Psychological and Gender Differences in a Simulated Cheating Coercion Situation at School

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Participants

4.2. Procedure

4.3. Instruments

4.3.1. Test Used to evaluate Anxiety

4.3.2. Test Used to Evaluate Psychological Inflexibility

4.3.3. Instrument to Assess Participant’s Behavior in the Academic Cheating Coercion at School

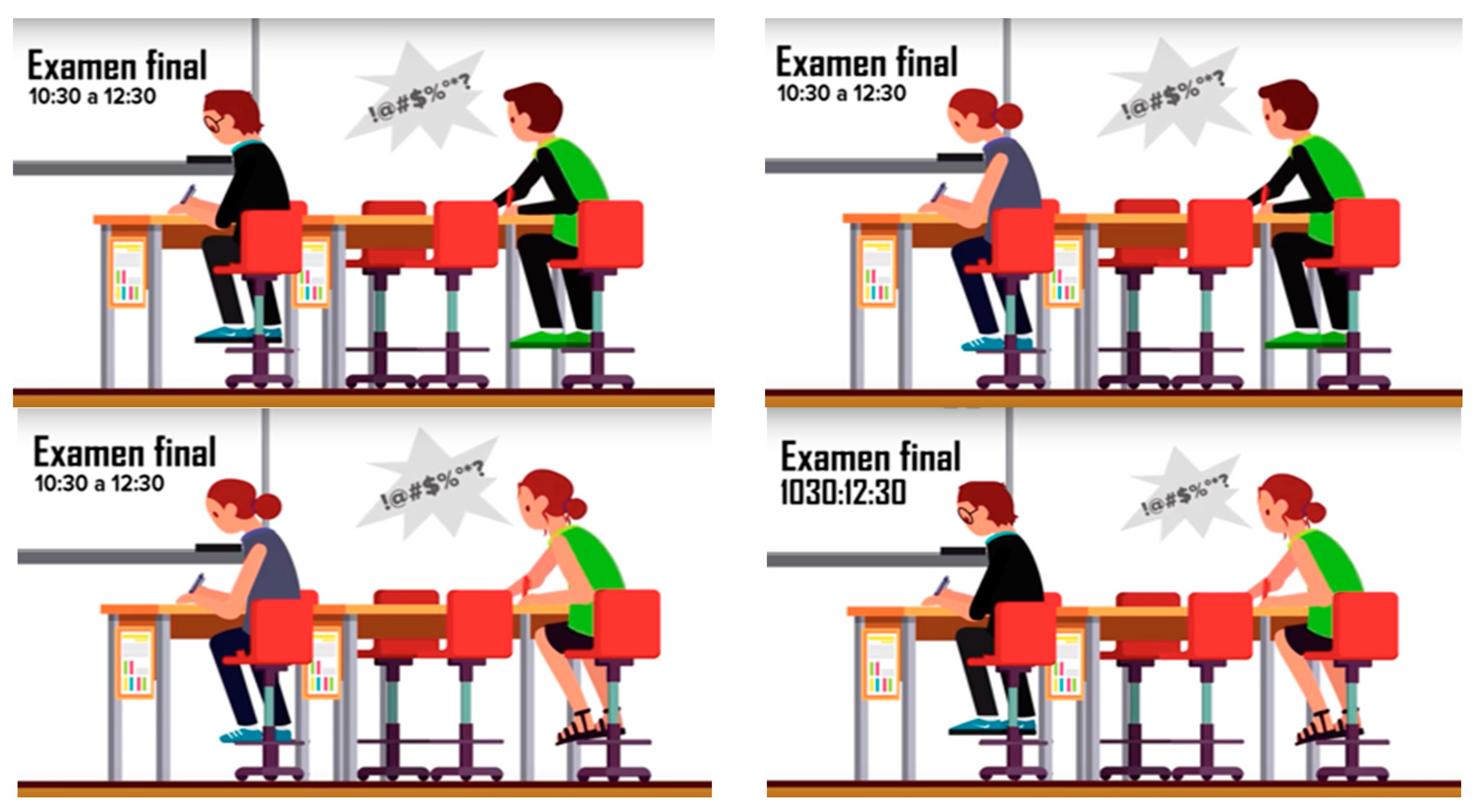

- Female (victim)—Female (offender): https://youtu.be/lBDIXJN88Sg

- Female (victim)—Male (offender): https://youtu.be/dlN6uQk-rvs

- Male (victim)—Female (offender): https://youtu.be/x9Nl00x3if0

- Male (victim)—Male (offender): https://youtu.be/jrDtAfRfbYU

- Some images taken from the videos could be seen in Figure 1.

- -

- I respond the same, with rudeness (aggressive).

- -

- I ask the teacher to change my position (avoidant).

- -

- I call the teacher to come over (supportive).

- -

- I give him/her the answer to avoid being attacked (submissive).

- -

- I tell him/her that his/her evaluation could be canceled (assertive).

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, RaeAnn E., Amanda M. Brouwer, Angela R. Wendorf, and Shawn P. Cahill. 2016. Women’s behavioral responses to the threat of a hypothetical date rape stimulus: A qualitative analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior 45: 793–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, Eleni. 2004. Bully/Victim Problems and Their Association with Machiavellianism and Self-Efficacy in Greek Primary School Children. British Journal of Educational Psychology 74: 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana, Allyson A., Erin Q. Boyd, Maria Guarneri-White, Priya Iyer-Eimerbrink, Angela Liegey Dougall, and Lauri Jensen-Campbell. 2018. The Impact of Social and Physical Peer Victimization on Systemic Inflammation in Adolescents. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly 64: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1999. Moral Disengagement in the Perpetration of Inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review 3: 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, Albert. 2002. Selective Moral Disengagement in the Exercise of Moral Agency. Journal of Moral Education 31: 101–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert, Claudio Barbaranelli, Gian Vittorio Caprara, and Concetta Pastorelli. 1996. Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 71: 364–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaranelli, Claudio, Maria L. Farnese, Carlo Tramontano, Roberta Fida, Valerio Ghezzi, Marinella Paciello, and Philip Long. 2018. Machiavellian Ways to Academic Cheating: A Mediational and Interactional Model. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beltrán-Velasco, Ana Isabel, Paula Sánchez-Conde, Domingo Jesús Ramos-Campo, and Vicente Javier Clemente-Suárez. 2021. Monitorization of autonomic stress response of nurse students in hospital clinical simulation. BioMed Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenson, Joyce F., Melissa N. Kuhn, Patrick J. Ryan, Anthony J. Ferranti, Rose Blondin, Michael Shea, Chalice Charpentier, Melissa Emery Thompson, and Richard W. Wrangham. 2014. Human Males Appear More Prepared Than Females to Resolve Conflicts with Same-Sex Peers. Human Nature 25: 251–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, Frederike, Macià Buades-Rotger, Marie Claes, and Ulrike M. Krämer. 2017. Hit or Run: Exploring Aggressive and Avoidant Reactions to Interpersonal Provocation Using a Novel Fight-or-Escape Paradigm (FOE). Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 11: 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bossuyt, Saar, and Patrick Van Kenhove. 2018. Assertiveness Bias in Gender Ethics Research: Why Women Deserve the Benefit of the Doubt: Marketing and Consumer Behavior. Journal of Business Ethics 150: 727–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante-Sánchez, Alvaro, José Francisco Tornero-Aguilera, Valentín E. Fernández-Elías, Alberto J. Hormeño-Holgado, Athanasios A. Dalamitros, and Vicente Javier Clemente-Suárez. 2020. Effect of Stress on Autonomic and Cardiovascular Systems in Military Population: A Systematic Review. Cardiology Research and Practice. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, Noel A., Brian D. Stucky, Gita M. Sawalani, and Todd D. Little. 2008. Direct and Indirect Aggression During Childhood and Adolescence: A Meta-Analytic Review of Gender Differences, Intercorrelations, and Relations to Maladjustment. Child Development 79: 1185–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo-Rusinque, Aura Alicia, Marina B. Martínez-González, Adriana Angélica De La Peña-Leiva, Inírida Avedaño-Villa, and Tito José Crissien-Borrero. 2019. Factores Psicosociales Asociados al Conflicto Entre Menores En El Contexto Escolar. Educação & Sociedade 40: e0189140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castrillón-Moreno, Diego Alonso, and Pablo Emilio Borrero-Copete. 2005. Validación del inventario de Ansiedad Estado-Rasgo (STAIC) en niños escolarizados entre los 8 y 15 años. Acta Colombiana de Psicología 8: 79–90. Available online: https://bit.ly/2QIuQyd (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- Cuttini, Laura A. 2017. Early Adolescents’ Reported Responses to Victimization by Peers: Links to Type of Provocation and Internalizing Symptoms. Ph.D. thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada. Available online: https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/pv63g270z?locale=en (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Delgado-Moreno, Rosa, Jose Juan Robles-Pérez, Susana Aznar-Laín, and Vicente Javier Clemente-Suárez. 2019. Effect of experience and psychophysiological modification by combat stress in soldier’s memory. Journal of Medical Systems 43: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirks, Melanie A., Teresa A. Treat, and V. Robin Weersing. 2014. Youth’s Responses to Peer Provocation: Links to Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 36: 339–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, Melanie A., Laura A. Cuttini, Addison Mott, and David B. Henry. 2017. Associations Between Victimization and Adolescents’ Self-Reported Responses to Peer Provocation Are Moderated by Peer-Reported Aggressiveness. Journal of Research on Adolescence 27: 436–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farnese, Maria Luisa, Carlo Tramontano, Roberta Fida, and Marinella Paciello. 2011. Cheating Behaviors in Academic Context: Does Academic Moral Disengagement Matter? Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 29: 356–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farrell, Albert D., David B. Henry, Sally A. Mays, and Michael E. Schoeny. 2011. Parents as Moderators of the Impact of School Norms and Peer Influences on Aggression in Middle School Students: Parent Protective Factors for Aggression. Child Development 82: 146–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández Villanueva, Icíar. 2009. Justificación y Legitimación de La Violencia En La Infancia: Un Estudio Sobre La Legitimación Social de Las Agresiones En Los Conflictos Cotidianos Entre Menores. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Servicio de Publicaciones, Madrid, Spain. Available online: https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/8436/ (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Finegood, Eric D., Edith Chen, Jennifer Kish, Katherine Vause, Adam K.K. Leigh, Lauren Hoffer, and Gregory E. Miller. 2020. Community Violence and Cellular and Cytokine Indicators of Inflammation in Adolescents. Psychoneuroendocrinology 115: 104628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán Jiménez, Jaime Sebastián F. 2018. Exposición a La Violencia En Adolescentes: Desensibilización, Legitimación y Naturalización. Diversitas 14: 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Sarah. 2019. Coping with School-Based Peer-Victimisation: The Role of Peers. Ph.D. thesis, Nottingham University, Nottingham, UK. Available online: http://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/37966/ (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Goodman, Michael L., Andrea Hindman, Philip H. Keiser, Stanley Gitari, Katherine Ackerman Porter, and Ben G. Raimer. 2020. Neglect, Sexual Abuse, and Witnessing Intimate Partner Violence During Childhood Predicts Later Life Violent Attitudes Against Children Among Kenyan Women: Evidence of Intergenerational Risk Transmission From Cross-Sectional Data. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 35: 623–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griebeler, Marcelo de C. 2019. “But Everybody’s Doing It!”: A Model of Peer Effects on Student Cheating. Theory and Decision 86: 259–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimond, Fanny-Alexandra, Mara Brendgen, Stephanie Correia, Lyse Turgeon, and Frank Vitaro. 2018. The Moderating Role of Peer Norms in the Associations of Social Withdrawal and Aggression with Peer Victimization’. Developmental Psychology 54: 1519–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernandez Rodriguez, Juventino, Samantha J. Gregus, James T. Craig, Freddie A. Pastrana, and Timothy A. Cavell. 2020. Anxiety Sensitivity and Children’s Risk for Both Internalizing Problems and Peer Victimization Experiences. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 51: 174–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, Courtland S., Amos Zeichner, and Joshua D. Miller. 2019. Laboratory aggression and personality traits: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Violence 9: 675–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iyer-Eimerbrink, Priya A., and Lauri A. Jensen-Campbell. 2019. The Long-term Consequences of Peer Victimization on Physical and Psychological Health: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, Stephen, and Hannah Stockton. 2018. The Multidimensional Peer Victimization Scale: A Systematic Review. Aggression and Violent Behavior 42: 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, Herbert C. 2001. Reflections on the social and psychological processes of legitimization and delegitimization. In The Psychology of Legitimacy: Emerging Perspectives on Ideology, Justice, and Intergroup Relations. Edited by John. T. Jost and Brenda Major. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 54–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jeongsuk, Bora Lee, and Naomi B. Farber. 2019a. Where Do They Learn Violence? The Roles of Three Forms of Violent Socialization in Childhood. Children and Youth Services Review 107: 104494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jeongsuk, Youn Kyoung Kim, and Naomi B. Farber. 2019b. Multiple Forms of Early Violent Socialization and the Acceptance of Interpersonal Violence Among Chinese College Students. Violence and Victims 34: 474–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-González, Marina B., Claudia Robles-Haydar, José Amar-Amar, and Fernando Crespo-Romero. 2016. Crianza y Desconexión Moral En Infantes: Su Relación En Una Comunidad Vulnerable de Barranquilla. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud 14: 315–30. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-González, Marina B., Claudia Robles-Haydar, José Amar-Amar, Raimundo Abello, Daladier Jabba, and Jairo Pimentel. 2019. Role-Playing Game as a Computer-Based Test to Assess the Resolution of Conflicts in Childhood. Interciencia. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=33960068012 (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Martínez-González, Marina Begoña, Claudia A. Robles-Haydar, and Judys Alfaro-Álvarez. 2020. Concepto de desconexion moral y sus manifestaciones contemporaneas/Moral disengagement concept and its contemporary manifestations. Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, Marina B., Yamile Turizo-Palencia, Claudia Arenas-Rivera, Mónica Acuña-Rodríguez, Yeferson Gómez-López, and Vicente J. Clemente-Suárez. 2021. Gender, Anxiety, and Legitimation of Violence in Adolescents Facing Simulated Physical Aggression at School. Brain Sciences 11: 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, Carmen P., and Emily R. Anderson. 2009. Brave Men and Timid Women? A Review of the Gender Differences in Fear and Anxiety. Clinical Psychology Review 29: 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton Reyes, H. Luz, Vangie A. Foshee, May S. Chen, and Susan T. Ennett. 2019. Patterns of Adolescent Aggression and Victimization: Sex Differences and Correlates. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 28: 1130–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, Clare M., and Yulia Dementieva. 2017. The Contextual Specificity of Gender: Femininity and Masculinity in College Students’ Same- and Other-Gender Peer Contexts. Sex Roles 76: 604–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercader-Yus, Esther, M. Carmen Neipp-López, Pedro Gómez-Méndez, Fernando Vargas-Torcal, Melissa Gelves-Ospina, Laura Puerta-Morales, Alexandra León-Jacobus, Kattia Cantillo-Pacheco, and Malka Mancera-Sarmiento. 2018. Ansiedad, autoestima e imagen corporal en niñas con diagnóstico de pubertad precoz. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría 47: 229–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meter, Diana J., Ting-Lan Ma, and Samuel E. Ehrenreich. 2019. Telling, Comforting, and Retaliating: The Roles of Moral Disengagement and Perception of Harm in Defending College-Aged Victims of Peer Victimization. International Journal of Bullying Prevention 1: 124–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pokharel, Bijaya, Kathy Hegadoren, and Elizabeth Papathanassoglou. 2020. Factors Influencing Silencing of Women Who Experience Intimate Partner Violence: An Integrative Review. Aggression and Violent Behavior 52: 101422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramberg, Joacim, and Bitte Modin. 2019. School Effectiveness and Student Cheating: Do Students’ Grades and Moral Standards Matter for This Relationship? ’ Social Psychology of Education 22: 517–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rayburn, Nadine Recker, Lisa H. Jaycox, Daniel F. McCaffrey, Emilio C. Ulloa, Megan Zander-Cotugno, Grant N. Marshall, and Gene A. Shelley. 2007. Reactions to dating violence among Latino teenagers: An experiment utilizing the Articulated Thoughts in Simulated Situations paradigm. Journal of Adolescence 30: 893–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riekie, Helen, Jill M. Aldridge, and Ernest Afari. 2017. The Role of the School Climate in High School Students’ Mental Health and Identity Formation: A South Australian Study. British Educational Research Journal 43: 95–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Conde, Paula, Ana Isabel Beltrán-Velasco, and Vicente Javier Clemente-Suárez. 2019. Influence of psychological profile in autonomic response of nursing students in their first hospital clinical stays. Physiology & Behavior 207: 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, Eric A., Marla R. Brassard, and Carrie L. Masia-Warner. 2003. The Relationship of Peer Victimization to Social Anxiety and Loneliness in Adolescence. Child Study Journal 33: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tornero-Aguilera, José Francisco, and Vicente Javier Clemente-Suárez. 2018. Effect of experience, equipment and fire actions in psychophysiological response and memory of soldiers in actual underground operations. International Journal of Psychophysiology 128: 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornero-Aguilera, José Francisco, José Juan Robles-Pérez, and Vicente Javier Clemente-Suárez. 2020. Could Combat Stress Affect Journalists’ News Reporting? A Psychophysiological Response. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 45: 231–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia-Salas, Sonsoles, José Martín-Albo, Pablo Zaldivar, Andrés S. Lombas, and Teresa I. Jiménez. 2017. Spanish validation of the Avoidance and Fusion Questionnaire for Youth (AFQ-Y). Assessment 24: 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, Susanne, and Lars Schwabe. 2019. Stress, Aggression, and the Balance of Approach and Avoidance. Psychoneuroendocrinology 103: 137–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wowra, Scott A. 2007. Moral Identities, Social Anxiety, and Academic Dishonesty Among American College Students. Ethics & Behavior 17: 303–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Mark, Robin Banerjee, Willemijn Hoek, Carolien Rieffe, and Sheida Novin. 2010. Depression and Social Anxiety in Children: Differential Links with Coping Strategies. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 38: 405–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Huanhuan, Heyun Zhang, and Yan Xu. 2019. Effects of Perceived Descriptive Norms on Corrupt Intention: The Mediating Role of Moral Disengagement: Descriptive norms facilitate corruption. International Journal of Psychology 54: 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Behavior When Faced with Coercion to Commit Fraud | |||||||

| Gender | Aggressive | Social Support | Assertive | Avoidance | Passive | Total | |

| Men | Count | 59.00 | 106.0 | 153.0 | 147.0 | 14.00 | 479.0 |

| % within row | 12.3% | 22.1% | 31.9% | 30.7% | 2.9% | 100.0% | |

| % within column | 54.6% | 40.9% | 44.6% | 36.4% | 42.4% | 41.8% | |

| Women | Count | 49.00 | 153.0 | 190.0 | 257.0 | 19.00 | 668.0 |

| % within row | 7.3% | 22.9% | 28.4% | 38.5% | 2.8% | 100.0% | |

| % within column | 45.4% | 59.1% | 55.4% | 63.6% | 57.6% | 58.2% | |

| Total | Count | 108.00 | 259.0 | 343.0 | 404.0 | 33.00 | 1147.0 |

| % within row | 9.4% | 22.6% | 29.9% | 35.2% | 2.9% | 100.0% | |

| % within column | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Chi-Squared Tests | |||||||

| Value | df | p | |||||

| Χ2 | 13.37 | 4 | 0.010 | ||||

| N | 1147 | ||||||

| Behavior When Faced with Coercion to Commit Fraud | ||||||||

| Participant Gender | Aggressor Gender | Aggressive | Social Support | Assertive | Avoidance | Passive | Total | |

| Men | Men | Count | 34.00 | 67.00 | 84.00 | 87.00 | 6.00 | 278.0 |

| % within row | 12.2% | 24.1% | 30.2% | 31.3% | 2.2% | 100.0% | ||

| % within column | 57.6% | 63.2% | 54.9% | 59.2% | 42.9% | 58.0% | ||

| Women | Count | 25.00 | 39.00 | 69.00 | 60.00 | 8.00 | 201.0 | |

| % within row | 12.4% | 19.4% | 34.3% | 29.9% | 4.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % within column | 42.4% | 36.8% | 45.1% | 40.8% | 57.1% | 42.0% | ||

| Total | Count | 59.00 | 106.00 | 153.00 | 147.00 | 14.00 | 479.0 | |

| % within row | 12.3% | 22.1% | 31.9% | 30.7% | 2.9% | 100.0% | ||

| % within column | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| Women | Men | Count | 29.00 | 82.00 | 77.00 | 121.00 | 5.00 | 314.0 |

| % within row | 9.2% | 26.1% | 24.5% | 38.5% | 1.6% | 100.0% | ||

| % within column | 59.2% | 53.6% | 40.5% | 47.1% | 26.3% | 47.0% | ||

| Women | Count | 20.00 | 71.00 | 113.00 | 136.00 | 14.00 | 354.0 | |

| % within row | 5.6% | 20.1% | 31.9% | 38.4% | 4.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % within column | 40.8% | 46.4% | 59.5% | 52.9% | 73.7% | 53.0% | ||

| Total | Count | 49.00 | 153.00 | 190.00 | 257.00 | 19.00 | 668.0 | |

| % within row | 7.3% | 22.9% | 28.4% | 38.5% | 2.8% | 100.0% | ||

| % within column | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| Total | Men | Count | 63.00 | 149.00 | 161.00 | 208.00 | 11.00 | 592.0 |

| % within row | 10.6% | 25.2% | 27.2% | 35.1% | 1.9% | 100.0% | ||

| % within column | 58.3% | 57.5% | 46.9% | 51.5% | 33.3% | 51.6% | ||

| Women | Count | 45.00 | 110.00 | 182.00 | 196.00 | 22.00 | 555.0 | |

| % within row | 8.1% | 19.8% | 32.8% | 35.3% | 4.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % within column | 41.7% | 42.5% | 53.1% | 48.5% | 66.7% | 48.4% | ||

| Total | Count | 108.00 | 259.00 | 343.00 | 404.00 | 33.00 | 1147.0 | |

| % within row | 9.4% | 22.6% | 29.9% | 35.2% | 2.9% | 100.0% | ||

| % within column | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| Chi-Squared Tests | ||||||||

| Participant Gender | Value | df | p | |||||

| Men | Χ2 | 3.189 | 4 | 0.527 | ||||

| N | 479 | |||||||

| Women | Χ2 | 12.052 | 4 | 0.017 | ||||

| N | 668 | |||||||

| Scale | Behavior | Mean | SD | N | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State Anxiety | Attack | 28.20 | 2.941 | 137 | 5.342 | 0.021 |

| No attack | 28.77 | 2.675 | 1010 | |||

| Trait Anxiety | Attack | 26.29 | 4.613 | 137 | 6.513 | 0.011 |

| No attack | 25.26 | 4.430 | 1010 | |||

| Psychological Inflexibility | Attack | 15.50 | 3.567 | 137 | 6.859 | 0.009 |

| No attack | 16.33 | 3.446 | 1010 |

| Moral Disengagement Mechanism and Expectative about Peers | Mean | SD | N | F | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait Anxiety | Moral justification | Neutral | 26.05 | 4.752 | 170 | 3.809 | 0.022 |

| Absence | 25.22 | 4.366 | 947 | ||||

| Presence | 26.67 | 5.346 | 30 | ||||

| Distorting the consequences | Neutral | 24.83 | 4.173 | 157 | 8.203 | <0.001 | |

| Absence | 25.12 | 4.176 | 687 | ||||

| Presence | 26.25 | 5.090 | 303 | ||||

| Victim blaming | Neutral | 25.00 | 4.082 | 283 | 6.333 | 0.002 | |

| Absence | 26.95 | 4.940 | 84 | ||||

| Presence | 25.35 | 4.511 | 780 | ||||

| Expectative about peers | Neutral | 25.40 | 4.355 | 575 | 8.386 | <0.001 | |

| Reject | 25.04 | 4.386 | 474 | ||||

| Legitimize | 26.67 | 4.937 | 95 | ||||

| Sanction | 35.00 | 5.292 | 3 | ||||

| Psychological Inflexibility | Advantageous comparison | Neutral | 16.29 | 3.514 | 823 | 3.243 | 0.039 |

| Absence | 16.64 | 2.830 | 128 | ||||

| Presence | 15.71 | 3.614 | 196 | ||||

| Expectative about peers | Neutral | 16.21 | 3.328 | 575 | 3.325 | 0.019 | |

| Reject | 16.35 | 3.621 | 474 | ||||

| Legitimize | 15.95 | 3.406 | 95 | ||||

| Sanction | 10.33 | 3.512 | 3 | ||||

| Variable | Dimension | Question | Response Options |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moral disengagement mechanisms | Moral justification | Do you think your reaction was? |

|

| Euphemistic labeling | What have you done? |

| |

| Advantageous comparison | If someone else was in your position |

| |

| Displacement of responsibility | Who started the problem? |

| |

| Diffusion of responsibility | If your friends find out about the incident and decide to confront him/her, who would be responsible for the situation? |

| |

| Distorting the consequences | Do you think you hurt your classmate? |

| |

| Victim blaming | Do you think your classmate deserved what you did? |

| |

| Dehumanization | The classmate who wanted to cheat is: |

| |

| Legitimation perceived | From peers | What would your classmates do when they found out about your reaction |

|

| From adults | Realizing the situation, what will the teacher do? |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-González, M.B.; Arenas-Rivera, C.P.; Cardozo-Rusinque, A.A.; Morales-Cuadro, A.R.; Acuña-Rodríguez, M.; Turizo-Palencia, Y.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Psychological and Gender Differences in a Simulated Cheating Coercion Situation at School. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10070265

Martínez-González MB, Arenas-Rivera CP, Cardozo-Rusinque AA, Morales-Cuadro AR, Acuña-Rodríguez M, Turizo-Palencia Y, Clemente-Suárez VJ. Psychological and Gender Differences in a Simulated Cheating Coercion Situation at School. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(7):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10070265

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-González, Marina Begoña, Claudia Patricia Arenas-Rivera, Aura Alicia Cardozo-Rusinque, Aldair Ricardo Morales-Cuadro, Mónica Acuña-Rodríguez, Yamile Turizo-Palencia, and Vicente Javier Clemente-Suárez. 2021. "Psychological and Gender Differences in a Simulated Cheating Coercion Situation at School" Social Sciences 10, no. 7: 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10070265

APA StyleMartínez-González, M. B., Arenas-Rivera, C. P., Cardozo-Rusinque, A. A., Morales-Cuadro, A. R., Acuña-Rodríguez, M., Turizo-Palencia, Y., & Clemente-Suárez, V. J. (2021). Psychological and Gender Differences in a Simulated Cheating Coercion Situation at School. Social Sciences, 10(7), 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10070265