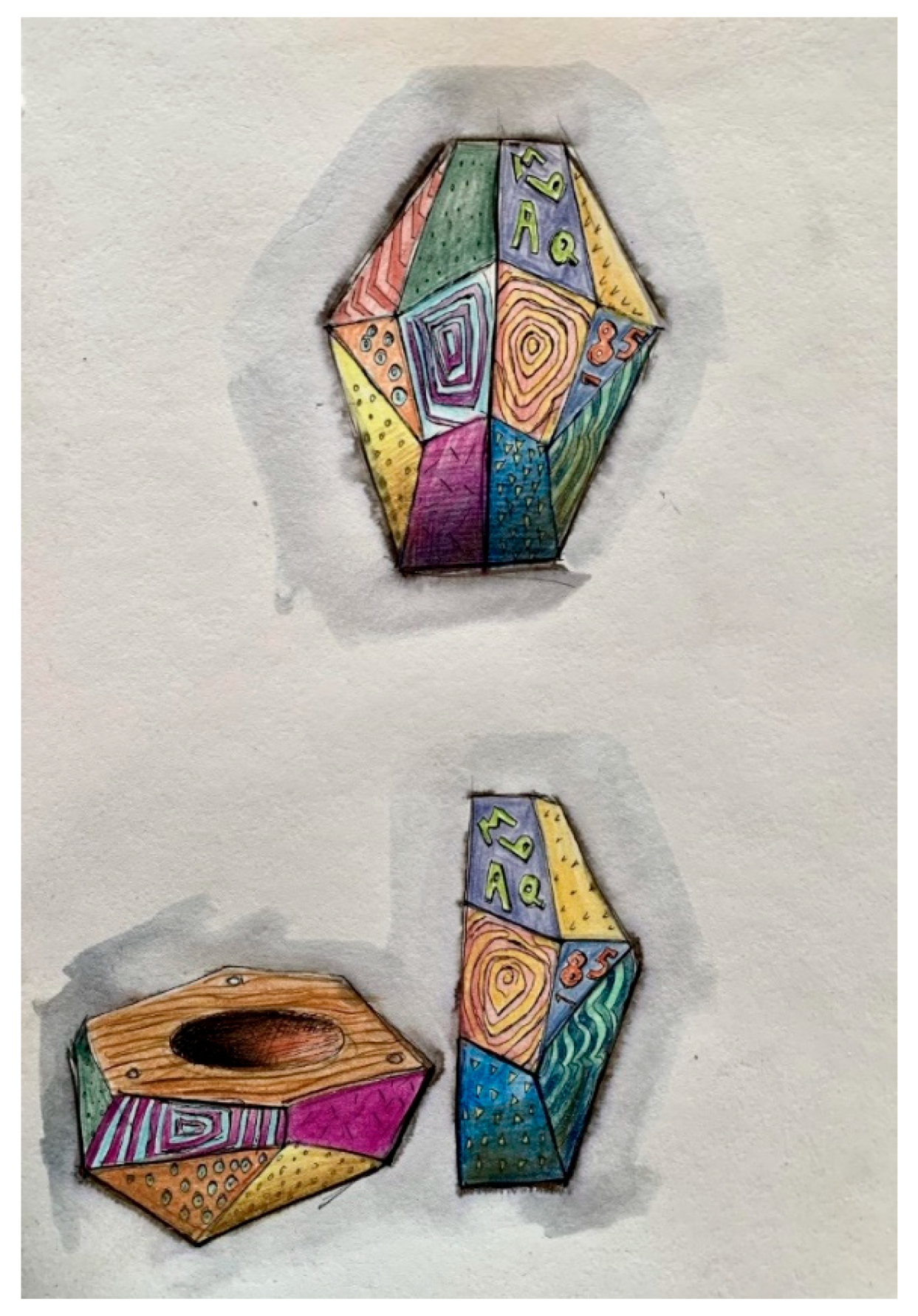

At Klinik und Rehabilitationszentrum Lippoldsberg, Lutyens is working on developing simple wooden blocks that have multiple facets. Each facet has a different content or quality, such as a texture, a color, a smell, a number, or a letter. These blocks are somewhat reminiscent of, and inspired by, Friedrich Fröbel, who initiated education for young children through a series of “gifts”, simple toys meant to instruct the learner in increasingly complex forms, materials, and physical relationships and that would lay the groundwork for modernist art and design pedagogy (

Provenzo 2009). He also promoted the idea that a classroom could become a nurturing garden-like space of learning, which we have come to know as kindergarten (

Brosterman 1997).

As the patient turns Lutyens’ faceted block in one or both hands, the mind consciously or unconsciously picks up on the different and contrasting qualities of each facet that stimulate different brain centers, particularly those around the primary somatosensory cortex, which is located in the lateral postcentral gyrus, a prominent structure in the parietal lobe of the human brain, as well as centers related to vision, smell, and cognitive functions for decoding numbers and letters. This process complements current research by Michael Kilgard, Ph.D., at the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas (

Kilgard et al. 2018), which seeks to increase neural plasticity through touch to improve brain function and healing. While scientific papers link tactile therapies to brain regeneration, there also appears to be a connection between the need to hold onto and turn an object and stimulation in the brain, which has been demonstrated through tests such as the aforementioned “box-block” test. Holding and turning an object in the hands has been a habit that finds new expression in every generation, from prayer beads to cigarettes to the current use of smartphones. Lutyens’ faceted block makes use of this predisposition to hold an object in one’s hands (

Figure 14).

Taking the idea of therapeutic multimodal stimulation one step further, the possibility is being explored of teaming up with the nearby Georg August University Medical Center of Göttingen to develop an experimental platform of brain stimulation optimized through machine learning. In preparing for this possibility, Lutyens reached out to Leonardo Christov-Moore, Ph.D., a neuroscience researcher at USC Brain and Creativity Institute. They decided to team up to frame the experiment, as well as to investigate precedents to verify that this forced-synesthetic approach would not only be artistically engaging but also produce positive therapeutic results.

5. The Current Project: Kernel of Consciousness

The meta-artwork

Kernel of Consciousness is a unique hyper stimulant of the mind, optimized via machine learning. A pattern of successive stimuli is fine tuned to generate neural regeneration in targeted brain areas (

Figure 15).

Much artificial intelligence (AI) research so far has been aimed at optimizing its own processes. Human intelligence has been devoted to creating machine learning or machine intelligence, with the presumption that at a certain point AI will take care of its own learning as it develops further (

Muehlhauser and Salamon 2012). A great deal of fear has been expressed, for instance, in Ray Kurzweil’s concept of the Singularity, which revolves around the vector of AI “taking over” and in so doing, prioritizing its own interests rather than humanity’s. However, what if AI could be used to enhance human intelligence (HI) so that both could expand, grow, and support each other?

Neuroscience research on functional recovery following injury and stroke has revealed two properties of the nervous system that can be leveraged to promote recovery: redundancy and malleability (

Wig 2017). First, the nervous system, particularly the brain, is massively, redundantly interconnected. For any damaged functionally relevant pathway between two networks/circuits, there are thousands of alternate pathways that can be recruited to restore function, thanks in large part to the nervous system’s malleability. Indeed, studies have shown sensory stimulation both activates brain areas inducing cortical reorganization and modulates motor cortical excitability for the stimulated afferents, neurons that carry nerve impulses from sensory stimuli to the central nervous system, hence re-establishing the sensorimotor loop disrupted due to stroke (

Bolognini et al. 2016).

These studies have primarily employed action observation, which “hijacks” mirror neurons to create vicarious patterned motor activation; motor imagery, which evokes top-down simulative processes for similar effect; and music therapy, which combines aspects of the prior two (stimulus-evoked mirroring, internal monitoring) with the powerful auditory and affective feedback provided by music.

This project seeks to use a feedback loop of brain monitoring and machine learning to optimize sequences of sensory and cognitive cues to the brain, with the aim of enhancing function in patients with stroke-related cognitive and motor deficits, as well as potentially improving function in healthy adults. The cues would be gathered from large, mostly existing or scraped datasets related to visual art broken down into colors, textures, words, numbers, body parts, etc. In the more haptic cases of body parts and textures, which would be inputted as images, the process of “feeling” these would rely on the so-called mirror neurons in the brain, akin to the synesthetic process of “mirror touch”. Sound and musical fragments would also be incorporated into the sensory deployment. Haptic and olfactory components could also be potentially incorporated. The aim is to activate simultaneously and dynamically as many brain networks as possible in order to stimulate the formation of novel, alternate neural pathways in order to recover and enhance brain function. The project is designed as much to enhance people with brain lesions such as stroke patients, as healthy adults. In either case, we would predict some degree of improvement in motor and cognitive abilities.

Although the project, which is still in progress, could be deployed on a smartphone, or in a VR or AR treatment clinic (in coordination with haptic stimulators), Kernel of Consciousness would also be displayed for the general public as a large array of screens or a projection dome within an art exhibition context.

The geography of how images are shown and hence seen by viewers (peripheral vs. frontal views) would be part of the sequencing honed through a learning algorithm, as the field of vision in itself affects different brain centers. The use of fragments from a vast array of visual art images turns the project into a kind of “meta-channeler” of a wide array of humanity’s cultures, culture being one of the primary vehicles that has enabled humans to develop beyond a level of subsistence into flourishing communities. This grows the stimulus dimensions from simply being multisensory to additionally evoking emotion, memory, and socio-cultural cognition, thus potentiating and multiplying the complexity and depth of subjects’ brain stimulation (

Figure 16 and

Figure 17).

Machine learning, with its potential for hypothesis-free optimization of multiple regression models (e.g., LASSO) (

Savaram 2019), can be employed here in three ways:

First, in the selection of stimuli prior to the study. By collecting explicit (self-reports) and implicit (fixation, heart rate) measures of engagement from a preliminary healthy, non-imaged cohort, we can create an optimized stimulus set.

Second, in the refinement of stimuli presentation within-subject. During the training/habituation phase of intervention, the same measures of engagement outlined above can be combined with informative brain measures (such as global connectivity) derived from, for example, a sparse-electrode electroencephalogram (EEG), which measures electrical activity in the brain, in order to optimize stimulus selection within-subject.

Third, machine learning could potentially be leveraged to improve our understanding of what variables mediate or predict improvement in daily function, prior to the study, by parsing existent databases/metanalyses to examine demographic and physiological characteristics that seem to mediate responsiveness to similar treatments. This will allow us to better assess the true effect of the intervention and control more effectively for confounding variables.

While multisensory stimulation has been employed successfully to mediate motor function following stroke in both rodents (

Quattromani et al. 2018) and humans (

Johansson 2012;

Law et al. 2018;

Tinga et al. 2016), our proposed intervention presents several points of improvement on extant therapies, based on our hypotheses that (a) greater immersion and engagement will result in greater neural recruitment and hence enhanced functional outcomes and (b) a greater breadth of sensory modalities and the incorporation of stimuli with affective, cultural, temporal qualities can serve not only to improve multi-network recruitment but perhaps even enhance function beyond the motor domain. This project aims to improve on past therapies by (a) providing olfactory stimulation in addition to immersive visual and auditory stimulation and (b) exposing subjects to stimuli with affective, cultural, and temporal qualities, thus increasing the range of neural recruitment to include high-level integration/association cortices as well as subcortical areas involved in motivation and affect. Furthermore, the aesthetic, presentational expertise and breadth/richness of stimuli afforded by the visual art/art theory acumen of Lutyens has the potential to produce a multisensory experience that is richer, more engaging, and hence more effective than the simple stock/public domain images and clips typically employed in neuroscientific research.

6. Proposed Methods

The participant sits in a specialized chair with haptic gloves/arrays on multiple body parts, an olfactometer, and a VR headpiece or concave screen, which would together display an array of visual imagery, sounds, haptic input (vibration, pressure, pulsing), and olfactory stimuli that slowly scroll through opposite and non-continuous themes, creating stimulus through juxtaposition. As an example, by juxtaposing the sight of a horse with the sound of someone clapping, with the color orange, with a sine wave tone, and with the smell of lavender, and a slow rhythmic force feedback to the feet, with a cascade of numbers, a landscape of shapes made of outlines, and an image of a hand feeling a rough texture the subject is exposed to a heightened sense of stimulation. Intuitively, if done in a calculated, rigorous way with the curation of machine learning, this kind of orchestration would help stimulate the brain and allow it to find new creative and functional pathways to both restore and enhance functioning.

Sparse (<32 channel) EEG can provide the kind of course measures of global brain connectivity and frequency band modulation that could be informatively used to gauge engagement and examine neural correlates of functional outcomes. Additionally, functional MRI, a device that measures brain activity relative to blood flow, could be leveraged (with more spatial precision than EEG) to provide measures of functional recovery as well as perhaps predict treatment response, once sufficient data were collected to allow for the training of supervised algorithms (knowing the pre-treatment brain activity and functional outcomes in a sufficiently large sample can allow for the prediction of treatment response in a novel sample).

7. Motor Function

Improvements in the patient, following multi-sensory therapy can be measured by Fugl-Meyer Assessment of Motor Recovery after Stroke (FMA), Manual Muscle Testing (MMT), Functional Test for the Hemiplegic Upper Extremity, and Modified Barthel Index (MBI) (

Gladstone et al. 2002) examine (a) low extremity function by assessing gait velocity, symmetry, and stride length and (b) upper extremity function by looking at functions such as reaching, final position accuracy, precision, and trajectory linearity.

Both within an artistic as well as a therapeutic context, the machine learning aspect, as it is applied to therapy, takes the journey of consciousness exploration, healing, and aesthetic experience to new places.

Finally, although the abovementioned approaches are primarily directed towards stroke patients, it is worth noting that neurotypical people also live in a relationship to our habitat that is molded by negative habits. Social and political unease, as well as the degrading ecologies of our planet, can be modified or turned into positive behaviors through therapies that engage empathetically with the senses and with nature. As the French philosopher

Catherine Malabou (

2017, p. 46) noted, “Addictive processes have for a great part caused the Anthropocene, and only new addictions will be able to partly counter them”. We hope that

Clinic Parcours will not just benefit stroke patients and their family members, but also the wider public to generate a healing process at many levels.

To conclude, in this paper, we have outlined the ability of art-related approaches to both creatively engage with the general public to explore various mental states and with patients in a clinical environment to extend traditional therapeutic approaches and outcomes. We suggest that by integrating artistic approaches within a medical context, this may be beneficial to patients, particularly in the framework of the treatment of stroke patients. The use of synesthesia-related approaches that engage several brain centers at once fits previous studies suggesting that multi-sensory stimulation is beneficial to stroke patients. The evolving sciences related to AI and machine learning also open up new frontiers of therapeutic engagement.