Pleiotropic Functions of Nitric Oxide Produced by Ascorbate for the Prevention and Mitigation of COVID-19: A Revaluation of Pauling’s Vitamin C Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. NO Therapy for COVID-19 Patients

3. Antiviral Activity of NO

3.1. Smokers’ Paradox

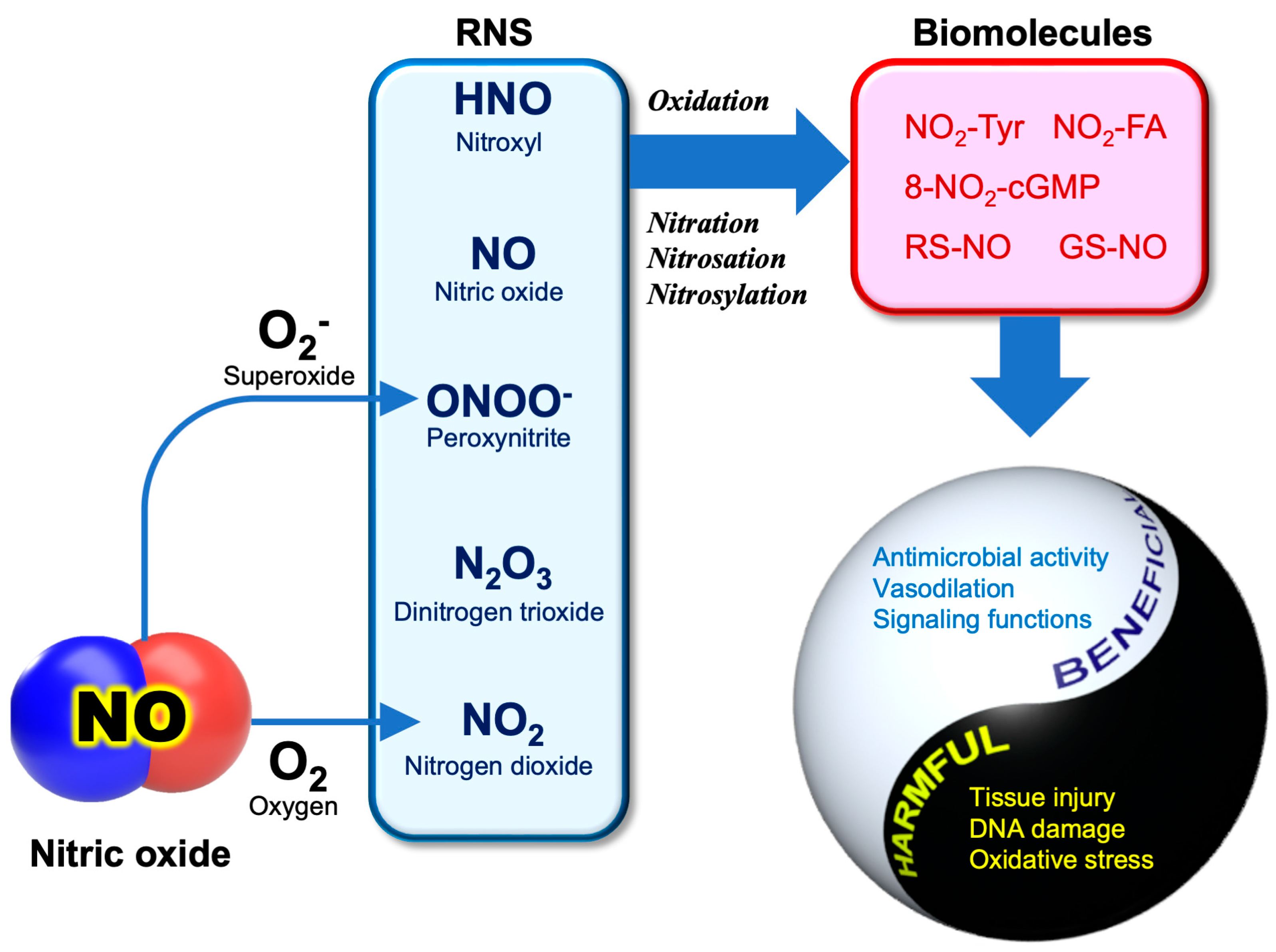

3.2. RNS Biochemistry

3.3. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Activity of NO

4. Diversity of NO Generating Mechanisms

4.1. Oxidative and Reductive Mechanisms for NO Generation

4.2. Nitrite as a Degradation Product of NO

4.3. Nitrite as a Precursor of NO

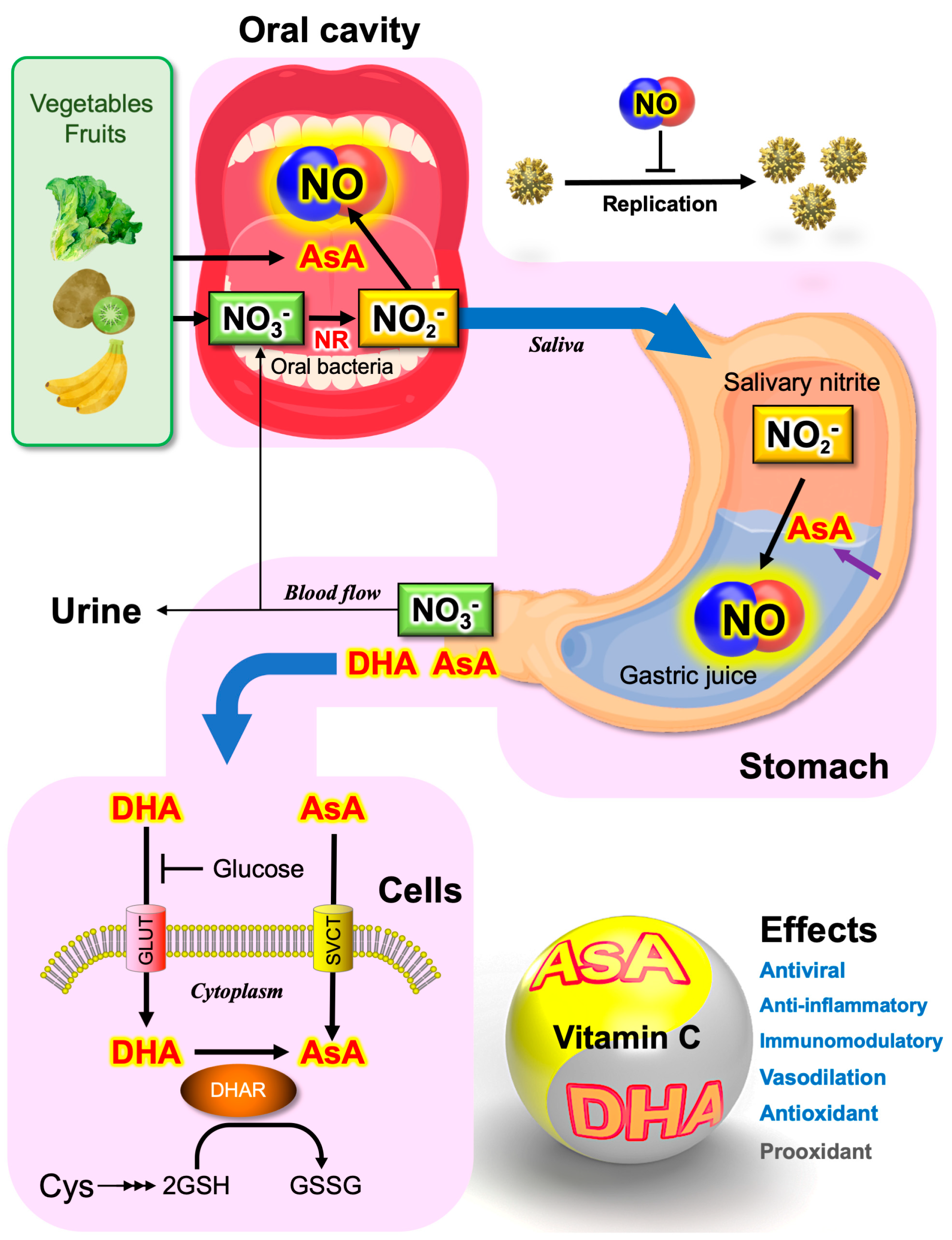

4.4. Saliva as the Major Source of Nitrite

5. Ascorbate-Dependent NO Production

5.1. Antibacterial Activity of Vitamin C

5.2. Ascorbate Secreted from the Stomach

5.3. Plants as the Major Dietary Source of Nitrate and Vitamin C

5.4. Vitamin P and NO

6. Possible Roles of Nitrate, Nitrite, and Vitamin C in the Prevention of COVID-19

6.1. Toxicity of Nitrite and Nitrate

6.2. Prevention of SARS-CoV-2 Transmission

7. Vitamin C Therapy in COVID-19

7.1. Free Radical Storm

7.2. High-Dose Intravenous Vitamin C Treatment

8. Updating Pauling’s Vitamin C Therapy

8.1. Long-Lasting Debates on the Pharmacological Effects of Vitamin C

8.2. High Dose Necessary for Pleotropic Function of Vitamin C

8.3. Updating Pauling’s Concept

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Devaux, C.A.; Rolain, J.M.; Raoult, D. ACE2 receptor polymorphism: Susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2, hypertension, multi-organ failure, and COVID-19 disease outcome. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, 53, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Yang, J.W.; Lee, K.H.; Effenberger, M.; Szpirt, W.; Kronbichler, A.; Shin, J.I. Immunopathogenesis and treatment of cytokine storm in COVID-19. Theranostics 2021, 11, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, G.D.; Ji, C.; Connolly, B.A.; Couper, K.; Lall, R.; Baillie, J.K.; Bradley, J.M.; Dark, P.; Dave, C.; De Soyza, A.; et al. Effect of noninvasive respiratory dtrategies on intubation or mortality among patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and COVID-19: The RECOVERY-RS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2022, 327, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginestra, J.C.; Mitchell, O.J.L.; Anesi, G.L.; Christie, J.D. COVID-19 critical illness: A data-driven review. Annu. Rev. Med. 2022, 73, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamenshchikov, N.O.; Berra, L.; Carroll, R.W. Therapeutic effects of inhaled nitric oxide therapy in COVID-19 patients. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, R.; Combes, A.; Lo Coco, V.; De Piero, M.E.; Belohlavek, J.; Euro, E.C.-W.; Euro, E.S.C. ECMO for COVID-19 patients in Europe and Israel. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhou, J.; Dong, Y.; Jiang, W.; Jiang, W. Rampant C-to-U deamination accounts for the intrinsically high mutation rate in SARS-CoV-2 spike gene. RNA 2022, 28, 917–926. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, K.; Tzou, P.L.; Nouhin, J.; Gupta, R.K.; de Oliveira, T.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L.; Fera, D.; Shafer, R.W. The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2021, 22, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otaki, J.M.; Nakasone, W.; Nakamura, M. Nonself mutations in the spike protein suggest an increase in the antigenicity and a decrease in the virulence of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. COVID 2022, 2, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigel, J.H.; Tomashek, K.M.; Dodd, L.E.; Mehta, A.K.; Zingman, B.S.; Kalil, A.C.; Hohmann, E.; Chu, H.Y.; Luetkemeyer, A.; Kline, S.; et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of COVID-19—Final report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1813–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cully, M. A tale of two antiviral targets—And the COVID-19 drugs that bind them. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal, A.J.; Gomes da Silva, M.M.; Musungaie, D.B.; Kovalchuk, E.; Gonzalez, A.; Delos Reyes, V.; Martin-Quiros, A.; Caraco, Y.; Williams-Diaz, A.; Brown, M.L.; et al. Molnupiravir for oral treatment of COVID-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krammer, F. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development. Nature 2020, 586, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otaki, J.M.; Nakasone, W.; Nakamura, M. Self and nonself short constituent sequences of amino acids in the SARS-CoV-2 proteome for vaccine development. COVID 2021, 1, 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, R.C.; Horby, P.; Lim, W.S.; Emberson, J.R.; Mafham, M.; Bell, J.L.; Linsell, L.; Staplin, N.; Brightling, C.; Ustianowski, A.; et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19—Preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.Z. Can early and high intravenous dose of vitamin C prevent and treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Med. Drug Disc. 2020, 5, 100028. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmik, K.K.; Barek, M.A.; Aziz, M.A.; Islam, M.S. Impact of high-dose vitamin C on the mortality, severity, and duration of hospital stay in COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olczak-Pruc, M.; Swieczkowski, D.; Ladny, J.R.; Pruc, M.; Juarez-Vela, R.; Rafique, Z.; Peacock, F.W.; Szarpak, L. Vitamin C supplementation for the treatment of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boretti, A.; Banik, B.K. Intravenous vitamin C for reduction of cytokines storm in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Pharmanutrition 2020, 12, 100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiouris, M.G.; L’Heureux, M.; Cable, C.A.; Fisher, B.J.; Leichtle, S.W.; Fowler, A.A. The emerging role of vitamin C as a treatment for sepsis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, J.S.; Aldhahir, A.M.; Al Ghamdi, S.S.; AlBahrani, S.; AlDraiwiesh, I.A.; Alqarni, A.A.; Latief, K.; Raya, R.P.; Oyelade, T. Inhaled nitric oxide for clinical management of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichinose, F.; Roberts, J.D., Jr.; Zapol, W.M. Inhaled nitric oxide: A selective pulmonary vasodilator: Current uses and therapeutic potential. Circulation 2004, 109, 3106–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steudel, W.; Hurford, W.E.; Zapol, W.M. Inhaled nitric oxide: Basic biology and clinical applications. Anesthesiology 1999, 91, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignarro, L.J. Inhaled nitric oxide and COVID-19. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 3848–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortenberry, J.D. Inhaled nitric oxide for pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: Another brick in the wall? Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 1879–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.D.; Fineman, J.R.; Morin, F.C.; Shaul, P.W.; Rimar, S.; Schreiber, M.D.; Polin, R.A.; Zwass, M.S.; Zayek, M.M.; Gross, I.; et al. Inhaled nitric oxide and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 336, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.N.; Liu, P.; Gao, H.; Sun, B.; Chao, D.S.; Wang, F.; Zhu, Y.J.; Hedenstierna, R.; Wang, C.G. Inhalation of nitric oxide in the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome: A rescue trial in Beijing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 39, 1531–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, J.; Ko, Y.F.; Young, J.D.; Ojcius, D.M. Could nasal nitric oxide help to mitigate the severity of COVID-19? Microbes Infect. 2020, 22, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valsecchi, C.; Winterton, D.; Safaee Fakhr, B.; Collier, A.Y.; Nozari, A.; Ortoleva, J.; Mukerji, S.; Gibson, L.E.; Carroll, R.W.; Shaefi, S.; et al. High-dose inhaled nitric oxide for the treatment of spontaneously breathing pregnant patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 140, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sulaiman, K.; Korayem, G.B.; Altebainawi, A.F.; Al Harbi, S.; Alissa, A.; Alharthi, A.; Kensara, R.; Alfahed, A.; Vishwakarma, R.; Al Haji, H.; et al. Evaluation of inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) treatment for moderate-to-severe ARDS in critically ill patients with COVID-19: A multicenter cohort study. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shei, R.J.; Baranauskas, M.N. More questions than answers for the use of inhaled nitric oxide in COVID-19. Nitric Oxide 2022, 124, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagate, F.; Tuffet, S.; Masi, P.; Perier, F.; Razazi, K.; de Prost, N.; Carteaux, G.; Payen, D.; Mekontso Dessap, A. Rescue therapy with inhaled nitric oxide and almitrine in COVID-19 patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann. Intensive Care 2020, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric oxide synthases: Regulation and function. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorentino, G.; Coppola, A.; Izzo, R.; Annunziata, A.; Bernardo, M.; Lombardi, A.; Trimarco, V.; Santulli, G.; Trimarco, B. Effects of adding l-arginine orally to standard therapy in patients with COVID-19: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. Results of the first interim analysis. Eclinicalmedicine 2021, 40, 101125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebayo, A.; Varzideh, F.; Wilson, S.; Gambardella, J.; Eacobacci, M.; Jankauskas, S.S.; Donkor, K.; Kansakar, U.; Trimarco, V.; Mone, P.; et al. L-Arginine and COVID-19: An update. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, S.; McNicholas, B.; Rezoagli, E.; Pham, T.; Curley, G.; McAuley, D.; O’Kane, C.; Nichol, A.; Dos Santos, C.; Rocco, P.R.M.; et al. Emerging pharmacological therapies for ARDS: COVID-19 and beyond. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 2265–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daxon, B.T.; Lark, E.; Matzek, L.J.; Fields, A.R.; Haselton, K.J. Nebulized nitroglycerin for coronavirus disease 2019-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: A case report. A A Pract. 2021, 15, e01376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyaerts, E.; Vijgen, L.; Chen, L.; Maes, P.; Hedenstierna, G.; Van Ranst, M. Inhibition of SARS-coronavirus infection in vitro by S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine, a nitric oxide donor compound. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2004, 8, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G.R.; Anderson, R.A.; Chirkov, Y.Y.; Morris-Thurgood, J.; Jackson, S.K.; Lewis, M.J.; Horowitz, J.D.; Frenneaux, M.P. Acute effects of vitamin c on platelet responsiveness to nitric oxide donors and endothelial function in patients with chronic heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Pharm. 2001, 37, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sehemi, A.G.; Pannipara, M.; Parulekar, R.S.; Patil, O.; Choudhari, P.B.; Bhatia, M.S.; Zubaidha, P.K.; Tamboli, Y. Potential of NO donor furoxan as SARS-CoV-2 main protease (M(pro)) inhibitors: In silico analysis. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 5804–5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrett, N.K.; Bell, A.S.; Brown, D.; Ellis, P. Sildenafil (VIAGRA(TM)), a potent and selective inhibitor of type 5 cGMP phosphodiesterase with utility for the treatment of male erectile dysfunction. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1996, 6, 1819–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.E.; Ohlsson, A.; Shah, P.S. Sildenafil for pulmonary hypertension in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 8, CD005494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mario, L.; Roberto, M.; Marta, L.; Teresa, C.M.; Laura, M. Hypothesis of COVID-19 therapy with sildenafil. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamarina, M.G.; Beddings, I.; Lomakin, F.M.; Boisier Riscal, D.; Gutierrez Claveria, M.; Vidal Marambio, J.; Retamal Baez, N.; Pavez Novoa, C.; Reyes Allende, C.; Ferreira Perey, P.; et al. Sildenafil for treating patients with COVID-19 and perfusion mismatch: A pilot randomized trial. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadyen, C.; Garfield, B.; Mancio, J.; Ridge, C.A.; Semple, T.; Keeling, A.; Ledot, S.; Patel, B.; Samaranayake, C.B.; McCabe, C.; et al. Use of sildenafil in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonitis. Br. J. Anaesth. 2022, 129, e18–e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Dong, X.; Cao, Y.Y.; Yuan, Y.D.; Yang, Y.B.; Yan, Y.Q.; Akdis, C.A.; Gao, Y.D. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy 2020, 75, 1730–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, C.; Gani, F.; Berti, A.; Comberiati, P.; Peroni, D.; Cottini, M. Asthma and COVID-19: A dangerous liaison? Asthma Res. Pract. 2021, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunjaya, A.P.; Allida, S.M.; Di Tanna, G.L.; Jenkins, C. Asthma and risk of infection, hospitalization, ICU admission and mortality from COVID-19: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Asthma 2022, 59, 866–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais-Almeida, M.; Aguiar, R.; Martin, B.; Ansotegui, I.J.; Ebisawa, M.; Arruda, L.K.; Caminati, M.; Canonica, G.W.; Carr, T.; Chupp, G.; et al. COVID-19, asthma, and biologic therapies: What we need to know. World Allergy Organ. J. 2020, 13, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrini, A.; Taylor, D.R.; Thomas, P.S.; Yates, D.H. Fractional exhaled nitric oxide in asthma: An update. Respirology 2010, 15, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsalinos, K.; Barbouni, A.; Poulas, K.; Polosa, R.; Caponnetto, P.; Niaura, R. Current smoking, former smoking, and adverse outcome among hospitalized COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2020, 11, 2040622320935765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyara, M.; Tubach, F.; Pourcher, V.; Morelot-Panzini, C.; Pernet, J.; Haroche, J.; Lebbah, S.; Morawiec, E.; Gorochov, G.; Caumes, E.; et al. Low rate of daily active tobacco smoking in patients with symptomatic COVID-19. Qeios 2020, WPP19W.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.S.; Siddiqi, T.J.; Khan, M.S.; Patel, U.K.; Shahid, I.; Ahmed, J.; Kalra, A.; Michos, E.D. Is there a smoker’s paradox in COVID-19? BMJ Evidence-Based Med. 2021, 26, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedenstierna, G.; Chen, L.; Hedenstierna, M.; Lieberman, R.; Fine, D.H. Nitric oxide dosed in short bursts at high concentrations may protect against COVID 19. Nitric Oxide 2020, 103, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaike, T.; Maeda, H. Nitric oxide and virus infection. Immunology 2000, 101, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGroote, M.A.; Fang, F.C. Antimicrobial properties of nitric oxide. In Nitric Oxide and Infection; Fang, F.C., Ed.; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 231–261. [Google Scholar]

- Cortese-Krott, M.M.; Koning, A.; Kuhnle, G.G.C.; Nagy, P.; Bianco, C.L.; Pasch, A.; Wink, D.A.; Fukuto, J.M.; Jackson, A.A.; van Goor, H.; et al. The reactive rpecies Iinteractome: Evolutionary emergence, biological significance, and opportunities for redox metabolomics and personalized medicine. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 27, 684–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.P.; McAndrew, J.; Sellak, H.; White, C.R.; Jo, H.; Freeman, B.A.; Darley-Usmar, V.M. Biological aspects of reactive nitrogen species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1411, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, T.C.; Kathpalia, P.; Gorla, S.; Wadhwa, S. Localization of nitro-tyrosine immunoreactivity in human retina. Ann. Anat. 2019, 223, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, T.; Okamoto, S.; Sawa, T.; Yoshitake, J.; Tamura, F.; Ichimori, K.; Miyazaki, K.; Sasamoto, K.; Maeda, H. 8-nitroguanosine formation in viral pneumonia and its implication for pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacorta, L.; Gao, Z.; Schopfer, F.J.; Freeman, B.A.; Chen, Y.E. Nitro-fatty acids in cardiovascular regulation and diseases: Characteristics and molecular mechanisms. Front. Biosci. 2016, 21, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakihama, Y.; Tamaki, R.; Shimoji, H.; Ichiba, T.; Fukushi, Y.; Tahara, S.; Yamasaki, H. Enzymatic nitration of phytophenolics: Evidence for peroxynitrite-independent nitration of plant secondary metabolites. FEBS Lett. 2003, 553, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuto, J.M.; Perez-Ternero, C.; Zarenkiewicz, J.; Lin, J.; Hobbs, A.J.; Toscano, J.P. Hydropersulfides (RSSH) and nitric oxide (NO) signaling: Possible effects on S-nitrosothiols (RS-NO). Antioxidants 2022, 11, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedon, P.C.; Tannenbaum, S.R. Reactive nitrogen species in the chemical biology of inflammation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004, 423, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, H. Nitrite-dependent nitric oxide production pathway: Implications for involvement of active nitrogen species in photoinhibition in vivo. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2000, 355, 1477–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, N.; Ayajiki, K.; Okamura, T. Control of systemic and pulmonary blood pressure by nitric oxide formed through neuronal nitric oxide synthase. J. Hypertens. 2009, 27, 1929–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, C. Multiple pathways of peroxynitrite cytotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 2003, 140-141, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, A.G.; Ibargoyen, M.N.; Mastrogiovanni, M.; Radi, R.; Keszenman, D.J.; Peluffo, R.D. Fast and biphasic 8-nitroguanine production from guanine and peroxynitrite. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 193, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, T.; Fujii, S.; Kato, A.; Yoshitake, J.; Miyamoto, Y.; Sawa, T.; Okamoto, S.; Suga, M.; Asakawa, M.; Nagai, Y.; et al. Viral mutation accelerated by nitric oxide production during infectionin vivo. FASEB J. 2000, 14, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oza, P.P.; Kashfi, K. Utility of NO and H2S donating platforms in managing COVID-19: Rationale and promise. Nitric Oxide 2022, 128, 72–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingstrom, J.; Akerstrom, S.; Hardestam, J.; Stoltz, M.; Simon, M.; Falk, K.I.; Mirazimi, A.; Rottenberg, M.; Lundkvist, A. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite have different antiviral effects against hantavirus replication and free mature virions. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006, 36, 2649–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, M.; Zaragoza, C.; McMillan, A.; Quick, R.A.; Hohenadl, C.; Lowenstein, J.M.; Lowenstein, C.J. An antiviral mechanism of nitric oxide: Inhibition of a viral protease. Immunity 1999, 10, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colasanti, M.; Persichini, T.; Venturini, G.; Ascenzi, P. S-nitrosylation of viral proteins: Molecular bases for antiviral effect of nitric oxide. IUBMB Life 1999, 48, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerstrom, S.; Mousavi-Jazi, M.; Klingstrom, J.; Leijon, M.; Lundkvist, A.; Mirazimi, A. Nitric oxide inhibits the replication cycle of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 1966–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaberi, D.; Krambrich, J.; Ling, J.; Luni, C.; Hedenstierna, G.; Jarhult, J.D.; Lennerstrand, J.; Lundkvist, A. Mitigation of the replication of SARS-CoV-2 by nitric oxide in vitro. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guns, J.; Vanherle, S.; Hendriks, J.J.A.; Bogie, J.F.J. Protein lipidation by palmitate controls macrophage function. Cells 2022, 11, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akerstrom, S.; Gunalan, V.; Keng, C.T.; Tan, Y.J.; Mirazimi, A. Dual effect of nitric oxide on SARS-CoV replication: Viral RNA production and palmitoylation of the S protein are affected. Virology 2009, 395, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.A.; Saier, M.H., Jr. The SARS-coronavirus infection cycle: A survey of viral membraneproteins, their functional interactions and pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhang, L. Palmitoylation of SARS-CoV-2 S protein is critical for S-mediated syncytia formation and virus entry. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, A.; Fuller, W. Protein S-palmitoylation: Advances and challenges in studying a therapeutically important lipid modification. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 861–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, D.E.; Jang, G.M.; Bouhaddou, M.; Xu, J.; Obernier, K.; White, K.M.; O’Meara, M.J.; Rezelj, V.V.; Guo, J.Z.; Swaney, D.L. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature 2020, 583, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Hernando, C.; Fukata, M.; Bernatchez, P.N.; Fukata, Y.; Lin, M.I.; Bredt, D.S.; Sessa, W.C. Identification of Golgi-localized acyl transferases that palmitoylate and regulate endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 174, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yuan, H.; Li, X.; Wang, H. Spike protein mediated membrane fusion during SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 95, e28212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, D.; Schwarz, G. Nitrite-dependent nitric oxide synthesis by molybdenum enzymes. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 2126–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, M.T.; Raat, N.J.; Shiva, S.; Dezfulian, C.; Hogg, N.; Kim-Shapiro, D.B.; Patel, R.P. Nitrite as a vascular endocrine nitric oxide reservoir that contributes to hypoxic signaling, cytoprotection, and vasodilation. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2006, 291, H2026–H2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O. Novel aspects of dietary nitrate and human health. Annu. Rev. Nutrit. 2013, 33, 129–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Carlström, M.; Weitzberg, E. Metabolic effects of dietary nitrate in health and disease. Cell Metab. 2018, 28, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, J.O.; Weitzberg, E.; Gladwin, M.T. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, N.S.; Calvert, J.W.; Gundewar, S.; Lefer, D.J. Dietary nitrite restores NO homeostasis and is cardioprotective in endothelial nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamasaki, H.; Watanabe, N.S.; Fukuto, J.; Cohen, M.F. Nitrite-dependent nitric oxide production pathway: Diversity of NO production systems. In Studies on Pediatric Disorders; Tsukahara, H., Kaneko, K., Eds.; Oxidative Stress in Applied Basic Research and Clinical Practice; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki, H. The NO world for plants: Achieving balance in an open system. Plant Cell Environ. 2005, 28, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMartino, A.W.; Kim-Shapiro, D.B.; Patel, R.P.; Gladwin, M.T. Nitrite and nitrate chemical biology and signalling. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.L.; Huang, Z.H.; Mashimo, H.; Bloch, K.D.; Moskowitz, M.A.; Bevan, J.A.; Fishman, M.C. Hypertension in mice lacking the gene for endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nature 1995, 377, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinert, H.; Art, J.; Pautz, A. Regulation of the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase. In Nitric Oxide; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 211–267. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, X.; Broderick, M.; Fein, H. Measurement of nitric oxide production in biological systems by using Griess reaction assay. Sensors 2003, 3, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuehr, D.J.; Marletta, M.A. Mammalian nitrate biosynthesis: Mouse macrophages produce nitrite and nitrate in response to Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1985, 82, 7738–7742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, H.; Watanabe, N.S.; Sakihama, Y.; Cohen, M.F. An overview of methods in plant nitric oxide (NO) research: Why do we always need to use multiple methods? In Plant Nitric Oxide: Methods and Protocols; Gupta, K.J., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer Science+Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 1424, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, G.; Smith, L.; Drummond, R.; Duncan, C.; Golden, M.; Benjamin, N. Chemical synthesis of nitric oxide in the stomach from dietary nitrate in humans. Gut 1997, 40, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, N.; O’Driscoll, F.; Dougall, H.; Duncan, C.; Smith, L.; Golden, M.; McKenzie, H. Stomach NO synthesis. Nature 1994, 368, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, H.H.; Shonle, H.A.; Grindley, H.S. The origin of the ntirate in the urine. J. Biol. Chem. 1916, 24, 461–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannala, A.S.; Mani, A.R.; Spencer, J.P.; Skinner, V.; Bruckdorfer, K.R.; Moore, K.P.; Rice-Evans, C.A. The effect of dietary nitrate on salivary, plasma, and urinary nitrate metabolism in humans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 34, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, C.; Dougall, H.; Johnston, P.; Green, S.; Brogan, R.; Leifert, C.; Smith, L.; Golden, M.; Benjamin, N. Chemical generation of nitric oxide in the mouth from the enterosalivary circulation of dietary nitrate. Nat. Med. 1995, 1, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Liu, X.; Sun, Q.; Fan, Z.; Xia, D.; Ding, G.; Ong, H.L.; Adams, D.; Gahl, W.A.; Zheng, C.; et al. Sialin (SLC17A5) functions as a nitrate transporter in the plasma membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 13434–13439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaba, Y.; Khan, A.; Galal, M.; Lakshmanadoss, L.; Bolkini, M. Infantile free sialic acid storage disease presenting as non-immune hydrops fetalis. J. Pediat. Neon. Individ. Med. 2019, 8, e080114. [Google Scholar]

- Huizing, M.; Hackbarth, M.E.; Adams, D.R.; Wasserstein, M.; Patterson, M.C.; Walkley, S.U.; Gahl, W.A.; Consortium, F. Free sialic acid storage disorder: Progress and promise. Neurosci. Lett. 2021, 755, 135896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatelli, P.; Fabietti, G.; Ricci, A.; Piattelli, A.; Curia, M.C. How periodontal disease and presence of nitric oxide reducing oral bacteria can affect blood pressure. Int. J Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, P.N.; Deshmukh, R. Oral microbiome: Unveiling the fundamentals. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2019, 23, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Hu, L.; Feng, X.; Wang, S. Nitrate and nitrite in health and disease. Aging Dis. 2018, 9, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.; Alving, K. Intragastric nitric oxide production in humans: Measurements in expelled air. Gut 1994, 35, 1543–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Brust, G.J.; Fernandez, A.R.; Villanueva-Ruiz, G.J.; Velasco, R.; Trujillo-Hernandez, B.; Vasquez, C. Daily intake of 100 mg ascorbic acid as urinary tract infection prophylactic agent during pregnancy. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2007, 86, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenech, M.; Amaya, I.; Valpuesta, V.; Botella, M.A. Vitamin C content in fruits: Biosynthesis and regulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J. Nonenzymatic nitric oxide production in humans. Nitric Oxide 1998, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakihama, Y.; Mano, J.; Sano, S.; Asada, K.; Yamasaki, H. Reduction of phenoxyl radicals mediated by monodehydroascorbate reductase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 279, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, S.; Wiklund, N.P.; Engstrand, L.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O. Effects of pH, nitrite, and ascorbic acid on nonenzymatic nitric oxide generation and bacterial growth in urine. Nitric Oxide 2001, 5, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathbone, B.; Johnson, A.; Wyatt, J.I.; Kelleher, J.; Heatley, R.; Losowsky, M. Ascorbic acid: A factor concentrated in human gastric juice. Clin. Sci. 1989, 76, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, A.; Drake, I.; Schorah, C.; White, K.; Lynch, D.; Axon, A.; Dixon, M. Ascorbic acid and total vitamin C concentrations in plasma, gastric juice, and gastrointestinal mucosa: Effects of gastritis and oral supplementation. Gut 1996, 38, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobala, G.M.; Schorah, C.J.; Sanderson, M.; Dixon, M.F.; Tompkins, D.S.; Godwin, P.; Axon, A.T. Ascorbic acid in the human stomach. Gastroenterology 1989, 97, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, B.G.; Yan, Y.H.; Ge, Z.L.; Ou, G.W.; Zhao, K. Ascorbic acid secretion in the human stomach and the effect of gastrin. World J. Gastroenterol. 2000, 6, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadoran, Z.; Mirmiran, P.; Kashfi, K.; Ghasemi, A. Lost-in-translation of metabolic effects of inorganic nitrate in type 2 diabetes: Is ascorbic acid the answer? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, R.; Leigh, R. Nitrate accumulation by wheat (Triticum aestivum) in relation to growth and tissue N concentrations. Plant Soil 1990, 124, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colla, G.; Kim, H.-J.; Kyriacou, M.C.; Rouphael, Y. Nitrate in fruits and vegetables. Sci. Hortic-Amst. 2018, 237, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.; Arcot, J.; Alice Lee, N. Nitrate and nitrite quantification from cured meat and vegetables and their estimated dietary intake in Australians. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassimotto, N.M.A.; Genovese, M.I.; Lajolo, F.M. Antioxidant activity of dietary fruits, vegetables, and commercial frozen fruit pulps. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2928–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N.; Yamasaki, H. Dynamics of nitrite content in fresh spinach leaves: Evidence for nitrite formation caused by microbial nitrate reductase activity. J. Nutrit. Food Sci. 2017, 7, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.F.; Mazzola, M.; Yamasaki, H. Nitric oxide research in agriculture. In Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants; Rai, K., Takabe, T., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M.F.; Lamattina, L.; Yamasaki, H. Nitric oxide signaling by plant-associated bacteria. In Nitric Oxide in Plant Physiology; Hyat, S., Miri, M., Pichel, J., Ahmad, A., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2010; pp. 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki, H.; Cohen, M.F. Biological consilience of hydrogen sulfide and nitric oxide in plants: Gases of primordial earth linking plant, microbial and animal physiologies. Nitric Oxide 2016, 55, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakihama, Y.; Cohen, M.F.; Grace, S.C.; Yamasaki, H. Plant phenolic antioxidant and prooxidant activities: Phenolics-induced oxidative damage mediated by metals in plants. Toxicology 2002, 177, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, H.; Sakihama, Y.; Takahashi, S. An alternative pathway for nitric oxide production in plants: New features of an old enzyme. Trend. Plant Sci. 1999, 4, 128–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, H.; Cohen, M.F. NO signal at the crossroads: Polyamine-induced nitric oxide synthesis in plants? Trend. Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 522–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L. Orthomolecular psychiatry. Science 1968, 160, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asada, K. The water-water cycle in chloroplasts: Scavenging of active oxygens and dissipation of excess photons. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999, 50, 601–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badejo, A.A.; Wada, K.; Gao, Y.; Maruta, T.; Sawa, Y.; Shigeoka, S.; Ishikawa, T. Translocation and the alternative D-galacturonate pathway contribute to increasing the ascorbate level in ripening tomato fruits together with the D-mannose/L-galactose pathway. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Halliwell, B. The presence of glutathione and glutathione reductase in chloroplasts: A proposed role in ascorbic acid metabolism. Planta 1976, 133, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asada, K. Production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species in chloroplasts and their functions. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Tamashiro, A.; Sakihama, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kawamitsu, Y.; Yamasaki, H. High-susceptibility of photosynthesis to photoinhibition in the tropical plant Ficus microcarpa L. f. cv. Golden Leaves. BMC Plant Biol. 2002, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roychoudhury, A.; Basu, S. Ascorbate-glutathione and plant tolerance to various abiotic stresses. In Oxidative Stress in Plants: Causes, Consequences and Tolerance; Umar, S., Naser, A.A., Eds.; IK International Publishers: New Delhi, India, 2012; pp. 177–258. [Google Scholar]

- Rusznyak, S.; Szent-Györgyi, A. Vitamin P: Flavonols as vitamins. Nature 1936, 138, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakihama, Y.; Yamasaki, H. Phytochemical antioxidants: Past, present and future. In Antioxidants; Waisundara, V., Ed.; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nijveldt, R.J.; Van Nood, E.; Van Hoorn, D.E.; Boelens, P.G.; Van Norren, K.; Van Leeuwen, P.A. Flavonoids: A review of probable mechanisms of action and potential applications. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondonno, C.P.; Croft, K.D.; Ward, N.; Considine, M.J.; Hodgson, J.M. Dietary flavonoids and nitrate: Effects on nitric oxide and vascular function. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 216–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, S.; Lopez, D.; Saiz, M.; Buxaderas, S.; Sanchez, J.; Puig-Parellada, P.; Mitjavila, M. A flavonoid-rich diet increases nitric oxide production in rat aorta. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 135, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, H. A function of colour. Trend. Plant Sci. 1997, 2, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, H.; Uefuji, H.; Sakihama, Y. Bleaching of the red anthocyanin induced by superoxide radical. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996, 332, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gago, B.; Lundberg, J.O.; Barbosa, R.M.; Laranjinha, J. Red wine-dependent reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide in the stomach. Free Radic. Bio. Med. 2007, 43, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, B.S.; Gago, B.; Barbosa, R.M.; Laranjinha, J. Dietary polyphenols generate nitric oxide from nitrite in the stomach and induce smooth muscle relaxation. Toxicology 2009, 265, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, H.; Grace, S.C. EPR detection of phytophenoxyl radicals stabilized by zinc ions: Evidence for the redox coupling of plant phenolics with ascorbate in the H2O2 peroxidase system. FEBS Lett. 1998, 422, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morina, F.; Takahama, U.; Yamauchi, R.; Hirota, S.; Veljovic-Jovanovic, S. Quercetin 7-O-glucoside suppresses nitrite-induced formation of dinitrosocatechins and their quinones in catechin/nitrite systems under stomach simulating conditions. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, M.G. Betalains in some species of the Amaranthaceae family: A review. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Meng, X.; Zhu, M.; Li, Z. Research progress of betalain in response to adverse stresses and evolutionary relationship compared with anthocyanin. Molecules 2019, 24, 3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, R.; Cuenca, E.; Mate-Munoz, J.L.; Garcia-Fernandez, P.; Serra-Paya, N.; Estevan, M.C.; Herreros, P.V.; Garnacho-Castano, M.V. Effects of beetroot juice supplementation on cardiorespiratory endurance in athletes. a systematic review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemzer, B.; Pietrzkowski, Z.; Hunter, J.; Robinson, J.; Fink, B. Betalain-rich dietary supplement, but not PETN, increases vasodilation and nitric oxide: A comparative, single-dose, randomized, placebo-controlled, blinded, crossover pilot study. J. Food Res. 2020, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrens, C.; Feelisch, M. How to beet hypertension in pregnancy: Is there more to beetroot juice than nitrate? J. Physiol. 2020, 598, 3823–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comly, H.H. Cyanosis in infants caused by nitrates in well water. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1945, 129, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, E.H.; Loomba, J.J.; Monteith, S.J.; Crowley, R.W.; Medel, R.; Gress, D.R.; Kassell, N.F.; Dumont, A.S.; Sherman, C. Safety and pharmacokinetics of sodium nitrite in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: A phase IIa study. J. Neurosurg. 2013, 119, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Tao, W.; Flavell, R.A.; Zhu, S. Potential intestinal infection and faecal-oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vabret, N.; Britton, G.J.; Gruber, C.; Hegde, S.; Kim, J.; Kuksin, M.; Levantovsky, R.; Malle, L.; Moreira, A.; Park, M.D.; et al. Immunology of COVID-19: Current state of the science. Immunity 2020, 52, 910–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.S.; Hung, I.F.; Chan, P.P.; Lung, K.; Tso, E.; Liu, R.; Ng, Y.; Chu, M.Y.; Chung, T.W.; Tam, A.R. Gastrointestinal manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection and virus load in fecal samples from a Hong Kong cohort: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.H.; Poon, L.L.; Cheng, V.; Guan, Y.; Hung, I.; Kong, J.; Yam, L.Y.; Seto, W.H.; Yuen, K.Y.; Peiris, J.S.M. Detection of SARS coronavirus in patients with suspected SARS. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H. The SARS epidemic in Hong Kong. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2003, 57, 652–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, S.; Ruíz, A.; Pemán, J.; Salavert, M.; Domingo-Calap, P. Lack of evidence for infectious SARS-CoV-2 in feces and sewage. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 40, 2665–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancer, S.J.; Li, Y.; Hart, A.; Tang, J.W.; Jones, D.L. What is the risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 from the use of public toilets? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 792, 148341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corpe, C.P.; Eck, P.; Wang, J.; Al-Hasani, H.; Levine, M. Intestinal dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) transport mediated by the facilitative sugar transporters, GLUT2 and GLUT8. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 9092–9101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Ghosh, A.; Singh, A.K.; Misra, A. Clinical considerations for patients with diabetes in times of COVID-19 epidemic. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, W.L.; Mackowiak, P.A.; Barnett, C.C.; Marling-Cason, M.; Haley, M.L. The human gastric bactericidal barrier: Mechanisms of action, relative antibacterial activity, and dietary influences. J. Infect. Dis. 1989, 159, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopic, S.; Corradini, S.; Sidani, S.; Murek, M.; Vardanyan, A.; Föller, M.; Ritter, M.; Geibel, J.P. Ethanol inhibits gastric acid secretion in rats through increased AMP-kinase activity. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 25, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, G.; Carlsson, E.; Lindberg, P.; Wallmark, B. Gastric H, K-ATPase as therapeutic target. Annu. Rev. Pharm. Toxicol. 1988, 28, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopic, S.; Geibel, J.P. Update on the mechanisms of gastric acid secretion. Curr. Gastro. Rep. 2010, 12, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, C.; Zhao, G.; Chu, H.; Wang, D.; Yan, H.H.-N.; Poon, V.K.-M.; Wen, L.; Wong, B.H.-Y.; Zhao, X. Human intestinal tract serves as an alternative infection route for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, eaao4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevejo-Nunez, G.; Kolls, J.K.; De Wit, M. Alcohol use as a risk factor in infections and healing: A clinician’s perspective. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 2015, 37, 177. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X.-J.; Tan, L.; Ren, L.; Shao, Y.; Tao, W.; Wang, Y. COVID-19 risk appears to vary across different alcoholic beverages. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 772700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, G.P.; Erkenbrack, E.M.; Love, A.C. Stress-induced evolutionary innovation: A mechanism for the origin of cell types. Bioessays 2019, 41, e1800188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.Y.; Yip, A. Hans Selye (1907–1982): Founder of the stress theory. Singap. Med. J. 2018, 59, 170–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, T.; Noguchi, Y.; Ijiri, S.; Setoguchi, K.; Suga, M.; Zheng, Y.M.; Dietzschold, B.; Maeda, H. Pathogenesis of influenza virus-induced pneumonia: Involvement of both nitric oxide and oxygen radicals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 2448–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, T.; Akaike, T.; Hamamoto, T.; Suzuki, F.; Hirano, T.; Maeda, H. Oxygen radicals in influenza-induced pathogenesis and treatment with pyran polymer-conjugated SOD. Science 1989, 244, 974–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, L.A.; Belser, J.A.; Wadford, D.A.; Katz, J.M.; Tumpey, T.M. Inducible nitric oxide contributes to viral pathogenesis following highly pathogenic influenza virus infection in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 207, 1576–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Tackle the free radicals damage in COVID-19. Nitric Oxide 2020, 102, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, A.; Mohd Idris, R.A.; Ahmed, N.; Ahmad, S.; Murtadha, A.H.; Tengku Din, T.; Yean, C.Y.; Wan Abdul Rahman, W.F.; Mat Lazim, N.; Uskokovic, V.; et al. High-Dose Vitamin C for Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Diaz, D.F.; Lopez-Legarrea, P.; Quintero, P.; Martinez, J.A. Vitamin C in the treatment and/or prevention of obesity. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2014, 60, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padayatty, S.J.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Riordan, H.D.; Hewitt, S.M.; Katz, A.; Wesley, R.A.; Levine, M. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics: Implications for oral and intravenous use. Ann. Intern. Med. 2004, 140, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, A.; Grubaugh, N.D. Why does Japan have so few cases of COVID-19? EMBO Mol. Med. 2020, 12, e12481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H. Japanese strategy to COVID-19: How does it work? Glob. Health Med. 2020, 2, 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobko, T.; Marcus, C.; Govoni, M.; Kamiya, S. Dietary nitrate in Japanese traditional foods lowers diastolic blood pressure in healthy volunteers. Nitric Oxide 2010, 22, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundqvist, M.L.; Larsen, F.J.; Carlstrom, M.; Bottai, M.; Pernow, J.; Hellenius, M.L.; Weitzberg, E.; Lundberg, J.O. A randomized clinical trial of the effects of leafy green vegetables and inorganic nitrate on blood pressure. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 111, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente, L.; Gomez-Bernal, F.; Martin, M.M.; Navarro-Gonzalvez, J.A.; Argueso, M.; Perez, A.; Ramos-Gomez, L.; Sole-Violan, J.; Marcos, Y.R.J.A.; Ojeda, N.; et al. High serum nitrates levels in non-survivor COVID-19 patients. Med. Intensiv. 2020, 46, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svirbely, J.L.; Szent-Györgyi, A. The chemical nature of vitamin C. Biochem. J. 1932, 26, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, A.F. Diet, nutrition and infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 1932, 207, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, S.W. The influence of nutrition upon resistance to infection. Physiol. Rev. 1934, 14, 309–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, E.C. The vitamins and resistance to infection. Medicine 1934, 13, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L. The significance of the evidence about ascorbic acid and the common cold. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1971, 68, 2678–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L. Ascorbic acid and the common cold. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1971, 24, 1294–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L. Vitamin C and the Common Cold; Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Hemilä, H. Bias against vitamin C in mainstream medicine: Examples from trials of vitamin C for infections. Life 2022, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L. How to Live Longer and Feel Better; Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, G.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J. Drug-induced liver disturbance during the treatment of COVID-19. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 719308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortis, G.X.; Lenhart, G.; Becker, M.W.; Schwamback, K.H.; Tovo, C.V.; Blatt, C.R. Drug-induced liver injury and COVID-19: A review for clinical practice. World J. Hepatol. 2021, 13, 1143–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitrone, M.; Mele, F.; Durante-Mangoni, E.; Zampino, R. Drugs and liver injury: A not to be overlooked binomial in COVID-19. J. Chemother. 2022, 34, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, G.S.Z.; Gleeson, D.; Al-Joudeh, A.; Dube, A. Immune-mediated hepatitis with the Moderna vaccine, no longer a coincidence but confirmed. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 747–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traber, M.G.; Stevens, J.F. Vitamins C and E: Beneficial effects from a mechanistic perspective. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 1000–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Reddy, R.C.; Chadchan, K.S.; Patil, A.J.; Biradar, M.S.; Das, K.K. Nickel and oxidative stress: Cell signaling mechanisms and protective role of vitamin C. Endocr. Metab. Immune 2020, 20, 1024–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, J.M. How does ascorbic acid prevent endothelial dysfunction? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 1421–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dresen, E.; Lee, Z.-Y.; Hill, A.; Notz, Q.; Patel, J.J.; Stoppe, C. History of scurvy and use of vitamin C in critical illness: A narrative review. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2022, 2022, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L.; Itano, H.A.; Singer, S.J.; Wells, I.C. Sickle cell anemia, a molecular disease. Science 1949, 110, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, W.A. Hemoglobin S polymerization and sickle cell disease: A retrospective on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of Pauling’s Science paper. Am. J. Hematol. 2010, 95, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, A.S. Causation and disease: The Henle-Koch postulates revisited. Yale J. Biol. Med. 1976, 49, 175–195. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.; Mullarky, E.; Lu, C.; Bosch, K.N.; Kavalier, A.; Rivera, K.; Roper, J.; Chio, I.I.C.; Giannopoulou, E.G.; Rago, C. Vitamin C selectively kills KRAS and BRAF mutant colorectal cancer cells by targeting GAPDH. Science 2015, 350, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.C. Glutathione synthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013, 1830, 3143–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, F. The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism; Shambhala: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki, H. Nitric oxide research in plant biology: Its past and future. In Nitric Oxide Signaling in Higher Plants; Magalhaes, J.R., Singh, R.P., Passos, L.P., Eds.; Studium Press: Houston, TX, USA, 2004; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Filipovic, M.R.; Zivanovic, J.; Alvarez, B.; Banerjee, R. Chemical biology of H2S signaling through persulfidation. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1253–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, T.; Ida, T.; Wei, F.Y.; Nishida, M.; Kumagai, Y.; Alam, M.M.; Ihara, H.; Sawa, T.; Matsunaga, T.; Kasamatsu, S.; et al. Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase governs cysteine polysulfidation and mitochondrial bioenergetics. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, R.A. Concentrations of thiocyanate and hypothiocyanite in the saliva of young adults. J. Nihon Univ. Sch. Dent. 1994, 36, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegolon, L.; Mirandola, M.; Salaris, C.; Salvati, M.V.; Mastrangelo, G.; Salata, C. Hypothiocyanite and hypothiocyanite/lactoferrin mixture exhibit virucidal activity in vitro against SARS-CoV-2. Pathogens 2021, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruddell, W.; Blendis, L.; Walters, C. Nitrite and thiocyanate in the fasting and secreting stomach and in saliva. Gut 1977, 18, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Paonessa, J.D.; Zhang, Y.; Ambrosone, C.B.; McCann, S.E. Total isothiocyanate yield from raw cruciferous vegetables commonly consumed in the United States. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 1996–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorbo, L.D.; Michaelsen, V.S.; Ali, A.; Wang, A.; Ribeiro, R.V.P.; Cypel, M. High doses of inhaled nitric oxide as an innovative antimicrobial strategy for lung infections. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.J. COVID-19 accelerates endothelial dysfunction and nitric oxide deficiency. Microbes Infect. 2020, 22, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, M.; Sato, K.; Vellingiri, B.; Green, S.J.; Tanaka, M. Inverse association between hypertension treatment and COVID-19 prevalence in Japan. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 108, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, B.S.; Laranjinha, J. Nitrate from diet might fuel gut microbiota metabolism: Minding the gap between redox signaling and inter-kingdom communication. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 149, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.F.; Yamasaki, H.; Mazzola, M. Brassica napus seed meal soil amendment modifies microbial community structure, nitric oxide production and incidence of Rhizoctonia root rot. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2005, 37, 1215–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendrny, P.; Schulz, C.; Twele, F.; Meller, S.; von Kockritz-Blickwede, M.; Osterhaus, A.; Ebbers, J.; Pilchova, V.; Pink, I.; Welte, T.; et al. Scent dog identification of samples from COVID-19 patients—A pilot study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popov, T.A. Human exhaled breath analysis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011, 106, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamasaki, H.; Imai, H.; Tanaka, A.; Otaki, J.M. Pleiotropic Functions of Nitric Oxide Produced by Ascorbate for the Prevention and Mitigation of COVID-19: A Revaluation of Pauling’s Vitamin C Therapy. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11020397

Yamasaki H, Imai H, Tanaka A, Otaki JM. Pleiotropic Functions of Nitric Oxide Produced by Ascorbate for the Prevention and Mitigation of COVID-19: A Revaluation of Pauling’s Vitamin C Therapy. Microorganisms. 2023; 11(2):397. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11020397

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamasaki, Hideo, Hideyuki Imai, Atsuko Tanaka, and Joji M. Otaki. 2023. "Pleiotropic Functions of Nitric Oxide Produced by Ascorbate for the Prevention and Mitigation of COVID-19: A Revaluation of Pauling’s Vitamin C Therapy" Microorganisms 11, no. 2: 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11020397

APA StyleYamasaki, H., Imai, H., Tanaka, A., & Otaki, J. M. (2023). Pleiotropic Functions of Nitric Oxide Produced by Ascorbate for the Prevention and Mitigation of COVID-19: A Revaluation of Pauling’s Vitamin C Therapy. Microorganisms, 11(2), 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11020397