When work on the museum concept for the Old Synagogue in Erfurt was started in 2007, it was indisputable that the building’s history and function would be one main topic in the upcoming museum.

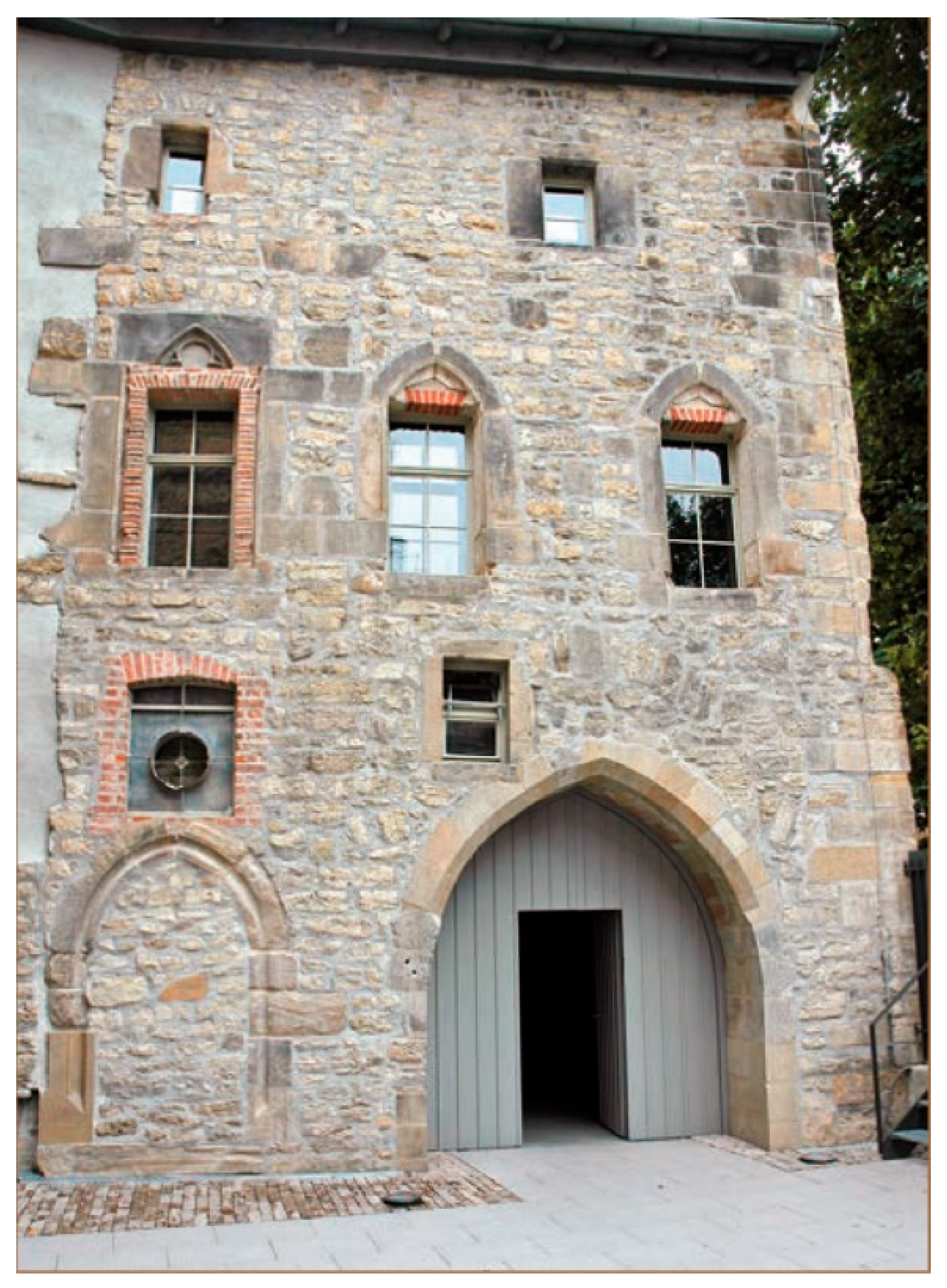

1 But this caused one of the biggest difficulties for the didactic work. Although the building itself is preserved in a very good condition (

Figure 1) (

Altwasser 2009)—unusual for medieval synagogues—almost everything of the interior is lost; especially those features which make a synagogue a synagogue. This did not just happen in the 19th and 20th century. Already, by converting the building into a warehouse after the devastating Pogrom of 21 March 1349, when all Erfurt Jews were murdered,

2 the building structure became a totally new one. For the warehouse, the main prayer room was split up into several storeys with two solid timber ceilings. Additionally, the new owner fitted in a vaulted cellar, which destroyed the Bima, the steps towards the Arc and all traces that could be found in the floor. The lighting cornice was spalled off and the original portal of the synagogue was walled up. Instead, two large gateways were inserted to enable a carriage to drive directly into the ground floor of the warehouse (

Figure 2) (ibid., pp. 84–94). One of these gateways presumably destroyed the Tora Ark: it is located in the middle of the eastern wall, the wall which points to Jerusalem. It is assumed that this gateway was placed here on purpose to erase the most important part of the former synagogue, the Torah Ark.

Against this background, the crucial question before creating the museum was how to explain a synagogue in a room like that, without any typical furnishing—without the Bima and the Torah Ark, the most important item in a synagogue room? At least, Elmar Altwasser, who examined the history of the building, could identify some artefacts from the synagogue interior: in the cellar, he discovered three stones, which probably originally belonged to the Bima, and enabled him to propose a reconstruction of it (ibid., pp. 56–59).

3 In the northern wall, he identified a stone with tracery ornaments in secondary use as a former part of the Torah Ark (

Figure 3) and delivered a reconstruction of the shrine as well (

Figure 4) (ibid., pp. 59–61, fig. 400). Although this reconstruction is not indisputable, to date there is no other, and we are still working with it. But how to communicate this reconstruction (or any other) in the museum?

We chose the original place of the Torah Ark in the former synagogue. To find a solution to deal with the disappearance, we compared other examples in former or still-working medieval synagogues in Central Europe.

Even if every example is different in place, preservation and condition, these can be divided into several categories:

Still intact and/or working synagogues with existing Torah Arks.

Synagogues which are functioning as museums, with or without Torah Arks.

Mostly intact synagogues, which are today in other use as residential buildings, concert halls, meeting places, etc.

Synagogues which are not intact but preserved in their basic structure (some including traces of the Ark).

Vanished synagogues which are remembered in modern synagogues, museums or similar institutions somewhere else, using fragments of Torah Arks

Only a few medieval synagogues are still serving as synagogues,

4 I will concentrate here on Prague and Worms. Today, the Old New Synagogue in Prague Josefov, completed in 1270 (

Paulus 2007, pp. 441–46), is not only an active synagogue, but also one basic element of many guided tours through the Jewish quarter of Prague. Its interior is mostly intact, with the metal Bimah in the center, surrounded by wooden seats. The Torah Ark, covered by the parochet, still contains Torah scrolls for the service (

Figure 5). The famous synagogue of Worms was destroyed by the Nazis in 1938 and rebuilt in 1961, using most of the original stone material (

Böcher 1960;

Paulus 2007, pp. 97–109). The baroque Torah Ark has also been reconstructed (

Figure 6). The building today functions as a museum, as well as a synagogue, for the Jewish community.

In Prague, as well as in Worms, the whole synagogue with its interior are in use—and can also be visited by tourists, individuals or with an organized guided tour. There are no further explanations (except by the tour guide); the Torah Ark just functions as a Torah Ark, containing the Torah scrolls for the service. Of course, this is the best solution of all!

The Old Synagogue in Sopron, built in the early 14th century, was used as a synagogue until 1526, when the Jews were expelled from the town. The former synagogue then became a residential building, which was renovated in 1967. Today it houses a museum. The Torah Ark is still intact, with the original tracery and colored painting (

Paulus 2007, pp. 414–17, esp. pp. 416–17 with fig. 159). Today, it is arranged with two “Torah scrolls” to explain the function—staging a synagogue interior in the museum (

Figure 7).

In Sopron, another medieval synagogue has been preserved, built in the middle of the 14th century, presumably as a private synagogue. Only the gable of the medieval Ark was left above a simple niche (

Figure 8) (ibid., pp. 417–19, fig. 164)—but, for creating a proper, nice, and “medieval” impression, the Torah Ark was “renovated” by adding a lancet blind arch (

Figure 9). The Torah Ark now functions as a sign for the former use as a synagogue—without being authentic anymore.

We can see the opposite approach in Maribor (ibid., pp. 401–4). Here, the Torah Ark was renovated too—but by aligning the surface and creating a regular form. Today, the former Torah Ark is just a white, clean niche in the eastern wall of the former synagogue (

Figure 10). The building today functions as a place for concerts, lectures and exhibitions—and the Torah Ark disappeared almost completely and has no function at all. The Maribor synagogue is an example, using synagogues as meeting places or function rooms—this is quite rare in medieval synagogues; later synagogues often are used like that.

The next step in disappearance we can see in the medieval synagogue in Rouffach. The late 13th century building is in use today as a private residential building. Only traces of the Torah Ark are visible—but not for regular visitors (ibid., pp. 487–92, esp. p. 491 with fig. 203). The medieval synagogue in Miltenberg today is part of a brewery (ibid., pp. 153–58;

Purin 1998). In the city’s museum, the gable of the Torah Ark is on display, which derives from this synagogue. It was in use presumably until the early 15th century, and then became property of a parish. In 1755, the newly established Jewish community bought the building and used it as a synagogue again, until the middle of the 19th century. In 1877, the community sold the building—and reused the Torah Ark in the newly built synagogue, which was inaugurated in 1904 and destroyed in 1938. Here, the medieval gable was combined with 19th century columns (

Paulus 2007, pp. 157–58, fig. 42)—similar to in the museum today (

Figure 11). The Torah Ark gable is part of the exhibition on Miltenberg city’s history and the history of Jews living in the city. Here, the Torah Ark (fragment) became an exhibit, taken out of its primary context. It is the only medieval Torah Ark which is on display in a museum.

The crest of a Torah Ark, originating from the late medieval synagogue of Nuremberg, was reused several times too. It seems that it was inserted in a residential building in the 16th century. Later, in the year 1909, it was incorporated in the 19th century synagogue at the Hans-Sachs-Platz—which was destroyed in 1938. The gable was retrieved and kept (again). In 1987, it was inserted into a wall in the newly built synagogue, where it remains today (

Paulus 2007, pp. 168–70, fig. 50). Here, it not only functions as a memorial for the expelled and murdered Jews of Nuremberg in medieval times, but also for the Shoah (

Figure 12).

Most of the preserved medieval synagogues today only exist in remains. One of the better conserved synagogues is the one in Speyer, sanctified in 1104, where the western and eastern walls are still standing (

Harck 2014, pp. 242–48;

Heberer 2004,

2012;

Paulus 2007, pp. 85–96). But, by converting the synagogue into an armory in the 16th century, the Torah Ark and the appendant apse were removed (

Heberer 2012, p. 46;

Paulus 2007, p. 96). The traces of bricking up the wall are hardly visible today. In the Museum SchPIRA, aside from the synagogue, there are spolia of the Torah Ark on display, together with a screenshot from the three-dimensional reconstruction of the synagogue’s interior.

In Vienna, the medieval synagogue was excavated; in contrast to Speyer, only the lower parts of the walls are kept, as well as the basis of the Torah Ark and the Bima. Three main building phases could be detected between the early 13th and the late 14th century (

Helgert and Schmidt 2000, pp. 91–110;

Paulus 2007, pp. 379–83;

Harck 2014, pp. 265–72). Today the remains of the synagogue are shown at the Museum Judenplatz. In order to guarantee the supervision of the remains of the Bima in the underground showroom with the excavation, this was lowered in 1998 by approx. 1.6 meters. The place of the Torah Ark is marked. A wooden model of the medieval synagogue only shows the outside of the building. In the course of a new conception of the permanent exhibition in the Museum Judenplatz, which will be presented from November 2020, an AR/VR reconstruction of the interior of the synagogue is currently being worked on. By means of a progressive web app, visitors will be able to call up more detailed information on individual elements of the excavation, including the Torah Shrine.

5The medieval synagogue of Regensburg was destroyed in 1519 and excavated in the late 1990s. In contrast to older assumptions, the 16th century Neupfarrkirche wasn’t built at the exact place of the synagogue—the synagogue’s remains could be excavated west of the church (

Codreanu-Windauer and Ebeling 1998;

Paulus 2007, pp. 174–81).

6 The basis of the Torah Ark was also discovered. Today, a sculpture, created by Dani Karavan, commemorates the medieval synagogue by imitating the synagogue structure. The place of the Torah Ark is marked by the inscription מזרח, i.e., east (

Figure 13).

The most recent example is the emerging Jewish Museum in Cologne. At the moment, the collaborators are working on the concept—thankfully, they provided me with an insight into their plans.

7 Within the excavated foundation walls, the basement of the Bima was discovered, as well as the basis of the Torah Ark—as well as decorative and architectural fragments—already by Otto Doppelfeld in the 1950s. Both structures were damaged, in part after the excavation, when a public square was created above it (

Paulus 2007, pp. 118–27;

Harck 2014, pp. 217–42). In excavations since 2007, all structures have been discovered again (

Kliemann and Wiehen 2016,

2019). The Torah Ark basis was found in 2014, and will be replaced in the upcoming museum. Due to the architectonical conditions and the fragility of the archaeological features, it will not be possible for future visitors to go inside the former synagogue and have a close look at the remains of the Ark. The museum’s underground walking level will be some meters below the synagogue level; here, finds that can be linked to the Ark will be on display and a reconstruction will also be shown. From the first floor of the Museum building, and a balcony on the ground level, one can take a look at the synagogue’s interior from above and get an overall view. There information panels will be placed to explain the archaeological features and the architectural parts of the synagogue, like the ark.

These various examples show that there are as many solutions to deal with the (former) Torah Ark, as synagogues from the middle ages have survived.

The best solution, of course, is to use the Torah Ark for its primary function—but there are very few medieval buildings left that still function as synagogues. Most of the kept, rediscovered or excavated synagogues today are museums—but most of them only have very few remains of the Torah Ark or have lost it at all. Medieval Torah Arks function today as an exhibit or memorial; some became just a clean niche in the wall or disappeared altogether.

It is the same situation in Erfurt, where the Torah Ark was destroyed as early as the middle of the 14th century. But it was clear that it was necessary to mark the original place in the museum, and we finally decided to do that by using the reconstruction drawing by Elmar Altwasser (

Figure 4) (

Altwasser 2009, p. 61, fig. 40). This was converted into a light projection (

Figure 14). The partly blurred lines illustrate the uncertainty of the reconstruction—the whole projection can be easily switched off or replaced by a renewed reconstruction. With this projection, the orientation to Jerusalem for the former prayer room is re-established—without a “real” reconstruction of the Ark.

Even though three-dimensional reconstructions in animated films risk creating an apparent reality, they are easy to understand and loved by the public. This is why we decided to create a three-dimensional reconstruction of the Torah Ark too—included in an animated film—but not to show it on a big screen or similar in the museum. It is integrated into the guided tour via an iPod-based video guide, or can be seen on the museum’s website.

8 While using the video guide iPod, the visitor not only learns about the form and function of Torah Arks in the middle ages—he will (hopefully) also understand why the Erfurt Ark is gone and how we tried to reconstruct it.

Conclusions

The Torah ark is one of the most important pieces of the interior in a synagogue. In the few medieval synagogues that have survived, or where at least parts of them have been preserved, the Torah shrines are often damaged or have disappeared completely. But, even if the Torah shrine is completely lost, as in the Erfurt synagogue, it should still be included in a museum presentation to demonstrate the function of the building as a synagogue. In Erfurt, a light projection was chosen for this purpose, which shows the form of the shrine, but also the fragility of the virtual reconstruction.