Viable and Heat-Resistant Microbiota with Probiotic Potential in Fermented and Non-Fermented Tea Leaves and Brews

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Bacterial Sampling of Tea Brew

2.3. Tea Brewing and Sampling

2.4. Heat Resistance Test

2.5. Bacterial Identification

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Viable Count

3.2. Heat Resistance Test

3.3. Sanger Sequencing

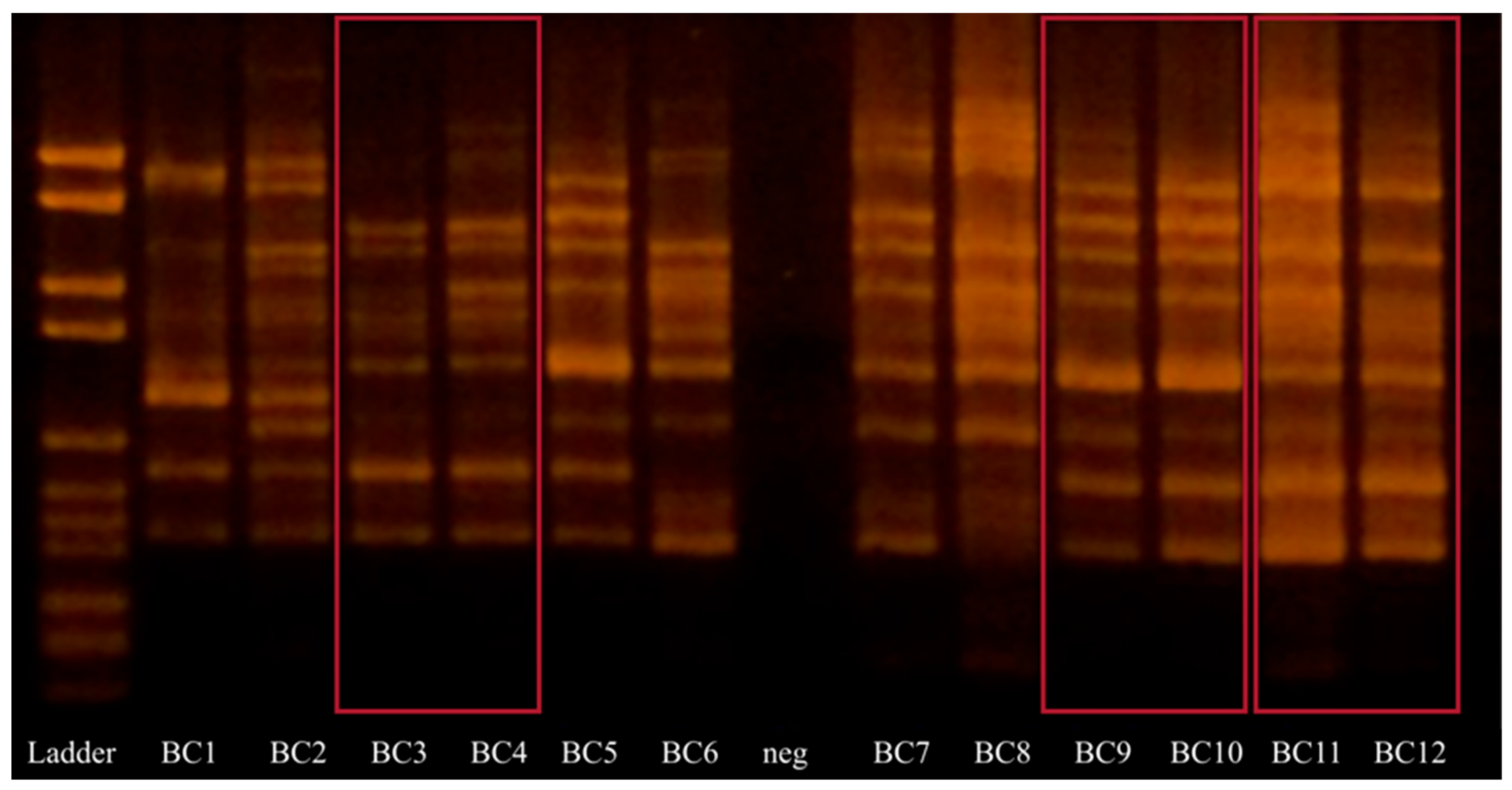

3.4. Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Macfarlane, A.; Macfarlarne, I. The Empire of Tea; The Overlook Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Liu, B.-L.; Chang, Y.-N. Bioactivities and sensory evaluation of Pu-erh teas made from three tea leaves in an improved pile fermentation process. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2010, 109, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, H.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Z. Microbial fermented tea—A potential source of natural food preservatives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, B.A.; Bealer, B.K. The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the Worlds Most Popular Drug; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Unachukwu, U.; Stepp, J.R.; Peters, C.M.; Long, C.; Kennelly, E. Pu-erh tea tasting in Yunnan, China: Correlation of drinkers’ perceptions to phytochemistry. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 132, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Lu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, S.; Wu, Y. Estimation of black tea quality by analysis of chemical composition and colour difference of tea infusions. Food Chem. 2003, 80, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T. Chinese Tea; China Intercontinental Press: Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, G.; Ye, M.; Wang, Y.; Ni, Y.; Su, M.; Huang, H.; Qiu, M.; Zhao, A.; Zheng, X.; Chen, T.; et al. Characterization of Pu-erh Tea Using Chemical and Metabolic Profiling Approaches. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 3046–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yang, G.; You, Q.; Sun, S.; Chen, R.; Lin, Z.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Lv, H. Updates on the chemistry, processing characteristics, and utilization of tea flavonoids in last two decades (2001–2021). Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 4757–4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.-W.; Cao, Z.-J.; Chen, H.-B.; Zhao, Z.-Z.; Zhu, L.; Yi, T. Oolong tea: A critical review of processing methods, chemical composition, health effects, and risk. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2957–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeva-Ilieva, M.; Stoeva, S.; Hvarchanova, N.; Georgiev, K.D. Green Tea: Current Knowledge and Issues. Foods 2025, 14, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lai, L.; You, Y.; Gao, R.; Xiang, J.; Wang, G.; Yu, W. Quantitative Analysis of Bioactive Compounds in Commercial Teas: Profiling Catechin Alkaloids, Phenolic Acids, and Flavonols Using Targeted Statistical Approaches. Foods 2023, 12, 3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; John, K.M.M.; Choi, J.N.; Lee, S.; Kim, A.J.; Kim, Y.M.; Lee, C.H. Changes in secondary metabolites of green tea during fermentation by Aspergillus oryzae and its effect on antioxidant potential. Food Res. Int. 2013, 53, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, D.-L.; Su, X.-Q.; Duan, S.-M.; Wan, J.-Q.; Yuan, W.-X.; Liu, B.-Y.; Ma, Y.; Pan, Y.-H. An Integrated Metagenomics/Metaproteomics Investigation of the Microbial Communities and Enzymes in Solid-state Fermentation of Pu-erh tea. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Lv, H.; Chen, F. Diversity and Variation of Bacterial Community Revealed by MiSeq Sequencing in Chinese Dark Teas. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Lin, H.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; Liu, Z. Study on the Trend in Microbial Changes during the Fermentation of Black Tea and Its Effect on the Quality. Foods 2023, 12, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlig, E.; Olsson, C.; He, J.; Stark, T.; Sadowska, Z.; Molin, G.; Ahrné, S.; Alsanius, B.; Håkansson, Å. Effects of household washing on bacterial load and removal of Escherichia coli from lettuce and “ready-to-eat” salads. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 5, 1215–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.R.; Wang, Q.; Fish, J.A.; Chai, B.; McGarell, D.M.; Sun, Y.; Brown, C.T.; Porras-Alfaro, A.; Cuske, C.R.; Tiedje, J.M. Ribosomal database project: Data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 42, D633–D642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quednau, M.; Ahrné, S.; Petersson, A.C.; Molin, G. Antibiotic-resistant strains of Enterococcus isolated from Swedish and Danish retailed chicken and pork. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1998, 84, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parte, A.C.; Sardà Carbasse, J.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Reimer, L.C.; Göker, M. List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 5607–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutková, J.; Kántor, A.; Terentjeva, M.; Petrová, J.; Puchalski, C.; Kluz, M.; Kordiaka, R.; Kunová, S.; Kačániová, M. Indicience of bacteria nad antibacterial activity of selected types of tea. Potravin. Slovak J. Food Sci. 2016, 10, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, M.; Reolon, É.; Santos, A.R.B.; Moreira, V.E.; Silva, I.F.; da Silva, N. Enterobacteriaceae in processed cocoa products. Rev. Inst. Adolfo Lutz 2011, 70, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.-Q.; Zhao, W.; Asano, N.; Yoda, Y.; Hara, Y.; Shimamura, T. Epigallocatechin Gallate Synergistically Enhances the Activity of Carbapenems against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 558–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L. Study on the main microbes of Yunnan puer tea during pile-fermentation process. J. Shangqiu Teach. Coll. 2005, 21, 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Tea and Herbal Infusions Europe (THIE). THIE’s Recommended Microbiological Specification for Tea (Camellia sinensis—Dry). 2021. Available online: https://thie-online.eu/publications.html (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Dayananda, K.R.T.L.K.; Fernando, K.M.E.P.; Perera, S. Assessment of Microbial Contaminations in Dried Tea And Tea Brew. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Invent. 2017, 6, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ash, C.; Collins, M.D. Comparative analysis of 23S ribosomal RNA gene sequences of Bacillus anthracis and emetic Bacillus cereus determined by PCR-direct sequencing. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992, 73, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, C.R.; Caugant, D.A.; Kolstø, A.B. Genotypic Diversity among Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis Strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 1719–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Li, Z.; Li, K.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Luo, X.; Zhang, T. Screening, Isolation, and Identification of Bacillus coagulans C2 in Pu’er Tea. In Advances in Applied Biotechnology: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Applied Biotechnology (ICAB 2014)-Volume II 2015, Tiajin, China, 28–30 November 2014; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 333, pp. 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Xiao, W.; Ma, Y.; Sun, T.; Yuan, W.; Tang, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H.; et al. Structure and dynamics of the bacterial communities in fermentation of the traditional Chinese post-fermented pu-erh tea revealed by 16S rRNA gene clone library. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 29, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Yu, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, Q.; Chen, W. Probiotic characteristics of Bacillus coagulans and associated implications for human health and diseases. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 64, 103643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuray Altun, G.; Erginkaya, Z. Potential Use of Bacillus coagulans in the Food Industry. Foods 2018, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Agency. Statement on the update of the list of QPS-recommended biological agentsintentionallyadded to food or feed as notifiedto EFSA 3: Suitability of taxonomix units notified to EFSA until September 2015. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4331. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. GRAS Notices; 2023. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/gras-notice-inventory/recently-published-gras-notices-and-fda-letters (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Keller, D.; Verbruggen, S.; Cash, H.; Farmer, D.; Venema, K. Spores of Bacillus coagulans GBI-30, 6086 show high germination, survival and enzyme activity in a dynamic, computer-controlled in vitro model of the gastrointestinal tract. Benef. Microbes. 2019, 10, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Aerobic Plate Count (Log CFU/g) | Lactobacilli Count (Log CFU/g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unbrewed Leaves | Tea Brew | Unbrewed Leaves | Tea Brew | |

| Pu-erh 1 | 5.7 (5.4–5.8) | 2.9 (2.8–3.0) ** | 5.6 (5.0–5.8) | 2.6 (2.2–2.7) ** |

| Pu-erh 2 | 5.4 (5.3–5.5) | 2.8 (2.6–3.0) ** | 5.1 (4.9–5.2) | 1.6 (1.6–1.8) ** |

| Pu-erh 3 | 7.0 (6.9–7.1) | 3.9 (3.6–4.0) ** | 6.4 (6.3–6.5) | 3.6 (3.5–3.7) ** |

| Pu-erh 4 | 5.3 (5.0–5.7) | 2.4 (2.3–2.6) ** | 5.3 (4.9–5.7) | 2.2 (1.9–2.6) ** |

| Pu-erh 5 | 6.0 (5.7–6.0) | 3.2 (2.8–3.4) ** | 5.9 (5.8–6.0) | 3.3 (2.8–3.2) ** |

| Pu-erh 6 | 4.7 (4.6–4.9) | 3.7 (3.5–3.9) ** | 4.9 (4.5–5.2) | 2.2 (1.0–3.6) ** |

| Liu Bao Cha | 3.8 (3.6–3.9) | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Tie Guan Yin 1 | 2.9 (2.7–3.0) | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Tie Guan Yin 2 | 3.6 (3.3–3.8) | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Jingzhi 1 | 2.9 (2.7–3.1) | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Jingzhi 2 | 3.5 (3.4–3.5) | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| Treatment | Water at 4 °C Control | Water at 70 °C |

|---|---|---|

| H. coagulans 1 | 7.1 | 2.5 |

| H. coagulans 2 | 7.1 | 2.7 |

| H. coagulans 3 | 6.7 | 2.7 |

| H. coagulans 4 | 7.0 | 1.5 |

| H. coagulans 5 | 7.0 | 2.6 |

| H. coagulans 6 | 6.8 | 3.8 |

| H. coagulans 7 | 6.9 | 2.6 |

| H. coagulans 8 | 7.1 | 2.1 |

| H. coagulans 9 | 7.0 | 2.2 |

| H. coagulans 10 | 7.0 | 2.3 |

| H. coagulans 11 | 7.2 | 1.5 |

| H. coagulans 12 | 7.0 | 2.9 |

| H. coagulans 13 | 7.1 | 2.6 |

| Unbrewed Leaves | Tea Brew | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) | Similarity (%) | Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) | Similarity (%) | |

| Pu-erh 1 | Paenibacillus cineris | 99.7 | Virgibacillus halophilus | 99.7 |

| Lederbergia ruris | 99.4 | Brevibacillus parabrevis | 100.0 | |

| Lederbergia galactosidilytica | 97.3 | Bacillus thermoamylovorans | 99.1 | |

| Pu-erh 2 | Paenibacillus barengoltzii | 100.0 | Robertmurraya siralis | 99.7 |

| Bacillus thermoamylovorans | 96.4 | Bacillus thermoamylovorans | 96.4 | |

| Paenibacillus barengoltzii | 100.0 | |||

| Pu-erh 3 | Sphingobacterium bambusae | 94.9 | Virgibacillus halophilus | 99.4 |

| Bacillus subtilis | 99.6 | Bacillus anthracis ** | 100.0 | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis * | 99.7 | Bacillus subtilis | 99.6 | |

| Pu-erh 4 | (Bacillus fortis) Brevibacillus fortis | 99.7 | Bacillus thermoamylovorans | 99.1 |

| Bacillus sporothermodurans | 99.1 | Bacillus ruris | 100.0 | |

| Bacillus subtilis | 99.7 | Heyndrickxia oleronia | 99.7 | |

| Micrococcus yunnanensis | 98.8 | |||

| Staphylococcus epidermidis * | 99.1 | |||

| Virgibacillus halophilus | 99.7 | |||

| Pu-erh 5 | Bacillus farraginis | 100.0 | Bacillus shackletonii | 99.5 |

| Micrococcus luteus | 99.1 | Bacillus anthracis | 100.0 | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis * | 99.7 | Bacillus sonorensis | 99.7 | |

| Pu-erh 6 | Pseudomonas fluorescens | 100.0 | Paenibacillus pueri | 99.5 |

| Staphylococcus warneri | 100.0 | Staphylococcus capitis | 100.0 | |

| Bacillus cereus * | 100.0 | Bacillus thermoamylovorans | 99.3 | |

| Bacillus subtilis | 100.0 | Paenibacillus barengoltzii | 100.0 | |

| Heyndrickxia oleronia | 99.5 | Virgibacillus halophilus | 99.2 | |

| Ornithinibacillus bavariensis | 100.0 | Bacillus ruris | 100.0 | |

| Heyndrickxia oleronia | 100.0 | |||

| Bacillus aquimaris | 99.9 | |||

| Bacillus shackletonii | 99.6 | |||

| Tie Guan Yin 1 | Bacillus thuringiensis | 100.0 | No colonies | |

| Staphylococcus warneri | 100.0 | |||

| Bacillus safensis | 100.0 | |||

| Staphylococcus capitis | 99.6 | |||

| Lysinibacillus sphaericus | 99.3 | |||

| Tie Guan Yin 2 | Paenibacillus polymyxa | 100.0 | No colonies | |

| Heyndrickxia coagulans | 99.5 | |||

| Bacillus pumilus | 99.3 | |||

| Lysinibacillus sphaericus | 99.7 | |||

| Bacillus subtilis | 100.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uhlig, E.; Megaelectra, A.; Molin, G.; Håkansson, Å. Viable and Heat-Resistant Microbiota with Probiotic Potential in Fermented and Non-Fermented Tea Leaves and Brews. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13050964

Uhlig E, Megaelectra A, Molin G, Håkansson Å. Viable and Heat-Resistant Microbiota with Probiotic Potential in Fermented and Non-Fermented Tea Leaves and Brews. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(5):964. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13050964

Chicago/Turabian StyleUhlig, Elisabeth, Afina Megaelectra, Göran Molin, and Åsa Håkansson. 2025. "Viable and Heat-Resistant Microbiota with Probiotic Potential in Fermented and Non-Fermented Tea Leaves and Brews" Microorganisms 13, no. 5: 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13050964

APA StyleUhlig, E., Megaelectra, A., Molin, G., & Håkansson, Å. (2025). Viable and Heat-Resistant Microbiota with Probiotic Potential in Fermented and Non-Fermented Tea Leaves and Brews. Microorganisms, 13(5), 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13050964