Brújula Intersexual: Working Strategies, the Emergence of the Mexican Intersex Community, and Its Relationship with the Intersex Movement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Intersex Movement in Latin America

2. Study Design and Methods

- Periodic work meetings and discussions—we held meetings to discuss in pairs and as a team, and together, we chose the concepts to develop and proceeded to construct the structure of the article and write it. In addition, we carried out the revision of a specialised bibliography.

- Revision and analysis of the Brújula Intersexual archive—published and unpublished materials produced within a ten-year period were analysed. The timeframe covered the emergence of Brújula Intersexual from the 27th of October 2013 to the 8th of August 2023. We located materials produced that contain testimonies in the Brújula Intersexual archive—describing both everyday situations and intimate experiences—in order to reflect on how we came to them (Brújula Intersexual 2023a; Laura-Inter [pseud] and Alcántara 2024). This unveiled the basis of the functional mechanism of Brújula. With this in mind, we went back to reading, searching for resonances in the literature that would allow us to understand and explain that mechanism. In this research, ethical considerations regarding the use of cited testimonies were followed. The four intersex individuals who provided their testimonies for the Brújula Intersexual YouTube channel were informed that their testimonies would be used for this manuscript. They provided us with informed consent letters.

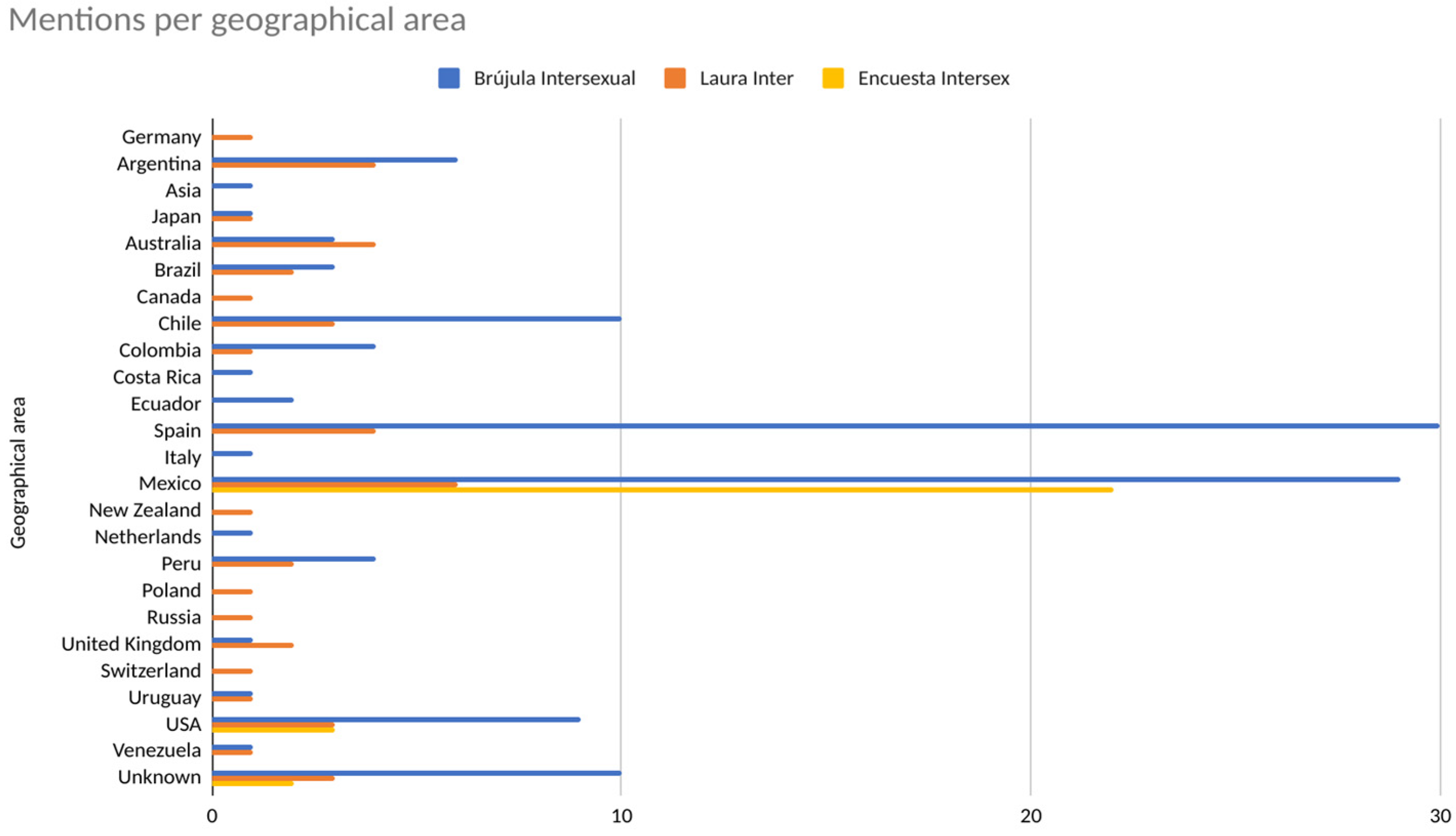

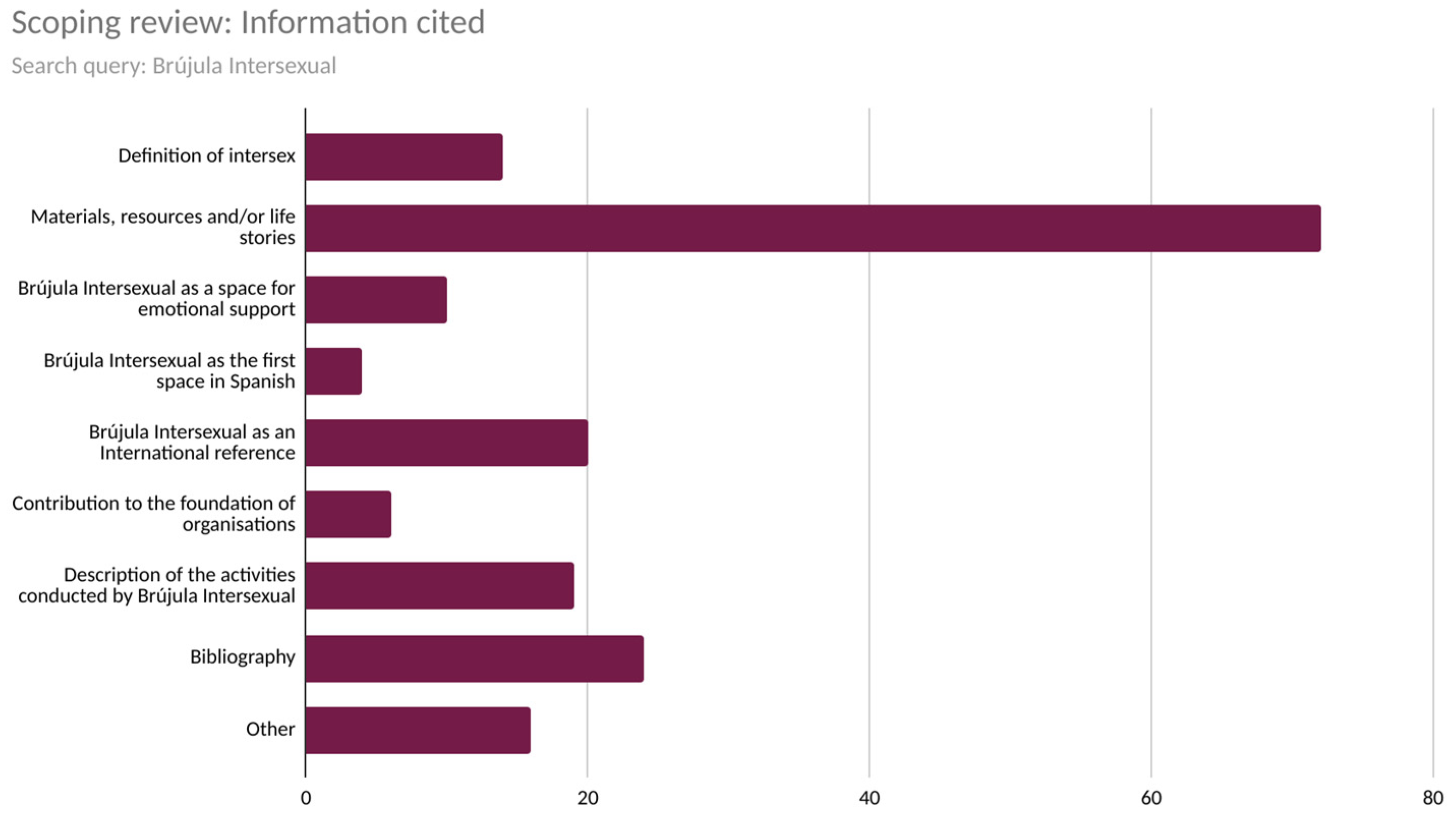

- A scoping review— we conducted a scoping review (Table S1) covering October 2013 to August 2023, using the keywords Brújula_Intersexual, Laura_Inter, and Encuesta_Intersex as search queries. We reviewed the sources and the form in which the keyword Brújula_Intersexual was referred to in digital spaces. The information obtained was organised by the research term in reverse chronological order in spreadsheets along with the following aspects: publication date, title, author, country, and type of document. The academic research was extended to two databases: Ebsco and Jstor. The name Laura_Inter was also sought on Academia.edu, yielding 3547 mentions in papers; however, as access was not paid, it was not possible to review the sources. The data collected were organised in tables and graphs.

- A timeline—to understand the chronology and events relevant to Brújula Intersexual located at three levels (national, regional, and global), we developed a timeline (Timeline S1). For this purpose, the timeline created by Hana Aoi/Sánchez Monroy (2018) was taken as an initial reference. Events referred to in research carried out by former and current core members of Brújula Intersexual were added to this timeline: Alcántara (2012), Toledo (2018, 2021), and Sánchez Monroy (2021). The Timeline of Intersex History found on Wikipedia was consulted. The timeline was completed through an intentional internet data search that included other relevant events on intersex activism in Mexico and Latin America linked to the work of Brújula Intersexual.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Brújula Intersexual: Structure and Working Strategies

3.1.1. An Organic, Spherical and Layered Device

3.1.2. Mechanism: Intimate Sphere and Atmosphere of Trust

Hi. My name is Mer. I have Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome, 46 XY.

I came across Brújula Intersexual looking for answers, looking to understand a bit more and to understand myself. Also, I found a lot of stories that represented me that I did not know about or could not find. And the most important thing I found were people—people who not only had the same thing that happened to me but who understood me when I talked to them. And in our case, finding someone who understands you, someone you can talk to, and, on the other side, realising that they understand what you are saying, that they understand what you feel or your feelings… that is immense.

So, the most important thing I found was people who understood me and wanted me not to be the only one but just another person, and I am grateful for that.

Particularly for me, as Camino Baró, an activist, you have helped me a lot… but also in my more private sphere, in my personal sphere, to gradually graduate the information that I could assimilate to reduce that feeling of loneliness that you have when you discover that you are a person with an intersex condition, and then you realise that there are many other variants, many other realities. After all, many people may be in the same situation as you.

“To disarm the configurations of power […] it neither begins nor ends in the individual […] such a practice feeds on resonances of other efforts going on the same direction and the collective force they promote, not only because of their power of pollination but also and fundamentally because of the synergies they produce. […] Such resonances and synergies produced create the conditions for the formation of a common collective body whose power of invention, acting under singular and variable conditions, can become strong enough to contain the power of forces prevailing in other constellations […] With these synergies, ways are opened to divert such power from its destructive destiny.”

My name is Pauli. I am a member of Potencia Intersex […] I came to Brújula in 2018 with quite an existential crisis, without knowing who I was, without knowing what place or group I belonged to, and I was able to find in this space not only a lot of containment and understanding, but also the possibility of being part of a movement that goes beyond Brújula, that goes beyond me. This movement is the global intersex movement, the intersex movement in the world, of which Brújula Intersexual is part, and it is a fundamental part, because it has been one of the first organisations that started to promote and generate information in Spanish, and also, in some way, to promote spaces for meeting, conversation, talk, dialogue about our corporealities.

Through Brújula, I could understand that I wasn’t a person with a disease, but a body different from other bodies and that I belonged to a group of people who respond to an international political movement that seeks to end genital mutilation in childhood, which is part of the experiences that intersex people go throughout our lives and that increasingly needs to be heard, to be listened to, to be seen… because, even today in all parts of the world or in many parts of the world, there are still children who undergo surgery to be mutilated and their bodies corrected and, so they can fit into the binary logics that move the world.

I had the feeling that it was a congenital malformation, as I was told to call it, and that I was a genetic accident, as if I were… I don’t know… an alien. However, through research I found other doctors who had a different sense of how to treat my medical condition or my diagnosis, which is Total Androgen Insensitivity. So that’s how I found Brújula.

[…] Thanks to them, I have recognised that I am part of a tribe, that I am not alone, that there are many of us but we have to start speaking out to make visible a condition that has been seen as a stigma, as something shameful that should not be talked about.

I think that genitalisation of our lives has been what has caused us the most harm, because we have been made to feel that there is a kind of handicap in our human condition compared to the rest of the people. However, thanks to Brújula I have found that this is not so, that I do not have to degrade the situation I live with and that I should feel proud. And the actions that I take will benefit me, the people in my tribe, and those who will come into existence in the future.

3.2. The Articulation of Brújula Intersexual within the Intersex Movement and Its Resonances in Public Policy

I realized I was not “deformed”, that there was nothing wrong with my body, that intersex is not a disease in itself, and that my genitals were quite healthy as they were and were not a problem. I understood that intersex is more common and more normal than we think. This helped me to find peace with my body. I also found people who had not had surgery and to my surprise they were healthy, and had satisfying sex lives, which reassured me. I have come to understand, through my own experience, that being intersex opens a whole new world of possibilities around sexuality. Our anatomies may oblige us to rethink sexuality, to challenge sexist or preconceived ideas about it, and this is a good thing. Now I am sure that nonconsenting surgeries, genital exams in infancy and early childhood, as well as the language doctors use, only serve to make things worse.

Spheres of Insurrection and Public Space

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In this article, we refer to Laura Inter in three different ways: (1) Laura Inter as an intersex person and activist, (2) Laura-Inter as an author, and (3) Laura_Inter as a search term. We found in different publications that Laura-Inter is cited as Inter, L.; however, this does not seem to be the most appropriate to us, as Laura-Inter is a pseudonym, and Inter is not her last name. |

References

- Adiós al Futuro. 2018. El Libro Intersexual. Habitaciones 3. México: Editorial 17. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre Arauz, Patricio. 2023. La Intersexualidad y Los Derechos Humanos En América Latina: Estado de Situación 2007–2021. Debate Feminista 65: 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcántara, Eva. 2012. Llamado Intersexual: Discurso, Prácticas y Sujetos en México. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Mexico City, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, Viola. 2016. Intersex Narratives. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Anne Emmanuelle. 2015. Los Fines de Un Idioma o La “Diferencia Sexual”. Revista Interdisciplinaria de Estudios de Género de El Colegio de México 1: 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borón, Atilio. 2020. América Latina en la Geopolítica del Imperialismo. Buenos Aires: Editorial XYZ. [Google Scholar]

- Brújula Intersexual. 2023a. Abriendo la Brújula. Video. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3XlkVJJVgbI (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Brújula Intersexual. 2023b. Camino Baró|Mensaje Por El X Aniversario de Brújula Intersexual. Video, min 00:17–00:57. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sjdLv3_fKLg (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Brújula Intersexual. 2023c. Mer Chalu|Mensaje Por El X Aniversario de Brújula Intersexual. Video, min 00:04–01:23. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_N6yb1Iekls (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Brújula Intersexual. 2023d. Orquídea|Mensaje Por El X Aniversario de Brújula Intersexual. Video, min 00:50–1:28 and 01:54–03:02. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eAmK05EnuVQ (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Brújula Intersexual. 2023e. Pauli|Mensaje Por El X Aniversario de Brújula Intersexual. Video, min 00:03–00:07 and 00:19–02:02. Available online: https://youtu.be/kEIJ-vU58Ww?feature=shared (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Cabral, Mauro. 2014. Derecho a la igualdad. Tercera posición en materia de género. Corte Suprema, Australia, NSW Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages v. Norrie, 2 de abril de 2014. Revista Derechos Humanos 3: 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, Mauro, and Morgan Carpenter. 2018. Gendering the Lens: Critical Reflections on Gender, Hospitality and Torture. In Gender Perspectives on Torture: Law and Practice. Washington, DC: Center for Human Rights & Humanitarian Law, Washington College of Law, American University, pp. 183–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, Mauro, ed. 2009. Interdicciones: Escrituras de la Intersexualidad en Castellano. Córdoba: Anarrés Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral Grinspan, Mauro, Ilana Eloit, David Paternotte, and Mierke Verloo. 2023. Exploring TERFness. DiGeSt Journal of Diversity and Gender Studies 10: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, Morgan. 2022. Global Intersex, an Afterword: Global Medicine, Connected Communities, and Universal Human Rights. In Interdisciplinary and Global Perspectives on Intersex. Edited by Megan Walker. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 263–80. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, Cheryl. 1998. Hermaphrodites with Attitude: Mapping the Emergence of Intersex Political Activism. A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 4: 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Georgiann. 2015. Contesting Intersex. The Dubious Diagnosis. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dreger, Alice Domurat. 2003. Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex, 4th ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fausto-Sterlling, Anne. 2006. Cuerpos Sexuados. Barcelona: Melusina. [Google Scholar]

- Feder, Ellen. 2014. Making Sense of Intersex. Changing Ethical Perspectives in Biomedicine. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de Rota, Antón. 2023. Paul Rabinow y La Antropología de Lo Contemporáneo. Disparidades. Revista de Antropología 78: e004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First Latin American Regional Conference of Intersex Persons. 2018. San José de Costa Rica Statement. Available online: https://brujulaintersexual.org/2018/04/13/san-jose-de-costa-rica-statement/ (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Foucault, Michel. 2001. Clase del 22 de enero de 1975. In Los anormales, 2nd ed. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, pp. 61–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gregori, Nuria. 2015. Encuentros y Desencuentros en torno a las Intersexualidades/DSD: Narrativas, Procesos y Emergencias. Ph.D. thesis, Universitat de Valencia, Valencia, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Guattari, Felix. 1992. Entrevista Félix Guattari Televisión Griega. Available online: https://youtu.be/7M928Npi6tg?feature=shared (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Guattari, Félix, and Suely Rolnik. 2006. Micropolítica. Cartografías Del Deseo. Madrid: Traficantes de sueños. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Morgan. 2009. Critical Intersex. Queer Interventions. Ireland: Routlege. [Google Scholar]

- Karkazis, Katrina. 2008. Fixing Sex. Intersex, Medical Authority, and Lived Experience. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, Suzanne J. 2002. Lessons from Intersexed, 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Laura-Inter [pseud]. 2015. Finding My Compass. Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics 5: 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laura-Inter [pseud], and Eva Alcántara, eds. 2024. Brújula. Voces de La Intersexualidad En México. Habitaciones 9. Mexico: Editorial 17. Available online: https://diecisiete.org/portadas/brujula-voces-de-la-intersexualidad-en-mexico (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Machado, Paula. 2008. O Sexo Dos Anjos. Representações e Práticas Em Torno Do Gerenciamento Sociomédico e Cotidiano Da Intersexualidade. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Marañón, Gregorio. 1951. Los Estados Intersexuales Del Hombre y La Mujer. México: Ediciones Arcos. [Google Scholar]

- Matus, Alfonso. 1972. Conductas terapéuticas en problemas de intersexo. Especialidad en. Pediatria thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer Foulkes, Benjamin. 2022. On Deconstruction as a Social Bond: Field Notes on 17, Institute of Critical Studies, 2001–2022. Webinar at Institute of Latin American Studies Columbia. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UDdB1w905Rs (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Mayer Foulkes, Benjamin. 2023. Ensamblaje crítico. Una Alianza social y Económica Productiva. Available online: https://diecisiete.org/actualidad/ensamble-critico-una-alianza-social-y-economica-pro-ductiva (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Melero, Iolanda. 2023. Ponencia Iolanda Melero Puche. In I Jornada sobre intersexualidad del Ministerio de Igualdad; Madrid: Ministerio de Igualdad, pp. 39–43. Available online: https://www.igualdad.gob.es/wp-content/uploads/JORNADAS_INTERSEX_accesible.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Monro, Surya, Morgan Carpenter, Daniela Crocetti, Georgiann Davis, Fae Garland, David Griffiths, Peter Hegarty, Mitchell Travis, Mauro Cabral, and Peter Aggleton. 2021. Intersex: Cultural and social perspectives. Culture, Health & Sexuality 23: 431–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morland, Iain. 2009. Introduction: Lessons From the Octopus. A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. Intersex and After 15: 191–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrini, Rodrigo. 2018. Deseografías. Una antropología del deseo. México: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. [Google Scholar]

- Parrini, Rodrigo, and Karine Tinat, eds. 2022. El Sexo y El Texto. Etnografías y Sexualidad En América Latina. México: El Colegio de México. [Google Scholar]

- Preciado, Paul B. 2022. Dysphoria Mundi. Barcelona: Anagrama. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinow, Paul. 2006. Steps Toward an Anthropological Laboratory. Laboratory for the Anthropology of the Contemporary. Available online: https://www.ram-wan.net/restrepo/teorias-antrop-contem/Rabinow_Laboratory.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Restrepo, Eduardo, and Rodrigo Parrini. 2021. Etnografía y Producción Conceptual: De La Descripción Densa a La Teorización Singular. Conversación Con Rodrigo Parrini. Tabula Rasa 38: 329–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnik, Suely. 2021. Esferas de la insurrección. Apuntes para descolonizar el inconsciente, 2nd ed. Buenos Aires: Tinta Limon. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, David A. 2017. Intersex Matters. Albany: State University New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Monroy, María Alejandra. 2018. Infografía Personas Intersex y Derechos Humanos. Dfensor, Revista de derechos Humanos 3: 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Monroy, María Alejandra. 2021. Romper el Silencio, Ocupar el Espacio: Cuerpo, Experiencia y Enunciación de Tres Activistas Intersex de México. Master’s thesis, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Mexico City, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Salud. 2017. Guía para la atención a la intersexualidad y variación de la diferenciación sexual, Protocolo Para el Acceso sin Discriminación a la Prestación de Servicios de Atención Médica de las Personas Lésbico, Gay, Bisexual, Transexual, Travesti, Transgénero e Intersexual y Guías de Atención Específicas, Mexico City, Mexico. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/558167/Versi_n_15_DE_JUNIO_2020_Protocolo_Comunidad_LGBTTI_DT_Versi_n_V_20.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Toledo, Mara. 2018. Aproximación Antropológica a la Experiencia Intersexual en Tres Contextos Culturales Diferentes en México. Bachelor’s thesis, Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico City, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo, Mara. 2021. Erótica Del Vínculo de La Experiencias Intersexuales En México: Indicios de Violencia y Derivas Del Deseo. Master’s thesis, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, Mexico City, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, Amiel, Anacely Guimarães Costa, Bárbara Gomes Pires, and Marina Cortez. 2021. A Excepcionalidade Da América Latina. Revista Periódicus 1: 220–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittig, Monique. 1980. The Straight Mind. Feminist Issues 1: 103–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alcántara, E.; Inter, L.; Flores, F.; Narváez-Pichardo, C. Brújula Intersexual: Working Strategies, the Emergence of the Mexican Intersex Community, and Its Relationship with the Intersex Movement. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13080414

Alcántara E, Inter L, Flores F, Narváez-Pichardo C. Brújula Intersexual: Working Strategies, the Emergence of the Mexican Intersex Community, and Its Relationship with the Intersex Movement. Social Sciences. 2024; 13(8):414. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13080414

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlcántara, Eva, Laura Inter, Frida Flores, and Carlos Narváez-Pichardo. 2024. "Brújula Intersexual: Working Strategies, the Emergence of the Mexican Intersex Community, and Its Relationship with the Intersex Movement" Social Sciences 13, no. 8: 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13080414