Abstract

Stress granules (SG), dynamic cytoplasmic condensates formed via liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), serve as a critical hub for cellular stress adaptation and antiviral defense. By halting non-essential translation and sequestering viral RNA, SG restrict viral replication through multiple mechanisms, including PKR-eIF2α signaling, recruitment of antiviral proteins, and spatial isolation of viral components. However, viruses have evolved sophisticated strategies to subvert SG-mediated defenses, including proteolytic cleavage of SG nucleators, sequestration of core proteins into viral replication complexes, and modulation of stress-responsive pathways. This review highlights the dual roles of SG as both antiviral sentinels and targets of viral manipulation, emphasizing their interplay with innate immunity, autophagy, and apoptosis. Furthermore, viruses exploit SG heterogeneity and crosstalk with RNA granules like processing bodies (P-bodies, PB) to evade host defenses, while viral inclusion bodies (IBs) recruit SG components to create proviral microenvironments. Future research directions include elucidating spatiotemporal SG dynamics in vivo, dissecting compositional heterogeneity, and leveraging advanced technologies to unravel context-specific host-pathogen conflicts. This review about viruses and SG formation helps better understand the virus-host interaction and game process to develop new drug targets. Understanding these mechanisms not only advances virology but also informs innovative strategies to address immune escape mechanisms in viral infections.

1. Introduction

Stress granules (SG) are dynamic, membraneless organelles formed in eukaryotic cells in response to various external stresses, such as viral infection, oxidative stress, or heat shock [1]. They function by halting non-essential protein translation and aggregating untranslated mRNA, translation initiation factors, and RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) in the cytoplasm [2]. The formation of SG relies on liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), with core regulatory factors including Ras-GTPase-activating protein-binding proteins (G3BP1/2) and T-cell intracellular antigen-1 (TIA1) [3,4]. As a critical component of the host innate immune response, SG exert potent antiviral functions by inhibiting viral protein synthesis, sequestering viral RNA, recruiting antiviral proteins (e.g., PKR, RIG-I), and disrupting viral replication cycles [5,6]. However, viruses have evolved diverse strategies to counteract SG formation, enabling them to evade host defenses and facilitate their own replication. Multiple studies on virus-SG interactions have unveiled complex molecular mechanisms, ranging from direct targeting of SG core proteins to modulation of host translation pathways. This review systematically summarizes the molecular mechanisms underlying SG formation, the diverse strategies employed by viruses to manipulate SG, and the implications for viral pathogenesis. Furthermore, we discuss future research directions in this frontier field.

2. Stress Granules: Fundamental Concepts

SG are dynamic condensates composed of translationally stalled mRNA, RBPs, and translation initiation factors, functioning in mRNA triage, translational control, and cellular stress adaptation [7]. SG assembly occurs through a dynamic multistage process driven by phase separation of scaffold proteins and multivalent RNA interactions. The process initiates with global translational suppression under stress conditions, leading to cytoplasmic accumulation of untranslated mRNPs [7]. G3BP1 oligomerizes via its NTF2L domain and binds RNA through RGG/RRM motifs, thereby driving phase separation of mRNA-RBPs complexes to form SG nucleation cores [3,8]. This phase separation capacity underlies the dynamic SG remodeling observed during viral infections, reflecting an evolutionary battleground between host defense and viral countermeasures [9]. By regulating mRNA metabolism, translational reprogramming, and stress signaling, SG formation constitutes a critical adaptive mechanism for cellular survival under viral challenge and diverse stressors.

2.1. Structure and Composition of SG

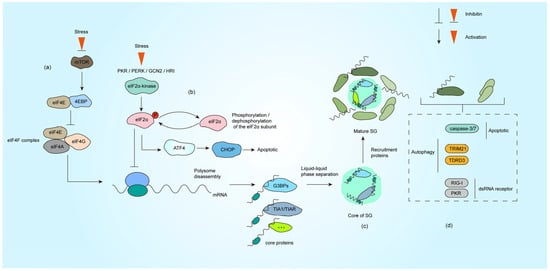

SG assemble dynamically through multivalent interactions and phase separation of core components. Proteomic analyses have identified over 300 SG-associated proteins, yet genetic studies by Yang et al. revealed G3BP1/2 as the most essential homologous proteins for SG nucleation [3,10,11]. G3BP1 employs its RNA recognition motif (RRM) and glycine-rich RGG domain to bind RNA, forming polymerization networks that recruit other SG components (e.g., TIA-1, eIF3) and drive LLPS [3,12,13]. The activity of G3BP1 is tightly regulated by post-translational modifications: acetylation (K376) weakens RNA binding to promote SG disassembly [14], while phosphorylation (Ser149) modulates assembly dynamics [15]. Moreover, TRIM21-mediated K63-linked ubiquitination of G3BP1 facilitates SG clearance via autophagy receptors SQSTM1/CALCOCO2, maintaining protein homeostasis (Figure 1d) [16].

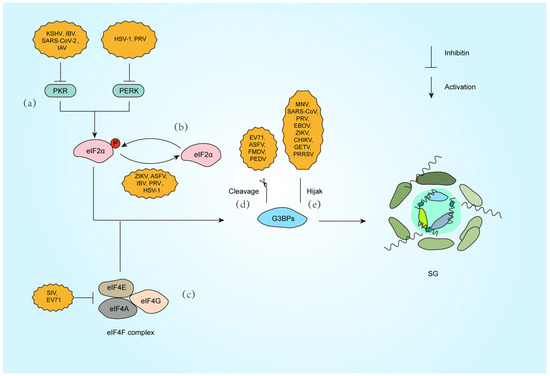

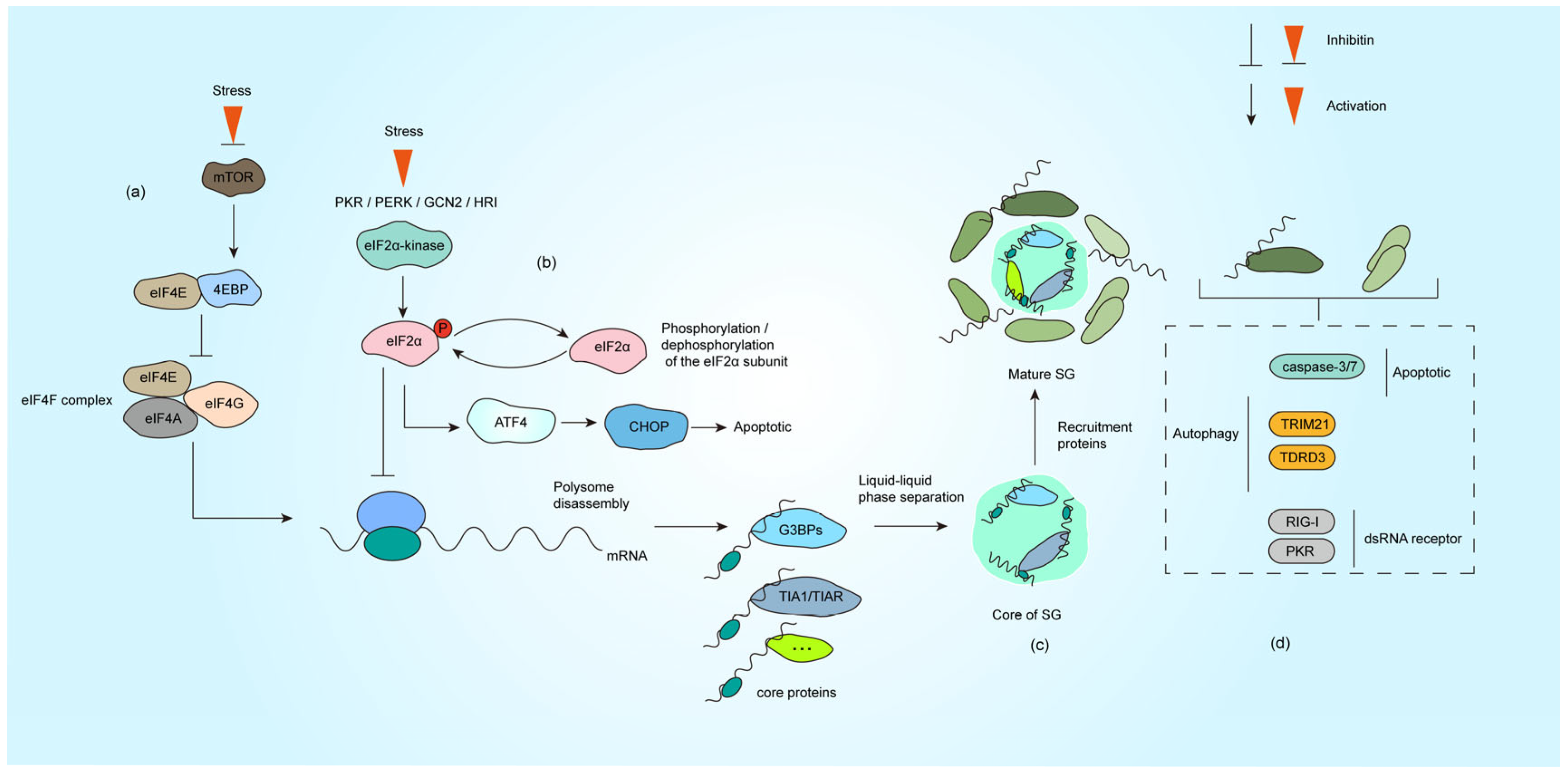

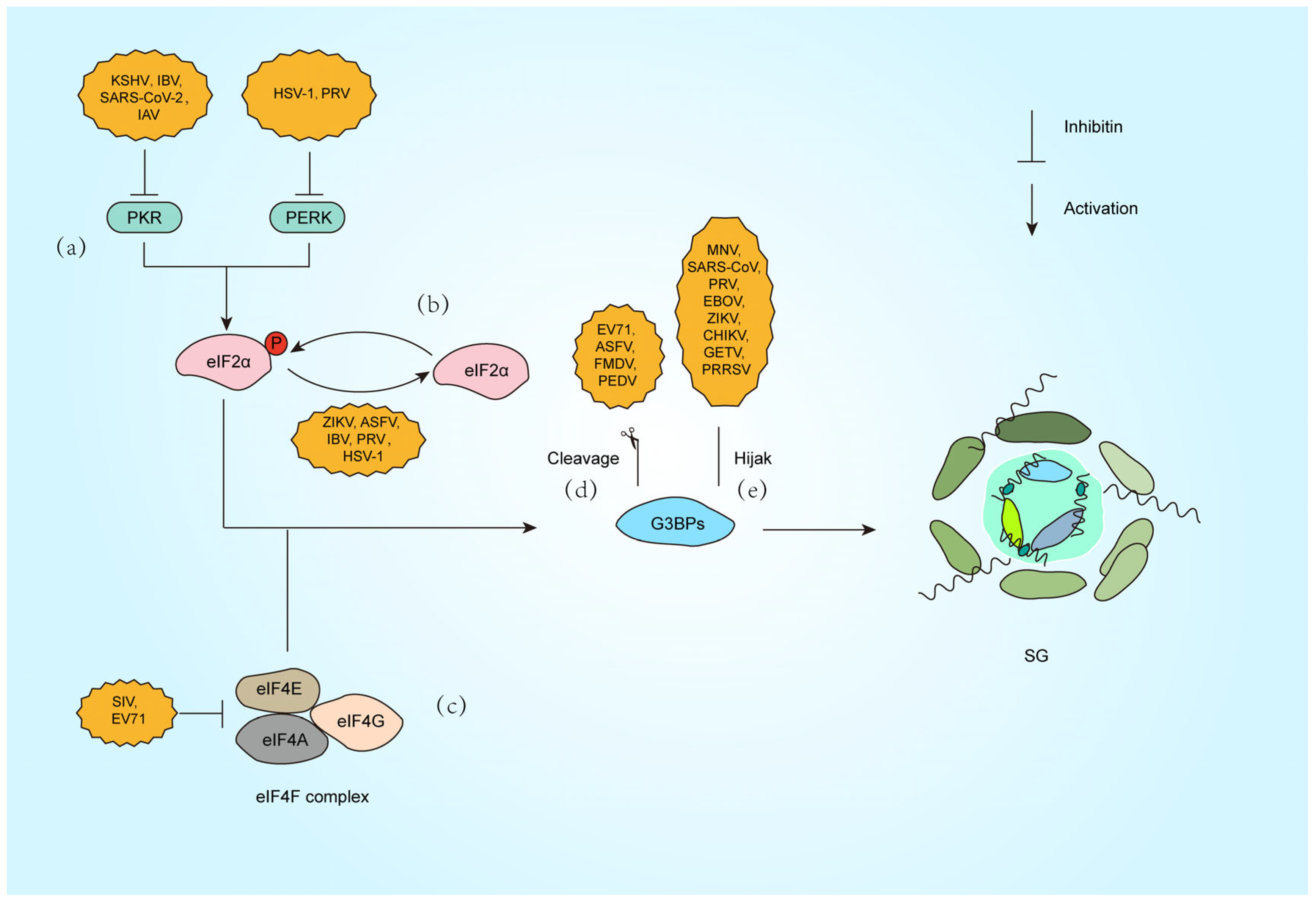

Figure 1.

Formation process of SG under stress. (a) The impaired formation of the eIF4F complex under stress conditions leads to inhibition of translation initiation. (b) The activation of PKR, PERK, HRI and GCN2 under stress causes eIF2α phosphorylation, translation initiation is halted subsequent to the incorporation of phosphorylated eIF2α into the initiation complex. (c) SG nucleating proteins (such as G3BP1, TIA1, etc.) bind to untranslated mRNPs. These proteins nucleate the core of SG through LLPS, which subsequently recruit additional functional proteins (primarily RNA-binding proteins) to form mature SG. (d) Representative proteins involved in autophagy, apoptosis, and dsRNA sensing that are recruited to SG, with comprehensive descriptions provided in Section 3.1, Section 3.2, Section 3.3 and Section 3.4.

Other core proteins contribute synergistically: TIA-1/TIAR proteins utilize low-complexity domains (LCDs) to induce phase separation, with tandem RNA-binding motifs enhancing nucleation efficiency [4,17]. eIF3, a translation initiation complex subunit, marks stalled ribosomes and integrates 48S preinitiation complexes (PICs) into SG networks [12,18]. Intriguingly, UBAP2L acts as an upstream nucleator, forming G3BP1-independent SG substructures and modulating heterogeneity through competitive interactions [19]. The functional interplay and post-translational regulation of these components collectively determine SG assembly kinetics, stability, and antiviral efficacy.

SG also incorporates auxiliary elements that fine-tune their dynamics: (i) Non-coding RNA: AU-rich elements in the 3′ UTRs of mRNAs and lncRNA are selectively sequestered for storage or translational suppression, while viral RNA may hijack SG functions [20,21]. (ii) Regulatory enzymes: Kinases (PKR, PERK) phosphorylate eIF2α to stall translation and promote SG assembly, counterbalanced by phosphatases PP1/PP2A that dissolve SG [7,22]. As a deacetylase, histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) regulates SG formation by interacting with G3BP1 and regulates post-translational modification of viral proteins [23,24]. Ubiquitin protease TRIM25 enhances antiviral responses by targeting viral RNA [25]. In addition to this, IRE1α acts as an ER stress sensor and co-condenses with SG via phase separation to amplify unfolded protein responses [26]. (iii) Metabolic modulators: NAD+-dependent sirtuins (e.g., SIRT1) regulate SG dynamics by deacetylating RBPs like TIA-1. Low NAD+ levels impair deacetylation, causing aberrant SG stabilization, while NAD+ repletion restores reversible disassembly [10]. This multilayered network ensures precise spatiotemporal control of SG formation, functional plasticity, and stress adaptation.

2.2. Mechanisms of SG Formation

Translational suppression is a prerequisite for SG assembly. Under stress conditions, cells activate the integrated stress response (ISR) to globally inhibit translation while selectively synthesizing critical proteins such as heat shock chaperones [27]. This strategy not only conserves cellular resources but also prevents the translation of potentially harmful mRNA (e.g., viral RNA or cancer-associated transcripts) [28]. The accumulation of untranslated mRNPs recruits SG core proteins like G3BP1, which drive phase separation to initiate SG assembly.

In eukaryotes, translational control primarily targets the cap-dependent initiation complex [7]. Stress-induced translation inhibition occurs via two distinct pathways: eIF2α-dependent or eIF2α-independent mechanisms [29]. The canonical translation process begins with eIF4E binding to the 5′ 7-methylguanosine mRNA cap, a step regulated by 4EBP. Under stress, dephosphorylated 4EBP competitively blocks eIF4E recruitment into the EIF4F complex, whereas phosphorylated 4EBP releases eIF4E to resume translation [30] (Figure 1a). Concurrently, phosphorylation of the eIF2α subunit disrupts the eIF2-GTP-Met-tRNAMet ternary complex, impairing 43S preinitiation complex assembly. Four eIF2α kinases (PKR, PERK, HRI, and GCN2) are activated by distinct stressors: PKR senses viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) [5], PERK responds to ER stress [31], HRI detects oxidative stress/heme deprivation [32], and GCN2 monitors nutrient deprivation [33] (Figure 1b). Viral infections often activate PKR directly via genomic RNA or indirectly through stress cascades involving other kinases.

mRNA plays a central role in SG dynamics. Polyadenylated mRNA and RNA-binding proteins form the structural backbone of SG [34]. Notably, nuclear export of newly synthesized cytoplasmic mRNA is critical for SG formation. Inhibition of mRNA transcription, splicing, or export reduces canonical SG assembly independently of eIF2α phosphorylation [35]. Additionally, viral RNA activates the pattern recognition receptor PKR, triggering eIF2α phosphorylation and SG induction, highlighting a key viral-host battleground [36,37].

SG assembly is currently viewed as a two-phase process: Nucleation and Maturation. During early stress (e.g., within 15 min of arsenite exposure), G3BP1 binds poly(A)-tailed mRNA, translation initiation factors (e.g., PABP1, eIF4G), and forms primary condensates. These structures exhibit irregular morphologies under microscopy, indicative of nascent organizational complexity.

Under the action of LLPS, SG further recruits a variety of proteins and develops into structures with functional partitions [18,38]. Studies reveal a dense core region (enriched with G3BP1-Caprin1-USP10 complexes) and a dynamic periphery (containing ATPases like DDX6), supporting a phase separation-mediated compartmentalization model [39,40]. This spatial organization allows SG to dynamically adapt to cellular conditions while maintaining functional specificity (Figure 1c).

4. Stress Granule Crosstalk with Other Granules in Viral Infection

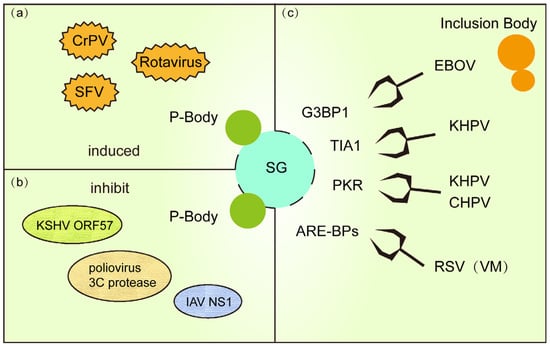

RNA granules are dynamic cytoplasmic structures formed through phase separation of RNA molecules and proteins, widely present in eukaryotes, including SG and P-bodies. These granules regulate post-transcriptional gene expression (e.g., mRNA translation, storage, transport, and degradation), participating in cellular metabolism, stress responses, and developmental processes [90]. During viral infection, SG and PB form a cooperative antiviral defense: SG suppress viral replication by sequestering viral RNA and translation factors, while PB degrade viral Mrna [91,92]. Both structures dynamically assemble via phase separation and complementarily regulate RNA metabolism [93]. However, viruses have evolved dual strategies to dismantle this network. Viral IBs, such as the N/P protein condensates of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and Ebola virus, not only serve as replication factories but also inhibit SG assembly and reprogram host RNA metabolism by sequestering key SG proteins (e.g., TIA-1, G3BP1) or signaling molecules [94]. As dynamic membraneless structures, the compositional interplay among SG, P-bodies, and IBs reflects a broader battleground between host defense mechanisms and viral invasion.

4.1. PB and SG: Cooperative Antiviral Defense

SG and PB, two key cytoplasmic RNA condensates, exhibit both functional synergy and shared targeting by viral proteins during infection. SG enriched in RNA-binding proteins like G3BP1 and TIA-1 contrast with PB, which house RNA decay machinery (e.g., XRN1, CCR4-NOT complex) and GW182-family proteins. Despite partial spatial and compositional overlap, their roles are complementary: SG respond acutely to translational arrest and rapidly disassemble upon stress relief, whereas PB exhibit lower dynamics and mediate terminal mRNA metabolism [95,96]. This divergence underscores their distinct yet coordinated antiviral functions.

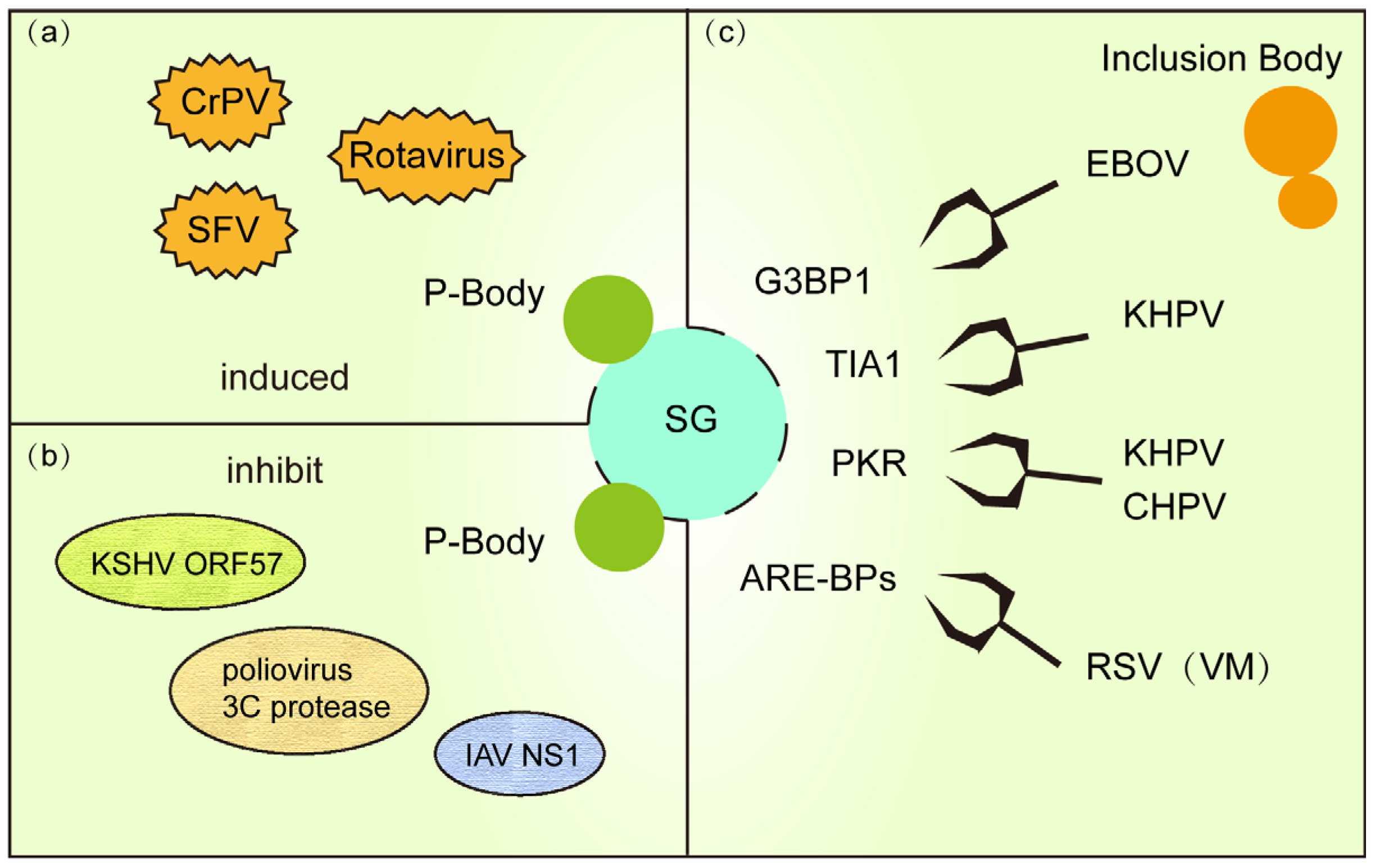

Viral infections often trigger cooperative SG-PB defense networks (Figure 3a). For example, early rotavirus infection induces SG (marked by G3BP1) and PB (marked by DCP1a) assembly to suppress viral protein synthesis by isolating viral RNA or restricting their translation [97]. Similarly, in Cricket paralysis virus (CrPV)-infected Drosophila cells, SG block viral translation initiation while PB degrade viral RNA, synergistically curbing infection [98]. During SFV infection, eIF2α phosphorylation-driven SG formation collaborates with PB-mediated viral RNA decay to restrict replication [99]. These observations highlight a “dual-barrier” system where SG and PB deploy distinct mechanisms to impede viral propagation.

Figure 3.

(a) PB and SG are co-formed in response to viral replication during viral infection. (b) Some viral proteins use a strategy of killing two birds with one stone to inhibit PB and SG formation. (c) IB (or VM) formed during viral infection hinders SG formation by stealing and sequestering important proteins for SG formation.

To evade host defenses, diverse viruses have evolved strategies to concurrently disrupt both SG and P-bodies (Figure 3b). For instance, KSHV encodes the RNA-binding protein ORF57, which directly interacts with PB core components GW182 and Ago2 to inhibit PB scaffolding while blocking PKR signaling required for SG assembly, thereby enhancing viral RNA translation [93]. Similarly, poliovirus 3C protease degrades PB-associated proteins DCP1a and Pan3 to cripple mRNA decay pathways, while simultaneously cleaving SG nucleator G3BP1 to dismantle both condensates [100]. Influenza virus NS1 protein further exemplifies this dual targeting by binding RAP55 to dysregulate SG-PB crosstalk, suppressing antiviral RNA storage and degradation [101]. These examples underscore the centrality of SG-PB interplay in host defense and reveal a viral “two birds with one stone” tactic to hijack RNA regulatory networks.

4.2. Viral Disruption of SG Formation via Inclusion Body Hijacking

Viral inclusion bodies (IBs) are dynamic, membraneless structures formed during infection, comprising viral proteins, host factors, and viral genomic RNA/DNA. These condensates serve as central hubs for viral replication and transcription. For example, RSV IBs assemble via LLPS driven by nucleoprotein (N) and phosphoprotein (P), which form multivalent interaction networks to recruit viral polymerases and host cofactors, optimizing viral RNA synthesis [102]. Similarly, human metapneumovirus (HMPV) IBs organize viral RNA synthesis machinery through cytoskeleton-mediated aggregation [103]. Beyond replication, IBs act as molecular traps by sequestering antiviral host proteins (e.g., SG components), creating a proviral microenvironment [94].

Viruses exploit IBs to actively suppress SG assembly (Figure 3c). In RSV infection, IBs sequester critical signaling proteins like phosphorylated p38 kinase and O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT), inhibiting MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MK2) activity and blocking SG nucleation. RSV infection establishes specialized viral factories (VMs) that reprogram host SG and P-bodies by selectively recruiting their components, such as AU-rich element-binding proteins (ARE-BPs), into these replication hubs. This molecular sieving not only neutralizes SG antiviral functions but also repurposes host RNA metabolism factors to enhance viral genome replication [97,104]. Ebola virus (EBOV) IBs co-opt SG markers (e.g., TIA-1, G3BP1) into “atypical SG-like granules” that lack translation arrest functionality, ensuring uninterrupted viral protein synthesis [82]. Concurrently, human parainfluenza virus 3 (HPIV3) further illustrates this strategy: its N-P protein complex shields viral RNA from sensors, preventing PKR-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation and SG formation. HPIV3 exploits nucleoprotein (N)-phosphoprotein (P) interactions to assemble IBs that suppress SG formation [105]. These IBs shield nascent viral RNA from SG-mediated antiviral surveillance, effectively subverting host defense mechanisms through spatial compartmentalization of viral replication.

Recent studies reveal that Chandipura virus (CHPV) IBs recruit host PKR and TIA-1 via phase separation to form proviral condensates. Depleting TIA-1 or PKR severely impairs viral transcription, demonstrating their unexpected proviral roles within IBs [106]. Collectively, these findings position viral IBs not merely as replication factories but as molecular pliers that reshape host SG dynamics to favor viral persistence.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The dynamic battle between SG and viruses highlights a key evolutionary conflict in host-pathogen interactions. SG act as vital antiviral hubs, halting non-essential protein production, trapping viral RNA, and boosting immune signals like the PKR-eIF2α and RIG-I/MAVS pathways. However, viruses have evolved clever tactics to dismantle SG. These include cutting apart core SG proteins like G3BP1 (using enzymes such as EV71 3Cpro and FMDV Lpro), hijacking SG components into their own replication factories (as seen with SARS-CoV-2 N protein and PRV IE180), or diverting them into viral inclusion bodies (e.g., in RSV and Ebola virus infections). Viruses also manipulate stress pathways like autophagy and apoptosis to disrupt SG. This constant tug-of-war shows how viruses exploit the very adaptability of SG to evade immune defenses and thrive.

Moving forward, critical research goals are to visualize how SG behave in real-time within living organisms during infection using advanced tools like live-cell imaging and spatial transcriptomics. We also need to understand how differences in SG composition affect their ability to fight viruses and define the roles played by less-studied SG parts and their chemical modifications (like phosphorylation or ubiquitination) in these battles. Unraveling these details is crucial not only for fundamental virus research but also for developing new treatments. These could aim to strengthen SG defenses or block the viruses’ strategies for disabling them, carefully balancing powerful antiviral effects with potential harm to the host cell.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, R.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.L.; supervision, X.L.; project administration, R.Z. and X.L.; funding acquisition, X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD1800300), Jiangsu Innovative and Entrepreneurial Talent Team Project (JSSCTD202224), the 111 Project D18007, the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD), and Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX23_3601).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PRV | Pseudorabies virus |

| SG | Stress granules |

| PB | Processing bodies |

| IB | Inclusion bodies |

| G3BP1/2 | Ras-GTPase-activating protein-binding proteins |

| TIA1 | T-cell intracellular antigen-1 |

| RBPs | RNA-binding proteins |

| LCDs | Low-complexity domains |

| PICs | Preinitiation complexes |

| ISR | Integrated stress response |

| dsRNA | double-stranded RNA |

| PABP1 | poly(A)-binding protein |

| HSV | herpes simplex virus |

| KSHV | Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus |

| IAV | Influenza A virus |

| PRRSV | Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus |

| RLR | RIG-I-like receptor |

| NDV | Newcastle disease virus |

| HDAC6 | Histone deacetylase 6 |

| HTLV-1 | Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 |

| MAVS | Mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein |

| WNV | West Nile virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| EV71 | Enterovirus 71 |

| FMDV | Foot-and-mouth disease virus |

| ASFV | African swine fever virus |

| PEDV | Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus |

| MNV | Murine norovirus |

| CJHIKV | Chikungunya virus |

| GETV | Getah virus |

| RSV | Respiratory syncytial virus |

References

- Hofmann, S.; Kedersha, N.; Anderson, P.; Ivanov, P. Molecular mechanisms of stress granule assembly and disassembly. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Cell Res. 2021, 1868, 118876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedersha, N.; Stoecklin, G.; Ayodele, M.; Yacono, P.; Lykke-Andersen, J.; Fritzler, M.J.; Scheuner, D.; Kaufman, R.J.; Golan, D.E.; Anderson, P. Stress granules and processing bodies are dynamically linked sites of mRNP remodeling. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 169, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Mathieu, C.; Kolaitis, R.M.; Zhang, P.; Messing, J.; Yurtsever, U.; Yang, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Pan, Q.; et al. G3BP1 Is a Tunable Switch that Triggers Phase Separation to Assemble Stress Granules. Cell 2020, 181, 325–345.e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayman, J.B.; Karl, K.A.; Kandel, E.R. TIA-1 Self-Multimerization, Phase Separation, and Recruitment into Stress Granules Are Dynamically Regulated by Zn(2). Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Chai, Y.; Weng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Ge, X.; Guo, X.; Han, J.; et al. Viral evasion of PKR restriction by reprogramming cellular stress granules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2201169119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumiya, T.; Shiba, Y.; Ding, J.; Kawaguchi, S.; Seya, K.; Imaizumi, T. The double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR negatively regulates the protein expression of IFN-β induced by RIG-I signaling. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e22780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownsword, M.J.; Locker, N. A little less aggregation a little more replication: Viral manipulation of stress granules. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2023, 14, e1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Huang, R.; Mei, Y.; Lu, S.; Gong, J.; Wang, L.; Ding, L.; Wu, H.; Pan, D.; Liu, W. Application of stress granule core element G3BP1 in various diseases: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guille´n-Boixet, J.; Kopach, A.; Holehouse, A.S.; Wittmann, S.; Jahnel, M.; Schlüßler, R.; Kim, K.; Trussina, I.; Wang, J.; Mateju, D.; et al. RNA-Induced Conformational Switching and Clustering of G3BP Drive Stress Granule Assembly by Condensation. Cell 2020, 181, 346–361.e317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Wheeler, J.R.; Walters, R.W.; Agrawal, A.; Barsic, A.; Parker, R. ATPase-Modulated Stress Granules Contain a Diverse Proteome and Substructure. Cell 2016, 164, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markmiller, S.; Soltanieh, S.; Server, K.L.; Mak, R.; Jin, W.; Fang, M.Y.; Luo, E.C.; Krach, F.; Yang, D.; Sen, A.; et al. Context-Dependent and Disease-Specific Diversity in Protein Interactions within Stress Granules. Cell 2018, 172, 590–604.e513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xian, W.; Li, Z.; Lu, Q.; Chen, X.; Ge, J.; Tang, Z.; Liu, B.; Chen, Z.; Gao, X.; et al. Shigella induces stress granule formation by ADP-riboxanation of the eIF3 complex. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, S.; Gladfelter, A.; Mittag, T. Considerations and Challenges in Studying Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation and Biomolecular Condensates. Cell 2019, 176, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gal, J.; Chen, J.; Na, D.Y.; Tichacek, L.; Barnett, K.R.; Zhu, H. The Acetylation of Lysine-376 of G3BP1 Regulates RNA Binding and Stress Granule Dynamics. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2019, 39, e00052-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panas, M.D.; Kedersha, N.; Schulte, T.; Branca, R.M.; Ivanov, P.; Anderson, P. Phosphorylation of G3BP1-S149 does not influence stress granule assembly. J. Cell Biol. 2019, 218, 2425–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, Z.; Kang, Y.; Yi, Q.; Wang, T.; Bai, Y.; Liu, Y. Stress granule homeostasis is modulated by TRIM21-mediated ubiquitination of G3BP1 and autophagy-dependent elimination of stress granules. Autophagy 2023, 19, 1934–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughlin, F.E.; West, D.L.; Gunzburg, M.J.; Waris, S.; Crawford, S.A.; Wilce, M.C.J.; Wilce, J.A. Tandem RNA binding sites induce self-association of the stress granule marker protein TIA-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 2403–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, D.W.; Kedersha, N.; Lee, D.S.W.; Strom, A.R.; Drake, V.; Riback, J.A.; Bracha, D.; Eeftens, J.M.; Iwanicki, A.; Wang, A.; et al. Competing Protein-RNA Interaction Networks Control Multiphase Intracellular Organization. Cell 2020, 181, 306–324.e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirillo, L.; Cieren, A.; Barbieri, S.; Khong, A.; Schwager, F.; Parker, R.; Gotta, M. UBAP2L Forms Distinct Cores that Act in Nucleating Stress Granules Upstream of G3BP1. Curr. Biol. CB 2020, 30, 698–707.e696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Duan, Y.; Duan, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Deng, X.; Qian, B.; Gu, J.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, S.; et al. Stress Induces Dynamic, Cytotoxicity-Antagonizing TDP-43 Nuclear Bodies via Paraspeckle LncRNA NEAT1-Mediated Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation. Mol. Cell 2020, 79, 443–458.e447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, S.; Kabuta, T.; Nagai, Y.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Akiyama, H.; Wada, K. TDP-43 associates with stalled ribosomes and contributes to cell survival during cellular stress. J. Neurochem. 2013, 126, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Jia, R.; Dai, Z.; Zhou, J.; Ruan, J.; Chng, W.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, X. Stress granules in cancer: Adaptive dynamics and therapeutic implications. iScience 2024, 27, 110359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.; Zhang, Y.; Matthias, P. The deacetylase HDAC6 is a novel critical component of stress granules involved in the stress response. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 3381–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, A.; Lo, M.; Chandra, P.; Datta Chaudhuri, R.; De, P.; Dutta, S.; Chawla-Sarkar, M. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein promotes self-deacetylation by inducing HDAC6 to facilitate viral replication. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, X.; Billadeau, D.D.; Yang, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, F.; Bai, P.; et al. TRIM25 predominately associates with anti-viral stress granules. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Yao, X.; Wang, G.; Huang, S.; Chen, P.; Tang, M.; Cai, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Mammalian IRE1α dynamically and functionally coalesces with stress granules. Nat. Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 917–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poblete-Durán, N.; Prades-Pérez, Y.; Vera-Otarola, J.; Soto-Rifo, R.; Valiente-Echeverría, F. Who Regulates Whom? An Overview of RNA Granules and Viral Infections. Viruses 2016, 8, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, C.; Zhou, P. Role(s) of G3BPs in Human Pathogenesis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2023, 387, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, D.; Mathews, M.B.; Mohr, I. Tinkering with translation: Protein synthesis in virus-infected cells. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a012351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mars, J.-C.; Culjkovic-Kraljacic, B.; Borden, K.L.B. eIF4E orchestrates mRNA processing, RNA export and translation to modify specific protein production. Nucleus 2024, 15, 2360196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, H.P.; Zhang, Y.; Ron, D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature 1999, 397, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, E.; Kedersha, N.; Song, B.; Scheuner, D.; Gilks, N.; Han, A.; Chen, J.J.; Anderson, P.; Kaufman, R.J. Heme-regulated inhibitor kinase-mediated phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 inhibits translation, induces stress granule formation, and mediates survival upon arsenite exposure. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 16925–16933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dever, T.E.; Feng, L.; Wek, R.C.; Cigan, A.M.; Donahue, T.F.; Hinnebusch, A.G. Phosphorylation of initiation factor 2 alpha by protein kinase GCN2 mediates gene-specific translational control of GCN4 in yeast. Cell 1992, 68, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khong, A.; Matheny, T.; Jain, S.; Mitchell, S.F.; Wheeler, J.R.; Parker, R. The Stress Granule Transcriptome Reveals Principles of mRNA Accumulation in Stress Granules. Mol. Cell 2017, 68, 808–820.e805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, M.; Fleshler, E.; Atrash, M.K.; Kinor, N.; Benichou, J.I.C.; Shav-Tal, Y. Nuclear RNA-related processes modulate the assembly of cytoplasmic RNA granules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 5356–5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.C.; Lloyd, R.E. Cytoplasmic RNA Granules and Viral Infection. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2014, 1, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbet, G.A.; Burke, J.M.; Bublitz, G.R.; Tay, J.W.; Parker, R. dsRNA-induced condensation of antiviral proteins modulates PKR activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2204235119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protter, D.S.W.; Parker, R. Principles and Properties of Stress Granules. Trends Cell Biol. 2016, 26, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedersha, N.; Panas, M.D.; Achorn, C.A.; Lyons, S.; Tisdale, S.; Hickman, T.; Thomas, M.; Lieberman, J.; McInerney, G.M.; Ivanov, P.; et al. G3BP-Caprin1-USP10 complexes mediate stress granule condensation and associate with 40S subunits. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 212, 845–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripin, N.; Macedo de Vasconcelos, L.; Ugay, D.A.; Parker, R. DDX6 modulates P-body and stress granule assembly, composition, and docking. J. Cell Biol. 2024, 223, e202306022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paget, M.; Cadena, C.; Ahmad, S.; Wang, H.T.; Jordan, T.X.; Kim, E.; Koo, B.; Lyons, S.M.; Ivanov, P.; tenOever, B.; et al. Stress granules are shock absorbers that prevent excessive innate immune responses to dsRNA. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 1180–1196.e1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Gao, S.; Zhu, C.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Kang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T. Typical Stress Granule Proteins Interact with the 3′ Untranslated Region of Enterovirus D68 To Inhibit Viral Replication. J. Virol. 2020, 94, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, K.N.; Chong, C.L.; Chou, Y.C.; Huang, C.C.; Wang, Y.L.; Wang, S.W.; Chen, M.L.; Chen, C.H.; Chang, C. Doubly Spliced RNA of Hepatitis B Virus Suppresses Viral Transcription via TATA-Binding Protein and Induces Stress Granule Assembly. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 11406–11419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fros, J.J.; Pijlman, G.P. Alphavirus Infection: Host Cell Shut-Off and Inhibition of Antiviral Responses. Viruses 2016, 8, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.M.; Ratnayake, O.C.; Watkins, J.M.; Perera, R.; Parker, R. G3BP1-dependent condensation of translationally inactive viral RNAs antagonizes infection. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk8152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunath, L.; Oh, S.; Ortega, P.; Bouin, A.; Bournique, E.; Sanchez, A.; Martensen, P.M.; Auerbach, A.A.; Becker, J.T.; Seldin, M.; et al. APOBEC3B drives PKR-mediated translation shutdown and protects stress granules in response to viral infection. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, K.M.; Schrimpf, J.E.; Morrison, L.A. Increased eIF2alpha phosphorylation attenuates replication of herpes simplex virus 2 vhs mutants in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and correlates with reduced accumulation of the PKR antagonist ICP34.5. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 9151–9162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Lee, R.; Feng, Q.; Langereis, M.A.; Ter Horst, R.; Szklarczyk, R.; Netea, M.G.; Andeweg, A.C.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.; Huynen, M.A. Integrative Genomics-Based Discovery of Novel Regulators of the Innate Antiviral Response. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, e1004553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.W.; Onomoto, K.; Wakimoto, M.; Onoguchi, K.; Ishidate, F.; Fujiwara, T.; Yoneyama, M.; Kato, H.; Fujita, T. Leader-Containing Uncapped Viral Transcript Activates RIG-I in Antiviral Stress Granules. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Dong, L.; Yu, S.; Wang, X.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, P.; Meng, C.; Zhan, Y.; Tan, L.; Song, C.; et al. Newcastle disease virus induces stable formation of bona fide stress granules to facilitate viral replication through manipulating host protein translation. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 1337–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N.; Komatsu, M. Autophagy: Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 2011, 147, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deater, M.; Lloyd, R.E. TDRD3 functions as a selective autophagy receptor with dual roles in autophagy and modulation of stress granule stability. bioRxiv Prepr. Serv. Biol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, L.; Wang, J.; Su, D.; Li, D.; Du, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhang, G.; Chu, B. African Swine Fever Virus K205R Induces ER Stress and Consequently Activates Autophagy and the NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Viruses 2022, 14, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monahan, Z.; Shewmaker, F.; Pandey, U.B. Stress granules at the intersection of autophagy and ALS. Brain Res. 2016, 1649, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, L.; Rubinsztein, D.C. The autophagy of stress granules. FEBS Lett. 2024, 598, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhu, G.; Tang, Y.; Yan, J.; Han, S.; Yin, J.; Peng, B.; He, X.; Liu, W. HDAC6, A Novel Cargo for Autophagic Clearance of Stress Granules, Mediates the Repression of the Type I Interferon Response During Coxsackievirus A16 Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujikawa, D.; Nakamura, T.; Yoshioka, D.; Li, Z.; Moriizumi, H.; Taguchi, M.; Tokai-Nishizumi, N.; Kozuka-Hata, H.; Oyama, M.; Takekawa, M. Stress granule formation inhibits stress-induced apoptosis by selectively sequestering executioner caspases. Curr. Biol. CB 2023, 33, 1967–1981.e1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Li, Z.; Xu, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Gao, R.; Lu, H.; Lan, Y.; Zhao, K.; He, H.; et al. The PERK/PKR-eIF2α Pathway Negatively Regulates Porcine Hemagglutinating Encephalomyelitis Virus Replication by Attenuating Global Protein Translation and Facilitating Stress Granule Formation. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0169521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Higuchi, M.; Makokha, G.N.; Matsuki, H.; Yoshita, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Fujii, M. HTLV-1 Tax oncoprotein stimulates ROS production and apoptosis in T cells by interacting with USP10. Blood 2013, 122, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Wang, H.X.; Mao, X.; Fang, H.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Meng, C.; Tan, L.; Song, C.; et al. RIP1 is a central signaling protein in regulation of TNF-α/TRAIL mediated apoptosis and necroptosis during Newcastle disease virus infection. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 43201–43217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, M.; Courtney, S.C.; Brinton, M.A. Arsenite-induced stress granule formation is inhibited by elevated levels of reduced glutathione in West Nile virus-infected cells. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Jin, J.; Li, J.; Ye, M.; Jin, X. The roles of G3BP1 in human diseases (review). Gene 2022, 821, 146294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.R.; Majerciak, V.; Kruhlak, M.J.; Zheng, Z.M. KSHV inhibits stress granule formation by viral ORF57 blocking PKR activation. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Fung, T.S.; Huang, M.; Fang, S.G.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, D.X. Upregulation of CHOP/GADD153 during coronavirus infectious bronchitis virus infection modulates apoptosis by restricting activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 8124–8134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, W.; Wen, W.; Zhang, Z.; Favoreel, H.W.; Li, X. Pseudorabies virus IE180 protein hijacks G3BPs into the nucleus to inhibit stress granule formation. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0208824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaperskyy, D.A.; Emara, M.M.; Johnston, B.P.; Anderson, P.; Hatchette, T.F.; McCormick, C. Influenza a virus host shutoff disables antiviral stress-induced translation arrest. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Su, C.; Jiang, Z.; Zheng, C. Herpes Simplex Virus 1 UL41 Protein Suppresses the IRE1/XBP1 Signal Pathway of the Unfolded Protein Response via Its RNase Activity. J. Virol. 2017, 91, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Ren, J.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, P.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Ge, X.; Guo, X.; Han, J.; et al. Pseudorabies virus inhibits the unfolded protein response for viral replication during the late stages of infection. Vet. Microbiol. 2025, 301, 110360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, R.; Temzi, A.; Griffin, B.D.; Mouland, A.J. Zika virus inhibits eIF2α-dependent stress granule assembly. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Moon, A.; Childs, K.; Goodbourn, S.; Dixon, L.K. The African swine fever virus DP71L protein recruits the protein phosphatase 1 catalytic subunit to dephosphorylate eIF2alpha and inhibits CHOP induction but is dispensable for these activities during virus infection. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 10681–10689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liao, Y.; Yap, P.L.; Png, K.J.; Tam, J.P.; Liu, D.X. Inhibition of protein kinase R activation and upregulation of GADD34 expression play a synergistic role in facilitating coronavirus replication by maintaining de novo protein synthesis in virus-infected cells. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 12462–12472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Chen, D.; Chen, D.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Ge, X.; Han, J.; Guo, X.; Yang, H. Pseudorabies virus infection inhibits stress granules formation via dephosphorylating eIF2alpha. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 247, 108786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Du, M.; Jin, H.; Ma, Y.; He, B.; et al. ICP34.5 protein of herpes simplex virus facilitates the initiation of protein translation by bridging eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) and protein phosphatase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 24785–24792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balvay, L.; Lopez Lastra, M.; Sargueil, B.; Darlix, J.L.; Ohlmann, T. Translational control of retroviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Hu, Z.; Fan, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Guo, D.; Qin, Y.; Chen, M. Picornavirus 2A protease regulates stress granule formation to facilitate viral translation. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, L.; Xu, X.; Han, H.; Li, P.; Zou, D.; Li, X.; Zheng, L.; Cheng, L.; Shen, Y.; et al. Enterovirus 71 inhibits cytoplasmic stress granule formation during the late stage of infection. Virus Res. 2018, 255, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhao, G.; Liu, C.; Bao, M.; Song, J.; Li, J.; Huang, L.; et al. African swine fever virus pS273R antagonizes stress granule formation by cleaving the nucleating protein G3BP1 to facilitate viral replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 104844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, L.J.; Medina, G.N.; Rabouw, H.H.; de Groot, R.J.; Langereis, M.A.; de Los Santos, T.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M. Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus Leader Protease Cleaves G3BP1 and G3BP2 and Inhibits Stress Granule Formation. J. Virol. 2019, 93, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Chen, H.; Ming, X.; Bo, Z.; Shin, H.J.; Jung, Y.S.; Qian, Y. Porcine Epidemic Diarrhea Virus Infection Induces Caspase-8-Mediated G3BP1 Cleavage and Subverts Stress Granules To Promote Viral Replication. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e02344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzlar, S.; Aktepe, T.E.; Chao, Y.W.; Kenney, N.D.; McAllaster, M.R.; Wilen, C.B.; White, P.A.; Mackenzie, J.M. Mouse Norovirus Infection Arrests Host Cell Translation Uncoupled from the Stress Granule-PKR-eIF2α Axis. mBio 2019, 10, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Johnson, B.A.; Meliopoulos, V.A.; Ju, X.; Zhang, P.; Hughes, M.P.; Wu, J.; Koreski, K.P.; Clary, J.E.; Chang, T.C.; et al. Interaction between host G3BP and viral nucleocapsid protein regulates SARS-CoV-2 replication and pathogenicity. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.V.; Schmidt, K.M.; Deflube, L.R.; Doganay, S.; Banadyga, L.; Olejnik, J.; Hume, A.J.; Ryabchikova, E.; Ebihara, H.; Kedersha, N.; et al. Ebola Virus Does Not Induce Stress Granule Formation during Infection and Sequesters Stress Granule Proteins within Viral Inclusions. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 7268–7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, S.; Kumar, A.; Xu, Z.; Airo, A.M.; Stryapunina, I.; Wong, C.P.; Branton, W.; Tchesnokov, E.; Götte, M.; Power, C.; et al. Zika Virus Hijacks Stress Granule Proteins and Modulates the Host Stress Response. J. Virol. 2017, 91, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fros, J.J.; Domeradzka, N.E.; Baggen, J.; Geertsema, C.; Flipse, J.; Vlak, J.M.; Pijlman, G.P. Chikungunya Virus nsP3 Blocks Stress Granule Assembly by Recruitment of G3BP into Cytoplasmic Foci. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 10873–10879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Zhao, R.; Yao, X.; Liu, Q.; Liu, P.; Zhu, Z.; Tu, C.; Gong, W.; Li, X. Getah virus Nsp3 binds G3BP to block formation of bona fide stress granules. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanzaro, N.; Meng, X.J. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV)-induced stress granules are associated with viral replication complexes and suppression of host translation. Virus Res. 2019, 265, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Sze, L.; Liu, C.; Lam, K.P. The stress granule protein G3BP1 binds viral dsRNA and RIG-I to enhance interferon-I response. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 6430–6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayabalan, A.K.; Adivarahan, S.; Koppula, A.; Abraham, R.; Batish, M.; Zenklusen, D.; Griffin, D.E.; Leung, A.K.L. Stress granule formation, disassembly, and composition are regulated by alphavirus ADP-ribosylhydrolase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2021719118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götte, B.; Panas, M.D.; Hellström, K.; Liu, L.; Samreen, B.; Larsson, O.; Ahola, T.; McInerney, G.M. Separate domains of G3BP promote efficient clustering of alphavirus replication complexes and recruitment of the translation initiation machinery. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckham, C.J.; Parker, R. P bodies, stress granules, and viral life cycles. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 3, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.E. Regulation of stress granules and P-bodies during RNA virus infection. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2013, 4, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, C.J.; Nelson, M.G.; Lui, J.; Bates, C.P.; Jennings, M.D.; Hubbard, S.J.; Ashe, M.P.; Grant, C.M. Integrated multi-omics reveals common properties underlying stress granule and P-body formation. RNA Biol. 2021, 18, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.R.; Zheng, Z.M. RNA Granules in Antiviral Innate Immunity: A Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Journey. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 794431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolnik, O.; Gerresheim, G.K.; Biedenkopf, N. New Perspectives on the Biogenesis of Viral Inclusion Bodies in Negative-Sense RNA Virus Infections. Cells 2021, 10, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berchtold, D.; Battich, N.; Pelkmans, L. A Systems-Level Study Reveals Regulators of Membrane-less Organelles in Human Cells. Mol. Cell 2018, 72, 1035–1049.e1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, J.-Y.; Dyakov, B.J.A.; Zhang, J.; Knight, J.D.R.; Vernon, R.M.; Forman-Kay, J.D.; Gingras, A.-C. Properties of Stress Granule and P-Body Proteomes. Mol. Cell 2019, 76, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, P.; Rao, C.D. Rotavirus Induces Formation of Remodeled Stress Granules and P Bodies and Their Sequestration in Viroplasms To Promote Progeny Virus Production. J. Virol. 2018, 92, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khong, A.; Jan, E. Modulation of stress granules and P bodies during dicistrovirus infection. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Weiss, E.; Panas, M.D.; Götte, B.; Sellberg, S.; Thaa, B.; McInerney, G.M. RNA processing bodies are disassembled during Old World alphavirus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 2019, 100, 1375–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, J.D.; White, J.P.; Lloyd, R.E. Poliovirus-mediated disruption of cytoplasmic processing bodies. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, B.W.; Song, W.; Wang, P.; Tai, H.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, M.; Wen, X.; Lau, S.Y.; Wu, W.L.; Matsumoto, K.; et al. The NS1 protein of influenza A virus interacts with cellular processing bodies and stress granules through RNA-associated protein 55 (RAP55) during virus infection. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 12695–12707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloux, M.; Risso-Ballester, J.; Richard, C.A.; Fix, J.; Rameix-Welti, M.A.; Eléouët, J.F. Minimal Elements Required for the Formation of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Cytoplasmic Inclusion Bodies In Vivo and In Vitro. mBio 2020, 11, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cifuentes-Muñoz, N.; Branttie, J.; Slaughter, K.B.; Dutch, R.E. Human Metapneumovirus Induces Formation of Inclusion Bodies for Efficient Genome Replication and Transcription. J. Virol. 2017, 91, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricke, J.; Koo, L.Y.; Brown, C.R.; Collins, P.L. p38 and OGT sequestration into viral inclusion bodies in cells infected with human respiratory syncytial virus suppresses MK2 activities and stress granule assembly. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 1333–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Q.; Yang, X.; Qin, Y.; Chen, M. Inclusion bodies of human parainfluenza virus type 3 inhibit antiviral stress granule formation by shielding viral RNAs. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Ganguly, S.; Ganguly, N.K.; Sarkar, D.P.; Sharma, N.R. Chandipura Virus Forms Cytoplasmic Inclusion Bodies through Phase Separation and Proviral Association of Cellular Protein Kinase R and Stress Granule Protein TIA-1. Viruses 2024, 16, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).