The History of the ABC Proteins in Human Trypanosomiasis Pathogens

Abstract

:1. Introduction

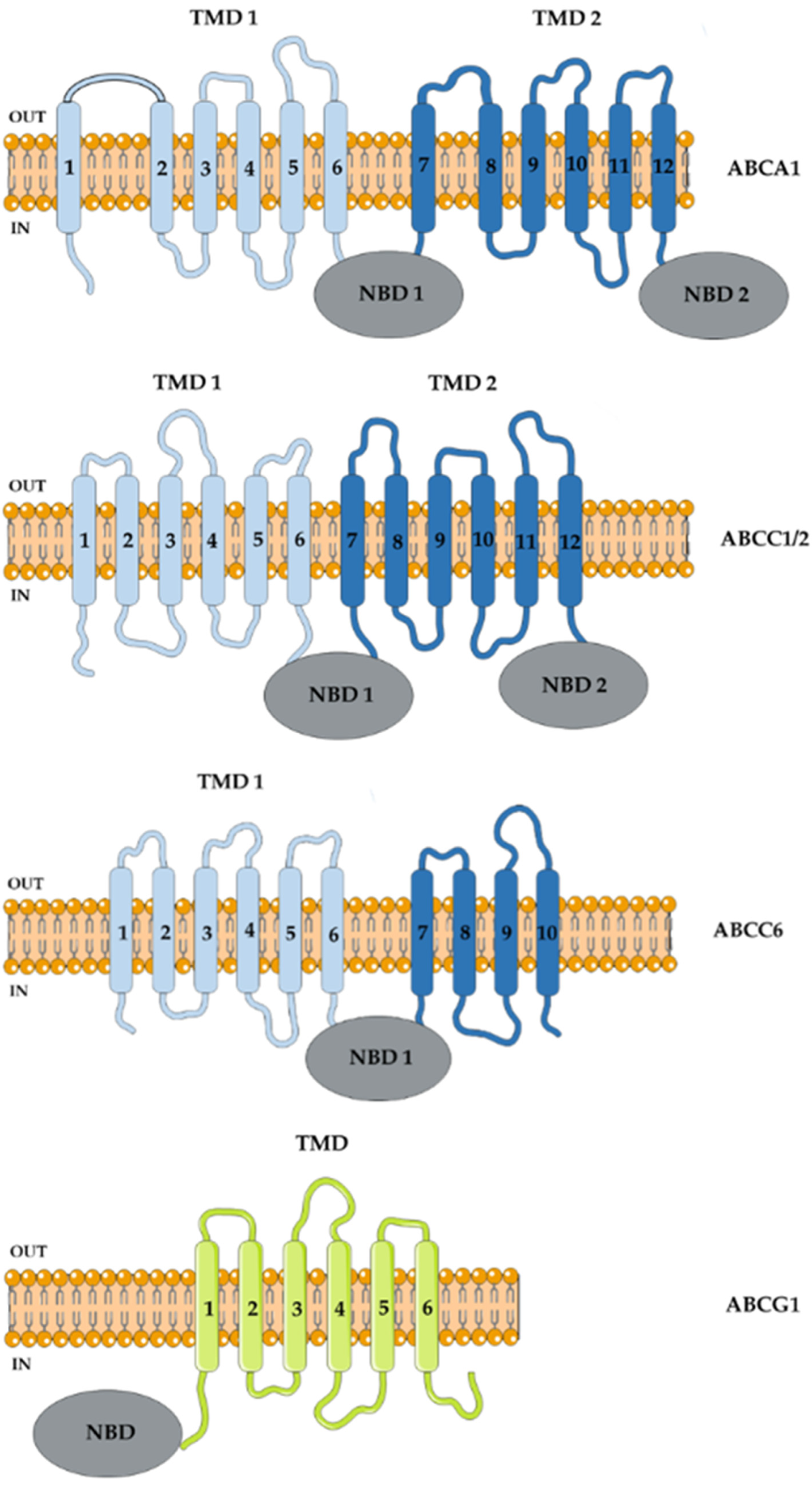

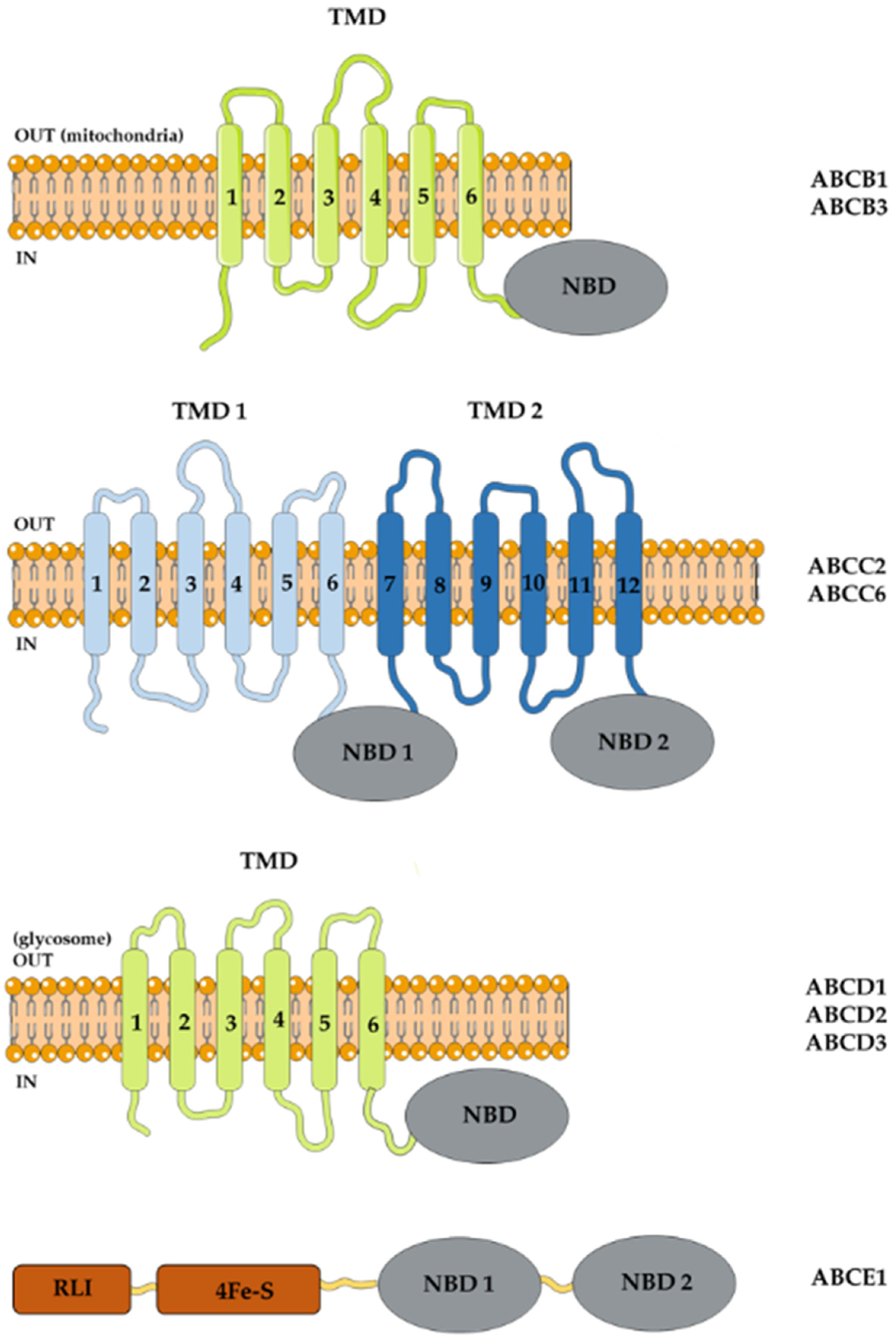

2. ABC Transporters

ABC Modulators

3. Human Pathogens of the Trypanosoma Genus

3.1. T. cruzi

3.2. T. brucei

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| ABC | ATP-binding cassette |

| ABCA1 | Subfamily A, member 1 |

| ABCA3 | Subfamily A, member 3 |

| ABCB1 | Subfamily B, member 1 |

| ABCB10 | Subfamily B, member 10 |

| ABCB3 | Subfamily B, member 3 |

| ABCB7 | Subfamily B, member 7 |

| ABCC1 | Subfamily C, member 1 |

| ABCC2 | Subfamily C, member 2 |

| ABCC6 | Subfamily C, member 6 |

| ABCD1 | Subfamily D, member 1 |

| ABCD2 | Subfamily D, member 2 |

| ABCD3 | Subfamily D, member 3 |

| ABCE1 | Subfamily E, member 1 |

| ABCG1 | Subfamily G, member 1 |

| ABCG2 | Subfamily G, member 2 |

| ABCP | ABC placental protein |

| Atm1 | Mitochondrial ABC transporter 1 |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BCRP | Breast cancer resistance protein |

| BSO | Butionine sulfoximine |

| CCCP | Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine |

| CFDA | 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate |

| CsA | Cyclosporin A |

| DTU | Discrete typing unit |

| FTC | Fumitremorgin C |

| GAT | Glycosomal ABC transporter (GAT) |

| GPG | P-glycoprotein |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSSG | Glutathione disulfide |

| HUGO | Human Genome Organization |

| IC50 | Half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| Ko143 | (3S,6S,12aS)-1,2,3,4,6,7,12,12a-Octahydro-9-methoxy-6-(2-methylpropyl)-1,4-dioxopyrazino[1′,2′1,6]pyrido[3,4-b]indole-3-propanoic acid 1,1-dimethylethyl ester |

| LTC4 | Leukotriene C4 |

| Mdl | Multidrug resistance-like |

| MDR | Multidrug resistance |

| MDR1 | Multidrug resistance protein 1 (MDR1) |

| MK-571 | L-660711, 5-(3-(2-(7-Chloroquinolin-2-yl)ethenyl)phenyl)-8-dimethylcarbamyl-4,6-dithiaoctanoic acid |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| MRP1 | Multidrug resistance protein 1 |

| MXR | Mitoxantrone resistance protein |

| NBD | Nucleotide-binding domain |

| NEM | N-ethylmaleimide |

| OAT | Organic anion transporter |

| ORF | Open reading frame |

| Rho 123 | Rhodamine 123 |

| RLI | Ribonuclease L inhibitor |

| RNAi | RNA interference |

| T(SH)2 | Trypanothione |

| TMD | Transmembrane domain |

| tRNA | Transporter RNA |

| VP | Verapamil |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Stuart, K.; Brun, R.; Croft, S.; Fairlamb, A.; Gurtler, R.E.; McKerrow, J.; Reed, S.; Tarleton, R. Kinetoplastids: Related protozoan pathogens, different diseases. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuma, A.A.; Dos Santos Barrias, E.; de Souza, W. Basic Biology of Trypanosoma cruzi. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2021, 27, 1671–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, R.; Stevens, J.R. Barcoding in trypanosomes. Parasitology 2018, 145, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Research priorities for Chagas disease, human African trypanosomiasis and leishmaniasis. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 2012, 975, 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Investing to Overcome the Global Impact of Neglected Tropical Diseases: Third WHO Report on Neglected Diseases 2015; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–211.

- Bernardes, L.S.; Zani, C.L.; Carvalho, I. Trypanosomatidae diseases: From the current therapy to the efficacious role of trypanothione reductase in drug discovery. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 2673–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvage, V.; Aubert, D.; Escotte-Binet, S.; Villena, I. The role of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) proteins in protozoan parasites. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2009, 167, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dassa, E. Natural history of ABC systems: Not only transporters. Essays Biochem. 2011, 50, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ter Beek, J.; Guskov, A.; Slotboom, D.J. Structural diversity of ABC transporters. J. Gen. Physiol. 2014, 143, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.; Annilo, T. Evolution of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily in vertebrates. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2005, 6, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoulou, F.L.; Kerr, I.D. ABC transporter research: Going strong 40 years on. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015, 43, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassa, E.; Bouige, P. The ABC of ABCS: A phylogenetic and functional classification of ABC systems in living organisms. Res. Microbiol. 2001, 152, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locher, K.P. Mechanistic diversity in ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, M.; Rzhetsky, A.; Allikmets, R. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. Genome Res. 2001, 11, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrier, P.J.; Bird, D.; Burla, B.; Dassa, E.; Forestier, C.; Geisler, M.; Klein, M.; Kolukisaoglu, U.; Lee, Y.; Martinoia, E.; et al. Plant ABC proteins--a unified nomenclature and updated inventory. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, C.; Aller, S.G.; Beis, K.; Carpenter, E.P.; Chang, G.; Chen, L.; Dassa, E.; Dean, M.; Duong Van Hoa, F.; Ekiert, D.; et al. Structural and functional diversity calls for a new classification of ABC transporters. FEBS Lett. 2020, 594, 3767–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juliano, R.L.; Ling, V. A surface glycoprotein modulating drug permeability in Chinese hamster ovary cell mutants. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta 1976, 455, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiebaut, F.; Tsuruo, T.; Hamada, H.; Gottesman, M.M.; Pastan, I.; Willingham, M.C. Cellular localization of the multidrug-resistance gene product P-glycoprotein in normal human tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 7735–7738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, E.M.; Deeley, R.G.; Cole, S.P. Multidrug resistance proteins: Role of P-glycoprotein, MRP1, MRP2, and BCRP (ABCG2) in tissue defense. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005, 204, 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Vilas-Boas, V.; Carmo, H.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J.; Carvalho, F.; de Lourdes Bastos, M.; Remiao, F. Modulation of P-glycoprotein efflux pump: Induction and activation as a therapeutic strategy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 149, 1–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambudkar, S.V.; Kim, I.W.; Sauna, Z.E. The power of the pump: Mechanisms of action of P-glycoprotein (ABCB1). Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 27, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, T.W.; Clarke, D.M. Recent progress in understanding the mechanism of P-glycoprotein-mediated drug efflux. J. Membr. Biol. 2005, 206, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.P.; Bhardwaj, G.; Gerlach, J.H.; Mackie, J.E.; Grant, C.E.; Almquist, K.C.; Stewart, A.J.; Kurz, E.U.; Duncan, A.M.; Deeley, R.G. Overexpression of a transporter gene in a multidrug-resistant human lung cancer cell line. Science 1992, 258, 1650–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couture, L.; Nash, J.A.; Turgeon, J. The ATP-binding cassette transporters and their implication in drug disposition: A special look at the heart. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slot, A.J.; Molinski, S.V.; Cole, S.P. Mammalian multidrug-resistance proteins (MRPs). Essays Biochem. 2011, 50, 179–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.K.; Zhou, Z.W.; Wei, M.Q.; Liu, J.P.; Zhou, S.F. Modulators of multidrug resistance associated proteins in the management of anticancer and antimicrobial drug resistance and the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2010, 10, 1732–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, S.P. Targeting multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1, ABCC1): Past, present, and future. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 54, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanssen, K.M.; Haber, M.; Fletcher, J.I. Targeting multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1)-expressing cancers: Beyond pharmacological inhibition. Drug Resist. Updat. 2021, 59, 100795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circu, M.L.; Aw, T.Y. Glutathione and apoptosis. Free. Radic. Res. 2008, 42, 689–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.P.; Deeley, R.G. Transport of glutathione and glutathione conjugates by MRP1. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2006, 27, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.A.; Yang, W.; Abruzzo, L.V.; Krogmann, T.; Gao, Y.; Rishi, A.K.; Ross, D.D. A multidrug resistance transporter from human MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 15665–15670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allikmets, R.; Schriml, L.M.; Hutchinson, A.; Romano-Spica, V.; Dean, M. A human placenta-specific ATP-binding cassette gene (ABCP) on chromosome 4q22 that is involved in multidrug resistance. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 5337–5339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miyake, K.; Mickley, L.; Litman, T.; Zhan, Z.; Robey, R.; Cristensen, B.; Brangi, M.; Greenberger, L.; Dean, M.; Fojo, T.; et al. Molecular cloning of cDNAs which are highly overexpressed in mitoxantrone-resistant cells: Demonstration of homology to ABC transport genes. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Litman, T.; Brangi, M.; Hudson, E.; Fetsch, P.; Abati, A.; Ross, D.D.; Miyake, K.; Resau, J.H.; Bates, S.E. The multidrug-resistant phenotype associated with overexpression of the new ABC half-transporter, MXR (ABCG2). J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113, 2011–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, A.; Schafer, H.J.; Hrycyna, C.A. Oligomerization of the human ABC transporter ABCG2: Evaluation of the native protein and chimeric dimers. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 10893–10904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.; Briddon, S.J.; Holliday, N.D.; Kerr, I.D. Plasma membrane dynamics and tetrameric organisation of ABCG2 transporters in mammalian cells revealed by single particle imaging techniques. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena-Solorzano, D.; Stark, S.A.; Konig, B.; Sierra, C.A.; Ochoa-Puentes, C. ABCG2/BCRP: Specific and Nonspecific Modulators. Med. Res. Rev. 2017, 37, 987–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staud, F.; Pavek, P. Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2). Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005, 37, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Schuetz, J.D.; Bunting, K.D.; Colapietro, A.M.; Sampath, J.; Morris, J.J.; Lagutina, I.; Grosveld, G.C.; Osawa, M.; Nakauchi, H.; et al. The ABC transporter Bcrp1/ABCG2 is expressed in a wide variety of stem cells and is a molecular determinant of the side-population phenotype. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 1028–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, P.; Ross, D.D.; Nakanishi, T.; Bailey-Dell, K.; Zhou, S.; Mercer, K.E.; Sarkadi, B.; Sorrentino, B.P.; Schuetz, J.D. The stem cell marker Bcrp/ABCG2 enhances hypoxic cell survival through interactions with heme. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 24218–24225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukal, S.; Guin, D.; Rawat, C.; Bora, S.; Mishra, M.K.; Sharma, P.; Paul, P.R.; Kanojia, N.; Grewal, G.K.; Kukreti, S.; et al. Multidrug efflux transporter ABCG2: Expression and regulation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 6887–6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, T.; Druley, T.E.; Stein, W.D.; Bates, S.E. From MDR to MXR: New understanding of multidrug resistance systems, their properties and clinical significance. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2001, 58, 931–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbatsch, I.L.; Sankaran, B.; Weber, J.; Senior, A.E. P-glycoprotein is stably inhibited by vanadate-induced trapping of nucleotide at a single catalytic site. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 19383–19390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, K.M.; Valente, R.C.; Salustiano, E.J.; Gentile, L.B.; Freire-de-Lima, L.; Mendonca-Previato, L.; Previato, J.O. Functional Characterization of ABCC Proteins from Trypanosoma cruzi and Their Involvement with Thiol Transport. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruo, T.; Iida, H.; Tsukagoshi, S.; Sakurai, Y. Overcoming of vincristine resistance in P388 leukemia in vivo and in vitro through enhanced cytotoxicity of vincristine and vinblastine by verapamil. Cancer Res. 1981, 41, 1967–1972. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, A.B.; Ling, V. ATPase activity of purified and reconstituted P-glycoprotein from Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 3745–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledwitch, K.V.; Gibbs, M.E.; Barnes, R.W.; Roberts, A.G. Cooperativity between verapamil and ATP bound to the efflux transporter P-glycoprotein. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 118, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotton, T.; Trompier, D.; Chang, X.B.; Di Pietro, A.; Baubichon-Cortay, H. (R)- and (S)-verapamil differentially modulate the multidrug-resistant protein MRP1. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 31542–31548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loe, D.W.; Deeley, R.G.; Cole, S.P. Verapamil stimulates glutathione transport by the 190-kDa multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 293, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dantzig, A.H.; Shepard, R.L.; Cao, J.; Law, K.L.; Ehlhardt, W.J.; Baughman, T.M.; Bumol, T.F.; Starling, J.J. Reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance by a potent cyclopropyldibenzosuberane modulator, LY335979. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 4171–4179. [Google Scholar]

- Shepard, R.L.; Cao, J.; Starling, J.J.; Dantzig, A.H. Modulation of P-glycoprotein but not MRP1- or BCRP-mediated drug resistance by LY335979. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 103, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantzig, A.H.; Law, K.L.; Cao, J.; Starling, J.J. Reversal of multidrug resistance by the P-glycoprotein modulator, LY335979, from the bench to the clinic. Curr. Med. Chem. 2001, 8, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neyfakh, A.A. Use of fluorescent dyes as molecular probes for the study of multidrug resistance. Exp. Cell Res. 1988, 174, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, A.L.; Legrand, O.; Faussat, A.M.; Perrot, J.Y.; Marie, J.P. Evaluation and comparison of MRP1 activity with three fluorescent dyes and three modulators in leukemic cell lines. Leuk. Res. 2004, 28, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.R.; Zamboni, R.; Belley, M.; Champion, E.; Charette, L.; Ford-Hutchinson, A.W.; Frenette, R.; Gauthier, J.Y.; Leger, S.; Masson, P.; et al. Pharmacology of L-660,711 (MK-571): A novel potent and selective leukotriene D4 receptor antagonist. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1989, 67, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gekeler, V.; Ise, W.; Sanders, K.H.; Ulrich, W.R.; Beck, J. The leukotriene LTD4 receptor antagonist MK571 specifically modulates MRP associated multidrug resistance. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 208, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Q.; Yang, Y.; Cai, C.Y.; Teng, Q.X.; Cui, Q.; Lin, J.; Assaraf, Y.G.; Chen, Z.S. Multidrug resistance proteins (MRPs): Structure, function and the overcoming of cancer multidrug resistance. Drug Resist. Updat. 2021, 54, 100743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benderra, Z.; Morjani, H.; Trussardi, A.; Manfait, M. Evidence for functional discrimination between leukemic cells overexpressing multidrug-resistance associated protein and P-glycoprotein. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1999, 457, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, W.; Hauptmann, E.; Elbling, L.; Vetterlein, M.; Kokoschka, E.M.; Micksche, M. Possible role of the multidrug resistance-associated protein (MRP) in chemoresistance of human melanoma cells. Int. J. Cancer 1997, 71, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.F.; Wang, L.L.; Di, Y.M.; Xue, C.C.; Duan, W.; Li, C.G.; Li, Y. Substrates and inhibitors of human multidrug resistance associated proteins and the implications in drug development. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008, 15, 1981–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robey, R.W.; Honjo, Y.; van de Laar, A.; Miyake, K.; Regis, J.T.; Litman, T.; Bates, S.E. A functional assay for detection of the mitoxantrone resistance protein, MXR (ABCG2). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2001, 1512, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honjo, Y.; Hrycyna, C.A.; Yan, Q.W.; Medina-Perez, W.Y.; Robey, R.W.; van de Laar, A.; Litman, T.; Dean, M.; Bates, S.E. Acquired mutations in the MXR/BCRP/ABCP gene alter substrate specificity in MXR/BCRP/ABCP-overexpressing cells. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 6635–6639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rabindran, S.K.; He, H.; Singh, M.; Brown, E.; Collins, K.I.; Annable, T.; Greenberger, L.M. Reversal of a novel multidrug resistance mechanism in human colon carcinoma cells by fumitremorgin C. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 5850–5858. [Google Scholar]

- Rabindran, S.K.; Ross, D.D.; Doyle, L.A.; Yang, W.; Greenberger, L.M. Fumitremorgin C reverses multidrug resistance in cells transfected with the breast cancer resistance protein. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, M.; Kuga, T. Central effects of the neurotropic mycotoxin fumitremorgin A in the rabbit (I). Effects on the spinal cord. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 1989, 50, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, M.; Suzuki, S.; Ozaki, N. Biochemical investigation on the abnormal behaviors induced by fumitremorgin A, a tremorgenic mycotoxin to mice. J. Pharm.-Dyn. 1983, 6, 748–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.D.; van Loevezijn, A.; Lakhai, J.M.; van der Valk, M.; van Tellingen, O.; Reid, G.; Schellens, J.H.; Koomen, G.J.; Schinkel, A.H. Potent and specific inhibition of the breast cancer resistance protein multidrug transporter in vitro and in mouse intestine by a novel analogue of fumitremorgin C. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2002, 1, 417–425. [Google Scholar]

- Weidner, L.D.; Zoghbi, S.S.; Lu, S.; Shukla, S.; Ambudkar, S.V.; Pike, V.W.; Mulder, J.; Gottesman, M.M.; Innis, R.B.; Hall, M.D. The Inhibitor Ko143 Is Not Specific for ABCG2. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2015, 354, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafraniec, M.J.; Szczygiel, M.; Urbanska, K.; Fiedor, L. Determinants of the activity and substrate recognition of breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2). Drug Metab. Rev. 2014, 46, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, C. Nova tripanozomiaze humana: Estudos sobre a morfolojia e o ciclo evolutivo do Schizotrypanum cruzi n. gen., n. sp., ajente etiolojico de nova entidade morbida do homem. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1909, 1, 159–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, C. Nova entidade morbida do homem: Rezumo geral de estudos etiolojicos e clinicos. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1911, 3, 219–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bern, C.; Messenger, L.A.; Whitman, J.D.; Maguire, J.H. Chagas Disease in the United States: A Public Health Approach. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 33, e00023–e0002319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarner, J. Chagas disease as example of a reemerging parasite. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2019, 36, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coura, J.R. Chagas disease: What is known and what is needed--a background article. Mem. Do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2007, 102 (Suppl. S1), 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bern, C. Chagas’ Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.D.F.; Nagao-Dias, A.T.; De Pontes, V.M.O.; Júnior, A.S.D.S.; Coelho, H.L.L.; Coelho, I.C.B. Tratamento etiológico da doença de Chagas no Brasil. Rev. Patol. Trop. 2008, 37, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Le Loup, G.; Pialoux, G.; Lescure, F.X. Update in treatment of Chagas disease. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 24, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassi, A., Jr.; Rassi, A.; Marcondes de Rezende, J. American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease). Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 26, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manne-Goehler, J.; Umeh, C.A.; Montgomery, S.P.; Wirtz, V.J. Estimating the Burden of Chagas Disease in the United States. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0005033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herreros-Cabello, A.; Callejas-Hernandez, F.; Girones, N.; Fresno, M. Trypanosoma Cruzi Genome: Organization, Multi-Gene Families, Transcription, and Biological Implications. Genes 2020, 11, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.D.; Llewellyn, M.S.; Gaunt, M.W.; Yeo, M.; Carrasco, H.J.; Miles, M.A. Flow cytometric analysis and microsatellite genotyping reveal extensive DNA content variation in Trypanosoma cruzi populations and expose contrasts between natural and experimental hybrids. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009, 39, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingales, B.; Andrade, S.G.; Briones, M.R.; Campbell, D.A.; Chiari, E.; Fernandes, O.; Guhl, F.; Lages-Silva, E.; Macedo, A.M.; Machado, C.R.; et al. A new consensus for Trypanosoma cruzi intraspecific nomenclature: Second revision meeting recommends TcI to TcVI. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2009, 104, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breniere, S.F.; Waleckx, E.; Barnabe, C. Over Six Thousand Trypanosoma cruzi Strains Classified into Discrete Typing Units (DTUs): Attempt at an Inventory. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filardi, L.S.; Brener, Z. Susceptibility and natural resistance of Trypanosoma cruzi strains to drugs used clinically in Chagas disease. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1987, 81, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, R.A.; van Bueren, J.; McCoy, N.G.; Iwobi, M. Reversal of drug resistance in Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania donovani by verapamil. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1989, 83, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, M.; Fase-Fowler, F.; Borst, P. The amplified H circle of methotrexate-resistant leishmania tarentolae contains a novel P-glycoprotein gene. EMBO J. 1990, 9, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallagiovanna, B.; Castanys, S.; Gamarro, F. Trypanosoma cruzi: Sequence of the ATP-binding site of a P-glycoprotein gene. Exp. Parasitol. 1994, 79, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallagiovanna, B.; Gamarro, F.; Castanys, S. Molecular characterization of a P-glycoprotein-related tcpgp2 gene in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1996, 75, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irigoin, F.; Cibils, L.; Comini, M.A.; Wilkinson, S.R.; Flohe, L.; Radi, R. Insights into the redox biology of Trypanosoma cruzi: Trypanothione metabolism and oxidant detoxification. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.; Barreiro, L.; Dallagiovanna, B.; Gamarro, F.; Castanys, S. Characterization of a new ATP-binding cassette transporter in Trypanosoma cruzi associated to a L1Tc retrotransposon. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1489, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Maranon, C.; Olivares, M.; Alonso, C.; Lopez, M.C. Characterization of a non-long terminal repeat retrotransposon cDNA (L1Tc) from Trypanosoma cruzi: Homology of the first ORF with the ape family of DNA repair enzymes. J. Mol. Biol. 1995, 247, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murta, S.M.; Gazzinelli, R.T.; Brener, Z.; Romanha, A.J. Molecular characterization of susceptible and naturally resistant strains of Trypanosoma cruzi to benznidazole and nifurtimox. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1998, 93, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murta, S.M.; dos Santos, W.G.; Anacleto, C.; Nirde, P.; Moreira, E.S.; Romanha, A.J. Drug resistance in Trypanosoma cruzi is not associated with amplification or overexpression of P-glycoprotein (PGP) genes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2001, 117, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leprohon, P.; Legare, D.; Girard, I.; Papadopoulou, B.; Ouellette, M. Modulation of Leishmania ABC protein gene expression through life stages and among drug-resistant parasites. Eukaryot. Cell 2006, 5, 1713–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.; Perez-Victoria, F.J.; Parodi-Talice, A.; Castanys, S.; Gamarro, F. Characterization of an ABCA-like transporter involved in vesicular trafficking in the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 632–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasello, M.; Giudice, A.M.; Scotlandi, K. The ABC subfamily A transporters: Multifaceted players with incipient potentialities in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 60, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, K.E.; Menendez Bravo, S.M.; Cricco, J.A. Role of heme and heme-proteins in trypanosomatid essential metabolic pathways. Enzym. Res. 2011, 2011, 873230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, F.A.; Sant’anna, C.; Lemos, D.; Laranja, G.A.; Coelho, M.G.; Reis Salles, I.; Michel, A.; Oliveira, P.L.; Cunha, E.S.N.; Salmon, D.; et al. Heme requirement and intracellular trafficking in Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 355, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, W. ABC transporter-mediated uptake of iron, siderophores, heme and vitamin B12. Res. Microbiol. 2001, 152, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, P.C.; Du, G.; Fukuda, Y.; Sun, D.; Sampath, J.; Mercer, K.E.; Wang, J.; Sosa-Pineda, B.; Murti, K.G.; Schuetz, J.D. Identification of a mammalian mitochondrial porphyrin transporter. Nature 2006, 443, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borel, J.F.; Feurer, C.; Gubler, H.U.; Stahelin, H. Biological effects of cyclosporin A: A new antilymphocytic agent. Agents Actions 1976, 6, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, L.M.; Sweet, P.; Stupecky, M.; Gupta, S. Cyclosporin A reverses vincristine and daunorubicin resistance in acute lymphatic leukemia in vitro. J. Clin. Investig. 1986, 77, 1405–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamai, I.; Safa, A.R. Competitive interaction of cyclosporins with the Vinca alkaloid-binding site of P-glycoprotein in multidrug-resistant cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 16509–16513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawarode, A.; Shukla, S.; Minderman, H.; Fricke, S.M.; Pinder, E.M.; O’Loughlin, K.L.; Ambudkar, S.V.; Baer, M.R. Differential effects of the immunosuppressive agents cyclosporin A, tacrolimus and sirolimus on drug transport by multidrug resistance proteins. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2007, 60, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, M.; O’Loughlin, K.L.; Fricke, S.M.; Williamson, N.A.; Greco, W.R.; Minderman, H.; Baer, M.R. Cyclosporin A is a broad-spectrum multidrug resistance modulator. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 2320–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, F.A. Cyclooxygenase enzymes: Regulation and function. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2004, 10, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, G.; Wielinga, P.; Zelcer, N.; van der Heijden, I.; Kuil, A.; de Haas, M.; Wijnholds, J.; Borst, P. The human multidrug resistance protein MRP4 functions as a prostaglandin efflux transporter and is inhibited by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 9244–9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasrampuria, D.A.; Lantz, M.V.; Benet, L.Z. A human lymphocyte based ex vivo assay to study the effect of drugs on P-glycoprotein (P-gp) function. Pharm. Res. 2001, 18, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Lai, Y.; Rodrigues, A.D. Organic Anion Transporter 2: An Enigmatic Human Solute Carrier. Drug Metab. Dispos. Biol. Fate Chem. 2017, 45, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, R.E.; Remington, J.S.; Araujo, F.G. In vivo and in vitro effects of cyclosporin A on Trypanosoma cruzi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1985, 34, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bua, J.; Ruiz, A.M.; Potenza, M.; Fichera, L.E. In vitro anti-parasitic activity of Cyclosporin A analogs on Trypanosoma cruzi. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 4633–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bua, J.; Fichera, L.E.; Fuchs, A.G.; Potenza, M.; Dubin, M.; Wenger, R.O.; Moretti, G.; Scabone, C.M.; Ruiz, A.M. Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi effects of cyclosporin A derivatives: Possible role of a P-glycoprotein and parasite cyclophilins. Parasitology 2008, 135, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.C.; Castro-Pinto, D.B.; Ribeiro, G.A.; Berredo-Pinho, M.M.; Gomes, L.H.; da Silva Bellieny, M.S.; Goulart, C.M.; Echevarria, A.; Leon, L.L. P-glycoprotein efflux pump plays an important role in Trypanosoma cruzi drug resistance. Parasitol. Res. 2013, 112, 2341–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.O.; Echevarria, A.; Bellieny, M.S.; Pinho, R.T.; de Leo, R.M.; Seguins, W.S.; Machado, G.M.; Canto-Cavalheiro, M.M.; Leon, L.L. Evaluation of thiosemicarbazones and semicarbazones as potential agents anti-Trypanosoma cruzi. Exp. Parasitol. 2011, 129, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingales, B.; Araujo, R.G.; Moreno, M.; Franco, J.; Aguiar, P.H.; Nunes, S.L.; Silva, M.N.; Ienne, S.; Machado, C.R.; Brandao, A. A novel ABCG-like transporter of Trypanosoma cruzi is involved in natural resistance to benznidazole. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2015, 110, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.; Ferreira, R.C.; Ienne, S.; Zingales, B. ABCG-like transporter of Trypanosoma cruzi involved in benznidazole resistance: Gene polymorphisms disclose inter-strain intragenic recombination in hybrid isolates. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015, 31, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petravicius, P.O.; Costa-Martins, A.G.; Silva, M.N.; Reis-Cunha, J.L.; Bartholomeu, D.C.; Teixeira, M.M.G.; Zingales, B. Mapping benznidazole resistance in trypanosomatids and exploring evolutionary histories of nitroreductases and ABCG transporter protein sequences. Acta Trop. 2019, 200, 105161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, K.M.; Salustiano, E.J.; Valente, R.D.C.; Freire-de-Lima, L.; Mendonca-Previato, L.; Previato, J.O. Intrinsic and Chemotherapeutic Stressors Modulate ABCC-Like Transport in Trypanosoma cruzi. Molecules 2021, 26, 3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E. Preliminary Note upon A Trypanosome Occurring in the Blood of Man; Liverpool University Press: Liverpool, UK, 1902; pp. 455–468. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, J.W.W.; Fantham, H. On the Peculiar Morphology of a Trypanosome From a Case of Sleeping Sickness and the Possibility of Its Being a New Species (T. Rhodesiense). Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1910, 4, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottieau, E.; Clerinx, J. Human African Trypanosomiasis: Progress and Stagnation. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 33, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Number of New Reported Cases of Human African Trypanosomiasis. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/human-african-trypanosomiasis (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Franco, J.R.; Cecchi, G.; Priotto, G.; Paone, M.; Diarra, A.; Grout, L.; Simarro, P.P.; Zhao, W.; Argaw, D. Monitoring the elimination of human African trypanosomiasis at continental and country level: Update to 2018. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasozi, K.I.; MacLeod, E.T.; Ntulume, I.; Welburn, S.C. An Update on African Trypanocide Pharmaceutics and Resistance. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 828111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Gupta, S.; Bhutia, W.D.; Vaid, R.K.; Kumar, S. Atypical human trypanosomosis: Potentially emerging disease with lack of understanding. Zoonoses Public Health 2022, 69, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscher, P.; Cecchi, G.; Jamonneau, V.; Priotto, G. Human African trypanosomiasis. Lancet 2017, 390, 2397–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarshi, D.; Lawrence, S.; Pickrell, W.O.; Eligar, V.; Walters, R.; Quaderi, S.; Walker, A.; Capewell, P.; Clucas, C.; Vincent, A.; et al. Human African trypanosomiasis presenting at least 29 years after infection—What can this teach us about the pathogenesis and control of this neglected tropical disease? PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamonneau, V.; Ilboudo, H.; Kabore, J.; Kaba, D.; Koffi, M.; Solano, P.; Garcia, A.; Courtin, D.; Laveissiere, C.; Lingue, K.; et al. Untreated human infections by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense are not 100% fatal. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checchi, F.; Funk, S.; Chandramohan, D.; Haydon, D.T.; Chappuis, F. Updated estimate of the duration of the meningo-encephalitic stage in gambiense human African trypanosomiasis. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.R.; Simarro, P.P.; Diarra, A.; Jannin, J.G. Epidemiology of human African trypanosomiasis. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 6, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappuis, F.; Udayraj, N.; Stietenroth, K.; Meussen, A.; Bovier, P.A. Eflornithine is safer than melarsoprol for the treatment of second-stage Trypanosoma brucei gambiense human African trypanosomiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, 748–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, J.; Ortiz, J.F.; Fabara, S.P.; Eissa-Garces, A.; Reddy, D.; Collins, K.D.; Tirupathi, R. Efficacy and Toxicity of Fexinidazole and Nifurtimox Plus Eflornithine in the Treatment of African Trypanosomiasis: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2021, 13, e16881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, R.J.; Gull, K.; Sunter, J.D. Coordination of the Cell Cycle in Trypanosomes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 73, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, J.F.; Zoltner, M.; Field, M.C. Evolving Differentiation in African Trypanosomes. Trends Parasitol. 2021, 37, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweygarth, E.; Rottcher, D. Efficacy of experimental trypanocidal compounds against a multiple drug-resistant Trypanosoma brucei brucei stock in mice. Parasitol. Res. 1989, 75, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, R.; Zweygarth, E. The effect of verapamil alone and in combination with trypanocides on multidrug-resistant Trypanosoma brucei brucei. Acta Trop. 1991, 49, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maser, P.; Kaminsky, R. Identification of three ABC transporter genes in Trypanosoma brucei spp. Parasitol. Res. 1998, 84, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi, S.K.; Krauth-Siegel, R.L.; Clayton, C.E. Overexpression of the putative thiol conjugate transporter TbMRPA causes melarsoprol resistance in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 43, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luscher, A.; Nerima, B.; Maser, P. Combined contribution of TbAT1 and TbMRPA to drug resistance in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2006, 150, 364–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quentmeier, A.; Klein, H.; Unthan-Fechner, K.; Probst, I. Attenuation of insulin actions in primary rat hepatocyte cultures by phenylarsine oxide. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 1993, 374, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibu, V.P.; Richter, C.; Voncken, F.; Marti, G.; Shahi, S.; Renggli, C.K.; Seebeck, T.; Brun, R.; Clayton, C. The role of Trypanosoma brucei MRPA in melarsoprol susceptibility. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2006, 146, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez, A.M.; Haile, S.; Steinbuchel, M.; Quijada, L.; Clayton, C. Effects of depletion and overexpression of the Trypanosoma brucei ribonuclease L inhibitor homologue. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2004, 133, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yernaux, C.; Fransen, M.; Brees, C.; Lorenzen, S.; Michels, P.A. Trypanosoma brucei glycosomal ABC transporters: Identification and membrane targeting. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2006, 23, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyersoen, J.; Choe, J.; Fan, E.; Hol, W.G.; Michels, P.A. Biogenesis of peroxisomes and glycosomes: Trypanosomatid glycosome assembly is a promising new drug target. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 28, 603–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igoillo-Esteve, M.; Mazet, M.; Deumer, G.; Wallemacq, P.; Michels, P.A. Glycosomal ABC transporters of Trypanosoma brucei: Characterisation of their expression, topology and substrate specificity. Int. J. Parasitol. 2011, 41, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horakova, E.; Changmai, P.; Paris, Z.; Salmon, D.; Lukes, J. Simultaneous depletion of Atm and Mdl rebalances cytosolic Fe-S cluster assembly but not heme import into the mitochondrion of Trypanosoma brucei. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 4157–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kispal, G.; Csere, P.; Prohl, C.; Lill, R. The mitochondrial proteins Atm1p and Nfs1p are essential for biogenesis of cytosolic Fe/S proteins. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 3981–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschner, J.; Lachmann, N.; Schulze, J.; Geisler, M.; Selbach, K.; Santamaria-Araujo, J.; Balk, J.; Mendel, R.R.; Bittner, F. A novel role for Arabidopsis mitochondrial ABC transporter ATM3 in molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taketani, S.; Kakimoto, K.; Ueta, H.; Masaki, R.; Furukawa, T. Involvement of ABC7 in the biosynthesis of heme in erythroid cells: Interaction of ABC7 with ferrochelatase. Blood 2003, 101, 3274–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| ABCB1 | ABCC1 | ABCG2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLUORESCENT SUBSTRATE | Rhodamine 123 | CFDA | Mitoxantrone |

| SELECTIVE INHIBITOR | Zosuquidar | MK-571 | Ko-143 |

| ATPASE ACTIVITY INHIBITOR | Vanadate | ||

| ATP DEPLETION | Sodium azide, dinitrophenol, CCCP | ||

| THIOL DEPLETION | Iodoacetic acid, N-ethylmaleimide, Buthionine sulfoximine | ||

| Nomenclature | T. cruzi Gene ID | NCBI Reference Sequences | Location | Putative Protein Length | T. cruzi Strain | Alias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCA1 | TcCLB.504881.50 * | XP_809857 | TcChr27 | 1750 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.510045.20 * | XP_806887 | TcChr27 | 967 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| ABCA2/4 | TcCLB.507099.80 (a) | XP_817325 | TcChr14 | 1836 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| ABCA3/5 | TcCLB.504149.20 * (b) | XP_818098 | TcChr27 | 1750 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | ABC1 [94] |

| TcCLB.503573.9 * (c) | XP_803907 | TcChr27 | 967 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| ABCA10 | TcCLB.510149.80 * | XP_813909 | TcChr36 | 1865 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.506989.30 * | XP_818638 | TcChr36 | 1866 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| ABCA11 | TcCLB.511725.80 | XP_818719 | TcChr35 | 2260 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | |

| ABCB1 | TcCLB.507093.260 | XP_820554 | TcChr39 | 661 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| ABCB3 | TcCLB.511537.8 * | XP_806158 XP_809384 | TcChr35 | 537 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.511021.70 * | XP_811319 | TcChr35 | 735 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| ABCC1/2 | TcCLB.506417.10 (d) pseudogene | - | ? | 1577 | CL Brener | Tcpgp2 [86] |

| ABCC6 | TcCLB.509007.99 pseudogene | - | TcChr31 | 1425 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.507079.30 * | XP_805658 | TcChr31 | 388 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | ||

| TcCLB.457101.30 * | XP_805394 | ? | 253 | CL Brener | ||

| TcCLB.508965.14 * | XP_815145 | TcChr31 | 765 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | Tcpgp1 [86] | |

| ABCC9 | TcCLB.510231.29 * | XP_805357 | TcChr34 | 854 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.447255.29 * | XP_803480 | TcChr34 | 220 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | ||

| TcCLB.506559.100 * | XP_821792 | TcChr34 | 1472 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| ABCD1 | TcCLB.506925.530 | XP_821597 | TcChr39 | 664 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| ABCD2 | TcCLB.508927.20 * | XP_804559 | TcChr31 | 674 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.509237.30 * | XP_814630 | TcChr31 | 674 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| ABCD3 | TcCLB.510431.150 | XP_819234 | TcChr39 | 635 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| ABCE1 | TcCLB.508637.150 * | XP_815243 | TcChr10 | 647 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.511913.9 pseudogene | - | TcChr10 | 418 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| TcCLB.464879.9 * | XP_802148 | TcChr10 | 339 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| ABCF1 | TcCLB.504867.20 * | XP_812776 | TcChr36 | 723 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.510943.80 * | XP_817081 | TcChr36 | 723 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| ABCF2 | TcCLB.508897.30 | XP_810886 | TcChr40 | 594 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | |

| ABCF3 | TcCLB.509105.130 | XP_814891 | TcChr37 | 673 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | |

| ABCG1/2 | TcCLB.506249.70 * (e) | XP_806666 | TcChr37 | 665 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.508231.190 * (f) | XP_818614 | TcChr37 | 665 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ABCG1 [114] | |

| ABCG3 | TcCLB.506249.70 * (e) | XP_806666 | TcChr37 | 665 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.508231.190 * (f) | XP_818614 | TcChr37 | 665 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| ABCG4 | TcCLB.506579.10 * | XP_811527 | TcChr7 | 700 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.507241.39 * | XP_806410 | TcChr7 | 290 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| ABCG5 | TcCLB.504425.70 * | XP_813191 | TcChr22 | 1171 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.509331.200 * | XP_816786 | TcChr22 | 1170 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| ABCG6 | TcCLB.507681.100 | XP_818599 | TcChr4 | 682 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | |

| ABCH1 | TcCLB.510381.20 * | XP_807302 | TcChr27 | 303 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.506905.40 * | XP_806924 | TcChr27 | 303 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| ABCH2 | TcCLB.509669.30 * | XP_816112 | TcChr36 | 318 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.509617.80 * | XP_809836 | TcChr36 | 318 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| ABCH3 | TcCLB.511753.100 * | XP_812902 | TcChr32 | 496 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.511501.30 * | XP_805965 | TcChr32 | 502 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| OTHERS | TcCLB.506529.160 * | XP_821943 | TcChr6 | 937 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.510885.70 * | XP_816152 | TcChr6 | 937 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| OTHERS | TcCLB.508809.30 * | XP_809200 | TcChr23 | 1241 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.506619.90 * | XP_812627 | TcChr23 | 1241 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like | ||

| OTHERS | TcCLB.507105.70 * | XP_811423 | TcChr35 | 1027 | CL Brener Esmeraldo-like | |

| TcCLB.506817.20 * | XP_809803 | TcChr35 | 999 | CL Brener Non-Esmeraldo-like |

| Nomenclature | T. brucei Gene ID | NCBI Reference Sequences | Location | Putative Protein Length | T. Brucei Strain | Alias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABCA3 | Tb927.11.6120 | XP_828686.1 | TbChr11 | 1738 | brucei TREU927 | |

| ABCA10 | Tb927.3.3730 | XP_843965.1 | TbChr03 | 1845 | brucei TREU927 | |

| ABCB1 | Tb927.11.540.2 | XP_828146.1 | TbChr11 | 665 | brucei TREU927 | TbMdl [145] |

| ABCB3 | Tb927.11.16930 | XP_829749.1 | TbChr11 | 719 | brucei TREU927 | TbAtm [145] |

| ABCC1/2 | Tb927.8.2160 | XP_847049.1 | TbChr08 | 1581 | brucei TREU927 | TbMRPA [137] |

| ABCC6 | Tb927.4.4490 | XP_844598.1 | TbChr04 | 1759 | brucei TREU927 | TbMRPE [137] |

| ABCC9 | Tb927.4.2510 | XP_844401.1 | TbChr04 | 1503 | brucei TREU927 | |

| ABCD1 | Tb927.11.1070 | XP_828200.1 | TbChr11 | 684 | brucei TREU927 | TbGAT3 [142] |

| ABCD2 | Tb927.4.4050 | XP_844555.1 | TbChr04 | 683 | brucei TREU927 | TbGAT1 [142] |

| ABCD3 | Tb927.11.3130 | XP_828395.1 | TbChr11 | 641 | brucei TREU927 | TbGAT2 [142] |

| ABCE1 | Tb927.10.1630 | XP_822420.1 | TbChr10 | 631 | brucei TREU927 | TbRLI [141] |

| ABCF1 | Tb927.10.3170 | XP_822569.1 | TbChr10 | 723 | brucei TREU927 | |

| ABCF2 | Tb927.10.15530 | XP_828024.1 | TbChr10 | 602 | brucei TREU927 | |

| ABCF3 | Tb927.10.10880 | XP_823306.1 | TbChr10 | 684 | brucei TREU927 | |

| ABCG1/2/3 | Tb927.10.7700 | XP_823004.1 | TbChr10 | 668 | brucei TREU927 | |

| ABCG4 | Tb927.9.6310 | XP_011776526.1 | TbChr09 | 646 | brucei TREU927 | |

| ABCG5 | Tb927.8.2380 | XP_847071.1 | TbChr08 | 1158 | brucei TREU927 | |

| ABCG6 | Tb927.10.7360 | XP_822971.1 | TbChr10 | 646 | brucei TREU927 | |

| ABCH3 | Tb927.6.2810 | XP_845402.1 | TbChr06 | 524 | brucei TREU927 | |

| OTHERS | Tb927.1.4420 | XP_001219135.1 | TbChr01 | 945 | brucei TREU927 | |

| OTHERS | Tb927.2.5410 | XP_951709.1 | TbChr02 | 1281 | brucei TREU927 | |

| OTHERS | Tb927.2.6130 | XP_951745.1 | TbChr02 | 1006 | brucei TREU927 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

da Costa, K.M.; Valente, R.d.C.; Fonseca, L.M.d.; Freire-de-Lima, L.; Previato, J.O.; Mendonça-Previato, L. The History of the ABC Proteins in Human Trypanosomiasis Pathogens. Pathogens 2022, 11, 988. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11090988

da Costa KM, Valente RdC, Fonseca LMd, Freire-de-Lima L, Previato JO, Mendonça-Previato L. The History of the ABC Proteins in Human Trypanosomiasis Pathogens. Pathogens. 2022; 11(9):988. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11090988

Chicago/Turabian Styleda Costa, Kelli Monteiro, Raphael do Carmo Valente, Leonardo Marques da Fonseca, Leonardo Freire-de-Lima, Jose Osvaldo Previato, and Lucia Mendonça-Previato. 2022. "The History of the ABC Proteins in Human Trypanosomiasis Pathogens" Pathogens 11, no. 9: 988. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11090988

APA Styleda Costa, K. M., Valente, R. d. C., Fonseca, L. M. d., Freire-de-Lima, L., Previato, J. O., & Mendonça-Previato, L. (2022). The History of the ABC Proteins in Human Trypanosomiasis Pathogens. Pathogens, 11(9), 988. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11090988