The Circulation of Type F Clostridium perfringens among Humans, Sewage, and Ruditapes philippinarum (Asari Clams)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Distribution of Type F C. perfringens

2.2. Characterization of Type F C. perfringens by Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection

4.2. Isolation of Clostridium Perfringens

4.3. Human Isolates

4.4. Characterization of the Isolates

4.5. Statistical Analysis

4.6. MLST Analysis

4.7. Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rood, J.I.; Adams, V.; Lacey, J.; Lyras, D.; McClane, B.A.; Melville, S.B.; Moore, R.J.; Popoff, M.R.; Sarker, M.R.; Songer, J.G.; et al. Expansion of the Clostridium perfringens toxin-based typing scheme. Anaerobe 2018, 53, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW). Statistics of Food Poisoning in Japan. Available online: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/shokuhin/syokuchu/04.html (accessed on 12 March 2020). (In Japanese).

- Moffatt, C.R.; Howard, P.J.; Burns, T. A mild outbreak of gastroenteritis in long-term care facility residents due to Clostridium perfringens, Australia 2009. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2011, 8, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallis, G.; Ng, S.; Ferreira, C.; Tan, A.; Griffith, J. A nursing home outbreak of Clostridium perfringens associated with pureed food. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 1999, 23, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochiai, H.; Ohtsu, T.; Tsuda, T.; Kagawa, H.; Kawashita, T.; Takao, S.; Tsutsumi, A.; Kawakami, N. Clostridium perfringens foodborne outbreak due to braised chop suey supplied by chafing dish. Acta Med. Okayama 2005, 59, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borriello, S.P.; Larson, H.E.; Welch, A.R.; Barclay, F.; Stringer, M.F.; Bartholomew, B.A. Enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens: A possible cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Lancet 1984, 323, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, M.M.; Rodhouse, J.C.; Donovan, T.J.; Tebbutt, G.M.; Hutchinson, D.N. Detection of Clostridium perfringens and its enterotoxin in cases of sporadic diarrhoea. J. Clin. Pathol. 1992, 45, 609–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jackson, S.G.; Yip-Chuck, D.A.; Clark, J.B.; Brodsky, M.H. Diagnostic importance of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin analysis in recurring enteritis among elderly, chronic care psychiatric patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1986, 23, 748–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heikinheimo, A.; Lindström, M.; Granum, P.E.; Korkeala, H. Humans as reservoir for enterotoxin gene-carrying Clostridium perfringens type A. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1724–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carman, R.J.; Sayeed, S.; Li, J.; Genheimer, C.W.; Hiltonsmith, M.F.; Wilkins, T.D.; McClane, B.A. Clostridium perfringens toxin genotypes in the feces of healthy North Americans. Anaerobe 2008, 14, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindström, M.; Heikinheimo, A.; Lahti, P.; Korkeala, H. Novel insights into the epidemiology of Clostridium perfringens type A food poisoning. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, J.P.; Das, S.C.; Dhaka, P.; Vijay, D.; Kumar, M.; Mukhopadhyay, A.K.; Chowdhury, G.; Chauhan, P.; Singh, R.; Dhama, K.; et al. Molecular characterization and antimicrobial resistance profile of Clostridium perfringens type a isolates from humans, animals, fish and their environment. Anaerobe 2017, 47, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Rafii, F. The prevalence of plasmid-coded CPE enterotoxin, β2 toxin, tpeL toxin, and tetracycline resistance in Clostridium perfringens strains isolated from different sources. Anaerobe 2019, 56, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Q.; McClane, B.A. Detection of enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens type A isolates in American retail foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 2685–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miki, Y.; Miyamoto, K.; Kaneko-Hirano, I.; Fujiuchi, K.; Akimoto, S. Prevalence and characterization of enterotoxin gene-carrying Clostridium perfringens isolates from retail meat products in Japan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 5366–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saito, M. Production of Enterotoxin by Clostridium perfringens derived from humans, animals, foods, and the natural environment in Japan. J. Food Prot. 1990, 53, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller-Spitz, S.R.; Stewart, L.B.; Klump, J.V.; McLellan, S.L. Freshwater suspended sediments and sewage are reservoirs for enterotoxin-positive Clostridium perfringens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 5556–5562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hashimoto, A.; Tsuchioka, H.; Higashi, K.; Ota, N.; Harada, H. Distribution of enterotoxin gene-positive Clostridium perfringens spores among human and livestock samples and its potential as a human fecal source tracking indicator. J. Water. Environ. Technol. 2016, 14, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oka, S.; Ando, Y.; Oishi, K. Distribution of enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens in fish and shellfish. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi 1989, 55, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sayeed, S.; McClane, B.A. Prevalence of enterotoxigenic clostridium perfringens isolates in pittsburgh (pennsylvania) area soils and home kitchens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 7218–7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahmati, T.; Labbe, R. Levels and toxigenicity of Bacillus cereus and Clostridium perfringens from retail seafood. J. Food Prot. 2008, 71, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Pierce, M.R.; Rhoads, N.A. Clostridium perfringens testing improves the reliability of detecting non-point source sewage contamination in Hawaiian coastal waters compared to using Enterococci alone. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 144, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelma, G.N., Jr. Use of bacterial spores in monitoring water quality and treatment. J. Water Health 2018, 164, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muniain-Mujika, I.; Calvo, M.; Lucena, F.; Girones, R. Comparative analysis of viral pathogens and potential indicators in shellfish. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 83, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaas, L.; Ogorzaly, L.; Lecellier, G.; Berteaux-Lecellier, V.; Cauchie, H.M.; Langlet, J. Detection of human enteric viruses in French Polynesian wastewaters, environmental waters and giant clams. Food Environ. Virol. 2019, 11, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onosi, O.; Upfold, N.S.; Jukes, M.D.; Luke, G.A.; Knox, C. The first molecular detection of aichi virus 1 in raw sewage and mussels collected in South Africa. Food Environ. Virol. 2019, 11, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, R.; Ono, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Wada, Y.; Nishizawa, K.; Fujii, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Kuroiwa, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ishii, K.; et al. A cluster of hepatitis A infections presumed to be related to asari clams and investigation of the spread of viral contamination from asari clams. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 72, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nishigata, T.; Oonuma, M. Survey of the viral contamination in shellfish supplied in Yanamashi Prefecture (In Japanese). Annu. Rep. Yamanashi Inst. Pub. Health 2017, 61, 47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf, T.G.; Mullin, B.; Eckerson, D.; Moulton, E.; Larkin, E.P. Bioaccumulation and depuration of enteroviruses by the soft-shelled clam. Mya arenaria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1979, 38, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burkhardt, W., 3rd; Watkins, W.D.; Rippey, S.R. Seasonal effects on accumulation of microbial indicator organisms by Mercenaria mercenaria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rippey, S.R. Infectious diseases associated with molluscan shellfish consumption. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1994, 7, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, W., 3rd; Calci, K.R. Selective accumulation may account for shellfish-associated viral illness. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 1375–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaeffer, J.; Treguier, C.; Piquet, J.C.; Gachelin, S.; Cochennec-Laureau, N.; Le Saux, J.C.; Garry, P.; Le Guyader, F.S. Improving the efficacy of sewage treatment decreases norovirus contamination in oysters. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 286, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tanaka, D.; Isobe, J.; Hosorogi, S.; Kimata, K.; Shimizu, M.; Katori, K.; Gyobu, Y.; Nagai, Y.; Yamagishi, T.; Karasawa, T.; et al. An outbreak of food-borne gastroenteritis caused by Clostridium perfringens carrying the cpe gene on a plasmid. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 56, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tauxe, R.V. Emerging foodborne diseases: An evolving public health challenge. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1997, 3, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yanagimoto, K.; Yamagami, T.; Uematsu, K.; Haramoto, E. Characterization of Salmonella isolates from wastewater treatment plant influents to estimate unreported cases and infection sources of salmonellosis. Pathogens 2020, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanaka, D.; Kimata, K.; Shimizu, M.; Isobe, J.; Watahiki, M.; Karasawa, T.; Yamagishi, T.; Kuramoto, S.; Serikawa, T.; Ishiguro, F.; et al. Genotyping of Clostridium perfringens isolates collected from food poisoning outbreaks and healthy individuals in Japan based on the cpe locus. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 60, 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, A.; Aung, M.S.; Urushibara, N.; Kawaguchiya, M.; Sumi, A.; Nakamura, M.; Horino, Y.; Ito, M.; Habadera, S.; Kobayashi, N. Prevalence and genetic diversity of toxin genes in clinical isolates of Clostridium perfringens: Coexistence of alpha-toxin variant and binary enterotoxin genes (bec/cpile). Toxins 2019, 11, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deguchi, A.; Miyamoto, K.; Kuwahara, T.; Miki, Y.; Kaneko, I.; Li, J.; McClane, B.A.; Akimoto, S. Genetic characterization of type A enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens strains. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiao, Y.; Wagendorp, A.; Moezelaar, R.; Abee, T.; Wells-Bennik, M.H. A wide variety of Clostridium perfringens type A food-borne isolates that carry a chromosomal cpe gene belong to one multilocus sequence typing cluster. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 7060–7068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiu, R.; Caim, S.; Painset, A.; Pickard, D.; Swift, C.; Dougan, G.; Mather, A.E.; Amar, C.; Hall, L.J. Phylogenomic analysis of gastroenteritis-associated Clostridium perfringens in England and Wales over a 7-year period indicates distribution of clonal toxigenic strains in multiple outbreaks and extensive involvement of enterotoxin-encoding (CPE) plasmids. Microb. Genom. 2019, 5, e000297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamat Abdelrahim, A.; Radomski, N.; Delannoy, S.; Djellal, S.; Le Négrate, M.; Hadjab, K.; Fach, P.; Hennekinne, J.A.; Mistou, M.Y.; Firmesse, O. Large-scale genomic analyses and toxinotyping of Clostridium perfringens implicated in foodborne outbreaks in France. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Okonogi, A.; Ishihara, Y.; Kubo, S. The relevance of Salmonella screening results for food-related workers and poultry farms in Japan (In Japanese). J. Jpn. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 29, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, D.; Fujihara, S.; Wakabayashi, A.; Okahata, K.; Suzuki, M.; Saeki, A.; Nakamura, H.; Hara-Kudo, Y.; et al. Prevalence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in foods and fecal specimens obtained from cattle, pigs, chickens, asymptomatic carriers, and patients in Osaka and Hyogo, Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 70, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matsusaki, S.; Katayama, A.; Kawaguchi, N.; Tanaka, K.; Hayashi, Y. Incidence of Campylobacter jejuni/coli from healthy people in Yamaguchi, Japan (In Japanese). Kansenshogaku Zasshi 1983, 57, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, N.; Nishina, T.; Kubo, S.; Atsumi, M.; Honda, H. Amount of enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens in meat detected by nested PCR. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1998, 42, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneim, N.H.; Hamza, D.A. Epidemiological studies on Clostridium perfringens food poisoning in retail foods. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2017, 36, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.T.; Labbe, R. Enterotoxigenicity and genetic relatedness of Clostridium perfringens isolates from retail foods in the United States. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 1642–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asakura, H.; Saito, E.; Momose, Y.; Ekawa, T.; Sawada, M.; Yamamoto, A.; Hasegawa, A.; Iwahori, J.; Tsutsui, T.; Osaka, K.; et al. Prevalence and growth kinetics of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) in bovine offal products in Japan. Epidemiol. Infect. 2012, 140, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroi, M.; Kawamori, F.; Harada, T.; Sano, Y.; Miwa, N.; Sugiyama, K.; Hara-Kudo, Y.; Masuda, T. Antibiotic resistance in bacterial pathogens from retail raw meats and food-producing animals in Japan. J. Food Prot. 2012, 75, 1774–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara-Kudo, Y.; Konuma, H.; Kamata, Y.; Miyahara, M.; Takatori, K.; Onoue, Y.; Sugita-Konishi, Y.; Ohnishi, T. Prevalence of the main food-borne pathogens in retail food under the national food surveillance system in Japan. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2012, 30, 1450–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, I.; Ishihara, T.; Teranishi, H.; Saito, S.; Yatsuyanagi, J.; Wada, E.; Kumagai, Y.; Takahashi, S.; Konno, T. Prevalence and characteristics of Salmonella and Campylobacter in retail poultry meat in Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 70, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Q.; He, X.; Yan, T. Differential decay of wastewater bacteria and change of microbial communities in beach sand and seawater microcosms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 8531–8540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Sala, L.F.; Redondo, L.M.; Díaz Carrasco, J.M.; Pereyra, A.M.; Farber, M.; Jost, H.; Fernández-Miyakawa, M.E. Carriage of Clostridium perfringens by benthic crabs in a sewage-polluted estuary. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 97, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabry, M.; Abd El-Moein, K.; Hamza, E.; Abdel Kader, F. Occurrence of Clostridium perfringens types A, E, and C in fresh fish and its public health significance. J. Food Prot. 2016, 79, 994–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, M.R.; Shivers, R.P.; Sparks, S.G.; Juneja, V.K.; McClane, B.A. Comparative experiments to examine the effects of heating on vegetative cells and spores of Clostridium perfringens isolates carrying plasmid genes versus chromosomal enterotoxin genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 3234–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakamura, M.; Kato, A.; Tanaka, D.; Gyobu, Y.; Higaki, S.; Karasawa, T.; Yamagishi, T. PCR identification of the plasmid-borne enterotoxin gene (CPE) in Clostridium perfringens strains isolated from food poisoning outbreaks. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004, 294, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Mc Clane, B.A. Further comparison of temperature effects on growth and survival of Clostridium perfringens type A isolates carrying a chromosomal or plasmid-borne enterotoxin gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 4561–4568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J.; Mc Clane, B.A. Comparative effects of osmotic, sodium nitrite-induced, and pH-induced stress on growth and survival of Clostridium perfringens type a isolates carrying chromosomal or plasmid-borne enterotoxin genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 7620–7625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miyamoto, K.; Li, J.; McClane, B.A. Enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens: Detection and identification. Microbes Environ. 2012, 27, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lahti, P.; Heikinheimo, A.; Johansson, T.; Korkeala, H. Clostridium perfringens type A strains carrying a plasmid-borne enterotoxin gene (genotype IS1151-cpe or IS1470-like-cpe) as a common cause of food poisoning. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grant, K.A.; Kenyon, S.; Nwafor, I.; Plowman, J.; Ohai, C.; Halford-Maw, R.; Peck, M.W.; McLauchlin, J. The identification and characterization of Clostridium perfringens by real-time PCR, location of enterotoxin gene, and heat resistance. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2008, 5, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shandera, W.X.; Tacket, C.O.; Blake, P.A. Food poisoning due to Clostridium perfringens in the United States. J. Infect. Dis. 1983, 147, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haramoto, E.; Fujino, S.; Otagiri, M. Distinct behaviors of infectious F-specific RNA coliphage genogroups at a wastewater treatment plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 520, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, K.; Wen, Q.; Mc Clane, B.A. Multiplex PCR genotyping assay that distinguishes between isolates of Clostridium perfringens type A carrying a chromosomal enterotoxin gene (CPE) locus, a plasmid CPE locus with an IS1470-like sequence, or a plasmid cpe locus with an IS1151 sequence. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- van Asten, A.J.; van der Wiel, C.W.; Nikolaou, G.; Houwers, D.J.; Gröne, A. A multiplex PCR for toxin typing of Clostridium perfringens isolates. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 136, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Period | cpe Genotyping Assay | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosomal cpe | IS1151-cpe | IS1470-Like-cpe | Untypable cpe | ||||||

| A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | ||

| 2016 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2017 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2018 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2019 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2020 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 60 | 63 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Period | cpe Genotyping Assay | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosomal cpe | IS1151-cpe | IS1470-Like-cpe | Untypable cpe | ||||||

| A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | ||

| 2018 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2019 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2020 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 5 | 4 | 13 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 0 | |

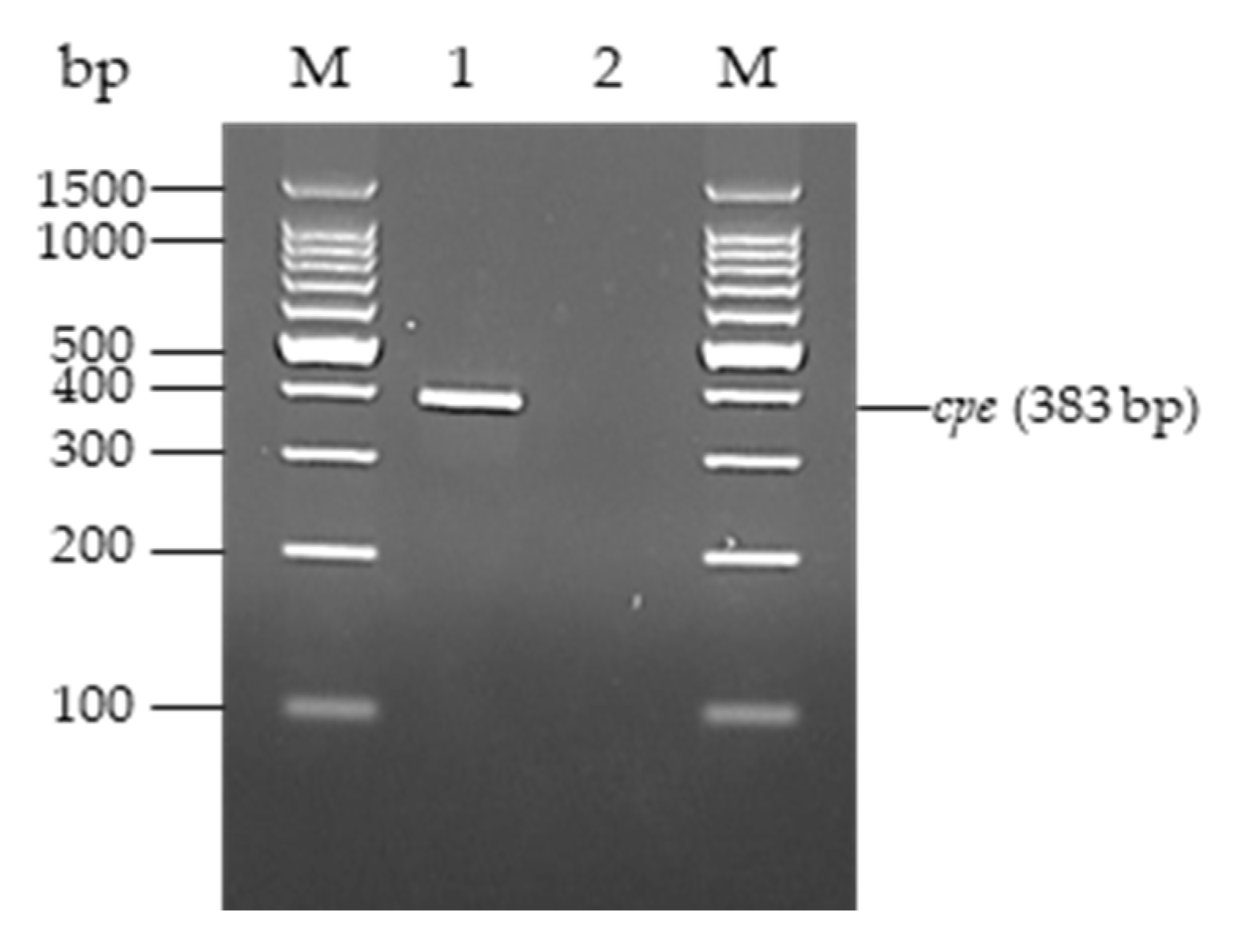

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| cpe-F | GATAAAGGAGATGGTTGGATATTAGGGGAAC | 383 |

| cpe-R | CCTAAGCTATCTGCAGATGTTTTACTAAGCC |

| Strain | Location of cpe | cpb2 | Source | Isolation Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14-12 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Human feces in non-foodborne case | June 2014 |

| 14-14 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Human feces in non-foodborne case | July 2014 |

| 18-229 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Human feces in non-foodborne case | November 2018 |

| 14-15 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Human feces in non-foodborne case | July 2014 |

| 14-133 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Human feces in non-foodborne case | December 2014 |

| 19-14 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Human feces in non-foodborne case | April 2019 |

| 16-101 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | – | Sewage influent from WWTP-A | July 2016 |

| 17-29 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | – | Sewage influent from WWTP-A | October 2016 |

| 17-82 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Sewage influent from WWTP-A | December 2016 |

| 18-101 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | – | Sewage influent from WWTP-A | January 2018 |

| 19-100 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Sewage influent from WWTP-A | June 2019 |

| 17-37 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Sewage influent from WWTP-B | November 2016 |

| 17-100 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Sewage influent from WWTP-B | December 2016 |

| 18-29 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Sewage influent from WWTP-B | July 2017 |

| 18-340 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Sewage influent from WWTP-B | November 2018 |

| 19-43 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Sewage influent from WWTP-B | March 2019 |

| 18-350 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Sewage effluent from WWTP-A | February 2019 |

| 19-16 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | – | Sewage effluent from WWTP-A | March 2019 |

| 18-353 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Sewage effluent from WWTP-B | January 2019 |

| 19-5 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | – | Sewage effluent from WWTP-B | February 2019 |

| 19-124 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Asari clam from Aichi | July 2019 |

| 19-141 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Asari clam from Aichi | August 2019 |

| 19-146 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Asari clam from Aichi | September 2019 |

| 19-169 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | – | Asari clam from Kumamoto | November 2019 |

| 19-170 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Asari clam from Kumamoto | November 2019 |

| 19-171 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Asari clam from Kumamoto | December 2019 |

| 19-172 | Plasmid with an IS1151 sequence | + | Asari clam from Kumamoto | December 2019 |

| 14-13 | Plasmid with an IS1470-like sequence | + | Human feces in non-foodborne case | June 2014 |

| 13-11 | Plasmid with an IS1470-like sequence | – | Human feces in non-foodborne case | April 2013 |

| 19-15 | Plasmid with an IS1470-like sequence | + | Human feces in non-foodborne case | April 2019 |

| 18-25 | Plasmid with an IS1470-like sequence | + | Sewage influent from WWTP-A | July 2017 |

| 17-36 | Plasmid with an IS1470-like sequence | – | Sewage influent from WWTP-B | January 2016 |

| 18-268 | Plasmid with an IS1470-like sequence | – | Sewage influent from WWTP-B | August 2018 |

| 18-262 | Plasmid with an IS1470-like sequence | – | Sewage effluent from WWTP-B | August 2018 |

| 18-289 | Plasmid with an IS1470-like sequence | – | Sewage effluent from WWTP-B | December 2018 |

| 19-62 | Plasmid with an IS1470-like sequence | – | Sewage effluent from WWTP-B | April 2019 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yanagimoto, K.; Uematsu, K.; Yamagami, T.; Haramoto, E. The Circulation of Type F Clostridium perfringens among Humans, Sewage, and Ruditapes philippinarum (Asari Clams). Pathogens 2020, 9, 669. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9080669

Yanagimoto K, Uematsu K, Yamagami T, Haramoto E. The Circulation of Type F Clostridium perfringens among Humans, Sewage, and Ruditapes philippinarum (Asari Clams). Pathogens. 2020; 9(8):669. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9080669

Chicago/Turabian StyleYanagimoto, Keita, Kosei Uematsu, Takaya Yamagami, and Eiji Haramoto. 2020. "The Circulation of Type F Clostridium perfringens among Humans, Sewage, and Ruditapes philippinarum (Asari Clams)" Pathogens 9, no. 8: 669. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9080669

APA StyleYanagimoto, K., Uematsu, K., Yamagami, T., & Haramoto, E. (2020). The Circulation of Type F Clostridium perfringens among Humans, Sewage, and Ruditapes philippinarum (Asari Clams). Pathogens, 9(8), 669. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9080669