Abstract

Background: Gender-based violence (GBV) remains largely under-reported and under-detected. The European project IMPROVE seeks to identify the needs of victims in terms of facilitating their access to support services and to assist frontline responder organisations in enhancing their competencies and capabilities to make the most of innovative solutions that enable and accelerate policy implementation. Methods: To meet these goals, IMPROVE uses narrative interviews, understood as unstructured tools that produce and analyse stories that are significant in people’s lives. These interviews provide the space for re-thinking; there is a reflection on implicit and taken-for-granted norms and insights are given into the life and thoughts of vulnerable groups, in this case, the women victim-survivors of GBV. Results: This methodological approach has led to high-quality interviews in which the women involved have felt comfortable, confident, and satisfied, as evidenced by the depth, complexity, and extension of the knowledge generated, and the commitment of the interviewees to the various activities proposed by the researchers. Conclusions: The narrative approach has allowed for a sensitive investigation into the private lives of GBV victim-survivors and, as a consequence, has contributed to the creation of new knowledge that can provide an in-depth and incisive view of the help offered by frontline responder organisations, from which improvements can be proposed.

1. Introduction

Research on gender-based violence (GBV) and domestic violence has increased significantly in recent decades. This can be attributed to the influence of gender equality policies, which have in turn translated into a heightened awareness of the issue, particularly in light of the gravity of the statistics surrounding this phenomenon. According to World Health Organization data, 736 million women (almost one in three) have suffered physical and/or sexual violence, either at the hands of their partner or sexual violence outside the relationship, or both, at least once in their lives (30% of the women over 15 years old). This implies that more than 640 million women (26% of those aged 15 and older) have fallen victim to partner violence (WHO 2021). In Spain, for instance, the number of women victims of gender-based violence increased by 8.3% in 2022, reaching 32,644 cases. In the same year, the rate of gender-based violence victims stood at 1.5 per 1000 women aged 14 and older and the number of domestic violence victims increased by 1.1% (INE 2023). The focus on this serious social problem began in the 1980s, thanks to the mobilisation of women’s groups, which were successful in framing violence against women as a matter of human rights (Alhabib et al. 2010). Various systematic reviews have attempted to analyse the findings of this growing number of studies. For instance, the review conducted by Samia Alhabib et al. in 2010 examined a total of 134 studies addressing the prevalence of violence, specifically domestic violence against women, conducted between 1995 and 2006. The studies in this review were published in English and included women aged 18 to 65 (Alhabib et al. 2010). Other analyses have systematically examined specific themes or approaches. An example is the study by Alison Gregory and colleagues in 2016, which focused on analysing studies addressing the repercussions on the adult friends, relatives, neighbours, and colleagues of women experiencing domestic violence (Gregory et al. 2017). Another study, conducted by Anastasia Kourti et al. in 2023, investigated the incidence of violence during the COVID-19 pandemic (Kourti et al. 2023).

Research on this issue shows the use of both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, although the objective of the analyses and the methodology differ depending on the research subject. The systematic reviews mentioned above report using both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. For example, Alhabib’s study highlighted that the most commonly used data collection methods included face-to-face interviews (55%), followed by self-administered questionnaires (30%) and telephone interviews (Alhabib et al. 2010, p. 372). In the review by Gregory et al., the majority of studies also used qualitative methods (13), followed by quantitative analysis (9) and, to a lesser extent, mixed methods (Gregory et al. 2017, p. 564). However, other authors such as Fátima Arranz Lozano argue that when the state enters into knowledge production, the methodology used becomes predominantly quantitative (Arranz Lozano 2015).

There is no doubt that the qualitative methodology is an appropriate approach with which to analyse issues that cannot be investigated through single direct or closed-ended questions (Birch and Miller 2000), and it is also clear that the objective is different depending on the choice to use one or the other methodology (Mira et al. 2004). Qualitative research attempts to describe the social reality through the experiences of individuals in their role as the actors and spokespersons of the social system in which they are inscribed (Murillo and Mena 2006, p. 10). It is, therefore, selective in its choice of participants, choosing subjects that “have something to say” about the social issue (Mira et al. 2004, p. 36).

Research on gender-based violence is not without risks, especially when it comes to qualitative methodology. This has meant that, for decades, more emphasis has been placed on the risks and challenges posed by this methodology when used on sensitive topics than on its benefits. In fact, authors such as Fiona Buchanan and Sara Wendt make a detailed analysis of what could be called the “bureaucracy of ethics” to refer to all the internal procedures that have to be managed in institutions when qualitative studies on issues such as gender-based violence are undertaken (Buchanan and Wendt 2018). According to several authors, this focus on risks is “potentially stifling research” relating to sensitive topics (Allen 2009, p. 399; Holland 2007). This has also resulted more often than not in an attempt to discredit qualitative knowledge (Buchanan and Wendt 2018, p. 763).

However, for a topic like gender-based violence, the use of qualitative studies represents added value, especially from the perspective of feminist epistemology, as it allows for the incorporation of the voices of those who have been excluded from the construction of knowledge and social reality (Buchanan and Wendt 2018; Silvestre Cabrera et al. 2020).

This article specifically analyses the potential of a method that allows the harnessing of the potential of qualitative methodologies while addressing some of the ethical issues and dangers for victim-survivors. To understand what this methodology consists of and how it can be applied to contexts such as gender-based violence and domestic violence, this paper builds on the work carried out in the European project IMPROVE (Improving Access to Services for Victims of Domestic Violence by Accelerating Change in Frontline Responder Organisations, Grant Agreement 101074010) by the research team from the University of Deusto.

From a methodological perspective, this study aims to look deeper into women’s experiences of gender-based violence by utilizing “narratives” as a methodological tool. This approach seeks to unveil, through the women’s own words, their experiences, responses, and survival strategies in the face of gender-based violence. In this study, the objective is to illustrate the effectiveness of employing the narrative tool with the women victim-survivors of gender-based violence.

To this end, our paper has been divided into five main sections. As an article aimed at contributing to the scientific debate on the potential of the narrative method in gender-based violence research, the methodological approach is prioritised over the results. Firstly, narrative inquiry is described in detail, and the previous uses in which this tool has already demonstrated its potential are outlined. Secondly, the materials and methods used to generate these narratives are described, as well as the sample used by the research team. Section 4 presents some of the main results obtained as a way to illustrate how narratives are being constructed and used in the project. Then, in Section 5, which refers to the Discussion Section, the potential and challenges that this tool still presents are highlighted based on the experience of the project. Section 6 collects the main conclusions of the study.

2. Using Narratives within the Context of IMPROVE1

As mentioned previously, the European project IMPROVE is a comprehensive initiative with the primary objective of developing tools aimed at increasing the reporting and detection of domestic violence. The project was designed based on the evidence that GBV victim-survivors are not fully aware of their rights and available services, choose not to report, and rarely seek assistance and support. This is supported by a wide variety of studies. For instance, Simmons and colleagues argue that “most women in abusive/controlling relationships simply do not utilize formal helping structures (e.g., shelters, domestic violence support groups, hot lines)” (Simmons et al. 2011, p. 1299). Similarly, it is acknowledged that, because of the difficulties in identifying and gaining access to them, less is known about the experiences and needs of multiply vulnerable, marginalised groups more broadly, for example, those in remote communities, those who live beyond the limits of the law, and stigmatised groups. On the other hand, many frontline responder organisations have challenges in detecting the diversity of victims and the multiple forms of violence and in organising effective between-agency cooperation, although improved training provisions, extensive guidelines, and advanced procedures have been made available. In particular, many vulnerable and marginalised victims, such as refugees, the elderly, minorities, or those with health problems or disabilities, tend to be under-detected and under-served and therefore do not have equal access to services and justice. The overarching goal of the project is to empower victims by fostering a profound understanding of their entitlements to essential services and justice.

Women victim-survivors of gender-based violence require participatory approaches that go beyond risk reduction and harm minimisation. These approaches must also address the powerlessness and lack of control often experienced in abusive intimate relationships. Therefore, it is essential to employ methods that empower women, enhance their autonomy, and foster a sense of being believed, ultimately promoting their personal control and freedom. In this regard, narrative interviewing is well-suited to fulfil these needs. Through narrative interviews, women have the opportunity to share their experiences in their own words, reclaim their agency, and shape their own narratives, thereby contributing to their empowerment and the sense of control over their own lives.

As the literature suggests, narrative interviewing, recognised as a fully complexity-informed method (Byrne and Callaghan 2014; McCall 2005), is well-equipped to shed light on the experiences of the women victims of gender-based violence. What is more, the representation of these women’s experiences as translated through personal stories or narratives is increasingly recognised as valuable and compelling in both evidential and practical terms (Fraser et al. 2004; Baldwin 2013). It can be said, thus, that through this approach, researchers have been able to see “in action” how different intersectional vulnerability profiles played out in the face of specific challenges, leading to a very diverse set of outcomes (Delaney et al. 2024).

The narrative inquiry developed in the context of IMPROVE has been central to exploring women’s life experiences (Susinos et al. 2008; Woodiwiss et al. 2017). This methodology gives value to people’s experiences, their self-interpretation of social facts, and the first-person story as a method of creating new knowledge (Clandinin 2007). Narayan and Kenneth’s (2012) studies are in line with Jean Clandinin’s (2007) argument. The authors conclude that giving the possibility and “inviting people to narrate their lives from their own experience and to ‘report’ this in their own voice allows for the exploration of how inequality grounds, intersect and are interconnected” (Narayan and Kenneth 2012, p. 514).

Jeong-Hee Kim (2016, p. 166) states that the main aim of the interview in narrative inquiry has to do with “letting the stories be told, particularly the stories of those who might have been marginalized or alienated from the mainstream, and those whose valuable insights and reflections would not otherwise come to light”. Along the same lines, Birch and Miller (2000) highlight that the narrative methodology serves as a pivotal device within qualitative research, enabling individuals to construct meaning from their experiences. The interview process in narrative inquiry is intentionally designed to allow the free expression of stories. This nuanced methodology presents a unique way to collect and understand diverse stories, essential for exploring complex and sensitive issues such as gender-based violence. Narrative inquiry not only facilitates the collection of personal stories but also offers a multifaceted perspective on the intricate interplay between narrative, knowledge acquisition, and methodological approach (Lyons 2007). In the field of narrative research, individuals engage in reflective processes to construct stories, making narrative thinking a method of inquiry wherein past events and actions are analysed to understand outcomes and envision future possibilities (Kim 2016). The narrative interview, a cornerstone of this approach, commences with an open-ended request for informants to share their experiences. Researchers actively listen, paraphrase for comprehension, and pose clarifying questions to delve into the richness of the narrative (Lindsay and Schwind 2016). This methodological shift challenges the traditional interviewer–informant dynamic by recognizing informants not as mere responders but as narrators with unique stories to tell in their own voices (Kim 2016; Chase 2005).

Distinct from structured interviews, the narrative interview encourages researchers to approach the process with an open mindset, acknowledging the informant’s experience as the focal point (Spradley 1979). In this dialogical exchange, the researcher seeks to understand the world from the informant’s perspective, aspiring to grasp the meaning of their experiences and emotions. By fostering an atmosphere of mutual learning, the researcher invites the informant to become a teacher, helping the researcher to understand the intricacies of the informant’s narrative (Spradley 1979). This approach not only mitigates the risks of identification and victimisation, crucial in sensitive topics like gender-based violence, but also contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the complexities inherent in individuals’ lived experiences.

These recommendations on how to develop a proper narrative inquiry are reflected in the methodology used in the European project “RESISTIRÉ” (Grant Agreement no. 101015990), which aimed to understand how COVID-19 policies impacted gendered inequalities in Europe and how societies in general—and vulnerable groups in particular—responded to these inequalities. In order to fulfil the project’s main aims, and involving a network of researchers in 30 countries, two of whom are the authors of this article, a twofold strategy was followed: first, a mapping of the different policies across Europe was made in order to analyse and verify the unequal effects of COVID-19 in vulnerable groups; next, following RESISTIRÉ’s interest in understanding the experience of individuals during the pandemic, intersectional narratives were collected in the EU27, Serbia, Turkey, Iceland, and the UK, generating a total of 793 narratives (Aglietti et al. 2023)2. Intersectionality is broadly defined as the interaction of the different axes of power (gender, race, class, etc.) that create the differentiated positions of relative privilege or oppression (Crenshaw 1989). In social science research, especially in the studies of inequality or equality policies, incorporating an intersectional perspective has become essential (López Belloso et al., forthcoming). While intersectionality is widely accepted in feminist theory, its methodological application has been less explored and presents significant challenges, as noted by McCall (2005, p. 1771). In Europe, intersectionality is often conceptualised as a framework for understanding the identity and experiences of oppression, aligning with what Crenshaw termed “political intersectionality”, which emphasises the relevance of inequalities and their interactions in the political strategies of social groups (Crenshaw 1991, p. 1252). This approach has been incorporated within the EU, focusing on the intersectional dynamics between civil society and institutions (Lombardo and Verloo 2009). However, “structural intersectionality”, which examines how the interaction of the axes of oppression shapes the different experiences of discrimination or violence, has received less attention due to the indeterminate nature of the term and the complexity of studying its structural or systemic aspects (Barrère and Morondo 2016).

3. Materials and Methods

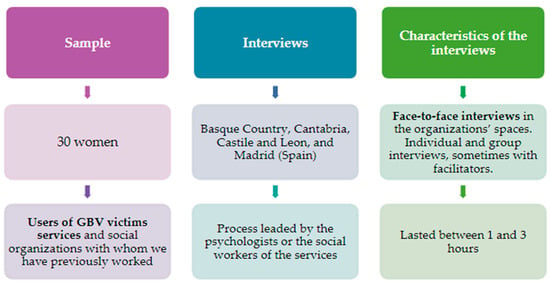

IMPROVE conducted an assessment of GBV victim-survivors’ needs, looking at their situation and the available institutional response through narrative interviews. Data were collected in 5 countries, including Austria, Finland, France, Germany, and Spain. This article focuses on research carried out in Spain. In this country, the study involved 30 women participants. The sample covered multiple types of victim-survivors, including vulnerable groups, such as two elderly and seven migrant/refugee women. The interviews were conducted in the Spanish regions of the Basque Country, Cantabria, Castile and Leon, and Madrid. This information is collected in Appendix A.

A multi-stage process was followed to produce the narratives as shown in Figure 1. Firstly, an exhaustive mapping of the associations and organisations working with the women victim-survivors of gender-based violence was carried out. Purposeful sampling was used to select the women participants in the study. Different types of organisations were selected, such as local services for gender-based violence victims, women’s organisations, services for people in social exclusion, and organisations that manage the international protection programme for refugees. Services and organisations with whom the researchers had previously worked or that were facilitated by third-party professionals were prioritised out of consideration for the vulnerability of gender-based victim-survivors. The participant selection and interview organisation process were led by the psychologists or the social workers of the services as a recognition of their knowledge of the cases and to build the participant’s confidence.

Figure 1.

Interview Process.

Secondly, topics to be explored during the narrative interview were proposed in order to respond to the needs assessment and the ultimate goal of the project: to improve victims’ access to support resources. The open approach to the topics serves to lead the narration, avoiding concrete formulations used in semi-structured interviews in which the interviewer exerts greater influence and control over the discourse. As stated by Muylaert et al. (2014, p. 186), when conducting narrative interviews, the role of the interviewer must be to transform questions resulting from the literature review and expert knowledge into questions brought by the informant.

In the third phase, in-depth interviews were conducted with the identified women following what the WHO (2001) considers to be essential safeguards when working with the women victims of domestic violence. These include ensuring women’s anonymity and safety throughout the research process; the use of advocates or intermediaries where necessary; ensuring a safe place for women to participate in the research process, and that their safety is a primary and ongoing concern throughout the research process and beyond; strict adherence to the safe storage of research data; and ensuring researchers have the necessary skills and expertise to work sensitively, safely, and collaboratively with such women. These issues are considered to be the main aspects of the research process. This research adheres carefully to the Gender, Ethical, Legal, and Societal aspects (GELSA) requested by the European Commission, including consent, participant safety, confidentiality, and data protection procedures. They have also been approved by the University of Deusto’s Ethical Committee.

To guarantee the safety and comfort of the participants, face-to-face interviews were prioritised over other methods as they favour closeness between the interviewer and participants from vulnerable groups such as the victim-survivors of GBV, in addition to allowing the collection of relevant information in the accompaniment before and after the interview (Romero Gutiérrez 2024). The interviews were held in the organisations’ spaces (counselling and group rooms), mostly one-to-one (interviewer–interviewee), but two were conducted in the company of the social worker of the shelter (one of them guided by two researchers, one of the two with a wide knowledge of the situation of the interviewee’s culture of origin). Four interviews were conducted in a group setting. The interviews conducted in the company of the social workers of the shelter were requested by the interviewees, and the social workers acted as a stimulus for them to tell their life stories. The interviews were audio-recorded except for one due to the fear shown by the interviewee in relation to her situation. The interviews lasted between one and three hours, including the opening and closing process. This extended time is relevant, helping each woman to feel as comfortable, confident, and satisfied as possible with her participation in the project and giving time for each to receive brief feedback and an acknowledgement of their experiences.

During the interviews, a non-hierarchical and interactive attitude between the researchers and interviewees was sought, following Ann Oakley’s epistemological contributions to interviewing women (Oakley 1981, 2016). This perspective is in line with the participants’ agency in the narrative practice: the interviewee as a source of knowledge, and the interviewer as an active collaborator in the co-production of the story, e.g., through the constant interaction and validation of the discourse (Gubrium and Holstein 2012). Women participating in IMPROVE confirmed and assured that they were feeling safe, comfortable, and valued when being interviewed. Generating true empathy with the women was a key element in creating this safety and comfort. In this context, empathy is understood as being present for an “other” individual in an intentional, unconditional way (Eriksson and Englander 2017).

The use of each woman’s language during the interviews is another key issue in this research. Muylaert et al. (2014, p. 185) emphasise the relevance of using the language of the informant in the introduction of the topics to be explored in the interview. With regard to feminist qualitative research, Sara Ahmed (2017) mentions the “negative” view of some of the words used by feminists and the possibility of avoiding them to facilitate the discourse. Thus, during the exploration of the women’s stories with the support services for the victims of gender-based violence, the terms used by each of the interviewees to refer to their history of abuse were understood as the main language, which does not always correspond to the approaches developed by feminism in relation to gender-based violence. Once the interviews had been carried out and transcribed, the narratives were prepared, as detailed below.

Constructing the Narratives

The information gathered in the interview phase was the basis on which the narratives were constructed. Each narrative was developed in relation to the reconstruction of the life history and access to support services for the victims of gender-based violence experienced by each woman participating in the study, following the objectives of IMPROVE. In this regard, the authors followed an intersectional perspective when identifying the different topics that build the narrative, which are as follows: (1) the personal background of the women participating and the type of violence they experienced as introductory elements to the character, (2) women’s access to services and their evaluation of the help they received, (3) the gender awareness-raising process, and (4) the intersectionality of the different systems of oppression that act on the victim-survivor, meaning that it is essential to examine and understand how social identities are formed and how the systems of oppression create inequities, recognizing that these elements do not exist in isolation from one another (Samuels-Dennis et al. 2011). Thus, through a lens of intersectionality, authors emphasise significant gendered and cultural influences. Gaining an understanding of the numerous individual and systemic factors affecting women offers valuable insights into how policies and services can more effectively support women escaping GBV (Williams et al. 2019). This methodological approach utilised in constructing narratives fits McCall’s “intracategorical approach”, which focuses on specific groups existing at the intersections of traditional categories, such as black women or lower-class individuals (McCall 2005, p. 1778). Rather than rejecting categories, this approach examines how individuals within these intersections experience and navigate power structures. It employs both qualitative and quantitative methods to analyse how specific intersections influence social experiences and outcomes. While this approach offers a deep understanding of how intersectionality is experienced in specific contexts, it may be limited in its ability to generalise findings beyond the studied groups (McCall 2005, pp. 1782–85). This approach is crucial for capturing the complexities of intersecting identities and how they interact with power structures in various social contexts.

The narrative reports were written in English by translating interview segments from the narrator’s native language. For confidentiality reasons, the narrators were referred to by pseudonyms in the reports according to the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants. A suggested word limit for the main narrative text was approximately 800 words. Keywords were also added for better use and organisation. The narrative reports were written by the researchers using the first-person perspective. Using this grammatical person has the benefit of making the reader see “the story from the perspective of the participant, which increases feelings of affinity” (Scheffelaar et al. 2021, p. 8). It also implies a sense of ownership that the stories belong to the narrators rather than the researchers (Byrne 2017). The women’s exact words were sometimes reproduced to give cohesion to the elaboration of the narrative. So that the findings of the research might be shared at conferences and congresses, the voice of these women was generated with artificial intelligence. This is intended to give realism to the story while protecting the personal data of the women participating in the study. Being able to personalise the experience during the process in a realistic embodiment helps the research team members to better understand the needs of the women in accessing services, and to empathise with their difficulties.

4. Results

In this section, some of the obtained results are presented, connecting the main objective of the project with the methodology used. Special emphasis has been placed on the methodological results, rather than on the findings of the interviews themselves, as the aim of this paper is specifically to analyse the potential of the tool.

The project is particularly interested in being able to analyse the barriers and challenges of the women victims of gender-based violence from an intersectional perspective by paying attention to the women faced with the different systems of oppression (Collins and Bilge 2020). Therefore, in both the sample selection process and the construction of the narratives, special attention has been paid to the construction of the stories that represent women in their diversity, disadvantaged by the multiple sources of oppression such as sexism, classism, ageism, racism, eurocentrism, language bias, and ableism. Thus, special attention was paid to selecting the women who could make a significant contribution to the research as opposed to more common or less diverse profiles (Mira et al. 2004).

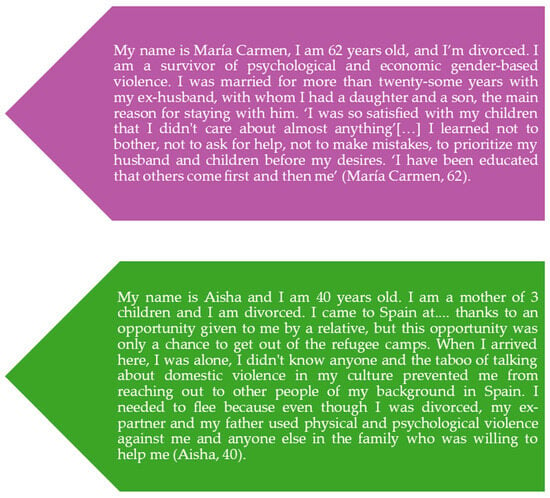

Thus, for example, the cases of María Carmen and Aisha represent the two groups of women traditionally rarely included in the study of gender-based violence: elderly women and migrant women. In addition, the approach to the life stories of these women was based on the narration of their experiences, avoiding the formulation of specific and closed questions. The most relevant information about their personal background and the type of violence they experienced was then synthesised in the presentation of each of them, as shown in Figure 2. This personal background already reveals some of the systems of oppression that affect these women. Traditional gender socialisation is present across the whole sample of women interviewed but is even more significant in elderly and migrant women. The elderly women interviewed in this research were born in Spain in the early 1960s, during the Francoist dictatorship, a historical period characterised by a traditional gender regime where the role of women was relegated to that of wife and mother. At that time, children were educated at single-sex schools, where the curriculum for girls was designed around submission and family and home duties (Susinos et al. 2008; Ballarín Domingo 2006). María Carmen’s life story shows this traditional gender socialisation in terms of relegating her to having less significance in her family, as reflected in her own words presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Women’s background in the narratives.

This way of presenting the women’s life stories allows, as we have already indicated, for a voice to be given to the experiences of the participants, with a faithful representation of their story, without compromising their data and safety. By not reproducing personal data and it not being possible to identify them secondarily through the narratives, this way of presenting the women’s reality helps the team to defend the protection of their personal data and the guarantee of their safety, thus combating the “ethics bureaucracy” (Buchanan and Wendt 2018). As already argued, this technique aims to highlight voices that may not otherwise have been heard.

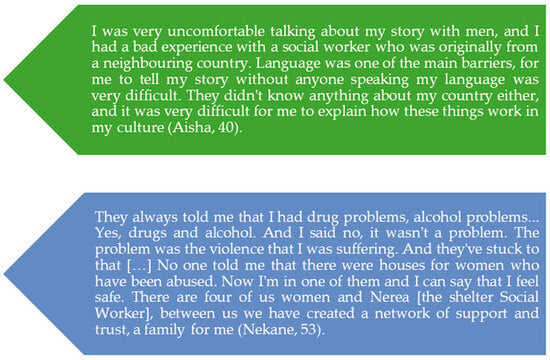

As Rosemary Hunter (2006) points out, although the feminist understanding of domestic violence as an issue of power and control is widely accepted, it has been expanded, modified, and, in some respects, rejected by non-hegemonic women who do not see themselves represented in the mainstream analyses of the issue. Thus, for example, she highlights among the experiences of women who do not conform to the standard “young white woman”, the impact of issues such as immigration regulations and immigration status (Hunter 2006, p. 745), which are clearly represented in Aisha’s story, as presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of the help received by non-hegemonic women.

Another issue highlighted by Hunter is the violence or discrimination that women with disabilities or addictions may experience in the process of violence or even in their relationship with support services (Hunter 2006, p. 745). Presenting the experiences of these women in an abstract way without contextualising their life history and their social, cultural, and family conditioning factors can make it difficult not only for these women to access support services, but also for the research staff and the support services themselves to connect with the special needs of these women. The experience of Nekane, shown in Figure 3, about the assessment of her needs as a victim of gender violence shows the biases that sometimes operate on the victims with addiction problems. The initial focus of support services on the addiction problem meant in her case the lack of action and provision of specific services available for the victims of gender-based violence. The origin of this harassment at the hands of institutional structures is the lack of credibility in the story of a non-hegemonic woman facing different systems of oppression.

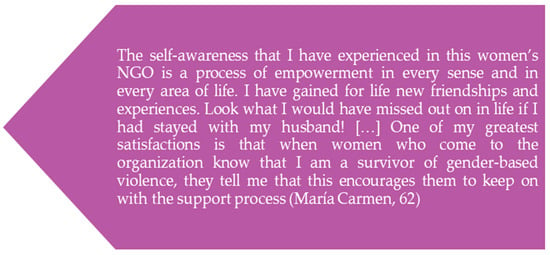

As underlined by Buchanan and Wendt (2018), in the field of feminist epistemology, the argument is made that women frequently provide valuable insights into personal enrichment during the interview process. Consequently, to delve into the distinct perspectives through which women perceived their participation as advantageous was an intended purpose. While the existing literature acknowledges that women find participation beneficial, the specific ways in which this benefit is experienced are often left unexplored in research publications. The women interviewed have shown a willingness to participate in the study as agents of the improvement of the aid they once received. Frequently, these women have evidenced a personal and social awareness that is beneficial both for themselves and for other women. In this sense, the different stories collected have allowed the project to gain knowledge about the ways of caring for the victims of gender-based violence that favour greater autonomy and gender awareness. The story of María Carmen, who was once a victim of GBV and now participates as a volunteer in the support service, shows the benefits and agency addressed, as presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Women’s agency and gender awareness-raising process.

All the narratives developed respond to the four above-mentioned discursive elements. The way in which the narratives capture these four elements facilitates a good understanding by the project team of the women’s needs and the ability to outline a plan that will result in improving the women’s access to resources. It is important to note that within the consortium, which brings together 16 partners from six different countries and different sectors, not all the partners have a feminist background, which sometimes makes it difficult for some of them to understand the realities of these women and connect with their needs. The personification of the findings from the in-depth interviews in narrative format helps these actors to empathise with them and better understand their needs, enabling them, therefore, to work on improving their access to services.

As evident from the examples provided, the narratives bravely embrace the subjectivity and tangible complexities of the women participants. Rather than shying away, the narratives purposefully accentuate these experiences, aiming to acknowledge and accept their subjectivity without undue fragmentation. This intentional approach is driven by the desire to preserve the richness, complexity, and dynamism of their stories, steering clear of any distortion (Mira et al. 2004).

This conscious commitment to making these women both the subjects and objects of the research is in line with the team’s feminist epistemological commitment to placing those who have been excluded from the construction of knowledge at the centre and valuing the contributions that the interviewees themselves make to the achievement of the project’s objective.

5. Discussion

The study of gender-based violence through a narrative approach has resulted in the conducting of high-quality interviews in the framework of the IMPROVE project. The perspective of Oakley’s non-hierarchical approach to interviewing women (Oakley 1981, 2016) has also contributed to the result. The women involved have expressed a sense of comfort, confidence, and satisfaction in participating in the project. This is evident in the depth, complexity, and extension of the knowledge produced relating to their access to and experiences with support services. But it was also shown in the enthusiastic engagement of the participants in the various activities proposed by the researchers after the interviews were conducted. This dissemination/return of findings to their participants is particularly relevant to feminist research (Gervais et al. 2018; Lafita Solé et al. 2023).

Narrative research has facilitated the exploration of the privacy of gender-based violence victim-survivors when asking for help. This methodology is particularly relevant in the case of those who might have been silent or marginalised and whose valuable insights and reflections might otherwise remain obscured (Kim 2016), as in the case of the victim-survivors of gender-based violence. First-person stories have evidenced women’s experience when seeking help from different support services, including law enforcement, community services, the social sector, or health services, and ways to improve access to support services. In contrast to structured interviews, narrative interviews have created the opportunity to focus on women as the narrators of their stories of life and abuse (Kim 2016; Chase 2005), showing their views and experiences with services, as well as other relevant issues not initially sought in the research design. This approach has paved the way to enquiring into the singular experience of women facing the different systems of oppression, such as the cultural origin and legal status of refugee women, the traditional gender socialisation of older women, or the intersection of multiple biases in the provision of services to victims. Narratives have also provided insight into which services address the recovery process in ways that lead to greater autonomy and gender awareness, a highly relevant issue for feminist research. As a result, women have contributed to creating new knowledge about support services (Buchanan and Wendt 2018), providing a profound and incisive perspective on the assistance offered by frontline responder organisations. These insights, in turn, pave the way for potential improvements to be proposed.

In addition, while providing victim and survivor stories, the narrative tool helps resolve privacy issues and risks associated with the research on sensitive topics (Allen 2009; Buchanan and Wendt 2018; Holland 2007), contributing to its legitimisation as a methodological approach. The construction of the narrative report on the women’s experiences with the support services by using pseudonyms, stories with some participants’ textual words, and reproducing voices with AI contributes to obtaining a first-person story in which the private life of the participants is exposed to a lesser extent. However, the difficulty of fully achieving the goal of eliminating the risks of participation is a challenge to continue working on.

From an epistemological perspective, narrative inquiry contributes to women’s agency in the construction of knowledge that favours the improvement of the help provided to those who suffer gender-based violence. This construction of knowledge is aligned with feminist epistemologies that seek to incorporate the perspectives of those who have been excluded from the construction of knowledge and social reality within official ideologies (Silvestre Cabrera et al. 2020). The interviews show that the main motivation for the participants to tell their stories within the framework of the IMPROVE project is the possibility of contributing to the improvement of the support they once requested and received. Although retelling their story may be therapeutic for many of the participants, as they manifest, their participation is political. The desire of the interviewees is for social and political change; they do not seek individual profit. The women participating in this research are, without a doubt, agents of feminist change.

6. Conclusions

This study puts forward the reason why narratives are considered to be a rigorous method when working with the women victim-survivors of gender-based violence. In this sense, this technique has proven to be an enriching method with which to analyse stories that are significant in women’s lives and that can also help to generate social change in a range of diverse contexts. Because of its emphasis on the significance of individualised discourses, the narrative research presents real opportunities for addressing inequality or powerlessness among vulnerable participants whose voices are less likely to be heard. Specifically, narratives can be a vehicle that allows for the experiences of those within society who live with the real-world impacts of intersecting inequalities to become accessible to those in positions of power.

Through amplifying the voices of those who are often sidelined with their situations reduced to individual failings, narratives can be integral to challenging the systems of oppression by making lived experiences understandable and no longer relegated to the margins.

Lastly, individualised narratives in social policy research have helped to inform and shape broader public and political discourses, as well as to influence and transform social policies and the lives of the participants themselves. The stories provided in this research reveal the agency of women in the construction of new knowledge for a better understanding of the phenomenon of gender-based violence and the progression of public policies in this regard.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I.C., L.R.G. and M.L.B.; methodology, L.R.G. and M.L.B.; formal analysis, L.R.G. and A.I.C.; investigation, L.R.G., A.I.C. and M.L.B.; resources, L.R.G.; data curation, L.R.G., A.I.C. and M.L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.R.G., A.I.C. and M.L.B.; writing—review and editing, L.R.G., A.I.C. and M.L.B.; visualization, L.R.G. and M.L.B.; supervision, A.I.C.; project administration, A.I.C. and L.R.G.; funding acquisition, A.I.C. and M.L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union, HORIZON Europe Innovation Actions, Grant Agreement number 101074010.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Gender, Ethical, Legal, and Societal aspects (GELSA) requested by the European Commission and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Deusto (Ref: ETK: 60/23-24).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors of the paper would like to express their gratitude to all the women who agreed to participate in this research process by sharing their personal experiences of gender-based violence. Also, to the professionals in the organizations who contributed to the participant identification and interview planification process. The authors would also like to thank professionals in the ASKABIDE association, for their help in contacting some of the women and also for conducting some of the interviews, especially to Sandra González Cabezas. They also appreciate the contributions received during the 8th World Conference on Qualitative Research, held at the University of Ponta Delgada (Portugal).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sample of women interviewed in Spain.

Table A1.

Sample of women interviewed in Spain.

| Pseudonym | Age | Autonomous Community | Women’s Specificity | Educational Background | Employment Status | Housing Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luciana | 40 | Basque Country | Migrant/refugee | Post-secondary education | Unemployed | Rented apt./house |

| Daniela | 36 | Basque Country | Migrant/refugee | Post-secondary education | In training/education | Rented apt./house |

| Isabella | 40 | Basque Country | Migrant/refugee | University degree | Unemployed | Supported housing |

| Aisha | 39 | Basque Country | Migrant/refugee, rural area | Secondary education | Employed part-time | Shelter |

| Nekane | 53 | Basque Country | Rural area | Post-secondary education | Unemployed | Shelter |

| Mónica | 48 | Cantabria | University degree | Retired | Own private apt./house | |

| María Carmen | 62 | Cantabria | Elderly | University degree | Employed full-time | Rented apt./house |

| Laura | 43 | Cantabria | Post-secondary education | Unemployed | Own private apt./house | |

| Cristina | 39 | Cantabria | Post-secondary education | Employed full-time | Rented apt./house | |

| María Ángeles | 63 | Cantabria | Elderly | Secondary education | Employed full-time | Apt./house of relatives |

| Sara | 43 | Cantabria | Secondary education | Employed full-time | Rented apt./house | |

| Marta | 46 | Cantabria | University degree | Employed full-time | Rented apt./house | |

| María Teresa | 55 | Cantabria | Post-secondary education | Unemployed | Rented apt./house | |

| Silvia | 49 | Cantabria | University degree | Employed full-time | Own private apt./house | |

| Patricia | 46 | Cantabria | Post-secondary education | Self-employed | Own private apt./house | |

| Raquel | 45 | Castile and Leon | Secondary education | Employed part-time | Own private apt./house | |

| Beatriz | 43 | Castile and Leon | University degree | Employed full-time | Own private apt./house | |

| Elena | 35 | Castile and Leon | Post-secondary education | Unemployed | Own private apt./house | |

| María Pilar | 51 | Castile and Leon | University degree | Unemployed | Own private apt./house | |

| María José | 50 | Castile and Leon | Secondary education | Unemployed | Own private apt./house | |

| Ana Belén | 49 | Castile and Leon | Primary education | Unemployed | Own private apt./house | |

| María Jesús | 54 | Castile and Leon | Post-secondary education | Employed full-time | Rented apt./house | |

| Ana María | 50 | Castile and Leon | University degree | Employed full-time | Own private apt./house | |

| Rosa María | 56 | Castile and Leon | University degree | Employed full-time | Rented apt./house | |

| Floria | 43 | Castile and Leon | Migrant/refugee | Post-secondary education | Employed part-time | Own private apt./house |

| Noelia | 45 | Castile and Leon | Post-secondary education | Employed full-time | Rented apt./house | |

| María | 53 | Castile and Leon | Post-secondary education | Employed full-time | Own private apt./house | |

| Camila | 21 | Madrid | Migrant/refugee | Post-secondary education | Unemployed | Shelter |

| Luciana | 35 | Madrid | Migrant/refugee | Post-secondary education | Unemployed | Shelter |

| Marcela | 44 | Madrid | Migrant/refugee | Post-secondary education | Employed full-time | Shelter |

Notes

| 1 | Complementary information regarding the IMPROVE project can be found at: https://www.improve-horizon.eu, accessed on 13 June 2024. |

| 2 | A selection of 80 narratives out of the almost 800 narrative interviews conducted have been published in the book named “(Better) stories from the pandemic”, one of the authors of this article being, one of the editors of the volume. |

References

- Aglietti, Claudia, Caitriona Delaney, Pinar Ensari, Elena Ghidoni, Audrey Harroche, Alexis Still, and Nazli Türker. 2023. (Better) Stories From the Pandemic. Örebro: Örebro University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Sara. 2017. Living a Feminist Life. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alhabib, Samia, Ula Nur, and Roger Jones. 2010. Domestic Violence Against Women: Systematic Review of Prevalence Studies. Journal of Family Violence 25: 369–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Louisa. 2009. ‘Caught in the act’: Ethics committee review and researching the sexual culture of schools. Qualitative Research 9: 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz Lozano, Fátima. 2015. Meta-análisis de las investigaciones sobre la violencia de género: El Estado produciendo conocimiento. Athenea Digital Revista de Pensamiento e Investigación Social 15: 171–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, Clive. 2013. Narrative Social Work. Theory and Application. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ballarín Domingo, Pilar. 2006. La educación propia del sexo. In Género y Currículo. Aportaciones del Género al Estudio y Práctica del Currículo. Edited by Carmen Rodríguez Martínez. Madrid: Akal, pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Barrère, María Ángeles, and Dolores Morondo. 2016. Introducing intersectionality into antidiscrimination law and equality policies in Spain. Competing frameworks and differentiated prospects. Sociologia del Diritto 2: 169–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, Maxine, and Tina Miller. 2000. Inviting intimacy: The interview as therapeutic opportunity. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 3: 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, Fiona, and Sarah Wendt. 2018. Opening doors: Women’s participation in feminist studies about domestic violence. Qualitative Social Work 17: 762–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, David, and Gillian Callaghan. 2014. Complexity Theory and the Social Sciences: The State of the Art. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Gillian. 2017. Narrative inquiry and the problem of representation: ‘giving voice’, making meaning. International Journal of Research & Method in Education 40: 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, Susan E. 2005. Narrative inquiry: Multiple Lenses, Approaches, Voices. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, pp. 651–80. [Google Scholar]

- Clandinin, D. Jean. 2007. Handbook of Narrative Inquiry: Mapping a Methodology. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Patricia H., and Sirma Bilge. 2020. Intersectionality, 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1989. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989: 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics and Violence Against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 43: 1241–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, Caitriona, Lina Sandström, Anne-Charlott Callerstig, Ainhoa Izaguirre Choperena, Usue Beloki Marañon, Marina Cacace, and Claudia Aglietti. 2024. The ‘why’ and the ‘how’ of using narratives in intersectional research—The experience of RESISTIRÉ. In Resisting the Pandemic. Better Stories and Innovation in Times of Crisis. Edited by Sofia Strid, Sara Clavero and María López Belloso. Berna: Peter Lang, under review. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, Karl, and Magnus Englander. 2017. Empathy in Social Work. Journal of Social Work Education 53: 607–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, Sandy, Vicky Lewis, Sharon Ding, Mary Kellett, and Chris Robinson, eds. 2004. Doing Research with Children and Young People. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Gervais, Myriam, Sandra Weber, and Caroline Caron. 2018. Guide to Participatory Feminist Research. Montreal: McGill University. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Alison Clare, Emma Williamson, and Gene Feder. 2017. The Impact on Informal Supporters of Domestic Violence Survivors: A Systematic Literature Review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 18: 562–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubrium, Jaber. F., and James A. Holstein. 2012. Narrative practice and the transformation of interview subjectivity. In The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, Kate. 2007. The Epistemological Bias of Ethics Review: Constraining Mental Health Research. Qualitative Inquiry 13: 895–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, Rosemary. 2006. Narratives of domestic violence. Sydney Law Review 28: 733–76. [Google Scholar]

- INE. 2023. Statistics on Domestic Violence and Gender Violence (SDVGV). Year 2022. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Estadística. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jeong-Hee. 2016. Understanding Narrative Inquiry: The Crafting and Analysis of Stories as Research. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Kourti, Anastasia, Androniki Stavridou, Eleni Panagouli, Theodora Psaltopoulou, Chara Spiliopoulou, Maria Tsolia, Theodoros N. Sergentanis, and Artemis Tsitsika. 2023. Domestic Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence & Abuse 24: 719–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafita Solé, Sabina, Gisela M. Bianchi Pernasilici, and Esther Escudero Espinal. 2023. Ikerketa feministak itzultzeko metodologia. In Investigación Feminista Sobre Migraciones. Edited by Instituto Hegoa y SIMReF. Bilbao: UPV/EHU, pp. 111–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, Gail M., and Jasna K. Schwind. 2016. Narrative Inquiry: Experience matters. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research 48: 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, Emanuela, and Mieke Verloo. 2009. Institutionalising intersectionality in the European Union? Policy developments and contestations. International Feminist Journal of Politics 11: 478–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Belloso, María, Elena Ghidoni, and Dolores Morondo. Forthcoming. Assessing the gender+ perspective in the COVID-19 recovery and resilience plans. In Resisting the Pandemic. Better Stories and Innovation in Times of Crisis. Edited by Sofia Strid, Sara Clavero and María López Belloso. Berna: Peter Lang, under review.

- Lyons, Nona. 2007. Narrative Inquiry: What Possible Future Influence on Policy or Practice? In Handbook of Narrative Inquiry: Mapping a Methodology. Edited by D. Jean Clandinin. Thousand Oaks: SAGE, pp. 600–31. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, Leslie. 2005. The Complexity of Intersectionality. Signs. Journal of Women in Culture and Society 30: 1771–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, José Joaquín, Virtudes Pérez-Jover, Susana Lorenzo, Jesús Aranaz, and Julián Vitaller. 2004. Qualitative Research Is a Valid Alternative Too. Atención Primaria 34: 161–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, Soledad, and Luis Mena. 2006. Detectives y Camaleones: El grupo de Discusión. Una Propuesta para la Investigación. Madrid: Talasa Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Muylaert, Camila Junqueira, Vicente Sarubbi, Jr., Paulo Rogério Gallo, Modesto Leite Rolim Neto, and Alberto Olavo Advincula Reis. 2014. Narrative interviews: An important resource in qualitative research. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP 48: 184–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, Kirin, and George M. Kenneth. 2012. Stories About Getting Stories: Interactional Dimensions in Folk and Personal Narrative Research. In The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft. Edited by Jaber F. Gubrium, James A. Holstein, Amir B. Marvasti and Karyn D. McKinney. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, Ann. 1981. Interviewing women: A contradiction in terms. In Doing Feminist Research. Edited by Helen Roberts. London: Routledge, pp. 30–61. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, Ann. 2016. Interviewing Women Again: Power, Time and the Gift. Sociology 50: 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Gutiérrez, Lorea. 2024. Feminist teaching in the current neoliberal university. Exploring and recognising women’s ways of working at the university. Journal of Gender Studies, Accepted by the editors of the Special Issue on Gender and Academic Employment in Changing Times. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels-Dennis, Joan, Annette Bailey, and Marilyn Ford-Gilboe. 2011. Intersectionality Model of Trauma and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. In Health Inequities in Canada: Intersectional Frameworks and Practices. Edited by Olena Hankivsky, Sarah de Leeuw, Jo-Anne Lee, Bilkis Vissandjée and Nazilla Khanlou. Vancouver: UBC Press, pp. 274–93. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffelaar, Aukelien, Meriam Janssen, and Katrien Luijkx. 2021. The Story as a Quality Instrument: Developing an Instrument for Quality Improvement Based on Narratives of Older Adults Receiving Long-Term Care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre Cabrera, María, María López Belloso, and Raquel Royo Prieto. 2020. The application of Feminist Standpoint Theory in social research. Investigaciones Feministas 11: 307–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, Catherine A., Melissa Farrar, Kitty Frazer, and Mary Jane Thompson. 2011. From the voices of women: Facilitating survivor access to IPV services. Violence against Women 17: 1226–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spradley, James P. 1979. The Ethnographic Interview. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Susinos, Teresa, Adelina Calvo, and Marta García. 2008. Retrieving feminine experience: Women’s education in twentieth-century Spain based on three school life histories. Women’s Studies International Forum 31: 424–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. 2001. Putting Women First: Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Research on Domestic Violence Against Women. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2021. Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Nicole, Katrina Milaney, Daniel Dutton, Stacy Lee Lockerbie, and Wilfreda E. Thurston. 2019. Systemic Factors Explain Differences in Low and High Frequency Shelter Use for Victims of Interpersonal Violence. Canadian Journal of Family and Youth 11: 180–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodiwiss, Jo, Kate Smith, and Kelly Lockwood. 2017. Feminist Narrative Research: Opportunities and Challenges. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).